Hamer v. Musselwhite Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 5, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamer v. Musselwhite Brief for Appellants, 1966. d3b92b34-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2afefe77-6293-4e21-a453-ff94056cd23b/hamer-v-musselwhite-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

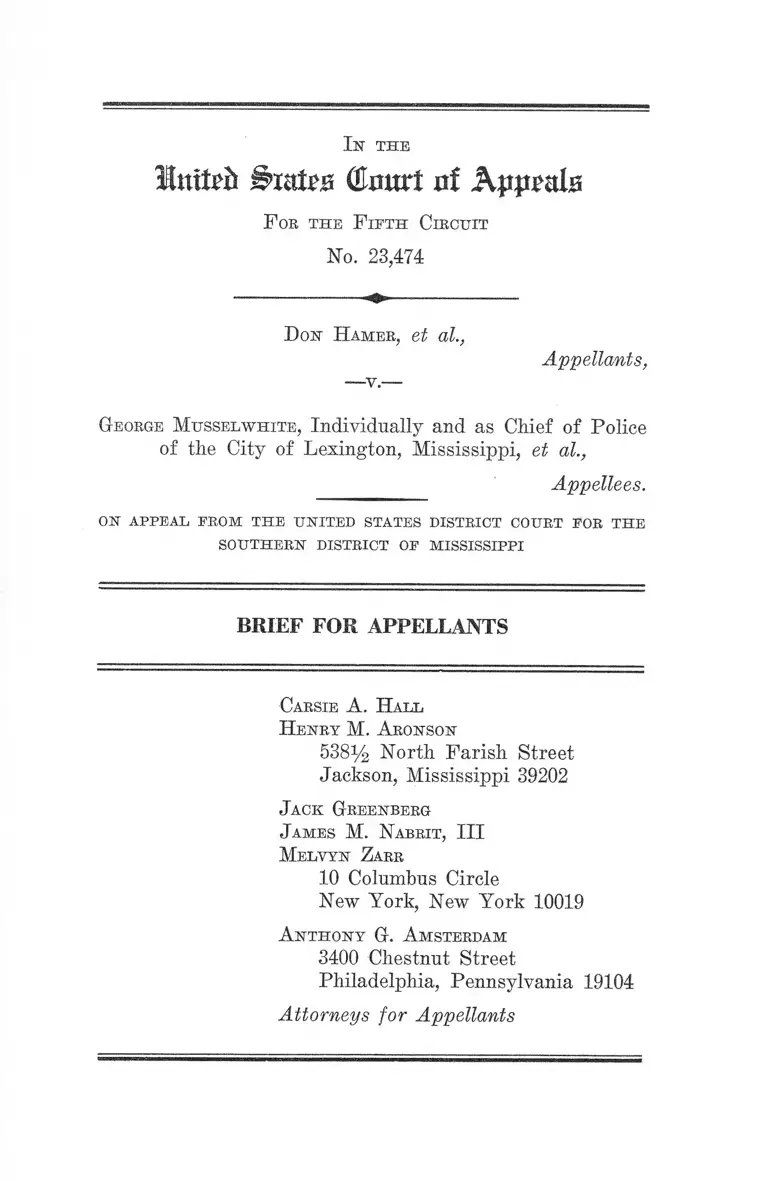

In the

Wnxtih Bmttz tour! nf Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 23,474

D on H amer, et al.,

Appellants,

George Mussel white, Individually and as Chief of Police

of the City of Lexington, Mississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Carsie A . H all

H enry M. A ronson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, ITT

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case...................................................... 1

Specifications of Error ...................................... ........... 12

A rgument

PAGE

The Present Lexington Ordinance Prohibiting All

Parades on Lexington’s Arterial Streets and Court

Square Is Offensive to the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States Because

A. The Ordinance Is Enforced in the Unfettered

Discretion of City Officials .......................... 13

B. The Ordinance Is a Vague and Overbroad

Regulation of Expression ............................ 19

C. The Ordinance Abridges Appellants’ Con

stitutional Guarantees of Free Speech, As

sembly and Petition ....................................... 21

Conclusion...................................................................... 31

Table oe Cases

Alabama ex rel. Gallion v. Rogers, 187 F. Supp. 848

(M. D. Ala. 1960), aff’d sub nom. Dinkens v. Attor

ney General, 285 F. 2d 430 (5th Cir. 1961) cert,

denied, Dinkens v. Rogers, 366 U. S. 913 (1961) .... 7

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F. 2d 649 (5th Cir.

1963) ............................................................................. 18

11

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 IT. S. 360 (1964) ..................... 18

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) .... 20

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624 (1943) 26

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 (1941) ................. 26

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 IT. S. 296 (1940) .......... 14,24

Carlson v. California, 310 IT. S. 106 (1940) ................. 24

Communications Ass’n v. Douds, 339 IT. S. 383 (1950) 24

Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492 (M. D. Ala.

1966) ........................................................................... 30

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 IT. S. 536 (1965) .....................16,28

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 IT. S. 559 (1965) ......................... 18

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 IT. S. 569 (1941) .............. 28

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353 (1937) ................. 24

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 IT. S. 479 (1965) .......... 18,20

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229 (1963) .... 26

Farmer v. Moses, 232 F. Supp. 154 (S. D. N. T. 1964) 29

Gluyot v. Pierce, 5th Cir., No. 22,990 ....................... 10,19

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 IT. S. 496 (1939) ..................... 21

Hurwitt v. City of Oakland, 247 F. Supp. 995 (N. D.

Calif. 1965) ................................................................ 28

Jones v. Opelika, 316 IT. S. 584 (1942), dissent adopted

on rehearing, per curiam, 319 U. S. 103 (1943) ...... 22

Katzenbach v. McClellan, 341 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1965) 7

Kelly y . Page, 335 F. 2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) .............. 27

Kennedy v. Owen, 321 F. 2d 116 (5th Cir. 1963) .......... 7

PAGE

Kovaes v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 (1949) ................. 22, 28, 29

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951) ........... 14,16, 22, 28

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366 U. S.

293 (1961) .................................................................... 30

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938) ....................... 14,24

Marsh v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 501 (1946) ........................ 25

Martin v. City of Strutbers, 319 U. S. 141 (1943) ...... 22

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943) ..... 22

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ...... 20, 26, 30

N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 357 F. 2d 831 (5th Cir.

1966) ..........................................................................19,26

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931) ..................... 24

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951) ................16, 28

Saia v. New York, 334 II. S. 558 (1948) .................21, 30

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1939) .... 14,21,26

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 (1960) .................... 30

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 (1958) .....................24, 25

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 II. S. 1 (1949) ........ ......... 24

Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 (1945) ................ ......... 26

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ...... 20, 22, 26, 30

Whitney v. California, 274 IT. S. 357 (1927) ..............26, 29

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M. D. Ala. 1965) 19

Ordinances

Lexington, Mississippi, Ordinance to Prohibit Parades

on Yazoo Street, Depot Street, Carrollton Street and

Court Square, June 1, 1965 .......... 2, 3, 8-15,18-23, 27, 31

IV

Lexington, Mississippi, Ordinance to Regulate Parades

on Yazoo Street, Depot Street, Carrollton Street and

Court Square, October 3, 1961..............2, 3, 8-10,13-15,18

Lexington, Mississippi, Ordinance to Prohibit Parades

on Yazoo Street, Depot Street, Carrollton Street and

Court Square, May 3, 1955 ......................................... 8, 9

Other A uthorities

V. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Voting in Missis

sippi (1965) ....-......................................................... 7

30 Federal Register No. 211 (1965) ..............................8 18

PAGE

I n the

ituiti'ii (£mtrt of Appeals

F oe the F ifth Cikcuit

No. 23,474

D on H amer, et al.,

-v.-

Appellants,

George Musselwhite, Individually and as Chief of Police

of the City of Lexington, Mississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

This appeal challenges the constitutionality of an ordi

nance of the City of Lexington, Mississippi, prohibiting all

parades on Yazoo Street, Depot Street, Carrollton Street

and Court Square in that city. Appellants contend that

the ordinance is enforced in such a manner as to license

federally guaranteed rights of free expression at the un

fettered discretion of city authorities; that the ordinance

is a vague and overbroad regulation of expression; and

that, in any event, the First and Fourteenth Amendments

are violated by a blanket ban of all demonstration activi

ties in the only areas of a small town where demonstrations

can effectively convey ideas and grievances.

2

Appellants, plaintiffs below, filed their complaint for de

claratory and injunctive relief on May 26, 1965 (E. 1-7).

They alleged that they were Negro residents of the City

of Lexington and persons residing in Lexington and Holmes

County (of which Lexington is the county seat) who de

sired “to exercise their federally protected rights of free

expression by conducting in the City of Lexington, Missis

sippi, peaceful parades, assemblies and demonstrations to

encourage Negro citizens of Lexington and Holmes County,

Mississippi to register to vote in local, state and national

elections, and to protest the racial discrimination which

they believe is practiced by the voting registration officials

of Holmes County, Mississippi” (E. 2-3). On behalf of

themselves and their class, they sought a declaration of

unconstitutionality of an ordinance of October 3,1961 [here

after called the 1961 ordinance] which prohibited parades

on Court Square and Yazoo, Carrollton and Depot Streets

without written permission of the Mayor and Marshal of

Lexington (E. 4-5). This ordinance is set out at E. 9-11.

They also asked that appellees, city and county officials who

were defendants below, be enjoined from enforcing that

ordinance (E. 3-4, 7). Their complaint averred that the

office of the county registrar where residents of Holmes

County must register to vote is located in Court Square

in the City of Lexington, and that Yazoo, Carrollton and

Depot Streets intersect Court Square (E. 5).

The case was set for hearing June 2, 1965 on appellants’

application for a preliminary injunction. On June 1, 1965

the Mayor and Board of Aldermen of the City of Lexing

ton met, repealed the 1961 ordinance, and replaced it with

the ordinance [hereafter called the 1965 ordinance] whose

constitutionality is now in contention. That ordinance, set

3

out at R. 18-20, provides that “parades on Yazoo Street,

Depot Street, Carrollton Street and Court Square in the

City of Lexington, Mississippi, are hereby prohibited and

are hereby ordained to be unlawful” (E. 18). Its constitu

tionality was assailed by a supplemental complaint filed

June 11, 1966, in which plaintiffs alleged that because

“Yazoo Street, Depot Street, Carrollton Street and Court

Square in the City of Lexington are the main thorough

fares of the city and constitute that area in the city where

the expression of views by peaceful parades, demonstra

tions and assemblies are likely to come to the attention of

the residents, public officials and voting registration au

thorities of the city, the prohibition of parades on those

thoroughfares is a constitutionally impermissible restric

tion of the freedom of expression of the plaintiffs and the

class which they represent” (R. 14).

By their answer, appellees admitted their identity, the

dates of passage and the texts of the 1961 and 1965 ordi

nances, the location of the county registrar on Court

Square, the intersection with Court Square of Yazoo, Car

rollton and Depot Streets, and the correctness of a map

of the City of Lexington annexed to the original complaint;

they denied all other pertinent allegations of the original

and supplemental complaints (R. 20-25). The case then

came on for hearing before the Honorable Dan M. Bussell,

and by testimony and exhibits of the parties the following

relevant facts were adduced:

Lexington, the county seat of Holmes County, abuts the

Mississippi Delta and is 60 miles north of Jackson, Mis

sissippi, and 160 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee (page

3 of the Comprehensive City Plan of Lexington, Mississippi,

Exhibit D-2, hereafter referred to as CP). In 1960 its

4

population was 2839, including 1480 nonwliites and 1359

whites (E. 141; CP 27), a decline from 3198 in 1950 (E. 141;

CP 19). Holmes County numbered 27,097 persons in 1960

(CP 19), including 7595 whites and 19,501 nonwhites (CP

27), 19 per cent below the 1950 census figure of 33,301

(CP 19).

The center of Lexington is the county courthouse, sur

rounded on its four sides by Court Square (E. 29). Traffic

from several local streets and from the two state highways

that pass through Lexington converges on the square (E.

29, 5; Exhibit B of the complaint; Exhibit P-8; CP 15).

State Highway No. 17, which enters the city from the south

as Yazoo Street, and State Highway No. 12 (connecting

the area with U. S. Highways No. 49, 51 and Interstate 55

(CP 43)), which enters from the east as Depot Street, inter

sect at the square and continue north as Carrollton Street

until they separate .56 of a mile within the city limits

(E. 29, 30, 61, 110, 126; Exhibit P-8).

A comprehensive plan for future expansion of Lexington

was completed April 29, 1965 by Michael Baker, Jr., Inc.

of Jackson (E. 32, 100,108). Included in the plan is a traffic

survey. The survey states that the principal problem is

congestion caused by parking on arterial streets, narrow

ness of streets and the conflict between local and through

traffic (E. 32, 108-110, 131; CP 61-72). It is said to indi

cate (although the printed comprehensive plan does not so

state) that an average of 6000 cars come into Court Square

daily (B, 31, 100) and it estimates (on the basis of national

statistics) that 49 per cent of them are destined for points

other than Lexington (CP 61).

The survey does not include an hourly count that records

the difference between peak-load and slack-time traffic (E.

5

132); nor does it differentiate between weekday and week

end traffic. Hundreds of laborers from Tchula, Mississippi,

and Lexington pass through Court Square going to and

returning from plants in Durant, Mississippi, and Lexing

ton (R. 141). They probably make weekday traffic in the

early morning and late afternoon heavier than traffic dur

ing the rest of the day or on weekends. There is no indi

cation in the comprehensive plan that parades held from

1961 to 1965 (R. 32) contributed to traffic congestion in

Lexington.

In 1950 the Lexington Board of Aldermen, concerned

about congestion, authorized a study which resulted in a

one-way pattern around Court Square. Subsequently, some

60 parking spaces were eliminated from the downtown area

(R. 31). Although Lexington in 1965 still had many more

parking spaces in its business district than a city its size

needs (CP 71), little else has been done to improve the

parking problem or to make the city’s streets easier to

travel.

Lexington’s fire station and hospital are centrally located

—the fire station two blocks north of Court Square on

Tchula Street (R. 112-113), and the hospital at the western

end of Spring Street (R. 84, 114; Exhibit P-8). But emer

gency vehicles are limited in the streets they can use to

answer calls in many parts of the city. Ambulances and fire

engines answering calls in the eastern and northern sec

tions of Lexington must use Depot and North Carrollton

Streets respectively (R. 113, 114). Fire engines answering

calls in the southern part of the city must use Yazoo Street

(R. 113), as must ambulances returning from calls in that

area (R. 114). Ambulances answering emergencies in the

southern section use Spring Street (R. 114). Again, there

6

is no indication in the comprehensive plan or in the record

that parking has been forbidden or limited on any major

street the fire engines and ambulances must use. To the

contrary, the photographic exhibits show Depot, North Car

rollton, Yazoo and Spring Streets metered for parking and

lined by parked cars (P-1 through P-4, P-6).

Lexington’s Negro residential areas are Pecan Grove,

south of Court Square (R. 56; “X” on Exhibit P-9); Bal

ance Due, also south of Court Square but outside the city

limits (R. 56, 113; “Y” on Exhibit P-9); Sehoolhouse Bot

tom, east of Court Square (R. 56-57; “Z” on Exhibit P-9) ;

and Church Street, north-northwest of Court Square (R.

57; “W” on Exhibit P-9). Yazoo Street is the only street

that Negro demonstrators from Pecan Grove or Balance

Due can use to reach the federal registrar’s office, the Post

Office or Court Square, where the courthouse, county regis

trar and Federal Bureau of Investigation are located (R.

5, 58-59, 93; Exhibit P-8). Marchers who want to reach

Court Square from Church Street must use North Carroll

ton Street (R. 59).

Court Square is the center of county government and is

the city’s commercial district (R. 31). It is the most suit

able part of the city for parades and demonstrations (R.

60). Only five per cent of Lexington’s developed land is

devoted to commercial use, and almost all of it is located

on or near Court Square (R. 60, 86, 100, 115-116; CP 10).

Lexington’s other commercial activity is on Yazoo Street

and to a lesser degree on Depot and North Carrollton

Streets (R. 60, 86; CP 10). Spring Street, on which some

parading might be feasible (R. 60), is predominantly resi

dential and has a very much smaller population than the

streets covered by the ordinance (R. 83, 85, 92).

7

The Lexington comprehensive plan makes no mention of

commercial activity in the city except on Court Square and

the streets covered by the ordinance (CP 10), indicating

that no other part of the city is suitable for parading.

When the Lexington High School Band and Negro 4-H

Club paraded in the city from 1961 to 1965, they always

paraded around Court Square (E. 119, 121).

Discrimination against Negroes is commonplace in Lex

ington and Holmes County. There are separate educational

facilities for Negroes from elementary school through

junior college (E. 142; CP 78). And Holmes County is

under a three-judge federal injunction to enforce a pro

vision of the 1960 Civil Eights Act relating to preserva

tion and inspection of election records. Katzenbach v.

McClellan, 341 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1965).1

In Holmes County, as of January 1, 1964, there were 4773

whites over age twenty-one, 4800 (or 100+ per cent) of

whom were registered to vote. At the same time there were

8757 Negroes over age twenty-one, 20 (or .23 per cent) of

whom were registered to vote.2 On October 29, 1965, United

States Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbaeh, in ac

cordance with Section Six of the Voting Eights Act of

1965 (Public Law 89-110), certified that in his judgment

the appointment of examiners was necessary to enforce the

1 See also Alabama ex rel. Gallion v. Rogers, 187 F. Supp. 848

(M. D. Ala. 1960), aff’d sub nom. Dinkens v. Attorney General, 285

F- 2d 430 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, Dinkens v. Rogers, 366 U. S.

913 (1961); Kennedy v. Owen, 321 F. 2d 116 (5th Cir. 1963).

2 IT. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Voting in Mississippi 71 (Ap

pendix C, 1965).

8

guarantees of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States in Holmes County, Mississippi.3

There are three federal registrars in Holmes County

(R. 51, 76), located at the Post Office in Lexington (R. 58;

“V” on Exhibit P-9). The federal registrars were in

Lexington for one week prior to the hearing in the district

court in this case. During that week about 330 Negroes

registered to vote (R. 76).

Since 1955 the Mayor and Board of Aldermen of Lex

ington have passed three parading ordinances. May 3, 1955

an ordinance was passed prohibiting all parades on Yazoo,

Depot and Carrollton Streets and on Court Square (R. 32,

103-105).4 The 1955 ordinance was replaced October 3,

1961 by an ordinance that allowed parades on the three

streets and the Court Square so long as they were approved

by the Mayor and City Marshal (R. 10-11).5 On June 1,

1965—the day before appellants’ attack on the 1961 ordi

nance was set for hearing—that ordinance was repealed and

replaced by the present one (R. 18-20).6

J. William Moses, a defendant in this case (R. 1) and a

member of the Board of Aldermen of Lexington for nine

years prior to the hearing (R. 99), testified on the passage

3 30 Federal Register No. 211, at 13849 (1965).

4 Book 9, p. 290, Minutes of the Mayor and Board of Aldermen

of the City of Lexington; Book 2, p. 164 of the Ordinances of the

City of Lexington.

5 Book 10, p. 157, Minutes of the Mayor and Board of Aldermen

of the City of Lexington; Book 2, p. 182 of the Ordinances of the

City of Lexington.

6 Book 10, p. 440, Minutes of the Mayor and Board of Aldermen

of the City of Lexington; Book 2, id. 242 of the Ordinances of the

City of Lexington.

9

and repeal of the ordinances. The 1955 ordinance, Moses

said, expressed the same concern about traffic congestion

that was first felt by the Aldermen in 1950 when they cre

ated a one-way traffic pattern around Court Square (R.

101-102). He said that pressure brought by citizens who

wanted the new Lexington High School Band to parade in

the downtown area led to replacement of the 1955 ordinance

in 1961. After passage of the 1961 ordinance several

parades were held, not only by the high school band, but

also by the Holmes County Negro 4-H Club (R. 106, 119-

120) .

Moses’ explanations for enactment of the 1965 ordinance

were somewhat inconsistent. He stated that the 1961 ordi

nance was repealed in 1965 and replaced by the present

ordinance “mostly on the advice of our City Attorney”

(R. 107) after the legality of the 1961 ordinance had been

attacked (R. 122) by appellants (R. 1-7). Other than this

litigation, there was no pressure to repeal the 1961 ordi

nance, and prior to suit, no repeal measures had been

proposed before the Board of Aldermen (R. 123-124). But

Moses also appears to say that between 1961 and 1965 the

Board of Aldermen discussed the 1961 ordinance and its

effect on traffic,7 and that traffic congestion—not advice of

counsel stemming from the lawsuit—was the primary cause

for repealing that ordinance in 1965 and enacting the pres

ent one (R. 117, 135, 137). The short of it seems to be

that the 1961 ordinance was repealed on the advice of city

counsel after appellants’ attack on it, if not because of that

7 Moses’ testimony is confused at this point, and it is likely that

he is referring to the 1955 ordinance, not the 1961 ordinance, when

he asserts that frequent Board discussion preceded repeal (R. 134-

135; compare R. 123-124).

10

attack, and that the present ordinance was enacted to fill

the gap left by repeal (R. 121-124). Moses testified that in

his opinion it is not now feasible to have parades along

the thoroughfares where they are prohibited by the ordi

nance (R. 139). There is nothing in the comprehensive

plan, submitted while the 1961 ordinance permitting li

censed parades was in effect, to support this position.

Moses also gave his interpretation of the ordinance.

He said that it did not apply to sidewalks (R. 33)8 or to

shoulders of streets (R. 116, 139), although he did state

that shoulders are technically part of the street (R. 128).9

In response to questions by his attorney, Moses not only

reiterated that there was no intent by the Aldermen to

prohibit parading on sidewalks or shoulders adjacent to

streets included in the ordinance (R. 116-117, 139), but

8 But see the letter opinion of Judge Cox, August 20, 1965 in

Guyot v. Pierce, S. D. Miss., Civil Action No. 3754 (J) appearing at

pp. 79-89 of the Printed Record of Guyot v. Pierce, 5th Cir., No.

22,990, in which he sustained the application of a Jackson, Missis

sippi, ordinance regulating certain conduct in the “streets” to side

walk marches, on the ground that “a sidewalk is but a portion of

the street itself” (at p. 86), citing Section 8137(d) of the Missis

sippi Code (1942), and 40 Words and Phrases (permanent Ed.)

421-426.

9 On Carrollton Street there is a sidewalk from Court Square

north to the point where State Highways 12 and 17 separate (R.

126; “D” on Exhibit P-9). From there to the city limits, there is

no sidewalk (R. 127). On Yazoo Street there is a sidewalk from

Court Square south to the railroad track (R. 127; “sidewalk ends”

on Exhibit P-9). From the railroad track to the city limit—the

north bank of Black Creek—there is an eight to ten foot shoulder

adjacent to the paved street (R. 128). If shoulders are construed

to be part of the street, Negroes are precluded from gathering in

parade formation in Pecan Grove or Balance Due, Negro residential

areas (R. 56), because there is only a shoulder on Yazoo Street

there (Exhibit P-9). Instead, they would have to assemble away

from their usual meeting places at a place where there is a side

walk.

11

also said that if appellants want to parade “they have the

cooperation and the help and support, and, also, the pro

tection of the City of Lexington” (E. 139). But Moses

affirmed that it was the intent of the ordinance to prevent

the crossing of Court Square, a designated street, by

marchers who want to parade at the courthouse within the

square (R. 140). In Moses’ view, parading and assembly in

front of the courthouse, as well as on the square surround

ing it, is effectively prohibited.

Moses was asked on cross-examination what constituted

a parade. He said that “parade” connoted an organized

group under some direction “marching along,” but he was

unable to specify how large a group constituted a parade.

He said that 500 civil rights workers would be a parade,

but three people organized and marching down the street

would not. He was uncertain about five people doing the

same thing (E. 123-124).

Subsequent to enactment of the present ordinance, about

500 Negro civil rights demonstrators paraded on Yazoo

Street and in Court Square (R. 30-31). Every heavily

populated Negro section of Lexington was represented (R.

77). The march originated at the Freedom Democat[ic

Party] Office (R. 87) in Pecan Grove (R. 30-31, 82). The

demonstrators marched north along Yazoo Street, on the

shoulder of the road or on the sidewalk where there was

a sidewalk (R. 82-83), two abreast, in a column about four

blocks long (R. 30-31, 78, 88, 116). They crossed Court

Square and, on the lawn, encircled the courthouse (R. 30-

31, 77-78, 88).

During the parade, which lasted four hours (R. 77), the

marchers sang, prayed (R. 30-31, 79) and carried placards

12

saying “We support the Freedom Democratic Party Con

gressional Challenge” (R. 80). No handbills were distrib

uted and there were no speeches (R. 79). After the parade

the marchers again crossed Court Square and walked down

Yazoo Street to Pecan Grove where the group disbanded

(R. 30-31, 89).

The Lexington officials were told of the parade before

it took place (R. 33, 140). The officials met with the police

department prior to the march and instructed them to give

every assistance to the paraders (R. 140). There was “no

intention from the very beginning to arrest anybody” (R.

141). One policeman directed pedestrian and vehicular

traffic at the square while others, perhaps auxiliary police,

observed spectators and activities on the courthouse lawn

(R. 31, 33, 89-90, 115, 140).

During the parade no civil rights demonstrators were

arrested, threatened or harassed by city officials, police

or spectators (R. 31, 96). Several Negroes feared, however,

that they would be arrested because the ordinance pro

hibited parading on Yazoo Street and Court Square, and

some did not participate in the march who would have

done so if there were no ordinance (R. 90, 91, 96-97).

Specifications o f Error

1. The court below erred in refusing to declare the pres

ent Lexington ordinance prohibiting all parades on Lex

ington’s arterial streets and Court Square offensive to the

First and Fourteenth Amendments as a device for the

licensing of constitutionally protected expression in the

unfettered discretion of the Lexington Board of Aldermen,

police and other city officials.

13

2. The court below erred in refusing to declare the

present Lexington ordinance prohibiting all parades on

Lexington’s arterial streets and Court Square unconsti

tutional as a vague and overbroad regulation of expression.

3. The court below erred in refusing to declare the pres

ent Lexington ordinance prohibiting all parades on Lexing

ton’s arterial streets and Court Square an unconstitutional

abridgment of appellants’ First and Fourteenth Amend

ment guarantees of free speech, assembly and petition.

A R G U M E N T

The Present Lexington Ordinance Prohibiting All

Parades on Lexington’s Arterial Streets and Court Square

Is Offensive to the First and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution o f the United States Because

A. T he O rdinance Is E nforced in the U nfettered

D iscretion o f City Officials.

The 1961 Lexington ordinance allowed parades on Yazoo,

Depot and Carrollton Streets and Court Square so long as

they were approved by the Mayor and City Marshal. That

ordinance was attacked by appellants in a complaint tiled

May 26, 1965. It is clear that the 1961 ordinance was un

constitutional under principles settled since 1939. As Judge

Russell said of it below:

[PJlaintiffs contend that it [the 1961 ordinance] was

unconstitutional in that it placed the power to issue

parade permits in the discretion of two delegated city

officials. The invalidity of ordinances requiring per

mits of this type has been upheld by the Supreme Court

14

in such cases as Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 [1938];

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 [1939]; Cantwell v.

Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 305 [1940]; and Runs v.

New York, 340 U. S. 290 [1951]. Defendants concede

. . . that it was discriminatory; hence its repeal (E.

33-34).

June 1, 1965, the day before hearing on appellants’

motion for preliminary injunction of the 1961 ordinance,

that ordinance was repealed and replaced by the present

one (R. 18-20). But the change from the overtly discre

tionary 1961 ordinance to the 1965 ordinance was only a

paper change. Ostensibly, the present ordinance invests

no discretion in city officials. It bans all parades in the

downtown area. Never was the appearance of reformation

bought so cheaply. For in its application the new ordinance

still permits the same unfettered discretion and potential

for discrimination on the part of city officials which marred

the old.

This fact is plainly established by the record. Shortly

after the 1965 ordinance was passed, and while the present

case was pending for trial in the district court, more than

500 Negroes demonstrated in the forbidden streets of

Lexington (R. 30-31, 76-80, 87-90, 115-116, 140-141). Their

parade, lasting four hours (R. 77), originated at the Free

dom Democrat[ic Party] Office (R. 87) in Pecan Grove, a

Negro residential section of Lexington (R. 30-31, 82).

Marching two abreast, in a column about four blocks long,

the demonstrators walked north on Yazoo Street to Court

Square, where they crossed the intersection and encircled

the Courthouse on the lawn, singing, praying and carrying

placards (R. 30-31, 77-78, 79, 80, 88).

15

The Lexington city officials had been told of the parade

well before its occurrence. They met with the police depart

ment prior to the parade and decided that they would let

this one take place. Police were instructed in advance to

render the marchers “every assistance that they wanted”

(R. 140), “all the assistance in the world that they needed

to expedite the crossing of these people across the street

as much as possible” {ibid.). When the parade came, one

policeman directed pedestrian and vehicular traffic at Court

Square, others observed spectators and activities on the

courthouse lawn (R. 31, 33, 89-90, 115, 140). During the

parade no civil rights demonstrators were arrested. As

Moses put it: “No person was arrested and no intention

from the very beginning to arrest anybody” (R. 141).

This deliberate decision, made before the parade, at a

time when the record does not suggest that city officials

knew whether the marchers would use the sidewalk or the

roadstead of Yazoo Street, or ring Court Square on the

outside or the inside, clearly demonstrates the City’s con

ception of the new ordinance. It is. to be enforced or not

as officials think appropriate. A blanket ban in form, it is

a licensing provision in fact. Tactical considerations and

whatever arbitrary or discriminatory urges city officials

may feel it safe to exercise determine the enforcement of

this post litem motam law. The uncontrolled discretion

expressly given by the 1961 ordinance has been perpetu

ated, with the sole difference that it rests now not in the

hands of two designated officers, but in the hands of an

unascertainable clique of officials and policemen.

This is constitutionally impermissible. “Although this

Court has recognized that a statute may be enacted which

16

prevents serious interference with normal nse of streets

and parks . . ., we have consistently condemned licensing

systems which vest in an administrative official discretion

to grant or withhold a permit upon broad criteria unrelated

to proper regulation of public places.” Kuns v. New York,

340 U. S. 290, 293-294 (1951). It matters not whether that

discretion be given on the face of the statute books or by

practice and usage. Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268

(1951). The covert preservation of licensing or dispensing

power by the city officials of Lexington—a power governed

by no set standards or regulations—places this case

squarely under the ban of Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536

(1965). In Cox, civil rights demonstrators were arrested

and convicted under a statute which, like the present Lex

ington ordinance, contained no language of discretion:

No person shall wilfully obstruct the free, convenient

and normal use of any public sidewalk, street, high

way, bridge, alley, road, or other passageway, or the

entrance, corridor or passage of any public building,

structure, watercraft or ferry, by impeding, hindering,

stifling, retarding or restraining traffic or passage

thereon or therein . . . (379 U. S. at 553).

In holding the statute unconstitutional as applied, the

Court said:

We have no occasion in this case to consider the con

stitutionality of the uniform, consistent, and nondis-

criminatory application of a statute forbidding all

access to streets and other public facilities for parades

and meetings. Although the statute here involved on

its face precludes all street assemblies and parades, it

has not been so applied and enforced by the Baton

17

Bouge authorities. City officials who testified for the

State clearly indicated that certain meetings and

parades are permitted in Baton Bouge, even though

they have the effect of obstructing traffic, provided

prior approval is obtained. This was confirmed in oral

argument before this Court by counsel for the State.

He stated that parades and meetings are permitted,

based on “arrangements . . . made with officials.” The

statute itself provides no standards for the determina

tion of local officials as to which assemblies to permit

or which to prohibit. Nor are there any administrative

regulations on this subject which have been called to

our attention. From all the evidence before us it ap

pears that the authorities in Baton Bouge permit or

prohibit parades or street meetings in their completely

uncontrolled discretion.

The situation is thus the same as if the statute itself

expressly provided that there only could be peaceful

parades or demonstrations in the unbridled discretion

of the local officials. The pervasive restraint on free

dom of discussion by the practice of the authorities

under the statute is not any less effective than a stat

ute expressly permitting such selective enforcement . . .

Also inherent in such a system allowing parades or

meetings only with prior permission of an official is the

obvious danger to the right of a person or group not

to be denied equal protection of the laws . . . It is

clearly unconstitutional to enable a public official to

determine which expressions of view will be permitted

and which will not or to engage in invidious discrimi

nation among persons or groups either by use of a

statute providing a system of broad discretionary li

censing power or, as in this case, the equivalent of such

18

a system by selective enforcement of an extremely

broad prohibitory statute (379 U. S. at 555-558).

It is true that in the present case, the discretionary char

acter of the 1965 ordinance was exemplified by a dispensa

tion in favor of civil rights groups. This has no legal signif

icance. Cf. Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 559, 568-573 (1965).

A licensing scheme is not rendered constitutional whenever

the licensor chooses temporarily to be benign. Non-enforce

ment of the ordinance against civil rights demonstrators on

one day—during the pendency of a lawsuit brought by them

to challenge it—does not guarantee non-enforcement against

them on another. Rather, so long as the ordinance is ap

plied in the selective manner which Lexington officials have

adopted, the fear that it will be applied diseriminatorily

against the appellants is substantial. Negroes are still

politically disadvantaged in Lexington. Federal registrars

have had to be sent to Holmes County to enforce the guar

antees of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution.10

Although the repeal of the 1961 ordinance and allowance

of a parade after appellants went to court may have marked

a tactical retreat for a time, there is every reason to believe

that the new ordinance leaves appellants in the same jeop

ardy of discrimination which they sued to escape. Clearly

they are entitled to an injunction.11

10 30 Federal Register No. 211, at 13849 (1965).

11 In the court below, appellees interposed a number of objections

to reaching the constitutional merits of the controversy. They con

tended that the proceeding was not a proper class action, and re

quested abstention in favor of the Mississippi state courts (R. 21).

Judge Russell, however, passed over these points and decided the

case squarely on the constitutional ground. Ample authority sus

tains his power, indeed, his obligation, to do so. Baggett v. Bullitt,

377 U. S. 360 (1964) ; DombrowsM v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ;

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F. 2d 649 (5th Cir. 1963) ;

19

B . The O rdinance Is a Vague and Overbroad

R egulation o f E xpression.

The 1965 ordinance challenged here provides that

“parades on Yazoo Street, Depot Street, and Carrollton

Street and Court Square in the City of Lexington, Missis

sippi, are hereby prohibited and are hereby ordained to

be unlawful” (E. 18). But the ordinance neither defines

nor indicates what constitutes the “street” and what quali

fies as a “parade.” Instead, the citizen can only guess what

behavior will result in his arrest under the ordinance.

J. William Moses, a member of the Board of Aldermen

for nine years prior to the hearing (E. 99), gave his in

terpretation of the ordinance to the court below. His testi

mony indicates its uncertainties.

Moses said that the ordinance does not apply to sidewalks

(E. 33), or to shoulders of streets (E. 116, 139). His state

ment that sidewalks are not part of the streets is hardly

comforting in light of cognate developments in the city

of Jackson, Mississippi, where hundreds of civil rights

demonstrators marching on the sidewalks were arrested

for purported violations of an ordinance regulating “Cer

tain Uses of the Streets,” and United States District Judge

Cox sustained this application of the ordinance on the

ground that “a sidewalk is but a portion of the street itself.”

Guyot v. Pierce, letter opinion of August 20, 1965.12 As for

N.A.A.G.P. v. Thompson, 357 F. 2d 831 (5th Cir. 1966); Williams

v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M. D. Ala. 1965). On this appeal,

therefore, appellants believe that the only issue fairly presented is

the constitutional validity of the Lexington ordinance on its face

and as applied.

12 Civil Action No. 3754(J), appearing at p. 86 of the Printed

Record of Guyot v. Pierce, 5th Cir., No. 22,990.

20

unpaved shoulders, which Moses himself conceded were

technically part of the street (R. 128), coverage of these

precludes Negroes from assembling in parade formation

for a march to Court Square from their residential areas

of Pecan Grove and Balance Due (R. 56), for Yazoo Street

—the only route to Court Square (R. 58-59)—at these points

has no sidewalk, only a shoulder (R. 127; Exhibit P-9).

For Negroes in these sections, then, every march runs an

unascertainable risk of prosecution.

Moses was also uncertain about what constitutes a

“parade.” He said that “parade” connoted an organized

group under some direction “marching along,” but was un

able to specify how large a group “marching along” con

stituted a “parade” (R. 123-124). If traffic congestion is

the city’s concern, surely some specification of the number

of marchers which occasions that concern is not impracti

cable.

Standards of permissible statutory vagueness are strict

in the area of free expression . . . Because First Amend

ment freedoms need breathing space to survive, gov

ernment may regulate only with narrow specificity

(.N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 432-433 (1963)).

The threat of criminal prosecution of any citizen who

guesses wrongly the boundaries of his constitutional free

doms serves effectively to coerce the citizen to obey even

lawless police orders and surrender through fear his con

stitutional use of the streets. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U. S. 88, 97-98 (1940); Bantam Boohs, Inc. v. Sullivan,

372 TJ. S. 58, 66-70 (1963); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S.

479, 494 (1965). The one civil rights demonstration that did

take place after enactment of the 1965 ordinance lost

21

strength because Negroes feared that they would be arrested

(R. 90, 91, 96-97), even though the marchers paraded up

to Court Square on the shoulders and later the sidewalks

of Yazoo Street (R. 82-83). This ordinance is so vague

that it prevents citizens from exercising their freedom of

expression because of fear of arrest. It should be declared

unconstitutional and void.

C. T he O rdinance Abridges A ppellants’ C onstitutional

G uarantees o f Free Speech, A ssem bly and Petition .

Freedom of assembly clearly extends to the public streets,

and parading in the streets has been approved by the

courts. As Justice Roberts wrote in Hague v. C. I. 0., 307

U. S. 496, 515 (1939):

Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they

have immemorially been held in trust for use of the

public and, time out of mind, have been used for pur

poses of assembly, communicating thoughts between

citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of

the streets and public places has, from ancient times,

been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights and

liberties of citizens. . . .

This statement was approved by the majority of the

Court in Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558, 561 (1948), and

in Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147, 163 (1939), the Court

saying:

It is suggested that . . . ordinances are valid because

their operation is limited to streets and alleys and

leaves persons free to distribute printed matter in

other public places. But . . . the streets are natural

and proper places for the dissemination of information

22

and opinion; and one is not to have the exercise of his

liberty of expression in appropriate places abridged on

the plea that it may be exercised in some other place.

See also Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 105-6 (1940);

Jones v. Opelika, 316 II. S. 584, 615 (1942), dissent adopted

on rehearing, per curiam, 319 U. S. 103 (1943); Kuna v.

New York, 340 U. S. 290, 293 (1951).

These decisions recognize that denial of access to the

streets as a place of public communication may often

amount to denying the large underprivileged portions of the

population every effective means of political expression.

‘ Freedom of speech . . . [is] available to all, not merely

to those who can pay their own way.” Murdock v. Penn

sylvania, 319 U. S. 105, 111 (1943); cf. Martin v. City of

Struthers, 319 U. S. 141, 146 (1943).

Laws which hamper the free use of some instruments

of communication thereby favor competing channels . . .

There are many people who have ideas they wish to

disseminate but who do not have enough money to

own or control publishing plants, newspapers, radios,

moving picture studios, or chains of show places . . .

In no other way except public speaking can the desir

able objective of widespread public discussion be as

sured . . . the right to freedom of expression should

be protected from absolute censorship for persons

without, as for persons with, wealth and power. (Mr.

Justice Frankfurter, concurring, in Kovacs v. Cooper,

336 U. S. 77, 102-4 (1949).)

The present Lexington ordinance on its face imposes a

total prohibition on all parades in the downtown area of

23

the city—the only suitable place in the city for parading

and demonstrating (R. 60).13 The main thoroughfares of

the city constitute that area where the expression of views

is most likely to come to the attention of the residents,

public officials and voting registration authorities of the

city and county. The commercial and government center

of Lexington is Court Square. The courthouse, county reg

istrar and Federal Bureau of Investigation are located

there (R. 5, 58-59, 93; Exhibit P-8), as is almost all of

Lexington’s developed land devoted to commercial use (R.

60, 86, 100, 115-116; CP 10).14 And commercial activity not

on the square is on Yazoo, Depot or North Carrollton

Streets (R. 60, 86; CP 10).

In addition to prohibiting parades on Yazoo Street, Depot

Street, Carrollton Street and Court Square (R. 18), it was

the intent of the 1965 ordinance, Moses testified, to pre

vent a parade from crossing Court Square, thus precluding

demonstrations on the courthouse lawn (R. 140). All of

these prohibitions clearly violate appellants’ constitutional

guarantees of freedom of speech and assembly.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press, -which

are protected by the First Amendment from infringe

ment by Congress, are among the fundamental personal

rights and liberties which are protected by the Four

13 See Statement of the Case, pp. 4-7, supra.

14 Only five per cent of Lexington’s developed land is devoted to

commercial use (CP 10) and there is no indication in the Compre

hensive Plan that there is any commercial activity on streets not

covered by the ordinance.

24

teenth Amendment from invasion by State action . . .

It is also well settled that municipal ordinances adopted

under state authority constitute state action and are

within the prohibition of the amendment. (Lovell v.

Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 450 (1938).)

The right of peaceable assembly is a right cognate

to those of free speech and is equally fundamental. . . .

[Consistently with the Federal Constitution, peaceable

assembly for lawful discussion cannot be made a crime.

The holding of meetings for peaceful political action

cannot be proscribed. (DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S.

353, 364-5 (1937).)

See also Terwimiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4 (1949);

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513, 521 (1958).

Appellants recognize that the State has authority to enact

laws to promote the health, safety, morals and general wel

fare of its people. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697, 707

(1931); Carlson v. California, 310 U. S. 106, 113 (1940).

But this authority may not be used as a guise to deprive

people of their constitutional rights of freedom of speech

and assembly.

We must recognize . . . that regulation of “conduct”

has all too frequently been employed by public au

thority as a cloak to hide censorship of unpopular

ideas . . . (Commimications Ass’n v. Douds, 339 U. S.

383, 399 (1950)) . . . . [A] State may not unduly sup

press free communications of views . . . under the

guise of conserving desirable conditions. (Cantwell

v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308 (1940).)

25

The purported justification for the 1965 ordinance is

that it will alleviate traffic congestion in the downtown area

of the city (R. 18-20, 117, 135, 137). The traffic survey, com

piled as part of a comprehensive plan for future expansion

of Lexington, indicates that an average of 6000 vehicles

pass through Court Square daily (R. 31, 32, 100, 108) and

is said to show the need for the prohibition of parades. But

the traffic survey does not even mention parades as a cause

of congestion; nor is there any other evidence that the

parades held in Lexington from 1961 to 1965 (R. 32) con

tributed to the problem. Instead, parking on arterial

streets, narrowness of streets and a conflict between local

and through traffic were cited as the causes of congestion

(R. 32, 108-110, 131; CP 61-72). We are told that the

reason these problems are not confronted directly is that

local merchants object to traffic regulation which might

affect their commercial business (R. 110-112, 128-132, 137).

To protect this commercial interest, the city of Lexington

has subordinated federally guaranteed freedoms. No deci

sion of the Supreme Court of the United States counte

nances any such balance. See Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S.

501, 509 (1946). To the contrary, the Court has reiterated

that nothing short of the most serious threats to the pub

lic welfare justify abridgment of free speech and assembly.

“ [Ojnly considerations of the greatest urgency can justify

restrictions on speech. . . . ” Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S.

513, 521 (1958).

Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression

of free speech and assembly. . . . Only an emergency

can justify repression . . . . Moreover, even imminent

danger cannot justify resort to prohibition of these

functions essential to effective democracy, unless the

26

evil apprehended is relatively serious. Prohibition of

free speech and free assembly is a measure so strin

gent that it would be inappropriate as the means for

averting a relatively trivial harm to society. (Whitney

v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 376-377 (1927), Justices

Brandeis and Holmes concurring.)

See also Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147, 162-163 (1939);

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 95-6 (1940); Bridges

v. California, 314 U. S. 252, 262-3 (1941); Board of Educa

tion v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, 639 (1943); Thomas v.

Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530 (1945); N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U. S. 415, 439 (1963).

The mere slowing of vehicular traffic, especially in a

city through which only 6000 cars pass on an average day

(R. 31, 100), does not warrant blanket abridgment of free

speech and assembly. In Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 229 (1963), the Supreme Court held that a demon

stration of 187 Negro students in protest of deprivation of

civil rights could not be prohibited, notwithstanding the

protest caused traffic to slow down at a nearby intersection.

The Court said that such a prohibition would violate the

demonstrators’ rights of free speech and assembly. The

possible slowing of cars in Lexington caused by a parade is

a precisely apt example of the “relatively trivial harm to

society” spoken of by Justices Brandeis and Holmes in

Whitney, supra.

Marches similar to the activities which appellants wish

to conduct have been given constitutional protection by

this Court, N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 357 F. 2d 831, 841 (5th

Cir. 1966), at least so long as they do not deprive the public

of police and fire protection.

27

. . . [I] t lias long been settled, indeed from begin

ning, that a citizen or group of citizens may assemble

and petition for redress of their grievances. . . . A

march to the City Hall in an orderly fashion, and a

prayer session within the confines of what plaintiffs

seek would appear, without more, to be embraced in

this right. . . . And these rights to picket and to

march and to assemble are not to be abridged by arrest

or other interference so long as asserted within the

limits of not unreasonably interfering with the rights

of others to use the sidewalks and streets, to have

access to store entrances, and where conducted in such

manner as not to deprive the public of police and fire

protection. (Kelly v. Page, 335 F. 2d 114, 118-119 (5th

Cir. 1964).)

Moses’ testimony below that fire and ambulance service

to several parts of the city can be effected only by using

the streets on which the ordinance prohibits parades (R,

113, 114) unquestionably deserves consideration. But it

will not support wholesale denial of appellants’ rights of

free speech and assembly on these streets. There is no

showing that demonstrations on Lexington’s main streets

and Court Square would impede fire engines and ambu

lances. On the contrary, in the one parade that was held

after the 1965 ordinance was passed, the participants

marched two abreast on the sidewalk (R. 30-31), leaving

ample space for other pedestrians and the whole roadstead

to emergency vehicular equipment and other traffic. Lex

ington’s concern for the free movement of its ambulances

and fire engines does not justify blanket prohibition of

parading in the downtown area. Regulations limited in

their application to emergency situations can surely be

28

drawn that will be effective without infringement of con

stitutional guarantees.

In general, the facts of cases that recognize a municipal

ity’s power to restrict freedom of speech and assembly on

its streets are far removed from the facts in this case. In

contrast to Lexington—with a population of 2839 (R. 141;

CP 27) and with 6000 cars passing daily through the

Court Square (R. 31-32)—those cases involved cities with

large populations and serious traffic congestion.15

This is not to say that Lexington is entitled to impose

no restraints upon the uses of its sidewalks and roadsteads.

But an absolute prohibition of parading on all major streets

is a constitutionally excessive restraint. Nothing in the

15 In Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941), in which the

Supreme Court affirmed convictions for violating a state statute

prohibiting parades or processions on a public street without a li

cense, the march was in Manchester, a city of 75,000 people (312

U. S. at 573). The night of the parade, in one hour, more than

26,000 people passed one of the intersections where the parade took

place.

In Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951), the Supreme Court

held that a city ordinance which proscribed no appropriate standard

for administrative action and gave administrative officials discre

tionary power to control in advance the right of citizens to speak on

the streets was invalid under the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments. Justice Frankfurter, in a concurring opinion which appears

in Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 272 (1951), said:

We must be mindful ox the enormous difficulties confronting

those charged with the task of enabling the polyglot millions in

the City of New York to live in peace and tolerance. Street

preaching in Columbus Circle is done in a milieu quite different

from preaching on a New England village green . . . I cannot

make too explicit my conviction that the City of New York is

not restrained by anything in the Constitution of the United

States from protecting completely the community’s interests

in relation to its streets . . . (340 IT. S. at 284).

See also Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 554 (1965); Hurwitt v.

City of Oakland, 247 F. Supp. 995, 1001 (N. D. Calif. 1965).

In Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 (1949), the Supreme Court

held that a Trenton, N. J. ordinance that forbad the use or opera-

29

record supports an assertion of regulatory need which goes

so far. “A police measure may be unconstitutional merely

because the remedy, although effective as a means of pro

tection, is unduly harsh and oppressive.” Whitney v. Cali

fornia, 274 IT. S. 357, 377 (1927) (Justice Brandeis and

Holmes, concurring).

[E]ven though the governmental purpose be legitimate

and substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by

tion on public streets of sound trucks or of any instrument which

“emits loud or raucous noises” and is attached to a vehicle on the

public streets did not infringe the right of free speech under the

First Amendment. The opinion by Mr. Justice Reed said:

City streets are recognized as a normal place for the exchange

of ideas by speech or paper. But this does not mean the free

dom is beyond all control. We think it is a permissible exercise

of legislative discretion to bar sound trucks with broadcasts of

public interests, amplified to a loud or raucous volume, from

the public ways of municipalities. On the business streets of

cities like Trenton, with its more than 125,000 people, such dis

tractions would be dangerous to traffic at all hours useful for

the dissemination of information, and in the residential thor

oughfares the quiet and tranquility so desirable for city dwell

ers would likewise be at the mercy of advocates of particular

. . . persuasions (336 U. S. at 87).

And in Farmer v. Moses, 232 F. Supp. 154 (S. D. N. Y. 1964), a

suit to enjoin the New York World’s Fair Corporation from pre

venting plaintiffs from picketing inside the fair grounds, the Dis

trict Court, in denying that part of the requested injunction per

taining to picketing said:

Since the Fair grounds consist of 646 acres of land, the crowd

density on an average day of 200,000 paid admissions is not

inconsiderable, especially when there is factored “in” some

30,000 workers on the scene and when there is factored “out”

a substantial number of acres devoted to parking lots, land

scaping, sculpture and other structures in or on which people

cannot congregate (232 F. Supp. at 158). . . . [Informational

picketing of the type understandably sought here is not clearly

a desirable method for plaintiffs to use when weighed against

such factors as the crowds in attendance, the relatively re

stricted areas and spaces, the convenience and enjoyment of

visitors who pay admission and the like (232 F. Supp. at 161).

3 0

means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liber

ties when the end can be more narrowly achieved. The

breadth of legislative abridgement must be viewed in

the light of less drastic means for achieving the same

basic purpose . . . The unlimited and indiscriminate

sweep of the statute now before us brings it within the

ban of our prior cases. The statute’s comprehensive

interference with associational freedom goes far be

yond what might be justified in the exercise of the

State’s legitimate [purpose] . . . Shelton v. Tucker,

364 U. S. 479, 488, 490 (1960).

See also Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 97 (1940);

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366 U. S. 293,

296-7 (1961); N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 439

(1963); Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492, 497

(M. D. Ala. 1966); cf. Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558, 562

(1948).

This case thus falls within the ban of decisions invalidat

ing under the First and Fourteenth Amendment restric

tions upon speech conduct which are broader than their

justification in protecting other legitimate public concerns.

No one would deny the City of Lexington power to cope

with traffic congestion. But—quite apart from the con

sideration that there is no showing in the Lexington com

prehensive plan or elsewhere in the record of the slightest

relationship between parades and traffic congestion—there

is certainly no basis for the proposition that traffic in

Lexington is always so heavy that all parades must be pro

hibited at all times and in all circumstances in the downtown

area. The Board of Aldermen might be justified in pro

hibiting parades dining peak-load traffic hours (no such

hours were determined by the traffic survey (R. 132)) or in

31

other situations of demonstrated traffic congestion. But

the broad prohibition of every parade in the downtown area

has no relation to the actual needs of the city. Because it

constitutes an overbroad restriction of free speech and

assembly, the ordinance must be invalidated.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should

be reversed, with directions to issue an injunction as

prayed for.

Respectfully submitted,

Carsie A. H all

H enry M. Aronson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on August 5, 1966, I served a copy

of the foregoing Brief for Appellants upon the following

attorneys for appellees, by United States air mail, postage

prepaid:

Hon. Joe T. Patterson

Attorney General of the

State of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi

Hon. William Allain

Assistant Attorney General of the

State of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi

Hon. Pat M. Barrett

Post Office Box 447

Lexington, Mississippi

Attorney for Appellants

38