Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc. Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc. Brief for Appellant, 1948. 46da130b-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2b1d6a41-32d6-4a61-b965-3c9e0dc13a62/whiteside-v-southern-bus-lines-inc-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

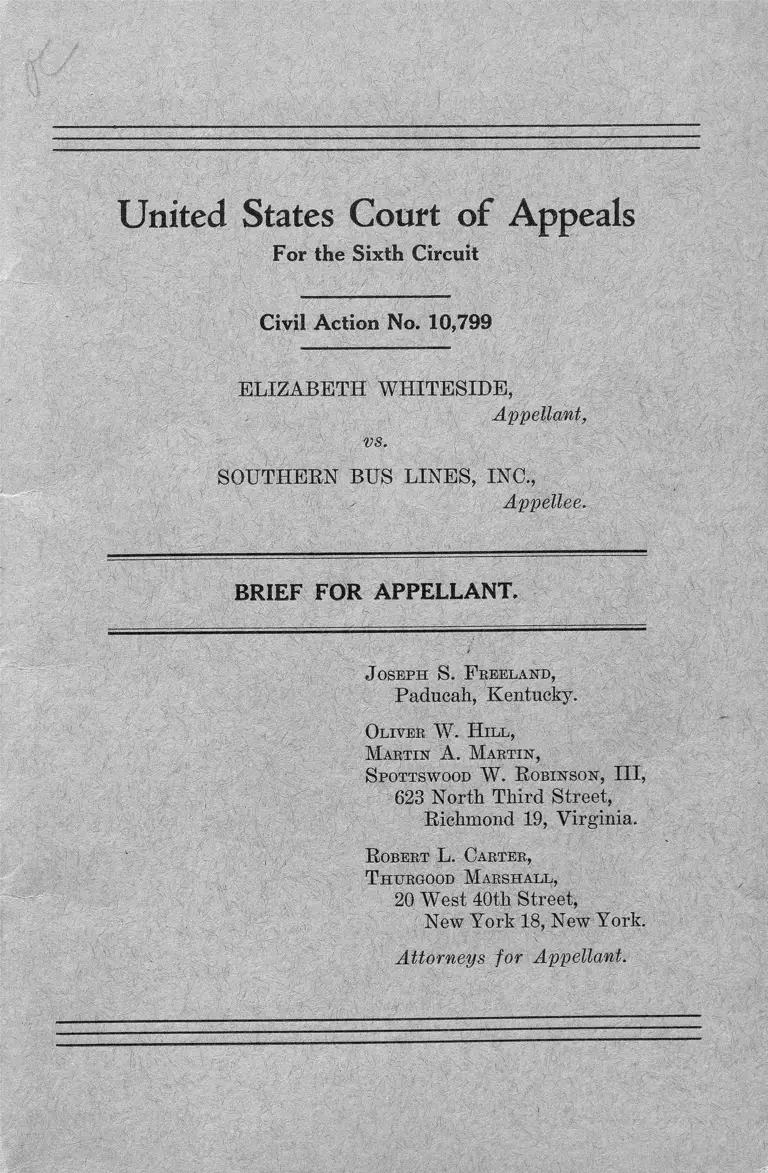

United States Court of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit

Civil Action No. 10,799

ELIZABETH WHITESIDE,

Appellant,

vs.

SOUTHERN BUS LINES, INC.,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT.

J oseph S. F reeland,

Paducah, Kentucky.

Oliver W. H ill,

Martin A. Martin,

S pottswood W. R obinson, III,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York.

Attorneys for Appellant.

Statement of Questions Involved.

1. v Whether the rule or regulations of appellee as ap

plied in this case, can be enforced without violating Article

I, Section 8, of and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments,

to the Federal Constitution, the Public Policy and Laws of

the United States.

The lower court answered—Yes

Appellant contends it should be answered—No

2. Whether the carrier rule or regulation in question,

requiring appellant solely because of her race and color

to remove to the rear of the bus, was a reasonable rule ox-

regulation.

The lower court answered—Yes

Appellant contends it should be answered—No

I N D E X

■ -m

PAGE

Statement of Facts_________________________________ 1

A. Statement of the Case _________________________ 2

B. Errors Relied Upon____________________________ 5

Argument:

I. Whether the rule or regulation of appellee, as

applied in this case, can be enforced without vio

lating Article I, Section 8 of, and the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Federal Consti

tution, the Public Policy and Laws of the United

States____________________ :__________________ 6

II. Whether the carrier rule or regulation, requir

ing appellant, solely because of her race and

color, to remove to the rear of the bus was a

reasonable rule or regulation_________________ 35

Relief _____________________________________________ 51

Table of Cases

Adelle v. Beaugard, 1 Mart. 183_____________________ 46

Alma Motor Co. v. Timkin-Detroit Axle Co., 329 U. S.

129 (1946) ______________________________________ 19

Alston v. School Board (C. C. A., 4th), 112 F. (2d) 992

(1940), 311 U. S. 693, 61 S. Ct. 75, 85 L. Ed. 448

(1940)__________________________________________ 23

Anderson v. Louisville & N. R. Co. (C. C. Ky.), 62 F.

46 (1894) ______________________________________ 37, 38

11

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28, 68

S. Ct. 358,__ L. Ed. _ _ (1948)________ 22, 25, 31, 33, 35

Bowman y. Chicago & N. W. R. Co., 125 U. S. 465, 8

S. Ct. 689, 31 L. Ed. 700 (1888) __________ ______- - 41

Britton v. Atlantic & C. A. L. Ry. Co., 88 N. C. 536

(1883)__________________________________________ 50

Brown v. Memphis & C. R. Co. (C. C. Tenn.), 5 F. 499

(1880) ______________________ 38

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16, 62 L.

Ed. 149 (1917) _________________________________22,50

Caminetti v. United States, 242 U. S. 470, 37 S. Ct. 192,

61 L. Ed. 442 (1917) _____________________________ 36

Carrey v. Spencer (N. T. Sup. Ct.), 36 N. Y. S. 886

(1895) ________________-________________-________37,38

Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 338,

21 S. Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900)__________ - — 26

Chicago R. I. & P. Ry. Co. v. Allison, 120 Ark. 54, 178

S. W. 401 (1915) ________________________________ 47

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. R. Co., 218 U. S. 71, 30 S. Ct.

667, 54 L. Ed. 936 (1910) __________ -______ 26, 28, 33, 34

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, 50 S. Ct. 407,

74 L. Ed. 1128 (1930) ___________________-----— 22

Covington & C. Bridge Co. v. Kentucky, 154 U. S. 207,

14 S. Ct. 1087, 38 L. Ed. 962 (1894) ______________ 37

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 62 S. Ct. 164, 86

L. Ed. 119 (1941) _____________________________ 24, 36

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283, 65 S. Ct. 208, 89 L. Ed.

243 (1944) ____________________________ _________ 24

Gentry v. McMinnis, 33 Ky. 382 ------------- -------------------- 46

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 6 L. Ed. 23 (1824) ------- 41

Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Pennsylvania, 114 U. S. 196,

5 S. Ct. 826, 29 L. Ed. 158 (1885) ____________ -___ 36

Griffin v. Griffin, 327 U. S. 220, 66 S. Ct. 556, 90 L. Ed.

635 (1946) ____________________ ______________ _

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct. 926,

59 L. Ed. 1340, L. R. A. 1916A, 1124 (1915) _______

PAGE

18

I l l

Hall V. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed, 547 (1877)____27, 34

Hare v. Board of Education, 113 N. 0. 10, 18 S. E. 55 46

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 H. S. 668, 47 S. Ct. 411, 71 L. Ed.

831 (1927) ______________________________________ 22

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60A, 457 (1905) ________37,38

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 63 S. Ct.

1375, 87 L. Ed. 1774 (1943) ______________________ 24

Hoke v. United States, 227 U. S. 308, 33 S. Ct. 281, 57

L. Ed. 523 (1913) _______________________________ 36

Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U. S. 409, 17 S. Ct. 841, 42 L. Ed.

215 (1897) ________________._____________________ 18

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 68 S. Ct. 847, 92 L. Ed.

— (1948) -------------------------------------------------------- 8,10

Kelly v. Washington, 302 U. S. 1, 58 S. Ct. 87, 82 L.

Ed. 3 (1937) _______________________________ _____ 41

Kerr v. EnoucK Pratt Free Library (C. C. A., 4th),

149 F. (2d) 212 (1945), cert. den. 326 U. S. 721, 66

S. Ct. 26, 90 L. Ed. 427 (1945) ___________________ 23

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 65 S. Ct.

193, 89 L. Ed. 194 (1944) ________________________ 24

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L. Ed.

1281 (1939) _ ___________________________________ 23

Lee v. New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182___ 46

Leisy v. Hardin, 135 U. S. 100, 10 S. Ct. 681, 34 L. Ed.

128 (1890) ______________________________________ 41

Louisville & N. R. R. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701, 147 S. W.

411 (1912) _______________________ ______ ________ 47

McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151,

35 S. Ct. 69, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914) ____________ 22, 37, 38

McLemore v. Commonwealth, Supreme Court of Ap

peals of Virginia, No. 2981, April, 1945 __________ 9

Matthews v. Southern Ry. System, 157 Fed. (2d) 609

(1946) ----------------------------------------------------------- ----6, 36

Minnesota Rate Cases, 230 U. S. 352, 33 S. Ct. 729, 57

L. Ed. 1511 (1913) ___________________________ 41

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 59 S.

Ct. 232, 83 L. Ed. 208 (1938)____________ _________ 22

Missouri K. & T. Ry. Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25 Tex. Civ.

App. 500, 61 S. W. 327 (1901)____________________ 47

PAGE

IV

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80, 61 S. Ct. 873,

85 L. Ed. 1201 (1941) ________________ _________ 22, 36

Moreau v. Grandieh, 114 Miss. 560, 76 S. 434 __— ------ 45

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 66 S. Ct. 1050, 90 L.

Ed. 1317, 165 A. L. R. 574 (1946) ---------8,10,11, 22, 33,

35, 37, 39, 40, 41

Mullins v. Belcher, 142 Ky. 673, 143 S. W. 1151 --------- 46

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 26 L. Ed. 567 (1881) — 23

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U. S.

552, 58 S. Ct. 703, 82 L. Ed. 1012 (1938) --------------- 33

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73, 52 S. Ct. 484, 76 L. Ed.

984, 88 A. L. R. 458 (1932) ____________________ — 23

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 576, 47 S. Ct. 446, 71 L. Ed.

759 (1927) ______________________________________ 23

Norfolk & W. Ry. Co. v. Brame, 109 Va. 422, 63 S. E.

1018 (1909) ___________________________ 36

Norfolk & W. Ry. Co. v. Wysor, 82 Va. 250 (1886)------ 36

Ohio Valley R y ’s. Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431, 47

S. W. 344 (1898) ________________________________ 26

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633, 68 S. Ct. 269, —_

L. Ed____ (1948) ________________________ _____— 22

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41

L. Ed. 256 (1896) _________________ 26,27,28,33,34,49

Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88, 65 S. Ct.

1483 (1945) ----------------- 33

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549 (1947) 19

Rice v. Elmore (C. C. A., 4th), 165 P. (2d) 387 (1948),

cert. den. 333 U. S. 875, 68 S. Ct. 905, — L. Ed------

(1948)__________________________________________ 23

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849) 33

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91, 65 S. Ct. 1031,

89 L. Ed. 1495 (1945) ___________ _____:-------— 10

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. Ed.

___ (1948) _________________________ 8,13,19, 20, 25, 34

Stipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 68 S. Ct.

299, 92 L. Ed. 256 (1948) ----------------------------------- 22

PAGE

V

Smith v. Allwright, 319 U. S. 738, 64 S. Ct. 757, 88 L.

Ed. 987 (1944) __________________________________ 23

South Florida E. Co. v. Rhoads, 25 Fla. 40, 5 So. 623,

3 L. E. A. 733, 737 (1889)________________________ 25

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761, 65 S. Ct.

1515, 89 L. Ed. 1915 (1945)_____________________ 41

State v. Galveston H. & S. A. Ey. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.),

184 S..W. 227 (1916)___________________________ 38

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92A, 773 (1914)_______37, 38

State v. Treadaway, 126 La. 300, 52 S. 500-___________ 46

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 S. 75

(1892)-------------------------------------------------------------------26, 38

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, 65 S. Ct.

226, 89 L. Ed. 173 (1944)__________________________ 24, 33

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 307, 25 L. Ed.

664 (1880) _____________________________________ 21, 23

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 IT. S. 410,

68 S. Ct. 1138, 92 L. Ed..... (1948)_________________ 23

Theophanis v. Theophanis, 244 Ky. 689, 57 S. W. (2d)

957--------------------------------------------------------------------- 46

Thompkins v. Missouri K. & T. Ey. Co. (C. C. A. 8th),

211 F. 391 (1914)________________________________ 38

Tucker v. Blease, 97 S. C. 303, 81 S. E. 668____________ 45

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and

Engineers, 323 U. S. 210, 65 S. Ct. 235, 89 L. Ed.

187 (1940) _________________________________1___ 24

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 IT. S. 78, 29 S. Ct. 14, 53 L.

Ed. 97 (1908) ___________________________________ 14

United States v. Hill, 248 U. S. 420, 39 S. Ct. 143, 63

L. Ed. 337 (1919)___________________________ • 36

Virginia & S. W. Ey. Co. v. Hill, 105 Va. 738, 54 S. E.

872 (1906) _____________________________________ 36

Virginia Ry. & P. Co. v. O ’Flaherty, 118 Va. 749, 88 S.

E. 312 (1916) ___________________________________ 36

Washington B. & A. Elect. Ey. Co. v. Waller, 53 App.

D. C. 200, 289 F. 598, 30 A. L. B. 50 (1923)______37, 38, 50

Welton v. Missouri, 91 U. S. 275, 23 L. Ed. 347 (1876).... 41

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064, 30

L. Ed. 220 (1886)_______________________________ 23

PAGE

Table of Statutes

PAGE

Alabama—

Code, 1923, Sec, 5001— __________________________ 45

Statutes, 1940—

Title 1, See. 2 ______________________________ 43

Title 14, Sec. 360 ______________________ _____ 43

Arkansas—

Statutes 1937 (Pope)—

Sec. 1200 ___________________________________ 43, 44

Sec. 3290 ___________________________________ 43, 44

Florida—

Constitution, Article XVI, Sec. 24----------------------- 44, 45

Statutes, 1941, Sec. 1.01--------------------- ---------------44,45

Georgia—

Code. Michie (1926), Sec. 2177___________________ 46

Michie Supp. (1928), Sec. 2177------------------- 43

Laws, 1927, p. 272________________________________ 43

Indiana—

Statutes (Burns), 1933, Secs. 44-104----------------------- 44

Louisiana—

Acts—

1908, No. 8 7 _________________________________ 46

1910, No. 206 ________________________________ 46

Criminal Code (Dart) 1932, Articles 1128-1130...-.... 46

Maryland—

Code (Flack) 1939, Article 27, Sec. 445___________ 44

Mississippi—

Code, 1942, Sec. 459---- ---------------------------- ------------- 44

Constitution, See. 263 ------------------- 44

v i

Missouri—

Revised Statutes 1939, See. 4651_________________ 44

North Carolina—

Constitution, Article XIV, Sec. 8____________ _____ 44

General Statutes, 1943-

Sec. 14-181 __________________:_______________ 44

Sec. 51-3 ______________________i._______ 44

Sec. 115-2 ______________________ 43

Sec. 115-20 ________ 46

Public Laws, 1903, Ch. 435, See. 22________________ 46

North Dakota—

Revised Code, 1943, Sees. 14-0304 and 14-0305______ 44

Oklahoma—

Constitution—

Article XIII, Sec. 3 ______ 44

Article XXIII, Sec. 11 ,,_____ _________________ 44

Statutes, 1931—

Sec. 13-183 ________________________ 44

Sec. 43-12 ___________ ...______________ . 44

. Sec. 70-452 __________ 44

Oregon—

Compiled Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-1010.________________ 44

South Carolina—

Constitution, Article III, Sec. 33____ 44

Tennessee—

Code (Michie) 1938—

Sec. 8396 ____________________________________ 43

Sec. 8409 _______________ 44

Constitution, Article XI, Sec. 14_________________ 44

V l l

PAGE

T exa s-

Penal Code (Vernon) 1935, Sec. 493----------------------- 44

Revised Civil Statutes (Vernon) 1936-

Article 2900 ------ ------------------------------------------- 44

Article 4607 -------------------------------------------------- 44

Article 6417 -------------------------------- 44

Virginia—

Code (Miehie) 1942-

Section 67 ----------------------------------------------------- 43

Section 3881 -------------------------------------------------- 25

Sections 4G97z to 4097dd, inclusive-------------------- 37

Section 4097d d ----------------------------------------------- 8

Constitution, Sec. 153------------------------------------------ 25

Miscellaneous Authorities

American Jurisprudence, ‘ ‘ Carriers, ” Vol. 10, Sec. 1026 35

Congressional Globe Congress, 1st Session----------------- 21

Executive Order No. 9981, July 26, 1948 ------------------- 48

F lack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1909)_________________________________ ________21, 22

J ohnson, Charles S., Patterns of Segregation (New

York, 1943) --------- 48

Myrdal, Gtunnar, An American Dilemma (New York,

1944)___________________________________________ 48

Report of The President’s Committee on Civil

Rights_____ ..._______________________________ 28, 29,30

United Nations Charter ------------------------------------------ 30

V l l l

PAGE

United States Court of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit

E lizabeth W hiteside,

Appellant,

vs.

S outhern B us L ines, I nc.,

Appellee.

Civil A ction

No. 10,799

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT.

Statement of Facts.

This cause was tried in the District Court of the United

States for the Western District of Kentucky before the

court, without a jury, on May 14, 1947. Findings of fact

and conclusions of law were made, and final judgment on

behalf of the appellee (defendant below) was entered on

June 15, 1948 (E. 202). Appellant (plaintiff below) moved

the Court to set aside its decision and judgment upon speci

fied grounds (R. 204), which motion was overruled on June

28, 1949 (R. 205). Notice of appeal was filed on July 26,

1948 (R. 205).

A. Statement of the Case.

1 .

On July 27, 1946, appellant filed her complaint alleging

that she was a colored citizen of the United States and of

the State of Kentucky; and that appellee was a common

carrier engaged in the transportation of passengers by

motor bus in interstate commerce from St. Louis, Missouri,

to Paducah, Kentucky, via Cairo, Illinois, and between

various other states of the United States. She further al

leged that on May 6, 1946, she purchased a ticket from an

agent of defendant in St. Louis, Missouri, for transporta

tion over defendant’s lines to Paducah, Kentucky, via

Cairo, Illinois; that she rode busses operated by defendant

and connecting carriers until she arrived at Wickliffe, Ken

tucky, at which time and place she was unlawfully requested

to move from the seat in which she was sitting, to another

seat in the rear of said bus because of her race and color

and because she was a Negro. Upon her refusal to move,

the bus operator, an agent of the defendant, procured as

sistance of a police officer in Wickliffe, Kentucky, and to

gether they forcibly, unlawfully, maliciously, and wilfully

ejected her, without any legal process whatever. She there

upon lost numerous articles of personal property and sus

tained various injuries, whereupon she sued appellee for

the sum of Fifty Thousand and One Hundred Dollars

($50,100.00) (R. 1-6). An amended complaint was filed

April 21, 1947 (R. 18).

On September 13, 1946, appellee filed its answer, admit

ting that it is a common carrier engaged in the transporta

tion of persons traveling in interstate commerce, and that

3'

appellant had a ticket entitling her to transportation on its

bus from Cairo, Illinois, to Paducah, Kentucky; and that it

did not know whether plaintiff’s ticket entitled her to trans

portation from St. Louis, Missouri, to Cairo, Illinois; that

it did not know whether plaintiff was a Negro or colored

person. Defendant admitted that its agent procured the

services of a police officer in Wickliffe, Kentucky, and

forcibly ejected plaintiff from the bus, although it alleged

that it only used such force as was necessary to accomplish

the said ejection. It admitted that plaintiff was ejected

solely because of her race and color and because she was a

Negro. It further alleged that under its rules and regula

tions, which had been filed with the Interstate Commerce

Commission and with the Kentucky Division of Motor

Transportation, plaintiff was seated in a portion of the bus

set aside for the exclusive use and occupancy of white per

sons and that her refusal to move from that seat was the

sole cause of her ejection (R. 9-15).

Interrogatories were submitted to defendant under

Rule 33 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (R. 16),

and defendant’s answer thereto gave the name and address

of the operator of defendant’s bus and the name, residence

and official capacity of the police officer mentioned in de

fendant’s answer and stated that the defendant’s rules

and regulation tariff requiring segregation of the races on

its common carriers had been filed with the two above

named governmental agencies on November 15, 1938, and

that such custom, usage, and practice of segregation of the

races had been in force and effect for many years (R. 17).

Trial was had on May 14, 1947, and final judgment en

tered on behalf of appellee on June 15, 1948.

4

2.

Mary Elizabeth Whiteside (plaintiff below), and appel

lant herein, is a Negro citizen of the United States and of

the State of Kentucky, temporarily working in Chicago,

Illinois. On May 5, 1946, she purchased a ticket in St,

Louis, Missouri, entitling her to transportation on the bus

lines of appellee, defendant below, and connecting carriers,

from St. Louis, Missouri, to Paducah, Kentucky, via Cairo,

Illinois, and Wickliffe, Kentucky. On the same day she

boarded a bus in St. Louis, Missouri, to Chicago, Illinois.

She changed busses in Cairo, Illinois, and boarded the bus

operated by defendant for Paducah, through Wickliffe,

Kentucky. She sat in the third seat from the front, directly

behind the driver (R. 114). On this bus there are six double

seats on each side of the aisle and one long seat in the rear

which accommodates five persons (R. 112, 113), and at the

time appellant boarded the bus there were approximately

seventeen (17) or nineteen (19) other passengers thereon

(R. 111). The bus has a seating capacity of twenty-nine

(29) (R. 112).

At Wickliffe, Kentucky, the operator requested appellee

to move to the rear (R. 117-118). She refused, and he

called the Town Marshall of Wickliffe, Kentucky, to assist

him in removing her from the bus (R. 119). Together they

caught her by her arms and ejected her from the bus (R.

120). At this time there were vacant seats in the rear of

the bus and one white person was seated in a seat to the

rear of appellant but on the opposite side of the bus.

The operator of the bus refused to refund appellant her

fare in cash, but did give her a transfer ticket entitling her

to transportation on another bus to her destination (R.

5

123). He refused to permit her to reboard Ms bus. Appel

lant secured other transporation on another bus line to her

destination and immediately complained to her relatives

and physician of various injuries sustained by reason of

her ejection. She was under the care of a physician for

some time. He testified that in his opinion the injuries

were sustained by reason of her forcible ejection from the

bus (R. 57-67).

Appellee based its sole defense upon its claimed rule or

regulation requiring segregation of the races.

B. Errors Relied Upon.

1. The Court erred in finding that the segregation rule

or regulation of appellees was reasonable and necessary

for the safety, comfort, and convenience of the passengers

using appellee’s busses, including the bus in which the ap

pellant was riding.

2. The Court erred in concluding that appellee had a

legal and constitutional right and duty to adopt its segre

gation rule and regulation and the right and duty to seat all

passengers on its busses, including appellant, purely and

simply in accordance with their race or color pursuant

to such rule and regulation.

3. The Court erred in concluding as a matter of law

that appellee had the right and duty to evict appellant from

the bus when she failed to abide by said segregation rule

and regulation.

4. The Court erred in entering judgment for the appel

lee and against appellant.

6

A R G U M E N T .

L

Whether the Rule or Regulation of Appellee, as Ap

plied in This Case, Can Re Enforced Without Violating

Article I, Section 8 of, and the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution, the Public

Policy and Laws of the United States.

The lower court answered— Fes

Appellant contends it should be answered— No

Appellant was ejected from the bus in question and

deprived of her rights as an interstate passenger by gov

ernmental acts through officers of the state of Kentucky, by

a rule or regulation sanctioned by the Interstate Commerce

Commission and by the decision and ruling of the court

below.

The carrier did not urge in the Trial Court the validity

of any segregation statute; nor did it claim that the operator

acted without the scope of this authority. This case is gov

erned by the rules of law applicable to the obligations of a

common carrier to its passengers and its liabilities for

breach of those obligations.

As was stated in Matthews v. Southern Ry. System., 157

Fed. (2d) 609, 610, “ A common carrier is required to pro

tect its passengers against assault or interference with the

peaceful completion of their journey. But an exception to

the general rule is that an agent of the carrier is not re

quired to interfere with the known officer of the law while

engaged in the performance of his duty. # * but the ex

ception goes no further. It does not cover the action of the

agent in otherwise causing, procuring, assisting in, or par

7

ticipating in the arrest or ejection, or when the arrest is at

the instance of the agent.” The Court further stated in

that case that it saw no valid distinction between segrega

tion in buses and railroad cars.

In the instant case, the ejection of appellant was ac

complished by local law enforcement officers summoned by

appellee. And, in this action, wherein appellant seeks re

dress for violation of her rights, the court below enforced

the regulation in question against her, and attached to it a

validity which effectively deprives appellant of her right

to recover.

When as in the instant case, an interstate passenger

declines to change her seat pursuant to a carrier segrega

tion rule or regulation, and the carrier summons local law

enforcement officers, who acting under its command and di

rection, eject the recalcitrant passenger from the bus, it is

clear that this is state and not private action and that it

is the state which is depriving the Negro passenger of con

stitutional and statutory rights.

Similarly, when, as here, a federal court gives validity

to a regulation which compels a Negro passenger to change

his seat because of race or color, and thereby deprives the

Negro passenger of rights to redress, it is the action of the

sovereign, and not the action of individuals, which accom

plishes the deprivation. It has all too frequently been as

sumed that this deprivation results from individual action

consisting in the mere promulgation of the regulation.

Such an assumption rests on the fallacy that common car

riers can grant, modify or destroy rights of passengers

without the aid of the sovereign.

It is apparent that the creation, modification and destruc

tion of rights is controlled by the legal consequences which

the sovereign attaches to the individual action. When it

8

is necessary to appeal to state law enforcement officers, or

to the courts, for enforcement of a regulation, individual

action ceases and governmental action commences. It may

well be that where a Negro passenger occupies a seat in the

“ White” section, she has been deprived of no rights by

the mere promulgation of the regulation. But when en

forcement is obtained through the process of governmental

action, by either police officers or the courts, as a conse

quence of which he or she is ejected from his or her seat or

is denied recovery therefor, government itself has effected

a deprivation,1 in violation of the United States Consti

tution.

A.

Enforcement of the Regulation Imposes An Undue

Burden on Interstate Commerce, in Violation of

Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution of the

United States.

The analogy of the instant case to the Morgan case is

complete. The Statute 2 there involved provided:

“ All persons who fail while on any motor vehicle

carrier, to take and occupy the seat or seats or other

space assigned to them by the driver, operator or

other person in charge of such vehicle, or by the

person whose duty it is to take up tickets or collect

fares from passengers therein, or who fail to obey

1 A perfect analogy is supplied by Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S.

1, 68 S. Ct. 836 (1948) and Hurd v, Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 68 S. Ct.

847 (1948). In each case, Negroes were enjoined from the occu

pancy of properties because of the existence thereupon of racial re

strictive covenants. It was held that while the individual action

consisting in the making and imposition of the restrictive covenants

was not proscribed by the Federal Constitution or laws, the enforce

ment of such covenants by the courts, state or federal, was prohibited.

In each case, government, through the courts, was the effective agent

in depriving the purchasers of their properties and of the exercise of

their constitutionally protected rights therein.

2 Code of Virginia, 1942, Sec. 4097 dd.

9

the directions of any such driver, operator or other

person in charge, as aforesaid, to change their seats

from time to time as occasions require, pursuant to

any lawful rule, regulation or custom in force by such

lines as to assigning separate seats or other space to

white and colored persons, respectively, having been

first advised of the fact of such regulation and re

quested to conform thereto, shall be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall

be fined not less than five dollars nor more than

twenty-five dollars for each offense. Furthermore,

such persons may be ejected from such vehicle by any

driver, operator or person in charge of said vehicle,

or any police officer or other conservator of the

peace; and in case such persons ejected shall have

paid their fares upon said vehicle, they shall not be

entitled to the return of any part of same. For the

refusal of any such passenger to abide by the re

quest of the person in charge of said vehicle as afore

said, and his consequent ejection from said vehicle,

neither the driver, operator, person in charge, owner,

manager nor bus company operating said vehicle

shall be liable for damages in any Court.” (Italics

supplied.)

Under this statute, the starting point was a segregation

regulation of the carrier. If the carrier had no such regu

lation, the statute did not apply.3 But if there was “ any

lawful rule, regulation or custom in force by such lines as

to assigning separate seats or other space to white or colored

persons, respectively,” and the passenger failed to take the

seat assigned or to change seats pursuant to said regula

tion, “ having first been advised of the fact of such regula

tion and requested to conform thereto,” :

(1) The passenger “ shall be deemed guilty of a mis

demeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be fined not less

3 McLemore v. Commonwealth, Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia, No. 2981, April, 1945 (Error confessed, no opinion).

10

than five dollars nor more than twenty-five dollars for each

offense;”

(2) Such passenger “ may be ejected from such vehicle

by any driver, operator or person in charge of said vehicle,

or by any police officer or other conservator of the peace;”

(3) “ For the refusal of any such passenger to abide

by the request of the person in charge of said vehicle as

aforesaid, and his consequent ejection from said vehicle,

neither the driver, operator, person in charge, owner, man

ager nor bus company operating said vehicle shall be lia

ble for damages in any court;”

If the statute could validly have been applied against

the passenger involved in that case, these consequences

would have followed because such was the command of the

legislature.

Under the principles laid down in the instant case the

same consequences, except conviction of crime, are to fol

low under similar conditions. The court below held in sub

stance that if appellee bus company had a rule or regula

tion requiring the segregation of the races, which was

known to or brought to the attention of appellant, and ap

pellant failed to change seats in accordance therewith, ap

pellant might be ejected from the bus by either the opera

tor or by police officers called for the purpose and that,

under such circumstances, neither appellee nor the police

officer would be liable in damages to appellant for the ejec

tion. These consequences would follow from governmental

action4 differing in form but not in substance or effective

ness from that sought to be supplied by the legislature in

the Morgan case.

4 Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91, 65 S. Ct. 1031, 89 L. Ed.

1495 (1945), and the action of this Court in sustaining the regulation

as a defense to this action is action of the Federal government.

11

So, notwithstanding that the identical consequences were

condemned in the Morgan case as unlawful burdens on in

terstate commerce, and unlawful interferences with the con

stitutional rights of the interstate passenger involved, this

court, by the process of a different rationalization, now

permits the same consequences to be wrought against an

interstate passenger.

The important consideration is not merely the existence

of the segregation regulation. The carrier involved in the

Morgan case had one of these regulations. The important

consideration is the fact that the power of government is

in the instant case thrown behind the regulation to enforce

compliance with the policy which lead to its promulgation.

Appellant therefore submits that enforcement of the

regulation, in the manner and form aforesaid, imposes an

undue burden on interstate commerce in violation of Article

I, Section 8, of the Constitution of the United States.

B.

Enforcement of the Carrier Rule or Regulation Is

Governmental Action Within the Prohibitions of

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution.

This case falls squarely within the decision of the Su

preme Court in the case of Hurd v. Hodge, supra, in which

it was held that a discriminatory regulation or covenant

adopted by private persons could not be enforced by an

agency of the federal government. In this case the action

of the Interstate Commerce Commission is apparent. Sec

tion 316(a) of Title 49 of the United States Code requires

“ Every common carrier of passengers by motor vehicle to

establish reasonable * * * equipment and facilities for the

transportation of passengers in interstate or foreign com

merce ; to establish, observe, and enforce just or reasonable

12

# * # regulations and practices relating thereto * * *

Section 317 of Title 49 of the United States Code requires

every common carrier by motor vehicle to “ File with the

Commission * * * tariffs showing all the rates, etc., and all

services in connection therewith, of passengers or property

in interstate or foreign commerce * * *; and the commission

is authorized to reject any tariff filed with it which is not

inconsonant with this section and with such regulations.

Any tariffs so rejected by the commission shall be void

and its use shall be unlawful” . Section 318 of Title 49

provides for a hearing when any change is desired in said

rule or regulation. Section 316(g) provides that whenever

any such tariff is filed with the commission, the commission

may, on its own initiative or on complaint of any interested

party, require a hearing to determine the reasonableness,

usefulness, and legality of such rule or regulation prior to

the time it goes into effect, and may suspend the enforce

ment thereof until such hearing is completed. The an

nounced intentions of these sections is to determine and

require that no undue prejudice is imposed upon any per

son coming under the act. Section 316(j) of the same Title

further provides that nothing contained in this act “ shall

be held to extinguish any remedy or right of action not in

consistent herewith” . Thus the regulations here in ques

tion had to have the approbation of the Interstate Com

merce Commission, either silent or active, before they could

become effective. Appellant contends that the approval

of a rule or regulation using raee or color as a criterion by

an agency of the federal government violates the Fifth

Amendment. Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81

(1943).

The ejection of appellant from the bus by a local police

officer was, of course, state action. In ejecting appellant

the state adopted and enforced a racially discriminatory

regulation and thereby denied to appellant rights secured

13

under the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus this case falls

squarely within the prohibition of Shelley v, Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1 (1948).

It is clear that such rights as are protected by consti

tutional and statutory guaranties against impairment by

the legislative and executive branches of government are

equally protected against impairment by the judiciary. The

prohibitions of both the Fourteenth and Fifth Amendments,

and of Sections 41 and 43 of Title 8 of the United States

Code, apply to all conceivable forms of governmental action,

including that of the judiciary.5

Thus, the action of government is seen to exist when a

court bases a judgment upon a rule of substantive law

which it, or some other court, “ finds” in the common law,

or judge-made law, of state or nation. Since the rule so

made and applied is produced by governmental action, it

is subject to the same test of validity as it would be if made

by that other form of governmental action consisting in

enactment by the legislature.

That the action of state courts in enforcing a substantive

common law rule formulated by those courts result in the

denial of rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

was recently reaffirmed in Shelley v. Kraemer,e where the

United States Supreme Court, in holding that enforcement

by a state court of a restrictive covenant prohibiting owner

ship or occupancy of real property by Negroes to be in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment, discussed the matter,

as follows :6 7

“ That the action of state courts and of judicial

officers in their official capacities is to be regarded

6 As hereinbefore pointed out, a denial of rights secured by Sec

tion 3 of Title 49 of the United States Code is actionable, whether or

not accomplished under color of state law.

6 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, L. Ed. (1948).

7 334 U. S. at 14-18. Footnotes 13 to 21, inclusive, are the Courts.

14

as action of the State within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment, is a proposition which has

long been established by decisions of this Court. That

principle was given expression in the earliest cases

involving the construction of the terms of the Four

teenth Amendment. Thus, in Virginia v. Rives, 100

U. S. 313, 318 (1880), this Court stated: ‘ It is doubt

less true that a state may act through different

agencies,—either by its legislative, its executive, or

its judicial authorities; and the prohibitions of the

amendment extend to all action of the State denying

equal protection of the laws, whether it be action by

one of these agencies or by another. ’ In Ex parte

Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 347 (1880), the Court ob

served: ‘A State acts by its legislative, its execu

tive, or its judicial authorities. It can act in no

other way.’ In the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3,

11, 17 (1883), this Court pointed out the Amendment

makes void ‘ State action of every kind’ which is in

consistent with the guaranties therein contained, and

extends to manifestations of ‘ State Authority in the

shape of laws, customs, or judicial or executive pro

ceedings.’ Language to like effect is employed no

less than eighteen times during the course of that

opinion.13

“ Similar expressions, giving specific recognition

to the fact that judicial action is to be regarded as

action of the State for the purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment, are to be found in numerous cases which

have been more recently decided. In Twining v.

New Jersey, 211 U. S. 78, 90-91 (1908), the Court

said: ‘ The judicial act of the highest court of the

13 Among the phrases appearing in the opinion are the following:

“ the operation of State laws, and the action of State officers execu

tive or judicial” ; “ State laws and State proceedings” ; “ State law * * *

or some State action through its officers or agents” ; “ State laws and

acts done under State authority” ; “ State laws, or State action of some

kind” ; “ Such laws as the States may adopt or enforce” ; “ such acts

and proceedings as the States may commit or take” ; “ State legisla

tion or action” ; “ State law or State authority.”

15

State, in authoritatively construing and enforcing its

laws, is the act of the State.’ In BrinJcerhoff-Faris

Trust d Savings Co. v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673, 680 (1930),

the Court, through Mr. Justice Brandeis, stated:

‘ The federal guaranty of due process extends to state

action through its judicial as well as through its

legislative, executive or administrative branch of

government.’ Further examples of such declara

tions in the opinions of this Court are not lacking.14

“ One of the earliest applications of the prohibi

tions contained in the Fourteenth Amendment to ac

tion of state judicial officials occurred in cases in

which Negroes had been excluded from jury service

in criminal prosecutions by reason of their race or

color. These cases demonstrate, also, the early recog

nition by this Court that state action in violation of

the Amendment’s provisions is equally repugnant to

the constitutional commands whether directed by

state statute or taken by a judicial official in the ab

sence of statute. Thus, in Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U. S. 303 (1880), this Court declared invalid a

state statute restricting jury service to white persons

as amounting to a denial of the equal protection of

the laws to the colored defendant in that case. In

the same volume of the reports, the Court in Ex

parte Virginia, supra, held that a similar discrimina

tion imposed by the action of a state judge denied

rights protected by the Amendment, despite the fact

that the language of the state statute relating to

jury service contained no sueh restrictions.

14 Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 397 (1881 ); Scott v. McNeal,

154 U. S. 34, 45 (1894) ; Chicago, Burlington and Quincy R. Co. v.

Chicago, 166 U. S. 226, 233-235 (18 97 ); Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U. S.

409, 417-418 (1897 ); Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442, 447 (1900 );

Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316, 319 (1906 ); Raymond v. Chicago,

Union Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20, 35-36 (1907 ); Home Telephone

and Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278, 286-287 (1913 );

Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530, 548 (1922 );

American Railway Express Co. v. Kentucky, 273 U. S. 269, 274

(1927 ); Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103, 112-113 (1935 ); Hans-

berry v. Lee, 311 U. S. 32, 41 (1940).

16

“ The action of state courts in imposing penalties

or depriving parties of other substantive rights with

out providing adequate notice and opportunity to

defend, had, of course, long been regarded as a denial

of the due process of law guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment. Brinkerhoff-Faris Trust & Sav

ings Go. v. Hill, supra, Cf. Pennoyer Neff, 95 U. S.

714 (1 8 7 8 ).15

“ In numerous cases, this Court has reversed

criminal convictions in state courts for failure of

those to provide the essential ingredients of a fair

hearing. Thus it has been held that convictions ob

tained in state courts under the domination of a mob

are void. Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86 (1923).

And see Frank v. Mangum, 237 U. S. 309 (1915).

Convictions obtained by coerced confessions,16 by

the use of perjured testimony known by the prosecu

tion to be such,17 or without the effective assistance

of counsel,18 have also been held to be exertions of

state authority in conflict with the fundamental rights

protected.

“ But the examples of state judicial action which

have been held by this Court to violate the Amend

ment’s commands are not restricted to situations in

which the judicial proceedings were found in some

manner to be procedurally unfair. It has been recog

nized that the action of state courts in enforcing a

substantive common-law rule formulated by those

courts, may result in the denial of rights guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment, even though the

15 And see Standard Oil Co. v. Missouri, 224 U. S. 270, 281-282

(19 12 ); Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U. S. 32 (1940).

18 Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 (1936 ); Chambers v.

Florida, 309 U. S. 227 (1940 ); Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S.

143 (1944 ); Lee v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 742 (1948).

17 See Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103 (1935) ; Pyle v. Kan

sas, 317 U. S. 213 (1942).

18 Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (19 32 ); Williams v. Kaiser,

323 U. S. 471 (1945) ; Tomkins v. Missouri, 323 U. S. 485 (1945 );

DeMeerleer v. Michigan, 329 U. S. 663 (1947).

17

judicial proceedings in such cases may have been

complete accord with the most rigorous conceptions

of procedural due process.19 Thus, in American Fed

eration of Labor v. String, 312 U. S. 321 (1941), en

forcement by state courts of the common-law policy

of the State, which resulted in the restraining of

peaceful picketing, was held to be state action of the

sort prohibited by the Amendment’s guaranties of

freedom of discussion.20 In Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296 (1940), a conviction in a state court

of the common-law crime of breach of the peace was,

under the circumstances of the case, found to be a

violation of the Amendment’s commands relating to

freedom of religion. In Bridges v. California, 314

U. S. 252 (1941), enforcement of the state’s common-

law rule relating to contempts by publication was

held to be state action inconsistent with the prohibi

tions of the Fourteenth Amendment.21 And cf.

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy R. Co. v. Chicago,

166 U. S. 226 (1897).

“ The short of the matter is that from the time of

the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment until

the present, it has been the consistent ruling of this

Court that the action of the States to which the

Amendment has reference, includes action of state

courts and state judicial officials. Although, in con

struing the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment, dif

ferences have from time to time been expressed as

to whether particular types of state action may be

said to offend the Amendment’s prohibitory provi

sions, it has never been suggested that state court

action is immunized from the operation of those pro

19 In applying the rule of Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64

(1938), it is clear that the common-law rules enunciated by state

courts in judicial opinions are to be regarded as a part of the law of

the State.

20 And see Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769 (19 42 );

Cafeteria Employees Union v. Angelos, 320 U. S. 293 (1943).

21 And see Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331 (1946 ): Craiq

v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 (1947).

18

visions simply because the act is that of the judicial

branch of the state government.”

It is also perfectly clear that enforcement by a federal

court of a substantive common-law rule made either by itself,

another federal court, or by a state court, is equally viola

tive of constitutional and statutory guaranties. The Fifth

Amendment, like the Fourteenth, extends its prohibitions

to judicial action.8 Therefore, action by a federal court

is governmental action within the Fifth Amendment when

ever the same action by a state court would be state action

within the Fourteenth Amendment. Although in Hurd v.

Hodge,9 the Court reached the result of denying judicial

enforcement to the racial restriction on grounds other than

the Fifth Amendment, this was simply because it was un

necessary to do so. Said the Court :10

“ Petitioners urge that judicial enforcement of the

restrictive covenants by courts of the District of

Columbia should likewise be held to deny rights of

white sellers and Negro purchasers of property,

guaranteed by the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment. Petitioners point out that this Court in

HirabayasM v. United States, 320 IT. S. 81, 100

(1943), reached its decision in a case in which issues

under the Fifth Amendment were presented, on the

assumption that ‘ racial discriminations are in most

circumstances irrelevant and therefore prohibited

* * * ’ And see Korematsu v. United States, 323

U. S. 214, 216 (1944).

“ Upon full consideration, however, we have found

it unnecessary to resolve the constitutional issue

which petitioners advance; for we have concluded

8 See Griffin v. Griffin, 327 U. S. 220, 66 S. Ct. 556, 90 L. Ed.

635 (1946) ; Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U. S. 409, 17 S. Ct. 841, 42 L.

Ed. 215 (18 97 ); Hurd v. Hodge, 82 App. D. C. 180, 162 F. (2d)

233 (1947)——dissenting opinion Edgerton, J., at 162 F. (2d) 239-240.

9 334 U. S. 24 (1948).

10 Op. cit., supra, pp. 29-30.

19

that judicial enforcement of restrictive covenants by

the courts of the District of Columbia is improper for

other reasons hereinafter stated,” 11

Unquestionably, Sections 41 and 43 of Title 8 of the

United States Code, like any other Federal statute, inhibit

action of this Court. It is likewise clear that they also in

hibit judicial action of a state to the same extent that they

inhibit legislative action of a state. In Hurd v. Hodge,12

where the Court held that judicial enforcement of a restric

tive covenant, of the type involved in Shelley v. Kraemer,

was prohibited by Section 42 of Title 8 of the United States

Code, said: 13

“ In considering whether judicial enforcement of

restrictive covenants is the kind of governmental ac

tion which the first section of the Civil Eights Act of

1866 was intended to prohibit, reference must be

made to the scope and purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment; for that statute and the Amendment

were closely related both in inception and in the ob

jectives which Congress sought to achieve.

“ Both the Civil Eights Act of 1866 and the joint

resolution which was later adopted as the Fourteenth

Amendment were passed in the first session of the

Thirty-Ninth Congress. Frequent references to the

Civil Eights Act are to be found in the record of the

legislative debates on the adoption of the Amend

ment. It is clear that in many significant respects

the statute and the Amendment were expressions of

11 It is a well-established principle that this Court will not decide

constitutional questions where other grounds are available and dis

positive of the issues of the case. Recent expressions of that policy

are to be found in Alma Motor Co. v. Timken-Detroit Axle Co., 329

U. S. 129 (19 46 ); Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549

(1947).

12 Op. cit., supra, note 9.

18 Op. cit., supra, at pp. 31-33.

20

the same general congressional policy. Indeed, as

the legislative debates reveal, one of the primary

purposes of many members of Congress in support

ing the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment was

to incorporate the guaranties of the Civil Right Act

of 1866 in the organic law of the land. Others sup

ported the adoption of the Amendment in order to

eliminate doubt as to the constitutional validity of

the Civil Rights Act as applied to the States.

“ The close relationship between Section 1 of the

Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment was

given specific recognition by this Court in Buchanan

v. Warley, supra, at 79. There, the Court observed

that, not only through the operation of the Four

teenth Amendment, but also by virtue of the ‘ stat

utes enacted in furtherance of its purpose,’ includ

ing the provisions here considered, a colored man is

granted the right to acquire property free from in

terference by discriminatory state legislation. In

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, we have held that the

Foui’teenth Amendment also forbids such discrimina

tion where imposed by state courts in the enforce

ment of restrictive covenants. That holding is

clearly indicative of the construction to be given to

the relevant provisions of the Civil Rights Act in

their application to the Courts of the District of

Columbia.”

While, In Hurd v. Hodge, the Court was concerned with

Section 42, in view of the legislative scheme and history

of the Civil Rights Act, it cannot be questioned that Sec

tions 41 and 43 extend their prohibitions to Federal and

state judicial action.

It is therefore clear that action of this Court is gov

ernmental action within the Constitution and laws of the

United States.

21

C.

Governments, State and Federal, Are Restrained

From Making Distinctions on the Basis

of Race or Color.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution

was designed primarily to benefit the newly freed Negro,14

but its protection has been extended to all persons within

the reach of our laws. By its adoption Congress intended

to create and assure full citizenship rights, privileges and

immunities for this minority as well as to provide for their

ultimate absorption within the cultural pattern of Ameri

can life.

As was said in one of the earlier cases in which the Su

preme Court of the United States was called upon to inter

pret the intent and meaning of this Amendment: 15

“ What is this but declaring that the law in the

States shall be the same for the black as for the

white; that all persons, whether colored or white,

shall stand equal before the laws of the States and,

in regard to the colored race, for whose protection

the Amendment was primarily- designed, that no

discrimination shall be made against them by law

because of their color? The words of the Amend

ment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they contain a

necessary implication of a positive immunity, or

right, most valuable to the colored race—the right

to exemption from unfriendly legislation against

them distinctively as colored; exemption from legal

discrimination, implying inferiority in civil society,

lessening the security of their enjoyment of the rights

which others enjoy, and discriminations which are

14 See Flack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (1908).

See also Cong. Globe Congress, 1st Session.

15 Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 307, 25 L. Ed. 664

(1880).

22

steps towards reducing them to the condition of a

subject race.”

Although the Supreme Court has undoubtedly limited the

scope of the Fourteenth Amendment more narrowly than

its framers intended,10 from its adoption to the present,

the decisions have almost uniformly considered classifica

tions and distinctions on the basis of race as contrary to its

provisions, and, under a variety of factual situations, our

highest Court has repeatedly held racial criteria arbitrary

and unconstitutional:

T ransportation :

McCabe v. Atchinson, T. & S. F. 1Ry. Co., 235 U. S.

151, 35 S. Ct. 69, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914); Mitchell v.

United States, 313 IT. S. 80, 61 S. Ct. 873, 85 L.

Ed. 1201 (1941); Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S.

373, 66 S. Ct. 1050 (1946); Bob-Lo Excursion Co.

v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28, 68 S. Ct. 358 (1948).

R estrictions on Ownership or Occupancy op P roperty :

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836 (1948);

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 68 S. Ct. 847 (1948);

Oyama v. California, 332 IT. S. 633, 68 S. Ct. 269

(1948); Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S.

Ct. 16, 62 L. Ed. 149 (1917); Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U. 8 . 668, 47 S. Ct. 411, 71 L. Ed. 831 (1927);

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 IT. S. 704, 50 S. Ct.

407, 74 L. Ed. 1128 (1930).

E ducation :

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 68 8. Ct.

299, 92 L. Ed. 256 (1948); Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337, 59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. Ed.

208 (1938).

'16 Flack, op. cit. supra; Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U. S. 78,

29 S. Ct. 14, 53 L. Ed. 97 (1908).

DlSRCIMINATION IN PAYM ENT OF TEACHERS’ SALARIES:

Alston y. School Board (C. C. A. 4th), 112 F. (2d)

992 (1940), cert, den. 311 IT. S. 693, 61 S. Ct. 75,

85 L. Ed. 448 (1940).

L ibrary F acilities:

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library (C. C. A. 4th),

149 F. (2d) 212 (1945), cert. den. 326 U. S. 721,

66 S. Ct. 26, 90 L. Ed. 427 (1945).

R estrictions on P ursuit of V ocation:

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410, 68 S. Ct. 1138 (1948); Tick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064, 30 L. Ed. 220 (1886).

E xclusion from P etit J u ry :

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 25 L. Ed.

664 (1880).

E xclusion from Grand J u ry :

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 26 L. Ed. 567 (1881).

E xclusion from V oting at P arty P rimary:

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 IT. S. 576, 47 S. Ct. 446, 71 L.

Ed. 759 (1927); Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73,

52 S. Ct. 484, 76 L. Ed. 984, 88 A. L. R. 458 (1932);

Smith v. Allwright, 319 IT. S. 738, 64 S. Ct. 757,

88 L, Ed. 987 (1944); Rice v. Elmore (C. C. A.

4th), 165 F. (2d) 387 (1948), cert. den. 333 IT. S.

875, 68 S. Ct. 905 (1948).

D iscrimination in R egistration P rivileges:

See Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct.

926, 59 L. Ed. 1340, L. R. A. 1916A, 1124 (1915);

Lane v. Wilson, 307 IT. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L.

Ed. 1281 (1939).

Despite the absence of a requirement for equal protec

tion of the laws in the Fifth Amendment, our national gov

24

ernment is prohibited from making distinctions on the basis

of race or color, since such distinctions are considered ar

bitrary and inconsistent with the requirements of due

process of law, except where national safety and the perils

of war render such measures necessary.17

The right of a person to the services of a common car

rier is even more strongly protected than the property

rights involved in the Shelley and Hurd cases, the eco

nomic rights involved in the Takahashi case, and the rights

respectively involved in the other cases referred to. The

obligation of a carrier to serve all who may apply and the

right to freedom of locomotion combine to create personal

rights which have long been recognized as possessed by all

of the people within the jurisdiction of the United States.

It could not be seriously contended that any state by

legislation could deny to any group of its citizens the right

of access to the services of common carriers solely on the

basis of their race or color. Moreover, freedom of locomo

tion of certain groups of persons may not be hampered by

state legislation even though for the laudable purpose of

protecting the property of persons already resident within

the particular state.18

The difference between a bus company and an ordinary

business operator is further emphasized by the fact that

17 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 63 S. Ct. 1375,

87 L. Ed. 1774 (1 9 4 3 ) ; Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214,

65 S. Ct. 193, 89 L. Ed. 194 (1 9 4 4 ) ; E x parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283,

65 S. Ct. 208, 89 L. Ed. 243 (1 9 4 4 ) ; Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24,

68 S. Ct. 847 (19 48 ); See also Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323

U. S. 192, 65 S. Ct. 226, 89 L. Ed. 173 (19 44 ); Tunstall v. Brother

hood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210, 65 S.

Ct. 235, 89 L. Ed. 187 (1944).

18 Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 62 S. Ct. 164, 86 L. Ed.

119 (1941).

25

the bus company in performing a public function,19 enjoys

monopolistic privileges and is permitted under certain cir

cumstances to avail itself of the right of eminent domain.

Its rules and regulations in so far as they affect the travel

ing public are, as has been aptly stated by one court,

“ minor laws” .20

D,

Enforcement of the Regulation Is Violative of the

Constitution and Laws of the United States.

If it be contended that the relationship between carriers

and their respective passengers is determined, not by state

law, but, because of the various transportation acts and the

commerce clause, is fixed entirely by federal common law,

the complete answer is that the limitations of the Fifth

Amendment apply in the same way in which the Court in

Shelley v. Kraemer,21 held that the limitations of the Four

teenth Amendment applied, and that these limitations, and

those specified in applicable Federal statutes, require that

it be held that the regulations in question are invalid.

Two national interests are involved in the handling of

interstate passenger traffic: (1) There is the over-all na

tional interest of free flow to commerce, and (2) there is

the national interest that no distinction because of race,

color or national origin shall be permitted in areas sub

ject to national control.22 Neither of these can be sub

served otherwise than by adjudication of the invalidity of

the regulation in question.

19 See Constitution of Virginia, Sec. 153; Code of Virginia, 1942,

Sec. 3881.

20 South Florida R. Co. v. Rhoads, 25 Fla. 40, 5 So. 623, 3 L. R.

A. 733, 737 (1889).

21 334 U. S. 1, 20-21, 68 S. Ct. 836, 845, 846 (1948).

22 Cf. Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28, 68 S. Ct.

358 (1948).

26

E.

The Decision of the Court in This Case Cannot Be

Controlled by the Decisions in Either Chiles v.

C hesapeake & O. R. Co. or Plessy v. Ferguson.

In Plessy v. Ferguson,23 24 25 26 defendant, seven-eighths white

and one-eighth Negro, purchased a ticket for transportation

between two points in Louisiana. He occupied a seat in the

“ white” coach, and was ejected therefrom and arrested for

violation of a state statute requiring separate coaches for

the races. This act had previously been construed as

limited in operation to intrastate passengers.24 A demurrer

to defendant’s plea that the statute was unconstitutional

was sustained, whereupon defendant filed a petition for

writs of prohibition and certiorari in the state supreme

court, which upheld the validity of the act. On writ of

error to the Supreme Court of the United States, it was

contended that the act violated the Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments. The Court held that the statute was

valid as applied to intrastate commerce. Mr. Justice H arlan

dissented.

In Chiles v. Chesapeake & 0. R. Co.,25 plaintiff, a Negro,

sued the carrier for his ejection in Kentucky from the

“ white” car on the train in question. Plaintiff was an in

terstate passenger and defendant an interstate carrier.

Kentucky’s separate coach law had previously been con

strued as limited in operation to intrastate passengers,20

and the defendant carrier did not rely upon the same, but

23 1 63 U. S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256 (1896).

24 State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 S. 75 (1892).

25218 U. S. 71, 30 S. Ct. 667, 54 L. Ed. 936 (1910).

26 Ohio Valley Ry.’s Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431, 47 S. W .

344 (1898) ; Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 338,

21 S. Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900).

27

claimed that, in excluding plaintiff from the car in ques

tion, it acted pursuant to its rules and regulations. Plain

tiff contended that the regulation was invalid as to him

because he was an interstate passenger. The Court stated :27

“ And we must keep in mind that we are not deal

ing with the law of a State attempting a regulation

of interstate commerce beyond its powder to make.

We are dealing with the act of a private person, to-

wit, the railroad company, and the distinction be

tween state and interstate commerce we think is un

important.”

Continuing, the Court quoted with approval from Hall v.

DeCuir,28 and said: 29 30

“ This language is pertinent to the case at bar,

and demonstrates that the contention of the plain

tiff in error is untenable. In other words, demon

strates that the interstate commerce clause of the

Constitution does not constrain the action of car

riers, but, on the contrary, leaves them to adopt

rules and regulations for the government of their

business, free from any interference except by Con

gress. * * * In other words, the statute was struck

down because it interfered with the regulation of the

carrier as to interstate passengers. * * * ”

Continuing, the Court, referring to Plessy v. Ferguson,

stated: 80

“ It is true that the power of a legislature to

recognize a racial distinction was the subject con

sidered, but if the test of reasonableness in legisla

tion be, as it w7as declared to be, ‘ the established

usages, customs, and traditions of the people,’ and

27 30 S. Ct. at 668.

28 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547 (1877).

29 30 S. Ct. at 669.

30 30 S. Ct. at 669.

28

the ‘ promotion of their comfort and the preservation

of the public peace and good order,’ this must also

be the test of the reasonableness of the regulations

of a carrier, made for like purpose and to secure

like results. Regulations which are induced by the

general sentiment of the community for whom they

are made and upon whom they are to operate can

not be said to be unreasonable.”

Although the Supreme Court has never expressly over

ruled Plessy v. Ferguson or Chiles v. Chesapeake & 0. R.

Co., even the most cursory examination of the cases in

volving the rights of Negroes and other minorities as guar

anteed by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution clearly demonstrates that these

cases no longer are expressive of the interpretation of the

present United States Supreme Court of the scope and

effect of these amendments.

The synical sophistry of Justice Brown 31 is outmoded

and is as typcial of the views of the Supreme Court today

or of the thoughts of informed people,31 32 as are the coaches

3116 S. Ct. at p. 1143. “ W e consider the underlying fallacy of

the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced

separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of

inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the

act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construc

tion upon it.”

32 The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights at p.

79. “ Mention has already been made of the ‘separate but equal’

policy of the southern states by which Negroes are said to be entitled

to the same public service as whites but on a strictly segregated basis.

The theory behind this policy is complex. On one hand, it recognizes

Negroes as citizens and as intelligent human beings entitled to enjoy

the status accorded the individual in our American heritage of free

dom. It theoretically gives them access to all the rights, privileges,

and services of a civilized, democratic society. On the other hand, it

brands the Negro with the mark of inferiority and asserts that he is

not fit to associate with white people.” (Italics supplied.)

29

of that day representative examples of modern rail trans

portation. In addition, such views are at variance with

fact.33

In 1895 and 1910 the prevailing sentiment in this country

appears to have been that this country was self-sufficient

and could hold itself aloof from the rest of the world. To

day, after the experience of two world wars, it is generally

recognized that the destiny of this country is interwoven * 81

83 The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights at p.

81. “ This judicial legalization of segregation was not accomplished

without protest. Justice Harlan, a Kentuckian, in one of the most

vigorous and forthright dissenting opinions in Supreme Court history,

denounced his colleagues for the manner in which they interpreted

away the substance of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

In his dissent in the Plessy case, he said:

‘Our Constitution is color blind, and neither knows nor

tolerates classes among citizens. * * *

‘W e boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all

other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with

a state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servi

tude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens,

our equals before the law. The tin disguise of “ equal” ac

commodations * * * will not mislead anyone, or atone for the

wrong this day done.’

If evidence beyond that of dispdssionate reason was needed to

justify Justice Harlan’s statement, history has provided it. Segre

gation has become the cornerstone of the elaborate structure of dis

crimination against some American citizens. Theoretically this sys

tem simply duplicates educational, recreational and other public ser

vices, according facilities to the two races which are ‘separate but

equal. In the Committee s opinion this is one of the outstanding

myths of American history for it is almost always true that while

indeed separdte, these facilities are far from equal.” (Italics supplied.)

30

with that of other countries all over the world.34 And since

three-fourths of the world’s population consists of colored

or non-white persons, an attitude of smug racial aloofness

is no longer compatible with sound national policy.35

34 United Nations Charter approved by U. S. Senate, Dec. 20,

1945:

“ Article 55

“ With a view to the creation of conditions of stability and well

being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among

nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-

determination of peoples, the United Nations shall promote: * * *

c. Universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and

fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, lan

guage or religion.

“ Article 56

“ All members pledge themselves to take joint and separate action

in cooperation with the Organization for the achievement of the pur

poses set forth in Article 55.”

85 Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, p. 146.

“ In a letter to the Fair Employment Practice Committee on May

8, 1946, the Honorable Dean Acheson, then Acting Secretary of State,

stated that:

‘ * * * i-pg existence of discrimination against minority groups

in this country has an adverse effect upon our relations with

other countries. W e are reminded over and over by some

foreign newspapers and spokesmen, that our treatment of

various minorities leaves much to be desired. While some

times these pronouncements are exaggerated and unjustified,

they all too frequently point with accuracy to some form of

discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin.

Frequently we find it next to impossible to formulate a satis

factory answer to our critics in other countries; the gap be

tween the things we stand for in principle and the facts of a

particular situation may be too wide to be bridged. An atmos

phere of suspicion and resentment in a country over the way

a minority is being treated in the United States is a formidable

obstacle to the development of mutual understanding and trust

between the two countries. W e will have better international

relations when these reasons for suspicion and resentment have

been removed.

‘ I think it is quite obvious * * * that the existence of

discriminations against minority groups in the United States

is a handicap in our relations with other countries. The De

partment of State, therefore has good reason to hope for the

continued and increased effectiveness of public and private

efforts to do away with these discriminations.’ ” (Italics sup

plied.)

31

For more than twenty years the Supreme Court has

been gradually demonstrating an acute sense of awareness

of the dangers in the rationale of the Plessy and Chiles

cases and has moved farther and farther from the philos

ophy which those cases expounded.

Bob-lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan 86 is a case not directly

involving the Thirteenth, Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amend

ments in which the Court cast aside technical difficulties

and asserted the validity of a position which safeguarded

the rights of Negroes. The Excursion Co. invited all comers

to utilize its facilities, save disorderly persons and Negroes.

It was prosecuted under Michigan’s Civil Rights Statute,

and the Company sought to escape liability on the grounds

that the Act did not apply to it for the reason that it op

erated between Detroit and an island in the Province of

Ontario, Canada, and was therefore engaged in foreign

commerce. After noting that the traffic on the carrier was

confined exclusively to its private island, the Court said :37

“ It is difficult to imagine what national interest

or policy, whether of securing uniformity in regulat

ing commerce, affecting relations with foreign na

tions, or otherwise, could reasonably be found to be

adversely affected by applying Michigan’s statute to

these facts or to outweigh her interest in doing so.

Certainly there is no national interest which over

rides the interest of Michigan to forbid the type of

discrimination practiced here. And, in view of these

facts, the ruling would be strange indeed, to come

from this Court, that Michigan could not apply her

long-settled policy against racial and creedal dis

crimination to this segment of foreign commerce, so

peculiarly and almost exclusively affecting her people

and institutions.

‘ ‘ The Supreme Court of Michigan concluded ‘ That

holding the provisions of the Michigan statute effec- 38

38 3 33 U. S. 28, 68 S. Ct. 358 (1948).

87 68 S. Ct. 364.

tive and applicable in the instant case results only

in this, defendant will be required in operating its

ships as “ public conveyances” to accept as passen

gers persons of the negro race indiscriminately with

others. Our review of this record does not disclose

that such a requirement will impose any undue bur

den on defendant in its business in foreign com

merce.’ 317 Mich. 689, 27 N. W. 2d 139, 142̂ Those

conclusions were right.”

In a concurring opinion by Mr. Justice D ouglas, in which

Mr. Justice B lack joined, it was stated:38

“ It is unthinkable to me that we would strike