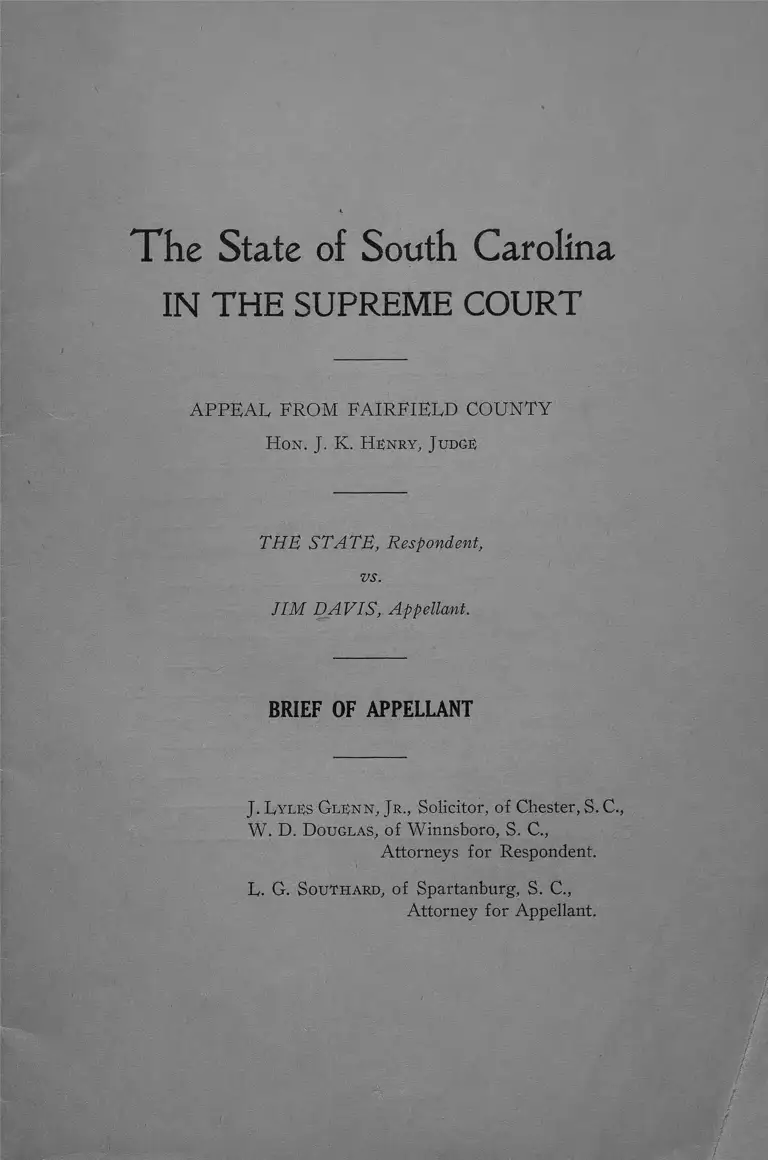

State v. Davis Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State v. Davis Brief of Appellant, 8bd5380b-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2b254815-21a5-487f-a208-b841fcf959e6/state-v-davis-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

T h e State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

APPEAL FROM FAIRFIELD COUNTY

H o n . J. K. H en ry , Judge

THE STATE, Respondent,

vs.

JIM DAVIS, Appellant.

BRIEF OF APPELLANT

J. L yles G l e n n , Jr ., Solicitor, of Chester, S. C.,

W . D. D ouglas, of Winnsboro, S. C.,

Attorneys for Respondent.

L. G. Southard , of Spartanburg, S. C.,

Attorney for Appellant.

INDEX

P age

St a t e m e n t .......................................................................................... 3

As to th e U ndisputed F a c t s .......... ................................... 4

E xceptions—

Change of Venue.............................................................. 7

As to the Admissibility of Testimony ......................... 9

Refusal of Motion to Direct a Verdict......................... 12

As to the Rejection of Testimony for Defendant......... 14

As to Res Gestae........................................................... 19

As to His Honor’s Refusal to Direct a Verdict at the

Close of the Whole Case, Etc.................................. 21

As to the Charge on Murder and Malice, Etc.............. 22

As to Errors in Charging on Appearances................... 26

Exceptions Charging Errors on the Part of His Honor

in Charging the Law of Self Defense................. 27

As to the Charge on the Law of the Castle................. 33

As to Requests to Charge ............................................. 39

Co n c l u s io n ......................................................................................... 41

STATEM ENT

The charge was murder; appellant was tried before Judge

J. K. Henry and a jury in Fairfield County, and he was con

victed of murder with recommendation to mercy.

There are fifty-two exceptions. They will be grouped to

gether in a number of instances, so that there are not so many

questions to be considered. The exceptions go to the refusal

to change the venue, the admission of testimony, the rejection

of testimony, errors in hte charge of murder, self defense, the

law of the castle; the failure to charge correctly the law of

murder, self defense, and the law of the castle, the refusal to

grant a directed verdict of not guilty, both at the close of the

State’s, case and at the close of the whole case, the refusal to

strike from the indictment the charge of murder, and if sub

mitted at all, then to be submitted on the charge of man

slaughter, the refusal to grant a new trial, and from the charge

as a whole.

Appellant was sentenced to life imprisonment. Due and

legal notice to appeal to this Honourable Court was served and 2

filed.

The shooting occurred in Fairfield County, in the sixth

circuit, and death occurred in Richland County, in the fifth

circuit. Motion was made on a verified petition of Jim Davis,

the appellant, for a change of venue. This petition was sup

ported by an affidavit of E. G. Southard, attorney for Jim

Davis, and the Court is asked to read and consider both; it will

be seen that the facts therein stated are in no wise contradicted.

Testimony purporting to be and prove a dying declaration

was offered by the State; objection was made that the same

in no wise met the test; His Honor admitted the same. Testi

mony was offered by the State from Jack Jewett and Willie

Worthy that they had married children of appellant, this was

objected to, objection overruled, and testimony admitted.

Testimony on behalf of the appellant as to just what was

said and just what occurred between Mr. G. E. Martin and

appellant a moment or so before the shooting was offered

on two grounds, (a) to show the mental condition of the ap

pellant just before and just at the time of the homicide; and, 4

(b) as a part of the res gestae. His Honor refused to admit

this testimony. Errors were made in the charge and in refusals

to charge.

4 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

AS TO THE UNDISPUTED FACTS

The attention of the Court is invited to the Statement of the

Case, for it is our contention that the agreed facts entitle us to

a reversal under Rule X X V II o f this Court. From the ad-

5 mitted facts, appellant is entitled to a verdict of Not Guilty.

The Satement shows that the deceased was a white man,

of a large, prominent, influential, and widely scattered family,

of Fairfield County. That the shooting was done in Fairfield

County, that death occurred in Richland County. That large

bands of armed men hunted appellant, that sentiment was

strong against him, that the Governor, as a precautionary

measure, confined the appellant in the penitentiary until some

time in February.

The Statement further shows that appellant is fifty-one

years of age, that he has lived all of his life in Fairfield County,

having been reared by Captain John W . Eyles, the venerable

Clerk of Court for Fairfield County, that he had never in his

life heretofore been in trouble of any kind.

The Statement further shows that the appellant lived on

the lands of Mr. D. R. Martin, with his wife and family, and

had no trouble until a road gang camped within about one-half

mile from his home. That he had two youthful daughters,

7 one about thirteen years of age, another about fourteen years

of age; and that on Sunday, some few days before the homi

cide, these two children with another negro girl of the com

munity were surreptitiously taken by three negro boys, one

of whom was Jack Jewett, and were by them taken to Columbia

where they slept with them, and from thence to Greenwood,

and there kept by them for several days, and then were taken

back to appellant’s home, where he received them back under

the representation to him that they were married and under

8 their promise to produce the marriage certificates.

The Statement further shows that there never existed

betwixt Mr. Scott and appellant any cross words or ill feelings,

that the only reason why appellant fired was to repel an in-

SUPREME COURT 5

Appeal from Fairfield County

vasion of his home, to keep Mr. Scott out of his home and

yard, and to keep him from taking his children out of his home,

in defense of himself and family, and to keep invaders and

intruders out of his home, and to prevent them from taking

his daughters out of his home, to expel Austin Scott and Jack

Jewett and Willie Worthy from his home. The sole con- 9

tention of the State was that at the instant the shot was fired,

it was not necessary to have fired it, as though appellant could

divide seconds into fractions.

The Statement further shows that on Monday morning, the

morning of the homicide, that appellant had a conversation with

Jack Jewett and Willie W orthy; they having spent the previous

night at his home. That they went to the camp, and shortly

thereafter they returned to the home of appellant in a truck

for the two girls, that when they drove up that appellant was 10

in his front yard with his shotgun in his hands, that at that

time he told them that they could never come into his house

again, that if they desired to talk to the girls that they could

do so from a designated spot on the outside of the fence. That

at that time he told them again that he was not going to let

his girls go off with them to Georgetown County, “ that he

had rather follow them to the graveyard than to see them live

in a negro camp.” That the boys talked to the girls a moment

or so, got back on the truck, and for a second time went u

back to the grade camp.

The Statement further shows that at this instant appellant

sent his son for his landlord, Mr. D. R. Martin, to come to his

house at once; that just before that he had sent for Mr. G. E.

Martin, his nearest neighbor, in consequence of a communi

cation he had had with Robt. Duffey, appellant saw Mr. G. E.

Martin coming up the public road, he ran out and had a con

versation with him, then ran back to his home. His son had

just returned from Mr. D. R. Martin’s.

The Statement further shows that when Jack Jewett and

Willie Worthy reached the camp there was Mr. Scott. They

told him that they were unable to get their wives, that Jim

6 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

Davis would not let them go, and that he would not let them

go into his house. He, J. Austin Scott, then told them that he

would go and get them. Turning to a man, he inquired of him

where was his pistol. Upon being told that it was in a handbag,

he went and got it. It was a 38. Special Smith & Wesson.

13 Broke it down, examined it, saw that it had four good car

tridges in it, inquired for more cartridges, upon being informed

that there were no more, in speaking of going to appellant’s

home after these girls, said: “ This is enough to bring two or

three back with.” Got on the truck with the two negro boys,

told them to drive, and started for Jim Davis’ house with them.

The Statement further shozvs that to go to appellant’s home,

the truck had to pass by Mr. D. R. Martin’s residence; that

Mr. Martin had just started to appellant’s home in response

14 to his message to come when the truck approached Martin’s

house. That the truck stopped, there was a conversation, the

truck moved on, Martin following it, walking; that he met

Mr. G. E. Martin, that he turned around, and that the two

Martins started to appellant’s home following the truck.

The Statement further shows that appellant’s home was

six hundred feet off the public road, and that there was only

one private road down to his house; that the truck drove down

this private road, went down to the house, turned around and

15 headed out toward the public road and stopped, and that off

of it jumped / . Austin Scott, Jack Jewett and Willie Worthy.

That their business now was to take these children of ap

pellant’s.

The Statement further shows that there is a fence in front

of appellant’s dwelling and attached to the corner of the house.

The Court’s attention is invited to the photographs incorporated

in the Case. That the front gate was less than seventeen feet

from appellant’s front door. That when the truck drove up,

16 appellant was standing in his front door with his shotgun in his

hand. That when Mr. Scott jumped off of the truck he had

both of his hands in his front trousers pockets and that he

and Willie Worthy and Jack Jewett simultaneously advanced

SUPREME COURT 7

Appeal from Fairfield County

on appellant’s dwelling house; the negro boys, however, halted,

but Scott kept advancing, with both hands in his pockets,

around the fence to the gate and into the gate, less than

seventeen feet from appellant’s door, when the shot was fired

which resulted in Mr. Scott’s death. That at that time there

was in appellant’s dwelling his wife and children, the youngest 17

was three years of age, Sarah Rabb, who was to slip away

and go with the negroes to Georgetown, and Robt. Dotson.

The Statement further shows that there were several eye

witnesses, and Mr. Southard moved that the State be required

to put all eye witnesses up. He stated that they would not talk

to him; hence, he was in no position to know just what they

would swear.

The Statement further shows that proper motions were

made for a directed verdict of Not Guilty at the close of the 18

State’s Case, which motion was refused; and, also, a motion

was made to eliminate murder from the indictment, which

was refused. At the close of the whole Case, a motion was

made for a directed verdict of Not Guilty, which was re

fused, and then motion was made to eliminate murder, and

this was refused.

Hence, from the admitted facts of the Statement of the

Case, it is most respectfully urged that appellant’s defenses

are fully admitted, and under Rule X XV II, this Court should 19

order a verdict of Not Guilty entered, and he should be dis

charged.

EXCEPTIONS

C hange; of V bnue;

Section III of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1922, pro

vides that where a person is shot in one county and dies thereof

in another, the defendant may be tried in either county. In 20

State vs. McCoomer, 79 S. C. 65, the Supreme Court held

that the offense is to be considered committed in both counties

and is triable in either.

8 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

On the face of the indictment, it is alleged that the shooting

was in Fairfield County, that death resulted in Richland County.

Under the law, the trial could have been in either county.

Under the showing made before the Circuit Judge, it is sub

mitted that in Fairfield County a fair and impartial trial could

not be had. In addition to a full and complete showing made

by the verified petition and the affidavit of Mr. Southard that

the appellant could not receive a fair and impartial trial as is

contemplated by law and guaranteed to him by the Constitution,

the situation was peculiar in that it was made to appear that

Austin Scott and the solicitor were related, and that that fact

was generally known in Fairfield County. It could not be kept

out of the case, the personal element, the solicitor being a

Judicial Officer of the Court, and the appellant charged with

22 slaying a kinsman of the solicitor. Mr. Glenn in nowise is

subject to criticism. So far as his attitude during the trial

was concerned, no exception could be taken. Yet the public

generally knew it, the jurors knew it.

Moreover, the showing was that the deceased was a member

of a large, prominent, influential family; at one time an officer

of the county, having relatives widely scattered in the county

- who were active in the prosecution of the Case, one of whom

was at the time of trial a member of the rural police force of

Fairfield County. That appellant had sought the services of

attorneys of the Winnsboro Bar, who expressed themselves

favorable to his defense, but who declined to defend for the

reason that it would injure their practice, although the family

of deceased hired an attorney of Winnsboro to prosecute. That

Fairfield County had been and was divided over the Isenhour-

Hood battle, wherein Scott was a member of the Hood faction,

and was charged with having been the one who killed Mr.

Isenhour. The strong sentiment against appellant, rushing

him to the penitentiary—these and the other facts shown

24 should have impelled the Judge to have moved the trial of this

case to another county or to Richland County.

It is conceded that the question is primarily addressed to

the discretion of the Presiding Judge, but his discretion must

SUPREME COURT y

Appeal from Fairfield County

be judcial and not arbitrary. State vs. Jackson, 110 S. C. 273.

Affidavits on the other side admitted everything charged by

the appellant, they simply stated that now it was thought that

a fair trial could be had. However, no facts were stated by

the State. This covers Exception One.

As to th e A d m issibility of T estim ony

In Exception Two is challenged the correctness of His

Honor’s rulings in admitting Dr. Wallick’s testimony in

reference to a conversation which he claimed he had with

deceased as a dying declaration.

“ To render these declarations admissible, it was only

necessary that the trial judge should be satisfied: First, that the

death of the deceased was imminent at the time the declara- 2*>

tions were made; second, that the deceased was so fully aware

of this as to be without hope of recovery; third, that the

subject of the charge was the death of the declarant, and the

circumstances of the death were the subject of the declarations.”

State vs. Petsch, 43 S. C. 148.

State vs. Faile, 43 S. C. 52.

State vs. Taylor, 56 S. C. 360.

State vs. daggers, 58 S. C. 360.

State vs. McCoomer, 79 S. C. 63. 27

State vs. Gallman, 79 S. C. 229.

State vs. Franklin, 80 S. C. 332.

State vs. Smalls, 87 S. C. 551.

State vs. Long, 93 S. C. 502.

State vs. Hall, Advanced Sheets, Opinion by Cothran, /■

In the case of Stae vs. Smalls, 87 S. C. 550, it was held:

“ These cases further declare that the Circuit Court primarily

decides whether these conditions exist, and its rulings will not

be disturbed unless clearly incorrect and prejudicial.” And to 28

like effect are State z>s. McCoomer, 79 S. C. 63, State vs.

Franklin, 80 S. C. 332. However, in the case of State vs.

Belcher, 13 S. C. 462, the rule was stated to be as follows:

10 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

“ They are admissible from the necessity of the case, and

when made in extremity, when the party is at the point of

death and is conscious of it, when every hope of this

world is gone, and every motive to falsehood is silenced

by the most powerful considerations to speak the truth.”

29

Again in State vs. Thomas, 103 S. C. 316, the Court said:

“ The deceased and the witness talked about death, but

men may talk about death who do not think they are about

to die.”

Again in State vs. McBvey, 9 S. C. 208, the rule is stated:

“ And the declarant was so fully aware of this (mean

ing death) as to be without any hope of life.”

Again in State vs. Riley, 98 S. C. 386, the Court said:

30 “ Considered inversely, the dying declaration was not

competent, it did not sufficiently appear that death was

imminent and that the declarant had abandoned all hope

of recovery. Mr. McDowell, who took the declaration, is

a lawyer and magistrate. lie warned the declarant, ‘he

must be certain he was going to die.’ The answer was,

‘Yes, I am going to die. I may get up for a few days,

but this wound will kill me.’ At another time the witness

testified that the declarant said, ‘Yes, I may get up for a

few days, but this shot will eventually kill me.’ The wit-

31 ness further testified, ‘He didn’t say that he would die

from his wound any time soon, nor did he state any time

at which he would die from it.’ ”

Now, testing Dr. Wallick’s testimony as to the claimed con

versation, it is apparent that His Honor’s ruling was clearly

incorrect and prejudicial. It did not appear that death was

imminent, neither did it appear that the declarant was so

conscious of hnminent death as to be without any hope of

recovery. Here is exactly what the doctor said Scott said:

32 “ I don’t believe I am going to make it.” He did not say that

death was even once mentioned by Scott or anyone else. He

stated that Scott had a doubt as to whether or not he would

make it.

SUPREME COURT 11

Appeal from Fairfield County

The words show that the declarant had not abandoned all

hope. “ I don’t believe I am going to make it,” shows that in

this man’s mind, if he was thinking of death, that it was

questionable with him whether he would make it or not. The

test therefore had not been met. His Honor was clearly in

error in admitting this.

Exception Three charges error in striking out the testimony

of Sheriff MacFie, wherein he stated that J. Austin Scott bore

a bad reputation for turbulence and violence amongst negroes

in Fairfield County. I understand the rule as laid down in

State vs. Dean, 72 S. C. 74, State vs. Boyd, 126 S. C. 300, and

a large number of cases that where the reputation of a person

deceased is attempted to be shown that specific acts of violence

cannot be shown; but where one has a bad reputation for

turbulence and violence amongst negroes, this is general reputa- 34

tion within a class, and particularly is it competent where the

defendant belongs to that class. I have found no case hold

ing this, but it appeals to me from the standpoint of right and

reason.

Exceptions Four and Five go to the admissibility of the

testimony of Jack Jewett and Willie Worthy, in that His Honor

permitted them to testify that they were married to Sarah and

Clara respectively, the children of appellant. If the parties

were married, then the father had every right to know that

they were, and proof thereof should have been submitted by

producing the record of the Judge of Probate for Greenwood

County. If they were living in a state of concubinage, then

the father had every right to keep his daughters from going

to Georgetown County. And if they were not married, the

negro men were guilty of statutory rape. The admission was

highly prejudicial. The rights of a father were at stake,

and since marriage in South Carolina is entered into only

after a license is issued, and since the law requires that the

proof of the marriage must be recorded, the record was the 36

best evidence.

The reason why the testimony was offered which is referred

to in Exception Six was to show just what conclusion a man

12 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

of ordinary reason and prudence would reach under the facts

and circumstances. It was competent.

R efusal of M otion to D irect a V erdict

37

If all of the evidence is susceptible of but one inference,

and if the defenses of the defendant are established by it, then

it becomes the duty of the Presiding Judge upon motion to

direct a verdict of Not Guilty. Exception Seven challenges

His Honor’s ruling on a motion for a directed verdict.

Only one inference could have been drawn from the testi

mony. The defendant was in his own home, where he was

entitled to be, with his wife and children. Pie had tried in

every way possible to prevent any attack from being made on

38 it, and to keep all intruders and aggressors out. The deceased

knew that He was not wanted there and on this particular

mission, so much so, that when he started on it, after thoroughly

arming himself, he exclaimed, “ This is enough to bring two

or three back with.” He had just been told that the old man

would not allow these negroes to go into the house, neither

would he permit the girls to come out of the house. So

opposed was he to their going, under the circumstances, that

to express it in his own words, coming from the State’s

39 witness, he told them that he had rather follow his girls to

the graveyard than to see them living in tents in a negro road

camp. The boys had been for the girls, and had been re

fused them by their father, and this was told to Mr. Scott.

Yet he determined that he would go and get them, and he took

along a 38 Special Smith & Wesson to bring them back with.

The old man had sent for his landlord, and his son, whom He

had sent, had returned; and he knew that the truck had to pass

Mr. Martin; he had sent for his white neighbors. Yet, in spite

of warnings, refusals, orders, and protestations, the truck was

40 back with the same negro boys, he had just a few moments

before ordered away, with J. Austin Scott. Simultaneously, all

three jumped from the truck and advanced in a threatening

attitude onto his house. Two stopped, but Scott kept advanc-

SUPREME COURT 13

Appeal from Fairfield County

ing to the fence, to the gate, inside of the gate. Must this man

divide seconds into fractions ? Already the aggressor is within

the gate, less than seventeen feet from the front door, still in

a threatening attitude. He is not there as a licensee, or as an

invited guest. Scott knew that his presence was not desired,

and he knew that he had no permission to be thus advancing 41

onto this man’s home, either by implication or by expression.

No invitation had been extended him to come, yet here he was.

What must Jim Davis do? Must he retreat? The law says

“ no.” What would a man of ordinary reason and firmness

conclude? What did Jim Davis conclude? Had he not at this

point met the test under the law of the castle, as declared

by Justice Cothran in State vs. Bradley, 120 S. C. 240?

Ordinarily it is a jury question, but where the facts and cir

cumstances point only one way, then the law is different, and 42

it is the facts which breed the law. Must a parent stand in

his door and plead with one not to come into his dwelling and

take his children out, even though his two daughters have been

debauched and ruined, and then fight the elements of heat and

cold and mud and dirt and rock for the balance of his life

for the State, and like poor old King Dear say:

“ Spit, fire! Spout, rain !

Nor rain, wind, thunder, fire, are my daughters;

I tax not you, you elements, with unkindness ;

I never gave you kingdom, call’d you children,

You owe me no subscription; then let fall

Your horrible pleasure; here I stand, your slave,

A poor, infirm, weak and despised old man,

But yet I call you servile ministers—-

That have with two pernicious daughters join’d

Your high-engendered battles ’gainst a head

So old and white as this. O ! O ! ’Tis foul.”

Under no aspect of the State’s case was there murder.

His Honor should have on motion eliminated the charge of 44

murder, and if submitted at all, the case should have been

submitted only on the question of manslaughter. This goes

to the Eighth Exception.

14 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

As to th e R ejection oe T estim o n y for D efendant

Exceptions Nine and Ten go to practically the same ques

tions, and they will, therefore, be considered together. The

evidence sought to be introduced covered by these two ex-

45 ceptions was offered on two grounds; to wit, as a part of the

res gestae, and to explain and show the mental condition of the

defendant at the time.

The Court will recall that information had been given de

fendant by Robt. Duffey the night before of the coming of

J. Austin Scott, and for the exact purpose for which he did

later come; of the sending after Mr. G. E. Martin before

breakfast the next morning, the morning of the homicide, by

the defendant; of the return of Jack Jewett and Willie Worthy

in the truck for the girls, of the defendant’s refusal to permit

46 them to go into his yard or house, or the negroes talking with

the girls at the designated window, and of the departure of the

boys, Jack Jewett and Willie Worthy, after Mr. G. E. Martin

had gotten in sight, and of the defendant at the moment

sending for Mr. D. R. Martin, his landlord. At this instant,

defendant ran to the road and met Mr. G. E. Martin.

It was instantaneous, spontaneous, contemporaneous; it was

a part of it, and while the negroes, Jack Jewett and Willie

Worthy, were gone for J. Austin Scott—they were just turn-

47 ing into the public road. “ Mr. Martin, come up to my house.

I am having trouble with those boys about taking off my girls ;

the girls say that they don't want to g o ; and the boys say that

they are going' back, and come back and raise hell or have a

damn war one.” What was said between Mr. Martin and

the defendant at that instant about his being in a hurry to get

to the camp, that he would see the parties and stop them, and

about Mr. D. R. Martin seeing them and stopping them, and that

he wouldn’t let them come to his home, certainly was compe

tent to show the mental condition of the defendant just a few

48 moments before the homicide, and to explain his acts and con

duct just at the moment, and it was a part of the transaction,

tended to elucidate it, and was so near to it as reasonably to

preclude the idea of deliberate design. It was not the narra-

SUPREME COURT 15

Appeal from Fairfield County

tion of a past occurrence, but it was a part of the thing itself

while it was in the period of formation and being.

Under the head of statements by an accused. Prof. Wig-

more, in his work on Evidence, paragraph 1732, vol. 3, 2nd

edition, says:

“ Statements by an accused person may involve instances 49

of almost every one of the preceding sorts, but it is convenient

to consider them in one place, in order that the necessary dis

criminations may be made.

“ In the first place, any and every statement by an accused

person, so far as not excluded by the doctrine of confessions

or by the privilege against self crimination, is usable against

him as an admission. Thus, it is unnecessary for the prose

cution to establish the propriety of such statements under the

present Exception because they would be in any case receivable 50

as admissions. For this reason, since a person’s own state

ments are not receivable in his favor as admissions, there has

been a strong judicial tendency to ignore the bearings of the

present Exception for statements offered in favor of the ac

cused. It is therefore proper to inquire how far the present

principles are after all available for such a purpose.

“ (1) Statements of design or plan, as already noticed, are

in general admissible so far as the design or plan is relevant to

show the doing of the act designed. Accordingly, it has never

been doubted that the threats of an accused person are ad

missible to show his doing of the deed threatened, so also the

threats of the deceased, on a charge of homicide, are by most

Courts admitted to show the deceased to have been the ag

gressor. Upon the same principle, the expressions of plan,

by the accused, not to do the thing charged, or to do a different

thing, are equally admissible.

“ (2) Statements before the act, asserting malice or hatred,

are always received against an accused, except so far as the

time of feeling is so remote as to make it irrelevant- Is there 52

any reason why prior statements in favor of the accused,

for example, of good feeling toward the injured, or of fear

or him as an aggressor, should not be equally admissible ? Con-

16 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

duct offered as circumstantially evidential does not seem to be

objected to. But statements asserting directly the existence of

such feelings are by some Courts treated as inadmissible, so

far as they do not accompany the very act charged.

53 “ It has been argued that the party must not be allowed to

make evidence for himself.’ But this objection applies equally to

many classes of statements under the present Exception, and

is yet not thought of as fatal. Moreover, the notion of ‘making,’

that is, ‘manufacturing’ evidence, assumes that the statements,

are false, which is to beg the whole question.

“ Then it is further suggested that at any rate the accused,

if guilty, may have falsely uttered these sentiments in order

to furnish in advance evidence to exonerate him from a con

templated crime. But here the singular fallacy is committed

54 of taking the possible trickery of guilty persons as -a ground

for excluding evidence in favor of a person not yet proved

guilty; in other words, the fundamental idea of the presumption

of innocence is repudiated. We elaborate this presumption in

painful and quibbling detail; we expend upon it pages of

judicial rhetoric; we further maintain, with sentimental ex

cess, the privilege against self-crimination; in short, we ex

haust the resources of reasoning and strain the principles of

common sense to protect an accused person against an assump-

55 tion of guilt until the proof is irresistible; and yet, at the

present point, we throw these fixed principles to the winds and

make this presumption of guilt in the most violent form.

Because (we say) this accused person might be guilty, and

therefore might have contrived these false utterances, there

fore we shall exclude them, although without this assumption

they indicate feelings wholly inconsistent with guilt, and al

though, if he is innocent, their exclusion is a cruel deprivation

of a most natural and effective sort of evidence. To hold

that every expression of hatred, malice and bravado is to be

56 received, while no expression of fear, goodwill, friendship, or

the like can be considered, is to exhibit ourselves the victims

of a narrow whimsicality, which might be expected in the

tribunal of a Jeffreys, going down from London to Taunton,

SUPREME COURT 17

Appeal from Fairfield County

with his list of intended victims already in his pocket, or on a

bench ‘condemning to order,’ as Zola said of Dreyfus’ military

judges. But it was not to be anticipated in a legal system

which makes so showy a parade of the presumption of inno

cence and the rights of the accused. This question begging

fallacy about ‘making evidence for himself’ runs through much

of the judicial treatment. There is no reason why a declaration

of an existing state ,of 'mind, if it would be admissible against

the accused, should not also be admissible in his favor, except

so far as the circumstances indicate plainly a motive to deceive.”

Our Court has always recognized that the mental attitude of

the parties in a homicide was relevant and competent, and

material on trial.

In the case of State vs. Smith, 12 Rich. 430, Justice John

stone : “ I have been accustomed to think that the circumstances

that surround a man always serve to throw light not only upon

his language (which is known in law in another forum, with

which I am more familiar than with this), but also upon his acts.

The words uttered, the acts done, the language written, speak

for themselves, and are the only subject for interpretation; but

they are read and interpreted in the light of the circumstances

which prompted them, and to which they always tacitly refer.

The same act done under different circumstances may have

a different meaning. If a man slays another in battle, he is a

hero and a patriot. If, while repelling a criminal and dan

gerous assault on his person or his house, it is a defensive

and rightful act. If it is done under that degree of provoca

tion which would work up the infirmities of a man, proper

social feelings, and of peaceable disposition, to the hasty

shedding of blood, it is manslaughter. The circumstances must

determine the intention and the case.

“ I do not mean the mere circle of facts immediately sur

rounding the parties at the moment of the fatal act, but the

facts more or less remote, according to the case, which may

reasonably be supposed to have been in the minds or contem

plation of the parties at that time; the facts to which their

conduct may be supposed to have tacitly referred the facts;

18 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

which may be reasonably intended to have prompted the

fatal act.”

Language and conduct of the defendant fifteen or twenty

minutes before the killing are competent to show his state

of mind.

State vs. Miller, 73 S. C. 277.

State vs. Trailkill, 73 S. C. 317.

State vs. Smalls, 73 S. C. 517.

Wharton Criminal Evidence, 8th edition, Sections 30-47.

People vs. Molyneux, 62 L. R. A. 193, note.

4 Elliot, on Evidence, Section 3029.

See also—

State vs. Bright, 89 S. C. 231.

62 “Under the plea of self-defense, the defendant had the

right to introduce any testimony which tended to show that

immediately before the fatal encounter, deceased was in a

vicious humor, not only towards the defendant himself, but

also towards others, for that tended to throw light upon the

question, ‘Who was at fault in bringing on the difficulty?’

Which was of vital importance. That is one reason for the

admission of evidence of uncommunicated threats against the

defendant (State vs. Pails, 43 S. C. 61), and of the general

behavior of the accused immediately before the difficulty in

63 such cases.”

State vs. Springfield, 86 S. C. 323.

Also see—

38 L. R. A., N. S., 1061, note.

“ Either the State or the defendant had the right to show

by words, acts or deeds the mental attitude of each other at

the time of the killing.” State vs. Lemacks, 98 S. C. 509.

“ But the circumstances properly throw light upon his mental

64 attitude in the matter, which is the gist of the crime of murder.”

State vs. Culbreath, 113 Southeastern 476.

See also—

State vs. Rowell, 75 S. C. 494.

SUPREME COURT 19

Appeal from Fairfield County

In the recent case of State vs. Gregory, 127 S. C. 97, the

Court held that the words, acts and deeds of the deceased

shortly before the homicide were competent to show the state

of mind of the accused at the time of the fatal encounter.

See also the recent case of State vs. Hill, 129 S. C. 169,

Justice Cothran wrote the opinion: “A similar question in

reference to the conduct of the defendant has recently been

considered by this court in the case of State vs. Gregory, in

which it is declared that the conduct, actions, and general

demeanor of the accused immediately before the killing is ad

missible to show that he was in a vicious humor, as bearing

upon the great issue in the case, his frame of mind at the time

of the homicide.

As To Res Gbsta®

The rule in admitting statements of participants in a dif

ficulty, or bystanders, whether the statement be self-serving

or otherwise, is closely related to the “mental condition” theory.

The general principle is based on experience that, under cer

tain external circumstances of physical shock, a stress of

nervous excitement may be produced which stills the reflective

faculties and removes their control, so that the utterance which

then occurs is a spontaneous and sincere response to the actual

sensations and perceptions already produced by the external

shock. Since this utterance is made under the immediate and

uncontrolled domination of the senses, and during the brief

period when considerations of self interest could not have

been brought fully to bear by reasoned reflection, the utterance

may be taken as particularly trustworthy (or, at least, as lack

ing the usual grounds of untrustworthiness), and thus as ex

pressing the real tenor of the speaker’s belief as to the facts

observed by him; and may, therefore, be received as testimony

to those facts. In the reception of this evidence, however,

there are certain legal principles which are uniformly ob

served: First. It follows that the death, absence, or other

unavailability of the declarant need never be shown— a proposi-

20 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

tion never disputed. Second. The statement must have been

made under circumstances calculated to give some special trust

worthiness to it, and thus to justify it from the ordinary test

of cross-examination on the stand. Third. There must be

some shock, startling enough to produce this nervous excite-

69 ment, and render the utterance spontaneous and unreflecting.

Fourth. The utterance must have been before there has been

time to contrive and misrepresent. It need not be strictly con

temporaneous with the exciting cause, although there can be

no definite and fixed limit of time; each case must depend upon

its own circumstances- The main element is that it is spon

taneous. Fifth. The utterance must relate to the circumstances

of the occurrence preceding it.

Wigmore on Evidence, Vol. Ill, 1923 Edition.

70 State vs. Belcher, 13 S. C. 459.

State vs. Talbert, 41 S. C. 526.

State vs. Arnold, 47 S. C. 9.

Gosa vs. Southern Ry. Co., 67,S. C. 347.

State vs. McDaniel, 68 S. C. 304.

State vs. Lindsay, 68 S. C. 276.

Williams vs. Southern Ry. Co., 68 S. C. 369.

Nelson vs. G. & N. R. Co., 68 S. C. 462.

State vs. Way, .76 S. C. 91.

71 And as stated in State vs. McDaniel, 68 S. C. 304, “ Ques

tions of this kind must be largely left to the sound discretion

of the trial judge, who is compelled to view all the circum

stances in reaching his conclusions, and this Court will not

review his ruling unless it clearly appears from the undis

puted circumstances in evidence that the testimony ought to

have been admitted.” See also State vs. Way, 76 S. C. 91, and

other cases. Discretion, however, means judicial discretion.

Hence, the question is, does it clearly appear from the undis

puted circumstances in evidence that the testimony ought to

72 have been admitted? The facts and circumstances in evidence

up to this particular point are undisputed, the information

received on the previous night, sending for G. E. Martin

early and before breakfast the next morning, the morning of

SUPREME COURT 21

Appeal from Fairfield County

the homicide, the return of the boys in the truck after the

girls, the refusal of defendant to admit them into his dwelling,

and requiring them to talk from a designated place, the leaving

of the boys in the truck, the apprehension of defendant, the

approach of G. E. Martin at that instant— it was a cry of

despair, an expression of great fear, a plea for help, an as

surance that they would be stopped from returning—to his

curtilage and to his dwelling, it clearly showed his mental

condition, his state of mind, and it was a part of the thing

itself, and should have been admitted under both grouhds.

These Exceptions should be sustained.

As to His H onor's R efusal to D irect a V erdict at th e

Close of th e W hole Case, and F a ilin g in T h a t to 74

Strik e M urder F rom th e I n d ictm en t .

Exception Eleven charges error on the part of His Honor

in refusing to direct a verdict of Not Guilty. It is submitted

that at the close of the whole case, the question of defendant’s

being guilty of anything or not guilty had become academic.

Only one inference then could be drawn from the testimony.

Yes, defendant fired the shot. He had prepared himself to,

but he prepared only after he learned that war had been de

clared—and that hell would be raised at his house, about his 75

children—and he fired only after the raising had been started,

and the battle line had been formed—to defend himself, his

children, and his castle, and he shot only in defense of him

self, his children, and his castle, and that was the only infer

ence that could have been drawn. He had brought himself

within every element of self defense, and of the defense of

his castle. It was not a jury question, but it was a law question.

Certainly, under the facts and circumstances of this case, a

verdict of not guilty should have been directed, but failing in

that, it is respectfully submitted that there was no testimony

justifying a submission to the jury of murder, the error of

which is taken in Exception Twelve.

22 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

As to th e C harge on M urder and M alice , and th e F ailure

of th e Judge to C harge th e L a w A pplicable .

Exceptions Thirteen, Fourteen, Fifteen, Sixteen and Seven

teen challenge the correctness of His Honor on his Charge, and

77 allege error on the part of His Honor in not charging the law

applicable thereto, and further, that he invaded the province

of the jury. And they will be discussed somewhat together.

If an intentional killing is proved and no more, the law

implies malice, and hence, in such event, a Judge could charge

the jury that, “ If it is in the killing itself, the malice, it makes

murder,” and be correct.

State vs. Jones, 29 S. C, 201.

State vs. Alexander, 30 S. C. 74.

State vs. Mason, 54 S. C. 240.

State vs. Ariel, 38 S. C. 221.

State vs. Henderson, 74 S. C. 477.

State vs. Jones, 74 S. C. 457.

State vs. Foster, 66 S. C. 469.

State vs. McDaniel, 68 S. C. 304.

State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C. 195.

State vs. Jones, 86 S. C. 17.

However, a Charge may be erroneous, although the propo

sitions of which it is composed may severally be conformable

79 to recognized authority, if in its scope and bearing in the case

it is likely to lead to a misconception of the law.

State vs. Coleman, 6 S. C. 185.

State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C. 194.

The rule is, thus stated in State vs. Hopkins, 16 S. C. 153:

“ There is no doubt whatever of the isolated proposition that the

law presumes malice from the mere fact of homicide, but there

are cases, as made by the proof, to which the rule is inapplica

ble. When all of the circumstances of the case are fully

80 proved, there is no room for presumption. The question be

comes one of fact for the jury, under the general principle that

he who affirms must prove, and that every man is presumed

innocent until the contrary appears. We cannot distinguish

SUPREME COURT 23

Appeal from Fairfield County

this case from that of State vs. Coleman, 6 S. C. 185.” See

also State vs. Ariel, 38 S. C. 221; State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C.

194.

So, when His Honor followed his illustration, and charged

the jury, “ So you see, expressed and implied malice afore

thought is the wicked heart, for the killing at least,” he prac- 81

tically told the jury that if there was in the killing itself, the

wicked heart, that the killing was murder. The charge was

erroneous because he gave to the jury a misconception of the

law. Practically the same words were condemned by this

Court in the case of State vs. Ferguson, 91 S. C. 235, where

Judge Gage said to a jury :

“And a malicious heart, Mr. Foreman and gentlemen, is a

heart that is full of sin; that is wrong with God and man.

Malice, the law books picture, is black. Artists have tried to 82

draw it—the picture of the human heart— and they picture the

malicious heart in black, and they picture a lawful heart in

white. You have got to judge of a man’s heart by what he

says and does, and by what you know of him, and what you

know of yourselves, and what you know of human passion and

human conduct.”

Justice Hydrick, in writing the opinion of the Court, said:

“ His Honor was likewise unfortunate in departing from the

approved and well understood legal definitions of malice. It

is well for the trial judge to point out to the jury the difference

between the popular and the legal meaning of the word. But a

man’s heart may be full of sin. It may be wrong with God

and man. It may be what some artists would depict as black.

Yet, unless it prompts ‘the willful or intentional doing of a

wrongful act, without just cause or excuse,’ it is not a legally

malicious heart.”

Hence, just to tell a jury what His Honor did in this case

about malice was highly prejudicial. By the chargp on mur

der, His Honor stripped and pruned the word malice to mean 84

a wicked heart. It was emphasized and made applicable to the

facts in the case- This is not the law. Wickedness is not

synonymous with malice. The charge can be searched, and

24 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

nowhere is there a correct definition of malice. All of the

cases in this State, from State vs. Doig, 2 Rich. 179, on

through to the latest case, hold that “ Malice is a term of art,

denoting wickedness, and excluding just cause or excuse,” or

similar definitions. The charge in this case cannot be likened

85 to the charge in State vs. Crosley, 88 S. C. 98; there the Judge

charged the jury that a malicious heart was a wicked heart—

“ it means a heart devoid of social duty and fatally bent on

mischief— a wilful and intentional doing of a wrongful act by

one knowing the act to be against the law, and by one doing it

wilfully.”

And under no circumstances can one be convicted of mur

der just by showing an intentional killing, even though the

heart was wicked in the killing. The State must go further

86 and prove malice, the same as any other material element in

a charge of murder.

State vs. Coleman, 6 S. C. 186.

State vs. Hopkins, 15 S. C. 157.

State vs. Jones, 29 S. C. 201.

State vs. Ariel, 38 S. C. 221.

State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C. 194.

Hence, where a judge does not charge the law applicable

to the facts and circumstances, it is reversible error.

87 State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C. 194.

When the charge is considered in its entirety, it will be seen

that these errors were not corrected, as was the case in State

vs. Wilson, 115 S. C. 248, and similar cases.

As to Exception Sixteen, the uncontradicted testimony in

the case was that on Monday morning, after the visit of Robt.

Duffey on Sunday night, Jim Davis sent to Manuel Suber’s

and borrowed a shotgun and a loaded shell, that he already had

a shotgun in his house, and that Robt. Dodson, when he came

88 over to appellant’s residence, brought his pistol with him. The

defendant freely admitted that he did so borrow the gun and the

ammunition, and stated that when he did he borrowed it to

protect himself, his family, and his castle from the anticipated

SUPREME COURT 25

Appeal from Fairfield County

attack of these boys and Mr. Scott. The solicitor replied to

him, “ Then you had a regular ‘strong place’ over there.”

When the Judge came to charge the jury, he told them this:

“ Buying ammunition would express his malice; going for a

gun would express his malice.” Matter of fact, this was the 89

sole reason that His Honor gave in not directing a verdict of

not guilty at the close of the whole case, “ he had made this

preparation.” Now, under some facts and circumstances, per

haps, buying ammunition or going for a gun would express

malice, but, certainly no malice would be expressed where one

bought ammunition or where one went for a gun to defend

himself, his family, and his castle. But here was a direct

statement of the Judge as to what would express his malice—the

Judge telling the jury just what would express the defendant’s

malice— and this is the very thing which is condemned by 1895 90

Constitution, Art. V, Section 29, wherein it is provided: “Judges

shall not charge juries in respect to matters of fact, but shall

declare the law.”

So great is the weight which a jury attaches to an intima

tion of opinion coming from one set apart to preside over the

Court, because of his impartiality and capacity to decide justly,

that the duty is ever present to a judge to guard against any

expression, either in questions, remarks, or in his charge, that

may so influence the jury as to make the Judge a participant 91

in their findings of fact. This duty is imposed by the Con

stitution, and a departure from it tending to affect the decision

by the jury of a material issue of fact must result in a new

trial.

Willis vs. Telegraph Co., 73 S. C. 379.

Latimer vs. Electric Co., 81 S. C. 374.

State vs. Driggers, 84 S. C. 526.

State vs. Jackson, 87 S. C. 407.

State vs. Eeberee, 95 S. E. 333.

State vs. Smalls, 82 S. C. 421. 92

State vs. Turner, 117 S. C. 470.

State vs. Barfield, 122 S. E. 856.

26 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

The verdict was inevitable, defenses or what not, when the

Judge told the jury that “ buying ammunition and going for a

gun would express his malice”—and the defendant had done

just this. He thus made himself a participant with the jury in

their findings of fact, here was malice— under the Judge’s in

structions— and, therefore, he was guilty of murder. This

Exception should be sustained.

I have tried to cover the Seventeenth Exception in my dis

cussion of Exception Thirteen, Fourteen and Fifteen.

As to E rrors in C h arging on A ppearances

The errors charged are covered in Exceptions Eighteen,

Nineteen and Twenty, and they will all be grouped and dis

cussed together.

The law imposes on a defendant the burden of proving, not

that the necessity did in fact exist, but that the circumstances

were such as to warrant a man or ordinary reason and courage

in concluding that it did exist, and that the defendant himself

did in fact so believe.

The defendant had the right to act upon appearances, and if

they were such that a man of ordinary prudence and courage

would have been justified in coming to the conclusion that the

necessity did exist, that was sufficient, although it afterwards

turned out that it did not in fact exist, hence, the defendant

could not be required to prove the necessity did in fact exist, but

only that it appeared to exist; neither could he be required

to prove than “ any other man” would have been justified

in believing, but only that a man of ordinary prudence and

courage.

State vs. Gandy, 101 S. E. 644-

And if he brought himself otherwise within the ordinary

element of self defense, the killing would not be reduced from

murder to manslaughter; but, in such event, the defendant

would be entitled to a verdict of Not Guilty.

SUPREME COURT 27

Appeal from Fairfield County

E xceptions C h arging E rrors on th e P art of H is H onor

in C h arging th e L a w of Self D efense .

The errors charged are grouped in Exceptions Twenty-one,

Twenty-two, Twenty-three, Twenty-four, Twenty-five and

Twenty-six, and they will be discussed for the most part to- 97

gethfer.

It is well established that in the exercise of the right of

self defense by an occupant of premises, using the word in the

most comprehensive sense, in relation to his right to defend not

only his own person, but anyone else whom he may have the

legal right to defend, whether in the castle or dwelling house,

the curtilage, other parts of his premises, his place of business,

or place to which he has the right of legal resort by reason of

membership in some organization in possession thereof, if 9g

assaulted by another who has become objectionable or is tres

passing or seeking an unlawful entry therein, in such manner

as to endanger life or threaten serious bodily injury, is not

bound to retreat, but may stand his ground and meet such force

even to the extent of killing his assailant, if he brings himself

within the ordinary rules of self defense applicable to such

a case.

Bishop’s New Cr. Law (8th edition) Sec. 858.

Clark’s Cr. Law (2nd edition) p. 171.

State vs. Nance, 25 S. C. 168. 99

State vs. Bodie, 33 S. C. 117.

State vs. Trammel, 40 S. C. 331..

State vs. Corley, 43 S. C. 205.

State vs. Brooks, 79 S. C. 144.

State vs. Stevenson, 85 S. C. 247.

State vs. Ellison, 95 S. C. 127.

State vs. Gibbs, 113 S. C. 256.

State z’s. Bowers, 115 S. E. 303.

Neither is such occupant to be charged with legal fault in 100

bringing about the fatal difficulty so as to deprive himself of

the right of self defense because of the use in the first instance

of a reasonable and necessary amount of physical force in

28 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

attempting to prevent an unlawful entry or to effect a lawful

ejectment. It is, therefore, only necessary for the occupant

under such circumstances to show that, at the time of the kill

ing, he entertained an actual bona fide belief that he, or some

one who he had the legal right to defend, was in imminent

danger of loss of life, or sustaining a serious bodily injury, and

that the danger, either real or apparent, was such as to warrant

a similar conclusion by a man of ordinary judgment, reason

and firmness, in order to render the plea of self defense avail

able. And standing on his right to eject or to prevent an

intrusion, in his plea of self defense, where one is seeking an

unlawful entry into his dwelling house, he may use greater

force than on other parts of his premises. This Court recog

nized this distinction in the case of State vs. Lightsey, 43 S. C.

102 116, when it said : “ Out on the lands, away from the castle, he

(the occupant) has not the same right there that he has in his

home.”

The uncontradicted testimony and the only testimony in the

case showed that the defendant was in his own home, and had

done nothing whatever to provoke the difficulty, that he was

without legal fault; he did not have to retreat, yet His Honor

charged the jury these two elements, and in them he made

errors as will be pointed out; certainly, the only thing he had

to establish by the preponderance of the testimony at this time,

on this defense, was that he entertained an actual, bona fide

belief that he was in danger of suffering serious bodily in

jury, or someone who he had the legal right to defend, and that

a man of ordinary reason and firmness would have been war

ranted in reaching a similar belief.

State vs. Me Greer. 13 S. C. 464.

State vs. Jones, 29 S. C. 236.

State vs. Jackson, 32 S. C. 44.

State vs. Wyse, 33 S. C. 595.

104 State vs. Littlejohn, 33 S. C. 600.

State vs. McGraw, 35 S. C. 290.

State vs. Bowers, 65 S. C. 214.

State vs. Hutto, 66 S. C. 452.

SUPREME COURT 29

Appeal from Fairfield County

State vs. Foster, 66 S. C. 473.

State vs. Thompson, 68 S. C. 137.

State vs. Miller, 73 S. C. 278.

State vs. Thompson, 76 S. C. 124.

State vs. Stockman, 82 S. C. 400.

State vs. Watson, 94 S. C. 461. 105

State vs. Bethune, 99 S. E. 753.

State vs. Heron, 108 S. E. 93.

State vs. Green, 110 S. E. 145.

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240, and a list of other cases

too numerous to cite, together with those cited above in this

section of the argument.

It is the belief of the defendant; and the belief of the man

of ordinary reason and firmness. Yet the Judge charged the

jury in this case that having shown that he was without 106

fault in bringing on the difficulty, that “he has to show that at

the time of the shooting or killing, that at that time he was

in danger of losing his life or suffering serious bodily harm

from his antagonist”— a burden altogether too severe, and one

not required by law. Moreover, and in the same connection, he

charged them, “ and in order to save his life, or his body from

serious harm, at that time, there was nothing else for him to do

except to shoot or strike to save his life or his body from

serious harm,” another burden, altogether too heavy, and not 1Q7

required by law; moreover, he charged them in the same con

nection, “ then, he has got to establish, moreover, not only that

he believed that he was in danger of losing his life or receiving

serious bodily harm at the time, but that any other man situated

as he was at the time would have been justified.” Here the Court

will see, where any other man was emphasized, this is not the

test.

And then, again, in charging on appearances in reference

to self defense, as charged in Exception Twenty-four, any other

man is again emphasized. But, moreover, His Honor charged 108

them, “ he has got to establish that by the preponderance of the

evidence, and make it complete and full and give it all to you.”

And this is Exception Twenty-five. In State vs. Lindsay et al.,

30 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

82 S. C. 488, Judge Klugh told a jury in a murder case, in

speaking of self defense, that the law on that issue is “strict

and rigid,” and that the affirmative of that issue must be

clearly established.” This Court held that the same was preju

dicial error and placed upon the defendant a greater burden

109 than that required by law. Here is the language of Judge

W oods; “ In view of the sharp issue of veracity between the

witnesses on the question of self defense, we cannot escape the

conviction that it was prejudicial to the defendant to single out

the issue of self defense, and say to the jury the law on that

issue is “strict and rigid,” and that the affirmative of that issue

must be “ clearly established.” It is true the judge said in the

same connection that the plea must be established by the pre

ponderance or greater weight of the evidence, but, when the

instructions are considered together, they can have no other

meaning than that the law is strict and rigid in requiring the

plea of self defense to be clearly established by the preponder

ance of the evidence. The law is that one who kills another

is excused if he establishes the plea of self defense by the pre

ponderance of the evidence- While it is the duty of the Courts

and juries to be resolute in rejecting the plea when not sup

ported by a preponderance of the evidence, the Court is not

at liberty to single out this plea as one which the law strictly

and rigidly requires to be clearly established by the prepon-

111 derance of the proof. In Sanders vs. Aiken Mfg. Co., 71 S. C.

58, the instruction was: “ Contributory negligence on the part

of the plaintiff in order to absolve the defendant from liability

must be ‘clear and convincing.’ In holding this to be error, the

Court said, ‘that such proof should be clear and convincing,

and indeed, leave no room for any other inference to justify

the Court from taking the case from the jury, there can be

no doubt. Doolittle vs. Ry. Co., 62 S. C. 130. But there is no

room for a jury to require or seek proof more clear and con

vincing as to this defense than any other in which the burden

112 is on the defendant. The rule is that he must establish con

tributory negligence by the preponderance of the evidence. It

is highly desirable that evidence on all issues should be clear and

convincing, but it tends to the prejudice of a party for the Court

SUPREME COURT 3 i

Appeal from Fairfield County

to single out an issue as to which the burden of proof is on him,

and instruct the jury that ‘he must prove his contention by

evidence clear and convincing.’ The point is not free from

difficulty; but, after a careful examination of the whole record,

we cannot feel satisfied that the instruction did not overstate

the burden imposed on the defendants in making out the plea 113

of self defense, and was prejudicial.”

It is true that in our case, like it was in the Lindsay case,

the Judge told the jury that the defendant had to establish that

by the preponderance of the evidence, but taking these in

structions together, he said, practically, that while the law

required him to establish it by the preponderance of the evi

dence, yet he had to make it complete and, full, and-give it all

to the jury. The rule in this State is not the rule that Portia

gave to Shylock: 114

“ Therefore, prepare thee to cut off the flesh.

Shed thou no blood; nor cut thou less nor more

But just a pound of flesh; if thou cut’st more

Or less than a just pound, be it so much

As makes it light or heavy in the substance,

Or the division of the twentieth part

Of one poor scruple, nay, if the scale do turn

But in the estimation of a hair,

Thou diest, and all thy goods are confiscate.”

115

If the evidence preponderates, “ if the scale do turn but in

the estimation of a hair,” then the defendant is not guilty.

Complete means perfection—full means having all that can be,

the highest state, point, or degree— all means the whole, every

thing.

And then, Exception Twenty-six alleging error in the charge

in reference to self defense: “ He has got to establish another

thing, this is the last one, ordinarily, he has got to establish

that there was no reasonably safe means of avoiding the dif

ficulty in defense of his life or loss of limb, he could not get out 116

of it, he had it to do, that the necessity was upon him to kill

to save his life or his body from serious harm. Now, these

four things have got to appear before he can establish his self

32 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

defense.” A man is not justified in taking human life, even in

defense of his home, after the danger has passed. State vs.

Stockman, 82 S. C. 486. But if the danger of making a forci

ble entry or the necessity to present an unlawful intrusion or

invasion is imminent, one may then strike, using such degree

of force as may be reasonably necessary under the facts and

circumstances, and if death results, the homicide is excusable.

State vs. Rochester, 72 S. C. 199.

State vs. Brooks, 79 S. C. 149.

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240.

State vs. Gordon, 122 S. E. 502.

The danger of death or serious bodily harm must appear

imminent—and ordinarily it is a man’s duty to avoid taking

118 life where it is possible to prevent it, even to the extent of

fleeing. State vs. Rowell, 75 S. C. 510. It is said that one of

the “ foundation rocks upon which the plea of self defense is

bottomed is that it was necessary for the accused to take the

life of his fellow man to protect his own, or to protect himself

from serious bodily harm.” State vs. McIntosh, 40 S. C. 349.

And if he has any probable means of escape than that of taking

the life of his fellow man, he is bound to adopt that means.

State vs. Corley, 43 S. C. 127; State vs. Summer, 55 S. C. 32.

The law requires, under all circumstances, that a man retreat

119 before taking the life of his assailant, unless he be in his dwell

ing, or on the curtilage, or on his premises, and he must adopt

the reasonable or probable means of escape. State vs. Foster,

66 S. C. 469. But he is never required to show that “ he could

not get out of it, he had it to do.” In his dwelling house he

may stand his ground, he may go forward. Under no cir

cumstances, one accused of homicide need not satisfy the jury

that he had no other way of escape except to kill, but only that

no other way of escape would have appeared to a man of

12q ordinary prudence and firmness.

State vs. Thomas, 103 S. C. 321.

State vs. Jordan et al., 96 S. E. 221.

SUPREME COURT 33

Appeal from Fairfield County

A s to th e C harge on th e L a w of t h e Castle

Complaint is made of the charge on the law of the castle,

beginning with Exception Twenty-seven and going through

Exception Thirty-two, inclusive-

A man who attempts to force himself into another’s dwell- 121

ing, or who being in the dwelling by invitation or license, re

fuses to leave when the owner makes that demand, is a tres

passer, and the law permits the owner to use as much force,

even to the taking of his life, as may be reasonably necessary

to prevent the obtrusion or to accomplish the expulsion. In

ancient days habitations were necessarily converted into strong

holds of defense, and the dwelling became a castle. The law

crystallized the familiar principles: "While the man keeps

the door of his house closed, no other party may unlawfully

break and enter it.” “ The persons within the house may 122

exercise all needed force to keep aggressors out, even to the

extent of taking life.” Bishop’s New Cr. Law, 8th Edition,

paragraph 858. The dwelling house of a man is his castle, and

he may not only defend the same, if necessary or apparently so,

against one who manifestly endeavors to enter the same in a

wanton, riotous, or violent manner, or with intent to commit

a felony on him or some inmate of his household or guest, or

the habitation itself, but also against one who is only attempt

ing to commit the misdemeanor of a forcible entry, even to the 123

extent of killing the assailant, if such degree of force be reason

ably necessary to accomplish the purpose of preventing a forci

ble entry against his will.

State vs. Brooks, 79 S. C. 144.

State vs. Gibbs, 113 S. C. 256.

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240.

State vs. DuPre, advanced sheets.

The occupant may, however, waive the protection of the

castle, and allow one to enter therein by express or implied 124

license or invitation. Such a person cannot lawfully be ejected

by the use of violence until he has been requested to depart,

and if he refuse to heed the request the hands must be laid

34 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

on gently, and thereafter only so much force may be used as is

necessary to accomplish the ejectment.

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240.

But no man has the right, as the Court well says, in the

125 case ° f State vs. McIntosh, 40 S. C. 361, to kill an invited guest

without any notice to leave, and one so killing does not occupy

the position of one who slays in defense of the castle, and for

similar reasons, excessive force, or a needless battery, resulting

in the death of one employed in the ejectment of such person

from the dwelling house cannot be excused.

Bishop’s New Cr. L., 8th edition, paragraph 895.

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240.

State vs. McIntosh, 40 S. C. 361.

126 Even though one should enter the habitation of another

without his consent or permission, or against his positive ob

jection, and thereby assume the status of an intruder or tres

passer, yet, if he came peaceably and is not misbehaving, he

should first be ordered away, and thereafter there is no practi

cal distinction between the rights of the occupant in effecting

his ejectment and the case of a licensee. It has been held

where one, although forbidden to enter, went in peaceably,

the occupant had no right to kill him upon a failure to in

stantly obey an order to leave, and that such an act was murder.

People vs. Horton, 4 Mich. 67.

O f course, if the entry itself is made in a reckless, riotous,

or violent manner, or is effected by overcoming the physical

or verbal opposition of the occupant, or is made under such

circumstances as to manifestly evidence a purpose to endanger

the life or limb of any inmate, or to commit a felony on

them, the habitation or property therein, in other words, is not

quiet and peaceable, no request to depart, or the laying on of

hands, need precede, as a legal requirement, the act of ejectment

128 by such force as is necessary, even to the killing of the assailant,

for the very obvious reason, as is well said in one of the cases,

“ Since the trespasser knows, as well without express words

as with, that his absence is desired.”

SUPREME COURT 35

Appeal from Fairfield County

The foregoing principles apply to the rights of the occupant

in the protection of his habitation, apart from the right of self

defense, which obviously may also, under such circumstances,

be asserted. They manifestly do not apply except in relation

to the habitation. “ In such a case, the occupant is not re-

1 nQ

quired to retreat, but may press forward, availing himself,

in addition to every legal right of self defense which one would

have on other parts of the premises, of the right also to put the

objectionable one out of the house, and to use as much force

as is necessary for the purpose, even.to the extent of taking his

life.”

State vs. Bradley, 120 S. E. 240.

Thus, it will be seen, in this admirable opinion by Justice

Cothran, that there is a difference between one who enters as

an invited guest, or by either implied or express license, and by

one who enters as an intruder or trespasser; and the law au

thorizes each to be treated differently, in no event do they stand

on equal or on the same grounds. The very acts, conduct and

language of Mr. Scott showed that he did not go either by in

vitation, or by express or implied license. On the contrary,

he sent for the girls, and their father refused to permit them

to go. Immediately he armed himself with a 38 Special pistol,

and was armed so satisfactorily to himself that he stated, “ this

is enough to bring two or three back with,” meaning the 131

daughters of defendant, who were in their father’s dwelling

house, and he started to the home of defendant for these chil

dren. Upon being informed by D. R. Martin, the landlord of

the defendant, that “ Old Jim has sent for me, he says he is

having trouble about his girls going, and I am going over there,”

the deceased remarked, “ I will go over there and get them,”

and started his truck off, leaving D. R. Martin, the landlord,

to walk, following the truck. Moreover, Mr. Scott knew full

well that Jim Davis would not permit these boys to go into

his house again. And yet, under such circumstances, the Judge 132

charged the jury that the question whether or not Scott was

a licensee in going into this man’s yard and house under such

circumstances was for them. How could it have been? What

36 SUPREME COURT

The State vs. Jim Davis

had Jim Davis done or said to give to Mr. Scott the right to

go? No invitation had been extended to him, no express

license to go had been given him by Jim Davis; and Jim Davis

had said nothing and had done nothing from which any man of

133 o r d i n a r y courtesy and intelligence could have even inferred

that he had an implied license to go, under the facts and cir

cumstances as were presented to Austin Scott. On the con

trary, every act and every word of Jim Davis had convinced

Austin Scott, before even he started, that his presence was not

wanted, and that his absence was desired. And no man is a

licensee who goes into another’s home, without either express

or implied permission or invitation, until he is given notice to

get out. And, yet, this is just what the Judge charged: “ Now,

if he is resisting, that applies to anybody who comes in and is

1 34 given notice to get out, because he is a licensee up to the time

if he has no notice that he is objectionable.” And then followed

a most prejudicial statement by the Judge: “ We couldn’t trans

act business unless that was so, so you see that, because it is

common sense. We couldn’t walk to the house of our friends

if that wasn’t so— with our hands on the trigger, that wouldn’t

do. . . . He has implied consent to unless he has some

notice to come and go.” But where you go to the house of a

man on a truck, with two who have just been denied admission,

heavily armed— for the purpose of taking the children of the

occupant out—no man has “ implied consent to come and go

unless he has some notice,”— but deceased here had every

notice, and there was no element of license in this case, under

any phase of the testimony, and the same should have never