Appendix

Public Court Documents

June 12, 1973

250 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Appendix, 1973. ae310102-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2b316ade-abe7-4909-8fbe-b42bfa32f11f/appendix. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

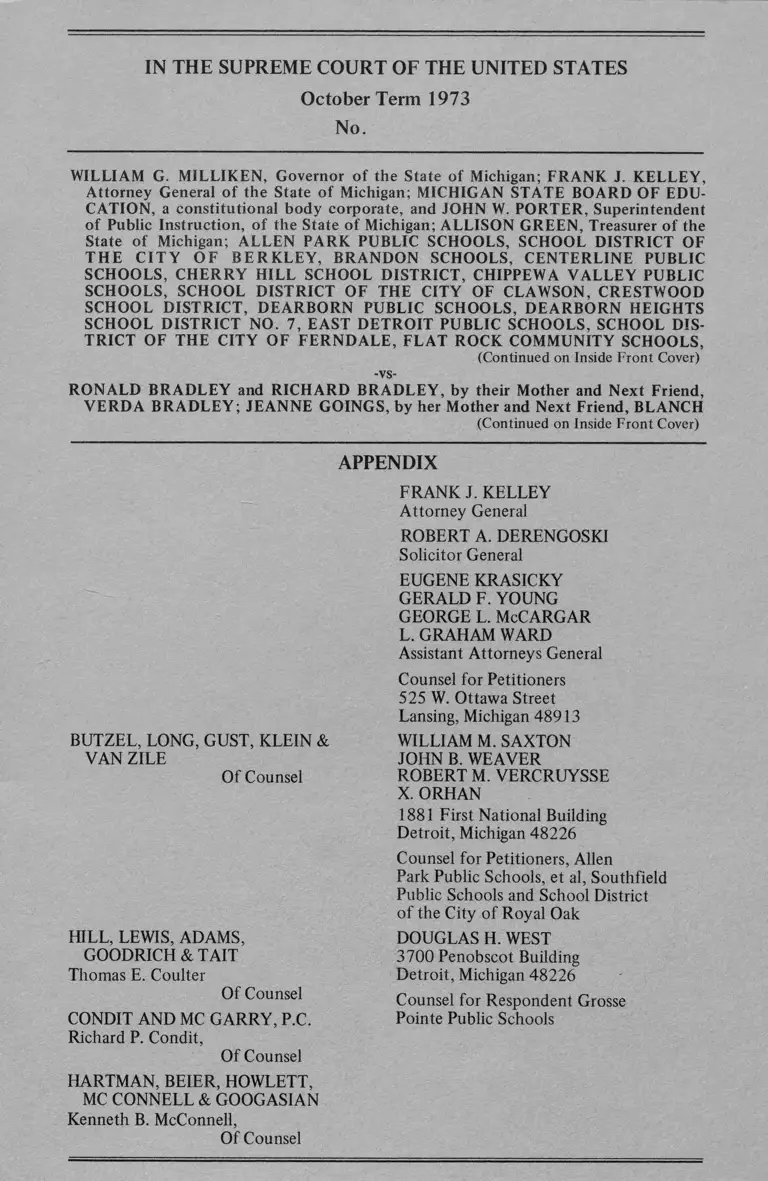

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1973

No.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor of the State of Michigan; FRANK J. KELLEY,

Attorney General o f the State o f Michigan; MICHIGAN STATE BOARD OF EDU

CATION, a constitutional body corporate, and JOHN W. PORTER, Superintendent

of Public Instruction, of the State of Michigan; ALLISON GREEN, Treasurer of the

State of Michigan; ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

THE CITY OF BERKLEY, BRANDON SCHOOLS, CENTERLINE PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, CHERRY HILL SCHOOL DISTRICT, CHIPPEWA VALLEY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF CLAWSON, CRESTWOOD

SCHOOL DISTRICT, DEARBORN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, DEARBORN HEIGHTS

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 7, EAST DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DIS

TRICT OF THE CITY OF FERNDALE, FLAT ROCK COMMUNITY SCHOOLS,

(Continued on Inside Front Cover)

-vs-

RONALD BRADLEY and RICHARD BRADLEY, by their Mother and Next Friend,

VERDA BRADLEY; JEANNE GOINGS, by her Mother and Next Friend, BLANCH

(Continued on Inside Front Cover)

APPENDIX

BUTZEL, LONG, GUST, KLEIN &

VAN ZILE

Of Counsel

HILL, LEWIS, ADAMS,

GOODRICH & TAIT

Thomas E. Coulter

Of Counsel

CONDIT AND MC GARRY, P.C.

Richard P. Condit,

Of Counsel

HARTMAN, BEIER, HOWLETT,

MC CONNELL & GOOGASIAN

Kenneth B. McConnell,

Of Counsel

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

ROBERT A. DERENGOSKI

Solicitor General

EUGENE KRASICKY

GERALD F. YOUNG

GEORGE L. McCARGAR

L. GRAHAM WARD

Assistant Attorneys General

Counsel for Petitioners

525 W. Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

WILLIAM M. SAXTON

JOHN B. WEAVER

ROBERT M. VERCRUYSSE

X. ORHAN

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Counsel for Petitioners, Allen

Park Public Schools, et al, Southfield

Public Schools and School District

of the City of Royal Oak

DOUGLAS H. WEST

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Counsel for Respondent Grosse

Pointe Public Schools

GARDEN CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, GIBRALTAR SCHOOL DISTRICT, SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF HARPER WOODS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF HAZEL PARK, INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE COUN

TY OF MACOMB, LAKE SHORE PUBLIC SCHOOLS, LAKEVIEW PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, THE LAMPHERE SCHOOLS, LINCOLN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

MADISON DISTRICT PUBLIC SCHOOLS, MELVINDALE-NORTH ALLEN PARK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF NORTH DEARBORN HEIGHTS,

NOVI COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, OAK PARK SCHOOL DISTRICT, OX

FORD AREA COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, REDFORD UNION SCHOOL DISTRICT

NO. 1, RICHMOND COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY

OF RIVER ROUGE, RIVERVIEW COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ROSE

VILLE PUBLIC SCHOOLS, SOUTH LAKE SCHOOLS, TAYLOR SCHOOL DIS

T R IC T , WARREN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOLS, WARREN WOODS PUBLIC

SC H O O LS, W AYN E-W ESTLA N D COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, WOODHAVEN

SCHOOL DISTRICT, and WYANDOTTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS; GROSSE POINTE

PUBLIC SCHOOLS; SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS; and SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE CITY OF ROYAL OAK,

Petitioners,

GOINGS: BEVERLY LOVE, JIMMY LOVE and DARRELL LOVE, by their

Mother and Next Friend, CLARISSA LOVE: CAMILLE BURDEN, PIERRE BUR

DEN, AVA BURDEN, MYRA BURDEN, MARC BURDEN and STEVEN BURDEN,

by their Father and Next Friend, MARCUS BURDEN: KAREN WILLIAMS and

KRISTY WILLIAMS, by their Father and Next Friend, C. WILLIAMS; RAY LITT

and MRS. WILBUR BLAKE, parents; all parents having children attending the pub

lic schools of the City of Detroit, Michigan, on their own behalf and on behalf of

their minor children, all on behalf of any person similarly situated; and NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, DETROIT

BRANCH; BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF DETROIT, a school dis

trict of the first class; PATRICK McDONALD, JAMES HATHAWAY and CORNEL

IUS GOLIGHTLY, members of the Board of Education of the City of Detroit; and

NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools; DETROIT

FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS, AFL-CIO; DENISE MAGDOWSKI and DAVID MAGDOWSKI, by

their Mother and Next Friend, JOYCE MAGDOWSKI; DAVID VIETTI, by his

Mother and Next Friend, VIOLET VIETTI, and the CITIZENS COMMITTEE FOR

BETTER EDUCATION OF THE DETROIT METROPOLITAN AREA, a Michigan

non-profit Corporation; KERRY GREEN and COLLEEN GREEN, by their Father

and Next Friend, DONALD G. GREEN, JAMES, JACK and KATHLEEN ROSE

MARY, by their Mother and Next Friend, EVELYN G. ROSEMARY, TERRI

DORAN, by her Mother and Next Friend, BEVERLY DORAN, SHERRILL,

KEITH, JEFFREY and GREGORY COULS, by their Mother and Next Friend,

SHARON COULS, EDWARD and MICHAEL ROMESBURG, by their Father and

Next Friend, EDWARD M. ROMESBURG, JR., TRACEY and GREGORY AR-

LEDGE, by their Mother and Next Friend, AILEEN ARLEDGE, SHERYL and

RUSSELL PAUL, by their Mother and Next Friend, MARY LOU PAUL, TRACY

QUIGLEY, by her Mother and Next Friend, JANICE QUIGLEY, IAN, STEPHANIE

KARL and JAAKO SUNI, by their Mother and Next Friend, SHIRLEY SUNI, and

TRI-COUNTY CITIZENS FOR INTERVENTION IN FEDERAL SCHOOL ACTION

NO. 35257; MICHIGAN EDUCATION ASSOCIATION; and PROFESSIONAL PER

SONNEL OF VAN DYKE,

Respondents.

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Complaint ............................................................................

Ruling on Issue of Segregation, dated September 27, 1971

October 4, 1971, proceedings ............................................

November 5, 1971, Order ................................................

Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan

Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public

Schools of the City of Detroit, March 24, 1972 ............

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-Only

Plans of Desegregation, March 28, 1972 ..........................

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of

Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development of

Plans, June 14, 1972 ......................................................

Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Development

of Plan of Desegregation, June 14, 1972 .......................

Order for Acquisition of Transportation, July 1 1, 1972 . .

Order, United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit .............................................................................

Opinion, June 12, 1973 ......................................................

Notice of Judgment, June 12, 1973 ...........................

Excerpt from June 24, 1971 Proceedings .........................

Judgment, June 12, 1973 ..................................................

17a

40a

46a

48a

53a

59a

97a

106a

108a

110a

241a

242a

244a

2a

la

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY and RICHARD )

BRADLEY, by their Mother and Next )

Friend, VERDA BRADLEY; JEANNE GO- )

INGS, by her Mother and Next Friend, )

BLANCHE GOINGS; BEVERLY LOVE, )

JIMMY LOVE and DARRELL LOVE, by )

their Mother and Next Friend, CLARISSA )

LOVE; CAMILLE BURDEN, PIERRE )

BURDEN, AVA BURDEN, MYRA BUR- )

DEN, MARC BURDEN and STEVEN )

BURDEN, by their Father and Next )

Friend, MARCUS BURDEN; KAREN )

WILLIAMS AND KRISTY WILLIAMS, by )

their Father and Next Friend, C. WIL- )

LIAMS; RAY LITT and Mrs. WILBUR )

BLAKE, parents; all parents having chil- )

dren attending the public schools of the )

City of Detroit, Michigan, on their own be- )

half and on behalf of their minor children, )

all on behalf of any persons similarly situ- )

ated; and NATIONAL ASSOCIATION )

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLOR- )

ED PEOPLE, DETROIT BRANCH, )

Plaintiffs, ) CIVIL ACTION

vs. ) NO. 35257

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, Governor of the )

State of Michigan and ex-officio member of )

Michigan State Board of Education; )

FRANK J. KELLEY, Attorney General of )

the State of Michigan; MICHIGAN STATE )

BOARD OF EDUCATION, a constitutional )

body corporate; JOHN W. PORTER, Act- )

ing Superintendent of Public Instruction, )

Department of Education and ex-officio )

Chairman of Michigan State Board of Edu- )

cation; BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE )

CITY OF DETROIT, a school district of )

2a

th e first class; PATRICK McDONALD, )

JAM ES HATHAWAY and CORNELIUS )

GOLIGHTLY, members o f the Board o f )

E ducation o f the City o f Detroit; and )

NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent o f )

the Detroit Public Schools, )

Defendants.

C O M P L A I N T

I.

The jurisdication of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

Sections 1331(a), 1343(3) and (4), this being a suit in equity

authorized by 42 U.S.C. Sections 1983, 1988 and 2000d, to re

dress the deprivation under color of Michigan law, statute, custom

and/or usage of rights, privileges and immunities guaranteed by the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States. This action is also authorized by 42 U.S.C. Sec

tion 1981 which provides that all persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the same rights to the full and

equal benefits of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens. Jurisdiction is

further invoked under 28 U.S.C. Sections 2201 and 2202, this be

ing a suit for declaratory judgment declaring certain portions of

Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of 1970 (a copy of which

is attached hereto as Exhibit A) unconstitutional. This is also an

action for injunctive relief against the enforcement of certain por

tions of said Act No. 48 and to require the operation of the

Detroit, Michigan public schools on a unitary basis.

II.

Plaintiffs, Ronald Bradley and Richard Bradley, by their

Mother and Next Friend, Verda Bradley; Jeanne Goings, by her

Mother and Next Friend, Blanche Goings; Beverly Love, Jimmy

Love and Darrell Love, by their Mother and Next Friend, Clarissa

Love; Camille Burden, Pierre Burden, Ava Burden, Myra Burden,

Marc Burden and Steven Burden, by their Father and Next Friend,

3a

Marcus Burden; Karen Williams and Kristy Williams, by their

Father and Next Friend, C. Williams; Ray Litt and Mrs. Wilbur

Blake, parents, are all parents or minor children thereof attending

schools in the Detroit, Michigan public school system. All of the

above-named plaintiffs are black except Ray Litt, who is white

and who joins with them to bring this action each in their own

behalf and on behalf of their minor children and all persons simi

larly situated.

P lain tiff, National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Detroit Branch, is an unincorporated association

with offices at 242 East Warren Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, which

sues on behalf of its membership who are members of the plaintiff

class. Plaintiff, N.A.A.C.P., has as one of its purposes the advance

ment of equal educational opportunities through the provision of

integrated student bodies, faculty and staff.

III.

Plaintiffs, pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, bring this action on their own behalf and on behalf of

all persons in the City of Detroit similarly situated. There are com

mon questions of law and fact affecting the rights of plaintiffs and

the rights of the members of the class. The members of the class

are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all be

fore the Court. A common declaratory and injunctive relief is

sought and plaintiffs adequately represent the interests of the

members of the class.

IV.

The defendants are:

1. William J. Milliken, Governor of the State of Michigan

and ex-officio member of the State Board of Education;

2. Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General of the State of

Michigan, who is responsible for enforcing the public acts and laws

of the State of Michigan;

4a

3. The Michigan State Board of Education, a constitutional

body corporate, which is generally charged with the power and re

sponsibility of administering the public school system in the State

of Michigan, including the City of Detroit;

4. John W. Porter, Acting Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion, Department of Education, in the State of Michigan, and ex-

officio member of the State Board of Education;

5. The Board of Education of the City of Detroit, a school

district of the first class, organized and existing in Wayne County,

Michigan, under and pursuant to the laws of the State of Michigan

and operating the public school system in the City of Detroit,

Michigan;

6. Patrick McDonald, James Hathaway and Cornelius

Golightly, all residents of Wayne County, Michigan, and elected

members of the Board of Education of the City of Detroit;

7. The remaining board members of the Board of Education

of the City of Detroit;

8. Norman Drachler, a resident of Wayne County, Michigan,

and the appointed Superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools.

V .

Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment declaring the last sen

tence of the first paragraph of Section 2a and the entirety of Sec

tion 12 of Public Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of 1970

unconstitutional.

The challenged portion of Section 2a reads as follows:

Regions shall be as compact, contiguous and nearly equal as

practicable.

Section 12 reads as follows:

The implementation of any attendance provisions for the

5a

1970-71 school year determined by any first class school dis

trict board shall be delayed pending the date of commence

ment of functions by the first class school district boards

established under the provisions of this amendatory act but

such provision shall not impair the right of any such board to

determine and implement prior to such date such changes in

attendance provisions as are mandated by practical necessity.

In reviewing, confirming, establishing or modifying atten

dance provisions the first class school district boards esta

blished under the provisions of this amendatory act shall have

a policy of open enrollment and shall enable students to

attend a school of preference but providing priority accep

tance, insofar as practicable, in cases of insufficient school

capacity, to those students residing nearest the school and to

those students desiring to attend the school for participation

in vocationally oriented courses or other specialized curri

culum.

Plaintiffs also seek a temporary restraining order and pre

liminary and permanent injunctions against the enforcement of

said provisions of Act 48.

VI.

This is also a proceeding for a permanent injunction enjoining

the defendant, Board of Education of the City of Detroit, its

members and the Superintendent of Schools from continuing their

policy, practice, custom and usage of operating the public school

system in and for the City of Detroit, Michigan in a manner which

has the purpose and effect of perpetuating a biracial segregated

public school system, and for other relief, as hereinafter more

fully appears.

VII.

On August 11, 1969, the Governor of the State of Michigan

approved Act No. 244 of the Public Acts of 1969 (Mich. Stats.

Ann. Section 15.2298), said Act being entitled, “AN ACT to re

quire first class school districts to be divided into regional districts

and to provide for local district school boards and to define their

6a

powers and duties and the powers and duties of the first class dis

trict board.” (A copy of Act No. 244 is attached hereto as Exhibit

B). Act No. 244 applies exclusively to the Board of Education of

the School District of the City of Detroit, that being the only first

class school district in the State of Michigan. The essence of Act

No. 244 is that it provides the mandate and means for the admini

strative decentralization of the Detroit school system and the ex

tent thereof.

On March 2, 1970, the Detroit School Board’s attorney ren

dered an opinion (attached hereto as Exhibit C) advising the Board

that in effectuating decentralization under Act No. 244 the law

imposed three limitations:

1. The Act itself required each district to have not less than

25,000 nor more than 50,000 pupils;

2. The United States Constitution required each district to

be in compliance with the “one man, one vote” principle;

3. The United States Constitution, above all, required that

the districts be established on a racially desegregated basis.

VIII.

In the 1969-70 school year, the Detroit Board of Education

operated 21 high school constellations providing a public educa

tion for 281,101 school children (excluding 12,758 students not

listed in high school constellations and in adult programs). 61.9%

of these students were Negro, 36.4% were white, and 1.7% were of

other racial-ethnic minorities. Of the 21 high school constellations

operated by the Detroit School Board in 1969-70, 14 were racially

identifiable as “white” or “Negro” constellations. The high school

constellations contain within them 208 elementary schools, 53

junior high schools, and 21 senior high schools. Of the 208 ele

mentary schools (enrolling 166,258 pupils), 114 (enrolling 92,225

pupils) are identifiable as “Negro” schools and 71 (enrolling

46,448 pupils) are identifiable as “white” schools. Of the 53

junior high schools (enrolling 63,476 pupils), 24 (enrolling 31,201

pupils) are identifiable as “Negro” schools and 18 (enrolling

7a

21,507 pupils) are identifiable as “white” schools. Of the 21

senior high schools (enrolling 54,394 pupils, 11 (enrolling 25,351

pupils) are identifiable as “Negro” schools and 6 (enrolling 19,183

pupils) are identifiable as “white” schools.

IX.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education adopted a

limited plan of desegregation (Exhibit D, attached hereto) for the

senior high school level, which plan was to take effect on a stair

step basis over a period of four years so that by 1972, there

would be substantially increased racial integration. This plan for

high school desegregation comtemplated a change in high school

boundary lines, thereby changing the junior high feeder patterns in

twelve of Detroit’s 21 senior high schools. The plan was designed

so that by the year 1972, only three (as compared to the present

17) of Detroit’s senior high schools would be racially identifiable

as “Negro” or “white” high schools. The plan also provided that a

student presently enrolled in a junior high school and who has a

brother or sister presently enrolled in a senior high school would

continue in senior high school at the school his brother or sister

was presently attending. All those presently enrolled in senior high

school would not, due to the stair-step feature of the plan, be

affected and they would continue through graduation at the segre

gated senior high school they were presently attending. The April

7 plan did not involve, nor did it affect, the existing racially segre

gated pattern of pupil assignments in the elementary and junior

high schools.

X.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education by a four-

to-two vote (the seventh member, now deceased, expressing his

approval by letter from his hospital bed) adopted a regional

boundary plan (attached hereto as Exhibit D) for administrative

decentralization consisting of seven regions. The seven regions as

established by the Board on April 7, 1970 contained an average of

38,802 pupils per region with the smallest region containing

33,043 pupils and the largest region containing 46,592 pupils, or a

range of deviation of 13,549 pupils with an average deviation of

8a

2,892 pupils per region. The racial complexion of the pupil enroll

ment in the seven regions averaged 61.7% Negro with the lowest

percent Negro region being 34.4% and the largest percent Negro

region being 76.7%, or a range of deviation of 42.3% Negro with

an average regional deviation of 10.5% Negro.

XI.

The actions of the Detroit School Board on April 7, 1970

approving a desegregation plan resulted in expressions of

“community hostility” . A movement to recall the four members

of the Detroit School Board who voted in favor of the April 7,

1970 action was initiated by white citizens. The recall movement

was resolved by the Detroit voters (of which a majority are white)

at the August 4, 1970 election, which resulted in the removal of

the four board members who had voted in favor of the April 7,

1970 plan. The April 7th plan created a similar reaction in the

Michigan State Legislature which culminated in the passage of

Public Act 48, interposing the State and voiding the partial dese

gregation plan, which Act was approved by the defendant,

Governor Milliken, on July 7, 1970.

XII.

On July 28, 1970, the attorney for the Detroit Board of

Education rendered an opinion (attached hereto as Exhibit E) that

Act 48 has both the design and the effect of completely elimi

nating the provisions of the April 7th plan adopted by the Board.

Section 2a of the Act provides that “ [rjegions shall be as com

pact, contiguous and nearly equal in population as practicable.”

This provision was intended to and does eliminate the efforts of

the Board on April 7, 1970 to create racially integrated regions.

Section 12 of Act 48 eliminates all provisions of the Board’s April

7th plan aimed at desegregation of the Detroit public schools by,

first, delaying the implementation of the attendance provisions

until January 1, 1971 and, second, by mandating an open enroll

ment (“freedom of choice”) policy qualified only by a provision

providing students residing nearest a school with an attendance

priority over those residing farther away. Section 12 has the fur

ther effect of eliminating two policies of the Detroit Board of

9a

Education: (1) prior to the adoption of Act 48, a student could

transfer to a school other than the one to which he was initially

assigned only if his transfer would have the effect of increasing

desegregation in the Detroit school system; (2) prior to the adop

tion of Act 48, whenever pupils had to be bused to relieve over

crowding, they were transported to the first and nearest school

where their entry would increase desegregation.

XIII.

Pursuant to the provisions of Section 2a of Act 48, the defen

dant, Governor William G. Milliken, on July 22, 1970 appointed a

three-member commission known hereafter as the Detroit Boun

dary Line Commission to draw the boundary lines for the eight

public school election regions mandated by Act 48. On August 4,

1970 the Detroit Boundary Line Commission adopted its plan and

presented its boundary lines for the eight election regions as called

for in Act 48. The Boundary Line Commission’s August 4th plan

(a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit F)Js a complete

negation of the Board’s April 7th region plan. The August 4th plan

creates eight regions with an average of 33,582 pupils in each

region with a range of deviation of 19,942 (the largest region con

tains 43,025 pupils while the smallest region contains 23,083) and

an average deviation for each region of 22.9%. Under the plan

adopted by the Detroit Boundary Line Commission on August 4,

1970, there will be new racially segregated school regions estab

lished in the defendant school system.

XIV.

Section 12 of the Act was enacted with the express intent of

preventing the desegregation of the defendant system. It applies to

but one school district in the State and reestablishes a policy

found by the United States Supreme Court to be an inadequate

method for elimination of segregated school attendance patterns.

It seeks to reverse a finding of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Michigan in Sherrill School Parents Com

mittee v. The Board o f Ed. o f the School District o f the City o f

Detroit, Michigan, No. 22092, E.D. Mich. Sept. 18, 1964, that the

“Open School” program does not appear to be achieving substan-

10a

tial student integration in the Detroit School System presently or

within the foreseeable future.

XV.

Plaintiffs allege that in the premises Public Act 48 on its face

and as applied violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States; the Act pertains solely to the Detroit

Board of Education and thereby deliberately prohibits the Detroit

Board of Education from making pupil assignments and estab

lishing pupil attendance zones in a manner which all other school

districts in the State of Michigan are free to do. Public Act 48

thereby creates an irrational, unreasonable and arbitrary classifi

cation which contravenes the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The distinction made by

Public Act 48 is further unconstitutional by the fact that it applies

solely to the Detroit school district where the bulk of Negro

school children in the State of Michigan are concentrated.

XVI.

Public Act 48 further violates the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution in that the Act impedes the legally

mandated integration of the public schools; the effect of the Act is

to perpetuate the segregation and racial isolation of the past and

give it the stamp of legislative approval. The Act, building upon

the preexisting public and private housing segregation, has the pur

pose, intent and effect of intensifying the present segregation and

racial isolation in the Detroit public schools. The Act further vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment in that it constitutes a reversal

by the State of Michigan of action taken by the Detroit School

Board which action was consistent with and mandated by the Con

stitution of the United States. In addition, Public Act 48 infringes

upon the Thirteenth Amendment in that its effect is to relegate

Negro school children in the City of Detroit to a position of

inferiority and to assert the inferiority of Negroes generally, there

by creating and perpetuating badges and incidents of slavery; and,

also, in that it denies to black persons in Detroit the same rights to

the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings as white

citizens enjoy.

11a

XVII.

The defendants, Board of Education of the City of Detroit

and Michigan State Board of Education, are charged under

Michigan law and the Constitution and laws of the United States

with the responsibility of operating a unitary public school system

in the City of Detroit, Michigan.

xvm.

Plaintiffs allege that they are being denied equal educational

opportunities by the defendants because of the segregated pattern

of pupil assignments and the racial identifiability of the schools in

the Detroit public school system. Plaintiffs further allege that said

denials of equal educational opportunities contravene and abridge

their rights as secured by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

XIX.

The plaintiffs allege that the defendants herein, acting under

color of the laws of the State of Michigan, have pursued and are

presently pursuing a policy, custom, practice and usage of oper

ating, managing and controlling the said public school system in a

manner that has the purpose and effect of perpetuating a segre

gated public school system. This segregated public school system is

based predominantly upon the race and color of the students

attending said school system; attendance at the various schools is

based upon race and color; and the assignment of personnel has in

the past and remains to an extent based upon the race and color of

the children attending the particular school and the race and color

of the personnel to be assigned.

XX.

The plaintiffs allege that the racially discriminatory policy,

custom, practice and usage described in paragraph XIX has in

cluded assigning students, designing attendance zones for elemen

tary junior and senior high schools, establishing feeder patterns to

secondary schools, planning future public educational facilities,

12a

constructing new schools, and utilizing or building upon the

existing racially discriminatory patterns in both public and private

housing on the basis of the race and color of the children who are

eligible to attend said schools. The said discriminatory policy, cus

tom, practice, and usage has resulted in a public school system

composed of schools which are either attended solely or pre

dominantly by black students or attended solely or predominantly

by white students.

XXI.

The plaintiffs allege that the racially discriminatory policy,

custom, practice and usage described in paragraph XIX has also

included assigning faculty and staff members employed by defen

dants to the various schools in the Detroit school system on the

basis of the race and color of the personnel to be assigned. Conse

quently, a general practice has developed whereby white faculty

and staff members have been assigned on the basis of their race

and color to schools attended solely or predominantly by white

students and Negro faculty and staff members have been assigned

on the basis of their race and color to schools attended solely or

predominantly by black students.

xxn.

The defendants have failed and refused to take all necessary

steps to correct the effects of their policy, practice, custom and

usage of racial discrimination in the operation of said school

system and to insure that such policy, custom, practice and usage

for the 1970-71 school year, and thereafter, will conform to the

requirements of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

xxm.

Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected on whose

behalf this action is brought are suffering irreparable injury and

will continue to suffer irreparable injury by reason of the pro

visions of the Act complained of herein and by reason of the

failure or refusal of defendants to operate a unitary school system

in the City of Detroit. Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate or com

13a

plete remedy to redress the wrongs complained of herein other

than this action for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief.

Any other remedy to which plaintiffs could be remitted would be

attended by such uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial

relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits and would cause fur

ther irreparable injury. The aid of this Court is necessary in

assuring the citizens of Detroit and particularly the black public

school children of the City of Detroit that this is truly a nation of

laws, not of men, and that the promises made by the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments are and will be kept.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray that upon the

filing of this complaint the Court:

1. Issue, pendente life, a temporary restraining order and a

preliminary injunction:

a. Requiring defendants, their agents and other persons

acting in concert with them to put into effect the partial plan

of senior high school desegregation adopted by the defendant,

Detroit Board of Education, on April 7, 1970, which plan

called for its implementation at the start of the 1970-71

school term, provided, however: (1) that the plan shall not be

effected on a stair-step basis, but shall, in accord with

Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), be

come completely and fully effective at the beginning of the

coming (1970-71) school year; and (2) that those provisions

which exclude a pupil who has a brother or sister presently

enrolled in a senior high school from being affected by the

plan shall be deleted in accord with Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d

191 (5th Cir. 1963);

b. Restraining defendants, their agents and other per

sons acting in concert with them from giving any force or

effect to Sec. 12 of Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of

1970 insofar as its application would impair or delay the dese

gregation of the defendant system;

c. Restraining defendants from taking any steps to

implement the August 4, 1970 plan, or any other plan, for

14a

new district or regional boundaries pursuant to Act 48, or

from taking any action which would prevent or impair the

im plem entation of the regions established under the

defendant Board’s earlier plan which provided for non-racially

identifiable regions;

d. Restraining defendants from all further school con

struction until such time as a constitutional plan for

operation of the Detroit public schools has been approved and

new construction reevaluated as a part thereof;

e. Requiring defendants to assign by the beginning of

the 1970-71 school year principals, faculty, and other school

personnel to each school in the system in accordance with the

ratio of white and black principals, faculty and other school

personnel throughout the system.

2. Advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy

hearing of this action according to law and upon such hearing:

a. Enter a judgment declaring the provisions of Act No.

48 complained of herein unconstitutional on their face and as

applied as violative of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the United States Constitution;

b. Enter preliminary and permanent decrees perpetu

ating the orders previously entered;

c. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from continuing to employ policies,

customs, practices and usages which, as described herein

above, have the purpose and effect of leaving intact racially

identifiable schools;

d. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from assigning students and/or

operating the Detroit school system in a manner which re

sults in students attending racially identifiable public schools;

e. Enter a decree requiring defendants, their agents,

15a

employees and successors to assign teachers, principals and

other school personnel to schools to eliminate the racial

identity of schools by assigning such personnel to each school

in accordance with the ratio of white and black personnel

throughout the system.

f. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from approving budgets, making

available funds, approving employment and construction con

tracts, locating schools or school additions geographically, and

approving policies, curriculum and programs, which are de

signed to or have the effect of maintaining, perpetuating or

supporting racial segregation in the Detroit school system.

g. Enter a decree directing defendants to present a com

plete plan to be effective for the 1970-71 school year for the

elimination of the racial identity of every school in the system

and to maintain now and hereafter a unitary, nonracial school

system. Such a plan should include the utilization of all

methods of integration of schools including rezoning, pairing,

grouping, school consolidation, use of satellite zones, and

transportation.

h. Plaintiffs pray that the Court enjoin all further con

struction until such time as a constitutional plan has been

approved and new construction reevaluated as a part thereof.

i. Plaintiffs pray that this Court will award reasonable

counsel fees to their attorneys for services rendered and to be

rendered them in this cause and allow them all out-of-pocket

expenses of this action and such other and additional relief as

may appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

Respectfully submitted,

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York

16a

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

Bruce Miller and

Lucille Watts, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan, and

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

17a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., )

Plaintiffs )

v. )

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

Defendants )

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACH- )

E R S, LOCAL N O . 231, AMERICAN )

FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, )

Defendant-Intervenor )

and )

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., ' )

Defendants-Intervenor )

CIVIL ACTION

NO: 35257

RULING ON ISSUE OF SEGREGATION

This action was commenced August 18, 1970, by plaintiffs,

the Detroit Branch of the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People* and individual parents and students, on

behalf of a class later defined by order of the Court dated February

16, 1971, to include “all school children of the City of Detroit

and all Detroit resident parents who have children of school age.”

Defendants are the Board of Education of the City of Detroit, its

members and its former superintendent of schools, Dr. Norman A.

Drachler, the Governor, Attorney General, State Board of Educa

tion and State Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of

Michigan. In their complaint, plaintiffs attacked a statute of the

State of Michigan known as Act 48 of the 1970 Legislature on the

ground that it put the State of Michigan in the position of uncon

stitutionally interfering with the execution and operation of a

voluntary plan of partial high school desegregation (known as the

April 7, 1970 Plan) which had been adopted by the Detroit Board

of Education to be effective beginning with the fall 1970 semester.

* The standing of the NAACP as a proper party plaintiff was not contested

by the original defendants and the Court expresses no opinion on the matter.

18a

Plaintiffs also alleged that the Detroit Public School System was

and is segregated on the basis of race as a result of the official

policies and actions of the defendants and their predecessors in

office.

Additional parties have intervened in the litigation since it was

commenced. The Detroit Federation of Teachers (DFT) which re

presents a majority of Detroit Public school teachers in collective

bargaining negotiations with the defendant Board of Education,

has intervened as a defendant, and a group of parents has inter

vened as defendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs’ motion for pre

liminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of Act 48 so as to

permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented. On that issue, this

Court ruled that plaintiffs were not entitled to a preliminary in

junction since there had been no proof that Detroit has a segre

gated school system. The Court of Appeals found that the “imple

mentation of the April 7 Plan was thwarted by State action in the

form of the Act of the Legislature of Michigan,” (433 F.2d 897,

902), and that such action could not be interposed to delay,

obstruct or nullify steps lawfully taken for the purpose of protect

ing rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The plaintiffs then sought to have this Court direct the de

fendant Detroit Board to implement the April 7 Plan by the start

of the second semester (February, 1971) in order to remedy the

deprivation of constitutional rights wrought by the unconstitu

tional statute. In response to an order of the Court, defendant

Board suggested two other plans, along with the April 7 Plan, and

noted priorities, with top priority assigned to the so-called “Magnet

Plan.” The Court acceded to the wishes of the Board and approved

the Magnet Plan. Again, plaintiffs appealed but the appellate court

refused to pass on the merits of the plan. Instead, the case was

remanded with instructions to proceed immediately to a trial on

the merits of plaintiffs’ substantive allegations about the Detroit

School System. 438 F. 2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971).

Trial, limited to the issue of segregation, began April 6, 1971

and concluded on July 22, 1971, consuming 41 trial days, inter-

19a

spersed by several brief recesses necessitated by other demands

upon the time of Court and counsel. Plaintiffs introduced sub

stantial evidence in support of their contentions, including expert

and factual testimony, demonstrative exhibits and school board

documents. At the close of plaintiffs’ case, in chief, the Court

ruled that they had presented a prima facie case of state imposed

segregation in the Detroit Public Schools; accordingly, the Court

enjoined (with certain exceptions) all further school construction

in Detroit pending the outcome of the litigation.

The State defendants urged motions to dismiss as to them.

These were denied by the Court.

At the close of proofs intervening parent defendants (Denise

Magdowski, et al.) filed a motion to join, as parties 85 contiguous

“suburban” school districts — all within the so-called Larger

Detroit Metropolitan area. This motion was taken under advise

ment pending the determination of the issue of segregation.

It should be noted that, in accordance with earlier rulings of

the Court, proofs submitted at previous hearings in the cause, were

to be and are considered as part of the proofs of the hearing on

the merits.

In considering the present racial complexion of the City of

Detroit and its public school system we must first look to the past

and view in perspective what has happened in the last half century.

In 1920 Detroit was a predominantly white city — 91% — and its

population younger than in more recent times. By the year 1960

the largest segment of the city’s white population was in the age

range of 35 to 50 years, while its black population was younger

and of childbearing age. The population of 0-15 years of age con

stituted 30% of the total population of which 60% were white and

40% were black. In 1970 the white population was principally

aging—45 years—while the black population was younger and of

childbearing age. Childbearing blacks equaled or exceeded the

total white population. As older white families without children of

school age leave the city they are replaced by younger black

families with school age children, resulting in a doubling of enroll

ment in the local neighborhood school and a complete change in

20a

student population from white to black. As black inner city re

sidents move out of the core city they “leap-frog” the residential

areas nearest their former homes and move to areas recently

occupied by whites.

The population of the City of Detroit reached its highest

point in 1950 and has been declining by approximately 169,500

per decade since then. In 1950, the city population constituted

61% of the total population of the standard metropolitan area and

in 1970 it was but 36% of the metropolitan area population. The

suburban population has increased by 1,978,000 since 1940.

There has been a steady out-migration of the Detroit population

since 1940. Detroit today is principally a conglomerate of poor

black and white plus the aged. Of the aged, 80% are white.

If the population trends evidenced in the federal decennial

census for the years 1940 through 1970 continue, the total black

population in the City of Detroit in 1980 will be approximately

840,000, or 53.6% of the total. The total population of the city in

1970 is 1,511,000 and, if past trends continue, will be 1,338,000

in 1980. In school year 1960-61, there were 285,512 students in

the Detroit Public Schools of which 130,765 were black. In school

year 1966-67, there were 297,035 students, of which 168,299

were black. In school year 1970-71 there were 289,743 students

of which 184,194 were black. The percentage of black students in

the Detroit Public Schools in 1975-76 will be 72.0%, in 1980-81

will be 80.7% and in 1992 it will be virtually 100% if the present

trends continue. In 1960, the non-white population, ages 0 years

to 19 years, was as follows:

0 - 4 years 42%

5 - 9 years 36%

10 - 14 years 28%

15 - 19 years 18%

In 1970 the non-white population, ages 0 years to 19 years, was as

follows:

21a

0 - 4 years 48%

5 - 9 years 50%

1 0 - 14 years 50%

15 - 19 years 40%

The black population as a percentage of the total population in

the City of Detroit was:

(a) 1900 1.4%

(b) 1910 1.2%

(c) 1920 4.1%

(d) 1930 7.7%

(e) 1940 9.2%

(f) 1950 16.2%

(g) 1960 28.9%

(h) 1970 43.9%

The black population as a percentage of total student population

of the Detroit Public Schools was as follows:

(a) 1961 45.8%

(b) 1963 51.3%

(c) 1964 53.0%

(d) 1965 54.8%

(e) 1966 56.7%

( 0 1967 58.2%

(g) 1968 59.4%

(h) 1969 61.5%

(i) 1970 63.8%

For the years indicated the housing characteristics in the City of

Detroit were as follows:

(a) 1960 total supply of housing

units was 553,000

(b) 1970 total supply of housing

units was 530,770

22a

The percentage decline in the white students in the Detroit

Public Schools during the period 1961-1970 (53.6% in 1960;

34.8% in 1970) has been greater than the percentage decline in the

white population in the City of Detroit during the same period

(70.8% in 1960; 55.21% in 1970), and correlatively, the percent

age increase in black students in the Detroit Public Schools during

the nine-year period 1961-1970 (45.8% in 1961; 63.8% in 1970)

has been greater than the percentage increase in the black popula

tion of the City of Detroit during the ten-year period 1960-1970

(28.9% in 1960; 43.9% in 1970). In 1961 there were eight schools

in the system without white pupils and 73 schools with no Negro

pupils. In 1970 there were 30 schools with no white pupils and 11

schools with no Negro pupils, an increase in the number of schools

without white pupils of 22 and a decrease in the number of

schools without Negro pupils of 62 in this ten-year period.

Between 1968 and 1970 Detroit experienced the largest increase

in percentage of black students in the student population of any

major northern school district. The percentage increase in Detroit

was 4.7% as contrasted with —

New York 2.0%

Los Angeles 1.5%

Chicago 1.9%

Philadelphia 1.7%

Cleveland 1.7%

Milwaukee 2.6%

St. Louis 2.6%

Columbus 1.4%

Indianapolis 2.6%

Denver 1.1%

Boston 3.2%

San Francisco 1.5%

Seattle 2.4%

In 1960, there were 266 schools in the Detroit School

System. In 1970, there were 319 schools in the Detroit School

System.

In the Western, Northwestern, Northern, Murray, North

eastern, Kettering, King and Southeastern high school service

23a

areas, the following conditions exist at a level significantly higher

than the city average:

(a) Poverty in children

(b) Family income below poverty level

(c) Rate of homicides per population

(d) Number of households headed by females

(e) Infant mortality rate

(f) Surviving infants with neurological

defects

(g) Tuberculosis cases per 1,000 population

(h) High pupil turnover in schools

The City of Detroit is a community generally divided by racial

lines. Residential segregation within the city and throughout the

larger metropolitan area is substantial, pervasive and of long stand

ing. Black citizens are located in separate and distinct areas within

the city and are not generally to be found in the suburbs. While

the racially unrestricted choice of black persons and economic

factors may have played some part in the development of this

pattern of residential segregation, it is, in the main, the result of

past and present practices and customs of racial discrimination,

both public and private, which have and do restrict the housing

opportunities of black people. On the record there can be no other

finding.

Governmental actions and inaction at all levels, federal, state

and local, have combined, with those of private organizations,

such as loaning institutions and real estate associations and broker

age firms, to establish and to maintain the pattern of residential

segregation throughout the Detroit metropolitan area. It is no

answer to say that restricted practices grew gradually (as the black

population in the area increased between 1920 and 1970), or that

since 1948 racial restrictions on the ownership of real property

have been removed. The policies pursued by both government and

private persons and agencies have a continuing and present effect

upon the complexion of the community — as we know, the choice

of a residence is a relatively infrequent affair. For many years

FHA and VA openly advised and advocated the maintenance of

“ harmonious” neighborhoods, i.e., racially and economically

24a

harmonious. The conditions created continue. While it would be

unfair to charge the present defendants with what other gov

ernmental officers or agencies have done, it can be said that the

actions or the failure to act by the responsible school authorities,

both city and state, were linked to that of these other govern

mental units. When we speak of governmental action we should

not view the different agencies as a collection of unrelated units.

Perhaps the most that can be said is that all of them, including the

school authorities, are, in part, responsible for the segregated con

dition which exists. And we note that just as there is an inter

action between residential patterns and the racial composition of

the schools, so there is a corresponding effect on the residential

pattern by the racial composition of the schools.

Turning now to the specific and pertinent (for our purposes)

history of the Detroit school system so far as it involves both the

local school authorities and the state school authorities, we find

the following:

During the decade beginning in 1950 the Board created and

maintained optional attendance zones in neighborhoods under

going racial transition and between high school attendance areas of

opposite predominant racial compositions. In 1959 there were

eight basic optional attendance areas affecting 21 schools.

Optional attendance areas provided pupils living within certain

elementary areas a choice of attendance at one of two high

schools. In addition there was at least one optional area either

created or existing in 1960 between two junior high schools of

opposite predominant racial components. All of the high school

optional areas, except two, were in neighborhoods undergoing

racial transition (from white to black) during the 1950s. The two

exceptions were: (1) the option between Southwestern (61.6%

black in 1960) and Western (15.3% black); (2) the option between

Denby (0% black) and Southeastern (30.9% black). With the

exception of the Denby - Southeastern option (just noted)

all of the options were between high schools of opposite

predominant racial compositions. The Southwestern-Western and

Denby-Southeastern optional areas are all white on the 1950,

1960 and 1970 census maps. Both Southwestern and South

eastern, however, had substantial white pupil populations, and the

25a

option allowed w hites to escape integration. The natural,

probable, foreseeable and actual effect of these optional zones was

to allow white youngsters to escape identifiably “black” schools.

There had also been an optional zone (eliminated between 1956

and 1959) created in “an attempt. . . to separate Jews and Gentiles

within the system ,” the effect of which was that Jewish

youngsters went to Mumford High School and Gentile youngsters

went to Cooley. Although many of these optional areas had

served their purpose by 1960 due to the fact that most of the

areas had become predominantly black, one optional area (South

western-Western affecting Wilson Junior High graduates) con

tinued until the present school year (and will continue to effect

11th and 12th grade white youngsters who elected to escape from

predom inantly black Southwestern to predominantly white

Western High School). Mr. Henrickson, the Board’s general fact

witness, who was employed in 1959 to, inter alia, eliminate

optional areas, noted in 1967 that: “In operation Western appears

to be still the school to which white students escape from pre

dominantly Negro surrounding schools.” The effect of eliminating

this optional area (which affected only 10th graders for the

1970-71 school year) was to decrease Southwestern from 86.7%

black in 1969 to 74.3% black in 1970.

The Board, in the operation of its transportation to relieve

overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused black pupils past or

away from closer white schools with available space to black

schools. This practice has continued in several instances in recent

years despite the Board’s avowed policy, adopted in 1967, to

utilize transportation to increase integration.

With one exception (necessitated by the burning of a white

school), defendant Board has never bused white children to pre

dominantly black schools. The Board has not bused white pupils

to black schools despite the enormous amount of space available

in inner-city schools. There were 22,961 vacant seats in schools

90% or more black.

The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

maintained and altered grade structures and created and altered

feeder school patterns in a manner which has had the natural,

26a

probable and actual effect of continuing black and white pupils in

racially segregated schools. The Board admits at least one instance

where it purposefully and intentionally built and maintained a

school and its attendance zone to contain black students.

Throughout the last decade (and presently) school attendance

zones of opposite racial compositions have been separated by

north-south boundary lines, despite the Board’s awareness (since

at least 1962) that drawing boundary lines in an east-west direc

tion would result in significant integration. The natural and actual

effect of these acts and failures to act has been the creation and

perpetuation of school segregation. There has never been a feeder

pattern or zoning change which placed a predominantly white

residential area into a predominantly black school zone or feeder

pattern. Every school which was 90% or more black in 1960, and

which is still in use today, remains 90% or more black. Whereas

65.8% of Detroit’s black students attended 90% or more black

schools in 1960, 74.9% of the black students attended 90% or

more black schools during the 1970-71 school year.

The public schools operated by defendant Board are thus

segregated on a racial basis. This racial segregation is in part the

result of the discriminatory acts and omissions of defendant

Board.

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and

Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy Statement

on Equality of Educational Opportunity, requiring that

“ Local school boards must consider the factor of racial

balance along with other educational considerations in making

decisions about selection of new school sites, expansion of

present facilities . . . . Each of these situations presents an

opportunity for integration.”

Defendant State Board’s “School Plant Planning Handbook”

requires that

“Care in site location must be taken if a serious transportation

problem exists or if housing patterns in an area would result

in a school largely segregated on racial, ethnic, or socio-

27a

economic lines.”

The defendant City Board has paid little heed to these statements

and guidelines. The State defendants have similarly failed to take

any action to effectuate these policies. Exhibit NN reflects con

struction (new or additional) at 14 schools which opened for use

in 1970-71; of these 14 schools, 11 opened over 90% black and

one opened less than 10% black. School construction costing

$9,222,000 is opening at Northwestern High School which is

99.9% black, and new construction opens at Brooks Junior High,

which is 1.5% black, at a cost of $2,500,000. The construction at

Brooks Junior High plays a dual segregatory role: not only is the

construction segregated, it will result in a feeder pattern change

which will remove the last majority white school from the already

almost all-black Mackenzie High School attendance area.

Since 1959 the Board has constructed at least 13 small pri

mary schools with capacities of from 300 to 400 pupils. This

practice negates opportunities to integrate, “contains” the black

population and perpetuates and compounds school segregation.

The State and its agencies, in addition to their general re

sponsibility for and supervision of public education, have acted

directly to control and maintain the pattern of segregation in the

Detroit schools. The State refused, until this session of the legisla

ture, to provide authorization or funds for the transportation of

pupils within Detroit regardless of their poverty or distance from

the school to which they were assigned, while providing in many

neighboring, mostly white, suburban districts the full range of

state supported transportation. This and other financial limita

tions, such as those on bonding and the working of the state aid

formula whereby suburban districts were able to make far larger

per pupil expenditures despite less tax effort, have created and

perpetuated systematic educational inequalities.

The State, exercising what Michigan courts have held to be is

“ plenary power” which includes power “to use a statutory

scheme, to create, alter, reorganize or even dissolve a school

district, despite any desire of the school district, its board, or the

inhabitants thereof,” acted to reorganize the school district of the

28a

City of Detroit.

The State acted through Act 48 to impede, delay and

minimize racial integration in Detroit schools. The first sentence

of Sec. 12 of the Act was directly related to the April 7, 1970

desegregation plan. The remainder of the section sought to pre

scribe for each school in the eight districts criterion of “free

choice” (open enrollment) and “neighborhood schools” (“nearest

school priority acceptance”), which had as their purpose and

effect the maintenance of segregation.

In view of our findings of fact already noted we think it

unnecessary to parse in detail the activities of the local board and

the state authorities in the area of school construction and the

furnishing of school facilities. It is our conclusion that these

activities were in keeping, generally, with the discriminatory

practices which advanced or perpetuated racial segregation in these

schools.

It would be unfair for us not to recognize the many fine steps

the Board has taken to advance the cause of quality education for

all in terms of racial integration and human relations. The most

obvious of these is in the field of faculty integration.

Plaintiffs urge the Court to consider alledgedly discriminatory

practices of the Board with respect to the hiring, assignment and

transfer of teachers and school administrators during a period

reaching back more than 15 years. The short answer to that must

be that black teachers and school administrative personnel were

not readily available in that period. The Board and the intervening

defendant union have followed a most advanced and exemplary

course in adopting and carrying out what is called the “balanced

staff concept” — which seeks to balance faculties in each school

with respect to race, sex and experience, with primary emphasis

on race. More particularly, we find:

1. With the exception of affirmative policies designed to

achieve racial balance in instructional staff, no teacher in the

Detroit Public Schools is hired, promoted or assigned to any

school by reason of his race.

29a

2. In 1956, the Detroit Board of Education adopted the

rules and regulations of the Fair Employment Practices Act as its

hiring and promotion policy and has adhered to this policy to

date.

3. The Board has actively and affirmatively sought out and

hired minority employees, particularly teachers and administra

tors, during the past decade.

4. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of Education

has increased black representation among its teachers from 23.3%

to 42.1%, and among its administrators from 4.5% to 37.8%.

5. Detroit has a higher proportion of black administrators

than any other city in the country.

6. Detroit ranked second to Cleveland in 1968 among the

20 largest northern city school districts in the percentage of blacks

among the teaching faculty and in 1970 surpassed Cleveland by

several percentage points.

7. The Detroit Board of Education currently employs black

teachers in a greater percentage than the percentage of adult black

persons in the City of Detroit.

8. Since 1967, more blacks than whites have been placed in

high administrative posts with the Detroit Board of Education.

9. The allegation that the Board assigns black teachers to

black schools is not supported by the record.

10. Teacher transfers are not granted in the Detroit Public

Schools unless they conform with the balanced staff concept.

11. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of Education

reduced the percentage of schools without black faculty from

36.3% to 1.2%, and of the four schools currently without black

faculty, three are specialized trade schools where minority faculty

cannot easily be secured.

30a

12. In 1968, of the 20 largest northern city school districts,

Detroit ranked fourth in the percentage of schools having one or

more black teachers and third in the percentage of schools having

three or more black teachers.

13. In 1970, the Board held open 240 positions in schools

with less than 25% black, rejecting white applicants for these

positions until qualified black applicants could be found and

assigned.

14. In recent years, the Board has come under pressure from

large segments of the black community to assign male black ad

ministrators to predominantly black schools to serve as male role

models for students, but such assignments have been made only

where consistent with the balanced staff concept.

15. The numbers and percentages of black teachers in Detroit

increased from 2,275 and 21.6%, respectively, in February, 1961,

to 5,106 and 41.6%, respectively, in October, 1970.

16. The number of schools by percent black of staffs changed

from October, 1963 to October, 1970 as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers — decreased from

41, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than 10%

black teachers — decreased from 58, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black teachers —

decreased from 99, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers —

increased from 72, to 124.

17. The number of schools by percent black of staffs changed

from October, 1969 to October, 1970, as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers — decreased from

6, to 4.

31a

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than 10%

black teachers — decreased from 41, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black teachers

decreased from 47, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers —

increased from 120, to 124.

18. The total number of transfers necessary to achieve a

faculty racial quota in each school corresponding to the system-

wide ratio, and ignoring all other elements is, as of 1970, 1,826.

19. If account is taken of other elements necessary to assure

quality integrated education, including qualifications to teach the

subject area and grade level, balance of experience, and balance of

sex, and further account is taken of the uneven distribution of

black teachers by subject taught and sex, the total number of

transfers which would be necessary to achieve a faculty racial

quota in each school corresponding to the system-wide ratio, if

attainable at all, would be infinitely greater.

20. Balancing of staff by qualifications for subject and grade

level, then by race, experience and sex, is educationally desirable

and important.

21. It is important for students to have a successful role

model, especially black students in certain schools, and at certain

grade levels.

22. A quota of racial balance for faculty in each school which

is equivalent to the system-wide ratio and without more is educa

tionally undesirable and arbitrary.

23. A severe teacher shortage in the 1950s and 1960s

impeded integration-of-faculty opportunities.

24. Disadvantageous teaching conditions in Detroit in the

1960s—salaries, pupil mobility and transiency, class size, building

conditions, distance from teacher residence, shortage of teacher

32a

substitutes, etc.—made teacher recruitment and placement dif

ficult.

25. The Board did not segregate faculty by race, but rather

attempted to fill vacancies with certified and qualified teachers

who would take offered assignments.

26. Teacher seniority in the Detroit system, although

measured by system-wide service, has been applied consistently to

protect against involuntary transfers and “bumping” in given

schools.

27. Involuntary transfers of teachers have occurred only

because of unsatisfactory ratings or because of decrease of teacher

services in a school, and then only in accordance with balanced

staff concept.

28. There is no evidence in the record that Detroit teacher

seniority rights had other than equitable purpose or effect.

29. Substantial racial integration of staff can be achieved,

without disruption of seniority and stable teaching relationships,

by application of the balanced staff concept to naturally occurring

vacancies and increases and reductions of teacher services.

30. The Detroit Board of Education has entered into suc

cessive collective bargaining contracts with the Detroit Federation

of Teachers, which contracts have included provisions promoting

integration of staff and students.

The Detroit School Board has, in many other instances and in

many other respects, undertaken to lessen the impact of the forces

of segregation and attempted to advance the cause of integration.

Perhaps the most obvious one was the adoption of the April 7

Plan. Among other things, it has denied the use of its facilities to

groups which practice racial discrimination; it does not permit the

use of its facilities for discriminatory apprentice training programs;

it has opposed state legislation which would have the effect of

segregating the district; it has worked to place black students in

craft positions in industry and the building trades; it has brought

33a

about a substantial increase in the percentage of black students in

manufacturing and construction trade apprenticeship classes; it

became the first public agency in Michigan to adopt and

implement a policy requiring affirmative act of contractors with

which it deals to insure equal employment opportunities in their

work forces; it has been a leader in pioneering the use of multi

-ethnic instructional material, and in so doing has had an impact

on publishers specializing in producing school texts and

in truc tiona l materials; and it has taken other noteworthy

pioneering steps to advance relations between the white and black

races.

In conclusion, however, we find that both the State of Michi

gan and the Detroit Board of Education have committed acts

which have been causal factors in the segregated condition of the

public schools of the City of Detroit. As we assay the principles

essential to a finding of de jure segregation, as outlined in rulings

of the United States Supreme Court, they are:

1. The State, through its officers and agencies, and usually,

the school administration, must have taken some action or actions

with a purpose of segregation.

2. This action or these actions must have created or

aggravated segregation in the schools in question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists. We find these tests

to have been met in this case. We recognize that causation in the case

before us is both several and comparative. The principal causes

undeniably have been population movement and housing patterns,

but state and local governmental actions, including school board

actions, have played a substantial role in promoting segregation. It

is, the Court believes, unfortunate that we cannot deal with public

school segregation on a no-fault basis, for if racial segregation in

our public schools is an evil, then it should make no difference

whether we classify it de jure or de facto. Our objective, logically,

it seems to us, should be to remedy a condition which we believe

needs correction. In the most realistic sense, if fault or blame must

be found it is that of the community as a whole, including, of

34a

course, the black components. We need not minimize the effect of

the actions of federal, state and local governmental officers and

agencies, and the actions of loaning institutions and real estate

firm s, in the establishment and maintenance of segregated

residential patterns — which lead to school segregation — to

observe that blacks, like ethnic groups in the past, have tended to

separate from the larger group and associate together. The ghetto

is at once both a place of confinement and a refuge. There is

enough blame for everyone to share.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the parties and the subject

matter of this action under 28 U.S.C. 1331 (a), 1343 (3) and (4),

2201 and 2202; 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1988, and 2000d.

2. In considering the evidence and in applying legal stand

ards it is not necessary that the Court find that the policies and

practices, which it has found to be discriminatory, have as their

motivating forces any evil intent or motive. Keyes v. Sch. Dist. No.

1, Denver, 383 F. Supp. 279. Motive, ill will and bad faith have

long ago been rejected as a requirement to invoke the protection

of the Fourteenth Amendment against racial discrimination. Sims

v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404, 407-8.

3. School districts are accountable for the natural, probable

and foreseeable consequences of their policies and practices, and

where racially identifiable schools are the result of such policies,

the school authorities bear the burden of showing that such

policies are based on educationally required, non-racial con

siderations. Keyes v. Sch. Dist., supra, and Davis v. Sch. Dist. o f

Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734, and 443 F.2d 573.

4. In determining whether a constitutional violation has

occurred, proof that a pattern of racially segregated schools has

existed for a considerable period of time amounts to a showing of

racial classification by the state and its agencies, which must be

justified by clear and convincing evidence. State o f Alabama v.

U.S., 304 F.2d 583.

35a

5. The Board’s practice of shaping school attendance zones

on a north-south rather than an east-west orientation, with the

result tha t zone boundaries conformed to racial residential

dividing lines, violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Northcross v.

Bd. o f Ed., Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661.

6. Pupil racial segregation in the Detroit Public School

S y s tem and the r e s id e n t ia l racial segregation resulting

primarily from public and private racial discrimination are interde

pendent phenomena. The affirmative obligation of the defendant

Board has been and is to adopt and implement pupil assignment

practices and policies that compensate for and avoid incorporation

into the school system the effects of residential racial segregation.

The Board’s building upon housing segregation violates the Fourte

enth Amendment. See, Davis v. Sch. Dist. o f Pontiac, supra, and

authorities there noted.

7. The Board’s policy of selective optional attendance

zones, to the extent that it facilitated the separation of pupils on

the basis of race, was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401, a ffd sub nom., Smuckv.

Hobson, 408 F.2d 175.

8. The practice of the Board of transporting black students

from overcrowded black schools to other identifiably black

schools, while passing closer identifiably white schools, which

could have accepted these pupils, amounted to an act of segre

gation by the school authorities. Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. o f

Ed., 311 F. Supp. 501.

9. The manner in which the Board formulated and modified

attendance ones for elementary schools had the natural and pre

dictable effect of perpetuating racial segregation of students. Such

conduct is an act of de jure discrimination in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. U.S. v. School District 151, 286 F. Supp.

786; Brewer v. City o f Norfolk, 397 F. 2d 37.

10. A school board may not, consistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment maintain segregated elementary schools or permit

educational choices to be influenced by community sentiment or

36a

the wishes of a majority of voters. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,

12-13, 15-16.

“A citizen’s constitutional rights can hardly be infringed

simply because a majority of the people choose that it be.”