McGautha v. State of California Brief Amicus Curiae for the United States

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGautha v. State of California Brief Amicus Curiae for the United States, 1970. 07db9c8a-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2b679861-0801-4486-ad11-4cbf89e1e36a/mcgautha-v-state-of-california-brief-amicus-curiae-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

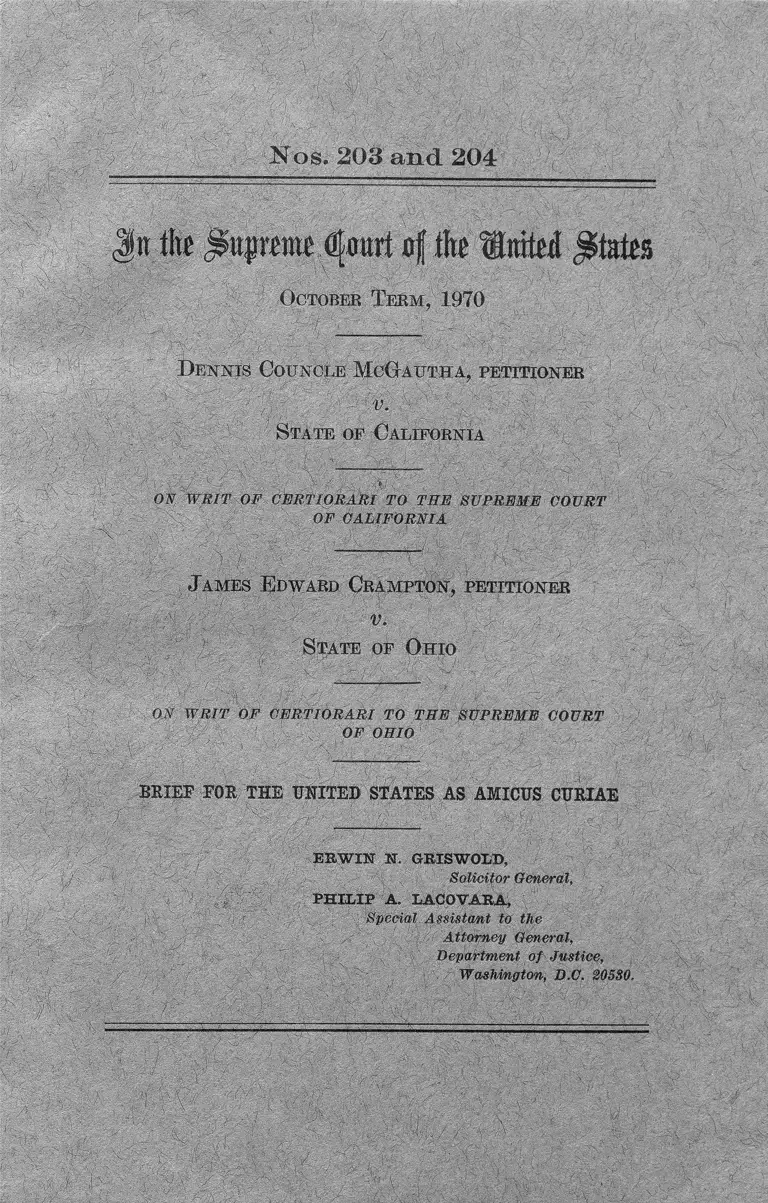

N o s . 2 0 8 a n d 2 0 4

T

October Term, 1970

Dennis CounCle;iJcCrA uth a, petitioner

v.

State of California

OX WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF CALIFORNIA

J ames Edward Crampton, petitioner

v.

State of Ohio

OX WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF OHIO

brief for the united states as amicus curiae

E R W IN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General,

P H IL IP A. LACOVARA,

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D,C. 20580.

/ / \ :

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below__________________________________ I

Jurisdiction_____________________________________ 2

Statutes involved_______________________________ 2

Questions presented_____________________________ 3

Statement:

I. McGautha:

A. The charges_____________________ 3

B. The guilt trial___________________ 4

C. The penalty trial________________ 4

D. Co-defendant’s case on punish

ment_________________________ 5

E. McGautha’s case on punishment. 7

F. Closing arguments______________ 8

G. Jury instructions on punishment._ 9

H. Jury deliberations, verdict, and

sentence______________________ 9

II. Crampton:

A. The charge______________________ 10

B. The prosecution’s evidence______ 11

C. The defense case________________ 15

D. Jury instructions________________ 17

E. Verdict and sentence____________ 17

Summary of argument__________________________ 18

Argument:

I. The United States Constitution does not

require that state legislatures prescribe

statutory standards to guide or govern

the jury’s determination of sentence in

a capital case_________________________ 25

a)

II

Argument— Continued age

I. The United States Constitution— Con

tinued

A. Historically, sentencing discre

tion, whether entrusted to judge

or jury, in capital and non

capital cases, has not depended

on legislative criteria:

1. Introduction: The attack

on “ standardless” sen

tencing in these cases

implicates all felony sen

tencing________________ 25

2. Jury sentencing discretion

is firmly established in

American criminal law:

(a) Jury-sentencing

in non-capital

cases__________ 29

(b) Jury-sentencing

in capital cases- 32

B. Jury discretion in capital cases

serves a legitimate governmen

tal interest___________________ 48

C. Juries can and do function ration

ally without explicit legislative

standards on capital sentencing- 66

D. The present system of jury dis

cretion in capital sentencing

does not violate any constitu

tionally protected interest of

an accused____________________ 78

II. Neither the privilege against self-incrimi

nation nor the due process clause re

quires separate trials on the issues of

guilt and punishment in every capital

case 83

I l l

Argument— C ontiirae d

II . Neither the privilege— Continued

A. The unitary trial is the estab

lished and approved mode for

even complex criminal cases__

B. A statute allowing the jury in a

capital case to fix punishment

as part of a single-stage guilt

trial does not violate the privi

lege against self-incrimination _ _

1. A defendant has no consti

tutional right to offer his

personal testimony limit

ed to the issue of punish

ment__________________

2. The defendant in a unitary

capital trial can present

mitigation evidence

through witnesses other

than himself___________

3. The unitary trial procedure

does not impermissibly

burden the exercise of

the privilege not to tes

tify—

C. A statute which authorizes the

jury in a capital case to fix pun

ishment in light of the evidence

adduced at a one-stage trial on

guilt is fundamentally fair____

1, A state may rationally de

termine that a sentence

for murder should be

based on the circum

stances of the crime it

self___________________

Page

84

90

91

99

102

107

1 0 8

IV

Argument— 0 ontinued

II. Neither the privilege— Continued

C. A statute which— Continued

2. Even at a murder trial

confined solely to guilt,

sufficient facts about the

defendant emerge to per

mit intelligent sentenc

ing____________________ 111

3. A separate hearing con

fined to penalty may

affirmatively disadvan

tage defendants________ 114

Conclusion______________________________________ 125

Appendix A: Statutes involved__________________ 126

Appendix B: Initial introduction of jury discretion

to set life sentence for murder and/or other capi

tal offenses (none providing statutory stand

ards)_________________________________________ 128

Appendix C: States authorizing jury to exercise

discretion in unitary trial to set sentence for

murder at death or life imprisonment (none pro

viding statutory standards)___________________ 132

Appendix D : States authorizing jury to exercise

discretion in separate, post-guilt proceeding to

set sentence for murder at death or life imprison

ment (none providing statutory standards)____ 136

Appendix E: Federal civil statutes authorizing

discretion in imposing capital punishment (none

providing statutory standards)________________ 138

Appendix F: Offenses under the Uniform Code of

Military Justice punishable by death or such

other punishment as a court martial may direct. 140

Appendix G:

Model Penal Code § 210.6____________________ 141

Study Draft of a New Federal Criminal Code

§§ 3602-3605_________________________________ 145

V

CITATIONS

Cases: page

Anderson, In re, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 73 Cal. Rptr.

21, 447 P. 2d 117 (1968)___________________ 46

Andres v. United States, 333 U.S. 740 (1948)__ 38,

39, 41, 47

Andrews v. Schwartz, 156 U.S. 272 (1895)____ 80

Ashbrook v. State, 49 Ohio App. 298, 197 N.E.

214 (1935)_________________________________ 100

Bagiev v. State, 247 Ark. 113, 444 S.W. 2d 567

(1969)____________________________________ 46

Baldwin v. New York, 399 U.S. 66 (1970)_ 45, 63, 75

Bell v. Patterson, 279 F. Supp. 760 (D. Colo.),

affirmed, 402 F. 2d 394 (C.A. 10, 1968)___ 29,

46, 85, 86, 87, 99

Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942)_________ 28

Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742 (1970)__ 102, 103

Brown v. Walker, 161 U.S. 591 (1896)______ 96

Brown v. United States, 356 U.S. 148 (1958)__ 98

Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123 (1968)__ 67, 92

Calloway v. United States, 399 F. 2d 1006

(C.A.D.C.), certiorari denied, 393 U.S. 987

(1968)____ . ______________________________ 33

Gallon v. Utah, 130 U.S. 83 (1889)________38,39

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County,

396 U.S. 320 (1970)______________________ 64

Coleman v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 22 (1967)_____ 65

Coleman v. United States, 334 F. 2d 558

(C.A.D.C. 1964)__________________________ 90

Coleman v. United States, 357 F. 2d 563

(C.A.D.C. 1965)__________________________ 59

Commonwealth v. Bell, 417 Pa. 291, 208 A. 2d

465 (1965)_______________________________ 118

Commonwealth v. Ross, 413 Pa. 35, 195 A. 2d

81 (1963)________________________________ 43

Contee v. United States, 440 F. 2d 249

(C.A.D.C. 1969)__________________________ 85

VI

Oases— Continued Page

Cook v. Willingham, 400 F. 2d 885 (C.A. 10,

1965)_______________________________________ 79

Crow Dog, Ex parte, 109 U.S. 556 (1883)____ 38

Duisen v. State,— Mo.— , 441 S.W. 2d 688

(1969)____________________________________ 47,60

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)__ 63,67

Ernst, Petition of, 294 F. 2d 556 (C.A. 3),

certiorari denied, 368 U.S. 917 (1961)------ 46, 100

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961)- .. 93, 96, 100

Fitzgerald v. Peyton, 303 F. Supp. 467 (W.D.

Va. 1969)_________________________________ 31

Florida ex rel. Thomas v. Culver, 253 F. 2d

507 (C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 358 U.S.

822 (1958)________________________________ 46

Frady v. United, States, 348 F. 2d 84

(C.A.D.C.), certiorari denied, 382 U.S. 909

(1965)____ 88,90,115,123

Frank v. United States, 395 U.S. 147 (1969) 110

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966) __ 31

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) __ 28

Gohlston v. State, 143 Tenn. 126, 223 S.W. 839

(1920)____________________________________ 35

Gore v. United States, 357 U.S. 386 (1958)__ 80

Gregg v. United States, 394 U.S. 489 (1969)__ 79

Harrison v. United States, 392 U.S. 219 (1968) _ 99

Hill v. United States, 368 U.S. 424 (1962)___ 95

Holmes v. United States, 363 F. 2d 281 (C.A.

D.C. 1966)_______________________________ 88

Howard v. Fleming, 191 U.S. 126 (1903)_____ 82

Hunter v. State,—Tenn.— , 440 S.W. 2d 1

(1969)__________________ ’_________________ 47,60

Jackman v. Rosenbaum Co, 260 U.S. 22 (1922) _ 44

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964)______ 67

Jackson v. State, 225 Ga. 790, 171 S.E. 2d 501

(1969)____________________________________ 88

VII

Cases— Continued Page

Johnson v. Commonwealth, 208 Ya. 481, 158

S.E. 2d 725 (1968), petition for certiorari

dismissed pursuant to Rule 60, 396 U.S.

801 (1969)_________________________________47,88

Johnson v. United States, 225 U.S. 405 (1912)_ 82

Jones v. State, 416 S.W. 2d 412 (Tex. Grim.

App. 1967)_______________________________ 123

Kemmler, In re, 136 U.S. 436 (1890)-------------- 32

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S.

452 (1947)_______________________________ 32

McCants v. State, 282 Ala. 397, 211 So. 2d 877

(1968), pending on petition for certiorari,

No. 5009 Misc., O.T. 1970________________ 46

McKane v. Durston, 153 U.S. 684 (1894)-------- 80

McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759

(1970)_________________________________ 102, 103

Manor v. State, 223 Ga. 594, 157 S.E. 2d 431

(1967) _____________________________ YT5G7 61

Mathis v. State, 283 Ala. 308, 216 So. 2d 286

(1968) _____________________________ 88

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F. 2d 138 (C.A.8,

1968), vacated, 398 U.S. 262 (1970)_______46, 87

Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627, 163 S.E. 2d 730

(1968)__________________________________ i — 46

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 (1969) 45,

82, 108

O’Callahan v. Parker, 395 U.S. 258 (1969).— 140

Parker v. North Carolina, 397 U.S. 790 (1970)- 102

Parman v. United States, 399 F. 2d 559 (C.A.

D.C.), certiorari denied, 393 U.S. 858

(1968)______________________________ 85

People v. Bandhauer, 1 Cal. 3d 609, 83 Cal.

Rptr. 184, 463 P. 2d 408 (1970)_____ 61

People v. Dusablon, 16 N.Y. 2d 9, 261 N.Y.S.

2d 38, 209 N.E. 2d 90 (1965) 121

VIII

Cases— Continued Page

People v. Fitzpatrick, 308 N.Y.S. 2d 18 (Co.

Ct. 1970)___________________________________ 47

People v. Floyd, 1 Cai. 3d 694, 83 Cal. Rptr.

608, 464 P. 2d 64 (1970)__________________ 118

People v. Hicks, 287 N.Y. 165, 38 N.E. 2d

482 (1941)__________________________________ 77

People v. Hurst, 42 111. 2d 217, 247 N.E. 2d

614 (1969)________________________________ 123

People v. Kelley, 44 111. 2d 315, 255 N.E. 2d

390 (1970)________________________________ 123

People v. McGautha, 70 Cal. 2^770, 76 Cal.

Rptr. 434, 452 P. 2d 650 (1969), certiorari

granted, 398 U.S. 936 (1970)___________ 1

People ex rel. McKevitt v. District Court,

— Colo.— , 447 P. 2d 205 (1968)_______ 88, 95, 99

Pope v. United States, 372 F. 2d 710 (C.A. 8,

1967) , vacated, 392 U.S. 651 (1968).. 46,88,113

Pope v. United States, 392 U.S. 651 (1968)--- 138

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932)__________ 28

Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 514 (1968)________ 110

Raff el v. United States, 271 U.S. 494 (1926) _ _ _ 96

Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957)____________ 28

Schwab v. Berggren, 143 U.S. 442 (1892)____ 94

Scott v. United States, 419 F. 2d 264 (C.A.D.C.

1969)______________________________________ 48,80

Segura v. Patterson, 402 F. 2d 249 (C.A. 10,

1968) ___________________ 46, 62, 87, 95, 99, 106

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968)- 98

Sims v. Eyman, 405 F. 2d 439 (C.A. 9, 1969)- 46,

109, 111, 112, 116

Smith v. State, 437 S.W. 2d 835 (Tex. Grim.

App. 1969)_______________________________ 122

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950)_______29, 79

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967)__ 79, 93, 94

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967)_______ 31,

38, 44, 67, 84, 86, 92, 98, 115, 116

IX

Cases— Continued Page

State v. Crompton, 18 Ohio St. 2d 182, 248 N.E.

2d 614 (1969), certiorari granted, 398 U.S.

936 (1970)__ ____________________________ 2,100

State v. Forcella, 52 N.J. 263, 245 A. 2d 181

(1968) , pending on petition for certiorari,

No. 5011 Misc., O.T. 1970— 47, 69, 88, 115, 116

State v. Johnson, 34 N.J. 212, 168 A. 2d 1,

appeal dismissed, 368 U.S. 145, certiorari

denied, 368 U.S. 933 (1961)______________ 29, 47

State v. Kelbach, 23 Utah 2d 231, 461 P. 2d 297

(1969) ______________________________ 47, 88, 95

State v. Latham, 190 Kan. 411, 375 P. 2d 788

(1962), certiorari denied, 373 U.S. 919 (1963) _ 47

State v. Maloney, 105 Ariz, 348, 464 P. 2d 793

(1970) __________________________________ 81

State v. Roseboro, 276 N.C. 185, 171 S.E. 2d

886 (1970), pending on petition for certiorari

No. 5178 Misc., O.T. 1970________________ 47, 61

State v. Smith, 74 Wash. 2d 744, 446 P. 2d

571 (1969), pending on petition for cer

tiorari, No. 5034 Misc., O.T. 1970___ 47, 69, 123

State v. Walters, 145 Conn. 60, 138 A. 2d 786,

appeal dismissed and certiorari denied, 358

U.S. 46 (1958)___________________________ 46

State v. Worthy, 239 N.C. 449, 123 S.E. 2d 835

(1962)____________________________________ 61

Stephens v. Turner, 421 F.2d 290 (C.A. 10,

1970)____________________________________ 48,82

Trap v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958)____________ 65

United States v. Chapman, 420 F. 2d 925 (C.A.

5,1969)_____________ 79

United States v. Curry, 358 F. 2d 904 (C.A. 2),

certiorari denied, 385 U.S. 873 (1966) _ 87, 88, 115

United States v. Gross, 416 F. 2d 1205 (C.A. 8,

1969), certiorari denied, 397 U.S. 1013

(1970) 79

X

Cases— Continued Page

United States v. Huff, 409 F. 2d 1225 (C.A. 5),

certiorari denied, 396 U.S. 857 (1969)_____ 85, 86

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968) _ 33,

87, 115, 117, 138

United States v. Kee Ming Hsu, 424 F. 2d 1286

(C.A. 2, 1970)____________________________ 79

United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Bamniller, 310

F. 2d 720 (C.A. 3, 1962), certiorari denied,

374 U.S. 828 (1963)____ . _________________ 88

United States ex rel. Smith v. Nelson, 275 F.

Supp. 261 (N.D. Calif. 1967)______________ 46

United States ex rel. Thompson v. Price, 258 F.

2d 918 (C.A. 3), certiorari denied, 358 U.S.

922 (1958)________________________________ 87

United States v. Trigg, 392 F. 2d 860 (C.A. 7),

certiorari denied, 391 U.S. 961 (1968)_______ 79

United States v. White, 225 F. Supp. 514

(D.D.C. 1963)______________________________ 115

Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U.S. 664 (1970)-. 43

Ward v. California, 269 F. 2d 906 (C.A. 9,

1959)___________________________________ ’ 121

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967)___ 100

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) __ 109

Wither son v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879)______32,38

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970)__ 45, 63, 105

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) __ 26,

28, 79, 93, 94, 109, 121

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 (1959)_-_27,

79, 93, 109

Williams v. Oklahoma City, 395 U.S. 458

(1969)____________________________________ 79

Wilson v. State, 225 So. 2d 321 (Fla. 1969)__ 46, 61

Winston v. United States, 172 U.S. 303 (1899)__ 38,

39, 54, 61, 62

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) __ 32,

38, 64, 65, 66

X I

Federal Statutes and Rules: Page

Act of January 15, 1897, c. 29, 29 Stat. 487 _ _ 129

Act of March 22, 1962, Pub. L. 87-423,

76 Stat. 46_______________________________ 131

Alaska Criminal Code, Act of March 3, 1899,

c. 429, 30 Stat. 1253______________________ 129

D.C. Code Ann. § 22-2404 (1967)___________ 133

Fed. R. Civ. P. 42(b)_______________________ 86

Fed. R. Crim. P. 14________________________ 86, 87

Fed. R. Grim. P. 32(a)_____________________ 95

Uniform Code of Military Justice:

Art. 85, 10 U.S.C. § 885_______________ 140

Art. 9o’ 10 U.S.C. § 890_______________ 140

Art. 94, 10 U.S.C. § 894_______________ 140

Art. 99, 10 U.S.C. § 899_______________ 140

Art. 100, 10 U.S.C. § 900______________ 140

Art, 101, 10 U.S.C. § 901______________ 140

Art. 102, 10 U.S.C. § 902______________ 140

Art. 104, 10 U.S.C. § 904______________ 140

Art. 106, 10 U.S.C. § 906______________ 140

Art. 110, 10 U.S.C. § 910______________ 140

Art. 113, 10 U.S.C. § 913______________ 140

Art. 118, 10 U.S.C. § 918______________ 140

Art. 120, 10 U.S.C. § 920______________ 140

18 U.S.C. § 34_____________________________ 139

18 U.S.C, § 794____________________________ 139

18 U.S.C, § 837(b)_______________ 138

18 U.S.C. § 1111___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 1114___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 1201(a)_________________________ 138

18 U.S.C. § 1716___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 1751___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 1992___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 2031___________________________ 139

18 U.S.C. § 2113(e)_________________________ 138

18 U.S.C. § 2381___________________________ 139

21 U.S.C. § 176b___________________________ 138

X II

Federal Statutes and Rules— Continued page

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)________________________ 2

28 U.S.C. § 1291___________________________ 80

42 U.S.C. § 2272___________________________ 138

42 U.S.C. § 2274___________________________ 138

42 U.S.C. § 2275________________________ 138

42 U.S.C. § 2276___________________________ 138

49 U.S.C. § 1472(i)_________________________ 139

State Statutes and Rules:

Ala. Code tit. 14, § 318 (1958)______________ 132

Ala. Penal Code of 1841, Acts 1841, p. 122— 128

Alaska Stat. § 11.15.010 (Supp. 1968)----------- 132

Alaska Stat. § 11.15.020 (Supp. 1968)----------- 132

Ariz. Terr. Acts 1885, No. 70_______________ 129

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-453 (1956)----------- 132

Ark. Acts 1915, No. 187------------------------------- 130

Ark. Stat. § 41-2227 (1964)_________________ 132

Ark. Stat. § 43-2153 (1964)_________________ 132

Cal. Amendatory Acts 1873-1874, ch. 508— 37, 129

Cal. Penal Code §190 (West, Supp. 1970)_ 2,126,

136

Cal. Penal Code § 190.1 (West, Supp. 1970)— 2, 4,

86,118, 126, 136

Cal. Penal Code § 1026_____________________ 86

Cal. Stat. 1957, ch. 1968, p. 3509------------------ 136

Colo. Laws 1901, ch. 64_____________________ 129

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 40-2-3 (1963)------------------ 132

Conn. Gen. Stat. § 53-10 (1968)------------------- 136

Conn. Penal Code §2 9 --------------------------------- 42

Conn. Penal Code, Pub. Acts 1969, No. 828_ 119, 136

Conn. Pub. Acts 1951, No. 369_____________ 131

Conn. Pub. Acts 1963, No. 588--------------------- 136

Dakota Terr. Laws 1883, ch. 9 --------------------- 129

Del. Code Ann. tit. 11, § 571 (Supp. 1988) —_ 132

Del. Code Ann, tit. 11, §3901 (Supp. 1968)__ 132

Del. Laws 1917, ch. 266____________________ 130

Fla. Acts 1872, No. 15, ch. 1877____________ 129

X III

State Statutes and Rules— Continued Page

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 782.04 (1965)_________ 133

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 919.23 (1944)_________ 133

Ga. Acts 1866, No. 208_____________________ 128

Ga. Acts 1866, No. 210_________________ __128

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1101 (Supp. 1969)_ 136

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-3102 (Supp. 1969)_ 136

Ga. Code 1861, §4220___ 128

Ga. Criminal Code, Laws 1968, p. 1249_____ 136

Ga. Laws 1970, No. 1333_________________ 120, 136

Hawaii Laws 1955, Act 239_________________ 131

Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 748-4 (1968)___________ 132

Ida. Code § 18-4004 (1948)_________________ 133

Ida. Gen. Laws 1911, ch. 68________________ 130

111. Ann. Stat. ch. 38, § 1-7 (Smith-Hurd,

Supp. 1970)____________________________ 123, 133

111. Ann. Stat. ch. 38, § 9-1 (Smith-Hurd,

1964)____________________________________ 133

111. Criminal Code, Laws 1961, p. 1983_____89, 133

111. Pub. Laws 1867, p. 90___________________ 128

Iowa Code Ann. § 690.2 (Supp. 1969)_______ 132

Iowa Laws 1878, ch. 165____________________ 129

Ind. Ann. Stat. § 9-1819 (1956)_____________ 133

Ind. Ann. Stat. § 10-3401 (1956)____________ 133

Ind. Rev. Stat. 1881, § 1904________________ 129

Kan. Criminal Code, Laws 1969, ch. 180____ 133

Kan. Laws 1935, ch. 154____________________ 130

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-3401 (Supp. 1969)_____ 133

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-4501 (Supp. 1969)____89, 133

Kan. Stat. Ann. §21-4606 (Supp. 1969)_____ 42

Kan. Stat. Ann. §21-4607 (Supp. 1969)_____ 42

Ky. Gen. Stat. 1873, ch. 29_________________ 129

Ky. Pub. Acts 1869, ch. 1659__________ 128

Ky. Rev. Stat. § 435.010 (1969)_____________ 133

Ky. R. Crim. P. § 9.84 (1969)______________ 133

La. Acts 1846, No. 139_____________________ 128

La. Code Crim. P. Ann. art. 817 (West 1967). 133

XIV

State Statutes and Rules— Continued Page

La. Stat. Ann. § 14.30 (1951)_______________ 133

Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 17, § 2651 (1964)___ 132

Md. Ann. Code art. 27, § 413 (1967)________ 133

Md. Laws 1916, ch. 214_____________________ 130

Mass. Acts 1951, ch. 203______________ (____ 131

Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 265, § 2 (1968)________ 133

Mich. Comp. Laws § 750.316 (Supp. 1970)___ 132

Minn. Gen. Laws 1868, ch. 88_______________ 128

Minn. Stat. Ann. § 609.185 (1964)__________ 132

Miss. Code Ann. §2217 (1956)______________ 133

Miss. Code Ann. § 2536 (1956)______________ 133

Miss. Laws 1872, ch. 76_____________________ 129

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 546.410 (1953)_____________ 134

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 559.030 (1959)____________ 134

Mo. Laws 1907, p. 235______________________ 130

Mont. Laws 1907, ch. 179___________________ 130

Mont. Rev. Codes § 94-2505 (1969)_________ 134

Neb. Laws 1893, ch. 44_____________________ 129

Neb. Laws 1969, ch. 213________________ 42, 90, 134

Neb. Rev. Stat. §28-401___________________ 134

Nev. Rev. Laws 1912, § 6386_______________ 130

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.030 (1969)____________ 134

N.H. Laws 1903, ch. 114____________________ 129

N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §585:4 (1955)_________ 134

N.J. Pub. Laws 1916, ch. 270_______________ 130

N.J. Stat. § 2A: 113-4 (1951)________________ 134

N.M. Laws 1939, ch. 49____________________ 130

N.M. Laws 1969, ch. 128_______________ 42, 90, 134

N.M. Stat. Ann. §40A -2-l (1964)__________ 134

N.M. Stat. Ann. §4QA-29-2 (1964)_________ 134

N.M. Stat. Ann. §40A-29-2.1 (Supp. 1969)._ 134

N.Y. Laws 1937, ch. 67_____________________ 130

N.Y. Laws 1963, ch. 994____________________ 136

N.Y. Penal Law §65.00 (1967)______________ 42

N.Y. Penal Law § 125.30 (1967)_____________ 136

N.Y. Penal Law §125.35 (1967)__________ 119, 136

XV

State Statutes and Rules— Continued page

N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-17 (1969)______________ 134

N.C. Sess. Laws 1949, ch. 299---------------------- 130

N.D. Cent. Code §12-06-06 (Supp. 1 9 6 9 )..- 132

N.D. Cent. Code §12-27-13 (1960)_________ 132

93 Ohio Laws 223 (1898)__________________ 37, 129

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2901.01 (Page 1954)___ 2,

83, 127,134

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2947.05 (Page 1954). 95

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 21, § 707 (1958)------------ 134

Okla, Terr. Stats. 1890, ch. 25______________ 129

Ore. Gen. Laws 1920, ch. 19------------------------- 130

Ore. Rev. Stat. § 163.010 (1967)____________ 132

Pa. Laws 1794, ch. 257--------------------------------- 34

Pa. Pub. Laws 1925, ch. 411_______________ 37,130

Pa. Pub. Laws 1959, No. 594------------------------ 136

Pa. Stat. tit. 18, § 4701 (1963)____________ 118, 136

R. I. Gen. Laws § 11-23-2 (1969)__________ 132

S. C. Acts 1878, No. 541__________________ 129

S.C. Acts 1894, No. 530____________________ 129

S.C. Code § 16-52 (1962)___________________ 134

S.D. Comp. Laws § 22-16-12 (1967)------------- 134

S.D. Comp. Laws § 22-16-13 (1967)________ 134

S.D. Comp. Laws § 23-48-16 (1967)________ 134

Term. Code Ann. § 39-2405 (1956)---------------- 135

Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-2406 (1956)--------------- 135

Tenn- Laws 1837-1838, ch. 29--------------------- 35, 128

Tex. Acts 1965, ch. 722-------------------------------- 137

Tex. Code Grim. P. Ann. art. 37.07 (Supp.

1970)_____________________________ 119,137

Tex. Gen. Laws 1858, ch. 121, art. 71a--------- 128

Tex. Penal Code Ann. art. 1257 (1961)--------- 137

Utah. Code Ann. § 76-30-4 (1953)--------------- 135

Utah Penal Code of 1876, Comp. Laws 1876,

p. 586____________________________________ 129

Yt. Acts 1910, No. 225______________________ 130

Yt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, § 2303 (Supp. 1969)— 135

XVI

State Statutes and Rules— Continued Page

Ya. Acts 1914, ch. 240______________________ 130

Va. Code § 18.1-22 (1960)__________________ 135

Ya. Code § 19.1-250 (1960)_________________ 135

Wash. Rev. Code § 9.48.030 (1956)_________ 135

Wash. Sess. Laws 1909, ch. 249_____________ 130

Wash. Sess. Laws 1919, ch. 112_____________ 130

W. Va. Code 1870, ch. 159__________________ 128

W. Ya. Code § 61-2-2 (1966)_______________ 132

Wis. Stat. Ann. § 940.01 (1958)_____________ 132

Wyo. Sess. Laws 1915, ch. 87_______________ 130

Wyo. Stat. § 6-54 (1957)___________________ 135

Foreign Statute:

Great Britain, Homicide Act of 1957, 5 & 6

Eliz. 2, c. 11, §§ 5, 6______________________ 54

Miscellaneous:

Appellate Power to Reduce Jury-Determined

Sentences, 23 Rutgers L. Rev. 490 (1969) __ 61

Appellate Review of Primary Sentencing De

cisions: A Connecticut Case Study, 69 Yale

L.J. 1453 (1960)__________________________ 28

American Bar Ass’n, Project on Minimum

Standards for Criminal Justice: Standards

Relating to Sentencing Alternatives and

Procedures (Tent. Draft 1967)____________ 28, 54

A.L.I., Model Penal Code (Tent. Draft No. 9,

1959)_______________________ 34, 42, 57, 58, 61, 88

A.L.I., Model Penal Code (Proposed Official

Draft 1962)____________ 42, 56, 74, 75, 77, 88, 141

36 A.L.I., Proceedings (1959)----------------- 57, 58, 116

Bedau, The Death Penalty in America (rev.

ed. 1967)__________________________ 34,49,60,61

Bifurcated Trial Procedure and First Degree

Murder, 3 Suffolk U.L. Rev. 628 (1969) __ 117

Bradford, An Enquiry How Far the Punish

ment of Death Is Necessary in Pennsylvania

(1795) 34

XVII

Miscellaneous— Continued

California and Pennsylvania Courts Divide on

Question of Admissibility of Details of Prior

Unrelated Offenses at Hearing on Sentencing

Under Split Verdict Statutes, 110 U. Pa. L.

Rev. 1036 (1962)_________________________

The California Penalty Trial, 52 Calif. L.

Rev. 386 (1964)____'_____________________

The Capital Punishment Controversy, 60 J.

Crim. L., Criminol. & Pol. Sci. 360 (1969) _

The Changing Role of the Jury in the Nineteenth

Century, 74 Yale L. J. 170 (1964)_________

Dawson, Sentencing: The Decision As to the

Type, Length, and Conditions of Sentence

(Am. Bar Foundation 1969)________ 27, 42, 58, 60

Executive Clemency in Capital Cases, 39

N.Y.U.L. Rev. 136 (1964)___________ . ___ 117

Frankfurter, Of Law and Men (Elman ed.

1956)________________________________ 69,70,112

George, Aggravating Circumstances in American

Substantive and Procedural Criminal Law, 32

U.M.K.C.L. Rev. 14 (1964)___________ 61

Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death

Penalty Unconstitutional, 83 Harv. L. Rev.

1773 (1970)__________________________ 68

Great Britain, Royal Commission on Capital

Punishment 1949-1953, Report (1953)_____ 53,

54, 70, 88

Great Britain, Select Committee on Capital

Punishment, Report (1930)_______________ 34,52

Hart, The Aims of the Criminal Law, 23 Law &

Contemp. Prob. 401 (1958)_______________ 111

117

118

66

30

Page

405 -3 8 S — 7 (

XVIII

Miscellaneous— Continued Page

Jury Sentencing in Virginia, 53 Ya. L. Rev.

968 (1967) — ____________________________ 30,31

Kadish, Legal Norm and Discretion in the Police

and Sentencing Process, 75 Harv. L. Rev.

904 (1962)_______________________ :_______ 28

Kalven, A Study of the California Penalty Jury

in First-Degree-Murder Cases: Preface, 21

Stan. L. Rev. 1297 (1969)________________ 74

Kalven & Zeisel, The American Jury (1966)__ 29,

59, 61, 68, 70, 71, 72, 77, 101, 120

Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in

Capital Cases, 101 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1099

(1953)_________________________ 38, 100, 112, 115

Michael & Wechsler, Criminal Law and Its

Administration (1940)____________________ 59

National Commission on Reform of Federal

Criminal Laws, Study Draft of a New Fed

eral Criminal Code (1970)________________ 42,

56, 58, 80, 88, 107, 145

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime,

77 Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964)_____________ 110

Poe, Capital Punishment Statutes in the Wake

of United States v. Jackson: Some Unresolved

Questions, 37 G.W.L. Rev. 719 (1969)_____ 33

Powers, Parole Eligibility of Prisoners Serving

a Life Sentence (Mass. Correctional Ass’n

1969)_____________________________________ 32

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Task Force

Report: The Courts (1967)_______________ 30,80

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, The Chal

lenge of Crime in a Free Society (1967) __ 28,32

X IX

Miscellaneous— Continued Page

Schwartz, Punishment of Murder in Penn

sylvania, in II Royal Comm’n on Capital

Punishment, Memoranda and Replies to a

Questionnaire 776 (1952)--------------------------- 37

Sentencing Disparity: Causes and Cures, 60

J. Crim. L., Criminol., & Pol. Sci. 182 (1969) _ 27, 42

Stephen History of the Criminal Law of

England (1883)----------------------------------------- 52

A Study of the California Penalty Jury in

First-Degree-Murder Cases: Standardless

Sentencing, 21 Stan. L. Rev. 1302 (1969)__ 51,

73, 77, 117

The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment—

From Wilkerson to Witherspoon and Beyond,

14 St. L. U. L. Rev. 463 (1970)___________ 62

Time Magazine, May 25, 1970--------------------- 59

The Two-Trial System in Capital Cases, 39

N.Y.U.L. Rev. 50 (1964)________________ 58, 118

U.S. Bureau of Prisons, National Prisoner Sta

tistics Bulletin: Capital Punishment 1930-

1968 (August 1969)------------------- ----------- 138,140

Wechsler, Codification of Criminal Law in the

United States: The Model Penal Code, 68

Colum. L. Rev. 1425 (1968)______________ 52

Wechsler, Degrees of Murder and Related As-

pects of the Penal Lav: in the United States,

in II Royal Comm’n on Capital Punishment,

Memoranda and Replies to a Questionnaire

783 (1952)_______________________________ 56

Wechsler, Symposium on Capital Punishment,

7 N.Y.L.F. 250 (1961)____________________ 51

Weigel, Appellate Revision of Sentences: To

Make the Punishment Fit the Crime, 20 Stan.

L. Rev. 405 (1968)_______________________ 28, 80

Jit Mxt $n$nm djourt of tlxt Mnlid JStatea

October Term, 1970

No. 203

Dennis Councle McG-autha, petitioner

v.

State of California

ON W R IT OF C E R TIO R AR I TO TH E SUPREME COURT

OF C ALIFO RN IA

No. 201

J ames Edward Crampton, petitioner

v.

State of Ohio

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R AR I TO TH E SUPREM E COURT

OF OHIO

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

O PIN IO N S B E L O W

The opinion o f the Supreme Court o f California

in People v. McGautha (Mc.A. 249-265) 1 is reported

at 70 Cal. 2d 770, 76 Cal. Rptr. 434, 452 P . 2d 650. * (l)

1 References to the printed appendices in the McGautha case

and in the Crampton case are abbreviated herein as “ Mc.A.”

and “ C.A.” , respectively. References to the transcript o f record

in the Crampton case will be given as “ R.” .

( l )

2

The opinion o f the Supreme Court o f Ohio in State

v. Crampton (C.A. 83-88) is reported at 18 Ohio St.

2d. 182, 248 N.E. 2d 614.

JU R IS D IC T IO N

The judgment of the Supreme Court o f California

in McGautha was filed on April 14, 1969, and rehear

ing was denied on May 14, 1969 (Me.A. 266). On

June 21, 1969, the petition for a writ o f certiorari

was filed. Certiorari was granted, 398 U.S. 936, on

June 1, 1970 (Me.A. 267), limited to Question 1 o f the

petition.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Ohio in

Crampton was filed on June 11, 1969 (C.A. 82), and

the petition for a writ of certiorari was filed on July 31,

1969. Certiorari was granted, 398 U.S. 936, on June 1,

1970 (C.A. 89), limited to Questions 2 and 3 of the

petition.

This Court’s jurisdiction rests in both cases on 28

TJ.S.C. 1257(3).

B y order o f June 29, 1970, the Court invited the

Solicitor General to submit a brief expressing the

views o f the United States in these two cases. 399

U.S. 924. This brief is submitted in response to that

order.

S T A T U T E S IN V O L V E D

Sections 190 and 190.1 o f the California Penal Code

and Section 2901.01 of the Ohio Revised Code are set

forth in Appendix A, infra, pp. 126-127.

3

QUESTIONS PR E SE N T E D

1 1 1 both cases:

1. Whether the principles o f clue process and equal

protection require that a State which provides for a

jury to determine if a death sentence should he im

posed after conviction for first degree murder in a

particular case must prescribe statutory standards to

guide or govern that sentencing decision.

In Crampton only:

2. Whether a defendant’s privilege against self

incrimination is violated by trying him under a stat

ute that authorizes the jury, as part o f a single

proceeding, to find the defendant guilty o f first degree

murder and also to limit his punishment, after such

a finding, to life imprisonment in place o f the death

penalty.

ST A T E M E N T

I. MC GATJTHA

A . T H E CHARGES

B y information filed on April 6, 1967, petitioner

Dennis Councle McGautha and co-defendants W il

liam Rodney Wilkinson and Fannie Lue Smith were

charged with the armed robbery o f one Pon Lock

on February 14, 1967, and with the armed robbery

and murder o f Benjamin Smetana on the same date

(Me.A. 1 -3). Petitioner McGautha was also charged

with four prior felony convictions: felonious theft,

robbery, murder without malice, and robbery by as

4

sault (Me.A. 3 -4 ).2 MeGautha and his co-defendant

Wilkinson went to trial on the information, after

Miss Smith’s case was severed (Me.A. 6, 34-35).

B . T H E G U IL T T R IA L

The evidence established that at about 2:30 pan.

on February 14, 1967, MeGautha and Wilkinson

entered a market in Los Angeles and, brandishing

pistols, kept one customer at bay while taking almost

$300 from the owner, Mrs. Pon Lock.

At approximately 5:30 that same afternoon, Me

Gautha and Wilkinson entered another market in

Los Angeles, operated by Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin

Smetana, again intent on armed robbery. While a

customer wns forcibly restrained by one o f the rob

bers, the other one struck Mrs. Smetana on the side

o f her head and she fell to the floor. A shot was fired,

and Mr. Smetana fell mortally wounded. The driver

o f the get-away car testified that MeGautha, admitted

shooting the shopkeeper (Me.A. 250-251).

The jury found both MeGautha and Wilkinson

guilty as charged o f two counts o f armed robbery and

one count of first degree murder (Me.A. 11-14).

C. T H E P E N A L T Y T R IA L

On the following day, a separate proceeding was

commenced before the same jury, pursuant to Section

190.1 of the California Penal Code, to enable the jury

2 In accordance with California practice, MeGautha admitted

these four prior convictions in a proceeding in chambers so that

the fact o f the convictions would not come before the jury at

the guilt trial (Me.A. 35-37).

to consider evidence on whether to fix life imprison

ment or death as the sentence on the murder convic

tions (Me. A. 15).

The State’s case at the penalty phase was limited

to the introduction of a file of documents from Texas

containing records of petitioner McGautha’s prior

felony convictions, photographs, and fingerprints

(Me.A. 81).

d . c o - d e f e n d a n t ’ s c a s e o n p u n i s h m e n t

Co-defendant Wilkinson then took the stand. He

testified that at the time of the trial he was twenty-

six years old, born in Mississippi the son of a white

father and a Negro mother. He had attended a Negro

school where his classmates teased him about his back

ground. After his father died Wilkinson had to leave

school in the 11th grade in order to help support his

mother, his sisters, and his younger brother (Mc.A.

84-85). At age 18 he enlisted in the Army, and served

without disciplinary action. He was honorably dis

charged after approximately six months of service

when his X.Q., somewhere in the eighties, failed to

meet revised Army standards (Mc.A. 85-86).

Wilkinson further testified that after returning

home to Mississippi, and while he was working to

support his family, a girl friend implicated him in a

bad-check episode, but he was not convicted of any

crime (Mc.A. 87). A fter that he went to California,

where he took a job and rented a room in a boarding

house run by a Baptist minister. He joined the min

ister’s church and continued his attendance until he

6

was arrested for the robberies and murder (Mc.A.

87-88).

He had worked steadily for a time, earning promo

tions and sending support to his family in Mississippi

(Mc.A. 88). A il this had changed when in July 1965

he was shot in the back in an unprovoked assault by

a street gang. A fter his hospital confinement, W il

kinson encountered difficulty getting or keeping a

job, and it became necessary for his mother to send

him money. It was during this period when he was

“ desperate for money” that Wilkinson met petitioner

McGaiitha and his associates and the subject o f hold

ups was broached to him (Mc.A. 91-92). Armed with

a broken pistol he had found and never fired, W il

kinson testified, he had participated in the two rob

beries, but denied actually knowing that the stores

were to be held-up until McGautha drew his gun at

each store. Wilkinson denied that he had drawn his

own pistol on either occasion (Mc.A. 95-100).

Wilkinson testified that it was McGrautha, not he,

who bad fired the fatal shot, and that it was Mc

Grautha who had struck Mrs. Smetana (Mc.A. 109, 112,

114, 119).

Wilkinson called five other witnesses on his behalf:

An undercover narcotics agent testified that he had

seen the murder weapon in McGrautha’s possession;

he had seen it kept under MeGrautha’s pillow on one

occasion, and on another occasion witnessed Mc

Grautha demonstrating his speed in drawing the gun

from his waistband, where he carried it (Mc.A. 137-

138). W ilkinson’s girl friend testified that they at

7

tended church services together (Me.A. 142). The

Baptist minister in whose boarding house Wilkinson

had lived testified that Wilkinson attended his church

and had a good reputation in the community. He also

stated that when he visited Wilkinson in jail prior

to trial, Wilkinson said he was horrified at what had

happened and asked the minister to pray for him

(Me.A. 145-147). A police sergeant who had investi

gated the crime testified that Wilkinson had been co-

operative following his arrest (Me.A. 151). A former

fellow employee who had also been Wilkinson’s busi

ness partner in a salvage project described Wilkinson

as an honest, non-violent person who had a good repu

tation (Me. A. 157).

E . M C G A U T IIA ’ S CASE ON P U N IS H M E N T

Petitioner McGautha too testified in his own be

half. Forty-one years old at the time of the trial, he

admitted to having a “ bad” criminal record but denied

that he had shot Mr. Smetana or struck his wife

(Mc.A. 159-160). Although he acknowledged that the

murder weapon was his, he testified that between the

two robberies Wilkinson had expressed concern that

his own automatic could hold only one shell and that for

this reason the two men had traded guns. Thus, Mc

Gautha testified, it was Wilkinson who had actually used

the pistol to club Mrs. Smetana and to kill her husband

(Me.A. 160-161).

McGautha also testified that his mother and father

had separated when he was four, that he had been

injured in combat in 1942, that he had worked for

8

various celebrities, that he had a heart condition, and

that he “ regretted” Mr. Smetana’s death (Me.A.

162-164).

McGrautha admitted his prior criminal record but

denied committing two of the robberies for which he

had been convicted and claimed that the murder-with-

out-maliee conviction involved only self-defense

(Me.A. 174-175). McGrautha also admitted a guilty

plea in 1964 to a charge o f carrying a concealed weap

on (Me. A. 177).

Asked why he had lied to the police during their in

vestigation o f the crime, McGrautha explained; “ Nor

mally, anyone would have done that, sir.” (Me.A.

180).

McGrautha called no other witnesses. Both defend

ants then rested.

F . CLOSIN G A R G U M E N T S

In closing arguments, the prosecutor stated to the

ju ry : “ Seriously consider whether or not the death

penalty should lie imposed on both defendants and as

to the person who was Benjamin Smetana’s killer fix

the penalty at death.” (Me.A. 206). It was Wilkinson,

the prosecutor argued, who struck Mrs. Smetana with

his own gun, but petitioner McGrautha who, using his

pistol, shot Mr. Smetana (Mc.A. 202). Mention was

also made of McGrautha’s prior felony convictions,

including an earlier criminal homicide, and of his re

fusal to acknowledge his responsibility for those past

crimes (Mc.A. 204-205).

W ilkinson’s counsel emphasized his client’s youth,

his prior unblemished record, his low I.Q., his candor,

and his remorse (Mc.A. 207-211). Petitioner Me-

9

Gautha’s counsel conceded that his client had a bad

record and that he had told some lies, but asked the

jury to set a life sentence because it was not Mc-

Gautha who had pulled the trigger (Me.A. 213, 218-

219).

G. J U R Y IN ST R U C T IO N S O N P U N IS H M E N T

In instructing the jury on its responsibility to fix

the penalty, the court advised them that while the law

forbade them to consider mere conjecture, prejudice,

or public feeling, they were free to be governed by

“ mere sentiment and sympathy” (Mc.A. 222). They

were told that they might also consider “ all of the

evidence o f the circumstances surrounding the crime,

o f each defendant’s background and history, and of

the facts in aggravation or mitigation of the penalty

which have been received here in court” (Mc.A. 222).

But the jurors were also told that they were entirely

free to set the punishment notwithstanding any facts

proved in aggravation or mitigation (Mc.A. 222-223).

They were further instructed th a ti ‘ the law itself pro

vides no standard for the guidance o f the jury in the

selection of the penalty, but, rather, commits the

whole matter o f determining which o f the two penal

ties shall be fixed to the judgment, conscience, and

absolute discretion of the ju ry ” (Mc.A. 223).

H . J U R Y D E LIB ER A TIO N S, VERDICT, A N D SEN TE N CE

During their deliberations on the penalty question,

the jury returned to the courtroom several times to

request further instructions and re-readings o f testi

mony. They had Mrs. Smetana’s testimony re-read,

and asked for that portion o f the testimony of the

10

driver of the get-away car that discussed what each

o f the defendants had in his hands when leaving the

Smetana market (Mc.A. 225-226).3 After another re

reading of a portion o f Mrs. Smetana’s testimony

was requested and allowed (Mc.A. 229-230), the jury

once again interrupted its deliberations to ask for a

re-reading o f the entire testimony o f two other wit

nesses, and this was done (Mc.A. 231). A fter further

deliberations, the jurors returned with a verdict fix

ing W ilkinson’s penalty at life imprisonment and

petitioner McGrautha’s sentence at death (Mc.A. 231-

232).4

On September 15, 1967, Wilkinson was accordingly

sentenced to life imprisonment upon his murder con

viction (Mc.A. 31, 235-237). Petitioner McGrautha’s

sentencing was postponed until September 29, 1967,

to permit the Probation Department to prepare a

probation report. (Mc.A. 237). On that date, the

court denied McGrautha’s motion for a new trial or

for a modification o f the penalty verdict, and sen

tenced him to death (Mc.A. 32-33, 239-248).

II. CRAMPTOlSr

A . T H E CHARGE

Petitioner James Edward Crampton was indicted

by a grand jury in Lucas County, Ohio, on March 2,

1967, and charged with murdering W ilma Jean

3 Because o f difficulty locating the portions desired, the wit

ness’s entire testimony was re-read to the jury (Mc.A. 228-229).

4 Deliberations on the penalty question had begun at 2:12

p.m. on August 24, 1967, and the verdicts were returned at

4:45 p.m. on August 25, 1967 (Mc.A. 224, 231).

11

Crampton, purposely and with premeditated malice,

on January 17th o f that year (C.A. 4).

He pleaded not guilty to the charge and alterna

tively pleaded not guilty by reason o f insanity

(C.A. 4 ). He was then committed to Lima State

Hospital for one month’s observation, and when the

hospital subsequently reported that Crampton would

be considered sane he was ordered to stand trial

(C.A. 1).

B . T H E PR O SEC U TIO N 'S EVIDENCE

The State’s evidence established the following facts:

Petitioner Crampton had married the deceased ap

proximately four months prior to her death (R. 45;

C.A. 57). The deceased’s brother testified that about

two months before the killing, Crampton had been

allowed to leave the state hospital where he was un

dergoing observation to attend the funeral o f his

w ife ’s father. A fter the funeral, the witness said he

discovered Mrs. Crampton crying because her husband

had taken a knife and run away. In the interim,

Crampton had telephoned the house, and when his

wife warned him to return to the hospital he told

her “ I f you call the police, I will kill you then get

to your mother” (R . 23-24, 35). Later that evening,

after Mrs. Crampton and the witness notified the po

lice, Crampton was picked up by the authorities

(R . 37-38).

A friend o f the victim testified that she was at the

victim ’s home four days prior to the killing, when

Crampton arrived and kicked and pounded on the

back door until he was admitted (R . 41-42). Cramp-

12

ton then pushed his wife into the living room, and

upstairs. He had a knife in one hand and was holding

his wife at the same time. He said i f anyone called

the police he would kill them all (R . 42-43, 50). Later

that evening he telephoned and told the witness to

leave. The witness said she would but would take Mrs.

Crampton with her. At that Crampton said he would

come back to get them all with a gun he had (R . 43).

Later witnesses confirmed that Crampton had made

threats on his w ife’s life and that police protection

had been ordered about ten days before the murder

because of W ilma Jean Crampton’s fear o f her hus

band (R . 174, 212, 215).

In the course o f the testimony o f one of the State’s

witnesses it was brought out that he had first met

Crampton in 1964 while they were both “ doing tim e”

in the Michigan State Prison (R . 58) ; that he had

met Crampton again on January 14, 1967, in Pontiac,

Michigan; that Crampton purchased some ampheta

mines (R . 61) ; that Crampton talked of his activities

since his release from the Leavenworth Penitentiary,

including his admission to a hospital for drug addic

tion (R . 61) ; that on the evening o f January 14 he

and the defendant drove to Cary, Indiana, where

Crampton stole some license plates and put them on

his rented car (R. 62) ; that they checked into a motel

where they pilfered some money from the coin box

o f a mechanical vibrator (R . 63); that Crampton

found his w ife ’s car and towed it away (R . 62-63) ;

that Crampton burglarized some coin machines and

stole a typewriter at a truck stop (R. 65) ; that on

13

the evening o f January 15, Crampton broke into a

hospital to get some drugs, and stole some shaving

equipment and a jacket as well (R . 68-69); and

that Crampton then forged another prescription for

amphetamines and obtained the drugs from a phar

macy, unsuccessfully trying the same technique to

secure a different drug for his traveling companion,

the witness (R . 71). A fter injecting drugs directly

into his vein and after obtaining some more pills at

another drug store, Crampton telephoned his wife in

Toledo, and after the call announced that he and the

witness had to drive there right away (R . 72-73,

108-109).

Crampton and his friend arrived in Toledo in the

early morning hours of January 17 (R. 73). A fter

first stopping at his w ife ’s house, Crampton and the

witness drove to the home of Crampton’s mother-in-

law; they broke in and stole several items including

a rifle, some ammunition, and a few handguns— in

cluding one later identified as the murder weapon

(R. 76-78). Crampton kept that pistol, a .45 caliber

automatic, with him from then on (R. 79-80).

Crampton then indicated that he suspected that his

wife and her ex-boss were having an illicit affair, and

Crampton and the witness drove around to several

locations, in a car Crampton had just stolen, trying

to find the couple (R. 78-82). As he was driving with one

hand, Crampton fired the automatic out the car win

dow, commenting that a slug like that could do quite

a bit o f damage, and adding “ I f I find them together

I ’m going to kill both of them” (R . 80).

405- 388— 70 3

14

Later, Crampton located his wife at home by tele

phone, and quickly drove out to the home. He told

the witness: ‘ ‘Leave me off right here in front of the

house and you take the car and go back to the park

ing lot and if I ’m not there by six o ’clock in the

morning you ’re on your own” (R . 82).

On the following morning the police were sum

moned to Mrs. Crampton’s home by her daughter,

the child o f a previous marriage, when the daughter

was unable to rouse anyone at the house (R . 129-130).

The investigating officer found Mrs. Crampton’s dead

body in an upstairs bathroom. She had been shot in

the face at close range underneath her right eye.

A .45 caliber shell casing was found beside the body.

(R. 132-133, 167-168, 221-222, 230-231). The jacket

Crampton had stolen during the hospital burglary a

few days earlier was found in the living room (R. 69,

79, 204-205, 223, 229).

In the interim, before discovery o f his w ife ’s body,

Crampton had been arrested for driving a stolen ear.

Between the bucket seats in the car Crampton was

driving was the murder weapon, a .45 caliber auto

matic pistol (R . 139-141).

A fter being advised o f his constitutional rights,

Crampton admitted stealing the car and the .45 cali

ber pistol, and told about the other crimes he had

committed over the past few days; he declined, how

ever, to discuss his wife (R. 164-166, 170, 180-181,

224-228). A tape recording o f one questioning ses

sion, containing these admissions and a reference to

several years Crampton had spent in prison, was

played before the jury (R . 252-266).

15

C. T H E DEFENSE CASE

As part of the defense case, Cramp ton’s mother was

called as a witness. She stated he was born in 1926,

making him 41 years old at the time o f the trial

(C.A. 49). At age nine she said Crampton had fallen

off an ice truck and injured his head (C.A. 53). He

was raised in a broken home until he left at age 14

because his stepfather did not want him around (C.A.

49). He reportedly was a good student but attended

only one year of regular high school (C.A. 50-51).

Later, after a dishonorable discharge from the Navy,

he completed his high school education in the Jackson

Prison while serving part o f a 10-15 year sentence

for robbery (A . 52). He also spent time in Leaven

worth, his mother testified, for interstate transporta

tion of a stolen ear (C.A. 56). He was also known by

his mother to have been a drug addict since at least

1949 (C.A. 55, 59).

During this period, he had married, had a child,

been divorced, remarried to the same woman, and

again divorced (C.A. 54-56). He married Wilma

Jean Crampton in September 1966, approximately

four months before she was murdered (C.A. 57).

In support o f his insanity defense, Crampton in

troduced a series of hospital studies and reports, to

gether with reports collected by hospital personnel

from various state correction authorities. These docu

ments contained a substantial amount of informa

tion about his background. For instance, it appeared

that Crampton’s intelligence was in the average to

above-average range measuring from 106 to 113 on

16

various tests (C.A. 24, 40). The documents also

showed that Crampton had a juvenile record, plus

convictions for grand larceny, armed robbery, and

interstate auto theft. He was a parole violator and

had previously escaped from jail. W hile in the Navy

he was court-martialed for larceny and impersonat

ing an officer, and given an undesirable discharge.

A fter then fraudulently enlisting in the Army, he

was again court-martialed and dishonorably dis

charged. He had a long arrest record and was ad

dicted to narcotics and amphetamines. Because of

his frequent incarceration, he had no significant em

ployment record (C.A. 14-15, 21-23, 26-27, 30, 32-33,

42, 46).

One report, based on information given by Cramp-

ton’s wife when he was admitted to a state hospital

for observation about two months prior to her mur

der, recorded that Crampton had struck her and

threatened her with a knife (C.A. 9).

One of the reports prepared after Crampton was

committed for observation following his insanity plea

recited that he had suspected his wife o f infidelity

(C.A. 21). Various reports spoke of Crampton’s claim

that the shooting was accidental; that his wife had

talked about shooting herself if Crampton did not

return to the hospital ; that he was gathering up the

guns around the house and had just removed the

clip from one gun when his wife, who was sitting on

the toilet, asked to see i t ; and that in handing the gun

17

to her, it somehow discharged, wounding her fatally

in the head (C.A. 21-24).5

All reports concluded that Crampton was sane, with

no psychosis, organic brain damage, detachment

from reality, or inability to distinguish right from

wrong. H is condition was characterized simply as

an anti-social or sociopathic reaction, coupled with

alcohol and drug addiction (C. A. 18, 20, 24, 25, 31).

D. J U R Y IN ST R U C T IO N S

After instructing the jury on the elements o f first

degree murder, possible lesser included offenses, and

the defense o f insanity (C.A. 60-70), the court told

the jury of its punishment responsibility:

I f you find the defendant guilty of murder

in the first degree, the punishment is death,

unless you recommend mercy, in which event

the punishment is imprisonment in the peni

tentiary during life (C.A. 70).

E . VERDICT A N D SEN TEN CE

The jury retired to deliberate at 2 :Q0 p.m. on

October 30, 1967, and at 6 :15 p.m. they returned with

a verdict o f guilty o f murder in the first degree, with

no recommendation o f mercy (C.A. 2, 78).

Sentence was imposed on November 15, 1967.

Crampton was given the opportunity to state any

5 In its instructions, the court charged the jury that there

was some evidence that the killing was accidental, and that

acceptance o f such evidence would require a verdict of not

guilty (C.A. 68).

18

reasons why sentence should not be imposed. He made

certain statements that were found insufficient to

prohibit the passing o f sentence. He was accordingly

sentenced to death, as required by the Ohio statute in

the absence o f a jury recommendation o f mercy

(C.A. 2-3, 78-79).

S U M M A R Y OR A R G U M E N T

In the view o f the United States, there is no con

stitutional impediment to affirmance o f the convic

tions in both o f these cases.

I

A. The common attack made both by McGautha

and by Crampton is that the absence o f statutory

standards or criteria to govern or guide the ju ry ’s

determinaton o f punishment invalidates the death

sentences imposed upon them. The argument that

the Constitution requires legislative formulation of

sentencing standards for jury sentencing in capital

cases equally calls into question the settled practice

o f authorizing judges to set sentences in the exercise

o f broad discretion in non-capital felony eases with

out providing extrinsic standards. Such a thrust runs

counter not only to the modern philosophy o f max

imizing sentence flexibility but also to this Court’s

pronouncements that sentencing procedures are not

governed by the same rigid requirements that are

constitutionally necessary for trying a defendant’s

guilt.

Jury sentencing in non-capital eases originated in

colonial times and survives today in one-quarter o f

19

the States. The authority for the jury in a capital

case to determine whether the death penalty should

be imposed upon conviction dates from at least 1838

and was well established by the time the Fourteenth

Amendment was ratified. Virtually every American

jurisdiction at some point or other has conferred

discretionary power on the jury in a capital murder

case to determine the penalty, and this practice is

followed today wherever the death penalty for mur

der is retained. In the entire history of this univer

sally accepted feature of our criminal laws no State,

even when adopting other major alterations to its

criminal code, has found it necessary or desirable to

codify the considerations which should govern the

ju ry ’s conscientious sense of judgment on this ques

tion. For at least a century this Court and lower

federal and state courts have reviewed convictions

and death sentences set by juries under these statutes

and neither this Court nor any other has heretofore

expressed anything but approval for the wisdom and

fairness o f entrusting flexible sentencing discretion

to the trial juries in capital cases. This unbroken

chain o f legislative and judicial approval of “ stand

ardless” jury discretion in capital cases presents a

powerful presumption that the practice is funda

mentally fair within the meaning of the Due Process

Clause.

B. Allowing a capital jury freedom to exercise its

judgment on the question of the proper sentence in a

particular case serves a legitimate public interest.

There is first o f all a variety o f sound objections to

any different approach. An attempt to codify “ stand

2 0

ards” that would be exclusive and exhaustive in the

same sense as the elements of a crime would foolishly

reintroduce the rigidity of long discredited automatic

sentences; it is just not reasonably possible to define

in advance exactly how a particular crime committed

by a particular defendant should be punished. Some

sentencing discretion is therefore essential. Proposals

like that of the Model Penal Code to formulate a list

o f illustrative considerations that the sentencer in an

actual case might treat as tending to aggravate or

to mitigate the punishment suffer from other objec

tions. There is considerable doubt that such criteria

alert the modern jury to any pertinent considerations

that would not be self-evident in the context o f a

concrete case. But in addition, respectable authority

supports the fear that formal statutory enumeration

of factors considered by the State to be “ aggravating”

may upset the current demonstrable reluctance of

jurors to set a death sentence when they are charged

with the intensely personal responsibility for deter

mining the penalty. Moreover, statutory enumeration

o f abstract criteria could interfere with the legitimate

State policy o f leaving the life-and-death decision on

penalty to the contemporary conscience o f the com

munity speaking through the jury.

C. Arguments that the Constitution requires statu

tory standards to circumscribe the jury ’s sentencing

discretion proceed on erroneous legal and factual prem

ises, This Court has repeatedly emphasized that an

essential basis for our national commitment to trial

by jury is the assumption that juries act fairly, ra

2 1

tionally, and intelligently. Any contrary speculation

in this type o f case must assume that twelve jurors

Screened by defense counsel will conclude their delib

erations with agreement that a man should die in the

absence o f any weighty reason or by virtue of some

vicious bias. The empirical data demonstrate quite the

opposite conclusion: that under the present system

juries do act reasonably on the basis o f pertinent con

siderations and that in so deciding they do not rely

on any irrational factor or on any personal bias. Thus,

whatever favorable reasons there may be for enacting

formal lists of sentencing criteria, they cannot be said

to be essential to just and rational sentencing by

the modern American jury— a jury that must be

chosen so as to insure that it will fairly represent the

community.

D. The current practice of “ standardless” jury sen

tencing does not violate any specific constitutional

rights o f an accused. It is well settled that a defend

ant cannot insist on “ notice” of the considerations that

may enter into his post-conviction sentencing and can

not demand an opportunity to litigate sentencing fac

tors. Statutory criteria cannot be said to be essential

to permit meaningful review since the Constitution

does not assure the right to appeal, and particularly

does not guarantee review of a sentence otherwise

within prescribed limits. In the few States where

sentence review is authorized, the courts have experi

enced no difficulty exercising their responsibilities;

on the contrary, to the extent formal criteria are pro

vided the practical scope of review may be contracted

since nearly every first-degree murder case contains

2 2

some “ aggravating” aspects, however defined, that

would sustain a death sentence.

Thus, we suggest, nothing in the Constitution com

pels the States to do what no jurisdiction has found

necessary or wise: formulate “ sentencing standards”

for juries in capital cases.

I I

A. Although six States have by recent statute de

cided to separate capital (or all felony) trials into

two stages, focusing separately on guilt and on pun

ishment, no court has held such a procedure mandated

by the Constitution in any context. This Court itself

on several occasions has declined to find bifurcated

trials constitutionally compelled, noting to the con

trary that they are essentially alien to our criminal

jurisprudence. Our system of criminal procedure as

sumes that a criminal trial is essentially an integated

disposition of all jury-triable issues, and it has never

been held constitutionally necessary to isolate even

complex issues for separate jury trials.

B. Petitioner Crampton’s insistence that the uni

tary trial creates an impermissible tension between

two constitutional rights is multiply defective. The

contention that in order to protect his privilege

against self-incrimination he must forego his “ right

to speak to his sentencer” — or vice versa— errone

ously assumes a constitutional foundation for that

latter “ right.” This Court has often held that a con

victed defendant does not have the right to partici

pate personally in the sentencing process by advanc

2 3

ing considerations to which the sentencer should advert

in fixing punishment. To the extent such considera

tions can he presented, they may be presented through

other defense witnesses while the defendant relies on

his own privilege to remain silent.

Whenever an accused desires to be heard on some

issue relating to the finding o f guilt, he is vulnerable

to examination on any other relevant issue and he

assumes the risk that his testimony may prove self-

defeating. A defendant who wishes personally to tes

tify in favor of mitigating circumstances can do so at

his guilt trial but he has no more constitutional basis

for complaining that the punishment issue has not

been severed than does a defendant who would prefer

to confine his testimony to a one-sided disclosure on

an alibi issue. That the State could make available

procedures for separate trials on different issues does

not establish that the privilege against self-incrimi

nation compels this course.

The accused being tried for murder in a one-stage

trial faces the very same tactical pressures that inhere

in every criminal prosecution. In some circumstances

it may seem desirable to take the witness stand and

in others it may not. As the Court’s guilty-plea cases

last Term demonstrate, the practical necessity o f mak

ing difficult choices in defending a criminal charge,

including a capital charge, does not establish that the

procedures which occasion the election impermissibly

burden the rights involved.

C. Nor is there substance to the arguments o f vari

ous amici that unitary trials unconstitutionally pre

2 4

vent the sentencing jury from obtaining access to

information needed for rational sentencing. The

States have the freedom to determine as a matter of

penal policy that the “ punishment should fit the

crime” and thus may authorize that sentence be fixed

in light of the circumstances o f the crime as developed

at trial. This Court has never held that the Constitu

tion requires consideration o f anything akin to a

pre-sentence report before a convicted murderer can

be sentenced.

The realities o f murder trials, in any event, show

that even where evidence related solely to penalty is

not admissible the jury receives a reasonably accurate

picture o f the defendant on trial. These background

details may come out in a variety o f ways but they

suffice to satisfy whatever minimum level of informa

tion might conceivably be argued to be indispensable

to intelligent sentencing.

Finally, there is considerable uncertainty about the

actual effect o f holding separate penalty hearings.

Various courts and commentators have suggested that

the procedure may generally operate to the disad

vantage of defendants because such a hearing does not

significantly enlarge the defendant’s ability to bring

favorable evidence before the jury but does open up

such critical areas as the accused’s prior criminal

record for exposure to the jury. It would thus be un

wise to hold that bifurcation is so great an improvement

over the present unitary trial system that due process

demands it, when it is possible that it encourages death

sentences.

25

A R G U M E N T

I

THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION DOES NOT REQUIRE THAT

STATE LEGISLATURES PRESCRIBE STATUTORY STANDARDS TO

GUIDE OR GOVERN THE JURY’S DETERMINATION OP SEN

TENCE IN A CAPITAL CASE

The petitioners in both cases argue that their death

sentences are constitutionally invalid. One claim, com

mon to both cases, rests on the fact that the statutes

under which they were tried and convicted for first

degree murder entrusted to the jury the decision

whether a death sentence should be imposed but did

not establish any explicit criteria for making that

decision. This absence o f statutory standards, they

argue, denies them due process and equal protection

of the law under the Fourteenth Amendment.

It is unclear whether petitioners contend that such

criteria would define the factors which the jury must

find to be present or absent in order to fix a capital

sentence, or would simply enumerate some considera

tions on which the jury should reflect. In either event,

it is our view that the United States Constitution does

not mandate the formulation o f any such criteria for

this purpose.

A . H IS T O R IC A L L Y , S E N T E N C IN G DISCRETION , W H E T H E R ENTRU STED TO

JU DGE OR J U R Y , I N C A P IT A L A N D N O N -C A P IT A L CASES, H A S N OT DE

PENDED O N LEGISLATIVE C RITERIA

1. Introduction: the attack on ustandar<Uess,'> sentencing in

these cases implicates all felony sentencing

In order to assess petitioners’ constitutional claims,

their actual context and likely implications should

26

be clear. Although the issue is narrowly cast as a chal

lenge to “ standardless” jury discretion in fixing the

sentence in a capital case, the arguments advanced in

support o f the position would seem to apply equally

to any sentencing, whether by a judge or by a jury,

and whether the offense is maximally punishable by

death, life imprisonment, or a variable term o f years.

Throughout our history, a developing penology has

tended to expand, rather than to contract, the dis

cretion given to the sentencing organ to deal with a

convicted felon. This Court expressly recognized this

historical experience in one of the eases which, we

believe, stands directly in the way o f petitioners’ con

tentions, Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949),

where the Court upheld a death sentence imposed by

a judge in the exercise o f discretion uncontrolled by

any statutory standards. The Court there noted an

important, and here pertinent, distinction between the

standards and procedures necessarily surrounding the

determination of guilt and the flexibility and discre

tion properly inhering in the sentencing process:

Tribunals passing on the guilt o f a defend

ant always have been hedged in by strict evi

dentiary procedural limitations. But both be

fore and since the American colonies became a

nation, courts in this country and in England

practiced a policy under which a sentencing

judge could exercise a wide discretion in the

sources and types o f evidence used to assist

Mm in determining the kind and extent of

punishment to be imposed within the limits

fixed bylaw. (337 U.S. at 246; footnotes omitted.)

27

The Court also observed that modern developments

like indeterminate sentences and probation “ have re

sulted in an increase in the discretionary powers ex

ercised in fixing punishments.” 337 U.S. at 249.

In a later case, the Court rejected a claim that a

sentencing judge had failed to accord due process of

law in electing to impose a death sentence after a

guilty plea, without making use of a procedure for

hearing evidence in aggravation or mitigation of

penalty; the procedure followed was found sufficient

because the penalty decision rested with the judge

“ in the exercise o f his sound discretion.” See

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576, 585 (1959).

Especially in setting prison sentences in non

capital cases, the range o f alternatives open to a

sentencing judge is even more expansive than in a

capital case, where the sharp distinction separating

the alternatives, life and death, unquestionably clari

fies and illuminates the choice to be made. Yet, even

in such cases, sentencing judges are for the most part

not provided with “ external legislative guidelines

which delineate sentencing factors and their relative

weight. ’ ’ 6

In recent years, there have been efforts on several

fronts to introduce comprehensive changes in the

present American sentencing structure, and among

the techniques proposed is legislative formulation of

the considerations that are to be weighed in deter

6 See Sentencing Disparity: Causes and Cures, 60 J. Crim.