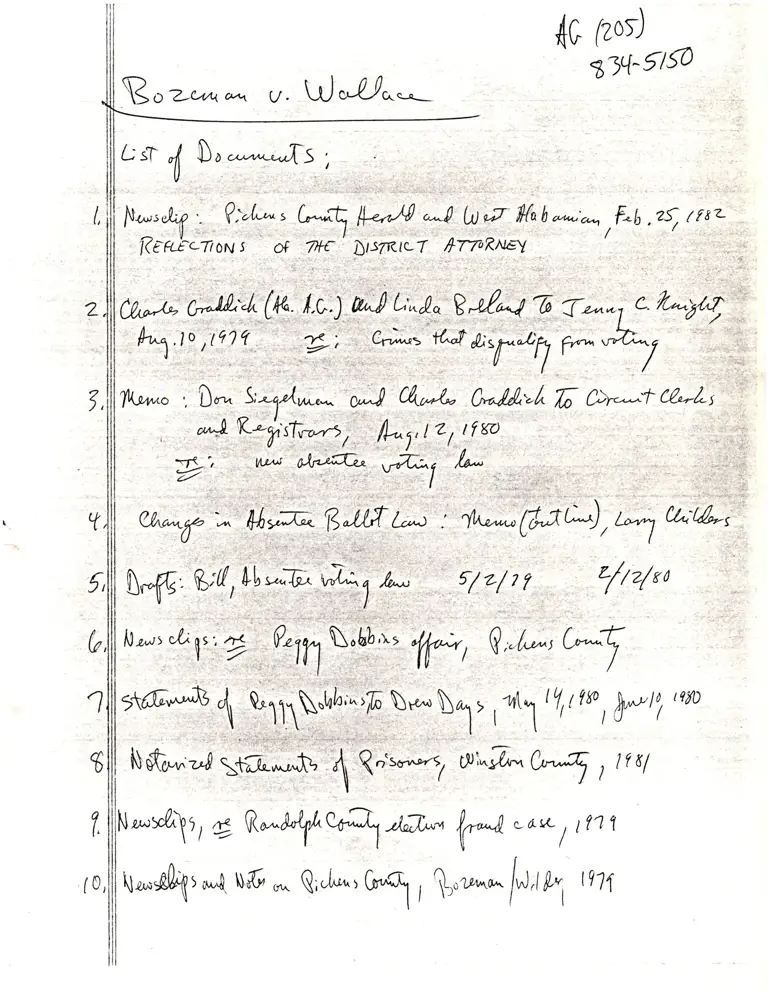

Attorney Notes

Working File

January 1, 1983 - January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Attorney Notes, 1983. 49ad12c2-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2b67a51d-3a8f-47e6-a943-f5a1b7b37535/attorney-notes. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

{c Bos)

3 j+5tt0

\3o ?-u.1aa'a "- UJ or'{Jn-,--

N-, Ail '. ?:,{^^, '' n lJ -.

Ke Fttc716* t of

5,

(/,

r\ry,{

N*rQltER*U#q /).e,""

Wv&LL,tt1

1

\*$qru*{ 116,^ QiJ,.,G,cl I t.r^^la,tW, tnf