Nixon v. Administrator of General Services Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nixon v. Administrator of General Services Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1976. ae3705ae-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2bbaec2d-2c16-4f4f-a71f-22ca8d9fafd5/nixon-v-administrator-of-general-services-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

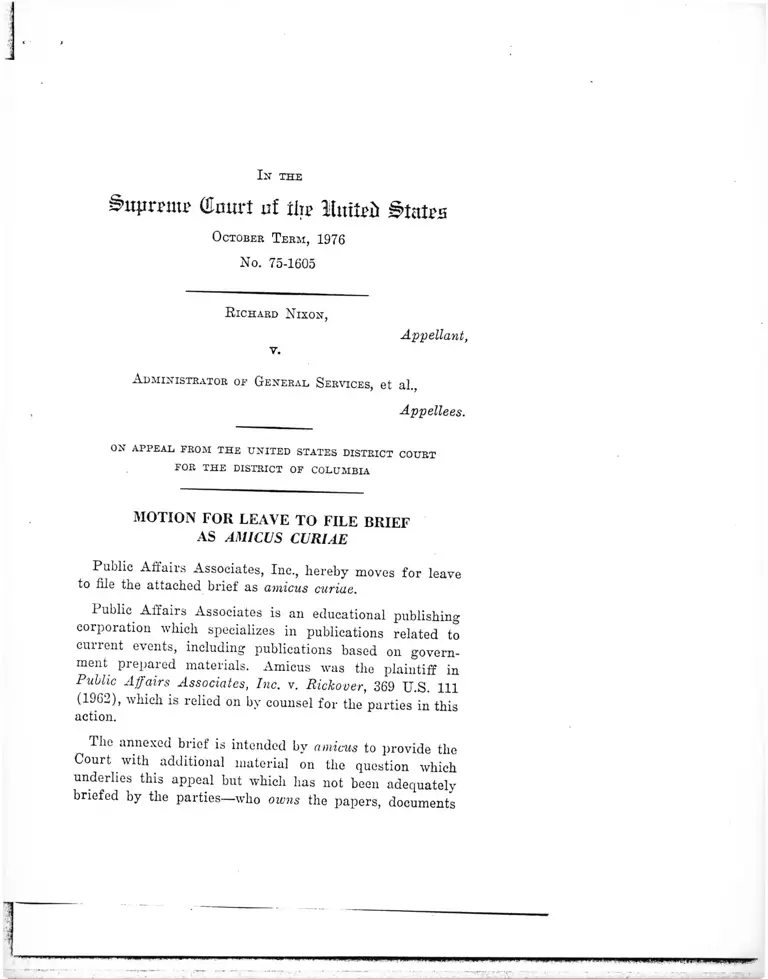

In the

S u p m u ? ffimtrt u f % llu itcii S ta te s

O ctober T e r m , 1976

No. 75-1605

R ich ard N ix o n ,

Appellant,

v.

A d m in istra to r of G en e r a l S ervices, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Public Affairs Associates, Inc., hereby moves for leave

to file the attached brief as amicus curiae.

Public Affairs Associates is an educational publishing

corporation which specializes in publications related to

current events, including publications based on govern

ment prepared materials. Amicus was the plaintiff in

Public Affairs Associates, Inc. v. Rickover, 369 U.S. 111

(1962), which is relied on by counsel for the parties in this

action.

The annexed brief is intended by amicus to provide the

Court with additional material on the question which

underlies this appeal but which has not been adequately

briefed by the parties—who owns the papers, documents

2

and other records generated within or received by the

office of the President. That issue was the subject of a

detailed and well reasoned opinion by the District Court

at an earlier stage of this litigation, Nixon v. Sampson,

389 F.Supp. 107 (D.D.C. 1975), which concluded that the

records, etc., at issue in this case were and always had

been the property of the United States. Notwithstanding

Rules 15(1) (a) and (h) and 40(1) (a), appellants did not

mention the existence of this opinion in either their Juris

dictional Statement* or Brief, or reproduce it in their

Jurisdictional Statement. The government’s brief refers

to the existence of “an opinion” at 389 F.Supp. 107, but

does not discuss its nature or relevance. Brief for the

Federal Appellees, p. 10.

Appellant asserts that he owns some 42,000,000 docu

ments and tapes, and that he therefore should be free to

destroy, alter, or sell them on the open market. Although

Judge Richey, below, concluded that these materials be

longed to the United States, the Solicitor has declined to

assert that the government owns the records or to discuss

the matter at all. We do not contend that the Solicitor

General’s silence on this issue is in any wav improper

On the contrary, we note that the Department of Justice

also declined an express invitation to take a position as

to whether the government owned the materials at issue

in Public Affairs Associates v. Richover, 3G9 U.S. I l l 113

A decision that the disputed records are the property

of̂ the United States will, for the reasons set out in our

brief,_ be dispositive of the issues presented by this appeal.

I f this appeal is affirmed on the more complex grounds

uie Jurisdictional Statement noted that the original agreement

» X U a T i ' X * ' t t A t ' nis,rator ™ repro<,n“ a * * 389

3

suggested by the Solicitor General, it will be but a prelude

to a new round of litigation between Mr. Nixon and the

General Services Administration regarding assertions of

privilege and claims for monetary compensation; a deci-

sion on the question of ownership will pretermit most such

litigation and issues. More importantly, such a decision

will bring to an end the surreptitious conversion of gov

ernment property by public officials at all levels. Although

the practices of outgoing Presidents and other federal

employees has varied widely over the years, permanent

employees of the executive branch have been uniformly

unwilling to protect the government files from such pillage.

In most cases the permanent employees aware of the

proposed removal of federal documents are subordinates

ot the officials taking the materials, and are naturally

reluctant, as are colleagues who may wish to engage' in

similar practices, to assert that the materials are gov

ernment property. Private parties not unwilling to make

such an assertion may lack the requisite standing. This

is one of the few circumstances in which the question of

ownership of presidential and other official papers is

squaieh pioscnted, and it should now be decided.

We are not insensitive to the fact that a decision on own

ership will, to some extent, touch on the practices of past

and present members of this Court. Were there other cir

cumstances in which the issue could be decided without that

complication, it might be wise to defer decision until such

a case arose, but any case presenting the issue of ownership

will have simliar ramifications. There is no alternative

judicial forum in which this difficulty will not exist. Com

pare Laird v. Tatum, 409 U.S. 824, S37-38 (1972) (Rchn-

quist, ,7.).

This Court has in recent years adopted a salutary prac

tice of requiring that a motion for leave to file a brief

4

amicus curiae be filed no later than the date on which the

brief for the side supported by the amicus is due. Rule

42(3) states that such a motion must be “ timely” , a require

ment consistent with the Court’s general practice but con

templating that the timeliness of a particular motion be

assessed in light of the specific circumstances involved. In

the instant case the amicus could not know that the Solici

tor General would decline to address the ownership issue

until after the government’s brief had been filed and the

date on which it was due had passed. In addition, on the

question of whether a former president can assert a privi

lege against the disclosure of official documents we are

opposed to the position taken by both the Solicitor General

and the appellants. Under the circumstances we believe

the instant motion is timely with the meaning of Rule

42(3).

W h e r e f o r e , Public Affairs Associates, Inc. respectfully

prays that this motion be granted and that the attached

brief be filed.

Respectfully submitted,

E ric Sou n affer

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

In the

i ’ltprrmr CEmtrt nf tlir luitrii Btatvs

O ctober T e r m , 1976

No. 75-1605

R ich ard N ix o n ,

v.

Appellant,

A d m in istra to r of G en era l S ervices , e t al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from t h e u n it e d states d istrict court

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF

PUBLIC AFFAIRS ASSOCIATES, INC.

ARGUMENT

I.

The Disputed Presidential Records, etc., Are the

Property of the United States.

The central issue underlying this appeal is whether ap

pellant owns all or any of the materials placed in the per

manent custody of General Services Administration by

the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation

Act, Certain materials left by appellant in the White

House and temporarily held by the appellees are not cov-

eied b\ (lie Act and are, subject to appropriate procedures

to separate them from the other items, available to up-

2

pellant. Possession and control is permancntlv vested in

the Administrator only of “ the Presidential historical mate

rials of Richard M. Nison” . Although “ historical mate

rials” is broadly defined by 44 U.S.C. § 2101, the qualifica

tion “Presidential” excludes from the Act objects or docu

ments that deal exclusively with appellant’s personal life,

such as notes from or discussions with his wife and daugh

ters, his responsibilities as a leader of the Republican

Party, such as memoranda regarding internal party pol

itics, or other activities unrelated to his official respon

sibilities and activities as President of the United States.

The only materials to be retained by the Administrator are

those relating to the conduct of government business and

the exercise by appellant of his duties under the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States. Appellant asserts that

these records and objects are his personal property, and it

is only as to them that the dispute regarding ownership

exists.

The materials now claimed by appellant to be his per

sonal property were indisputably the property of the

United States at one time. Certainly that was the case,

as to documents, when the millions of sheets of paper were

purchased with government funds. Thereafter the sheets

were used to record government business by being placed

in government-owned typewriters, typed by government-

paid secretaries who typed words written by other govern

ment employees, xeroxed, read, edited and signed by other

government employees, and ultimately placed in govern

ment-owned filing cabinets by government-paid clerks.

Appellant, who personally saw less than 1% of the result

ing millions of documents, and wrote even fewer, asserts

that, sometime between this initial acquisition and the date

of his resignation as President, title to all the materials

v as transferred from the United States of America to

3

him. Precisely when, where, and how this transfer of title

is alleged to have occurred is not clear.

Tins assertion is inconsistent on its face with two sep

arate and unequivocal provisions of the Constitution. Sec

tion 3 of Article IV provides that “ The Congress shall have

the Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and

Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property

belonging to the United States.” The authority to sell or

give away government property is exclusively in the hands

of Congress; the President and other officials of the execu

tive bianch cannot impair government ownership of gov

ernment property without express statutory authorization.

Thus, unlike the ordinary rule regarding real or personal

property, federal title cannot be lost through abandonment

or through acquiescence by executive officials not acting

under congressional mandate.1 Similarly, absent an ex

press statutory transfer of specilic property to one or all

formci 1 lCsidents, title thereto cannot be acquired by a

species of historical adverse possession. Congress has pro

vided substantial sanctions for federal employees who con

vert or remove any record, document or other thing of

value belonging to the United States. 18 U.S.C. §§ 641, 2071.

Section 1 of Article II, generally known as the Emolu

ments Clause, provides that “The President shall at stated

times, receive for his Services a Compensation, which shall

neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for

which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive

within that Period any other Emolument from the United

States, or any of them.” The salary of the President, at

the beginning of the term for which appellant was elected,

1 Beaver v. United States, 350 F.2d 4 (,9th Cir 19G5) cert do

nred 383 U.S. 937 (I960); United States v P ennsyLnlaetc

Dock m v m (0th Cir. 1921); VnitcdStales

84 ?-S»PP- (D.N Mex. 1900) ; United States v. City of Colum

bus, ISO F.Supp. 77o, 777 (S.D. Ohio 1959). '

was $200,000 a year. 3 U.S.C. § 102. The Emolument

Clause would clearly be violated if a President were per

mitted to augment his statutory salary by seizing title to

any number of “presidential documents” , whose creation,

assemblage, number and dollar value were largely con

trolled by the President himself.

The conduct of past Presidents does not, we believe,

support appellant’s claim of ownership. Past Presidents

have frequently insisted publicly that officially generated

papers were government property. In 1782 Reverend

William Gordon, then at work on a history of the nation’s

origin, wrote to General Washington seeking access to

the latter’s Revolutionary War records. Washington de

clined to make the records available on the ground that

they were public property and only Congress could open

them for private use.

“ [T]he Papers of the Commander-in-Chief . . . I con

sider as a species of Public property, sacred in my

hands . . . . When Congress then shall open their

registers, and say it is proper for the Servants of the

public to do so, it will give me much pleasure to afford

all the Aid to your labors and laudable undertaking

which my papers can give; ’til one of those periods

arrive I do not think myself justified in suffering an

inspection of, and any extracts to be taken from my

Records.” -

President Roosevelt in 1941 described the White House

papers as “ the people’s record” and announced that they

would be placed, on the completion of his presidency, in

" J.C.. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from

Tiie Original Manuscript Sources, v.25, pp. 288-89 (1931-40). In

1783 Washington again wrote Gordon assuring him that. “ All my

Records and Papers shall be unfolded” when “ the Sovereign

Power” authorizes it. Id., v. 27, p. 52.

5

a government authorized library in Hyde Park.3 4 Roose

velt’s written instructions contemplated that the library

and its contents would become part of the National A r

chives, which is what occurred. In 1947 the Christian

Science Monitor described the views of President Truman

on this subject:

President Truman plans to set a precedent for Presi

dents. He will not, repeat not, take with him his state

papers when he leaves the White House. . . . The

President feels strongly about this; he has for a long

time. The public papers of any top official, from the

President on down, should remain the property of the

government, he holds.'*

On September 16, 1974, President Ford announced a simi

lar position regarding the papers of his presidency:

As far as I am personally concerned, I can see a

legitimate reason for Presidential papers remaining

the property of the government. . . . In my own case, I

made a decision some years ago to turn over all of

my Congressional papers, all of my Vice Presidential

papers to the University of Michigan archives. As

far as I am concerned, whether they go to the archives

for use or whether they stay in the possession of the

government, I don’t think it makes too much difference.

I have no desire personally to retain whatever papers

come out of my administration.” 5

3 The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, p.

(i30 (1941) ; II.G. Jones, The Records of a Nation, 157, 162 n ’ 25

(1969).

4 January 29, 1947.

3 Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, September 23

1974, p. 1160.

6

The actions of past Presidents are more varied, and

their precedential significance obscured by the lack of rec

ords of what occurred and why, and by the absence of an

officially designated depository for the systematic reten

tion and preservation of presidential documents. After

leaving the Presidency, for example, George Washington

wrote to the Secretary of the Treasury about the need of

facilities “ for the security of my Papers of a public nature”

and engaged in correspondence with the Secretary of War

regarding suitable “ accommodation and security of my

Military, Civil and private Papers” . Since provisions for

official storage were never made, and Washington had no

choice but to leave them in the custody of his heirs.6 Pres

ident Jefferson “ deposited in the various departmental

offices— State, Treasury, War, Justice, and Post Office—

every document having any relation to the conduct of pub

lic business or being in any sense official in nature” ,7 but

owing to the informal practices of the era many of these

documents were later acquired by private collectors. There

after, in the continuing absence of any specifically desig

nated depository, some Presidents left official documents

in the possession of whichever department they thought

most likely to preserve them,8 while others took with them

some documents the number and nature of which is not

known. Beginning about 1905, when the Library of Con

gress intensified its interest in assembling and preserving

presidential papers, large numbers of such documents were

deposited with the Library by former Presidents Theodore

Roosevelt, Taft and Coolidge and the heirs of Presidents

6 J.C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from

the Original Manuscript Sources, v. 27, p. 155, v. 32 pp 15 41

v. 35, pp. 430-31 (1931-40).

7 Nixon v. Sampson, 3S9 F.Supp. 107, 141 (D .D.C. 1975).

8 See Exhibit A A , p. v ; Exhibit BB, p. vii.

7

Y an B^ ren’ Wllliam Henry Harrison, Polk, Lincoln,

rant Garfield, Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, McKinley

and Wilson.3 Since the adoption of the National Archives

Act m 1934 every former President has placed such rec

ords as he removed from the White House in an officially

designated library maintained by the National Archives

and Records Service. These varying practices suggest

not a uniform assumption that a former President owned

whatever materials he could physically remove from the

ntc House, but differing efforts to find suitable deposi

tories for documents recognized to be public in nature.

. Even if tllG record ^voaled a pattern of Presidents act

ing as if they owned such papers, selling or copyrighting

em foi financial gam, that would not constitute the sort

of practice deserving of precedential significance, for the

instances of such conduct have been essentially surreptitious

m nature. The public was not in the past aware whether, and

even now the parties are in dispute as to the extent to

which, former Presidents have been treating officially gen

erated papers as their private property. The practice of

some public officials of donating public papers back to the

government, or to other institutions, in return for a tax

deduction caused a public scandal of major proportion

when it was first exposed in 1969 by the Wall Street Jour-

I-* ’ ° Both tlie 0̂ Congress, the recipient of these

donations” , and over a dozen alleged donors refused to

disclose whether or which federal officials had engaged in

such a practice. Appellant never publicly disclosed that

he had used Ins Vice-Presidential papers in this manner,

and the country only learned of it through a story in the

Providence Journal on October 3, 1973. The Treasure De-

of thoTlouse0'C o m 'S >.ntial pibl‘irics hy “ Subcommittee

1st Sm, pp 39 44 (1955) Gover" mc" t Options, 84th Cong.,

May 22, I960 ; 115 Cong. Rec. 20462-63 (1969).

8

partment employee responsible for that disclosure was dis

missed; the use of those papers to pay virtually no income

taxes in 1970 and 1971 was a subject of the subsequent

House impeachment inquiry, led to criminal convictions

of an appraiser and attorney involved, was subsequently

disapproved as inconsistent with the Internal Revenue

Code by the Treasury Department. Practices of the sort

which have survived only when hidden from the scrutiny

of public opinion are not the “ deeply embedded traditional

ways of conducting- government” to be relied on in con

struing the Constitution. Youngstoivn Sheet & Tube Co. v.

Saivyer, 343 U.S. 579, 611 (1952).

As Judge Richey noted below, Folsom v. Marsh, 9 Fed.

Cas. No. 4,901 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841), expressly noted that

any rights of a former President to papers prepared or

received by him were subservient to the rights and inter

ests of the government, and Folsom thus supports the

constitutionality of the Presidential Recordings and Mate

rials Preservation Act. 389 F.Supp. at 139-140. Insofar

as Justice Story’s opinion in Folsom concludes that a for

mer President has a fungible property right, as against

other individuals, in such papers, we believe Justice Story’s

personal interest and involvement in the publication at

issue in Folsom was so substantial as to vitiate any prece

dential significance of that decision.

Folsom concerned the validity of a copyright of a multi

volume collection of George Washington’s presidential and

other papers, edited by Jared Sparks and published by

Charles Folsom. In 1826 Sparks approached Justice Bush-

rod Washington, the former President’s nephew who was

in possession of many of the latter’s letters, etc., and sought

his cooperation in assembling the proposed collection. In

soliciting Justice Washington’s cooperation, Sparks turned

for aid to Justice Story, whom lie had known since the

9

early lS20’s. In a letter of January 16, 1826, about bis

plans for the project, Sparks advised Justice Washington

“ For further information as to my purposes and qualifi

cations, permit me . . . to refer you to Judge Story, with

whom I have conversed on this subject, and who manifests

a lively interest in the plan of collecting into one body all

the writings of General Washington” .11 On January 20,

1S26, Justice Story wrote to Sparks:

I think your project of collecting the works of Wash

ington a noble project and deserving of universal en

couragement. I know not into whose hands the task

could better have fallen. Your letter to Judge Wash

ington is excellent both in matter and manner, and

develops your plan in such a way as cannot but com

mand approbation.12

On January 26, 1826, Sparks wrote a second letter, this

one to Justice Washington and Chief Justice Marshall,

which Story delivered on Sparks’ behalf.13 14 On February

23, 1826, Justice Story reported to Sparks with regret that

“Judge Washington does not incline to favor your proj

ect.” u

When Washington remained unresponsive, Sparks again

took up the matter with Justice Story, advising him of his

determination to proceed anyway, explaining in a letter

of March 4, 1826, that the publication might still be pos

sible without Bushrod Washington’s aid. “All the impor

tant materials may be obtained from other quarters, though

n H .B . Adams, The Life and Writings of Jared Sparks, v. I, p

401 (1S93).

12 Id., pp. 401-02.

13 See id., pp. 404, 405.

14 Id., pp. 402-03.

10

with '‘Teat trouble. 'Washington’s public letters and papers

are the property of the nation.” 15 After assembling a mas

sive number of these papers, largely from oflieial tiles,

Sparks again wrote to Justice "Washington, threatening to

publish without his aid, but promising a share of the profits

if he were granted access to the documents in Justice

Washington’s possession.16 Eventually Sparks was per

mitted to use these materials in return for an agreement

that the resulting profits were to be divided evenly between

Sparks, Justice Washington, and Chief Justice Marshall.17 *

Justice Story was substantially involved thereafter in

the commercial aspects of the publication of President

Washington’s papers. On June 1, 1827 he wrote to Sparks

of his support for the project and suggested another source

of profit. “ What do you mean to do as to England ? You

ought, if possible, to secure some of the profits of an edi

tion there. On this subject we must talk . . . . ” 16 Sparks’

diary for March 6, 1827, notes that after meeting with

Justice Washington to discuss their contract he

passed half an hour with Judge Story. lie has taken

an ardent interest in this work from the beginning and

has assisted me much in bringing the matter to its

present issue. He advises by all means to make pro

vision for a sale in England— thinks many will sell and

that a vigorous effort should be made to extend the

circulation there.19

15 Id., p. 404.

10 Id., p. 409.

_ 17 “Articles of Agreement, March 7, 1S27” , in Manuscript Collec

tion of Morristown, New Jersey, National Historical Park.

ls H .B . Adams, The Life and Writings of Jared Sparks, v. II

p. 205 (1893).

19 Id., p. 8. Sparks and Story discussed the editing of the papers

on January 20, 1827. Id., p. 3.

11

To promote advance orders for the forthcoming compila

tion, Justice Story and Sparks cooperated in a series of

letters from Sparks to Justice Story which described the

project and were used to obtain press coverage of the

letters. The letters appeared in the summer of 1S27 in the

nation’s leading newspapers, including the front page of

the National Intelligencer20 owned by the Supreme Court

printer, and caused Justice Story “unmixed satisfaction.” 20 21

Justice Story’s relationship with Sparks and Folsom did

not end with the publication of Washington’s papers. In

1829 Story became a part-time professor of law at Har

vard, where he continued his close friendship with Sparks,

who also served on the faculty, and presumably remained

in contact with Folsom, who was Harvard’s printer.22

Story, Sparks and Folsom still held these positions in 1841

when Justice Story decided Folsom v. Marsh. The decision

in that case was based on a factual record developed by one

George Hillard as Master in Chancery j Hillard was a paid

contributor at the time to a series edited by Sparks, the

Library of American Biography.23

Under these circumstances the Court should not attribute

to Folsom v. Marsh the precedential significance that would

20 The letters are set out in id., pp. 236-264. After their publica

tion Justice Washington wrote to Sparks “Your letters to Mr. Jus

tice Story have excited but one sentiment everywhere so far as I

can understand, and that, the most favorable to your undertaking.”

Id., p. 266. The letters were later reprinted in a pamphlet winch

was used as a prospectus. Id., p. 236.

21 Id,, p. 265.

22 See A. Johnson and D. Malone, Dictionary of American Bi

ography, v. I l l , p. 493, v. IX , pp. 106, 431-33 (1930).

•3 G. Hillard, Captain John Smith (c. 1840). Hillard was a con

tributor to the North American Review edited by Sparks, as was

Story. A. Johnson and D. Malone, Dictionary of American B i

ography, v. V , p. 50 (1930) ; H .B. Adams, Life and Works of

Jared Sparks, v. I, p. 311 (1893).

12

be due the decision of a judge who, unlike Justice Story,

was not an active instigator and proponent of the work

whose copyright was challenged, was not a personal friend

of all the parties in interest on one side, and did not have

extensive personal knowledge of and participation in the

events giving rise to publication.

Since the ownership asserted by appellant is not acquired

in any of the manners, such as purchase or bequest, known

to the common law, there seems no intelligible limit on

what he owns or could acquire as President. Appellant

asserts his property includes everything in the White

House Office, regardless of what it is or how it got there,!24

and appears unwilling to accept ownership limited to docu

ments he wrote, documents he signed, documents he read,

documents he knew existed, documents prepared in the

White House, or documents involving privileged material

Sustaining such an assertion would be an invitation to a

President to direct that documents be transferred to the

White House Office in order to convert them into his per

sonal property. Even were the scope of ownership more

restricted, a President could direct government employees

to create documents and other materials for his personal

use and ultimate removal from the White House. The for

mer Special Prosecutor has suggested that the tapes in

this case were made for just such personal gain by appel

lant.” Members of Congress have upon occasion copy

righted materials, or charged fees for giving speeches

written by congressional employees on office time.

The principle of Ownership asserted by appellant is not

limited to former Presidents. Appellant earlier claimed

similar ownership of his Vice Presidential papers, and here * *

-4 Brief for Appellant, pp. 25-31.

L. Jaworski, The Right and The Power, p. 272 (1976)

13

suggests officially prepared documents are also the per

sonal property of congressmen and members of this Court.26

Recently government documents have been removed for

Personal use, presumably under a similar claim, by White

House aides and cabinet and sub-cabinet officials.27 In

eailiei yeais similar assertions of ownership of officially

piepared papers or their contents have been made, gen

erally unsuccessfully, by a Vice-Admiral,28 * a Senator,23

a court reporter of written decisions,30 a sailor who tra

veled with Commodore Perry to Japan,31 32 and an assistant

to the Secietary of the Interior.3- Recognition of such

claims would seriously impair the completeness and in

tegrity of government files, and would ultimately embroil

the courts in disputes as to whether, for example, a memo

randum is "owned” by the author, the intended recipient,

other readers, the person or persons discussed, or any of

the supervisors of these individuals.

I he public interest requires that a former President or

other departing officials not be free to remove at will files

kept in or for their offices. The history of this intermit

tent practice reveals the extent to which it can impede the

operations of the national government. Among the docu

ments which thus disappeared with the outgoing officials,

Report of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation,

Examination of President Nixon’s Tax Returns for 1969-79 n 1

(1974) ; Brief for Appellant, p. 92.

‘ 7 Brief of Appellees The Reporters Committee for Freedom of

the Press, p. 38, n. 30.

-!> Public Affairs Associates v. Kickover, 369 U.S. I l l (1962).

3 9 5 * 9 4 7 ^ F '2d 701, 708 (D 'C' Cir' ) cert dcnied

20 Wheaton v. Peters, 8 Peek. (33 U.S.) 591, 660 (1834).

31 Heine v. Appleton, 11 F.Cas. 1031 (C .C.D.N.Y. 1857).

32 Sawyer v. Crowell, 46 F.Supp. 471 (S.D .N .Y. 1942) aff’d 149

F.2d 497 (2d Cir. 1944).

$

feu

14

and whose absence led to serious problems, were tbe offi

cial copy of tbe Treaty of Versailles,33 tbe sole copy of a

State Department cable regarding assurances to France

during tbe 1956 Suez Crisis,34 and tbe only copy of a memo

randum from Secretary of State Dulles assuring the

Israelis of aid if the Egyptians blockaded tbe straits of

Tiran.35 American officials only learned of the latter docu

ment when it was relied on by the Israeli Foreign Minister

during negotiations with President Johnson on tbe eve of

tbe 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Even where incumbent officials

know documents exist, their predecessors are not always

willing to supply them; thus appellant refused to permit

examination of any relevant presidential papers by Presi

dent Ford’s Commission on CIA Activities within tbe

United States.36 These problems are inevitable because,

once they leave office, the concerns of former Presidents

and other former officials are not solely, or primarily, the

effective conduct of government affairs by their succes

sors, but foreseeably and not improperly include protect

ing their standing in history and advancing the political

and financial interests of themselves and their party.

33 B. Murray, “How Harding Saved The Versailles Treaty”’,

American Heritage, pp. 66-67 (December, 1968).

34 “ Governing in the Dark” , Washington Star, January 16, 1977.

36 Id.

36 Report of the Commission on CIA Activities Within the

United States, p. 172 (1975).

ii m il mum-

15

II.

The Presidential Recordings and Materials Preserve

tion Act Is Constitutional.

The government’s ownership of the materials conveyed

to the Administrator by the challenged statute is, we be

lieve, dispositive of the other issues raised by appellant.

Such ownership necessarily carries with it the right of offi

cials of the executive branch to hold, examine, and use

the government property in question, and appellant could

have no privilege exercisable against the lawful owners

of the disputed papers and tapes. To the extent that an

incumbent President concludes that public disclosure of

these or any other documents is consistent with or required

in the national interest, his decision cannot be reviewed

or countermanded by any of his predecessors. Appellant,

having co-mingled his own property, personal and political"

with that of the government cannot reasonably object if

responsible government officials, at the behest of Congress,

seek to examine the resulting admixture to extract what

is public property. The Presidential Recordings and

Materials Preservation Act does not single out appellant’s

property, alone among all Presidential papers, for expro

priation^ the property interest appellant asserts was

neither lus nor that of bis predecessors or successors. To

the extent that the Act guarantees appellant access to and

copies of all the disputed papers it confers upon him le«-al

lights which he did not previously enjoy.

That documents produced or received bv officials h,

the executive or, for that matter, legislative or judicial

branches, are not their personal property does not mean

^ at the custody and secrecy of such materials cannot be

controlled, or that public access must bo granted prema-

- . -j q.c-

i

i

/

*

2if

t

\

5

?

V-

i•s-

J

I

j

*

I n t h e

Supreme ©curt nf tlip lilniteit Sta tes

October T eem, 1976

. No. 75-1605

R ichard Nixon,

v.

Appellant,

A dministrator of General Services, et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

i

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS

ASSOCIATES, INC.

E ric Schnappee

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

e

r~" J.i>4*l,i ^ ,Jt,,MU.i i p p m m m