Baskin v. Brown Judgment

Public Court Documents

May 20, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baskin v. Brown Judgment, 1949. 96027ee1-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2bfdb832-42fc-4c5f-b098-274604fb20a9/baskin-v-brown-judgment. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

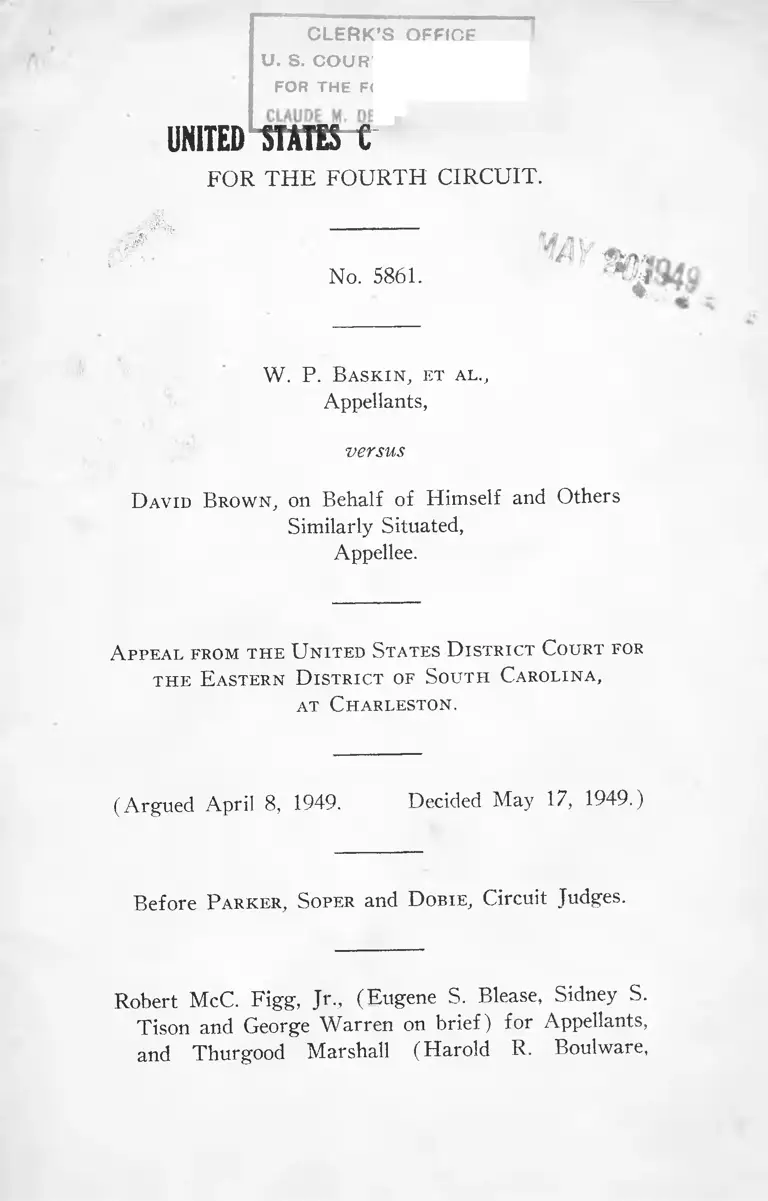

UNITED

CLERK’S OFFICE

U. S. C O U R T O F A P P E A L S

FOR THE FOURTH C IR C U IT

STATES C

FO R T H E FO U R TH CIRCUIT.

No. 5861.

W. P. B a s k in , et a l .,

Appellants,

versus

D avid B row n , on Behalf of Himself and Others

Similarly Situated,

Appellee.

A ppea l from t h e U n it ed S tates D ist r ic t Court for

t h e E astern D ist r ic t of S o u t h C a ro lin a ,

at C h a r lesto n .

(Argued April 8, 1949. Decided May 17, 1949.)

Before P a rker , S oper and D obie , Circuit Judges.

Robert McC. Figg, J r | (Eugene S. Blease, Sidney S.

Tison and George W arren on brief) for Appellants,

and Thurgood Marshall (Harold R. Boulware,

Robert L. Carter and Constance Baker Motley on

brief) for Appellee.

P a r k e r , Circuit Judge:

This appeal presents another chapter in the effort

to exclude Negro citizens from any effective participa

tion in elections in South Carolina, where the vote in

the Democratic Primary controls, to all practical intents

and purposes, the choice in general elections. Prior to

the decision in Smith v. Allwright 321 U. S. 649,

Negroes were excluded from voting in the Democratic

Primary in South Carolina, which was conducted pur

suant to state law. Following the decision in that case,

which upheld the right of Negroes to vote in primary

elections, the Governor of South Carolina convened the

Legislature in special session and recommended that all

primary laws of the state be repealed, with the avowed

purpose of preventing Negroes from participating in the

Democratic primaries. Pursuant to this recommenda

tion the primary laws were repealed and the Democratic

primaries were conducted thereafter under rules pre

scribed by the Democratic Party of South Carolina but

in the same manner and in such way as to produce the

same results as when conducted under state law. In

Elmore v. Rice 72 F. Supp. 516, those conducting these

primary elections were enjoined from denying to Negro

citizens the right to vote therein; and this was affirmed

by us on appeal in Rice v. Elmore 4 Cir. 165 F. 2d 387,

where we gave most careful consideration to the ques

tions involved. Certiorari to review our decision was

denied by the Supreme Court. 333 U. S. 875.

Following the denial of certiorari in Rice v.

[ 3 ]

Elmore, the Democratic Party of South Carolina

adopted rules under which control of the primaries in

that state was vested in clubs to which Negroes were

not admitted to membership, and voting in the prim

aries was conditioned upon the voter’s taking an oath

that he believed in social and educational separation of

the races and was “opposed to the proposed Federal

so-called F.E.P.C. law”. Negroes desiring to vote in

the primaries were required, in addition, to present

general election certificates, a requirement not exacted

of white voters.

Upon adoption of the rules mentioned, this suit was

instituted against officials of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina to protect the right of Negro citizens

to participate in the Democratic prmaries; and the right

with respect to the approaching primary was protected

by an interlocutory injunction (Brown v. Baskin 78 F.

Supp. 933) which was made permanent on final hearing.

Brown v. Baskin 80 F. Supp. 1017. Appeal has been

taken from this final decree, which enjoins defendants

from refusing to enroll Negroes as members of Demo

cratic Clubs or denying them full participation in the

Democratic Party on account of race or color, from

enforcing the rule requiring Negro electors to present

election certificates as a prerequisite to voting unless

the same requirement is applied to other persons, and

from requiring the taking of the oath to which refer

ence has been made. The appeal before us asks that we

reconsider our decision in Rice v. Elmore, supra, and

attempts to defend the limitation of membership in

Democratic Clubs and the oath required of voters in

party primaries on the ground that these are matters

for the party with which the state has no concern.

We see no reason to modify our holding in Rice v.

Elmore. On the contrary, we are convinced, after fu r

ther consideration, that the decision in that case was

entirely correct: and little need be added to our opinion

there to dispose of every question that is here pre

sented. The gist of that decision was that primaries,

under modern conditions, are a part of the election

machinery of the state, and that a state cannot, by

allowing a political party to take over this part of its

election machinery, avoid the provisions of the Con

stitution forbidding racial discrimination in elections,

and thus deny to a part of the electorate, because of

race or color, any effective voice in the government of

the state. After reviewing and analyzing the applicable

decisions of the Supreme Court, we summed up the

rationale of our decision in the following language:

“An essential feature of our form of gov

ernment is the right of the citizen to participate

in the governmental process. The political phil

osophy of the Declaration of Independence is

that governments derive their just powers from

the consent of the governed; and the right to a

voice in the selection of officers of government

on the part of all citizens is important, not only

as a means of insuring that government shall

have the strength of popular support, but also as

a means of securing to the individual citizen pro

per consideration of his rights by those in power.

The disfranchised can never speak with the same

force as those who are able to vote. The Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments were written

into the Constitution to insure to the Negro, who

had recently been liberated from slavery, the

equal protection of the laws and the right to full

participation in the process of government. These

amendments have had the effect of creating a

federal basis of citizenship and of protecting the

rights of individuals and minorities from many

[ 5 ]

abuses of governmental power which were not

contemplated at the time. Their primary pur

pose must not be lost sight of, however; and no

election machinery can be upheld if its purpose or

effect is to deny to the Negro, on account of his

race or color, any effective voice in the govern

ment of his country or the state or community

wherein he lives.

“The use of the Democratic primary in con

nection with the general election in South Caro

lina provides, as has been stated, a two step elec

tion machinery for that state; and the denial to

the Negro of the right to participate in the

primary denies him all effective voice in the gov

ernment of his country. There can be no ques

tion that such denial amounts to a denial of the

constitutional rights of the Negro; and we think

it equally clear that those who participate in the

denial are exercising state power to that end,

since the primary is used in connection with the

general election in the selection of state officers.”

In the light of what was there said, there can be no

question but that the injunction here was properly

granted. By placing the control of the primaries in

Democratic Clubs, membership in which is confined to

white persons, and by requiring of voters in the prim

aries an oath which would effectually exclude Negroes,

those in control of the Democratic Party are attempting

to do by indirection that which we held in Rice v. El

more they could not do, i.e. deny to Negro voters

because of race and color the right to any effective voice

in the government of the state. The devices adopted

showed plainly the unconstitutional purpose for which

they were designed; but, even if they had appeared to

be innocent, they should be enjoined if their purpose or

effect is to discriminate against voters on account of

race. Davis v. Schnell 81 F. Supp. 872, aff. 69 S.Ct.

749; Yick Wo v. Hopkins 118 U. S. 356, 373. As we

said in Rice v. Elmore, supra:

“Even though the election laws of South

Carolina be fair upon their face, yet if they be

administered in such way as to result in persons

being denied any real voice in government be

cause of race and color, it is idle to say that the

power of the state is not being used in violation

of the Constitution. As said in Yick Wo v.

Hopkins 118 U.S. 356, 373, 374, 6 S.Ct. 1064,

1073, 30 L. Ed. 220, “Though the law itself be

fair on its face, and impartial in appearance, yet

if it is applied and administered by public author

ity with an evil eye and an unequal hand, so as

practically to make unjust and illegal discrimi

nations between persons in similar circumstances,

material to their rights, the denial of equal jus

tice is still within the prohibition of the Constitu

tion”.

In Davis v. Schnell, supra, the three judge District

Court, in holding unconstitutional the Boswell amend

ment to the Constitution of Alabama prescribing an

educational qualification for suffrage designed to dis

franchise Negro voters, said:

“It, thus, clearly appears that this Amend

ment was intended to be, and is being used for

the purpose of discriminating against applicants

for the franchise on the basis of race or color.

Therefore, we are necessarily brought to the con

clusion that this Amendment to the Constitution

of Alabama, both in its object and the manner of

its administration, is unconstitutional, because it

violates the Fifteenth Amendment. While it is

true that there is no mention of race or color ins

the Boswell Amendment, this does not save it.

The Fifteenth Amendment ‘nullifies sophisticated

[ 7 ]

as well as simple-minded modes of discrimina

tion’, and ‘It hits onerous procedural require

ments which effectively handicap exercise of the

franchise by the colored race although the

abstract right to vote may remain unrestricted

as to race.’ ”

The argument is made that a political party does

not exercise state power but is a mere voluntary organ

ization of citizens to which the constitutional limitations

upon the powers of the state have no application. This

may be true of a political party which does not under

take the performance of state functions, but not of

one which is allowed by the state to take over and

operate a vital part of its electoral machinery. When

the organization of the party and the primary which it

conducts are so used in connection with the general

election that the latter merely registers and gives effect

to the discrimination which they have sanctioned, such

discrimination must be enjoined to safeguard the elec

tion itself from giving effect to that which the Con

stitution forbids. Courts of equity are neither blind

nor impotent. They exercise their injunctive power to

strike directly at the source of the evil which they are

seeking to prevent. The evil here is racial discrimina

tion which bars Negro voters from any effective partici

pation in the government of their state; and when it

appears that this discrimination is practiced through

rules of a party which controls the primary elections,

these must be enjoined just as any other practice which

threatens to corrupt elections or divert them from their

constitutional purpose.

Appellants also ask reversal because the trial judge

refused to disqualify himself from hearing the case after

an affidavit charging him with bias and prejudice had

[ 8 ]

been filed. The facts set forth in this affidavit, however,

show no personal bias on the part of the judge against

any of the defendants, but, at most, zeal for upholding

the rights of Negroes under the Constitution and indig

nation that attempt should be made to deny them their

rights. A judge cannot be disqualified merely because

he believes in upholding the law, even though he says so

with vehemence. Personal bias against a party must be

shown. Berger v. United States 255 U. S. 25; E x

Parte American Steel Barrel Co. 230 U. S. 35; Henry

v. Speer 5 Cir. 201 F. 869; Saunders v. Piggly W iggly

Corporation 1 F. 2d 582; Craven v. United States 1 Cir.

22 F. 2d 605, 607-608. As was well said in the case last

cited:

“ ‘Personal’ characterizes clearly the pre

judgment guarded against. It is the significant

word of the statute. It is the duty of a real

judge to acquire views from evidence. The

statute never contemplated crippling our courts

by disqualifying a judge, solely on the basis of a

bias (or state of mind, 255 U.S. 42, 41 S.Ct.

236, 65 L.Ed. 481) against wrongdoers, civil or

criminal, acquired from evidence presented in the

course of judicial proceedings before him. Any

other construction would make the statute an in

tolerable obstruction to the efficient conduct of

judicial proceedings, now none too speedy or

effective.”

There was no error and the decree appealed from will

be affirmed.

Affirmed,

J true copy.

Tnt*.

___ Clark

U. S. Court of Appeals

far the 4th Circuit,

USCA—2033—6-18-48—75