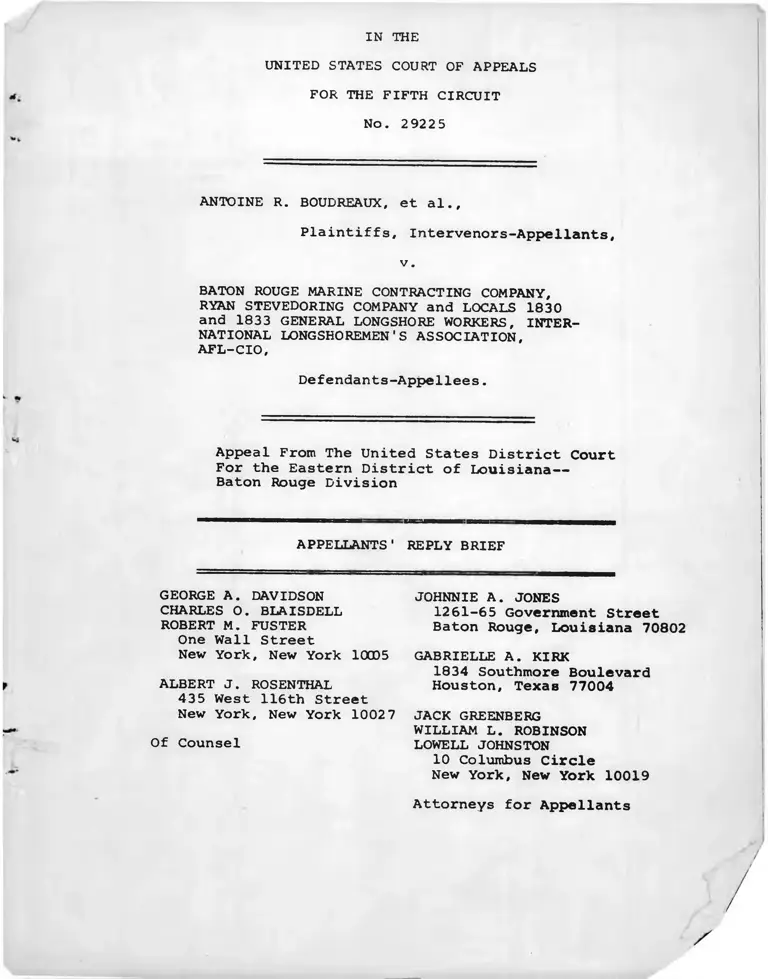

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Company Appellants' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

June 26, 1970

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Company Appellants' Reply Brief, 1970. ca0e1e35-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2c323665-14fb-4e91-9c3e-5c4919cc5ddc/boudreaux-v-baton-rouge-marine-contracting-company-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 29225

ANTOINE R. BOUDREAUX, et al.,

Plaintiffs, Intervenors-Appellants,

v.

BATON ROUGE MARINE CONTRACTING COMPANY,

RYAN STEVEDORING COMPANY and LOCALS 1830 and 1833 GENERAL LONGSHORE WORKERS, INTER

NATIONAL LONGSHOREMEN'S ASSOCIATION,AFL-CIO,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Louisiana—Baton Rouge Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

GEORGE A. DAVIDSON

CHARLES O. BLAISDELL ROBERT M. FUSTER One Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL 435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

JOHNNIE A. JONES

1261-65 Government Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802

GABRIELLE A. KIRK

1834 Southmore Boulevard Houston, Texas 77004

JACK GREENBERGWILLIAM L. ROBINSON

LOWELL JOHNSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ARGUMENT

I. Boudreaux's Status As A Person Aggrieved

Is Not Affected By His Failure To Attend "Shape-ups" During The 90-Day Period

Prior To Filing Of His Charges WithThe EEOC ................................... 1

II. 42 U.S.C. § 1981 Applied To Acts Of

Private Employment Discrimination . ,......... 8

III. The Civil Rights Act Of 1964, Title VII,

Does Not Preempt The Field Of Employment

Discrimination So As To Repeal By Implication 42 U.S.C. § 1981 10

CONCLUSION ....................................... 16

APPENDIX .......................................

Decision in Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works...... la

r

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Banks v. Lockheed-Georgia Company, 47 F.R.D.

422, 444 (N.D. Ga. 1968)......................... 4

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 304 F. Supp.

603 (E.D. La. 1969).......................... 9

Cook County National 3ank v. United States,

107 U.S. 445 (1882)............................... 11

Cox v. United States Gypsum Co, 409 F. 2d

289 (7th Cir. 1969).............. ............ 2

Dobbins v. Local 212, International Brotherhood

of Electrical Workers, 292 F. Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968)........................ 9

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968).......... .. 7

Harrison v. American Can Co., 2 FEP Cases 1

(S.D. Ala. 1969)................................. 9,13

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 2 4 ...................... 8

International Chemical Workers v. Planters Mfg.

Co., 259 F. Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss. 1966). . . . 3

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F. 2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968).............................. 5

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).......... 8,9,10

King v. Georgia Power Co., 295 F. Supp. 943(N.D. Ga. 1968).............................. 4

Local 12, United Rubber Workers v. NLRB, 368 F. 2d 12, 24, n. 24 (5th Cir. 1966)

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 837 (1967)............ 13

Norwegian Nitrogen Products Co. v. United States,

288 U.S. 284, 315 (1933).................... 3

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, 398

F. 2d 496 (1968)............................ 5

ii

Page

Posadas v. National City Bank, 296 U.S. 497503 (1936).................................. 10

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134, 137, 139-40 (1944) 3

Scott v. Young, 412 F. 2d 193 (4th Cir. decidedJanuary 16, 1970)............................ 14

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., U.S.

___, ____, 90 S. Ct., 400. 405(Dec. 15, 1969)............................ 14

United States v. American Trucking Association,310 U.S. 534 (1940)................ 3

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F. 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) aff'd on rehearing en banc, 380 F. 2d(5th Cir., 1967) 3

Van Zandt v. McKee, 202 F. 2d 490 (5th Cir.1953)............................................. 8

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of InternationalHarvester Co., ____F. 2d ____, 62 CCH Lab.

Cas. f 9435 (April 28, 1970).................. 9 12

iii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 29225

ANTOINE R. BOUDREAUX, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants,

v .

BATON ROUGE MARINE CONTRACTING COMPANY,

RYAN STEVEDORING COMPANY and LOCALS 1830

and 1833 GENERAL LONGSHORE WORKERS, INTER

NATIONAL LONGSHOREMEN’S ASSOCIATION AFL-CIO,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The Eastern District of Louisiana—Baton Rouge Division

1/APPELLANTS 1 REPLY BRIEF

ARGUMENT

I .

BOUDREAUX'S STATUS AS A PERSON AGGREIVED IS

NOT AFFECTED BY HIS FAILURE TO ATTEND "SHAPE-

UPS" DURING THE 90-DAY PERIOD PRIOR TO FILING OF HIS CHARGES WITH THE EEOC.

-—/ This brief was prepared with the assistance ofDouglas C. Foerster, One Wall Street, New York

N.Y. 10005, a recent graduate of Northwestern

University Law School who is not yet a member of the Bar.

Appellees urge upon this Court an incredibly

narrow and unprecedented interpretation of the term

"person aggrieved." Regardless of a plaintiff's history

and prior dealings with an employer, Appellees maintain

that no past discrimination renders him aggrieved.

Rather, only discrimination which has an immediate ad

verse effect upon the individual and which can be dated

within 90 days of a charge to the EEOC will suffice. No

cases are cited in support of this interpretation and,

indeed, what law there is clearly runs in the opposite

direction.

For example, the case of Cox v. United States

Gypsum Co., 409 F. 2d 289 (7th Cir. 1969), allowed plaintiff

to proceed even though defendant there challenged the time

liness of plaintiff's action. As in this case, the defend

ant in Cox claimed that plaintiff was not a "person

aggrieved" since he did not file his charges with the

EEOC within 90 days of the occurrence. The Court there

did not, as Appellees here suggest, find that the 90 day

period was satisfied because of acts directed specifically

against Cox during said period. Nonetheless, the Court

held that Cox was a "person aggrieved" for several reasons,

among which were: (1) the discrimination complained of

2

was of a continuing nature, (2) there was an effective

labor contract which prescribed seniority rights and

under which plaintiff was aggrieved by defendant's con

tinuing discriminatory practices, and (3) the fact that

the EEOC accepted the charges as timely is "important

in determining whether the charge is adequate."

This case is strikingly similar to the Cox case.

As in Cox, here there is: (1) an allegation of continu

ing discrimination, (2) a current bargaining agreement

which affects Boudreaux's rights (App. 21), and (3) a

determination by the EEOC that Boudreaux's charges, in

deed, qualify him as a "person aggrieved." (App.. 21).

Appellees do not take issue with the proposition

that interpretation of a statute by the executive agency

charged with its administration and enforcement be given

the highest respect by the courts. International Chemical

Workers Union v. Planters Mfq. Co.. 259 F. Supp. 365

(N.D. Miss. 1966); Norwegian Nitrogen Products Co. v.

United States, 288 U.S. 284, 315 (1933); Skidmore v.

Swift, 323 U.S. 134, 137, 139-40 (1944); United States v.

American Trucking Associations. 310 U.S. 534 (1940);

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education. 372

F. 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff'd on rehearing en banc.

380 F. 2d 385 (1967); 1 Davis, Administrative Law Trea-

3

tise, § 5/06 and cases cited (1959). Therefore, when,

as in the instant case, the EEOC has determined that the

complainant is a "person aggrieved," summary judgment

should not be given defendants on that issue.

Moreover, where there is an allegation of con

tinuing discrimination, it has been held that "filing

within a specified time is not required to bring the

action before this Court." Banks v. Lockheed-Georgia

Company, 47 F.R.D. 442, 444 (N.D. Ga. 1968). It is

significant that Appellees are unable to refute this

position. Indeed, the discussion of King v. Georgia

Power Co., 295 F. Supp. 943 (N.D. Ga. 1968), in the

brief of defendant companies supports this proposition

and focuses the question on one crucial issue: whether

the violations complained of are continuing. The quota

tion set-out on page 18 of that brief indicates that if

the violations are not continuing (irrespective of

against whom they are directed) then the 90-day requirement

will not have been met and a motion for summary judgment

will lie. The reverse of that statement is, of course,

that if the violations are of a continuing nature, the

90-day requirement is satisfied.

Indeed, the entry of intervenors Wells and Collins

as plaintiffs herein reaffirms the continuing nature of

4

the discrimination now beiny challenged. To deny Wells

and Collins the right to proceed on the basis of a novel

semantic interpretation of Boudreaux's standing would

realize the very situation the Court sought to avoid in

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation. 398 F. 2d 496

(1968) wherein it was said:

"Racial discrimination is by defin

ition class discrimination, and to require a multiplicity of separate, identical charges before the EEOC, filed against the same

employer, as a prerequisite to relief through

resort to the court, would tend to frustrate

our system of justice and order." 398 F. 2d at 499.

In reality, it must be noted that the EEOC has

sought and failed to obtain informal conciliation of

Boudreaux's complaint which is identical to the com

plaints of intervenors Wells and Collins. Boudreaux has,

indeed, taken "on the mantle of the sovereign" and should

be permitted to proceed. Jenkins v. United Gas Corn..

400 F. 2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968).

Boudreaux has been personally and directly victim

ized by the practices which are the subject matter of his

complaint. He has worked and lived under the challenged

discrimination for over a decade. Boudreaux’s history

of attending "shape-ups" left no doubt in his mind that

he would never be considered for the only kind of work

5

to which his accident had now limited him. While able-

bodied, he regularly attended "shape-ups" and regularly

received the heavy work reserved for members of his race.

Now injured and able only to perform the lighter work

which ten years of employment has taught him is re

served for whites only, he is told that he is not an

aggrieved person because he failed during the crucial

90 days before filing his charge with the EEOC to attend

"shape-ups" and have his long years of experience with

employment discrimination reconfirmed.

Such a position is like telling a man that he

has no standing to complain of poor public transporta

tion in his home town until he has stood in the rain

awaiting a bus where it is known by all that no service

is provided.

Defendant unions term "absurd" the notion that

Boudreaux may be suing as a representative of persons

similarly situated in Locals 1830 and 1833. (Brief of

Locals 1830 and 1833, p. 10, n. 7). Said unions arrive

at their conclusion from the logic that "Boudreaux is

not suing for the Local; he is suing the Local."

Boudreaux's position is, however, no more absurd than

the classical status of a corporation shareholder bring

ing a shareholder's derivative action against the corp-

6

oration on behalf of aggrieved share holders. Moreover,

Boudreaux does not purport to sue on behalf of the Local

but rather on behalf of such of its individual workers

who have, like himself, been victims of racial dis

crimination .

Finally, Appellees' reference to various analogies

such as proceedings in bankruptcy, illegal search and

seizure and taxpayer suits, in search of cases denying

standing to persons challenging anticipated grievances

are, at best, inapposite. Prospective bidders at bank

ruptcy proceedings and persons convicted from evidence

obtained by violation of another's right against unlaw

ful search and seizure, suffer no invasion of any per

sonal rights, constitutional or otherwise. Boudreaux,

on the other hand, has suffered an invasion of both his

Constitutional and contractual rights. The situations

are so dissimilar that to attempt any kind of equation

is, in the language of Appellee Unions, “absurd."

Last, with reference to the standing of a "mere

taxpayer" to challenge acts of public officials, a com

prehensive discussion and liberal construction of stand

ing in such cases has been enuniciated by the Supreme

Court in Flast v. Cohen. 392 U.S. 83 (1968), in which a

taxpayer was accorded standing to challenge Congressional

spending programs.

7

II.

42 U.S.C. § 1981 APPLIES TO ACTS OF

PRIVATE EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION.

Appellees rely on cases now superseded by Jones

v. Mayer Co■, 392 U.S. 409 (1968) for the propositions

that the Act of 1866 applies only to discrimination under

color of state law and that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 does not

confer a right to be free of racial discrimination in

private employment.

The cases relied upon by Appellees are not only

outdated, but they fail to support the two propositions

for which they are cited. For example, in Hurd v. Hodge.

334 U.S. 24, the Court held that judicial enforcement of

racially restrictive covenants violates the Act of 1866,

but the Court did not say that the Act was limited only

to discrimination under state action or color of law.

Van Zandt v. McKee. 202 F. 2d 490 (5th Cir. 1953) cited

for the same propositions is even more inapposite. In

that case, the Court merely held that one does not have

a right to work for a particular individual without the

latter's consent. The opinion contains no discussion of

the Act of 1866 and nowhere mentions the issue of dis

crimination.

8

For the same propositions, Appellees cite

Harrison v. American Can Co.. 2 FEP Cases 1 (S.D. Ala.

1969). That case somehow interprets Jones v. Mayer.

^urpa, so as to conclude that § 1981 does not necessarily

apply to private acts of employment discrimination. Other

cases decided subsequent to Jones, however, have con

cluded quite the contrary. See e.g.: Dobbins v. Local

212, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio 1968) and Clark v. American

Marine Corp., 304 F. Supp. 603 (E.D. La. 1969). Since

there is some disagreement among different courts as to

the impact of Jones v. Mayer, supra, it is best to rely

upon the Supreme Court's opinion itself for an answer.

An extensive discussion on this point is found in the

Brief of Appellants herein at pages 25-30.

Since the filing of our original brief in this

case, the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit has

squarely held that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 applies to cases of

private employment discrimination. Waters v. Wisconsin

Steel Works of International Harvester Co.. ______F. 2d

_______, 62 CCH Lab. Cas. 5 9435 (April 28, 1970).

Virtually all of the arguments offered by the appellees

herein were specifically advanced to and rejected by

9

the Seventh Circuit. For the convenience of this Court,

a copy of the opinion in the Waters case is attached

. 2 /hereto.

III.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964, TITLE VII,

DOES NOT PREEMPT THE FIELD OF EMPLOYMENT

DISCRIMINATION SO AS TO REPEAL BY IMPLICATION 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Appellees, apparently concerned by the impact

of Jones v. Mayer, supra, and its effect on 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, seek to by-pass the entire problem by claiming

that § 1981 is effectively repealed by Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Court below did not hold that § 1981 was

repealed by implication, and as stated in Posadas v.

National City Bank. 296 U.S. 497, 503 (1936) (quoted with

approval in Jones at 437): "The cardinal rule is that

repeals by implication are not favored." Moreover, had

Congress any intention of amending or repealing 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 it certainly knew the method therefor. For example,

A contrary decision of a district court, handed

down before the Waters case, which had previously not come to our attention is Smith v. North

American Rockwell Corp., 62 CCH Lab. Cas. f 9443 (N.D. Okla. Feb. 25, 1970).

10

in Title I of the same 1964 Civil Rights Act, Congress

amended provisions of 42 U.S.C. 1971 and specifically

so stated in the Act. The same technique is found in

numerous other sections of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and, indeed, in nearly every other piece of legislation.

Significantly, no such effort is made with respect to

42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Appellees seek to relegate 42 U.S.C. § 1981 "to

historians" by claiming that Appellants' rights are now

defined and regulated only by the 1964 Act. Appellee

unions, in a display of either misunderstanding or ex

treme lack of candor, seek to support this notion by

citing numerous cases which allegedly stand for the pro

position that when a more recent law embracing an entire

subject is passed, it may withdraw the subject from the

operation of an older general law as effectively as though

the general law were repealed.

Appellee Unions' leading case is Cook County

National Bank v. United States, 107 U.S. 445 (1882).

Far more interesting than the language set-out in Appellee

Unions' brief on page 18, is the language of the Court's

opinion which Appellees omit. If the Court's opinion is

read in full, the following important language is detected:

11

"***(I)f a particular statute is clearly designed to prescribe the only rules which

should govern the subject to which it re

lates, it will repeal any former one as to

that subject, (citations omitted), ***The

former law must yield to the latter and is

to the extent of the repugnancy superseded by it." 107 U.S. at 451 (emphasis added).

Taken in context then, the rule stated in Cook

County and restated in all the other cases cited by

Appellees, cannot find proper application unless the

later law is designed to prescribe the only rules to

govern the subject and the later law is inconsistent and

repugnant to the former law. Then, and only then, the

former law must yield to the latter and, to the extent

of the repugnancy, is superseded by it. Appellees have

demonstrated no repugnancy between 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and

Title VII; moreover, Title VII is not clearly designed

to afford an exclusive remedy.

The Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit so

held in Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., supra. at p. 6704, stating: "Contrary to

the assertions of defendants, the legislative history of

Title VII strongly demonstrates an intent to preserve

previously existing causes of action." And this Court

reached the same conclusion in a fair representation case,

Local 12, United Rubber Workers v. NLRB, 368 F. 2d 12, 24

12

n. 24 (5th Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 837 (1967):

"Legislative history and specific provisions of the act

itself make it apparent that Congress did not intend to

establish the enforcement provisions of Title VII as the

exclusive remedy in this area."

Finally, we come to the case of Harrison v.

American Can Co.. 2 FEP Cases 1 (S.D. Ala. 1969). Appellees

rely heavily upon this one case for several propositions

in addition to the two previously discussed herein. The

additional propositions are: (1) Title VII preempts

§ 1981, (2) passage of Title VII will be rendered an

"idle and unnecessary" Congressional gesture if § 1981

is applied as Appellants seek, and (3) the courts will

open the floodgates to a "welter of litigation" if con

ciliation is by-passed by § 1981.

The first two of these propositions are nearly

identical to arguments raised in the Jones case and the

'c ' J d Q d ) ■ v b b ' T T K cSupreme Court's discussion therein disposes of the issues.

. " ’r b*- *.f?o» A1In discussing whether a more recent and comprehensive

law. Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, would

■ e A l l cb £-,i~preempt an older and more general provision, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982, the Court held:

•tOy\T2TOL7S Of fprj |gcr * * *(I)t would be a serious mistake

to suppose that § 1982 in any way diminishes

the significance of the law recently enacted

13

by Congress ***the existence of that statute

would not 'eliminate the need for Congressional

action' to spell out ‘responsibility on the part of the federal government to enforce the

rights it protects.' The point was made that,

in light of the many difficulties confronted by private litigants seeking to enforce such

rights on their own, 'legislation is needed

to establish federal machinery for enforcement

of the rights guaranteed under Section 1982

of Title 42*****+(T)he Civil Rights Act of

1968***had no effect upon § 1982." 392 U.S.

at 415-16.

And as in this case, the Court noted the lack

of Congressional intent to repeal by implication:

"***The Civil Rights Act of 1968 does not

mention 42 U.S.C. § 1982, and we cannot

assume that Congress intended to effect

any change, either substantive or proced

ural, in the prior statute, (citations

omitted). 392 U.S. at 416-17 n. 20.

See also Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

____, U.S.______, ____, 90 S. Ct. 400, 405 (Dec. 15,

1969), reaffirming Jones, and also holding that the public

accommodations provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

had not superseded the provisions of the 1866 Act;

Scott v. Young, 421 F. 2d 193 (4th Cir. decided January

16 , 1970) .

Thus, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 should be read

for what it is--- a supplement in the arsenal against dis

crimination. It is a provision of new machinery under

which the Federal Government has attempted to spell-out

14

responsibility for enforcement of rights already extant

under 42 U.S.C. * 1981. Certainly the mood of Congress

and that of the Nation in 1964. following the assassina

tion of President Kennedy, was not to cot back on any

existing civil rights laws.

Finally, as to the third proposition of the

— CiSOn Case' APP«llants direct this Court's attention

to the penultimate sentence of that Court's opinion as

set out on page 25 of Appellee Companies' brief:

Lt sh°uld ever appear that a plaintiff alleging conduct subject to Title VII after

T m e Wv?? and requ irem en t'’u n f e fTitle VII and exhausting his remedies there-

under would still be entitled to s Z differentrelief (not inconsistent with Title VII) byreason of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 * * * it miaht th^n

no ??p;°priate to consider Aether a m u £

I?axntained under the latter statute.But this is not now the case here."

Here, Boudreaux has followed all of the adminis

trative efforts to obtain voluntary compliance and con

ciliation. under Appellees' theory of the case, Boudreaux

cannot proceed further under Title VII, he has effectively

exhausted his remedies. If this Court accepts the view

of Appellees, this case would then present the one situa

tion where even the Harrison court would apply 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981.

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment appealed

from should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

1261-65 Government Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802

GABRIELLE A . KIRK

1834 Southmore Boulevard Houston, Texas 77004

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON LOWELL JOHNSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

GEORGE A . DAVIDSON

CHARLES 0. BLAISDELL ROBERT M. FUSTER

One Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

16

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the hUlh day of June, 1970

I served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

upon Attorneys for appellees, George Mathews, Dale, Owen,

Richardson, Taylor and Mathews, P.0. Box 3177, Baton

Rouge, Louisiana 70821 by depositing a copy of same in

the United States mail air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney fox' Appellants

APPENDIX

2 FEP Cases 574 WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS

he m ay be included in the class and

th a t a class action m ay be m ain ta ined

for in junctive relief only and not for

dam ages are w ithout m erit. Bowe v.

Colgate-Palm olive Co., supra.

T herefore it Is the opinion of th is

C ourt th a t the nam ed p lain tiffs m ay

m ain ta in th is action on behalf of

them selves and as represen tatives of

the class of w hich each is a member.

Since the rep resen tative m ust be a

m em ber of the class, it is necessary

th a t there be two classes, each m ade

up of the Negro m em bers of one of

the d efendan t locals and each rep re

sen ted by th e nam ed p la in tiff who

is a m em ber of th a t local.

M otions to Strike

The d efendan ts have moved ic

s trike from C ount I, p a rag rap h 2, of

th e com plain t the finding of the

Equal Em ploym ent O pportunity Com

m ission on the charges filed by the

p lain tiffs. I t is contended th a t the

find ing is im m ateria l and prejudicial.

In addition , th e defendan ts have

moved to strike all of the affidavits

filed by the p la in tjjfs in opposition

to the d efen d an ts’ m otions, portions

of the am icus brief filed by the EEOC

and the p la in tiffs have moved to

strike certa in affidav its filed by the

defendants.

T he m otion to s trike the portion

of th e com plain t referred to above will

be g ran ted . The find ing of the Com

mission quoted in the com plain t is

no t necessary to estab lish the ju ris

diction of th is Court.

All o ther m otions to strike wdll be

denied. M otions to strike are no t

favored under the Federal Rules and

the num ber of such m otions filed in

th is case is sim ply having the effect

of clouding im p o rta n t issues. The

m otion to s trike provided lo r in Rule

12(f) refers to m a tte r contained in

th e pleadings an d n o t a m a tte r con

ta in ed in briefs. As fa r as the a f

fidavits in th is case are concerned,

th e C ourt is well aw are of w hich

s ta tem en ts are adm issible in evidence

and which arc n o t and they have

been trea ted accordingly.

+

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL

WORKS

U.S. Court of Appeals,

Seventh C ircuit (Chicago)

WATERS, e t al. v. WISCONSIN

STEEL WORKS of INTERNATIONAL

HARVESTER COMPANY an d UNITED

ORDER OF AMERICAN BRICKLAY

ERS AND STONE MASONS, LOCAL

21, No. 17895, April 28, 1970

CIVIL RIGHTS ACTS OF 1866 AND

1864

— R acial d iscrim ination — H iring

—Action under 1866 Act ► 106.06

Form er Negro employee and Negro

em ploym ent app lican t m ay m ain ta in

ac tion under Section 1 of Civil R ights

Act of 1866 aga in st union for allegedly

assisting in m ain tenance of rac la ly

d iscrim inatory h iring system . U.S.

Suprem e Court's decision in Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Co., w hich broadened

Section 2 of Act to forbid private as

well as public racial d iscrim ination in

selling or ren ting of property, is app li

cable to Section 1, w hich outlaw s

racial d iscrim ination in m aking and

enforcing of con trac ts; 1866 Act was

valid exercise of Congress’ power und

T h irteen th A m endm ent to U.S. Con

s titu tio n to en ac t legislation; Section

1 was in tended to proh ib it p rivate job

d iscrim ination ; Section 1 is applicable

to unions as well as to em ployers, In

asm uch as rela tionsh ip betw een em

ployee and union essentially is one of

con tract.

—R acial d iscrim ination—Repeal by

im plication of 1866 Act ► 108.09

► 106.06

E nac tm en t of Title VII of Civil

R ights Act of 1964 did no t constitu te

im plied repeal of Section 1 of Civil

R ights Act of 1866, despite contention

th a t Congress in m aking T itle VII

com prehensive schem e to elim inate

racial d iscrim ination in em ploym ent,

au tom atically abolished all rig h ts p re

viously existing under Section 1 of

1866 Act, where Congress was no t

aw are of 1866 Act when it considered

1964 Act. Legislative h istory dem on

s tra te s th a t Congress would no t have

In tended repeal if it h ad been aw are

of 1866 Act, and possibility of conflict

betw een T itle VII and Section 1 does

n o t dem onstra te th a t Section 1 wholly

was repealed by im plication. Con

flicts between the two provisions m ust

be resolved on case-by-case basis.

—R acial d iscrim ination—F ailure to

file charge w ith EEOC—Action under

1866 Act ► 108.707 ► 10G.06

F ailure to charge a p a rty before

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS 2 FEP Cases 575

EEOC p u rsu an t to Section 706(e) of

Civil R ights Act of 1964 does not

preclude action under Section 1 oi

Civil R ights Act of 18(56, w her; ag

grieved person pleads reasona:die ex

cuse for failure to exhaust EEOC

remedies. Language ot section 706(e

does not expressly require prior re

course to Commission, and legislative

history fails to dem onstrate conclu

sively th a t Section 706(e) was designed

to preclude civil actions by aggrieved

persons w ithou t prior recourse to

Commission. However, if Congress had

been aw are of existence of cause of

action under Section 1, it would h a te

m odified absolute rig h t to bring ac

tion under th a t provision, inasm uch

as legislative History of Iitle v u

dem onstrates strong Congressional

preference for resolution of ui^puteo

by conciliation ra th e r th a n by court

action.

__Racial d iscrim ination—Failure to

file charge w ith K EO C -Iteasonable

excuse ► 106.06 ► 108.707 ► 108.503

Form er Negro employee and Negro

em ploym ent app lican t ‘W “ ‘f t

action under Section 1 of Civu R ights

Act of 1856 ag a in st union for allegedly

assisting in m ain tenance of racially

d iscrim inatory h iring system , since

the ir failure to Me charge against

union w ith EEOC was reasonable.

Prim ary allegation of racial disc rim -

ination ag a in st union is based on

am endm ent to collective-bargaim ng-

apreem ent a fte r filing of charR^

against em ployer, and union suffered

only sligh t prejudice from com plain

a n ts ’ failure to file charge aga in st it

it apnearing th a t union .vas aw are of

charge ag a in st em ployer shortly a fte r

charge was filed. To aind comp*am-

an ts by in fo rm al charge would defeat

effective en fo rcem ent of policies u n

derlying T itle VII of Civil R ights Act

of 1964.

_ R acial d iscrim ination — Action

under 1866 Act — S ta tu te of lim ita

tions b 106.06 ^ 106.237

Action against union under Section

1 of Civil R ights Act of 1866 is not

' barred by 120-day filing Period for

claim s of d iscrim ination provided by

Illinois F air Em ploym ent Practices Act

(SLL 23:201 > * since Illinois Act Is not

m ost analogous s ta te act. Illinois Act

provides only adm in istra tive rem edy

reviewed by courts and seeks to en

courage conciliation and private settle

m rn t, w hereas private litig an t has en

tire burden under Section 1 of investi-

trating and developin'.' case, and when

court relief is sought, conciliation

generally has failed. F ive-year sta te

s ta tu te governing civil actions no t

otherwise provided for is applicable

lim itations period, where s ta tu te has

been applied to action under Section 2

of 1866 Act.

LABOR MANAGEMENT RELATIONS

ACT

— Section 301 action — Action

against employer — R acial d iscrim

ination ► 106.16

Form er Negro employee and Negro

em ploym ent app lican t rnay m ain ta in

action under Section 301 of LMRA

against employer, since th e ir com

p la in t may be read to allege th a t em

ployer trea ted them in d iscrim ina

tory fashion in violation of collective

bargain ing agreem ent between em

ployer and union. At pleading stage,

it may not be said beyond a doubt

th a t com plainants' allegations th a t It

would have been futile to seek redress

th ro u g h con trac tual grievance m ech

anism are insuffic ien t to excuse the

failure to exhaust th e ir con trac tual

remedies.

— Section 301 action — Action

ag a in st union — R acial d iscrim ina

tion ► 106.16

Form er Negro employee and Negro

em ploym ent app lican t m ay m ain ta in

action under Section 301 of LMRA

ag a in st union, since, viewed in ligh t

m ost favorable to them , th e ir com

p la in t alleges th a t union failed to a s

se rt tim ely grievance aga in st employer.

Appeal from U.S. D istric t C ourt for

the N orthern D istrict of Illinois (1

FEP Cases 858. 71 LRRM 2886, 301

F S u p p 663). Reversed and rem anded.

Before SWYGERT, Chief Judge.

CASTLE. Senior C ircuit Judge, and

FAIRCHILD, C ircuit Judge.

Full Text of Opinion

SWYGERT, Chief Ju d g e :—T his ap

peal raises im p o rtan t questions con

cerning the availability and scope of

various federal rem edies for com bating

racial discrim ination in em ploym ent.

P lain tiffs. W illiam W aters and Donald

Samuels, b rough t a class action seek

ing dam ages and in junctive relief

against the W isconsin Steel W orks of

In te rn a tio n a l H arvester Com pany and

Local 21, U nited O rder ol Am erican

Bricklayers and Stone Masons. They

alleged th a t H arvester, w ith th e as

sistance of Local 21. m ain ta in ed a

discrim inatory h iring policy designed

to exclude N egroes, including th e p la in

tiffs from em ploym ent as bricklayers

at, W isconsin Steel Works. P la in tiffs

claim ed th a t these allegations of racial

2 FEP Cases 576 WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS

discrim ination sta ted a cause of action

under four sep ara te s ta tu tes: section 1

of th e Civil R ights Act of 1866, 42

U.S.C. §1981; T itle VII of the I t 64

Civil R ights Act. 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

to e-15; section 301(a) of the Labor-

M anagem ent R elations Act. 29 U.S.C.

5 185(a); and the N ational Labor Re

lations Act. 29 U.S.C. §§ 151 to 167.1

On the m otion of defendan ts the d is

tr ic t court dism issed p la in tiffs’ com

p la in t. The p la in tiffs appeal from the

order of dism issal. We reverse and

rem and for trial.

In th is appeal we m ust determ ine

w hether p la in tiffs have sta ted a cause

of action under any of the s ta tu to ry

grounds cited in th e ir com plaint. We

tre a t the d istric t co u rt’s dism issal of

the com plain t as a sum m ary judgm ent

for th e defendan ts and consider the

affidavits presented in the d istr.c t

cou rt to supplem ent the bare a llega

tions of the com plain t.-

[FACTS]

The facts as alleged in the com plaint

an d supplem ented by affidavits are

n o t in m ateria l dispute. H arvester

employs over forty-five hundred p e r

sons a t W isconsin Steel Works in

Chicago, including a sm all force of

'bricklayers (less th a n fifty m en). Local

21 is the exclusive bargain ing repre

sen ta tive for the bricklayers emploved

by H arvester.

The com plain t alleges th a t prior to

Ju n e 1964 H arvester, w ith the acqui

escence of Local 21, m ain ta ined a

d iscrim inatory h iring policy which ex

cluded Negroes from em ploym ent as

bricklayers. D uring June 1964 five

Negroes, including W illiam W aters,

were h ired as bricklayers. W aters, a

m em ber of Local 21, worked in th a t

capacity from Ju n e 13, 1964 un til he

was laid off on Septem ber 11, 1964.

Nine o th e r bricklayers including all of

th e Negroes h ired in June were d is

charged a t th a t time.

U nder the collective bargain ing

agreem ent workers achieve seniority

only a fte r n inety consecutive days on

the job. T hus all of the Negro brick

layers h ired in Ju n e 1964 worked as

1 P la in tiffs w ithd rew th e ir c la im u n d e r th e

N ational Labor R e la tions Act in th e d is tr ic t

c o u r t. A lthough th e a lleg a tio n of Ju risd ic tion

u n d e r t h a t prov ision has n o t been str ick en

fro m th e co m p la in t, it was n o t reasserted on

appeal We there fo re , deem it to be waived.

See I l l-B , in fra .

2 T h e d is tr ic t c o u r t 's o rder of d ism issa l was

n o t d en o m in a ted as a su m m ary Judgm en t

for th e d e fen d an ts . N evertheless, a ffid av its

were su b m itte d by bo th sides an d w ere n o t

excluded by th e c o u r t. F rom its m em o ran d u m

op in io n i t is ev id en t th a t th e d is tr ic t co u rt

considered these a ffid av its M oreover all

p a rtie s have relied on a ffid av its to tom e

e x te n t in th is appeal. See Fed R.Civ.P. 12(c).

probationary employees an d did no t

acquire seniority and the accom pany

ing rig h t to preferen tial re in sta tem en t

when bricklayer jobs were again avail

able. P lain tiffs allege th a t th is sen io r

ity system , agreed to by Local 21, Is

p a r t of a system atic a tte m p t to ex

clude Negroes from em ploym ent as

bricklayers.

In April 1966 W aters sought bu t was

no t offered reem ploym ent w ith H ar

vester. At the sam e tim e, Donald

Samuels, a m em ber of Local 21, also

applied for em ploym ent w ith H arvester

as a bricklayer. Sam uels, who had

no t previously worked for H arvester

was denied em ploym ent.

[CHARGES FILED]

On M ay 20, 1966 W aters and Sam uel

filed charges w ith the Illinois F air

Em ploym ent Practices Commission a l

leging th a t H arvester refused to hire

them as bricklayers on account of

th e ir race. Three days la te r th e sam e

charges were filed w ith th e Equal

Em ploym ent O pportunity Commission

On February 16, 1967 the EEOC found

th a t no reasonable cause existed to

believe th a t H arvester violated T itle

VII of the Civil R ights A ct*

In M arch 1967 p la in tiff W aters p e ti

tioned for reconsideration of the

EEOC’s finding and provided the fol

lowing additional allegations to sup

po rt h is request. In Septem ber 1965

a num ber of white bricklayers on

layoff s ta tu s elected to receive sever

ance paym ents. By accepting sever

ance pay under the collective b a r

gain ing agreem ent these bricklayers

lost all righ ts to p referen tia l re in

s ta tem en t and became eligible for re

em ploym ent on th e sam e basis as new

employees. Subsequently, on Ju n e 15

1966 H arvester and Local 21 am ended

th e ir collective bargain ing agreem ent

to restore seniority to e igh t w hite

bricklayers whose seniority h ad been

lost a f te r receiving severance pay.

Three of these bricklayers were offered

and accepted em ploym ent. R esto ra

tion of seniority to the rem aining five

workers relegated p la in tiffs to a lis t

fu rth e r away from recall. As a resu lt

p la in tiffs alleged th a t the ir app lica

tions for em ploym ent were no t given

equal consideration and th a t reem ploy-

.1 O n M arch 8. 1907 W aters an d th e o th e r

b rick layers d ischarged in S ep tem ber 1964 were

o ffered reem ploym en t. B elieving th a t he had

been u n su c cesfu l tn h is ac tio n before th e

EEOC. W aters accep ted em ploym ent an d

w orked as a b rick layer from M arch 20 u n til

May 19. 1967 w hen he w as aKaln d ischarged

In A ugust 1967 he was attain o ffered e m

p lo y m en t by H arveste r b u t refused since h is

p e titio n for reco n sid era tio n was th e n p e n d

ing before th e EEOC.

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS 2 FEP Cases 577

m en t of the th ree white workers and

restoration of seniority to all eight

bricklayers perpetuated H arvester’s

continuing policy of h iring only w hite

bricklayers.

On Ju n e 14, 1067 the EEOC gran ted

W aters’ request for reconsideration.

On July 10, 1968 the EEOC w ithdrew

Its previous decision and issued a new

find ing th a t “reasonable cause exists

to believe th a t respondent [H arvester]

violated T itle VII of the Civil R ights

Act of 1964 . . . . ” On November 29,

1968 the EEOC notified W aters and

Sam uels th a t its conciliation efforts

w ith H arvester h ad failed and provid

ed them w ith notice of th e ir r ig h t

to sue.

[COMPLAINT FILED!

On D ecem ber 27, 1968 p la in tiffs filed

th e ir com plain t in the d istric t '•ourt

aga in st H arvester and Local 21. The

d is tric t cou rt gave num erous grounds

for dism issing the com plaint. The

cou rt held th a t the Suprem e C ourt’s

holding in Jones v. Alfred H. M ayer

Co.. 392 U.S. 409 (1968), could no t be

extended to c rea te a cause of action

for “p riva te” racial discrim ination in

em ploym ent un d er 42 U S.C. § 1981.

The court fu r th e r held th a t even if

such a cause of action existed prior

to 1964, it was, nevertheless, preem pted

by the en ac tm en t of T itle VII of the

1964 Civil R ights Act. F urtherm ore,

th e court concluded th a t any action

under section 1981 would be barred by

th e 120-day filing period of the Illinois

F air Em ploym ent P ractices Act.

The d istric t court disposed of p la in

tiffs’ Title VII count against Local 21

by holding, p u rsu a n t to section 706(e)

of T itle VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e>,

th a t Local 21 could no t be joined as

a d e fen d an t since p la in tiffs had not

previously charged the union with

d iscrim inatory practices in a pro

ceeding before the EEOC. The court

fu rth e r held th e action against H ar

vester should also be dismissed since

Local 21 and individual white brick

layers could be adversely affected if

p la in tiffs’ action continued, thereby

m aking Local 21 and the bricklayers,

parties “needed for ju s t ad jud ica tion”

un d er Rule 19, F ederal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

[FINAL HOLDING]

Finally, the cou rt held th a t the

failu re of p la in tiffs to exhaust the

grievance and a rb itra tio n procedures

under the co n trac t precluded su it

under section 301 fa) of the Labor-

M anagem ent R elations Act. In a foot

note the court also sta ted th a t p la in

tiffs failed to s ta te a cause of action

under the N ational Labor Relations

Act, since exclusive ju risd iction under

th a t Act is vested in the N ational

Labor Relations Board.

The cen tral issue in th is appeal is

w hether Local 21 can be sued directly

in the d istric t cou rt w ithout previously

being charged before th e EEOC. If

Local 21 is properly a defendan t, full

relief can be g ran ted an d the applica

bility of Rule 19, Fed.R.Civ.P. need

n o t be considered. We hold th a t a

rig h t to sue under section 1981 for

“p riva te” racial d iscrim ination in em

ploym ent existed prior to 1964. By

enacting Title VII of th e 1964 Civil

R ights Act, Congress did no t repeal

th is rig h t to sue. However, in order

to avoid irreconcilable conflicts be

tween the provisions of section 1981

and T itle VII. a p la in tiff m ust exhaust

h is adm inistra tive rem edies before the

EEOC unless he provides a reasonable

excuse for his fa ilu re to do so. Since

we find on the basis of the m ateria l

before us th a t p la in tiffs have su ffi

ciently justified th e ir failure to charge

Local 21 before the EEOC, we hold

th a t the d is tric t court erred in d is

m issing p la in tiffs ’ com plain t against

th e union. Accordingly, we reverse

for tr ia l on th e m erits of p la in tiffs’

com plain t against Local 21 under sec

tion 1981 and ag a in s t H arvester under

T itle VII.

1. The Existence of a Right to Sue

Under Section 1981.

In Jones v. Alfred H. M ayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968), the Suprem e

C ourt was asked to determ ine the

scope and constitu tionality of 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982.* In its original form section

1982 was p a rt of section 1 of the Civil

R ights Act of 1866.5 T he C ourt held

4 U.S.C. { 1982 read s: "All c itizen s o f th e

U n ited S ta te s have th e sam e r lu h t. In every

S ta te an d T errito ry , as Is en joyed by w hite

c itizen s th e reo f to In h e rit, p u rch ase , lease,

sell, ho ld , an d convey real a n d personal p ro p

e r ty .”

5 Section 1 of th e Civil R ig h ts Act of 1866

prov ided :

Be it enacted by th e S en a te and House o f

R epresen ta tives o f th e U nited S ta te s o f A m

erica in Congress assem bled , T h a t a ll persons

born In th e U n ited S ta te s an d n o t su b je c t to

an y fo reign power. . . . a re h ereby declared

to be c itizen s of th e U nited S ta te s ; a n d su ch

c itizen s , o f every race an d color, w ith o u t re

gard to an y prev ious co n d itio n of slavery

o r In v o lu n ta ry se rv itu d e . . . sha ll have th e

sam e r ig h t. In every S ta te a n d T errito ry In

th e U nited S ta tes , to m ake a n d enforce c o n

tra c ts . to sue. be parties, a n d give evidence,

to In h e rit, purchase , lease, sell. hold , and

convey real and personal p ro p erty , an d to

fu ll and equal b en e fit of a ll law s a n d pro

ceed ings for th e secu rity of person an d

property , as is en joyed by w h ite citizens, and

sh a ll be su b je c t to like p u n ls h n e n t pains,

a n d pena lties , an d to no n e o th e i. an y law.

2FE P C W K S578 WATKR8 v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS

th a t section 1 and its derivative sec

tion 1982, p ro h ib it “all racial d iscrim i

nation , p riva te as well as public, in

the sale or re n ta l of property ”

Jones, supra, a t 413. The constitutio 'n-

fU ty of sect-ion 1982 was upheld on

the basis of Congress' power to en ac t

legislation to enforce the th ir te e n th

am e n d m e n ts

P la in tiffs argue by analogy to the

Jones case th a t 42 U.S.C. } 1981 t is

al.s° d '-rl,ved from section 1 of the

Civil R ights Act of I860; th a t it is a

valid exercise of congressional power

n n d er th e th ir te e n th am endm ent; and

tn a t i t is in tended to prohib it private

rac ia l d iscrim ination in em ploym ent

by com panies and unions. We agree.

There can be little doubt th a t sec

tion 1981, as well as section '982, is

roJiv<̂ dlrect]y from section 1 of m e

1866 Civil R ights Act. In th is ju d g

m en t we rest p rim arily on the views

expressed by the Suprem e C ourt in

the Jones case. In footnote 78, the

C ourt said th a t ‘‘the rig h t to co n trac t

fo r em ploym ent lisl a righ t secured

by 42 U.S.C. § 1981 ( . . . derived

from § l of the Civil R ights Act of

'C P • ) ” Jo n es- supra, a t 442.

This s ta tem en t Is bu ttressed by fu r

th e r m ention of the derivation of sec-

* 0 0 1 9 8 ! in footnote 28, Jones, supra, a t 4zz.

I VIEW SUPPORTED]

The Suprem e C ourt’s view of the

genesis of section 1981 is also sup

ported by our own analysis. In 1870

Congress reenacted section l of the

1866 Act as section 18 of the 1870

Civil R ights Act. As p a r t of the 1870

Aot Congress also adopted section 16

which is sim ilar, a lthough som ew hat

broader, th a n section l of the 1866

Act For purDoses of determ in ing the

derivation of section 1981 we believe

the en ac tm en t of section 16 of the

1870 Act is superfluous since section

s ta tu te , o rd in an ce , reg u la tio n , o r cus tom ,

to th e co n tra ry n o tw ith s ta n d in g .

« T h e th ir te e n th a m e n d m e n t p rovides:

S ection 1:

N e ith e r slavery n o r In v o lu n ta ry se rv itude ,

ex cep t as a p u n ish m e n t for a crim e w hereof

th e p a rty sha ll have been du ly convicted

sh a ll %cx ls t w ith in th e U n ited S ta te s , o r any

p lace su b je c t to th e ir Ju risd ic tio n

S ec tio n 2:

C ongress shall have pow er to enforce th is

a r tic le by a p p ro p ria te leg isla tion .

7 42 U S.C. § 1081 provides:

tt P^rsons w ith in th e Ju risd ic tio n of th e

U n ited S ta te s sha ll have th e sam e r g h t In

every S ta te an d T errito ry to m ake a id e n

force c o n tra c ts , to sue. be p arties , g l ,e evi-

dence, an d to th e fu ll a n d eq u a l b en e fit

of all law s and p roceed ings for th e secu rity

°\..*p ersons an d Pr°P erty as -is e n j o ^ d bv

w hite citizens, a n d sha ll be su b je c t to like

p u n ish m e n ts , pains, pena lties , taxes, licenses

a n d exac tio n s of every k in d , an d to nc o th e r

18 is sufficiently broad to Include the

provisions of section 1981. This con-

clusion is supported by the failure of

defendan ts to p resen t legislative h is

tory to dem onstra te th a t Congress

in tended to narrow the scope of the

P ^ h t “to m ake and enforce con-

* ^ ts. Provision of section 1 of the

1866 Act by the en ac tm en t of section

16. In fact, a con tra ry in te n t is more

JiKely sinee Congress by enacting sec

tion 16 undoubtedly was a ttem p tin g to

insure th a t the r ig h t to m ake and en

force con trac ts w ithout regard to race

was supported by th e fo u rteen th as

well as the th ir te e n th a m e n d m e n t8

From the discussion In the Jones

case, it is also evident th a t section

1981, as p a r t of section 1 of the 1866

Act. was a valid exercise of Congress’

pow er to en ac t legislation under the

th ir te e n th am endm ent. We rest p a r ti

cularly upon th e Suprem e C ourt’s an -

aiysis of Hodges v. U nited S tates, 203

* f 1906). In Hodges a group of

w hite workers were prosecuted under

section 1981 for te rro ris t activities

conducted against Negro employees of

a saw mill. The Suprem e C ourt re-

versed the d efen d an ts’ conviction,

holding th a t section 1981 was no t de

signed to prohib it p rivate ac ts of d is

crim ination . The C ourt in Jones exam

ined the decision in Hodges and ruled;

The conclusion of the majority in

Hodges rested upon a concept of con

gressional power under the Thirteenth

Amendment irreconcilable with the posi

tion taken by every member of this

Court in the Civil Rights Cases and in-

eompatible with the history and purpose

of the Amendment Itself. Insofar as

inconsistent with our holding

“ ‘V m M overruled- Joncs' su-

f CONGRESSIONAL INTENT]

Every indicia of congressional in -

te n t points to the conclusion th a t

section 1981 was designed to p roh ib it

p rivate job d iscrim ination. The words

of the sta tu te , which are alm ost iden-

VQCoao ln f ei evan t a s p e c t to section 1982 m ust be construed to ex tend be

yond insuring the bare legal capacity

of Negroes to en te r in to co n trac ts

T hus Congress provided th a t: "All

persons . . . shall have the sam e righ t

to m ake and enforce co n trac ts as

is enjoyed by white citizens.” We are

no t persuaded th a t the failu re of

Congress to expressly m ention em

ploym ent con trac ts m akes section 1981

d istinguishable from section 1982. This

8 T h e fo u r te e n th a m e n d m e n t w as n o t

ad o p ted u n t i l 1868

I' See genera lly A. L arson. New Law of Race

R e la tio n , 1968 Wls.L. Rev. 470.

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS 2 FEP Cases 579

conclusion is supported by the legis

lative h istory of the I f66 Act which

dem onstra tes Congress’ in te n t th a t

section 1 apply to em ploym ent con

trac ts . As the Suprem e Court noted in

Jones:

Tlie congressional debates are replete

with references to private injustices

against Negroes—references to white em

ployers who refused to pay their Negro

workers, white planters who agreed

among themselves not to hire freed

slaves without the permission of their

former masters. Jones, supra, at 427.

As ari exam ple of Congress’ concern

are the words of R epresentative W in-

dom delivered on the floor of the

House:

Its object is to secure to a poor, weak

class of laborers the right o make con

tracts for their labor, the power to en

force the payment of their wages, and

the means of holding and enjoying the

proceeds of their toil. Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong. 1st Sess. 1159 (1866).

This exp lanation of the purpose of

section 1 of th e 1866 Act dem onstrates

th a t Congress contem plated a proh ib i

tion of racial d iscrim ination in em

ploym ent w hich would extend beyond

s ta te action.

[UNION DISCRIMINATION]

R acial d iscrim ination in em ploym ent

by unions as well as by em ployers is

barred by section 1981. The re la tio n

sh ip between an employee and a union

is essentially one of contract. Ac

cordingly, in the perform ance of its

functions as ag en t for the employees

a union can n o t d iscrim inate aga in st

some of its m em bers on the basis of

race .10 W ashington v. Baugh Con

struction Co., 61 LC II9346 a t 6908,

2 FEP Cases 271, 278 (W.D.Wash. 1969)

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F.

Supp. 413, 1 FEP Cases 387, 69 LRRM

2313 (S.D.Ohio 1968).

D efendants m ake several argum ents

to re fu te th e existence of a cause of

action based on p rivate racial d is

c rim ination In em ploym ent prior to

the enac tm en t of T itle VII of the 1964

Civil R ights Act. These argum ents

m erit only brief discussion. D efend

an ts m a in ta in th a t th e Jones decision

was “foreshadow ed” by cases such as

•Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948);

Shelley v. K raem er, 334 U.S. 1 (1948);

B uchanan v. W arley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917)

and th a t, since sim ilar “foreshadow

in g ” is no t p resen t under section 1981,

the Suprem e C ourt would no t ex tend

10 We need n o t decide w h e th e r nn em ployee

possesses r ig h ts u n d e r § 1981 ag a in s t th e u n io n

If h e Is n o t a m em ber. See S teele v. L o u is

ville & N R.R. Co., 323 'U .a . 112. 198-99, 15

LRRM (1944).

its ruling in Jones to private d iscrim i

n a tion in em ploym ent contracts. If,

by foreshadow ing, th e defendan ts

m ean th a t th e sta te action concept

has som etim es been employed in a

flexible fashion to achieve Just results,

the cases upon w hich they rely fo re

shadow the demise of the requirem ent

of s ta te action under section 1981 as

well. F urtherm ore, i t is m istaken to

suggest th a t courts have no t used

sim ilar m eans to circum vent th e re

quirem ent of s ta te ac tion in the area

of em ploym ent contracts. See Steele

v. Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co., 323

U.S. 192, 198-99, 15 LRRM 708 (1944).

D efendants also argue th a t th e Jones

case is distinguishable from the case

a t bar since property rig h ts have t r a

ditionally been subject to g rea te r gov

ernm en ta l regulation th a n o th e r p ri

vate activity. We disagree. Labor

co n trac t re la tions a re sub jec t to gov

ernm en ta l regulation nearly as ex ten

sive as property rights. Furtherm ore,

we are unclear why de fen d an ts’ as

sertion, even if it were true, is re levant

in constru ing section 1981. Finally,

defendan ts m a in ta in th a t the Jones

case should be given retroactive app li

cation. This a rgum en t is sufficiently

answ ered by the fa c t th a t the S u

prem e C ourt has a lready applied the

Jones case retroactively in Sullivan v.

L ittle H unting Park , Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969).

II. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964

A. Did Title VII repeal section 1981 by

implication?

H aving established th e existence of

a cause of action under section 1981

p rio r to 1964, we m ust now ascerta in

w hether Congress, by th e en ac tm en t

of T itle VII, in tended to repeal the

r ig h t to bring su it for rac ia l d iscrim i

n a tio n in em ploym ent under the fo rm

er section. The rules governing this

determ ination have been sta ted by

the Suprem e Court in Posadas v. N a

tional City Bank, 296 U.S. 497, 503

(1936):

The amending act just described con

tains no words of repeal; and if it ef

fected a repeal of § 25 of the 1913 act,

it did so by i m p l i c a t i o n only.

The cardinal rule is that repeals

by Implication are not favored. Where

there are two acts upon the same sub

ject, effect should be given to both if

possible. There are two well-settled cate

gories of repeals by implication—(1)

where provisions in the two acts are in

Irreconcilable conflict, the later act to the

extent of the conflict constitutes an Im

plied repeal of the earlier one: and (2' if

the later act covers the whole subject

of the earlier one and is clearly intended

2FEP Cases 580 WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS

as a substitute, it will operate similarly

«? * repeal of the earlier act. 3u t. In

either case, the intention of the leeisla-

to repeal must be clear anc manl-

fest, otherwise, at le: st as a general

thing, the later act is to be construed

as a continuation of. and not a substi

tute for the first act and will continue

to speak, so far as the two acts are

actm ent^ *IOm the time of the first en-

We need concern ourselves only w ith

th e doctrine of repeal by im plication

since T itle VII does no t provide for

express repeal of previous legislation,

fu rth e rm o re , the second category of

repeal by im plication noted by the

faupreme Court is inapplicable since

section 1981 covers righ ts o th e r th a n

the rig h t to co n trac t for em ploym ent.

T CONTENTION]

D efendants argue th a t Title VII v/is

in tended by Congress to be a com pre

hensive schem e to elim inate racial

discrim ination in em ploym ent thereby

au tom atically abolishing all righ ts p re

viously existing under section 1981

They point firs t to the fac t th a t Con

gress in enacting T itle V II was u n

aw are of the possibility th a t aggrieved

persons could bring civil suits" under

1T81'11 They would d is tin guish the Jones case on th is basis since

availability of section 19C2 was

m entioned In debate over T itle VIII

of the 1968 Civil R ights Act. Jones

supra, a t 413-17. A fter the recen t de-

£“ i?n Tin s “ !iivan v- L ittle H unting

J n f - i 396 U 229 (19691 ■ this a rgum ent Is no longer viable, in

Sullivan the Suprem e C ourt held th a t

iooorig h t to Jir in K su it under section

^ f8?v,wan lL1?,affected ^ the en ac tm en t ° f the. Public A ccom m odations provl-

° f \ l e 1,964 F lvil R1^h ts Act. even though the legislative h isto ry of th a t

Act fails to m ention section 1982

Sullivan, supra, a t 237. T hus the rele

v an t question for th e purpose of de-

te rm ln ing w hether rig h ts under sec

tion 1981 were repealed by Im plication

is no t w hether Congress was aw are of

section 1981, bu t w hether the legisla

tive history dem onstra tes th a t Con

gress would have in tended repeal if

re,!y “ P e d a lly upo n th e follow ing s ta te m e n ts by C ongressm an L indsay :

T *‘c s itu a tio n in th e law as i t ex ists to -

hOUt th e bu i before us h av in g passed

is th a t any ind iv ld i/a l can b rin g t,n ac tion

* p ro tec tio n o f th e 14th am end"

U l w i i m i n rcspoo ' to a d ep riv a tio n of a con- a tltu tio n a lly p ro tec ted r ig h t.

u sL ee°ther * 0rds- t h?re ls a custom or

h “ K th e ■ tnr% ‘L tflc, c, ls a p rac tice w hich

w hich h a / S . ,f„ S, a te Ix,wer b eh in d It.. s S ta te involvem ent, in it. th e n to

day an ind iv id u a l m ay b rin g ac tio n for m

in ju n c tio n , n o Cong. Re? ]§66 ( i 664)

i t had been aw are of preexisting rig h ts

under the 1866 Civil R ights Act.

C ontrary to the assertions of de-

fendan ts the legislative h istory of

■ , * . 1 strongly dem onstra tes an

in te n t to preserve previously existing

causes of action. T hus Congress re

jected by m ore th an a tw o-to-one

m arg in an am endm ent by S enato r

£ ° w& & ei lclud! a Eencles o ther th a n the EEOC from dealing w ith practices

covered by T t le VII. n o Cong. Rec.

136d0-52 (1964). Courts have accord-

mRly held th a t Title VII does n o t p re

em pt the Jurisdiction of the N ational

Laoor R elations Board to h e a r charges

1°1L , ^ airJ labor practices based on the

duty of fa lr rep resen tation . U nited Packinghouse, Food & Allied

^ “ r^ e rs In te rn a tio n a l Union v. NLRB,

t i e P-2£ U26, 70 LRRM 2489 (E.C. Cir

1969); Local 12, U nited R ubber W ork-

S h C t M * ™ n 63 “ RM 2395

I INDICIA OF INTENT]

D efendants argue, however, th a t the

m ost im p o rtan t indicia of in te n t are

the provisions established in T itle VII

itself and th a t the existence of a cause

or a c t on under section 1981 would

V1J uaiiy destroy these provisions. In

addJ tlo n to the availab ility of im

m ediate access to the courts, they

p o in t to large d ifferences In the class

of persons covered by T t le VII and

section 1981 and varia tions in the sub

stan tiv e prohibitions of th e two e n

actm ents. We agree th a t the difficul-

T?ti»VTTreconclllnE section 1981 and T itle VII are g rea t an d th a t the areas

of passible conflict are num erous.

N evertheless, the Posadas case cautions

th a t ‘ the in ten tio n . . . to repeal m ust

be clear and m an ife s t” and holds th a t

e« e c t should be given to both if

?wSw u ' T h i?-S we can n o t conclude th a t the possibility of conflict dem on

s tra te s th a t section 1981 was wholly

repealed by im plication .1* We are

convinced th a t the two ac ts can in

large m easure, be reconciled and effect

given to the congressional in te n t in

both enactm ents. T herefore, we hold -

th a t conflicts m ust be resolved on a *

case-by-case basis.1* Accordingly we

tu rn to section 706(e) n to determ ine

, generally C o m m ent, R acial D iscrim -

ln a tio n In E m ploym ent U nder th e Civil R ig h ts

Act of 18b6. 36 U.Chl L.Rev. 615 (1969).

_if*We in tim a te no views co n cern in g th e

nueneroua co n flic ts betw een $ 1981 and

V II c !tf d by Local 21 an d Confine our

*5 / esolu tio n o f th o se co n

flic ts w hich are before u* in th is case. t

e v a n t2 p arf;0 1 2° 00<“ 5 (e ) provldf* ln » 1 -

w u u t hl r t jr days a f te r a ch arg e Is filed w ith th e C om m ission . . . th e C om m ission

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS 2 FEP Cases 581

w hether p la in tiffs ' cause of action

u n d er section 1931 ag a in st Local 21

can be reconciled w ith the “charged

p a rty " language of Title VIL

B. T he effect of section 706(e) on th e

r ig h t to bring su it un d er section

1981.

Previously In constru ing section 706

(e) th is court h as held th a t: “I t Is a

ju risd ic tional prerequisite to the filing

of a su it under T itle VII th a t a charge

be filed w ith the EEOC ag a in st the

p a rty sough t to be sued, 42 U.S.C.

1 2000e-5(e).” Bowe v. C olgate-Pal

molive Co., 416 F.2d 711, 719, 2 FEP

Cases 121 (1969).

O ther courts w hich have considered

the question have also held th a t the

“charged p a rty ' language of section

706(e) p rohib its T itle VII su its in the

d istric t court aga in st persons n o t p re

viously charged before the EEOC.

M iller v. In te rn a tio n a l P aper Co., 408

F.2d 283, 1 FEP Cases 647, 70 LRRM

2743 (5th Clr. 1969); Mickel v. South

Carolina Em ploym ent Service, 377 F.2d

239. 1 FEP Cases 132, 65 LRRM 2328

(4 th Clr.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 877,

I FEP Cases 300, 67 LRRM 2898 (1967);

B utler v. Local 4, Laborers’ Union, 61

LC H 9348 a t 6917, 2 FEP Cases 569

(N.D.I11. 1969); Cox v. U nited S ta tes

Gypsum Co., 284 F.Supp. 74. 1 FEP

Cases 602, 70 LRRM 2423 (N.D.Ind.

1968) , m odified, 409 F.2d 289. 1 FEP

Cases 714, 70 LRRM 3278 (7th Cir.

1969) ; Sokolowski v. Sw ift & Co., 286

F.Supp. 775, 1 FEP Cases 611. 70 LRRM

2440 (D.Minn. 1968); Mondy v. Crown

Zellerbach Corp., 271 F.Supp. 258, 1

FEP Cases 253, 66 LRRM 2721 (E.D.La.

1967); Moody v. A lbeniarle P aper Co.,

271 F S upp . 27, 1 FEP Cases 234, 66

LRRM 2099 (E.D.N.C. 1967). Since

these courts were n o t presented w ith

argum ents concerning the existence of

a rig h t to sue under section 1981. the

cases cited were properly decided. They

do no t hold, however, th a t failure to

charge a p a rty before the EEOC p re

cludes su it under section 1981. We

hold such su its can be reconciled w ith

section 706(e) and continue to exist

in a lim ited class of cases.

fLANGUAGE]

The language of section 706(e) i t

self does n o t compel the conclusion

th a t Congress in tended to repeal the

rig h t to bring su it directly under sec-

h as been u n a b le to o b ta in v o lu n ta ry co m

pliance w ith th is su b -c h a p te r , th e C om m is

sion sha ll so n o tify th e person ngsrleved an d

a civil a c tio n m ay. w ith in th ir ty days th e re

a f te r. be b ro u g h t a g a in s t th e re sp o n d en t

nam ed in th e ch arge . . . by th e person

c la im in g to be aggrieved.

tion 1981. Even though th a t section,

in discussing access to th e courts,

concen tra tes on the situ a tio n w here

an aggrieved party h as firs t proceeded

to the EEOC, there is no provision

w hich specifically requires p rio r re

course before the Commission. Since

Congress has expressly prohib ited

d irec t access to federal courts in sim i

la r situa tions under o th e r s ta tu te s ,15

we h esita te to read section 706(e) as

requ iring recourse before th e EEOC as

a ju risd ictional prerequisite In all

cases.

Furtherm ore, th e legislative h isto ry

of T itle VII fa ils to conclusively dem

o n s tra te th a t section 706(e) was de

signed to preclude civil su its by ag

grieved parties w ithou t prior recourse

before the EEOC. A lthough s ta te

m en ts by m em bers of Congress from

the floor during debate should be

viewed w ith cau tion ,16 we note the

following assertion by S enato r H um

phrey, p roponen t and floor m anager

of the bill: “ [T] he Individual m ay

proceed in his own rig h t a t any tim e.

He m ay take his com plain t to the

Commission, he m ay by-pass the Com

m ission, or he m ay go directly to

court.” 110 Cong. Rec. 14 188 (1964).

Despite these ind ications we are

convinced th a t h ad Congress been

aw are of th e existence of a cause of

action under section 1981, the absolute

rig h t to sue under th a t section would

have been m odified.17 T hroughout

the legislative h istory of T itle VII.

Congress expressed a strong preference

for resolution of disputes by concilia

tion ra th e r th a n court action. Con

ciliation was favored for m any reasons.

By establish ing the EEOC Congress

provided an inexpensive and uncom

plicated rem edy for aggrieved parties.

11 See Age D isc rim in a tio n In E m ploym en t

Act of 1987, 29 U.S.C. 5 62«!<1), w here a

civil ac tio n bv a p riv a te p erson Is expressly

p ro h ib ited u n less th e S ecre tary of L abor Is

given six ty days n o tice d u r in g w h ich lim e

h e m ay a tte m p t c o n c ilia tio n .

Hi C on tra ry s ta te m e n ts were m ad e by o p

p o n en ts . Inc lu d in g S e n a to r E rvin w ho de-;

sc ribed th e prov isions of sec tio n 706(e) as

fo llow s: " (T lh e bill p u ts th e key to th e

c o u r th o u se door In th e h a n d s of th e Com

m iss io n .” 110 Cong. Rec. 14 188 (1964).

17 O ur conclusion Is n o t In c o n sis te n t w ith

th e S uprem e C o u rt's h o ld in g in Jo n e s th a t

th e r ig n t to proceed d irec tly In federa l c o u rt

u n d e r 5 1982 Is u n a ffe c te d by th e e n a c tm e n t

of T itle V III of th e 1968 Civil R ig h ts Act.

42 U S .C . §5 3601 to 3619. T h is Is tru e b e

cause 5 812 of t h a t Act prov ides a n aggrieved

p a r ty w ith th e a l te rn a tiv e of by -pass in g th e

S ecre ta ry of H ousing a n d U rb an D evelop

m e n t a lto g e th e r a n d p roceed ing d irec tly In

a civil a c tio n In th e d is tr ic t co u rt. Nor Is

o u r decision In c o n s is te n t w ith th e S uprem e

C o u rt's ho ld ing In S u lliv an th a t 5 1982 was

u n a ffe c te d by th e e n a c tm e n t of T itle I I of

th e 1964 Civil R ig h ts A ct. Section 207(b) of

t h s t t i t le c o n ta in s a n express clause saving

p rio r leg isla tion . S u lliv an , su p ra , a t 238.

I

s

\

!

s

5

t

i

\

i

I

'

j

j«

I

1'i

i

\

2 FEP Cases 582

WATERS v. WISCONSIN STEEL WORKS

m ost of whom were poor an d u n -

sophisticated . C onciliation also was

designed to allow a respondent to

rectify or explain his action w ithout

th e public condem nation resu lting

from a m ore form al proceeding. F u r

therm ore, the absence of d irect gov-

?.E5menA. coercion was th o u g h t to

lessen the an tagon ism betw een p a r

ties and to encourage reasonable se t

tlem ent, The need for vo luntary com

p liance was stressed since m ore co-

5en\edies were likely to inflam e

responden ts and encourage them to

t io n 1̂ subtle form s of d lscrim lna-

fREASONABLE EXCUSE]

Because of th e s trong em phasis w hich

Congress placed upon conciliation, we

d ° n o t th in k th a t aggrieved persons

should be allowed in ten tionally to by

pass th e Commission w ithout good

reason. Wc hold, therefore, th a t an

aggrieved person m ay sue d irectly

u n d er section 1981 if he pleads a

reasonable excuse for his failure to ex

h a u s t EEOC rem edies. We need no t

define th e full scope of th is exception

& w « £ e\ e rKieleM- we believe th a tp la in tiffs in th e case a t b a r have p re-

a llegations su ffic ien t to justify

H }*A !ailure t0 charge Local 21 before the Commission.

We rely p articu la rly on the follow-

ing allegations. The p r im a r / charge

of racial d iscrim ination m ade by p la in

tiffs is based on an am endm en t of the

collective b arga in ing agreem ent be

tween H arvester an d Local 21 T h a t

am en d m en t occurred in June 1966

a lte r p la in tiffs filed th e ir charge be-

fore the EEOC. U ntil th is am endm en t

p la in tiffs were, a t least arguably, u n -

aw are of the p artic ip a tio n of Local 21

i ) H arvester's alleged policy of racial

d iscrim ination . From th e affidav its

before us, it is ev ident th a t Local 21

was aw are of th e charges ag a in st

H arvester, an d by s trong im plication

a f ai r:[?,t as early as October

1966-1!) Subsequent to th is tim e Local

] * Se generally M. Sovern . L fgal R e -

B ip .u x T s o n R acial D i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n E m -

m .o t m i n t ( 1 9 5 6 ) ; D i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n E m -

f i .o t u i .n t a n d i n H o u s i n c : P rivate E n f o f c t -

M4A I —p R y v ,s ,O N S o r THE C i v i l R i g h t s A ct s

Q* 19J4 AND 1968, 82 H aRv. L. R ev . 834 (1969)

l •• We n o te especially th e s ta te m e n ts of

Ja m e s W. Q uisen berry . an in v e s tig a to r fo r

th e EEOC, whose a if ld a v lt read s in p e r tlm e n t p a r t :

In th e reg u la r p e rfo rm an ce of my offic ia l

d u tie s , p u r su a n t to a n in v es tig a tio n o f

ch arg es filed May 23. 1966, by W illiam W aters

o . . D?,!ml,d S am uels a g a in s t th e W isconsin

b tee l W orks, I tw ice c o n tac ted E dw ard T

Joyce. P re s id en t of Local 21. U n ited O rder

of A m erican B rick layers a n d S to n e M asons.

T he f irs t m ee tin g o ccu rred In O ctober 1966;

g u st 8hei967C° nd m eetlnK f0ck P “ ‘ce on A u-

21 presum ably could have rectified

any ac ts of d iscrim ination on its p a rt

Thus Local 21 suffered only sligh t

prejudice from the failu re of p la in tiffs

to charge It before th e EEOC.

[PRESUMED INTENT]

soon! A C o n c e iv a b le th a t Congress

would have In tended to do aw ay w ith

J n l i r!ghA.t0 sue dlrectJy under section 1981 in these circum stances. To do so

would bind com plainan ts by th e four

e f ip e rs of an Inform al charge and de

fe a t the effective en fo rcem ent of the

policies underlying T itle VII. Cf. Cho

a te v. C aterp illar T rac to r Co.. 402 F 2d