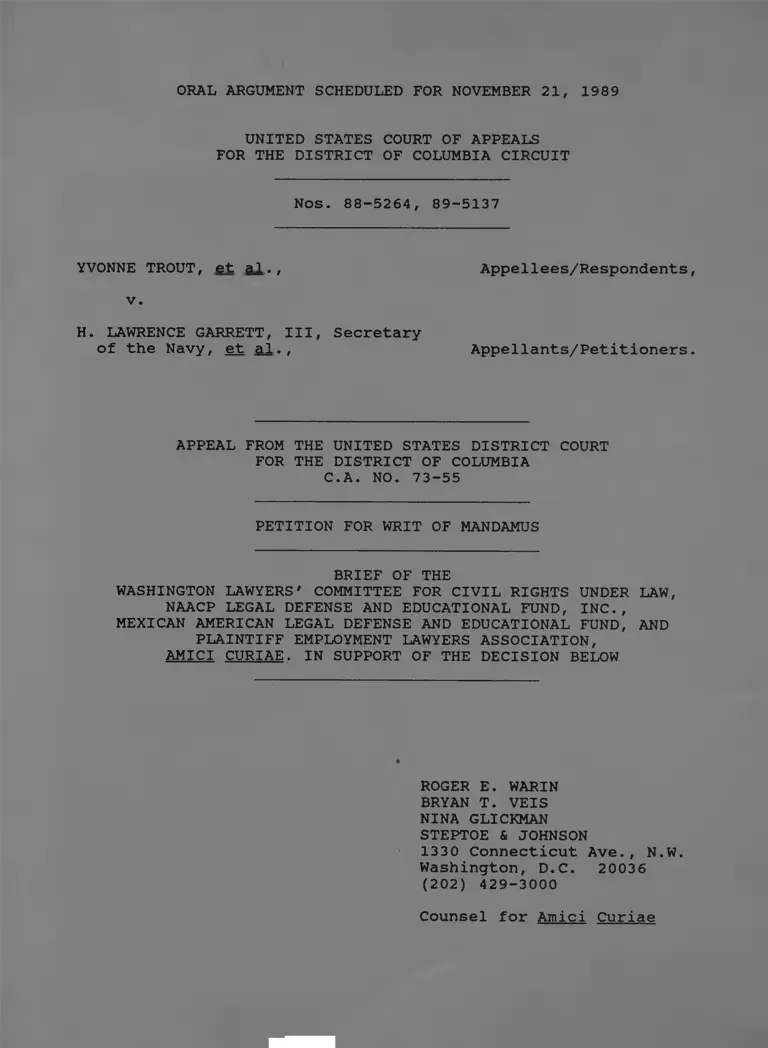

Trout v. Garrett III Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Decision

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Trout v. Garrett III Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Decision, 1989. 5d54dff6-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2cb56663-a553-40cf-8d89-7ab92391d573/trout-v-garrett-iii-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-decision. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!