Columbus Board of Education v. Penick Slip Opinion

Public Court Documents

July 2, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Columbus Board of Education v. Penick Slip Opinion, 1979. 2aec6d0b-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2d5b5a18-0f49-48c5-b62f-a6da7b545a57/columbus-board-of-education-v-penick-slip-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

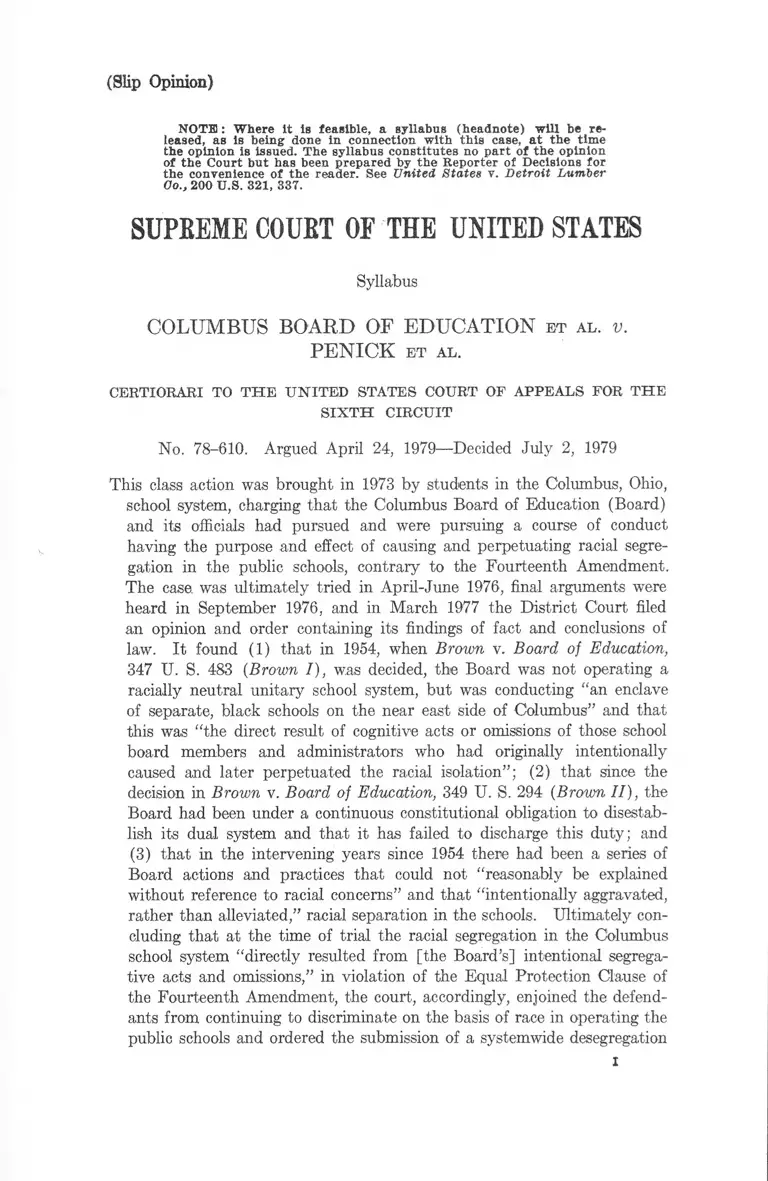

(Slip Opinion)

NOTH: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be re

leased, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time

the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion

of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for

the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Lumber

Oo.f 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPEEME COUBT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION e t a l . v .

PENICK ET AL.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-610. Argued April 24, 1979— Decided July 2, 1979

This class action was brought in 1973 by students in the Columbus, Ohio,

school system, charging that the Columbus Board of Education (Board)

and its officials had pursued and were pursuing a course of conduct

having the purpose and effect of causing and perpetuating racial segre

gation in the public schools, contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment.

The case was ultimately tried in April-June 1976, final arguments were

heard in September 1976, and in March 1977 the District Court filed

an opinion and order containing its findings of fact and conclusions of

law. It found (1) that in 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education,

347 IT. S. 483 (Brown I ), was decided, the Board was not operating a

racially neutral unitary school system, but was conducting “ an enclave

of separate, black schools on the near east side of Columbus” and that

this was “ the direct result of cognitive acts or omissions of those school

board members and administrators who had originally intentionally

caused and later perpetuated the racial isolation” ; (2) that since the

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S, 294 (Brown II), the

Board had been under a continuous constitutional obligation to disestab

lish its dual system and that it has failed to discharge this duty; and

(3) that in the intervening years since 1954 there had been a series of

Board actions and practices that could not “ reasonably be explained

without reference to racial concerns” and that “ intentionally aggravated,

rather than alleviated,” racial separation in the schools. Ultimately con

cluding that at the time of trial the racial segregation in the Columbus

school system “ directly resulted from [the Board’s] intentional segrega

tive acts and omissions,” in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, the court, accordingly, enjoined the defend

ants from continuing to discriminate on the basis of race in operating the

public schools and ordered the submission of a systemwide desegregation

I

II COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

Syllabus

plan. Subsequently, following the decision in Dayton Board of Educa

tion v. Brinkman, 433 U. S. 406 (Dayton I ), the District Court rejected

the Board’s argument that that decision required or permitted modifica

tion of the court’s finding or judgment. Based on its examination of the

record, the Court of Appeals affirmed the judgments against the

defendants.

Held:

1. On the record, there is no apparent reason to disturb the findings

and conclusions of the District Court, affirmed by the Court of Appeals,

that the Board’s conduct at the time of trial and before not only was

animated by an unconstitutional, segregative purpose, but also had cur

rent segregative impact that was sufficiently systemwide to warrant the

remedy ordered by the District Court. Pp. 4-11.

(a) Proof of purposeful and effective maintenance of a body of

separate black schools in a substantial part of the system is itself prima

facie proof of a dual system and supports a finding to this effect absent

sufficient contrary proof by the Board, which was not forthcoming in

this case. Pp. 5-6.

(b) The Board’s continuing affirmative duty to disestablish the

dual school system, mandated by Brown II, is beyond question, and

there is nothing in the record to show that at the time of trial the dual

school system in Columbus and its effects had been disestablished. Pp.

6-9.

2. There is no indication that the judgments below rested on any

misapprehension of the controlling law. Pp. 12-16.

(a) Where it appears that the District Court, while recognizing

that disparate impact and foreseeable consequences, without more, do

not establish a constitutional violation, correctly noted that actions

having foreseeable and anticipated disparate impact are relevant evidence

to prove the ultimate fact of a forbidden purpose, the court stayed

well within the requirements of Washington v. Davis, 426 U. S. 229, and

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U. S. 252,

that a plaintiff seeking to make out an equal protection violation on the

basis of racial discrimination must show purpose. Pp. 12-13.

(b) Where the District Court repeatedly emphasized that it had

found purposefully segregative practices with current, systemwide

impact, there was no failure to observe the requirements of Dayton I,

that the remedy imposed by a court of equity should be commensurate

with the violation ascertained. Pp. 13-15.

(c) Nor was there any misuse of Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413

U. S. 189, where it was held that purposeful discrimination in a sub

stantial part of a school system furnishes a sufficient basis for an infer-

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK hi

Syllabus

ential finding of a systemwide discriminatory intent unless otherwise

rebutted and that given the purpose to operate a dual school system

one could infer a connection between such purpose and racial separation

in other parts of the school system. Pp. 15-16.

583 F. 2d 787, affirmed.

W hite , J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which B rennan ,

M arshall, Blackm un , and Stevens, JJ., joined. Burger, C. J., filed an

opinion concurring in the judgment. Stewart, J., filed an opinion con

curring in the judgment, in which Burger, C. J., joined. Powell, J., filed

a dissenting opinion. R ehnquist, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

Powell, J., joined.

NOTICE : This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication

in the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are re

quested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

United States, Washington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other

formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the pre

liminary print goes to press.

SUPKEME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

M r. Justice W hite delivered the opinion of the Court.

The public schools of Columbus, Ohio, axe highly segregated

by race. In 1976, over 32% of the 96,000 students in the sys

tem were black. About 70% of all students attended schools

that were at least 80% black or 80% white. 429 F. Supp. 229,

240 (SD Ohio 1977). Half of the 172 schools were 90%

black or 90% white. 583 F. 2d 787, 800 (CA6 1978). Four

teen named students in the Columbus school system brought

this case on June 21, 1973, against the Columbus Board of

Education, the State Board of Education, and the appropriate

local and state officials.1 The second amended complaint,

filed on October 24, 1974, charged that the Columbus defend

ants had pursued and were pursuing a course of conduct hav

ing the purpose and effect of causing and perpetuating the

segregation in the public schools, contrary to the Fourteenth

Amendment. A declaratory judgment to this effect and

appropriate injunctive relief were prayed. Trial of the case

began a year later, consumed 36 trial days, produced a record

containing over 600 exhibits and a transcript in excess of 6,600

pages, and was completed in June 1976. Final arguments 1

1 A similar group of plaintiffs was allowed to intervene, and the original

plaintiffs were allowed to file an amended complaint that was certified as a

class action. 429 F. Supp. 229, 233-234 (SD Ohio 1977); App. 50.

No. 78-610

Columbus Board of Education

On Writ o f Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

et al., Petitioners,

v.

Gary L. Penick et al.

[July 2, 1979]

2 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

were heard in September, and in March 1977 the District

Court filed an opinion and order containing its findings of

fact and conclusions of law. 429 F. Supp. 229.

The trial court summarized its findings:

“From the evidence adduced at trial, the Court has

found earlier in this opinion that the Columbus Public

Schools were openly and intentionally segregated on the

basis of race when Brown [v. Board of Education ( / ) ,

347 U. S. 483,] was decided in 1954. The Court has

found that the Columbus Board of Education never ac

tively set out to dismantle this dual system. The Court

has found that until legal action was initiated by the

Columbus Area Civil Rights Council, the Columbus

Board did not assign teachers and administrators to Co

lumbus schools at random, without regard for the racial

composition of the student enrollment at those schools.

The Columbus Board even in very recent times . . . has ap

proved optional attendance zones, discontiguous attend

ance areas and boundary changes which have maintained

and enhanced racial imbalance in the Columbus Public

Schools. The Board, even in very recent times and after

promising to do otherwise, has adjured [sic] workable sug

gestions for improving the racial balance of city schools.

“ Viewed in the context of segregative optional attend

ance zones, segregative faculty and administrative hiring

and assignments, and other such actions and decisions of

the Columbus Board of Education in recent and remote

history, it is fair and reasonable to draw an inference of

segregative intent from the Board’s actions and omission

discussed in this opinion.” Id., at 260-261.

The District Court’s ultimate conclusion was that at the

time of trial the racial segregation in the Columbus school

system “ directly resulted from [the Board’s] intentional segre

gative acts and omissions,” id., at 259, in violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Ac

cordingly, judgment was entered against the local and state

defendants enjoining them from continuing to discriminate on

the basis of race in operating the Columbus public schools and

ordering the submission of a systemwide desegregation plan.

Following decision by this Court in Dayton Board of Educa

tion v. Brinkman ( / ) , 433 U. S. 406, in June 1977, and in

response to a motion by the Columbus Board, the District

Court rejected the argument that Dayton I required or per

mitted any modification of its findings or judgment. It reiter

ated its conclusion that the Board’s “ ‘liability in this case

concerns the Columbus School District as a whole,’ ” Pet. App.

94, quoting 429 F. Supp., at 266, asserting that, although it

had “ no real interest in any remedy plan which is more sweep

ing than necessary to correct the constitutional wrongs plain

tiffs have suffered,” neither would it accept any plan “ which

fails to take into account the systemwide nature of the liabil

ity of the defendants.” Pet. App. 95. The Board subse

quently presented a plan that complied with the District

Court’s guidelines and that was embodied in a judgment en

tered on October 7. The plan was stayed pending appeal to

the Court of Appeals.

Based on its own examination of the extensive record, the

Court of Appeals affirmed the judgments entered against the

local defendants.2 583 F. 2d 787. The Court of Appeals

could not find the District Court’s findings of fact clearly

erroneous. Id., at 789. Indeed, the Court of Appeals exam

ined in detail each set of findings by the District Court and

found strong support for them in the record. Id., at 798, 804,

805, 814. The Court of Appeals also discussed in detail and

found unexceptionable the District Court’s understanding and

application of the Fourteenth Amendment and the cases con

struing it.

2 The Court of Appeals vacated the judgment against the state defend

ants and remanded for further proceedings regarding those parties. 583

F. 2d 787, 815-818 (CA6 1978). No issue with respect to the state

defendants is before us now.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 3

4 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

Implementation of the desegregation plan was stayed pend

ing our disposition of the case. -----U. S .------(1978) (R ehn -

qtjist, J.). We granted the Board’s petition for certiorari,

---- - U. S . ----- (1979), and we now affirm the judgment of the

Court of Appeals.

II

The Board earnestly contends that when this case was

brought and at the time of trial its operation of a segregated

school system was not done with any general or specific

racially discriminatory purpose, and that whatever unconsti

tutional conduct it may have been guilty of in the past such

conduct at no time had systemwide segregative impact and

surely no remaining systemwide impact at the time of trial.

A systemwide remedy was therefore contrary to the teachings

of the cases, such as Dayton I, that the scope of the constitu

tional violation measures the scope of the remedy.3

We have discovered no reason, however, to disturb the judg

ment of the Court of Appeals, based on the findings and con

clusions of the District Court, that the Board’s conduct at

the time of trial and before not only was animated by an un

constitutional, segregative purpose, but also had current, segre

gative impact that was sufficiently systemwide to warrant the

remedy ordered by the District Court.

These ultimate conclusions were rooted in a series of con

stitutional violations that the District Court found the Board

to have commited and that together dictated its judgment and

decree. In each instance, the Court of Appeals found the

District Court’s conclusions to be factually and legally sound.

3 Petitioners also argue that the District Court erred in requiring that

every school in the system be brought roughly within proportionate racial

balance. We see no misuse of mathematical ratios under our decision

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U. S. 1, 22-25

(1971), especially in light of the Board’s failure to justify the continued

existence of “some schools that are all or predominantly of one race. . .

Id., at 26; see Pet. App. 102-103. Petitioners do not otherwise question

the remedy if a systemwide violation was properly found.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 5

A

First, although at least since 1888 there had been no statu

tory requirement or authorization to operate segregated

schools,4 the District Court found that in 1954, when Brown I

was decided, the Columbus Board was not operating a racially

neutral, unitary school system, but was conducting “an en

clave of separate, black schools on the near east side of Co

lumbus,” and that “ [t]he then-existing racial separation was

the direct result of cognitive acts or omissions of those school

board members and administrators who had originally inten

tionally caused and later perpetuated the racial isolation. . .

429 F. Supp., at 236. Such separateness could not “be said to

have been the result of racially neutral official acts.” Ibid.

Based on its own examination of the record, the Court of

Appeals agreed with the District Court in this respect, observ

ing that, “ [wjhile the Columbus school system’s dual black-

white character was not mandated by "state law as of 1954, the

record certainly shows intentional segregation by the Colum

bus Board. As of 1954 the Columbus School Board had

‘carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting a

4 In 1871, pursuant to the requirements of state law, Columbus main

tained a complete separation of the races in the public schools. 429 F.

Supp., at 234-235. The Ohio Supreme Court ruled in 1888 that state law

no longer required or permitted the segregation of school children. Board

of Education v. State, 45 Ohio St. 555. Even prior to that, in 1881, the

Columbus Board abolished its separate schools for black and white students,

but by the end of the first decade of this century it had returned to a

segregated school policy. Champion Avenue School was built in 1909 in a

predominantly black area and was completely staffed with black teachers.

Other black schools were established as the black population grew. The

Board gerrymandered attendance zones so that white students who lived

near these schools were assigned to or could attend white schools, which

often were further from their homes. By 1943 a total of five schools had

almost exclusively black student bodies, and each was assigned an all-black

faculty, often through all-white to all-black faculty transfers that occurred

each time the Board came to consider a particular school as a black school.

Id., at 234-236.

6 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

substantial portion of the students, schools, teachers and facili

ties within the school system.’ ” 583 F. 2d, at 798-799, quot

ing Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U. S. 189, 201-202 (1973).

The Board insists that, since segregated schooling was not

commanded by state law and since not all schools were wholly

black or wholly white in 1954, the District Court was not war

ranted in finding a dual system.5 But the District Court found

that the “ Columbus Public Schools were officially segregated

by race in 1954,” Pet. App. 94 (emphasis added); 6 and in any

5 Both our dissenting Brethren and the separate concurrence put great

weight on the absence of a statutory mandate or authorization to discrimi

nate, but the Equal Protection Clause was aimed at all official actions, not

just those of state legisuatures. “ [N ]o agency of the State, or of the offi

cers or agents by whom its powers are exerted, shall deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Whoever, by vir

tue of public position under a State government, . . . denies or takes away

the equal protection of the laws . . . violates the constitutional inhibition;

and as he acts in the name and for the State, and is clothed with the State’s

power, his act is that of the State.” Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 347

(1880). Thus, in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886), the discrimi

natory application of an ordinance fair on its face was found to be uncon

stitutional state action. Even actions of state agents that may be illegal

under state law are attributable to the State. United States v. Price, 383

U. S. 787 (1966); Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 (1945). Our de

cision in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U. S. 189 (1973), plainly demon

strates in the educational context that there is no magical difference be

tween segregated schools mandated by statute and those that result from

local segregative acts and policies. The presence of a statute or ordinance

commanding separation of the races would ease the plaintiff’s problems of

proof, but here the District Court found that the local officials, by their

conduct and policies, had maintained a dual school system in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court of Appeals agreed, and we fail to

see why there should be a lesser constitutional duty to eliminate that sys

tem than there would have been had the system been ordained by law.

6 The dissenters in this case claim a better grasp of the historical and

ultimate facts than the two courts below had. But on the issue of whether

there was a dual school system in Columbus, Ohio, in 1954, on the record

before us we are much more impressed by the views of the judges who

have lived with the case over the years. Also, our dissenting Brothers’

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 7

event, there is no reason to question the finding that as the

“ direct result of cognitive acts or omissions” the Board main

tained “ an enclave of separate, black schools on the near

east side of Columbus.” 429 F. Supp., at 236. Proof of pur

poseful and effective maintenance of a body of separate black

schools in a substantial part of the system itself is prima facie

proof of a dual school system and supports a finding to this

effect absent sufficient contrary proof by the Board, which was

not forthcoming in this case. Keyes, supra, at 203.7

B

Second, both courts below declared that since the decision

in Brown v. Board of Education (II), 349 U. S. 294 (1955),

the Columbus Board has been under a continuous constitu

tional obligation to disestablish its dual school system and

that it has failed to discharge this duty. Pet. App. 94; 583

F. 2d, at 799. Under the Fourteenth Amendment and the

cases that have construed it, the Board’s duty to dismantle its

dual system cannot be gainsaid.

suggestion that this Court should play a special oversight role in reviewing

the factual determinations of the lower courts in school desegregation cases,

post, at ----- (Rehnqtjist, J., dissenting), asserts an omnipotence and

omniscience that we do not have and should not claim.

7 It is argued that Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman ( / ) , 433

U. S. 406 (1977), implicitly overruled or limited those portions of Keyes

and Swann approving, in certain circumstances, inferences of general, sys

temwide purpose and current, systemwide impact from evidence of dis

criminatory purpose that has resulted in substantial current segregation,

and approving a systemwide remedy absent a showing by the defendant

of what part of the current imbalance was not caused by the constitutional

breach. Dayton I does not purport to disturb any aspect of Keyes and

Swann; indeed, it cites both cases with approval. On the facts found by

the District Court and affirmed by the Court of Appeals at the time Day-

ton first came before us, there were only isolated instances of intentional

segregation, which were insufficient to give rise to an inference of system-

wide institutional purpose and which did not add up to a facially substan

tial systemwide impact. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman (II),

post, a t ---- .

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

Where a racially discriminatory school system has been

found to exist, Brown II imposes the duty on local school

boards to “ effectuate a transition to a racially non-discrimina-

tory school system.” 349 U. S., at 301. “ Brown II was a call

for the dismantling of well-entrenched dual systems,” and

school boards operating such systems were “ clearly charged

with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be

necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial dis

crimination would be eliminated root and branch.” Green v.

County School Board, 391 U. S. 430, 437-438 (1968). Each

instance of a failure or refusal to fulfill this affirmative duty

continues the violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Day-

ton I, 433 U. S., at 413-414; Wright v. Council of City of

Emporia, 407 U. S. 451, 460 (1972) ; United States v. Scotland

Neck City Board of Education, 407 U. S. 484 (creation of a

new school district in a city that had operated a dual school

system but was not yet the subject of court-ordered

desegregation).

The Green case itself was decided 13 years after Brown II.

The core of the holding was that the school board involved

had not done enough to eradicate the lingering consequences

of the dual school system that it had been operating at. the

time Brown was decided. Even though a freedom of choice

plan had been adopted, the school system remained essentially

a segregated system, with many all-black and many all-white

schools. The board’s continuing obligation, which had not

been satisfied, was “ ‘to come forward with a plan that prom

ises realistically to work . . . now . . . until it is clear that state-

imposed segregation has been completely removed.’ ” Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 IT. S. 1,

13 (1971), quoting Green, supra, at 439 (emphasis in original).

As T he Chief Justice’s opinion for a unanimous Court

in Swann recognized, Brown and Green imposed an affirmative

duty to desegregate. “ If school authorities fail in their affirm

ative obligations under those holdings, judicial authority may

be invoked. . . . In default by the school authorities of their

obligation to proffer acceptable remedies, a district court has

broad power to fashion a remedy that will assure a unitary

school system.” 402 U. S., at 15-16. In Swann, it should be

recalled, an initial segregation plan had been entered in 1965

and had been affirmed on appeal. But the case was reopened,

and in 1969 the school board was required to come forth with

a more effective plan. The judgment adopting the ultimate

plan was affirmed here in 1971, 16 years after Brown II.

In determining whether a dual school system has been dis

established, Swann also mandates that matters aside from

student assignments must be considered:

“ [Wjhere it is possible to identify a 'white school’ or a

‘Negro school’ simply by reference to the racial composi

tion of teachers and staff, the quality of school buildings

and equipment, or the organization of sports activities, a

prima jade case of violation of substantive constitutional

rights under the Equal Protection Clause is shown.” 402

U. S., at 18.

Further, Swann stated that in devising remedies for legally

imposed segregation the responsibility of the local authorities

and district courts is to ensure that future school construction

and abandonment are not used and do not serve to perpetuate

or re-establish the dual school system. Id., at 20-21. As for

student assignments, the Court said:

“ No per se rule can adequately embrace all the difficul

ties of reconciling the competing interests involved; but

in a system with a history of segregation the need for

remedial criteria of sufficient specificity to assure a school

authority’s compliance with its constitutional duty war

rants a presumption against schools that are substantially

disproportionate in their racial composition. Where the

school authority’s proposed plan for conversion from a

dual to a unitary system contemplates the continued

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 9

10 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

existence of some schools that are all or predominantly

of one race, they have the burden of showing that such

school assignments are genuinely nondiscriminatory.”

Id., at 26.

The Board’s continuing “ affirmative duty to disestablish

the dual school system” is therefore beyond question, M c

Daniel v. Barred, 402 U. S. 39, 41 (1971), and it has pointed to

nothing in the record persuading us that at the time of trial

the dual school system and its effects had been disestablished.

The Board does not appear to challenge the finding of the

District Court that at the time of trial most blacks were still

going to black schools and most whites to white schools.

Whatever the Board’s current purpose with respect to racially

separate education might be, it knowingly continued its fail

ure to eliminate the consequences of its past intentionally

segregative policies. The Board “ never actively set out to dis

mantle this dual system.” 429 F. Supp., at 260.

C

Third, the District Court not only found that the Board had

breached its constitutional duty by failing effectively to elimi

nate the continuing consequences of its intentional systemwide

segregation in 1954, but also found that in the intervening

years there had been a series of Board actions and practices

that could not “ reasonably be explained without reference

to racial concerns,” id., at 241, and that “ intentionally ag

gravated, rather than alleviated,” racial separation in the

schools. Pet. App. 94. These matters included the general

practice of assigning black teachers only to those schools with

substantial black student populations, a practice that was ter

minated only in 1974 as the result of a conciliation agreement

with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission; the intentionally

segregative use of optional attendance zones,8 discontiguous

8 Despite petitioners’ avowedly strong preference for neighborhood

schools, in times of residential racial transition the Board created optional

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 11

attendance areas,9 and boundary changes; 10 11 and the selection

of sites for new school construction that had the foreseeable

and anticipated effect of maintaining the racial separation of

the schools.11 The court generally noted that “ [s]ince the

attendance zones to allow white students to avoid predominantly black

schools, which were often closer to the homes of the white pupils. For

example, until well after the time the complaint was filed, petitioners

allowed students “ in a small, white enclave on Columbus’ predominantly

black near-east side . . . to escape attendance at black” schools. 429 F.

Supp., at 244. The court could perceive no raeially-neutral reasons for

this optional zone. Id., at 245. “ Quite frankly, the Near-Bexley Option

appears to this Court to be a classic example of a segregative device de

signed to permit white students to escape attendance at predominantly

black schools.” Ibid.

9 This technique was applied when neighborhood schools would have

tended to desegregate the involved schools. In the 1960s, a group of

white students were bused past their neighborhood school to a “whiter”

school. The District Court could “ discern ho other explanation than a

racial one for the existence of the Moler discontinuous attendance area

for the period 1963 through 1969.” Id., at 247. From 1957 until 1963

students living in a predominantly white area near Heimandale elementary

school attended a more remote, but identifiably white, school. Id., at 247-

248.

10 Gerrymandering of boundary lines also continued after 1954. The

District Court found, for instance, that for one area on the west side of

the city containing three white schools and one black school the Board had

altered the lines so that white residential areas were removed from the

black school’s zone and black students were contained within that zone.

Id., at 245-247. The Court found that the segregative choice of lines was

not justified “as a matter of academic administration” and “had a sub

stantial and continuing segregative impact upon these four west side

schools.” Id., at 247.

Another example involved the former Mifflin district that had been

absorbed into the Columbus district. The Board staff presented two alter

native means of drawing necessary attendance zones: one that was desegre-

gative and one that was segregative. The Board chose the segregative

option, and the District Court was unpersuaded that it had any legitimate

educational reasons for doing so. Id., at 248-250.

11 The District Court found that, of the 103 schools built by the Board

between 1950 and 1975, 87 opened with racially identifiable student bodies

12 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

1954 Brown decision, the Columbus defendants or their prede

cessors were adequately put on notice of the fact that action

was required to correct and to prevent the increase in” segre

gation, yet failed to heed their duty to alleviate racial separa

tion in the schools, 429 F. Supp., at 255.12

and 71 remained that way at the time of trial. This result was reasonably

foreseeable under the circumstances in light of the sites selected, and the

Board was often specifically warned that it was, without apparent Justifi

cation, choosing sites that would maintain or further segregation. Id., at

241-243. As the Court of Appeals noted:

“ [T]his record actually requires no reliance upon inference, since, as indi

cated above, it contains repeated instances where the Columbus Board was

warned of the segregative effect of proposed site choices, and was urged to

consider alternatives which could have had an integrative effect. In these

instances the Columbus Board chose the segregative sites. In this situa

tion the District Judge was justified in relying in part on the history of

the Columbus Board’s site choices and construction program in finding

deliberate and unconstitutional systemwide segregation.” 583 F. 2d, at

804.

12 Local community and civil rights groups, the “ Ohio State University

Advisory Commission on Problems Facing the Columbus Public Schools,

and officials of the Ohio State Board of Education all called attention to

the problem [of segregation] and made certain curative instructions.” 429

F. Supp., at 255. This was particularly important because the Columbus

system grew rapidly in terms of geography and number of students, creat

ing many crossroads where the Board could either turn toward segrega

tion or away from it. See id., at 243. Specifically, for example, the Uni

versity Commission in 1968 made certain recommendations that it thought

not only would assist desegregation of the schools but would encourage

integrated residential patterns. Id., at 256. The Board itself came to

similar conclusions about what could be done, but its response was “mini

mal.” Ibid. See also id., at 264. Additionally, the Board refused to cre

ate a site selection advisory group to assist in avoiding sites with a segre

gative effect, refused to ask state education officials to present plans for

desegregating the Columbus public schools, and refused to apply for federal

desgregation-assistance funds. Id., at 257; see id., at 239. The District

Court drew “the inference of segregative intent from the Columbus de

fendants’ failures, after notice, to consider predictable racial consequences

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 13

III

Against this background, we cannot fault the conclusion of

the District Court and the Court of Appeals that at the time

of trial there was systemwide segregation in the Columbus

schools that was the result of recent and remote intention

ally segregative actions of the Columbus Board. While ap

pearing not to challenge most of the subsidiary findings of

historical fact, Tr. of Oral Arg., at 7, petitioners dispute many

of the factual inferences drawn from these facts by the two

courts below. On this record, however, there is no apparent

reason to disturb the factual findings and conclusions entered

by the District Court and strongly affirmed by the Court of

Appeals after its own examination of the record.

Nor do we discern that the judgments entered below rested

on any misapprehension of the controlling law. It is urged

that the courts below failed to heed the requirements of Keyes,

Washington v. Davis, 426 U. S. 229 (1976), and Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429

U. S. 252 (1977), that a plaintiff seeking to make out an equal

protection violation on the basis of racial discrimination must

show purpose. Both courts, it is argued, considered the re

quirement satisfied if it were shown that disparate impact

would be the natural and foreseeable consequence of the

practices and policies of the Board, which, it is said, is nothing

more than equating impact with intent, contrary to the con

trolling precedent.

The District Court, however, was amply cognizant of the

controlling cases. It is understood that to prevail the plain

tiffs were required to “ ‘prove not only that segregated school

ing exists but also that it was brought about or maintained by

intentional state action,’ ” 429 F. Supp., at 251, quoting Keyes,

supra, at 198— that is, that the school officials had “ intended

of their acts and omissions when alternatives were available which would

have eliminated or lessened racial imbalance.” Id., at 240.

14 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

to segregate.” 429 F. Supp., at 254. See also 583 F, 2d, at

801. The District Court also recognized that under those

cases disparate impact and foreseeable consequences, without

more, do not establish a constitutional violation. See, e. g., 429

F. Supp., at 251. Nevertheless, the District Court correctly-

noted that actions having foreseeable and anticipated disparate

impact are relevant evidence to prove the ultimate fact, for

bidden purpose. Those cases do not forbid “ the foreseeable

effects standard from being utilized as one of the several kinds

of proofs from which an inference of segregative intent may

be properly drawn.” Id., at 255. Adherence to a particular

policy or practice, “ with full knowledge of the predictable

effects of such adherence upon racial imbalance in a school

system is one factor among many others which may be con

sidered by a court in determining whether an inference of

segregative intent should be drawn.” Ibid. The District

Court thus stayed well within the requirements of Washington

v. Davis and Arlington Heights. See Personnel Administrator

of Massachusetts v. F eeney,-----IT. S .------, -----n. 25 (1979).

It is also urged that the District Court and the Court of

Appeals failed to observe the requirements of our recent deci

sion in Dayton I, which reiterated the accepted rule that the

remedy imposed by a court of equity should be commensurate

with the violation ascertained, and held that the remedy for

the violations that had then been established in that case

should be aimed at rectifying the “ incremental segregative

effect” of the discriminatory acts identified.13 In Dayton I,

13 Petitioners have indicated that a few of the recent violations specifi

cally discussed by the District Court involved so few students and lasted

for such a short time that they are unlikely to have any current impact.

But that contention says little or nothing about the incremental impaet of

systemwide practices extending over many years. Petitioners also argue

that because many of the involved schools were in areas that had become

predominantly black residential areas by the time of trial the racial separa

tion in the schools would have occurred even without the unlawful conduct

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 15

only a few apparently isolated discriminatory practices had

been found; 14 yet a systemwide remedy had been imposed

without proof of a systemwide impact. Here, however, the

District Court repeatedly emphasized that it had found pur

posefully segregative practices with current, systemwide im

pact.15 429 F. Supp., at 252, 259-260, 264, 266; Pet. App. 95;

583 F. 2d, at 799.16 And the Court of Appeals, responding to

similar arguments, said:

“ School board policies of systemwide application neces-

of Detitioners. But, as the District Court found, petitioners’ evidence in

this respect was insufficient to counter respondents’ proof. See Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U. S. 252,

271 n. 21 (1977); Mt. Healthy School Dist. Bd. of Education v. Doyle, 429

U. S. 274, 287 (1977). And the phenomenon described by petitioners

seems only to confirm, not disprove, the evidence accepted by the District

Court that school segregation is a contributing cause of housing segrega

tion. 429 F. Supp., at 259; see Keyes, 413 IT. S., at 202-203; Swann, 402

U. S., at 20-21.

14 Although the District Court in this case discussed in its major opinion

a number of specific instances of purposeful segregation, it made it quite

clear that its broad findings were not limited to those instances: “Viewing

the Court’s March 8 findings in their totality, this case does not rest on

three specific violations, or eleven, or any other specific number. It con

cerns a school board which since 1954 has by its official acts aggravated,

rather than alleviated, the racial imbalance of the public schools it ad

ministers. These were not the facts of the Dayton case.” Pet. App. 94.

16 M r . Justice R ehnqtjist’s dissent erroneously states that we have

“ relievfed] school desegregation plaintiffs from any showing o f a causal

nexus between intentional segregative actions and the conditions they seek

to remedy.” Post, a t ---- . As we have expressly noted, both the District

Court and the Court of Appeals found that the Board’s purposefully

discriminatory conduct and policies had current, systemwide impact—an

essential predicate, as both courts recognized, for a systemwide remedy.

Those courts reveal a much more knowledgeable and reliable view of the

facts and of the record than do our dissenting Brethren.

16 “ For example, there is little dispute that Champion, Felton, Mt. Ver

non, Pilgrim and Garfield were de jure segregated by direct acts of the

Columbus defendants’ predecessors. They were almost completely segre

gated in 1954, 1964, 1974 and today. Nothing has occurred to substan

16 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

sarily have systemwide impact. 1) The pre-1954 policy

of creating an enclave of five schools intentionally de

signed for black students and known as ‘black’ schools, as

found by the District Judge, clearly had a ‘substantial’—

indeed, a systemwide— impact. 2) The post-1954 failure

of the Columbus Board to desegregate the school system

in spite of many requests and demands to do so, of course,

had systemwide impact. 3) So, too, did the Columbus

Board’s segregative school construction and siting policy

as we have detailed it above. 4) So too did its student

assignment policy which, as shown above, produced the

large majority of racially identifiable schools as of the

school year 1975-1976. 5) The practice of assigning

black teachers and administrators only or in large major

ity to black schools likewise represented a systemwide

policy of segregation. This policy served until July 1974

to deprive black students of opportunities for contact

with and learning from white teachers, and conversely to

deprive white students of similar opportunities to meet,

know and learn from black teachers. It also served

tially alleviate that continuity of discrimination of thousands of black

students over the intervening decades.” 429 F. Supp., at 260 (footnote

omitted).

“The finding of liability in this case concerns the Columbus school dis

trict as a whole. Actions and omissions by public officials which tend to

make black schools blacker necessarily have the reciprocal effect of making

white schools whiter. ‘ [I ]t is obvious that the practice of concentrating

Negroes in certain schools by structuring attendance zones or designating

“feeder” schools on the basis of race has the reciprocal effect of keeping

other nearby schools predominantly white.’ Keyes [, supra, at 201].

The evidence in this case and the factual determinations made earlier in

this opinion support the finding that those elementary, junior, and senior

high schools in the Columbus school district which presently have a pre

dominantly black student enrollment haye been substantially and directly

affected by the intentional acts and omissions of the defendant local and

state school boards.” 429 F. Supp., at 266.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 17

as discriminatory, systemwide racial identification of

schools.” 583 F. 2d, at 814.

Nor do we perceive any misuse of Keyes, where we held that

purposeful discrimination in a substantial part of a school

system furnishes a sufficient basis for an inferential finding of

a systemwide discriminatory intent unless otherwise rebutted,

and that given the purpose to operate a dual school system

one could infer a connection between such a purpose and racial

separation in other parts of the school system. There was no

undue reliance here on the inferences permitted by Keyes, or

upon those recognized by Swann. Furthermore, the Board

was given ample opportunity to counter the evidence of segre

gative purpose and current, systemwide impact, and the find

ings of the courts below were against it in both respects. 429

F. Supp., at 260; Pet. App. 95, 102, 105.

Because the District Court and the Court of Appeals com

mitted no prejudicial errors of fact or law, the judgment ap

pealed from must be affirmed.

So ordered.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 78-610

Columbus Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

v.

Gary L. Penick et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[July 2, 1979]

M r. Chief Justice Burger, concurring in the judgment.

I perceive no real difference in the legal principles stated

in the dissenting opinions of M r . Justice R ehnquist and

M r . Justice Powell on the one hand and the concurring

opinion of M r . Justice Stewart in this case on the other;

they differ only in their view of the District Court’s role in

applying these principles in the finding of facts.

Like M r . Justice R ehnquist, I have serious doubts as to

how many of the post-1954 actions of the Columbus Board

of Education can properly be characterized as segregative in

intent and effect. On this record I might very well have con

cluded that few of them were. However, like M r . Justice

Stewart, I am prepared to defer to the trier of fact because

I find it difficult to hold that the errors rise to the level of

“ clearly erroneous” under Rule 52. The District Court did

find facts sufficient to justify the conclusion reached by

M r . Justice Stewart that the school “ district was not being

operated in a racially neutral fashion” and that the Board’s

actions affected “ a meaningful portion” of the school system.

Keyes v. School District, No. 1, 413 U. S. 189, 208 (1973).

For these reasons I join M r . Justice Stewart’s opinion.

In joining that opinion, I must note that I agree with much

that is said by Justices R ehnquist and Powell in their dis

senting opinions in this case and in Dayton, I agree espe

cially with that portion of M r . Justice R ehnquist’s opinion

that criticizes the Court’s reliance on the finding that both

Columbus and Dayton operated “ dual school systems” at the

time of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 489 (1954), as

a basis for holding that these school boards have labored under

an unknown and unforeseeable affirmative duty to desegregate

their schools for the past 25 years. Nothing in reason or our

previous decisions provides foundation for this novel legal

standard.

I also agree with many of the concerns expressed by

M r. Justice Powell with regard to the use of massive trans

portation as a “ remedy.” It is becoming increasingly doubt

ful that massive public transportation really accomplishes

the desirable objectives sought. Nonetheless our prior de

cisions have sanctioned its use when a constitutional violation

of sufficient magnitude has been found. We cannot retry

these sensitive and difficult issues in this Court; we can only

set the general legal standards and, within the limits of

appellate review, see that they are followed.

2 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

SUPEEME COUET OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 73-610 AND 78-627

Columbus Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

78-610 v.

Gary L. Penick et al.

Dayton Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

78-627 v.

Mark Brinkman et al.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[July 2, 1979]

M r. Justice Stewart, with whom T he Chief Justice

joins, concurring in the result in No. 78-610 and dissenting

in No. 78-627.

M y views in these cases differ in significant respects from

those of the Court, leading me to concur only in the result in

the Columbus case, and to dissent from the Court’s judgment

in the Dayton case.

It seems to me that the Court of Appeals in both of these

cases ignored the crucial role of the federal district courts in

school desegregation litigation1— a role repeatedly emphasized

by this Court throughout the course of school desegregation

controversies, from Broum v. Board, of Education II, 349 U. S.

294,1 2 to Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman I, 433 U. S.

1 Rule 52 (a ), Federal Rule of Civil Procedure, reflects the general defer

ence that is to be paid to the findings of a district court. “Findings of

fact shall not be set aside unless clearly erroneous, and due regard shall

be given to the opportunity of the trial court to judge of the credibility of

the witnesses.” See United States v. United States Gypsum, Co., 333

U. S. 364, 394-395.

2 “ School authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidating,

assessing, and solving these problems; courts will have to consider whether

the action of school authorities constitutes good faith implementation of

2 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

406.3 The development of the law concerning school segre

gation has not reduced the need for sound factfinding by the

district courts, nor lessened the appropriateness of deference

to their findings of fact. To the contrary, the elimination of

the more conspicuous forms of governmentally ordained racial

segregation over the last 25 years counsels undiminished def

erence to the factual adjudications of the federal trial judges

in cases such as these, uniquely situated as those judges are to

appraise the societal forces at work in the communities where

they sit.

Whether actions that produce racial separation are inten

tional wihin the meaning o f Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1 , 413

U. S. 189; Washington v. Davis 426 U. S. 229; and Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429

U. S. 252, is an issue that can present very difficult and subtle

factual questions. Similarly intricate may be factual in

quiries into the breadth of any constitutional violation, and

hence of any permissible remedy. See Milliken v. Bradley I,

418 U. S. 717; Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman I, 433

U. S. 406. Those tasks are difficult enough for a trial judge.

The coldness and impersonality of a printed record, containing

the only evidence available to an appellate court in any case,

the governing constitutional principles. Because of their proximity to

local conditions and the possible need for further hearings, the courts

which originally heard these cases can best perform this judicial appraisal.”

Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U. S. 294, 299.

3 “Indeed, the importance of the judicial administration aspects of the

case are heightened by the presence of the substantive issues on which it

turns. The proper observance of the division of functions between the

federal trial courts and the federal appellate courts is important in every

case. It is especially important in a case such as this where the District

Court for the Southern District of Ohio was not simply asked to render

judgment in accordance with the law of Ohio in favor of one private party

against another; it was asked by the plaintiffs, students in the public

school system of a large city, to restructure the administration of that

system.” Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman (I), 433 U. S. 406,

409-410.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION u. PENICK 3

can hardly make the answers any clearer. I doubt neither the

diligence nor the perservance of the judges of the Courts of

Appeals, or of my Brethren, but I suspect that it is impossible

for a reviewing court factually to know a case from a 6,600

page printed record as well as the trial judge knew it. In

assessing the facts in lawsuits like these, therefore, I think

appellate courts should accept even more readily than in most

cases the factual findings of the courts of first instance.

M y second disagreement with the Court in these cases stems

from my belief that the Court has attached far too much im

portance in each case to the question whether there existed a

“ dual school system” in 1954. As I understand the Court’s

opinions in these cases, if such an officially authorized segre

gated school system can be found to have existed in 1954,

then any current racial separation in the schools will be pre

sumed to have been caused by acts in violation of the Con

stitution. Even if, as the Court says, this presumption is

rebuttable, the burden is on the school board to rebut it.

And, when the factual issues are as elusive as these, who

bears the burden of proof can easily determine who prevails

in the litigation. Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513, 525-526.

I agree that a school district in violation of the Constitution

in 1954 was under a duty to remedy that violation. So was

a school district violating the Constitution in 1964. and so is

one violating the Constitution today. But this duty does not

justify a complete shift of the normal burden of proof.4

Presumptions are sometimes justified because in common

4 In Keyes the Court did discuss the affirmative duty of a school board

to desegregate the school district, but limited its discussion to cases

“where a dual system was compelled or authorized by statute at the time

of our decision in Brown v. Board of Education . . . 413 U. S., at 200.

It is undisputed that Ohio has forbidden its school boards racially to segre

gate the public schools since at least 1888. See Dayton I, 433 U. S., at

410 n. 4; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §3313.48 (1972); Board of Education v.

State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N. E. 373; Clemons v. Board of Education, 228

F. 2d 853, 858.

4 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

experience some facts are likely to follow from others. See

County Court of Ulster County v. Allen ,---- - U. S .-----Sand-

strom v. M ontana,---- U. S . -----. A constitutional violation

in 1954 might be presumed to make the existence of a consti

tutional violation 20 years later more likely than not in one

of two ways. First, because the school board then had an

invidious intent, the continuing existence of that collective

state of mind might be presumed in the abesnce of proof to

the contrary. Second, quite apart from the current intent of

the school board, an unconstitutionally discriminatory school

system in 1954 might be presumed still to have major effects

on the contemporary system. Neither of these possibilities

seems to me likely enough to support a valid presumption.

Much has changed in 25 years, in the Nation at large and in

Dayton and Columbus in particular. Minds have changed

with respect to racial relationships. Perhaps more impor

tantly, generations have changed. The prejudices of the

school boards of 1954 (and earlier) cannot realistically be as

sumed to haunt the school boards of today. Similarly, while

two full generations of students have progressed from kinder

garten through high school, school systems have changed.

Dayton and Columbus are both examples of the dramatic

growth and change in urban school districts.5 It is unrealistic

to assume that the hand of 1954 plays any major part in shap

ing the current school systems in either city. For these rea

5 The Columbus school district grew quickly in the years after 1954. In

1950-1951 the district had 46,352 students. In 1960-1961, over 83,000

students were enrolled. Attendance peaked in 1971-1972 at just over

110,000 students, before sinking to 95,000 at the time of trial. Between

1950 and 1970, an average of over 100 classrooms a year were added to

the district.

Although the Dayton district grew less dramatically, the student popula

tion increased from 35,000 in 1950-1951, of whom approximately 6,600

were Negro, to 45,000 at the time of trial, of whom about 22,000 were

Negro. Twenty-four new schools were opened in Dayton between 1954

and the time of trial.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 5

sons, I simply cannot accept the shift in the litigative burden

of proof adopted by the Court.

Because of these basic disagreements with the Court’s ap

proach, these two cases look quite different to me from the

way they look to the Court. In both cases there is no doubt

that many of the districts’ children are in schools almost solely

with members of their own race. These racially distinct areas

make up substantial parts of both districts. The question

remains, however, whether the plaintiffs showed that this

racial separation was the result of intentional systemwide

discrimination.

The Dayton case

After further hearings following the remand by this Court

in the first Dayton case, the District Court dismissed this law

suit. It found that the plaintiffs had not proved a discrimina

tory purpose behind many of the actions challenged. It

found further that the plaintiffs had not proved that any sig

nificant segregative effect had resulted from those few prac

tices that the school board had previously undertaken with an

invalid intent. The Court of Appeals held these findings to

be clearly erroneous. I cannot agree.

As to several claimed acts of post-1954 discrimination, the

Court of Appeals seems simply to have differed with the trial

court’s factual assessments, without offering a reasoned ex

planation of how the trial court’s finding fell short.6 The

Court of Appeals may have been correct in its assessment of

6 For example, the District Court concluded that faculty segregation in

the Dayton district ceased by 1963, The Court of Appeals reversed,

saying:

“In Brinkman I, supra, 503 F. 2d at 697-98, this court found that de

fendants ‘effectively continued in practice the racial assignment of faculty

through the 1970-71 school year.’ This finding is supported by substan

tial evidence on the record. The finding of the district court to the con

trary is clearly erroneous.” (Footnotes omitted.) 583 F. 2d 243, at 253.

6 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

the facts, but that is not demonstrated by its opinion. I

would accept the trial judge’s findings of fact.

Furthermore, the Court of Appeals relied heavily on the

proposition that the Dayton School District was a “dual sys

tem” in 1954, and today this Court places great stress on the

same foundation. In several instances the Court of Appeals

overturned the District Court’s findings of fact because of the

trial court’s failure to shift the burden of proof.7 Because I

think this shifting of the burden is wholly unjustified, it seems

to me a serious mistake to upset the District Court’s findings

on any such basis. If one accepts the facts as found by the

District Judge, there is almost no basis for finding any consti

tutional violations after 1954. Nor is there any substantial

evidence of the continuing impact of pre-1954 discrimination.

Only if the defendant school board is saddled with the burdens

of proving that it acted out of proper motives after 1954 and

that factors other than pre-1954 policies led to racial separa

tion in the district’s schools, could these plaintiffs possibly

prevail.

For the reasons I have expressed, I dissent from the opinion

and judgment of the Court.

7 Thus, in considering certain optional attendance zones that the District

Court found had not been instituted with a discriminatory intent, the

Court of Appeals wrote:

“ In reaching these clearly erroneous findings of fact, the district court

once again failed to recognize the optional zones as a perpetuation, rather

than an elimination, of the existing dual system; failed to afford plaintiffs

the burden-shifting benefits of their prima facie case; and failed to

evaluate the evidence in light of tests for segregative intent enunciated by

the Supreme Court, this court and other circuits in decisions cited in this

opinion.” 583 F. 2d 243, 255.

The Court of Appeals opinion relied upon the same theory in overturning

the factual conclusions of the District Court that school construction and

site selection had not been undertaken with a discriminatory purpose in

Dayton. Thus, it is impossible to separate the conclusions of law made by

the Court of Appeals from its rulings that the District Court made clearly

erroneous findings of fact.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 7

The Columbus case

In contrast, the Court of Appeals did not upset the District

Court’s findings of fact in this case. In a long and careful

opinion, the District Judge discussed numerous examples of

overt racial discrimination continuing into the 1970’s.''' Just 8

8 The two clearest cases of discrimination involved attendance zones.

The near-Bexley optional zone operated from the 1959-1960 school year

through the 1974-1975 school year. This zone encompassed a small area

of Columbus between Alum Creek and the town of Bexley. The area

west of the creek was predominately Negro; the area covered by the

option was predominately white. Students living in that zone were given

the option of being bused entirely through the City of Bexley to “white”

Columbus schools on its eastern border. The District Court concluded

that:

“ Nothing presented by the Columbus defendants at trial, at closing

arguments, or in their briefs convinces the Court that the Near-Bexley

Option was created or maintained for racially neutral reasons. The Court

finds that the option was not created and maintained because of over

crowding or geographical barriers.

“ Quite frankly, the Near-Bexley Option appears to this Court to be a

classic example of a segregative device designed to permit white students

to escape attendance at predominately black schools.” 429 F. Supp. 229,

245.

The Moler discontiguous zone affected two elementary schools in the

southeastern portion of the school district. A majority of the students in

the Alum Crest Elementary School were, at all relevant times, Negro.

Through 1969, no more than 8.7% of the students at the other school,

Moler Elementary, were Negro. The District Court found:

“Between September, 1966 and June, 1968, about 70 students, most of

them white, were bused daily past Alum Crest Elementary from the dis

contiguous attendance area to Moler Elementary. The then-principal of

Alum Crest watched the bus drive past the Alum Crest building on its

way to and from Moler. At the time, the Columbus Board of Education

was leasing 11 classrooms at Alum Crest to Franklin County. There was

enough classroom space at Alum Crest to accommodate the students who

were transported to Moler. When the principal inquired of a Columbus

school administrator why this situation existed, he was given no reasonable

explanation.

“The Court can discern no other explanation than a racial one for the

8 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

as I would defer to the findings of fact made by the District

Court in the Dayton case, I would accept the trial court’s

findings in this case.

The Court of Appeals did rely in part on its finding that the

Columbus board operated a dual school system in 1954, as

does this Court. But evidence of recent discriminatory in

tent, so lacking in the Dayton case, was relatively strong in

this case. The particular illustrations recounted by the Dis

trict Court may not have affected a large portion of the school

district, but they demonstrated that the district was not being

operated in a racially neutral manner. The District Court

found that the Columbus board had intentionally discrim

inated against Negro students in some schools, and that there

was substantial racial separation throughout the district.

The question in my judgment is whether the District Court’s

conclusion that there had been a systemwide constitutional

violation can be upheld on the basis of those findings, without

reference to an affirmative duty stemming from the situation

in 1954.

I think the Court’s decision in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1,

413 U. S. 189, provides the answer:

“We hold that a finding of intentionally segregative

school board actions in a meaningful portion o f a school

system, as in this case, creates a presumption that other

segregated schooling within the system is not adven

titious. It establishes, in other words, a prima facie case

of unlawful segregative design on the part of school au

thorities, and shifts to those authorities the burden of

proving that other segregated schools within the system

are not also the result of intentionally segregative

actions.” 413 U. S., at 208.

The plaintiffs in the Columbus case, unlike those in the Day

existence of the Moler discontiguous attendance area for the period 1963

through 1969.” 429 F. Supp. 229, 247.

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 9

ton case, proved what the Court in Keyes defined as a prima

facie case.9 The District Court and the Court of Appeals

correctly found that the school board did not rebut this

presumption. It is on this basis that I agree with the Dis

trict Court and the Court of Appeals in concluding that the

Columbus school district was operated in violation of the

Constitution.

The petitioners in the Columbus case also challenge the

remedy imposed by the District Court. Just two Terms ago

we set out the test for determining the appropriate scope of

a remedy in a case such as this:

“If such violations are found, the District Court in the

first instance, subject to review by the Court of Appeals,

must determine how much incremental segregative effect

these violations had on the racial distribution of the . . .

school population as presently constituted, when that

distribution is compared to what it would have been

in the absence of such constitutional violations. The

remedy must be designed to redress that difference, and

only if there has been a systemwide impact may there be

a systemwide remedy.” Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman I, 433 U. S. 406, 420.

In the context in which the Columbus case has reached us, I

cannot say that the remedy imposed by the District Court was

impermissible under this test. For the reasons discussed

above, the District Court’s conclusion that there was a sys

temwide constitutional violation was soundly based. And

9 The Denver school district at the time of the trial in Keyes had 96,000

students, almost exactly the number of students in the Columbus system

at the time of this trial. The Park Hill region of Denver had been the

scene of the intentional discrimination that the Court believed justified a

presumption of systemwide violation. That region contained six elemen

tary schools and one junior high school, educating a small portion of the

school district’s students, but a large number of the district’s Negro

students.

10 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

because the scope of the remedy is tied to the scope of the

violation, a remedy encompassing the entire school district

was presumptively appropriate. In litigating the question

of remedy, however, I think the defendants in a case such as

this should always be permitted to show that certain schools

or areas were not affected by the constitutional violation.

The District Court in this case did allow the defendants to

show just that. The school board proposed several remedies,

but it put forward only one plan that was limited by the

allegedly limited effects of the violation. That plan would

have remedied racial imbalance only in the schools mentioned

in the District Court’s opinion. Another remedy proposed by

the school board would have resulted in a rough racial balance

in all but 22 “ all-white” schools. But the board did not assert

that those schools had been unaffected by the violations. In

stead, it justified that plan on the ground that it would bring

the predominately Negro schools into balance with no need

to involve the 22 all-white schools on the periphery of the

district. The District Court rejected this plan, finding that

it would not offer effective desegregation since it would leave

those 22 schools available for “white flight.” The plan ulti

mately adopted by the District Court used the Negro school

population of Columbus as a benchmark, and decreed that all

the public schools should be 32% minority, plus or minus

15%.

Although, as the Court stressed in Green v. County School

Board, 391 IT. S. 430, a remedy is to be judged by its effective

ness, effectiveness alone is not a reason for extending a remedy

to all schools in a district. An easily visible correlation be

tween school segregation and residential segregation cannot by

itself justify the blanket extension of a remedy throughout a

district. As Dayton I made clear, unless a school was affected

by the violations, it should not be included in the remedy. I

suspect the defendants in Columbus might have been able to

show that at least some schools in the district were not affected

COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK 11

by the proven violations. Schools in the far eastern or north

ern portions of the district were so far removed from the

center of Negro population that the unconstitutional actions

of the board may not have affected them at all. But the

defendants did not carry the burden necessary to exclude those

schools.

The remedy adopted by the District Court used numerical

guidelines, but it was not for that reason invalid. As this

Court said in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U. S. 1,

“Awareness of the racial composition of the whole school

system is likely to be a useful starting point in shaping a

remedy to correct past constitutional violations. In sum,

the very limited use made of mathematical ratios was

within the equitable remedial discretion of the District

Court.” 413 U. S., at 25.

On this record, therefore, I cannot say that the remedy was

improper.

For these reasons, I concur in the result in Columbus Board

of Education v. Penick, and dissent in Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 78-610 a n d 78-627

Columbus Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

78-610 v.

Gary L. Penick et al.

Dayton Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

78-627 v.

Mark Brinkman et al.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[July 2, 1979]

M r. Justice Powell, dissenting.

I join the dissenting opinions of M r. Justice R ehnquist

and write separately to emphasize several points. The

Court’s opinions in these two cases are profoundly disturbing.

They appear to endorse a wholly new constitutional concept

applicable to school cases. The opinions also seem remark

ably insensitive to the now widely accepted view that a quar

ter of a century after Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483 (1954), the federal judiciary should be limiting rather

than expanding the extent to which courts are operating the

public school systems of our country. In expressing these

views, I recognize, of course, that my Brothers who have

joined the Court’s opinions are motivated by purposes and

ideals that few would question. M y dissent is based on a

conviction that the Court’s opinions condone the creation of

bad constitutional law and will be even worse for public edu

cation—an element of American life that is essential, especially

for minority children.

I

M r. Justice R ehnquist’s dissents demonstrate that the

Court’s decisions mark a break with both precedent and prin

2 COLUMBUS BOARD OF EDUCATION v. PENICK

ciple. The Court indulges the courts below in their stringing

together of a chain of “presumptions,” not one of which is

close enough to reality to be reasonable. See ante, at 4 (opin

ion of Stewart, J.). This claim leads inexorably to the re

markable conclusion that the absence of integration found to

exist in a high percentage of the 241 schools in Columbus and

Dayton was caused entirely by intentional violations of the

Fourteenth Amendment by the school boards of these two

cities. Although this conclusion is tainted on its face, is not

supported by evidence in either case, and as a general matter

seems incredible, the courts below accepted it as the necessary

premise for requiring as a matter of constitutional law a sys

temwide remedy prescribing racial balance in each and every

school.

There are unintegrated schools in every major urban area

in the country that contains a substantial minority popula

tion. This condition results primarily from familiar segre

gated housing patterns, which—in turn— are caused by social,

economic, and demographic forces for which no school board

is responsible. These causes of the greater part of the school

segregation problem are not newly discovered. Nearly a

decade ago, Professor Bickel wrote:

“ In most of the larger urban areas, demographic condi

tions are such that no policy that a court can order, and

a school board, a city or even a state has the capability

to put into effect, will in fact result in the foreseeable

future in racially balanced public schools. Only a re

ordering of the environment involving economic and social

policy on the broadest conceivable front might have an

appreciable impact.” A. Bickel, The Supreme Court and

the Idea of Progress 132 n. 7 (1979) 2 1

1 See also Farley, Residential Segregation and Its Implications for School

Integration, 39 L. & Contemp. Probs. 164 (1975); K. Taeuber & A. Taeu-

ber, Negroes in Cities (1965). The Court of Appeals below treated the

residential segregation in Dayton and Columbus as irrelevant. See post,