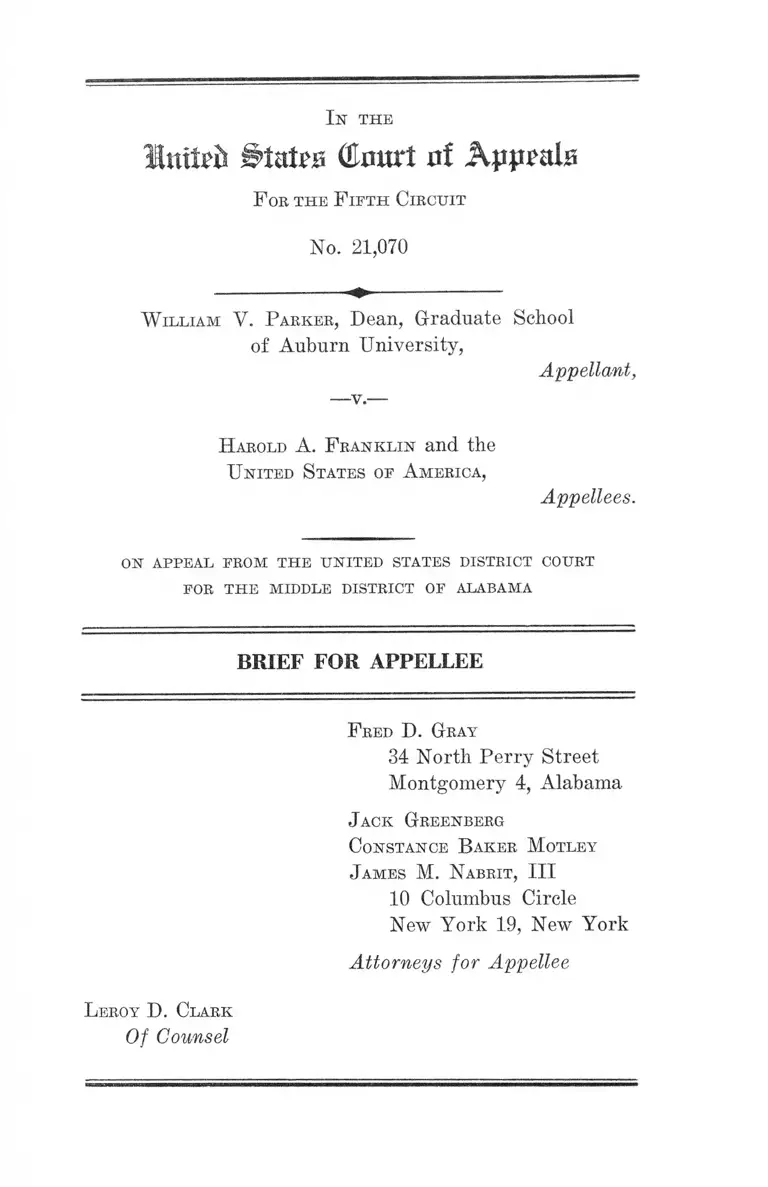

Parker v. Frankin Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Parker v. Frankin Brief for Appellee, 1964. 6771fd93-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2d8ee86c-7b20-4b8b-92b3-9b27ca24b013/parker-v-frankin-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In the

luiini ^tatrii (knurl nf Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 21,070

W illiam V. Parker, Dean, Graduate School

of Auburn University,

Appellant,

H arold A. F ranklin and the

United States of A merica,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Fred D. Gray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery 4, Alabama

Jack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellee

L eroy D. Clark

Of Counsel

In the

Itttteft #!a!?s tour! nf Appals

F oe the F ifth Cikcttit

No. 21,070

W illiam V. Parker, Dean, Graduate School

of Auburn University,

Appellant,

-v.-

H arold A. F ranklin and the

United States of A merica,

Appellees.

on a p pe a l fr o m t h e u n it e d states d istric t court

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF AL A B AMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the District Court

for the Middle District of Alabama of November 5, 1963,

enjoining William V. Parker, Dean of the Graduate School

of Auburn University, from denying admission of Harold

Franklin and other Negro applicants to Auburn University

on the basis of race and color.

On August 26, 1963, Harold A. Franklin, a Negro citizen

of the State of Alabama, filed an action against William V.

Parker, Dean of the Graduate School of Auburn University

and Charles W. Edwards, Registrar of Auburn University,

2

seeking admission to the Graduate School. Jurisdiction was

invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. 1343(3) and 42 U. S. C.

1981, 1983. The suit was brought as a class action under

Rule 23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The complaint alleged that plaintiff Franklin’s applica

tion for admission to Auburn University had been denied

because his undergraduate degree had been obtained from

Alabama State College, an unaccredited institution operated

by the State of Alabama exclusively for Negroes, in viola

tion of his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution. Plaintiff sought to enjoin de

fendants from, among other things, rejecting Negro appli

cants who apply to Graduate School at Auburn University

because of their attendance at non-accredited colleges oper

ated by the State of Alabama, where attendance at un

accredited state institutions has been required because of

their race, and from continuing to pursue the policy, prac

tice, custom and usage of limiting admission to Auburn

University to white persons (R. 2, 10). Plaintiff also filed

a motion for preliminary injunction to enjoin the defen

dants, their agents, servants, employees, successors, and

all persons in active concert with them from refusing to

(a) admit him to the Auburn Graduate School; (b) expedi

tiously process the applications of Negroes on the same

terms and conditions as white applicants; (c) admit Negroes

solely on the basis of race and color (R. 17-19). A hearing

on the motion for preliminary injunction was set for Sep

tember 19, 1963 (R. 20).

September 9,1963, the Court designated the United States

a party (R. 20-22). September 17, 1963, defendants filed

an answer and affidavits in opposition to plaintiff’s motion

for preliminary injunction (R. 22-32). In their answer de

fendants denied that the suit was a proper class action or

that plaintiff had been denied admission because of race.

3

Defendant Edwards, Registrar of Auburn University, was

dismissed from the action (R. 33-34). November 5, 1963,

the District Court granted plaintiff’s motion for preliminary

injunction, and made the following findings of fact: (a) that

appellee Franklin was a permanent resident of Talladega,

Alabama and resided in Montgomery, Alabama; (b) that

he received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Alabama State

College in May, 1962; (c) that if his record at Alabama

State College met the requirements of the Graduate School

at Auburn University he was eligible for admission to Au

burn; (d) that Negroes have been graduated from either

of two State Colleges established and maintained by the

State of Alabama exclusively for Negroes; (e) that both of

these schools were under the express management and con

trol of the State Board of Education; (f) that both are

designated by statute as schools for Negroes, and these

two colleges are the only two state institutions of higher

learning for Negroes in Alabama though other state in

stitutions of higher learning were maintained exclusively

for white students; (g) that in 1956, Alabama State College

was given probationary accreditation by the Southern As

sociation of Colleges and Schools; (h) that in 1961, ac

creditation was withdrawn from both Alabama State Col

lege and Alabama A. & M. College, and at that time Franklin

was graduated (and at present) neither school was ac

credited; (i) that during the same period, all the Alabama

colleges and universities limited to white persons were

fully accredited; and (j) that both the Alabama State Super

intendent and Board of Education were aware of the defi

ciencies that caused first the probationary status and sub

sequent disaccreditation of the Negro institution. The Court

held that the suit was a proper class action and stated:

. . . the State of Alabama has denied to Harold A.

Franklin, a Negro—solely because he is a Negro—the

opportunity to receive an undergraduate education at

4

an accredited State college or university; at the same

time, the State of Alabama afforded adequate oppor

tunity to its white citizens to receive an undergraduate

education at accredited State institutions. Now, after

having done this, the State of Alabama, acting through

its State operated and maintained institution Auburn

University, insists that graduate education at that in

stitution shall be open only to students who are grad

uates of accredited colleges or universities. On its face,

and standing alone, the requirement of Auburn Uni

versity concerning graduation from an accredited in

stitution as prerequisite to being admitted to Graduate

School is unobjectionable and a reasonable rule for a

college or university to adopt. However, the effect of

this rule upon Harold A. Franklin—an Alabama Negro

—and others in his class . . . is necessarily to preclude

him from a postgraduate education at Auburn Uni

versity solely because the State of Alabama discrim

inated against him in its undergraduate schools. Such

racial discrimination on the part of the State of Ala

bama amounts to a clear denial of the equal protection

of the laws. (R. 40-41)

The court ordered Franklin admitted to the Graduate

School of Auburn University in January, 1964, and en

joined defendants from rejecting other qualified Negro

applicants. Defendants filed notice of appeal November 13,

1963. A motion for order suspending preliminary injunc

tion pending appeal was denied November 20, 1963.

5

A R G U M E N T

The Court Below Properly Held That Appellee Was

Denied Admission to Auburn University on a Racially

Discriminatory Basis in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The facts of this case are plain: Harold Franklin, a

Negro, applied for admission to the Graduate School of

Auburn University. Dean Parker rejected the application

on the sole ground that Franklin had not graduated from

an accredited college. At the time of Franklin’s applica

tion, the State of Alabama maintained eight institutions for

undergraduate training of which two were limited by stat

ute to Negro students. (See: Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §§438,

441, 452, 454, 455.) Neither of the Negro institutions were

accredited through the admitted fault of the State of Ala

bama (R. 149).1 All six white institutions were accredited.

The court below found that Franklin had been excluded

solely because of race. Its finding was clearly supported by

the facts and the evidence. This Court should not set aside

its finding unless clearly erroneous, 52(a), Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure.

The issue before this Court is equally plain: Can the

State of Alabama require Negroes seeking admission to

State operated graduate schools to hold degrees from ac

credited undergraduate institutions while limiting Negroes’

attendance to nonaccredited undergraduate institutions!

The lower court correctly held not.

1 Alabama State College was accredited from December 1956

until December 1961. Franklin entered the college in September

1958 and graduated May 1962. He thus had years of accredited

education.

6

On its face, the requirement that applicants for graduate

school present a degree from an accredited college is rea

sonable and comports with approved educational standards.

However, in view of the State of Alabama’s enforced policy

and practice of segregation which has limited attendance

of Negro students to two nonaccredited state institutions,

the requirement is patently discriminatory and deprives

Negro applicants of equal protection of law.2 As the State

of Alabama provides graduate training, it must do so with

out discrimination. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305

U. S. 337 (1938).

In Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962), this

Court held that the University of Mississippi could not

require Negro applicants to furnish alumni certificates

where Negroes had never been permitted to attend and

graduate from that University. See also, Hunt v. Arnold,

172 F. Supp. 849 (M. D. G-a. 1959) (alumni certificate re

quirement for Negro applicants held unconstitutional at

Georgia State College); United States v. Manning, 205 F.

Supp. 172 (W. D. La. 1962); and United States v. Ward,

222 F. Supp. 617 (W. D. La. 1963) (prohibiting voting

registrars from refusing to register Negroes because they

could not get two registered voters to attest to their iden

tity where there were no Negro voters in the county).

Similarly, this Court upheld the decision of a District

Court holding a Louisiana statute requiring a certificate

2 While desegregation of Alabama public universities was or

dered in Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235 (1955), 228 F. 2d 619,

cert. den. 351 U. S. 931, fierce resistance to desegregation remained

as late as 1963. See Lucy v. Adams and Carroll v. Mate, 8 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 452; McCorvey v. Lucy, No. 20,898, pending in this

Court. See also, Presidential Proclamation No. 3542, June 11,

1963, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 455 where President Kennedy commanded

the “ Governor of Alabama and all other persons . . . to cease and

desist” from unlawful obstructions of justice. Governor Wallace

was attempting to keep two Negro students from enrolling at the

University of Alabama.

7

of good moral character for admission to state universities

racially discriminatory where Negro high school principals

were given certificates addressed only to Negro colleges.

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State Uni

versity, 150 F. Snpp. 900 (E. D. La. 1957), affirmed 252

F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358 U. S. 819 (1958).

There the trial court stated the statute was “unconstitu

tional for the reason that the obvious intent of the legis

lature in passing the act was to discriminate against Negro

citizens and thus to circumvent the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment,” 150 F. Supp. at 904.

These holdings govern this case. Indeed, the discrimina

tion in this case is even plainer than that in Meredith or

Hunt. In those cases there was perhaps a remote possibility

that a Negro might have been able to convince a few white

alumni to furnish certificates. Here, applicants are abso

lutely cut off by the State from obtaining graduate training

by a eondition'created by the State. The condition here is

almost identical with the “ Grandfather Clause” struck

down in Guinn v. United States, 238 IT. S. 347 (1915), where

the State of Oklahoma required a preregistration literacy

test of everyone except those qualified to vote in 1866 oi

who had lineal descendants who were qualified to vote at

that time. Negroes, deprived of the right to vote in 1866,

were burdened with a condition operative solely because of

race and designed to preclude their exercising the fran

chise. Later Oklahoma replaced the “ Grandfather Clause”

with a requirement that persons previously barred from

voting could qualify only by registering during a twelve-

day period in 1916. Lane v. Wilson, 307 IT. S. 268 (1939).

The United States Supreme Court found the twelve day

period inadequate on the grounds that persons so long

disfranchised could not be expected to comply with the

conditions of registration in so short a time and stated

8

that “ sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of dis

crimination” would not be allowed to operate to deny con

stitutional rights (at p. 275).

As the State of Alabama seeks to exclude appellee from

state supported graduate education solely because he has

previously been denied an adequate education at another

state institution that he was required to attend because of

his race, the lower court must be affirmed. The solution here

is not to oust appellee Franklin from Auburn University,

but rather, for the State of Alabama to provide adequate

education for all of its citizens.

The record shows that Franklin submitted two applica

tions to Auburn University on November 30, 1962, one to

the Registrar and one to the Dean of the Graduate School.

The record also shows that Franklin entered Alabama

State College in September 1958, and graduated in May

1962. Alabama State College was an accredited institution

from December 1957 to December 1961. Franklin had thus

completed three and one-half years of undergraduate edu

cation on an accredited basis with only one semester on an

unaccredited basis. The courses he completed during the

three and one-half years on an accredited basis more than

met the qualifications for admission to the Master of Arts

program at Auburn University (see Exhibit 4). Any con

tention, therefore, that Franklin was unqualified for ad

mission to Auburn or was accorded “ preferential” treat

ment is groundless.

Franklin’s application for admission to the Graduate

School of Auburn University was denied solely on the basis

of race. The State of Alabama’s failure to provide adequate

undergraduate institutions for Negro students, of necessity,

barred them from meeting requirements for admission to

state operated graduate schools. This constitutes a clear

9

denial of the equal protection of law guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment. Moreover, Franklin, though tech

nically not a graduate of an accredited institution, never

theless fulfilled all the requirements for admission to Grad

uate School by obtaining three and one-half years training

at an accredited institution. Any contention that he is un

qualified to attend Auburn University is without merit.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

trial court should be affirmed.

L e r o y D. Clark

Of Counsel

F r e d 1). G r a y

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery 4, Alabama

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y

J a m e s M . N a b r it , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellee

-V

38