Edmondson v. Leesville Concrete Company Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Edmondson v. Leesville Concrete Company Brief Amicus Curiae, 1990. 393e608c-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2dc3d9ce-fbdb-4db7-b449-c6671eb0bfdc/edmondson-v-leesville-concrete-company-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

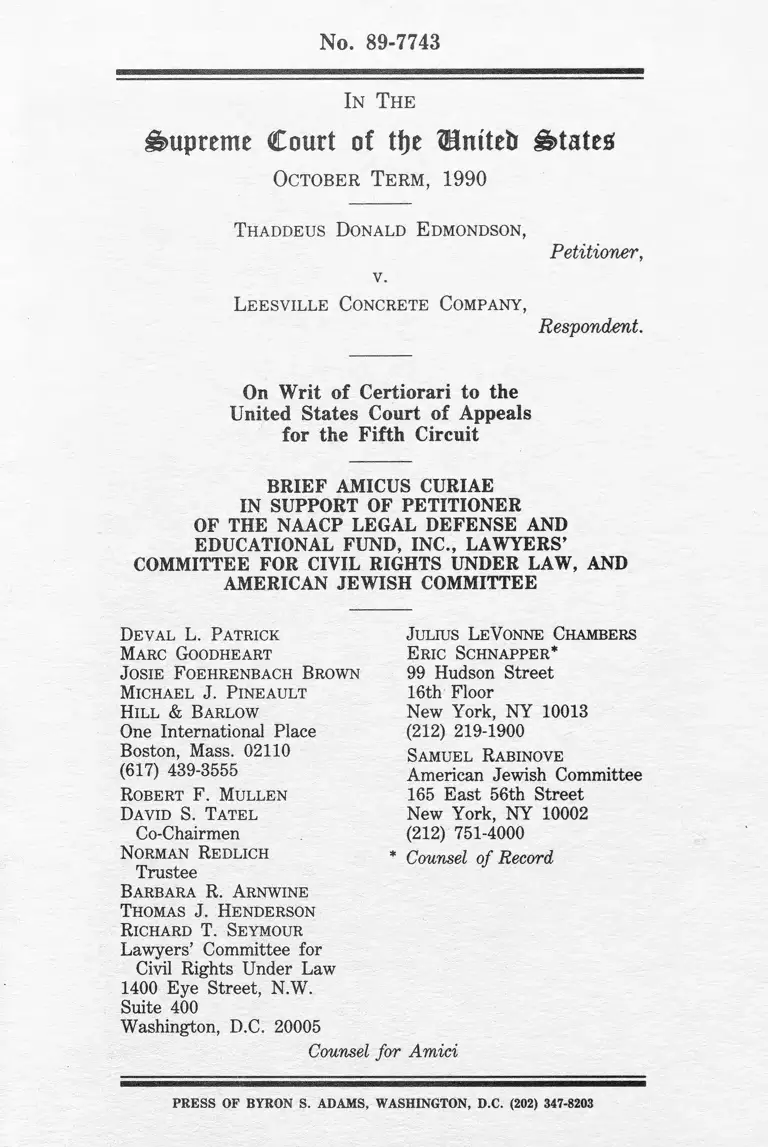

No. 89-7743

I n T h e

Supreme Court of tfje Umtetr states?

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1990

Thaddeus Donald E dmondson,

Petitioner,

v.

Leesville Concrete Company,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AND

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

Deval L. Patrick

Marc Goodheart

J osie Foehrenbach Brown

Michael J. P ineault

Hill & Barlow

One International Place

Boston, Mass. 02110

(617) 439-3555

Robert F. Mullen

David S. Tatel

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Richard T. Seymour

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

Julius LeVonne Chambers

E ric Schnapper*

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Samuel Rabinove

American Jewish Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, NY 10002

(212) 751-4000

* Counsel of Record

Counsel for Amici

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does 28 U.S.C. § 1870 require or authorize a

federal judge to exclude a black prospective juror in a civil

case where a party seeks to exclude that juror by means of

a peremptory challenge because of his or her race?

2. Do 28 U.S.C. § 1862 or 42 U.S.C. § 1981

forbid a federal judge from excluding a black prospective

juror in a civil case where a party seeks to exclude that juror

by means of a peremptory challenge because of his or her

race?

3. Where a civil jury has been assembled by means

of race-based peremptory challenges, does a federal court

have inherent authority to dismiss that jury?

x

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ................. . i

Table of Authorities........ .......... iv

Interest of Am ici.................... 2

S tatutory Provisions Involved ........ 4

Summary of Argument....................... 4

Argument................................ 7

I. This Court Need Not Decide

the Constitutional Questions

Addressed By The Courts Below . 7

II. 28 U.S.C. § 1870 Does Not

Require or Authorized A

Federal Judge In A Civil Case

To Exclude A Black Prospective

Juror Because of a Race-Based

Peremptory Challenge ....... . 10

A. Such A Race-Based Exclusion

Would Be Inconsistent With

The Purpose of Section 1870 12

i i

B. Such A Race-Based Exclusion

Would Be Inconsistent With

Federal Statutes Prohibit

ing Discrimination in Jury

Selection...................... 25

1. 28 U.S.C. § 1862 ........ 26

2. 28 U.S.C. § 1861 ........ 30

3. 28 U.S.C. § 1981 ........ 32

4. 18 U.S.C. § 243 ......... 35

III. The Federal Courts Have In

herent Authority To Dismiss A

Civil Jury Assembled By Means

of Race-Based Peremptory

Challenges ......... 37

Conclusion.................. 50

Appendix A ......... la

Appendix B ................................. 4a

Appendix C .......................... 8a

Appendix D .................................... 10a

1X1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Aldridge v. United States,

283 U.S. 308 (1931) ..................... 40

Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 U.S.-625 (1972)............... 8

Allen v.Hardy, 478 U.S. 255

(1986) ....................................... 44

Ballard v. United States,

329 U.S. 187 (1946)............... 6,41,42,50

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79

(1986) ......................................... Passim

Carter v. Jury Commission of

Greene County, 396, U.S. 320

(1970) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

City of Little Rock v. Reynolds,

No. 90 -l_ .................................... 2

City of Miami v. Cornett,

463 So.2d 399 (Fla. App. 3

Dist. 1985 ......................... 45

Clark v. City of Bridgeport,

642 F. Supp. 890

(D.Conn. 1986)............. . 9,11,22

Commonwealth v. Soares,

387 N.E. 2d 499 (Mass. 1979) ... 18

xv

Cupp v. Naughten, 414 U.S. 141

(1973)................................. 39

Edmondson v. Leesville Concrete

Co., 860 F.2d 1308 (5th Cir.

1989) ........................... 9

Edmondson v. Leesville Concrete

Co., 895 F.2d 218 (5th Cir.

1990) ................................. 13,14.46,48

Esposito V: Buonome,

642 F. Supp. 760 (D.Conn. 1986). 9,23

Fludd v. Dykes, 863 F.2d 822

(5th Cir. 1989)............................. 23

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780

(1966) .......................... 32,33

Gomez v. United States,

104 L.Ed.2d 923 (1989) ................... 8

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

482 U.S. 656 (1987) ....................... 35

Griffin v. Breckenridge,

403 U.S. 88 (1971) ................ 27,34

Hayes v. Missouri, 120 U.S. 68

(1887)............................................ 17

Page

v

Page

Holland v. Illinois,

107 L.Ed.2d 905 (1990) ....... . 6,15,18,44,49

Holley v. J. & S. Sweeping Co.,

192 Cal. Rptr. 74, 143 Cal.

App. 3d 588, (1st Dist. Ct.

App. 1983) ........................... 9

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24

(1948) ............. 34

Kabatchnick v. Hanover-Elm Bldg.

Corp., 331 Mass. 366, 119 N.E.

2d 69 (1954) ......................... 14

King v. County of Nassau,

581 F. Supp. 493 (E.D.N.Y.

1984) ............ 22

Lewis v. United States,

146 U.S. 370 (1892)...... 16

Lommen v. Minneapolis Gaslight

Co., 65 Minn. 196, 68 N.W. 53

(1896).................... 14

Lugar v. Edmondson Oil Co.,

457 U.S. 922 (1982)............... 45

Maloney v. Washington,

690 F. Supp. 687 (N.D. 111.

1988) ........... ................... . 9,22,45-47

v i

Marshall v. United States,

360 U.S. 310 (1959)........ . 40

McCray v. New York,

461 U.S. 961 (1983)............... 28

McNabb v. United States,

318 U.S. 332 (1943)............... 38

Murphy v. Florida,

421 U.S. 794 (1975) .......... 40

Parker v. Downing, 547 So.2d 1180

(Civ. App, Ala. 1988) .......... 23

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

105 L.Ed.2d 132 (1989) ......... 6,33,34

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493

(1972) ................... 20,49

People v. Wheeler,

583 P.2d 755, 148 Cal. Rptr.

890 (1978)............... 48

Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U.S. 537 (1896) ........ . 42

Reynolds v. City of Little Rock,

893 F.2d 1004 (8th Cir. 1990) .. 23

Ristaino v. Ross, 424 U.S. 589

(1976) ................................. 40,43

Page

v i i

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545

(1979) ................................ . 43

Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160 (1976)....................... 33

Sackett v. Ruder, 152 Mass. 397,

25 N.E. 736 (1890) ......................... 14

Smith v. Allwright,

321 U.S. 649 (1944) .. . . . ....... 50

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128

(1940) ........................................... 48

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965).......................... . passim

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880) ......... 6,22,32,33,42,47

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461

(1944) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Taylor v. Louisiana,

419 U.S. 522 (1975) .................... 20

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co.,

328 U.S. 217 (1966) ............... 6,40,41,42,50

United States v. Hasting,

461 U.S. 499 (1983)

Page

v i i i

39

United States v. Shackleford,

18 How. (59 U.S.) 588 (1856) ... 15

Williams v. Coppola, 549 A.2d 1092

(Sup. Ct. Conn. 1986) ........... 11,44

Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261

(1985) .............................. 35

Statutes and Constitutional

Provisions:

Fourteenth Amendment, United

States Constitution ................ 21,23

18 U.S.C. § 243 ........... . 35,36

28 U.S.C. § 1861 ....... 10,30,31,35,36

28 U.S.C. § 1862 ....... 5,26-28,31,35,36

28 U.S.C. § 1863 ...................... 27,28

28 U.S.C. § 1865 ...................... 28

28 U.S.C. § 1866 ...................... 27,28,29

28 U.S.C. § 1870 ...................... Passim

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ............ ......... 5,6,32-36

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ..................... 35

Page

ix

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1866 ......... 21,22,23

Civil Rights Act of 1871 ........... 21,22,23

Civil Rights Act of 1875 ............ 18,26,29

Civil Rights Act of 1965,

Title V II ............................. 16,22

Judiciary Act of 1790 ....................... 15

Jury Selection and Service Act

of 1968 ............................... 5,26,28

1 Stat. 119 ............................ 15

5 Stat. 394 ............................. 15

17 Stat. 282 ..................................... 17

18 Stat. 335 ..................................... 26

Other Authorities:

H.R. Rep. 1076, 90th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1968) ..................... 27,29

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong.,

2d sess. (1872).................. 17,18,19,30,49

Cong, Globe, 43rd Cong., 2d sess.

(1875) ........................................... 30

J. Proffatt, A Treatise on Trial

x

By Jury (1877) ................. 14,15,43

Note, 53 Geo. L.J. 1050 (1965) ... 39

xx

No. 89-7743

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1990

THADDEUS DONALD EDMONDSON,

Petitioner.

v.

LEESVILLE CONCRETE COMPANY,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AND

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

2

INTEREST OF AMICI1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

is a non-profit corporation formed to assist blacks to secure

their constitutional and civil rights by means of litigation.

The Fund’s attorneys represent the plaintiffs in a number of

federal civil rights cases which have been or will be tried

before civil juries. E.g. City o f Little Rock v. Reynolds, No.

90-1.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a nationwide civil rights organization founded in 1963 by

members of the American Bar, at the request of President

Kennedy, to provide legal representation to blacks who were

being deprived of their civil rights.

The American Jewish Committee is a national

membership organization, founded in 1906 for the purpose

of protecting the civil and religious rights of Jews. AJC has

always believed that these rights can be secure for Jews only

'The parties have consented to the filing of this amicus brief.

3

if they axe equally secure for Americans of all faiths, races

and ethnic backgrounds. AJC, therefore, has been actively

involved in the civil rights cause since its inception. The

organization has always urged that civil rights laws be

interpreted broadly to effectuate their purposes. AJC

believes that the exclusion of African Americans from juries

in civil cases through the use of peremptory challenges is a

grievous deprivation based on race which is in violation of

existing law.

4

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The statutory provisions involved are set forth in

Appendix A.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The courts below should not have passed on the

constitutionality of excluding a jury or because of a race-

based peremptory challenge without first deciding whether

federal law authorizes or requires the removal of such jurors.

Section 1870, 28 U.S.C., which establishes peremptory

challenges in civil cases, should be interpreted in a manner

that avoids this constitutional problem.

The essence of the peremptory challenge authorized by

section 1870 is a challenge which does not require proof that

the juror in question should be removed for cause. But that

is a far cry from authorizing litigants to introduce racial

considerations into the jury selection process. The purpose

of peremptory challenges is to enable a party to exclude a

prospective juror who it believes may be biased. But "[a]

5

person’s race simply is ’unrelated to his fitness as a juror’".

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 87 (1986). For that

reason Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 224 (1965),

recognized that the removal of a juror solely because of his

or her race would be a "perverted" use of a peremptory

challenge. Section 1870 should not be construed to authorize

or require removal of a juror where the proposed peremptory

challenge would frustrate rather than advance the creation of

an impartial jury.

The general language of section 1870 must be construed

in the light of the more specific provisions of federal laws

prohibiting racial discrimination in jury selection. Section

1862, 28 U.S.C., expressly provides that "[n]o citizen shall

be excluded from service as a ... juror on account of race."

The word "excluded" is a term of art under the Jury

Selection and Service Act of 1968; jurors removed from a

panel because of a peremptory challenge are said to be

"excluded". Section 1981 of 42 U.S.C. prohibits racial

6

discrimination in jury selection. Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303, 311-12 (1880). Section 1981 applies to

private as well as government action. Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union, 105 L.Ed.2d 132 (1989).

This Court has substantial supervisory power over the

federal courts, and has utilized that authority to prohibit

discriminatory jury selection practices. Thiel v. Southern

Pacific Co,, 328 U.S. 217 (1946) (wage earners); Ballard v.

United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946) (women). The exercise

of that authority is even more appropriate where the

discrimination at issue is racial. The Court’s supervisory

power should be exercised in the circumstances of this case

to protect the right of black prospective jurors to participate

in the administration of justice. "The reality is that a juror

dismissed because of his race will leave the courtroom with

a lasting sense of exclusion from the experience of jury

participation...." Holland v. Illinois, 107 L.Ed.2d 905, 922

7

(Kennedy, J., concurring). Federal judges should not be

knowing accomplices to such discriminatory practices.

ARGUMENT

I. THIS COURT NEED NOT DECIDE THE

CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION ADDRESSED

BY THE COURTS BELOW

The decisions of the courts below are largely devoted to

a constitutional question — whether Batson v. Kentucky, 476

U.S. 79 (1986), should be applied to civil cases. Had the

instant case arisen in state courts, it could be resolved in this

Court only by addressing that constitutional issue. In

Batson, for example, the Kentucky courts had already held

that the disputed exercise of peremptory challenges in that

case was consistent with state law. See 476 U.S. at 84.

The instant case, however, was filed and tried in federal

court. Accordingly, this Court would have no need or

occasion to reach any constitutional question until and unless

it determines that federal law required or authorized the

8

district judge to take the actions whose constitutionality was

challenged below.

It has been the consistent practice of this Court to

decline to address a constitutional question where a case can

be resolved on a non-constitutional basis. Alexander v.

Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 633 (1972). It is, moreover, the

settled policy of this Court "to avoid an interpretation of a

federal statute that engenders constitutional issues if a

reasonable alternative interpretation poses no constitutional

question." Gomez v. United States, 104 L.Ed.2d 923, 932

(1989). In the instant case any legal authority for the

exclusion of the black prospective jurors at issue can only

derive from the federal statute establishing peremptory

challenges in civil cases, 28 U.S.C. § 1870. If the disputed

actions were authorized or required by section 1870 and

those actions are indeed unconstitutional, then section 1870

would to that degree itself be unconstitutional.

9

Despite these two well established prudential rules, the

en banc decision below considered only the constitutional

issue, assuming without explanation or comment that federal

law requires federal judges to implement, indeed protect the

use of, race-based peremptory challenges in civil cases. The

original panel decision in petitioner’s favor, on the other

hand, relied at least in part on a construction of section

1870.2 A number of other lower court decisions regarding

the use of race-based peremptory challenges in civil cases

have specifically dealt with non-constitutional arguments

regarding such challenges.3 This Court noted in Batson the

existence of conflicting lower federal court decisions

regarding whether the issue determined in that case on a

2Edmondson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 860 F.2d 1308, 1312 (5th

Cir. 1989).

3Maloney v. Washington, 690 F. Supp. 687, 690 (N.D.I11. 1988) (28

U.S.C, § 1862); Esposito v. Buonome, 642 F. Supp. 760, 761 (D.Conn.

1986) (28 U.-S.C. §§ 1861, 1862); Clark v. City o f Bridgeport, 645 F.

Supp. 890, 896 (28 U,S.C.§ 1862), 897 ("inherent supervisory power")

(D.Conn. 1986); Holley v. J. & S. Sweeping Co., 192 Cal. Rptr. 74, 77,

143 Cal. App. 3d 588 (1983) (relying on state statutes similar to 28

U.S.C. §§ 1861, 1862).

10

constitutional basis could, in a federal case, be resolved by

reference to the inherent supervisory powers of the federal

courts. 476 U.S. at 82 n. 1.

The non-constitutional issues raised by this case are

fairly comprised in the questions presented by the petition.4

II. FEDERAL LAW NEITHER REQUIRES NOR

PERMITS A FEDERAL JUDGE IN A CIVIL

CASE TO EXCLUDE A BLACK PROSPECTIVE

JUROR BECAUSE OF A RACE-BASED

PEREMPTORY CHALLENGE

Petitioner first objected to the use of race-based

peremptory challenges immediately after respondent had

announced which jurors it wished the trial judge to exclude,

but before the trial court had acted to remove from the jury

box the two black venirepersons, Willie Combs and Wilton

Simmons, to whom respondent objected.5 The issue raised

by this first objection is whether a trial judge is obligated or

permitted by federal law to remove a black prospective juror

"Petition, pp. i (section 1870, ”[]power to supervise"), 7 ("discretion"

of trial judge), 8 (28 U.S.C. § 1861), 9 (28 U.S.C. § 1870).

5Tr. 52-54.

11

if a civil litigant seeks to exercise a race-based peremptory

challenge.

In the present posture of this case we do not know

whether respondent objected to Combs and Simmons solely

because they were black, since the trial court declined to

question counsel for respondent. In other cases, however,

in response to such inquiries, defense attorneys have been

quite brazen in proclaiming their desire to obtain an all-

white jury:

[I]f I had a choice between a white juror and a

black juror, I’m going to take a white juror ...

[W]hy should I put ... my defendants at the mercy

of the people in my opinion who make the most

civil rights claims.6

Counsel for the defendant conceded that race was

a factor.... Although he claimed there were other

reasons, he did not articulate them.7

On the view of the en banc court, the obligations of the trial

6Clarkv. City o f Bridgeport, 645 F. Supp. 890, 894 (D.Conn. 1986).

7Williams v. Coppola, 41 Conn. Supp. 48, 549 A.2d 1092, 1094

(Super. 1986) (emphasis in original).

12

judge in this case would have been the same even if counsel

for respondent had openly proclaimed that he was objecting

to Combs and Simmons expressly and solely because they

were black. The court of appeals insisted that a federal

judge, faced with an avowedly race-based peremptory

objection to a black juror, would be legally required to

remove the black juror at issue, and would be powerless to

correct the racially tainted process that followed. On this

view a Ku Klux Klan leader sued for an alleged act of racial

violence could as a practical matter insist, brazenly and with

success, on trial by an all-white jury, and a present or

retired member of this Court, trying a case by designation,

would be obligated to assist in an avowedly racist jury

selection process.

A. . Such A Race-Based Exclusion Would

Be Inconsistent With The Purpose of

Section 1870

The authority of federal judges in civil cases to exclude

jurors because of peremptory challenges derives from 28

13

U.S.C. § 1870. We contend that section 1870 should be

construed in a manner consistent with the constitutional rule

in Batson. Any prospective juror, regardless of race, may

be excluded by peremptory challenge, and, so long as no

invidious motive is involved, a party is not prohibited from

using peremptory challenges to exclude jurors of the same

race as the opposing party. Where, however, a party seeks

to exercise a peremptory challenge against a venire person

because of his or her race, section 1870 neither requires nor

authorizes a federal judge to remove that prospective juror.

Where a judge declines on this basis to remove a juror, the

objecting party retains the right to exercise that challenge,

but must do so on a non-racial basis.

The en banc panel did not explain why it believed

federal law compels the removal of a black juror because of

a race-based peremptory challenge, other than to assert that

that is "what the rule requires", 895 F.2d at 222, and that

the use of peremptory challenges in civil cases is a

14

"common law" practice of "great age." 895 F.2d at 223,

226. In fact, however, the origin and age of peremptory

challenges in civil cases are entirely different than those of

the challenges accorded criminal defendants.8 The only

form of peremptory challenge recognized under the common

law was that provided to defendants in criminal cases; as a

practical matter, even it was largely limited to defendants in

capital cases. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 211-13 &

n. 9 (1965). Under the common law, no party in a civil

case was accorded any peremptory challenges.9 *

Peremptory challenges in civil cases were virtually

unknown in this country when the Constitution was adopted,

and became widespread only toward the end of the

The exercise of peremptory challenges by defendants in federal

criminal cases may raise somewhat distinct issues which we do not

undertake to address.

9J. Proffatt, A Treatise on Trial by Jury, §§ 155, 163 (1877);

Kabatchnick v. Hanover-Elm Bldg. Corp., 331 Mass. 366, 119 N.E.2d

169, 172 (1954); Sackett v. Ruder 152 Mass. 397, 25 N.E. 736, 738

(1890); Lommen v. Minneapolis Gaslight Co., 65 Minn. 196, 68 N.W.

53, 55 (1896).

15

nineteenth century.10 Consistent with the common law and

state practice, the Judiciary Act of 1790 authorized

peremptory challenges in federal courts only in capital

cases.11 The use of peremptory challenges in federal civil

cases derives from legislation first enacted by Congress in

1872.12 The current provision regarding such challenges, 28

U.S.C. § 1870, provides in pertinent part: "In civil cases,

each party shall be entitled to three peremptory challenges."

Any obligation imposed on federal judges to remove a black

juror because of a race-based peremptory challenge must

derive, if at all, from section 1870.

By according to civil litigants "peremptory challenges,"

Congress undoubtedly meant to create a species of challenge

!0Proffatt, supra, § 163.

" I Stat. .119; see Holland v. Illinois, 107 L.Ed.2d 905, 917 n. 1

(1990).

i217 Stat. 282. In 1840 Congress authorized the federal courts to

adopt local rules regarding jury selection based on state practice. 5 Stat.

394. This legislation was interpreted to authorize the adoption of local

rules regarding peremptory challenges. United States v. Shackleford, 18

How. (59 U.S.) 588 (1856). None of the federal court rules which we

have been able to find from this era contain any references to peremptory

challenges.

16

different than a challenge for cause. The essence of a

peremptory challenge is that the objecting party can obtain

the removal of a juror "without showing any cause at all."

Lewis v. United States, 146 U.S. 370, 376 (1892). But to

provide that a party may obtain the removal of a prospective

juror without demonstrating good cause is a far cry from

providing that the party has an absolute right to remove the

juror, even if its reason be one harmful to the administration

of justice. The law often accords individuals the freedom to

take action arbitrarily, or for no reason at all, and yet

forbids the same action if taken for an invidious motive.

Under Title VII, for example, a private employer is free to

reject a job applicant out of whim or caprice, but is

forbidden to do so on the basis of race or sex.

The central purpose of peremptory challenges is to

permit a party to remove potential jurors who it believes,

but cannot demonstrate, may in fact be biased. A party

may have the strongest reasons to distrust the

character of a juror offered, from his habits and

17

associations, and yet find it difficult to formulate

and sustain a legal objection to him. In such cases

the peremptory challenge is a protection against his

being accepted.

Hayes v. Missouri, 120 U.S. 68, 70 (1887). The legislative

history of section 1870 reveals that, in authorizing

peremptory challenges in civil cases, Congress sought to

provide litigants with a safeguard against biased jurors:

In civil cases in cities, where frequently we get a

merchant on the jury, he may be as much interested

as the man whose case is being tried, and it is

necessary to get him off the jury. We therefore

amend the law by entitling each party in such cases

to three peremptory challenges.13

Resort to a peremptory challenge may also be necessary

where a juror may have taken offense because a party had

sought, without success, to remove that juror for cause.

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 219-20 (1965).

In both Swain and Batson, however, this Court

emphasized that removal of a prospective juror because of

his or her race would be a "perverted" use of a peremptory

l3Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., 3411 (1872) (Rep. Butler).

18

challenge. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U. S. at 91; Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. at 224.14 Such a perverse application

of section 1870 would be entirely inconsistent with the intent

of Congress to facilitate removal of possibly partial jurors:

Competence to serve as a juror ultimately depends

on an assessment of individual qualifications and

ability impartially to consider evidence presented at

a trial.... A person’s race simply is "unrelated to

his fitness as a juror."

Batson, 476 U.S. at 87.15

The larger purpose of peremptory challenges, and of

section 1870, is to assure that civil cases will be decided by

juries "which in fact and in the opinion of the parties are

14See also Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387 N.E. 2d

499, 515 n. 28 ("what is involved here is an apparent perversion of a

system designed to preclude prejudice"), cert, denied 444 U.S. 881

(1979).

l5In enacting the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which forbad racial

discrimination in the selection of federal or state juries, Congress

emphatically rejected objections that blacks as a race could not be trusted

to fairly adjudicate the rights of whites. Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong. 2d

sess., app. 218 (Rep. McHenry), app. 598-99 (Rep. Rice) (1972). These

debates occurred within a month of passage of the peremptory challenge

provision now codified in section 1870. It is inconceivable that Congress

intended to authorize civil litigants to remove black jurors on the very

racist premise that Congress spumed in passing the Civil Rights Act.

19

fair and impartial." Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. at 212;

see also id. at 218, 222; Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. at

91. .

Peremptory challenges, by enabling each side to

exclude those jurors it believes will be most partial

toward the other side, are a means of

"eliminating] extremes of partiality on both sides,"

... thereby "assuring the selection of a qualified and

unbiased jury."

Holland v. Illinois 107 L.Ed.2d 905, 919 (1990). When

section 1870 was first enacted, Representative Butler

explained, "What we aim at here is to get a fair jury."16

The exclusion of black prospective jurors by means of

race-based peremptories, however, would impair the very

impartiality which Congress intended peremptory challenges

to enhance. Regardless of whether the person making the

selections is a government agent or a private party, the

exclusion of jurors on the basis of race

16Cong. Globe 42d Cong., 2d sess., 3412 (1872).

20

cast[s] doubt on the integrity of the whole judicial

process. [It] create[s] the appearance of bias in

the decision of individual cases, and [it] increase[s]

the risk of actual bias as well.

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 532 n. 12 (1975).

As long as there are significant departures from the

cross sectional goal, biased juries are the result -

- biased in the sense that they reflect a slanted view

of the community they are supposed to represent.

Id. at 529 n. 7.

[Tjhe exclusion from jury service of a substantial

and identifiable class of citizens has a potential

impact that is too subtle and too pervasive to admit

of confinement to particular issues or particular

cases.... It is in the nature of the practices ... that

proof of actual harm, or lack of harm, is virtually

impossible to adduce.

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 503-04 (1972) (Opinion of

Justice Marshall). The state courts of Massachusetts,

Connecticut, California, Florida and New York have all

concluded from practical experience that the exercise of

race-based peremptory challenges increases substantially the

risk that the resulting jury will be biased against members

21

of the excluded race. We set forth excerpts from those state

court opinions in Appendix B.

It is particularly unlikely that in 1872, only four years

after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress

could have intended by enacting section 1870 to require

federal judges to accede to the desire of civil litigants to

purge blacks systematically from federal juries. By adopting

the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1871, Congress had

conferred upon the federal courts primary responsibility for

redressing violations of the rights of the newly freed slaves.

Congress could have been under no illusion about how an

all-white federal jury in any of the former confederate states

would likely dispose of the civil rights claims of a black

plaintiff.

[I]t required little knowledge of human nature to

anticipate that those who had long been regarded as

an inferior and subject race would ... be looked

upon with jealousy and positive dislike.... "The

right of trial by jury" ... is ... guarded by statutory

enactments intended to make impossible ...

"packing juries." It is well known that prejudices

often exist against particular classes in the

22

community, which sway the judgment of jurors,

and which, therefore, operate in some cases to deny

to persons of those classes the full enjoyment of

that protection which others enjoy.... The framers

of the [Fourteenth] Amendment must have known

full well the existence of such prejudice.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 306-09 (1880). It

is difficult to believe that the Reconstruction era Congress,

having largely rewritten the federal Constitution and enacted

revolutionary legislation in order to afford badly needed

protection to the freedmen, could have intended section 1870

to license a scheme of race-based peremptory challenges that

would have subverted all the legislative efforts of previous

years. That danger is far from past; with the exception of

the instant case, it appears that all of the reported federal

civil cases in which parties have sought to purge black jurors

involved claims under either the Civil Rights Act of 1866 or

the Civil Rights Act of 1871.17

17Clark v. City o f Bridgeport. 645 F.Supp. 890 (D.Conn. 1986)

(1871 Civil Rights Act); King v. County o f Nassau, 581 F.Supp. 493

(E.D.N.Y. 1984) (Civil Rights Acts of 1866, 1871, and 1964); Maloney

v. Washington, 690 F.Supp. 687 (N.D.I11. 1988), 584 F. Supp. 1263,

23

That Congress did not intend section 1870 to sanction

race-based peremptory challenges in civil cases is confirmed

by the fact that the act of 1872 governed as well the exercise

of peremptory challenges in criminal cases.18 Although

Swain and Batson reached differing conclusions regarding

the appropriate method of proof, no member of this Court

has doubted that the exercise of a race-based peremptory

challenge by a government prosecutor would, if proven,

constitute the type of invidious government action forbidden

by the Constitution. In 1872, when many framers of the

Fourteenth Amendment were still members of the House and

Senate, there would assuredly have been an outcry of protest

had Congress understood the proposed legislation to

1264-66 (N.D.I11. 1984) (Civil Rights Act of 1866 and 1871); Reynolds

v. City o f Little Rock, 893 F.2d 1004 (8th Cir. 1990) (Civil Rights Act

of 1871); Fludd v. Dykes, 863 F.2d 822, 824 (5th Cir. 1989) (Civil

Rights Act of 1871); Esposito v. Buonome, 642 F.Supp, 760 (D.Conn.

1986), 647 F. Supp. 580, 580 (D.Conn. 1986) (Civil Rights Act of 1871;

see also Parker v. Downing, 547 So.2d 1180 (Civ. App. Ala. 1988)

(Civil Rights Act of 1871).

18See Appendix C.

24

authorize federal prosecutors to exercise, and federal judges

to implement, race-based peremptory challenges in criminal

cases. If the "peremptory challenges" authorized by the

1872 Act in criminal cases do not encompass race-based

objections, it is difficult to see how the same phrase in the

same statute could have a different meaning as applied to

civil cases.

Undeniably the language and legislative history of

section 1870 do not address directly the question of whether

race-based peremptory challenges may be used to exclude

minorities from a jury. But it is, at the least, a "reasonable

alternative interpretation" of section 1870 that that provision

does not authorize such discrimination; section 1870 should

be construed in that manner to avoid the constitutional

difficulties addressed by the courts below. As we set forth

in part III, the federal courts possess inherent authority to

forbid jury selection practices that discriminate on the basis

or race. The general language of section 1870 certainly

25

cannot be said to evince any clear congressional intent to

restrict that judicial power.

B. Such A Race-Based Exclusion Would

Be Inconsistent With Federal Statutes

Prohibiting Discrimination In Jury

Selection

Even if the general provisions of section 1870,

read in isolation, might appear to authorize removal of a

juror because of a race-based peremptory challenge, the

illegality of excluding a juror on that basis is clear under

the more specific congressional legislation regarding racial

discrimination in jury selection. Section 1870 should be

interpreted in a manner consistent with these anti-

discrimination laws. Two federal statutes prohibit

discriminatory jury selection in broad language fully

applicable to the exercise of race-based peremptory

challenges by either government or private attorneys. Two

other statutes confirm that that was precisely the intent of

Congress.

26

1. 28 U.S.C. § 1862

Section 1862, adopted in its present form as part

of the Jury Selection and Service Act of 1968, provides:

No citizen shall be excluded from

service as a grand or petit juror in

the district courts of the United

States ... on account of race, color,

religion, sex, national origin, or

economic status.

Petitioner objected in the district court that venire-persons

Combs and Simmons had indeed been excluded on account

of their race from service as petit jurors in this case. The

literal language of section 1862 is all-encompassing; it

recognizes no exception for instances in which the

discriminatory exclusion was achieved by means of a

peremptory challenge, or where the invidious motive was

that of a private attorney or litigant. Section 1862, which

derives from the Civil Rights Act of 1875,19 should like

1918 Stat, 335.

27

"other Reconstruction civil rights statutes ... be[] ...

1 accord[ed] ... a sweep as broad as [its] language.’" Griffin

v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88, 97 (1971).

The manifest purpose of section 1862 was to provide

"for the selection, without discrimination, of Federal grand

and petit juries."20 Congress believed that juries from which

racial minorities had been systematically excluded would be

more likely to return biased verdicts.21 Other provisions of

the 1968 legislation established detailed procedures designed

to assure that minorities were not excluded from jury

venires, either intentionally or because of practices with

discriminatory effects. 28 U.S.C. §§ 1863-1866. Congress

could not have intended to permit litigants to defeat this

carefully crafted legislative scheme through the use of race-

based peremptory challenges. "There is no point in taking

elaborate steps to ensure that Negroes are included on

J0H.R. Rep. No. 1076, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968), reprinted in

1968 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News, 1792, 1792.

J1H.R. Rep. No. 1076, 90thCong., 2d Sess., 8 (1968).

28

venires simply so they can then be struck because of their

race by a ... use of peremptory challenges." McCray v.

New York; 461 U.S. 961, 968 (1983). (Marshall J.,

dissenting from denial of certiorari).

The deliberate use of the term "excluded" in section

1862 leaves no doubt that the prohibition against

discrimination applies to the use of peremptory challenges.

In the Jury Selection and Service Act the word "excluded"

is a term of art. Jurors deleted from a venire or removed

from a jury panel are, depending on the reason, referred to

in the Act as having been "disqualified,"22 "excused",23

"exempt"24 or "excluded".25 The phrasing of the statute was

based on "a careful articulation of the grounds upon which

“28 U.S.C. § 1865 ("qualifications" of English literacy, etc.).

^28 U.S.C. §§ 1863(b)(5) (jurors "excused" because of "extreme

inconvenience"), 1866(c)(1).

2428 U.S.C. § 1863(b)(6) ("exemptions" for public officials).

M28 U.S.C. §§ 1866(c)(2) (jurors "excluded" because of partiality),

1866(c)(4).

29

persons may be eliminated from jury service as:

’disqualified,’ ’exempt,’ ’excused’ or ’excluded.’"26 Under

section 1866(c) a juror can be removed from a jury panel at

the behest.of a party only for cause or if "excluded upon

peremptory challenge as provided by law." (Emphasis

added).

The congressional purpose underlying the Civil Rights

Act of 1875, which first prohibited racial discrimination in

jury selection, would clearly be frustrated if black

prospective jurors could be purged by means of race-based

peremptory challenges. The principle concern of Congress

was that all-white juries would be hostile to black litigants.

Representative Morton argued:

I ask if with the prejudices against the colored race

entertained by the white race ... the colored man

enjoys the equal protection of the laws, if the jury

that is to try him for a crime or determine his

property must be made up exclusively of the white

race?.... I ask ... whether the colored men ...

have the equal protection of the laws when the

26H. R. Rep. No. 1076, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968), reprinted in

1968 U.S. Code Cong, and Admin. News, 1792, 1802.

30

control of their right to life, liberty, and property

is placed exclusively in the hands of another race

of men, hostile to them, in many respects

prejudiced against them, men who have been

educated and taught to believe that colored men

have no civil and political rights that white men are

bound to respect.27

It was said that blacks could not "obtain justice in State

courts because colored fellow citizens are excluded from the

juries."28 An end to discrimination in the selection of jurors

was sought so that a black litigant might have among the

jurors deciding his claims "those who would naturally have

an interest in him."29

(2) 28 U.S.C. § 1861

Section 1861, also adopted as part of the Jury

Selection and Service Act of 1968, provides in pertinent

/ part:

27Cong. Globe, 43rd Cong. 2d sess., 1793-95 (1875); see also id.

at 427 (Rep. Stowell), 945 (Rep. Lynch), 1863 (Sen. Morton).

^Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d sess., 823 (Sen. Sumner) (1872).

29Cong. Globe, 43rd Cong. 1st sess., 3455 (Sen. Frelinghuysen)

(1874).

31

It is the policy of the United States

that all litigants in Federal courts

entitled to trial by jury shall have the

right to grand and petit juries

selected at random from a fair cross

section of the community in the

district or division wherein the court

convenes.

Section 1861 is an authoritative guide to the correct

interpretation of the jury selection provisions of Title 28,

applicable to section 1862 as well as section 1870.

If, as petitioner alleges, prospective jurors Combs and

Simmons were removed because they were black, the

resulting jury was not "selected at random from a fair cross

section of the community." Rather, the jury which tried this

case was selected on the basis of race from what was, until

the exercise of the peremptory challenges, a fair cross

section of the community. Such a selection process flies in

the face of the congressional policy announced in section

1861.

32

(3) 42 U.S.C. § 1981

Section 1981 provides in part that

All persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory ...

to the full and equal benefit of all

laws and proceedings for the security

of persons and property as is enjoyed

by white citizens.

In Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966), and Strauder v.

West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880), this Court held that the

provision assuring the "full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings" guaranteed to a black litigant "the right to have

his jurors selected without discrimination on the ground of

race." 384 U.S. at 798, citing Strauder, 100 U.S. at 311-

12. Section 1981 is violated when prospective jurors of the

same race as a black litigant are excluded on account of

race, since the proceedings which follow are different than

those which would be afforded to whites, a difference

sought solely because of the race of the black litigant and

33

the excluded jurors.30 The discriminatory jury selection

prohibited by section 1981 can as readily be achieved by

peremptory challenges as by manipulation of the venire list;

both forms of discrimination are equally prohibited.

Rachel and Strauder involved criminal prosecutions.

But the application of section 1981 is not limited to

discrimination by government officials. This Court held in

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160, 170 (1976), that "§

1981 ... reaches purely private acts of racial

discrimination." The Court unanimously reaffirmed that

interpretation of section 1981 in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 105 L.Ed.2d 132, 150 (1989) ("[W]e ... adhere to

our decision in Runyon that § 1981 applies to private

conduct"). If a private party had resorted to threats or

30The equal benefit clause encompasses as well a guarantee that

blacks will be accorded to the same degree as whites the protection

afforded by state criminal proceedings. A statute, like certain of the

slave codes, attaching a lesser degree of criminality to a crime against a

black victim would violate section 1981. Thus section 1981 would apply

to some race-based peremptories by criminal defendants, i.e. a

peremptory challenge, in the trial of an inter-racial crime, intended to

remove prospective jurors of the same race as the victim.

34

violence to prevent blacks from serving on the jury in this

case, section 1981 would undeniably have afforded

petitioner, -and the prospective jurors, redress. See Griffin

v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88, 97-104 (1971). A fortiori

section 1981 applies when a federal judge is asked "to

compel ... discriminatory action [in the] federal courts."

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24, 35-36 (1948).

Section 1981 would clearly apply to peremptory-based

discriminatory jury selection in a contract action brought by

a black plaintiff. The contract clause of section 1981

"covers wholly private efforts to impede access to the

courts" by a black litigant seeking to enforce contractual

rights. Patterson, 105 L.Ed.2d at 151 (emphasis in

original). Surely the equal benefit clause of section 1981

provides the same protection when a plaintiffs claim sounds

in tort rather than in contract. Were that not the case,

section 1981 would preclude race-based peremptories in state

court contract actions, but would allow the use of race-

35

based peremptories in a civil rights claim brought in federal

court under sections 1981 and 1983. See Goodman v.

Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656, 660-64 (1987); Wilson v.

Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985).

4. 18 U.S.C. § 243

• The only federal jury discrimination statute that

contains the kind of state action requirement adopted by the

court of appeals in this case is the criminal prohibition

against discriminatory jury selection. The wording of the

criminal provision is significant because it is deliberately

narrower than sections 1861, 1862 and 1981. Section 243

of Title 18 provides:

No citizen possessing all other

qualifications which are or may be

prescribed by law shall be

disqualified for service as grand or

petit juror in any court of the United

• States, or of any State on account of

race, color, or previous condition of

servitude; and whoever, being an

officer or other person charged with

any duty in the selection or

summoning of jurors, excludes or

fails to summon any citizen for such

36

cause, shall be fined not more than

$5,000.

Section 243 is applicable only to "an officer or other person

charged with any duty in the selection or summoning of

jurors." Clearly counsel for respondent could not have been

prosecuted under section 243, even if his racial motives

were clear beyond any reasonable doubt.

Equally clearly, however, section 243 demonstrates that

Congress knew full well how to place a state action

requirement in federal law, and did so expressly when it

desired such a limitation. Having enacted four different

statutes prohibiting racial discrimination in the jury selection

process, Congress deliberately chose to place a state action

requirement only in section 243. The only' plausible

interpretation of this careful distinction is that Congress did

not desire to limit sections 1861, 1862 and 1981 to conduct

by "an officer", but intended those provisions to extend to

all race-based action excluding blacks from juries, regardless

of the status of the individuals involved.

37

III. THE FEDERAL COURTS HAVE INHERENT

AUTHORITY TO DISMISS A CIVIL JURY

ASSEMBLED BY MEANS OF RACE-BASED

PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES

After the district judge in this case had removed

prospective jurors Combs and Simmons, and empaneled the

jury that ultimately heard the case, petitioner’s objection was

renewed.31 At this juncture the issue was not whether

section 1870 authorized the removal of Combs and

Simmons, but whether the resulting jury should be permitted

to try the case, or should be stricken because of the manner

in which it was assembled. The district judge and the en

banc court concluded that the jury in a case such as this

could not be dismissed unless the exclusion of Combs and

Simmons was itself unlawful. On the view of the en banc

majority, if the removal of those black prospective jurors

was not unconstitutional state action, "then the courts hold

no warrant to interfere" with the resulting jury. (895 F.2d

at 221).

31Tr. 54-63.

38

The courts below adhered to an unduly constricted view

of their authority, and responsibility, in dealing with jury

panels assembled by means of race-based peremptory

challenges. The federal courts possess broad inherent

authority to take measures necessary to protect the integrity

of judicial proceedings. This Court holds commensurately

extensive supervisory powers over the manner in which

proceedings are conducted in the federal courts. In the

decades since McNabb v. United States, 318 U.S. 332

(1943), the Court has exercised that authority in a wide

variety of circumstances. McNabb explained that the

supervisory power could be invoked to "maintain[] civilized

standards of procedure" and has been "guided by

considerations of justice." 318 U.S. at 340-41. Surveying

the diverse situations in which this power has been

exercised, one commentator observed that the "common

39

denominator of its usage is a desire to maintain and develop

standards of fair play...."32

This Court may interfere with the judgment or

proceedings of a state court only when a violation of federal

law or applicable constitutional requirements has occurred.

But in dealing with federal proceedings, the federal courts

have broader inherent authority, and "may, within limits,

formulate procedural rules not specifically required by the

Constitution or the Congress." United States v. Hasting,

461 U.S. 499, 505 (1983). "[Tjhe appellate courtfs] ... may

... require [trial courts] to follow procedures deemed

desirable from the viewpoint of sound judicial practice

although in no-wise commanded by statute or by the

Constitution." Cupp v. Naughten, 414 U.S. 141, 146 (1973).

In a number of instances the exercise of this supervisory

power has led this Court to overturn judgments in federal

“Note, 53 Geo. L J . 1050, 1050 (1965).

40

cases despite sustaining similar state court judgments in

essentially identical circumstances.33

Few practices have greater potential impact on the

integrity of the judicial process than the manner in which

jurors are selected. The selection process is a sensitive one,

all too easily skewed to unduly favor one party or group,

and to undermine public confidence in the fairness of the

federal courts. In Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S.

217 (1946), this Court invoked its supervisory power to

overturn a civil jury verdict because wage earners had been

systematically excluded from the jury at issue. That

exclusion, the Court concluded, although not the subject of

any express statutory prohibition, was inconsistent with "the

high standards of jury selection" that ought to prevail in

federal courts, 328 U.S. at 225, and tainted the resulting

verdict with "class distinctions and discriminations which are

Compare Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 (1959) with

Murphy v. Florida, 421 U.S. 794 (1975); compare Aldridge v. United

States, 283 U.S. 308 (1931), with Ristaino v. Ross, 424 U.S. 589 (1976).

41

abhorrent to the democratic ideals of trial by jury." 328

U.S. at 220. In Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187

(1946), the Court again invoked its supervisory authority to

forbid federal district courts from systematically excluding

women from the jury rolls. The Court explained that the

use of all-male juries "may at times be highly prejudicial to

the defendants," and that such exclusionary practices worked

an "injury to the jury system, to the law as an institution,

to the community at large, and to the democratic ideal

reflected in the processes of our courts." 329 U.S. at 195.

This Court held that the juries in Thiel and Ballard

should not have been permitted to try those cases, even

though the manner in which the juries had been selected

could not be said to have violated a specific, identified

statutory or constitutional provision. The fact that a skewed

or tainted jury may have been the result of peremptory

challenges, rather than of the manner in which the venire

was composed, does not reduce the Court’s supervisory

42

authority. If, as a result of happenstance, the jury selected

to hear a police brutality case was composed of twelve

former police officers or of twelve ex-convicts, no sensible

judge would hesitate to strike that jury and assemble a new

one. The judicial responsibility is surely no less when the

skewed nature of a jury is the result, not of coincidence, but

of deliberate racial manipulation of the jury selection

process.

The exclusionary practices in Ballard and Thiel

concerned women and wage earners, respectively. The

deliberate exclusion of blacks from civil and criminal juries

is an abuse of unique gravity in our constitutional system.

Discrimination against black prospective jurors was first

condemned by this Court 110 years ago in Strauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880); over the course of the last

century, even when other forms of discrimination were

tolerated for a period under the ill-starred decision in Plessy

v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), this Court was ceaseless

43

in its efforts to eradicate race-based jury discrimination. If

the federal courts have inherent supervisory authority to deal

with jury discrimination involving women and wage earners,

a fortiori they possess and should exercise that authority

when the discrimination at issue is directed at racial

minorities.

The deliberate exclusion of black jurors has a unique

and long recognized capacity to destroy public confidence in

the fairness of the courts.

Discrimination on the basis of race, odious in all

aspects, is especially pernicious in the

administration of justice.... [It] destroys the

appearance of justice and thereby casts doubt on the

integrity of the judicial process. The exclusion ...

of Negroes ... impairs the confidence of the public

in the administration of justice.... The harm ... is

to society as a whole.

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545, 555-56 (1979). Such

practices inevitably suggest "that justice in a court of law

may turn upon the pigmentation of skin." Ristaino v. Ross,

424 U.S. 589, 596 n. 8 (1976). The decision in Batson was

based on an express recognition that the exclusion of black

44

prospective jurors by means of race-based peremptories

would "undermine public confidence in the fairness of our

system of justice." 476 U.S. at 87. The court in Williams

v. Coppola, 41 Conn. Supp. 48, 549 A.2d 1092, 1101

(Super. 1986), put the matter more bluntly:

The use of peremptory challenges to remove all the

possible jurors of one of the party’s race seriously

impairs the perception of justice. Members of a

minority, under those circumstances, could never

feel that they received a fair trial.

This Court has reiterated that maintaining public confidence

in the fairness of the courts was a key purpose of the

decision in Batson. Holland v. Illinois, 107 L.Ed.2d 905,

922 (Kennedy, J., concurring); Allen v. Hardy, 478 U.S.

255, 259 (1986).

The decisions below offer subtle analyses of the concept

of state action. But such legal niceties are entirely irrelevant

to the indelible impression that the exercise of race-based

peremptory challenges can have on public confidence.

Regardless of whether the action of a judge in implementing

45

such challenges is or is not technically unconstitutional, the

parties, the public and the prospective jurors will inevitably

regard the judge as "an accomplice to racial discrimination

in the courtroom." Maloney v. Washington, 690 F. Supp.

687, 690 (N.D.I11. 1988). When a racially hand-picked all-

white jury in a racially sensitive case returns a verdict in

favor of the white litigant, community concerns about

unfairness will not be stilled by an admonition to read Lugar

v. Edmondson Oil Co., 457 U.S. 922 (1982). The decision

of the Florida courts to bar race-based peremptory

challenges in civil cases was the result, in part, of the state’s

tragic experience with the consequence of a collapse of

public confidence in racially skewed juries.34 In "the

Kingdom of Heaven" even hand-picked all-white juries might

be relied on to do justice between black and white litigants,

cf. Carter v. Jury Commission o f Greene County, 396 U.S.

320, 342 (1970) (Douglas, J., concurring); but here on earth

34We set forth in Appendix D excerpts from the trial judge’s opinion

in City o f Miami v. Cornett, 463 So.2d 399 (Fla. App. 3 Dist. 1985).

46

the public understandably shares the view of those who

exercise race-based peremptories that the exclusion of black

prospective jurors is likely to tilt the scales of justice in

favor of a white litigant.

A court which condones the use of race-based

peremptories does not, as the en banc court suggested,

simply provide a "level playing field" on which the parties

may do battle. (895 F.2d at 222). The decision below also

gives the parties license to do battle with racial weapons of

unique destructiveness; under that decision overtly race-

based jury selection would inevitably become a part, perhaps

the most critical part, of the trial of racially sensitive cases,

if not of all cases in which the parties are of different races.

The racially explicit brawling to which this would lead is

starkly illustrated by Maloney v. Washington, 690 F. Supp.

687 (N.D.I11. 1988). The white plaintiffs in Maloney,

alleging that they were the victims of reverse discrimination,

brought suit against the black mayor of Chicago. Although

47

the gravamen of the complaint was an insistence that all

government action should be strictly color blind, the

plaintiffs "apparently concluded that they would prefer to

have their case tried by members of their own race." Id.

at 688. The plaintiffs utilized all of their peremptory

challenges against blacks; the defendants responded by using

all of their challenges against whites. When a mistrial was

declared on unrelated grounds, the trial judge warned

counsel not continue making race-based peremptory

challenges; counsel for both sides disregarded that

admonition, forcing the court to strike the second jury and

impose sanctions. 690 F.2d at 689-92.

■ Strauder and its progeny contemplated that the courts

would be a safe harbor from the often virulent bigotry of an

earlier era; today, when overt racism is regarded as

unacceptable in most aspects of American life, the decision

below threatens to turn the federal courts into an arena when

express exploitation of race will be entirely acceptable, and

48

even commonplace. Federal judges should not stand idly by

while civil cases are manipulated through manifestly racial

tactics. "For racial discrimination to result in ... exclusion

from jury service ... is at war with our basic concepts of a

democratic society." Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130

(1940). "[I]n such a war the courts cannot be pacifists."

People v. Wheeler, 583 P.2d 748, 755, 148 Cal. Rptr. 890

(1978).

The Fifth Circuit insisted that by tolerating race-based

peremptones the courts merely took a position of neutrality

with regard to the litigants "in their dealings with each

other." (895 F.2d at 225). But race-based peremptories,

even if resorted to equally by both sides, have a direct

impact on innocent third parties — the jurors excluded on

account of race.

[T]he exclusion of Negroes from jury service ...

denies the class of potential jurors the "privilege of

participating equally ... in the administration of

justice," ... and it stigmatizes the whole class, even

those who do not wish to participate, by declaring

them unfit for jury service and thereby putting "a

49

brand upon them ... an assertion of their

inferiority."

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 499 (1972) (opinion of Justice

Marshall). Swain expressly recognized the injury caused to

prospective jurors when

the peremptory system is being used to deny the

Negro the same right and opportunity to participate

in the administration of justice enjoyed by the white

population. Th[is] en[d] the peremptory challenge

is not designed to facilitate or justify.

380 U.S. at 224.35 "The reality is that a juror dismissed

because of his race will leave the courtroom with a lasting

sense of exclusion from the experience of jury

participation...." Holland v. Illinois, 107 L.Ed.2d 905, 922

(1990) (Kennedy, J., concurring). The right to participate

as a juror in the administration of justice, like the right to

participate-as a voter in the democratic process, cannot be

denied on account of race, even if the impetus for that denial

35Compare Cong. Rec., 42nd Cong., 2d sess., 900 (1872) (Sen.

Edmunds) (prohibition against discrimination in jury selection required

so that the black "population shall feel and the white population shall feel

that they participate equally and fairly in the administration of justice and

in the protection of private rights.")

50

comes to some degree from individuals who are not on the

public payroll. See Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953);

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944).

The jury selection practices at issue in this case are in

all respects more harmful to the due administration of justice

than the practices condemned in Thiel and Ballard. The

Court should exercise its supervisory power to direct the

federal courts not to try cases before juries selected by

means of race-based peremptory challenges.

CONCLUSION

Were the Court to reach the constitutional question

considered below, we would urge the Court to hold that in

a civil case the removal of a prospective juror because of a

race-based peremptory challenge is unconstitutional. The

instant case, however, may more appropriately be resolved

on non-constitutional grounds. For the above reasons the en

51

banc decision of the court of appeals should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER*

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

DEVAL L. PATRICK

MARC GOODHEART

JOS IE FOEHRENBACH BROWN

MICHAEL J. PINEAULT

Hill & Barlow

One International Place

Boston, Mass. 02210

(617) 439-3555

ROBERT F. MULLEN

DAVID S. TATEL

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

BARBARA ARNWINE

THOMAS J. HENDERSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

52

SAMUEL RABINOVE

American Jewish Committee

165 East 65th Street

New York, New York 10002

(212) 751-4000

Counsel for Amici

*Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 243, 18 U.S.C., provides:

No citizen possessing all

other qualifications which are or may

be prescribed by law shall be

disqualified for service as grand or

petit juror in any court of the United

States, or of any State on account of

race, color, or previous condition of

servitude; and whoever being an

officer or other person charged with

any duty in the selection or

summoning of jurors, excludes or

fails to summon any citizen for such

cause, shall be fined not more than

$5,000.

Section 1861, 28 U.S.C., provides:

Declaration of Policy. It is the

policy of the United States that all

litigants in Federal Courts entitled to

trial by jury shall have the right to

grand and petit juries selected at

random from a fair cross-section of

the community in the district or

division wherein the court convenes.

It is further the policy of the United

States that all citizens shall have the

opportunity to be considered for

service on grand and petit juries in

the district courts of the United

l a

States, and shall have an obligation

to serve as jurors when summoned

for that purpose.

Section 1862, 28 U.S.C., provides:

Discrimination Prohibited. No

citizen shall be excluded from

service as a grand or petit juror in

the district courts of the United

' States and the Court of International

Trade on account of race, color,

religion, sex, national origin, or

economic status.

Section 1870, 28 U.S.C., provides in pertinent part:

Challenges. In civil cases, each

party shall be entitled to three

peremptory challenges. Several

defendants or several plaintiffs may

be considered as a single party for

the purposes of making challenges,

or the court may allow additional

peremptory challenges and permit

them to be exercised separately or

jointly.

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C., provides in pertinent part:

All persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue,

be parties, give evidence, and to the

full and equal benefit of all laws and

2a

proceedings for the security of

persons and property as is enjoyed

by white citizens....

3a

APPENDIX B

State Decisions Regarding The Impact of

Race-Based Peremptories

(1) Commonwealth v. Soares, 387 N.E.2d 499 (Sup. Jud

Ct. Mass. 1979). The lack of any prohibition against race

based peremptory to challenges

"would leave the right to a jury drawn from a

representative cross-section of the community

wholly susceptible to nullification through the

intentional use of peremptory challenges to exclude

identifiable segments of the community.... It is

[the] very diversity of opinion among individuals,

some of whose concepts may well have been

influenced by their group affiliations, which is

envisioned when we refer to ’diffused impartiality.’

No human being is wholly free of the interests and

preferences which are the product of his cultural,

family, and community experience. Nowhere is the

dynamic commingling of the ideas and biases of

such individuals more essential than inside the jury

room....

Given an unencumbered right to exercise

peremptory challenges ... [t]he party identified with

the majority can altogether eliminate the minority

from the jury.... The result is a jury in which the

subtle biases of the majority are permitted to

operate, while those of the minority have been

silenced."

4a

387 N.E.2d at 515-18. When a party

"challenges a Negro in order to get a white juror in

his place, he does not eliminate prejudice in

exchange for neutrality; ... [H]e is, in fact, willy

nilly taking advantage of racial divisions to the

detriment of the [opposing party]."

387 N.E.2d at 516 n. 31.

"The absence of a group from petit juries in

communities ... may lead to jury decision making

based on prejudice rather than reason. White

jurors, satisfied that blacks will never sit in

judgment upon themselves or their white neighbors,

can safely exercise their prejudices."

387 N.E.2d at 512 n. 20.

(2) People v. Wheeler, 583 P.2d 748, 761, 148 Cal.

Rptr. 890 (1978):

"[w]hen a party ... peremptorily strikes all

[members of a racial minority] for that reason

alone, he ... frustrates the primary purpose of the

representative cross-section requirement. That

purpose ... is to achieve an overall impartiality by

allowing the interaction of the diverse beliefs and

values the jurors bring from their group

experiences. Manifestly if jurors are struck simply

because they hold those very beliefs, such

interaction becomes impossible and the jury will be

dominated by the conscious or unconscious

prejudices of the majority."

5a

(3) Williams v. Coppola, 549 A. 1092, 1097-98, 41

Conn. Sup. 48 (Super. 1986):

"If a party were to have the unfettered right to

exercise peremptory challenges for any reason, the

right to trial by an impartial jury would lose its

meaning. So, if blacks could be struck from the

jury merely because they were black, there would

be no purpose in taking elaborate steps to guarantee

their inclusion in the venire. ... Tools that deprive

a party of a trial by an impartial jury or even the

perception of such a trial have no place in a

constitutional democracy."

(4) People v. Thompson, 435 N.Y.S. 2d 739, 751-

52, 79 A.D.2d 87 (1981):

”[W]e agree ... that viewing the jury as a whole,

permitting the unencumbered exercise of

peremptory challenges does anything but ensure the

selection of an impartial jury.... [T]he unfettered

use of the peremptory challenge on the basis of

race may, in and of itself, ultimately defeat the ...

right to trial by a'jury drawn from a fair cross-

section of the community."

(5) State v. Neil. 457 So.2d 481, 486 (Fla. 1984):

"Article I, section 16 of the Florida Constitution

guarantees the right to an impartial jury.... The

primary purpose of peremptory challenge is to aid

and assist in the selection of an impartial jury. It

was not intended that such challenges be used

solely as a scalpel to excise a distinct racial group

6a

from a representative cross-section of society. It

was not intended that such challenges be used to

encroach upon the constitutional guarantee of an

impartial jury.... [W]e find that adhering to the

Swain test of evaluating peremptory challenges

impedes, rather than furthers, Article I, section

16’s guarantee."

7a

APPENDIX C

17 Stat. 282 (1872)

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of

Representatives o f the United States o f America in Congress

assembled, That section two of the act entitled "An act

regulating proceedings in criminal cases, and for other

purposes," be, and the same is hereby, amended to read as

follows:

"Sec. 2. That when the offence charged be treason or

a capital offence, the defendant shall be entitled to twenty

and the United States to five peremptory challenges. On the

trial of any other felony, the defendant shall be entitled to

ten and the United States to three peremptory challenges; and

in all other cases, civil and criminal, each party shall be

entitled to’ three peremptory challenges; and in all cases

where there are several defendants or several plaintiffs, the

parties on each side shall be deemed a single party for the

purposes of all challenges under this section. All challenges,

8a

whether to the array or panel, or to individual jurors, for

cause or favor, shall be tried by the court without the aid of

triers."

9a

APPENDIX D

Trial Court Opinion in Cornett v. City o f Miami.

Reported in City o f Miami v. Cornett, 463 So. 2d 399, 400-

01 (Fla. App. 3 Dist. 1985).

"This trial commenced shortly after verdicts

had been returned in two other much publicized

cases. In the latter of the two cases, the county’s

school superintendent, a black, was indicted,

suspended from office, then convicted of grand

theft. The Superintendent was tried before an all-

white jury after a number of blacks had been

challenged peremptorily. In the earlier case, an

all-white jury acquitted several white officers of

murder and manslaughter charges in the beating of

a black insurance agent — the infamous ’McDuffie

Case’. All prospective black jurors had been

challenged, some for cause, most peremptorily.

Moments following the verdict in that case there

was a civil disturbance in the community resulting

in millions of dollars of property damage and

several deaths. Those killed included whites and

blacks, and in a few instances the motives were

clearly racial. Judicial notice is taken of these

background circumstances as they shed light on

community tensions in general at the time of this

trial and the probable effect on the conduct of this

trial. Some white prospective jurors admitted that

they couldn’t be fair. At least one admitted to

being fearful and asked to be excused.

* * *

"The misuse of the peremptory challenge to