School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Appendix on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Appendix on Behalf of Appellants, 1956. cb29694f-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2ddf47d7-235d-456a-bb4f-bbf996e031ca/school-board-of-the-city-of-charlottesville-virginia-v-allen-appendix-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

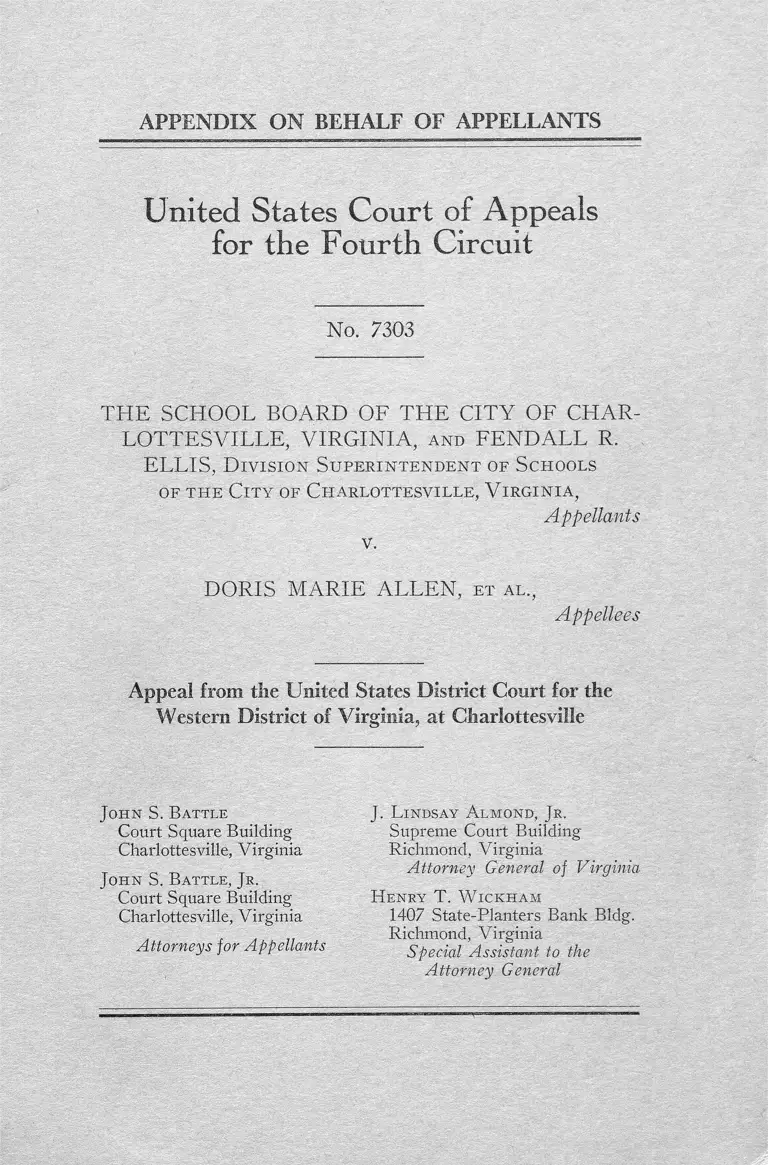

APPENDIX ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

T H E SCH OOL BO ARD OF T H E C ITY OF C H A R

LO TT E SV ILL E , V IR G IN IA , and FE N D A LL R.

ELLIS, D ivision Superintendent of Schools

of the City of Charlottesville, V irginia,

Appellants

v.

DORIS M A R IE ALLE N , et al.,

Appellees

Appeal from tlie United States District Court for the

Western District of Virginia, at Charlottesville

Jo h n S. Battle

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Jo h n S. B attle , Je .

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

J. L indsay A lm ond , Je.

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Attorney General of Virginia

H enry T . W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. Complaint ...................................................................................- 1

II. Answer ........... .............. .................................. ............................ 8

III. Order of District C ourt..... ........................................................ 11

IV. Opinion of District Court ....................................... ................ 13

V. A. Motion to Dismiss Fendall R. E llis ...........................-...... 23

B. Denial of Motion to Dismiss Fendall R. E llis ..............—. 23

C. Motion to Dismiss on Ground That State Has Not Con

sented to Be Sued...... ................... ..................................— 24

D. Denial of Motion to Dismiss on Ground That State Has

Not Consented to Be Sued .............. .............. — ...... -...... 25

VI. A. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit “ A ”— Petition to School B oard ....... 26

B. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit “ B”— Reply to Petition ............... 30

V II. A. Plaintiffs’ Witness George R. Ferguson ............ ...... — 32

B. Plaintiffs’ Adverse Witness Fendall R. Ellis ................ 35

V III. A. Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Evidence in Support of

Complaint ................................................................. 46

B. Denial of Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Evidence----- 47

IX . A. Defendants’ Exhibit No. 2— Deposition of Fendall R.

Ellis ...................................................... 49

B. Defendants’ Exhibit No. 3— Deposition of James H.

Michael, Jr................................................... 53

X . Testimony of Fendall R. Ellis on Cross, Redirect and Re-

cross-Examination ......................... 55

X I. Testimony of James H. Michael, Jr. on Cross-Examination 72

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

T H E SCH OOL BO ARD OF T H E C ITY OF C H A R

LO TTE SV ILLE , V IR G IN IA , and FE N D A LL R.

ELLIS, D ivision Superintendent of Schools

of the City of Charlottesville, V irginia,

Appellants

v.

DORIS M AR IE A LLE N , et al.,

Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Virginia, at Charlottesville

APPENDIX ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

APPENDIX I

CO M PLAIN T

1. (a ) The jurisdiction o f this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, Section 1, and the Act of May 31, 1870,

Chapter 114, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981), as hereinafter more fully ap

pears. The matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of

interest and costs, the sum or value of Three Thousand

($3,000.00) Dollars.

2

(b ) The jurisdiction o f this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343. This action is

authorized by the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, Sec

tion 1, 17 Stat. 13 (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1983), to be commenced by any citizen of the United States

or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the

deprivation, under color o f a state law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom or usage, of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States, Section 1, and by the Act of

May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title

42, United States Code, Section 1981), providing for the

equal rights of citizens and of all persons within the juris

diction of the United States, as herein after more fully

appears.

2. Infant plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens o f the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents o f and domiciled in the City of Charlottesville,

Virginia. They are within the statutory age limits o f eli

gibility to attend the public schools of said City, and possess

all qualifications and satisfy all requirements for admission

thereto, and are in fact attending public schools o f said City

operated by defendants.

3. Adult plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents of and domiciled in the City of Charlottesville,

Virginia. They are parents or guardians o f the infant plain

tiffs, and are taxpayers o f the United States and of said

Commonwealth and City. All adult plaintiffs having control

or charge of any unexempted child who has reached the

seventh birthday and has not passed the sixteenth birthday

are required to send said child to attend school or receive

3

instruction (Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 12,

Article 4, Sections 22-251 to 22-256).

4. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and,

there being common questions of law and fact affecting the

rights of all other Negro children attending the public

schools in the City of Charlottesville, Virginia, and their

respective parents and guardians, similarly situated and

affected with reference to the matters here involved, who

are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring all

before the Court, and a common relief being sought, as will

hereinafter more fully appear, bring this action pursuant to

Rule 23 (a ) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as a

class action, also on behalf o f all other Negro children at

tending the public schools in the City of Charlottesville,

Virginia, and their respective parents and guardians, simi

larly situated and affected wdth reference to the matters here

involved.

5. Defendant The School Board of the City of Char

lottesville, Virginia, exists pursuant to the Constitution and

laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia as an administrative

department of the Commonwealth of Virginia discharging

governmental functions (Constitution of Virginia, Article

IX , Section 133, Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 1,

Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3, Chapter 6, Article 1,

Sections 22-45 to 22-58, Chapter 6, Article 4, Sections 22-89

to 22-99, Chapters 7 to 15, Sections 22-101 to 22-330) ; and

is declared by law to be a body corporate ( Code of Virginia,

1950, Chapter 6, Article 4, Section 22-94).

6. Defendant Fendall R. Ellis is Division Superintend

ent of Schools o f the City o f Charlottesville, Virginia. He

holds office pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the

Commonwealth of Virginia as an administrative officer of

4

the public free school system o f Virginia (Constitution of

Virginia, Article IX , Section 133; Code of Virginia, 1950,

Title 22, Chapter 1, Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3,

Chapter 4, Sections 22-31 to 22-40, Chapters 6 to 15, Sec

tions 22-45 to 22-330). He is under the authority, super

vision and control of, and acts pursuant to, the orders, poli

cies, practices, customs and usages of defendant The School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia. He is made

a defendant herein in his official capacity.

7. The Commonwealth o f Virginia has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution o f Virginia,

Article IX, Section 129, provides:

“ Free schools to be maintained. The General Assem

bly shall establish and maintain an efficient system of

public free schools throughout the State.”

Pursuant to this mandate, the General Assembly of Virginia

has established a system of free public schools in the Com

monwealth of Virginia according to a plan set out in Title

22, Chapters 1 to 15, inclusive, of the Code of Virginia of

1950. The establishment, maintenance and administration

o f the public school system of Virginia is vested in a State

Board of Education, a Superintendent o f Public Instruc

tion, Division Superintendents of Schools, and County, City

and Town School Boards (Constitution of Virginia, Article

IX , Sections 130-133; Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22,

Chapter 1, Section 22-2).

8. The public schools o f the City of Charlottesville, V ir

ginia, are under the control and supervision o f defendants,

acting as an administrative department or division of the

Commonwealth of Virginia (Code of Virginia, 1950, Title

22, Chapter 1, Sections 22-1, 22-2). Defendant The School

5

Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia, is empowered

and required to establish and maintain an efficient system of

public free schools in said City (Code of Virginia, 1950,

Title 22, Chapter 1, Sections 22-1, 22-5); to provide suit

able and proper school buildings, furniture and equipment,

and to maintain, manage and control the same (Code of V ir

ginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 1, Article 1, Section 22-97) :

to determine the studies to be pursued, the methods of teach

ing, and the government to be employed in the schools (Code

of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 6, Article 4, Section

22-97, Chapter 12, Article 2, Sections 22-233 to 22-240.1) ;

to employ teachers ( Code of Virginia, 1950, Chapter 6,

Article 4, Section 22-97, Chapter 11, Section 22-203); to

provide for the transportation of pupils (Code of Virginia,

1950, Title 22, Chapter 13, Articles 1 and 2, Sections 22-

276 to 22-294); to enforce the school laws (Code of V ir

ginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 6, Article 4, Section 22-97);

and to perform the numerous other duties, activities and

functions essential to the establishment, maintenance and

operation of the schools o f said City ( Code of Virginia,

1950, Title 22, Chapter 1, Sections 22-1 to 22-10, Chapters

4 to 5, Sections 22-30 to 22-44, Chapter 6, Article 1, Sec

tions 22-45 to 22-58, Article 4, Sections 22-89 to 22-100,

Chapters 7 to 15, Sections 22-101 to 22-330).

9. Defendants, and each of them, and their agents and

employees, maintain and operate separate public schools for

Negro and white children, respectively, and deny infant

plaintiffs and all other Negro children, because of their race

or color, admission to and education in any public school

operated for white children, and compel infant plaintiffs

and all other Negro children, because of their race or color,

to attend public schools set apart and operated exclusively

for Negro children, pursuant to a policy, practice, custom

6

and usage of segregating, on the basis o f race or color, all

children attending the public schools of said city.

10. The aforesaid action o f defendants denies infant

plaintiffs, and each of them, their liberty without due process

of law and the equal protection o f the laws secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States, Section 1, and the rights secured by Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981.

11. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court o f the United

States declared the principle that state-imposed racial segre

gation in public education is violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. A

formal demand has heretofore been made on behalf of plain

tiffs and all other persons similarly situated that defendants

conform to said decision and desist from the policy, practice,

custom and usage specified in paragraph 9 hereof. Notwith

standing, defendants, and each of them, refuse to act favor

ably upon this demand and purposefully, wilfully and delib

erately continue to enforce and pursue said policy, practice,

custom and usage against infant plaintiffs and all other

Negro children.

12. Defendants will continue to pursue against plaintiffs,

and all other Negro children similarly situated, the policy,

practice, custom and usage specified in paragraph 9 hereof,

and will continue to deny them admission, enrollment or

education to and in any public school operated for children

residing in said City who are not Negroes, unless restrained

and enjoined by this Court from so doing.

13. Plaintiffs, and those similarly situated and affected,

are suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with ir

reparable injury in the future by reason of the policy, prac

tice, custom and usage and the actions of the defendants

7

herein complained of. They have no plain, adequate or com

plete remedy to redress the wrong's and illegal acts herein

complained of other than this complaint for an injunction.

Any other remedy to which plaintiffs and those similarly

situated could be remitted would be attended by such uncer

tainties and delays as would deny substantial relief, would

involve a multiplicity of suits, and would cause further irrep

arable injury and occasion damage, vexation and inconven

ience.

14. As a consequence o f the purposeful, wilful and delib

erate action o f defendants, in continuing, in violation of

their legal duty to plaintiffs, to segregate infant plaintiffs

and other Negro children on the basis o f their race or color,

plaintiffs are required to employ attorneys and undergo great

trouble, inconvenience and expense to litigate a vindication

of their constitutional rights.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that, upon the fil

ing of this complaint, as may appear proper and convenient,

this Court advance this action on the docket and order a

speedy hearing o f this action according to law and, and upon

such hearing:

(a ) This Court enter a preliminary injunction and/or a

permanent injunction restraining and enjoining defendants,

and each of them, their successors in office, and their agents

and employees, forthwith, from enforcing or pursuing

against infant plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly

situated the policy, practice, custom and usage specified in

paragraph 9 hereof, and/or any other policy, practice, cus

tom or usage of the same or similar purport, and/or any

action whether or not pursuant to said policy, practice, cus

tom or usage which precludes, on the basis of race or color,

the admission, enrollment or education of infant plaintiffs

8

or any other Negro child similarly situated to and in any

public school operated by defendants at the same time, and

under the same terms and conditions, and with the same

treatment, that similarly situated children o f any other race,

color or group are admitted, enrolled, educated or given

therein, upon the ground that any such policy, practice, cus

tom, usage, or action denies infant plaintiffs, and other

Negro children similarly situated, their liberty without due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws, secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States, Section 1, and the rights secured by Title 42,

United States Code, Section 1981, and is for these reasons

unconstitutional and void.

(b ) This Court allow plaintiffs their costs herein, and

reasonable attorneys’ fees for their counsel, and grant such

further, other, additional or alternative relief as may appear

to the Court to be equitable and just in the premises.

APPENDIX II

ANSW ER

In answer to the complaint heretofore filed in this action,

defendants say:

1. Defendants deny the jurisdiction of the Court as set

forth in the allegations of Paragraph 1(a) of the complaint.

As to the allegations o f Paragraph 1 (b ) o f the complaint,

the defendants allege that the Court does not have jurisdic

tion in this action because the complaint does not state a case

or controversy upon which relief can be granted.

2. Defendants are not advised as to the truth o f the

allegations o f Paragraph 2 of the complaint and call for

strict proof o f all such allegations.

9

3. Defendants are not advised as to the truth of the alle

gations of Paragraph 3 of the complaint and call for strict

proof of all such allegations, except that defendants admit

the allegation of Paragraph 3 regarding the compulsory

school attendance law of Virginia.

4. Defendants deny the allegations of fact and the con

clusions of law contained in Paragraph 4 of the complaint,

and with respect to the allegations of said Paragraph 4 de

fendants state that if this be a class action as contended by

the plaintiffs, the only persons coming within said class are

Negro citizens of the United States residing in the Common

wealth of Virginia who are otherwise duly qualified for ad

mission to the public schools of Charlottesville, Virginia,

and who have applied for and been denied such admission.

5. Defendants admit the allegations of Paragraph 5 of

the complaint.

6. Defendants admit that Fendall R. Ellis is Division

Superintendent of Schools in the City o f Charlottesville,

Virginia, and that he holds office pursuant to the Constitu

tion and laws o f the Commonwealth of Virginia. Defend

ants deny all other allegations of Paragraph 6 of the com

plaint.

7. Defendants admit the allegations of Paragraph 7 of

the complaint.

8. Defendants admit that the administration of the public

school system of Charlottesville, Virginia, is administered

by them. The defendant Fendall R. Ellis denies that said

public schools are under his control and the defendant. The

School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia, denies

that it is empowered and required to establish and maintain

an efficient system of public free schools in said City. The

10

defendants admit that their powers and duties are prescribed

by Title 22, o f the Code of Virginia but all other allegations

of fact contained in Paragraph 8 of the complaint are denied.

9. Defendants admit they are following state policy and

laws requiring the maintenance of separate schools for white

and Negro children, and assert that such state policy and

laws are valid and not repugnant to the Constitution of the

United States but to the contrary are within the police pow

ers o f the state. Defendants deny all other allegations of

Paragraph 9 of the complaint.

10. Defendants deny all the allegations of Paragraph 10

o f the complaint.

11. Defendants admit that on .May 17, 1954, the Su

preme Court of the United States held in the case of Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, and com

panion cases, that state-imposed racial segregation in public

education violates the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution but allege that such decisions in those cases are not

binding on this Court under the facts as they shall be dis

closed by the evidence in this case. Defendants further

assert that even under the aforesaid cases they are not re

quired to integrate the public schools of Charlottesville, V ir

ginia, and therefore the relief sought in the complaint should

be denied. Defendants deny the remaining allegations of

Paragraph 11 of the complaint.

12. Defendants deny that they are pursuing, or will pur

sue, a policy or practice in denial o f the rights of the plain

tiffs in this case.

13. Defendants deny all o f the allegations o f Paragraph

13 of the complaint.

11

14. Defendants deny all o f the allegations of Paragraph

14 of the complaint.

15. Defendants deny all o f the allegations in the com

plaint which are not specifically admitted in this Answer and

deny that the plaintiffs are entitled to the relief sought in the

complaint.

Defendants move that this action he dismissed upon the

following grounds:

(a ) Defendants allege that this action should be dis

missed on the ground of lack of jurisdiction and

assert that this proceeding involves no case or con

troversy upon which relief should be granted:

( b ) The defendant the School Board of the City of

Charlottesville, Virginia, alleges that this action

should be dismissed as to it on the ground of lack

of jurisdiction over this party since the School

Board of the City of Charlottesville is an agency

of the State of Virginia and the state has not given

its consent to be sued in this action.

(c ) The defendant Fendall R. Ellis alleges that as to

him the complaint should be dismissed for failure

to state a claim against him upon which relief can

be granted.

APPENDIX III

ORDER OF DISTRICT COURT

This action having come on to be heard on July 12, 1956,

upon the complaint, the answer, and evidence offered by

the plaintiffs and the defendants, and the arguments of

counsel.

Upon consideration whereof, the court being of opinion

12

that the plaintiffs are entitled to the relief sought in their

complaint, and having set forth the reasons for its conclu

sions in a written opinion this day filed and made a part of

the record,

It is accordingly Adjudged, Ordered and Decreed

1. That the defendants, and each of them, their succes

sors in office, and their agents and employees, be, and they

hereby are, restrained and enjoined from any and all action

that regulates or affects, on the basis of race or color, the

admission, enrollment or education of the infant plaintiffs,

or any other Negro child similarly situated, to and in any

public school operated by the defendants.

2. That this injunction become effective at the commence

ment of the school term commencing in September, 1956.

3. That the plaintiffs recover from defendants their costs

in this action.

And the plaintiffs having moved the court that the defend

ants be required to pay the attorneys’ fees of counsel for the

plaintiffs in this action.

Now, therefore, upon consideration of said motion, the

same is denied, to which action o f the court counsel for the

plaintiffs except.

It is further Ordered

that this action remain upon the docket of the court and that

the court retain jurisdiction o f the same for such future

action, if any, as may be necessary therein.

The clerk of this court will send an attested copy of this

order to each of the following:

13

Mr. Spottswood W . Robinson, III,

Attorney at Law,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond, Virginia.

Mr. Oliver W . Hill,

Attorney at Law,

118 East Leigh Street,

Richmond, Virginia.

Honorable J. Lindsay Almond, Jr.,

Attorney General of Virginia,

Richmond, Virginia.

Honorable John S. Battle,

Attorney at Law,

Charlottesville, Virginia.

(s) John Paul

District Judge

APPENDIX IV

OPINION OF DISTRICT COURT

This suit is an outgrowth of the decision o f the Supreme

Court o f the United States in a group of cases in which

challenge was made to the laws of those states which require

that, in the operation o f the public school system, separate

schools be maintained for white and for Negro children.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court handed down its

opinion under the style o f Brown, et al. v. Board o f Educa

tion of Topeka, et al. (reported in 347 U. S. 483) in which

it held that state laws which require the segregation of white

and Negro children in the public schools o f the state solely

on the basis of race were in violation of the Constitution of

14

the United States, in that they denied to Negro children the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. Included in the group of cases covered by the

opinion in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was one

arising in Virginia under the style of Davis, et al. v. County

School Board of Prince Edward County.

Following the rendition of the opinion above mentioned

the Court retained the cases on its docket for further con

sideration of the terms of such decrees as would be appro

priate to carrying out the holdings of the Court. After full

consideration, which included the hearing of argument of

all parties concerned, The Supreme Court on May 31, 1955,

handed down its further opinion in these cases. In this opin

ion the Court recognized that the variation in local condi

tions involved differences in the problems arising in apply

ing the principles enunciated by it and that it would be im

practicable to fix a definite date on which segregation in all

schools affected by its decision should cease. It made no

attempt to fix such a date. However it did state that, after

giving due consideration to the local conditions involved,

“ the courts will require that the defendants make a prompt

and reasonable start toward full compliance with our May

17, 1954 ruling.” The defendants in the instant case were

not parties to the litigation above referred to but the prin

ciples settled by that case are, of course, o f universal appli

cation.

In the instant case the plaintiffs are some forty three chil

dren of the Negro race who sue by their parents or guardians

as next friend and with whom these parents or guardians

have joined as plaintiffs in their individual capacities. The

complaint sets out that the suit is brought by the plaintiffs

in their own behalf and on behalf o f all other Negro children

attending the public schools in Charlottesville. The defend

ants are the School Board o f the City of Charlottesville and

15

Fendall R. Ellis, Superintendent of Schools o f that city.

Jurisdiction of this court is invoked under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution, the Act o f Congress of

May 31, 1870 (16 Stat. 144; 42 U. S. C. 1981) and under

Title 2'8 U. S. C. Section 1343. Without going into a dis

cussion of the several constitutional and statutory provisions

under which jurisdiction is alleged and without excluding

the applicability o f any of them, it is sufficient to say that

the provisions o f Title 28. Sect. 1343, plainly support juris

diction in this court. The decision of the Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education o f Topeka, Supra, established

the right o f Negro children not to be discriminated against

on account of their race in admission to the public schools,

and the purpose of this action, as shown by the complaint,

is to redress the deprivation of that right. See 28 U. S. C.

1343 (3 ). The prayer of the complaint in brief substance is

that the defendants and their successors in office be enjoined

from enforcing the practice which has heretofore compelled

that Negro children and white children be educated in sepa

rate schools.

The case came on to be heard on the complaint and the

answer thereto, and on the testimony in open court from

several witnesses offered by each side. But neither the plead

ings nor the testimony of the witnesses present any sub

stantial issues of fact in the case. The answer of defend

ants admits that the policy and the law of the State of

Virginia require the maintenance o f separate schools for

white and Negro children and that they, the defendants, are

following that policy in the operation of the public schools in

Charlottesville. Defendants admit that they have taken no

steps whatever toward the abandonment or modification of

this policy. Such matters of defense as are presented in the

answer involve legal questions. To these the court has given

16

full consideration and has found none of them to offer a bar

to the relief sought by the plaintiffs.

The defendants first assert that the laws of Virginia

which require segregation in the public schools are not re

pugnant to the Constitution of the United States but are

within the police power of the state. This is merely a re

assertion of the contention which the Supreme Court struck

down in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. That the

defendants recognize this is indicated by the fact that they

do not press the subject in argument.

The answer embodies a motion to dismiss the action on

several stated grounds. The first o f these is a brief allega

tion that the court is without jurisdiction and that the pro

ceeding involves no controversy upon which relief should be

granted. This point was not argued and in my opinion, as

previously indicated herein, is without merit.

It is further moved on behalf of the defendant, School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, that the action be dis

missed as to it on the ground that the School Board is an

agency of the State of Virginia and the state has not

given its consent to be sued in this action. The Code of

Virginia, Sect. 22-94, provides :

“ The school trustees of each city shall be a body

corporate under the name and style o f ‘The School

Board of the City of ----- --------- ’ , by which name it

may sue and be sued, contract and be contracted with,

and purchase, take, hold, lease, and convey school prop

erty, both real and personal. * * * ”

Counsel for defendants urge that this statute granting

permission to sue a School Board is intended to apply only

to actions in the courts o f the state. However the statute

itself contains no such limitation. Its terms are compre

17

hensive in that it makes a School Board suable without lim

itation as to the forum in which or the persons by which it

may be sued. Nor does there appear to be any other statu

tory provisions or any decision o f the courts of the state

which impose on Sect. 22-94 the limitations now suggested.

In support o f their position defendants rely upon certain

expressions in the opinion in the case of O ’Neill v. Early,

208 Fed. (2d) 286, which arose in this Circuit and in which

the opinion was written by Parker, Chief judge. This was a

case in which a public school teacher sued a superintendent

of schools and a School Board for damages for breach of

contract for failure to re-employ the plaintiff as a teacher.

In affirming dismissal of the action by the District Court

the Circuit Court did so on the ground that no jurisdiction

existed in the Federal Court, in that the purpose of the action

was to establish liability against the state payable out of

public funds, and was plainly a suit against the state. In the

course of the opinion this language is used, and is apparently

that on which defendants rely:

“ The fact that the state has authorized the defendant

school board to sue and be sued is immaterial, since it

has not consented to suit in the federal court. (Citing

cases) Even if it had consented to be sued in the federal

court, jurisdiction is lacking since no federal question

is involved and there is no diversity o f citizenship in a

suit which, although nominally against state officers, is

in reality a suit against a state.” ( Citing cases )

Examination of the opinion from which the above quota

tion is taken seems to make it clear that because the remedy

sought was a money judgment, which would have had to be

paid from state funds, the Court considered the action to be

one against the state. But the case in all its aspects is so

far different from that before this court as to give it no

18

applicability here. It is certain that the court did not mean

to say that a state school board could not be sued in a federal

court under any circumstances. In fact the same court with

the same judges sitting and in an opinion also written by

Parker, Chief Judge, upheld a suit against a school board

where the plaintiff charged a violation of his constitutional

rights. Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 Fed.

(2d) 992. Also in Corbin v. School Board of Pulaski

County, 177 Fed. (2d) 924, and in Carter v. School Board

of Arlington County, 182 Fed. (2d) 531, this same Circuit

Court entertained suits against local school boards where

violation o f constitutional rights were charged.

It is true that it does not appear that there was raised in

any of these cases the point now urged upon this court,

namely, that the suit is one against the state and that there

fore the court is without jurisdiction. Neither does it appear

that this defense was offered in any of the four cases de

cided by the Supreme Court under the reported title of

Brown v. Board of Education, supra, including the case of

Davis v. School Board of Prince Edward County. Consid

ering the strenuous nature o f the defenses offered in these

cases it seems strange that this defense, which if valid would

have been a complete defense, was overlooked. However

this may be it seems clear that the contention made is with

out merit. It has long been settled that suits against state

officers to restrain the enforcement of state laws which con

travene the Federal Constitution are not suits against the

state. See Dobie on Federal Procedure, Sect. 133, where in

treatment of this subject it is said:

“ Such suits are treated as suits against the officers,

not against the state; so they do not come within the

prohibition o f the Eleventh Amendment. This princi

ple, applied by the Supreme Court in a long series of

19

decisions, is now well established.” ( Citing numerous

cases)

And, of course, where the subject matter of a suit is the

protection of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States the federal courts have jurisdiction. In

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378, suit was brought

against several officials o f the State of Texas including the

governor of the state. The Supreme Court held that even

the governor of a state was subject to the process of the

federal courts for the relief of private persons when by his

acts under color o f state authority he invades rights secured

to them by the Federal Constitution, and that the suit was

not one against the state ; the Court, speaking through Chief

Justice Hughes, saying (p. 393) :

“ The District Court had jurisdiction. The suit is not

against the state. The applicable principle is that where

state officials, purporting to act under state authority,

invade rights secured by the Federal constitution, they

are subject to the process of the federal courts in order

that the persons injured may have appropriate relief.”

citing Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123, 155, 156, and

other cases.

In Looney v. Crane Co., 245 U. S. 178, which was a suit

against the Secretary of State and the Attorney General of

the State of Texas to enjoin the enforcement of a taxing

statute alleged to be in violation of the Constitution of the

United States, the Supreme Court closes its opinion (by

Chief Justice White) with this paragraph (p. 191).

“ There is a contention to which we have hitherto

postponed referring, that the court below was without

jurisdiction because the suit against the state officers to

enjoin them from enforcing the statutes in the dis

20

charge of duties resting upon them was in substance

and effect a suit against the State within the meaning

of the Eleventh Amendment. But the unsoundness of

the contention has been so completely established that

we need only refer to the leading authorities. Ex parte

Young, 209 U. S. 123; Western Union Telegraph Co.

v. Andrews, 216 U. S. 165; Home Telephone & Tele

graph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278”

The answer also includes a motion to dismiss the action

as to Fendall R. Ellis, Superintendent o f Schools of the City

of Charlottesville, who is a named defendant. This motion

also must be denied. The court takes notice of the fact that

the Division Superintendent of Schools, whether in a city

or county, exercises a greater influence over the operation

o f the schools than anyone else, including the School Board.

The powers and duties o f the Division Superintendent,

which are fixed by the State Board of Education, are broad

and extend to almost every detail in the management of the

schools. To dismiss this official as a defendant might well

nullify, or certainly lessen, the effectiveness of any decree

that is entered here by making it non-applicable to the per

son having a large share in the responsibility for carrying it

out.

Finally the defendants have moved that the action be dis

missed on the ground that plaintiffs have not made a case

appropriate to the relief sought, in that no evidence has been

introduced showing that the school authorities o f Charlottes

ville have ever denied the application of any Negro child for

admission to any school in the city or that such an applica

tion has been made by any Negro. This motion rests on the

tenuous support of the failure of any individual Negro child

to file a formal application for admission to a school hereto

21

fore reserved for white children. Under the pleadings and

the evidence in the case it is plain that the motion to dismiss

on this ground is without merit and must be denied.

The evidence shows that in October, 1955, the plaintiffs

in this case, through their attorneys, addressed a communi

cation to the School Board of Charlottesville and to Mr.

Ellis, the Superintendent of Schools, in which they referred

to the ruling of the Supreme Court in its opinions of May 17,

1954, and May 31, 1955, and then said:

"'‘W e therefore call upon you to take immediate steps

to reorganize the public schools under your jurisdiction

so that children may attend them without regard to

their race or color. * * * As we interpret the (Supreme

Court) decision, you are duty bound to take immediate

concrete steps leading to early elimination of segrega

tion in the public schools. * * * W e further request that

you will give us an early reply setting forth your initial

plans for desegregation.”

Several weeks later the School Board made its reply in

a communication which, while giving no direct answer to

plaintiff’s requests, made it clear that it intended to pursue

the policy of segregation for the school session of 1955-56;

and as to the future it gave no assurance whatever. In fact

the School Board’s reply, while plainly evasive, nevertheless

gave the distinct impression that it was making no plans to

discard the policy of segregation at any time. This is con

firmed by the admissions made at the hearing o f the case

that no steps whatever have been taken to this time to com

ply with the ruling of the Supreme Court. The prayer of the

complaint is in substance that the defendants be enjoined

from continuing to maintain segregated schools. The de

22

fendants have refused to agree to abandon the practice of

segregation and have made it plain that they intend, if pos

sible, to continue it. Under this state of facts the plaintiffs

are undoubtedly entitled to maintain this action and to have

the relief prayed for.

It only remains to be determined as to the time when an

injunction restraining defendants from maintaining segre

gated schools shall become effective. The original decision

o f the Supreme Court was over two years ago. Its supple

mentary opinion directing that a prompt and reasonable

start be made toward desegregation was handed down four

teen months ago. Defendants admit that they have taken no

steps toward compliance with the ruling of the Supreme

Court. They have not requested that the effective date of

any action taken by this court be deferred to some future

time or some future school year. They have not asked for

any extension o f time within which to embark on a program

o f desegregation. On the contrary the defense has been one

of seeking to avoid any integration of the schools in either

the near or distant future. They have given no evidence of

any willingness to comply with the ruling o f the Supreme

Court at any time. In view of all these circumstances it is

not seen where any good can be accomplished by deferring

the effective date of the court’s decree beyond the beginning

of the school session opening this Autumn. Even though

the time be limited it is not impossible that, at the school ses

sion opening in September of this-year, a reasonable start be

made toward complying with the decision of the Supreme

Court.

D istrict Judge

August 6, 1956

23

APPENDIX V

A.

M OTION TO DISMISS FENDALL R. ELLIS

(Tr. pp. 6-7)

Mr. A lmond : Thank you, Sir.

On behalf o f this defendant, the Division Superintendent,

we move, as to him, that the complaint be dismissed for

failure to state a claim against him upon which appropriate

relief could be granted; also that he is not a proper party

to this proceedings, and if the Court should hold that he is

a proper party, certainly he is not a necessary party, which

latter phase o f the argument, as I understand it, would ad

dress itself to the sound discretion of the Court.

B.

DENIAL OF M OTION TO DISMISS

FENDALL R. ELLIS

(Tr. pp. 14-15)

T he Court: Mr. Attorney General, I think your motion

will have to be denied.

I don’t know too much about the operation of the school

system but I know the school board is made up of citizens

selected for their public spirit, who meet occasionally and

go over the school budget and make recommendations to the

City Council and lay out certain policies.

But at the head of any school in any city is the County

Superintendent o f Schools. I f he has nothing to do with

admission of pupils in one school or the other, then he cannot

run any danger whatever o f any violation o f any decree that

this Court should enter, if it should enter one.

But the purpose o f this Act is to reach the persons who

might be influential in having determination over what

24

children shall enter what schools and to restrain them from

the exercise of discrimination on account of race; and

I do know enough about the school system to know that the

Division Superintendent, County and City Superintendents,

are the most influential persons in the conduct of the schools

either in any county, or city, and that the intimate knowledge

of the schools, of what is going on in the schools, is not

ordinarily possessed by the average school board; and I

think the injunction, if one should be granted, should reach

every person who might have any influence or power in the

determination of the assignment, or refusal, of children to

particular schools.

As I said a minute ago : if the City Superintendent does

not have such influence, does not take any such part, does

not attempt to do so, then he runs no risk of having violated

any injunction. That would be a question of fact.

I don’t know exactly how they run the city schools in

Charlottesville or to what extent the City Superintendent

is influential, but judging from my own observation, par

ticularly in my own locality, the City Superintendent is the

real power behind the schools.

So he won’t be hurt, if he is retained as a party, if he

does not violate any injunction which might be granted.

I think I might keep him in.

C.

M OTION TO DISMISS ON GROUND THAT STATE

HAS NOT CONSENTED TO BE SUED

(Tr. p. 16)

Mr. Battle : Your Honor please: This petition was filed

by certain persons against “ The School Board of The City

of Charlottesville, Virginia; and Fendall R. Ellis, Division

25

Superintendent of Schools o f the City o f Charlottesville,

Virginia.”

The petition alleges that the School Board is an admin

istrative arm of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the

operation of the schools.

Substantially the same allegation is made with reference

to the Superintendent of Schools; and I understand that

process was served upon the Superintendent and upon the

Chairman of the School Board.

W e wish to move the Court to dismiss this action as being,

in effect, a suit by individuals against the Commonwealth of

Virginia, in contravention of the Eleventh Amendment to

the Constitution.

D.

DENIAL OF M O T IO N TO DISMISS ON GROUND

TH A T STATE HAS N O T CONSENTED TO BE SUED

(Tr. pp. 36-37)

T he Court: I have read this Answer and I saw that

defense drawn up. I was surprised, certainly, that that

question, if it had any validity it would not have been raised

in the Supreme Court; and assuming that it had, it is evi

dent the decision of the Supreme Court held it to be of no

merit.

In addition to that, I recalled— and which I looked up,

again— the statute which makes the school board a corpo

rate entity, with the right to sue and be sued; and I also

recall that, within the past year, several lawyers, Members

of the Legislature, had advocated repeal of the Statute per

mitting the school board to be sued, as one of the methods

of evading compliance with the Supreme Court decision.

So I began to look into the question, myself, and I came

to the ‘tentative’— of course— conclusion that there was no

26

validity to that defense. O f course, I came to that ‘tentative,’

as I say, conclusion, without hearing argument. But I have

heard the arguments of you Gentlemen this morning and I

am, still, of that opinion that I reached previously: that the

defense is without merit.

This is not a suit against the State.

The policy of the State has been fixed by the decision of

the Supreme Court, policy of segregation decision o f the

Supreme Court.

This is merely a suit against a group of the local School

Board to prevent them from discriminating against these

plaintiffs in the exercise of certain rights which the Supreme

Court decision granted to them; similarly, the suits on what

is called the “ Civil Rights Act,” and I have never heard they

have been considered to be suits against the State, where

local officers have been sued for violation o f the civil rights

of the defendants, to be a suit against the State.

This is a suit very similar, of a very similar nature, if not

o f an exact nature.

The motion to dismiss on that ground will be denied.

APPENDIX VI

A.

PLAINTIFFS’ EXHIBIT “A”

(Tr. pp. 39-42)

PE TITIO N

T O : The School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

Virginia, and Mr. Fendall R. Ellis, Division

Superintendent of Schools:

W e represent the following named children, their parents

or guardians. These children are o f school age and attend,

27

or are eligible to attend, public elementary or secondary

schools under your jurisdiction:

Doris Marie Allen and Shirley Elizabeth Allen, infants, by

Mason C. Allen and Mary Allen, their father and mother,

respectively, and next friend,

Linda E. Arnett, an infant, by Bennie M. Arnett, her mother

and next friend,

Cynthia Cooper, an infant, by Granville Cooper and Bertha

Cooper, her father and mother, respectively, and next friend,

Carolyn M. Dobson, an infant, by Sarah B. Brooks, her

guardian and next friend,

Robert L. Drakeford, an infant, by Robert C. Drakeford,

his father and next friend,

Olivia L. Ferguson, an infant, by George R. Ferguson, her

father and next friend,

Charles D. Fowler, III, an infant, by Charles D. Fowler, Jr.,

his father and next friend,

Marshall H. Garrett, Paul C. Garrett and Russell K. Gar

rett, infants, by Marshall T. Garrett, their father and next

friend,

Gloria Hamilton and Melvina Hamilton, infants, by Ger

trude Hamilton, their mother and next friend,

Jacqueline Harris and June Harris, infants, by Alois Har

ris, their mother and next friend,

Jasper Jones, Jr., an infant, by Ruth P. Jones, his mother

and next friend,

William Ware Jones, an infant, by Lucille W . Jones, his

mother and next friend,

28

Alfred Martin, John J. Martin, Donald Martin and Kenneth

Martin, infants, by Julia Martin, their mother and next

friend,

Nathaniel T. Maupin, an infant, by Moses C. Maupin, his

father and next friend,

Reginald Moss, Jr., Jacqueline Moss and Patricia Moss, in

fants, by Reginald R. Moss and Hazel Moss, father and

mother, respectively, and next friend,

Katheryne Robinson, Roberta Robinson and Rodney Robin

son, infants, by Rodney L. Robinson, their father and next

friend,

Alfred Saunders and Judy Saunders, infants, by Alfred

Saunders and Mary Saunders, their father and mother, re

spectively, and next friend,

Joyce A. Smith, Carolyn E. Smith, infants, by William M.

Smith, their father and next friend,

Rudolph Taylor, Louise L. Taylor, Dorothea A. Taylor,

Morris E. Taylor and Lamilla Taylor, infants, by Louise

Taylor, their mother and next friend,

Marvin L. Townsend, an infant, by Thelma Townsend, his

mother and next friend,

Roberta Whitlock, an infant, by Robert C. Whitlock, her

father and next friend,

Sherman R. White, an infant, by Randolph L. White, his

father and next friend,

Robert S. Wicks, Jr., an infant, by Robert S. Wicks, Sr.,

his father and next friend,

Roland T. W oodfolk and Ronald E. Woodfolk, infants, by

Mary A. W oodfolk, their mother and next friend,

29

Roland H. Young, an infant, by Howard Barnes, his guard

ian and next friend.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court o f the United

States ruled that racial segregation in public school is a vio

lation of the Constitution of the United States, The Su

preme Court reaffirmed that principle on May 31, 1955, and

directed “ good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date.” You have the responsibility o f reorganizing the

school system under your jurisdiction so that children of

school age attending and entitled to attend public schools will

not be denied admission to any school or be assigned to a

particular school solely because of race or color.

W e, therefore, call upon you to take immediate steps to

reorganize the public schools under your jurisdiction so that

children may attend them without regard to their race or

color.

The May 31st decision of the Supreme Court, to us, means

that the time for delay, evasion or procrastination is past.

Whatever the difficulties in according our clients their con

stitutional rights, it is clear that the school board must meet

and seek a solution to that question in accordance with the

law of the land. As we interpret the decision, you are duty

bound to take immediate concrete steps leading to early

elimination of segregation in the public schools.

Please rest assured o f our willingness to serve in any way

we can to aid you in dealing with this question. W e further

request that you will give us an early reply setting forth your

initial plans for desegregation.

Respectfully submitted,

(s ) Oliver W . Hill

Oliver W . Hill, o f Counsel

30

B.

PLAINTIFFS’ EXHIBIT “B”

(Tr. pp. 43-45)

C H A R LO TT E SV ILL E PU BLIC SCHOOLS

406 Fourteenth Street

Charlottesville, V irginia

October 17, 1955

Mr. Oliver Hill

Hill, Martin and Robinson

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Dear Mr. H ill:

I am enclosing a Resolution adopted by the School Board

of the City of Charlottesville at its regular meeting on Oc

tober 8 in reply to a Petition received from you on October 6,

1955.

Very truly yours,

(s ) Fendall R. Ellis

Fendall R. Ellis,

Superintendent.

FR E/ds

Enclosure.

Whereas, the School Board of the City of Charlottesville

has received a Petition from Hill, Martin and Robinson,

counsel for “ certain children, their parents and guardians”

listed in said Petition “ requesting an early reply.”

Now, therefore, be it resolved, That the Board submit the

following reply:

31

The School Board believes that it was not the intent of

the Supreme Court’s decision of May 17, 1954, and subse

quent decrees o f May 31, 1955, to disrupt a system of public

education. Therefore, the problem confronting the Board is

to find a solution which will conform to the Supreme Court’s

interpretation of the law and be acceptable to parents and

taxpayers who use and support the public schools. Such a

solution can be found only after sober reflection over a

period o f time.

The position of the School Board with reference to this

problem is stated in the following Resolution adopted by the

Board on July 8, 1955 :

“ Whereas, It is the policy o f the State Board o f Educa

tion that the public schools o f the Commonwealth open and

operate throughout the coming school session as heretofore,

“ Be it further resolved, That this Board constitute itself

a committee of the whole to begin promptly a study o f the

future operation of the City’s public school system in the

light of the Supreme Court decrees o f May 31, 1955 and

such other decisions and decrees as may affect future opera

tions of the public schools.”

And he it further resolved, That the Petition aforesaid

be, and it hereby is, referred to the Committee of the Whole

for consideration and study, with such recommendations as

the Committee may have to be made as a part o f its Report

to this Board.

October 13,1955.

32

APPENDIX VII

A.

PLAINTIFFS’ WITNESS GEORGE R. FERGUSON

(Tr. pp. 47-51)

George R. Ferguson, called as a witness on behalf o f the

plaintiffs herein, being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAM INATION

By M r. H il l :

Q Will you state your name, address and occupation,

please?

A George R. Ferguson, 908 Page Street. Mortician.

Q Mr. Ferguson, what country are you a citizen of ?

A The United States of America.

Q O f what racial identity ?

A Negro.

Q Do you have a child ?

A One child.

Q What is the age of the child ?

A 14.

Q Does the child attend the public schools o f Charlottes

ville ?

A Yes.

Q Or did she attend the public schools o f Charlottesville

for the school session, 1955-1956?

A She did.

Q State the name of your child, please?

A Olivia Louise Ferguson.

33

Q And you and she were one o f the petitioners to the

School Board ?

A Yes.

Q And one o f the complainants in this case ?

A Yes.

Q Will you state what school your child attended during

the school session, 1955-1956?

A Burley High School.

Q And in the years prior to that, what school or schools

did your child attend ?

A Jefferson Elementary School.

Q Was last year the first year she attended high school?

A Second year.

Q Prior to going to Burley, she attended the Jefferson

High School? I mean, Jefferson Elementary School.

A First seven grades.

Q And both of those schools are located in the City of

Charlottesville and come under the jurisdiction of The

School Board o f the City o f Charlottesville ?

A Jefferson under the jurisdiction of the Charlottesville

Board; Burley, joint Board, Albemarle County and City of

Charlottesville.

Q Was there, during the school year o f 1955-1956, and

school year o f 1954-1955, any other high school to which

your child would have been permitted to attend ?

A No.

Q Will you state your address, Mr. Ferguson?

A I gave my business address. My residence address is

702 Redd Street.

34

Q Where is that?

A In the southwest section of the City.

Q O f Charlottesville?

A That is right.

Q Now, the Burley High School, where your child

attended last year, what is the racial designation o f pupils

who attend there, or do you know the racial designation of

pupils who attend there ?

A Negro.

Q Do any white children attend that school ?

A Not that I know of.

Q And the Jefferson High School, what is the racial

designation o f the children who attend that school? The

Jefferson Elementary School?

A Negro.

Q Now, are you familiar with some of the other plain

tiffs in this suit ?

A Yes, I am.

Mr. H il l : I guess the simplest thing would be just to

call their names and ask you whether or not you know them.

Q Do you know Mason Allen and Mary Allen ?

A Yes, Ido.

Q Do you know their children ?

A Yes.

Q Will you state their racial designation ?

A Negroes.

Mr. A lmond: W e will admit all of them are Negroes,

referring to the complaint.

35

Mr. H il l : Defendants admit that the complainants are

all Negroes.

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) I will ask you, Mr. Fer

guson, if you have seen these names ?

A Yes, I have.

Q And all o f these people are residents of the City o f

Charlottesville ?

A Yes.

M r. A lmond : W e will admit that, too.

Mr. H il l : The only other question: whether or not the

defense admits these parents have children eligible to attend

school ?

Mr. Battle : I think you had better go ahead and prove

your case.

Mr. H il l : Will you admit these children are eligible to

attend the public schools o f Charlottesville ?

Mr. Battle : As far as we know. W e don’t controvert

that.

Mr. H ill : All right.

Mr. H il l : That is all. You may cross-examine.

Mr. A lmond: No questions, Your Honor.

B.

PLAINTIFFS’ ADVERSE WITNESS

FENDALL R. ELLIS

(Tr. pp. 52-66)

Fendall R. Ellis, called as an adverse witness, under Rule

40, being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

36

CROSS-EXAMINATION

By Mr. H il l :

Q W ill you state your name, address and occupation?

A My name is Fendall R. Ellis. I live at 1505 Rutland

Avenue, Charlottesville, Virginia. My occupation is Super

intendent o f Schools of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia.

Q And you are one of the defendants in this suit ?

A I am.

Q Now directing your attention, Mr. Ellis, to early in

October 1955, I will ask you whether or not you and the

School Board did not receive this Petition? (Handing docu

ment to the witness)

A W e received it.

Mr. H il l : May it please the Court, Governor Battle

wants this —

T he Court: (Interrupting) Did you identify the Peti

tion?

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Did you receive this

Petition from the named citizens of the City of Charlottes

ville, who are also complainants in this present action, is that

correct ?

A Yes.

T he Court : What is the substance of it ?

Q This was a Petition, was it not, Sir— I will ask you

to read the prayer of the Petition to the Court.

A After the listing o f certain names, the prayer of the

Petition seems to be :

“ We, therefore, call upon you to take immediate steps to

reorganize the public schools under your jurisdiction so that

37

children may attend them without regard to their race or

color.”

T he Court : Let me see that.

Mr. H il l : W e would like to have this marked “ Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit ‘A ’ ” and then move its admission.

Reporter’s Note : Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A was filed, (Page

38) and fully set forth (Page 39) herein.

Mr. H il l : (Repeating) Now, may it please the Court,

I move the admission of this document, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit

A, in evidence in this case.

T he Court: All right.

Mr. H ill : Simultaneously, I would like to ask to with

draw this and substitute a copy.

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Mr. Ellis, how long have

you been Division Superintendent of the Charlottesville

Public Schools, o f Charlottesville, Virginia?

A In the City o f Charlottesville ?

Q Yes, Charlottesville?

A Since July 1st, 1953.

Q And where else have you been ?

A Wythe County, Virginia, July 1, 1945 to June 31,

1953.

Q Since you have been Superintendent of Schools in

Charlottesville, what has been the practice of the adminis

tration and school board in the City of Charlottesville so far

as placing students, with respect to their racial identity ?

A At the present time, we have six elementary schools,

five of which are attended by white children and one of

which is attended by negro children: we have a high school,

38

which is attended by white children, and a high school,

jointly owned and operated by the City o f Charlottesville

and County o f Albemarle, which is attended by negro chil

dren.

Q At any time since you have been Superintendent, from

1953 up to the end of the last school year here in June of

1956, would a negro child, upon application, have been ad

mitted to any school in the City of Charlottesville, otherwise

qualified to attend a school in the City of Charlottesville ?

M r. Battle: W e object.

T he Court : I don’t think he has completed the question,

yet.

Mr. Battle : I beg your pardon.

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Restating the question,

I will ask you, again, if at any time since you have been

Superintendent of Schools, in the City of Charlottesville, if

a negro child of parents residing here in the City of Char

lottesville, within the age limits, who applied for admission

to a school, would that child have been admitted to any school

in the City of Charlottesville, regardless whether elementary

or high school ?

Mr. A lmond: We object.

T he Court: What is your objection, Mr. Almond?

Mr. A lmond: During the time o f Counsel’s question,

the policy now contended against, was conducted under sanc

tion of law, well settled, even by the Supreme Court o f the

United States. That is one ground of our objection, as to

the propriety and relevance of the question. The other is, it is

not what “ has been done,” in the past: the question is, as

to the policy that would be invoked or used for a session of

39

school, that is not in session but that will be in session, in

all probability, in September.

T he Court: Mr. Attorney General, the answer to the

question is perfectly obvious, and a harmless one. W e all

know negroes have been compelled to attend negro schools in

Virginia, in pursuance to statutory law of the State, which

was the statutory law of the State until nullified by the

Supreme Court decision.

W e also, all know that local school authorities have not

felt free to follow the Supreme Court decision, themselves,

without some direction from State authorities, or something

of that sort; and that the policy of segregation still exists

generally over the State.

Don’t we all know that ?

In fact, the very purpose of this suit is to bring about a

change in that situation, isn’t it ?

Mr. Battle: If Your Honor please, but this witness—

if I may express my thought?— this witness is being asked

to answer “ What would have been the situation had a cer

tain thing occurred ?” and this witness—

T he Court: (Interrupting) During what period of

time?

Mr. Battle : During the period of time indicated in the

past.

Mr. H ill : From 1953 up to last June.

Mr. Battle: W e submit that the witness is not compe

tent to answer that question. He has no discretion over the

question of admission of pupils.

T he Court : Oh, that is your objection ? You are not ad

mitting he has anything to do with the admission o f school

children?

40

M r. Battle: Yes.

Mr. H ill : I asked, by whose order it was done. I asked,

what was the fact ?

Mr. Battle: Y ou asked “ what would have happened, if

a certain thing happened ?”

T he Court: He may answer. If he doesn’t know what

happened, he can say he doesn’t know.

Q (B y Mr. Hill, continuing) Answer the question,

please.

A What is the question ?

Mr. H ill : Read the question, please.

T he Reporter reads the question.

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Now the letter merely is

a covering letter, sending the resolutions, was it not, Sir ?

A Yes.

Q Will you read, for the benefit o f the Court, the reso

lution? and that resolution, Sir, was in response to this

Petition referred to as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A, is that correct?

A Yes.

(Reading) “ Whereas, The School Board o f the City of

Charlottesville has received a Petition from Hill, Martin and

Robinson, counsel for ‘certain children, their parents and

guardians’ listed in said Petition ‘requesting an early reply.’

“Now, therefore, he it resolved, That the Board submit

the following reply:

“ The School Board believes that it was not the intent of

the Supreme Court’s decision of May 17, 1954 and subse

quent decrees of May 31, 1955 to disrupt a system o f public

education. Therefore, the problem confronting the Board

is to find a solution which will conform to the Supreme

41

Court’s interpretation of the law and be acceptable to par

ents and taxpayers who use and support the public schools.

Such a solution can be found only after sober reflection over

a period of time.

“ The position of the School Board with reference to this

problem is stated in the following Resolution adopted by the

Board on July 8,1955 ;

“ Whereas, It is the policy of the State Board of Education

that the public schools o f the Commonwealth open and op

erate throughout the coming school session as heretofore,

“Be it resolved, That the School Board of the City of

Charlottesville operate the public schools of the City for

the school year 1955-56 on the same basis as heretofore, and

“ Be it further resolved, That this Board constitute itself

a committee o f the whole to begin promptly a study of the

future operation of the City’s public school system in the

light of the Supreme Court decrees of May 31, 1955 and

such other decisions and decrees as may affect future opera

tions of the public schools.”

“And he it further resolved, That the Petition aforesaid

be, and it hereby is, referred to the Committee of the Whole

for consideration and study, with such recommendations as

the Committee may have to be made as a part of its Report

to this Board.

“ October 13, 1955.”

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Now pursuant to law,

under your supervision, a budget is submitted to the City

Council for the operation o f the public schools in the school

year, 1956-1957, and which is submitted in about March, is

that not right, Sir?

A It is required, by law, to be submitted before April

1st; ordinarily, it is submitted well before that.

42

Q And in pursuance o f your duties and functions, you

and the School Board made your proper plans for the en

suing year, and prepared your budget, did you not ?

A A budget was prepared, with the advice and counsel

of the School Board, as required by law: was submitted to

the City Council, for 1956-1957, and has been approved.

Q And necessarily, you formulated your plans for the

conduct of the schools for the session, 1956-1957, did you

not?

A What do you mean by that ?

Q Well, I mean that, by the time you submitted your

budget, you pretty well knew what you proposed to do, as

far as operation of the schools for 1956-1957, did you not?

I mean, you project your plans into the future and you base

your budget and everything under the proposed operation

of your schools for the coming year, is that correct ?

A That is true: the budget is based on the number of

teachers you expect to have and other considerations.

Q And the general plan of operation for the coming

year, and that is one reason for having a “ budget,” so you

could plan ?

A I think so.

Q And you did do that, did you not ?

A Yes.

Q Well, on or about April 6, 1955, you received a letter

from me, did you not ?

A Yes.

Q Asking you, generally — referring to this previous

communication with you— and asking you what you pro

43

posed to do concerning the school year, 1956-1957, with

respect to desegregation of schools, is that correct ?

A Yes.

Mr. H il l : If the Court please, Counsel had planned to

produce the copy but was unable to find it, so we will just

handle it in this manner:

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) I will show you a letter

dated April 13th, written on the stationery of the School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, and signed by you, and

ask you : Is that not the reply that you sent in response to

my inquiry of April 6th, 1956?

A Yes.

Q And this is the response, that was signed by you ?

A Yes.

Q And it was the response made by the School Board ?

A This gives the action of the School Board, in compli

ance with your request.

Mr. H il l : Now I ask that this be marked Plaintiffs’

Exhibit C, and I will offer it in evidence.

Plaintiff’s Exhibit C, last above referred to, filed.

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Now Mr. Ellis, I will ask

you to read Plaintiffs’ Exhibit C, which has been offered in

evidence, to the Court, please.

A (Reading)

“ School Board of the City of Charlottesville

“ Office o f the Superintendent

“ Charlottesville, Virginia

“ 406 Fourteenth Street

“ April 13, 1956

44

“ Mr. Oliver W . Hill

Hill, Martin and Olphin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

“ Dear Mr. H ill:

“ In reply to your letter o f April 6, I wish to advise that

the School Board at a meeting on April 12 passed the follow

ing Resolution:

“ On motion duly made and carried, the Board instructed

the Superintendent to notify Mr. Hill that no action had been

taken in this matter beyond that about which he had been

previously notified.

“ Very truly yours,

“ (s) Fendall R. Ellis

Fendall R. Ellis,

Superintendent”

FR E/ds

Q (By Mr. Hill, continuing) Now the sum and sub

stance of that is : the situation is just as it was in October,

when we first petitioned, is that correct ?

A (N o reply)

Mr. Battle : He didn’t say.

Mr. H ill : But I asked him about it.

A “ The situation” is a very broad term. I don’t know

just what you mean by it?

Q All right, Sir. I will ask you this: does the School

Board of the City of Charlottesville plan, at this time, to

desegregate the City School for the school term 1956-1957?

A No.

45

Q Or any other period foreseeable, in the foreseeable

future that you know o f ?

A No plan has been approved, as indicated in that letter

■— resolution.

M r. H ill : That is all, Sir.

T h e Court : Just a minute, Mr. Ellis.

E X A M IN A T IO N B Y T H E CO U R T:

Q Mr. Ellis, —-

T he Court: (Interrupting) First, do you Gentlemen

have any examination?

Mr. A lmond : W e may put him on, in chief, Your Honor.

T he Court : All right.

Q (By The Court, continuing) What is the school pop

ulation of the City of Charlottesville ?

A The school population at the last session, 4350 chil

dren.

Q Which includes white and negro children ?

A Both white and negro children.

Q In what proportions ?

A In elementary, approximately 2450 white and 750

negro.

Q And you said the total was, how much ?

A About 4350.

Mr. Battle : I have the exact figures. Maybe Mr. Ellis

— if he can refer to them ?

46

T he Court: Yes. I will be glad to have him do so.

Mr. Battle : ( Hands document to the witness )

A (Referring to document) 2436 white children.

Q (By the Court, continuing) In the grade schools?

A Elementary grades, first seven grades; and 761 negro,

enrolled in elementary school: 897 white, 281 negro children

in the high schools. (Returning document to Mr. Battle)

Q That was for the last session ?

A Yes, sir.

T he Court : That is all I wanted to ask the witness.

(Witness excused)

Mr. H ill : Plaintiffs rest. Your Honor.

APPENDIX VIII

A.

M OTION TO DISMISS FOR LACK OF EVIDENCE

IN SUPPORT OF COMPLAINT

(Tr. p. 66)

Mr. A lmond : At this stage o f the proceedings, Plain

tiffs having rested, put on their case in chief, we ask the

Court to entertain a motion to dismiss the complaint as on

the evidence introduced in support thereof, they have not

made a case, under the law and the evidence, appropriate to

the relief sought: * * *

47

B.

DENIAL OF M OTION TO DISMISS

FOR LACK OF EVIDENCE

(Tr. pp. 73-76)

Mr. H ill : May it please the Court —

T he Court: (Interrupting) Nevermind.

Mr. Attorney General, I don’t think it is a matter of

material importance as to whether or not each child has

made application to a school.

This group has made, filed with the School Board, what

they call a “ Petition,” asking them to adopt the policy of

desegregating the schools under the Supreme Court decision.

If they had, the School Board had replied in the affirmative

to that request, then there would have been the question o f

admission of the children to particular schools, no child to

certain schools they had not, heretofore, been allowed to

enter and the question of individual applications might arise.

But the Board refused to state that they would adopt a

policy of desegregation. If I heard correctly their answer