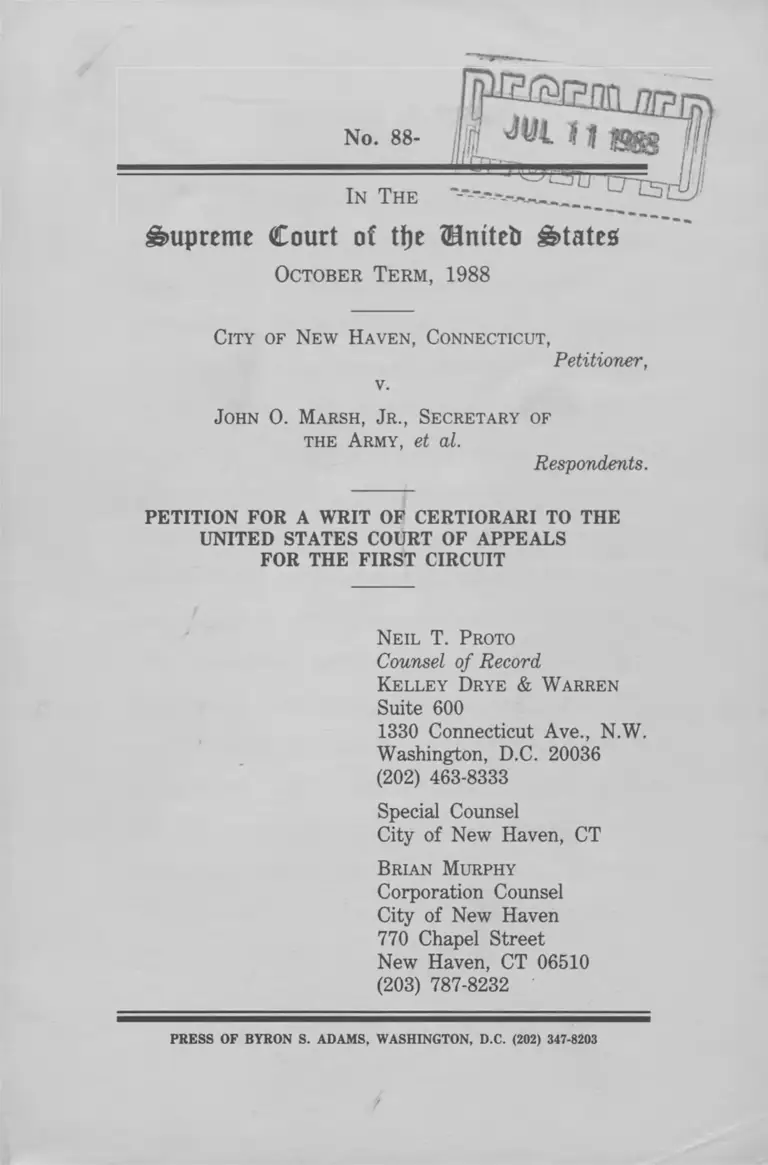

City of New Haven, CN v. Marsh Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 5, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Haven, CN v. Marsh Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, 1988. 4ccdb45e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2e0574ee-28e4-46d4-b7ce-730cd257bae3/city-of-new-haven-cn-v-marsh-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-first-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of tfte Umteti States

October Term, 1988

City of New Haven, Connecticut,

Petitioner,

v.

John 0 . Marsh, Jr., Secretary of

the Army, et al.

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

Neil T. Proto

Counsel of Record

Kelley Drye & Warren

Suite 600

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 463-8333

Special Counsel

City of New Haven, CT

Brian Murphy

Corporation Counsel

City of New Haven

770 Chapel Street

New Haven, CT 06510

(203) 787-8232

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

This suit for declaratory and

injunctive relief was brought by respon

dent, Mall Properties, Inc., against re

spondents, Secretary of the Army and of

ficials of the United States Army Corps

of Engineers, to challenge the denial of

a permit to fill waters of the United

States, in order to construct a regional

shopping mall, under section 404 of the

Clean Water Act, section 10 of the Rivers

and Harbors Act and section 102(2)(C) of

the National Environmental Policy Act.

Following two years of review, the Dis

trict Court granted summary judgment for

respondent, Mall Properties, Inc., on the

merits, vacated the Corps' denial deci

sion as being contrary to law, enjoined

the Corps on remand from engaging in

i

previously accepted, long-standing regu

latory practice (the consideration of

social and economic, as well as environ

mental effects of the project) and did

not retain jurisdiction. Petitioner,

City of New Haven, which had successfully

sought permit denial before the Corps and

was granted intervention under Rule 24(a)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

by the District Court, appealed. The

First Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed

the appeal because the District Court

remand order was not a final judgment.

The Court of Appeals further held that

New Haven could not appeal because the

respondent, Secretary of the Army, chose

not to appeal.

The questions presented are:

1. Whether, under the Adminis

trative Procedure Act and 28 U.S.C.

ii

§ 1291, a District Court decision grant

ing summary judgment on the merits, va

cating an agency decision based on a new

legal standard and enjoining previously

accepted, long-standing federal agency

practice on remand is not a "final deci

sion" because the District Court did not

yet grant the respondent, Mall Proper

ties, Inc., ultimately what it wanted

(i. e. , a fill permit to construct a re

gional shopping mall).

2. Whether 28 U.S.C. § 1291

forbids a successful party before a fed

eral agency and one granted intervention

under Rule 24(a) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, from appealing an ad

verse District Court decision because the

federal agency chooses not to appeal.

iii

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS

The petitioner is the City of

New Haven, Connecticut. The respondents

are John 0. Marsh, Jr., Secretary of the

Army, Lt. General E. R. Heiberg, Chief of

the United States Army Corps of Engi

neers, Col. Thomas A. Rhen, Division En

gineer, New England Division and the

United States Army Corps of Engineers,

Department of the Army. The respondents

also include Mall Properties, Inc., a

corporation organized under the laws of

the State of New York that maintains its

principal office in the City and County

of New York.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINIONS BELOW .................... 2

JURISDICTION ...................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY AND

REGULATORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED . 3

STATEMENT.......................... 4

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION. . 23

CONCLUSION........................ 52

ADDENDUM.......................... la

APPENDIX

(Separate Volume)

Appendix A .......................la

Appendix B .......................3a

Appendix C ......................24a

Appendix D ......................25a

Appendix E ......................85a

Appendix F ......................93a

Appendix G .....................102a

Appendix H .....................104a

- v -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Animal Lovers Volunteer Assoc,

v. Weinberger. 765 F.2d 937

(9th Cir. 1985)............ 45, 47

Bachowski v. Userv. 545 F.2d

363 (3d Cir. 1976)........ 22

Bender v. Clark. 744 F.2d 1424

(10th Cir. 1984).......... passim

Bersani v. EPA.

674 F. Supp. 405 (N.D.N.Y.

1987), aff'd. Nos.87-6275,

87-6295, slip op.

(2d Cir. June 8, 1988) . . . 42

Bersani v. EPA. Nos. 87-6275,

87-6295, slip op.

(2d Cir. June 8, 1988) . . . 46

Brown Shoe Co. v. United

States. 370 U.S. 294 (1962). 47

Bryant v. Yellen.

447 U.S. 352 (1980)........ 48, 49

Catlin v. United States.

324 U.S. 229 (1945)........ 28

Chevron U.S.A.. Inc, v. NRDC.

467 U.S. 837 (1984)........ 26, 40,

41, 43Cohen v. Beneficial

Industrial Loan Corn.,

337 U.S. 541 (1949)........ 29, 33

- vi -

Davis v. Coleman. 521 F.2d

661 (9th Cir. 1975)....... 46

Dickinson v. Petroleum

Conversion Coro.,

338 U.S. 507 (1950)........ 34, 36

Eisen v. Carlisle and

Jaccruelin. 417 U.S.

156 (1974) ................ passim

CASES - Continued PAGE

Faulkner Hospital Corp.

v, Schweicker. 537

F. Supp. 1058 (D. Mass.1982), aff’d . 702

F.2d 22 (1st Cir. 1983). . . 17

Faulkner Hospital Corp.

v. Schweicker. 702

F.2d 22 (1st Cir. 1983). . . 30

Gillespie v. United

States Steel Corp.,

379 U.S. 148 (1964)........ 28

Glass Packaging Institute

v. Reaan. 737 F.2d 1083

(d .c . cir.), cert, denied/

469 U.S. 1035 (1984) . . . . 45, 47

Mall Properties. Inc, v.

Marsh. 672 F. Supp. 561

(D. Mass. 1987), aff'd.

841 F .2d 440 (1st Cir.

1988), petition for re

hearing denied. No.

87-1827, slip op.

(1st Cir. April 7, 1988) . . passim

vii

CASES - Continued PAGE

McGourkev v. Toledo & O.C.

Rv.. 146 U.S. 536 (1892) . . 23, 34

Metropolitan Edison Co.

v. People Against

Nuclear Energy (PANE),

460 U.S. 766 (1983)........ passim

Morton v. Ruiz.

415 U.S. 199 (1974)........ 42

NL Industries, Inc, v.

Secretary of Interior. 777

F.2d 433 (9th Cir. 1985) . . 49

Olmsted Citizens For a

Better Community v.

United States, 793

F.2d 201 (8th Cir. 1986) . . 44

Ono v. Harper. 592 F. Supp.

698 (D. Haw. 1983)........ 45

Pacific Northwest Bell

Telephone Co. v. Dole,

633 F. Supp. 725

(W.D. Wash. 1986).......... 45

Paluso v. Mathews,

573 F .2d 4 (10th Cir. 1978). 47

Pauls v. Secretary of

Air Force, 457 F.2d

294 (1st Cir. 1972)........ 21, 29

Rochester v. United States

Postal Service. 541 F.2d

967 (2d Cir. 1976)........ 46

viii

CASES - Continued EASE

Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc,

v. Watt, 713 F .2d 525

(9th Cir. 1983). . . .

Transportation-Communication Division v. St. Louis-San

Francisco Rw. . 419 F.2d 933

(8th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 400 U.S. 818 (1970).

Udall v. Tallman.

380 U.S. 1 (1965)..........

United States v. Alcon

Laboratories. 636 F.2d 876

(1st Cir.), cert. denied,

451 U.S. 1017 (1981) . . . .

United States v. AT&T. 642

F.2d 1285 (D.C. Cir. 1980) .

United States v. Pern,

289 U.S. 352 (1933)........

Zabel v. Tabb. 430 F.2d 199

(5th Cir. 1970), cert.

denied. 401 U.S. 910 (1971).

STATUTES

Administrative Procedure

Act, 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A). .

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1)

28 U.S.C. § 1291. .

- ix -

49

30

42

21

49, 51

41

41

3, 18,

23, 24

3

passim

Clean Water Act,

33 U.S.C. § 1344 ........... passim

Rivers and Harbors Appropria

tion Act of 1899,

33 U.S.C. § 403............. passim

STATUTES — Continued PAGE

National Environmental

Policy Act of 1969,

42 U.S.C. § 4321 .......... passim

42 U.S.C. § 4331(b)........ passim

42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C) . . . passim

REGULATIONS

Public Interest Review Regula

tion of the United States

Army Corps of Engineers,33 C.F.R. § 320.4(a) . . . . 333 C.F.R. § 320.4(g) . . . . 3, 12

13

Regulations of the Council

on Environmental Quality,40 C.F.R. § 1502.16........ 440 C.F.R. § 1508.7 ........ 4, 14

2640 C.F.R. § 1508.8(a). . . . 440 C.F.R. § 1508.8(b). . . . 4, 14

4740 C.F.R. § 1508.14........ 4, 26

MISCELLANEOUS

Connecticut Bluebook (1987 ed). 17

Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 24(a)............ 7, 48

49

MISCELLANEOUS - Continued PACE

Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 54 ..............

Final Environmental Impact

Statement, § § IV-10, IV-21,

IV-22, IV-29, IV-31-34 . . .

32

6-7

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1988

NO.

CITY OF NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT,

PETITIONER,

V.

JOHN 0. MARSH, JR., SECRETARY OF

THE ARMY, ET AL.

RESPONDENTS.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

The City of New Haven, Connecti

cut respectfully petitions for a writ of

certiorari to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the

First Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Ap

peals (App. B)— ^ is reported at 841

F.2d 440 (1st Cir. 1988). The denial of

the petition for rehearing and suggestion

for rehearing gn banc (App. A) is unre

ported at this time. No. 87-1827, slip

op. (1st Cir. April 7, 1988). The memo

randum and order of the District Court

(App. D) is reported at 672 F. Supp. 561

(D. Mass. 1987).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of

Appeals (App. B) was entered on March 11,

1988. The petition for rehearing and

suggestion for rehearing gn banc (App. A)

The opinions below and other rele

vant materials are bound in a sepa

rate Appendix, hereinafter referred

to as "App. ___."

2

diction of this Court is invoked under 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY AND

REGULATORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves issues under

28 U.S.C. § 1291 (Add. at 5a)-7; rele

vant provisions of the Clean Water Act,

33 U.S.C. § 1344 (Add. at 4a-5a); the

Rivers and Harbors Act, 33 U.S.C. § 403

(Add. at 3a-4a); the National Environmen

tal Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. § § 4321,

4331(b) & 4332(2)(C)(Add. at la-3a) ; the

Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C.

§ 706(2)(A)(Add. at 5a); regulations of

the United States Army Corps of Engi

neers, 33 C.F.R. § 320.4(a) & (q) (Add.

at 6a-8a); regulations of the Council on

was denied on April 7, 1988. The juris

The texts of all cited statutes and

regulations are set forth in the

Addendum to this Petition, herein

after referred to as "Add. at ___."

3

Environmental Quality, 40 C.F.R. § §

1502.16, 1508.7, 1508.8(a), (b), &

1508.14 (Add. at 8a-lla).

STATEMENT

1. This suit for declaratory

and injunctive relief was filed by re

spondent, Mall Properties, Inc., in the

United States District Court for the Dis

trict of Massachusetts on October 29,

1985 against the respondent, Secretary of

the Army and various officials of the

United States Army Corps of Engineers

("U.S. ACOE" or "Corps"), under section

404 of the Clean Water Act ("CWA"), 33

U.S.C. § 1344, section 10 of the Rivers

and Harbors Act ("RHA"), 33 U.S.C. § 403

and section 102(2)(C) of the National

Environmental Policy Act ("NEPA"), 42

U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C). Mall Properties,

Inc. challenged the final decision of the

4

New England Division of the U.S. ACOE

denying its application for a permit to

deposit one million cubic yards of fill

onto the floodplains and wetlands of the

Quinnipiac River in North Haven, Connect

icut in order to construct a 1.2 million

square foot regional shopping mall. The

primary basis for its challenge was that

the U.S. ACOE was without statutory

authority to consider, as part of its

permit denial decision, the adverse so

cial, economic and racial effects of the

proposed mall on the region, particularly

the City of New Haven.

2. a. The City of New Haven is

one of the nation’s oldest (founded in

1638) and poorest municipalities (7th in

the United States according to the 1980

census; 23% of its residents are below

the poverty level). It is immediately

5

adjacent to North Haven and is the larg

est municipality within the 10-town re

gion that would be served by the proposed

mall. Moreover, the proposed mall is

less than 8 miles from New Haven's cen

tral business district, easily accessible

by numerous roadways from various loca

tions throughout the region (including

New Haven) and situated on the Quinnipiac

River, which flows downstream through New

Haven and into its Harbor. The Quin

nipiac River has historically been a

source of serious flooding problems.

b. The proposed North Haven

Mall would generate 55,000 motor vehicle

trips per day, 500 to 3,077 tons of solid

waste per year, and require the filling

of more than 30 acres of wetlands and

open water. Final Environmental Impact

Statement ("EIS") at IV-10, IV-22,

6

City of New Haven, the proposed mall

would result in the estimated loss of 600

jobs, more than one million dollars a

year in tax revenues (1982 dollars), ap

proximately 20 percent of its retail

sales, one or more major department

stores and other ancillary, adverse so

cial, economic and racial effects. Final

EIS, IV-31-34, IV-29.

3. The City of New Haven

actively opposed the respondents' appli

cation before the U.S. ACOE on environ

mental (i.e .. flooding, wetlands loss),

social and economic grounds, including

the adverse aesthetic and racial strati

fication impact it will have on the

region. New Haven was granted interven

tion as of right under Federal Rule of

Civil Procedure 24(a) in the District

IV-21. With specific reference to the

7

Court. App. E. The District Court

stated:

The court finds that

the City of New Haven has

met the requirements for

intervention of right. The

City of New Haven seeks to

intervene under Rule 24

primarily to protect the

economic interests the

Corps allegedly relied upon

in denying the permit.

Therefore, unlike the envi

ronmental groups, the City

of New Haven is directly

interested in the "econom

ics" question which plain

tiff has raised by this

action. An adverse ruling

by the court on this issue

would limit the City's

ability to protect its in

terests on remand.

Plaintiff [Mall Prop

erties, Inc.] argues that

the Corps adequately repre

sents the City's interests

in this action. The City

replies that the government

may not represent its in

terests adequately, arguing

that the government has a

duty to protect the public

interest, while the City

seeks to protect its unique

interests. The City has

also outlined the history

of disagreements between

8

the Corps and the City

which have arisen during

the permit litigation be

fore the Corps. The court

also notes that the Corps

does not object to the

City's intervention in this

case.

App. E at 90a-92a. The District Court

denied the motion of national and local

(Connecticut and North Haven-based) envi

ronmental and citizens groups to inter

vene (id. at 92a), despite the participa

tion of most such groups in the admin

istrative proceeding below. No appeal

was taken from the District Court's

ruling.

4. The U.S. ACOE, following

six years of review and the preparation

of an Environmental Impact Statement

("EIS") under the National Environmental

Policy Act (42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C)),

denied respondent Mall Properties'

application in a "proposed Final Order"

9

of November 15, 1984 v (App. F) and a

"Final Order" of August 20, 1985 (App.

3/H). The August 1985 denial was based

3/ In November 1984, the New England

Division Engineer affixed his sig

nature to a 45-page "Record of

Decision" ("ROD")(App. F) denying

respondents’ application for a fill

permit because of: (i) the "cumula

tive impact from other past, present

and reasonably foreseeable future

actions affecting wetlands, flood

plains and flooding"; (ii) the "ir

retrievable loss of 25 acres of wet

lands"; (iii) "negative impacts on

the quality of life in North Haven";

and (iv) adverse "socio-economic

impacts, in particular, those af

fecting the City of New Haven." Id.

at 98a. The factual basis for this

last reason for permit denial was,

inter alia, that:

New Haven provides services and

an environment for a community

with a sizeable low to moderate

income population. This popula

tion is less able to travel to

reach services at other loca

tions. It is more dependent

upon a vibrant, viable city to

provide services and a healthy,

safe and desirable environment.

FOOTNOTE CONTINUED

10

on three grounds: (i) "a net loss in

wetland resources" (App. H at 270a); (ii)

"flooding impacts" (id. at 270a); and

(iii) the "socio-economic impacts this

project would have on the City of New

Haven" (id . at 270a) .

Before the Corps, and during the

District Court proceeding, the Department

FOOTNOTE 2/ CONTINUED:

Id. at 98a. This November 1984 ROD

was not made public. A copy was

made available only to the respon

dent, Mall Properties, Inc. The

fact of its existence was not made

known to New Haven until June 1985.

Neither the November 1984 ROD nor

the August 1985 ROD are designated

as "proposed" or "final" — termi

nology used only by the District

Court.

It is New Haven's position, sup

ported explicitly by the New England

Division Engineer, that the August

1985 ROD is premised expressly on

and can only be understood in refer

ence to the November 1984 ROD. See

App. H at 155a.

11

of Interior supported the Corps' concerns

about wetlands. App. H at 132a. Fur

thermore, the Department of Housing and

Urban Development and the Governor's Of

fice of Policy and Management supported

the Corps' concerns about adverse social,

economic and racial impacts (id., at 139a)

and the Federal Emergency Management

Agency supported the Corps' concerns

about flooding (id. at 142a) . All such

supporting comments were submitted to the

Corps as part of the EIS process, consid

ered by it pursuant to NEPA and in accor

dance with its "Public Interest Review"

regulation (33 C.F.R. § 320.4)(which re

quires consideration of "economics" and

"the needs and welfare of the people,"

promulgated pursuant to, inter alia.

NEPA, CWA and the RHA (Add. 6a-8a)), and

i

12

identified in its August 1985 ROD. App.

H at 266a.

5.a. The District Court, on

cross-motions for summary judgment filed

by all the parties, vacated the U.S. ACOE

decision on September 8, 1987. Mall

Properties. Inc, v. Marsh, 672 F. Supp.

561 (D. Mass. 1987). App. D. It deter

mined that the permit denial decision,

based on the Corps' Public Interest Re

view regulations (33 C.F.R. § 320.4),

NEPA, the CWA and the RHA, "was not made

in accordance with law" because, inter

alia, "the Corps exceeded its authority .

. . by basing its denial of the permit on

socio-economic harms [to the region and

the City of New Haven] that are not prox-

imatelv related to changes in the physi

cal environment," caused by the fill.

App. D at 26a (emphasis added)(relying on

13

the "standard" set forth in Metropolitan

Efl.is.Qh__Co. v. People Against Nuclear

Energy (PANE). 460 U.S. 766 (1983)).

Contrary to the position of the Petition

er and the U.S. ACOE that, under the

Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ)

and U.S. ACOE's regulations, such econom

ic and social impacts must be considered

because they are "reasonably foresee

able," (40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.8(b), 1508.7)

indirect effects of a regional mall on

the region, the District Court stated:

"The record reveals that these impacts

would not result from any effect the mall

would have on the physical environment

generally or wetlands particularly.

Rather, it is the economic competition

for New Haven which would result from the

mere existence of a mall anywhere in

North Haven . . . [even though the] Corps

14

did find that there was no alternative

site for the mall in North Haven." App.

4/D at 36a.~

Moreover, although Metropolitan

Edison involved only the threshold ques

tion of whether an EIS was required in

light of alleged psychological harm from

the restart of an already existing facil

ity (see 460 U.S. at 768), the District

Court here (i) concluded the "proximately

related" standard applied to all NEPA

questions (including, for the first time,

which impacts should be addressed follow

ing a determination to prepare an EIS for

a new project): and (ii) determined that

the reasoning of "pre-Metropolitan Edison

The District Court incorrectly

stated that "North Haven is a suburb

about 10 miles from New Haven, Con

necticut." App. D at 26a-27a. As

stated at the outset, New Haven and

North Haven are adjacent to each

other.

15

NEPA cases," including those from the

5th, 6th, 7th and 2nd Circuits concerning

whether reasonably foreseeable social and

economic impacts had to be considered in

an EIS that was premised on recognized

environmental harm, have been "eliminated

by Metropolitan Edison." App. D at 70a.

b. The District Court also

stated that it "is elementary . . . that

in our system of government, decisions

concerning which competing constituency's

economic interests ought to be preferred

are traditionally made by democratically

accountable officials," (App. D at 75a),

such as the Governor of Connecticut but

not the U.S. ACOE; and that, in the

legislative history of the statutes in

volved here, there "is no suggestion that

16

[the Corps] was perceived by those enact

ing the relevant statutes to have exper

tise concerning whether the economic in

terests of aging cities or their newer

suburbs should as a matter of public pol-

5/icy be preferred." App. D at 75a.

Finally, the District Court,

relying on the First Circuit's decision

in Faulkner Hospital Corp. v. Schweicker,

537 F. Supp. at 1071 (D. Mass. 1982),

aff'd. 702 F .2d 22 (1st Cir. 1983), va

cated the U.S. ACOE decision, enjoined it

from any further consideration of the

mall's social, economic or racial impacts

on the region, including New Haven, and

It should be noted that New Haven

and North Haven were founded in the

17th and 18th Centuries, respective

ly. Connecticut Blue Book (1987

ed.) .

17

remanded "for further proceedings consis

tent with this decision." App. D at

84a.^

The District Court did not

retain jurisdiction. Additionally,

throughout the District Court proceeding,

the Justice Department — on behalf of

the Corps — supported the August 1985

permit denial decision. Moreover, no

questions were raised about the adequacy

of the evidence before the District Court

or the need for the Court to postpone its

In its Complaint, respondent Mall

Properties, Inc., sought a judgment

“directing ACOE to issue Mall Prop

erties the subject permits . . . ."

(Complaint If 3b). At the suggestion

of the District Court, respondent

recognized that such relief was not

available to it, and that, under the

Administrative Procedure Act, 5

U.S.C. § 706(2)(A), and other juris

prudential considerations, the ap

propriate judicial remedy was a re

mand to the U.S. ACOE for further

proceedings.

18

decision on the merits of the issues,

pending some further factual development

or the resolution of a legal issue by the

U.S. ACOE.

6.a. The City of New Haven ap

pealed on September 14, 1987. On Novem

ber 19, 1987 — after the expiration of

the appeal period — the Justice Depart

ment informed the Court of Appeals, with

out explanation, that it had determined

not to appeal and that New Haven’s appeal

should be dismissed. No reasoning, case

citations, subsequent brief, memoranda or

affidavit was ever filed by the Justice

Department to support its motion, nor did

the Court order it to do so, despite

Petitioner's formal request. On December

2, 1987, respondent Mall Properties

stated that it was joining the Govern

ment's motion to dismiss.

b. On March 11, 1988, a panel

19

of the Court of Appeals granted, without

oral argument, the U.S. ACOE's motion to

dismiss, concluding the "remand order" of

the District Court is "not a final judg

ment" and, therefore, not appealable un

der 28 U.S.C. § 1291. App. B at 5a.

Focusing on Mall Properties'

ultimate objective, (i.e.. to have the

Corps grant the permit to build a region

al mall) as being the controlling crite

rion determining "finality," the Court of

Appeals concluded that because "the Dis

trict Court's remand order does not grant

Mall ultimately what Mall wants," the

"court's order is but one interim step in

the process toward Mall's obtaining its

ultimate goal." "The litigation," the

Court stated, "has not ended." App. B at

8a.

Moreover, although the Court of

Appeals stated that "generally orders

20

remanding to an administrative agency are

not final, immediately appealable or

ders," (id. at 10a) (citing Pauls v. Sec

retary of Air Force. 457 F.2d 294 (1st

Cir. 1972)), it also characterized other

cases where appeals were allowed as "ex

ceptions," to this general rule, such as

United States v. Alcon Laboratories. 636

F. 2d 876 (1st Cir.), cert. denied. 451

U.S. 1017 (1981). The Court, recognizing

that in one such "exception" — Bender v.

Clark, 744 F.2d 1424 (10th Cir. 1984) —

the government was allowed to appeal from

a substantive decision on the merits that

required a remand, nonetheless concluded

that because the U.S. ACOE did not appeal

here, Bender had no application to New

Haven. App. B at 16a-18a.

The Court of Appeals also con

cluded that New Haven "has not been fore

closed from participating in the proceed

ings on remand" because "[p]resumably, it

21

can urge environmental reasons why the

permits should be denied" (id. at 18a),

and, after review by the Corps and a sub

sequent District Court decision, New

Haven can "appeal to this Court and . . .

argue that the original permit denial

. . . was proper . . . Id. at 18a.

Thus, "review of the socio-economic issue

the City now wants to present, is not

denied; it is simply delayed." Id- at

18a-19a.

Finally, the Court concluded

that allowing the appeal "would violate

. . . efficiency . . . ." Id- at 20a.

Although stating that, "were review

granted now and were we to conclude the

District Court erred, an unnecessary ad

ministrative proceeding could be averted

[fn. omitted]" (id. at 20a-21a), the

Court found, relyinq on Bachowski v.

dS-gry, 545 F.2d 363 (3d Cir. 1976), that

22

"wisdom" required that "we focus on sys

temic, as well as particularistic, im

pacts." Id. at 21a-22a.

7. On March 24, 1988, New

Haven filed its Petition for Rehearing

and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc,

which was denied by the First Circuit's

Order dated April 7, 1988. App. A.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

The decision of the Court of

Appeals establishes a pernicious, new

rule for determining "finality" in judi

cial review under the Administrative

Procedure Act ("APA") that renders mean

ingless the efforts of this Court, since

at least McGourkev v. Toledo & O.C. Rv. .

146 U.S. 536, 544-545 (1892), to provide

a modicum of protection to the debilitat

ing effect of delaying justice to an ad

versely affected party. As a practical

matter, the Court of Appeals' opinion

23

restricts the criteria for determining

"finality" to one factor and to the ef

fect on one party: whether the applicant

received ultimately what i£ wanted from a

federal agency (in this case, an econom

ically valuable fill permit to construct

a mall), regardless of the fact such

relief is not judicially available. Un

der such a standard, the Judicial Branch

becomes an advocate for the applicant;

assuring, in the end, that the substan

tive content or the practical effect of a

District Court decision will not be mean

ingfully reviewed until the applicant

extracts his alleged economic benefit

from the Executive Branch. This Court,

as argued below, has never articulated

such a fundamentally unfair and constitu

tionally inappropriate .rule. For this

reason alone, review by this Court is

warranted.

24

Here, however, much more is at

stake. A new, substantive legal standard

concerning NEPA, the CWA and the RHA has

been articulated by the District Court.

It is not trivial. Based on the misap

plication of this Court's decision in

Metropolitan Edison v. PANE, the District

Court "eliminated" more than a decade of

judicial precedents from the 2nd, 5th,

7th and 6th Circuits (App. D at 70a);

and, it enjoined the U.S. ACOE's long

standing interpretation of its statutory

obligations to consider the reasonably

foreseeable- effects of a project and the

"Public Interest," including economic

effects and the welfare of the people, in

rendering a permit decision. id. at 26a,

77a, 79a, 83a, 84a. It also has raised

troublesome questions about the continued

viability of the Council on Environmental

25

Quality's NEPA regulations defining the

"human environment" (40 C.F.R. § 1508.14)

and "indirect" (40 C.F.R. § 1508.7) and

"cumulative" impacts (40 C.F.R.

§ 1508.7). See Add. at 11a, 9a. In the

end, the District Court impermissibly

exceeded its role by failing to accord

any deference to the U.S. ACOE's inter

pretation of the CWA, NEPA and the RHA

and the specific effects of this pro

ject. Chevron U.S.A.. Inc, v. NRDC. 467

U.S. 837 (1984).

The District Court's decision

remains unreviewed by the Court of Ap

peals, unreviewable by the U.S. ACOE on

remand, and unreviewable by the District

Court under the law of the case doc

trine. The incongruous effect on New

Haven is deadening. We are estopped from

challenging it below and precluded from

appealing it now. Moreover, as a practi

cal matter, the decision's reasoning is

26

stifling to any litigant who is dependent

on the federal government — in civil

rights, equal employment opportunity or a

broad range of environmental cases — to

vindicate an important public and judi

cially cognizable issue directly affect

ing such a litigant. Based on an inar-

ticulated philosophy of government or the

political discomfort of being on the

"wrong side," an agency — by not appeal

ing — can thwart the appeal of a party

that was a successful proponent before

the agency and, in the process, thwart

the. agency’s statutory mission and, in

this case, the meritorious reasoning of

that agency after six years of study.

The Court of Appeals' decision

warrants the timely exercise of this

Court’s supervision on the question of

"finality" and the appeal rights of an

intervenor, the petitioner, City of New

Haven.

27

l.a. The Court of Appeals' anal

ysis is flawed in its premise. "We do

not view the [District Court] remand or

der," the Court of Appeals stated, "as

meeting the traditional definition of a

final judgment, that is, one which 'ends

the litigation on the merits and leaves

nothing for the court to do but execute

the judgment,' Catlin v. United States.

324 U.S. 229, 233 (1945)." App. B at

8a. This Court has eschewed such a "tra

ditional definition" as being either the

beginning or the end of a proper analysis

of whether a decision is "final" under 28

U.S.C. § 1291. The correct analytical

premise is that "a decision 'final' with

in the meaning of § 1291 does not neces

sarily mean the last order possible to be

made in a case." Gillespie v. United

s t9 t e?__steel Corp.. 379 U.S. 148, 152

28

(1964)(emphasis added). And, more re

cently: "We know, of course, that § 1291

does not limit appellate review to 'those

final judgments which terminate an action

. . . , ' but rather that the requirement

of finality is to be given a 'practical

rather than a technical construction.'"

Eisen v. Carlisle and Jacouelin, 417 U.S.

156, 170-71 (1974)(emphasis added)(quot

ing Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan

Corn.. 337 U.S. 541, 545 (1949)).

Having started on a faulty prem

ise and inappropriate definition, the

Court of Appeals strayed further. Seem

ingly seeking a simple factual predicate

to meet the "traditional definition," it

further defied this Court's teachings and

elevated a "verbal formula" (Eisen v.

Carlisle and Jacguelin, 417 U.S. at 170),

from Pauls v. Secretary of Air Force, 457

29

F.2d at 297-98)("generally orders remand

ing to an administrative agency are not

final, immediately appealable orders"),

into a general rule; concluding that the

word "remand" in the formulation of the

District Court's relief is a talisman for

lack of finality. It is not, as the

Court of Appeals own case law (Faulkner

Hospital Corn, v. Schweicker, 702 F.2d 22

(1st Cir. 1983), cited by the District

7 /Court, should have informed it.- The

The Court of Appeals' other cita

tions undermined its own formulation

of an alleged "rule" correlating a

"remand" to a lack of finality. In

each of the cases it cites, a sub

stantive decision on the merits was

expressly eschewed as premature

(App. B at 8a-lla)(s££, e.g.. Trans

portation-Communication Division v.

&£_.__ Louis-San Francisco Rw, . 419

F. 2d 933, 934 (8th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 400 U.S. 818 (1970)), where

in the remands involved were in

tended to resolve a procedural or

evidentiary deficiency, certainly

FOOTNOTE CONTINUED

30

result: the Court of Appeals focused not

on the "practical- (Eisen. 417 U.S. at

170), but rather the "technical construc

tion" of the District Court decision

(i.e.. whether it was a "remand") and its

singular effect on the attainment of the

respondent, Mall Properties, Inc.'s ulti

mate goal (a regional shopping mall).

The effect is a radical, perni

cious departure from the practical, cau

tious approach this Court has admonished

lower courts to undertake in determining

FOOTNOTE 7/ CONTINUED:

not the case here. Moreover, the

Court of Appeals strained its new

"rule" beyond credulity by claiming

that Bender v. Clark. 744 F.2d 1424

(10th Cir. 1984) — where the Court

of Appeals concluded an appeal under

28 U.S.C. § 1291 from a decision on

the merits was permissible where the

District Court had ordered a remand

— is distinguishable from this case

only because it was the government,

not another defendant, that sought

appellate review.

31

"finality." In the end, the Court of

Appeals has taken a rule of limited ap-

plication (see n. 7, sunra). elevated it

beyond its purpose and established a

general rule of broad application to

every case involving a "verbal formula,"

(Eisen. 417 U.S. at 170), "remand to the

agency," contrary to its own customary

practice, the rule of the 10th Circuit in

Bender v. Clark. 744 F.2d at 1426, and

based, inappropriately, on the economic

agenda of the respondent, Mall Proper

ties, Inc., vis-a-vis the Executive

Branch.

b. The Court of Appeals failed

to recognize that the District Court

granted summary judgment, under Rule 54

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

on the substantive merits of the single

issue all the parties agreed was the fun

damental legal linchpin to the U.S. ACOE

32

permit denial: whether, under the CWA,

the RHA, NEPA and the U.S. ACOE "Public

Interest Review" regulation, the ACOE had

the authority to consider, inter alia.

the social and economic effects of the

proposed regional mall on the region,

particularly New Haven. The District

Court by resolving the issue as a matter

of law, vacating the agency's decision

and enjoining the Corps from any further

consideration of such effects, clearly

acted in a manner that “was not 'tenta

tive, informal or incomplete' . . . but

settled conclusively [respondent Mall

Properties, Inc.'s] claim . . . ."

Eisen, 417 U.S. at 171 (quoting Cohen.

337 U.S. at 546). It was, in the words

of 28 U.S.C. § 1291, a "final decision."

c. This Court has not explic

itly articulated a practical construction

(see Eisen, 417 U.S. at 170), concerning

33

"finality" directly applicable to the

broad range of APA cases wherein an agen

cy decision is "remanded" for further

consideration. The absence of such es

sential guidance is, once again, a grow

ing lack of harmony (see McGourkev v.

Toledo & O.C. Rv.. 146 U.S. 536 (1892)),

among the Circuits and the formation of a

wholly inappropriate and harmful rule

within the First Circuit.

2.a. "[T]he danger of denying

justice [to New Haven] by delay," (Dick

inson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp.. 338

U.S. 507, 511 (1950)), permeates the

Court of Appeals decision. More is at

stake, however, than the indefensible

consequence of delaying resolution of the

issue concerning the U.S. ACOE's author

ity to consider social and economic ef

fects. New Haven has been denied the

most elementary notions of justice. By

34

"delaying" New Haven's ability to have

the issue even considered until it

reaches the Court of Appeals again, the

decision places petitioner in a very pre

dictable "catch-22"; constantly forced to

argue that it has a right to be heard on

a legal issue that neither the U.S. ACOE

nor the District Court have any duty to

consider. Under such circumstances, New

Haven's "standing" under Article III to

even argue economic or social reasons for

permit denial would certainly be chal

lenged. So too would New Haven's stand

ing to argue some "physical environmen

tal" issues as that term is defined by

the District Court. Moreover, it could

be two more rounds of procedural and

jurisdictional (i.e., standing) litiga

tion before the Court of Appeals reaches

the merits of the social-economic issue,

if ever. The U.S. ACOE could deny the

35

permit again, on other grounds, and the

District Court could affirm the denial.

This, of course, is not the end

of the serious impediments the Court of

Appeals has created. Its analysis of res

judicata and law of the case provides

doubtful comfort. Dickinson. 338 U.S. at

511. In order to diminish the risk that

the Court of Appeals is incorrect on the

issues of "finality,- res judicata and

law of the case, New Haven is, as a prac

tical matter, precluded from seeking ju

dicial review in any other jurisdiction

except Massachusetts even though the Dis

trict Court below did not retain juris

diction and petitioner is entitled to

file any subsequent challenge to the

Corps in Connecticut or the District of

Columbia. "This scenario of 'possibil

ities' is too conjectural to avoid reach

ing a more just result" (Bender v. Clark.

36

744 F.2d at 1428), particularly where, as

here, the Court of Appeals acknowledged

that "were review granted now and were we

to conclude the District Court erred, an

unnecessary administrative proceeding

could be averted." App. B at 21a.

b. By making the attainment of

the respondent, Mall Properties, Inc.'s,

economic goal the essential focus of its

analysis, the Court of Appeals made no

meaningful effort to undertake an evalua

tion of the effect of its decision on the

parties. There is no "inconvenience and

cost [ ]," (Eisen, 417 U.S. at 171), to

Mall Properties, Inc. in the immediate

resolution of the legal issue i£ has

wanted resolved since filing its Com

plaint in October 1985. There is no dis-

cernable harm to the U.S. ACOE; no gov

ernment project is at stake nor is the

filling of wetlands or the construction

37

of suburban shopping malls a statutory or

policy objective. The adverse harm to

New Haven and the the administration of

the CWA, NEPA and the RHA is clear and

immediate.

The City of New Haven has ac

tively opposed the construction of the

North Haven Mall since 1980. It took the

U.S. ACOE almost six years to render its

ROD, 45 pages in length, denying the per

mit. The litigation has now consumed

almost three additional years. For a

municipality like New Haven — the 7th

poorest in the United States, according

to the 1980 census, for cities over

100,000 — such an effort has placed a

substantial burden on New Haven's tax

payers. Moreover, the resolution of the

legal issues in this case are of funda

mental importance to the entire metro

politan region.

38

c. The fundamental flaw in the

District Court's reasoning stemmed from

its wholly unwarranted intrusion into

interpreting the statutory obligations of

the U.S. ACOE. Relying on the respon

dent, Mall Properties, Inc.'s, character

ization of the permit denial as being

based on economic competition^ rather

than social and economic impacts. the

District Court decided that: (i) the

U.S. ACOE is not "democratically account

able" (App. D at 75a) and cannot make

such a "competition" judgment; and,

therefore, (ii) the Court "is called upon

to discern the scope of the authority to

consider economic factors which has been

App. D at 36a. The notion of "eco

nomic competition" was nowhere ad

dressed by the U.S. ACOE in its ROD

and clearly not reflected in the

"Conclusions" reached in its Novem

ber 1984 or August 1985 ROD'S.

FOOTNOTE CONTINUED

39

delegated to, and exercised by, the

Corps.” at 42a. Unable to find any

direct legislative history under the RHA,

CWA or NEPA, that "unambiguously ex

pressed [the] intent of Congress" (Chev

ron U.S.A., Inc, v. NRDC. 467 U.S. at

843), that the U.S. ACOE was precluded

from considering social and economic fac

tors, the District Court grafted onto

that history this Court's "proximately

related" standard from Metropolitan Edi

son (id. at 59a-60a), although such a

standard is nowhere referred to or cited

FOOTNOTE £./ CONTINUED:

Moreover, no federal or state agency

raised any question about "competi

tion"; all participants before the

U.S. ACOE — HUD, the Department of

the Interior/U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service and the Connecticut Office

of Policy and Management — stated

that adverse environmental, social,

economic or racial impacts warranted

permit denial.

40

in the legislative history in this con

text. Moreover, the District Court made

no meaningful effort to assess whether

"the agency's [interpretation] is based

on a permissible construction of the

statute" (Chevron U.S.A.. Inc, v. NRDC.

467 U.S. at 843), despite the fact such

social or economic effects have been:

(i) considered by the Corps since 1933

(£££ United States v. Pern. 289 U.S. 352

(1933); Zabel v. Tabb. 430 F.2d 199, 207

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied. 401 U.S.

910 (1971) (The RHA "itself does not put

any restrictions on denial of a permit or

the reasons why the Secretary may refuse

to grant a permit . . . .")); (ii) inte

grated into the Corps' Public Interest

Review regulation since 1974 (App. D at

51a); (iii) required, under the rea

sonably foreseeable standard, to be

41

considered by the CEQ regulations^7;

and (iv) formally considered, based on

six years of legal and factual analysis

in this case and, with even greater

breath and detail, in Bersani v. EPA. 674

F. Supp. 405 (N.D.N.Y. 1987), aff'd. Nos.

87-6275, 87-6295, slip op. (2d Cir. June

8, 1988)(economic viability and market

place impacts of proposed mall on the

region considered by the U.S. ACOE and

EPA in CWA permit decision). The Dis

trict Court, in the end, emerged as the

"democratically accountable" (App. D at

75a) Branch of government, failed to show

any deference to the U.S. ACOE's inter

pretation of its obligations (Udall v.

Ta1lman. 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965); Morton v.

Ruiz, 415 U.S. 199, 231 (1974)), and

In fact, the District Court does not

even cite the CEQ regulations.

42

Msubstitute[d] its own construction of a

statutory provision for a reasonable in

terpretation made by the . . . agency."

Chevron U.S.A., Inc, v. NRDC, 467 U.S. at

844.

The U.S. ACOE, for an indetermi

nate period of time, is now free to im

pose within the First Circuit — if not

elsewhere — a new legal standard con

cerning indirect, induced or cumulative

social and economic impacts that departs

from its previously accepted practice, as

acknowledged by the U.S. ACOE in the Dis-.

trict Court. See Federal Defendant's

Reply Memorandum, on Cross-Motions for

Summary Judgment at 9. At stake is the

daily administration of three major

statutes: NEPA, CWA and RHA.

Moreover, no court — including

the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit relied upon by the District Court

here (App. D at 68a) — has applied the

43

"proximately related" standard beyond the

limited, threshold question of whether an

EIS should be prepared. In Olmsted Cit

izens_For a Better Community v. United

States, 793 F.2d 201 (8th Cir. 1986), the

Eighth Circuit was confronted with the

threshold question of whether an EIS was

required based not on any allegations of

environmental harm but on the possible

"introduction of weapons and drugs into

the area . . . [and] . . . an increase in

crime . . . ." Id., at 205. It concluded

an EIS was not necessary, relying on the

"proximately related" standard of Metro

politan Edison, 460 U.S. 766 (1983), the

fact that “we are not convinced that Olm

sted Citizens has identified any signif

icant impacts on the physical environment

. . ." (Olmsted. 793 F.2d at 206) and

that "[e]ven before Metropolitan Edison"

(id.), a similar result would have lied.

Moreover, subsequent court decisions have

44

interpreted Metropolitan __Edison to be

limited to the threshold question of

whether NEPA applies in the absence of

recognized environmental impacts. See

Pacific_Northwest_Bell Telephone Co. v .

Dole. 633 F. Supp. 725, 727 (W.D. Wash.

1986); Ono v. Harper. 592 F. Supp. 698,

701 (D. Haw. 1983); Animal Lovers Volun

teer Assoc, v. Weinberger. 765 F.2d 937,

938 (9th Cir. 1985); Glass Packaging In

stitute v. Renan. 737 F.2d 1083, 1091-93

(D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1035

(1984). Here, it is beyond peradventure

that: (i) significant physical, environ

mental impacts were present (i.e.. depos

iting one million cubic yards of fill;

harm to 30 acres of wetlands; flooding

problems, etc.); (ii) the U.S. ACOE pre

pared a multi-volume EIS — a legal and

factual determination not challenged be

low; (iii) numerous federal and state

agencies substantiated the environmental,

45

social and economic impacts of the pro

ject; and (iv) the demonstrable, physi

cal, economic and social impacts on the

region, including New Haven, was thor

oughly documented and found by the U.S.

ACOE in its EIS and ROD'S. Under such

circumstances, the District Court deci

sion — by extending the "proximately

related" standard of Metropolitan Edison

and precluding consideration of the re

gional mall's social and economic effects

on the region — is directly in conflict

with those of at least the 2nd and 9th

Circuits (Rochester v. United States Pos

tal Service. 541 F.2d 967, 973 (2d Cir.

1976); ge.rg.ani__3L«__£PA, No s . 87-6275,

87-6295, slip op. (2d Cir. June 8, 1988);

Davis v. Coleman. 521 F.2d 661, 676-77

(9th Cir. 1975)); the CEQ regulations

requiring consideration of "reasonably

foreseeable" effects (including social

and economic effects that are "later in

46

time or farther removed in distance 40

C.F.R. 1508.8(b)); and the Corps' own

Public Interest Review regulation; and,

without reason and contrary to sound ju

dicial administration, the limited hold

ings of the 9th (Animal Lovers Volunteer

Assoc, v. Weinberger. 765 F.2d at 938-39)

and D.C. Circuits (Glass Packaging Insti

tute v. Reaan. 737 F.2d at 1091).

Certainly, the "issue is a seri

ous and unsettled one . . . Bender v ,

Clark. 744 F.2d at 1428. At stake is the

uncertainty in outcome of such an impor

tant matter and the rights of numerous

permit applicants, the U.S. ACOE and the

public (Paluso v. Mathews. 573 F.2d 4, 8

(10th Cir. 1978)), as well as the fate of

thousands of acres of wetlands within New

England, if not elsewhere; all placed at

risk without appellate review. "The pub

lic interest . . . would lose by such a

procedure." Brown Shoe Co. v. United

47

States, 370 U.S. 294, 309 (1962).

3. The Court of Appeals deter

mination that the Government enjoys some

special status vis-a-vis intervenors with

respect to appellate rights (App. B at

14a-15a) conflicts directly with Brvant

V , Yellen, 447 U.S. 352, 366-68 (1980),

the protection afforded by Rule 24(a) of

the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure and

the precedents of at least the 9th and

D.C. Circuits. If not corrected, its

consequences will be insidious; lurking,

perhaps inconspicuously for now, with

grave effect on those who, in the context

of litigation, are dependent on the gov

ernment to vindicate individual rights or

seek judicial redress on matters of pub

lic importance.

The City of New Haven was

granted the right to intervene under Fed

eral Rule of Civil Procedure 24(a). App.

E at 86a. As an intervenor, New

48

Haven has the right to appeal an adverse

ruling regardless of whether the govern

ment seeks such an appeal. Brvant v.

Yellen. 447 U.S. at 366-68; NL Indus

tries, Inc, v. Secretary of Interior. 777

F .2d 433, 436 (9th Cir. 1985); United

States v. AT&T. 642 F.2d 1285, 1293-94

(D.C. Cir. 1980). It would defeat the

entire purpose of Rule 24(a) if the find

ing of "inadequate representation" had

application only in the District Court.

The Government could, with impunity and

without explanation, simply defeat the

interests of the intervenor by acquiesc

ing in the views of its adversary through

"settlement," whether expressed in formal

terms or undertaken with the quiet pas

sage of the time beyond which it must

appeal. See Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc, v.

Watt. 713 F.2d 525, 528 (9th Cir. 1983).

The insidious nature of the

Court of Appeals determination also is

49

founded in the absence of an explanation

for the Government’s conduct. As this

Court is aware, the Record of Decision

was issued by the New England Division of

the U.S. ACOE; defending that decision in

litigation is not its responsibility.

The Justice Department's determination

not to appeal may have been premised on a

philosophical discomfort with the New

England Division's denial of a permit or

the political discomfort of being on the

"wrong side" in the Court of Appeals. It

also may have simply missed the jurisdic

tion deadline for filing a notice of ap

peal. Its motion to dismiss New Haven's

appeal in this case was made without ci

tations or legal argument. In fact, in

the 5 months the U.S. ACOE's motion was

pending, it was never requested by the

Court of Appeals — despite our insis

tence — to explain either why it was

made or what the effect would be if this

50

appeal proceeded. Nonetheless, the Court

of Appeals fashioned a rule denying an

intervenor from appealing based, in part,

on its own assumptions, or those ex

tracted from other cases, as to the Gov

ernment's motivation or the effect on New

Haven. In the end, it protected the U.S.

ACOE decision not to appeal, imposed

enormous litigation burdens on New Haven

(let alone on others who actively opposed

the issuance of the permit before the

U.S. ACOE) and radically altered the fac

tual and legal posture of the case, with

out any reasoning articulated by the

rule's primary beneficiary, the U.S. ACOE.

In any event, New Haven is en

titled to "all the prerogatives of a par

ty litigant" (United States v. AT&T. 642

F.2d at 1294), including the right to

appeal since, as is abundantly obvious

here, New Haven’s interests were "not

51

adequately represented in the decision

[by the U.S. ACOE] not to appeal." Id.

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of cer

tiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Neil T. Proto

Kelley Drye & Warren

Suite 600

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 463-8333

Brian Murphy

Corporation Counsel

City of New Haven

770 Chapel Street

New Haven, CT 06510

(203) 787-8232

July 5, 1988

52

ADDENDUM

ADDENDUM

STATUTORY PROVISIONS AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

1. Section 101(b)(5) of the National

Environmental Policy Act of 1969, 42

U.S.C. § 4331(b) provides in perti

nent part:

(b) In order to carry out the

policy set forth in this chapter

[42 U.S.C.S. §§ 4321 ei sea. 1 .

it is the continuing responsi

bility of the Federal Government

to use all practicable means,

consistent with other essential

considerations of national pol

icy, to improve and coordinate

Federal plans, functions, pro

grams, and - resources to the end

that the Nation may—

* * *

(5) achieve a balance between

population and resource use

which will permit high standards

of living an a wide sharing of

life's amenities; . . .

2. Section 102 of the National Environ

mental Policy Act of 1969, 42 U.S.C.

§ 4332, provides in pertinent part:

la

[Section 102(2)(C)]

The Congress authorizes and di

rects that, to the fullest ex

tent possible: (1) the poli

cies, regulations, and public

laws of the United States shall

be interpreted and administered

in accordance with the policies

set forth in this chapter [42

U.S.C. §§ 4321 seq. 1 . and (2)

all agencies of the Federal Government shall—

(C) include in every recommen

dation or report on proposals

for legislation and other major

Federal actions significantly

affecting the quality of the

human environment, a detailed

statement by the responsible official on—

(i) the environmental impact

of the proposed action,

(ii) any adverse environmental

effects which cannot be

avoided should the propos

al be implemented,

(iii) alternatives to the pro

posed action,

(iv) the relationship between

local short-term uses of

man’s environment and the

maintenance and enhance

ment of long-term productivity, and

(v) any irreversible and irre

trievable commitments of

resources which would be

involved in the proposed

action should it be implemented .

2a

Prior to making any detailed

statement, the responsible Fed

eral official shall consult with

and obtain the comments of any

Federal agency which has juris

diction by law or special exper

tise with respect to any envi

ronmental impact involved. Cop

ies of such statement and the

comments and views of the appro

priate Federal, State, and local

agencies, which are authorized

to develop and enforce environ

mental standards, shall be made

available to the President, the

Council on Environmental Quality

and to the public as provided by

section 552 of title 5, United

States Code [5 U.S.C.S. § 552],

and shall accompany the proposal

through the existing agency re

view processes;

3. Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors

Appropriation Act of 1899, 33 U.S.C.

§ 403, provides in pertinent part:

The creation of any obstruction

not affirmatively authorized by

Congress, to the navigable

capacity of any of the waters of

the United States is hereby pro

hibited; and it shall not be

lawful to build or commence the

building of any . . . structures

in any . . . navigable river, or

other water of the United

States, outside established har

bor lines, or where no harbor

3a

lines have been established,

except on plans recommended by

the Chief of Engineers and

authorized by the Secretary of

the Army; . . .

4. Section 404 of the Clean Water Act,

33 U.S.C. § 1344, provides in perti

nent part:

(a) Discharge into navigable

waters___at specified disposalsites. The Secretary may issue

permits, after notice and oppor

tunity for public hearings for

the discharge of dredged or fill

material into the navigable

waters at specified disposal sites. Not later than the fif

teenth day after the date an

applicant submits all the infor

mation required to complete an

application for a permit under

.this subsection, the Secretary

shall publish the notice re

quired by this subsection.

(b) Specification for disposal

sites. Subject to subsection

(c) of this section, each such

disposal site shall be specified

for each such permit by the Sec

retary (1) through the applica

tion of guidelines developed by

the Administrator, in conjunc

tion with the Secretary, which

guidelines shall be based upon

criteria comparable to the cri

teria applicable to the terri

torial seas, the contiguous

4a

zone, and the ocean under sec

tion 1343(c) of this title, and

(2) in any case where such

guidelines under clause (1)

alone would prohibit the speci

fication of a site, through the

application additionally of the

economic impact of the site on

navigation and anchorage.

* * *

(d) The term "Secretary" as

used in this section means the

Secretary of the Army, acting

through the Chief of Engineers.

5. The Administrative Procedure Act, 5

U.S.C. § 706(2)(A) provides in perti

nent part:

The reviewing court shall —

* * *

(2) hold unlawful and set aside

agency action, findings, and

conclusions found to be -

(A) arbitrary, capricious, an

abuse of discretion, or other

wise not in accordance with law;

* * *

(D) without observance of proce

dure required by law; . . .

6. 28 U.S.C. § 1291 provides:

The courts of appeals . . .

shall have jurisdiction of ap

peals from all final decisions

of the district courts . . .

5a

7. The "Public Interest Review" regula

tion of the Army Corps of Engineers,

33 C.F.R. § 320.4 (a) and (q), pro

vides :

(a) Public Interest Review. (1) The decision whether to issue a

permit will be based on an evaluation

of the probable impacts, including

cumulative impacts, of the proposed

activity and its intended use on the

public interest. Evaluation of the

probable impact which the proposed

activity may have on the public in

terest requires a careful weighing of

all those factors which become rele

vant in each particular case. The

benefits which reasonably may be ex

pected to accrue from the proposal

must be balanced against its reason

ably foreseeable detriments. The

decision whether to authorize a pro

posal, and if so, the conditions

under which it will be allowed to

occur, are therefore determined by

the outcome of this general balancing

process. That decision should re

flect the national concern for both

protection and utilization of impor

tant resources. All factors which

may be relevant to the proposal must

be considered including the cumula

tive effects thereof: among those

are conservation, economics, aesthe

tics, general environmental concerns,

wetlands, historic properties, fish

and wildlife values, flood hazards,

6a

floodplain values, land use, naviga

tion, shore erosion and accretion,

recreation, water supply and conser

vation, water quality, energy needs,

safety, food and fiber production,

mineral needs, considerations of

property ownership and, in general,

the needs and welfare of the people.

For activities involving 404 dis

charges, a permit will be denied if

the discharge that would be author

ized by such permit would not comply

with the Environmental Protection

Agency's 404(b)(1) guidelines. Sub

ject to the preceding sentence and

any other applicable guidelines and

criteria (See §§ 320.2 and 320.3), a

permit will be granted unless the

district engineer determines that it

would be contrary to the public in

terest .

(q) Economics. When private

enterprise makes application for

a permit, it will generally be

assumed that appropriate econom

ic evaluations have been com

pleted, the proposal is econom

ically viable, and is needed in

the marketplace. However, the

district engineer in appropriate

cases, may make an independent

review of the need for the pro

ject from the perspective of the

overall public interest. The

economic benefits of many pro

jects are important to the local

community and contribute to

needed improvements in the local

economic base, affecting such

factors as employment, tax

7a

revenues, community cohesion,

community services, and property

values. Many projects also con

tribute to the National Economic

Development (NED)(i.e., the

increase in the net value of the

national output of goods and

services).

8. The regulations of the Council on

Environmental Quality, 40 C.F.R.

§ 1502.16, 40 C.F.R. § 1508.7, 40

C.F.R. § 1508.8(a)(b), and 40 C.F.R.

§ 1508.14 provide:

§ 1502.16 Environmental conse

quences .

This section forms the

scientific and analytic basis

for the comparisons under

§ 1502.14. It shall .consolidate

the discussions of those ele

ments required by sections

102(2)(C)(i), (ii), (iv), and

(v) of NEPA which are within the

scope of the statement and as

much of section 102(2)(C)(iii)

as is necessary to support the

comparisons. The discussion

will include the environmental

impacts of the alternatives in

cluding the proposed action, any

adverse environmental effects

which cannot be avoided should

the proposal be implemented . . .

8a

(1502.16 (cont.))

It shall include discus

sions of:

(a) Direct effects and

their significance (§ 1508.8).

(b) Indirect effects and

their significance (§ 1508.8).

(c) Possible conflicts

between the proposed action and

the objectives of Federal,

regional, State, and local . . .

land use plans, policies and

controls for the area

concerned. (See § 1506.2(d).)

(d) The environmental ef

fects of alternatives including

the proposed action. . . .* * *

(g) Urban quality . . .

and the design of the built en

vironment, including the reuse

and conservation potential of

various alternatives and mitiga

tion measures.

§ 1508.7 Cumulative impact.

"Cumulative impact" is the

impact on the environment which

results from the incremental

impact of the action when added

to other past, present, and rea

sonably foreseeable future ac

tions regardless of what agency

(Federal or non-Federal) or per

son undertakes such other ac

tions. Cumulative impacts can

9a

result from individually minor

but collectively significant actions taking place over a

period of time.

§ 1508.8 Effects.

"Effects" include:

(a) Direct effects, which

are caused by the action and

occur at the same time and place.

(b) Indirect effects,

which are caused by the action

and are later in time or farther

removed in distance, but are

still reasonably foreseeable.

Indirect effects may include

growth inducing effects and

other effects related to induced

changes in the pattern of land

use, population density or

growth rate, and related effects

on air and water and other

natural systems, including eco

systems .

Effects and impacts as used in

these regulations are synony

mous. Effects include ecologi

cal (such as the effects on

natural resources and on the

components, structures, and

functioning of affected ecosys

tems), aesthetic, historic, cul

tural, economic, social, or

health, whether direct, indi

rect, or cumulative. Effects

may also include those resulting

from actions which may have both

10a

beneficial and detrimental ef

fects, even if on balance the

agency believes that the effect will be beneficial.

§ 1508.14 Human environment.

"Human environment" shall

be interpreted comprehensively

to include the natural and phys

ical environment and the rela

tionship of people with that

environment. (See the defini

tion of "effects" (§ 1508.8).)

This means that economic or so

cial effects are not intended by

themselves to require prepara

tion of an environmental impact

statement. When an environmen

tal impact statement is prepared

and economic or social and nat

ural or physical environmental

effects are interrelated, then

the environmental impact state

ment will discuss all of these

effects on the human environment.

9. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24(a)

provides:

(a) Intervention of Right.

Upon timely application anyone

shall be permitted to intervene

in an action: (1) when a stat

ute of the United States confers

an unconditional right to inter

vene; or (2) when the applicant

claims an interest relating to

the property or transaction

11a

which is the subject of the ac

tion and he is so situated that

the disposition of the action

may as a practical matter impair

or impede his ability to protect

that interest, unless the appli

cant's interest is adequately

represented by existing parties.

* * *

12a

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on July 5,

1988 I caused copies of the attached

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the

First Circuit and the Appendix thereto to

be served via first class mail, postage

prepaid, or by hand delivery ("*"), upon:

^Honorable Charles Fried

Solicitor General of the United States

United States Department of Justice

Room 5143

10th and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

Daniel Riesel, Esq.

Sive, Paget and Riesel, P.C.

10th Floor

460 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Alice Richmond, Esq.

Hemenway and Barnes

60 State Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

a

Peter Shelly, Esq.Conservation Law Foundation

of New England, Inc.

4 Joy Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

^Honorable Edwin Meese

Attorney General of the United States

United States Department of Justice

10th and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

James Tripp, Esq.

Environmental Defense Fund

257 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10010

Katherine H. Robinson, Esq.

Connecticut Fund for the Environment

32 Grand Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06106

Peter Steenland, Esq.

Appellate Section

Land and Natural Resources Division

Department of Justice

P. O. Box 23795 (L’Enfant Station)

Washington, D.C. 20026

Edward S. Lawson

Westin, Patrick, Willard and Redding

84 State Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

Roberta Friedman, Esq.

383 Orange Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06511

b

July-

Frank Cochran, Esq.

Cochran, Cooper, ei a_l

P. 0. Box 1898

New Haven, Connecticut

5, 1988

Neil T.

- c -

06508

V J- 7̂>

Proto