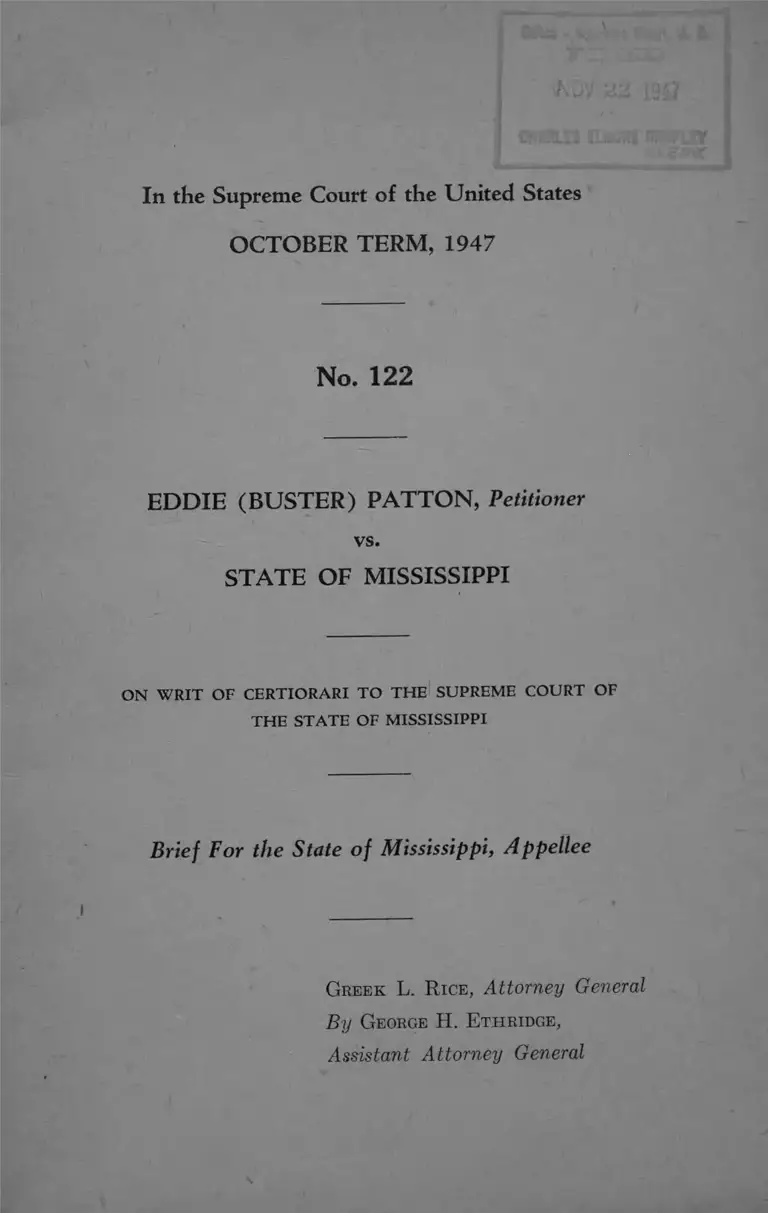

Patton v. Mississippi Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

October 29, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patton v. Mississippi Brief for Appellee, 1947. 86cb4fe9-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2e109e5b-387e-4070-8ff0-e49f51343444/patton-v-mississippi-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 122

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTO N , Petitioner

vs.

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

O N W R IT O F C E R T IO R A R I T O T H E SUPREM E C O U R T OF

T H E S T A T E O F M ISSISSIP P I

Brief For the State of Mississippi, Appellee

Greek L. R ice, Attorney General

By George H. Ethridge,

Assistant Attorney General

TABLE OF CASES CITED IN THIS BRIEF AND

PAGES WHERE FOUND

Page

Edgar Smith vs. State of Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 132, 85

L. Ed. 84............................................................ -.......... 38

Edna W. Ballard vs. U. S., 91 L. Ed. (Advance) 195....... 41

Farrow vs. State, 91 Miss. 509, 45 So. 619....................— 36

Gibson vs. State of Miss. 162 U. S. 567, 40 L. Ed. 1078.... 36

Hale vs. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613, 82 L. Ed. 1050 and

case note at 1053 L. Ed.............................................- 33

Lewis vs. State of Mississippi, 91 Miss. 505, 45 So. 360.... 35

Moon vs. State, 176 Miss. 72, 168 So. 476............. — ..... - 32

Norris vs. State of Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 55 S. Ct. 579,

79 L. Ed. 1074................................................................ 33

Pringle vs. State, 108 M. 802, 67 So. 455.......................... 46

Pearson vs. State, 176 Miss. 9, 167 So. 644..................32,43

Ransom vs. State, 149 Miss. 262, 115 So. 208.................. 50

Reynolds vs. State, 199 Miss. 409, 24 So. (2d) 781......... 31

Sauer vs. State, 166 Miss. 507; 144 So. 252....................... 50

Smith vs. State of Oklahoma, 140 Am. St. 688, 4 Okla.

Cr. Rep. 128 and case note in 140 Am. St. Rep., 688.. 34

Tollivar vs. State, 133 Miss. 789, 98 So. 342..................... 45

A

MISSISSIPPI CONSTITUTION OF 1890

Sections cited in this brief:

Section 264; Jurors must be registered and able to read

and write; page 23.

Text of Section 264 of Constitution, page 23.

Section 241, Constitution, text of page 24.

Section 242, Constitution, text of page 24, 25.

Section 243, Constitution, text of page 25.

Section 244, text of pages, Brief; 25.

Qualification of voter— Need not be able to read and

write, if he understands it or is able to give a reasonable

interpretation thereof;

Section 248, text of page 25—Remedy if registration is

denied by appeal to courts;

Section 26 referred to on page 44, 45 as to right to take

shoes after arrest, page 44, 45.

STATUTES CITED IN THE BRIEF

Code of 1942, Section 1762, who are qualified to serve as

jurors, page 4 to 26-27; Text of Section 1762;

Section 2505, Code of 1942, copy of special venire to be

served on defendant or counsel one entire day, page 6;

Section 3224, voter may appeal from a denial of the right

to register, page 25, 26;

Section 3228, appeal—May have bill of exceptions—pro

cedure, page 25, 26;

Section 1764, who is exempt from jury duty, page 27.

Section 1765, who is exempt from jury duty as a personal

privilege, page 27, Text of Section 1765, page 27;

Section 1766, list of jurors to be made up by board of

B

supervisors—men of sound judgment, good intelligence and

fair character, able to read and write, registered voters, etc.,

page 27;

Section 1767—Jury list—how many put in jury list and

jury box, page 28;

Section 1768—Certified copy of jury list to be given clerk

of board of supervisors and put in the jury boxes, page 29;

Section 1772—Judge to draw names of jurors at each

regular and special term of court, names of jurors to serve

at the next term, etc., page 29;

Section 1772, text of statute, page 29;

Section 1774, jurors, if not drawn at term, judge may

draw in vacation, page 29, 30;

Section 1777, sheriff to execute venire facias, page 30;

Section 1778, contempt of court not to perform jury duty,

page 30 ;

Section 1779, number of grand juries, how drawn, etc.,

page 30;

Section 1780, foreman of grand jury and oath taken, im

partiality, etc., page 30;

Section 1781, judge to charge grand jury, page 30;

Section 1794, procedure in case of insufficient jurors, non-

attendance, etc., the court’s power, etc., page 31;

Section 1794, full text of; page 31;

Section 1796, challenge to affay none except for fraud or

quashed, page 32;

Section 1798, jury laws directory, page 32.

C

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON

vs. No. 122

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

POINT I

The evidence is utterly insufficient to show that any race

discriminate was practiced in selecting jurors for jury serv

ice. It does not sufficiently appear that any registered

negro had the qualifications to vote.

Constitution of 1890, Section 264, 241, and 248.

Code of 1942, Sections 1762, 1764, and 1784 and 1789.

See testimony B. M. Stephens, printed record, pages 3

to 6; Addie Rivers, 6 to 12; Cicero Ferrill, 12 to 22; How

ard Cameron, 23 to 31; Judge J. A. Riddell, 48 to 53; George

Beeman, pages 54 to 57; Donovan Ready, 57 to 60; E. C.

Gunn, 63 to 67; L. D. Walker, 63 to 68; 0. L. King, 69 to 73;

William Wright, 74 to 79; Frank Kennedy, 80 to 84; W. Y.

Brame, 85 to 86; See this brief, pages 1 to 16.

D

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON

vs. No. 122

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

POINT II

The statements and confessions of the defendant to the

officers, and his pointing out articles taken from the de

ceased and from his store or place of business was free and

voluntary and the officer’s testimony in reference thereto

is not disputed. The defendant might have testified on the

objections thereto without testifying before the jury either

on the objection or on the merits. No testimony disputes

the officer’s testimony. See testimony of A. B. Ruffin,

86 to 129, printed record; Martin, page 129 to 133; A. B.

Ruffin, page 134 to 136; Martin Gunn, page 136; A. B.

Ruffin again recalled, 136 to 141. See this brief, page 44,

et. seq.

E

vs. No. 122

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

POINT III

The evidence shows overwhelmingly that the defendant

is guilty. See printed record, pages 86 to 141.

See this brief, page 45 to end.

Ranson v. State, 149 Miss. 262, 115 So. 208, p. 50.

Sauer v. State, 166 M. 507, 144 So. 225, p. 50.

Hardy v. State, 143 M. 353, 108 So. 227, p. 50.

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON

F

In the Supreme Court of the U nited States of A merica

1947-1948 TERM

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON, Appellant

vs. No. 122

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, Appellee

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

This is an appeal by certiorari from the judgment of the

Supreme Court of the State of Mississippi affirming the

death sentence for murder, by the appellant, of one Jim

Meadors which case originated in the circuit court of Lau

derdale County, Mississippi; there being a conviction on

an indictment in due and regular form for said murder be

fore a jury of the circuit court of Lauderdale County, Mis

sissippi, which resulted in a death sentence for the appellant,

from which he appealed to the Supreme Court of the State

of Mississippi, where the judgment of conviction was af

firmed. The opinion of the Mississippi Supreme Court

affirming said conviction appearing in the record for the

certiorari at page 227, et seq., abridged record, page 46, and

the judgment of affirmance was entered on the minutes of

said Supreme Court of Mississippi shown at page 237 (152

of abridged record) of the record. I will not make a detailed

statement of facts in the case, but will ask the court to read

the full record as I do not agree with many statements in

the brief for the appellant on the motion for certiorari, and

especially statements with reference to the confession made

to the officers of Lauderdale County, Mississippi. There

is no evidence in the record to contradict the testimony of

the officers as to its being free and voluntary, neither the

appellant, defendant in the court below, nor any other

witnesses introduced disputed any of the facts testified to

by the said deputy sheriffs, and others who testified on be

1

half of the State. The appellant chose not to testify al

though a competent witness; and could have testified on

or in the absence of the jury on the admissibility of the

confession. Neither did he testify on the merits at all. He

chose to be a silent party. It appears that Jim Meadors was

operating a place of business about four miles south of the

city of Meridian which was known, and spoken of, as a

night club by some of the witnesses. It appears that this

place of business was operatd from about 9 :00 or 10:00 A.M.

until about 10:00 P.M., and a young lady who testified in

the case worked in the said place in the day time but did not

work at night. On the morning following the killing of

Meadors, this lady went to the place of business to work

and found the dead body of Mr. Meadors in the store and

called for help, calling the sheriff’s office and also an under

taking establishment in Meridian. The deputy sheriffs

responded to this call and also an employee of the under

taking establishment went to the place of business of the

deceased to get the body to prepare it for burial, and they

testified as to the facts that they found which led to the

belief that the appellant was the killer. Without setting

forth the evidence as to the condition of the body of the

deceased, the finding of the peculiar tracks leading from

the place where the killing occurred, and to the investiga

tions made, I desire to say that the murder was one of

peculiar brutality and clearly connected the defendant with

the killing as the guilty agent. The original record from

the circuit court to the Mississippi Supreme Court is very

voluminous and it would consume quite a lot of space to

set forth the testimony in detail.

When the case was called for trial in the circuit court of

Lauderdale County, Mississippi, the defendant filed a mo

tion to quash the indictment which appears in the abridged

record for certiorari to the Supreme Court of the United

2

States on pages 2 and 3, and page 16 of the original record

from the circuit court of Lauderdale County to the Supreme

Court of Mississippi. This motion to quash contained three

grounds appearing on page 2 of the record for certiorari.

(1 ) . The defendant is a negro and has been indicted

by the Grand Jury during the present term of this

court for the murder of a white man, and that a large

percentage of the qualified electorate of the county

from which the jurors are selected is of the negro race,

and no member of this race was listed on the general

venire summoned for the first week of this court from

which the Grand Jury was drawn and empaneled, nor

on the venires for either of the other weeks of this court.

(This allegation is not sustained by the proof, which shows

very few negroes, if any, were qualified jurors.)

(2 ) . That the general venire or venires issued for

this term of court, from which the Grand and Petit

Juries were selected, did not contain the name or names

of a single member of said race qualified for jury

service.

(3 ) . That for a great number of years and especially

since 1935, and during the present term of court and

in making up the jury box from which jurors have

been selected, empanneled, and sworn, there has been

in this county a systematic, intentional, deliberate and

invariable practice on the part of administrative officers

to exclude negroes from the jury lists, jury boxes and

jury service, and that such practice has resulted and

does now result in the denial of the equal protection

of the laws to this defendant as guaranteed by the 14th

amendment to the U. S. Constitution.

Upon this motion, much testimony was taken, but there

was no definite showing as to how many negroes were regis

tered in Lauderdale County and how many were able to

read and write, nor how many of those who were registered

were of age for jury duty and how many were disqualified

for jury service under the laws hereafter referred to or how

3

many complied with the requirements for jury service under

section 1762 of the Mississippi Code of 1942 which reads as

follows:

“Every male citizen not under the age of twenty-one

years, who is a qualified elector and able to read and

write, has not been convicted of an infamous crime, or

the unlawful sale of intoxicating liquors within a period

of five years and who is not a common gambler or

habitual drunkard, is a competent juror; but no per

son who is or has been within twelve months the over

seer of a public road or road contractor shall be com

petent to serve as a grand juror. But the lack of any

such qualifications on the part of one or more jurors

shall not vitiate an indictment or verdict. However,

be it further provided that no talesman or tales juror

shall be qualified who has served as such tales juror or

talesman in the last preceding two years; and no juror

shall serve on any jury who has served as such for the

last preceding two years; and no juror shall serve on

any jury who has a case of his own pending in that

court; provided there are sufficient qualified jurors in

the district, and for trial at that term.”

Other statutes of the State of Mississippi bearing on

the qualifications will be referred to hereafter. After the

motion to quash had been heard and overruled, the de

fendant made a motion for a special venire which was sus

tained and a venire was summoned by the sheriff from the

qualified persons subject to jury duty and rendered to the

court. Whereupon, the appellant moved to quash this

special venire for several reasons, among which was that no

negroes were summoned on the special venire, by the sheriff,

and also because the names of the jurors were not drawn

from the jury box of the county which had been refilled

under provisions of law less than thirty days from the be

ginning of the trial. This motion was also overruled by the

court and the jury was empanneled and questioned at

length, and found to be fair and impartial by the trial court,

4

which holding was also affirmed by the Supreme Court of

the State of Mississippi. The substance of the proceedings

are set forth and the statutes are referred to and also court

decisions hereafter in this brief.

A large amount of testimony was taken upon this motion

in which the circuit clerk, the deputy circuit clerk, sheriff,

chancery clerk and five members of the board of supervisors

and other persons testimony was taken.

It appeared therefrom that a very few negroes had regis

tered as voters in the said county, and most of these who

had registered were either doctors, lawyers or teachers in

the public schools or those who were beyond sixty years of

age and were not required to serve as jurors.

The motion was overruled by the Court, and then a mo

tion for a special venire facias was made which appears on

page 18 of the record, which motion was sustained by the

Court. In the order sustaining the motion for a special

venire facias the Court recited as shown on page 26 of the

original record:

“And it appearing to the court that the jury box of

the county has been refilled by the supervisors less than

30 days ago: Because said jury box was exhausted.”

The Court thereupon directed the clerk of this court to

issue to the sheriff of the county a venire facias directing

the said sheriff to summon from the body of the county

one hundred persons qualified for jury service, summoning

twenty from each of the supervisors districts, the writ to be

returnable before the court on the 27th day of February,

1946, at 9:00 o’clock A.M., and that when same had been

executed, a certified copy thereof with the sheriff’s return

thereon showing upon whom the writ had been served and

upon whom not served, together with a certified copy of the

indictment in this case, be upon or delivered to the de

5

fendant or his counsel for one entire day before the trial as

required by Section 2505 of the Code of 1942.

The defendant duly excepted to the action of the Court

in ordering the said jurors summoned from the body of the

county instead of having them drawn from the jury box.

Prior to the filing of the motion for a special venire a

motion for change of venue was filed and heard.

These various orders and motions seem to have been

placed irregularly in the record instead of being placed in

consecutive order.

Considerable testimony was offered on the motion for

change of venue, and change of venue was denied; there

upon, the defendant, through his counsel, filed a motion to

quash the special venire so ordered and directed to be issued

from the county at large, in which motion four grounds are

set forth as reasons for quashing, the first ground being that

the sheriff did not draw, list or summon any member of the

colored race, although there are members of the colored race

qualified for jury service, and that the action of the sheriff

in reference thereto was in pursuance of a well defined and

invariable policy followed for years by administrative of

ficers in this county of excluding negroes from jury service

and discriminating against them in the selecting, drawing,

listing, and summoning of jurors, and thus denies to the

defendant the equal protection of the laws guaranteed to

him by the 14th amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and the laws of the Constitution of the State

of Mississippi.

The second ground was that the special venire was im

properly and wrongfully and illegally ordered drawn and

summoned from the body of the county instead of being

ordered drawn from the regular jury box of the county.

6

The third ground was that the writ of venire facias should

not have issued to the sheriff for service but that the court

should have appointed someone to serve it, or to be deliv

ered to the coroner or other officer designated by law for

service, because of the fact that the sheriff’s office, that is

his deputies, are interested in the conviction of this de

fendant and that they claim to have secured from him a

confession of his guilt.

The fourth ground was that the sheriff selected and listed

the names of persons he desired to summon under the writ

or a large part of them before the writ was issued and did

not go into the various beats and summon at random or

without predetermination the requisite number of persons

for jury duty.

A great deal of testimony was taken on the motion to

quash, as will appear hereafter, but at the end of the testi

mony the judge overruled the motion to quash.

The testimony on motion to quash the indictment and on

the ground of the motion to quash the special venire based

upon the failure to have negroes placed in the jury box from

which juries are drawn, made up and empanneled.

It appears that after the Court had appointed Honorable

T. J. McDonald and L. J. Broadway to defend the appellant

that the defendant, by some means, secured the employ

ment of Mr. Broadway as a hired attorney; and after the

request of this attorney, Mr. McDonald was relieved from

further participation in the trial, but Mr. McDonald had

participated in the motion to quash the indictment and to

quash the special venire and in the motion for the change of

venue.

It appears from the voluminous testimony on the motion

to quash the indictment and the motion to quash the special

7

venire that there were very few negroes registered which is

required by Section 264 of the Constitution; and, conse

quently, there were extremely few negroes who could

qualify as jurors, and the circuit clerk estimated the num

ber of male negroes possibly qualified for jury service at

twenty-five, there being in his estimate only fifty qualified

negro voters in the county, who had paid their poll taxes

and were thus qualified, at fifty, one-half of which he

thought were women voters, and the other twenty-five be

ing largely composed of negroes who were teachers in public

schools, physicians, lawyers or otherwise excusable from

jury service, and who would not likely be put in the jury box

because of the expense of summoning as jurors those who

have the right to be excused, and thus they were omitted

from the jury lists and jury boxes in order to save expenses.

The testimony further shows there were from 9,000 to

12,000 voters in Lauderdale County altogether from which,

excluding negroes, would leave from 9,000 to 11,050 white

registered voters, approximately one-half of which would

be women.

T he Evidence on M otion to Quash

The first witness introduced on the motion to quash the

indictment was B. M. Stephens, who was connected with

the City Identification Bureau and a resident of the city of

Meridian who had formerly been sheriff for four years be

ginning in 1932 and had been a supervisor for eight years

of District 3 in said county beginning in 1924.

He testified that during his term as supervisor there were

no registered negro voters qualified for jury service in that

district.

Another witness (Mr. King) who is now a supervisor

serving his second term in that district testified that there

8

was only one negro registered voter in said district, and that

this negro voter was a medical doctor; and, consequently,

he could not be required to serve on the jury. He also tes

tified that during his term of services as supervisor and

sheriff that he had not observed any negro jurors serving

in the Circuit Court. He testified that during his official

term he was required to attend the Circuit Court and hear

the Circuit Judge charge the Grand Jury, and that he did

not think any negroes had served on the jury.

Mrs. Addie Rivers, Deputy Circuit Clerk, testified on

the motion that she had been such deputy since 1942, and

that she had charge of or access to the registration books of

voters every day in the week; that she had never checked

the books to see how many negroes were registered, and

that sometime during her services Mr. Ferrill, the Circuit

Clerk, had been requested by someone making up Federal

juries to get such person some colored qualified electors,

and that they only checked boxes in District 1 in which the

city of Meridian is situated and principally inside the city,

and that they found eight qualified negro jurors in that dis

trict; that they did not check all the precincts, but con

formed to the request of the Federal authorities to get eight

or ten negroes qualified for jury service.

She testified further that she had not registered the

colored voters who were registered; that Mr. Ferrill had

that authority, and that they had never registered a negro

without checking the color but that she had not registered

any.

Mr. Ferrill, the Circuit Clerk, was introduced on the mo

tion, and his testimony begins on page 58 of the record.

He became Circuit Clerk on the 20th day of January, 1943,

beginning by serving an unexpired term of Mr. Bledsoe, who

had died, and that he was since re-elected Circuit Clerk;

9

that he attended the Circuit Court at each term of the

Criminal Court to hear the judge’s charge to the Grand

Jury, and that he did not recall any negroes serving on the

Grand or Petit Juries; that prior to his appointment to fill

the vacancy mentioned, he had been a Deputy Chancery

Clerk; that when the board of supervisors made up their

lists of jurors which were to serve in the Circuit Court it

was a custom of the Chancery Clerk’s office to turn the list

over furnished by the board to one of the stenographers to

have entered on the minutes, and they did not pay particular

attention to the names so furnished by the board of super

visors, and that he did not know whether any negroes were

placed on the lists by the members of the board of super

visors, but that he does not remember any negroes serving

on the jury during the times he was either Deputy Chancery

Clerk or Circuit Clerk.

He testified further that it was the custom of the mem

bers of the board of supervisors in making up the lists of

jurors to check the registration and poll books, the poll

books being principally used because the poll books showed

not only the same persons registered upon the registration

books but also showed whether the voter had paid his poll

taxes in time to qualify him as an elector; that he did not

know whether any negroes had been drawn during this

period or not; that he did not know who was put in the

boxes, but that he had never seen a negro serving on the

jury. He also testified with reference to the request from

Federal authorities for some negro registered voters in

Lauderdale County; that it was the custom of the Federal

authorities to put a few negro electors in the lists of jurors

selected for the Federal Court, Meridian being one place

where the Federal Court was held.

He also further testified that there were forty-nine voting

precincts in the whole county, and that in District 1, in

10

which Meridian is situated, there were five voting precincts

in the territory outside the City of Meridian. The Circuit

Clerk states that he doesn’t think there were over fifty

negro qualified electors, but he had never checked to ascer

tain definitely, and that most of the negro registered voters

that he knows were either preachers or teachers in the public

schools or persons over sixty years of age.

It appears also from the testimony that the jury box filled

at the April meeting of the board of supervisors became

exhausted, and that the box was refilled.

Mr. Howard Cameron, the chancery clerk, testified that

he had been chancery clerk since January, 1936, and prior

to that time he was deputy chancery clerk beginning in

April 1933. He testified that the members of the board of

supervisors each go into the circuit clerk’s office and there

secure a registration roll from the circuit clerk and from

this roll they prepare a list of jurors in their respective dis

tricts and after the list is prepared it is then turned over to

the chancery clerk, and the chancery clerk has it copied and

entered on the minutes of the board of supervisors which

they then compile and certify a copy of this list and trans

mit it to the circuit clerk.

He was then asked if he had a very clear judgment of the

number of qualified electors in the county and stated that

he had his own opinion, but had been rudely shocked on

several occasions; that it was a strictly personal opinion;

that it was a hard thing to say how many registered voters

were in the county, but he thinks there were between 8,000

and 10,000, but he did not know definitely.

He was then asked as to the number of registered voters

of the negro race who were qualified electors in the county

and said:

11

“When you say qualified electors, I presume you

mean those who are registered and those who have paid

their poll taxes; also those whom the supervisors feel

are competent from the standpoint of being unbiased

and fair-minded?”

When he was asked to give an estimate of the number

of the negro race registered as voters, he said:

“Frankly, I have never given it any consideration,

but I am of the opinion that there are several hundred

of them.”

He testified further that he had never made an investi

gation at all, but that he did know for a fact that there were

negroes on the registration rolls and that he did know for a

fact that there had been negroes to vote in Lauderdale

County.

His testimony taken altogether shows that he had no

definite knowledge as to the number of the negro race regis

tered as voters and had never made any investigation along

that line.

He further testified that he attended the criminal court

to hear the judge charge the Grand Jury, and he never re

members to have seen a negro serving on the Grand or Petit

Juries.

Mr. W. Y. Brame, sheriff of the county, testified on the

motion the same as to negro jurors or registered voters, and

had no definite or clear judment about the matter, but

thought there might be forty or fifty negro voters in the

county.

He testified that the board of supervisors in making up

the jury lists frequently checked the books in his office to

see if people had paid their taxes after finding their names

on the registration books; that the usual practice was to

take the poll books rather than the registration books, the

12

poll books being duplicates of the registered voters and con

taining additional information as to whether poll taxes had

been paid by the 1st day of February.

The sheriff is required to make up lists of those who have

not paid by February 1st and keep them as a record for the

use of the election commissioners in revising poll books to

see who are qualified electors.

The examination of all these witnesses is quite prolix and

it is exceedingly difficult to state briefly and accurately the

full purport of their testimony.

Mr. Tom Johnson, a member of the board of supervisors

of District 2 of the county, testified on the motion. He

testified that he had served as a member of the board of

supervisors continuously since 1928, and had been out some

years prior to that, the first term beginning in 1904. He

testified that he made a search of the registration books in

making up a jury list, and he didn’t remember of a single

negro voter in his district; that he searches the books every

time the jury list is made up because the law requires that,

and he didn’t recall any negro voters at the time the last

jury box was made up about thirty days before the witness

testified. He also testified that he attended the Circuit

Court to hear the judge’s charge to the grand jury and

public officers and didn’t remember seeing any negro jurors

empanneled and serving at any of the terms of court. He

testified that there were five hundred or six hundred voters

in his district; that in making up his list he had never had

it in mind with reference to negro voters because he did not

have any darkies of consequence in his beat, and had

enough trouble going through the registered voters who

were qualified in making up his jury lists; that in making

up the jury list he tried to find men who have good intelli

gence, fair character and sound judgment; and that there

13

are naturally a lot of men in his district who have never

served on juries.

Judge J. A. Riddell, of the Lauderdale County Court,

testified that he had been, prior to his election as county

judge, practicing law since 1931 but had a license to practice

since 1916 but had served for twelve years as county super

intendent of education of this county and one term in the

State legislature and about sixty days as county prosecuting

attorney; that he had attended the circuit court at the

criminal terms to hear the judge charge the grand jury in

Lauderdale County during all this time mentioned; that he

didn’t know of any negroes who had been called from the

box and sought to be qualified or who had been qualified

and taken as a member of the Grand Jury in Lauderdale

County; that he had attended the circuit court more than

the average person because since 1916 he had a license to

practice and had some business in the courts and was inter

ested in the courts; and that he had not seen any negroes

serving on the juries.

Various other witnesses were called and the general effect

of all their testimony is that there were very few qualified

negroes capable of serving on Grand or Petit Juries, and

that no one had seen such negroes serving on juries during

such time as they testified about.

To sum up the testimony in a nut shell, it appears that

there were from 9,000 to 12,000 registered voters in Lauder

dale County, and not more than about sixty negroes regis

tered who had paid their poll taxes and thus qualified to

vote. It is not shawm in this record how many of these

registered negroes can read and write, so as to qualify as

jurors for under section 244 of the Constitution of Missis

sippi any person can register and vote although unable to

read and write, if he can understand it when read to him or

14

give a reasonable interpretation of it when it is read to him.

Under section 24S of the Constitution, he may appeal if im

properly denied registration, and may appeal through all

the courts including the U. S. Supreme Court. There is

not a word of testimony showing that any negro applied to

the circuit clerk for registration as a voter and had been re

fused registration when qualified by law to vote, the negro

generally being indifferent to voting.

The circuit clerk was called as a witness, as above stated,

but he was not interrogated about how many negroes sought

to register and how many had been refused registration,

if any at all.

I desire to call the Court’s attention to the testimony of

Mr. Donovan Ready, page 57 of the abridged record. This

witness is a public accountant, and had been employed by

the board of supervisors to check the qualifications of voters

for the years 1941 and 1942, at which time there was a con

test as to whether the Wine and Beer Law, prohibiting sales

of wine and beer in Lauderdale County had been carried in

an election for that purpose. He made this check in 1944

to cover that period, and made a very careful and pains

taking investigation to report to the board of supervisors on

the said matter. He could not tell exactly how many negroes

were registered or voted for that purpose, but thinks there

were somewhere around thirty-five or forty, possibly be

tween fifty and sixty, that he would say between thirty and

sixty colored electors were qualified at that time. He tes

tified that they were registered and had paid their poll

taxes in the period required to be qualified, and at that

time the largest part of them were preachers and school

teachers so far as he knew about these voters’ occupations.

He could not tell how many were under sixty years of age;

that he thought a great many were over sixty. Some were,

15

but not many; that he knew most of them and that is why

he knew they were colored, stating:

“ They don’t indicate on the record that they were

colored, but they were mostly colored preachers, as I

say, and colored teachers and they were middle age on

the average. There were some probably over sixty, but

I wouldn’t say a great number of them were.”

He further testified that they were predominantly preach

ers and teachers who were the better educated negroes of

the county, and that better than half of them were preach

ers.

The District Attorney also examined many of the wit

nesses as to the motion for a change of venue, and the proof

was overwhelming that there was no pre-judgment of the

case by the mass of people of the county. The same thing

was shown in the examination of the witnesses on the mo

tion to quash the special venire. From all the testimony in

the case it is manifest that the defendant could get as fair

a trial in Lauderdale County as in any other county in the

state.

Facts Concerning the T rial on the M erits

The deceased, Mr. J. L. Meadors, was operating a club or

place of business about four miles south of the city of Me

ridian on Highway 45. He was about fifty years of age,

and was last seen alive by his wife about six o’clock in the

morning which he was killed. Somewhere near 11: 00 o’clock

that morning, Mrs. J. L. Taylor, a witness for the state who

worked for the deceased and was his sister-in-law, went to

the store to resume her work there and found the body of

the deceased lying on the floor of the club or store dead.

She did not know how long he had been dead. She knew

the defendant, who had formerly worked for Mr. Meadors

but who had quit about two weeks before.

16

When she found the body, she called the sheriff’s office

and she then called the Williams Funeral Home, telling

them of the finding of the body, and they came out about

11:00 o’clock—in other words, as soon as they were notified

and as soon as they could get there, and the body was re

moved to the Williams Funeral Home.

She testified as to the bloody condition of Mr. Meadors’

head and face and blood around the body, the head of the

body being somewhat under the corner of the counter, and

she described the position of the body.

She also identified a lunch box belonging to Mr. Meadors

in which he kept the money taken in the business which he

carried with him when he left the business to go to his

home.

She also identified the hammer used in the place of busi

ness of Mr. Meadors for breaking coal, and with which the

proof shows the deceased had been beaten by someone, the

hammer being principally used for breaking coal for the

heater.

She also identified a hat found in the store or club on the

morning after the body was discovered which belonged to

the appellant, and identified the defendant stating that

they called him Buster instead of Eddie.

This witness did not work at night, and usually came to

work there about 10:30, but did not go on the morning in

question until around 11:00 o’clock, and described the

scene as best she could about the body. The record shows

this witness was deeply affected, and had to pause at times

before she could resume her testimony, stating she was very

nervous.

Mr. J. A. Stroud was called for the State. He works for

the Williams Funeral Home as an embalmer, and handled

the body of the deceased, Mr. Meadors.

17

He identified the clothing that the deceased had on which

was introduced in evidence and described the condition of

the clothing.

He examined the body for wounds, and stated that the

body was bruised and beaten, his head being very badly

beaten. He testified that he had gashes and cuts all over

his head and face; that there were fifteen from the neck up,

running from one inch to one and one-half inches from the

base of his neck to the top of his head; that there were a

couple of scratches on the face running from an inch to an

inch and one-half to two inches in length; and that ones on

the top of his head went very deep.

The state next introduced Mr. A. B. Ruffin, deputy

sheriff of Lauderdale County.

He testified that on the 11th day of February, 1946, he

had a call to make an investigation as to the dead body that

was found at Rock Hill, which body was Mr. Jim Meadors;

that he reached there about 11:00 o’clock; that he went in

response to a telephone call from Mrs. Taylor; that Russell

Danner and he went out there; that when they drove up to

the front the ambulance had just driven up ahead of them;

that he, Russell Danner and the two boys who worked with

the ambulance walked inside and found that the place was

terribly torn up. That a lot of broken bottles and things

like that were there and blood was all over the place; that

they found Mr. Meadors with his head lying partly under

neath the counter on top of a case of Seven-Up bottles,

partly filled; and he described the surroundings of the

body, etc.

He testified that he called the coroner and held an in

quest, and during the time they were searching the place for

evidence of anything that would lead to the reason for the

18

killing, or for clues, and that they searched the place pretty

thoroughly.

He found a hat underneath the ice box and testified that

the long ice box was made into the counter. The hat which

they found underneath the ice box was identified in the evi

dence as belonging to the defendant. They searched inside

the building for the money and did not find it nor did they

find the tin box which was introduced in evidence and

called a lunch box, which proof shows Meadors had and

which afterwards was found in the custody of the defendant.

He testified that they searched on the outside of the build

ing, and found some tracks; that whoever made the tracks

was running, and that the tracks were a long distance apart,

the distance between the tracks being estimated at about

five feet; that they wrere suspicious looking; and that these

tracks were what they found first.

He testified further that the tracks seemed to make more

pressure on the toes, and that casts were made of these

tracks; that one of the heels in the tracks was run over,

what is known as a run-over heel; that this run-over heel

was on the right foot; that he also made a cast of the left

foot which was introduced as evidence.

He further testified that later in the day the defendant

was arrested; that at the time he was arrested the shoes were

taken off of him, and he "was wearing a pair of shoes with a

part of the heel on the right shoe with a soft part in the

center, which was indicated in the cast.

He testified further that the left shoe did not have any

heel at all and had a rough, soft rubber sole.

The defendant then made objection that this testimony

was a violation of sections 23 and 26 of the Mississippi Con

stitution ; that if the officers took the shoes from this man,

19

and he testified that they did, no comparison could be made

with the case or no evidence made to show that they were

made by one and the same tracks until its admissibility is

properly determined, which objection was overruled.

Mr. Ruffin, the deputy sheriff, testified that he had found

a hat belonging to the defendant in the night club or store

under the ice box; that he did not know at the time whose

hat it was, and spent some little time asking people as to

whom the hat belonged, and finally learned that it belonged

to the defendant.

He saw the tracks, as indicated above, and their peculari-

ties and had casts made of these tracks which appeared to be

running as above stated. On this information he had reason

to believe that the appellant was then guilty, and they ar

rested the appellant and took the shoes from his feet and

tested them and placed them in the cast and they fit the

cast exactly.

Witnesses describing the peculiarities of the shoes and of

the tracks and the casts made together with the information

as to the hat belonging to the defendant was sufficient to

justify the appellant’s arrest and were reasonable grounds

to believe that he had committted the felony.

The appellant, under questioning by the officers, ad

mitted the hat belonged to him and made a full and com

plete confession as to the killing and the incidents of the

killing and the methods used in the killing.

The appellant, then, after questioning, carried the officers

to a place about half a mile northwest of the place of the

killing and showed them clothes hidden in a pine top or

brush heap which was the coat of deceased in which was

wrapped some other garments of the deceased and also the

lunch box described in the evidence which the deceased had

used as a container for his money while at his place of busi

20

ness and conveying it to his home for safekeeping at night,

and in this lunch box were some other little articles described

by the witness.

Another deputy carried the appellant to the place where

the clothes were pointed out, and the testimony showed that

this confession was not induced by threats or promises or

hope of reward, and was clearly admissible.

The appellant also carried the officers to another point,

some distance from where the clothes were found, where the

money was hidden, and he confessed that he had secreted

the money at that place, and that he had taken it from the

place of the deceased at the time of the killing.

The defendant confessed to the officers in detail as to the

means and methods of the killing which showed it to be a

brutal and unprovoked murder.

On the night of the killing, the appellant carried the shirt

and pants to a dry cleaner in the city of Meridian to have

them dry cleaned and pressed, and the pants had indica

tions of blood on them, and in the pants pocket was a ticket

with appellant’s name on it which showed the pants and

shirt were to be delivered on Tuesday, the day following

the placing of them in the dry cleaning establishment for

cleaning and pressing.

The appellant had on clothes that were fresh when he

was arrested, and stated to the officers that he had just

changed clothes Monday night after the pants and shirt had

been left for cleaning and pressing. The officers had gotten

this information by the confession of the appellant or by

his statement in answer to questions, and they called the

owner of the pressing shop to come down to the shop so they

could get the clothing which the appellant had left there.

This was after the closing hour of the shop, and the owner

21

of it left his home and went to the shop and delivered the

pants and shirt to the officers, who were deputy sheriffs,

and these were introduced in evidence.

There was a great deal of testimony introduced, and the

defendant did not testify at all either on the preliminary

objection to the admission of his confession and the state

ments made by the appellant and the production of the

articles in Court and the introduction of them in evidence

although the defendant had opportunity should he have

desired to testify to any facts that might have existed in

ducing the confession when that was offered in evidence

without testifying if he did not want to testify on the merits.

In other words, the testimony of the officers, as shown, is

utterly without dispute. There is, therefore, nothing doubt

ful about the appellant’s guilt of the murder and of his doing

the things testified to by the officers.

A person has a perfect legal right to testify in his own

behalf should he desire to do so or he has a right to remain

silent and stand on the State’s evidence, but if he exercises

this latter right, then the jury is entitled to draw every

reasonable conclusion that the evidence warrants; and,

therefore, the evidence should be accepted as being true

unless it is inherently improbable or false. Such is not the

case in the evidence involved here.

Argument

I submit that there are many facts in the original volumi

nous record that are not set forth in this Statement of

Facts.

The first point in the argument of the appellant is that

the lower court erred in overruling the appellant’s motion

to quash the indictment against him on the ground of sys

tematic exclusion of qualified negroes from jury service,

22

and in so ruling, denied to the appellant his rights of due

process of law and equal protection of the laws granted him

by the State Constitution and the 14th amendment of the

Constitution of the United States. In other words, the

appellant, seriously argues the exclusion of negroes from the

jury box and the special venire selected by the Sheriff.

This argument should not have been injected into this

case on the facts contained in this record and under the laws

of the State. I say this with due regard and friendship for

the attorneys for the appellant who injected this question

into this record, and do not doubt that they felt called upon

to do so, and did so out of a regard for what they thought

they should do in this case. Nevertheless, there was no

probability at all that under Section 2464 of the Constitu

tion negro jurors could be obtained under any reasonable

method of drawing the jury in this case.

The record shows that there were some 9,000 to 12,000

registered voters in Lauderdale County and that only from

30 to 60 of these were negroes qualified to vote; but no

showing was made as to how many could read or write as

required by Section 264 of the Constitution and the major

part of the negroes who were registered were not subject

to jury duty under the laws of the State, being either over

age or excusable for other reasons and could not be com

pelled to serve had they been singled out and summoned.

I desire, before going into the authorities on this proposi

tion, to call attention to some provisions of the Constitution

and the laws of this state. The State, of course, has the

right to say what qualifications jurors shall have to admin

ister the high trust involved in jury duty.

Section 264 of the State Constitution reads as follows:

“No person shall be a grand or petit juror unless

qualified elector and able to read and write; but the

23

want of any such qualification in any juror shall not

vitiate any indictment or verdict. The legislature shall

provide by law for procuring a list of persons so quali

fied, and the drawing therefrom of grand and petit

jurors for each term of the circuit court.”

There is no legal method of compelling any person to

register or vote or to qualify for jury service under this

section of the Constitution. The term in the above section

“ unless a qualified elector and able to read and write” is to

be construed in connection with the provisions on the fran

chise contained in article 12 of the Constitution and par

ticularly with reference to Sections 241, 242. 243 and 244

of the Mississippi Constitution.

In section 241 of the Constitution, it is provided:

“ Every inhabitant of this state, except idiots, insane

persons, and Indians not taxed, who is a citizen of the

United States, twenty-one years old and upwards, who

has resided in this state for two years, and one year in

the election district, or in the incorporated city or town

in which he offers to vote, and wrho is duly registered,

as provided in this article, and who has never been

convicted of bribery, theft, arson, obtaining money or

goods under false pretense, perjury, forgery, embezzle

ment or bigamy and who has paid on or before the first

day of February of the year in which he shall offer to

vote, all poll taxes which may have been legally re

quired of him and which he has had an opportunity of

paying according to law, for the two preceding years,

and who shall produce to the officers holding the elec

tion satisfactory evidence that he has paid such taxes,

is declared to be a qualified elector; but any minister

of the gospel in charge of an organized church shall be

entitled to vote after six months’ residence in the elec

tion district, if otherwise qualified.”

Under Section 242 of the Constitution of Mississippi it is

provided:

“ The legislature shall provide by law for the regis

tration of all persons entitled to vote at any election.”

24

It cites further the oath that parties securing registra

tion must take, in which oath he must swear that he is

not disqualified for voting by reason of having been

convicted of any crime named in the Constitution as a

disqualification to be an elector, and that he will an

swer truthfully all questions pertaining to the right to

register and vote.

Section 243 provides for:

“A uniform poll tax of two dollars, to be used in aid

of common schools, and for no other purpose, is hereby

imposed on every inhabitant of this state, male or fe

male*, between the ages of twenty-one and sixty years,

except persons who are deaf and dumb, or blind, or who

are maimed by loss of hand or foot, etc.”

Section 244 provides that:

“ On and after the first day of January, 1892, every

elector shall, in addition to the foregoing qualifications,

be able to read any section of the Constitution of this

state; or he shall be able to understand the same when

read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation thereof.

A new registration shall be made before the next en

suing election after January the first, 1892.”

Section 248 of the Constitution provides for an appeal

from a refusal of registration, and has an important bearing

on the question involved in the first Assignment of Error

argued by the appellant. The section reads as follows:

“ Suitable remedies by appeal or otherwise shall be

provided by law, to correct illegal or improper regis

tration and to secure the elective franchise to those

who may be illegally or improperly denied the same.”

The Legislature has provided this method of appeal, and

every voter has the right to appeal the registrar’s decision

denying him to right to vote and have a judicial hearing

thereon, and this right he may exercise to the utmost limit

*The word female was not in the original Constitution but was inserted

after the adoption o f woman suffrage.

25

by appealing to every court including the Supreme Court

of the United States. See Code of 1942, Section 3224, and

3228.

As stated in the beginning of this brief, there is no proof

whatever that any negro was denied the right to register or

to vote in Lauderdale County.

The Circuit Clerk is the registrar under the law, and

from his refusal an appeal may be taken to the circuit court

and from thence to the State Supreme Court and from

thence to the United States Supreme Court. This being

true, the officers in making up the jury lists did not have

more than one-half of one per cent of the registered voters

to select any negroes from, and the law does not require any

particular person to be selected for jury service from the

lists of registered voters of the county.

Mississippi has never authorized women to sit on juries,

and the record shows that approximately fifty per cent of

the voters who are registered are women.

I will now refer to some of the statutes involved to show

that the application to quash the indictment and to quash

the special venire are utterly without merit, and should not

be raised in this case, because there is no showing in the

record that there was any qualified negroes under Section

1762 of Mississippi Code 1942. There may be cases, and

no doubt are, where counsel should raise the question for

the protection of his client, and I would not criticize the

raising of the question in some cases where there was a

probability of securing classes of persons who were not on

the jury lists or in the jury box.

Section 1762 of the Code of 1942 provides that:

“Every male citzen not under the age of twenty-one

years, who is a qualified elector and able to read and

26

write, has not been convicted of an infamous crime,

or the unlawful sale of intoxicating liquors within a

period of five years, and who is not a common gambler

or habitual drunkard, is a competent juror; but no

person who is or has been within twelve months the

overseer of a public road or road contractor shall be

competent to serve as a grand juror. But the lack of

any such qualifications on the part of one or more

jurors shall not vitiate an indictment or verdict.”

It also provides for talesmen of a jury, etc., which is not

pertinent here.

Section 1764 provides who shall be exempt from jury duty,

and includes all physicians, osteopaths and dentists actually

in practice, all teachers and officers of public schools and

locomotive engineers actually engaged in their vocation;

and a large number of other persons including all ministers

of the gospel and Jewish rabbis actually engaged in their

calling, all officers of the Government of the United States,

all lawyers practicing their profession, and others numerous

in said section.

Section 1765 provides who are exempt as a personal

privilege, and reads as folows:

“Every citizen over sixty years of age, and everyone

who has served on the regular panel within two years,

shall be exempt from service, if he claims the privilege;

but the later class shall serve as talesmen and on special

venire, and on the regular panel, if there be a deficiency

of jurors.” (Emphasis added.)

Section 1766 provides for the making of the list of jurors

by the board of supervisors at the April meeting of each year

or at a subsequent meeting if not done at the April meet

ing, and they shall select and make a list of persons to serve

' as jurors in the Circuit Court for the twelve months be

ginning more than thirty days afterwards, and provides

that as a guide in making this list they shall use the regis-

27

tration book of voters, and shall select and list the names

of qualified persons of good intelligence, sound judgment,

and fair character, and that they shall take them as nearly

as they conveniently can, from the several supervisor’s dis

tricts in proportion to the number of qualified persons in

each, excluding all who have served on the regular panel

within two years. It also provides that the Clerk of the

Circuit Court shall put the names from each supervisor’s

districts in a separate box or compartment, kept for the

purpose, which shall be locked and kept closed and sealed,

except when juries are drawn. It also provides that the

board of supervisors shall cause the jury box to be emptied

of all names therein, and the same to be refilled from the

jury list as made by them at said meeting. It then pro

vides if the jury box shall at any time be so exhausted of

names as that a jury cannot be drawn as provided by law,

then the board of supervisors may at any regular meeting

make a new list of jurors in the manner herein provided.

It is then made the duty of the Circuit Clerk and the

registrar of the voters to certify to the board of supervisors

during the month of March of each year under the seal of

his office the number of qualified electors in each of the

several districts in the county.

In the present case the box, as made up at the April term,

became exhausted during the year, and was refilled less than

thirty days before the time of the drawing of the special

venire and empaneling of the Grand jury.

The list of jurors made up under this chapter does not

require the listing of every voter as a juror, but limits the

number that may be listed in such list unless there be a de

ficiency of jurors in which case the court may order a greater

or less number to be listed. (Section 1767.)

28

Section 1768 provides:

“A certified copy of the lists shall be immediately

delivered by the clerk of the board of supervisors to the

clerk of the circuit court, and shall be by him carefully

filed and preserved as a record of his office; and any

alteration thereof shall be treated and punished as pro

vided in case of the alteration of a record.”

As already stated, the county contained from 9,000 to

12,000 registered voters. The law limits the number that

could be selected, and no more than eight hundred can be

put on the list unless ordered by the Circuit Court because

of the reasons mentioned.

Section 1772 of the Code provides:

“At each regular term of the circuit court, and at a

special term if necessary, the judge shall draw, in open

court, from the five small boxes enclosed in the jury

box, slips containing the names of sixty-two jurors to

serve as grand and petit jurors for the first week and

thirty-six to serve as petit jurors for each subsequent

week of the next succeeding term of the court, drawing

the same number of slips from each and every one of

the five small boxes if practicable, and he shall make

and carefully preserve separate lists of the names, and

shall not disclose the name of any juror so drawn; but

only thirty-six names shall be drawn for each week or

any term where a grand jury is not to be drawn. The

slips containing the names so drawn shall be placed by

the judge in envelopes, a separate one for each week,

and he shall securely seal and deliver them to the clerk

of the court, so marked as to indicate which contains

the names of the jurors for the first and each subse

quent week. If in drawing it appears that any juror

drawn has died, removed or ceased to be qualified or

liable to serve as a juror, the judge shall cause the slip

containing the name to be destroyed, the name to be

stricken from the jury list, and he shall draw another

name to complete the required number.”

Section 1774 provides if this is not done in term that the

29

judge may draw them in vacation, if convenient; and if he

does not, and whenever jurors are required for a special term

and the judge shall so direct, the clerks of the circuit and

chancery courts and the sheriff shall, at the time they should

have opened the envelopes, draw the jurors for the term of

court, and make and certify the lists thereof; and the clerk

shall issue and deliver to the sheriff the proper venire facias.

Section 1777 of the Code provides that the sheriff shall

forthwith execute the venire facias by summoning each

juror at least five days before the first day of court either

by personal service or by leaving a written notice at his

usual place of abode; and he shall make return of the venire

on the first day of the term, and this section provides for

fining of jurors if they do not attend as commanded unless

they show good cause.

By Section 1778 it is made a contempt of court not to

perform the duties as to juries when so listed and summoned.

Section 1779 provides that the number of grand jurors

shall not be less than fifteen nor more than twenty, in the

discretion of the court; and that they shall be drawn from

the list of persons in attendance as jurors on a separate slip

of paper, and the names from each supervisor’s district shall

be placed in a separate box or compartment, in open court,

and shall be drawn out by the person designated by the

judge, the number directed by the court; and said names

shall be drawn from each box in regular order until the

number designated is drawn, and the jurors whose names

are so drawn shall constitute the grand jury, and be em

paneled and sworn as such. The court shall poll the jury

to ascertain whether any juror is directly or indirectly in

terested in the illicit sale of vinous, malt or spirituous

liquor.

30

The court then appoints a foreman of the grand jury

under Section 1780, and that section prescribes their oath

which it will be seen is very strict in securing impartial

action by the grand jury, and each member of the grand

jury must also take an oath to the same effect.

Section 1781 requires the circuit judge at each term of

the criminal court to charge the grand jury concerning its

duty and to expound the law to it as he shall deem proper,

and he shall give it in charge certain actions mentioned

therein.

Section 1783 provides that all county officers shall attend

the criminal term of the circuit court and hear the judge’s

charge to the grand jury and the judge’s charge to such

officer.

It will be seen from a careful study of these sections that

they are designed to secure a fair and just administration of

the law, and to secure fair trials and prevent malicious prose

cutions, etc.

Section 1794 of the Code provides that:

“ If at any regular or special term of a circuit court

it appears that jurors have not been drawn or sum

moned for the term, or for any part thereof, or that the

jurors have been irregularly drawn or summoned, or

that none of the jurors so drawn or summoned are in

attendance, or not a sufficient number to make the

Grand Jury and three Petit Juries, the court shall im

mediately cause the proper number of jurors to be

drawn from the box and summoned, or, if there be not

a jury box to be drawn from, the court shall direct the

requisite number of persons qualified as jurors, to be

summoned to appear at such time as the court shall

appoint, and the court shall thereupon proceed as if

the jurors had been regularly drawn and summoned.”

The empaneling of the Grand Jury is conclusive of their

competence, Reynolds vs. State, 199 Miss. 409, 24 So. (2d)

31

page 781; see Moon vs. State, 176 Miss. 72, 168 So. 476.

In Moon vs. State, 176 M. 72, it was held that during the

thirty days of the box was refilled a drawing from the box

could not be had. See Sec. 1784, Code 1942; Pearson vs.

State, 176 M. 9, 167 So. 644.

In the case before us there was no jury box available

under the decisions of our court and the jurors could not be

drawn from the box during the thirty day period when the

box w'as refilled for a court which was held during that

period.

By section 1796 of the Code, a challenge to the array shall

not be sustained, except for fraud, nor shall any venire

facias, except a special venire facias in a criminal case, be

quashed for any cause whatever.

There certainly could be no fraud in the manner in which

the special venire was drawn, and consequently it could not

be quashed.

By Section 1798 of the Code the jury laws are directory

merely, and it is only where there is a departure from the

statutory scheme in the manner that prejudices the rights

of the party that the jury will be abated for any irregularity.

It is submitted that under these various statutory pro

visions that in this case on its peculiar evidence a- question

of failure to have negroes on the jury or summoned as

jurors is without prejudice.

I call the Court’s attention to the remarkable fairness of

the jury that was empaneled in this case to try the case

without prejudice, without any desire to do anything except

what was right and proper under the law. They were exam

ined at great length and were examined with reference

among other things as to whether they would give a negro

a fair trial where the killing was a killing of a white man,

32

and also as to whether they would require an extreme case

or a very strong case before they would inflict the death

penalty.

It is seldom you see where the question is raised on

whether the jury would inflict the penalty of death in case

of guilt, the matter being entirely in the discretion of the

jury if they believe the case of murder has been made out.

I have strongly been impressed with these juries’ statements

and views that would require an extraordinary case of mur

der before they would inflict the death penalty, and no com

plaint can be justly made of the jury who actually tried the

case and no question at all as to the guilt of the appellant

on the facts and evidence.

The murder was one of peculiar atrocity, and was in

spired by a desire to rob the deceased. The fact that he

was brutally beaten to death seemed, from this record, to

have been done merely to secure the money and suppress

the evidence that would exist of robbery.

I am aware that the Constitution of the United States

as construed by the Supreme Court of the United States

makes a willful or purposeful discrimination against negroes

or other classes will cause the Supreme Court to reverse a

case where the record shows that a considerable number of

negro voters existed in the jurisdiction where the crime was

committed were eligible for jury service, and that it is not

permissible to discriminate by purposeful desire not to have

a particular class on the jury. This matter was specifically

decided in the case of Norris v. the State of Alabama, 294

U. S. 587, 55 S. Ct 579, 79 L. Ed. 1074, and Hale v. Ken

tucky, 303 U. S. 613, 82 L. Ed. 1950, under which case the

rule was announced:

“A systematic and arbitrary exclusion of negroes

from grand and petit jury lists because of their race

33

and color constitutes a denial to a negro charged with

crime of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Attention must be given in studying these cases to the

language used by the Federal Court solely because of their

race or color.

In the report of this case in the 82nd L. Ed. (page 1053)

there is a case note with reference to the violation of the

constitutional rights in criminal cases by unfair practices

in selection of grand or petit juries; and at page 1055 under

the heading “Application of a Rule to a Particular Race or

Class” and sub-heading “Negroes” , many cases are cited

dealing with unfair practices by leaving races entitled to

jury service off the lists or out of the enrollment of those

who are discriminated against.

These is also an elaborate case note in 52 A. L. R. 916

appended to the case of Passar v. County Board reporting

this case as being a Minnesota case with a case note ap

pended (page 919).

I desire to call the Court’s attention to the language used

in the Am. St. Report case note quoted from Smith v. State

(Oklahoma) 4th Okla. Crim. Rep. 128, 140 Am. St. 688, in

which the following language was used by the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma:

“ The 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States does not require the jury commissioners,

or other officers charged with the selection of juries, to

place negroes upon the jury list simply because they are

negroes. The allegation that the jury was composed

solely of white men does not violate the 14th Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and

proof of that fact would not support the motion. The

ground upon which the decisions of the Supreme Court

of the United States rest is not that negroes were not

selected to sit upon juries, but that they were excluded

34

therefrom solely on account of their race or color. In

other words, there is no law to compel the jury com

missioners, or other officers of the court, to select or

summon negroes as jurors. They can select any per

sons whom they regard as competent to serve as jurors

without regard to their race or color, but the law pro

hibits them from excluding negroes solely on account

of their race or color. Therefore the judge should have

heard the testimony, and, if he found from the evidence

that there was an agreement among the jury commis

sioners to exclude negroes from the jury panel simply

because they were negroes, or that the officers charged

with the duty of selecting and summoning said jurors

had refused to select or summons negroes on the jury,

and had excluded them therefrom solely upon the

ground that they were negroes, then the judge should

have sustained said motion. There is no law requiring

an officer to place negroes on the panel simply because

they are negroes. It is his duty to select the best jurors

without regard to race or color. When this is done, the

law is satisfied.”

This language is taken from 140 Am. St. Rep. 688, which

I verified by comparison.

Our own court was in accord with the Oklahoma court

upon this question as shown by Lewis v. State, 91 Miss.

505, 45 So. 360, quoted from in appellant’s brief. In this

Lewis case our court, speaking through Justice Mayes, said:

“There is nothing in our jury law which does not

apply with equal force to all citizens, whatever be their

race or color. It is a mistaken impression, which seems

to have become prevalent, that in order to constitute

a valid jury there must be some negroes in the jury list.

Such is not the case. A jury may be composed entirely

of negroes, or it may be composed entirely of white

persons, or it may be composed of a mixture of the two

races; and in either and in any case it is a perfectly

lawful jury, provided no one has been excluded or dis

criminated against simply because he belongs to one

race or the other.”

35

Our court has also held in Farrow v. State, 91 Miss. 509,

45 So. 619, in accordance with the Federal Court:

“That where a county board of supervisors, in select

ing a list of persons qualified for jury service, knowingly

and in accordance with a well established practice, and

for the purpose of depriving negro citizens of participat

ing in the administration of justice, and intentionally,

keep off the names of negroes from such list, an indict

ment returned by a grand jury drawn from such jury

list should be quashed.”

These cases show clearly that where the omission or ex

clusion of negroes from the jury list was solely for the pur

pose of preventing negroes serving as jurors in the court and

not where the board of supervisors in making up the jury

lists selects merely the jurors for their mental and moral

qualifications; that is to say, selects men of good intelli

gence, sound judgment and fair character, from those who

have registered and qualified to vote. However, our statu

tory and Constitutional provisions have been twice before

the United States Supreme Court since 1890, the statutes

being substantially the same on this question now as then.

In Gibson v. State of Miss., 162 U. S. 567, 40 L. Ed. 1078,

our statutes and Constitution were upheld upon this ques

tion, the opinion being written by that eminent jurist,

Justice Harlan, which appears on page 1078 of the Law

Edition Reports. The Court, after citing earlier cases which

had held that discrimination against the negro because of