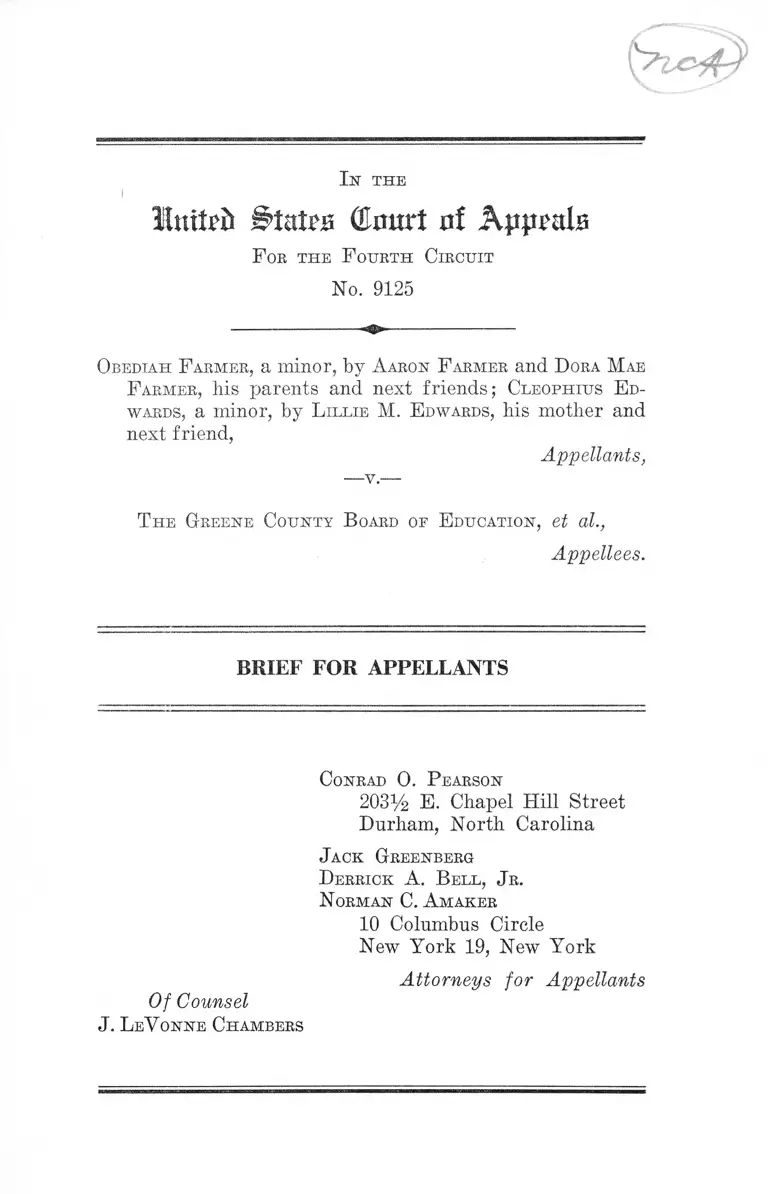

Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1963. 5d8a0666-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2e5af01c-6d9f-422b-ac01-d835824d34cc/farmer-v-greene-county-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Initio GJmtrt of Appeals

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 9125

Obediah F armer, a minor, by A aron F armer and D ora Mae

F armer, Ms parents and next friends; Cleophius E d

wards, a minor, by L illie M. E dwards, his mother and

next friend,

Appellants,

T he Greene County B oard of Education, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Conrad 0 . P earson

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell, J r.

Norman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Of Counsel

J. LeV onne Chambers

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Questions Involved ....... ................................................. 4

Statement of F acts....... ....................................................... 5

A rgument:

I. The Denial By The Court Below Of Appellants’

Motion For A Preliminary Injunction, On The

Record In This Case, And The Law Applicable

Thereto, Was An Abuse Of Discretion ............... 9

II. The Court Below Erred In Striking Paragraphs

9 And 10 Of The Complaint................................... 15

III. The Court Below Erred In Its Refusal To Permit

The Introduction Into Evidence Of The Deposi

tions Taken Of The Defendants In The Prior

Action To Desegregate The School System And

The Court Below Further Erred In Not Per

mitting Counsel For Plaintiffs To Introduce The

Transcript Of The 1959 Hearing Before The

Board On The Applications Of The Plaintiffs

In The Prior S u it...................................................... 17

Conclusion................................................................................ 21

T able of Citations

Cases:

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) ....................... 16

Batelli v. Kagan & Gaines Co., 236 F. 2d 167 (9th Cir.

1956) ...................................... .............. ............................ 21

11

Bradley v. School Board of City of Bichmond, 317 F.

2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963)...................................................... 12

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia

(4th Cir. No. 8944, June 29, 1963, not yet re

ported) ............ ................... ..... .......... ............... 11,13,15, 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ..5, 9,10

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .. 9,10

Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. United States,

261 F. 2d 819 (6th Cir. 1953) ....................................... 16

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ...............................9,10

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) ................................... 10

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) ............. ..10,11,13

Green v. School Board of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th

Cir. 1962) ......................................................... 10,11,12,14

Hill v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473

(4th Cir. 1960) .................................................................. 12

Insul-Wool Insulation Corp. v. Home Insulation, Inc.,

176 F. 2d 502 (10th Cir. 1949) ....................................... 19

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ..10,11,13,

14,15, 20

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, Vir

ginia, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ...........................12,14

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chatta

nooga, 319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) ...................15,16,17

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

Va., 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962)

PAGE

13

Ill

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283

F. 2d. 667 (4th Cir. 1960) .......................................10,13, 20

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963) ..13,14

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ............. ......... 10,13,15

Rivera v. American Export Lines, 13 F. R. D. 27 (S. D.

N. Y. 1952); 17 F. R. Serv. 26d. 62, Case 1 ........... 19

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940) ........................... 10

Township of Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 TJ. S. 620

(1946) ...................... ............. .... ..... ............... ................. 13

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d

630 (4th Cir. 1962) .................................. .......... ............. 10

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §1292 ................................. 1

28 U. S. C. §1343 ................................................................ 1

42 TJ. S. C. §1981 .............................................................. 1

42 TJ. S. C. §1983 .............................................................. 1

F. R. C. P. Rule 23(a)(3) ............................................. 1

F. R. C. P. Rule 26(d) (2) and 26(d) (4) .........................18,19

N. C. Gen. Stat. §§115-176 to 115-179 ............................ 10,13

Other Authorities:

4 Moore’s Fed. Prac. 1(26.33 .............................................. 19

Note, 62 Col. L. Rev. 1448 (1962) ................. ................. 13

PAGE

In t h e

United States (Em irt nt A p p e a ls

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 9125

Obediah F armer, a minor, by A aron F armer and D ora Mae

F armer, his parents and next friends; Cleophius E d

wards, a minor, by L illie M. E dwards, M s mother and

next friend,

Appellants,

T he Greene County B oard oe Education, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal is from an order denying appellants’ Motion

for Preliminary Injunction against the operation of the

public schools of Greene County, North Carolina, on a

racially segregated basis (224a). This appeal is brought

under 28 U. S. C. §1292.

The complaint was filed as a spurious class suit pursuant

to Rule 23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina, Washington Division, on March 4, 1963.

There was jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1343 and 42

U. S. C. §§1981 and 1983. In essence, it alleged that the

defendants, Greene County Board of Education and the

Superintendent of Schools, Gerald D. James, maintained

a compulsory biracial school system, in the county via the

2

assignment of school children to public schools in the county

on the basis of race or color and through the perpetuation

of dual school zones or attendance lines based on race or

color. The complaint also alleged in paragraphs 9 and 10,

that an earlier action to desegregate the schools was filed in

May, 1960 by the two adult plaintiffs herein, parents of the

infant plaintiffs in this action, and another Negro parent,

residing in the county. It was alleged that this prior action

was dismissed by the District Court on January 21, 1963

after the five orginal minor plaintiffs had either graduated

or dropped out of school and the court had refused to allow

the present adult plaintiffs to intervene their children who

were still in attendance at the Greene County schools. It

was further alleged that the previous action had been insti

tuted after the five original plaintiffs had applied to the de

fendant school board for reassignment for the 1959-60 school

term on a racially nondiscriminatory basis pursuant to

the provisions of the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act

and regulations of the Board and had been denied reas

signment, The complaint also averred that plaintiffs had

not again sought to exhaust the remedies of the Enroll

ment Act prior to bringing this action because exhaustion

would be “ futile and useless.” Accordingly, the complaint

prayed the issuance of a preliminary and permanent in

junction against continued operation of a biracial school

system in the county (la-9a).

Motion for Preliminary Injunction or, in the alterna

tive to require the defendants to present a plan for desegre

gation was filed on March 5, 1963 (10a-12a).

The defendant school board thereafter moved to strike

paragraphs 9 and 10 of the complaint relating to the prior

action and also moved to strike paragraph 6 and the por

tion of. paragraph 12 of the complaint containing aver

ments with respect to the election, assignment and trans

fer of teachers, principals and other supervisory person

nel on a racial basis (13a-20a). A Motion to Dismiss the

3

action as to him was filed by the Superintendent of Schools,

Gerald James, on the ground of his lack of authority to

assign or transfer either school children or teachers with

in the Greene County system (21a-23a).

Hearing on the Motion for Preliminary Injunction began

on April 24, 1963. At the beginning of the hearing, defen

dants filed an Answer to plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary

Injunction (37a-38a). The hearing commenced with the oral

testimony of the adult plaintiffs Dora Mae Farmer and

Lillie M. Edwards (39a-84a). At the conclusion of this

testimony, the hearing was continued until further notice

(84a).

When the hearing was resumed on May 29, 1963, plain

tiffs examined Superintendent of Schools James and the

Chairman of the Greene County Board of Education, H.

Maynard Hicks. Plaintiffs also sought to put in evidence

the depositions of the School Superintendent and Board

Chairman taken in the earlier dismissed action, but the Dis

trict Court did not allow their introduction (202a-208a).

Plaintiffs’ offer of the transcripts of the hearings held be

fore the Board on the applications for transfer of the

five students was also rejected. At the conclusion of the

hearing, plaintiffs orally renewed their Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction which the court denied, indicating that

it would file a formal written order at a later date (221a).

On June 15, 1963 the District Court, after making its

findings of fact, issued its order denying plaintiffs’ Motion

for Preliminary Injunction from which this appeal is taken.

The Court retained jurisdiction of the cause for the pur

pose of determining the motions to strike and dismiss

(230a-231a).

On June 17, 1963, the District Court granted the defen

dant school board’s Motion to Strike paragraphs 9 and 10

4

of the complaint, but denied their Motion to Strike para

graph 6 and a portion of paragraph 12 relating to teacher

segregation (232a). On the same day, the Court granted

Superintendent James’ Motion to Dismiss the action as

to him (233a).

Answer was filed on July 1, 1963 (234a). Plaintiffs filed

Notice of Appeal on July 12, 1963 (261a).

Questions Involved

The following questions were raised in the complaint

(la-9a) and proffered evidence and in plaintiffs’ objection

to defendants’ motion to strike paragraphs 9 and 10 of the

complaint, and were decided adversely to plaintiffs (230a,

232a, 208a).

(1) Whether plaintiffs, Negro school children and par

ents, are entitled to injunctive relief restraining the con

tinued operation of the Greene County public school system

on a racially segregated basis and an order requiring the

school Board to admit the nominal plaintiffs to the schools

of their choice and to submit a plan for assigning all other

pupils in the school system to the public schools without

regard to their race.

(2) Whether the trial court erred in granting the defen

dants’ motion to strike paragraphs 9 and 10 of the com

plaint showing that prior requests had been made of the

defendants to eliminate racial segregation in the schools

by applying the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act in

a nondiscriminatory manner.

(3) Whether the trial court erred: (a) in ruling that

defendants’ depositions taken in the prior dismissed action

were inadmissible in this action where the introduction of

5

said depositions was for the purpose of giving evidential

support to plaintiffs’ contention that the defendants have

not utilized the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act as

a means whereby Negro children assigned initially on a

racial basis could obtain transfer without regard to race;

(b) in excluding plaintiffs’ offer of the transcripts of hear

ings held before the Board of Education in 1959 on the

applications for transfer of five Negro applicants from the

one all-Negro high school in Greene County to the one all-

white high school.

Statement of Facts

The Greene County school system has approximately

5.000 pupils, approximately 3,000 of whom are Negro and

2.000 of whom are white (100a, 226a). The system has

eight elementary and two public high schools, one high

school (Greene County Training School) being attended

exclusively by Negro children and one high school (Central

High School) being attended solely by white children (93a-

95a, 130a-131a, 226a). The Greene County Training School

was constructed in 1951 for the purpose of bringing to

gether all the colored high schools in the County into one

consolidated training school (98a). The Greene Central

High School was completed in 1961 (95a). Appellant,

Obediah Farmer, is now enrolled in the ninth grade at

Greene County Training School and appellant, Cleophius

Edwards is now enrolled in the tenth grade at that school

(228a).

There are 170 teachers in the school system of which

95 are Negro and 75 are white (139a, 226a).

Subsequent to the decision of the United States Supreme

Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

6

(1954), the Greene County Board of Education was au

thorized by the North Carolina Legislature, N. C. Gen.

Stat., §§115-176, et seq., to assign pupils within the County.

Pursuant to this authorization the Board has divided the

schools into school districts and students living within the

defined districts are assigned to the school therein. The

Superintendent of Schools of Greene County, Gerald D.

James, testified that pupils were assigned on the basis of

district lines drawn by the Board; that he had not gone

through the Board files to determine whether two district

maps were used—one for Negroes and one for whites—but

that no Negroes had been assigned to a school attended

solely by white children nor had a white child been as

signed to a school attended solely by Negroes (94a-95a,

113a-129a).

Following the adoption of the North Carolina Pupil En

rollment Act, the Board has continuously assigned Negro

elementary pupils to four elementary schools attended ex

clusively by Negroes and white students to four elementary

schools attended exclusively by whites. Teachers and other

school personnel are also allocated on a segregated basis

(121a, 125a, 140a, 200a-201a). The Board has a “ feeder

system” by which students completing the four “ Negro”

elementary schools are assigned to the one high school at

tended exclusively by Negroes while whites are assigned to

the high school attended exclusively by whites (129a-131a).

The Board has also adopted regulations governing re

assignment of pupils by which pupils who are dissatisfied

with their assignment may apply to the Board for reas

signment to another school, but aside from this “ assignment

plan” the Board has never published any kind of document

which would indicate to a Negro parent that he could enroll

his child in a school that was attended by white children

(175a). The standards or criteria for arriving at a decision

7

on transfer applications are those contained in the North

Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act but the attempt to elicit

through the testimony of the chairman of the School Board,

H. Maynard Hicks, the manner in which these criteria have

been used in passing upon transfer applications came to

naught. His testimony was that the Board considers each

individual application separately, taking into account “all

of the information that the Board could get” to determine

whether a reassignment “was for the best interest of the

child . . . (and) of the Greene County School system”

(182a-183a). No further elucidation of this was tendered by

the Board Chairman. When asked by plaintiffs’ counsel:

Q. Well, what would be the kind of consideration

that would lead to a judgment as to whether or not

the granting or denial of an application was in the best

interest of the child ?

Chairman Hicks replied:

A. There is no way I can answer that (183a).

At any rate, whatever the use to which the standards and

criteria have been put, no desegregation of the schools has

resulted.

In 1959, five Negro children, members of three families,

two of which are involved in this present proceeding, ap

plied to the Board for assignment to the Walstonburg High

School, the high school then attended exclusively by whites.

Prior to the filing of the applications, the Board had decided

to close the Walstonburg High School (180a, 228a). The

Walstonburg High School has been closed (229a) and re

placed by Central High School (95a). Both adult plain

tiffs testified that they are seeking reassignment of their

children from Greene County Training School to Central

8

High because Central is closer to their respective places of

residence (52a, 70a).

Each application for reassignment was heard and con

sidered separately by the Board on the basis of the cri

teria set forth under the rules and regulations governing

changes in assignment. Each application was denied be

cause in the School Board’s judgment, granting them would

not have been “ in the best interest of either the child

involved or the school board” (183a). However, Board

Chairman Hicks was unable to state the basis upon which

that judgment was made or to supply a reason why the

applicants were not assigned to the “white” high school that

was to replace the Walstonburg School (183a).

Following the denial of their applications, these five

pupils filed suit in Federal District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina in May 1960, seeking relief

similar to that sought here (5a). This suit was dismissed

after two of the five pupils had graduated from school,

one had dropped out and two had moved from the County

(5a, 228a-229a). No subsequent petitions or applications

for reassignment by any Negro school children, including

appellants, have been filed with the School Board since

that time (229a). However, the adult appellant, Dora Mae

Farmer, testified that an application to the Board for re

assignment of her child was not made because she felt it

would be “a waste of time” in light of the Board’s action

on her prior application (49a-50a).

9

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Denial by the Court Below of Appellants’ Motion

for a Preliminary Injunction, on the Record in This

Case, and the Law Applicable Thereto, Was an Abuse

of Discretion.

1. The Greene County school system is completely seg

regated (94a-95a; 121a-130a; 200a-201a). Prior to and fol

lowing the decision of the United States Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), ap

pellee, the Greene County Board of Education, has continu

ously assigned Negro pupils to schools attended and staffed

exclusively by Negroes. White pupils are assigned to

schools attended and staffed exclusively by whites (94a-

95a; 121a-130a; 200a-201a). Such assignments are made

irrespective of the school district in which the Negro and

white pupils reside and irrespective of any standards or

criteria except the race of the pupil (52a, 104a-125a). No

Negroes have been initially assigned to a white school

(125a). Even though Negro pupils live nearer to white

schools, they have been and continue to be initially as

signed to all-Negro schools (52a, 70a).

The fundamental teaching of Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra is that separation of students in public schools

on the basis of race offends the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the second Brown opinion, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), school

authorities were given primary responsibility for effecting

the “transition to school systems operated in accordance

with the constitutional principles set forth in . . . [the

first Brown] decision.” Id. at 300. And in Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 6-7 (1958), the Supreme Court called for “ the

10

earliest practicable completion of desegregation, and . . .

appropriate steps [by school authorities] to put their pro

gram into effective operation . . . ” as well as for ua prompt

start, diligently and earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial

separation in the public schools. . . . ” The right to nondis-

criminatory education is a personal right. Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300 (1955), and may not be

denied by a state directly or indirectly through evasive,

ingenious or ingenuous schemes. Cooper v. Aaron, supra;

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940); Cf. McCoy v. Greens

boro City Board of Education, 283 F. 2d 667 (4th Cir. 1960).

Nine years following the Supreme Court’s decision in

Brown, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the appellee School Board has

taken no steps to eliminate its discriminatory separation

of students in the public schools. Nor has it offered any

plan for desegregation of its school system save the North

Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act, N. C. General Statutes

§115-176, et seq. Decisions of this Court and of other Cir

cuits have consistently held that notwithstanding the

validity of pupil assignment acts on their face, they may

not be selectively applied. Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d

621 (4th Cir. 1962); Wheeler v. Durham City Board of

Education, 309 F. 2d 630 (4th Cir. 1962); Green v. School

Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962);

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 289

F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961); Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962);

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959). Thus, even if it be

conceded that the Pupil Enrollment Act under which ap

pellee operates is valid on its face, the record clearly shows

that it has been applied so as to perpetuate, rather than

to eliminate, the discriminatory practices condemned in

Brown, supra. As shown by the record in this case, ap

11

pellee has continuously assigned Negro pupils to schools

attended exclusively by Negroes, even though they may live

nearer to a white school. That Negro and white pupils

have been, and continue to be, assigned to separate schools

is itself sufficient to show that appellee is actively engaged

in perpetuating segregation. Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Virginia (4th Cir. No. 8944, June 29,

1963, not yet reported) ; Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Gibson

v. Board of Public Instruction, supra.

Nor is it an answer, at least under the facts of this

case, that Negro parents “voluntarily” enroll their children

in all-Negro schools. This Court has held that in the

absence of some publication by school authorities that

pupils may freely enroll in the school of their choice, no

question of voluntariness exists. Jeffers v. Whitley, supra

at 626. As stated by this Court in Jeffers, “ Since the schools

have been operated on a completely segregated basis,

parents of preschool children cannot be said to have any

freedom of choice, until there has been some announce

ment that such a right exists.” Ibid. Appellee has pub

lished no announcement of any kind informing Negro

pupils that they could enroll in or transfer to the school of

their choice (175a). Thus, it cannot be said that separation

of the races in the public schools of Greene County is volun

tary. Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Virginia, supra.

Moreover, the fact that pupils dissatisfied with their

assignment may petition the appellee for reassignment

to another school does not justify the initial discriminatory

assignments. Such practices were expressly condemned in

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, supra:

Every white child is initially assigned to a school

in a section other than section II, regardless of how

near he might reside to a section II school. Every

12

Negro child, on the other hand, is initially assigned to

a section II school, regardless of his place of resi

dence or any other criteria. The Negro child, if he

desires a desegregated education, must thereafter

run the gauntlet of numerous transfer criteria in order

to extricate himself, if he can, from the section II

schools. These are hurdles to which a white child,

living in the same area as the Negro and having the

same scholastic aptitude, would not be subjected, for

he would have been initially assigned to the school

to which the Negro seeks admission. In Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F. 2d 72,

77 (4th Cir., 1960), this practice was expressly con

demned. . . . 304 F. 2d at 123.

Here, as in Green, white pupils living in the same area

as Negro pupils are initially assigned to white elementary

schools. The appellee’s “ feeder system” assigns students

completing the four Negro elementary schools to one high

school attended exclusively by Negroes. Only by running

the gauntlet of appellee’s reassignment regulations will a

Negro pupil be able to transfer to a school to which a

white pupil, similarly situated, would have been initially

assigned. Such practices deprive the appellants of their

constitutional right to nondiscriminatory education even

though the same reassignment rules might be applied to

white pupils who desire to transfer. Bradley v. School

Board of City of Richmond, 317 F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963);

Green v. School Boad of City of Roanoke supra; Hill v.

School Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir.

1960). For as pointed out by this Court in Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F. 2d 72, 77

(4th Cir. 1960), because of the existing segregation pat

tern, it will be Negro pupils, primarily, who seek transfers.

These holdings are in complete accord with those of other

13

circuits. E.g., Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis, supra; Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction

of Dade County, Florida, supra.

2. The court below denied the appellants’ motion for a

preliminary injunction apparently on the ground that ap

pellants failed to exhaust their administrative remedies

(224a-231a). It is well established, however, that this rule

presupposes the administrative remedy to be effective.

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963);

Township of Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620

(1946). Thus, “ administrative remedies need not be sought

if they are inherently inadequate or are applied in such a

manner as in effect to deny the petitioners their rights.”

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283 F. 2d

667, 670 (4th Cir. 1960); Bell v. School Board of Powhatan

County, Virginia, supra; Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Marsh

v. County School Board of Roanoke County, Virginia, 305

F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962); Note, 62 Col. L. Rev. 1448 (1962).

Appellants seek by this suit to obtain complete desegre

gation of the Greene County school system. The reassign

ment procedures of the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment

Act, General Statutes §§115-178 and 115-179, and the ap

pellee’s rules and regulations (254a-258a) do not purport to

and cannot afford the appellants the relief they seek. The

administrative remedies to which the Court below referred

(228a-230a) govern only reassignment of pupils who are

dissatisfied with their particular assignments and make no

reference whatever to elimination of discriminatory prac

tices in initial assignments or in the appellee’s “ feeder

system.” Nor do these rules afford any relief for eliminat

ing discriminatory appointments of teachers and school

personnel.

14

Appellants do not seek merely the assignment of nominal

plaintiffs to the white high school. Rather, they seek to en

force their constitutional right to have appellee School

Board eliminate all practices of discrimination in its school

system. Appellants have no administrative remedy for such

relief and rightfully asserted their rights in the first in

stance in the federal court. McNeese v. Board of Education,

supra.

Moreover, the administrative remedies which the lower

court would have appellants exhaust subject appellants to

requirements not applied to white pupils. Appellee has

turned to the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act only

when considering transfer requests. No use is made of this

Act in making initial assignments, or if so, the record

clearly shows that the Act has been and continues to be

unconstitutionally applied. As stated by this Court in

Jeffers v. Whitley, supra, where administrators “ have dis

played a firm purpose to circumvent the law, when they

have consistently employed the administrative processes to

frustrate enjoyment of legal rights, there is no longer room

for the indulgence of an assumption that the administrative

proceedings provide an appropriate method by which recog

nition and enforcement of those rights may be obtained.”

Id. at 627. Here, as in Jeffers, there is no basis for as

suming that the discriminatory composition of appellee’s

schools resulted from the free volition of the pupils and

their parents. Because of racial customs and practices,

only Negro pupils primarily will be seeking transfers.

Clearly, therefore, to subject appellants to different re

quirements denies them their constitutional rights. Green v.

School Board of City of Roanoke, supra; Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, supra. Nor is there basis

for assuming that their rights would be protected if re

quired to first seek relief before appellee. Thus, to deny

appellants’ request for preliminary relief against the dis

15

criminatory practices of appellee is a clear abuse of dis

cretion. Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Bell v. Board of Pow

hatan County, Virginia, supra; Northcross v. Board of

Education of the City of Memphis, supra.

II.

The Court Below Erred in Striking Paragraphs 9 and

10 of the Complaint.

In Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chat

tanooga, 319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963), a question similar to

that presented here was raised. There the appellee school

board moved to strike allegations of a complaint by individ

ual pupils that they were injured by the board’s policy of

assigning Negro and white school personnel on an inte

grated basis. There, as here, the plaintiffs prayed that the

school board be enjoined from assigning school personnel

on the basis of race or in the alternative, that the school

board submit a plan for reorganization of its schools on an

integrated basis. In reversing the trial court’s order strik

ing these paragraphs from the complaint, the Sixth Circuit

stated:

We agree that the teachers, principals and others

are not within the class represented by plaintiffs and

that plaintiffs cannot assert or ask protection of some

constitutional rights of the teachers and others, not

parties to the cause. We, however, read the attack

upon the assignment of teachers by race not as seek

ing to protect rights of such teachers, but as a claim

that continued assigning of teaching personnel on a

racial basis impairs the students’ right to an education

free from any consideration of race. Neither by the

first Brown decision, nor by its later decisions has the

Supreme Court ruled upon the question of law pre

16

sented. None of the Circuits have ruled upon the

question. 319 F. 2d at 576.

The Court in Mapp did attempt to rule on “ the legal ques

tion presented as it relates to the assignment of teachers

and principals.” It quoted from its decision in Brown &

Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. United States, 261 F. 2d 819,

822 (6th Cir. 1953), to the effect that:

Partly because of the practical difficulty of deciding

cases without a factual record it is well established

that the action of striking a pleading should be spar

ingly used by the courts. Colorado Milling <fb Elevator

Co. v. Howbert, 10 Cir., 57 F. 2d 769. It is a drastic

remedy to be resorted to only when required for the

purposes of justice. Batchelder v. Prestman, 103 Fla.

852, 138 So. 473; Collishaw v. American Smelting &

Refining Co., 121 Mont. 196, 190 P. 2d 673. The mo

tion to strike should be granted only when the plead

ing to be stricken has no possible relation to the con

troversy. Samuel Goldwyn, Inc. v. United Artists Cor

poration, D. C., 35 F. Supp. 633; Wooldridge Mfg. Co.

v. R. G. La Tourneau, Inc., D. C., 79 F. Supp. 908.

Ibid.

And applying these rules to the case before it, the court

restored the stricken allegations to the complaint to “await

developments in the progress of the plan approved.” Cf.

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F. 2d 862, 868 (5th Cir. 1962).

Paragraphs 9 and 10 of appellants’ complaint are ma

terial and essential to appellants’ case. As allegations

susceptible of proof and in fact proved, they were designed

to show not only that the defendants had been put on

notice that desegregation of the school system was de

17

sired, but also that attempts in this regard had been made

including resort to the administrative remedy which resort

had produced no results and was unlikely to produce any.

If allegations in a pleading which pose a legal question, de

cision as to which may be deferred, may not be stricken,

see Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga,

supra, a fortiori, allegations raising essential and material

issues to a case are not to be stricken.

III.

The Court Below Erred in Its Refusal to Permit the

Introduction Into Evidence of the Depositions Taken

of the Defendants in the Prior Action to Desegregate

the School System and the Court Below Further Erred

in Not Permitting Counsel for Plaintiffs to Introduce

the Transcript of the 1959 Hearing Before the Board

on the Applications of the Plaintiffs in the Prior Suit. 1

1. As the record indicates, after denial of the applica

tions of the five Negro children in 1959 for reassignment to

the Walstonburg High School from the Greene County

Training School, those individuals filed suit against the

parties who are appellees here seeking substantially the

same relief as asked for in the present suit. During the

course of the prior suit, depositions of the Superintendent

of Schools, Gerald James, and Chairman of the Board,

H. Maynard Hicks, were taken pursuant to the discovery

procedure of the Federal Buies of Civil Procedure. The

suit was later dismissed after two of the five plaintiffs had

graduated, two had moved out of the County, and one had

dropped out of school (5a, 228a).

During the course of the resumed hearing on the motion

for preliminary injunction on May 29, 1963, counsel for

plaintiffs (203a) sought to introduce into evidence the depo-

18

sitions taken of the defendants in the prior dismissed action

hut were not permitted to do so by the District Court (208a).

The purpose of seeking to introduce the depositions was

to place in the record of this action the admissions of the

Superintendent of Schools and the Chairman of the Board,

defendants in both causes, which would have supported

plaintiffs’ contentions that the misconduct of the Board

had persisted unabated from 1959, the time of the original

applications, through the present time since those deposi

tions clearly manifested a continuing course of discrim

inatory conduct.

The court below was clearly wrong in not allowing the

introduction of the depositions. The applicable federal

rules are Rule 26(d )(4 )1 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure and Rule 26(d)(2) of the Rules.* 2 The former

rule allows the use of a deposition taken in an action that

"Rule 26(d)(4) :

“ (4. ̂ * * *

“ Substitution of parties does not affect the right to use

depositions previously taken; and, when an action in any court

of the United States or of any state has been dismissed and

another action involving the same subject matter is afterward

brought between the same parties or their representatives or

successors in interest, all depositions lawfully taken and duly

filed in the former action may be used in the latter as if

originally taken therefor.”

2Rule 26(d)(2) :

“d) Use of Depositions. At the trial or upon the hearing

of a motion or an interlocutory proceeding, any part or all of

a deposition, so far as admissible under the rules of evidence,

may be used against any party who was present or represented

at the taking of the deposition or who had due notice thereof,

in accordance with any one of the following provisions:

# # #

“ (2) The deposition of a party or of any one who at the

time of taking the deposition was an officer, director, or man

aging agent of a public or private corporation, partnership,

or association which is a party may be used by an adverse

party for any purpose.”

19

has been dismissed in a subsequent action involving the

same subject matter and the same parties, their repre

sentatives, or successors. The defendants in this action are

exactly the same as the defendants in the prior action, the

gravamen of the suit is exactly the same, and the only

variance is with respect to the named plaintiffs. Yet, even

here, two of the adult plaintiffs are identical to those in the

former action. Rule 26(d)(4), when read in conjunction

with Rule 26(d)(2) which permits the use by an adverse

party of a deposition for any purpose, removes all doubt

as to the propriety of the attempted introductions of the

depositions at the May 29 hearing.

In addition to the language of the Rules, there is case

law authority with which the District Court was presented

(202a) but chose to ignore. Insul-Wool Insulation Corp.

v. Home Insulation, Inc., 176 F. 2d 502 (10th Cir. 1949);

Rivera v. American Export Lines, 13 F. R. D. 27 (S. D.

N. Y. 1952), 17 F. R. Serv. 26d.62, Case 1. Gf. 4 Moore’s

Fed. Prac. U26.33:

The deposition of a party taken in a prior dismissed

action may be used in the federal court by an adverse

party for any purpose, including the use as evidence

of admissions, against the party, or the representative

or successor in interest of the party whose deposition

was taken.

Under the more orthodox practice, in order for the

deposition to be admissible in the second action, the

parties must be the same, or their privies, and the

issues must be substantially the same. But this prac

tice has yielded in appropriate situations to admis

sibility where there is solely an identity of issues be

tween the two actions. 2

2. In 1959, five Negro pupils, not involved in this pro

ceeding, filed applications with appellee for reassignment

20

to the white high school. Following the hearing and subse

quent denial of their applications, these pupils filed suit

against appellee in the Federal District Court for the East

ern District of North Carolina.

At the resumed hearing on their motion for preliminary

injunction, appellants tried to place in evidence the minutes

of the 1959 hearing to show the discriminatory methods

by which appellee considered the applications for transfer

(184a). In appellants’ view, introduction of these minutes

would have aided presentation of its ease by giving addi

tional support to their argument—reiterated many times

before the trial court—that the attempt to pursue the ad

ministrative remedy was an unavailing act. The Court re

fused to permit this evidence on an issue which obviously

was crucial in the court’s view (see Findings of Fact Nos.

13,15; 228a-229a). Clearly, evidence of discriminatory con

sideration of Negro applications for transfers was relevant

and the trial court’s ruling prejudiced appellants in sus

taining their burden of proving the discrimination. For,

as held by this Court in Jeffers v. Whitley, supra, at 267,

use of administrative processes by state officials to frus

trate the enjoyment of constitutional rights eliminates any

necessity for exhaustion of administrative remedies. See

also, McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, supra.

Nor is it important that appellants here were not in

cluded among those who had made application to the Board.

Appellants sought to show by this evidence unswerving

maintenance of the policy of segregation under the guise

of application of the standards of the Pupil Enrollment

Act. They were not required to show that with respect to

any particular application of theirs discriminatory criteria

had been applied, cf. Jeffers v. Whitley, supra; Bell v.

Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, supra; McCoy v.

21

Greensboro City Board of Education, supra, the view ap

parently taken by the court below. Even if such proof were

required, any substantial harm to appellee resulting from

admitting such evidence was removed by Board Chairman

Hicks’ admission (183a-184a) of the vague standards ap

plied in considering the applications for reassignment. See

Batelli v. Kagan & Gaines Co., 236 F. 2d 167 (9th Cir.

1956).

CONCLUSION

W herefore, appellants respectfully pray that the judg

ment below be reversed and the cause remanded to the

District Court with instructions to :

1) admit appellants to the schools of their choice for

the school semester commencing in January or February,

1964 so that a start toward desegregation of the public

schools of the county may be made;

2) enter an order enjoining appellees from continuing

to maintain the unconstitutional policy and practice of

segregation within the public schools of Greene County;

3) enter an order requiring appellees to submit a com

plete plan for desegregation of the Greene County pub

lic school system commencing with the 1964-65 school year;

4) enter an order restoring paragraphs 9 and 10 of the

Complaint and permitting the introduction into evidence

of the depositions taken in the prior dismissed action and

the minutes of the hearing held before the Greene County

22

Board of Education in 1959 on the applications for reas

signment of the five Negro school children who were plain

tiffs in the prior action.

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad 0 . Pearson

2033/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. B ell, Jr.

Norman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel

J. L eV onne Chambers

-