Scott v Winston Salem Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1975

37 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Scott v Winston Salem Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1975. 0b3a9cce-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2e946855-d4bf-4c30-a80b-8686536a7424/scott-v-winston-salem-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

;-T t ::u ,

irrr • .. c api

(•O! TilE YOUR'iN CIRCUIT

1V0. 75—305S

c . s c o t?, <-.t ai..,

Piaiiitirf£ -Appell&ncs,

V! ; £S VO-T- J 'AI.EM/>• 0 RSYTH COUNTY

• T&S&HD 01 EDUCATION, eh. a L f

Def er-davits-App; 'ller.o.

Appeal NrO’-. "faited States District Court;

The diddle District Of North Carolina

•/. i - it-1 o> a--0 a 1 ora Div is ten

'■ rr.*r : i .r ....

POR

o'. ~rr.r_r n- •.rt.: ■

lYPEiiANTS

i.t'rr zz rotr

J. LeVOKNE CHAMBER,*

ChaiPberu , St&ir. & Fer9u.sc:?

. 951 S. In( • ■ Boulevard

Charlotte, Worth Carolina. 20202

JACK GREE1-TBB RG

JAKES m . FABRIC?, III

NORMAN J. OH&CHRIN

10 Coiunlrus Circle

Hew York, New York 100x2

.01 eys f €•>r ■ Pi air ;

INDEX

Page

Issue Presented For R e v i e w..... ......................... 1

Statement of the Case .................................... 2

Statement of Facts .......... ............................. 3

Argument

I. Section 718 Requires The Award Of

Counsel Fees In This Case And There

Are No Special Circumstances Present

In This Case Which Would Render An

Award Of Attorneys1 Fees Unjust.......... 13

II. The Doctrines Of Res Judicata, Waiver

And Estoppel Are Inapplicable To This

Case Because The Issue Of Counsel Fees

Was Pending On Both The-Effective

Date Of Section 718 And On The Date

( O p Ip i f c Counsel

Incurred From October 1968 To June

1972......................... .......... . 20

A. Plaintiffs have repeatedly

pressed their claim to counsel

fees and have not waived the

claim during the course of this

litigation.... ........................ 20

B. Plaintiffs' claim'for an award of

counsel fees for the period prior

to the effective date of Section

718 is not barred by the doctrine

of res judicata because the

District Court's September 19,

1973 order dealt only with counsel

fees for an appeal to this court.... 22

III. The Bradley Decision Makes §718 Appli

cable To All Cases In Which The Issue

Of Counsel Fees Was Pending Resolution

On Its Effective- Date, And Is Not

Limited To Cases In Which The Specific

Issue Was Pending Resolution On Appeal

At That Time.............................. 26

Conclusion 30

Table of Authorities

Cases :

Paqe

Allegrini v. DeAngelis, 68 F. Supp. 684 (E.D.

Pa. 1946,', aff' d. 161. F.2d 184 (3d Cir.

1947) ........................................ . 18n, 21n, 22n, 25n

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495

F . 2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... ..... 18n

Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan County, 321

F .2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963) . .................. . 13n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696

(1974) ........................... ................ . 2, 3, 10, 12, 14,

15, 16n, 19, 20n,

21, 23n , 26 , 27,

28, 29

Brewer v. School Bd . of Norfolk, 500 F.2d

1129 (4th Cir. 1974) ................. .......... . 2 9n , 30

T9 t r ’ c n ▼ T T5 i' s n v* ■C C /~\ "1 Z- ' /'.w r - ® V* Q p -f - * ft <-.1-. •! 1 r --

i -S v t .J V • Vwi kJ O.. U ' - i i U J i- V_L U11 J_ O O J_ i ' lU J J X X C . ;

402 U.S. 33 (1971) . ............................................ ..... 6n , 16

F.D. Rich Co., Inc. v. Industrial Lumber Co.,

417 U.S. 116 (1974) .......................................................................................................................................... 13n

Gates v. Collier, 489 F.2d 298 (5th Cir. 1973),

pending on petition for rehearing en banc . . . 19n

Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973) ...................................................................................................... 19n

Incarcerated Men of Allen County v. Fair, No.

74-1052 (6th Cir., Nov. 13, 1974) _______________________________. 19n

Mills v. Electric Autolite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970) 19n

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th

Cir. 1973) ..................................... 18n

Nesbit v. Statesville City 3d. of Educ., 418 F.2d

1040 (4th Cir. 1969) .......................... 4n

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ...... ,....... ....................... .. 13n

i i

Table of Authorities (continued)

Cases (continued):

Pa ere .

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 412

U.S. 427 (1973) .................. ......... .. . 13

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) .................. .. . 18n

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S.

443 (1968) ................. ........ ....... .. . 17

Schwarz v. United States, 381 F.2d 627 (3d Cir.

1967) ........................... ;........ . . . 2In, 22n

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala.), aff'd

409 U.S. 942 (1972) ..... ................... 1 9n

Smith v. North Carolina State Bd. of Educ., No.

'2572 (E.D.N.C., Sent. 26, 1974) ....... ...... . 15n, 27

Spxague v. Ticonic Nat1 i Bank, 307 U.S. ibr (1939) l3n, i8n, 2 in-, 22n

Stanford Daily v. Zuircher, 366 F. Supp. 18 (N.D.

Cal. 1973) .............................. . . . 15n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ:.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..... ....................... 6n, 16, 22

Thompson v. School Bd. of.Newport News, 472 F.2d

177 (4th Cir. 1972) .............. ..........

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S.

268 (1969) .................................... . 27n

Union Tank Car Co. v. Isbrand’csen, 416 F.2d 96

(2d Cir. 1969) ....................... , . 2 In, 22n

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cr. 103 (1801). 27n

Statute:

20 U.S.C. §1617 [§718, Education Amendments of

1972] ................................ ....... . 1, 2, 3, 10, 12, 13,

14, 16n, 17, lOn, 19n,

20, 22, 23n, 24, 27,

2 9

Page

Rules:

F.R.A.P. 38, 39 ........................ ........... 24

F.R. Civ. P. 54(d) ....................... 2, 25

O ther Author it leg;:

114 Cong. Rec. 10760-64, 11339-45 ................ 13

117 Cong. Rec. 11343, 11521 ......... . 13

Goodhart, Costs, 38 Yale L.J. 849 (1929) .......... 13n

Hearings Before the Senate Select Committee on

Equal Educational Opportunity, 91st Cong.,

Part B, pp. 1516-34 .................. ....... . 13

6 Moore's Federal Practice 54.77 [9] .............. 21n

10 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure §2679 (1973) ............ . . ........ 21n

Table of Authorities (continued)

rv

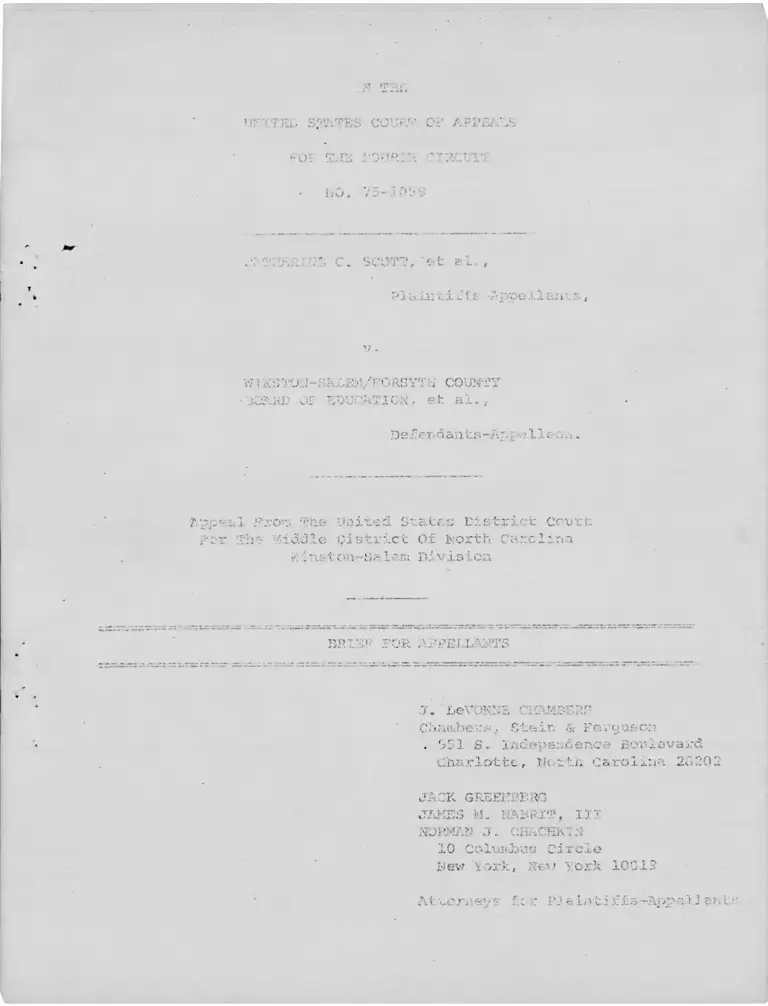

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-1059

CATHERINE C. SCOTT, et. al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

WINSTON-SALEM/FORSYTH COUNTY

BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of North Carolina

Winston-Salem Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issue Presented For Review

Did the District Court err in failing to- award counsel fees

to plaintiffs pursuant to Section 718 of the Education Amendments

of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1617, because costs had previously been taxed

in this matter when the Court awarded fees for appellate

proceedings pursuant to the mandate of this Court?

Statement o_f_ the Case

This appeal challenges the refusal of the District Court to

award prevailing plaintiffs in this school desegregation case

reasonable attorneys' fees for the period from October 2, 1968

until June 30, 1972, pursuant to Section 718 of the Education

Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1617, as interpreted by the

United States Supreme Court in Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond,

416-U.S. 696 (1974).

The District Court held., first, that Section 718 was

inapplicable to this case because it considered its September 19,

1973 Memorandum and Order, awarding attorneys' fees for appellate

proceedings pursuant to the mandate of this Court in 1973 (A. 47-

2/

49) and approving a Clerk's Memorandum taxing costs pursuant

to F.R.C.P. 54(d), to be a final determination of plaintiffs'

right to be awarded counsel fees for all prior proceedings (trial

or appellate) in this case; and second, that the interests of

justice did not require an award of fees in this case.

2/ References are to the Appendix on this appeal.

2

Plaintiffs demonstrate herein that, to the contrary, the

September 19, 1973 Order dealt only with attorneys' fees on

appeal to this Court, so that plaintiffs' prayers for a counsel'

fee award for district court proceedings are still ''pending

resolution" within the meaning of Bradley, supra; and that there

are no circumstances present in this case which would render an

aw’ard of counsel fees unjust.

Statement of Facts

Background

This school desegregation case was instituted by Negro

parents and children of Forsyth County, North Carolina, on

October 2, 1968, seeking injunctive relief against racially

discriminatory practices by the defendants in the operation and

administration of the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Public: Schools

(R. 16-29). Plaintiffs alleged in their complaint that Negro

and white students, teachers and school personnel were being

assigned to separate schools on the basis of race; that school

budgets, construction of school facilities, bus routes and extra

curricular activities and programs were being authorized,

sanctioned and promoted by defendants on.the basis of race and

color; that defendants County Commissioners, State Board of

Education and State Superintendent of Public Instruction were

dissuading and obstructing the institution and adoption of programs,

practices and policies which would eliminate racial segregation

in the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County School System and were

administering policies and practices to promote and perpetuate

racial discrimination in the school system; that defendants

refused to take appropriate and necessary steps to desegregate.

In addition to seeking elimination of the vestiges of the

dual school system, both the original and Amended Complaint

asked that plaintiffs be awarded their costs, including reasonable

counsel fees, and that the Court retain jurisdiction of the case

to award such further relief as it might deem necessary (A. 29f

3/

46). The early history of the case is set out in the margin.

3/ Following the joinder of issue but prior to completion of

discovery, and following this Court's decision in Kesb.it v.

Statesville City Bd. of Educ. , 418 F . 2d 1040 (4t.h Cir. .1969),

plaintiffs on December 17, 1969 moved for a preliminary injunction

requiring complete desegregation of the schoo.1. system no later

than February 1, 1970. The District Court conducted a hearing on

January 9, and on January 19, 1970, directed the Board to desegre

gate the facu3.ti.es in each school effective with the beginning of

the second semester of the 1969-7 0 school year-, but in no event

later than February 1, 1970. Following further hearings on

February 17, 1970, the District Court entered an order denying the

motion of plaintiffs for a preliminary injunction and expediting

the matter for final hearing on the merits. The plaintiffs noticed

an appeal from the denial of their motion for preliminary injunc

tion.

The Board filed a plan of desegregation on February 16, 1970,

pursuant to an extension granted, by the Court; plaintiffs objected

to the plan because it would have left more than 70 percent of the

black and white students in racially segregated schools. Hearings

were conducted, on April 30, 1970 and on June 25, the Court lie id

that Vv7hiie the attendance zones established by the Board had not

been gerrymandered.so as to exclude students of one race from

(continued on next page)

4

■J *

The 1973 Appeal

On March 15, 1972, the School Board submitted a revised

pupil assignment plan (A. 11) which wTould have resegregated

3/ (Continued)

particular schools, the Board had not employed "reasonable"

means to desegregate the elementary schools. The Court directed

that the Board take additional steps to desegregate 3 of the 18

all-black schools, and restrict its freedom of transfer policy

to "majority—to—minority11 transfers, but approved the Board's plan

in all other respects; the Court also dismissed the action as to

the Board of County Commissioners and the State defendants.

Plaintiffs also appealed this Order.

• On July 14, 1970, the Board filed a report and motion with

the Court pursuant to the June 25 Order. It amended its adm.inis —

• • , , ^ J , , .! « ... vn 4 « .Vl 1 -rr ^ -■* * ' - - ... 4— m •! n o v ; -)-5» 4“ 1 ~ ir* 4" O ̂ CLlatlV tr. J..UC XC O u-W pCJ.UlJ.u mu.jv-xj.uj - J, — v—*. — *

submitted a summary of programs to increase contact between the

races, and adopted a resolution to instruct its employees to

proceed with construction of two new high schools. On July 17,

1970, the District Court approved the report except that it

directed that the all-black schools be paired with 5 adjacent

white schools, that no transfers be permitted from the paired

schools, and that the Board provide transportation for other

students electing to transfer under the majority-to-minority transfer

provisions. The Board was directed to file a new plan within seven

days showing how the three black and five white schools were to be

paired. The Board noticed appeals from this Order and from the

June 25, 1970, Order requiring that the three schools be desegre

gated .

On July 31, 1970, the Board filed a plan for the clustering

of the schools and also asked the District Court to stay its Order,

and requested that the District Court require complete desegrega

tion of all schools in the system. Plaintiffs also moved to add

as parties defendant the Board of County Commissioners, the North

Carolina State Board of Education and the State Superintendent of

Public instruction since the local board had advised the Court that

these officials were threatening to withhold funds and facilities

to prevent the Board from complying with the Court's order.

(continued cn next page)

5

more than 70% of the system's elementary students. The District

Court rejected this plan on July 21, 1972, after extensive review

of both the facts and the decisions of the Supreme Court and this

Circuit. The School Board appealed.

3/ (Continued)

By order dated August 17, 1970- the Court accepted the

Board's plan for the three schools and joined the additional

defendants. September 15, 1970, the Court denied the motions of

the state officials and the County Commissioners that they be

dismissed as parties defendant, and these parties appealed on

September 16, 1970.

During the 1970-71 school year the Board's plan remained in

effect and this Court postponed argument of the various appeals

until after the United States Supreme Court's decisions in the

and Mobile cases. Swann v. Charlotte-Meek1 ̂ nbnrc- Pd

of Educ;-,— 402- IT. 5. 1 (1971) ; Davis v. Board" of

—— lil-—' 402 U.S. 33 (3 971). The case was thereafter briefed and

argued before this Court, which on June 10, 1971, remanded this

and three other cases "to the respective district courts with

instructions to receive from the respective school.boards new plans

which will give effect to Swann and Davis." Adams v. School Dist

No. 5, 444 F . 2d 99 (4th Cir. 1971). ‘ ' “ *

Pursuant to the mandate of this Court, the Board submitted

a "Revised Pupil Assignment Plan for the 1971-72 School Year,"

which the District Court approved, on July 26, 1971 for immediate

implementation. On August 23, 1971, the Board applied to Chief

Justice Burger for a stay of both this Court's June 10 decision

and the subsequent Orders of the District Court, pending certiorari

The Chie^. justice denied the Board's application for a stay on

August 31, 1971, and on October 26, 1971, the Supreme Court denied

the Board s Petition for Certiorari, without dissent. Meanwhile,

on September 19, 1971, the Board had requested tlie District Court

to reconsider and vacate its order of July 26 in light of certain

comments in the Chief Justice's opinion denying a stay.

By Memorandum and .Order of December 3, 1971, the District Court

authorized the Board to submit amendments to the plan of desegre

gation, if it desired, for the 1972-73 school vear.

6

In their Brief on the Board's appeal, plaintiffs contended

that the plan approved for 1971-72 was consistent with the

decisions of the Supreme Court and this Court, and that the

District Court was clearly correct in requiring its continued

implementation. The plaintiffs further submitted:

. . . that this is the kind of frivolous

appeal which warrants an award of double

costs and counsel fees as provided by Rule

38 and 39 of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure and now particularly by section

718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972*

Plaintiffs prayed, in conclusion,

. . . that this court should award them

double costs and counsel fees on this annual

pursuant to Rules 38 and 39 of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure and section 718

of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972

(emphasis added).

This Court, on April 30, 1973, affirmed the District Court'

denial of the Board's motion to revise its pupil assignment

plan, concluding that.:

The revision proposed by the Board in its

motion would have meant a resegregation of

a substantial portion of the school system.

Such a revision in the plan would have been

constitutionally invalid and the District

Court properly rejected it. (A. 48)

With regard to plaintiffs' request for double costs and counsel

fees for the appeal this Court stated:

The appellees have requested this Court

to award double costs and counsel fees under

Rules 38 and 39, Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure. We are not disposed to' make such

an award. However, the appellees are entitled

to an allowance of attorneys' fees under

Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act

of 1972. [Citation omitted].

The cause is accordingly remanded to the

District Court with directions to make a

reasonable allowance for attorneys' fees

in favor of appellees for services rendered

herein by them subsequent to June 30, 1972.

(A. 49)

Pursuant to this opinion and mandate, plaintiffs on June 11, 1973,

moved for allowance of costs ana expenses and counsel fees sub-

r * o or*, J-r* JTi -»v. /-> ̂ ̂97 2 t ̂0 ̂̂ }

In a letter to the District Court Clerk dated June 18, 1973

(A. 55-56), the Board questioned whether this Court's mandate

of April 30, 1973, intended to include costs. The Board went

on to say:

We assume that the motion for the allowance

of costs is made pursuant to Rule 54 rather

than to the mandate of the Court of Jvppeals

and that the District Court would have its

usual discretion in awarding costs as provided

in that Rule. (Z\. 55) (emphasis added)

With regard to plaintiffs' request for attorneys' expenses,

the Board expressed doubt whether they were "attorney's fees

within the mandate of this Court or Section 718 (ibid.).

8

The letter continued as follows:

As to the amount of attorney's fees, we

would simply leave to the Court a determina

tion of what is fair and reasonable under

the circumstances. We trust that the standards

to be applied by the Court in determining

attorneys' fee in this case would be in line

with other cases where a unit of government

or governmental agency is taxed with attorneys'

fees.•

Most of the costs listed by the plaintiffs

involve transcripts and depositions. Although

it is not stated in the Motion, we assume that

the plaintiffs are requesting to be reimbursed

for the original and one copy of each deposition

and transcript. We ask simply that the customary

rule be applied to these items, and if it is not

usual, for instance, to allow as costs the cost

of a copy of depositions, that such an allowance

t J .U U U C JL.li _jL CD t U O l

In sum we do not question that the plaintiffs

are entitled to the attorney's fees mandated by

the Court of Appeals, nor that they are entitled

to be awarded costs. We simply want to make the

Court aware that we are interested in the matter

and would not want our silence to be construed

as acquiescence in an award that is not usual and

customary in these cases.(A. 56) (emphasis added)

On September 19, 1973, the Clerk filed a Memorandum and Order

taxing costs in favor of plaintiffs in the amount of $2,441.58,

and treating plaintiffs' motion as a Bill of Costs pursuant to

Local Rule 27(c) (A. 58-63). On the same date, the District Court

filed its Order approving the Clerk's action and denying recovery

of attorneys' travel and telephone expenses (A. 64-66). On the

9

matter of attorneys' fees the court stated;

This case/was filed in 1968 and the Court

is aware of the amount and quality of legal

services rendered by plaintiffs * counsel"

throughout this litigation. The Court has

observed with approval the successful manner

in which counsel have handled this complicated

case. The Court is, however, at this time, only

concerned with what is a reasonable allowance

for attorneys1 fees fox* the preparation and,

argument of an appeal from an order of this

Court. (A. 65) (emphasis added)

Accordingly, plaintiffs were awarded $2,451.58 as costs and

$1/700.00 as attorneys' fees (A. 66).

The §718 Motion

May 15, 1974, the United States Supreme Court held in

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond. 416 U.S-. 696, that Section

/18 may be applied retroactively where the propriety of' a fee

award was pending resolution when the statute became effective.

On June 3, 1974, plaintiffs moved that the District Court award

them counsel fees, pursuant to § 718, from the initiation of

4/

thxs action on October 2, 1968 until June 30, 1972 (A. 67-68).

4/ Responses to plaintiffs' motion for counsel fees were filed

by the County Commissioners, the State Board of Education and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction. Plaintiffs are not

appealing the District Court's denial of counsel fees as against

these parties and their responses will therefore not be further

cons iaered.

10

The Board of Education responded on June 18, 1974, contending

(1) that, any claim for attorneys' fees from the institution of

this action until the Order of September 19, 1973 had been

finally determined and was barred by res judicata, since plaintiff

failed to appeal from that Order; (2) that plaintiffs were barred

by the doctrine of collateral estoppel from an award of attorneys'

fees; and (3) that this is a case in which the District Court

should, in its discretion, deny attorneys' fees, because "special

circumstances would render such an award unjust" since the Board

has acted in good faith throughout the litigation, and had

discharged its constitutional responsibility at the .time Section

718 was enacted (A- 70-80).

The District Court's Ru1ing

On October 31, 1974, the District Court denied plaintiffs

any award, of attorneys' fees (A. 81-88) for the following

reasons; (1) the September 19, 1973, Order granting plaintiffs

costs and counsel fees pursuant to the Fourth Circuit mandate

was "then considered to have . . . finally resolved . . . all

claims [for fees] from the filing of this action through June 11,

1973" (A. 84); (2) at no time "prior to June 4, 1974, during the

long history of this litigation . . . have plaintiffs' counsel

specifically and seriously asserted any claim of entitlement to

attorneys' fees for services rendered from the date of filing of

this action to the 'effective date of the Emergency School Aid Act

11

of 197 2 (July 1, 1972)" (A. 84); (3) the interests of justice

did not require the court, in the exercise of its equitable

powers, to award attorneys' fees (A. 85); (4) Section 718 as

construed in Bradley is applicable only to a situation where

the propriety of a fee award was pending resolution on appeal

when the statute became effective (A. 86); and (5) even if

Bradley extended § 718 to cases in which the fee issue was

never litigated before enactment of § 718, it would be manifestly

unjust to apply the statute to this case (A. 87).

On November 26. 1974, plaintiffs filed Notice of Appeal from

the District Court's ruling (A. 91).

12

ARGUMENT

I

SECTION 713 REQUIRES THE AWARD OF-COUNSEL

FEES IN THIS CASE AND THERE ARE NO SPECIAL

CIRCUMSTANCES PRESENT IN THIS CASE WHICH

WOULD RENDER AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS ' FEES

UNJUST

Section 718 of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1617, represents an intentional Congressional departure from

the traditional American rule refusing to include counsel fees

5/

as part of the recoverable costs of litigation. The statute

was intended to enlarge the circumstances in which federal

district courts would exercise their inherent equitable power

6 /

tO ci'WciJrci 1. £rC S / l}0yoriCi the tradit iona.1 IGX'muiatxon requrrmg

y"obdurate and obstinate" conduct by school boards. See, Hearings

Before the Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational

Opportunity, 91st Cong., Part B, pp. 1516-34; 114 Cong. Rec.

10760-64, 11339-45 (Sen. Mondale); 117 Cong. Rec. .11343, 1.1521

(Sen. Coo].) .

The United States Supreme Court, in North cross v. Board, of

Educ. of Memphis, 412 U.S..427, 428 (1973), held that under §718

5/ See, e.q. Goodhart, Costs, 38 Yale L. J. 849 (1929); Sprague

v. Ticonic Nat'l Bank, 307 U.S. .161 (1939); F . D. Rich Co., Inc.

v * Industrial Lumber Co., 417 U.S. 116 (1974).

6/ Sprague v. Ticonic Nat’l Bank, supra, 307 U.S., at 164.

7/ E. g ., Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan County, 321 F.2d 494

(4th Cir. 1963).

13

"the successful plaintiff 'should ordinarily recover an attorney's

fee unless special circumstances would render such an award

8/

unjust.'" And in Bradley v. School. Bd. of Richmond, 416 U.S.

696 (1974), a year later, the Court indicated that Section 718

should be given retrospective application, at least where the

counsel fee issue had not been finally determined, to authorize

the recovery of attorneys' fees for services performed prior to

its effective date (July 1, 1972).

In the instant case, all of the statutory requirements are

9/

met, and there are no special

denial of fees. Final orders h

implementing desegregation ana

circumstances which would warrant,

ave been entered in the case

tlixs j_s an ap]32roj3iriati0 j u.ric Jcu tg

8/ See si Iso i Thompson v. School Bd, of Newport. News, 472 F.2d

177 (4th Cir. 1972).

9/ Section 718 states:

Upon entry of a final order by a court of

the United States against a local educational

agency, a state (or any agency thereof), or

the United States (or any agency thereof) for

failure to comply with any provisions of this

chapter or for discrimination on the basis of

race, color or national origin in violation cf

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or

the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution

of the United States as they pertain to ele

mentary and■secondary education, the court, in

its discretion, upon a finding that the pro

ceedings were necessary to bring about compliance,

may allow the prevailing party, other than the

United States, a reasonable attorney's fee as part

of the costs.

14

■ 10/

for the determination and award of fees.

The appellee Board of Education has contended that the

circumstances of the instant case would render an award of

11/

attorneys' fees unjust. The Board contends that this case

is different from Bradley, supra, in that there has been nc

finding of an equitable ground for the award of fees; the Board

points to its apparent good faith and the findings of the

district, court on June 25, 1970, that the school system, in

general, was a unitary one (A. 79). But whether the Court would

be warranted in finding undue obstinacy on the part of the

defendants is not the issue here. The Supreme Court, in Bradley

makes clear that such inquirv is not necessary. All that is

required is that plaintiffs obtain a final order against defendants

enjoining their violation of rights secured by the Constitution

12/

and laws of the United States. This the plaintiffs have done.

10/ It should be noted that under the statute, courts need not

render the counsel fee award simultaneously with the underlying

final order, Bradley, supra, 416 U.S., at 722-23, On the other

hand, the court need not await ultimate dismissal of the lawsuit

to enter judgment for fees and costs, but may "award fees and

costs incident to the final disposition of interim matters," id.

at 273; see also, Smith v. North Carolina State Bd, of Educ., No.

2572 (E.D.N.C. Sept. 26, 1974)

11/ We deal below (Arguments II and ill) with the separate

questions whether, despite the fact that this case meets the

requirements of § 718, a claim for attorneys' fees in this case

is barred because the Statute is inapplicable or because of the

doctrine of res judicata.

12/ See also Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 356 F. .Supp. 18, 25

(N.D. Cal. 1973).

15

The Board's reliance on the District Court's June 25, 1970

13/decision declaring the system a unitary one is misplaced: That

decision, which would have left 70 percent of the students

segregated, was reversed by this Court on June 10, 1971, with

instructions to the District court that it receive new plans

which would give effect to the Supreme Court decisions of Swann

v . Chari otv.e-Mcchlenburq Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971) and

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33 (1971).

After a plan substantially desegregating the schools was accepted

by the district court, the Board attempted to resubmit proposed

modifications which would have resegregated more than 70 percent

q-F f' hp 1 earnpr'i" r-> rw g rpopu hc 9.+* t ©rP.'P't Jr W02T6** rO^Ctcd ]?V

District Court and by this Court,' and it was only after these

attempts had failed that the Board finally assented to desegre

gation.

The Board curiously contends that it was only because

of its efforts "to vacate the court's previous orders requiring

implementation of [the revised 1971-72 pupil assignment plan]

. . . that the opportunity for plaintiffs to bring up the question

of attorney's fees before the Court of /appeals arose" (A. 79)."

13/ . In Bradley, this Court had reversed the district court's

award of fees in part because it. felt the school board's failure

to anticipate Swann was justifiable. 417 F .2d 318, at 327. The

Supreme Court held this inquiry irrelevant to § 718. 416 U.S., at

721.

16

Implicit in this statement is the belief that the present action

v/ould have terminated and been dismissed if the Board had

chosen initially to assent to the revised plan. That is

simply untrue in school desegregation cases. The District Court

was required to retain jurisdiction in order to insure that a

unitary system is actually maintained and established. Raney v.

Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968). The proceedings

had not yet been concluded on the effective date of Section 718,

and the district court still retains jurisdiction of this case.

See note 10, supra.

The Board's assertion (A. 79) that its actions in

litigation might nave been different if it had known xt

subjecting itself to liability for counsel fees is equa

thi s

was

L4/baseless. This apparent concern with liability for counsel fees

which the Board asserted below is in sharp contrast to its

response to plaintiffs' 1973 motion for appellate counsel fees.

In its June 18, 1973, letter to the District Court Clerk, the

Board indicated that it would not respond formally to plaintiffs'

motion, and that it would assent to an award of counsel fees

which -would be "fair and reasonable under the circumstances"

(A. 56). Nor is it true, as the Board somewhat vaguely asserted,

14/ The District Court in its Memorandum notes that defendants,

during the period for which fees are now claimed, were attempting

to follow the law as they believed it to be (A. 87). Assuming that

the law was unclear during this period, such a ground is insufficien

(continued on next pace)17

that the matter cf counsel fees comes as a complete surprise

to it. Since the inception of this case plaintiffs have repeatedly

15/

pressed their claim for counsel fees. Surely the defendants

14/ (Continued)

to warrant a court in denying counsel fees. See Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, 3 90 U.S. 400 (1968) ; Moody v. Albemarle Paper

Co. / 474 F.2d 134,, 140-42 (4th Cir. 1.973); Pe’ctway v. American Cast

Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 251-63 (5th Cir. 1974); Baxter v. * 1 2 3

Savannah Sugar Refining Corp. , 495 F.2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974).

See also, note 13, supra.

15/ Since both the Board and the District Court have maintained

that, plaintiffs never seriously pressed a claim for counsel fees

for the 1968-72 period (A. 34), it would be helpful to outline the

instances in which this claim has been asserted and renewed. The

initial request for attorneys' fees in this action was made in the

complaint filed on October 2, 1968 (A. 29) and Amended Complaint

pT ion y-p-no i o , i ggg (\, 46^ , <p^prp?ft6r thi« perniest was renewed

in the following documents:

(1) Plaintiffs 1 Supplemental Memorandum dated

May 8, 1970;

(2) Appellants' Brief to the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit dated May 16, 1971

(3) Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Proposed

Modifications of the Desegregation Plan Approved

by the Court on July 26, 1971, dated April 12,

1972.

None of these requests was formally acted upon. Denial of

prayers for fee awards is not lightly inferred from substantive

decrees which are silent cri the subject, Sprague v. Ticonic Nat' 1

Bank, 307 U.S. 161, 168-69 (1939); Allegrini v. DeAngelis, 68 F.

Supp. 684 (E.D. Pa. 1946), aff'd 161 F.2d'184 (3d Cir. 1947); thus,

plaintiffs' claim for attorneys' fees for the period October- 2,

1968 to June 30, 1972 was pending before the district court on

July.l, 1972, the effective date of Section 718.

18

have been aware of the claim. Here, as in Bradley, 416 U.S., at

721, there is no tenable ground upon which to suppose that an

earlier and firmer apprehension by the school board would have

resulted in any more rapid termination of this lawsuit..

Nor is the application of Section 718 an additional and

wunforeseen! burden which might operate as an injustice. See

Bradley, supra, 416 U.S., at. 716-21. Plaintiffs admit that other

school boards may be insulated from the application of Section

718 to support an award of fees for services prior to its

effective date, when the right to such an award at earlier stages

of a case was actually litigated to judgment (and appellate review)

under the "obdurate—obstinate" standard prior to the passage of

U Jthe statute. But the mere fortuity that plaintiffs' entitlement

16/ Prior to the passage of Section 718 the district court could

have relied on alternative rationales to support a fee award in

this suit: (a) the benefit doctrine, e_._cr., Ha 13. v. Cole, 412 U.S.

1 (1973); Mills v. Electric Jratolite C o ., 396 U.S. 375 (1970); (b)

the "private attorney-general" theory, e.g., Sims v. Amos, 340 F.

Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala), aff'd 409 U.S. 942 (1972); Incarcerated Men

of A llen County v. Fair, No. 74-1052 (6th Cir., Nov. 13, 1974); case

cited in Gates v. Collier, 489 F.2d 298, 300 n. 1 (5th Cir. 1973),

pending on petition for rehearing en banc; in other words, the

Board's potential liability for fees in this case was always present

3,7/ in Bradley, for example, plaintiffs received a $75.00 award

from the district court in 1964, which this Circuit refused to

overturn for inadequacy, 416 U.S., at 699-700. The Supreme Court

did not decide that Section 718 should be applied retroactively to

tlie extent of reopening this judgment, which had ultimately

determined plaintiffs* 1 rig}!t to fees for an ear3.ier portion of the

litigation — a question which the Court said was not presented to

(continued on next page)

- 19 -

to a counsel fee award in this case, for which plaintiffs had

made claim in their original Complaint, had not been litigated

prior to the effective date of Section 718, does not create an

injustice to the defendants should it be litigated now.

IT.

THE DOCTRINES OF RES JUDICATA, WAIVER AND

ESTOPPEL ARE INAPPLICABLE TO THIS CASE

BECAUSE THE ISSUE OF COUNSEL FEES WAS

PENDING ON BOTH THE EFFECTIVE DATE OF

SECTION 718 AND ON THE DATE WHEN PLAIN

TIFFS MOVED FOR COUNSEL FEES INCURRED

FROM OCTOBER 1968 TO JUNE 1972

A. Plaintiffs have repeatedly pressed their claim to

counsel fees and have not waived the claim during

the coup'se or Lhrs litigalxon.______________ -______

Contrary to the District Court's October 31, 1974, Memorandum,

plaintiffs have specifically and seriously asserted and renewed

a claim for fees for services rendered prior to the effective

date of Section 718 in this case. On at least four occasions

plaintiffs moved the District Court and this Court for fees

incurred during the period in question. See note 15, supra .

While these four motions were made prior to the effective date of

17/ (Continued)

it in Bradley. 416 U.S., at 710-11 and n. 14. (The Court

indicated in a footnote, however, that even that question could

not be definitively answered in the abstract, but only upon

consideration of the particular circumstances of each case. Ip•>

at 711 n. 15.)

20

Section 718, the failure of the District Court and of this

Court to.act upon these motions cannot be construed as a denial,

and the fact that plaintiffs did not appeal all orders entered

after the motions were made but which did not mention counsel

fees, in order to raise the issue before this Court or the

Supreme Court (by certiorari), is not a waiver of their claim

to counsel fees. The Supreme Court, in Bradley, explicitly

approved of the notion that substantive matters should come first,

with determination of collateral issues, such as entitlement to

attorneys' fees, postponed until a more convenient time. 416

U.S., at 722-23. See also, notes 10, 15, supra.

The Court's implicit assertion that plaintiffs' failure

continually to raise the issue of attorneys' fees at every stage

of the litigation somehow waives their right to such fees, simply

18/

has no merit. Not only has Bradley specifically rejected such

an assertion, see note 10, supra, but the general rule prior to

Bradley was that attorneys' fees need not be requested until after

w

the outcome of the litigation. Moreover, as noted above, the

18/ No such requests are necessary or warranted. At the

appropriate stage in the proceeding, the court would consider

plaintiffs' motion without an annual renewal. See generally,

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure, Section 2679

6 Moore's Federal Practice 54.77[9].

19/ See, e ..g. , Sprague v. Ticonic Nat'l Bank, supra, 307 U.S., at

168-69; Union Tank Car Co. v. Isbrandsten, 41.6 F.2d 96 (2d Cir, 1969)

Schwarz v. United States, 381 F.2d 6 27 (3rd Cir. 1967); Allegx-ini v.

DeAngelis, 68 F. Supp. 684 (E.D. Pa. 1946), aff'd 161 F.2d 184

(3rd Cir. 1947).

the

10

(1973);

21

r

denial of fees should not be lightly inferred.

The interim orders of the District Court and this Court

cannot on their face be construed as denials of plaintiffs'

motions for counsel fees. A similar argument with respect to

various orders during the course of school desegregation litiga

tion was rejected in Smith v. North Carolina Bd, of Eauc ., supra.

And even if one were to assume that the failure of the District

Court to award counsel fees and costs earlier was a denial, it

is clearly appropriate for the plaintiffs to await final dis-

position of the action before appealing. See Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Nduc., 402 U.S. at 6-8, 12-13.

B. Plaintiffs' Claim for an award of counsel fees for

the period prior to the effective date of Section

718 is not barred by the doctrine of res judicata

because the.District Court's September 19, 1973

order dealt only with counsel fees for an appeal

to this Court.______________________________________

Despite defendants' emphatic arguments to the contrary in

support of'their contention that plaintiffs' claim for counsel

fees was bari'ea by res judicata (A. 76-78)-- arguments apparently

not explicitly accepted by the District Court (see A. 84) —

20/

2.0/ See Sprague v. Ticonic Nat’l Bank, supra, 307 U.S., at

168-69; Allegrini v. DeAnqelis, supra. Cf. Union Tank Car Co.

v. Isbrandsten, supra, 416 F.2d, at 97; Schwarz v. United

States, supra, 381 F.2d, at 631.

22

the issue of plaintiffs' entitlement to an award of counsel fees

for the period from October 1968 to June 30, 1972, has not been

litigated and is not barred by principles of res -judicata. This

issue was still pending before the District Court when plaintiffs

moved for fees in June, 1974.

A review of the events leading to the District Court's

September 19, 1973, Order shows clearly that the Order fixed

counsel fees for a limited portion of this litigation, and was

not intended as a final resolution of plaintiffs' claim for

counsel fees for the entire case.

In its opinion issued April 30, 1973, this Court

stated:

The cause is accordingly remanded to the

district court to make reasonable allowance

for attorneys' fees in favor of the appellees

for services rendered herein by them subse

quent to June 30, 197 2 (A.’ 4 9).

The relief ordered by this Court must be considered in light

21/

of the plaxntiffs' prayers. In their Brief to this Court,

21/ Defendants' claims might'be more tenable had plaintiffs sought

from tliis Court in 1973 an award of fees for the entire litigation —

and been limited by this Court to an award of fees for the period

after the effective date of Section 718, in accordance with this

Court's interpretation of the statute's applicability at that time,

Thompson v . School Bd . of Newport News, supra. See Brewer v . School

Bd. of Norfolk, 500 F.2d 1129, 1130 (4th Cir. 1974) (appeal of

adequacy of limited fee award directed by this Court in 1972 when it

rejected §718 claims, 456 F -2d 943, remanded "wdth instructions to

determine and award to the plaintiffs such reasonable attorneys’ fees

as may be appropriate under §710 as construed by the Supreme Court

in Bradley . . . without limitation to what they did with respect to

the issue of free transportation").

23

plaintiffs requested an award of double costs and counsel fees

pursuant to Rules 38 apd 39 of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure, or an award of fees on the appeal pursuant to Section

718. This request for attorneys' fees related solely to services

rendered in connection with the appeal; in their brief plaintiffs

stated:

Additionally, Section 718 of the Emergency

School Aid Act warrants an award of counsel

fees and costs on this appeal. (emphasis

supp]led)

Thus, this Court never considered the question of the propriety

of counsel fees in connection with services performed in this

j rv~. if i ^ t ’O "tlVv2* I

On June 11, 1973, the plaintiffs moved in the District

Court for an award of counsel fees and for recovery of

their costs and expenses (A. 50-54). Plaintiffs’ motion

was made "pursuant to the Opinion and Mandate of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit" (A. 50);

as noted, this mandate concerned plaintiffs1 request for

counsel fees in connection with the appeal.

24 -

Iij its Order of September 19, 1973, the District Court

stated:

The Court is, however, at this time only

concerned with what is a reasonable allowance

for attorneys' fees for the preparation and

argument of an appeal from an order of this

Court (A. 65).

The above-quoted statement from the Order of September ]9

indicates that the District Court was aware of the limited

nature of plaintiffs' request to this Court for attorneys' fees.

lit j.s true that, plaintiffs' motion in the District Court

asked for costs from the inception of the case as well as tor

_ 22/ tees in connection wi th i o?1 ?nnr,ri ........

- j T -*- • XxKJ V tdj.. f Cv JL tor L> c i 3. U. b

■ costs, the Court merely approved the "Clerk's Memorandum and Order-

Taxing Costs" dated September 14, 1973 (A. 66), which itself

treated plaintiffs' motion, as a Bill of Costs required by Local

Rule 27(c) and taxed costs in favor of plaintiffs pursuant to

Rule 54(d) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (A.. 59).

Plaintiffs' motion for counsel fees, on the ether hand, was made

pursuant to the mandate of this Court, which related only to fees

22/ Plaintiffs' recovery of costs for the period of this litiga

tion prior to the appeal does not bar their request for counsel

fees. A subsequent request for an award of fees is not barred even wi

Supp.

cui dwara or rees is not barred e'

/here costs were previously taxed, Allegrlnl v. DeAnqelis, 68 F.

>upp. 684 (E.D. Pa. 1946) aff'd 161 F.2d 184 (3rd Cir. 1947).

25 -

in connection with the appeal. Therefore, the issue of the

propriety of fees for services prior to the appeal remained

"pending” before the District Court after the September 19, 1973

23/

Order was entered.

i i:

THE ERADLEY DECISION MAKES §718

APPLICABLE TO ALL CASES IN WHICH

THE ISSUE OF COUNSEL FEES WAS

PENDING RESOLUTION ON ITS EFFECTIVE

DATE, AND IS NOT LIMITED TO CASES

IN WHICH THE SPECIFIC ISSUE WAS

PENDING RESOLUTION ON APPEAL AT

(A. 85-66), that the statutory construction rule of Bradley

is applicable only to the situation where the propriety of a

fee award was pending resolution on appeal at the time Section

718 became law; and that Bradley is therefore inapplicable tc

this case. This position is clearly specious.

23/ While the District Court's September 19, 1973, Order may

be construed to indicate that the fees awarded were those to

which plaintiffs were entitled "under 718 of the Emergency School

Aid Act of 1972" (A^^64, 65), the Order plainly states that the

allowance of attorneys' fees is made pursuant to the mandate of

this Court (A. 65, 66). As noted, plaintiffs' request to this

Court for fees was limited to sendees in connection with the

appeal. This Court never decided the question of the propriety

of fees for the period' from October 1968 to June 30, 1972, a fact

which the School Beard necessarily recognized in its letter to the

District Court Clerk acknowledging that counsel fees would be

awarded pursuant to the mandate of this Court (A. 55-56).

Bradley described the .issue presented by the case as one

involving the applicabi.l itv of Section ? 18 to attorneys ’ fees

"incurred prior to" its effective date, 416U.S., at 710

(emphasis added). The Supreme Court indicated that its

resolution of this question required. its specific disposition

of Bradley — application of the statute so as to change the

result of a district court decree rendered prior to its effective

date, but pending on appeal at that date?

. . . The Board appealed from that award,

and its appeal was pending when Congress .

enacted §718. The question, properly viewed,

then, is not simply, one relating to the pro

priety of retroactive application of §718 [24/]

to services rendered prior to its enactment,

I v n 1' r r - j - V i n r n r ^ p y~f.s 1 ^ i •n r r f O f p n n l i f f h -' 1 ' i f ' ' , r

or that section to a situation where the

propriety of a. fee award was pending resolution

on appeal when the statute became law.

41G IT. S . at 710 (emphasis added),

24/ Application of the principle of statutory construction

enunciated in Bradley (and Thorpe and Schooner Peggy, relied

upon by the Supreme Court) to future district court awards for

past services is a simpler question than its application to

alter a district court judgment because it docs not implicate

the policy considerations relevant to prospective or retrospective

application. In the textual paragraph and notes following the

passage quoted, the Court referred to these additional consider

ations :

This Court in the past has recognized ct

distinction between the application cf a

change in the law that takes place while a

case is on direct review on the one hand, and

- 27 - (Continued on next page)

After distinguishing the circumstances of Bradley from

cases in which the Court might be asked to reopen "final"

adjudications in light of changes in law (see note 24, supra), •

the Court affirmed the principles which governed ins disposition

in the matter before it, and which must be applied here:

We anchor our holding in this case on the

principle that a court is to apply the law

in effect at the time it renders its decision,

unless doing so would result in manifest

injustice or there is statutory direction or

legislative history to the contrary.

Ibid Court concluded its discussion of the principles cf

statutory construction as follows:

2<i/ (Continued)

wits effect on a final judgment under

collateral attack,— '' on the other hand.

Linkletter v. W alker, 381 U . S «, G18, G27

(1965) . Wre are concerned here only with

direct review.

14/ By final judgment we mean on€2 where "the

availability of appeal" has been exhausted or

has lapsed, and the time to petition for

certiorari lias passed." Linkletter v. Walker,

381 U.S. 613, 622 n. 5 (1965).

15/ In Chicot County Drainage District v .

Baxter State Bank, 308 U.S. 371, 374 (1940),

the Court noted that the effect of a subsequent

ruling of invalidity on a prior final judgment

under collateral attack is subject, to no fixed

"principle of absolute retroactive invalidity"

but depends upon consideration of "particular

relations . . . and particular conduct." . . .

28 - (Continued on next page;

The availability of §718 to sustain the award

of fees against the Board therefore merely

serves to create an additional basis or source

for the Board's potential obligation to pay

attorneys’ fees. [See note 16 supra!. It does

not impose an additional or unforeseeable

obligation upon it.

416 u.;

Accordingly, upon considering the parties,

the nature of the rights, and the impact of

§718 upon those rights, it cannot be said

that the application of the statute to an

award of fees for services rendered prior to

its effective date, in an action pending on

that date, would cause "manifest injustice,"

as that term is used in Thorpe, so as to compel

an exception of the case from the rule of

Schooner Peggy ,

at 721 (emphasis added).

T n O c G ^ 3 6 '- d C S . v ' y*> v~ a r~- -i ^ 1 <o> C -^1 ̂ T 'T _ O ̂ **

Bradley? so long as a request for attorneys1 fees is properly

before a district court on the effective date of the statute,

whether or not an award is sought for services performed prior

to that time. Section 718 is to be applied, and requires the

Court to make an award of reasonable" attorneys* fees unless there

are "special circumstances which would render such an award unjust."

24/ (Continued)

The Court held that the statute would be given retrospective

application in Bradley to alter a judgment pending on appeal on

its effective aa.te (although, as set forth in the passages quoted

in this note, the Court did not pass upon the possibility that §718

could be applied to reopen "final" judgments). A fortiori, the

statute is to be applied in cases such as the instant one, in which

there had never been an adjudication of plaintiffs* claim for counsel

fees prior to the effective date of the statute.

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the District

Court should be reversed and the cause remanded, as in Brewer,

supra, "with instructions to determine and award to'the

plaintiffs . . . reasonable attorneys’ fees" for the period

from the inception of this action until the effective date of

§718.

Respectfully submitted,

m m .

beVOfTNI r.lIAMBERS

:hambers, Stein & Ferguson

.951 S. Independence Boulevard

Char]of te M'rth carolin? 78^02

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellant

30

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 25th day of February,

1975, I served two copies of the Brief for Appellants in the

above-captioned matter upon counsel for the parties herein,

by depositing same in the United States mail, first class

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

William F. Maready, Esq.

P. 0. Box 2860

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27102

Hon. Andrew A. Vanore, Jr., Esq.

P. 0. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

P. Eugene Price, Jr., Esq.

G c v e iji i i ie n l. Cg iic.c:ir

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27101

31