Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Brief for Petitioner, 1973. 1163b6ae-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2eb3f602-c282-4206-b56a-dea5bc10fa42/bradley-v-state-board-of-education-of-virginia-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

C a ro s i

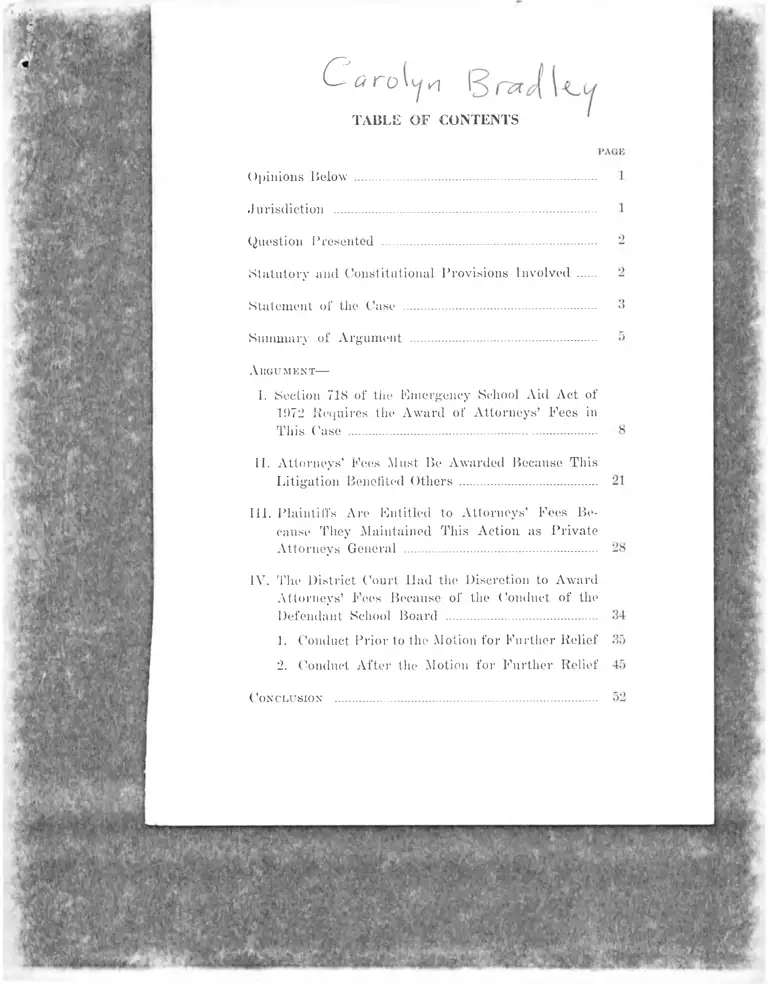

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions Below ................................................................

Jurisdiction .....................................................................

Question Presented .........................................................

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved .....

Statement of the Case ...............................-...................

Summary of Argument —...............................................

A r g u m e n t —

I. Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of

1972 Requires the Award of Attorneys’ Fees in

This Case ............................................... ..................

II. Attorneys’ Fees Must Be Awarded Because This

Litigation Benefited Others ....................................

III. Plaintiffs Are Entitled to Attorneys’ Fees Be

cause They Maintained This Action as Private

Attorneys General ...................................................

IV. The District Court Had the Discretion to Award

Attorneys’ Fees Because of the Conduct of the

Defendant School Board ...................................... .

1. Conduct Prior to the Motion for Further Relief

2. Conduct After the Motion for Further Relief

Conclusion

PAGE

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 390

IJ.S. 19 (1909) ........................................................................ 41

American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City Cent. Trades

Council, 257 IT.S. 184 (1921) ..... .............................. 12-13

Arcambel v. Wisemam, 3 U.S. (3 Dal.) 300 (1790) ...... 32

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, 382 F.2d 320 (4th Cir. 1907) ......................... 37

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia, 345

F.2d 310 (1905) .......................................................... 3,41

Bradley v. State Board of Education, No. 72-550 .......... 24

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Vir

ginia, 450 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1972) .......... .................. 35

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....25,29

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 303 (1904) ..................... 41

Callahan v. Wallace, 422 F.2d 59 (5th Cir. 1972) .......... 24

Carpenter v. Wabash Railway Co., 309 U.S. 23 (1940) 12

Central Railroad and Banking Co. v. Pettus, 113 U.S.

110 (1885) ................................................................... 22

Cheff v. Schrackenberg, 384 U.S. 373 (1900) ................ 33

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S.

402(1971) ................... 14

Claridge Apartments Co. v. Commissioner, 323 U.S.

141 (1944) ................................. 14

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School Dist.,

449 F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971); 309 F. 2d 601 (8th Cir.

1900) ............................................................................. 36

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1952) ............................. 40

Cooper v. Allen, 407 F.2d 830 (5th Cir. 1972) ................ 28

Cox v. Hart, 200 U.S. 427 (1922) ...................... ...... 13-14

Ill

PAGE

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968) ................................ 30

Fleischmann Distilling Corp. v. Maier Brewing Co.,

386 U.S. 71+ (1967) ........................................... 22,26,3+

Ford v. White, (S.D. Miss., Civil Action No. 1230(N)....2+, 28

Goldstein v. California,+1 IJ.S.L.W.+829 (1973) .......... 13

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ...... +1

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 ............................................. +, 7, 37, +0-41-+2

Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 1+9 (1963) .............. 14

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (196+) ................ 41

Hall v. Cole, 36 L. Ed. 2d 702 ................... 6, 23, 26, 28-29-30

Hammond v. Housing Authority, 328 F. Supp. 586 (D.

Ore. 1971) ..................................................................... 2+

Horton v. Lawrence County Board of Education, 4+9

F.2d 393 (5th Cir. 1971) ............................................. 35

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (196+) ......................... 20

Jinks v. Mays, 350 F. Supp. 1037 (N.D. Ga. 1972) .....24,28

Johnson v. United States, 163 F.2d 30 (1st Cir. 1908) .... 13

Kelly v. Guinn, +56 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972) ..............

Knight v. Aueiello, 453 F.2d S52 (1st Cir. 1972) ..........

La Baza Unida v. Volpe, 57 F.R.D. 9+ (N.D. Cal. 1972)

Lee v. Southern Home Sites, 4+4 F.2d 1+3 (5th Cir.

1971) ..................................................................... 27,28,

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) .....................

36

28

28

20

McDaniel v. Barresi,+02 U.S. 39 (1971) ..................... 41,42

McEnteggart v. Cataldo, 451 F.2d 1109 (1st Cir. 1971) 35

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970) ....21-22,

24, 29

IV

PAGE

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of City of Jackson,

453 F.2d 259 (6th Cir.) ......................... ' ..................... 35

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ............................. 32

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972) ....27-28

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ......................... 33

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ................................................................. 7,9,28,34

Newman v. State of Alabama, 349 F. Supp. 278 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) ................................................................... 24, 28

Newton v. Consolidated Gas Co., 265 U.S. 78 (1924) .... 35

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis City

Schools, 41 U.S.L.W. 3635 (1973) ..................... 5,9, 28-29

Reynolds v. United States, 292 U.S. 433 (1934) .......... 13

Ross v. Goshi, 35 F. Supp. 949 (D. Hawaii 1972) ...... 27, 28

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) .......... 33

School Board of the City of Richmond, Virginia v.

State Board of Education, No. 72-549 ......................... 24

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972) ....24, 27-28

Sincoek v. Ohara, 320 F. Supp. 1098 (D. Del. 1970) ...... 24

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161

(1939) ......................................................................... 21-22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

431 F.2d 138 (1970) .....................................8,41,42,48

Thompson v. School Board of the City of Newport

News, 472 F.2d 177 (1972) ........................................S, 18

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

0969) ..................................................................... 5,12,14

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409 U.S.

205 (1972) ................................................................... 25

Trustees v. Greenough, 105 U.S. 527 (1883) ...................22,24

V

PAGE

Union Pacific Railroad Co. v. Laramie Stock Yards, 231

U.S. 190 (1913) ............................................................ 13

United States v. Alabama, 362 U.S. 602 (1960) ............ 12

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Crancli)

103 (1801) ................................ 11,13

Vanderbark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Company, 311 U.S.

538 (1941) ................................................... 12

Wyatt v. Stickney, 344 F. Supp. 387 (M.D. Ala. 1972) .... 28

Yablonski v. United Mine Workers of America, 466

F.2d 424 (D.C. Cir. 1972) ........................................... 24

Ziffrin v. United States, 318 U.S. 73 (1943) .................. 12

Statutes:

15 U.S.C. §78(a) ............................................................ 23

15 U.S.C. §1116 .............................................................. 27

15 U.S.C. §1117 97

18 U.S.C.

28 U.S.C.

28 U.S.C.

28 U.S.C.

42 U.S.C.

42 U.S.C.

42 U.S.C.

42 U.S.C.

42 U.S.C.

§245 (b) (2) (A)

§1254(1) ......

§1331 ............

§1343 ............

§1983 .............

2000a .............

§2000c-6 .........

§2000c-8 ........

§2000d-l .........

............. 29

....... ..... 1

O............ o

.......... -3,31

2, 3, 6,21,31

.............. 20

............ 29

........... 27-28

............ 30

VI

PAGE

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 ......................................................... 20

42 U.S.C. 3612(c) .......................................................... 20

Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1966 ...... 30

Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 ..................2, 8,16, 30

Jury Selection Act of 1968 ........................................... 11

Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure A c t...... 31

Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ................................23,31

Other Authorities:

Sen. Rep. No. 92-61, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess.................... 16-17

Conference Rep. No. 79S, 92nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1972) 16

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the

Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee, 92nd

Cong., 1st Sess. 99 (1971) ........................................ 17,19

S.683, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess............................................ 16

114 Cong. Rec................................................................... 17

117 Cong. Rec...................................................15-16-17-18-19

Moore’s Federal Practice ....................... 10

Coleman, et ah, Equality of Educational Opportunity

(1966) ........................................................................... 25

Stone, “The Common Law in the United States”, 50

Harv. L. Rev. (1936) ................................................... 33

IJ.S. Civil Rights Commission, Racial Isolation in the

Public Schools (1967) ............................................... 25

I n t h e

§>upnmtr (Enurt nf tlip I hUpii

October Term, 1973

No. 72-1322

Carolyn B radley, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T he S chool B oard of the City of R ichmond, et at.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

O pinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 472

F.2d 318 and is set out in the Appendix (160a-193a). The

opinion of the District Court is reported at 53 F.R.D. 28,

and is set out in the Appendix (113a-145a).

Other opinions of the District Court, not dealing with

the question of attorneys fees, are reported at 317 F. Supp.

555, 325 F. Supp. 828, and 338 F. Supp. 67.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit was entered on November 29, 1972. On February

21, 1973, Mr. Chief Justice Burger ordered that the time

for fding a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in this case be

extended to March 29, 1971. The Petition was tiled on

March 29, 1971 and was granted on June 11, 1973. This

Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Q uestion Presented

Did the District Court have the discretion to award

attorneys’ fees to successful plaintiffs in this school de

segregation action?

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution provides:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and of the States wherein they re

side. No State shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.

Section 1983, 42 United States Code, provides:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution

and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an

action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceed

ing for redress.

Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972,

86 Stat. 235, provides:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the

United States against a local educational agency, a

3

State (or any agency thereof) or the United States

(or any agency thereof), for failure to comply with

any provision of this title or for discrimination on the

basis of race, color, or national origin in violation of

title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the four

teenth amendment to the Constitution of the United

States as they pertain to elementary and secondary

Education, the court, in its discretion, upon a finding

that the proceedings were necessary to bring about

compliance, may allow the prevailing party, other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part

of the costs.

Statement o f the Case

This case was commenced in 1961 to desegregate the

public schools of Richmond. Jurisdiction was claimed,

inter alia, under 28 U.S.C. §1343 to enforce 42 U.S.C. §1983,

and under 28 U.S.C. §1331 to enforce the Fourteenth

Amendment, the amount in controversy exceeding $10,000.

Jurisdiction was conceded by the defendant school board.

In March, 1964, after extended litigation, the District

Court approved a “freedom of choice” plan proposed by

the defendant school board. Plaintiffs appealed to the

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the lower

court’s finding that freedom of choice satisfied the school

board’s constitutional obligations. Bradley v. School Board

of Richmond, Virginia, 345 F.2d 310 (1965). Plaintiffs

then petitioned this Court for a Writ of Certiorari to con

sider the constitutionality of the freedom of choice plan.

On November 15, 1965, this Court declined to review the

Fourth Circuit’s decision regarding freedom of choice, but

did grant plaintiffs certain additional relief regarding dis

crimination in the assignment of teaching personnel. 382

U.S. 103.

4

Plaintiffs also sought attorneys’ fees for this phase of

the litigation. The District Court refused to award legal

fees except for one $75.00 allowance, and the Fourth Cir

cuit aflirmed the denial. 345 F.2d at 321. For the litigation

prior to this decision of the Fourth Circuit the school board

had paid their outside counsel $6,580.00 (103a).

On March 30, 1966 the District Court approved a freedom

of choice plan submitted by the parties. The plan expressly

stated that freedom of choice would have to be modified if

it did not produce significant results (20a-24a).

On May 27, 1968, this Court ruled that freedom of choice

plans were not constitutionally permissible unless they

actually brought about a unitary school system. Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430.

On March 10, 1970, plaintiffs moved in the District Court

for additional relief under Green. The defendant school

board conceded that the freedom of choice plan under which

it had been operating was unconstitutional. After consider

ing a series of alternative and interim plans, the District

Court on April 5, 1971, approved a plan for the integration

of the Richmond schools involving pupil reassignments

and transportation only within the city of Richmond. 325

F. Supp. 828. The defendant school board took no appeal

from that decision.1

On August 17, 1970, the District Court directed the

parties to attempt to reach agreement on the matter of

attorneys’ fees. When the parties were unable to reach

such an agreement, memoranda and evidentiary material

were submitted to the court. On May 26, 1971, the District

Court awarded plaintiffs attorneys’ fees of $43,355.00 as

1 The defendant City Council of Richmond filed a notice of

appeal from that decision on April 29, 1971, but on the motion of

the City Council that appeal was dismissed on May 13, 1971.

5

well as costs and expenses of $13,064.65. On appeal the

Fourth Circuit, Judge Winter dissenting, reversed the

award of attorneys’ fees.2

Summary o f Argument

I. Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972

authorizes the award of counsel fees to a successful plain

tiff in a school desegregation case. Such fees must be

directed in the absence of special circumstances rendering

such an award unjust. North-cross v. Board of Education

of Memphis City Schools, 41 TT.S.L.W. 3635 (1973). No

such special circumstances are present in this case.

Section 718 should he applied to all cases pending on

appeal as of the date it became effective, July 1, 1972. The

general rule followed by this Court is that changes in the

laAV are applied to all cases pending on appeal when the

change occurs. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

393 TT.S. 268 (1969). The only exception to that rule is

where the application of the new statute to events occurring

before its enactment will result in manifest injustice. The

award of counsel fees under section 718 in this case would

in no way be unfair to the defendant school board. On

the contrary, such an application of section 718 would

carry out Congress’s desire that school boards which vio

late the law pay the attorneys’ fees of private citizens forced

to sue to obtain their rights.

TI. This Court has expressly sanctioned the award of

attorneys’ fees where a successful litigant wins relief which

benefits others and where the award will serve to pass the

2 Although the school board’s notice of appeal mentions the

awards of both attorneys’ fees and costs, only the matter of attor

neys’ fees was briefed, and the Fourth Circuit’s decision does not

deal with the costs.

6

cost of that litigation on to the other beneficiaries. Unit

v. Cole, 36 L. Ed. 2d 702. Such an award of counsel foes

is made, not to penalize the defendant, but to assure that

those who desire benefits from the litigation are not un

justly enriched thereby.

The instant plaintiffs, by desegregating the schools of

Richmond to the extent possible within the city, conferred

a substantial benefit on all the students affected. Since

the funds of the defendant school board are held for the

rise and benefit of those same students, an award of counsel

fees against the school board serves to pass the cost of this

litigation on to those other beneficiaries.

III. Plaintiffs maintained this action, not merely on

their own behalf, but to vindicate important statutory and

constitutional policies. The school integration achieved by

the instant case benefits, not merely the students immedi

ately affected, but the public at large. Such litigation also

benefits the defendant school board, whose first interest

and obligation is to comply with the Constitution. Where

private litigants enforce important statutory or constitu

tional provisions and thus benefit the public, they are

entitled to legal fees under the rationale of Hall v. Cole,

just as they would be for a benefit conferred upon a smaller

ascertainable group.

Courts of equity traditionally fashion new remedies to

solve problems not adequately dealt with at law. The pro

liferation of important national policies enforceable only

through private civil litigation is such a problem, for the

cost of such litigation generally exceeds the benefit to any

individual plaintiff. The award of counsel fees to make

possible such litigation by private attorneys general car

ries out equity’s policy of seeking to do complete justice

in any case, and accords with provisions of 42 U.S.C. §1983,

7

broadly authorizing actions to “redress” deprivation of

constitutional rights. Compare, Newman v. Piggie Parle

Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

IV. Plaintiffs are entitled to counsel fees because of

the defendant school board’s conduct.

1. Prior to this latest round of litigation, the District

Court in 1966 directed the establishment of a plan involv

ing freedom of choice. In 1968 this Court declared such

plans illegal where, as here, they did not in fact result in

desegregation. Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430. Despite the illegality of

Richmond’s freedom of choice plan, and although the defen

dant school board must have been aware of Green, the

board obstinately persisted in operating that unlawful plan

for two years until brought back into court by plaintiffs.

The District Court correctly found there was no justifica

tion for the board’s decision to continue operating a system

which they conceded was unconstitutional, and thus forc

ing plaintiffs to resort to private civil litigation. Under

those circumstances the award of counsel fees was well

within the District Court’s discretion.

2. The award is also justified by the conduct of the

board in proposing to the court two manifestly inadequate

plans of desegregation in the spring and summer of 1970.

The legal services for which fees were awarded to plain

tiffs were rendered in opposing these two plans. The first

plan, proposed in May 1970, would have left two-thirds

of Richmond’s schools overwhelmingly white or overwhelm

ingly black. The second plan, of July 1970, would have left

a substantial number of overwhelmingly white or black

high schools and middle schools, and placed about half the

black students and half the white students in such segre

gated elementary schools. Both plans were clearly inade

quate under the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 431 F.2d 138

(1970). The District Court clearly had the discretion to

award counsel fees to plaintiffs for legal services rendered

in opposing these two plans.

ARGUMENT

I.

Section T ill o f the Em ergency School Aid Act o f

1 9 7 2 Requires the Award o f Attorneys’ Fees in This

Case.

While this case was pending before the Court of Appeals,

Congress enacted the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972.3

Section 718 of that Act provides:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United

States against a local educational agency, a State (or

any agency thereof), or the United States (or any

agency thereof), for failure to comply with any pro

vision of this title or for discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in violation of title

V I of the Civil Rights Act of 15)64, or the fourteenth

amendment to the Constitution of the United States as

they pertain to elementary and secondary education,

the court, in its discretion, upon a finding that the

proceedings were necessary to bring about compliance,

3 This development was brought to the court’s attention, but the

Fourth Circuit ruled that section 718 was not applicable to the in

stant. case. In its opinion in the instant case the Court of Appeals

held that there was no final judgment to which the award of fees

could be connected (187a-188a). In a companion ease, Thompson

v. School Board of Newport News, 472 F.2d 177 (1972), the court

held that section 718 only authorized legal fees for work done after

the effective date of the statute, July 1, 1972."

may allow the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs.

Section 718 is applicable to the instant case, and requires

the award of attorneys’ fees.

This Court has already held that, in cases falling under

Section 718, the successful plaintiff “should ordinarily re

cover an attorney’s fee unless special circumstances would

render such an award unjust.” Northcross v. Board of

Education of the ’Memphis City Schools, 41 U.S.LAV.

3635 (1973) ; compare Newman v. Piggie Parle Enterprises,

Inc., 390 II.S. 400 (1968). No such special circumstances

are present in the instant case. The District Court ex

pressly inquired whether there were special circumstances

which might render an award unjust, citing the standard

in Newman, and found there were not. 140a. The Court of

Appeals noted that the award of attorneys’ fees under the

Newman standard were “either mandatory or practically

so,” 183a, but did not expressly decide whether the Newman

standard had been met. The only circumstance in this case

which the Court of Appeals felt militated against legal

fees was its conclusion that, in view of the alleged uncer

tainty as to the constitutional requirements, the various

defenses and plans put forward by the school board, though

legally insufficient, were not advanced for purposes of

delay or in bad faith. 177a. Such good faith, however, has

been expressly held not to fall within the narrow category

of special circumstances permitting the denial of attorney’s

fees in these cases. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 401 (1968). There is of course no ques

tion that the instant action was necessary to bring about

compliance. The school board was in violation of the Dis

trict Court’s 1966 decree and of the decisions of this Court,

and made no pretense that it would change its ways other

than under court order.

10

Section 718 further requires that legal fees may be

awarded “upon the entry” of a final order against a de

fendant school board based on a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment or certain statutes. The quoted phrase does

not require, of course, that the award of legal fees be

simultaneous with the entry of such an order, but makes

the existence of such a final order a prerequisite to the

award of attorneys’ fees. Several such orders had been

entered and became final prior to the award of attorneys’

fees in this case on May 20, 1971.4 Where, as here, the

course of litigation in a district court involves the entry

of several orders over a period of months or years, neither

section 718 nor sound judicial administration require that

the question of legal fees be litigated separately and repe-

titiously upon the occasion of each such order. A request

for fees may present difficult questions of fact or require

the taking of evidence which might interfere with a court’s

simultaneous efforts to dismantle a dual school system.

Costs, of which attorneys’ fees are made a part by section

718, are normally imposed after the final disposition of

the case. Doubtless a District Court has discretion to

award costs and attorneys’ fees incident to the disposition

of interim relief matters, f> Moore’s Federal Practice

j[54.70[5], and it would be particularly desirable to exercise

that discretion where, as is common in litigation under

Brown, the fashioning of effective relief occurs over a

period of years and delay in awarding fees and costs may

work hardship on plaintiffs or their counsel. That discre-

4 On June 20, 1970, the District Court ordered a suspension of

all school construction in Richmond pending the approval of a

final plan. On August 17, 1970, the District Court ordered into

operation an interim plan for the 1970-71 school year. On April 5,

1971, the District Court ordered into operation the plan under

which the Richmond schools are now operating. Each of these

orders had become final when the attorneys’ fees were awarded on

May 20, 1970.

11

tion, however, exists for the protection of the plaintiff and

his attorney; a defendant cannot be heard to complain if

it is not so exercised.6

The defendant school board maintains, however, that

section 718 should not be applied to the instant case because

the legal services for which fees are sought were rendered

prior to July 1, 1972, the date on which section 718 became

effective.6 Plaintiffs contend that section 718 should be

applied to any case in which the propriety of an award

of legal fees was still pending resolution on appeal as of

July 1, 1972, regardless of when the services were per

formed. This case does not present the question of whether

section 718 should be applied, retroactively, to cases in

which the question of legal fees had been presented and

been resolved by a final order prior to July 1, 1972.

Since United States v. Schooner Peggy, this Court has

recognized that “if, subsequent to the judgment, and before

the decision of the appellate court, a law intervenes and

positively changes the rule which governs, the law must

be obeyed, or its obligation denied.” 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103,

5 Tin* Court of Appeals refused to apply section 718 to the in

stant case on the ground, inter alia, that on the effective date of

the Act there was no final order regarding the substantive claim

of discrimination pending on appeal (187a-188a). This standard,

in the sense it was used, could never be met, for no order could

be both final and also pending on appeal. If, as plaintiffs contend,

section 718 should apply to services performed prior to July 1,

1972, there is no precedent for requiring that such fees be arbi

trarily denied because of the date on which an order was entered

directing the desegregation of a defendant school district.

6 The date on which a law becomes effective is not the same

thing as the date from which the law shall apply. The former date

describes the time at which the courts will begin to invoke the

law in dealing with events or transactions; the latter date delimits

the class of events or transactions as to which that law may be

invoked. For an example of a statute specifying both effective

date and the transactions to which it applied, see section 104 of

the Jury Selection Act of 1968, Pub.L. 90-274.

12

106 (1801). This Court has applied on appeal intervening

changes in the law under a wide variety of circumstances.

In Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969), after the plaintiff public housing authority had

won an eviction order in state courts, the Department of

Housing and Urban Development altered the procedural

prerequisites to such evictions. This Court held that the

defendant could not bo evicted unless the new procedures

were followed. “The general rule . . . is that an appellate

court must apply the law in effect at the time it renders

its decision.” 393 U.S. at 281. In United States v. Alabama,

362 U.S. 602 (1960), the district court dismissed an action

brought by the United States under the 1957 Civil Rights

Act against the state of Alabama on the ground that the

State could not be sued under that statute. While the case

was pending on appeal Congress passed the 1960 Civil

Rights Act expressly authorizing suits against a state, and

this Court applied the new statute. “Under familiar prin

ciples, the case must be decided on the basis of law now

controlling, and the [new provisions] are applicable to this

litigation.” 362 U.S. at 604. In Ziff r in v. United States,

after a company seeking permission to operate as a con

tract carrier had filed its application with the Interstate

Commerce Commission, the Interstate Commerce Act was

amended to bar such operation by an applicant who was

controlled by a common carrier serving the same territory.

This Court upheld the application of the new law to the

pending request. “A change in the law between a nisi prius

and an appellate decision requires the appellate court to

apply the changed law. A fortiori, a change of law pending

an administrative hearing must be followed in relation to

permission for future acts.” 318 U.S. 73, 78 (1943). See

also Vanderbark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Company, 311 U.S.

53S (1941); Carpenter v. Wabash Railway Co., 309 U.S. 23,

2i (1940), and cases cited; American Steel Foundries v.

Tri-City Cent. Trades Council, 257 U.S. 184, 201 (1921);

Reynolds v. United States, 292 U.S. 443, 449 (1934).

Except where the statute involved expressly purports

to be of exclusively prospective application, see e.g. Gold

stein v. California, 41 U.S.L.W. 4829, 4830 (1973), this

Court has routinely applied new laws to all cases pending

on appeal, without reference to legislative history and

without requiring express statutory language that they be

so applied. When Congress has concluded that greater

justice would be done if a new and different legal principle

were applied to some recurring circumstances, Congress

must be presumed to have intended that that new standard

and the more equitable result entailed be applied to all

cases, including those pending on appeal. Compare John

son v. United States, 163 F.2d 30, 32 (1st Cir. 1908)

(Holmes, J.).

A narrowly drawn exception to this practice has been

sanctioned by this Court where, under the facts of a par

ticular case, application of a new law to a matter arising

before its enactment would work an unfair hardship on one

of the parties. In such a situation this Court has, where

possible, sought to construe the statute to avoid such an

inequitable result. The precise category of cases to which

this exception applies has never been clearly defined. In

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103

(1801), this Court urged such a rule of construction “in

mere private cases between individuals.” 5 U.S. at 106.

In Union Pacific Railroad Co. v. Laramie Stock Yards Co.,

this Court explained the rule applied to statutes which

might interfere with “antecedent rights,” 231 U.S. 190,

199 (1913). Cox v. Hart defined a “retroactive” statute as

one which impaired a vested right or imposed a new obli

gation on a private interest, and indicated that statutes

should not readily be construed as “retroactive” in this

sense. 260 U.S. 427, 433 (1922). In Claridge Apartments

Co. v. Commissioner, 323 11.S. 141 (1944), the Conrt de

liberately construed a new tax law so as not to retroac

tively increase the taxes on “closed transactions.” 323 U.S.

at 164. In Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 149 (1963),

this Court refused to apply new and more strenuous ad

ministrative procedures for obtaining remuneration to a

claimant who had already obtained a “final” and favorable

determination under the old procedures. 376 U.S. at 161.

Most recently, in Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

this Court characterized Greene and its predecessors, more

simply and more cogently, as exceptions “made to prevent

manifest injustice.” 393 U.S. at 282.7

The application of section 718 to the instant case would

work no injustice such as that threatened in Greene. Sec

tion 718 did not alter the defendant school board’s consti

tutional responsibility to provide an education free of the

7 The difference between the rule reaffirmed in Thorpe and the

exception applied in Greene is well illustrated by the facts in those

cases. Both eases involved disputes between a private citizen and

a government, agency. In Thorpe a city public housing authority

had sued to evict the defendant tenant; in Greene a private citizen

who had been discharged when the Department of the Navy re

voked his security clearance brought an action for lost wages.

In both, while the litigation was still pending and before Mr.

Greene bad received reimbursement or Mrs. Thorpe been evicted,

tin' procedures for reimbursement and eviction, respectively, were

changed. However, in Thorpe the application of the new rule

accrued to the benefit of the private citizen, whereas in Greene

this Court refused to apply the change where the beneficiary would

have been the government not the individual litigant. In Greene

the application of the new rule would have interfered with a right

to reimbursement which had been established and became final,

,'S7(i U.S. at 161; in Thorpe the Housing Authority had no com

parable rights to infringe, 303 U.S. at 283. And, while in Thorpe

the tenant had insisted throughout the litigation that she was

entitled to procedural protections guaranteed by the new provision,

in Greene the government had never questioned the procedures

being followed until seven years after the litigation began, those

procedures were altered by administrative regulations. Compare

Citizens lo Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 418-

410 (1071).

r m

b w m % yJ l I S

WuW

b r *wk$

riBflk

M ip

■•if

I l p f c 1

15

stigma of segregation, and plaintiffs do not seek to apply

retrospectively any new standard of conduct first estab

lished in 1972. The school board’s substantive obligations

are those of the Constitution, as announced by this Court;

section 718 only elaborates the remedy available to a pri

vate citizen when local officials have violated the law. As

Senator Cook remarked during the debate on section 718:

The 14th amendment to the Constitution of the

United States was there long before we [Congress]

came to a conclusion that something should be done

in the field of discrimination in the school system of

the United States. We are not talking about some

thing that was born yesterday.8

The school board in the instant case does not claim it would

have acted any differently between 1966 and 1972 had sec

tion 718 been in effect at that time. Under such circum

stances, the application of section 718 to litigation occur

ring before its effective date can hardly be said to be

unfair. The only relevant right which existed prior to the

enactment of section 718 was the right of the instant plain

tiffs to an education in a unitary school system; applica

tion of section 718 to this case serves not to impair that

right but to vindicate it. Plaintiffs’ assertion that they are

entitled to attorneys’ fees is not a new claim suddenly

asserted in the light of section 718; such fees were asked

in the original complaint filed in 1961,3 and have repeatedly

been sought in the proceedings since that time.

That legal fees should be awarded under section 718 for

A v o r k done before its effective date is supported by the

8 117 Cong. Roc. 11528.

3 See 4a .

• .«tU «***■** tr M

.V- •

tPTKS •f} ’ ¥7Kite

M W I T

v • •

ipejfiAf

16

legislative history of the Emergency School Aid Act of

1972.10

Section 718 grew out of a provision contained m a

bill sponsored by Senator Mondale in 1971. The statute

proposed by Senator Mondale would have authorized the

payment of counsel fees out of federal funds specially

set aside for that purpose, $5 million for the first year

and $10 million for the second. That proposal, included

in the committee bill presented to the Senate, expressly

stated that the award would be “for services rendered, ant

costs incurred, after the date of the enactment of this

Act . .”u (Emphasis added) On the floor of the Senate,

Sot:

ot'srrb ist1ZApi't! mi. of «o„,;,oro

t . Tis t x , a r .

sponsored by Senator Cook, section 718 in its present form was

inserted in the bill. 117 Cong. Rec. 11521-11529 ,11724-26. the

House amended the bill passed by the Senate RtrlklI'- e^ ^ thl’̂

after the enacting clause and inserting a new text- which, inter aha

deleted any mention of counsel fees. The provnuon for egal fevs

was restored in conference. Conference Rep. No. 798, 9-uid Cong.,

2nd Scss. (1972). The only debate on the subject of attorneys

fees occurred in the Senate on April 21 and 22, 197 .

11 Section 11(a) of Senator Mondale’s bill, S.683, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess., provided in fu ll:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United States

against a local educational agency a State (or any agency

thereof), or the Department of Health, Education and Me

fare for failure to comply with any provision of this Act

title 1 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act ot

19(15 or discrimination on the basis of raee, color or national

origin in violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

or of the fourteenth article of amendment to the Constitution

of the United States as they pertain to elementary and sec

ondary education, such court shall award, from funds reserved

pursuant to section 3(b)(1)(c), reasonable counsel fee, and

costs not otherwise reimbursed, for services rendered, and

Senator Dominick, with the support of Senator Cook, suc

cessfully amended the bill to delete this proposed section

in its entirety.12 The next day, however, Senator Cook

proposed to substitute new provisions authorizing the

award of such attorneys’ fees against the defendant.13

This new provision deleted the language in Senator Mon

dale’s version which had limited the section to services

rendered after its enactment. This Court should not read

back into section 718 the very limitation regarding appli

cation to services performed prior to enactment which was

deliberately removed from the statute by Congress.

The application of section 718 to cases pending when it

was enacted serves to carry out the purposes of that pro

vision as expressed in the congressional hearings and

debates leading to its enactment. Senator Mondale, who

first urged a statutory authorization of legal fees in these

cases, argued that his proposal and that of Senator Cook

were needed to encourage more private litigation,14 and to

equalize the legal resources available to litigants in such

cases.15 If, however, such fees are oidy awarded for work

done after July 1, 1972, and after the entry of a final order

resulting from and subsequent to those services, substantial

additional funds under this section for the increase of

costs incurred, after the date of enactment of this Act to the

party obtaining such order.

Similarly, the Committee Report states that the federal funds

are available “for services rendered, and costs incurred, after the

date of enactment of the Act.” Sen. Rep. No. 92-61, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess., pp. 55-56 (1971).

12117 Cong. Rec. 11345.

13117 Cong. Rec. 11520-21.

14 114 Cong. Rec. 10760, 10761, 10762-3, 10764, 11339-40, 11343,

11344, 11345.

15 Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the Senate

Labor and Public Welfare Committee, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 99

(1971); 114 Cong. Rec. 10762.

private litigation will not bo available for years.16 It is

hardly likely that Senator Mondale envisioned or desired

such a delay when he called for a statutory right to legal

fees to meet the “urgent need” for vigorous private litiga

tion to resolve the “major crisis in the enforcement of con

stitutional protections affecting civil rights in this land.”17

Senator Cook, the draftsman and sole spokesman for

section 71S as finally enacted, emphasized an additional

reason for his amendment. Senator Cook opposed Senator

Mondale’s proposal on the ground that it failed to require

that the school system which had violated the law pay the

costs incurred in rectifying that violation. He urged:

[W]e can solve the problem by merely inserting the

language that the costs and attorneys’ fees will be

16 The practical realities of school litigation are such that the

goal sought by Senator Mondale will he substantially delayed if

attorneys’ fees are not awarded for services performed prior to the

effective date of the statute. The vast majority of school deseg

regation eases have in the past been, and will continue to he,

brought by a handful of private attorneys supported in many in

stances by national organizations concerned with such litigation.

The costs and salaries of the attorneys must be paid by those

organizations or sacrificed by those attorneys from the moment a

case is begun, but such costs and fees are only available under

section 718 after a final judgment has been entered in the case.

The delay between the commencement of an action and the entry

of any final judgment will often be substantial. In the cases de

cided mb vom. Thompson v. School Board of the City of Newport

News, 472 F.2d 177 (1972), in which the Fourth Circuit refused to

apply section 718 to work done before its effective date, the com

plaints initiating those actions had first been filed in 1961, 1965,

1969 and 1970. Tf section 718 is limited to work done after .Tidy 1,

1972, it will be years before that statute yields sufficient legal fees

to enable private attorneys and their organizational sponsors to

increase the number of school desegregation cases they are finan

cially able to handle. On the other hand, if such fees are made

available now in appropriate pending cases for work done before

July 1, 1972, the resources will be available at once to make pos

sible the increase in such litigation sought by Congress.

17 117 Cong. Rec. 10760, 10762. See also 117 Cong. Rec. 11339,

11342. 11343. 11344.

1.9

charged against the losing litigant. . . . We can even

charge those expenses and make them a debt against

the Title I funds, so that we are penalizing the person

who violates the law; we are penalizing the person

who decides the 14tli amendment is for someone else

and not for him. We are then imposing the cost on

that individual who saw fit to commit an act that the

court concluded was in violation of the, law, or in viola

tion of the proper utilization of Title I funds and

that, as an indirect result thejeof, that person shall

suffer.18

In the debates on his own amendment, Senator Cook re

iterated his desire to place the cost of litigation on the

“guilty party”,19 to assure that a school board violating the

law will “pay for it”,20 and to provide that those who have

disobeyed the constitution “should have to make recom

pense for that mistake.” 21 Senator Cook also referred, as

had Senator Mondale,22 to the inequity of paying with edu

cation funds for the lawyers who unsuccessfully opposed

integration, but not using those funds for attorneys who

achieved an end to segregation.23

18 117 Cong. Rec. 11343 (Emphasis added). See also 117 Cong.

Rec. 11341, 11342.

19117 Cong. Ree. 11725.

20 117 Cong. Rec. 11527.

21 117 Cong. Rec. 11528.

22 Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the Senate

Labor and Public Welfare Committee, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 99

(1971) “Now, most of the money today being spent, publicly

in school desegregation cases is public money which is being spent

for lawyers and legal fees to resist the reach of the 14th amend

ment. So why would it not he fair to set aside a modest, amount to

pay lawyers who are successful in enforcing the Constitution for

legal fees and costs.”

23117 Cong. Rec. 11527, 11528.

20

It is reasonable to assume that Congress contemplated

that the injustices discerned by Senator Cook would be

righted in cases still pending when section 718 became

effective. It cannot plausibly be maintained that Senator

Cook intended that, months or years after the enactment

of section 71S, school boards which had violated the law

would be able to avoid recompensing those who corrected

their mistakes merely because the plaintiffs’ attorneys were

diligent enough to bring that violation to an end prior to

July 1,197 2.24 The statute involved here is not one intended

merely to shape future events by encouraging the initiation

of litigation under the Fourteenth Amendment, compare

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965), but was designed

to effectuate Congress’ judgment that a serious injustice

is worked when, in a case such as this, the offending school

board pays no price for its years of ignoring Brown, while

the private plaintiff must look to himself and the generosity

of his counsel or the public to meet the costs of enforcing

the constitution. Compare Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368

(1964). In deciding who shall ultimately bear the cost of

litigation to end discrimination in the public schools, this

24 Both Senator Mondale and Senator Cook explained that their

goal was to provide the same right to attorneys’ fees in school

discrimination cases as exist for discrimination in housing, 4-

IJ S C 53612(c) in employment, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(A), and pub

lic accommodations, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-e(b). 117 Cong. Rec. 11339

(Remarks of Senator Mondale), 11521 (Remarks of Senator Cook)

See Northcross v. Board of Education of the Memphis City Schools,

41 U.S.L.W. 3635 (1973). In the absence of special circumstances,

a successful plaintiff in a housing, employment or public accom

modations case would be entitled to attorneys’ fees for all the legal

services performed in connection with a case won on April 5, 1. /-

(the day final relief was awarded here) or July 1, 1972 (the day

section 718 became effective). Because the substantive rights and

counsel fee provisions were created by the same statute, sections

2000a-3(b), 2000e-5(k) and 3612(c), 42 U.S.C., apply to all actions

described therein, regardless of when commenced. Congress pre

sumably intended to create a similarly broad right covering all

work done in all school cases.

21

Court should give full effect to the standards and values

established by Congress in section 718 in all cases in which

the question of attorneys’ fees has not been finally resolved

before July 1, 1972.

II.

Attorneys’ Fees 3Iust Be Awarded Because This

Litigation Benefited Olliers.

In the absence of an express statutory requirement of

attorneys’ fees, federal courts in the exercise of their

equitable powers may award such fees where the interests

of justice so require. Their authority to do so derives

from Article I I I26 of the Constitution and, in cases such

as this, section 1983, 42 U.S.C.20 As Justice Frankfurter

noted a generation ago, the power to award such fees “is

part of the original authority of the chancellor to do equity

in a particular situation.” Sprague v. Ticonic National

Bank, 307 U.S. 161, 166 (1939). Federal courts do not

hesitate to exercise this inherent equitable power wherever

“overriding considerations indicate the need for such a

recovery.” Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375,

391-92 (1970).

One well-established case in which such fees are awarded

is where a plaintiff’s successful litigation confers “a sub

stantial benefit on the members of an ascertainable class,”

and where the court’s jurisdiction over the subject matter

of the suit makes possible an award that will operate to

spread the costs proportionately among them. Mills v.

25 “Section 2. Jurisdiction. The judicial power shall extend to all

Cases, in law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws

of the United States, and Treaties made . . .” (Emphasis added.)

26 Section 1983 authorizes “an action at law, suit in equity, or

other proper proceeding for redress.” (Emphasis added.)

22

Electric Auto-Lite, 396 U.S. at 393-94. This rule has its

origins in the “common-fund” cases, which have tradition

ally awarded attorneys’ fees to the successful plaintiff when

his representative action creates or traces a “common-

fund,” the economic benefit of which is shared by all mem

bers of the class. See, e.g. Central Railroad and Banking

Co. v. Pettus, 113 U.S. 116 (1885); Trustees v. Greenough,

105 U.S. 527 (1883). In Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank,

the rationale of these cases was extended to authorize an

award of attorneys’ fees to a successful plaintiff who, al

though suing on her own behalf rather than as a repre

sentative of a class, nevertheless established the right of

others to recover out of specific assets of the same defen

dant through the operation of stare decisis. In reaching

this result, the Court explained that the beneficiaries of

the plaintiff’s litigation could be made to contribute to the

costs of the suit by an order reimbursing the plaintiff out

of the defendant’s assets from which the beneficiaries would

eventually recover. Finally, in Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite

Co., this Court held that the rationale of these cases must

logically extend, not only to litigation that confers a mone

tary benefit on others, but also to litigation “which corrects

or prevents an abuse which would be prejudiced to the

rights and interests” of those others. 396 U.S. at 396.27

Fee-shifting is justified in these cases because “[t]o

allow the others to obtain full benefit from the plaintiff’s

efforts without contributing equally to the litigation ex

penses would be to enrich the others unjustly at the plain

tiff’s expense.” Mills v. Electric Auio-Lite Co., 396 U.S. at

392; see also Fleisclimann Distilling Corp. v. Maier Brew

ing Co., 386 U.S. 714, 719 (1967); Trustees v. Greenough,

105 U.S. 527, 532 (1882). Thus, in Mills this Court ap-

27 Also supporting the award in Mills was the fact that the action

vindicated important statutory policies. 396 U.S. at 396.

23

proved an award of attorneys’ fees to successful share

holder plaintiffs in a suit brought to set aside a corporate

merger accomplished through the use of a misleading proxy

statement in violation of §14(a) of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934, 15 II.S.C. §78(a). In reaching this result,

this Court reasoned that, since the dissemination of mis

leading proxy solicitations jeopardized important interests

of both the corporation and “the stockholders as a group,”

the successful enforcement of the statutory policy neces

sarily “rendered a substantial service to the corporation

and its shareholders.” 396 U.S. at 396. In Ilall v. Cole,

36 L. Ed. 2d 702 (1973), legal fees were approved for a

union member who successfully sued for reinstatement in

his union after he had been expelled for criticizing the

union’s officers. This Court concluded that the plaintiff,

by vindicating his own right, had dispelled the “chill” cast

upon the right of others, and contributed to the preserva

tion of union democracy. 36 L. Ed. 2d at 709. Both Mills

and Hall involved a benefit that was not pecuniary in

nature.28

28 In Mills this Court expressly repudiated any requirement that

the benefit be pecuniary.

The fact that this suit has not yet produced, and may never

produce, a monetary recovery from which the fees could be

paid does not preclude an award based on this rationale. Al

though the earliest cases recognizing a right to reimbursement

involved litigation that had produced or preserved a ‘common

fund’ for the benefit of a group, nothing in these cases indi

cates that the suit must actually bring money into court as a

prerequisite to the court’s power to order reimbursement of

expenses. . . . [A]n increasing number of lower courts have

acknowledged that a corporation may receive a ‘substantial

benefit’ from a derivative suit, regardless of whether the benefit

is pecuniary in nature. . . . [I]t. may be impossible to assign

monetary value to the benefit. Nevertheless . . . petitioners

have rendered a substantial service to the corporation and its

shareholders. 396 IT.S. at 392, 395-396. (Emphasis added.)

Following Mills, legal fees have been awarded in cases involving

such non-pecuniary benefits as guaranteeing free and fair union

24

Sucli legal fees are assessed against the defendant, not

because of any bad faith, but because the costs will thus

be passed onto and borne by the benefiting class. In the

early common-fund cases, the fee was deducted directly

from a sum of money held for distribution to the bene

ficiaries. Trustees v. Greenough, 105 U.S. 527 (18S2). In

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., the beneficiaries of the ac

tion were a corporation and its stockholders; by awarding

attorneys fees against the corporation the Court simul

taneously assessed one of the beneficiaries and assured that

the cost would be borne by the stockholders as owners of

the corporation. 396 U.S. 375, 390. In 1 lull the fees were

paid out of the treasury of the union involved, the con

tents of which were held for use by the union on behalf of

its members, the beneficiaries of the action involved. 36

L. Ed. 2d at 709.

The instant case is clearly governed by Mills and Hall.

Plaintiffs, in dismantling the dual school system within

the city of Richmond benefited many persons other than

themselves.29 This case is a class action on behalf of all

elections, Yablonsld v. United Mine Workers of America, 466 F.2d

424 (D.C. Cir. 1972), cert, denied 41 U.S.L.W. 3624 (1973), dis

crimination in public housing, Hammond v. Housing Authority,

328 F. Supp. 586 (D. Ore. 1971), and inadequate medical facilities

for prisoners. Newman v. State of Alabama, 349 F. Supp. 278

(M.D. Ala. 1972). See also Callahan v. Wallace, 422 F.2d 59

(5th Cir. 1972) ; Jinks v. Mays, 350 F. Supp. 1037 (N.D. Ga.

1972) ; Sincock v. Obara, 320 F. Supp. 1098 (D. Del. 1970). Legal

fees have also been awarded to plaintiffs who simultaneously ef

fectuated public policies and benefited others where the benefits

involved such non-pecuniary matters as legislative reapportionment,

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972) and ending jury

discrimination, Ford v. White (S.D. Miss., Civil Action No.

1230(N), opinion dated August 4, 1972.)

2tl The plaintiffs were able to achieve only such integregation as

was possible within the city itself. A complete dismantling of the

dual system involved would have required merger with the sur

rounding predominantly white counties. See Bradley v. State

Board of Education, No. 72-550 and School Board of the City of

Richmond, Virginia v. State Board of Education, No. 72-549.

fiipipO T

fSfe • .-4' A Wi ̂ t ' * * , >. i, ffE A y. .U •. t1 a , /

—

25

the school children of Virginia and their parents or guard

ians (4a). The harm suffered by black children when

compelled to attend segregated schools is well recognized.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 494 (1954) ;30

Coleman, et ah, Equality of Educational Opportunity

(1966); U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Racial Isolation in

the Public Schools, 106 (1967).31 Nor can the maintenance

of a dual school system be said to have benefited the white

students involved.32 Compare Trafficante v. Metropolitan

Life Insurance Co., 409 U.S. 205 (1972).

30 “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools

has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The im

pact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the

policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as de

noting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of in

feriority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation

with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard]

the educational and mental development of Negro children

and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive

in a racial [ly] integrated school system.”

31 “School personnel in predominantly white schools more often

feel that their students have the potential and the desire for high

attainment. The Equality of Education Opportunity survey found

that white students are more likely to have teachers with high

morale, who want to remain in their present school, and who regard

their students as capable.

“The environment of schools with a substantial majority of Ne

gro students, then, offers serious obstacles to learning. The schools

are stigmatized as inferior in the community. The students often

doubt their own worth, and their teachers frequently corroborate

these doubts. The academic performance of their classmates is

usually characterized by continuing difficulty. The children often

have doubts about their chances of succeeding in a predominantly

white society, and they typically are in school with other students

who have similar doubts. They are in schools which, by virtue both

of their racial and social class composition, are isolated from

models of success in school.”

32 For white children, as for black, a vital part of their educa

tion consists in learning, through contact with their fellows, about

the society in which they live and shaping through such contact

the values which will guide them for years to come. Racial isola

tion cuts off these students from others with widely divergent views

26

Viewed in this context, there can be no doubt that plain

tiffs, to the extent that they succeeded in dismantling the

dual school system in Richmond, rendered a substantial

service to the pul,lie school students of Richmond. Requir

ing reimbursement of plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees out of the

funds33 of the school board “simply shifts the costs of liti

gation ‘to the class that has benefited from them and would

have had to pay them had it brought the suit.’ ” Hall v.

Cole, 36 L. Ed. 2d at 709.

Although such fee shifting is within the inherent author

ity of equity, Congress has the power to circumscribe such

relief. In Fleischmann Distilling Corp. v. Maier Brewing

Co 386 U S 714 (1967), for example, this Court held that

the Lanham Act precluded an award of attorneys’ fees in

a trademark infringement case because the statute “meticu

lously detailed the remedies available” and Congress must

have intended these express remedial provisions “to mark

the boundaries of the power to award monetary relief in

and experiences, and may inculcate fears and prejudices overcome

only with "reat effort later in life. Students who may pursue busi

ness careers in the areas where they were educated will be deprived

of contacts and acquaintances of commercial g p“ $

inconceivable that, among a new generation of Americans tree

racial bigotry, an education in an all white school P ^ l ^ l ^ 11̂

the South, will carry a social stigma inconceivable to earlier gene

tions.

■■ Those funds are held for use on behalf of the public school

students who benefited from this action. Section 22-97(1-) of the

Code of Virginia authorizes the use of such funds: to provide lor

the ta v of teachers and of the clerk of the board, for the cost of

providing schoolhouses and the appurtenances thereto a»4 ttm re-

Lairs thereof for school furniture and appliances, for necessary

textbooks f0; children attending the public free schools whose

parent or guardian is financially unable to furnish them, and for

any other expenses attending the administration ot the public free

school system) so far as the same is under the control or at the

charge of the school officers.”

27

cases arising under the Act,” 386 U.S. at 719, 721.34 Unlike

the Lanham Act, section 1983 contains no specific authoriza

tion of detailed remedies; rather, it broadly authorizes the

courts to grant whatever relief may be appropriate.35 A

defendant is made liable “in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for redress.” Section 1983

recites, not remedies, but the types of proceedings which

may be maintained, and the clear intent of Congress was

not to set any boundary on the type of actions which be

maintained, but to provide on the contrary that any appro

priate proceeding may be commenced. The enactment, some

93 years after section 1983, of Title IV of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act in no way limits the expansive grant of author

ity in section 1983 or circumscribes the inherent equitable

power left unimpaired by that section. Title IV does not

confer upon private parties any new legal remedies, and

expressly provides that nothing therein shall “affect ad

versely the right of any person to sue for or obtain relief

in any court against discrimination in public education.”

42 U.S.C. §2000c-8.36

34 The statute in Flcischmann expressly detailed six specific

remedies, including award of the plaintiff’s damage, the defendant’s

profits, the costs of the action, additional damages up to three

times the amount actually sustained, any amount over and above

the defendant’s profits if that recovery proved inadequate, 15

U.S.C. §1117, as well as injunctive relief. 15 U.S.C. §1116.

35 See Boss v. Goshi, 35 F. Supp. 949, 955 n.15 (D. Hawaii

1972) (“Section 1983, on the other hand, is not a statute provid

ing detailed remedies, and there is no reason to infer any congres

sional intent to limit the otherwise broad equitable powers of this

court.” ) NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703, 709-710, n.9 (M.D.

Ala. 1972); Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691, 695 (M.D. Ala.

1972). See also Lee v. Southern Home Sites, 444 F.2d 143 145

(5th Cir. 1971) (§1982).

36 The decision of the Court of Appeals suggests that Congress

may have intended to revoke this Court’s inherent power to grant

attorney’s fees when, in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, it dealt with

school segregation in Title IV without authorizing legal fees, where

as such fees were provided for in Titles II and VII. Section 2000c-

28

V ) ^

h i .

Plain lifts Are E nlilled to Attorneys’ Fees Because

They Maintained This Action as Private Attorneys

General.

A substantial number of lower courts have concluded

that successful plaintiffs should be awarded attorneys’ fees

where they sue, not merely on their own behalf, but to

enforce important constitutional or statutory policies.3

Replying on both the reasoning and standard set in this

Court’s opinion in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 400 (1968), these decisions have concluded that

legal fees should be awarded to such private attorneys

general unless there are special circumstances which would

render an award unjust. The District Couit m the instant

case relied on this ground as an alternative basis for its

award of fees (135a-141a). This Court, however, has not

indicated whether plaintiffs can recover fees as private

attorneys general in the absence of an express authoriza

tion such as that present in Newman?* Plaintiffs maintain

8 forbids any such conclusion however. If the existence of any

part of Title IV is not. to adversely affect the right to counsel fees,

ipso facto the existence of Title IV itself cannot do so.

37 Lee v Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir.

1971) ; Cooper v. Allen, 467 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1972) ; Knight v.

Aucirllo, 453 F.2d 852 (1st Cir. 1972) ; Ross v. Goshi, 351 F.Supp.

949 (D. Hawaii 1972) ; La Raza TJnida v. Volpe, 57 F.R.D. 94

(N.D. Cal. 1972); Ford v. White (S.D. Miss., Civil Action No.

1230(N), opinion dated August 4, 1972); Jinks v. Mays, 350

F.Supp. 1037 (N.D. Ga. 1972); Wyatt v. Stickncy, 344 F.Supp.

387 (M.D. Ala. 1972) ; NAACP v. Aliev, 340 F.Supp. 703 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) ; Sims v. Amos, 340 F.Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1971).

38 This Court expressly declined to reach that question in Hall

v. Cole, 36 G. Ed. 2d 702, 708 n.7 (1973), and Northcross V.

Board, of Education of the Memphis City Schools, 41 U.S.L.W.

3635 n.2 (1973).

that such awards are proper, and would urge this Court to

resolve this question of growing importance for the guid

ance of the lower courts.

The well established common benefit cases, discussed

supra, sanction the award of attorneys’ fees where a plain

tiff’s action confers a substantial benefit on the members

of an ascertainable class, such as the members of a union

or the shareholders of a corporation. 11 all v. Cole, 36

L. Ed. 2d 702, 709 (1973) ; Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co.,

396 U.S. 375, 393-394 (1970). The rationale of those cases

is equally applicable where, as here, the plaintiffs’ action

enforces important constitutional and statutory policies

and thus benefits the public at large. Compare Mills v.

Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. at 396.39 As this Court

indicated in Newman, any action which vindicates such

policies serves, ipso facto, to “advance the public interest.”

390 U.S. 400, 402.

The plaintiffs in this action sued to vindicate the right

of all students to attend not black schools or white schools,

but just schools, a national policy of the highest impor

tance. Compare, Broum v. Board of Education, 397 U.S.

483, 493 (1954). This national policy has been embraced

and advanced in major legislation. Northcross v. Board of

Education of the Memphis City Schools, 41 U.S.L.W. 3635

(1973).40 The achievement of this goal of integration of

39“ [I]n vindicating the statutory policy, petitioners have ren

dered a substantial service to the corporation and its shareholders.”

40 Congress lias expressly authorized the Attorney General to

institute civil actions under appropriate circumstances to “further

orderly achievement of desegregation in public education.” 42

U.S.C. § 2000c-(i. The use of force or threats of force to prevent

any person from enrolling in or attending any public school be

cause of his race has been made a federal crime. 18 U.S.C. §245

(b)(2)(A ). All federal agencies providing financial assistance to

state schools have been directed by Congress to insure, by termina

tion of funding or otherwise, that no person is excluded from

30

tho public schools is vital to the public interest. It develops

for the benefit of all the creative talents of students who

might otherwise be relegated to an inferior education, it

contributes to the skills, motivation and earning power of

young men and women who might otherwise be destined

for the burgeoning ghettos that blight our major cities,

and it inculcates in students, teachers, parents and others

in the community racial attitudes essential to the creation

of a society in which blacks and whites work and live

together in peace.

The plaintiffs who bring litigation of such national im

port should not be required to bear alone tho cost of the

ensuing public benefit. This Court has abandoned any

suggestion that a private party lacks standing to sue where

his interest is essentially the same as all his fellow citizens,

Flast v. Colien, 392 U.S. 83 (1968); a plaintiff should not

be denied reimbursement for benefits conferred on others

merely because the beneficiary is not a small and distinct-

group, but the public at large. In the instant case the funds

of the defendant school board derive from taxes paid by

residents of the area most immediately affected by this

action.41 Assessing the cost of this action against such

public revenues serves to pass on that cost to those who

profited from it. Hall v. Cole, 36 L. Ed. 2d 702, 709 (1973).

participation in any such program on account of race. 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d-l. On repeated occasions Congress has authorized grants

and technical assistance to assist school boards in ending segrega

tion. 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c-2 ct ftr.q; Elementary and Secondary Edu

cation Act of 1906, P.E. 89-750, §181; Emergency School Aid Act

of 1972, P.E. 92-318, Title VII.

41 A somewhat different situation would be presented where the

defendant was a private person or organization, hence a benefici

ary of the action but not necessarily able to pass on the cost of

legal fees to all the oilier beneficiaries. This would be a circum

stance relevant to, though not by itself controlling, the district

court s decision as to whether special circumstances were present

which rendered an award of counsel fees unjust. See p. 34, infra.

31

The award of legal fees was appropriate in Mills and

Hall, not only because the litigation benefited the stock

holders and union members involved, but because it bene

fited the corporation and union as well. See 396 U.S. 375,

396. That is not to say that the officials of the union or

corporation supported the litigation or welcomed its re

sults; the contrary was of course the case. Rather, Con

gress had defined the interests of corporations and unions

by law in the Securities Exchange Act and the Labor-

Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, respectively.

In the instant case the school board is entirely a creature

of the law; its only interest is in achieving the goals set

by law in the manner also fixed by law. The particular de

sires of those who may sit on the board at any point in

time, to the extent they are inconsistent with these goals

and purposes, do not correspond to the legally cognizable

interests of the board. Under the Constitution, the estab

lishment of a unitary school system is as vital to the inter

ests of the board as hiring instructors, teaching arithmetic,

or providing students with books. An individual plaintiff

who helps achieve any of these public goals through litiga

tion is entitled to have his attorneys’ fees paid by the

defendant school board.

The power of the courts to award legal fees to a private

attorney general conferring such a benefit on the public

or the government derives, as in all common benefit cases,

from the inherent equity power of the courts. See p. 21,

supra. In the instant case the existence of that power is

amply confirmed by the statutes under which this action is

brought. The remedy authorized, 42 U.S.C. §1983; 28 TJ.S.C.

§1343(3), is not simply damages or an injunction, but “re

dress” of deprivations of basic rights. This language con

stitutes the broadest possible authorization to the courts

to fashion a just and effective remedy. It was to provide

just such broad relief, in the face of inadequate state reme-

32

dies, that section 1983 was first enacted. Monroe v. Pape,

3G5 U.S. 167, 178 (1961). The term “redress” contemplates

that the aggrieved plaintiff will he restored to the situation