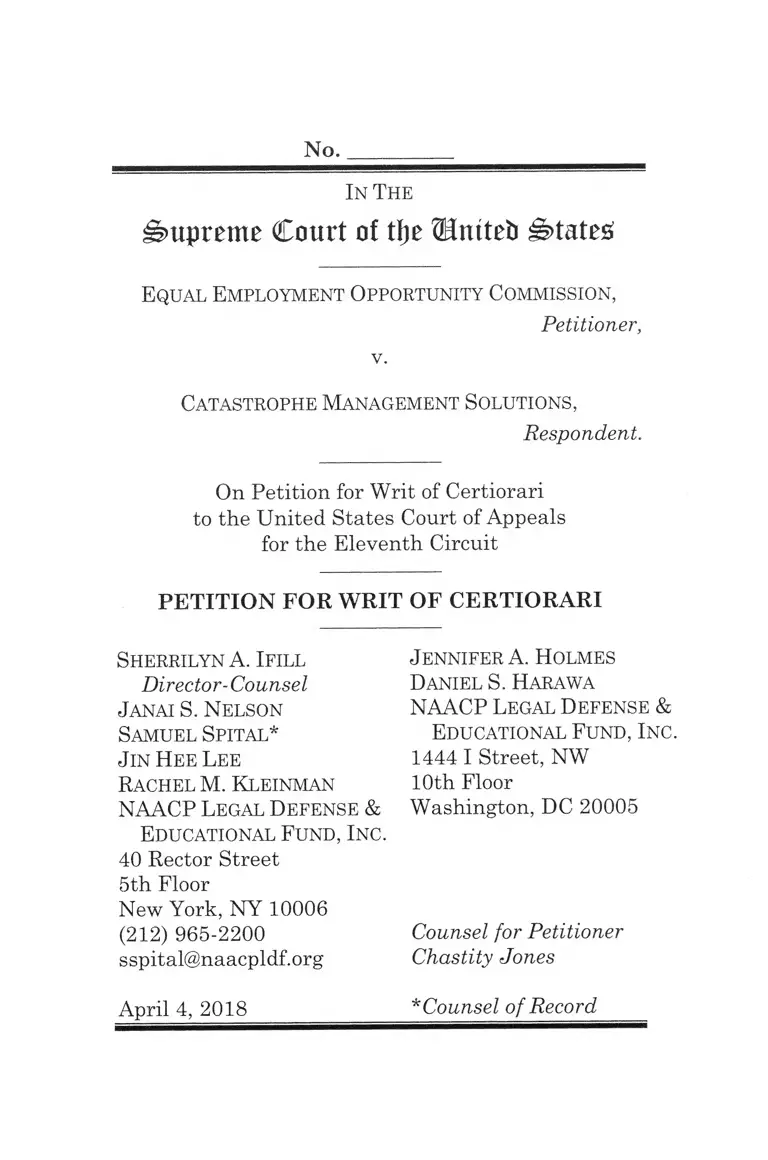

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Catastrophe Management Solutions Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 4, 2018

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Catastrophe Management Solutions Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 2018. cc1f63ed-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2eda605c-d2ca-4a6c-9337-209f0af44bd2/equal-employment-opportunity-commission-v-catastrophe-management-solutions-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In The

No.

Supreme Court of tlje ®mteti H>tate£

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Petitioner,

v.

Catastrophe Management Solutions,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital*

Jin Hee Lee

Rachel M. Kleinman

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street

5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

sspital@naacpldf.org

April 4, 2018 ____________

Jennifer A. Holmes

Daniel S. Harawa

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc

1444 I Street, NW

10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

Counsel for Petitioner

Chastity Jones

* Counsel of Record

mailto:sspital@naacpldf.org

QUESTION PRESENTED

Chastity Jones, an African-American woman, was

hired for a position at a call center by Catastrophe

Management Solutions, Inc. (“CMS”). CMS then

rescinded her job offer solely because Ms. Jones’s hair

was in natural Iocs (or “dreadlocks”), which CMS’s

Human Resources Manager contended “tend to get

messy” and therefore violated CMS’s grooming policy.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit upheld the dismissal of the Complaint, on the

ground that Title VII does not prohibit discrimination

based on “mutable” characteristics. This decision

contravenes controlling precedent in Price

Waterhouse u. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), where

this Court ruled that Title VII prohibits

discrimination on the basis of stereotypes—in that

case, concerning the “mutable” traits of a female

employee’s demeanor, dress, and hairstyle.

The question presented is:

Whether an employer’s reliance on a false racial

stereotype to deny a job to an African-American

woman is exempt from Title VII’s prohibition on

racial discrimination in employment solely because

the racial stereotype concerns a characteristic that is

not immutable.

(i)

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

Petitioner Chastity Jones is an individual and

citizen of Alabama who was the real party in interest

in the proceedings below. The Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) was the plaintiff

and appellant in the proceedings below and brought

this action based on its investigation of Ms. Jones’s

charge of discrimination. Respondent Catastrophe

Management Solutions, Inc. was the defendant and

appellee in the proceedings below.

(ii)

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Counsel for Ms. Jones, the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

organization that has not issued shares of stock or

debt securities to the public and has no parent

corporation, subsidiaries, or affiliates that have

issued shares of stock or debt securities to the public.

(iii)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED ........................... i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING...................... ii

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT..........iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES....................................... vii

OPINIONS BELOW........................................................1

JURISDICTION.............................................................. 1

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED..................2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE...................................... 3

I. CMS Rescinds Ms. Jones’s Job Offer

Because of Her Locs .............................................. 4

II. Proceedings in the District C ourt....................... 8

III. Proceedings in the Eleventh Circuit Court of

Appeals......................................................... 10

(iv)

PAGE(S)

(v)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT................ 13

I. The Decision Below Contradicts this Court’s

Title VII Precedent Forbidding Stereotype-

Based Discrimination .............. ......................... 15

II. The Decision Below Conflicts with Decisions of

Other Federal Circuits Concerning Title VII’s

Prohibition on Stereotype-Based

Discrimination ....................................................27

A. The Majority of Circuits Follow Price

Waterhouse Without Applying an

Immutability T est.................................... 28

B. Other Circuits Have Specifically Held that

Title VII Prohibits Adverse Employment

Actions Based on Racial Stereotypes .... 30

CONCLUSION 33

(vi)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

APPENDIX

Opinion and Judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit.......................................................... App. la

Opinion and Order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District

of Alabama................................................App. 34a

Order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama.... App. 46a

Rehearing Order of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit....................................................... App. 48a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Ash v. Tyson Foods, Inc.,

546 U.S. 454 (2006).................................................26

Ashcroft v. Iqbal,

556 U.S. 662 (2009)................................................ 25

Back v. Hastings On Hudson Union Free

Sch. Dist., 365 F.3d 107 (2d Cir. 2004)...........28, 29

Bibby v. Phila. Coca Cola Bottling Co.,

260 F.3d 257 (3d Cir. 2001).............................. 29, 30

Chadwick v. WellPoint, Inc.,

561 F.3d 38 (1st Cir. 2009)............................... 28, 29

Doe v. City of Belleville,

119 F.3d 563, 580 (7th Cir. 1997),.........................30

EEOC v. Boh Bros. Const. Co.,

731 F.3d 444 (5th Cir. 2013).................................. 29

EEOC v. Catastrophe Mgmt. Sols.,

11 F. Supp. 3d 1139 (S.D. Ala. 2014)............passim

EEOC v. Catastrophe Mgmt. Sols.,

837 F.3d 1156 (11th Cir. 2016)............................. 10

(vii)

PAGE(S)

(viii)

EEOC v. Catastrophe Mgmt. Sols.,

852 F.3d 1018 (11th Cir. 2016)

reh’g denied, 876 F.3d 1273 (11th Cir. 2017)

............................................................................. passim

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976)..................................................15

Garcia v. Gloor,

618 F. 2d 264 (5th Cir. 1980)................................. 11

Glenn u. Brumby,

663 F.3d 1312 (11th Cir. 2011).............................. 29

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971)............................................. 3, 16

Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mut. Hosp. Ins.,

538 F. 2d 164 (7th Cir. 1976).................................12, 31

Lewis v. Heartland Inns of Am., LLC,

591 F.3d 1033 (8th Cir. 2010)................................ 29

L.A. Dep’t of Water & Power v. Manhart,

435 U.S. 702 (1978)................................................. 16, 17

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

15

Nichols v. Azteca Rest. Enters.,

256 F.3d 864 (9th Cir. 2001)............................ 29-30

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

490 U.S. 228 (1989)............................ ............ passim

St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks,

509 U.S. 502 (1993)........................................... 25-26

Satz u. ITT Fin. Corp.,

619 F,2d 738 (8th Cir. 1980).................................. 32

Smith v. City of Salem,

378 F.3d 566 (6th Cir. 2004).................................. 29

Smith v. Wilson,

705 F.3d 674 (7th Cir. 2013).................................. 32

Thomas v. Eastman Kodak Co.,

183 F.3d 38 (1st Cir. 1999)............................... 30, 31

U.S. Postal Serv. Bd. of Governors v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711 (1983)............................... ..................26

Washington County v. Gunther,

452 U.S. 161 (1981)................................ .......... 15, 16

Willingham v. Macon Tel. Publ’g Co.,

507 F.2d 1084 (5th Cir. 1975).................................. 9

(ix)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

Zarcla v. Altitude Express, Inc:.,

883 F.3d 100 (2d Cir. 2018).............................. 28-29

STATUTES & RULES:

28 U.S.C.

§ 1331............................................................................ 9

§ 1337............................................................ 9

§ 1343............................................................................ 9

§ 1345............................................................................ 9

42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(a)...................................................................2

§ 2000e-2(e).................................................................17

§ 2000e-2(m).............................. .......................... 2, 20

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166,

§ 107(a), 105 Stat. 1071, 1075 (1991)

(codified as amended at

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(m))........................... ................20

Sup. Ct. R. 10(a).......................... ........... ...............15, 27

Sup. Ct. R. 10(c).................................................... 15, 25

(x)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

(xi)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PAGE(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

110 Cong. Rec. 7247........................................... ......... 16

Nikki Brown, Why the #ProfessionalLocs Hashtag

Still Matters, ESSENCE (Oct. 25, 2016)................... 6

Paulette M. Caldwell, A Hair Piece: Perspectives

on the Intersection of Race and Gender,

1991 Duke L.J. 365 (Apr. 1991).............. ............ 7, 8

Funmi Fetto, How to Guide: Tips for Caring

for Afro Hair, GLAMOUR (June 15, 2016)................ 24

David S. Joachim, Military to Ease Hairstyle Rules

After Outcry from Black Recruits, N.Y. TIMES

(Aug. 14, 2014)............................................... 6

Alexis M. Johnson, et al ., The “Good Hair” Study:

Explicit and Implicit Attitudes Toward Black

Women’s Hair 6, Perception Institute (Feb.

2017).............................................................................. 7

Kayla Lattimore, When Black Hair Violates the

Dress Code, NPR (July 17, 2017)............................. 6

David Moye, Mom Accuses Principal of Cutting Her

Son’s Hair Without Permission, HUFF. POST

(Mar. 28, 2018) 6

(xii)

PAGE(S)

Tania Padgett, Ethnic Hairstyles Can Cause

Uneasiness in the Workplace, CHICAGO TRIBUNE

(Dec. 12, 2007)............................................................. 7

Carla D. Pratt, Sisters in Law: Black Women

Lawyers’ Struggle for Advancement,

2012 Mich. St. L. Rev. 1777 (2012)..........................7

Crystal Tate, 16-Year-Old Black Student with

Natural Hair Asked by School to “Get Her Hair

Done, ” E sse n c e (May 16, 2017)................................ 7

Brown White, Releasing the Pursuit of Bouncin’ and

Behavin’ Hair: Natural Hair as an Afrocentric

Feminist Aesthetic for Beauty, 1 Int’l J. Media &

Cultural Pol. 295 (2005).............................................4

John-John Williams IV, Afros, Dreads, Natural

Styles More Popular, Still Controversial, Ba l t .

SUN (Mar. 4, 2015).................................................... 24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(CONTINUED)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

OPINIONS BELOW

The panel opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, affirming the

judgment of the district court, is reported at 852 F.3d

1018 (11th Cir. 2016), and is reproduced at App. la-

33a. The opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, denying a petition

for rehearing en banc, with accompanying concurring

and dissenting opinions, is reported at 876 F.3d 1273

(11th Cir. 2017), and is reproduced at App. 48a-86a.

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama, dismissing the EEOC’s

Title VII claim, is reported at 11 F. Supp. 3d 1139

(S.D. Ala. 2014), and is reproduced at App. 34a-45a.

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama, denying leave to file

the Amended Complaint, is unreported and is

reproduced at App. 46a-47a.

JURISDICTION

The court of appeals entered its judgment on

December 13, 2016. The EEOC filed a timely petition

for rehearing en banc on December 23, 2016, which

the court of appeals denied on December 5, 2017. On

February 28, 2018, this Court extended the time for

Ms. Jones to file a petition for writ of certiorari by 30

days. Order on Application No. 17A902. With this

petition, Petitioner also files a motion for leave to

intervene in this case. This Court has jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

2

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 703(a) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 provides:

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer -

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge

any individual . . . because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his

employees or applicants for employment

in any way which would deprive or tend

to deprive any individual of employment

opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee, because

of such individual’s race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin.

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a).

Section 703(m) of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 provides:

(m) Except as otherwise provided in this

subchapter, an unlawful employment

practice is established when the

complaining party demonstrates that

race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin was a motivating factor for any

employment practice, even though other

factors also motivated the practice.

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(m).

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In enacting Title VII, Congress intended “the

removal of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment when the barriers operate

invidiously to discriminate on the basis of racial or

other impermissible classification.” Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431 (1971). In an age where

employment discrimination rarely presents itself in

policies that explicitly exclude employees based on

skin color, the vitality of Title VII depends on its

ability to root out more subtle practices—facially

neutral policies, racial proxies, stereotyped

thinking—that still operate to disfavor applicants

based on their race. The economic security and

dignity of working people depend on the application of

Title VII to remove discriminatory obstacles from the

path of equal employment opportunity.

The decision below diverges from this Court’s

precedents by categorically insulating a form of

discrimination from Title VII’s reach: employment

decisions motivated by racial stereotypes but

expressed as restrictions on “mutable”

characteristics. This Court should grant certiorari

because reading an immutability requirement into

Title VII is inconsistent with this Court’s decisions

and an outlier position among the courts of appeal.

Policies unrelated to merit or job function but based

on racial stereotypes have no place in a fair and equal

workplace.

4

I. CMS Rescinds Ms. Jones’s Job Offer

Because of Her Locs.

Chastity Jones, an African-American woman,

applied online for a position as a Customer Service

Representative with Catastrophe Management

Solutions, Inc. that entailed handling claims

processing at a call center. Am. Compl. f 10, ECF No.

21-1. The position did not require in-person contact

with customers or the public. Id. CMS invited Ms.

Jones to an in-person interview, to which she wore a

blue business suit with dark pumps. Id. f 12. At the

time, Ms. Jones had short, well-kept locs (or

“dreadlocks”).1 Shortly after the interview, CMS’s

Human Resource Manager, Jeannie Wilson, informed

Ms. Jones and other selected applicants that they

were hired. Id. ]f 14.

After telling Ms. Jones that she was hired, Ms.

Wilson and Ms. Jones had a private meeting about

scheduling. Id. ̂ 15. In that meeting, Ms. Wilson

asked Ms. Jones whether her hair was in

“dreadlocks.” Id. f 16. When Ms. Jones answered

affirmatively, Ms. Wilson informed her that CMS

could not hire her with her locs. Id. Ms. Jones asked

why her hair was a problem, and Ms. Wilson stated 1

1 Except where quoting the record below, this petition uses the

term “locs” to describe Ms. Jones’s hair and similar styles worn

by innumerable Black persons across professions. Some prefer

the term “locs” or “locks,” as the term “dreadlocks” originated

from the historical disparagement of Black slaves. See Am.

Compl. f 20; Brown White, Releasing the Pursuit of Bouncin’ and

Behavin’ Hair: Natural Hair as an Afrocentric Feminist Aesthetic

for Beauty, 1 Int’l J. Media & Cultural Pol. 295, 296 n.3 (2005)

(“[T]he term dreadful was used by English slave traders to refer

to Africans’ hair, which had probably loc’d naturally on its own

during the Middle Passage.”) (emphasis added).

5

that Iocs “tend to get messy, although I’m not saying

yours are, but you know what I’m talking about.” Id.

Ms. Jones refused to cut off her hair, and Ms. Wilson

told her that CMS would not hire her and asked her

to return the paperwork for new hires.

At the time, CMS had a written grooming policy,

which stated: “All personnel are expected to be

dressed and groomed in a manner that projects a

professional and businesslike image while adhering

to company and industry standards and/or guidelines

. . . hairstyle [s] should reflect a business/professional

image. No excessive hairstyles or unusual colors are

acceptable . . . . ” Id. U 17. The policy did not expressly

refer to Iocs or dreadlocks. Id. ̂ 18. Ms. Jones had

short Iocs, and CMS did not suggest her hairstyle was

“excessive.” Instead, CMS interpreted its policy to

prohibit Iocs based on the stereotype that they tend to

“get messy” and withdrew Ms. Jones’s offer of

employment on that basis, despite assuring her that

her own hair did not fit that description. Id. *|j 16.

Locs are a style commonly worn by people of

African descent, in which natural Black hair forms

into larger coils. Id. 8, 19. In our society, locs are

generally associated with Black people. Id. f 26. The

texture of Black hair makes it conducive to the

development of locs, which can be formed with

manipulation (“cultivated locs”) or without (“freeform

locs”). See id. f 19. Numerous prominent Black

Americans—especially in the arts and the academy—

wear locs, including Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Ava

DuVernay (film director), Heather Williams (former

Assistant Attorney General for the State of New

York), Angela Smith Jones (Deputy Mayor of

Indianapolis and a former leader of the Indianapolis

6

Chamber of Commerce), Vincent Brown (Harvard

professor), and many less well-known individuals.2

Yet, Iocs are often the target of scorn and derision

based on long-held stereotypes that natural Black

hair is dirty, unprofessional, or unkempt. Am. Compl.

U1f 27, 30. Indeed, the term “dreadlocks” originated

from slave traders’ descriptions of Africans’ hair that

had naturally formed into Iocs during the Middle

Passage as “dreadful.” Id. ]j 20.

The stereotype that Black natural hairstyles are

dirty or unkempt and therefore not appropriate for

more formal settings remains unfortunately

widespread. For example, until 2014, the U.S.

military banned a number of common Black

hairstyles, including cornrows and braids.3 School

administrators and dress codes also often restrict

Black natural hairstyles, and in one dramatic recent

episode, a school principal reportedly took scissors to

a Black student’s Iocs.4

2 Nikki Brown, Why the #ProfessionalLocs Hashtag Still Matters,

Essence (Oct. 25, 2016),

https://www.essence.com/beauty/professionallocs-hashtag

(compiling photos and statements of Black professionals with

Iocs).

3 David S. Joachim, Military to Ease Hairstyle Rules After Outcry

from- Black Recruits, N.Y. TIMES (Aug. 14, 2014),

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/us/military-hairstyle-

rules-dreadlocks-cornrows.html.

4 David Moye, Mom Accuses Principal of Cutting Her Son’s Hair

Without Permission, HUFF. POST (Mar. 28, 2018),

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/mississippi-boy-hair-locs-

cut-principal_us_5abbfa33e4b03e2a5c78e34d; see also Kayla

Lattimore, When Black Hair Violates the Dress Code, NPR

(July 17, 2017),

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/07/17/534448313/when-

black-hair-violates-the-dress-code (describing two Black

https://www.essence.com/beauty/professionallocs-hashtag

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/us/military-hairstyle-rules-dreadlocks-cornrows.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/us/military-hairstyle-rules-dreadlocks-cornrows.html

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/mississippi-boy-hair-locs-cut-principal_us_5abbfa33e4b03e2a5c78e34d

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/mississippi-boy-hair-locs-cut-principal_us_5abbfa33e4b03e2a5c78e34d

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/07/17/534448313/when-black-hair-violates-the-dress-code

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/07/17/534448313/when-black-hair-violates-the-dress-code

7

The belief that natural hairstyles for Black

women are inappropriate in the workplace has

particular and longstanding currency. A recent study

found that White women, on average, show explicit

bias against “black women’s textured hair,” rating it

“less professional than smooth hair.”5 And that

stereotype is communicated to Black women in a

variety of ways. For example, at a 2007 event hosted

by a prominent law firm, a Glamour editor told a

roomful of female attorneys that “afro-styled hairdos

and dreadlocks are Glamour don’t’s.”6

Given these attitudes about their hair, it is no

surprise that a recent study found many Black women

feel pressure to straighten their hair for work.7 In

students punished for wearing braids); Crystal Tate, 16-Year-

Old Black Student with Natural Hair Asked by School to “Get

Her Hair Done,” ESSENCE (May 16, 2017),

https://www.essence.com/hair/natural/black-student-natural-

hair-asked-to-get-hair-done.

5 See Alexis M. Johnson, et al., The “Good Hair” Study:

Explicit and Implicit Attitudes Toward Black Women’s

Hair 6, Perception Institute (Feb. 2017),

https://perception.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/TheGood-

HairStudyFindingsReport.pdf.

6 Tania Padgett, Ethnic Hairstyles Can Cause Uneasiness in the

Workplace, CHICAGO TRIBUNE (Dec. 12, 2007),

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-12-

12/features/0712100189_l_hair-glamour-dreadlocks; see also

Paulette M. Caldwell, A Hair Piece: Perspectives on the

Intersection of Race and Gender, 1991 DUKE L.J. 365, 367, 368

n.7 (Apr. 1991) (describing Hyatt’s firing of an African-American

woman for wearing her hair in braids; in justifying the firing,

Hyatt’s personnel manager stated: “What would our guests

think if we allowed you to wear your hair like that?”).

7 See JOHNSON, “Good Hair” Study, supra note 5 at 12; Carla D.

Pratt, Sisters in Law: Black Women Lawyers’ Struggle for

Advancement, 2012 Mich. St. L. Rev. 1777, 1784 (2012).

https://www.essence.com/hair/natural/black-student-natural-hair-asked-to-get-hair-done

https://www.essence.com/hair/natural/black-student-natural-hair-asked-to-get-hair-done

https://perception.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/TheGood-

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-12-

8

other words, many Black women who wish to succeed

in the workplace feel compelled to undertake costly,

time-consuming, and harsh measures to conform

their natural hair to a stereotyped look of

professionalism that mimics the appearance of White

women’s hair. Professor Paulette Caldwell described

this fraught choice:

For blacks, and particularly for black

women, [hairstyle] choices . . . reflect the

search for a survival mechanism in a

culture where [their] social, political,

and economic choices . . . are conditioned

by the extent to which their physical

characteristics, both mutable and

immutable, approximate those of the

dominant racial group.8

In this case, there was nothing subtle or indirect

about the pressure on Ms. Jones to change her natural

hairstyle if she wanted to succeed at work. Based on

stereotyped assumptions about Ms. Jones’s natural

hair, CMS’s human resources manager told Ms. Jones

she would have to either cut off her Iocs or lose her

offer of employment.

II. Proceedings in the District Court

After CMS rescinded its job offer, Ms. Jones

timely filed a charge of discrimination with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”).

Am. Compl. [̂ 6. In September 2013, the EEOC filed

this action against CMS on Ms. Jones’s behalf,

alleging that CMS engaged in intentional race-based

discrimination in violation of Title VII, seeking

monetary relief for Ms. Jones and an injunction. App.

8 Caldwell, A Hair Piece, supra note 6 at 383.

9

2a. The Complaint alleged that CMS discriminated

against Ms. Jones based on her race by interpreting

its grooming policy to require her to cut off her Iocs as

a condition of her employment. Compl. *[[f 9-13, ECF

No. 1. Jurisdiction was proper under 28 U.S.C.

§§ 1331, 1337, 1343, and 1345. Id. f 1.

CMS moved to dismiss the Complaint. Asserting

that employees “can control their dress, makeup, and

hair styling,” CMS contended its policy against Iocs

was outside the scope of Title VII because it did not

apply to immutable characteristics. Def.’s Mot. to

Dismiss 2, ECF No. 7.

In January 2015, the district court granted CMS’s

motion, relying on Willingham v. Macon Tel. Publ’g

Co., 507 F.2d 1084 (5th Cir. 1975) (en banc), which

predates this Court’s decision in Price Waterhouse.

App. 39a-41a, 44a. The district court concluded that

Title VU’s protections are limited to discrimination on

the basis of immutable characteristics, which

excludes “a hairstyle, even one more closely

associated with a particular ethnic group.” App. 42a.

In rejecting arguments that Iocs are a racial identifier

and that CMS’s decision not to hire Ms. Jones was

based on a racial stereotype, the district court

reasoned that Iocs are not “exclusively]” worn by

Blacks and are “not inevitable and immutable”

despite being “a reasonable result of [Black] hair

texture, which is an immutable characteristic.” App.

44a. The district court also denied the EEOC’s motion

for leave to amend, finding that the Amended

Complaint “offers nothing new” and would be futile in

light of the court’s interpretation of Title VII. App.

46a-47a. The EEOC timely filed an appeal. App. 7a.

10

III. Proceedings in the Eleventh Circuit

Court of Appeals

In its appeal, the EEOC argued that the district

court erred in holding that the EEOC had not pleaded

a prima facie case of disparate treatment. The EEOC

contended that the district court wrongly

characterized its claim as merely concerning a

grooming requirement divorced from its racial

context. Appellant’s Br. at 18. The EEOC pointed out

that its Amended Complaint contained detailed

allegations about the nexus between Iocs and race,

which supported a claim that the adverse

employment action against Ms. Jones was intentional

race-based discrimination. Id. Among other

allegations, the Amended Complaint pleaded that

CMS’s stated reason for prohibiting Iocs (they “tend to

get messy”) was based on stereotypes about Black

natural hair and a preference for White hair

conventions. Id. at 12, 31-32. The EEOC argued that

in light of these allegations, the district court erred in

dismissing the Complaint and denying leave to

amend. Id. at 13.

In December 2016, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed

the district court’s decision.9 The court held that the

EEOC’s Amended Complaint10 did not state a claim of

9 The Eleventh Circuit issued a prior opinion in September 2016,

but subsequently withdrew and replaced that opinion in

December. 837 F.3d 1156 (11th Cir. 2016), withdrawn and

superseded, 852 F.3d 1018 (11th Cir. 2016). This petition

discusses only the latter opinion.

10 As the Eleventh Circuit recognized, the operative allegations

here are those in the Amended Complaint. App. 6a. (“Like the

district court, we accept as true the well-pleaded factual

allegations in the proposed amended complaint.”). Unless

11

intentional discrimination because Title VII prohibits

discrimination on the basis of “immutable

characteristics,” and the EEOC did not allege that

Iocs are an immutable trait of Black persons. App. 2a.

Noting that Title VII did not define the word “race,”

the panel surveyed dictionaries contemporaneous

with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

concluding that “‘race’ as a matter of language and

usage, referred to common physical characteristics

shared by a group of people and transmitted by their

ancestors over time.” App. 14a-17a. The panel

determined that “immutable” was an apt term to

describe such characteristics, while conceding that

the word did not appear in any of the definitions of

“race” in the dictionaries it consulted. Id.

Viewing itself bound by Willingham (holding

employer’s policy about hair length for male

employees was not sex discrimination), and Garcia v.

Gloor, 618 F. 2d 264 (5th Cir. 1980) (holding

employer’s English-only rule was not discrimination

on the basis of national origin), the panel further

concluded that circuit precedent dictated that Title

VII applies to protected classes “with respect to their

immutable characteristics, but not their cultural

practices.” App. 22a. The panel did not cite Price

Waterhouse or discuss its effect on Willingham or

Garcia. The panel recognized that one of the EEOC’s

arguments for reversal was that CMS’s application of

its grooming policy to deny Ms. Jones’s employment

constituted racial stereotyping in violation of Title

VII, App. 9a, but it did not address that argument.

otherwise noted, the Petition therefore refers to the “Amended

Complaint” as the “Complaint.”

12

While acknowledging the difficulty in

administering an immutable/mutable distinction, the

panel nevertheless concluded that it was required by

Title VII. App. 22a-23a. In the panel’s view, that

distinction allowed it to reconcile its decision in this

case with Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mut. Hosp. Ins., 538

F. 2d 164 (7th Cir. 1976) (en banc), cert, denied, 429

U.S. 986 (1976), which recognized that discrimination

against a Black employee for wearing her hair in an

afro violated Title VII. Id. The panel did not,

however, explain why afros should be considered

immutable but Iocs mutable: both are natural Black

hairstyles but neither is unchangeable.

The EEOC petitioned the Eleventh Circuit to

rehear the case en banc. The EEOC maintained that

it had stated a plausible claim of race discrimination,

specifically, that CMS’s ‘ interpretation of] its

appearance policy to impose a per se ban on

dreadlocks” evinced a preference for “Caucasian hair

and style standards” and placed on Black applicants

the burden of meeting those conventions. Appellant’s

Pet. for Reh’g at 6-7. The EEOC criticized the panel’s

immutability standard as inconsistent with Price

Waterhouse and leading to absurd distinctions

between afros and Iocs. Id. at 10-12.

The Eleventh Circuit denied the petition for

rehearing en banc. Judge Martin, joined by Judges

Rosenbaum and Jill Pryor, dissented. Judge Martin

argued that Willingham's immutability standard is

no longer good law in light of Price Waterhouse, in

which this Court recognized a Title VII claim where

an employer’s decision was based on sex stereotypes

concerning mutable characteristics, including dress,

demeanor, and hairstyle. App. 67a-69a (Martin, J.,

dissenting). The dissent also criticized the

13

immutability standard as unadministrable and

tangential to the key question of whether an employer

who refuses to hire a Black applicant based on a racial

stereotype has been motivated by race. App. 73a-76a,

85a. The dissent explained that the Amended

Complaint stated a plausible claim of disparate

treatment because it alleged that CMS refused to hire

Ms. Jones based on “the false racial stereotype” that

Black natural hair is “unprofessional, extreme, and

not neat,” expressed by the assumption that Iocs “tend

to get messy” even while acknowledging that

description did not in fact apply to Ms. Jones’s hair.11

App. 60a, 76a-81a.

Judge Jordan concurred in the denial of

rehearing. Judge Jordan acknowledged that tmder

Price Waterhouse, when an employer targets a

mutable trait that is linked by stereotype to a

protected class, then discrimination on the basis of

that protected class has occurred; nonetheless, he

concluded that Willinghams immutability standard

survived Price Waterhouse. App. 51a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

In departing from this Court’s precedent, the

Eleventh Circuit constricted one of the nation’s most

important civil rights statutes, which is designed to

protect the dignity of workers and ensure that an

individual’s race does not limit her employment

opportunities. 11

11 The dissent also concluded that the panel’s analysis was

flawed even when applying the immutability standard because

the Amended Complaint contained allegations that Iocs are

immutable. App. 81a-83a.

14

Based on the well-pleaded allegations in the

EEOC’s Amended Complaint, CMS refused to hire

Chastity Jones, an African-American woman, because

CMS’s representative believed that Mr. Jones’s

natural hairstyle violated the company’s grooming

policy, specifically because of the assumption that it

would “tend to get messy.” In other words, “the

complaint indicated that CMS’s only reason for

refusing to hire Ms. Jones was [a] false racial

stereotype.” App. 60a (Martin, J., dissenting). The

Complaint stated a straightforward claim for relief

under Title VII’s disparate-treatment standard.

The Eleventh Circuit, however, affirmed the

district court’s dismissal of the case on the ground

that Ms. Jones’s hairstyle was not an “immutable

characteristic,” and that CMS’s discrimination

against her was therefore beyond the purview of Title

VII. That reasoning is squarely foreclosed by this

Court’s precedent. This Court has ruled that Title VII

reaches the full spectrum of employment

discrimination related to race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin. Consistent with this principle, the

Court has specifically held that Title VII prohibits

discrimination based on stereotypes relating to one of

these protected categories, even when those

stereotypes do not concern “immutable

characteristics.” Stereotypes about appropriate

grooming in the workplace that disqualify natural

African-American hairstyles violate Title VII just as

employers who favor narrow and stereotypical

standards of appropriate hairstyles and dress for

women violate Title VII’s prohibition against gender

discrimination. Because the Eleventh Circuit has

decided an important issue of federal law in a manner

15

that departs from this Court’s precedent, certiorari is

warranted. Sup. Ct. R. 10(c).

Certiorari is also warranted because the Eleventh

Circuit’s decision conflicts with the decisions of other

federal courts of appeals on this important issue. See

Sup. Ct. R. 10(a). Applying this Court’s precedent,

courts in the First, Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth,

Seventh, and Eighth Circuits have held that Title VII

reaches discrimination based on stereotypes, without

any “immutable characteristic” limitation. Further,

the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals has held that

Title VII prohibits an employer from taking adverse

action against a Black woman because, just like Ms.

Jones here, she wore a natural hairstyle to work.

Contrary to the Eleventh Circuit’s decision below,

nothing in the statute or this Court’s precedent

authorizes federal courts to distinguish among

different Black natural hairstyles in deciding whether

an employer’s stereotyped-based racial

discrimination is prohibited by Title VII.

I. The Decision Below Contradicts this

Court’s Title VII Precedent Forbidding

Stereotype-Based Discrimination.

This Court has held that Title VII ‘“prohibit [s] all

practices in whatever form which create inequality in

employment opportunity due to discrimination on the

basis of race, religion, sex, or national origin.’”

Washington County v. Gunther, 452 U.S. 161, 180

(1981) (quoting Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424

U.S. 747, 763 (1976)). The statute requires “fair and

racially neutral employment and personnel

decisions,” and it “tolerates no racial discrimination,

subtle or otherwise.” McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801 (1973).

16

Title VII’s strict prohibition on “discrimination,

subtle or otherwise” includes discrimination based on

stereotypes. As this Court has stated with respect to

sex: “‘In forbidding employers to discriminate against

individuals because of their sex, Congress intended to

strike at the entire spectrum of disparate treatment of

men and women resulting from sex stereotypes.”’

Washington County, 452 U.S. at 180 (quoting L.A.

Dept of Water & Power v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702, 707

n.13 (1978)) (emphasis in Washington County). In

other words, “employment decisions cannot be

predicated on mere ‘stereotyped’ impressions about

the characteristics of males or females.” Manhart,

435 U.S. at 707. Indeed, “ [t]he statute’s focus on the

individual” means that “ [ejven a true generalization

about the class is an insufficient reason for

disqualifying an individual to whom the

generalization does not apply.” Id. at 708. Thus, “ [i]f

height is required for a job, a tall woman may not be

refused employment merely because, on the average,

women are too short.” Id.

These principles likewise forbid “employment

decisions . . . predicated on mere ‘stereotyped’

impressions about the characteristics” of any racial

group. Id. Race, like sex, is an expressly protected

category under Title VII, and eradicating racial

discrimination in employment was Congress’s

principal goal in enacting the statute. ‘“ [T]he very

purpose of Title VII is to promote hiring on the basis

of job qualifications, rather than on the basis of race

or color.’” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 434

(1971) (quoting 110 Cong. Rec. 7247). Indeed, while

an employer’s bona fide occupational qualification is

a lawful defense to a claim of sex discrimination, there

is no comparable defense to a claim of race

17

discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e). As this Court

explained in Manhart, Title VII was “designed to

make race irrelevant in the emploj^ment market.” 435

U.S. at 709.

Far from being “irrelevant,” race was central to

CMS’s decision to refuse to hire Ms. Jones.

Specifically, CMS’s representative relied on a racial

stereotype that Ms. Jones’s natural hairstyle could, in

the future, make her appearance unprofessional.

CMS’s representative told Ms. Jones that CMS could

not hire her “with the dreadlocks,” because ‘“they tend

to get messy, although I’m not saying yours are, but

you know what I’m talking about.’” Am. Compl. f 16.

In other words, the Complaint alleged that CMS’s

stated concern about Iocs “did not apply to Ms. Jones,

as the human resources manager acknowledged Ms.

Jones’s hair was not messy,” thereby indicating “that

CMS’s only reason for refusing to hire Ms. Jones was

the false racial stereotype.” App. 60a (Martin, J.,

dissenting). The Amended Complaint further alleged

that Iocs are “physiologically and culturally

associated with people of African descent,” Am.

Compl. ][ 28, and it explained the racialized nature of

the stereotype that Iocs are unprofessional or will

inevitably get messy, a belief “premised on a

normative standard and preference for White hair,”

id. 1 30. This belief dates back to slavery itself,

during which slave traders referred to slaves’ hair as

“dreadful” because, during the forced transport of

Africans across the Atlantic, their hair would become

matted with blood, feces, urine, sweat, tears, and dirt.

Id. K 20. The Amended Complaint explained how this

stereotype has persisted over time to shape

assumptions about Black employees who wear

18

natural hairstyles in professional settings. Id. 1U 27,

30.

Yet, despite CMS’s express reliance on a common

racial stereotype that Black natural hair is “messy” to

deny Ms. Jones employment, the district court

granted CMS’s motion to dismiss, and the Eleventh

Circuit affirmed. For both courts, the dispositive fact

requiring dismissal of the disparate-treatment claim

was that the EEOC had not alleged that Iocs are

“immutable traits” or “immutable characteristics” of

Black people. In the Eleventh Circuit’s words, “our

precedent holds that Title VII prohibits

discrimination based on immutable traits, and the

proposed amended complaint does not assert that

dreadlocks—though culturally associated with r a c e -

are an immutable characteristic of black persons.”

App. 2a; see also App. 22a-23a (similar); App. 42a

(district court opinion) (holding that the complaint

failed to state a claim because Ms. Jones’s “hairstyle .

. . is a mutable characteristic”).

The lower courts’ reasoning finds no support in

Title VII, and it is contrary to this Court’s precedent

that Title VII reaches the full spectrum of

employment discrimination. Price Waterhouse v.

Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), is directly on point. In

that case, Ann Hopkins presented evidence that she

was denied a promotion because of her employer’s sex-

based stereotypes, but “ [n]one of the traits the

employer identified as its reasons for not promoting

Ms. Hopkins were immutable.” App. 66a (Martin, J.,

dissenting). Instead, the stereotypes were that Ms.

Hopkins’s personality and appearance—including her

hairstyle—were too masculine. In the words of one of

the Price Waterhouse partners who advised Ms.

Hopkins about why she was denied a promotion, she

19

should ‘“walk more femininely, talk more femininely,

dress more femininely, wear make-up, have her hair

styled, and wear jewelry.’” Price Waterhouse, 490 U.S.

at 235 (emphasis added).

Yet, far from rejecting Ms. Hopkins’s claims on

the basis that her employer’s sex-based stereotypes

involved mutable characteristics, this Court “held

that discrimination on the basis of these traits, which

Ms. Hopkins could but did not change, constituted sex

discrimination. The Court explained that

discrimination on the basis of these mutable

characteristics—how a woman talks, dresses, or

styles her hair—showed discrimination on the basis

of sex.” App. 66a (Martin, J. dissenting) (discussing

Price Waterhouse).

Indeed, although members of this Court

disagreed about other issues in Price Waterhouse, the

Court was united on this point. The four-justice

plurality explained that when an employer acts on

“stereotypical notions about women’s proper

deportment,” 490 U.S. at 256, it has “acted on the

basis of gender” in violation of Title VII, id. at 250; see

also id. at 251, 255. Similarly, in her opinion

concurring in the judgment, Justice O’Connor

recognized that Ms. Hopkins had provided “direct

evidence of discriminatory animus,” by proving that

Price Waterhouse ‘“permitted stereotypical attitudes

towards women’” to play a significant role in denying

her a promotion. Id. at 271-72 (quoting Court of

Appeals’ decision). Because Ms. Hopkins had proven

that sex-based stereotypes were a substantial factor

in the denial of her promotion, the burden was on

Price Waterhouse to show that it would have made

the same decision even absent those stereotypes. See

id. at 261, 272-73. Justice White, in a separate

20

opinion concurring in the judgment, agreed that Ms.

Hopkins’s evidence supported the district court’s

finding that an “unlawful motive was a substantial

factor” in the denial of a promotion, such that the

burden shifted to Price Waterhouse to show ‘“that it

would have reached the same decision in the absence

o f the unlawful motive.”12 Id. at 259-60 (citation,

emphasis, and alteration omitted).

The dissent in Price Waterhouse also recognized

that employment decisions based on sex-based

stereotypes are forbidden by Title VII. Justice

Kennedy, joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and

Justice Scalia, explained that Ms. Hopkins had

“presented a strong case . . . of the presence of

discrimination in Price Waterhouse’s partnership

process,” such that the “decision was for the finder of

fact,” as to whether or not “sex discrimination caused

the adverse decision.” Id. at 295. In the dissent’s

view, however, the district court’s findings showed

that Ms. Hopkins was ultimately denied promotion * VII,

12 In the Civil Rights Act of 1991, Congress abrogated the aspect

of Price Waterhouse’s holding related to the burden of proof in

mixed motive cases. The 1991 Act added Section 703(m) to Title

VII, clarifying that if discrimination on the basis of a protected

category is “a motivating factor” for an employment decision,

then a violation of Title VII has occurred, regardless of whether

“other factors also motivated the practice.” Civil Rights Act of

1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, § 107(a), 105 Stat. 1071, 1075 (1991)

(codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(m)). The EEOC

grounded its claims in the instant case in this section as well as

Section 703(a). Compl. ^7. While there is nothing in the record

to suggest CMS’s refusal to hire Ms. Jones was based on

anything other than racial stereotypes about her hair, even if

there were other considerations, the EEOC’s claim remains valid

because it has plausibly alleged that a false racial stereotype was

“a motivating factor” in CMS’s decision. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(m).

21

for reasons other than Price Waterhouse’s sex-

stereotyped discrimination. See id. In other words,

the dissent recognized that Title VII forbids

stereotyped-based discrimination related to mutable

characteristics. It simply concluded that Ms. Hopkins

was not entitled to relief under Title VII because the

district court (after a trial) had found that she was

denied a promotion for reasons other than

stereotyped-based discrimination. See id.

In sum, as Judge Martin explained in dissenting

from the denial of rehearing below, “ [t]he lesson of

Price Waterhouse is clear. An employment decision

based on a stereotype associated with the employee’s

protected class may be disparate treatment under

Title VII even when the stereotyped trait is not an

‘immutable’ biological characteristic of the employee.”

App. 67a. Here, the well-pleaded allegations in the

EEOC’s Amended Complaint show that CMS made an

“employment decision based on a stereotype

associated with [Ms. Jones’s] protected class,” and

therefore the Amended Complaint states a claim for

disparate treatment even though “the stereotyped

trait is not an ‘immutable’” characteristic. Id.

In reaching a contrary conclusion, the Eleventh

Circuit panel did not cite Price Waterhouse, nor did it

attempt to explain how its reasoning was consistent

with this Court’s precedent holding that Title VII

prohibits stereotyped-based discrimination. Indeed,

although the panel acknowledged that the EEOC had

argued that “targeting dreadlocks as a basis for

employment can be a form of racial stereotyping,”

App. 8a-9a, it did not address that argument.

Judge Jordan did address Price Waterhouse in his

opinion concurring in the denial of en banc rehearing,

22

which no other judge joined. However, his analysis

only underscores the inconsistency between the

panel’s opinion and this Court’s precedent. In his

concurring opinion, Judge Jordan stated that Price

Waterhouse “did not hold that Title VII protects

mutable characteristics.” App. 51a (Jordan, J.,

concurring). But the issue is not whether Title VII

protects mutable characteristics, it is whether Title

VII’s prohibition on stereotyped-based discrimination

includes stereotypes related to mutable

characteristics. And, as Judge Jordan recognized,

Price Waterhouse makes clear that Title VII does

prohibit such discrimination because the stereotype

connects the mutable trait to the protected category:

[Wjhen an employer makes a decision

based on a mutable characteristic

(demeanor) that is linked by stereotype

(how women should behave) to one of

Title VII’s protected categories (a

person’s sex), the decision may be

impermissibly based on a protected

category, so the attack on the mutable

characteristic is legally relevant to the

disparate-treatment claim.

App. 52a.

That is as true here as it was in Price Waterhouse.

CMS made a “decision based on a mutable

characteristic” (natural hair Iocs) “that is linked by

stereotype” (that Black natural hairstyles are

unprofessional or tend to get messy) “to one of Title

VII’s protected categories” (race). Id.

The issue here is not whether Iocs are immutable,

just as the issue in Price Waterhouse was not whether

Ms. Hopkins hairstyle, dress, or comportment were

23

immutable. As Judge Martin explained, “Price

Waterhouse teaches that, for purposes of Title VII, it

does not matter whether the trait the employer

disfavors is mutable or immutable. What matters is

whether that trait is linked, by stereotype, to a

protected category.” App. 77a. (Martin, J.,

dissenting). Regardless of their mutability, Iocs are

“linked, by stereotype, to [the] protected category” of

race, id., which means that the Amended Complaint

states a plausible claim for race discrimination.

The Eleventh Circuit’s contrary focus led it astray

from the proper role of a federal court in applying

Title VII. The panel sought to distinguish between

discrimination targeting Black employees with afro

hairstyles (protected under Title VII) and those with

Iocs (supposedly unprotected under Title VII). App.

22a-23a. In defending that distinction, Judge Jordan

asserted that an afro style is protected because—

although not immutable in the sense that it cannot be

altered—it is a Black person’s hair in its “natural

state.” App. 55a. By contrast, he concluded that Iocs

are unprotected because they are not “a black

individual’s hair in its natural, unmediated state.”

Id. But, Judge Jordan’s distinction fails on its own

terms. The EEOC’s complaint specifically alleges

that, just like an afro, Iocs are a “natural style,” as

they “are formed in a Black person’s hair naturally,

without any manipulation, or by the manual

manipulation of hair into larger coils of hair.” Am.

Compl. ̂ 19. Furthermore, an afro is not a purely

unmediated hairstyle but requires care and attention

to develop and maintain the style, including routine

detangling, moisturizing, and at times, the use of

24

braids during a growing-out phase.13 The distinction

between such “mediation” and that required for Iocs

is arbitrary.

More important, Title VII does not authorize

federal courts to inquire into how “natural” a Black

person’s hairstyle is, how much “mediation” is

required as part of that style, or the degree to which

a trait can be “masked” versus “alter [ed]” in

determining whether a complaint should proceed.

App. 55a. As Judge Martin explained, “ [sjurely, the

viability of Title VII cannot rest on judges drawing

distinctions between Afros and dreadlocks.” App.

85a. Both are presentations of Black natural hair.

The panel’s contrary “opinion requires courts and

litigants to engage in a pseudo-scientific analysis of

which racial traits occur naturally and which do not.

This is not how we should be deciding claims of race

discrimination.” Id.

Finally, Judge Jordan stated that “ [tjhere is even

disagreement over whether dreadlocks are

exclusively (or even primarily) of African descent,”

citing a source for the proposition that the first

written evidence of dreadlocks is in the Vedic

scriptures, which are of Indian origin. App. 59a.

(Jordan, J., concurring). But, for the reasons

explained above, the issue in this case is not whether

Iocs are exclusively or originally traits of Black

people. The issue is whether, in denying Ms. Jones

13 See generally Funmi Fetto, How to Guide: Tips for Caring for

Afro Hair, GLAMOUR (June 15, 2016),

http://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/how-to-care-for-afro-

hair; John-John Williams IV, Afros, Dreads, Natural Styles More

Popular, Still Controversial, BALT. SUN (Mar. 4, 2015),

http://www.baltimoresun.com/features/fashion-style/bs-lt-

natural-hair- 20150304- story .html.

http://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/how-to-care-for-afro-hair

http://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/how-to-care-for-afro-hair

http://www.baltimoresun.com/features/fashion-style/bs-lt-natural-hair-

http://www.baltimoresun.com/features/fashion-style/bs-lt-natural-hair-

25

employment, CMS relied on a stereotype associated

with Ms. Jones’s race. This Court “need not leave . . .

common sense at the doorstep” in applying Title VII.

Price Waterhouse, 490 U.S. at 241 (plurality opinion).

In this country and most others, Iocs are principally

associated with people of African descent, as is the

false stereotype that Iocs are or tend to get messy. As

the Amended Complaint “clearly alleged, . . .

dreadlocks are a stereotyped trait of African

Americans,” and the “perception that dreadlocks are

‘unprofessional’ and ‘not neat’ is grounded in a deep-

seated white cultural association between black hair

and dirtiness,” which “has origins in slavery.” App.

78a (Martin, J., dissenting) (citing amended

complaint). At the motion to dismiss stage, those

allegations raised a reasonable inference that the

stereotype CMS relied on was related to Ms. Jones’s

race as an African-American woman. Ashcroft u.

Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009) (recognizing that a

motion to dismiss should be denied when “the plaintiff

pleads factual content that allows the court to draw

the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable

for the misconduct alleged”).

As such, the EEOC stated a claim for relief under

Title VII.

For all the foregoing reasons, the Eleventh

Circuit’s decision in this case conflicts with the

relevant decisions of this Court on a question of

federal law. Sup. Ct. R. 10(c). And that question is

an important one. It goes to the heart of the ability of

Black women to compete in the workplace, free from

stereotypes about whether their natural hair conflicts

with a presentation of professionalism. As this Court

has stressed in a Title VII case, ‘“ [t]he prohibitions

against discrimination contained in the Civil Rights

26

Act of 1964 reflect an important national policy.’” St.

Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502, 524 (1993)

(quoting U.S. Postal Seru. Bd. of Governors v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711, 716 (1983)). “In passing Title VII,

Congress made the simple but momentous

announcement that sex, race, religion, and national

origin are not relevant to the selection, evaluation, or

compensation of employees.” Price Waterhouse, 490

U.S. at 239 (plurality opinion). By prohibiting racial

discrimination in employment, the statute is designed

to ensure that individuals have equal opportunities to

obtain economic security and mobility regardless of

race.

Here, the Eleventh Circuit misinterpreted Title

VII as having no application to stereotype-based

discrimination if the stereotyped trait is not

immutable. “And it does so in very broad terms.”

App. 70a (Martin, J., dissenting). This case involves

a hairstyle, but there is no basis for limiting the

panel’s holding that stereotype-based discrimination

is not actionable unless the stereotype relates to an

immutable characteristic. As a result, the “panel

opinion forces courts in Alabama, Florida, and

Georgia to close their eyes to compelling evidence of

discriminatory intent.” App. 76a. This is also not the

first time the Eleventh Circuit has denied relief in a

Title VII case by imposing a categorial rule that has

no basis in this Court’s precedent. See Ash v. Tyson

Foods, Inc., 546 U.S. 454, 456 (2006) (per curiam)

(summarily vacating Eleventh Circuit decision that a

manager’s calling Black employees “boy” was

categorically not probative of racial discrimination

under Title VII).

27

Petitioner respectfully urges this Court to grant

certiorari to address the direct inconsistency between

the decision below and this Court’s precedent.

II. The Decision Below Conflicts with

Decisions of Other Federal Circuits

Concerning Title VIPs Prohibition on

Stereotype-Based Discrimination.

As set forth supra, this Court’s precedent is clear

that Title VII reaches stereotype-based

discrimination. Thus, it is unsurprising that the

Eleventh Circuit is alone in holding that Title VII

categorically does not apply to discrimination related

to traits that are “mutable,” even when the

discrimination is rooted in stereotypes related to a

protected category. Appellate courts in the First,

Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth

Circuits, have each followed this Court’s precedent

and recognized that Title VII prohibits employment

practices that are based on stereotypes related to

mutable characteristics. Additionally, the First

Circuit has explicitly recognized that this Court’s

holding in Price Waterhouse regarding gender-based

stereotypes necessarily extends to racial stereotypes

and, directly on point here, the Seventh Circuit has

held Title VII prohibits an employer from taking

adverse action against a Black woman because, like

Ms. Jones, she had a natural hairstyle. The Eleventh

Circuit’s holding that Title VII cannot apply to

discrimination related to a “mutable” characteristic,

even if an adverse employment decision is based on a

racial stereotype related to that characteristic,

conflicts with the decisions of multiple other appellate

courts and creates a circuit split on this important

issue. Sup. Ct. R. 10(a).

28

A. The Majority of Circuits Follow Price

W aterhouse Without Applying an

Immutability Test.

Multiple circuits have followed this Court’s

reasoning in Price Waterhouse and held that

discrimination based on stereotype is fully within

Title VII’s purview. In Chadwick v. WellPoint, Inc.,

561 F.3d 38 (1st Cir. 2009), for example, the court of

appeals held that the non-promotion of a woman with

children was actionable because it was based on the

gender-based stereotype that mothers, particularly

those with young children, neglect their work duties

due to childcare obligations. Id. at 42, 45-48. “Given

what we know about societal stereotypes regarding

working women with children,” the First Circuit

rejected the district court’s conclusion that there was

no evidence this stereotype was based on sex rather

than a gender-neutral assumption about parents with

children. Id. at 46-47.

In Back v. Hastings On Hudson Union Free Sch.

Dist., 365 F.3d 107 (2d Cir. 2004), the Second Circuit

reversed the district court’s entry of summary

judgment to an employer under Title VII, holding that

“stereotyped remarks can certainly be evidence that

gender played a part in an adverse employment

decision.” Id. at 119 (quotation marks and citation

omitted). More recently, the Second Circuit again

relied on settled law that Title VII reaches

employment discrimination based on stereotypes

when it held in Zarda v. Altitude Express, Inc., 883

F.3d 100 (2d Cir. 2018) (en banc), that discrimination

on the basis of sexual orientation is actionable in part

because it is discrimination based on non-conformity

with gender norms. See id. at 121 (“The gender

stereotype at work here is that ‘real’ men should date

29

women, and not other men.”) (citation and quotation

marks omitted).

Moreover, other circuits have applied this

principle when (as in Price Waterhouse itself), the

stereotype at issue concerned mutable aspects of a

person’s appearance. In Bibby v. Phila. Coca Cola

Bottling Co., 260 F.3d 257 (3d Cir. 2001), the Third

Circuit recognized a Title VII claim where the male

plaintiff had been a target of harassment from his co

workers based on the stereotype that his wearing an

earring was “not sufficiently masculine.” Id. at 264.

Similarly, in Lewis v. Heartland Inns of Am., LLC,

591 F.3d 1033, 1042 (8th Cir. 2010), the Eighth

Circuit ruled that a terminated female employee who

dressed in a “tomboyish” manner with short hair and

no makeup had an actionable claim for discrimination

based on gender stereotypes in light of her

supervisor’s stated preference for “pretty” staff

members with the “Midwestern girl look.” Id. at 1041.

Indeed, other than the decision below, the courts

of appeals have consistently recognized that

stereotyped-based discrimination violates Title VII.

In EEOC v. Boh Bros. Const. Co., 731 F.3d 444 (5th

Cir. 2013) (en banc), the Fifth Circuit relied on Price

Waterhouse to hold that sexual harassment based on

gender stereotyping violates Title VII. The Court of

Appeals also cited numerous other cases expressly

recognizing stereotype-based claims under Title VII

in the gender discrimination context. Id. at 454 & n.4

(citing Glenn v. Brumby, 663 F.3d 1312, 1316 (11th

Cir. 2011); Lewis, 591 F.3d at 1038; Chadwick, 561

F.3d at 44; Smith v. City of Salem, 378 F.3d 566, 573

(6th Cir. 2004); Back, 365 F.3d at 120; Nichols v.

Azteca Rest. Enters., 256 F.3d 864, 874-75 (9th Cir.

30

2001); Bibby, 260 F.3d at 263-64 (3d Cir. 2001); and

Doe v. City of Belleville, 119 F.3d 563, 580 (7th Cir.

1997), vacated on other grounds, 523 U.S. 1001

(1998)).

None of these cases undertook an analysis of

whether the characteristics to which the stereotype

relates were mutable or immutable. Pregnancy and

parenthood, for example, cannot be said to be

immutable, nor can conformance with gender norms

regarding dress, makeup, or deportment. The claims

endorsed by multiple circuits would not have

withstood the immutability test created by the court

below.

B. Other Circuits Have Specifically Held

that Title VII Prohibits Adverse

Employment Actions Based on Racial

Stereotypes.

Although the majority of the jurisprudence

related to stereotype-based discrimination under

Title VII has been in the context of sex discrimination,

those principles are fully applicable in the context of

racial discrimination. In Thomas v. Eastman Kodak

Co., 183 F.3d 38 (1st Cir. 1999), the First Circuit

reversed a grant of summary judgment to the

employer and recognized a Title VII claim on the basis

of racial stereotypes. In direct contradiction to the

Eleventh Circuit’s decision in the instant case, the

First Circuit explained that “Title VII’s prohibition

against ‘disparate treatment because of race’ extends

both to employer acts based on conscious racial

animus and to employer decisions that are based on

stereotyped thinking or other forms of less conscious

bias.” Id. at 42. The court held that “ [t]he ultimate

question is whether the employee has been treated

31

disparately ‘because of race.’ This is so regardless of

whether the employer consciously intended to base

[employment practices] on race, or simply did so

because of unthinking stereotypes or bias.” Id. at 58.

The Seventh Circuit’s decision in Jenkins v. Blue

Cross Mut. Hosp. Ins., 538 F.2d 164 (7th Cir. 1976)

(en banc), is particularly instructive. In Jenkins, as

here, the alleged discrimination was based on a

stereotype that a natural Black hairstyle was

inappropriate. Id. at 165. Although Jenkins predated

Price Waterhouse, the Seventh Circuit’s analysis was

fully consistent with this Court’s subsequent decision

in that case. The Seventh Circuit did not attempt to

classify the plaintiff s hairstyle as either a mutable or

immutable characteristic, but reasoned:

[The plaintiff] said that her supervisor

denied her a promotion because she

“could never represent Blue Cross with

[her] Afro.” A lay person’s description of

racial discrimination could hardly be

more explicit. The reference to the Afro

hairstyle was merely the method by

which the plaintiff s supervisor allegedly

expressed the employer’s racial

discrimination.

Id. at 168.

The Eleventh Circuit sought to reconcile the

decision below with Jenkins by attempting to

distinguish between afros and Iocs, but that

distinction is untenable. Afros and Iocs are both

Black natural hairstyles, but neither is immutable in

the sense that it cannot be changed. See supra at 23-

24. In Jenkins, the court held that discrimination on

the basis of racialized stereotypes concerning Black

32

natural hairstyles violates Title VII. By contrast, the

court below held the opposite, thereby dismissing Ms.

Jones’s allegations that the discrimination she

suffered was actionable because it was rooted in racial

stereotyping.

Two other circuit decisions have similarly

recognized the significance of discrimination based on

racial stereotypes under Title VII. In Smith u. Wilson,

705 F.3d 674 (7th Cir. 2013), the Seventh Circuit

upheld a jury verdict against a plaintiff in a Title VII

racial discrimination case on other grounds; however,

citing Price Waterhouse, the Court of Appeals

emphasized that “ [w]e are mindful that certain

ostensibly neutral bases for a hiring decision may be

predicated on impermissible stereotypes and biases.”

Id. at 678. In Satz v. ITT Fin. Corp., 619 F.2d 738

(8th Cir. 1980), the Eighth Circuit—prior to Price

Waterhouse—observed that courts analyzing Title VII

disparate treatment claims often consider the

“potential for stereotyping of employees on the basis

of their sex or race.” Id. at 746.

In the instant case, the Eleventh Circuit failed to

recognize the significance of such stereotypes.

Instead, it relied on a rigid dichotomy—which finds

no support in the text of Title VII, this Court’s

precedent, or the decisions of other courts of appeal—

that purports to distinguish between characteristics

that are “mutable” and “immutable.” Such a

distinction ignores both common sense and the clear

precedent of this Court—followed by every other

appellate court that has considered the question—

that discrimination based on stereotype is actionable

under Title VII regardless of whether it is connected

to a purportedly immutable characteristic.

33

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Chastity Jones

respectfully requests that this petition for writ of

certiorari be granted.

Respectfully Submitted,

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital*

Jin Hee Lee

Rachel M. Kleinman

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street,

5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

sspital@naacpldf.org

April 4, 2018

Jennifer A. Holmes

Daniel S. Harawa

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 I Street, NW

10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

Counsel for Petitioner

Chastity Jones

* Counsel of Record

mailto:sspital@naacpldf.org

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX A

[PUBLISH]

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 14-13482

D.C. Docket No. l:13-cv-00476-CB-M

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

versus

CATASTROPHE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

(December 13, 2016)

Before JORDAN and JULIE CARNES, Circuit Judges,

and ROBRENO, ‘District Judge.

JORDAN, Circuit Judge:

We withdraw our previous opinion, dated

September 15, 2016, and published at 837 F.3d 1156,

and issue this revised opinion:

The Honorable Eduardo Robreno, United States District

Judge for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, sitting by

designation.

2a

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

filed suit on behalf of Chastity Jones, a black job

applicant whose offer of employment was rescinded by

Catastrophe Management Solutions pursuant to its

race-neutral grooming policy when she refused to cut

off her dreadlocks. The EEOC alleged that CMS’

conduct constituted discrimination on the basis of Ms.

Jones’ race in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-2(a)(l) & 2000e-2(m).

The district court dismissed the complaint under

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) because it did

not plausibly allege intentional racial discrimination

by CMS against Ms. Jones. See E.E.O.C. v.

Catastrophe Mgmt. Solutions, 11 F. Supp. 3d 1139,

1142-44 (S.D. Ala. 2014). The district court also

denied the EEOC’s motion for leave to amend,

concluding that the proposed amended complaint

would be futile. The EEOC appealed.

With the benefit of oral argument, we affirm. First,

the EEOC—in its proposed amended complaint and in

its briefs—conflates the distinct Title VII theories of

disparate treatment (the sole theory on which it is

proceeding) and disparate impact (the theory it has

expressly disclaimed). Second, our precedent holds

that Title VII prohibits discrimination based on

immutable traits, and the proposed amended

complaint does not assert that dreadlocks—though

culturally associated with race—are an immutable

characteristic of black persons. Third, we are not

persuaded by the guidance in the EEOC’s Compliance

Manual because it conflicts with the position taken by

the EEOC in an earlier administrative appeal, and

because the EEOC has not persuasively explained why

it changed course. Fourth, no court has accepted the

3a

EEOC’s view of Title VII in a scenario like this one,

and the allegations in the proposed amended

complaint do not set out a plausible claim that CMS

intentionally discriminated against Ms. Jones on the

basis of her race.

I

The EEOC relies on the allegations in its proposed

amended complaint, see Br. of EEOC at 2-6, so we set

out those allegations below.

A

CMS, a claims processing company located in

Mobile, Alabama, provides customer service support to

insurance companies. In 2010, CMS announced that it

was seeking candidates with basic computer

knowledge and professional phone skills to work as

customer service representatives. CMS’ customer

representatives do not have contact with the public, as

they handle telephone calls in a large call room.

Ms. Jones, who is black, completed an online

employment application for the customer service

position in May of 2010, and was selected for an in-

person interview. She arrived at CMS for her

interview several days later dressed in a blue business

suit and wearing her hair in short dreadlocks.

After waiting with a number of other applicants,

Ms. Jones interviewed with a company representative

to discuss the requirements of the position. A short

time later, Ms. Jones and other selected applicants

were brought into a room as a group.

CMS’ human resources manager, Jeannie

Wilson—who is white—informed the applicants in the

4a

room, including Ms. Jones, that they had been hired.

Ms. Wilson also told the successful applicants that

they would have to complete scheduled lab tests and

other paperwork before beginning their employment,

and she offered to meet privately with anyone who had

a conflict with CMS’ schedule. As of this time no one