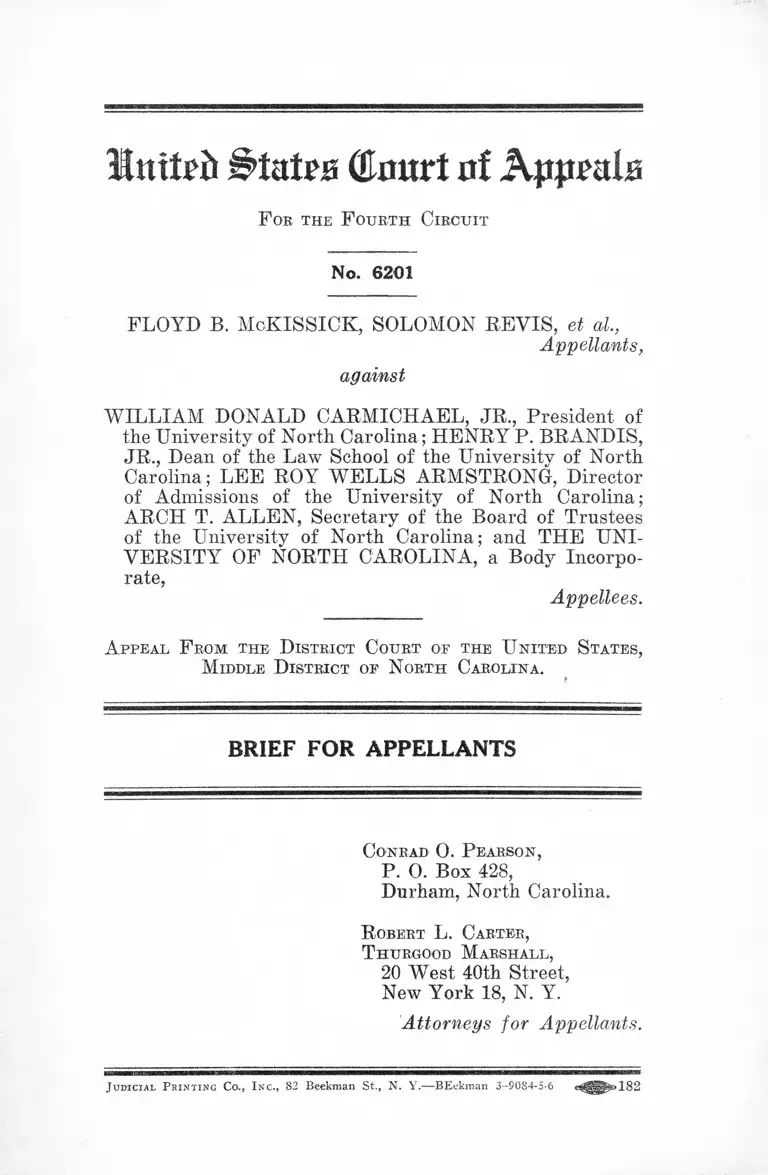

McKissick v. Carmichael Jr. Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 15, 1951

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKissick v. Carmichael Jr. Brief for Appellants, 1951. 9ae48dae-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2ee0654b-15d9-477b-bbed-9a119ed35269/mckissick-v-carmichael-jr-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

InitfiJ Stall's (fiuurt of Apprala

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 6201

FLOYD B. MoKISSICK, SOLOMON KEYIS, et al,

Appellants,

against

WILLIAM DONALD CARMICHAEL, JR., President of

the University of North Carolina; HENRY P. BRANDIS,

JR., Dean of the Law School of the University of North

Carolina; LEE ROY WELLS ARMSTRONG, Director

of Admissions of the University of North Carolina;

ARCH T. ALLEN, Secretary of the Board of Trustees

of the University of North Carolina; and THE UNI

VERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, a Body Incorpo

rate,

Appellees.

A ppeal F rom the D istrict Court of the U nited States,

Middle D istrict of North Carolina.

*

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Conrad 0 . P earson,

P. O. Box 428,

Durham, North Carolina.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants.

J u d ic ia l P r in t in g Co., I n c ., 82 Beekman St., N. Y.— BEekman 3-9084-5-6 1 8 2

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ................. 1

Statement of Pacts ....................................................... 3

Argument ........................................... 3

The decision of the United States Supreme Court

in Sweatt v. Painter is controlling here, and

under the principles enunciated in that case,

appellants must be admitted to the University

of North Carolina School of Law forthwith . . . 3

Conclusion ........................................................................ 13

T able of Cases

Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540 . . . . 4

Continental Baking Co. v. Woodring, 286 U. S. 353 . . . 5

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265 ................... 5

Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464 ................................ 5

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................... 5

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 ................. 5

Maxwell v. Bugbee, 250 U. S. 525 ................................ 4

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266 ............... 5

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 ........4, 5,13

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . . 4

11 I N D E X

PAGE

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ............................ 5

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ................................ 5

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 IT. S. 389 . . 5

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 IT. S. 631 ................... 4

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535 .............................. 5

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 IT. S. 400 ......... 4, 5

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303 ..................... 4

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ............. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8,12,13

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 ......................................... ...................................... 4,5

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 3 3 ........................................... 5

United States (Gnurt of Appeals

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 6201

FLOYD B. McKISSICK, SOLOMON EEVIS, et al,

Appellants,

against

WILLIAM DONALD CARMICHAEL, JR., President of

the University of North Carolina; HENRYP. BRANDIS,

JR., Dean of the Law School of the University of North

Carolina; LEE ROY WELLS ARMSTRONG, Director

of Admissions of the University of North Carolina;

ARCH T. ALLEN, Secretary of the Board of Trustees

of the University of North Carolina; and THE UNI

VERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, a Body Incorpo

rate,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

The instant cause of action was commenced on October

25, 1949, by Harold Epps and Robert Glass, the original

complainants in the Court below, as a class suit on behalf of

themselves and all other Negroes similarly situated. While

the cause was there pending, Floyd B. McKissiek, Solomon

Revis, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee and several other

persons were permitted to intervene as parties-plaintiff.

The original plaintiffs and the other intervenors were per

mitted to withdraw without prejudice for reasons set out

2

in the record, leaving the four above-named parties as

plaintiffs at the trial in the Court below and as appellants

in this Court (R. 25, 26 )d

A trial on the merits took place on August 28-30, 1950,

in the Durham Division of the United States District Court

for the Middle District of North Carolina before the Court

without a jury. On October 9, 1950, appellants’ cause of

action wTas dismissed on the grounds that the state afforded

them at the law school of the North Carolina College for

Negroes in Durham, North Carolina, facilities and oppor

tunities substantially equal to those offered to all other

persons at the law school of the University of North Caro

lina in Chapel Hill. The Court’s opinion is reported in

93 F. Supp. 327, and its final decree, entered the same day,

is to be found in the record at page 290. From the final

judgment dismissing the complaint, appellants brought

the cause here. The notice of appeal was filed on October

26, 1950.

The sole issue pressed here, and in the court below, is

whether refusal to admit appellants to the University of

North Carolina School of Law solely because of their race

and color constitutes a deprivation of rights secured under

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Appellants contend that the facilities and opportunities

available to them at the College Law School are not equal

to those available at the University Law School,1 2 and that

the only way the rights guaranteed to them under the

Fourteenth Amendment can be secured is by their admis

sion to the University Law School on the same basis as

other students.

1. The record citations here are the citations of the page numbers as they

appear in the appendix to appellants’ brief.

2. When the term “ College Law School’ ’ is used, it will refer to the law

school of the North Carolina College for Negroes at Durham, and when the

term “ University Law School” is used, it will refer to the law school of the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

3

Statement of Facts

Appellants are citizens of the United States and resi

dents of the State of North Carolina. They are at present

attending the law school at the North Carolina College for

Negroes, a public institution maintained and supported out

of state funds to provide legal training exclusively and

solely for Negroes in accord with the state’s policy, custom,

practice and usage of providing separate educational facili

ties for Negroes in public institutions within the State of

North Carolina.

Appellants made appropriate application for admission

to the University of North Carolina School of Law, and

were refused admission solely because of race and color.

It is conceded that appellants possess all the requisite

requirements for admission to the University Law School

and would have been admitted except for the fact that

they are Negroes (E. 7, 13, 24, 215).

ARGUMENT

The decision of the United States Supreme Court

in Sweatt v. Painter is controlling here, and under the

principles enunciated in that case, appellants must be

admitted to the University of North Carolina School of

Law forthwith.

It is admitted that appellants satisfy all the require

ments for admission to the University of North Carolina

School of Law and were denied admission thereto solely

because of their race and color. Appellees seek to justify

this refusal on the grounds that the state is maintaining

and operating a law school for Negroes at Durham, North

Carolina, which affords to appellants opportunities and

facilities substantially equivalent to those offered to all

4

other persons at the University of North Carolina. It is

contended that the maintenance by the state of the College

Law School for Negroes satisfies the requirements of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and

that in refusing to admit appellants and all other Negroes

to the University Law School no deprivation of constitu

tional rights has been committed.

It is now clear beyond question that once a state under

takes to provide educational facilities for white persons,

it must provide equal facilities for Negroes, Missouri ex rel

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, and at the same time,

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631. It is also clear

that the mere furnishing of a separate facility for Negroes

does not in itself satisfy the requirements which the Four

teenth Amendment imposes, Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629. Indeed, the state’s obligations under the Fourteenth

Amendment are not met when, because of considerations of

race and color, it requires persons to study law in isolation

from a substantial and significant segment of the popula

tion, or when, at the graduate and professional school

levels of state universities, it attempts to impose or to

enforce any distinctions or classifications based upon race

or color. Sweatt v. Painter, supra; McLaurin v. Board

of Regents, 339 U. 8. 637.

These decisions are a logical application of long-settled

constitutional doctrine as to the purposes and intendment

of the Fourteenth Amendment. One of the basic principles

of constitutional law is that all persons similarly situated

must be treated alike by the state, Southern Railway Co.

v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400; Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co.,

184 U. S. 540; Maxwell v. Bugbee, 250 U. S. 525, and that

a state cannot deny to any person because of race or color

any advantage or opportunity it offers to other persons.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303; Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, supra; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra;

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410.

5

Legislative distinctions and classifications are only permis

sible when based upon a real or substantial difference which

has pertinence to the legislative objective. Quaker City

Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389; Southern Railway

Co. v. Greene, supra; Truax v. Raich, 239 IT. S. 33; May

flower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 IT. S. 266; Skinner v. Okla

homa, 316 IT. S. 535; Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 IT. S.

265; Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464; Continental Bak

ing Co. v. Woodring, 286 U. S. 353. A legislative classifi

cation or distinction based upon race and color is consid

ered irrational and irrelevant, see Ilirabayashi v. United

States, 320 U. S. 81; Korematsu v. United States, 323 IT. 8.

214, and such distinctions when imposed by the state have

been held to overreach the limitations set by the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Takahashi

v. Fish and Game Commission, supra; Oyama v. California,

332 U. S. 633.

Yet, prior to decision by the United States Supreme

Court in the Sweatt and McLaurin cases, it was considered

possible for a state to avoid having its racially imposed

classifications or distinctions struck down by affording

separate facilities for Negroes under the separate but

equal theory of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537. What

ever may be the impact of this theory on the limitations of

a state’s power to impose racial classifications and distinc

tions in general, it is clear that in the area of state gradu

ate and professional educational facilities, the doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson is now without significance.

No proper decision, therefore, can now be made as to the

legality of segregation laws, practices, customs or usages

in the field of legal education without careful analysis of

the reach of these two recent Supreme Court pronounce

ments. The Court attempted to determine appellants’

rights in this cause as if the Sweatt and McLaurin cases

had never been decided, and in so doing, we submit, fell

into fatal error.

6

If the Court below had adopted the rationale of the Su

preme Court in the Sweatt case, no conclusion would have

been possible other than that appellants are entitled to ad

mission to the law school of the University of North Caro

lina.

In that case, the Court in holding that petitioner was en

titled to be admitted to the University of Texas School of

Law stated at pages 632-635:

4 4 The University of Texas Law School, from which

petitioner was excluded, was staffed by a faculty

of sixteen full-time and three part-time professors,

some of whom are nationally recognized authorities

in their field. Its student body numbered 850. The

library contained over 65,000 volumes. Among the

other facilities available to the students were a law

review, moot court facilities, scholarship funds, and

Order of the Coif affiliation. The school’s alumni

occupy the most distinguished positions in the private

practice of the law and in the public life of the State.

It may properly be considered one of the nation’s

ranking law schools.

“ The law school for Negroes which was to have

opened in February, 1947, would have had no in

dependent faculty or library. The teaching was to

be carried on by four members of the University of

Texas Law School faculty, who were to maintain

their offices at the University of Texas while teaching

at both institutions. Few of the 10,000 volumes

ordered for the library had arrived; nor was there

any full-time librarian. The school lacked accredita

tion.

“ Since the trial of this case, respondents report

the opening of a law school at the Texas State Uni

versity for Negroes. It is apparently on the road to

full accreditation. It has a faculty of five full-time

professors; a student body of 23; a library of some

16,500 volumes serviced by a full-time staff; a prac

tice court and legal aid association; and one alumnus

who has become a member of the Texas Bar.

7

“ Whether the University of Texas Law School

is compared with the original or the new law school

for Negroes, we cannot find substantial equality in

the educational opportunities offered white and

Negro law students by the State. In terms of num

ber of the faculty, variety of courses and opportunity

for specialization, size of the student body, scope of

the library, availability of law review and similar

activities, the University of Texas Law School is

superior. What is more important, the University

of Texas Law School possesses to a far greater de

gree those qualities which are incapable of objective

measurement but which make for greatness in a law

school. Such qualities, to name but a few, include

reputation of the faculty, experience of the admin

istration, position and influence of the alumni, stand

ing in the community, traditions and prestige. It is

difficult to believe that one who had a, free choice

between these law schools would consider the ques

tion close.

“ Moreover, although the law is a highly learned

profession, we are well aware that it is an intensely

practical one. The law school, the proving ground

for legal learning and practice, cannot be effective

in isolation from the individuals and institutions

with which the law interacts. Few students and no

one who has practiced law would choose to study in

an academic vacuum, removed from the interplay

of ideas and the exchange of views with which the

law is concerned. The law school to which Texas is

willing to admit petitioner excludes from its student

body members of the racial groups which number

85% of the population of the State and include most

of the lawyers, witnesses, jurors, judges and other

officials with whom petitioner will inevitably be deal

ing when he becomes a member of the Texas Bar.

With such a substantial and significant segment of

society excluded, we can not conclude that the educa

tion offered petitioner is substantially equal to that

which he would receive if admitted to the University

of Texas Law School.

8

“ It may be argued that excluding petitioner from

that school is no different from excluding white

students from the new law school. This contention

overlooks realities. It is unlikely that a member of

a group so decisively in the majority, attending a

school with rich traditions and prestige which only

a history of consistently maintained excellence could

command, would claim that the opportunities afforded

him for legal education were unequal to those held

open to petitioner. That such a claim, if made,

would he dishonored by the State, is no answer.

‘ Equal protection of the laws is not achieved through

indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.’ ”

If we apply the same standards of measurement to this

case which were applied in the Sweatt case, we are faced

with the following uneontroverted facts:

The Two Law School Plants

The University Law School commenced in 1845 when a

professorship of law was established. It was not formal

ized into a law school until 1900 (R. 40, 41, 282). It is

situated at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and is part of the

University of North Carolina. The law school is housed

in a brick building, which was originally planned and

designed as a law school (R. 47) at an original cost of

approximately $120,000. Additions to the law school cost

ing approximately $400,000, were in process at the time

of trial and were planned and designed specifically to meet

the needs and specifications for law school teaching (R. 47).

The additions were promised completion by December, 1950

(R. 47). There are study halls for students and space

where they can use typewriters (R. 50). Each member of

the faculty has a private office and none have offices in the

classroom (R. 57).

The College Law School was opened in 1939 but had to

close because of lack of students. It reopened in 1940 and

has been in operation since that date (R. 97, 282). It is

9

situated in Durham, North Carolina, and is a part of the

North Carolina College for Negroes. The Law School is

housed in a frame building, originally built as an audi

torium of the College (R. 110). The College general library

is to be converted into a law school at an estimated cost

of $20,000 as soon as the new library is completed (R. 110).

There are no study halls for students and no separate space

for students to study with typewriters (R. 102). Students

must study and type in the library (R. 102). One of the

members of the faculty uses his classroom as an office

(R. 102).

Accreditation

The University Law School is a member of the Asso

ciation of American Law Schools and is approved by the

American Bar Association and North Carolina Board of

Examiners (R. 42, 283). The College Law School is ap

proved provisionally by the American Bar Association

and North Carolina Board of Examiners and has filed

application for admission to the Association of American

Law Schools (R. 101, 283).

Degrees and Courses

The University Law School is offering 38 courses of

instruction during the 1950-1951 school term (R. 65). It

awards an LL.B. degree and a J.D. degree (R. 61), and

holds summer sessions (R. 62).

The College Law School is offering 27 courses of in

struction during the 1950-1951 school term, and awards only

the LL.B. degree and holds no summer sessions (R. 104).

Student Body

The University Law School has a student body of ap

proximately 288 students. These students are a cross sec

10

tion of the state’s population representing racial groups

comprising approximately 74% of the state’s population

(R. 55, 286). From this group comes most of the judges,

lawyers, witnesses and jurors with whom a member of the

North Carolina bar must deal. It has a law review main

tained since 1923 (R. 46), a chapter of the Order of the

Coif (R. 52), and other student activities (R. 63).

The College Law School had an enrollment of 28 stu

dents. They are all Negroes and come from a racial group

representing 26% of the state’s population. It has no

law review, no chapter of the Order of the Coif (R. 104),

and there was no testimony of any other student activities.

The Faculty

The University Law School has a full-time staff of ten

teachers including the Dean, and in addition a full time

librarian and assistant librarian. Nine of the ten teachers

are full professors, and the tenth and latest addition to the

faculty is an assistant professor (R. 44). Faculty members

have done a considerable amount of research and writing

in their fields, and a summary of their publications may be

found at pages 268, 269, 270 in the record. Members of

their staff have had extensive teaching experience (R. 45),

and experience in government service (R. 42) and are

recognized authorities in their field. Members of the

faculty serve on the North Carolina Legislative Commis

sions (R. 51).

The College Law School has a full-time staff of five

teachers including the Dean and the librarian (R. 97).

There is no established professorial ranking although the

Dean is given a title of full Professor and the other full

time teachers that of Assistant Professor (R. 100). All

members of the faculty have had a limited amount of

teaching experience (R. 99), the greatest amount of ex

perience, except for the Dean who has been at the college

11

since 1941, is three years (R. 99). There is no evidence

of any legal research having been done by the faculty, and

none of them has written or published any legal treatises

(R. 101, 111). With exception of the Dean its faculty lias

no ascertainable reputation (R. 217). No members of the

faculty have ever served on the North Carolina Legislative

Commission (R. 100).

The Library

The University Law School has a law librarian and

assistant librarian, and between five to eight part-time

student assistants (R. 80). The library holds approxi

mately 64,000 volumes (R. 82), but only 47,000 were avail

able on the shelves at the time of the trial, pending com

pletion of additions to the law school building (R. 287).

The library has an upper and lower reading room, and

several detached reading rooms, all of which contain vari

ous reports (R. 85, 86).

The College Law Library has a full-time librarian and

two part-time student assistants. The College owns ap

proximately 30,000 volumes, but only 23,000 were on the

shelves (R. 267). It has only one reading room (R. 106).

Reputation and Alumni

Witnesses for appellants testified that the University

of North Carolina is considered one of the leading educa

tional institutions in the South (R. 146), and that the

University Law School has an excellent reputation (R.

217), and is considered one of the leading law schools in

the country (R. 146, 192). The alumni of the University

Law School occupy some of the most prominent positions

in the private practice of law and in the public life of the

state. Among its alumni are governors of the state, state

and federal judges, state and federal legislators (R. 270,

271). The majority of the practicing attorneys and legis

1 2

lators in the state received their training at the University

of North Carolina School of Law (E. 272-280).

The College Law School has no graduates of equal

prominence either in the private practice of law, or in the

public life of the state. Neither North Carolina College

for Negroes, nor the College Law School has any ascer

tainable reputation other than as state schools for Negroes

in North Carolina (E. 146, 217).

In comparing these above facts with those set forth by

the Court in the Sweatt case, it is difficult to perceive

how any conclusion can be reached other than that appel

lants must be admitted to the University of North Carolina

Law School for the same reasons that the Court ordered

petitioner’s admission to the University of Texas Law

School in the Sweatt case.

It is true that there are minor differences between the

two cases. In this case the state has maintained and oper

ated the College Law School for Negroes continuously since

1940, and in the Sweatt case the law school was established

in 1947. The Supreme Court, however, recognized the

Texas Law School for Negroes as a going concern, and that

the training offered was adequate to enable its graduates

to successfully pass the State Bar Examination, but the

issue before it for decision was whether that school could

be considered the equal to the University of Texas. It

found it could not be.

Thus, in this case neither the good intentions of the

state, the adequacy of legal training offered at the College

Law School, nor its ten years’ existence can be considered

relevant. The issue which must be met is whether the

College Law School is the equivalent of the University

Law School. The facts, we submit, compel the conclusion

that the University Law School in this case, as the Texas

University Law School in the Sweatt case, is far superior

to the separate institution which the state has established

13

for the legal training of Negroes. It seems clear that

when the Court places such emphasis on the fact that the

petitioner in the Sweatt case would have been required to

study at the Texas Law School for Negroes in isolation

from 85% of the population as evidence of inequality, that

here an indicia of inequality must be found in the fact that

appellants are required to take their training at a segre

gated law school in isolation from 74% of the population

of the State of North Carolina. When the Sweatt case is

considered along with the decision in McLaurm v. Board

of Regents, supra, where it was held to be a denial of the

equal protection of the laws to require a Negro graduate

student, admitted to the state university, to sit at a specially

designated seat or desk in the classroom and at a special

table in the cafeteria and library, the conclusion is ines

capable that in respect to graduate and professional train

ing offered by the state, the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment can only be met by according to Negroes the

same training accorded to all other persons and on the

same basis.

Conclusion

Any consideration as to the desirability of North Caro

lina’s policy of maintaining separate institutions for the

legal training of Negroes has been foreclosed by the United

States Supreme Court’s decision in the Sweatt case. It has

been determined by that Court that to require a person to

attend a racially segregated law school in “ isolation from

the individuals and institutions with which the law inter

acts” is to deny that person rights which are guaranteed

by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Appellees, therefore, in refusing appellants admis

sion to the University of North Carolina School of Law

because of race and color are guilty of an unconstitutional

deprivation of appellants’ rights.

u

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that the

judgment of the Court below should be reversed.

Conrad 0 . P earson,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall

Attorneys for Appellants.

Dated: February 15, 1951