Thompson v. Raiford Unopposed Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae in Opposition to Defendant's Alternative Motions to Dismiss and For Summary Judgment with Declarations

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thompson v. Raiford Unopposed Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae in Opposition to Defendant's Alternative Motions to Dismiss and For Summary Judgment with Declarations, 1992. 13b8b204-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2f4dd95b-ebdc-4efa-9fd1-a77499c69160/thompson-v-raiford-unopposed-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amici-curiae-in-opposition-to-defendants-alternative-motions-to-dismiss-and-for-summary-judgment-with-declarations. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

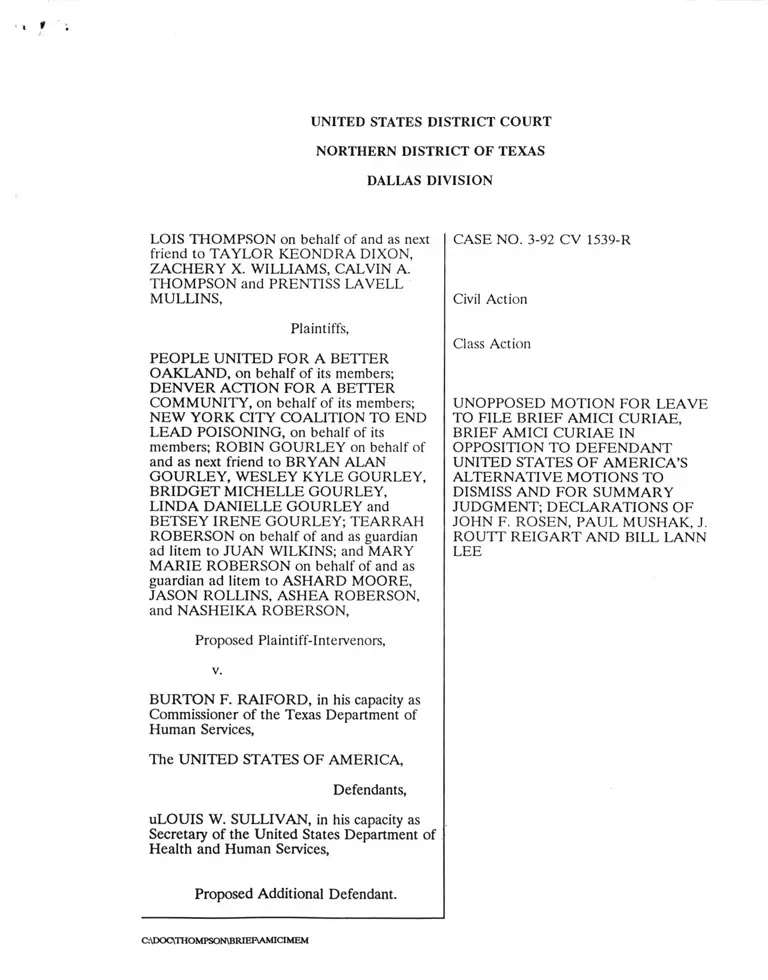

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and as next

friend to TAYLOR KEONDRA DIXON,

ZACHERY X. WILLIAMS, CALVIN A.

THOMPSON and PRENTISS LAVELL

MULLINS,

Plaintiffs,

PEOPLE UNITED FOR A BETTER

OAKLAND, on behalf of its members;

DENVER ACTION FOR A BETTER

COMMUNITY, on behalf of its members;

NEW YORK CITY COALITION TO END

LEAD POISONING, on behalf of its

members; ROBIN GOURLEY on behalf of

and as next friend to BRYAN ALAN

GOURLEY, WESLEY KYLE GOURLEY,

BRIDGET MICHELLE GOURLEY,

LINDA DANIELLE GOURLEY and

BETSEY IRENE GOURLEY; TEARRAH

ROBERSON on behalf of and as guardian

ad litem to JUAN WILKINS; and MARY

MARIE ROBERSON on behalf of and as

guardian ad litem to ASHARD MOORE,

JASON ROLLINS, ASHEA ROBERSON,

and NASHEIKA ROBERSON,

CASE NO. 3-92 CV 1539-R

Civil Action

Class Action

UNOPPOSED MOTION FOR LEAVE

TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE,

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN

OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA’S

ALTERNATIVE MOTIONS TO

DISMISS AND FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT; DECLARATIONS OF

JOHN F. ROSEN, PAUL MUSHAK, J.

ROUTT REIGART AND BILL LANN

LEE

Proposed Plaintiff-Intervenors,

v.

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his capacity as

Commissioner of the Texas Department of

Human Services,

The UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendants,

uLOUIS W. SULLIVAN, in his capacity as

Secretary of the United States Department of

Health and Human Services,

Proposed Additional Defendant.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\BRIEF\AMICIMEM

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amici ............................................................................................................................. 1

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1

Summary of Argument ................................................................................................................. 2

Statement ......................................................................................................................................... 3

A. The Extent of Lead Poisoning in Poor Children ................................................. 3

1. Prevelence............................................................................................................ 3

2. Exposure.............................................................................................................. 4

3. Symptoms ............................................................................................................ 6

B. The Appropriate Test for Poor Children .............................................................. 6

Argument ............................................................................................................................................ 8

A. The Plain Terms of the Statute Require A Blood Lead Test............................. 8

B. Legislative History Confirms that Congress Intended to Mandate A

Blood Lead Test to Screen For Lead Poisoning............................................... 10

C. The Agency Construction of the Statute Is Entitled to No Deference............. 11

D. The Remedial Purpose of the EPSDT Statute and the CDC Report Mandate

that Blood Lead Testing Be Required................................................................ 14

1. The Remedial Purpose of the EPSDT Statute Requires Blood Lead

Testing .................................................................................................... 13

2. The CDC Statement Requires Blood Lead Testing ..................... 13

Inappropriateness of Questioning and EP Testing for Screening . . 15

Indefinite Transiton Period..................................................................... 16

Conclusion......................................................................................................................................... 19

Affidavit of John F. R o se n ............................................................................................................ 21

Declaration of Paul M ushak........................................................................................................... 126

Declaration of J. Routt Reigart ....................................................................................................276

Declaration of Bill Lann Lee ................................................................................ 280

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson,

456 U.S. 63 (1 9 8 2 )........................................................................................................... 9, 11

Beltran v. Myers,

701 F.2d 91, (9th Cir.) ceret denied sub nom.,

Rank v. Beltran, 462 U.S. 1134 (1 9 8 3 ).............................................................................. 9

Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840 (1 9 7 6 )............................................................................................................ 11

Chevron, U.S.A., Inc., v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.,

467 U.S. 837 (1984).............................................................................................................. 12

Citizens Action League v. Kizer,

887 F.2d 1003 (9th Cir. 1989), cert denied,

494 U.S. 1056 (1 9 9 0 ) ............................................................................................................ 8

Consumer Product Safety Com’n v. GTE Sylvania, Inc.

447 U.S. 102 (1 9 8 0 ).............................................................................................................. 8

EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

113 L.Ed.2d 274 (1991) .................................................................................................... 13

Fleetwood Enterprises, Inc., v. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

818 F.2d 1188 (5th Cir. 1987).......................................................................................... 12

Fort Stewart Schools v. Federal Labor Relations Authority,

495 U.S. 641 (1 9 9 0 )............................................................................................................ 12

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert,

429 U.S. 125 (1 9 7 6 )............................................................................................................ 13

K Mart Corp. v. Cartier, Inc.,

486 U.S. 281 (1 9 8 8 )............................................................................................................ 12

United States v. Chen,

913 F.2d 183 (5th Cir. 1990) ............................................................................................. 8

United States v. Moody,

923 F.2d 341 (5th Cir.) cert, denied, 112 S.Ct. 80 (1991)............................................... 8

West Virginai University Hospitals Inc., v. Casey,

111 S.Ct. 1138, 113 L.Ed.2d 68, (1 9 9 1 ) ....................................................................... 8, 11

Statutes and Regulations:

42 U.S.C. §1396d(r)(i)(B)(iv) .............................................................................................. passim

42 U.S.C. §1396(a)(a)(43)..................................... .......................................................................... 9

42 U.S.C. §1396d(a)(4)(B) ............................................................................................................. 9

42 U.S.C. §1396d(r)......................................................................................................................9, 11

16 C.F.R. pt 1303 ...................................................................................................................................

42 U.S.C. §1396d(a).......................... ............................................................................................ 10

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 11

Pages:

Other Materials'.

Centers for Disease Control,

Statement on Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children (1991) ............ passim

Conference Report on H.R. 101-386,

101 Cong., 1st Sess. (1989)............................................................................................... 12

HHS, The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States:

A Report to Congress (1 9 8 8 )................................................................................... passim

HHS, Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning (1991) . . . . passim

H. R. Rep. No. 213, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1 9 6 5 )..................................................................... 9

McElvain, M.D., Orbach, H.G., Binder, S., Blanksma, L.A., Maes, E.F. and Krieg, R.M.

"Evaluation of the Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin Test as a Screen

for Elevated Blood Lead Levels," 1 1 9 / Pediatrics 548 (1991)........................... 10, 11

Report of the House Budget Comm, on H.R. 3299

101 Cong. 1st Sess., (Sept. 20, 1989) reprinted in

Medicare and Medicaid Guide (CCH)

Extra Edition No. 596 (October 5, 1989) ........................................................ 11, 12, 14

State Medicaid M anual..............................................................................................................14, 18

Welfare of Children,

H.R.Doc. No.54, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.7 (1967) .......................................................... 14

C:\DOC\THOMFSON\PLEADINGVAMICIMEM 111

UNOPPOSED MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Proposed plaintiff-intervenors People United for a Better Oakland, et al. seek leave to

submit the attached brief amici curiae in response to federal defendant’s alternative motions

to dismiss and for summary judgment. Leave should be granted for the following reasons:

1. Proposed plaintiff-intervenors are parents and guardians of Medicaid eligible

children from North Carolina, and organizations that advocate adequate screening for lead

poisoning whose members include parents and guardians of Medicaid eligible children from

California, Colorado and New York.

2. Proposed plaintiff-intervenors have submitted a motion to intervene in the instant

proposed nationwide class action to challenge federal defendant’s failure to comply with the

requirements of the Medicaid statute for mandatory blood lead testing of poor children.

3. Proposed plaintiff-intervenors submit this brief amici curaie because federal

defendants’ alternative motions may dispose of the issues on which they wish to be heard as

plaintiff-intervenors while their motion to intervene is still pending.

4. Proposed plaintiff-intervenors and their counsel — the NAACP Legal Defense Fund,

National Health Law Program and New York and North Carolina legal services offices — have

experience which the Court may find of assistance. They also have obtained declarations from

leading medical and public health experts on factual issues presented by federal defendant’s

alternative motions.

5. Both plaintiffs and federal defendant consent to the filing of the brief.

6. Should the motion to intervene be granted, proposed plaintiff-intervenors adopt this

brief as their response to federal defendant’s alternative motions.

////

////

////

////

////

////

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 1

Wherefore, proposed plaintiff-intervenors request that leave be granted to file the

enclosed brief amici curiae.

Dated: November 23, 1992

Respectfully submitted,

Edward B. Cloutman, III

Law Office of Edward B. Cloutman, III

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, TX 75226

(214) 939-9222

Julius L. Chambers

Alice Brown

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Bill Lann Lee

Kirsten D. Levingston

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

315 West Ninth Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

Jane Perkins

National Health Law Program

313 Ironwoods Drive

Chapel Hill, NC 25716

(202) 887-5310

Carlene NcNulty

North State Legal Services

114 West Corbin Street

Hillsborough, N.C. 27278

(919) 732-8137

Lucy Billings

Marie-Elena Ruffo

Bronx Legal Services

579 Courtlandt Avenue

(212) 993-6250

Edward B. Cloutman, III

Texas Bar No. 04411000

By_________________________

Bill Lann Lee

Attorneys for Amici

People United for a Better Oakland, et al.,

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 2

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Interest of Amici

Amici are advocacy organizations whose members include parents and guardians of

Medicaid eligible children from California, Colorado and New York as well as parents and

guardians of Medicaid eligible children from North Carolina. They have submitted a pending

motion to intervene as plaintiff-intervenors.

Amici parents and guardians, and parent and guardian members of amici organizations

seek either to obtain effective screening for lead poisoning or to safeguard effective screening

that is threatened by the actions of federal defendant. Amici are representatives of the

proposed nationwide plaintiff class of poor children, and their parents and guardians.

Introduction

The key substantive issue before the Court is the meaning of the Medicaid Act

provision that Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (hereinafter "EPSDT')

program "screening services . . . shall at a minimum include laboratory tests including lead

blood level assessment appropriate for age and risk factors" for lead poisoning. 42 U.S.C.

§1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv). Conceding that a blood lead level test, which directly assesses lead blood

levels, is "the test of choice" to screen for lead poisoning, USA motion 14, federal defendant

nevertheless contends that it may permit the use of an erythrocyte protoporphyrin (hereinafter

"EP") test, in combination with a verbal questionnaire for screening. This contention is

advanced notwithstanding the finding of federal defendant’s expert, as well as all others who

have studied the problem, that only a blood lead test can effectively detect lead poisoning and

that the EP test fails to identify most children who have been poisoned by lead.

As we show below, the statutory language, legislative history and remedial purpose of

the statute require that only a blood lead level test be used to screen for lead poisoning.

Summary judgment for federal defendant should be denied, and the Court should entertain

a summary judgment motion on behalf of plaintiffs and proposed plaintiff-intervenors.1

1Amici incorporate by reference plaintiffs’ arguments about standing. With respect to

the propriety of a TRO or preliminary injunction, the Court may wish to defer any such

ruling unless a summaiy judgment proves inadequate to protect the interests of plaintiffs

and plaintiffs-intervenors.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 1

Summary of Argument

A. The terms of a statute are controlling unless they are unclear or ambiguous. In the

case of §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv), the Medicaid Act clearly, unambiguously specifies that a

laboratory test to assess "lead blood level" or Pb-B is required under the EPSDT program.

All the parties agree that the only laboratory test that directly assesses Pb-B levels is a blood

lead test. The EP test, not a lead blood level test, cannot, as claimed by the government,

provide an accurate "indirect" measure of lead blood level. It is in fact completely unreliable,

identifying only one out of seven or eight children with toxic lead blood levels.

B. Legislative history is sparse but no less supportive of plaintiffs’ position. Prior to

1989, the Medicaid Act did not specifically require lead blood level assessments as a

mandatory part of the EPSDT screen. During the 1970’s the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services ("HHS") had instructed state Medicaid agencies that the EP test was to be

used by EPSDT providers who decided to screen for lead poisoning. In 1988, however, the

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry presented a pivotal report to Congress, The

Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress

(hereinafter "Report to Congress"), Exhibit B to Declaration of Paul Mushak (hereinafter

"Mushak decl."), which quantified extensive levels of lead poisoning among poor children and

also concluded: "Reliance on EP level for initial screening can result in a significant incidence

of false negatives or failures to detect toxic Pb-B levels." Report to Congress II-9. The Report

to Congress formally recommended to Congress that the EP test not be used to screen for lead

poisoning. Just a year later, Congress passed amendments to the Medicaid Act which codified

and changed the EPSDT program, specifically to add a laboratory testing requirement for

"lead blood level assessment appropriate for age and risk factors." 42 U.S.C.

§1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv).

C. The federal defendant’s construction of the statute is entitled to no deference in

light of the unambiguous statutory language and legislative background. Moreover, this

construction contradicts its other recent pronouncements on the subject, such as the 1991

Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning (hereinafter "Strategic Plan"),

Exhibit B to Declaration of John F. Rosen (hereinafter "Rosen decl."), which declares that

C:\DOCVTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 2

"blood lead measurements must be used for childhood lead screening instead of EP

measurements." Strategic Plan 23 (emphasis added). Finally, the federal defendant’s position

is simply incorrect as a factual matter. The federal defendant admits that neither a verbal risk

assessment nor the EP test are able adequately to screen for lead poisoning. Yet, it asks the

Court to accept that these two inadequate tests, combined together, somehow produce the

valid "lead blood level assessment" that is required by Congress. The experts reject this

approach -- as has the federal defendant itself by admitting that this scheme is to be used as

an interim measure during an undefined transition to universal use of the congressionally-

mandated lead blood level assessment for poor children.

D. The purpose of §1396d(r)(iv) is remedial and it is to be construed liberally to

advance the overall goal of the EPSDT program to improve the nation’s health by early

detection and prevention of childhood illnesses. If, as federal defendant concedes, the

majority of Medicaid eligible children are at high risk for lead poisoning, §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv)

should be read to require blood lead testing to assess Pb-B levels consistent with the Statement

on Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children issued in 1991 by the Centers for Disease

Control (hereinafter "CDC Statement"), Exhibit 1 to Declaration of Sue Binder (hereinafter

"Binder decl."). EP testing and verbal questioning (alone or in combination) are ineffective

substitutes. Purported limited laboratory capacity is a mere pretext. See Declarations of John

F. Rosen (Chairperson of the CDC’s Advisory Committee Childhood Lead Poisoning

Prevention Advisory Committee); Paul Mushak (author of the 1988 Report to Congress)-, and

J. Routt Reigart (Chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on

Environmental Health) (hereinafter "Reigart decl.")

Statement

A. The Extent of Lead Poisoning in Poor Children.

1. Prevalence.

Lead poisoning, according to HHS, is "the most common and societally devastating

environmental disease of young children." Strategic Plan xiv. Using the outdated definition

of lead poisoning in 1988, the Report to Congress found that in 1984 2.4 million white and

African-American pre-school children — 17% of all such children - in metropolitan areas had

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 3

projected toxic lead blood levels, and that 400,000 fetuses per year are at risk of being bom

lead poisoned. See Mushak deck at 11 16; Rosen deck at 11 13.

Medicaid eligible children by definition are at high risk for lead poisoning. Their low

income status is an indicator that they live in older, deteriorated or recently rehabilitated

housing that has exposed them to lead paint. The 1988 Report to Congress, showed the

incidence of lead poisoning is 2-3 times higher among other Medicaid eligible children than

among other children of the same age. See Rosen deck at 11 30; Reigart deck at HIT 11-12;

Hiscock deck at H 20.

Applying the CDC’s present 10 jxg/dL toxicity level to 1984 national data shows the

following prevalence projections in America’s poor communities: In smaller cities with

populations less than one million, 79% of all children with family incomes below $6000 —

91.6% of all African-American children — were projected to have lead levels exceeding the

new CDC action level of 10 /xg/dL. In larger cities, 88% of all children with family incomes

below $6000 — 96.5% of all African-American children -- were projected to be affected. For

children living in smaller cities whose families earn between $6000 and $14,999, approximately

67% had blood lead levels associated with early toxicity; 83% of African-American children

in this category were affected. In larger cities, 78.5% of all children whose families earn

between $6000 - $14,999 -- 92% of all African-American children — have lead levels at or

exceeding the 10 /xg/dL level. Prevalence of blood lead levels above 5 /xg/dL, a level only one-

half that for early toxicity, in poor children is virtually 100 percent. While corresponding

prevalence for the current year, 1992, will be lower overall, it is likely that inner-city, poor

children will show the least declines. See Mushak deck at HU 18 - 19.

According to the CDC Statement, "[although all children are at risk for lead toxicity,

poor and minority children are disproportionately affected. Lead exposure is at once a by

product of poverty and a contributor to the cycle that perpetuates and deepens the state of

being poor." CDC Statement 12.

2. Exposure.

Ingesting lead particles can cause severe damage to the brain and central nervous

system. Children from birth through age six years are by definition at risk from lead

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 4

poisoning. Their normal hand-to-mouth activity causes more frequent ingestion of lead

particles. More significantly, the developmental stages of children’s brains and nervous systems

are particularly vulnerable. Environmental factors may put older children at risk. Ingestion

of lead particles by pregnant women also causes damage to the developing fetus. See Rosen

decl. at U 12 - 13; Mushak deck at H 10 - IT, Report to Congress 1, 10, III-12, IV-7; CDC

Statement 7 - 12.

As detailed extensively in the 1988 Report to Congress, lead is pervasive in the

environment. Children are exposed to lead from six environmental sources, three of which still

persist as major sources or pathways: paint, dust/soil, and water. Lead in gasoline, foods, and

stationaiy sources is declining in importance. Although residential use of lead-based paint is

now banned, lead paint in existing housing remains the most widespread and dangerous high-

dose source of lead exposure for young children. Lead paint remains in over 57,000 homes

nationwide; 74% of all homes constructed before 1980 contain lead paint. Lead paint

continues to be used on the exteriors of painted steel structures, such as bridges and

expressways. Children living near such sites as expressways have been shown to have elevated

blood lead levels. See Mushak deck at H 12; Rosen deck at 11 14; 16 C.F.R. pt 1303; CDC

Statement 18.

Lead deposited in soil or as dust does not biodegrade or decay since lead is a chemical

element. Children playing around contaminated dust and soil will remain exposed indefinitely.

The water distribution system can also pose a lead risk. Contamination of drinking water

occurs in or near residences and schools when lead leaches into water from lead connectors,

service pipes, lead-soldered joints, or lead-lined watercoolers. See Mushak deck at 111113 -14.

Lead entering the body from different sources and through different pathways presents

a combined toxicological threat. Thus, multiple, low-level inputs of lead can result in

significant aggregate exposure. See Mushak deck at 11 15. See Report to Congress 6 - 8 ,

chapters VI & VIII.

C:\DOCVTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 5

3. Symptoms.

Very severe lead poisoning (associated with lead levels at or above 80 p,g/dL) can result

in coma, convulsions, profound mental retardation, and even death. At lower concentrations,

lead mainly interferes with normal development of IQ and other neuro-behavioral measures

in children; with the body’s heme-forming system, which is critical to the production of heme

and blood; and with the vitamin D regulatory system, which involves the kidneys and plays an

important role in calcium metabolism. See Mushak decl. at H 10; Rosen deck at H 16.

Lead poisoning is often asymptomatic in its early stages, and its symptoms are the same

as many other childhood diseases and impairments. Lead toxicity produces altered behavior

such as attention disorders, learning disability, and cognitive disturbances. Symptoms and signs

of severe toxicity are fatigue, pallor, constipation, vomiting, and changes in consciousness

(coma) due to early encephalopathy, which may lead to death. Mental retardation is a

frequent result. See Rosen deck at U 17; CDC Statement 7-15.

According to currently published data, all cases of lead poisoning cause some persisting,

irreversible brain damage, reduced IQ, delayed cognitive development, and other physical and

mental impairments. Such effects occur at blood lead levels above and even below 10 /xg/dL.

In fact, there is no apparent threshold. Lead causes adverse effects even below 2 /zg/dL. At

least three longitudinal studies of young children in Boston, Cincinnati and Australia show that

prenatal and early childhood exposure to lead has adverse effects at low exposure levels on

a child’s IQ and other neurobehavioral measures, and that these effects persist into the school-

age years. See Rosen deck at U 16; Mushak deck at U 11.

B. The Appropriate Test for Poor Children.

The only way to determine that lead poisoning is the cause of such symptoms and to

bring them to a halt is to test for the level of lead in blood or Pb-B. According to all recent

scientific studies, only direct measurement of blood lead concentration has the clinical and

diagnostic capability to determine whether a child has lead poisoning. 1988 Report to Congress-,

1991 Strategic Plan-, 1991 CDC Statement 41. See Rosen deck at 11 18. The parties agree that

only a blood lead test directly measures Pb-B. See USA motion 12.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADINO\AMICIMEM 6

Verbal questioning about a child’s possible exposure to lead does not provide a lead

blood level assessment, nor can it elicit complete, definitive, or accurate data to indicate a

child’s blood lead level. Many patients, especially Medicaid recipients, simply may not know

all the answers to the verbal assessment questions. See Rosen decl. at 11 19, Mushak decl. at

11 19; Reigart decl. at H 9. According to the CDC, "[t]he questions are not a substitute for a

blood lead test." CDC Statement 42 (original emphasis).

A blood test that does not test for the level of lead in blood does not elicit complete,

definitive, or accurate enough data either. The EP test is such a test. The EP test does not

test for the level of lead in blood at all. In fact, it is only an indirect reflection of iron or lead

status. For lead status, this test is an insensitive index of any blood lead values below 40

/xg/dL. At blood lead values between 10 and 30 /zg/dL, EP measurements will totally fail as

a screening method to identity the overwhelming majority (over 95%) of children whose blood

lead levels fall in this danger zone. See Rosen decl. at U 20; Mushak decl. at 11 23 - 24; Reigart

decl. at 11 10.

The EP test - a low cost, high volume procedure - is used to predict lead absorption.

In children exposed to elevated concentrations of lead, the lead interferes with the body’s

ability to make heme, which is used to carry oxygen when in the form of hemoglobin. Lead

retards formation of heme from the protoporphyrin molecule and protoporphyrin builds up

in the blood. The EP test measures this build up of protoporphyrin. It does not give directly

discreet blood lead concentrations; rather, protoporphyrin levels are a surrogate indicator for

the likelihood of elevated blood lead levels.

At the clinic operated by the Lead Poisoning Prevention Program at the Montefiore

Medical Center, Bronx, New York, where Dr. Rosen has performed blood lead tests and EP

tests together, there have been a significant number of cases where the EP test result was

normal, and the blood lead level was above 25 /zg/dL. Such occurrences were demonstrated

nationally by the Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II),

in 1976-90. See Rosen declaration at 1121; Report to Congress V-31. Significantly, the data was

analyzed and presented to Congress in the 1988 Report to Congress. O f 118 children with Pb-B

levels above 30 /zg/dL (the CDC criterion level at the time of the NHANES II study), 47% had

C:\DOCVTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 7

EP levels at or below 30 /xg/dL, and 58% had EP levels less than an EP cutoff value of 35

/xg/dL. Report to Congress II-9. Of course, the CDC has revised the criterion level to 10

jag/dL, an action which introduces even more false negatives into the EP test results. See

Mushak decl at 11 24.

In sum, the EP test serves only to predict the presence of lead in the blood. It cannot,

however, be used as a predictive surrogate for lead blood levels below 40 pgJtiL. The test does

not act as a preventive test which allows the health care provider to detect lead poisoning at

its early, more manageable stages. Rather, the EP test can only accurately predict that

unacceptably high lead exposure and greater risk of more severe poisoning have already

occurred. See Mushak decl. at 11 25.

For a pediatrician pursuing a diagnosis, the only responsible course of action is to carry

out a test that provides safe and definitive results for all children, according to current

standards of pediatric practice. A blood lead test provides definitive information concerning

the extent to which a child has been recently exposed to lead. An EP test provides, only for

one child out of seven or eight, at best, marginal information indicating that a child may be

lead poisoned. For a pediatrician seeking a conclusive diagnosis, to perform such an

unreliable test for lead poisoning is irresponsible pediatric practice. See Rosen decl. at H 22;

see also Reigart decl. at 1111 10, 11 & 13; See Mushak decl. at 1111 23, 25 - 26.

Argument

A. The Plain Terms of the Statute Require A Blood Lead Test.

In construing a statute, we look first to the plain meaning of the statutory language.

Consumer Product Safety Com’n v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 447 U.S. 102, 108 (1980). Terms used

by a statute are to be given their ordinary, commonly understood meaning. United States v.

Moody, 923 F.2d 341, 347 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 112 S.Ct. 80 (1991); United States v. Chen,

913 F.2d 183,189 (5th Cir. 1990); Citizens Action League v. Kizer, 887 F.2d 1003, 1006 (9th Cir.

1989), cert denied, 494 U.S. 1056 (1990). Where the statutory language is clear and

unambiguous, consideration of legislative history and other extrinsic guidance is unnecessary.

See, e.g., West Virginia Univ. Hospitals, Inc., v. Casey, 111 S.Ct. 1138,113 L.Ed.2d 68, 83 (1991)

("[w]here, as here, the statute’s language is plain, ‘the sole function of the court is to enforce

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 8

it according to its terms.’") (citation omitted); American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S.

63, 68 (1982).

The instant case concerns the EPSDT provisions of the Medicaid Act, which was passed

by Congress in 1965 as a cooperative federal-state medical assistance program for the poor.

See Beltran v. Meyers, 701 F.2d 91, 92 (9th Cir.) cert denied sub nom., Rank v. Beltran, 462 U.S.

1134 (1983). The federal law requires states participating in the Medicaid program to cover

certain "essential" services for recipients, H.R. Rep. No. 213, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 9 - 10, 70

(1965), including a disease and developmental disability prevention program for children under

age 21 known as the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment ("EPSDT')

program. 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(43), d(a)(4)(B), and d(r).

The EPSDT program requires, inter alia, mandatory medical screening of poor children

to diagnose their "physical or mental defects" as early as possible. 42 U.S.C. 1396d(a)(4)(B).

In 1989, Congress amended the EPSDT statute to specify that EPSDT screening services were

to include, at a minimum, "laboratory tests (including lead blood level assessment appropriate

for age and risk factors)." 42 U.S.C. 1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv). It is this latter phrase which the

federal defendant would have the court ignore.

The term "lead blood level," a scientific term, refers to the amount of lead in blood.

The federal defendant concedes that only a blood lead test "directly" measures lead blood

levels. USA Motion at 12, Hiscock deck at 11 9, Binder deck at 11 14.

Notwithstanding the plain language, federal defendant argues that the statutory

language does not require a blood lead test on two grounds. It first contends that Congress

did not intend to give such a "narrow, technical meaning" to the statutory term "lead blood

level." USA motion 29. Plaintiff-intervenors disagree. Had Congress not meant to bind the

agency to coverage of the lead blood test, it needed to mandate no requirement beyond

"laboratoiy testing," thus leaving federal and state authorities free to decide which type of tests

to cover. Congress, of course, specifically mandated a lead blood level assessment.

That Congress specifically mentioned lead blood laboratory testing in the Medicaid Act

is compelling in its own right. For the most part, Congress has chosen simply to list broad

categories of services (e.g., hospital services, physician services) rather than enumerate specific

C:\DOOTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 9

procedures by name. Compare, 42 U.S.C. 1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv) with, 42 U.S.C. 1396d(a). When

it included a statutorily-required laboratory test in an otherwise generally drawn Medicaid

statute, Congress surely chose its terms carefully and deliberately.

Federal defendant also argues that the EP test is an "indirect" assessment of lead blood

level. USA motion 12. Again, plaintiff-intervenors disagree. Notably federal defendant,

however, fails to inform the Court that shortly before drafting §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv), the House

Committee on Energy and Commerce was informed by HHS in its 1988 Report to Congress

that "reliance on EP level for initial screening can result in a significant incidence of false

negatives and failure to detect toxic Pb-B levels", and received the recommendation that the

EP test should be replaced by the blood lead test. Report to Congress 11-9.

With the lowering by the CDC of the toxicity level to 10 /xg/dL, the EP test is even

more unreliable.

Since erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) is not sensitive enough to identity more

than a small percentage of children with blood lead levels between 10 and 25

/xg/dL and misses many children with blood lead levels > 25 /xg/dL . . .

measurement of blood lead levels should replace the EP test as the primary

screening method.

CDC Statement 41; see also 2 ("Because the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level is not sensitive

enough to identity children with elevated blood lead levels below 25 jixg/dL, the screening test

of choice is now blood lead measurement.") Indeed, federal defendant’s expert, Dr. Binder,

is not only an author of the Report to Congress, with its admission that the significant number

of false negatives invalidates the EP test for screening, but an author as well of the very study

that the CDC cited in support of its assertion that the EP test is too insensitive to screen for

lead blood levels between 10 and 25 jxg/dL. See CDC Statement 41, 49, citing McElvaine,

M.D., Orbach, H.G., Binder, S., Blanksma, L.A., Maes, E.F. and Krieg, R.M., "Evaluation of

the Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin Test as a Screen for Elevated Blood Lead Levels," 119 J.

Pediatrics 548 (1991) (hereinafter "McElvaine, Orbach, Binder"), Exhibit A to Declaration of

Bill Lann Lee (hereinafter "Lee decl."). That study concluded that: "The sensitivity of the EP

test is . . . good for identifying children with vefy high Pb-B levels, those who most urgently

need follow-up. For identification of the children with Pb-B levels of 10 to 25 /xg/dL, another

screening method, probably Pb-B measurement, will be needed." McElvaine, Orbach, Binder

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 10

at 550. In fact, the EP test overall will only identity one out of seven or eight children with

lead poisoning at the levels the CDC now considers toxic. Rosen decl. at U 22.2

Neither the oral questions nor the EP test, alone or in combination, is a substitute for

the blood lead test. Had Congress intended to permit the use of the EP test, it could easily

have done so by substituting "erythrocyte protoporphyrin level" for the statutory phrase "blood

lead level" in § 1396d(r) or adopting HHS’ contemporaneous Medicaid guidance which

expressly identified the (EP) test as "the primary screening test." See Hiscock decl. at H 9.

Congress, however, did neither. Instead, it opted for a laboratory test to assess lead blood

level. See, e.g., Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 848 (1976) ("‘The plain, obvious and

rational meaning of a statute is always to be preferred to any curious, narrow, hidden sense

that nothing but the exigency of a hard case and the ingenuity and study of an acute and

powerful intellect would discover.’").

B. Legislative History Confirms that Congress Intended to Mandate A

Blood Lead Test to Screen For Lead Poisoning.

Legislative history analysis is unnecessary where, as here, the terms of the statute are

clear and unambiguous. Casey, 113 L.Ed.2d at 83; Patterson, 456 U.S. at 68. The available

legislative history, however, merely confirms the statute’s plain meaning.

Section 1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv) was added to the EPSDT statute by the Energy and

Commerce and Ways and Means Committees. Report of the House Budget Comm, on H.R

3299 101 Cong. 1st Sess., (Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in Medicare and Medicaid Guide (CCH),

Extra Edition No. 596 (Oct. 5, 1989) (Explanation of the Energy and Commerce of Ways and

Means Committees Affecting Medicare-Medicaid Programs) (hereinafter "House Report"),

Exhibit B to Lee decl. Noting that "[t]he EPSDT benefit is not currently defined in statute"

the House Report explained that the Committee bill amended the statute to specify that

"screening services, at a minimum, include . . . laboratory tests (including lead blood level

2Dr. Binder’s study found that, at 10 /xg/dL, the EP test identified more children with

elevated lead blood level, 26%, but failed to identify fully 74% of the poisoned children.

McElvaine at 549 (table II). The study noted, however, that the population studied may

have exhibited iron deficiency, which is also detected by the EP test, resulting in possibly

skewed results. Id. at 549 - 50.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 11

assessment appropriate for age and risk factors)." House Report at 399.

The obvious reason for the amendment was the July 1988 Report to Congress in which

HHS specifically recommended to the House Energy and Commerce Committee that the EP

test, which HHS permitted State Medicaid authorities to use for screening under the EPSDT

program, should be abandoned as a screening test for lead poisoning because it failed to detect

toxic lead blood levels. See Report to Congress II-9.

The House Committee bill was accepted unchanged by the Conference Committee, and

the Conference Report adds little to the legislative history. It briefly explained that the package

of EPSDT amendments "[cjodifies the current regulations on minimum components of EPSDT

screening . . . , with minor changes. Provides that screenings must include blood testing when

appropriate, as well as health education." Conference Report on HR 101-386, 101 Cong. 1st

Sess. 53 (1989). The report’s characterization of the "lead blood level assessment" provision

as a minor change is understandable because one laboratory test was merely being substituted

for another. While the Conference Report refers generically to "blood testing," the reference

appears to be a short-hand contraction used in the course of contrasting testing with the public

education component of screening rather than a studied gloss on the meaning of the statutory

term or a covert attempt to render superfluous the statutory terms "lead level."

C. The Agency Construction of the Statute Is Entitled to No Deference.

An agency construction of a statute that conflicts with the plain language and legislative

history of a statute is entitled to no deference. Fort Stewart Schools v. Federal Labor Relations

Authority, 495 U.S. 641, 645 (1990).

If, upon examination of "the particular statutory language at issue, as

well as the language and design of the statute as a whole," KMart Corp. v.

Cartier, Inc., 486 U.S. 281, 291 (1988), it is clear that the [agency] interpretation

is incorrect, then we need look no further, "for the court, as well as the agency,

must give effect to the unambiguously stated intent of Congress." Chevron

[U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837,] 842-43

[(1984).] If, on the other hand, "the statute is silent or ambiguous" on the point

at issue, we must decide "whether the agency’s answer is based on a permissible

construction of the statute." Ibid.

See also, Fleetwood Enterprises v. HUD, 818 F.2d 1188, 1193 (5th Cir. 1987).

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 12

In the instant case, no deference is due to the agency’s interpretation of the statute

because Congress spoke clearly and unambiguously about the meaning of §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv).

See supra. Moreover, the present position of HHS that the terms "lead blood level assessment"

permit use of the EP test conflicts with its prior statements. See EEOC v. Arabian American

Oil Co., 113 L.Ed.2d 274, 287-88 (1991); General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125, 141

(1976) (level of deference depends upon consistency with earlier pronouncements as well as

thoroughness of consideration and validity of reasoning). The 1988 Report to Congress stated

that the EP test should be abandoned because it produced many false negatives and failed to

detect toxic lead blood levels. The Strategic Plan declared that when the lead blood toxicity

level was lowered, as it was later in 1991, "blood lead measurements must be used for

childhood lead screening instead of EP measurements." Strategic Plan 23. In addition, the

CDC Statement termed the blood lead test the "screening test of choice" for the detection of

lead poisoning. CDC Statement 2.

Deference, in any event, would be anomalous because the statute was designed to

correct the very practice, use of the EP test, that HHS’ erroneous construction would

reimpose.

Federal defendant also argues at some length that HHS has a longstanding

commitment toward identifying and paying for the cost of treating lead poisoned Medicaid

eligible children, USA motion 9. The record of HHS speaks for itself. Congress enacted

§1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv) to change an HHS practice because the agency resisted acting upon the

recommendation of its own 1988 Report to Congress that the EP test should not be used. What

HHS seeks in this case is to continue using a test that even its own expert has found produces

so many false negatives that it fails to identify most children with toxic Pb-B levels.

While it is true that HHS historically has revised its EPSDT agency guidance following

CDC changes, USA motion at 10-11, the agency has by no means hastened to do so. HHS

waited three years before lowering the lead toxicity level for poor, at-risk children in response

to the 1985 CDC Statement. Id. And then, HHS lowered the toxicity level for Medicaid

eligible, at-risk children to 30 /xg/dL although the CDC had lowered it significantly for all

children to 25 /xg/dL.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 13

The failure of HHS to comply with §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv), unfortunately, is not

unprecedented. As the director of HHS Medicaid Bureau admitted in responding to the

protests of plaintiff-intervenors’ counsel; "in the past neither Medicaid’s EPSDT program nor

any other program have been successful in screening for lead poisoning a sufficient proportion

of children." Letter of Christine Nye to Julius L. Chambers, dated August 10, 1992,

Attachment B to the proposed Complaint in Intervention.

D. The Remedial Purpose of the EPSDT Statute and the CDC Report Mandate that Blood

Lead Testing Be Required.

1. The Remedial Purpose of the EPSDT Statute Requires Blood Lead Testing.

Congress enacted the underlying EPSDT statute with the remedial intent of "discovering], as

early as possible, the ills that handicap our children." President Lyndon B. Johnson, Welfare

of Children, H.R.Doc. No.54, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.7 (1967). In 1989, the House Committee

explained that §1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv) was necessitated by the fact that "[t]he EPSDT benefit is,

in effect, the nation’s largest preventive health program for children" and would become "even

more important to the health status of children in this county" "as Medicaid coverage of poor

children expands." House Report 398. The remedial nature of the EPSDT program is highly

significant in the context of lead poisoning. "Lead poisoning, the most common and societally

devastating environmental disease of young children, is entirely preventable." Strategic Plan

xiv.

Using a blood lead test would plainly advance the remedial objective of the EPSDT

program by improving preventive health care for the nation’s poor children. It will also

advance the specific remedial purpose of §1396d(r)(iv) to reform HHS’s practice of using an

ineffective test to screen those most at risk for lead poisoning. The EP test will do neither.

2. The CDC Statement Supports Immediate Blood Lead Testing of Medicaid Eligible

Children.

Federal defendant also erroneously argues that the testing scheme in the September

1992 State Medicaid Manual fully complies with the 1991 CDC Statement. On the one hand,

reliance upon the 1991 CDC Statement is misplaced: It is Congress’ 1989 mandate to the

Medicaid agency in 42 U.S.C. 1396d(r)(l)(B)(iv) that is at issue in this case, not a CDC

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 14

Statement which was adopted two years later. On the other hand, the CDC Statement is a

ringing endorsement of Congress’ 1989 action and is binding as the authoritative expression

of the testing protocol deemed "appropriate for age and risk." Thus, the CDC Statement’s

declaration that all children between the ages of 6 and 72 months should be screened at least

twice using a blood lead test at age 6 - 12 months and 18 - 24 months, CDC Statement at 43,

is dispositive as to the "appropriate" testing schedule for very young children under the statute.

The CDC Statement is also binding because it embodies current medical standards of

pediatric practice. Dr. John Rosen, the Chairperson of the CDC’s Childhood Lead Poisoning

Prevention Advisory Committee, which produced the CDC Statement, states in the attached

declaration that "[t]he Statement was prepared with primary medical care providers foremost

in mind, so they could glean the current, essential standards of pediatric practice in a readily

digestible form." Rosen decl. at 11 24.

For a pediatrician pursuing a diagnosis, the only responsible course of

action is to carry out a test that provides safe and definitive results for all

children, according to current standards of pediatric practice. A blood lead test

provides definitive information concerning to what extent a child has been

recently exposed to lead. An EP test provides, at best, marginal information

only for the one child out of seven or eight indicating that a child may be lead

poisoned. For a pediatrician pursuing a conclusive diagnosis, to perform such

an unreliable test for lead poisoning is irresponsible pediatric practice.

Id. at H 23; see also U 36. Dr. Rosen’s co-chair, Dr. J. Routt Reigart, who is also Chairman

of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Environmental Health, concurs.

Reigart decl. at 11 9 ("Although the American Academy of Pediatrics’ revised report is not yet

completed, one recommendation that will certainly come from the Committee is that there is

a need for more testing. Lead poisoning cannot be detected absent a blood test; a series of

questions cannot verify blood lead levels.").

The CDC Statement testing requirements also embody current public health standards.

See Mushak decl. at 1111 20 - 31.

Inappropriateness o f Questioning and EP Testing for Screening. Federal defendant

erroneously contends that the scheme of verbal assessment questioning to establish "low" and

"high" risk and EP testing of "low" risk children complies with the CDC Statement. According

to Dr. Rosen,

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICI MEM 15

[A]s Chairperson of CDC’s Advisory Committee, I can state that it was

not our intent to suggest to Medicaid providers that the use of a questionnaire

should determine whether children, particularly in the most vulnerable age

group of 6 - 36 months, should receive a blood lead test. The CDC Statement

is unequivocal that for this population, a blood lead test must be conducted at

least once by the time a child reaches 12 months and again by 24 months of

age, even if the responses to the assessment questions indicate the child is at

"low risk" of lead poisoning. CDC Statement 43. The CDC screening schedule

is based on the fact that children’s blood lead levels increase most rapidly at 6 -

12 months and peak at 18 - 24 months. Id. at 42. The incidence of high blood

lead levels among this population is so high, it makes little sense to try to

ascertain with a questionnaire who within this group is at "high risk." See id. at

Figure 6 - 1. The CDC Statement explicitly states that for this group the

questionnaire is not a substitute for a blood lead test. Id. at 42.

Rosen deck at H 35, see also U 36; see Reigart deck at 11 9

According to the CDC Statement, all children between 6 and 72 months are at risk from

lead poisoning, CDC Statement 42. The limited purpose of a high or low risk categorization

in the CDC Statement is to establish the schedule for follow-up screening and intervention,

id. at 43-45, not to trigger a system of triage for initial screening. Following up an initial EP

test with a blood lead test if the EP test score is high does not cure the inability of the initial

EP test to detect lead poisoning.3

Indefinite Transition Period. Driven by concerns for administrative convenience and cost

savings, federal defendant has focused upon that portion of the CDC Statement that recognizes

the need for a transition to universally mandated use of blood lead testing. It uses this

language to support its contention that limited laboratory capacity for processing blood lead

tests in some states justifies permitting any state Medicaid program to continue to use EP tests

for "low" risk cases during a transition period of undefined length. USA motion at 19.

Federal defendant provides no substantiation of any lack of laboratory capacity or its

3The CDC Statement does contain language about elevated EP results being followed

with a blood lead test to determine if lead poisoning is responsible for the elevation. CDC

Statement 48. However, the elevated EP results to which the CDC Statement referred are

those at or above 35 /xg/dL, i.e.., levels at which the EP test is sensitive, not at lead blood

levels of 10-25 fig/dL for which "the EP test is not a sensitive test." Id. The limited

purpose of the follow-up blood lead test dictated by the CDC is to determine if the

elevated EP result is caused by lead poisoning or some other health condition, such as iron

deficiency. Id. It is not to detect where there is a false negative EP result, the essential

defect of the EP test. See Mushak deck at 11 25 ("[T]he EP test does not act as a

preventive test which allows the health care provider to detect lead poisoning at its early

more manageable stages. Rather, the EP test can only accurately predict that unacceptably

high lead exposure and greater risk of more severe poisoning have already occurred").

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 16

extent. Dr. Rosen, in any event, establishes that the purported lack of laboratory capacity is

a mere pretext.

I cannot fathom why, more than a year after the CDC Statement

dictated blood lead tests as the reasonable standard of medical practice, a

state’s medical care providers’ capacity of performing the tests, particularly if

reimbursable under the Medicaid program, would be limited.

The laboratory capacity certainly exists among the large commercial

laboratories, such as Roche, MetPath, or Smith Kline. Similar capacity must

exist at State and local public laboratories. The large commercial laboratories

are located around the country and routinely assess blood samples of Medicaid

patients in-state or out-of-state. These laboratories can process the blood lead

results of any children in the Medicaid program and be reimbursed by the

Medicaid program. See Declaration of William Hiscock 1111 15, 18.

CDC’s 1991 Statement did allow a "grace period" for transition from EP

to blood lead testing. As Chairperson of CDC’s Advisory Committee, I can

state that our intent was to provide a transition of up to a year for state and

local agencies to order proper equipment and implement blood lead

measurements as the diagnostic test for childhood lead poisoning. One year is

more than twice the time required to mount such a laboratory capability de

novo, including the time required to order an instrument, train a technician, and

set up a reporting system. The transition period was not intended to be a

bureaucratic vacation to extend until the next CDC Statement is issued. The

next CDC Statement, like the last, may not be issued for another six years or

more.

Although HCFA’s policy to reimburse any blood lead tests that are

performed eliminates cost as a factor, blood lead testing is not expensive

anyway.4 Throughout the Montefiore Medical Center-Albert Einstein College

of Medicine complex, including all their satellite clinics, we have established

that the total cost per blood lead test does not exceed $12 - 13. Colleagues’

findings in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and North Carolina confirm these

results. One need only check the rates from the commercial mass laboratories

to find their charges in the same range.

4Of course, concern about cost savings is clearly a motivating factor here. The EP test

costs Medicaid less than $10, while a blood lead test costs between $10 - $15, depending on

volume and economies of scale. Mushak deck at 11 28. So long as the EP test is used, the

federal defendant saves on its laboratory testing expenditures - particularly in light of the

fact that providers are already using the EP test to detect other childhood conditions, such

as iron deficiency. Such cost concerns do not, however, provide adequate justification for

the continued use of the EP test for lead poisoning in young Medicaid eligible children.

Because of its unreliability for accurately predicting elevated Pb-B below 40 ;u.g/dL level,

the EP test is probably a waste of money for lead absorption prediction. Id. And, as

noted in the 1988 Report to Congress, direct lead blood level assessment is particularly cost -

effective in the long run. This was demonstrated by comparing data on the costs of

treating children who are poisoned because early lower levels of lead intoxication were not

detected by screening with the costs of testing. In the example used in the Report, the ratio

of medical costs to child screening costs was an astounding 50:1 in 1986 dollars (about

$20,000 to $25,000 per child in 1992 health care dollars). Id. at 29, 31.

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 17

Rosen decl. at 1111 25-27, 29; Mushak deck at 11 28.5 Dr. Mushak, an author of the Report to

Congress comes to the same conclusion from a public health perspective. Mushak decl. at 11

20 ("Delaying blood lead testing of Medicaid eligible children is . . . not justified by concerns

regarding laboratory capacity.").

The CDC called for a transition to blood lead testing over a year ago. Over three years

have passed since Congress mandated lead blood level testing as part of the EPSDT screen.

HHS’s current policy for lead screening is unacceptable and is, in fact, premised upon an

acknowledgement that what it is doing is wrong. In the September 1992 State Medicaid

Manual, HHS allows that the EP test is now an "inappropriate" test to detect lead poisoning.

It recognizes that lead blood levels cannot be assessed by asking questions. And, it states that

a lead blood test is the test of choice when measuring blood lead levels. Yet, it uses

statements contained in the later-adopted CDC Statement to excuse a testing scheme for the

poor that delays indefinitely implementation of the Congressional mandate for blood lead

testing. As established by the experts, the question of the appropriate test for lead exposure

and lead poisoning in Medicaid children is not arguable on cost or other logistical grounds

involving laboratory capacity, see Rosen decl. at 1111 25 - 29; Mushak decl. at U1I 29 - 31; Reigart

decl. at U 13. Such arguments do not justify the federal defendant’s failure to require reliable

lead blood level testing of the very group that all participants in this case agree is most at risk

of and tragically damaged by lead poisoning. The federal defendant has failed to meet its

burden of showing why further delay — now in the form of an indefinite transition period —

should be allowed.

////

5Even if these nationwide resources were somehow not available in a

particular area, it is not overly difficult or costly to develop independent

laboratory capacity, as we did years ago at Montefiore Medical Center. The

laboratory can be staffed with a laboratory technician and a clerk-typist with

a computer. The required instrumentation currently runs approximately

$60,000 - 75,000, plus $10,000 in consumables per year. This country

certainly has the technology to perform universal blood lead tests for all

Medicaid eligible children.

Rosen decl. at 11 30.

C:\DOQTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 18

Conclusion

For the above reasons, amici proposed plaintiff-intervenors request that the Court deny

federal defendant’s alternative motions to dismiss and for summary judgment.

Dated: November 23, 1992

Respectfully submitted,

Edward B. Cloutman, III

Texas Bar No. 04411000

Law Office of Edward B. Cloutman, III

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, TX 75226

(214) 939-9222

B y________________________________

Edward B. Cloutman, III

Julius L. Chambers

Alice Brown

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Bill Lann Lee

Kirsten D. Levingston

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

315 West Ninth Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

By____________

Bill Lann Lee

Jane Perkins

National Health Law Program

313 Ironwoods Drive

Chapel Hill, NC 25716

(202) 887-5310

B y ________________________

Jane Perkins

Carlene NcMulty

North State Legal Services

114 West Corbin Street

Hillsborough, N.C. 27278

(919) 732-8137

C:\DOQTHOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 19

Lucy Billings

Marie-Elena Ruffo

Bronx Legal Services

579 Courtlandt Avenue

(212) 993-6250

By___________________________

Lucy Billings

Attorneys for Amici

People United for a Better Oakland, et al

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM 20

DECLARATION OF BILL LANN LEE

I, BILL LANN LEE, declare and say:

1. I am one of the counsel for the amici curiae and the proposed plaintiff-

intervenors People United for a Better Oakland, et al.

2. Attached hereto as Exhibit A is a true and accurate copy of McElvaine, M.D.,

Orbach, H.G., Binder, S., Blanksma, L.A., Maes, E.F., & Krieg, R.M., Evaluation of the

Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin Test as a Screen for Elevated Blood Lead Levels, 119 J. of

Pediatrics 548 (1991).

3. Attached hereto as Exhibit B is a true and accurate copy of Report of the

House Budget Comm, on H.R. 3299, 101 Cong., 1st Sess. (September 20, 1989), reprinted in

Medicare and Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 596 (October 5, 1989) ( pp. 398 - 410.

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed the 23rd day of November, 1992, at Los Angeles, California.

Bill Lann Lee

C:\DOC\THOMPSON\PLEADING\AMICIMEM