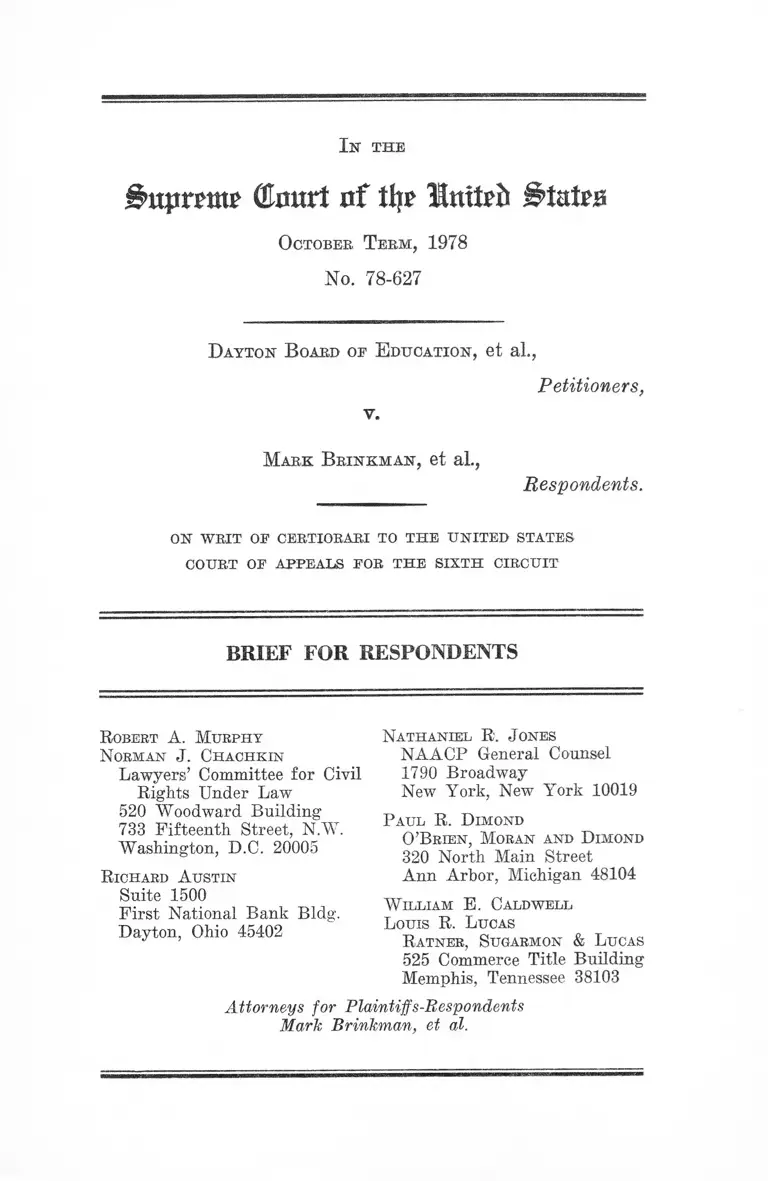

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Brief for Respondents, 1979. 0bd33e77-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2f6da85b-d831-4cc5-a129-6ed953ce9284/dayton-board-of-education-v-brinkman-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Bxvptzmt (tart nf tlj? Hmttb States

O ctober T er m , 1978

No. 78-627

D ayton B oard oe E ducation , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Mark Brinkman, et al.,

Respondents.

o n w r i t o e c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s

COURT OE APPEALS EOR TH E SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

R obert A. Murphy

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

R ichard A ustin

Suite 1500

First National Bank Bldg.

Dayton, Ohio 45402

Nathaniel R. Jones

N A A CP General Counsel

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Paul R. Dimond

O’Brien, Moran and Dimond

320 North Main Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

W illiam E. Caldwell

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Respondents

Mark Brinkman, et al.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ........................................................ iii

Opinions Below ....................................................... 1

Counter statement of Questions Presented.................... 2

Counterstatement of the Case......................................... 2

A. Prior Proceedings ............... 2

B. The Dayton School District: General Geog

raphy and Demography ...................... 9

C. The Pre-Brown Dual System................. .... ....... 12

D. Continuation of the Dual System After Brown 32

1. Faculty and Staff Assignments..............—~ 32

2. School Construction, Closing and Site Selec

tion ....................... 38

3. Optional Zones and Attendance Boundaries 43

4. Grade Structure and Reorganization ......... 52

5. Pupil Transfers and Transportation.......... 53

6. The Board’s Rescission of Its Affirmative

Duty ...................... ...........................-..... -........ 59

7. The Dual System at the Time of T ria l....... 65

E. The Remedy ....................... 67

Introduction and Summary of Argument...................... 74

Introduction .................. 74

Summary of Argument ............................................. 83

PAGE

11

Argument ........................................................................... 88

I. At the Time of Trial in This Case the Dayton

Board of Education Was Operating a Segregated

School System Within the Meaning of Brown v.

Board of Education; That System Had Existed

Throughout This Century; It Became Unconstitu

tional Upon Brown’s Correct Interpretation of the

Fourteenth Amendment in 1954; But, Instead of

Being Dismantled, Thereafter It Was Deliberately

Compounded Through the Time of T ria l.............. 88

A. A Dual School System, Within the Prohibition

of the Fourteenth Amendment and Brown v.

Board of Education, May Be Brought Into

Being as Effectively by Local Administrative

Policy and Practice as by State Constitutional

and Statutory Mandate; Such a System Can

not Stand Under the Fourteenth Amendment

PAGE

Even if It Also Violates State L aw .................. 94

B. At the Time of Brown and Ever After Peti

tioners Operated a Dual School System in Fact 99

1. The Board’s Pre-Brown Conduct ............... 99

2. The Nature of the Dual System at the Time

of Brown ........................................................ 108

3. The Post-Brown Era ................................... 113

II. The Remedial Principles of Green and Swann En

title Respondents to a Systemwide “Root and

Branch” Desegregation Remedy Designed to

Eradicate All Vestiges of the Dual System;

Petitioners Have Not Met, and Have Not Even

Attempted to Meet, Their Burden of Demonstrat

ing That This Constitutional Goal Can Be Ful

filled With a Less Extensive Remedy .................. 125

I l l

A. In the Context of an Intentional, Although

Non-Statutory, Dual School System, the “In

cremental Segregative Effect” Inquiry of

PAGE

Dayton I is Governed by Green and Swann .... 126

B. Green and Swann Require a Systemwide

Remedy in This Case......................................... 130

III. Alternatively, Respondents Have Established,

Under Keyes and the Facts Essentially Conceded

by Petitioners, and Unrebutted Prima Facie Case

of Systemwide Intentional Segregation Neces

sitating a Systemwide Rem edy............................. 135

A. Respondents Have Made Out an Unrebutted

Prima Facie Case of Intentional Across-the-

Board Discrimination......................................... 136

B. Respondents Have Also Proved Their Entitle

ment to a Systemwide Desegregation Remedy 139

IV. The Decisions by This Court in the Columbus and

Dayton School Cases Are Critical to Meaningful

Constitutional Review of Remaining Dual School

Systems .........................................-........................... 140

C o n c l u s io n ............................................... .......................................... 144

T able op A u thorities

Cases:

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973)

(en banc) .................................................. -................... 00

Adiches v. S. H. Kress <& Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) .....95, 96

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ:, 396 U.S.

19 (1969) 75

93

American Tobacco Co. v. United- States, 147 F.2d 93

(6th Cir. 1944) ..............................................................

Arthur v. Nyquist, 573 F.2d 134 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

47 U.S.L.W. 3224 (Oct. 2, 1978) ............ .................... 141

Austin Independent School Dist. v. United States, 429

U.S. 990 (1976) ................................................. .......... 7

Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S. 665 (1944) .... 31

Berenyi v. Immigration Service, 385 U.S. 630 (1967) .. 31

Bigelow v. RKO Radio Pictures, Inc., 327 U.S. 251

(1946) ................ .................... ................ ...................... 129

Board of Education v. State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N.E.

373 (1888) .............. ...... ..................... ........ ....... .......... 12

Board of Education of School District of City of Day-

ton v. State ex rel. Reese, 114 Ohio St., 188, 151 N.E.

39 (1926) ............ ............................ ...... .......................14,17

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973)

(en banc) ............................... ..... ......... .......... ........... 52

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) 75

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F.2d 684 (6th Cir. 1974) ..passim

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 518 F.2d 853, cert, denied sub

nom., 423 U.S. 1000 (1975) .....................................1, 6, 67

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir. 1976),

vacated sub nom., 433 U.S. 406 (1977) ............ 2,6,71,72

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 583 F.2d 243 (6th Cir. 1978),

cert, granted, 47 U.S.L.W. 3463 (8 January 1979) ..passim

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .........passim

Broivn v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .........passim

Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976) 60

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ...................... 75

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

226 (1969) 75

V

Garter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

290 (1970) ........................................................... -....... 75

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) ............... 3

Clemons v. Board of Educ. of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d 853

(6th Cir. 1956) .................................................. -........ 83, 98

Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide <& Carbon Corp.,

370 U.S. 690 (1962) ................. ......... ...............-.......92,93

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................. 75,97

PAGE

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman,

(1977) ............. ...............................- ....

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs, 402

433 U.S. 406

........... .........passim

U.S. 33 (1971) 81

Evans v. Buchanan, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

434 U.S. 880 (1977); 582 F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978),

cert, pending ........ .......... .....— ................ .................. 141

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) .......... 83, 92, 94, 97

Franks v. Bowan Transportation Co., 424, 747 (1976) .... 129

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) ~ 116

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) .................. 48

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) ................ .......... ................................................. 75

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ....passim

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) _____ ___ _________ -.................. 75

Hart v. Community School Board, 512 F.2d 37 (2d Cir.

1975) ......... ....... ................-.... -................................. 140-141

Higgins v. Board of Educ., 508 F.2d 779 (6th Cir. 1974) 141

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) .............. ........... 140

Home Tel. & Tel. Co. v. City of Los Angeles, 227 U.S.

278 (1913) .......................... ......................... -.................... 83,95

VI

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ...................... 123

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) ........................... 140

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School Hist., 500 F.2d

349 (9th Cir. 1974) .............. ....................................... 141

Kansas City Star Co. v. United States, 240 F.2d 643

(8th Cir. 1950) .............................................................. 93

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, de

nied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973) .........................................36,141

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1974) .... 60

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) .......passim

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 521 F.2d 465 (10th Cir.

1975), cert, denied sub nom., 423 U.S. 1066 (1976) .... 141

Lewis v. Pennington, 400 F.2d 806 (6th Cir. 1968) ....... 129

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......... 135

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ...................... 116

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ..................112,139

Monroe v. Board of Gomm’rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) ............................................................................. 75

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ..................... 83,95,96

Montague & Co. v. Lowry, 193 U.S. 38 (1904) .............. 93

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 103 (1935) ...................... 95

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580 (1st Cir. 1974), cert.

denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) ........................................... 140

Mt. Healthy City School Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle,

429 U.S. 274 (1977) .................................... 129

NAACP v. Lansing Bd. of Educ., 559 F.2d 1042 ( 6th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1065 (1978) ......... 141

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881) ....................... 95

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swcmn, 402 U.S.

43 (1971) ................................................................... 81,116

PAGE

V l l

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 397 U.S. 232

(1970) ............................ ................................................ 75

Oliver v. Michigan State Bd. of Educ., 508 F.2d 178

(6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) .... 141

Pasadena City School Board of Education v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1976) ............................ ....... ........ .....72,133

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .............. ....... 99

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould School Dist., 391

U.S. 443 (1968) .......... .................................................. 75

Raymond v. Chicago Union Traction Co., 207 U.S. 20

(1907) ................................................ ............................ 95

Beitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ..................66,123

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............................. 75

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945) ........ ..... 88, 95

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) (en bcmc), rev’d on

other grounds sub nom., 396 U.S. 290 (1970) .......... 37

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ___ _____ __ 97

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911) 93,108

Story Parchman Paper Co. v. Paterson Paper Co., 282

U.S. 555 (1931) ......................................... ................. 129

Swarm v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ............... ........ .................................... ...... ._passim

Swann v. Charlott e-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300 F.

Supp. 1358 and 1381 (W.D.N.C. 1969); 306 F. Supp.

1291 and 1299 (W.D.X.C. 1969) ................................. 77

Terry y. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953) ............................. 97

United States v. Board of School Comm/rs, 332 F. Supp.

655 (S.D. Ind. 1971) ..................................... ............... 17

PAGE

vm

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 474 F.2d

81 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 413 TT.S. 920 (1973) ....41,141

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941) .............. 95

United States v. Columbus Municipal Separate School

Dist., 558 F.2d 228 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434

U.S. 1013 (1978) ............................... 141

United States v. E. I. Dupont DeNemours <& Co., 353

U.S. 586 (1957) .......... .................. .............................. 31

United States v. General Motors Corp., 384 U.S. 127

(1966) ...................................................................... 31

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) .... 77

United States v. John J. Felin & Co., 334 U.S. 624

(1948) .............................................................. 31

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ....................................... 35, 37,75

United States v. Oregon State Med. Soc., 343 U.S. 326

(1952) ............................................................................. 92

United States v. School District of Omaha, 521 F.2d

520 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 946 (1975) ....51-52

United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, 565 F.2d 127

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1064 (1977) ........... 141

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., 407

U.S. 484 (1972) ................ 86,112

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 457 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972) (en banc) .................. 52

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 564 F.2d 162

and 579 F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, pending..... 141

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S.

364 (1948) ..................................................................... 31

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 338 U.S. 338 (1949) .. 31

PAGE

IX

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Homing

Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .......... .............. 84,115,129

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313 (1880) ................... ...... 95

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) .................... 84,123

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ................................................................................. 86,112

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 117 U.S. 356 (1886) .................... 83,95

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395

U.S. 100 (1969) ................................................................ 31,129

Statutes and Rules:

42 U.S.C. §1981 .............................................................. 3, 4, 7, 91

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................ 95-96

42 U.S.C. §1983-1988 ......................................................3, 4, 7, 91

85 Ohio L aws 3 4 ....................................................................... 12

Ohio E ev. Code §3313.48 ........................................................ 114

Ohio R ev. Code §3319.01.............. 64

F ed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) ................................................. ............. 31

F ed. R. Civ. P. 53 ..................................................................... 69

Other Authorities:

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. (1871) ........................ 96

U.S. Civil R ights Commission, Desegregation of the

Nation’s P ublic Schools: A Status R eport (Feb.

1979) .............................. 143

Ohio A. G. Opinion No. 6810 (9 July 1956) ............62, 83, 97

PAGE

In t h e

(Emtrt nf tb? Htti&b States

O ctober T e r m , 1978

D ayton B oard o f E ducation , et al.,

Petitioners,

V.

M ark B r in k m a n , et al.,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Opinions Below

The district court’s initial liability ruling of 7 February

1973, now reported at 446 F. Supp. 1254-65 as an appendix

to the court’s latest ruling, is reprinted in the appendix to

the petition for certiorari (“Pet. App.” ) at pp. la-25a. The

court’s first remedy order was entered 13 July 1973. Pet.

App. 26a-31a. The first opinion of the court of appeals is

reported as Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F.2d 684 (6th Cir.

1974) (Brinkman I). Pet. App. 32a-69a.

On remand from Brinkman I, the district court entered

orders on 7 January 1975 (Pet. App. 70a-72a) and 10

March 1975. Pet. App. 73a-88a. The court of appeals opin

ion in Brinkman 11 is reported at 518 F.2d 583 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied sub nom., 423 U.S. 1000 (1975). Pet. App. 89-

98a.

2

On remand from Brinkman 11, the district court entered

remedial orders and judgments on 29 December 1975 (Pet.

App. 99a-109a), 23 March 1976 (Pet. App. 110a-13a), 25

March 1976 (Pet. App. 114a-16a) and 14 May 1976. Pet.

App. 117a. The court of appeals’ opinion in Brinkman 111

is reported at 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir. 1976). Pet. App.

118a-23a. This Court’s opinion, vacating and remanding,

is reported as Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 TT.S.

406 (1977) (Dayton I). Pet. App. 124-41a.

On remand from Dayton 1, the district court filed an

opinion dismissing the complaint on 15 December 1977,

which is reported at 446 P. Supp. 1232 (S.D. Ohio). Pet.

App. 142a-88a. The court of appeals’ opinion in Brink-

man IV is reported at 583 F.2d 243 (6th Cir. 1978). Pet.

App. 189a-217a. This Court granted certiorari on 8 Janu

ary 1979.

Counterstatement of Questions Presented

Whether, as the court of appeals held below, the Dayton

Board of Education was operating a basically dual school

system at the time of trial, necessitating a systemwide de

segregation remedy?

Counterstatemenet of the Case

A. Prior Proceedings.

This suit commenced on 17 April 1972 with the filing of

a complaint by black parents and their school children1

1 In their petition for certiorari (pp. 20-21) and in their brief

(pp. 54-56), petitioners make a frivolous attack on plaintiffs’ stand

ing to sue. Despite the fact that this issue had been resolved against

petitioners by the district court and by the court of appeals in

3

seeking to disestablish the racially dual system of public

schooling in Dayton, Ohio, pursuant to the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments and their contemporaneous im

plementing legislation, 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983-1988.

Complaint, filfl, 12. Defendants included the Dayton Board

of Education, its individual members and Superintendent

of Schools and the State Board of Education and respon

sible state officials. Complaint, HU4-10. Following exten

sive admissions by all defendants (App. 53-78),2 the trial

judge conducted an evidentiary hearing from 13 Novem

ber to 1 December 1972, limited to whether the acts of the

Dayton Board “have created segregated educational facili

ties in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” Pet. App.

Brinkman I, it was resurrected by petitioners before this Court in

Dayton I. We responded by demonstrating that individual respon

dents have a real present-day stake in this litigation, and that the

case has properly proceeded as a class action. See Brief for Re

spondents at 95-101 in Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, No. 76-

539. Although petitioners’ standing argument was a jurisdictional

one, which the Court would have been obliged to look into even on

its own motion, cf. City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 TJ.S. 507 (1973),

the Court’s opinion in Dayton I elected not to address the standing

argument and proceeded on the basis that jurisdiction was estab

lished. Petitioners’ standing contention was thus necessarily re

solved against them in Dayton I ; and, on remand therefrom, they

did not renew the argument either in the district court or in the

court of appeals. They are therefore foreclosed from relitigating

that issue in this Court. In all events, the issue must be resolved

in respondents’ favor, for the reasons set forth in our brief in

Dayton I, cited above.

2 “ App.” references are to the three-volume appendix filed herein.

When the exhibit volume is referred to, the page number is fol

lowed by “Ex.” Trial exhibits not reproduced in the exhibit volume

of the appendix are designated “ P X ” for plaintiffs’ exhibits and

“D X ” for defendants’ exhibits. References to the original tran

script are designated as follows: “ R.I.” for the twenty-volume,

consecutively-paginated transcript of the violation hearing in No

vember and December 1972; “R.II.” for the February 1975 re

medial hearings; “R.TII.” for the remedial hearings in December

1975 and March 1976; and “ R.IV.” for the November 1977 hearing

on remand from this Court.

4

2a; also Pet. App. 34a, 143a, 188a.3 The plaintiffs intro

duced substantial additional evidence showing that the

Dayton public schools had been riven by a long and contin

uous history of intentional system-wide segregation lead

ing to the creation and maintenance of a basically dual

system from long before Brown through the time of trial;

the defendants countered by arguing that any discrimina

tion had only minor effect and, in any event, had been

dissipated by the passage of time. The district court is

sued an opinion on 7 February 1973 finding “ racially im

balanced schools, optional attendance zones, and recent

Board action [i.e., the 3 January 1972 rescission of a

system-wide program of desegregation], which are cumu

latively in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” Pet.

App. 12a.4 By its 13 July 1973 supplemental order on

remedy, the district court approved a “ plan” eliminating

optional zones and required a “free choice” election pro

cess for in-coming high school students, based on its read

3 Plaintiffs filed the action in the Columbus rather than the Day-

ton division of the district court because of the joint and inde

pendent allegations against the State level agencies and officials,

all located in Columbus. The district court denied defendants’

motions to dismiss for improper venue or, in the alternative, for

transfer to the Dayton division on these grounds. E.g., Pet. App.

33a. Yet the trial judge then deferred hearing on the claims against

the State defendants; and, to date, these claims, as well as those

against all defendants arising under the Thirteenth Amendment

and the applicable federal civil rights statutes, 42 IJ.S.C. §§1981

and 1983-1988, have never been heard. (At the beginning of the

November 1972 trial, Judge Rubin noted that “ [t]his is a limited

hearing on this case and it is intended to be a preliminary inquiry.”

App. 1.)

4 The district court determined that the case was a “ class action

by the parents of black children attending schools operated by the

defendant Dayton (Ohio) Board of Education.” Pet. App. la.

The court also credited plaintiffs’ pre-Brown evidence of official

racial discrimination as the policy of the Dayton Board (Pet. App.

2a-4a), but it did not relate that conduct to the evidence of post-

Brown discrimination nor otherwise attach any legal significance

to it. E.g., Pet. App. 3a.

5

ing of Mr. Justice Powell’s dissenting opinion in Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 226-227 (1973). Pet. App.

29a-31a.

The Dayton Board appealed, claiming that there was no

continuing constitutional violation; and plaintiffs cross-

appealed, contending that the district court had erred in

failing to make additional violation findings relating to al

most all aspects of the operation of the Dayton public

schools and that the remedy ordered failed to overcome the

pervasive effect of the proven violations, including the

deliberate perpetuation of a basically dual system from

the time of Brown through the time of trial. In its 20

August 1974 opinion in Brinkman 1, 503 F.2d 684 (Pet.

App. 32a), the court of appeals discussed at somewhat

greater length than had the district court both the pre-

Brown evidence of intentional discrimination (Pet. App.

39a-40a) amounting to a “basically dual system” (Pet. App.

56a) and the “ serious questions” (Pet. App. 66a) as to

whether the Board’s conduct following Brown relating, for

example, to staff assignment, new school construction and

reorganization, should have been included within the

“cumulative violation” of the Equal Protection Clause

found by the district court. Pet. App. 56a-67a. But the

court of appeals reserved ruling on these issues, rather

than expressly supplement or reverse the constitutional

violation findings of the district court as requested by

plaintiffs in one prong of their cross-appeal. Pet, App. 56a,

67a; also Pet. App. 194a. Thus, the court of appeals only

affirmed the three-part “ cumulative violation” (Pet, App.

67a) but, nevertheless, reversed the trial judge’s remedy

and remanded for development of a plan of broader scope.

Pet. App. 68a-69a.

Following additional remedial proceedings on remand

in the district court (Pet. App. 70a, 73a), the court of ap

6

peals in its 24 June 1975 opinion in Brinkman II directed

promulgation and implementation of “a system-wide plan

for the 1976-77 school year” without reaching the reserved

issues. 518 F.2d 853, 857 (Pet. App. 96a). On remand, fol

lowing the appointment of an expert (murdered in the

midst of his desegregation planning in the Federal Build

ing in Dayton), the appointment of a master, and eviden

tiary hearing (Pet. App. 99a-106a), the district court

approved a system-wide plan pursuant to orders of 23

March and 14 May 1976. Pet. App. 110a, 117a. On appeal

by the Dayton Board, the court of appeals affirmed, again

without reaching the reserved questions. 539 F.2d 1084

(Pet. App. 118a). Following denials of stays by the court

of appeals and Circuit Justice Stewart, the system-wide

plan was implemented in September 1976 and has success

fully operated to this day without disruption.

On certiorari, this Court reviewed the proceedings and

opinions below. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

433 U.S. 406 (1977) (hereafter “Dayton I ” ). Noting the

ambiguity of the district court’s opinion (433 U.S. at 412-

14), the Court evaluated each aspect of the three-part

“ cumulative violation” holding and determined that, at

most, any constitutional violation related solely to “high

school districting,” i.e., “ optional attendance zones for . . .

three Dayton high schools.” 433 U.S. at 413. The Court

admonished the court of appeals for failing to review—

i.e., to affirm, to supplement or to reverse (in contrast to “ to

discuss” )—the limited and ambiguous violation findings of

the district court in view of the extensive record evidence

of intentional segregation concerning all aspects of the

historic and continuing operation of the Dayton public

schools. 433 U.S. at 416-18. Left only with the limited

findings of the district court, this Court held that the court

of appeals erred in imposing a system-wide plan for viola

7

tions of patently lesser scope, i.e., optional zones affecting

only three high schools. 433 U.S. at 417-18. In view of the

confusion at various stages in the courts below and the

substantial claim that the extensive record revealed addi

tional violations, the Court therefore remanded for thor

ough judicial review and detailed findings but left the sys

tem-wide plan in effect pending further proceedings. 433

U.S. at 418-21.

Pursuant to this Court’s mandate, the court of appeals

remanded the case to the district court for further proceed

ings. 561 F.2d 652. The district court conducted a brief

evidentiary hearing, 1-4 November 1977, again limited to

the intentionally discriminatory conduct of the Dayton

Board. Nevertheless, the district court dismissed the plain

tiffs’ complaint by opinion and judgment issued 15 Decem

ber 1977. Pet. App. 142a. The opinion is based solely upon

finding no continuing violation of the Equal Protection

Clause (Pet. App. 188a) and makes no determination con

cerning the plaintiffs’ claims against the State defendants

and claims arising under the Thirteenth Amendment and

federal civil rights acts (42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983-1988)

against all defendants. See note 1, supra. The opinion be

gins by noting: “The course of this protracted litigation

has been marked by conceptual differences not only as to

the facts, but as to the legal significance of those facts.”

Pet. App. 143a. Still guided by Mr. Justice Powell’s mi

nority view (quoting the separate opinion in Austin Inde

pendent School Dist. v. United States, 429 U.S. 990, 995

and n.7 (1976); see Pet. App. 146a-47a), the district court

applied a restrictive view (e . g Pet. App. 153a, 157a-60a,

162a-69a, 171a, 180a) of this Court’s decision in Dayton I

with respect to causation and effect. Pet. App. 146a-47a;

also Pet. App. 149a, 154a, 159a, 171a. The district court

then proceeded to resolve all disputed facts concerning in

8

tent against the plaintiffs and further determined that the

numerous admitted or uncontroverted intentionally segre

gative and discriminatory policies and practices of the

Dayton Board were isolated, attenuated, or otherwise had

no current “ incremental segregative effect.” E.g., Pet, App.

149a, 154a, 159a, 171a.

Plaintiffs promptly appealed. On 5 January 1978, the

district court denied plaintiffs’ motion to stay the judg

ment dismissing the case pending appeal; on the same day

the Dayton Board voted to reinstate pupil segregation be

ginning with the second semester. On 16 January 1978,

the court of appeals (a) granted plaintiffs’ motion to stay

the termination of the plan pending appeal and (b) ex

pedited the appeal.

The court of appeals, pursuant to the standards for ap

pellate review articulated by this Court in Dayton 1, 413

U.S. at 416-18, reviewed in its opinion (for the first time)

the trial judge’s findings concerning equal-protection viola

tions against the bulk of the evidence of intentional segre

gation. The appellate court concluded that the district

judge’s findings were clearly erroneous and his conclusions

were plainly wrong in all material respects. E.g., Pet. App.

194a and n.10, 196a, 199a, 202a, 206a, 210a, 211a, 212a. The

court below found that the record evidence “demonstrates

conclusively” (Pet. App. 194a) the following:

(1) The Dayton Board, through explicit policies and

covert practices amounting a system-wide program of

segregation, operated a basically dual system at the

time of Brown. Pet, App. 194a-205a.

(2) The Dayton Board refused at all times there

after to take any action to dismantle this dual system.

Pet. App. 205a-06a, 208a-09a, 216a.

9

(3) The Dayton Board opted instead to perpetuate

and to build upon the continuing dual system through

the time of trial by a variety of intentionally segrega

tive policies and practices, including racially motivated

faculty and staff assignment, optional zones, school

construction, and reorganizations of grade structure.

Pet. App. 206a, 209a-14a.

(4) The Dayton Board failed to show in what re

spect the pattern of one-race schools was not caused

by the system-wide impact of this longstanding, sys

tematic program of intentional segregation (Pet. App.

209a); instead, the direct evidence of the Dayton

Board’s intentionally segregative conduct following

Brown showed that it had perpetuated and com

pounded the basically dual system through the time of

trial through a variety of segregative practices of sys

temwide nature and impact. Pet. App. 216a-17a.

As a result, the court of appeals reversed the decision of

the district court on constitutional grounds and continued

the systemwide desegregation plan wdiich has been in oper

ation since September 1976. Pet. App. 217a.

Following denials of the Dayton Board’s applications

for a stay of judgment by the court of appeals, Circuit

Justice Stewart and Associate Justice Rehnquist, this

Court granted certiorari on 8 January 1979.

B. The Dayton School District: General Geography

and Demography.

As reflected in the report (App. 34-35) of the Master

previously appointed by the district court, the city of

Dayton has a population of 245,000 and is located in the

east-central part of Montgomery County in the south

western part of the state of Ohio, approximately 50 miles

10

due north, of Cincinnati. The Dayton school district is not

coterminous with the city; some parts of the school dis

trict include portions of three surrounding townships and

one village, while some portions of the city are included

in the school district of three adjacent townships. The

total population residing within the Dayton school district

boundaries is 268,000; the school pupil population is 45,000,

about 50% of whom are black. Prior to implementation

of the desegregation plan now in effect, the vast majority

of black and white pupils had separately attended schools

either virtually all-white or all-black in their pupil racial

composition. E.g., Pet. App. 48a-51a; App. 1-5-Ex. (PX

2A-2E), 212-16-Ex. (PX 100A-100E), 321-22-Ex. (DX CU).

The Dayton district is bisected on a north/south line

by the Great Miami River. Historically, the black popula

tion has been concentrated in the south-central and south

west parts of the city, primarily on the west side of the

Miami River and south of the east-west Wolf Creek, both

of which have long been effectively crossed at convenient

intervals, both literally and by school policies and prac

tices. See, e.g., maps in pocket part of appendix exhibit

volume. The area of black containment was originally

quite small and grew from 1913 through the time of trial

reciprocally with school board policies and practices de

signed to separate black pupils and staff from white. See

pp. 12-67, infra. The black population originally was con

tained in the southwest quadrant, but there is now also

a substantial black population in the northwest quadrant

across Wolf Creek. Extreme northwest Dayton and most

of the city east of the Miami River are and have been

heavily white in residential racial composition. See, e.g.,

App. 306-09-Ex. (DX BY) (census tract maps). The dis

trict court made the following finding as to the causes

of such residential segregation (Pet. App. 147a-48a)

(record citations and footnote omitted):

11

Since shortly after the 1913 flood, Dayton’s black pop

ulation has centered almost exclusively on the West

Side of Dayton. . . . Since that time this population

has moved steadily north and west. . . . Without ques

tion the prime factor in this concentration has been

housing discrimination, both in the private and public

sector. Until recently, realtors avoided showing black

people houses which were located in predominantly

white neighborhoods. . . . In the 1940’s, public housing

was strictly segregated according to race. . . . This

segregated housing pattern has had a concomitant im

pact upon the composition of the Dayton public schools.

See also, e.g., App. 80-83, 220-22-Ex. (PX 1433), 223-33-

Ex. (PX 143J), E.I. 189-210, PX 143E-M) (public housing

and relation to school discrimination); App. 143-48, E.I.

656, 663-65, PX 153-153B (Sloane, PHA, VA, FHA, and

relation to school discrimination); E.I. 881-84, 897-925,

952-53, App. 176-79 (Taeuber, residential and school segre

gation and discrimination); App. 518-22, E.I. 782-93, 2084-

2106 (offers of proof), PX 144 and 144A and E.I. 758-61

(local customs of housing and school segregation).6

6 Prom such testimony, evidence and offers of proof, it is manifest

that the trial court’s quoted finding—that in Dayton both official

racial discrimination and the dominant white community’s custom

and practice of racial exclusion (compared to other factors like

choice, economies, birth rates or in-migration) have been primary

causal elements in the marked historic and continuing residential

segregation— is indisputable. (One of the issues still in much

dispute in this case, however, is whether school discrimination

contributed to the prevailing local custom and practice of almost

complete residential segregation; whether school policies and

practices were also motivated, at least in some significant part, by

the racial discrimination prevailing in other aspects of the local

community; and whether school discrimination and segregation

operated reciprocally with such residential discrimination and

segregation to create and perpetuate a dual school system. This is

(Footnote continued on next page)

12

Geographically and topographically there have been and

are no major obstacles to complete desegregation of the

Dayton school district. Pet. App. 121a. The Master deter

mined that where pupil transportation is necessary, the

maximum travel time would be about twenty minutes. App.

39. As found by the Board’s experts, due to the compact

nature of the system, “ the relative closeness of the Dayton

Schools makes long-haul transportation!,] an issue in

many cities!,] moot here.” App. 438.

C. The Pre-Brown Dual System.

In 1887 the state of Ohio repealed its school segregation

law and attempted to legislate the abolition of separate

schools for white and black children. 85 Ohio Laws 34. That

statute was sustained the following year by the Supreme

Court of Ohio. Board of Education v. State, 45 Ohio St.

555, 16 N.E. 373 (1888). Although the Ohio courts had

occasion, some forty years later, specifically to remind

Dayton school authorities of this legal prohibition of sep

arate schools for black and white children, the laudable

goals of the 1887 legislation were not attained in Dayton 6

6 (Continued)

one of the issues that is addressed in the remainder of this brief.

It is sufficient for present purposes to note that the district court’s

limited findings do not answer the issue: for, even while crediting

evidence such as that cited above, it totally failed to consider these

same witnesses’ experience with the two-way, causally interwoven,

and reciprocal relationship between school discrimination and

segregation and housing discrimination and segregation in the

Dayton community. As we demonstrate in the Statement and

Argument hereafter, the evidence conclusively demonstrates that

segregative intent was a primary motivation in the Dayton Board’s

creation, perpetuation, and compounding of a dual school system,

pursuant both to explicit segregation policies and covert segrega

tion practices, that did in fact proximately cause or materially

contribute to the systematic pattern of one-race schooling extant

at the time of trial.)

13

until implementation of the desegregation plan now in

effect at the start of the 1976-77 school year.

Many of the facts which follow in this section were ad

mitted by all Dayton Board defendants in their responses

to plaintiffs’ pre-trial Requests for Admissions. See App.

53-78. These facts were also the subject of extensive and

largely uncontroverted evidence at trial.

The facts of racial segregation in the Dayton public

schools, as revealed by the record before the Court, begin

in 1912. In that year Louise Troy, a black teacher, taught

an all-black class just inside the rear door of the Garfield

school; all other classes in this brick building were occu

pied by white pupils and white teachers. App. 137. About

five years later, four black teachers and all of the black

pupils at Garfield were assigned to a four-room frame

house located in the back of the brick Garfield school

building with its all-white classes; and soon a two-room

portable was added to the black “annex,” making six black

classrooms and six black teachers located in the shadow

of the white Garfield school. App. 137-38. A four-room

“permanent” structure was later substituted for the two-

room portable (about 1921 or 1922), and eight black

teachers were thus assigned to the eight all-black class

rooms in the Garfield annex. App. 139. See also App. 53,

64, 73 (admission no. 1).

When Mrs. Ella Lowrey, a black teacher for several dec

ades in the Dayton system, performed her practice-teach

ing requirement with the black students in the “annex” at

Garfield in 1917, the four all-black classrooms contained 50

students each. App. 138. When the permanent structure

replaced the two-room portable in the early 1920’s, Mrs.

Lowrey taught a sixth-grade class of 62 black children,

before which she had taught a fourth-grade class of 42

14

black children while her white counterpart in the main

“white” building had a class of only 20 white children.

R.I. 624-25; App. 139. In Mrs. Lowrey’s words, “ doing 40

years service in all in Dayton, . . . I never taught a white

child in all that time. I was always in black schools, black

children, with black teachers.” App. 143. [At one time

during this early history prior to 1931, one black teacher,

Maude Walker, taught an ungraded class of black boys at

the Weaver school. All other black teachers in the system

were assigned to the black annex at Garfield. App. 93.]

About 1925 school authorities learned that two black

children, Robert Reese and his sister, had been attending

the Central school under a false address, even though they

lived near the Garfield school. They had accomplished this

subterfuge by walking across a bridge over the Miami

River. The Reese children were ordered by school au

thorities to return to the Garfield school, but their father

refused to send them to the black Garfield annex. Instead,

he filed a lawsuit in state court seeking a writ of man

damus to compel Dayton school authorities to admit chil

dren of the Negro race to public schools on equal terms

with white children. R.I. 526-29; App. 115-16. In a deci

sion entered of record on 24 December 1925, the Court of

Appeals of Ohio denied a demurrer to the mandamus peti

tion. This decision was affirmed by the Ohio Supreme

Court and Dayton school authorities were specifically re

minded that state law prohibited distinctions in public

schooling on the basis of race. Board of Education of

School District of City of Dayton v. State ex rel. Reese,

114 Ohio St. 188, 151 N.E. 39 (1926). See App. 53, 64-65,

73 (admission no. 2).

During the pendency of the Reese case, the eight black

teachers assigned to the Garfield annex were employed on

a day-to-day basis because school authorities did not know

15

whether the black teachers were going to be in the Dayton

system after the lawsuit. Black teachers would not be

needed if the courts required the elimination of all-black

classes, since the Board deemed black teachers unfit to

teach white children under any circumstances. App. 139-

40; see also App. 186.

Following the state court decision, Robert Reese and

a few of his black classmates were allowed to attend school

in the brick Garfield building, but the black annex and the

white brick building were otherwise maintained. Black

children were allowed to attend classes in the brick build

ing only if they asserted themselves and specifically so re

quested; otherwise, they “were assigned to the black

teachers in the black annex and the black classes.” App.

140-41.

During this time, there apparently were some other black

children also in “mixed” schools. For example, Mrs. Phyllis

Greer, who had direct contact with the Dayton public

schools over a fifty-year span as student, teacher, principal

and central administrator in charge of “ equal educational

opportunity” review (App. 85-86), attended “mixed”

classes at Roosevelt high school for three years prior to

1933. App. 89-90. But even when they were allowed to

attend so-called “mixed” schools, these black children were

subjected to humiliating discriminatory experiences within

school. At Roosevelt, for example, black children were not

allowed to go into the swimming pool and blacks had sep

arate showers while Mrs. Greer was there (App. 89); while

Robert Reese was at Roosevelt (after leaving Garfield),

there were racially separate locker rooms, and blacks were

allowed to use the swimming pool but not on the same day

as whites. App. 116. At Steele High School, black chil

dren were not allowed to rise the pool at all during this

period. App. 423-24. Even in the “mixed” classrooms

16

black children could not escape the official determination

that they were inferior beings because of the color of their

skin. Mrs. Greer vividly remembers, for example, “when

I went to an eighth grade social studies class I was told

by a teacher, whose name I still remember, . . . that even

though I was a good student I was not to sit in front of

the class because most of the colored kids sat in the back.”

App. 90. And she remembers with equal clarity that, while

in the second grade at Weaver, she “tried out for a Christ

mas play and my teacher wanted me to take the part of

an angel and the teacher who was in charge of the play

indicated that I could not be an angel . . . because there

were no colored angels.” App. 88-89.

Also, throughout this period, and until 1954, black chil

dren from a mixed orphanage, Shawen Acres, were as

signed across town to the black classes in the black Gar

field school (and also to the blacks-only Dunbar secondary

school, discussed infra), while the white orphan children

were assigned to nearby white classes and white schools.

App. 87-88, 523-24, 525. This practice was terminated

following the Brown decision in 1954 at a time when the

black community in Dayton was putting pressure on the

school administration to stop mistreating black children.

App. 184-Ex. (PX 28); App. 55, 67, 74 (admission no. 7

(cl))-

The black pupil population continued to grow at Gar

field, and another black teacher was hired and assigned

with an all-black class placed at the rear door of the brick

building. App. 141. In 1932 or 1933, Mrs. Lowrey {see p.

13, supra), was also placed in the brick building, again

with an all-black class “ in a little cubby-hole upstairs,”

making ten black teachers with ten black classes at Gar

field. App. 142. Finally, around 1935-36, after many of

the white children had transferred out of Garfield, school

17

authorities transferred all the remaining white teachers

and pupils in the brick building to other schools and as

signed an all-black faculty, principal and student body to

Garfield. App. 94, 142-43, 234-Ex. (PX 150 I ) ; PX 155

(faculty directories); see also App. 54, 65, 73 (admission

no. 2).

As the black pupil population was growing rather rap

idly during the 1930’s, not even the conversion of Garfield

into a blacks-only school was sufficient to accommodate

the growth. So, with the state court decision in Reese

then some nine years old, the Dayton Board also converted

the Willard school into a black school. The conversion

process was as degrading and stigmatizing as had been

the creation and maintenance of the Garfield annex and

the ultimate conversion of the brick Garfield into a black

school. In the 1934-35 school year, six black teachers (who

were only allowed to teach black pupils) and ten white

teachers had been assigned to the Willard school. In Sep

tember of 1935, the Board transferred all white teachers

and pupils to other schools, and Willard became another

school for black teachers and black pupils only. App. 93,

234-Ex. (PX 150 I ) ; PX 155 (faculty directories); App.

54-55, 66, 74 (admission no. 6).

At about this same time, in 1933, the new Dunbar school,

with grades 7-9, opened with an all-black staff and an all

black student body. App. 234-Ex. (PX 150 I). Mr. Lloyd

Lewis, who was present at its inauguration, testified that

the Dunbar school “ was purposely put there to be all black

the same as the one in Indianapolis [the Crispus Attucks

school, see United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 332

P. Supp. 655, 665 (S.D. Ind. 1971)] that I had left.” R.I.

1378; App. 530-33, 550-52. The Board resolution opening

Dunbar stated that grades 7 and 8 were to be discontinued

at Willard and Garfield (these two black elementary schools

18

served grades 7 and 8, whereas the system prior to 1940

was otherwise generally organized on a K-6, 7-9, 10-12

grade-strnctnre basis, App. 387), and that “attendance at

the Dunbar School be optional for all junior high students

for all 7th, 8th, and 9th grade levels in the City.” App.

191, 259-Ex. (PX 161A). Of course, this meant only all

black junior high students, since Dunbar had an all-black

staff who were not permitted by Board policy to teach

white children. App. 93, 191, 297; PX 155 (faculty direc

tories).

Within a very short time, grades 10, 11 and 12 were

added to the blacks-only Dunbar school. Then in 1942,

just two years after the Dayton school authorities had re

organized all schools to a K-8, 9-12 grade structure, the

Board again assigned the seventh and eighth grades from

the all-black Willard and Garfield schools to the all-black

Dunbar school. App. 191, 260-Ex. (PX 161B). Black

children from both the far northwest and northeast sec

tions of the school district traveled across town past many

all-white schools to the Dunbar school. App. 97-98, 211,

214, 296-97. Many white children throughout the west side

of Dayton were assigned to Roosevelt high school past or

away from the closer but all-black Dunbar high school.

Although some black children were allowed to attend

Roosevelt, those who became “behavior problems” were

transferred to Dunbar. App. 91. And other black chil

dren from various elementary schools were either assigned,

channeled, or encouraged to attend the black Dunbar high

school. App. 124-25, 214, 250-51.6 The most effective means

6 Prior to 1940, no high schools had attendance boundaries. App.

393-94. The black Dunbar school was located in close proximity

to the Roosevelt high school which, although it always had space,

apparently had too many black children. Along with Steele and

Stivers, these high schools were located roughly in the center of

the city and served high school students throughout the city. (In

19

of forcing black children to attend the blacks-only Dunbar,

of course, was the psychological one of branding them un

suited for association with white children. See pp. 15-16,

supra. As Mr. Reese testified, he “chose” Dunbar over

Roosevelt after suffering the humiliation of being assigned

to separate locker rooms, separate showers, and separate

swimming pools at Roosevelt: “I wanted to be free. I

felt more at home at Dunbar than I did at Roosevelt. . . .

You couldn’t segregate me at Dunbar.” App. 116-17. Simi

larly, Mrs. Greer testified: “ I went to Dunbar because I

felt that if there was going to be—if we were going to be

separated by anything, we might as well be separated by

an entire building as to be separated by practices.” App.

90. (Dunbar was also excluded from competition in the

city athletic league until the late 1940’s, thereby requiring

Dunbar teams to travel long distances to compete with

other black schools, even those located outside the state.

App. 90, 123, 133-34; R.I. 570.) See also App. 55, 67, 74

(admission no. 7).

Even these segregative devices were not sufficient to

contain the growing black population. So between 1943

and 1945, the Board, by way of the same gross method

utilized to convert the Willard school into a black school,

transformed the Wogaman school into a school officially

designated unfit for whites. White pupils residing in the

Wogaman attendance zone were transferred by bus to other

schools, to which all-white staffs were assigned. By Sep

tember 1945 the Board assigned a black principal and an

all-black faculty with an all-black student population to

addition, the Parker school had been a city-wide single-grade

school which served ninth graders. App. 408-09.) In 1940 at

tendance boundaries were drawn for the high schools with the

exception of Dunbar and a technical school (whose name varied),

both of which long thereafter remained as city-wide schools.

See p. 45, infra.

20

the Wogaman school. App. 90-91, 123-24, 234-Ex. (PX 150

I ) ; PX 155 (faculty directories); App. 54, 66, 74 (admis

sion no. 4).

Still other official devices were used to keep blacks segre

gated in the public schools. One such device, resorted to

regularly during the 1940’s and early 1950’s, was to cooper

ate with and supplement the discriminatory activities of

Dayton public housing authorities. Throughout this pe

riod, racially-designated public housing projects were con

structed and expanded in Dayton, subject to Board

approval.7 App. 80-83, 220-222-Ex. (PX 143 B). In 1942, the

Board transferred the black students residing in the black

De-Soto Bass public housing project to the Wogaman

7 App. 143-45. The district court had earlier refused to admit

any proof related to public housing and the school authorities

interaction therewith, including even the leasing of space and

assignment of one-race classes and staffs to rooms in the racially

designated projects, “until [plaintiffs] can establish that the

School Board participated in some fashion with the original

determination that this would be a white or black project

[. WJhatever else the Board might have done, they have taken

the area as they found it.” App. 79. Although plaintiffs then

produced evidence to meet the trial judge’s major premise (and

other evidence to show how the Board also intentionally ad

vantaged itself of the explicitly dual public housing administra

tion), the district court’s only findings concerning the hotly-dis

puted segregative interrelationships between the school and public

housing authorities are contained in these words (Pet. App.

147a-48a) :

In the 1940’s public housing was strictly segregated according

to race. (T .R .l 182-186). This segregated housing pattern

[public and private] has had a concomitant impact upon the

composition of the Dayton public schools (T.R.2-380, 382-

Robert Rice).

The trial court made no findings concerning the Board’s conduct

in relation to public housing. In contrast, the court of appeals

found from the uncontroverted evidence that the school authorities

“operated one race classrooms in officially one race housing pro

jects which the district court found were ‘strictly segregated

according to race,’ ” Pet. App. 201a and n.35.

21

school (App. 260-Ex. (PX 161 B )), and a later overflow to

the all-black Willard school, rather than other schools that

were equally close (App. 92), while transferring white

students from the white Parkside public housing project

to the McGuffey and Webster schools and the eighth

grades from those schools to the virtually all-white Kiser

school. App. 260-Ex. (PX 161B). Finally, in the late 1940’s

and early 1950’s, the Board leased space in white and black

public housing projects for classroom purposes, and as

signed students and teachers on a uniracial basis to the

leased space so as to mirror the racial composition of the

public housing projects. App. 82-83, 223-33-Ex. (PX 143 J).

By the 1951-52 school year (the last year prior to 1963-

64 for which enrollment data by race are available), there

were 35,000 pupils enrolled in the Dayton district, 19%

of whom were black. There were four all-black schools,

officially designated as such, on the west side of Dayton:

Willard, Wogaman, Garfield and Dunbar. These schools

had all-black faculties and (with one exception, an assign

ment made that school year) no black teachers taught in

any other schools. App. 10-Ex. (PX 3). In addition, there

were 22 white schools with all-white faculties and all-white

student bodies. And there was an additional set of 23 so-

called “mixed” schools, 7 of which had less than 10 black

pupils and only 11 of which had black pupil populations

greater than 10% (ranging from 16% to 68%). App. 216-

Ex. (PX 100E). The schools with any racial mix, however,

were also marked by patterns of racially segregative and

discriminatory practices within the schools, and, with the

one exception noted above, none had any black teachers.

Eighty-three percent of all white pupils attended schools

that were 90% or more white in their pupil racial composi

tion. Of the 6,628 black pupils in the system, 3,602 (or

54%) attended the four all-black schools with all-black

22

staffs; and another 1,227 (or 19%) of the system’s black

pupils were assigned to the adjacent schools which were

about to be converted into “black” schools (see pp. 25-27,

infra). Thus, 73% of all black students attended schools

already or soon to be designated “black.” App. 2-Ex. (PX

2B), 216-Ex. (PX 100E).8

8 The District Court’s Opinion (Pet. App. 147a-49a, 151a-52a,

153a, 158a-59a, 169a-71a). Virtually all of the subsidiary facts

set forth to this point in this section are not in dispute. Many of

them are the subject of findings by the district court (although

they are peppered throughout its opinion as though they were

each unrelated to the other) and while others (e.g., the Reese litiga

tion, the conversion of Garfield, Willard and Wogaman into

blacks-only schools, and the specifics of the Board’s entanglement

with public housing discrimination) were ignored by the district

court, the court’s opinion does not conflict with these undisputed

facts. Thus, the district court finds that “public housing was

strictly segregated according to race” (Pet. App. 147a-48a) (cf.

note 7, supra) ; that the Board segregated many black children

and discriminated against the few others who attended predom

inantly white schools in accordance with “an inexcusable history

of mistreatment of black students” (Pet. App. 149a) ; that “until

1951 the Board’s policy of hiring and assigning faculty was

purposefully segregative” (Pet. App. 153); that the discriminatory

transfer of black children from Shawen Acres Orphanage to the

blacks-only Garfield school was “arguably. . . a purposeful segre

gative act” (Pet. App. 159a); and that “ the first Dunbar High

School was intended to be and was in fact a black high school.”

Pet. App. 170a. The district court, however, refused to determine

whether these “incidents of purposeful segregation” amounted to

a systemwide policy of intentional segregation or otherwise

rendered the system dual at any time.

The Court of Appeals’ Opinion (Pet. App. 195a-96a, 197a, 198a-

201a, 203a). The court of appeals made extensive specific findings

substantially in accord with the subsidiary facts heretofore

described in text. In only two instances did the court of appeals

find it necessary to question a subsidiary district court finding.

First, with respect to the trial court’s statement that the policy

of assigning the black Shawen Acres Orphanage children to the

blacks-only schools rather than to nearby white schools was

“ arguably. . . a purposeful segregative act” (Pet. App. 159a), the

court of appeals concluded that “ [t]o the extent that this finding

implies that this practice was not purposefully segregative, it

is clearly erroneous.” Pet. App. 199a (emphasis in original.)

23

In 1951 and 1952 the Dayton Board confronted its last

pre-Brown opportunities to correct the officially-imposed

school segregation then extant. Instead, the Board acted

in a manner that literally cemented in the dual system and

promised racially discriminatory public schooling for gen

erations to come. What the Board did involved a series of

interlocking segregative maneuvers, which substantially

expanded the separation of black from white children and

staff, primarily through implementation of a new and overt

faculty segregation policy, the use of “ optional attendance

zones,” and the construction of an additional all-black

school.

Prior to this time, as previously noted, the Board would

not allow black teachers to teach white children under any

circumstances (App. 186); black teachers were assigned

only to all-black schools, and white teachers were assigned

only to white and “mixed” schools. In the 1951-52 school

year, in purported response to black community pressure,

the Board announced a “new,” but equally demeaning,

faculty segregation policy (App. 182-Ex. (PX 21)):

Second, the court of appeals credited the Board’s admissions and

the uncontradicted documentary and testimonial evidence showing

that the Board “ pursued an overt policy of faculty segregation. . . .

Defendants admitted that prior to 1951 the board forbade the

assignment of black teachers to white or mixed classrooms ‘pursuant,

to an explicit segregation policy.’ ” Pet. App. 195a and n .ll. In

contrast, the trial court made the clearly erroneous finding that

“ [tjhere is no direct evidence that black teachers were forbidden

to teach white children at any school.” Pet. App. 151a. Although

the Sixth Circuit also supplemented the findings concerning many

significant facts (virtually all of them uncontradicted) which had

been ignored by the trial court, these two are the only instances

relating to the 1912-1952 period in which the appellate court

arrived at a subsidiary factual conclusion which was in conflict

with a district court finding. The court of appeals, however, also

inquired whether this pattern of intentionally segregative conduct

amounted to an official Board policy of segregation and rendered

the Dayton system dual. See notes 9, 11 and 13, infra, and 4, 5 and

7, supra.

24

The school administration will make every effort to

introduce some white teachers in schools in negro [sic]

areas that are now staffed by negroes [sic], but it will

not attempt to force white teachers, against their will,

into these positions.

The administration will continue to introduce negro

'[sic] teachers, gradually, into schools having mixed or

white populations when there is evidence that such com

munities are ready to accept negro [sic] teachers.

This faculty policy, incredibly, was contained in a statement

of the Superintendent disavowing the existence of segre

gated schools in the Dayton district.

In 1954 the Superintendent made a further “integration

statement,” which included the following (App. 184-Ex. (PX

28)):

About two years ago we announced a policy of at

tempting to introduce white teachers in our schools

having negro [sic] population. We have not been too

successful in this regard and at the present time have

only 8 full or part-time teachers in these situations.

There is a reluctance on the part of white teachers to

accept assignments in westside schools and up to the

present time we have not attempted to use any pressure

to force teachers to accept such assignments. The

problem of introducing white teaehers in negro [sic]

schools is more difficult than the problem of introducing

negro [sic] teachers into white situations. There are

several all-white schools which in the near future will

be ready to receive a negro [sic] teacher.

As will be seen (see pp. 32-37, infra), this express faculty

segregation policy continued for almost two more decades

25

as a primary device for identifying schools as intended for

blacks or whites.9

In the school year following the announcement of the

“new” faculty segregation policy, the Board remained under

pressure, as its records reflect, from “ [t]he resistance of

some parents to sending their children to school in their dis

trict because it is an all negro [sic] school.” App. 209-Ex.

(PX 75). In response, the Board constructed a new all

black school (Miami Chapel) located near the all-black

W ogam an school and adjacent to the black DeSoto Bass

public housing project; Miami Chapel opened in 1953 with

9 The District Court’s Opinion (Pet. App. 151a-53a). The district

court correctly concluded that “until 1951 the Board’s policy of

hiring and assigning faculty was purposefully segregative.” Pet.

App. 153a. But the court attempts to ameliorate the harsh racism

of the 1951-52 policy change by characterizing it as a “policy of

dynamic gradualism” (id.) which “was substantially implemented

during the 1950’s and 1960’s.” Id. at 152a. The policy itself,

quoted above, speaks louder and clearer than the district court’s

ameliorative efforts, which are clearly erroneous. The court also

erred in not recognizing the Board’s faculty policies as the hall

mark of the Dayton-style dual system. (The court’s continuing

errors, with respect to post-Brown faculty-assignment practices,

are treated at pp. 36-37, infra.)

The Court of Appeals’ Opinion (Pet. App. 195a-96a, 197a, 202a-

03a). The Sixth Circuit characterized the Board’s faculty-assign

ment policy as “ an overt policy of faculty segregation” (Pet. App.

195a), “an explicit segregation policy” (id.), “ purposeful segrega

tion of faculty by race” (id. at 197a), and “deliberate policy of

faculty segregation.” Id. at 202a-03a. And “contrary to the find

ing of the district court, . . . the Board ‘effectively continued in

practice the racial assignment of faculty through the 1970-71

school year.’ To the extent that the finding of the district court

is contrary to the conclusion of this court, it is clearly erroneous.”

Id. at 196a. Moreover, the court of appeals recognized and held

that the discriminatory faculty-assignment policy “was inextric

ably tied to racially motivated student assignment practices” (id.

at 197a; see also id. at 211a), and that the district court erred in

failing to attribute any legal significance to the faculty policy

“which, at the time of Brown I , made it possible to identify a

‘black school’ in the Dayton system without reference to the racial

composition of pupils.” Id. at 203a.

26

an all-black student body and an 85% black faculty. App.

11-Ex. (PX 4). The Board altered attendance boundaries

so that some of the children in the four blacks-only schools

were reassigned to the four surrounding schools with the

next highest black pupil populations; and, through either

attendance boundary alterations or the creation of optional

zones, it reassigned white students from these mixed

schools to the next ring of whiter schools. R.I. 1456 ; App.

274-75, 283-92, 345-46; PX 123.

Thus, the boundaries of the black Garfield and Wogaman

schools were retracted, thereby assigning substantial num

bers of black children to the immediately adjacent ring of

“mixed” schools with the highest percentage of black pupils:

Jackson (already 36% black in the 1951-52 school year),

Weaver (68% black), Edison (43% black) and Irving (47%

black). App. 216-Ex. (PX 100E). As Jackson and Edison

were re-zoned to include more black students, their outer

boundaries were simultaneously contracted through the

creation of “optional zones” (Jackson/Westwood and Edi

son/Jefferson) so that white residential areas were effec

tively detached from Jackson and Edison and, for all prac

tical purposes, attached to the next adjacent ring of “whiter”

schools. Thus, the Board brought blacks in one end and

allowed whites to escape out the other in these “transition”

schools. The Board also created optional zones (Willard/

Irving, Willard/Whittier and Wogaman/Highview, as well

as an option between the new Miami Chapel and Whittier)

in white residential areas contained within the boundaries

of the original schools for blacks only, so that whites could

continue to transfer out of these all-black schools. R.I. 1456;

App. 274-75, 283-92. (Prior to 1952 whites had been freely

allowed to transfer to “whiter” schools, but such transfers

were abolished in 1952. App. 288, 183-Ex. (PX 28).) Op

tional zones were thus substituted for the prior segregative

27

free-transfer practice10 to continue the Board’s policy of

protecting whites from associating on an equal basis with

black students and staff.

During this period the Board also created another op

tional attendance zone affecting Jackson; this zone was in

stituted in an area of the Jackson zone containing the Veter

an’s Administration Hospital, and allowed whites to attend

Residence Park, which at that time was all-white. App.

271-73, 216-Ex. (PX 100E). (This option is discussed

further at p. 47, infra.) Additionally, the Board during

this period created an optional zone between Roosevelt

(31.5% black) and Colonel White (100% white). App. 275-

76, 216-Ex. (PX 100E). The immediate and long-range

racial significance of this option are discussed in greater de

tail at pp. 45-46, infra.

Finally, the Board began to transfer black teachers to the

formerly “mixed” schools in transition (but none to the

all-white schools) thereby confirming their identification as

schools for blacks rather than whites in the traditional fash

ion. App. 286, 6-10-Ex. (PX 3).11

10 The Superintendent’s 1954 statement ( see p. 24, supra)

included the following: “All elementary schools have definite

boundaries and children are obliged to attend the school which

serves the area in which they reside. The policy of transfers from

one school to another was abolished two years ago when the

boundaries of several westside elementary schools were shrunken,

permitting a larger number of Negro children to attend mixed

schools.” App. 183-Ex. (P X 28). Thus, the purpose of free

transfers was accomplished by a new device, optional zones, which

served the same end of allowing whites to avoid attendance at

black or substantially black schools.

11 The District Court’s Opinion (Pet. App. 155a-57a). Incredibly,

the district court concluded that the West Side reorganization

“was an experiment in integration” and, inconsistently, that “ [i]ts

purpose was to enable black students to go to an integrated rather

than an all-black school if they chose to do so.” Pet. App. 155a.

These conclusions are clearly erroneous, arrived at only through

2 8

the most selective and argumentative reading of the record imagin

able. For example, the district court cites the testimony from the

latest hearing of former Superintendent Wayne Carle in support

of the proposition that the West Side reorganization was an

“experiment in integration.” While Dr. Carle’s testimony is not

absolutely free of ambiguity (because of his understanding that

another superintendent in 1952 and 1954 characterized it as an

“experiment in integration” in response to the black community’s

continuing protest of school segregation (App. 468-70)), taken as

a whole it is impossible to characterize his views as being that the

events of 1952 were integration-oriented. But the district court

selectively relies on five pages of the transcript (App. 468-70) and

ignores altogether the very next two pages (App. 471) in which

Dr. Carle placed his view in context by emphasizing that “you

can’t operate part of the system on a segregated basis without

signalling that the rest of the system is on a segregated basis”

(App. 471); “ The action that was taken there was that nothing

was done to eliminate the segregation that already existed in the

three schools whose boundaries were changed” (id.) ; and that if

the Board had truly adopted a policy of real desegregation and

“that were communicated to the community, I suspect it might

have a much different effect than minor boundary changes in

volving schools that remain all black” (App. 472).

These points are unassailable, but by ignoring them the district

court had just begun to err. These basic errors were compounded

three-fold: First, the court ignored further testimony from Dr.

Carle pointing out that a central part of the West-Side reorganiza