Motion for the Ameerican Civil Liberties Union Amicus Curiae to Allow Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

January 11, 1972

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Motion for the Ameerican Civil Liberties Union Amicus Curiae to Allow Oral Argument, 1972. a2ab7831-b325-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2f850e0d-3a6f-4284-973f-6cf553a8141e/motion-for-the-ameerican-civil-liberties-union-amicus-curiae-to-allow-oral-argument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

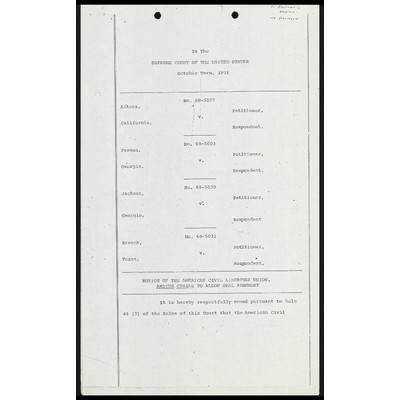

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

Aikens, <

Petitioner,

California,

Respondent.

No. 69-5003

Furman,

: Petitioner,

< Vv .

Georgia,

Respondent.

No. 69-5030

Jackson, es

Petitioner,

Vv’

Georgia,

Respondent

“No. 69-5031

Branch,

Petitioner,

Vv.

Texas, yf »

Resgpondent.

MOTION OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AMICUS CURIAE TO ALLOW ORAL ARGUMENT

It is hereby respectfully moved pursuant to Rule

44 (7) of the Rules of this Court that the American Civil

Liberties Union, amicus curiae through its attorney Gerald H.

Gottlieb, be afforded t! 2 opportunity to present oral argument

in the above cases. In support of this application, movant

would respectfully show the following.

1. - The brief of the American Civil Liberties

Union, amicus curiae was duly filed by order of the Court on

: x

October 12, 1971.

2. The hletouic ifportance of these cases, which

challonas the imposition of the death penalty as offensive to

the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, cannot be overstated.

This Court's resolution of these issues will affect not only

the lives of hundreds of condemned men but also the cuality of

criminal justice in our society.

3, ‘Gerald HH. Gottlieb, Esq. of California, the

wg they Of the American Civil Libe. ties Union brief.

and the attorney who would present the argument for amicus

curiae if this motion is granted, has devcted much of his time

for over a decade to the study of capital punishment. In a

1961 law review article he proposed the thesis that the death

penalty was unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment, the

very issue which is before the Court. See Gottlieb, Testing

the Death Penalty, 34 So. Cal. IL. ROY. 268 (1961). Since then

he has assiduously gathered relevant factual and legal data and

conferred with experts from the fields of psychiatry, PavoloaT

and sociology concerning these issues, particularly with regard

to the Corrs re hot Of & ie oi death upon those who

face it. These investigations culminated im a 1967 monograph

entitled "On capital Punishment, " a systematic survey of the

issues, Since then, Mr. Gottlieb has participated, at both the

trial and appellate level, in California cases challenging the

death penalty. See Appendix A to the Brief of the American

Civil Liberties Union in these cases. In short, Mr. GotELieh sy

expertise with regard to the sensitive {sues before the Court

is profound. :

4, SecRnte ot his yvears of study addressed precise-

ly to the issues in this case, Mr. Gottlieb is in a singularly

unique position be assist the court and to respond to the

Court's inquiries.

WHEREFORE, amicus curiae respectfully requests

[3

that the Court grant this motion and allow oral argument to be

presented by Gerald H. Gottlieb on behalf of the American Civil

Liberties Union.

Respectfully submitted,

SLAY) eee —

Melvin IL. Wulf

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, New Tork 10010

January 11, 1972 | Hy . Attorney for Movant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

1 here certify that on this 11th day of January,

1972, copies of this motion were mailed, postage prepaid, to

Jack Greenberg, Esg., Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle, New York,

‘ *4

New York, 10019; Anthony C. Amsterdam, Esq., Stanford Law School,

Stanford, California 94305 ; Honorable Ronald George, Asst.,

Attorney General of california, 600 State Building, Los Angeles,

California 80042; Mrs. Elizabeth DuBois, Esqg., Suite 2030,

10 coluiohs circle, New York, New York 10019; Mrs. Dorothy T.

seasiey, Asst. Attorney General of Georgia, 132 State Judicial

Building, 40 capitol Square, Atlanta, Genrgia 30334; Michael

Melisner, Esg., Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New

York 10019: Melvyn Carson Bruder, Esq., Suite 300, Lawyers .

Building, Dallas, Texas 50004 Cinriag Alan Wright, ESq.,

University of Seung at Austin, School of Law, 2500 Red River,

Austin, Texas 75202; Hilbert P. Zarky, Esq., 1800 Century Park

East, Los AdiZoles. california 90007; Chauncey Eskridge, Esdqg.,

Suite 1500, 110 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603;

1.20 Pfeffer, BEag., 15 East B4th aLveet; New York, New York

10028, attorneys for the respondents. I further certify that

all parties required to be served have been served.

:

Al AA . , | ! oa

Melvin L. Wulf

i

°