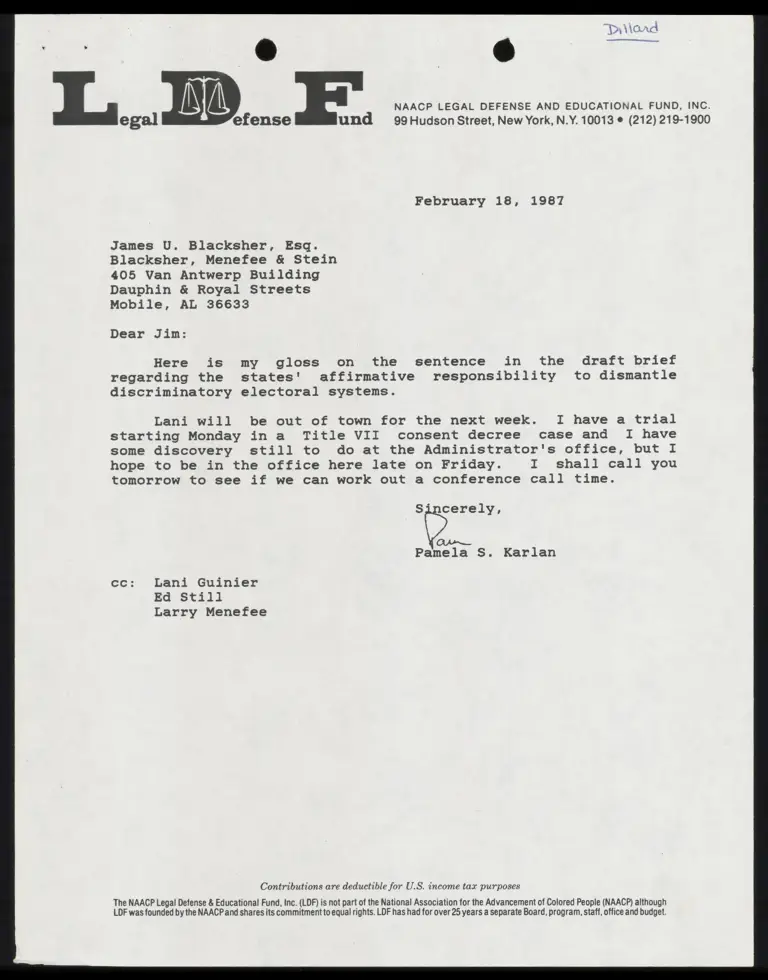

Correspondence from Karlan to Blacksher; Draft Brief Re Discriminatory Electoral Systems

Working File

February 18, 1987

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence from Karlan to Blacksher; Draft Brief Re Discriminatory Electoral Systems, 1987. f9fcc6c0-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2fe691c3-a154-451c-a607-b49722b265f3/correspondence-from-karlan-to-blacksher-draft-brief-re-discriminatory-electoral-systems. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

illand

re » ——————

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

efense und 99Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013 ® (212) 219-1900

egal

February 18, 1987

James U. Blacksher, Esq.

Blacksher, Menefee & Stein

405 Van Antwerp Building

Dauphin & Royal Streets

Mobile, AL 36633

Dear Jim:

Here is my gloss on the sentence in the draft brief

regarding the states' affirmative responsibility to dismantle

discriminatory electoral systems.

Lani will be out of town for the next week. I have a trial

starting Monday in a Title VII consent decree case and I have

some discovery still to do at the Administrator's office, but I

hope to be in the office here late on Friday. I shall call you

tomorrow to see if we can work out a conference call time.

Sincerely,

CU ~—

Pamela S. Karlan

cc: Lani Guinier

Ed Still

Larry Menefee

Contributions are deductible for U.S. income tax purposes

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) although

LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 25 years a separate Board, program, staff, office and budget.

The State Is Ultimately Responsible for Remedying

the Continuing Effects in Each of its Subdivisions

of Laws That Violate the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act was intended to remedy a "century of

obstruction" and "to counter the perpetuation of 95 years of

pervasive voting discrimination," City of Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156, 182 (1980), by "creat[ing] a set of mechanisms for

dealing with continued voting discrimination, not step by step,

but comprehensively and finally." S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 5

(1982). Sections 4 and 5, which suspend the use of tests and

devices and require that covered jurisdictions seek preclearance

of electoral changes, form the "heart of the Act," because they

"shift the advantage of time and inertia from the perpetrators of

the evil to its victims," South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.

301, 315 & 328 (1966). Thus, §§ 4 and 5 constitute, along with §

2, a concerted plan of attack on practices, standards, and

devices that discriminate against minority voters. Cf. S. Rep.

No. 97-417, pp. 5-6 (1982),

Section 2 of the Act contains a broad prohibition of "the

use of voting rules to abridge exercise of the franchise." South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 301. The legislative history

of the 1982 amendment of § 4 shows that Congress intended to make

states affirmatively responsible for dismantling discriminatory

electoral systems within their territories. Thus, a state's

continued acquiescence in its subdivisions' use of voting systems

that result in the dilution of minority voting strength violates

§ 2.

Originally, coverage under the special provisions of §§ 4

and 5 of the Act was triggered by a finding that the state or |

separately covered subdivision had used a test or device as a 1

prerequisite to registration or voting and had a history of

depressed political participation. § 4(b). The triggering

mechanism was designed to identify and target those jurisdictions

which had historically discriminated on the basis of race in

restricting the franchise. A covered jurisdiction could "bail

out," or free itself from the Act's special remedies, by showing ;

that, for a specified period of time, it had not used the test or

device with the purpose or effect of denying or abridging the

right to vote on account of race. § 4(a).

In 1982, Congress found a continuing need for the special

remedies provided by §§ 4 and 5. Preclearance remained necessary

for some jurisdictions both "because there are 'vestiges of

discrimination present in theis electoral system and because no

constructive steps have been taken to alter that fact.'" H.R.

Rep. No. 97-227, p. 37 (1982). Thus, Congress amended the

bailout provision to ensure that jurisdictions would not be

released from the special remedial provisions of the Act merely

because of the passage of time.l In place of the existing

bailout provision, which imposed on covered jurisdictions only a

E

.

G

passive obligation not to use tests or devices that had the

lThe existing bailout formula permitted covered

jurisdictions to bail out by showing that they had not used a

test or device in a discriminatory manner in the preceding 17

vears. Since § 4 had suspended the use of tests and devices in

the originally covered jurisdictions on August 6, 1965, such

jurisdictions would automatically come out from under §§ 4 and 5

on August 6, 1982. See S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 43, n. 162 (1982).

2

purpose or effect of denying minorities the right to vote,

Congress substituted a bailout formula that imposed on covered

jurisdictions an affirmative responsibility to ensure minorities

the right to vote and to have their votes count. It hoped that

"a carefully drafted amendment to the bailout provision could

indeed act as an incentive to jurisdictions to take steps to

permanently involve minorities within their political process

..." H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 37 (1982); see also id. at 32; S.

Rep. No. 97-417, p. 2 (1982) (new bailout provision requires a

showing that jurisdiction has "taken positive steps to increase

the opportunity for full minority participation in the political

process, including the removal of any discriminatory barriers");

id. at 43-44.

The new bailout formula, which took effect on August 5,

1984, provides, in pertinent part, that the declaratory judgment

releasing a jurisdiction from the requirements of §§ 4 and 5

"shall issue only if [the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia] determines that during

the ten years preceding the filing of the action, and

during the pendency of such action--

(F) such State or political subdivision and all

governmental units within its territory--

(i) have eliminated voting procedures

and methods of election which inhibit or

dilute equal access to the electoral process;

(ii) have engaged in constructive

efforts to eliminate intimidation and

harassment of persons exercising rights

protected under this Act; and

(iii) have engaged in other constructive

efforts, such as expanded opportunity for

convenient registration and voting for every

person of voting age and the appointment of

minority persons as election officials

throughout the jurisdiction and at all stage

3

of the election and registration process."

(emphasis added). The legislative history of this new bailout

provision shows that Congress intended to impose on covered

states an affirmative responsibility to police the electoral

behavior of their political subdivisions and to remedy the

continuing effects in each of its subdivisions of state laws

adopted with the purpose or having the effect of denying citizens

the right to vote on account of race.

The most detailed discussion of the states' special

responsibilities under the Act occurred in the context of a floor

debate in the House concerning a proposed amendment to § 4 that

would have permitted states to bail out even if not all their

political subdivisions met all the criteria for bailout. The

House rejected that amendment overwhelmingly. Representatives

who spoke in opposition to the proposed amendment stressed both

the special constitutional role of states in protecting the right

to vote and the extent of states' control over their

subdivisions' electoral systems. See, e.g., 127 Cong. Rec. H6969

(daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981) (Rep. Sensenbrenner) (states have broad

control over subdivisions and ample authority to make them obey

the Act); id. at H6970 (Rep. Fish) (noting that states "are

mentioned specifically in the language of the 15th amendment” and

"have an important fundamental power with regard to the

franchise. I think, along with that authority goes the

responsibility of States to protect the right to vote"); id.

(Rep. Frank) (same); id. at H6971 (Rep. Chisholm) (states "have a

constitutional and a moral responsibility to insure that the

local governmental units under their jurisdiction meet the

standards of the act").

Of particular salience to this case, several representatives

pointed to Alabama legislation to support their contention that

states must be made responsible for the compliance of their

subdivisions. Representative Washington relied on Alabama's

local reregistration statutes to illustrate the danger of

relieving states of the obligation of assuring compliance with

the Act by their subdivisions:

"[I]t will be very difficult to determine when a

violation flowed from a county provision in the first

instance, from a provision of state law, or as a

consequence of a county's interpretation or

administration of a State law of general applicability.

And throughout all of this would remain the issue of

whether the State knew or should have known that it was

legislatively acquiescing to a county practice that

violated the act."

127 Cong. Rec. H6968 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981). Moreover,

Representative Washington's explanation of the way in which

states historically acted to restrict the franchise mirrors this

Court's description of Alabama's intentional manipulation of

county commission elections. Compare Dillard v. Crenshaw County,

640 F. Supp. 1347, 1356-59 (M.D. Ala. 1986) with 127 Cong. Rec.

H6968 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981) ("there is a tradition of the

State legislature overruling or preempting other jurisdictions in

these matters. Remember it was the Stae [sic] legislatures which

called constitutional conventions to disenfranchise blacks.").

Representative Sensenbrenner also used Alabama's local laws as an

example to support his assertion that states have broad control

over subdivisions and ample authority to make them obey the Act.

Id. at H6969. In light of this debate, the House Report

expressly stated that the new bailout formula "retain([s] the

concept that the greater governmental entity is responsible for

the actions of the units of government within its territory, so

that the State is barred from bailout unless all its

counties/parishes can also meet the bailout standard ...." H.R.

Rep. No. 97-227, p. 33 (1982).

The Senate Report, which the Supreme Court has characterized

as an "authoritative source" for determining Congress' purpose in

enacting the 1982 amendments,. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. ’

92 L.Ed.2d4 25, 42 n. 7 (1986), took the same approach. "it is

appropriate to condition the right of a state to bail out on the

compliance of all its political subdivisions, both because of the

significant statutory and practical control which a state has

over them and because the Fifteenth Amendment places

responsibility on the states for protecting voting rights." 8S.

Rep. No. 97-417, p. 56 (1982). In particular, the Report noted

that "States have historically been treated as the responsible

unit of government for protecting the franchise," id. at 57,

because "the Fifteenth Amendment places responsibility on the

states for protecting voting rights," id. at 69. Since state

laws govern local electoral practices, the states ultimately are

responsible for ensuring that none of their subdivisions deny

minorities the right to vote. Id. at 57.

In sum, the 1982 amendments of § 4, the centerpiece of the

Act's special protections, were intended to place upon states an

affirmative obligation to dismantle still-existing barriers to

minority political participation. A state's failure to undertake

this duty should not only result in its continued coverage under

§ 5 but should also be viewed as a violation of § 2, which

prohibits the states from imposing or applying any voting

standard practice or procedure which results in the denial or

abridgment of the right to vote. As the 1982 House Report made

clear:

"Under the Voting Rights Act, whether a discriminatory

practice or procedure is of recent origin affects only

the mechanism that triggers relief, i.e., litigation

[under section 2] or preclearance [under section 5].

The lawfulness of such a practice should not vary

depending on when it was adopted, i.e., whether it is a

change.

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 28 (1982). The failure of Alabama to

dismantle its discriminatory electoral system represents a

continuing violation of the Voting Rights Act and the Fifteenth

Amendment.