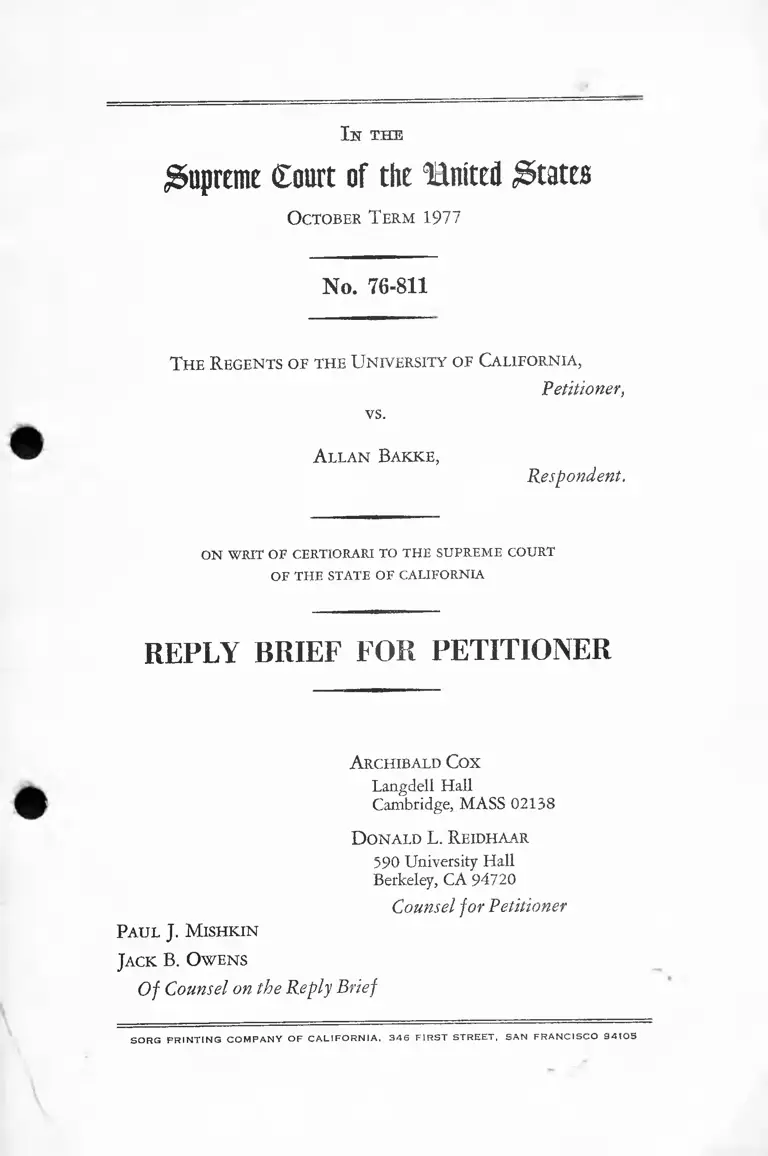

Bakke v. Regents Reply Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Reply Brief for Petitioner, 1977. 5606c147-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2fef03a2-71ab-4c7d-a671-27a0dba8fe26/bakke-v-regents-reply-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

I s THE

Supreme Court of the BnM States

O c t o b e r T e r m 1977

N o. 76-811

T h e R e g e n t s o f t h e U n iv e r sit y o f C a l if o r n ia ,

Petitioner,

vs.

A l l a n B a k k e ,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

A r c h ib a ld C o x

Langdell Hall

Cambridge, MASS 02138

D o n a l d L . R eid h a a r

590 University Hall

Berkeley, CA 94720

Counsel for Petitioner

Pa u l J . M is h k in

J a c k B . O w e n s

Of Counsel on the Reply Brief

S O R G P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y O F C A L I F O R N I A , 3 4 6 F I R S T S T R E E T , S A N F R A N C I S C O 9 4 1 0 5

SUBJECT INDEX

I. The Central Issue Unavoidably Presented by This Case

Is Not the Permissibility of Choosing a Particular Num

ber for an Admissions Program as a Means of Allocat

ing Educational Resources But Whether the Equal

Protection Clause Forbids a State Professional School,

by Whatever Measure It Finds Suitable, to Take Ac

count of Race in Admissions to Remedy the Effects

of Persistent and Pervasive Discrimination Against

Racial Minorities ........... ........ ........... .................. .............. 2

A. It Is Unfair and Misleading to State That the

Medical School Program Admits "Less Qualified’’

in Place of "Better Qualified’’ Applicants---------- 3

B. It Is Unfair and Misleading to Label the Medical

School Program a "Quota.” The Choice of a Par

ticular Numerical Target to Define the Scope of

the Program Has No Constitutional Significance.— 5

C. Respondent Was Not Denied Admission "Solely

Because of His Race” ................... -.......-.............. ...... 8

II. The Equal Protection Clause Does Not Bar a State from

Voluntarily Adopting and Implementing in Its Admis

sions Practices a Policy of Increasing the Number of

Medical Students and Doctors Who Are Fully Qualified

for Admission and Who Come from Minority Groups

Long Victimized by Pervasive Racial Discrimination .... 8

A. The Equal Protection Clause Permits Race-Con

scious State Action Which Is Neither Hostile Nor

Invidious and Which Is Closely Tailored to

Achieving a Major Public Objective........................ 8

ii S u b j e c t In d e x

Page

III. The Educational and Social Purposes to Which the

Policy Is Tailored Amply Justify Consciously Increas

ing the Number of Qualified Applicants Chosen from

Minority Groups _____ ________ _________________ 12

IV. Voluntary Minority Admissions Programs Raise D if

ferent Constitutional Issues from Mandatory Affirma

tive Action Programs of Minority Employment........... 13

V. The Case Should Not Be Remanded for the Findings

Suggested by the United States_______ _____________ 15

Conclusion ................................................................... ................. 20

CITATIONS

Ca se s P ages

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 97 S.Ct. 2691 (1977)— ...... 19-20

Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S. 341 (1976)_________________ 18-19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S, 483 (1954) -------- 20

Califano v. Webster, 97 S.Ct. 1192 (1977)------------------ 9

Grayson v. Harris, 267 U.S. 352 (1925)---------------------- 3

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969)—------------------ H

Lau v. Nichols, 4 l4 U.S. 563 (1974)------------------------ 9

Meachum v. Fano, 427 U.S. 215 (1976). _____________ 19

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974).___________ __ 9

Pashall v. Christie-Stewart, Inc., 4 l4 U.S. 100 (1973)----- 3

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976)------------------------- 18

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1

(1973) __________— - ___________ ______________ 20

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)______________________ 9, 15, 18

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144

(1938) --------- ------- --------------------------------- -- - 11

C o n s t it u t io n s

United States Constitution

Fourteenth Amendment _____________ ______—6, 7, 8, 17, 20

California Constitution

Article I, section 21 (Now Article I, section 7 ( b ) ) ----- 3

M is c e l l a n e o u s

Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Discrimination, 41

U.Chi.L.Rev. 723 (1974) 11

I n t h e

Supreme Court of tfje Umteb is>tat££

O c t o b e r T er m 1977

N o. 76-811

T h e R e g e n t s o f t h e U n iv e r sit y o f C a l if o r n ia ,

'Petitioner,

vs.

A l l a n B a k k e ,

Respondent.

ON WRIT O F CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

2

I .

THE CENTRAL ISSUE UNAVOIDABLY PRESENTED BY THIS CASE

IS NOT THE PERMISSIBILITY OF CHOOSING A PARTICU

LAR NUMBER FOR AN ADMISSIONS PROGRAM AS A

MEANS OF ALLOCATING EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES BUT

WHETHER THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE FORBIDS A

STATE PROFESSIONAL SCHOOL, BY WHATEVER MEASURE

IT FINDS SUITABLE, TO TAKE ACCOUNT OF RACE SN

ADMISSIONS TO REMEDY THE EFFECTS OF PERSISTENT

AND PERVASIVE DISCRIMINATION AGAINST RACIAL

MINORITIES.

The selection of approximately 16 qualified applicants for each

entering class at Davis through the Task Force program from the

black, chicano, Asian or American Indian minority flows from a

decision to devote a larger portion of the University’s finite re

sources to educating a greater number of qualified persons of

disadvantaged backgrounds and minority race. No one denies that

blacks, chicanos, Asians and American Indians have been isolated

from the mainstream of American life by generations of racial dis

crimination and disadvantage, de jure and de facto. No one denies

that they have lacked equal access to higher education and the

learned professions. The aim of the minority admissions program

at Davis is to reduce that isolation; to demonstrate to boys and

girls in the barrio and ghetto that the historic barriers to their

entering the medical profession have been eliminated; to improve

both medical education and the medical profession by increasing

the diversity of both the student body and the medical profession;

and to improve medical care in the underserved minority com

munities. Accordingly, we share the view of the United States

that this case presents one— and only one—inescapable question:

"whether a state university admissions program may take race into

account to remedy the effects of societal discrimination’’ (Brief

for United States at 23).

We restate the issue which the Court cannot avoid because the

Brief for Respondent and many of the supporting briefs of amici

curiae attempt to hide it under misleading labels and inaccurate

3

generalizations. We address these sources of confusion first, and

then turn to the real issue.1

A. It Is Unfair and Misleading to State That the Medical School

Program Admits "Less Qualified" in Place of "Better Quali

fied" Applicants.

It is accurate to say that a minority admissions program results

in selecting for admission from among many fully-qualified candi

dates some fully-qualified minority applicants who would not have

been chosen under earlier color-blind criteria of selection.

The vice of the general labels, "better qualified” and "less

qualified,” is that they confuse qualification for medical education

and the profession with selection for admission from among the

fully-qualified applicants, and then they go on to assume, contrary

to fact, that there is some abstract and universal measure of who

is "better qualified” for all purposes.

Everyone admitted to Davis is fully qualified for medical educa

tion. There has been no compromise of the basic aim of medical

education to produce intelligent, highly skilled and well-trained

doctors with the commitment and human qualities most valuable

1. The jurisdictional doubt expressed in the Brief for the Lawyers

Committee for Civil Rights Under Law at 6 n.2 results from misreading

the record. In Paschall v. Christie-Stewart, Inc., 414 U.S. 100 (1973)

the Court vacated and remanded because:

f l ] t now appears that there might have been an independent and,

possibly an unchallenged ground for the judgment of the state trial

court, viz., the running of the Oklahoma period of limitation for

adverse claims (Id. at 101 (emphasis added) ) .

In that event, in Paschall, the appellant could take nothing from even a

favorable decision of the federal question. His failure to challenge the

trial court’s alternate state ground for decision would bar the State

Supreme Court from considering it, and therefore the trial court’s judg

ment would in any event be affirmed.

The present case is different. The Lawyers’ Committee is quite wrong in

” saying that "[t}h e judgment of the trial court would be left standing

whatever the disposition of the federal ground.” Here, petitioner did

challenge the trial court’s ruling that the minority admission program

violates the California Constitution, Art. I, § 21 (now Art. I, § 7 (b ) )

(R. 398-399). If this Court reverses the decision below on the federal

question, the issue of state law will remain for decision. Respondent may

seek to retain the judgment upon the non-federal ground, but the existence

of that ground does not defeat jurisdiction where it is open and has not

been considered by the highest state court. Grayson v. Harris, 267 U.S.

352, 358 (1925).

4

in serving humanity. There has been no lowering of the measure

of qualifications for study and the profession. There has been no

compromise of academic standards after admission.

Once the choice is narrowed to those fully qualified for the

study and practice of medicine, as the choice is narrowed at Davis,

then the specific aims of the institution determine the criteria and

particular qualifications for selection for admission.

Selection for admission is not a reward or a prize or the ration

ing of benefits. Selection in some cases may be designed simply

to reduce the rate of academic failure, but selection often also

serves other important educational and social objectives. If the

aim of a medical school is to produce professors for teaching and

research, college grades and Medical College Admission Test

scores may be the best measure of particular qualification. On the

other hand, if a medical school judges that the public will be best

served if it has among its fully-qualified students some who will

best conduct clinics in the barrio, then the chicano applicant who

speaks the language and colloquialisms of the barrio and who

knows its folklore may be better qualified than other applicants

even though they have higher academic ratings. If one purpose

of a medical school is to persuade black students at overwhelm

ingly black junior high schools to realize that by applying them

selves to intellectual activity they too may become doctors, the

black applicant is better qualified than the white, other things

being equal, because personal acquaintance with a black medical

student or a black physician provides young black students with

more convincing evidence of their opportunities than a visit or

any amount of exhortation from a white medical student. To the

extent that the aim is to graduate students who will deliver health

care on an Indian reservation, the American Indian applicant who

grew up on a reservation and gives convincing evidence of his or

her intent to return may reasonably be judged better qualified than

an applicant from a different background.

The minority admissions program flows from a broadened view

of the public needs and therefore of the educational and profes

sional objectives of the Medical School at Davis, but there is noth

ing novel about its taking public needs into account in admitting

5

some parts of a student body. Medical schools have long done this.

For example, the Davis Medical School consistently has treated

growing up in a rural area where health services are inadequate as

a special qualification (R. 64-65).

B. It Is Unfair and Misleading to Label the Medical School Pro

gram a "Quota." The Choice of a Particular Numerical Target

to Define the Scope of the Program Has No Constitutional

Significance.

1. The very use of the slippery word "quota” is unfair and

misleading. Decision must turn upon the operative facts, which

the label hides.

The 16 places assigned to the minority admissions program are

not a ceiling upon the number of minority students in any class.

Minority applicants are considered and accepted under the regular

admission programs without limit of number and without refer

ence to the number admitted under the Task Force program (R.

216-19). The number of minority students in each class has

always been more than 16 (ibid.).

The 16 places are not a guaranteed minimum for minority

admissions. In two of the four years, 1971-1974, only 15 Task

Force students were enrolled (Pet. Br, at 3). No applicant was

admitted under the Task Force program without a decision—by

both the Task Force subcommittee and the full Admissions Com

mittee— that the applicant was fully qualified for medical educa

tion (R. 67, 166-67).

In sum, the only significance of the number 16 is that the Davis

faculty stated for the Admissions Committee a fairly exact measure

of the proportion of its limited educational resources which it

wished to devote to the social and professional purposes served

by increasing the number of medical students and doctors drawn

from the long-victimized minorities, who are thoroughly qualified

to study and practice medicine, but who would lose out in competi

tion for selection under the earlier criteria at a time when there

are more than 30 applicants for every place.

2. The use of a fairly exact measure of the extent of this

commitment has no constitutional significance.

6

Because resources are limited, every medical school is forced

to strike a balance among the functions it would like to perform.

Usually the necessity for allocating resources affects admissions

policies and procedures. If the school wishes to increase the num

ber of general practitioners in rural areas, it may give some prefer

ence in admissions to qualified applicants who come from such

areas and give convincing evidence of an intent to return, even

though they might not be chosen if the sole aim were to emphasize

training for teaching and research. Similarly, a balance must be

struck among competing goals whenever a professional school

decides to make it one of its objectives to promote purposes ad

vanced by increasing the members of a profession drawn from the

minorities long-victimized by racial discrimination.

One way to strike the balance is for the faculty to frame its

determination with some precision, as at Davis, leaving it to the

administrators to come back to the faculty if the conditions under

lying the directive are altered, as when there is marked change in

the pool of applicants. Alternatively, the faculty may strike the

balance in general terms by adjective or range, or it may simply

give approval to the reported practices of the admissions com

mittee. The faculty might even leave the striking of the balance

to the admissions committee to be made in the course of the com

mittee’s ad hoc decisions to admit or deny.

Whether the balance be struck in one way or another has no

constitutional significance. From the beginning the members of

the Admissions Committee must have some idea of the balance

they will strike between the goals supposed to be advanced by

conventional admissions criteria and the goals served by having a

larger number of qualified individuals from minority groups. In

the end, policy must take shape in numbers. The Fourteenth

Amendment neither prescribes the procedure for reducing policy

to numbers nor proscribes one method while permitting others.

The word "quota” as used by respondent and amici supporting

him to condemn the Davis program is simply a pejorative. None

of them would consider valid any race-conscious admissions pro

gram, with or without a numerical objective. The rationale of

every one of their briefs would, if accepted, invalidate any use of

7

minority status as a factor favoring the admission of any student.

3. The arguments focusing on "quota” miss the point for still

another reason.

Even if the Court finds the decision to admit 16 fully qualified

applicants under the Task Force program to violate the Fourteenth

Amendment, the judgment below must be reversed unless the

Court holds that any race-conscious admissions policy, designed to

increase the numbers of minority students and minority members

of the learned professions, is unconstitutional.

The trial court put its decision upon the ground that any race

conscious admissions program is unconstitutional (R. 307). The

judgment, and in particular the declaratory portion, bars the Uni

versity from taking race into account in selecting applicants for

admission (R. 394).

The Supreme Court of California in affirming that judgment

specifically ruled that any race-conscious admissions program is

unconstitutional (Pet. App. at 16a, 25a, 35a). The broad sweep

of the decision as applying to race-conscious special admissions

programs of "educational institutions” generally is made explicit

in the opinion {id. at 38a n.34). In addition, the order for

Bakke’s admission (R. 495) plainly rests upon the holding that

the entire Task Force program is unconstitutional because it treats

race as a relevant concern (Pet. App. at 37a).

The broader national interest also requires decision of the basic

issue. To affirm the judgment below because of a misguided con

cern as to the choice of a particular number to define a resource

allocation, would discourage the governing boards and faculties of

universities everywhere in the United States from pursuing admis

sions programs giving minorities more nearly equal access to

higher education and the learned professions. The adverse opinion

of a prominent state court would be left to stand as a precedent

in California and a persuasive influence in other states. The com

bination of the California court’s ruling and this Court’s silence

would force all governing boards and faculties to reappraise their

minority admissions programs. They would have to pass judgment

in a climate of legal hostility, facing a virtual certainty of litiga-

8

tion. The fundamental issues have now been fully explored. They

require national resolution now, by the only court empowered to

put the uncertainty to rest.

C. Respondent Was Not Denied Admission "Solely Because of

His Race."

Respondent’s brief is filled with simplistic assertions that he

"was excluded from a state operated medical school solely because

of his race” (e.g., Resp. Br. at 2, 22, 26, 63). Respondent failed

to gain admission because there were approximately thirty appli

cants for every place available at Davis and his credentials were

judged not to be strong enough to win him one of the places

available to him. His application was denied for exactly the same

kinds of reasons that the Admissions Committee in making selec

tion decisions denied many other well qualified non-disadvantaged

applicants, whites and minorities (R. 170, 195).

The Task Force program makes race a factor. It can fairly be

said to diminish somewhat the chance an applicant has of gaining

admission if he is not of one of the minority groups because, like

any race-conscious admissions program, it reduces the number of

places available to other applicants. But the program does not take

from anyone a vested right or a certainty of admission. Respondent

had no more right to a medical education than the other 2,300 or

3,600 applicants for whom there was no room. Nor does the pro

gram deny anyone admission solely because of his race.

II.

THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE DOES NOT BAR A STATE

PROM VOLUNTARILY ADOPTING AND IMPLEMENTING IN

ITS ADMISSIONS PRACTICES A POLICY OF INCREASING

THE NUMBER OF MEDICAL STUDENTS AND DOCTORS

WHO ARE FULLY QUALIFIED FOR ADMISSION AND WHO

COME FROM MINORITY GROUPS LONG VICTIMIZED BY

PERVASIVE RACIAL DISCRIMINATION.

A. The Equal Protection Clause Permits Race-Conscious State

Action Which Is Neither Hostile Nor Invidious and Which Is

Closely Tailored f© Achieving a Major Public Objective.

1. The decisions of this Court cited in our opening brief (pp.

61-64) demonstrate that the Fourteenth Amendment contains no

9

blanket prohibition against raciaily-conscious state decisions.

Whether United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) and Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S.

535 (1974) govern the present case, as we submit, or are dis

tinguishable on the facts, as respondent and the amici supporting

him contend, the decisions undeniably rule that race- or color

conscious state action is not unconstitutional per se. Compare

Califano v. Webster, 97 S.Ct. 1192 (1977) (upholding a legis

lative classification favorable to working women generally as

appropriate to offset earlier economic discrimination).

2. The Brief for the Anti-Defamation League, et al., chal

lenges the constitutionality of taking race into account on the basis

of lofty abstractions; for example—-

. . . the rights of non-whites to be equal . . .

Brief at 13.

Equality denotes a relationship among those who are to be

treated equally by the government.

Ibid.

. . . equal treatment of equals

Id. at 15.

The Equal Protection Clause means that the constitutional

rights of a person cannot depend upon his race . . .

Id. at 13.

We have no quarrel with these abstractions. Decision requires

the application of such abstractions to living facts. Even identity

of treatment sometimes is unequal. Consider the inequality pro

duced by enrolling in the very same classes at the very same school

both the child of an old California family and a child who grew

up in a Chinese-speaking family in San Francisco’s Chinese com

munity. Is this equal treatment of equals ? Cf. Lau v. Nichols, 414

U.S. 563 (1974).

The Anti-Defamation League elsewhere suggests an acceptable

test (Brief at 14) :

“The Equal Protection Clause commands that state govern

ments treat persons equally unless their personal attributes

or actions afford justification for different treatment.”

State universities serve social purposes. Places in professional

10

schools are not to be awarded as if they were prizes. Selection for

admissions is not simply a rationing of benefits; it involves deci

sions concerning the characteristics of the kinds of students and

graduates of professional schools which society needs. Here, in

today’s society, because of the past, being black, chicano, Asian or

American Indian, is a fact and a highly relevant personal attribute.

Race or color is relevant to educational and social policies and

therefore to admissions, not because being black, chicano, Asian

or American Indian is inherently better or worse, or makes one

more deserving or less deserving than anyone else, but because

decades of hostile discrimination, de jure as well as de facto, iso

lated the minorities in barrios and black or yellow ghettoes and on

Indian reservations, yielded inferior education, denied the minori

ties access to the more rewarding occupations and thus withheld

from succeeding generations the examples which stimulate self

advancement. The Equal Protection Clause does not require the

Court to blind itself to what all the world knows. These truths

determine the current meaning of the abstract ideals.

The question therefore is whether a state may voluntarily take

steps to eliminate the racial isolation, offset the racial deprivations

and demonstrate that minorities once the victims of racial discrim

ination can have equality of opportunity, so that the conditions

resulting from the past may be eliminated and true equality more

nearly realized.

Race is a personal characteristic relevant to the implementation

of such measures. The Task Force program fits the test that counsel

propose. Race will become irrelevant if the measures are permitted

to succeed. Then, race-conscious admissions programs will no

longer be required or justified.

3. The remaining arguments opposing any race-conscious gov

ernment action rest chiefly upon the wooden citation or quotation

of prior opinions condemning racial discrimination against minori

ties. E.g., Brief for Respondent at 42-43; Brief for Anti-Defama

tion League, et al., at 19- The absolute or virtually absolute

constitutional rule against intentional discrimination hostile to

minorities flows from the concurrence of vices absent from such

cases as Williamsburgh and Mancari and also absent from the

11

instant case. Discrimination against a racial minority is less suscep

tible of correction through the political process. United States v.

Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4 (1938); Hunter v.

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385, 391 (1969); Ely, 'The Constitutionality of

Reverse Discrimination, 41 U.Chi.L.Rev. 723 (1974). Hostile

discrimination sets the minority apart from the general society

instead of bringing its members into the mainstream—into the

political process, as in the Williams burgh case, or into higher edu

cation and a learned profession, as in the present case. Nearly

always, hostile discrimination against the black, the Asian, the

American Indian or the chicano, viewed in the background of

American history, falsely asserts and thus reinforces a form of

caste. None of these consequences are threatened by measures to

offset the isolation and living inequality imposed by the past.

There is no force in the argument that admission under the

minority admissions program imposes a stigma because it implies

that the minority student is inherently incapable of competing

with other applicants. The very predicate of the Task Force pro

gram is that qualified minority students from disadvantaged back

grounds can do medical school work successfully and can become

as skillful and useful doctors as their contemporaries selected

under the general admissions program. If their lower but wholly

acceptable scores under other admissions criteria need explanation,

they may be taken to flow not from any racial inferiority but from

years of pervasive segregation and discrimination: from inferior

education, denial of economic opportunity, cultural isolation and

the deadening effect of the absence of visible evidence of opportu

nities for advancement through the channels open to the dominant

whites.

The differences in conventional predictors of academic success

will not go away under respondent’s interpretation of the Equal

Protection Clause. No one is required to request consideration

under the Task Force program or to indicate his race. Surely it is

less stigmatizing to be found qualified for a medical education and

then admitted under the minority admissions procedure than it is

to be denied admission and learn that nearly all applications from

members of minority groups are denied.

12

III.

THE EDUCATIONAL AND SOCIAL PURPOSES TO WHICH THE

POLICY IS TAILORED AMPLY JUSTIFY CONSCIOUSLY IN-

CREASING THE NUMBER OF QUALIFIED APPLICANTS

CHOSEN FROM MINORITY GROUPS.

A. A number of briefs assert, explicitly or implicitly, that the

decision below should be affirmed because the University failed

to prove adequately on the record that the special admissions pro

gram was adopted to serve and does in fact serve important pub

lic objectives. Although we would not agree that proof on the

record is the exclusive means of establishing such objectives (see

pp. 16-18, infra), the record puts the purposes of the program

beyond dispute. Dean Lowrey testified (R. 65, 68-69):

* * * [I]n order to increase the number of doctors in dis

advantaged areas, to bring diversity to the class and the pro

fession, a special admissions program has been established

which gives preference to applicants from disadvantaged

backgrounds, which uses minority group status as one fac

tor in determining relative disadvantage.

* * *

The minorities will bring with them a concern for the

problems and needs of the disadvantaged areas from which

they come. * * * And, it is hoped that many of them will

return to practice medicine in those areas which are pres

ently in great need of doctors. Every applicant admitted

under the special admissions program has expressed an in

terest in practicing in a disadvantaged community.

Practice in disadvantaged communities by minority physi

cians will provide an example to younger persons in these

areas demonstrating that disadvantaged and minority per

sons can break the cycle of hopelessness in which families

do not improve their educational or economic status over

generations.

The non-disadvantaged professors, students and members

of the medical profession with whom the disadvantaged fel

low student or doctor comes into contact will be influenced

and enriched by that contact. * * *

At this point in history there can be few higher social aims than

those attested by Dr. Lowrey. They amply justify race-conscious

13

measures well tailored to achieving them, when no other means

are readily available, even though the race-consicious measures

may carry some unavoidable costs.

B. It is also argued that the University failed to prove that

the Task Force program is tailored to the objectives and necessary

to achieve them.

Again, insofar as the record is concerned, a succinct answer is

provided by Dr. Lowrey’s testimony that the special admissions

program was "the only method” whereby the school could achieve

its objectives (R. 67).

Respondent offered no contrary evidence. Our opening brief,

the briefs of amici supporting petitioner and the voluminous litera

ture cited, all demonstrate that minority admissions programs are

indispensable to enabling any significant numbers of the victims of

past racial discrimination to enter higher education and the learned

professions. The United States has reached the same conclusion

(Brief at 63). No one has suggested a viable alternative. Counsel

for respondent virtually confess their inability by concluding that

"it is not credible that so great a University . . . if so inclined,

would lack the ingenuity and resources to pursue new alterna

tives. . . . ” (Resp. Br. at 16.)

In proceeding in this fashion we follow the customary practice

in this Court. In determining the constitutionality of programs

whose validity depends upon their functions and effects in the sur

rounding sociological, economic or political context, the Court

regularly looks to legislative investigations, the writings of in

formed persons and other relevant data to which attention is di

rected by the briefs. Any other practice would result in constant

relitigation. The constitutionality of the same measure would

vary according to the testimony and trial court’s findings of fact

in each particular case.

IV.

VOLUNTARY MINORITY ADMISSIONS PROGRAMS RAISE DIF-

FERENT CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES FROM MANDATORY

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAMS OF MINORITY EM-

PLOYMENT.

A number of amici have filed briefs linking the Task Force pro

gram at Davis with governmentally mandated programs seeking to

14

increase the employment of black and other minority workers and

of women. Some of these programs fix numerical "quotas” or

"targets” for the purpose of determining whether an employer has

taken appropriate affirmative action. Some programs appear to re

quire an employer, at the risk of heavy liability, to steer between

the Scylla of failure to take affirmative action and the Charybdis

of discrimination against whites.

The constitutionality of these mandatory programs can and

should be put aside for future determination. If the Court should

follow the Supreme Court of California in holding that the Equal

Protection Clause forbids a state to make race a factor in allocat

ing its educational resources in order to achieve educational and

social objectives, then logic may dictate the invalidity of all racially-

conscious programs for increasing minority employment or build

ing minority business opportunities, just as it would seem to force

the abandonment of all programs specifically tailored to help mem

bers of minority groups to overcome the disadvantage and isola

tion resulting from decades of pervasive racial discrimination. But

the converse proposition is not true. To hold that voluntary mi

nority admissions programs are consistent with the Equal Protec

tion Clause would not establish the validity of mandatory affirma

tive action programs for minority employment.

The differences are two:

First, the minority admissions program was voluntarily adopted

by the Davis faculty. To reverse the decision below would leave

the states free, each either to set the admissions criteria for state

institutions by legislative action or else to allow each public insti

tution to set its own criteria according to the faculty’s choice of

educational objectives. Insofar as private institutions are affected,

reversal would increase the freedom and responsibility of each

institution to make its individual choice. Contrariwise, in the area

of industrial and commercial employment, governmental affirma

tive action programs curtail the employer’s freedom.

The difference distinguishes the constitutional issues in a major

respect. Even though the power of government to regulate em

ployment practices and contracts is now well established, liberty

is still a major element of every constitutional equation.

15

Second, even though the ultimate general aims of minority ad

missions and government-mandated employment programs are

similar, the two might well be found distinguishable in the rela

tive importance of the mandated objectives, in the need for the

program to offset the effects of previous discrimination and isola

tion, and in the availability of other means for achieving the

ultimate general goals.

For either reason or both, the reversal of the judgment below

would not pre-judge the constitutionality of the employment pro

grams to which amici such as the United States Chamber of Com

merce object.

V.

THE CASE SHOULD NOT BE REMANDED FOR THE FINDINGS

SUGGESTED BY THE UNITED STATES.

The undisputed facts bring the case well within the constitu

tional principle advanced by the Brief for the United States (p.

23): " . . . a state university admissions program may take race

into account to remedy the effects of societal discrimination.” There

is neither allegation nor evidence of "racial slur or stigma,” of "a

'contrivance to segregate’ the group,” of an “intended . . . racial

insult or injury to those whites who are adversely affected” or of

the "invidious purpose of discriminating against white [appli

cants].” United Jewish Organizations of Williamshurgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 165 (opinion of the Court), 172, 178 (Bren

nan, J., concurring in part), 180 (Powell and Stewart, JJ., con

curring) (1977). Dean Lowrey’s undisputed testimony, quoted

above (pp. 12-13), detailed the remedial purposes and functions of

the Task Force program. The wealth of professional opinion cited

in our opening brief demonstrates the soundness of the profes

sional judgments of the Davis Medical School faculty.

The United States proposes for this case—and presumably for

every other case which a disappointed applicant may bring into a

state or federal court—an examination into the reasons for adopt

ing a particular program of minority admissions, and also into the

actual operation of the program, probing even the mental processes

of the admissions committee. The suggestion is that upon remand

16

in this case the courts below are to take evidence concerning the

details of the use of benchmark scores; into why one non-minority

applicant was admitted who had a lower benchmark score than

another non-minority applicant; into the effect of the individ

uality of the evaluators upon benchmark scores; and into " how

race was used” (Brief at 71). The brief also implies that the state

court is to take evidence and find as a fact whether the dean and

faculty at Davis were right in thinking that the admission of more

fully-qualified students from minority communities would tend to

increase the availability and use of medical services in the com

munities from which they were drawn ( ibid.).

The Attorney General does not state the legal significance of

such inquiries. Apparently that is to be left undecided until every

angle which occurs to ingenious counsel has been explored and

new legal formulas proposed.

To follow this course would invite voluminous litigation

throughout the country. It would put every minority admissions

program at the hazard not only of speculative findings of fact but

of such detailed constitutional requirements as different district

courts might prescribe.

The longer range effects would depend upon the rules estab

lished by this Court. We cannot discern what rules the Attorney

General contemplates, but two intimations reveal the hazards to

which universities might be subjected.

One of the remedial factors taken into account in establishing

the Task Force program was the need to improve the delivery and

use of medical services in disadvantaged minority communities.

The Brief for the United States at 71 suggests that this objective

may not be a legal justification, and further complains of a lack

of evidence showing that the judgment of the dean and faculty

upon this point is correct. Must every professional school which

adopts a minority admissions program risk judicial inquiry and

adverse findings upon the accuracy of such judgments and/or

upon the weight which various members of the faculty gave to

their own judgment in voting to increase minority admissions by

the conscious attention to race?

17

It is also asserted that the precise manner in which race is taken

into account in specific decisions to admit or deny individual ap

plicants may be constitutionally decisive. There is even a hint—

perhaps unintended2—that minority-sensitive programs must be

confined to taking into account the effects of past discrimination

upon the credentials presented by individual applicants; and that

a university must ignore broader social purposes such as (1) im

proving education by increasing the diversity of the student body,

(2) demonstrating the opening of opportunities to members of mi

nority communities by living examples, and (3) otherwise break

ing down the isolation produced by generations of racial dis

crimination. Any such effort to prescribe the exact manner or ex

tent to which minority status may be taken into account for general

remedial and non-invidious purposes would have disastrous con

sequences.

There is no intellectually honest way of measuring the effects,

if any, of minority status upon an individual minority applicant’s

past performance in order to compare him or her individually with

other non-minority applicants. Nor is there any measurable mean

or average effect which could be imputed to individual members

of minority groups. Few, if any, admissions committees could

conscientiously assert that they had followed this process and had

given no other attention to race. Were this the test of legality, the

risks of litigation and adverse findings would foreclose even the

most conscientious effort to put such a policy into effect. Deans and

2. Elsewhere the Attorney General recognizes that attention to minority

status can be justified by the broader remedial objectives:

Moreover, this Court has recognized that "substantial benefits flow

to both whites and blacks from interracial association

Brief at 25.

A State therefore is free, within constitutional constraints, to under

take remedial minority-sensitive measures that are designed, like the

Fourteenth Amendment itself, to break down the barriers that have

separated the races.

Id. at 37.

In searching for those applicants most likely to contribute to the

medical profession, medical schools look . . . at . . . the extent to

which applicants can diversify and enrich the profession.

Id. at 60.

18

teachers are well aware of, and sympathetic to, the many other

ways in which increasing the number of qualified minority stu

dents at graduate schools serves the goal of correcting the awful

legacy of generations of racial discrimination. The plaintiffs’ at

torneys could easily bring out such facts as that the program had

been established initially with such objectives in mind, prior to

the decision limiting the use of race; that the witness believed

that the isolation and disadvantages flowing from past discrimi

nation should be corrected; and that he thought the program

would have such consequences in fact even though no applicants

were admitted in pursuit of such objectives. No great skill in ex

amining witnesses would then be required to cast doubt upon

whether the beneficient but now artificially irrelevant consequences

had been rigidly excluded from the witness’ mind in selecting

minority applicants even as he was making a favorable adjustment

for the adverse effects of historic discrimination upon the appli

cant himself.

Few institutions could face the expense and risks of litigation

turning upon such speculative factual inquiries, however deep

their commitment to helping to fill "the need for effective social

policies promoting racial justice in a society beset by deep-rooted

racial inequities” ( United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh,

Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 175 (1977) (Brennan, J., concurring

in part) ).

No race-conscious admission program should be wholly free

from constitutional scrutiny. ĴChen race is taken into account, the

federal courts, upon a proper showing, have a duty to inquire ( l )

whether the use is noninvidious, (2) whether the program was

adopted to counter the effects of past societal discrimination and

secure the educational, professional and social benefits of racial

diversity, and (3) whether the program is tailored to such objec

tives. Once these criteria are satisfied, as in the present case, the

judicial function is discharged. The Constitution does not charge

the federal courts with detailed supervision of the admissions

policies and practices of state colleges and universities. Cf., Rizzo

v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362, 380 (1976); Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S.

19

341, 349-50 (1976); Meachum v. Fano, A ll U.S. 215, 228-29

(1976).

To increase the enrollment of students from minority groups

unavoidably requires departing from previous standards of com

parison and giving attention to race. All effective minority admis

sions programs start from this premise. In other respects, there is

wide variation. Some faculties, having knowledge of the charac

teristics and abilities of applicants to the particular school, have

thought it wise to fix for the admissions committee the maximum

number of qualified minority students to be admitted in any given

year through special admissions programs. Others prefer to leave

the committee a degree of flexibility. Some institutions may give

special consideration only to the members of minority groups who

have suffered additional personal disadvantage, as at Davis. Many

more look only to the need for racial diversity and the benefits

of interracial association. Some professional schools process all

applications through a single committee. Others divide the work

and authorize each of two, three or four committees to fill inde

pendently a fraction of the class. Still others make a point of

including minority members of the faculty and student body on a

subcommittee to interview and select minority applicants, believing

that the minority applicants can be evaluated with greater percep

tion by those who have shared common problems and experience.3

Everywhere admissions policies and procedures undergo constant

study and debate. Everywhere experience brings better under

standing.

This Court should not shut off the study, debate and experi

mentation by undertaking to prescribe, upon further findings, a

detailed set of constitutional rules. "One of the great virtues of

federalism is the opportunity it affords for experimentation and

innovation, with freedom to discard or amend that which proves

unsuccessful or detrimental to the public good.” Bates v. State

3. The California Supreme Court erred in stating that the faculty

members of the Task Force subcommittee were "predominantly” minorities

(Pet. App. at 6a). In fact, as the record clearly shows, four of the six

faculty members and the one administration member of the subcommittee

for the class entering in 1973 were non-minorities. All student members

were minorities (R. 251-52).

20

Bar of Arizona, 97 S.Ct. 2691, 2718-19 (1977) (Powell, J ,

dissenting). The reminder has special pertinence in dealing with

the "myriad of 'intractable economic, social, and even philosoph

ical problems’ ” which education presents. San Antonio School

District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 42 (1973). Few of these are as

perplexing or as sensitive as the task of selecting from a large

pool of thoroughly qualified applicants the relatively small num

ber of students whom the institution has the resources to teach.

None is as intractable as the problem of relieving the deeply-

ingrained obstacles which history has put in the way of minorities’

enjoyment of access to higher education and the opportunities to

which it leads. Yet there is no escape from the necessity of pursu

ing the goal with minds open to the growing understanding about

means which comes from trial and experience. Anything less would

impair the search for truly equal opportunity for all men and

women promised by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment and given renewed force by this Court in Brown v.

Board of Education.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in petitioner’s opening brief and this

reply brief the judgment of the Supreme Court of California

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

A r c h ib a ld C o x

Langdell Hall

Cambridge, MASS 02138

D o n a l d L. R eid h a a r

590 University Hall

Berkeley, CA 94720

Counsel for Petitioner

P a u l J . M is h k in

J a c k B. O w e n s

Of Counsel on the Reply Brief