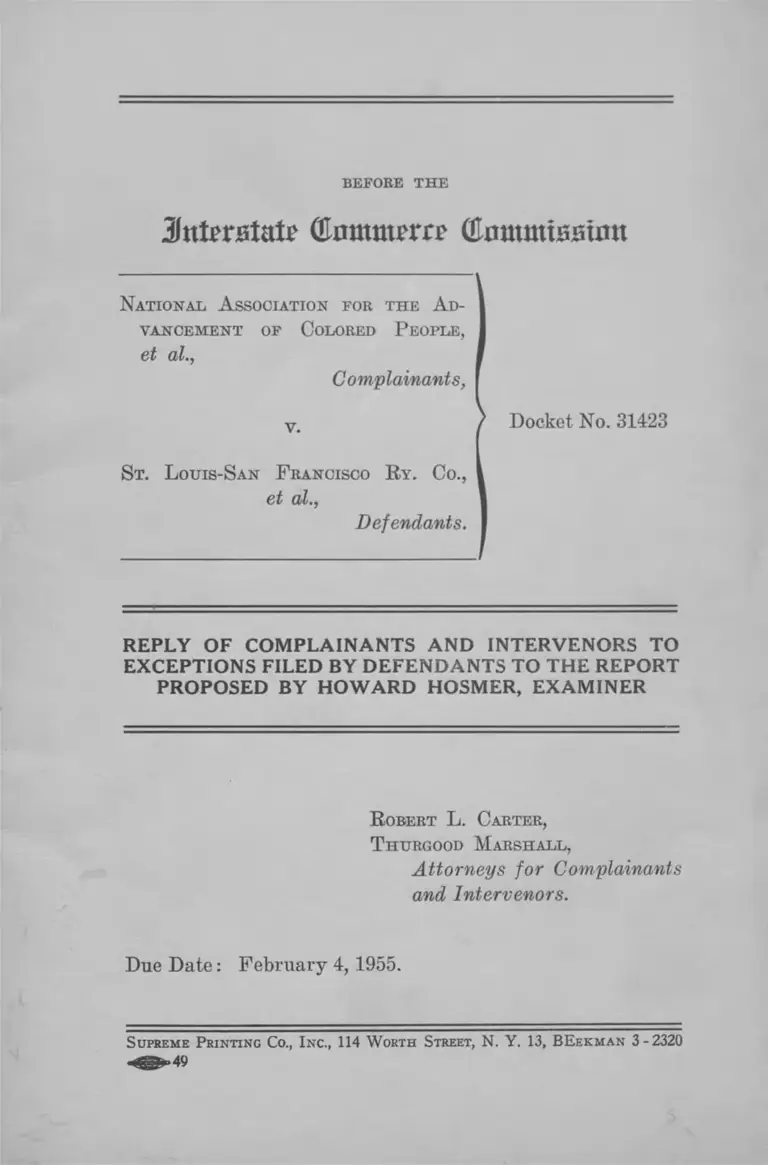

NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Reply of Complainants and Intervenors to Exceptions

Public Court Documents

February 4, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Reply of Complainants and Intervenors to Exceptions, 1955. 769f8946-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/300ae57c-f10c-4851-b4be-e4a0c6d364bc/naacp-v-st-louis-san-francisco-ry-co-reply-of-complainants-and-intervenors-to-exceptions. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

BEFORE THE

Ifn te ra ta te (Qjratsn?rr? C o m m tB B to n

National A ssociation for the A d

vancement of Colored P eople,

et al.,

Complainants,

v.

S t. L ouis-S an F rancisco Ry . Co.,

et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423

REPLY OF COMPLAINANTS AND INTERVENORS TO

EXCEPTIONS FILED BY DEFENDANTS TO THE REPORT

PROPOSED BY HOWARD HOSMER, EXAMINER

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Complainants

and Intervenors.

Due Date: February 4,1955.

S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BE ekman 3 - 2320

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement ........................................................................ 1

Argument .................................................................. . 2

The Examiner’s recommendation that the Com

missioner order these defendants to cease main

taining segregation in railroad coaches and in

railway station waiting rooms is well grounded

in law and reason and should be adopted.......... 2

A. Findings of Fact By the Trier of Fact Must

Be Sustained Unless Clearly Wrong and Not

Supported by the Evidence ......................... 2

B. It Is In the Public Interest That the Issue

Raised Herein Be Squarely Met and Decided,

and Dilatory Defenses Should Be Disre

garded As Immaterial..................................... 2

C. There Is No Warrant Either in the Language

or Legislative History of the Interstate Com

merce Act For Construing Section 3(1) as

Limited To Only That Kind of Racial Dis

crimination Involved in a Denial of Equal

Physical Facilities ........................................... 5

D. The Separate But Equal Doctrine Reap

praised ..................................................................... 10

E. The Supreme Court Decisions Support the

Recommendations of the Exam iner.................. 13

F. Segregation in Coaches and Waiting Rooms

Is Discrimination Within the Meaning of

3 ( 1 ) .......................................................................... 17

Conclusion............................................................................ 18

PAGE

11

Table of Cases

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28

(1948) .......................................................................... 12

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954 )..................... 9,18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 9,11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 85 (1 9 17 ).......... 11

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (CA 4th 1951)

cert, denied 341 U. S. 941 (1951 )............................. 13

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. v. United States, 11 F. Supp.

588 (S. W. W. Va. 1935), aff’d 296 U. S. 1 8 7 ........ 7

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71

(1910) .......................................................................... 12,13

Councill v. Western and Atlantic R. R. Co., 1 1. C. C.

638 (1887) .................................................................. 8,9

Cumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 (1899) .................................................................. 11

Edwards v. Nashville C. & St. L. Ry. Co., 12 I. C. C.

247 (1907) ................................................................ 9

Evans v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 92 I. C. C.

713 (1924) ................................................................ 9

Foister v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No.

937 (E. D. La. 1952) unreported............................... 15

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1 9 27 )........................ 12

Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Ten

nessee, 342 U. S. 517 (1952) ................................... 14

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1878) ........................... 13

Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 719 (1888) . . . 8, 9

Helvering v. Hallock, 309 U. S. 106 (1940) .............. 8

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 (1950).. 10,12,

13,14

Howitt, et al. v. United States, 328 U. S. 189 (1946). 6

Interstate Commerce Commission v. Chicago, Rock

Island & Pacific Ry. Co., 218 IT. S. 88 (1 9 10 )........ 6

PAGE

Ill

Jackson v. Seaboard Airlines Ry. Co., 269 I. C. C.

399 (1947) .................................................................... 9,10

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th

1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 951 (1951) .............. 14

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 (1950) .................................................................. 12

Merchants AVarehouse Co. v. United States, 283

U. S. 501 (1931) ........................................................ 6

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 12

Mitchell v. Board of Regents of University of Mary

land, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore City

Court 1950) unreported ......................................... 15

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941) 6,12,13,14

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 337 (1946 ).................. 12,13

New York v. United States, 331 U. S. 284 (1947) . . . 6

Payne v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 894

(E.D. La. 1952) unreported..................................... 14

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) .............. 11

Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 AVall 445 (1873) .......... 15,16

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 1, 22 (1948) ..................... 17

Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631 (1948) .................. 12

Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civil Action No.

30 (AV.D. Va. 1950) unreported ......................... 14

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) .............. 11,12,17

Unexcelled Chemical Corp. v. United States, 345 U. S.

59 (1953) .................................................................... 6

United States v. Baltimore & Ohio R. R. Co., 333

U. S. 169 (1948) ......................................................... 7

United States v. Congress of Industrial Organiza

tions, 335 U. S. 106 (1948) ..................................... 6

United States v. Universal C. I. T. Credit Corp., 344

U. S. 218 (1952)

PAGE

6

IV

PAGE

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949

(CA 6th 1949) ............................................................ 13

Williams v. Carolina Coach Co., I l l F. Supp. 329

(E.D. Va. 1952) ........................................................ 13

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986

(E.D. La. 1950), a ff’d 340 U. S. 909 (1951) .......... 14

Other Authorities

Davis, Standing to Challenge and Enforce Adminis

trative Action, 49 Col. L. Rev. 752, 772-779 (1949) 3

Dollard, Caste and Class In A Southern Town 350

(1937)............................................................................ 17

Fort, Jr., Who May Maintain Suits to Set Aside

Orders of the Interstate Commerce Commission, 12

I. C. C. Pract. J. 792 (1945) ................................... 3

Frankfurter, Note On Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv.

L. Rev. 1002 (1924) ................................................. 3

Johnson, Pattern of Negro Segregation 270 (1943) 17

Myrdal, American Dilemma, Vol. 1, p. 635 (1944) 17

Sen. Rep. No. 46, 49 Cong. 1st Sess. (1 8 86 ).............. 8

BEFORE THE

J n t r r H t a t e ( E m tt m e m (ftom m tBBum

National, A ssociation for the A d

vancement of Colored People,

et al.,

Complainants,

v .

S t . L ouis-S an F rancisco B y . C o.,

et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423

REPLY OF COMPLAINANTS AND INTERVENORS TO

EXCEPTIONS FILED BY DEFENDANTS TO THE REPORT

PROPOSED BY HOWARD HOSMER, EXAMINER

Statement

Six different sets of Exceptions were filed by defendants

to Mr. Hosmer’s proposed report insofar as it recom

mended the issuance of appropriate orders by the Commis

sion barring the segregation of Negro and white passen

gers on railroad coaches and in railway station waiting-

rooms, including barring the use of signs and other racial

designations. These Exceptions range from the jurisdic

tional objections raised by Texas and Pacific Ry. Co. to

the argument on the merits made by the Atlantic Coast

Line R. R. Co. Only the Missouri Pacific R. R. Co. took

no exceptions to the Examiner’s report.

In our judgment none of defendants’ Exceptions are

well taken; and all fail to shake the fundamental validity

of the Examiner’s reasoning and conclusions concerning

the power of the Commission to bar racial segregation in

railroad coaches and in railway stations.

2

ARGUMENT

The Examiner’s recommendation that the Commis

sion order these defendants to cease maintaining seg

regation in railroad coaches and in railway station

waiting rooms is well grounded in law and reason and

should be adopted.

A.

Findings of Fact By the Trier of Fact Must Be Sustained

Unless Clearly Wrong and Not Supported by the Evidence.

The Illinois Central R. R. Co., the Richmond Terminal

Railway Co. and the Seaboard Airlines R. R. Co. dispute

the Examiner’s finding that they have a policy of racial

segregation. The Illinois Central and the Richmond Ter

minal contend that they have no such policy, and that the

loading practices and cards of the Illinois Central and the

signs of the Richmond Terminal are merely a part of an

effort to cater to the comfort of Negro passengers since

Negro passengers prefer segregation. It is an elemental

rule that when a trier of fact makes a finding of fact, as

distinguished from a conclusion of law, that on review his

finding as to the facts must be sustained unless clearly

wrong and not supported by the evidence. The Exam

iner’s findings in this cause are not subject to objection

on either score and we submit, therefore, that the findings

of the Examiner that these carriers practice segregation

must be sustained.

B.

It Is In the Public Interest That the Issue Raised Herein

Be Squarely Met and Decided, and Dilatory Defenses

Should Be Disregarded As Immaterial.

All the defendants in one form or another seek to limit

the reach and scope of the complaint. The complaint is

clearly as broad as the Examiner interpreted it to be. In

3

the complaint, amended complaint and at the prehearing

conference, it was made clear that all the named defend

ants were charged by all the complainants with enforcing

a policy or practice of segregation, and that complaint was

levelled against all defendants jointly and severally. The

specific instances referred to were cited as examples of the

policy and practice about which complaint was being made,

and was not intended to limit the scope of the overall griev

ance in any way. It is no secret that complainants are

here seeking to attack the right of any carrier, subject to

the Interstate Commerce Act, to enforce a policy or prac

tice of segregation with respect to railroad facilities, rail

way stations and restaurants. And, we submit, the scope

of the complaint was clear to all defendants at the outset

of these proceedings.

To base a defense here on a concept of the plaintiff’s

burden of proof in a judicial proceeding is highly unreal

istic. We submit that we have demonstrated sufficiently

even for a court of law that all defendants maintain a

policy and practice of segregation. Even if we had failed

to do so, this could not have been a safe basis for defend

ants to contest the Commission’s power to issue the order

recommended by the Examiner. These are not yet “ adver

sary” proceedings. Nor is a proceeding before the Com

mission a “ case and controversy” in the strict judicial

sense. Any member of the public may bring to the Com

mission’s attention the fact that a violation of the law is

taking place.1 The Commission is not confined by rules of

1 For an excellent discussion of the differences between a proper

party in interest before the Commission and in a regular judicial pro

ceedings, see Fort, Jr., Who May Maintain Suits To Set Aside

Orders of the Interstate Commerce Commission, 12 I. C. C. Pract. J.,

792 (1945) ; and see generally Davis, Standing To Challenge and

Enforce Administrative Action, 49 Col. L. Rev. 752, 772-779 (1949),

and Frankfurter, Note on Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv. L. Rev.

1002 (1924).

4

evidence like a court of law, but it is able to make its own

investigation of the issues raised without regard to what

complainants or defendants may show, and issue such

orders as it deems appropriate. In view of the Commis

sion’s unquestioned power in this regard, it is somewhat

strange that dilatory and technical defenses should be

raised at this time.

All defendants had the opportunity to produce evidence

showing what their policies and practices were with respect

to segregation. If sufficient proof has not been adduced

already, the Commission has unquestioned power to take

further evidence, as the Examiner pointed out. Surely,

Kansas City Southern, as one of those which has entered

into stipulations concerning its practices in interstate com

merce, cannot seriously contend that if the Commission

should adopt the Examiner’s recommendation that it

should not be bound by such an order. Indeed, the Com

mission has the authority to issue rules and regulations

applicable to all carriers subject to its jurisdiction barring

the maintenance of segregation on railroad facilities and

in railway stations and restaurants, even though some car

riers affected may not be parties to a proceeding before it.

As to the Seaboard Air Lines R. R. Co. and the Texas

and Pacific Ry. Co., we have made out a prima facie case

showing that they do segregate Negro and white passengers

in interstate commerce. Neither the Texas and Pacific nor

the Seaboard Air Lines made any attempt to produce evi

dence to the contrary either through testimony of their

own officials or by introduction of their written regulations

and instructions on the subject. They chose not to do so.

In any event, if any carrier does not enforce a policy of

segregation, an order by the Commission requiring it not

to segregate could certainly do the carrier no injury.

We respectfully submit that the question raised here

should be settled once and for all so that both carriers and

5

public will know exactly what are their rights and obliga

tions. For these reasons, we urge that all extraneous

defenses be disregarded and that the basic issue be decided

on its merits as to all defendants herein.

C.

There Is No Warrant Either in the Language or Legisla

tive History of the Interstate Commerce Act For Construing

Section 3(1) as Limited To Only That Kind of Racial Dis

crimination Involved in a Denial of Equal Physical Facili

ties.

1. The basic substantive argument advanced by the

defendants is contained in the exceptions filed on behalf of

the Atlantic Coast Line R. R. Co. and the several other

defendant carriers that entered into stipulations concern

ing their practices. In essence, their contention is that the

Examiner’s recommendations that segregation in coaches

and waiting rooms be outlawed is contrary to judicial and

administrative holdings; and that adoption of such recom

mendations would necessitate a modification or extension

of the scope and reach of the Interstate Commerce Act

which would constitute an usurpation of Congressional

authority by the Commission. What defendants are really

saying is that segregation per se cannot be barred by the

Commission, and that the Interstate Commerce Act reaches

only that form of racial discrimination which results from

a denial of equal facilities under the “ separate but equal’ ’

doctrine.

This is a somewhat startling conception of the Commis

sion’s power, and defendants’ contention has validity only

if the language of the Act is unmistakably clear in its incor

poration of the “ separate but equal’ ’ philosophy; or bar

ring that, if the statutory construction which defendants

6

advance is consistent with the intent of Congress as shown

by the legislative history of the Interstate Commerce Act.2

2. The pertinent language in Section 3(1) which has

formed the basis for the Commission’s authority to bar

racial discrimination and discrimination of any other kind,

is the prohibition against “ undue or unreasonable prefer

ence or advantage” and against “ undue or unreasonable

prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.”

Not only is “ separate but equal” not mentioned in Sec

tion 3(1) and nowhere else in the Act, but discrimination

is barred in sweeping and all inclusive terms. The courts

have found this language unambiguous, and as we pointed

out heretofore in our own Exceptions, this language has

been interpreted as a broad barrier against discrimination

of any kind whatsoever. Interstate Commerce Commis

sion v. Chicago Rock Island & Pacific Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 88

(1910); Merchants Warehouse Co. v. United States, 283

U. S. 501 (1931); Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80

(1941); Howitt, et al. v. United States, 328 U. S. 189 (1946);

New York v. United States, 331 U. S. 284 (1947); United

2 Arguments of policy are relevant in construing a statute only

when there is ambiguity in legislative language which must be

resolved. Unexcelled Chemical Corp. v. United States, 345 U. S.

59 (1953). Where the meaning of a statute is not clear on its face,

the purpose of Congress is a dominant factor in determining the

statute’s true meaning. See United States v. Congress of Industrial

Organisations, 335 U. S. 106 (1948); United States v. Universal

C. I. T. Credit Corp., 344 U. S. 218 (1952). In United States v.

Universal C. I. T. Credit Corp., supra, Mr. Justice Frankfurter

speaking for the Court stated at pages 221, 222 that “ we may utilize,

in construing a statute not unambiguous, all the light relevantly shed

upon the words and the clause and the statute that express the purpose

of Congress.” Moreover, “ (ijnstead of balancing the various gen

eralized axioms of experience in construing legislation, regard for

the specific history of the legislative process that culminated in the

Act * * * affords more solid ground for giving it appropriate mean

ing.”

7

States v. Baltimore & Ohio R. R. Co., 333 U. S. 169 (1948);

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. v. United States, 11 F. Supp. 588

(S. W. W. Va. 1935), aff’d 296 U. S. 187.

If we look to the language of the Act, therefore, defend

ants’ arguments necessarily fail. Indeed, from the lan

guage it is so clear that all lands of discrimination are pro

hibited that no further inquiry is necessary to support a

holding that the separation of Negro and white passengers,

in the use and enjoyment of interstate transportation

facilities, is included in that discrimination which the Inter

state Commerce Act was intended to abolish.

3. I f we assume arguendo, however, that the language

does not settle the proposition, then we must look to the

reports and debates of Congress to determine how far the

Congress meant to go in enacting Section 3(1). After such

an inquiry, it may be categorically stated that there is noth

ing whatsoever in the Congressional reports or debates on

the Interstate Commerce Act to warrant a conclusion that

the Congress was delegating to the Commission power to

deal with one land of racial discrimination and withholding

power to deal with another. In fact, the evidence is to the

contrary. It is clear that Congress was attempting to make

certain that the railroads would be open and free from any

and all manner of obstructions which might impede the

free flow of commerce throughout the United States. To

assure accomplishment of this purpose, Congress granted

to the Commission broad power to deal with every kind of

discrimination which might be devised.

In sum, there is nothing in the reports on the Interstate

Commerce Act to warrant a conclusion that the Congress

was incorporating into the Act the “ separate hut equal”

doctrine. On the contrary, the reports show that Congress

was delegating broad power to the Commission to assure

equality in transportation between persons and localities.

8

See Sen. Rep. No. 46, pp. 178, 182, 190, 215, 49 Cong. 1st

Sess. (1886).

Nor does defendants’ argument concerning Congres

sional inaction help their cause. Congressional inaction

after a court or administrative agency has construed a

statute does not constitute proof that Congress has acqui

esced in the interpretation given by the court or agency.

This was settled by the United States Supreme Court in

Helvering v. Hallock, 309 U. S. 106 (1940), where the Court

overruled an early line of cases involving construction of

the federal estate tax statute.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, speaking for the majority

declared at pages 119-120:

“ Nor does want of specific congressional repudia

tions of the St. Louis Union Trust Co. Cases serve as

an implied instruction by Congress to us not to recon

sider, in the light of new experience, whether those

decisions, in conjunction with the Klein Case, make

for dissonance of doctrine. It would require very per

suasive circumstances enveloping congressional

silence to debar this Court from reexamining its own

doctrines. To explain the cause of nonaction by

Congress when Congress itself sheds no light is to

venture into speculative unrealities.” (emphasis

added.)

It should be added here that there is no more validity

for interpreting Congressional silence as consent to prior

interpretations of Section 3(1) than there was for inter

preting Congressional silence as endorsement of the Plessy

v. Ferguson concept of the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Defendants quite properly cite Councill v. Western and

Atlantic R. R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 638 (1887); Heard v. Georgia

9

R. R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 719 (1888); Edwards v. Nashville C.

& St. L. Ry. Co., 12 L C. C. 247 (1907); Evans v. Chesa

peake <& Ohio Ry. Co., 92 I. C. C. 713 (1924); and Jackson

v. Seaboard Airlines Ry. Co., 269 I. C. C. 399 (1947), as

supporting their contention that segregation within the

“ separate but equal” formula is condoned by the Inter

state Commerce Act. It should be pointed out, however,

that these decisions were based merely upon a belief, then

current, that racial discrimination did not include racial

segregation.3 New knowledge and understanding of the

3 In Councill v. Western and Atlantic R. R. Co., the Commission

ruled that the facilities provided by defendant railroad were unequal

and in violation of Section 3 (1 ). The Commission also held that

as long as the defendant provided “ equal” facilities it would not be

compelled to end segregation. In reaching this decision, however,

the Commission looked neither to the language nor the history of

the Interstate Commerce Act. Rather, it cited as supporting author

ity the decisions of state courts upholding a carrier’s right to main

tain segregated facilities and a decision holding that the maintenance

of segregated public schools was not unconstitutional. The Com

mission also noted that public sentiment required the maintenance

of segregated facilities.

In Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., the Commission again held that

Section 3 (1 ) was violated by defendant railroad when it offered

inferior facilities for Negroes on its coaches. After noting that it

was proper to apply reason and experience in order to give effect to

the law while causing a minimum amount of friction, the Com

mission said that it would not follow that segregation into cars of

“ equal quality” would constitute a violation of the Act. Here again

the Commission did not cite either the history of the Act or the

intent of the framers as authority for its ruling.

The Commission in Edwards v. Nashville C. & St. L. Ry. Co.,

held that defendants had violated Section 3 (1 ) by providing

unequal facilities. For the proposition that segregation per se was

not unlawful, the Commission simply cited the Councill and Heard

Cases.

Evans v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., did not involve an

interpretation of Section 3 of the Interstate Commerce Act. There

the Commission rejected a claim that a regulation of defendant rail

road requiring segregation in transportation facilities had to be filed

1 0

implications of racial segregation certainly form as proper

a basis for the Commission to reexamine its prior holdings

as it was for the United States Supreme Court.

We submit, therefore, that the Commission is not com

pelled to construe Section 3(1) in the restricted fashion

which defendants urge. Rather the language and legisla

tive history of the Act supports the adoption of the recom

mendations proposed in the Examiner’s report, as well

as those in the Exceptions which we have heretofore filed.

D.

The Separate But Equal Doctrine Reappraised.

The defendants approach the question of the legality

of segregation as if the School Segregation Cases, 347 U. S.

483 (1954), were a special departure from the main stream

of constitutional and legal development on this problem.

On reexamination it is clear that this is not the case insofar

as the Supreme Court of the United States is concerned.

Lower federal and state courts have assumed, at least

since 1896, that the “ separate but equal’ ’ doctrine had been

approved by the Supreme Court as a doctrine of general

with the Commission to comply with Section 6 of the Act, the tariff

clause. The Commission held that if equal accommodations were

furnished, the defendant’s regulation did not change the fare or the

value of the services rendered.

In Jackson v. Seaboard Airlines Ry. Co., decided before Hender

son v. United States, 339 U.. S. 816 (1950), the Commission held that

a carrier’s refusal to give service to a Negro passenger in a dining

car, because whites were occupying the tables reserved for Negro

passengers, violated Section 3 (1 ), but that subsequent regulations

which set aside tables for the exclusive use of Negroes did not con

travene the Act. The Commission noted that no case holding that

segregation per se was unlawful had been called to its attention and

concluded without further citation of authority that the Interstate

Commerce Act did not prohibit segregation.

11

application. And it is possible that the early decisions of

the Commission were based upon this erroneous assump

tion.

The United States Supreme Court, however, has

never given “ separate but equal” the general approbation

and universal application which has been assumed hereto

fore. On the contrary, the “ separate but equal” doctrine

has been utilized by the United States Supreme Court in

a very restricted fashion. It was adopted as applicable to

intrastate transportation in 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537. The doctrine was specifically repudiated by

the Supreme Court in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60,

85 (1917), as not being applicable to housing. Moreover,

except for intrastate commerce the doctrine has never been

applied by the Court in any field whatsoever.

It is true that there is language in several opinions in

volving public education which assumed that the Court had

adopted the “ separate but equal” doctrine as an appro

priate constitutional standard in the field of public educa

tion. In Brown v. Board of Education, supra, the Court

sharply emphasizes the limited and restricted application

of the “ separate but equal” doctrine in the decisions of the

Court. There it said:

“ In the first cases in this Court construing the

Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its

adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all

state-imposed discriminations against the Negro

race. The doctrine of ‘ separate but equal’ did not

make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the

case of Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, involving not

education but transportation. American courts have

since labored with the doctrine for over half a cen

tury. In this Court, there have been six cases in

volving the ‘ separate but equal ’ doctrine in the field

of public education. In Cumming v. County Board

12

of Education, 175 U. S. 528, and Gong Lum v. Rice,

275 U. S. 78, the validity of the doctrine itself was

not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the

graduate school level, inequality was found in that

specific benefits enjoyed by white students were de

nied to Negro students of the same educational quali

fications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305

U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. In none of these cases

was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant

relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v.

Painter, supra, the Court expressly reserved deci

sion on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson

should be held inapplicable to public education.”

In short, the doctrine was never applied in the field of

public education, and now it has been specifically repudi

ated. At best the “ separate but equal” doctrine stands

unrepudiated by the Supreme Court only in the field of

intrastate commerce. And even in that area subsequent

decisions have sapped the doctrine of much of its vitality.4

The doctrine was cited with approval by the Supreme

Court in Chiles v. Chesapeake <& Ohio Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71

(1910), and approbation of the doctrine is implicit in

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941), but the Court

has never applied the “ separate but equal” formula to

interstate commerce. Henderson v. United States, 339

U. S. 816 (1950), which outlawed segregation in railroad

dining cars as violative of the Interstate Commerce Act

constituted, in fact, a repudiation of the Chiles Case. Apart

from the Interstate Commerce Act, at present a carrier

4 See particularly, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 337 (1946);

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 (1948) ; Hender

son v. United States, supra.

13

regulation is invalid as a burden on commerce which

requires Negro passengers to shift their seats in the course

of a through journey in order to conform to a carrier

policy of segregation. Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines,

177 F. 2d 949 (CA 6th 1949); and Chance v. Lambeth, 186

F. 2d 879 (CA 4th 1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 941 (1951).

See also Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 337 (1946).® The

law is not all of a piece in support of the carrier’s right to

segregate, and little can be gained at this late date in

blind adherence to provincial and discredited notions of

a past era.

E.

The Supreme Court Decisions Support the Recommen

dations of the Examiner.

Defendants cite in support of their thesis that the Act

incorporates the “ separate but equal” doctrine, Chiles v.

Chesapeake <& Ohio Ry. Co., supra. The Chiles case

nowhere refers to the Interstate Commerce Act and places

reliance primarily on Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1878),

a case decided many years before the Interstate Commerce

Act was enacted. Chiles can be no authority, therefore, as

to what the Interstate Commerce Act was intended to

accomplish.

Neither in Mitchell v. United States, supra (upon which

defendants placed great reliance), nor in Henderson v.

United States did the United States Supreme Court uphold

a carrier’s practice of segregation. True, there is language

in Mitchell which impliedly supports the “ separate but

equal” thesis, but the holding required that Mitchell and

all other Negroes be afforded an equal opportunity to pur- 5

5 See also Williams v. Carolina Coach Co., I l l F. Supp. 329

(E. D. Va. 1952), which would seem to invalidate any carrier require

ment that passengers change their seats pursuant to the carrier’s

effort to maintain the segregation of the races.

14

chase and occupy available first-class space. This holding

resulted in the ending of efforts by carriers to segregate

passengers in its Pullman cars.

The Henderson case is even more revealing. There the

Court struck down the regulations which would have main

tained segregation in the railroad dining cars, even though

Henderson had not been injured or directly affected by the

regulations in question. The regulations were declared

invalid because of the possibility that they might result in

the denial to some Negro passengers of service, when seats

were available in other parts of the dining car. We stressed

this phase of the opinion in our brief on the merits. We

reiterate it here because if this standard is to be applied,

obviously segregation cannot be maintained by any carrier.

No regulation, which separates persons because of race, can

be devised which would also insure against the possibility

that under all circumstances service will not be denied to

a Negro passenger, although unused facilities are avail

able in the section reserved for white persons. This is the

key to the decision in the Henderson case, and it is error

to consider it a mere reiteration of what was said in the

Mitchell case.

The Henderson case, we submit, decided the same time

as McLaurin and Sweatt, although seemingly within the

“ separate but equal” format, has established standards

which make the maintenance of segregation impossible

under the Interstate Commerce Act, as McLaurin and

Sweatt made impossible the maintenance of segregation in

public graduate and professional schools under the Four

teenth Amendment. See Wilson v. Board of Supervisors,

92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950), aff’d 340 U. S. 909 (1951);

Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Tennessee, 342

U. S. 517 (1952); McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949

(CA 4th 1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 951 (1951); Swanson

v. University of Virginia, Civil Action No. 30 (W. D. Va.

1950) unreported; Payne v. Board of Supervisors, Civil

15

Action No. 894 (E. D. La. 1952) unreported; Foister v.

Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 937 (E. D. La.

1952) unreported; Mitchell v. Board of Regents of Uni

versity of Maryland, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore

City Court 1950) unreported.

The Commission’s attention is also called to Railroad

Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445 (1873), which was an interpre

tation by the United States Supreme Court of a charter

granted by Congress barring a railroad from discriminat

ing against passengers. In this decision, contemporaneous

with the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, segre

gation was struck down as discrimination. The pertinent

facts are described by the Court as follows at page 451:

“ In the enforcement of this regulation, the de

fendant in error, a person of color, having entered

a car appropriated to white ladies, was requested to

leave it and take a seat in another car used for col

ored persons. This she refused to do, and this

refusal resulted in her ejectment by force and with

insult from the car she had first entered.”

At page 452, the Court characterized the railroad’s defense,

that its practice of providing separate accommodations for

Negroes was valid, as an ingenious attempt at evasion.

“ The plaintiff in error contends that it has

literally obeyed the direction, because it has never

excluded this class of persons from the cars, but on

the contrary, has always provided accommodations

for them.”

“ This is an ingenious attempt to evade a com

pliance with the obvious meaning of the require

ment. It is true the words taken literally might

bear the interpretation put upon them by the plain

tiff in error, but evidently Congress did not use

them in any such limited sense. There was no

16

occasion, in legislating for a railroad corporation,

to annex a condition to a grant of power, that the

company should allow colored persons to ride in its

cars. This right had never been refused, nor could

there have been in the mind of anyone an apprehen

sion that such a state of things would ever occur,

for self-interest would clearly induce the carrier—

South as well as North—to transport, if paid for it,

all persons whether white or black, who should de

sire transportation.”

The Court stressed with particularity the fact that the dis

crimination prohibited was discrimination in the use of

the cars, at pages 452-453:

“ It was the discrimination in the use of the cars

on account of color, where slavery obtained, which

was the subject of discussion at the time, and not

the fact that the colored race could not ride in the

cars at all. Congress, in the belief that this discrim

ination was unjust, acted. It told this company, in

substance, that it could extend its road in the Dis

trict as desired, but that this discrimination must

cease, and the colored and white race, in the use of

the cars, be placed on an equality. This condition

it had the right to impose, and in the temper of

Congress at the time, it is manifest the grant could

not have been made without it.”

The regulation was struck down in the Brown Case

because it was felt that discrimination barred by the Con

gress included racial segregation as well as denial of equal

facilities. The Supreme Court has once again come to take

that view of discrimination, and there is little basis for the

Commission’s holding fast to a moribund doctrine whose

life span now in any area seems destined to be short lived.

17

F.

Segregation in Coaches and Waiting Rooms Is Dis

crimination Within the Meaning of 3(1).

Defendants attempt to defend their policy of segrega

tion on the theory that this is what Negro passengers

prefer. Rather, they assert that Negro passengers do not

view these practices as something unwanted—as imposed

upon them against their will and desire. Defendants’

conclusions are contrary to the findings of the most eminent

social scientists and learned students of the American

social order. If there is one thing which students of

American culture are in agreement, it is the fact that segre

gation in public transportation is bitterly resented by

Negroes and is considered a badge of inferiority.6

All that is involved in racial segregation—the signs and

other indicia of race—is maintenance of the myth of a

superior white and an inferior Negro caste, nothing

more, nothing less. There is no other reason for these

practices which result in humiliation and degradation of

Negro passengers who seek merely to ride on the carrier

facilities of the nation on the same bases as any other

citizen. And to defend these practices as catering to the

desires of the Negro passengers is sheer nonsense.

Segregation does not provide equality for anybody. On

the contrary it results in the imposition of indiscriminate

discrimination against both Negro and white passengers.

To paraphrase the Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U. S. 1, 22 (1948), and Sweatt v. Painter at 635, the

indiscriminate imposition of inequalities pursuant to the

enforcement of defendants ’ policies and practices of segre

gation does not achieve that equality which the Interstate

Commerce Act seeks to assure.

6 See Myrdal, American Dilemma, Vol. 1, p. 635 (1944); Johnson,

Pattern of Negro Segregation 270 (1943); Dollard, Caste and Class

In A Southern Town 350 (1937).

18

In Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954), the Supreme

Court said “ [ljiberty under law extends to the full range

of conduct which the individual is free to pursue and it

cannot be restricted except for a proper governmental

objective.” Segregation in interstate commerce is no more

proper as a governmental objective than segregation in

public schools. If the Commission construes Section 3(1)

as according carriers the right to segregate Negro and

white passengers, it will amount to the sanctioning of segre

gation in interstate commerce pursuant to governmental

authority. As such, this will raise serious doubts concern

ing the constitutionality of the Interstate Commerce Act

itself. Clearly such a construction is to be avoided.

Conclusion

For the reasons hereinabove stated, it is respectfully

submitted that the recommendations of the Examiner that

segregation in railroad coaches and railway stations be out

lawed should be adopted. In addition, reason and logic

call for extension of the proposed barrier against segrega

tion to include restaurants operated in railway stations for

the benefit of interstate passengers. Again we respectfully

urge the Commission to adopt the views contained in our

Exceptions in this regard.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Complainants

and Intervenors.

Due Date: February 4, 1955.

19

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have this day served the fore

going document upon all parties of record in this proceed

ing by mailing a copy thereof properly addressed to counsel

for each party of record.

Dated at New York, N. Y., this 3rd day of February,

1955.

R obert L. Carter.