Defendant's Reply to Plaintiffs' Response to Motion to Dismiss or for Summary Judgment and Memorandum in Support

Public Court Documents

December 7, 1992

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Defendant's Reply to Plaintiffs' Response to Motion to Dismiss or for Summary Judgment and Memorandum in Support, 1992. b3980ce1-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/303d0606-8971-47f5-b620-f44bb69efb03/defendants-reply-to-plaintiffs-response-to-motion-to-dismiss-or-for-summary-judgment-and-memorandum-in-support. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

oc ce faa

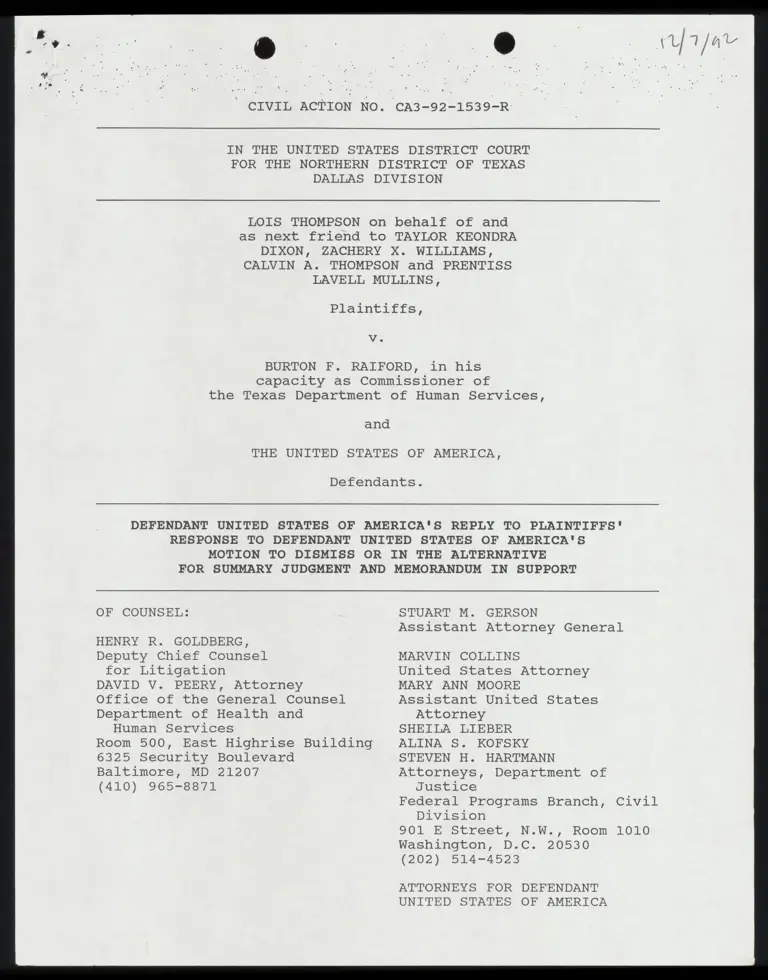

CIVIL ACTION NO. CA3-92-1539-R.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and

as next friend to TAYLOR KEONDRA

DIXON, ZACHERY X. WILLIAMS,

CALVIN A. THOMPSON and PRENTISS

LAVELL MULLINS,

Plaintiffs,

Vv.

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human Services,

and

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendants.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO PLAINTIFFS'

RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S

MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT

OF COUNSEL: STUART M. GERSON

Assistant Attorney General

HENRY R. GOLDBERG,

Deputy Chief Counsel

for Litigation

DAVID V. PEERY, Attorney

Office of the General Counsel

Department of Health and

Human Services

Room 500, East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, MD 21207

(410) 965-8871

MARVIN COLLINS

United States Attorney

MARY ANN MOORE

Assistant United States

Attorney

SHEILA LIEBER

ALINA S. KOFSKY

STEVEN H. HARTMANN

Attorneys, Department of

Justice

Federal Programs Branch, Civil

Division

901 E Street, N.W., Room 1010

Washington, D.C. 20530

{202) 514-4523

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES. vo 0s "a iv is 0 oni iio a =» = ww '&e¢. o ii

1. INTRODUCTION tee "se iv 0 0 in" on laa aiilleilie le Taifie ou oe wi wile 'w 1

IX. BARCUMENT AND AUTHORITIES '@ « ‘0 oo ¢: 0 'a dd 6 a a so sao o5¢ 3

A. The Named Plaintiffs Lack Standing To Maintain

This Action And Their Claims Should Be Dismissed . . . 3

B. The Medicaid Statute Does Not Require Blood

128d MOBS iy iiv of oie son 0i % wie desin a. sivaile wo sie 8

C. Plaintiffs Have An Adequate Bengsy Against

The State Of Texas . . + . * Toe aa dee ee ee 11

D. Plaintiffs' Complaint Should Be Dismissed For

Failure To State Claim Upon Which Relief May Be

Granted Or Alternatively, Summary Judgment Should

Be Granted In Favor Of Federal Defendant . . . . . . . 16

IIT. CONCLUSION ov 1s «elie nv ve gin, oil Tg gia tel glieg go ruie ws 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: PAGE (S)

Allen Vv, Wright, 4680.8. 737 (1984) ois %ei vais a "a uw laiiste wiieian 1

Brown Vv. Sibley, 650 F.2d 760 (5th Clr. 1981) . « « « ¢ ss so 2 so ¢ 7

Coker: v. Sullivan, 902 F.2d 82 (D.C. Cir. 1990). . +. + « «s+» +» 13, 14

Council of and for the Blind, Inc. v. Regan,

7008 F.20 1523 (D.C. Tir. 1083) «0 vv sie a oii nian wi» 14, 18

County of Riverside v. Mclaughlin,

U.S. 111 S.Ct. 1661 (1991) 7. vrs a iy edie a ai 8

Harris V. McRae, 448 U.S. . 297 (1980) «ithe. sos oo » o ‘a wins un #40 oid

Isquith v. Middle South Utilities, Inc.,

S47 F.2d 186 (Sth Cir. 1988) . v skis’ «ivi sis a nin fis o sini 16

Koster v. Webb, 598 F. Supp. 1134 (E.D.N.¥Y. 1983) '. + +. v sw. v'n » « 14

Lewis v. Hegstrom, 767 F.24 1371 (9th Cir. 1985) EE IRE VEAL ha 3

Maine Vv. Thiboutot, 448 U.8.. 1 (1980) is vi « vie wimcnin eo ainw nin + 15

Mitchell v. Johnston, 701 F.2d 337 (5th Cir. 1983) VIERA Cr LA Cl Gey 1.

Washington Legal Foundation v. Alexander,

778 F. SUPP. 67 (D.D.Ce A099) 2, "vy i) eins Tee ere a 2D

Women's Equity Action Leaque ("WEAL)'" wv. Cavazos,

D06 F.20 742 (DeC. CIT. F990) wis + 0s ov aa ou vo wirmin 18

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS:

22 U.8.C. § O00 li ly i i a WE SN we ate ae 2

42 U.8.C. 8 1306AITI(DILBILIVY is ei i ates » wih eataifeing oh WA

42 U.8.C. 8 A083 0 or, Le ah er ey RY Le Ne gy 1, 15

42 U.8.C, 6 1306ALE) oir i. oan I LE se Sl i ed E20

MISCELLANEOUS:

5 Cs

H.R.

H.R.

Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 1366 (1969) li SC Ca TE Sh

Conf. Rep. No. 101-386, 10l1st Cong.

1st Sess. (Nov. 21, 1989), reprinted

in 1990 U.S.C. C.A.N. 3018, 3056 TREE RAV IL SC EE EE FV 1

Rep. No. 101-247, 101st Cong.,

1st Sess. (Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in

1900 DS eCeC ANN. 1906 oe + os vin tn taint sn vie wie wu wwii 10

- Iii -

I.

INTRODUCTION

In response to defendant USA's argument in its Motion to Dismiss

or in the Alternative for Summary Judgment ("Motion to Dismiss") that

named plaintiffs have suffered no injury as a result of the new HCFA

guidelines, and as a result, lack the requisite standing to maintain

an action against the federal defendant, plaintiffs fail to present

any argument -- much less evidence -- to prevent the Court from

dismissing this action. Any injury named plaintiffs may have suffered

under previous HCFA guidelines (which are not challenged here) should

be remedied by the new EPSDT screening provisions which require that

they receive the blood lead tests they seek. In fact, defendant

Raiford has asserted that all Medicaid recipient children in Texas

will now be receiving the blood lead test. Plaintiffs' suggestion

that new class representatives should be chosen once named plaintiffs

receive the blood lead test they seek has been rejected by this

Circuit, which has clearly stated that under such circumstances

plaintiffs' complaint should be dismissed.

In their Response, plaintiffs have also failed to demonstrate

that the plain language of the Medicaid statute, 42 U.S.C. §

1396d(r) (1) (B) (iv), actually requires that one specific type of

laboratory test, the "blood lead test," be used to assess lead levels

in blood. It is inconceivable that Congress intended the phrase "lead

blood level assessment" to mean the very specific "blood lead test,"

and in light of the basic structure and operation of the Medicaid

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -w- Page 1

program, it would be anomalous tor Congress to tell states to use a

specific blood test. The language of the statute, the evidence

available to Congress at the time, and the legislative history support

federal defendant's position that in limited instances, the EP test, a

laboratory test which assesses blood lead levels, or the blood lead

test is permissible under the statute.

Plaintiffs now claim that they are no longer challenging the HCFA

guidelines, but instead seek relief from the federal government's

continued support, financing and encouragement to the states to use

the EP test. Even assuming, arquendo, that the Medicaid statute

specifically requires blood lead testing, the most appropriate avenue

for plaintiffs to seek redress for their alleged injury would be a

suit against the State of Texas, already a defendant, pursuant to 42

U.S.C. § 1983. Such a lawsuit would provide a more adequate remedy

than the sweeping mandatory injunctive relief plaintiffs seek with

respect to the federal defendant, and would ensure that any injury

plaintiffs suffer as a direct result of Texas' alleged failure to

follow the Medicaid statute and administer the blood lead test is

redressed. Plaintiffs have no right to sue the federal government

directly under the Medicaid statute and the only statute that might

otherwise provide them with a cause of action, the Administrative

Procedure Act ("APA"), provides for judicial review of a federal

agency's action only where there is no other adequate remedy in a

court. See 5 U.S.C. § 704. As a result, the Court should dismiss

plaintiffs' claims with respect to federal defendant.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 2

Finally, plaintiffs' attempts to create alleged genuine issues of

material fact in dispute as a way to fend off federal defendant's

alternative motion for summary judgment should be rejected since most

of the "facts" plaintiffs raise are not only immaterial, but also are

intertwined with many of the legal issues. The only issues before the

Court are issues of law -- whether the plaintiffs have standing to

bring this action, and, if they do, whether the Medicaid statute

requires blood lead testing only. As a result, the Court should

reject plaintiffs' suggestion that discovery is needed, and

accordingly, should either dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint for failure

to state a claim, or alternatively, grant summary judgment in favor of

federal defendant as there are no genuine issues of material fact in

dispute.

II.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

A. The Named Plaintiffs Lack Standing To Maintain This Action And

Their Claims Should Be Dismissed

As the federal defendant has previously demonstrated, under the

challenged HCFA guidelines, the four named plaintiffs should be

considered at "high risk" of having elevated blood levels, and should

receive the very blood lead test they seek. See Motion to Dismiss at

24-25; HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(c); Hiscock Declaration at § 14.

These plaintiffs, therefore, will be aided, not injured, by the

application of the new HCFA guidelines. As a result, plaintiffs do

not possess the requisite standing to maintain this action against the

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -w= Page 3

federal defendant, and the Court should dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint

for lack of jurisdiction.

Plaintiffs nevertheless insist that they have been injured since

"(t]he named plaintiffs in this case have been subjected to the EP

test in violation of the statute and were misdiagnosed as a result."

Memorandum in Support of Response at 8. Plaintiffs fail to

acknowledge, however, that the EP test was performed on the four

plaintiff children before the new HCFA guidelines requiring blood lead

tests for all "high risk" children went into effect. See Declaration

of Lois Thompson attached to Plaintiffs' Motion for Temporary

Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction Against The U.S.A. at 1-

3. No injury to plaintiffs can result from the proper application of

the new HCFA guidelines.

Plaintiffs further argue that "[t]he sequence of events in this

case makes clear . . . that the HCFA guidelines have had no effect on

the named plaintiffs to date . . . . [and} {a]ll of the EPSDT children

in the State of Texas are still subject to the use of the EP test even

after the effective date of the HCFA guidelines." Memorandum in

Support of Response at 11. In support of these allegations,

plaintiffs cite to defendant Raiford's answer to § 50 of plaintiffs’

Second Amended Complaint. Although defendant Raiford has admitted

plaintiffs’ allegation that "[o]lnly if a child tests higher than 35 on

the EP test is a blood lead level test administered," see Defendant

Raiford's Answer to Plaintiffs' Second Amended Complaint at 6,

plaintiffs conveniently overlook the latter part of the answer which

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 4

states that "the EP test will be discontinued as a blood lead level

test in November 1992." Id. In fact, defendant Raiford has asserted

that as of October 23, 1992, the State of Texas began performing blood

lead tests for all Texas children who are Medicaid recipients and has

eliminated the use of the EP test altogether. See Defendant Raiford's

Response in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Class Certification

at 2, and Declaration of Bridget Cook at 4-5 attached as Exhibit A

thereto. As a result, all four named plaintiffs, in accordance with

the new HCFA guidelines, should receive the blood lead test.

Moreover, with respect to plaintiff Taylor Dixon, plaintiffs!

arguments once again evidence a lack of understanding of the new HCFA

guidelines. See Memorandum in Support of Response at 8, 9. In

accordance with the challenged guidelines, plaintiff Dixon should

receive a verbal assessment which should determine that she is at

"high risk" despite her 9 ug/dL blood lead level result.! Even

assuming that the EPSDT provider took into account plaintiff Dixon's

previous blood lead test result of 9 ug/dL, the HCFA guidelines

provide that "[s]ubsequent verbal risk assessments can change a

child's risk category. Any information suggesting increased lead

exposure for previously low risk children must be followed up with a

blood lead test." HCFA Guidelines at § 5123.2 (b) (emphasis added).

I The blood lead test which plaintiff Dixon received on

May 5, 1992, before the new HCFA guidelines went into effect, was

administered at the request of her attorney and not as part of

the routine EPSDT screening in any event. See Plaintiffs' Second

Amended Complaint at 12 n.2.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 5

As a result, plaintiffs' assertion that Taylor Dixon "will not receive

a blood lead test even under the new HCFA guidelines," see Memorandum

in Support of Response at 8, is simply not supported by the plain

language of the new HCFA guidelines.’

Plaintiffs wrongly assert that if the named plaintiffs receive

the blood lead test, thereby rendering the case moot, other class

representatives may be allowed to replace them. Memorandum in Support

of Response at 11. This is statement is simply not supported by the

case law in this Circuit. Since plaintiffs should be receiving the

blood lead test in accordance with the new HCFA guidelines, and the

State of Texas administers such tests for all EPSDT children in the

state, plaintiffs have in fact suffered no injury, and as a result

never have had a valid claim against federal defendant.

This is not a situation where plaintiffs once had a valid claim

as to federal defendant but their claim subsequently became moot. In

fact, plaintiffs' claim as to federal defendant is moot ab initio,

even before a class has been certified by the Court, and as a result,

plaintiffs' reliance on the cases cited in County of Riverside v.

McLaughlin, uv.S. 111 S. Ct. 1661, 1667 (1991) ‘is misplaced.

Once the Court concludes that plaintiffs, as the proposed class

2 It should also be noted that based on recent blood lead

test results for plaintiffs Zachary Williams (7 pg/dL) and Taylor

Dixon (9 pg/dL), see Declaration of Lois Thompson, they are not

considered to be lead-poisoned according to the 1991 CDC J

Statement, which recommends no follow-up or intervention

treatment for those children with blood lead levels below 10

ng/dL. See 1991 CDC Statement at 3 (attached as Exhibit 1 to

Binder Declaration).

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 6

representatives, lack individual standing, "the proper procedure . .

is to dismiss the complaint, not to deny the class for inadequate

representation or to allow other class representatives to step

forward." Brown v. Sibley, 650 F.24 760, 771 (5th Cir. 1981)

(emphasis added). As a result, contrary to plaintiffs' suggestion

that new class representatives should be chosen once named plaintiffs

receive the blood lead test they seek, this Circuit has clearly stated

that plaintiffs' complaint must be dismissed. Id.

In addition, the requested permanent injunctive relief plaintiffs

seek would not redress any alleged harm to plaintiffs.’ In order to

establish redressability, plaintiffs must demonstrate that "relief

from the [alleged] injury [is] 'likely' to follow from a favorable

decision." Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 750 (1884). Plaintiffs

claim that they seek to enjoin the federal government from supporting,

financing and encouraging the states' use of the EP test as a

screening device for childhood lead poisoning. Memorandum in Support

of Response at 9-10.%* Yet the four named plaintiffs will fare no

3 Since plaintiffs suddenly, and without explanation,

withdrew their motions for preliminary injunction against

defendant USA and defendant Raiford on December 3, 1992, see

letter to the Court from Laura B. Beshara and Michael M. Daniel

dated December 3, 1992, federal defendant will not address any

issues related to the preliminary injunctive relief previously

sought by plaintiffs.

4 It is difficult to reconcile, much less comprehend,

plaintiffs' contradictory assertions that "the HCFA guidelines

are not the subject of the lawsuit," see Memorandum in Support of

Response at 12, "that plaintiffs are challenging more than the

HCFA guidelines," see Memorandum in Support of Response at 9, and

that "plaintiffs are not challenging all of the 9/19/92

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -w Page 7

better as a result of the granting of this injunctive relief. The

injury of which they complain -- i.e., the State of Texas' alleged

failure to perform a blood lead test and appropriate lead poisoning

intervention -- cannot be redressed by enjoining the September 1992

HCFA guidelines. To the contrary, those guidelines require that

plaintiffs receive a blood lead test and appropriate intervention

under the circumstances alleged by plaintiffs, and granting the relief

sought by plaintiffs from defendant USA would offer them no additional

relief.

B. The Medicaid Statute Does Not Require Blood Lead Tests

In their Response, plaintiffs incorrectly assert that the "plain

and unambiguous language [of 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(B) (iv) ]" requires

a blood lead test. Memorandum in Support of Response at 1-2. Section

1396d(r) defines EPSDT screening services to include " (iv) laboratory

tests (including lead blood level assessment appropriate for age and

risk factors)." On its face, § 1396d4(r) (1) (B) (iv) clearly does not

require a specific "blood lead test" as plaintiffs contend, and only

speaks of "laboratory tests" in general. It is inconceivable that

Congress intended the phrase "lead blood level assessment" to mean the

very specific "blood lead test." Given the basic structure and

operation of the Medicaid program, which gives states latitude in

determining the services to be provided, it would be anomalous for

Congress to tell states not only that children's lead levels must be

guidelines" see Memorandum in Support of Response at 10.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 8

assessed, but also to mandate use of the blood lead test in

particular.

Plaintiffs' attempt to demonstrate that the July 1988 HHS Report

"The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United

States: A Report to Congress" ("1988 HHS Report") supports the plain

wording of the statute so as to require "blood lead tests" is baseless

and should be rejected. Memorandum in Support of Response at 4-5.

Nowhere does the 1988 HHS Report recommend use of the blood lead test

as the preferred test for measuring lead levels. In fact, the only

statement the 1988 HHS Report makes is that "[s]ince current EP tests,

used as the initial screen, cannot accurately identify children with

blood lead levels below 25 ug/dL, screening tests that will identify

children with lower blood-lead levels must be developed." See 1988

HHS Report at II-9 (Exhibit B to Declaration of Paul Mushak, PhD.,

attached to Brief Amici Curiae in Opposition to Defendant United

States of America's Alternative Motions to Dismiss and for Summary

Judgment) (emphasis added). The Report, therefore, only suggested to

Congress that a more accurate test must be developed, but certainly

did not suggest use of the "blood lead test" per se. Moreover, at the

time Congress considered and passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation

Act of 1989 ("OBRA 89"), the most recent pronouncement on lead

poisoning from the CDC, issued in 1985, recommended the EP test as the

screening test of choice. See 1988 HHS Report at 3 (relying on 1985

CDC Statement "which identified a Pb-B [blood lead] level of 25 ug/dL

along with an elevated erythrocyte protoporphyrin level (EP) as

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -w- page 9

evidence of early toxicity.").

Plaintiffs also fail to recognize that the EP test does detect

levels of lead in blood. Memorandum in Support of Response at 2, 3,

4. As federal defendant has previously demonstrated, the EP test,

which is a "laboratory test," also assesses lead levels in blood,

albeit indirectly, since it measures the chemical erythrocyte

protoporphyrin whose level in blood rises when lead is present.

Binder Declaration at q 14.

The legislative history of OBRA 89 fails to support plaintiffs’

argument that the statute requires only specific "blood lead tests."

In fact, it furnishes no guidance regarding types of blood tests or

other methods for screening, and as a result, lends support to federal

defendant's position that either the EP test or the blood lead test is

permissible under the statute. The House Report simply articulated

the eventual statutory language: "[u]nder the Committee bill,

screening services must, at a minimum, include . . . (4) laboratory

tests (including blood lead level assessment appropriate for age and

risk factors) . . . ." See H.R. Rep. NO. 101-247, 101st Cong., 1st

Sess. (Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in 1990 U.S8.C.C.A.N. 1906, 2125,

The Conference Report to OBRA 89, § 6403, now 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r),

stated that the legislation "[c]odifies the current regulations on

minimum components of EPSDT screening and treatment, with minor

changes . . . . [and] [p]rovides that "screenings must include blood

testing when appropriate, as well as health education." H.R. Conf.

Rep. No. 101-386, 101st Cong. 1st Sess. (Nov. 21, 1989), reprinted in

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 10

1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 3018, 3056 (emphasis added). Any suggestion that

Congress intended the phrase "lead blood level assessment" to mean

solely "blood lead test" is contrary to the language of the statute,

the evidence available to Congress, and legislative history, and

should be rejected.

C. Plaintiffs Have An Adequate Remedy Against The State Of Texas

Plaintiffs now claim that they are no longer challenging the HCFA

guidelines, but instead seek relief from the federal government's

continued support, financing and encouragement to the states to use

the EP test. Assuming, argquendo, that the Medicaid statute requires

blood lead testing, the most appropriate avenue for plaintiffs to seek

redress for their injury would be a suit solely against the State of

Texas pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Such a lawsuit would provide a

more adequate remedy than the sweeping mandatory injunctive relief

plaintiffs seek with respect to the federal defendant, and would

ensure that any injury plaintiffs suffer as a direct result of Texas’

alleged failure to follow the Medicaid statute is redressed.

Plaintiffs have no right to sue the federal government directly under

the Medicaid statute and the only statute that might otherwise provide

them with a cause of action, the Administrative Procedure Act ("APA"),

provides for judicial review of a federal agency's action only where

there is no other adequate remedy in a court. See 5 U.S.C. § 704. As

a result, plaintiffs' claims with respect to federal defendant should

be dismissed.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT == Dage 11

Even assuming that plaintiffs obtain the relief from federal

defendant of requiring HCFA to issue guidelines that require the

states' use of only the blood lead test, there is no assurance that

the State of Texas would comply with such revised HCFA guidelines.’

Plaintiffs themselves recognize this when they argue that "the 9/19/92

HCFA guidelines . . . are not mandatory or otherwise binding on the

states." Memcrandum in Support of Response at 9. Within the broad

framework of federal requirements and oversight, the states operate

their individual programs in accordance with state rules and criteria

that vary widely. The day-to-day administration of state Medicaid

programs is performed by the states, not by the federal government.

As a result, "[a]s long as a State complies with the requirements of

the Act, it has wide discretion in administering its local program."

lewis v. Heqgstrom, 767 F.24 1371, 1373 (9th Cir. 1985) (citations

omitted). As a general rule, the federal government ensures systemic

compliance with the Medicaid statute, see generally Harris v. McRae,

448 U.S. 297 (1980). Because of this relationship with the states, as

well as the federal government's limited resources, federal defendant

is not in a position to know whether the State of Texas is following

its guidelines with respect to every Medicaid-eligible child. The

relief requested against the federal defendant would fail to redress

> In any event, nothing in the Medicaid statutory scheme

requires HCFA to issue any guidelines. Cf. 42 U.S.C. § 902

(Secretary of HHS vested authority to administer Title XIX); 49

Fed. Reg. 35, 248-49 (Sept. 6, 1984) (Secretary of HHS delegating

to HCFA Administrator the authority to administer Title XIX).

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -w= "Page 12

any alleged injuries plaintiffs claim they have suffered; however, if

plaintiffs are correct in their view that the Medicaid statute itself

requires use of the blood lead test, they could more appropriately and

efficiently obtain the relief they seek from the State of Texas.

Courts are frequently faced with cases, such as this one, in

which a plaintiff alleges direct injury from a third party, but sues

the government for failing either to prevent the injury or to take

enforcement action against the third party. Just as frequently,

courts dismiss such actions against the government when the plaintiff

has an adequate remedy against the third party. Even if direct

lawsuits are not a superior remedy to the broad relief requested by

plaintiffs, judicial review is precluded because direct lawsuits are

nevertheless an adequate remedy.

In Coker v. Sullivan, 902 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1990), for example,

homeless families and advocacy organizations sued HHS and sought an

order requiring it to enforce state Emergency Assistance plans. HHS

regulations required compliance with these plans and authorized

withholding of federal payments to states that failed to comply with

federal requirements. Noting that "if other remedies are adequate,

federal courts will not oversee the overseer," id. at 89, the D.C.

Circuit held that plaintiffs had an adequate remedy for alleged

deficiencies in state plans by suing the states directly. Id. at 90.

Indeed, in an observation equally appropriate for this case, the court

noted:

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 13

Actions directly against the states are not merely

adequate; they are also more suitable avenues for

plaintiffs to pursue the relief they seek. The

states are the immediate cause of the injuries of

which [plaintiffs] complain; these plaintiffs ask

HHS not to refrain from harming them but rather to

cure their state-created injuries.

d. at 90 (footnote omitted). And, as the Coker court recognized, at

least one federal court, in Koster v. Webb, 598 F. Supp. 1134

(E.D.N.Y. 1983), has held that plaintiffs have a § 1983 action against

a state to force its compliance with that state's Emergency Assistance

plan provisions. Id.

In Council of and for the Blind, Inc. v. Regan, 709 F.24 1521

(D.C. Cir. 1983), a group of organizations and individuals maintained

that the Office of Revenue Sharing (ORS) was not adequately monitoring

local governments' compliance with the antidiscrimination provisions

of the Revenue Sharing Act. The litigants sought broad-based,

nationwide relief requiring extensive judicial supervision of the

ORS's enforcement of discrimination claims. Id. at 1524-25. The

court held, however, that because the Revenue Sharing Act provided an

adequate alternative remedy against the non-complying local

governments when the ORS failed to act, the ORS's failure to process

administrative complaints was not subject to judicial review under the

APA. Id. at 1531. As in the present case, the alternative remedies

available in Council of and for the Blind were individual lawsuits

directly against the entities that allegedly violated the law. The

court explicitly held that since such lawsuits were "adequate to

redress the discrimination allegedly encountered by appellants" it did

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 14

not matter whether this individualized relief would provide the most

effective remedy. Id. at 1532-1533 (emphasis in original).

Similarly, in Women's Equity Action Leaque ("WEAL)" v. Cavazos,

906 F.2d 742, 751 (D.C. Cir. 1990), plaintiffs filed suit against the

Secretary of Education for an order requiring him to monitor and

enforce anti-discrimination laws against educational institutions that

received federal funding. Relying on Council of and for the Blind v.

Regan, 70° F.24 1521, 1531-33 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (en banc), the court

held that suits against individual educational institutions served as

an adequate alternative remedy and dismissed APA claims against the

Secretary. WEAL, 906 F.2d at 750-51.° See also Washington Legal

Foundation v. Alexander, 778 F. Supp. 67, 70-72 (D.D.C. 1991).

The case plaintiffs themselves cite, Mitchell v. Johnston, 701

F.2d 337 (5th Cir. 1983), is precisely illustrative of this adequate

remedy. In Mitchell, the plaintiffs alleged that Texas had deprived

them of their statutorily guaranteed rights under the EPSDT progran,

and sued the State of Texas, not the federal government, pursuant to

42 U.S.C. § 1983. Id. at 344. The Mitchell court quoted the holding

of Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980), that "suits in federal court

under section 1983 are proper to secure compliance with the provisions

6 Plaintiffs in both Coker and WEAL argued that individual

suits could not provide the systematic relief that federal

enforcement could. The D.C. Circuit rejected both claims,

observing in Coker that "the critical injury plaintiffs allege is

the denial of EA to eligible families, and this injury can be

redressed without any relief against the federal government."

Coker, 902 F.2d at 90 n.5; WEAL, 206 F.24 at 751.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 15

of the Social Security Act on the part of tho partioioating states."

14.

Plaintiffs here may pursue their claim that the Medicaid statute

requires use of the blood lead test through their current § 1983 suit

against the State of Texas. If plaintiffs are correct in their view,

this Court could grant relief as to the State of Texas, which would

fully redress the alleged injuries asserted by plaintiffs. Thus, a

direct action against the state is not merely an "adequate" remedy

within the meaning of the APA, it is the superior remedy in this

context.

D. Plaintiffs' Complaint Should Be Dismissed For Failure To State

Claim Upon Which Relief May Be Granted Or Alternatively, Summary

Judgment Should Be Granted In Favor Of Federal Defendant

A court has discretion, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 12 (b) (6), to consider or reject "matters outside the

pleadings" such as affidavits, and it may or may not elect to convert

a Rule 12(b) (6) motion into a motion for summary judgment pursuant to

Rule 56. See Isquith v. Middle South Utilities, Inc., 847 F.2d 186,

193 n.3 (5th: Cir. 1988) (citing 5 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 1366 (1969)). Accordingly, the Court has the

discretion to exclude the Hiscock and Binder declarations accompanying

federal defendant's 12(b) (6) motion and simply dismiss this suit based

on Plaintiffs' Second Amended Complaint and the attachments thereto.’

’ In any event, federal defendant's motion to dismiss

pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b) (1), based on

the argument that named plaintiffs' claims should be dismissed

with respect to defendant USA because they have not suffered any

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 16

Fvsh it the Court, in its discretion. chooses to coniider the Hiscock

and Binder declarations in deciding the legal issues before it,

thereby converting defendant USA's motion to dismiss into a motion for

summary judgment pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56,

summary judgment should be granted in federal defendant's favor as

there are no genuine issues of material fact, notwithstanding

plaintiffs' allegations to the contrary, since defendant USA is

entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

Plaintiffs' attempts to demonstrate that there are genuine issues

of material fact in dispute should be rejected. In fact, most of the

"facts" plaintiffs raise are not only immaterial, but also are

intertwined with many of the legal issues discussed supra. Moreover,

many of the "factual" issues plaintiffs raise evidence a lack of

understanding of the new HCFA guidelines, 9 1.1-1.3 (plaintiff Taylor

Dixon should receive a blood lead test under the new HCFA guidelines

based on the verbal assessment), q 1.7 (the guidelines authorize use

of the EP test for "low risk" children only, and at the option of the

EPSDT provider; this was clarified in the All States Letter issued on

October 15, 1992, gee Fxhibit 3 to Hiscock Declaration), 99 4.1-4.3

(the new HCFA guidelines specifically acknowledge in the Preamble that

the EP test is not sensitive for blood lead levels below 25 ug/dL), 9

5 (cost is nowhere mentioned in the HCFA guidelines as a rationale for

injury and therefore lack standing to sue, does not depend on the

Binder and Hiscock Declarations, and should not be converted into

a motion for summary judgment.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 17

: the continued use of the EP test, And in fact. HCPA ne tated ih tts

October 15, 1992 All States Letter that it will share in the cost of

blood lead testing of all EPSDT children, regardless of risk level), ¢

10 (the new HCFA guidelines stress that blood lead testing is the

screening test of choice); or are irrelevant since they encompass

events that occurred before the new HCFA guidelines went into effect,

see § 1.5 (State of Texas' failure to onbly with previous HCFA

guidelines which was subsequently corrected in 1991).

Plaintiffs correctly recognize that the only issues before the

Court are issues of law -- whether the plaintiffs have standing to

bring this action, and, if they do, whether the Medicaid statute

requires blood lead testing only. See Response at 13. As a result,

the Court should reject plaintiffs' suggestion that any discovery is

needed, and accordingly, should either dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint

for failure to state a claim, or alternatively, grant summary judgment

in favor of federal defendant as there are no genuine issues of

material fact in dispute.

111.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and for the reasons stated in

defendant USA's Corrected Motion to Dismiss or in the Alternative for

Summary Judgment and Memorandum in Support, the Court should dismiss

plaintiffs' Complaint in its entirety because plaintiffs have failed

to demonstrate any injury and therefore lack standing to bring this

action. Alternatively, the Court should dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 18

- . . i are . . : * : iin & . * oe oo in i

a b " Vie . 4 Ear ’ ary - . Lg >t EL Dy . A Li

v ~

tor. fAL10Te to State a Srath Pursuant to Federal Rule of .Civil

Procedure 12(b) (6) against federal defendant under the Medicaid

statute, or because there is no genuine issue as to any material fact,

grant summary judgment in favor of defendant USA in accordance with

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56.

Dated: December 7, 1992 Respectfully submitted,

STUART M. GERSON

Assistant Attorney General

MARVIN COLLINS

United States Attorney

MARY ANN MOORE

Assistant United States Attorney

Texas Bar No. 14360400

hf

reson [haw

SHEILA LIEBER

ALINA S. KOFSKY | 0)

= 3 EES We

DIC mn. Hoovecumme fugit

I

STEVEN H. HARTMANN

Attorneys, Department of Justice

Federal Programs Branch, Civil

Division

901 E Street, N.W., Room 1010

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 514-4523

(202) 616-8470 (Fax #)

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -= Page 19

} » i a ks ht A : AE 9

OF COUNSEL:

HENRY R. GOLDBERG, Deputy Chief

Counsel for Litigation

DAVID V. PEERY, Attorney

Office of the General Counsel

Department of Health and

Human Services

Room 500, East Highrise Building

6325 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, MD 21207

(410) 965-8871

(410) 966-5187 (Fax #)

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -~w Page 20

>

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 7th day of December, 1992, a copy

of Defendant United States of America's Reply to Plaintiffs' Response

to Defendant United States of America's Motion to Dismiss. or in the

Alternative for Summary Judgment and Memorandum in Support, was served

via first class mail, postage prepaid upon:

Laura B. Beshara

Michael M. Daniel

MICHAEL M. DANIEL, P.C.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226-1637

Edwin N. Horne

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

State of Texas

P.O. Box 12548

Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

Bill Lann Lee

Kirsten D. Levingston

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

315 West Ninth Street, Suite 308

Los Angeles, California 90015

ALINA S. KOFSKY [) 3

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S REPLY TO

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- Page 21