Evans v. Jeff D. Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

September 6, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Jeff D. Brief for Respondents, 1985. 2d94d135-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3066ca1a-25f4-4fdc-939a-e97148442304/evans-v-jeff-d-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

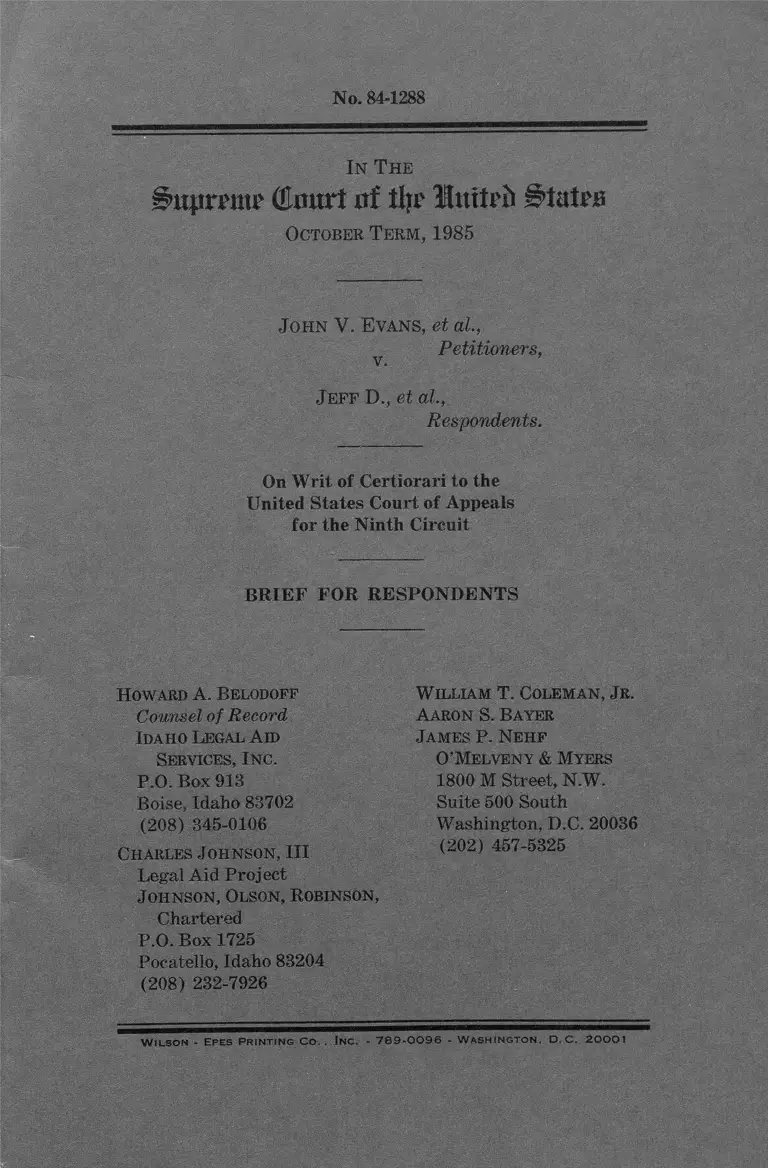

No. 84-1288

In T he

(Umtrt at % Irnfrii States

October T erm , 1985

John V. Evans, et a l,

Petitioners,v.

Jeff D„, et a l,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Charles Johnson, III <202) 457-5325

Legal Aid Project

Johnson, Olson, Robinson,

Chartered

P.O. Box 1725

Pocatello, Idaho 83204

(208) 232-7926

Howard A. Belgdoff

Counsel of Record

Idaho Legal A id

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.

Aaron S. Bater

James P. Nehf

Services, Inc.

P.O. Box 913

Boise, Idaho 83702

(208) 345-0106

O’Melveny & Myers

1800 M Street, N.W.

Suite 500 South

Washington, D.C. 20036

W I L S O N - E P E S P R I N T I N G C O . . INC. - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W A S H I N G T O N , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

QUESTION PRESENTED

May a court, consistent with the Civil Rights Attor

ney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, and the

federal Constitution, enforce a complete waiver of plain

tiffs’ right to costs and attorney’s fees under § 1988,

where the waiver is exacted by state defendants on the

eve of trial as a condition to a settlement providing sub

stantial injunctive relief on the merits,

(i)

QUESTION PRESENTED .......................-..................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS .............. ................................... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES -........................................ v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE....... ............ ...................- 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ---------------- ------ ---------- 7

ARGUMENT.............................................„ ______________ 12

I. THIS CASE CONCERNS COERCIVE RE

QUESTS FOR FEE WAIVERS IN CIVIL

RIGHTS CASES, NOT A PER SE RULE

BARRING SIMULTANEOUS NEGOTIA

TION OF THE MERITS AND ATTORNEY’S

F E E S __ ____ _________ ___- ............ ............ .......... 12

II. IN ENACTING SECTION 1988, CONGRESS

DETERMINED THAT AWARDS OF ATTOR

NEY’S FEES WERE ESSENTIAL TO PRI

VATE ENFORCEMENT OF CIVIL RIGHTS

LAW S........................................ ......................... ....... 15

III. PETITIONERS WERE ABLE TO EXACT A

FEE WAIVER BY IMPROPERLY CREAT

ING AND EXPLOITING A CONFLICT OF

INTEREST BETWEEN RESPONDENTS

AND THEIR COUNSEL ___________________ 18

IV. THE COURT OF APPEALS PROPERLY IN

VALIDATED THE FEE WAIVER AS CON

TRARY TO SECTION 1988 AND THE PUB

LIC POLICIES IT EMBODIES ........................... 24

A. The Fee Waiver In This Case Contravened

Section 1988 And Its Underlying Purposes,

And The Court Of Appeals Correctly Invali

dated It ________ ___________________________ 24

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

(iii)

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

B. Petitioners’ Alternatives To The Approach

Of The Court Of Appeals Would Not Re

solve The Problems Posed By The Coerced

Fee Waiver ...... ............. ............................ ........ 30

C. The Court Of Appeals Correctly Declined

To Invalidate The Entire Settlement Agree

ment ----------------— ..........- ............ ...............— 33

V. BARRING COERCED FEE WAIVERS

WOULD NOT INTERFERE WITH THE

LEGITIMATE INTERESTS OF DEFEND

ANTS IN SETTLING CIVIL RIGHTS SUITS.. 35

CONCLUSION ....... ............ .................. .............................. 39

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Soci

ety, 421 U.S. 240 (1975) ________ _____________ 15

Blum v. Stenson, 104 S. Ct. 1541 (1984) — --- ------ 37

Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817 (1977 )..... ........... 24

Boyd v. Bechtel Corp., 485 F. Supp. 610 (N.D. Cal.

1979) .............. ................................ - ....................... .. 30

Chicano Police Officer’s Association v. Stover, 624

F.2d 127 (10th Cir. 1980)_____________________ 38

Clanton v. Allied Chemical Corp., 409 F. Supp.

282 (E.D. Va. 1976).-_____ 26

Cleveland Board of Education v. Loudermill, 105

S. Ct. 1487 (1985) ..... ................ ..................... .. 35

Cooper v. Singer, 719 F.2d 1496 (10th Cir. 1983).. 17,

28-29, 30

Delta Air Lines, Inc. v. August, 450 U.S. 346

(1981)_ _________________________ ____ _____20

Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477 (1981)............ 20

El Club Del Barrio, Inc. v. United Community

Corps., 735 F.2d 98 (3d Cir. 1984)..................... 28, 34

Foster v. Boise-Cascade, Inc., 420 F. Supp. 674

(S.D. Tex. 1976), aff’d, 577 F.2d 335 (5th Cir.

1978) (per curiam )_________ _____ ___________ 30

Freeman v. B&B Associates, 595 F. Supp. 1338

(D.D.C. 1984), appeal docketed, No. 85-5239

(D.C. Cir. Mar. 11, 1985) ............................... .. 19, 20

Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d 1268 (5th Cir. 1980).... 29

Gillespie v. Brewer, 602 F. Supp. 218 (N.D. W. Va.

1985) ..........................................................10, 21, 28, 30, 33

Gram v. Bank of Louisiana, 691 F.2d 728 (5th Cir.

1982) ______________ __________________ ___ _ 38

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983) ....9, 32, 34-35,

37

Hutto v. Finny, 437 U.S. 678 (1978)_____________ 32

James v. Home Construction Co. of Mobile, 689

F.2d 1357 (11th Cir. 1982) ___________________ 21, 28

Jeff D. v. Evans, 743 F.2d 648 (9th Cir. 1984)— passim

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969)................... 24

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Jones v. Amalgamated Warbasse Houses, Inc.,

721 F.2d 881 (2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 104

S. Ct. 1929 (1984) ______________ ___ ,....10,11, 30, 33

Lazar v. Pierce, 757 F.2d 435 (1st Cir. 1985)____ 20-21,

25, 29

Leeds v. Watson, 630 F.2d 674 (9th Cir. 1980).- 17

Lefkowitz v. Turley, 414 U.S. 70 (1973)_________ 20

Leisner v. New York Telephone Co., 398 F. Supp.

1140 (S.D.N.Y. 1974) _________________________ 26

Lisa F. v. Snider, 561 F. Supp. 724 (N.D. Ind.

1983) ....... ......................................... ........................- 28

Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122 (1980) .................... . 9, 84

McBrearty v. United States Taxpayers Union,

668 F.2d 450 (8th Cir. 1982) (per curiam).... 10,26

Mid-Hudson Legal Services, Inc. v. G&U, Inc.,

578 F.2d 34 (2d Cir. 1978) ___________________ 29

Mitchell v. Johnston, 701 F.2d 337 (5th Cir.

1983)......... ..................................................... ............ 28

Moore v. National Association of Securities Deal

ers, Inc., 762 F.2d 1093 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (peti

tion for rehearing pending)------- --------------------- 20, 29

Nadeau v. Helgemoe, 581 F.2d 275 (1st Cir.

1978) .................. ........................... ............ .............. . 34-35

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S.

54 (1980) .................................................... .............. 17

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400 (1968) (per curiam )________ .______ 17,34

Obin v. District No. 9 International Association

of Machinists, 651 F.2d 574 (8th Cir. 1981).... 21

Prandini v. National Tea Co., 557 F.2d 1015 (3d

Cir. 1977)_______ ____ ,________ __________ _____ 7

Regalado v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D. 447 (D. 111. 1978).. 21

Sanchez v. Schtvartz, 688 F.2d 503 (7th Cir.

1982)........ ............................................. ..................... 29

Shadis v. Beal, 685 F.2d 824 (3d Cir.), cert, de

nied, 459 U.S. 970 (1982) .....................10, 11, 27-28, 33

White v. New Hampshire Department of Employ

ment Security, 455 U.S. 445 (1982)___________ 21, 36

Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235 (1970).... ........... 24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

STATUTES AND RULES Page

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1982)................................. .........passim

Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, 42

U.S.C. §§ 1997-1997j (1982) ______ _____ ____ _ 17

Equal Access to Justice Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2412

(1982).. .................................. ............ ......................... 36

28 U.S.C. § 2412(d) (1) ( B ) _________________ 36

Legal Services Corporation Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2996-

2996? (1982) ...................... ............... ........................ 3

42 U.S.C. § 2996(6) _____________ 19

42 U.S.C. § 2996f (b) (1) ............. ............. ........ 3

28 U.S.C. § 1927 (1982) ................................... .........- 38

45 C.F.R. § 1609 (1984)_____ ________ ____________ 3

Fed. R. Civ. P. 1 1 ___ ___ _________________ ______ 38

Fed. R. Civ. P.12 (b ) (6 ) ________ ________________ 38

Fed. R. Civ. P. 16 ............................... ...................... . 31

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 ......... ......... ............. ........... ........ 7,19

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 ( e ) ........... ................ ............... ........6, 31, 34

Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 ...... ............. .................... .................. 38

Fed.R. Civ. P. 59 (e )_____________________________ 21

Fed. R. Civ. P. 68 __________________i...................... 20

LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS

S. Rep. No. 416, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979), re

printed in 1980 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 787.. 17

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 5908 ...9-10,15, 16

32, 34, 38

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976).. 9, 15,

16-17, 34

MODEL CODE AND RULES

Model Code of Professional Responsibility

EC 5 -1_____ _________ ____ ________ _________ ___ 18

EC 7-7 .........- .............. ............................. .......- ............ 18, 31

EC 7 -9___ ______ _______________ _____ ___________ 18

EC 7-12______ ____ _________________ _____________ 19

EC 7-14______________ ____ ______________________ 22

DR-1-102 (A ) (5) .................. .......... ................ .............. 22

via

Model Rules of Professional Conduct

Model Rule 1.2 ( a ) ......................................... ................ 18, 31

Model Rule 1.7(b) ............. .................. ........ ................ 18

Model Rule 1.14.............................................................. 19

BAR OPINIONS

Committee on Professional and Judicial Ethics of

the New York City Bar Association, Op. No.

80-94, reprinted in 36 Record of New York City

Bar Assoc. 507 (1981) .................... ,...................... 22

Committee on Professional and Judicial Ethics of

the New York City Bar Association, Op. No.

82-80 (1984)___________ __________________ ___ 37

District of Columbia Bar Legal Ethics Committee,

Op. No. 147, reprinted in 113 Daily Wash. Law

Rep. 389 (1985) ...... ............. ........................... . 22

Grievance Commission of Board of Overseers of

the Bar of Maine, Op. No. 17 (1981) _________ 22

State Bar of Georgia, Op. No. 39, reprinted in 10

Georgia State Bar News 5 (1984) ______ _____ 22

MISCELLANEOUS

Calhoun, Attorney-Client Conflicts of Interest and

the Concept of Non-Negotiable Fee Awards Un

der Y2 U.S.C. § 1988, 55 Colo. L. Rev. 341

(1984) ..................................... .................................... 14,31

Comment, Settlement Offers Conditioned Upon

Waiver of Attorneys’ Fees: Policy, Legal and

Ethical Considerations, 131 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793

(1983) ..................... ............... ....................... 14

6A A. Corbin, Contracts (1962 & Supp. 1984)____ 26-27

Fee Waiver Requests Unethical: Bar Opinion, 68

A.B.A.J. 23 (1982) ............ ............ ........................ 25

Final Subcommittee Report of the Committee on

Attorney’s Fees of the Judicial Conference of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Dis

trict of Columbia Circuit, reprinted in 13 Bar

Rep. 4 (1984) ..................................................... . 23-24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

IX

Kraus, Ethical and Legal Concerns in Compelling

the Waiver of Attorney’s Fees by Civil Rights

Litigants in Exchange for Favorable Settle

ment of Cases Under the Civil Rights Attorney’s

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 29 Vill. L. Rev. 597

(1984) ______ ____ __ ________ ________14, 25-26

Restatement (Second) of Contracts (1981) .........10,27,33

Wolfram, The Second Set of Players: Lawyers,

Fee Shifting, and the Limits of Professional

Discipline, 47 Law & Contemp. Probs. 293

(1984)............................................................... 14, 28, 33, 34

7A C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure (1972)........................... ......................... . 31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—-Continued

Page

In T he

Bnpmm (Emtrf of %

October T erm , 1985

No. 84-1288

John V. Evans, et a l,

Petitioners,

Jeff D., et ah,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondents, a class of over 2,000 indigent children

from the State of Idaho, suffer from emotional and men

tal handicaps and are institutionalized or otherwise

placed in petitioners’ custody.1 Due to petitioners’ fail

ure to provide appropriate mental health services, many

of these children were confined in adult psychiatric

wards of state hospitals, including the facilities at State

Hospital South ( “ SHS” ), or in out-of-state treatment

institutions located thousands of miles from their homes

and families. Joint Appendix ( “J.A.” ) 5, 6. Most of the

children suffer from conditions that could be success

fully treated by appropriate mental health care in the

1 Petitioners are the Governor of the State of Idaho, the Director

of the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, and two officials

of the Adult State Mental Hospital, State Hospital South.

2

community rather than by placement in adult psychia

tric institutions or out-of-state facilities. J.A. 65.

When this suit was filed the class members were not

receiving the minimal educational or mental health serv

ices required by law. SHS did not have a child psy

chiatrist or a licensed specialist in child psychology on

its staff. J.A. 72. In fact, SHS had no employees with

the experience or qualifications to provide specialized

treatment or services to emotionally and mentally dis

turbed children. J.A. 72. The clinical evidence showed

that the condition of many of the children had not sig

nificantly improved or had actually regressed due to their

inappropriate placement and the lack of adequate services,

J.A. 68, 74.

SHS is primarily an adult psychiatric hospital with

no special programs designed for juveniles. J.A. 72. The

children confined at SHS were housed in facilities where

physical contact with adult psychiatric patients was un

avoidable. Many of these adult patients were committed

by state courts for having illegal sexual conduct with

children or were deemed mentally unfit to stand trial on

charges of other criminal offenses. J.A. 63. As a result

of these living and sleeping arrangements, some of the

adult patients had inflicted bodily injuries on the chil

dren. J.A. 63-64.

On August 4, 1980, respondents filed a complaint

against petitioners and the Superintendent of the Idaho

State Department of Education ( “ Department of Edu

cation” ) seeking an injunction ordering the defendants

to provide class members with appropriate educational

and mental health services, to establish procedures for

the development of community-based residential treat

ment programs and to prevent the future admission of

children to the adult patient facilities at SHS. Respond

ents’ claims were based upon the due process and equal

protection guarantees of the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution, and var

3

ious federal and state statutory provisions protecting the

rights of the handicapped. The complaint did not re

quest damages for injuries suffered by members of the

class, but it sought injunctive relief to ensure that the

children would be provided the minimally adequate serv

ices required by law. J.A. 31.

The class of indigent children was represented by

Idaho Legal Aid Services, Inc. ( “ Idaho Legal Aid” ), a

private, non-profit organization that provides free legal

services to qualified low-income persons. As an entity

receiving grants under the Legal Services Corporation

Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2996-29961 (1982), Idaho Legal Aid is

prohibited from representing individuals who are capable

of paying their own legal fees. See id. § 2996f(b) (1) ; 45

C.F.R. § 1609 (1984). Thus, no fee agreement requiring

respondents to pay for legal services could have been ob

tained. However, the complaint sought costs and attor

ney’s fees pursuant to the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees

Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1982).2 See

J.A. 31.

Settlement discussions began within three months after

the action commenced, before substantial work had been

done on the case. During the initial stages of negotia

tions respondents attempted to settle both the education

and mental health services claims. By March 26, 1981,

respondents had reached a basic agreement with the De

partment of Education on the need for appropriate educa

tional services for the children, see Appendix to Brief of

Petitioners ( “ Pet, App.” ) 2-3, and on October 19, 1981

the parties entered into a stipulation resolving all of the

2 42 U.S.C. § 1988 provides in pertinent part:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a provision of sections

1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, and 1986 of this title, title IX of

Public Law 92-318, or title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party,

other than the United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as

part of the costs.

4

education-related claims. As part of its settlement pro

posal, the Department of Education required that re

spondents waive their statutory right to attorney’s fees,

and respondents agreed. J.A. 54.

Settlement discussions with petitioners on the mental

health services claims did not proceed as smoothly. On

March 26, 1981, respondents’ counsel informed peti

tioners of significant problems with their proposed stip

ulation, which failed to include adequate commitments

on issues of critical importance, including the establish

ment of individualized treatment plans prepared by a

qualified mental health professional, the determination

of an appropriate minimum age for admission of pa

tients to SHS, and the segregation of patients under age

twenty-one from the adult patients at SHS. Petitioners

also insisted on a waiver of fees by respondents. Pet.

App. 2-5. After eight months of further negotiations,

counsel for both sides reached complete agreement on

the medical services issues, as well as the fee waiver,

but petitioners nonetheless rejected the settlement on De

cember 18, 1981.

Respondents therefore had no alternative but to press

for a judicial resolution of their claims. From Decem

ber 1981 to March 1983 the litigation intensified, as re

spondents’ counsel engaged in extensive discovery, pre

trial proceedings, motions for summary judgment, and

preparation for trial.3 On July 26, 1982, the district

court granted petitioners’ motion for summary judg

ment as to some of respondents’ statutory claims, but

3 Respondents served several sets of interrogatories, requests for

production of documents, requests for admissions and written in

terrogatories, and took extensive depositions. Respondents also

continued to press their motions for class certification and for

preliminary injunctive relief. In addition, they responded to peti

tioners’ discovery requests and motion for summary judgment, and

undertook extensive trial preparations, including subpoenaing wit

nesses, preparing experts, outlining testimony, preparing exhibits

and drafting a pretrial statement.

5

denied summary judgment on all other grounds, includ

ing respondents’ federal constitutional claims. Contrary

to petitioners’ assertions, see Brief for Petitioners ( “ Pet.

Br.” ) 9, 44, the court’s order of partial summary judg

ment did not preclude recovery of any of the relief

sought, and ultimately obtained, by respondents. See J.A.

31, 56. Two months after the court ruled on summary

judgment, it certified the plaintiff class. J.A. 58.

In March 1983, one week before the trial was sched

uled to begin, petitioners presented a new settlement

proposal. This stipulation offered virtually all of the

injunctive relief respondents had sought in their com

plaint, Jeff D. v. Evans, 743 F.2d 648, 649-50 (9th Cir.

1984), but demanded a complete waiver of all claims

for costs and attorney’s fees. J.A. 104. Respondents’

counsel informed petitioners that his clients would ac

cept the stipulation on the merits with minor additions,

but strenuously objected to the paragraph demanding a

waiver of attorney’s fees because it unethically placed

him in conflict with the interests of his clients. 743 F.2d

at 650; J.A. 89.

Taking advantage of the ethical dilemma in which

they had placed respondents’ counsel by offering sub

stantial relief on the merits while insisting that coun

sel receive no compensation, even after two and a half

years of litigation, petitioners refused to withdraw the

demand for a fee waiver. They did agree, however, to

respondents’ suggestion that the validity of the waiver

be determined by the district court. The parties there

fore modified the stipulation by adding the phrase “ if

so approved by the Court” after the fee waiver.4

4 As modified, the relevant paragraph of the stipulation read:

25. Plaintiffs and defendants shall each bear their own costs

and attorney’s fees thus far incurred, if so approved by the

Court.

J.A. 104 (emphasis added).

6

The parties submitted the settlement agreement, in

cluding the fee waiver, to the district court for approval

pursuant to Rule 23(e). At a hearing on March 22,

1983, the district court vacated the trial date and took

the matter under submission. Two weeks later, re

spondents filed a Motion for Consideration of Costs and

Attorney Fees on Settlement. J.A. 87. At a second hear

ing convened on April 28, 1983, the district court ap

proved the stipulation, J.A. 94, and on May 6, 1983 the

court denied respondents’ motion for costs and attorney’s

fees, J.A. 106.

In considering whether to allow costs and attorney’s

fees, the district court did not question the strength of

respondents’ case, nor did it suggest that respondents

had not prevailed in the action by virtue of the substan

tial equitable relief they received in the settlement. 743

F.2d at 650. In fact, as the court of appeals observed,

petitioners themselves did “ not maintain that there [was]

any basis, apart from the stipulation, for the denial of

attorney’s fees. . . . [Their] only contention [was] that

the [respondents] should be bound by the stipulation

waiving fees.” Id.

The district court denied costs and fees solely on the

basis of the stipulated waiver, but in approving the

waiver it focused on the wrong legal and ethical issues

presented by petitioners’ demand. In its view, the validity

of the waiver turned entirely on whether the decision of

respondents’ counsel would harm his clients:

[T]he ethical consideration is “ Is the attorney in the

process of bargaining out to depreciate his client’s

claim or to proceed in a manner that will he unfair

to his client?” And I think the ethical considera

tions run only to [that] issue . . . .

J.A. 93. The court thus failed to recognize that by offer

ing nearly all of the injunctive relief sought in the com

plaint but insisting on a fee waiver, petitioners had placed

respondents’ counsel in a conflict of interest with his

7

clients that could be resolved only by acceding to the

waiver. It also failed to recognize that this tactic would

enable petitioners to circumvent their statutory liability

for fees and frustrate the policies Congress sought to

implement by making fees available to prevailing parties

under Section 1988.

Respondents appealed from the May 6 order denying

costs and fees, and the Ninth Circuit reversed.5 Although

the court of appeals discussed in dictum a decision of the

Third Circuit disapproving all simultaneous negotiations

of merits and attorney’s fees, see Prandini v. National

Tea Co., 557 F.2d 1015 (3d Cir. 1977), it reaffirmed the

view held by the Ninth Circuit that the results of such

fee negotiations are not “per se unacceptable.” 743 F.2d

at 652. However, after considering the undisputed facts

of this case, the requirements of Rule 23 and Section

1988, the public policies served by attorney’s fee awards

in civil rights cases, and the ethical conflict created by

petitioners’ demand between the class lawyer’s interest

in compensation and the class members’ interest in re

lief, the court concluded that the “ stipulated waiver of

all attorneys’ fees obtained solely as a condition for ob

taining relief for the class should not be accepted by the

court,” id. (emphasis added), and remanded the case

for a determination of reasonable attorney’s fees.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case presents a narrow question for decision, but

one that is crucial to the enforcement of the civil rights

laws: whether a court in a civil rights action, in which

only injunctive relief is sought, may enforce a complete

waiver of plaintiffs’ right to costs and attorney’s fees un

der the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,

42 U.S.C. § 1988, where the defendant on the eve of trial

5 While the appeal was pending, the Ninth Circuit also ordered

petitioners to abide by the terms of the stipulation and to imple

ment the relief provided therein while appellate review was being

completed. J.A. 117, 119.

has conditioned a settlement offer providing substantial

relief on the merits on that waiver. Rather than address

ing this fundamental issue, petitioners argue that the

court of appeals should not have imposed a per se rule

against “ simultaneous negotiation of both merits and

attorney’s fees in class action settlements.” Pet. Br. 7.

Much of the briefing by petitioners and their amici re

volves around this misconception of the case. The court

of appeals, however, did not rely on a per se rule against

simultaneous negotiations to support its decision. Rather,

it found the fee waiver in this case contrary to the im

portant public policies behind Section 1988, and held only

that a “ stipulated waiver of all attorney’s fees obtained

solely as a condition for obtaining relief for the class

should not be accepted by the court.” Jeff D. v. Evans,

743 F.2d at 652.

The facts of this case show that petitioners secured a

fee waiver by exploiting a conflict of interest between re

spondents and their counsel. Respondents are a class of

indigent, mentally and emotionally handicapped children

who sought to obtain lawful conditions of institutionaliza

tion by petitioners. In such cases, where indigent plain

tiffs seek only injunctive relief, counsel’s only opportunity

for compensation lies in an award of statutory attorney’s

fees. Despite his interest in recovering fees, the para

mount obligation of respondents’ counsel was, as peti

tioners surely were aware, to protect the interests and

special needs of his clients. On the eve of trial, after two

and a half years of litigation and a previous refusal to

settle, petitioners offered a settlement that provided

nearly all of the merits relief sought by respondents but

demanded a complete waiver of costs and attorney’s fees

under Section 1988. Federal courts and a number of bar

ethics committees have recognized that such an offer un

fairly and improperly pits the lawyer’s interest in fees

against his client’s interest in relief on the merits. Con

fronted with that offer, respondents’ counsel could not

ethically place his own interest in compensation above his

9

clients’ need for relief. Even to delay obtaining that re

lief, which included the termination of such practices as

housing emotionally disturbed children with adult psy

chiatric patients charged with crimes, was obviously un

acceptable.

But for the stipulated fee waiver, respondents would

have been entitled to reasonable fees and costs under Sec

tion 1988. “ [A] prevailing plaintiff ‘should ordinarily

recover an attorney’s fee unless special circumstances

would render such an award unjust,’ ” Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 429 (1983) (quoting S. Rep.

No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 4 (1976)), and a plain

tiff who obtains a favorable settlement can recover fees.

See Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122 (1980). There is no

question that respondents prevailed in this case. Their

class was certified, their constitutional claims withstood

summary judgment, and, on the eve of trial, they ob

tained a settlement granting them nearly all of the relief

they sought. Only by - “ driv[ing] a wedge” between

respondents and their counsel, Pet. Br. 37, and by play

ing upon counsel’s professional concern for his clients’

interests, were petitioners able to circumvent their lia

bility for attorney’s fees under Section 1988. By coercing

a waiver of respondents’ federally created rights under

Section 1988, petitioners’ actions contravene that statute

and raise significant constitutional questions.

The impact of petitioners’ tactic, if upheld, would ex

tend far beyond the denial of fees in this case. Indeed,

its effect would be to undermine the policies Congress

sought to implement through Section 1988. Recognizing

that most “victims of civil rights violations cannot afford

legal counsel,” Congress authorized fee awards to “ at

tract competent counsel” to civil rights cases and thus

enable indigent plaintiffs to “present their cases to the

courts.” H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 1, 9

(1976). Finding that “ fee awards are essential” if the

civil rights laws are to be “ fully enforced,” S. Rep. No.

10

1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., 5 (1976), Congress enacted

Section 1988 to encourage private enforcement of those

laws. These congressional purposes plainly would be

frustrated by judicial enforcement of coerced fee waivers.

If upheld, defendants will routinely demand, and obtain,

fee waivers as a condition to settlement in civil rights

cases. Deprived of the economic incentives intended by

Congress, indigent civil rights plaintiffs seeking injunc

tive relief will be unable to attract competent counsel to

present their claims.

The district court addressed none of the problems posed

by the fee waiver in this case. It completely misappre

hended the coercive nature of petitioners’ demand, dis

regarded the impact of such a fee waiver on the purposes

of Section 1988, and rubber-stamped the stipulated waiver

without independently assessing, as it was required to do

under Section 1988, the reasonableness of awarding no

fees at all in this case. See, e.g., Jones v. Amalgamated

Warbasse Houses, Inc., 721 F.2d 881, 884 (2d Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 1929 (1984).

The court of appeals correctly reversed the district

court and held that the fee waiver should not be enforced.

The court plainly had authority to invalidate a provision

of an agreement that is contrary to public policy, see,

e.g., McBrearty v. United States Taxpayers Union, 668

F.2d 450 (8th Cir. 1982) (per curiam) ; Restatement

(Second) of Contracts § 178 (1981), and its decision was

consistent with the rulings of other courts that have set

aside fee waivers as contrary to the public policy em

bodied in Section 1988. E.g., Shadis v. Beal, 685 F.2d

824 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 970 (1982);

Gillespie v. Brewer, 602 F. Supp. 218, 226-28 (N.D.

W. Va. 1985).

Contrary to petitioners’ contention, the court of ap

peals also correctly declined to invalidate the entire set

tlement agreement. Courts have modified fee provisions

11

and invalidated fee waivers without disturbing the rest

of the settlement agreements of which they were a part.

See, e.g., Jones v. Amalgamated Warbasse-, Shadis v.

Beal. Moreover, the parties here recognized the question

able validity of the fee waiver and explicitly reserved the

issue for the court to decide. Finally, if it was improper

for petitioners to insist upon a fee waiver as a settlement

condition, it would make little sense to allow them to

avoid all of their obligations under the agreement on the

ground that they relied on the impermissible waiver.

Petitioners and their amici suggest various alternatives

to address the problems posed by coerced fee waivers, but

none would be as fair and effective as the approach taken

by the court of appeals. For example, they suggest that

the problems posed by the type of fee waiver demanded

here could be avoided by a carefully crafted retainer

agreement. But even if a retainer agreement explicitly

authorized respondents’ counsel to decline a settlement

offer that was clearly in the best interests of the handi

capped children he represented, it would hardly resolve

the dilemma he faced as a conscientious attorney, and it

would probably be invalid.

Finally, affirming the court of appeals decision would

not interfere with the legitimate interests of defendants

in settling civil rights cases. Defendants could still ob

tain information about fees from plaintiffs, and thus as

sess their total potential liability. Nor would such a rul

ing preclude negotiation and settlement of attorney’s fees.

Rather, it would merely eliminate a tactic that enables

defendants, contrary to Congress’ intent, to avoid any

liability for fees in settling meritorious civil rights suits.

I f the coerced fee waiver in this case is upheld, the harm

will be not only to respondents here, but also to future

indigent victims of civil rights violations, whose claims

will go unredressed because they will be unable to secure

counsel to represent them.

12

ARGUMENT

I. THIS CASE CONCERNS COERCIVE REQUESTS

FOR FEE WAIVERS IN CIVIL RIGHTS CASES,

NOT A PER SE RULE BARRING SIMULTANE

OUS NEGOTIATION OF THE MERITS AND AT

TORNEY’S FEES.

At the outset it is important to clarify the issues at

stake. This case presents a narrow question for decision:

Whether a court, in a civil rights action involving only

injunctive relief, may enforce a complete waiver of costs

and attorney’s fees, where the defendant after two and a

half years of litigation has conditioned a settlement offer

providing nearly all of the relief sought by the plaintiffs

on that waiver. Petitioners and their amici never come to

grips with this fundamental issue. Instead, conceding

that in some circumstances fee waivers are improper,

see, e.g., Pet. Br. 36, they contend that this Court should

not impose a complete ban on “ simultaneous negotiation

of both merits and attorney’s fees in class action settle

ments.” See, e.g., Pet. Br. 7; Brief for the United States

As Amicus Curiae Supporting Reversal ( “ U.S. Br.” ) 5.

That issue is simply not presented by the record or the

ruling below.

Petitioners contend that the court of appeals “ im-

pos[ed] . . . a per se bifurcated settlement rule” and

“ ruled that . . . all negotiated settlements, absent unu

sual circumstances, must be conducted in two separate

stages.” Pet. Br. 10. But the Ninth Circuit made no

such sweeping pronouncement. Rather, it held that the

fee waiver in this case contravened the public policy

reflected in Section 1988 and that the district court should

not have denied attorney’s fees on the basis of that

waiver. The court of appeals clearly stated its precise

holding:

[A] stipulated waiver of all attorney’s fees obtained

solely as a condition for obtaining relief for the class

13

should not be accepted by the court. Rather, the

court should make its own determination of the fees

that are reasonable, giving due consideration to the

appropriate factors.

Jeff D. v. Evans, 743 F.2d at 652.

That ruling is unassailable in the factual context of

this case. On the merits, respondents presented substan

tial constitutional claims concerning the state’s treatment

of mentally and emotionally handicapped children. These

claims withstood petitioners’ motion for summary judg

ment. The case was certified as a class action, and the

settlement offered by petitioners on the eve of trial pro

vided nearly all of the merits relief sought by the plain

tiff class. Thus, the concerns of several amici about not

being able to settle “ nuisance” suits do not pertain to

this case. See p. 37 infra.

In addition, respondents sought and received only in

junctive relief. Such cases leave plaintiff’s counsel with

no possibility of compensation other than an award of

fees under Section 1988. This case thus does not present

the validity of a “ lump sum” settlement or a “ sweet

heart” settlement that offers high fees to tempt plaintiff’s

counsel to accept a lower settlement on the merits.6 * 8 Peti

tioners’ settlement offer, accompanied by a demand for a

complete fee waiver, squarely pitted counsel’s interest

in compensation for his efforts against the interest

of the plaintiff class in an extremely beneficial settle

ment. As the court of appeals recognized, the ability of

defendants to exploit such a conflict in order to exact fee

waivers from plaintiffs’ counsel undermines the economic

incentives that Congress expressly provided in Section

6 The interests of plaintiffs and their counsel are not as divergent

where the parties negotiate a settlement providing monetary dam

ages or a common fund. The higher the settlement amount, the

higher the fees counsel might obtain from the fund. Similarly, in

a standard contingent fee contract, counsel’s fee is a percentage

of the monetary relief the plaintiff receives.

1988 to encourage private enforcement of the civil rights

laws.

Finally, this case does not involve a surprise challenge

by plaintiffs to a fee waiver they had misleadingly ac

cepted. Respondents’ counsel made it clear that he be

lieved the fee waiver was unlawful and unethical, and

the parties consequently made the waiver expressly sub

ject to court approval. See p. 5 & n.4 supra.'1

To be sure, there are other important issues concern

ing the settlement of cases in which statutory attorney’s

fees are recoverable. Commentators have offered a vari

ety of possible solutions to the full range of issues that

might arise in such cases.8 But this case presents only

the stark issue of the validity of a fee waiver, in a case

involving injunctive relief only, exacted from plaintiffs’

counsel on the eve of trial as a condition to a settlement

offer on the merits that was extremely favorable to his

clients. For the reasons set forth below, respondents

maintain that the judgment of the court of appeals in

validating that fee waiver should be affirmed.

14

(< * * * 7 Petitioners’ suggestion, see Pet. Br. 47-48, that there may be

special circumstances” for denying fees on the ground that the

challenge to the waiver by respondents’ counsel unfairly surprised

or misled them is thus unfounded.

8 See, e.g., Calhoun, Attorney-Client Conflicts of Interest and the

Concept of Non-Negotiable Fee Awards Under J>2 U.S.C. § 1988,

55 Colo. L. Rev. 341 (1984) (fee awards under Section 1988 should

be non-negotiable); Kraus, Ethical and Legal Concerns in Com

pelling the Waiver o f Attorney’s Fees by Civil Rights Litigants in

Exchange for Favorable Settlement of Cases Under the Civil Rights

Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976, 29 Vill. L. Rev. 597 (1984)

(endorsing ban on simultaneous negotiation of merits and attorney’s

fees) ; Wolfram, The Second Set of Players: Lawyers, Fee Shifting,

and the Limits of Professional Discipline, 47 Law & Contemp.

Probs. 293, 316-19 (1984) (endorsing post-settlement invalidation

of fee waivers as contrary to public policy) ; Comment, Settlement

Offers Conditioned Upon Waiver of Attorneys’ F ees: Policy, Legal,

and Ethical Considerations, 131 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793 (1983) (endors

ing discontinuance of simultaneous negotiations only upon request

of plaintiff’s counsel).

15

II. IN ENACTING SECTION 1988, CONGRESS DETER

MINED THAT AWARDS OF ATTORNEY’S FEES

WERE ESSENTIAL TO PRIVATE ENFORCEMENT

OF CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS.

The legislative history of Section 1988 makes its pur

pose plain: the statute was intended to facilitate pri

vate enforcement of civil rights laws by enabling pre

vailing plaintiffs to recover costs and attorney’s fees.

The Act was passed in response to this Court’s decision

in Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421

U.S. 240 (1975), which held that federal courts could

not award attorney’s fees to a prevailing party absent

explicit congressional authorization. Testimony before

Congress “ indicated that civil rights litigants were suf

fering very severe hardships because of the Alyeska deci

sion.” H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 2

(1976) ( “House Report” ). The House Report stated

that civil rights “plaintiffs were the hardest hit by the

decision,” and specifically noted that “private lawyers

were refusing to take certain types of civil rights cases

because the civil rights bar, already short of resources,

could not afford to do so.” Id. at 3. Section 1988 was

intended to remedy this problem.9

The legislative history emphasized Congress’ finding

that, if civil rights plaintiffs could not recover attorney’s

fees, they would go unrepresented and civil rights viola

tions would go unredressed. The House Judiciary Com

9 Emphasizing that Section 1988 was intended to achieve uni

formity in federal civil rights laws, petitioners suggest that this

goal was an implicit endorsement of fee waivers because such

waivers were permissible under existing fee provisions in other

civil rights statutes. See Pet. Br. 13-14. The cases cited by peti

tioners do not show that fee waivers were permissible. See p. 26

n.25 infra. In any event, the uniformity sought by Congress con

cerned the effect of this Court’s decision in Alyeska, which “ created

anomalous gaps in our civil rights laws whereby awards of fees

[were] . . . suddenly unavailable” in actions under those civil rights

statutes that lacked a fee provision. S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. 4 (1976).

16

mittee found that “ a vast majority of the victims of

civil rights violations cannot afford legal counsel” and

are therefore “unable to present their cases to the

courts.” House Report, at 1. See S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1976) ( “ Senate Report” ) (many civil

rights plaintiffs “ who must sue to enforce the law ha [ve]

little or no money with which to hire a lawyer” ). By

authorizing recovery of attorney’s fees, Section 1988 gave

“ such persons effective access to the judicial process

where their grievances can be resolved . . . .” House Re

port, at 1.

Congress found the need for recovery of attorney’s fees

“pressing” and “ compelling.” See House Report, at 3.

The Senate Judiciary Committee stressed that the “civil

rights laws depend heavily upon private enforcement,”

Senate Report, at 2, and that “ fee awards are essential”

if the civil rights laws “ are to be fully enforced.” Id. at

5. See id. at 2 ( “ fee awards have proved an essential

remedy if private citizens are to have a meaningful op

portunity to vindicate the important Congressional poli

cies” in the civil rights laws). Congress also viewed fee

awards as a critical deterrent to civil rights violations.

The Senate Judiciary Committee stressed that fee awards

are necessary “ if those who violate the Nation’s funda

mental laws are not to proceed with impunity . . . .”

Senate Report, at 2. See id. at 5 ( “ fee awards are an

integral part of the remedies necessary to obtain . . .

compliance” with civil rights laws).10

Congress specifically focused on civil rights cases in

which damages might be unavailable, noting that

awarding counsel fees to prevailing plaintiffs in such

litigation is particularly important and necessary if

10 Congress also recognized that the less desirable alternative to

vigorous private enforcement of the civil rights laws was increased

enforcement by the government. See id. at 4 ( “ fee shifting provi

sions have been successful in enabling vigorous enforcement of

modern civil rights legislation, while at the same time limiting the

growth of the enforcement bureaucracy” ).

17

Federal civil and constitutional rights are to be

adequately protected. To be sure, in a large number

of cases brought under the provisions covered by [the

bill], only injunctive relief is sought, and prevail

ing plaintiffs should ordinarily recover their counsel

fees.

House Report, at 9. See Newman v. Picjgie Park Enter

prises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968) (per curiam);

Cooper v. Singer, 719 F.2d 1496, 1502 (10th Cir. 1983).

This case epitomizes Congress’ concerns. A class of

emotionally and mentally handicapped children obviously

does not have the funds to hire private lawyers and fi

nance this type of litigation.11 Only with legal repre

sentation provided without fee by Idaho Legal Aid were

respondents able to prosecute successfully their injunc

tive claims and secure conditions and services required by

law. Respondents’ counsel had every reason to believe

they would be able to recover costs and fees if they pre

vailed at trial or through settlement.12 Instead, petition

ers compelled respondents’ lawyers to forego compensa

tion as part of a settlement offer providing nearly all of

the merits relief the class sought. If one of the results

11 In enacting the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act,

42 U.S.C. §;§ 1997-1997j (1982), Congress recognized that institu

tionalized persons are in dire need of legal representation to protect

their basic civil rights:

Most institutionalized persons are poor; many are indigent;

none possesses the resources necessary to finance litigation

challenging systematic, institution-wide abuse. The cost of

hiring experts to investigate, document, evaluate, and present

testimony on the adequacy of institutional conditions is beyond

the means of the most affluent institutionalized individuals.

S. Rep. No. 416, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. 20 (1979).

1:2 Congress made it clear that legal services organizations could

recover fees under Section 1988. See House Report, at 8 n.16;

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 70-71 n.9

(1980); Leeds v. Watson, 630 F.2d 674, 677 (9th Cir. 1980).

18

of successfully settling civil rights cases is a waiver of

costs and fees, the financial ability of Idaho Legal Aid,

or indeed any attorney, to represent future civil rights

claimants will be seriously undermined.

III. PETITIONERS WERE ABLE TO EXACT A FEE

WAIVER BY IMPROPERLY CREATING AND EX

PLOITING A CONFLICT OF INTEREST BETWEEN

RESPONDENTS AND THEIR COUNSEL.

The serious threat to the purposes of Section 1988 de

rives from the unique ability of defendants in petition

ers’ position to exploit a conflict o f interest between

plaintiffs and their counsel. Under the American Bar

Association’s Model Code of Professional Responsibility

(“ Model Code” ) ,13 a lawyer has a fiduciary obligation to

protect the interests of the client. The lawyer’s undivided

loyalty to his client cannot be diluted by his “ personal

interests,” and his professional judgment must be ex

ercised “ solely for the benefit of his client and free of

compromising influences and loyalties.” EC 5-1; see

Model Rule 1.7(b). Accordingly, an attorney is required

to evaluate a settlement offer purely on the basis of his

client’s interest, without considering his own interest

in obtaining a fee. See EC 7-7 ( “ it is for the client to

decide whether he will accept a settlement offer” ) ; Model

Rule 1.2(a) ( “ lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision

whether to accept an offer of settlement of a matter” ).

The attorney’s entitlement to seek fees under Section

1988 does not lessen his duty “always to act in a manner

consistent with the best interests of his client,” EC 7-9,

and to provide disinterested counsel to his client. A

favorable settlement offer coupled with a fee waiver de

13 The State of Idaho has adopted standards of professional

ethics very similar to the Model Code, which was adopted by the

American Bar Association in 1969. In August 1983 the American

Bar Association adopted the Model Rules of Professional Conduct.

The Model Rules and the Model Code equally support the reasoning

set forth herein.

19

mand thus directly pits the attorney’s economic interests

against the client’s interests.14

The “ cruel dilemma” faced by an attorney confronted

with such a settlement offer conditioned on a fee waiver,

Freeman v. B & B Associates, 595 F. Supp. 1338, 1342

(D.D.C. 1984), appeal docketed, No. 85-5239 (D.C. Cir.

Mar. 11, 1985), is particularly acute in the circum

stances of this case. On the one hand, the lawyer’s inter

est in recovering fees under the statute is at its height.

As is often true in civil rights cases, respondents’ counsel

had no expectation of being paid by the indigent children

he represented. Moreover, as in any case involving equi

table relief only, the relief obtained cannot provide any

compensation for the attorney.

On the other hand, the attorney here has special ob

ligations to protect his client’s interests. Counsel is ob

ligated under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 to represent adequately

the interests of the absent class members as well as the

named plaintiffs. Representing a class of mentally and

emotionally handicapped children “ casts additional re

sponsibilities upon [the] lawyer” to “ act with care to

safeguard and advance the interests of his client.” EC

7-12; see Model Rule 1.14. These ethical obligations pre

cluded respondents’ counsel from rejecting petitioners’

settlement offer, which provided immediate relief for

children in need. Respondents’ interest in promptly end

ing such practices as placing emotionally disturbed chil

dren with adult sex offenders properly dictated his deci

sion. Petitioners surely knew that respondents’ counsel

could not ethically turn down their settlement offer in

14 The Legal Services Corporation, Act specifically provides that

legal services attorneys “must have full freedom to protect the

best interests o f their clients in keeping with the Code of Profes

sional Eesponsibility, the Canons of Ethics, and the high standards

of the legal profession.” 42 U.S.C. §2996(6).

20

order to protect his fees, and they placed him in that

position solely to avoid their liability under Section 1988.15 16

Courts have widely recognized the ethical problems in

herent in settlement offers conditioned on fee waivers.

Justice Powell pointed out the conflict of interest inher

ent in an offer of judgment under Rule 68 that does not

include costs and attorney’s fees:

An offer to allow judgment that does not cover

accrued costs and attorney’s fees is unlikely to lead

to settlement. Many plaintiffs simply could not af

ford to accept such an offer. It may be, also, that

the plaintiff’s lawyer instituted the suit with no hope

of compensation beyond recovery of a fee from the

defendant. Such a lawyer might have a conflict of

interest that would inhibit encouraging his client to

accept an otherwise fair offer.

Delta Air Lines, Inc. v. August, 450 U.S. 346, 364

(1981) (Powell, J., concurring).1,6 Other courts have rec

ognized the same problem in demands for waivers of

fees under Section 1988.17

15 Petitioners contend that it would be “ anomal[ous]” to bar a

waiver of the right to attorney’s fees under Section 1988 since

constitutional rights of defendants in criminal cases can be waived.

See Pet. Br. 14 n.3. This argument completely ignores the coercive

nature of the fee waiver demanded here. Cases are legion in which

this Court has emphasized that a waiver of constitutional rights

must be “voluntary” as well as “knowing and intelligent,” Edwards

v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 482 (1981) (right to counsel), and not

“ coercefd]” or “ compelled.” Lefkowitz v. Turley, 414 U.S. 70, 79-83

(1973) (privilege against self-incrimination).

16 See Freeman v. B & B Assoc., 595 F. Supp. 1338, 1342 (D.D.C.

1984) (offer of judgment conditioned on fee waiver allows de

fendant “ to squeeze an attorney and his client into a situation

where an attorney can only be assured of an opportunity for a

fee by jeopardizing a settlement otherwise advantageous to his

client” ), appeal docketed, No. 85-5239 (D.C. Cir. Mar. 11, 1985).

17 See, e.g., Moore v. National Ass’n of Sec. Dealers, Inc., 762

F.2d 1093, 1100, 1103 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (petition for rehearing

held in abeyance pending outcome of this case); Lazar v. Pierce,

21

Petitioners and their amici suggest that White v. New

Hampshire Department of Employment Security, 455

U.S. 445 (1982), supports their position. In White, the

Court held that a post-judgment fee motion was not a

motion under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e) to alter or amend a

judgment on the merits. That the Court “decline[d] to

rely on” an alternative argument that negotiation of at

torney’s fees should be deferred until after judgment on

the merits hardly supports petitioners’ contention that

conditioning a settlement offer on a waiver o f fees is per

missible. Indeed, the Court acknowledged that simul

taneous negotiation of fees and merits “ may raise diffi

cult ethical issues for a plaintiff’s attorney.” 455 U.S. at

454 n.15.18

A number of bar ethics committees have also acknowl

edged the ethical problems presented by fee waiver de

mands. The Ethics Committee of the New York City

Bar Association has recognized that, because of his ethi

757 F.2d 435, 438 (1st Cir. 1985) ; Obin v. District No. 9 Int’ l

Ass’n of Machinists, 651 F.2d 574, 582-83 (8th Cir. 1981) ; Gillespie

v. Brewer, 602 F. Supp. 218, 226-28 (N.D. W. Va. 1985) ; Regalado

v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D. 447, 451 (D. 111. 1978).

The State Amici make much of the fact that Section 1988 author

izes an award of fees to a prevailing party, and not directly to

counsel, suggesting that any conflict of interest between attorney

and plaintiff over recovery of fees was not objectionable to Con

gress. See Brief of Alabama, et al., Amici Curiae In Support of

Petitioners ( “ States Br.” ) 19-22. But Congress made it clear

that fee awards were intended “ to attract competent counsel” to

civil rights cases, House Report, at 9, and courts have recognized

that “ a motion for fees and costs in such a case, although made in

the name of the plaintiff, is really one by the attorney.” Regalado

v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D. 447, 451 (D. 111. 1978); see James v. Home

Constr. Co. of Mobile, 689 F.2d 1357, 1358 (11th Cir. 1982).

18 Petitioners’ reliance on a statement in White that “a defendant

may have good reason to demand to know his total liability from

both damages and fees,” 455 U.S. at 454 n.15, is misplaced since

petitioners here did not seek any information on liability for fees

but insisted upon a complete fee waiver. See p. 37 infra.

22

cal obligations to the client, plaintiff’s counsel “ must

ignore his or his organization’s interest in a fee and

recommend waiver of the fee, if the substantive terms

of the settlement are desirable for the plaintiff.” Com

mittee on Professional and Judicial Ethics of the New

York City Bar Association, Op. No. 80-94 at 4, re

printed in 36 Record of New York City Bar Assoc. 507

(1981).

Defense counsel thus are in a uniquely favorable

position when they condition settlement on the waiver

of the statutory fee: they make a demand for a

benefit which the plaintiff’s lawyer cannot resist as

a matter of ethics and which the plaintiff will not

resist due to lack of interest.

Id. Noting that statutory fees are “ critical to the ad

ministration of justice,” see DR-102 (A ) (5), the Com

mittee concluded that “ it is unethical for defense coun

sel to exploit this situation in cases arising under sta

tutes aimed at protecting civil rights and civil liber

ties.” Id.19 20 The District of Columbia Bar adopted the

same analysis. District of Columbia Bar Legal Ethics

Committee, Op. No. 147, reprinted in 113 Daily Wash.

Law Rep. 389 (1985) ; see also Grievance Commission of

Board of Overseers of the Bar of Maine, Op. No. 17

(1981) (unethical to negotiate fees prior to settlement

of the underlying action where statutory fees are avail

able) .2,°

The district court here utterly failed to comprehend the

conflict of interest created by petitioners’ settlement offer

conditioned on a fee waiver. The court stated that “ the

19 The Committee also noted the special obligation of government

attorneys under EC 7-14 not to use their position or the power of

the government “ to bring about unjust settlements or results.”

20 State Bar of Georgia, Op. No. 39, reprinted in 10 Georgia State

Bar News 5 (1984) (see Pet. Br. 18), merely authorizes lump sum

settlement offers, without considering fee waivers in injunctive

relief cases.

23

ethical considerations run only to the issue” of whether

“ the attorney in the process of bargaining [is] out to

depreciate his client’s claim or to proceed in a manner

that will be unfair to his client.” J.A. 93. Presumably,

the district court would have recognized the conflict if

respondents’ counsel had refused the settlement offer by

placing his own interest in obtaining a fee above the

interests of his clients. The conflict created by peti

tioners did not disappear simply because counsel recog

nized his ethical duty and accepted the offer.

Petitioners ultimately do not dispute that their con

duct created a serious conflict of interest for respon

dents’ counsel. They merely contend that, “ in light of

these alleged conflict of interest problems,” “ a per se

bifurcated settlement rule is not appropriate.” Pet. Br.

11, 20; see also U.S. Br. 22 (conditional settlement offers

are “ not ipso facto indicative of bad faith or unethical

conduct” ). Whether or not a per se rule is appropriate,

on the facts of this case it was improper for petitioners

to use their conditional settlement offer to “ drived] a

wedge between [the] plaintiffs and plaintiff’s counsel,”

Pet. Br. 37, and exploit that conflict of interest to evade

their statutory liability for fees.21

21 Petitioners rely on the Final Subcommittee Report of the

Committee on Attorney’s Fees of the Judicial Conference of the

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Cir

cuit, reprinted in 13 Bar Rep. 4 (1984), but that report simply

declined to adopt a flat rule prohibiting- simultaneous settlement of

the merits and attorney’s fees. Moreover, the Report offered two

examples suggesting that the fee waiver in this case would be

considered improper. First, the Committee indicated that a lump

sum settlement offer would be proper in a Title VII case “ in which

the only issue is money, and the defendant believes that the plain

tiff’s case is very weak.’’ Id. at 6. By contrast, in a Freedom of

Information Act case, it would be improper for government counsel

to condition release of the requested documents upon a waiver of

attorney’s fees. “ That situation presents a grossly unfair choice

to the plaintiff and his/her counsel, and permitting such offers to be

made would seriously undermine the purpose of fee shifting provi-

24

IV. THE COURT OF APPEALS PROPERLY INVALI

DATED THE FEE WAIVER AS CONTRARY TO

SECTION 1988 AND THE PUBLIC POLICIES IT

EMBODIES.

A. The Fee Waiver In This Case Contravened Section

1988 And Its Underlying Purposes, And The Court

Of Appeals Correctly Invalidated It.

By offering to provide nearly all of the relief sought

by respondents, but conditioning the offer on a complete

waiver of attorney’s fees, petitioners placed respondents’

counsel in a conflict of interest that could only be re

solved by acceptance of the settlement and the fee waiver.

On the facts of record there is no doubt that, but for

that waiver, respondents would have been entitled to an

award of some fees under the statute. See pp. 34-35 in fra .

Thus, petitioners’ conditional settlement offer enabled

them to circumvent entirely their potential liability for

fees and effectively negated the operation of Section

1988 in this case.22

The effect of the tactic used by petitioners, however,

extends far beyond the confines of this case. In any

civil rights case in which indigent plaintiffs seek injunc

tive relief only, a defendant can evade liability for at

sions.” Id. In light of these examples, it seems highly unlikely

that the D.C. Circuit Committee would approve of government

counsel’s conditioning a settlement providing the equitable relief

requested by respondents here on a waiver of fees.

22 Where Congress has guaranteed citizens a federal right, states

may not interfere with the individual exercise of that right. See

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) ; see also Bounds v. Smith,

430 U.S. 817, 834 (1977) (Burger, C.J., dissenting). Plainly, the

state could not pass a statute precluding payment o f attorney’s fees

in certain types of civil rights cases to which Section 1988 applies.

Yet, petitioners and their amici suggest that they may be obliged

routinely to demand fee waivers in an effort to reduce their total

liability. See Pet. Br. 31-32; States Br. 53. Petitioners should not

be permitted to “accomplish indirectly . . . that which cannot be

done directly.” Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235, 243 (1970).

25

torney’s fees under Section 1988, even after years of liti

gation and no matter how strong the plaintiffs case, by

offering subtantial relief on the merits coupled with a

fee waiver demand. Because this tactic plays on coun

sel’s concerns for the interests of his clients, it is espe

cially effective where, as in this case, plaintiffs are insti

tutionalized children who are in serious need of the

relief they seek. Such coerced fee waivers plainly con

travene Congress’ purposes in enacting Section 1988. As

the First Circuit has aptly stated:

[F ]or a defendant to require [plaintiff’s counsel] to

forgo his fee (the instant case being a classic ex

ample, since the so-called settlement provided no

available funds, and, by hypothesis, the client was

indigent) or to attempt to negotiate an unreason

able fee, by playing upon counsel’s concern for his

client, is contrary to the very intendment of the Act.

. . . I f counsel can forsee themselves subject to

being euchred out of their fee, even though success

ful, the Congressional purpose will, pro tanto, be

frustrated.

Lazar v. Pierce, 757 F.2d 435, 438 (1st Cir. 1985).23

Demands for fee waivers in civil rights cases are al

ready commonplace.34 Petitioners and their amici go so

far as to suggest that defense counsel may be ethically

obliged to demand such a waiver. See Pet, Br. 32; States

Br. 51-53. If this Court endorses the practice, fee waivers

will always be demanded by defendants as a settlement

condition in civil rights cases. “ No matter how sophisti- * 24

2,3 The court in Lazar declined to allow plaintiff’s counsel to

recover fees, not because it approved of the fee waiver, but because

plaintiff’s counsel, unlike respondents’ counsel here, entered the

consent decree without informing the opposing parties of his

intention to challenge the fee waiver provision. 757 F.2d at 437,

439. See p. 29 n.29 infra.

24 The national staff counsel for the ACLU has estimated that

requests for fee waivers are made in more than half of all civil

rights cases litigated. Fee Waiver Requests Unethical: Bar Opinion,

68 A.B.A.J. 23 (1982).

26

cated the analysis of attorney responses becomes, the

conclusion remains that the more we decrease the rea

sonable expectation of Fees Act awards, the less likely

it is that Fees Act cases will be initiated.” Kraus, supra,

29 Vill. L. Rev. at 637. Congress’ goal of encouraging

private enforcement of the civil rights laws by provid

ing for recovery of fees and costs under Section 1988

clearly would be undermined by sanctioning the fee

waiver at issue here.2:i

In these circumstances, there can be no doubt that the

court of appeals was correct in concluding that the

“ waiver of all attorney’s fees obtained solely as a con

dition for obtaining relief for the class should not be

accepted . . . .” Jeff D. v. Evans, 743 F.2d at 652. Nor

is there any question that the court had authority to set

aside the coerced fee waiver as contrary to the public

policy embodied in Section 1988. It is well-established

that federal courts may void contractual provisions that

contravene public policy. E.g., McBrearty v. United

States Taxpayers Union, 668 F.2d 450 (8th Cir. 1982)

(per curiam ); see generally 6A A. Corbin, Contracts *

2j Searching for some indication that such fee waivers are per

missible, petitioners argue that when Congress passed Section

1988, it “must be presumed to have known” about two district

court cases supposedly “ interpreting] Titles II and VII to allow

plaintiffs to waive attorney’s fees,” Pet. Br. 13, and that Congress

implicitly endorsed those decisions by its silence on this issue.

Apart from the strained logic of this proposition, the decisions cited

by petitioners did not authorize a fee waiver. In one case, a settle

ment agreement specifically reserved the question of attorney’s fees

for resolution by the court. Unable to determine from the settle

ment agreement whether plaintiffs were in fact “prevailing parties,”

the court asked the parties to address this issue. See Clanton v.

Allied, Chem. Corp., 409 F. Supp. 282, 284-85 (E.D. Va. 1976).

In the other case, the court affirmed one award of attorney’s fees

under a settlement agreement and declined to award fees to another

attorney because it determined that he was not entitled to them

under the statute. Leisner v. New York Tel. Co., 398 F. Supp 1140

(S.D.N.Y. 1974).

27

§ 1375 (1962 & Supp. 1984). The Restatement (Sec

ond) of Contracts § 178 (1981) specifically provides that:

(1) A promise or other term of an agreement is

unenforceable on grounds of public policy if legisla

tion provides that it is unenforceable or the interest

in its enforcement is clearly outweighed in the cir

cumstances by a public policy against the enforce

ment of such terms.

In determining whether a provision of an agreement

contravenes public policy, Section 178 looks to “ the

strength of that policy as manifested by legislation or

judicial decisions” and “ the likelihood that refusal to

enforce the term will further that policy.” Id. § 178(3)

(a ), (b ).2*

Relying on the Restatement, the Third Circuit in

Shadis v. Beal, 685 F.2d 824 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied,,

459 U.S. 970 (1982), invalidated as contrary to public

policy a contract provision in which a legal services

organization waived any right to request or receive legal

fees in actions against the Commonwealth of Pennsyl

vania. The court stated that “ Congress expressed un

ambiguously the significance it attached to the attor

neys’ fees provisions, and we conclude that the public

policy embodied in § 1988 is a vital one.” Id. at 831.26 27

The court held the offending provision void, finding that

“ [ i]f the Commonwealth could insert and enforce the

no fees restraints in its contracts, the policy of economic

26 Section 178 also requires consideration of “ the seriousness of

any misconduct involved and the extent to which it was deliberate”

and “the directness of the connection between that misconduct and

the term.” Id. § 178(3) (c ), (d).

27 The Restatement does not require an express prohibition of

the contract term; rather, “ it is sufficient if the legislature makes

an adequate declaration of public policy which is inconsistent with

the contract’s terms.” Shadis, 685 F.2d at 833-34 (citing Restate

ment (Second) of Contracts §179, Comment (b) ( “ [a] court

. . . will look to the purpose and history o f the statute” ) ) .

inducement sought by Congress would be severely im

paired.” Id.

Courts in a variety of circumstances have refused to

give effect to a waiver of a plaintiff’s right to recover

fees. They have specifically held fee waivers demanded

as a settlement condition unenforceable as contrary to

the principles of Section 1988, just as the Ninth Circuit

held in this case. Gillespie v. Brewer, 602 F. Supp. 218,

226-28 (N.D. W. Va. 1985) ; see Lisa F. v. Snider, 561

F. Supp. 724 (N.D. Ind. 1983) (court ordered parties

to conduct settlement negotiations on the merits and

fees separately where defendant had demanded fee

waiver as a settlement condition) ; cf. Mitchell v. John-

ston, 701 F.2d 337, 351 (5th Cir. 1983) (court may not

condition pro hac vice admission of plaintiff attorneys

on waiver of their right to seek fees under Section

1988). See Wolfram, supra, 47 Law & Contemp. Probs.

at 317-18 (1984).28

In other contexts, courts have refused to find that plain

tiffs’ attorneys had waived their right to seek attorney’s

fees under the statute. For example, a settlement agree

ment that is silent on attorney’s fees has not been viewed

as an implicit waiver barring recovery of fees. See,

e.g., El Club Del Barrio, Inc. v. United Community

Corps., 735 F.2d 98 (3d Cir. 1984). Similarly, the ex

istence of a contingent fee agreement between counsel

and plaintiffs has not been considered a waiver of the

right to recover fees under Section 1988 in excess of the

contingency amount. See, e.g., Cooper v. Singer, 719

28 Courts have also protected the purposes of fee-shifting provi

sions in other statutes. See, e.g., James v. Home Constr. Co. of

Mobile, 689 F.2d 1857, 1359 (11th Cir. 1982) ( “ Congress could not

have intended to allow settling defendants to demand fee waivers

under Truth in Lending Act since “ [s]uch a result would enable

[defendants] . . . to escape liability for attorney’s fees . . . [and]

would thwart both the statute’s private enforcement scheme and

its remedial objectives” ) .

29

F.2d 1496 (10th Cir. 1983); Sanchez v. Schwartz, 688

F.2d 503, 505 (7th Cir. 1982).

In short, most courts confronting fee waivers have

been true to the purposes of Section 1988. “ Recognizing

Congress’ clear signals to apply the Act ‘broadly to

achieve its remedial purpose,’ ” Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d

1268, 1275 (5th Cir. 1980) (quoting Mid-Hudson Legal

Services, Inc. v. G&U, Inc., 578 F.2d 34, 37 (2d Cir.

1978)), they have not permitted fee waivers to under

mine Congress’ intent to provide the necessary economic

incentives for lawyers to represent indigent civil rights

plaintiffs.29

Disregarding this precedent and the especially coercive

nature of the fee waiver at issue here, the district court

simply enforced the waiver without even considering

whether it would contravene the purposes of Section

1988.30 The district court also erred by failing to make

29 Petitioners’ reliance on Moore v. National Ass’n of Sec. Dealers,

Inc., 762 F.2d 1093 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (petition for rehearing

held in abeyance pending outcome of this case), is misplaced.

The court in Moore, which specifically found this case distinguish

able, 762 F.2d at 1102, held only that “plaintiffs may, volun

tarily and on their own initiative, offer a waiver or concession of

possible claims for fees and costs in an effort to encourage settle

ment.” Id. at 1105. The court stressed this limitation on its

ruling, see id. at 1105 n.17, 1110, as did Judge Wald’s concur

ring opinion. Id. at 1112-13. It is clear in this case that re

spondents’ counsel did not voluntarily and on his own initiative

offer a fee waiver. The court in Moore also noted that the plain

tiff “ understood she had a weak case on the merits.” Id. at 1107.

Moreover, as in Lazar v. Pierce, 757 F.2d 435, 439 (1st Cir. 1985),

a critical aspect of the decision in Moore was the failure of

plaintiff’s counsel to inform the defendants or the court of his

objections to the fee waiver. See 762 F.2d at 1111 (Wald, J., con

curring) (stressing that plaintiff’s counsel “ unequivocally” in

formed the district court “ that the waiver was fully voluntary” ) .

30 Petitioners’ contention that the district court did not deny

fees solely on the basis of the waiver provision in the settlement