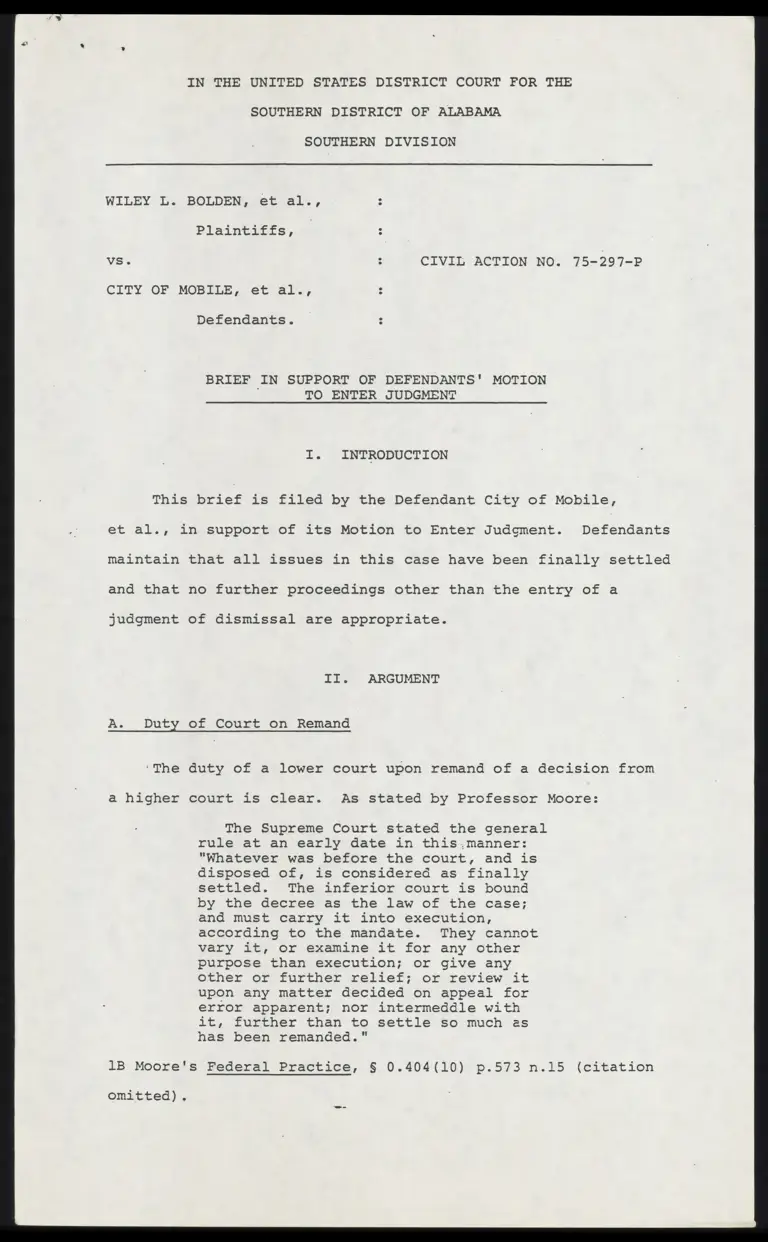

Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Enter Judgment

Public Court Documents

October 10, 1980

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Enter Judgment, 1980. 251116eb-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3082a4bb-0c36-4a84-a9ae-04b5bda84512/brief-in-support-of-defendants-motion-to-enter-judgment. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

VS. CIV1iL ACTION NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

Defendants.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS' MOTION

: TO ENTER JUDGMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

This brief is filed by the Defendant City of Mobile,

et al., in support of its Motion to Enter Judcment. Defendants

maintain that all issues in this case have been finally settled

and that no further proceedings other than the entry of a

judgment of dismissal are appropriate.

II. ARGUMENT

A. Duty of Court on Remand

‘The duty of a lower court upon remand of a decision from

a higher court is clear. As stated by Professor Moore:

The Supreme Court stated the general

rule at an early date in this.manner:

"Whatever was before the court, and is

disposed of, is considered as finally

settled. The inferior court is bound

by the decree as the law of the case;

and must carry it into execution,

according to the mandate. They cannot

vary it, or examine it for any other

purpose than execution; or give any

other or further relief; or review it

upon any matter decided on appeal for

error apparent; nor intermeddle with

it, further than to settle so much as

has been remanded."

1B Moore's Federal Practice, § 0.404 (10) p.573 n.l5 (citation

omitted).

This rule has been recognized many times by all of the

circuits. For example, a good discussion of the execution

of mandates appears in the case of Paull v. Archer-Daniels-

Midland Co., 313 F.2d 612 (8th Cir. 1963).

When a case has been decided by

this court on appeal and remanded

to the District Court, every question

which was before this court and dis-

posed of by its decree is finally

settled and determined. The District

Court is bound by the decree and must

carry it into execution according to

the mandate. It cannot alter it,

examine it except for purposes of

execution, or give any further or

other relief or review it for apparent

error with respect to any question

decided on appeal, and can only enter

a judgment or decree in strict compli-

ance with the opinion and mandate.

A mandate is completely controlling

as to all matters within its compass

but on remand the trial court is free

to pass upon any issue which was not

expressly or impliedly disposed of on

appeal. Since, however, a final judg-

ment upon the merits concludes the

parties as to all issues which were

or could have been decided, it is

obvious that such a judgment of this

court on appeal puts all such issues

out of reach of the trial court on the

remand of the case. That court is

without power to do anything which is

contrary to either the letter or spirit

of the mandate construed in the light

of the opinion of this court deciding

the case. If a judgment or decree of

this court which disposes of a case

upon the merits has become final, no

purpose can be served by considering

whether it is right or wrong. A judg-

ment which is wrong, but unreversed,

is as effective as a judgment which

is right.

Id. at 617-18 (emphasis added). Accord, In Re Sanford Ford &

Tool CO.» 160 U.S. 247, 255 (1895): Pirth v. United States,

554 F.24 950 (9th Cir. 1977).

B. Argument of Plaintiffs

Contrary to these accepted principles, Plaintiffs solicit

this court to ignore both the letter and spirit of the Surpreme

Court's mandate; their argument is accurately categorized as

Jah TE

an extraordinary effort to circumvent the Supreme Court's

decision in the case. They argue that this court is allowed

to -- is required to -- re-review the identical evidence in

this case which was before the Supreme Court and reaffirm the

same judgment that a majority of the Supreme Court reversed,

or, alternatively, grant a new trial to Plaintiffs to attempt

again to prove what they failed to prove the first time.

Defendants firmly disagree. As noted in Paull and the

other authorities referred to above, "a final judgment upon

the merits concludes the parties as to all issues which were

or could have been decided." 313 F.2d at 617 (emphasis added).

Therefore, to determine what issues, if any, were left open

by the Supreme Court it is necessary to review the issues

before the Supreme Court, the arguments made to it, and the

holdings it made.

C. Issues Before Supreme Court

As stated in Defendants' Jurisdictional Statement to

the Supreme Court at page 4, one of the issues was:

Whether the holdings of the Courts

below conflict with the constitutional

principles established by this Court

in Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124,

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, Wash-

ington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, and

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro-

politan Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 2527

Similarly on page 3 in Defendants' brief, one of the issues

was stated as:

Whether the holdings of the Courts

below conflict with the constitutional

principles set forth by this Court in

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (no constitu-

tional right to proportional representa-

tion by race), Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229, and Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (mere passive knowledge of

discriminatory effect of status guo

insufficient proof of discriminatory

intent).

Plaintiffs' brief at pages 1 and 2, stated the issues as

follows:

1. Should this Court overturn the

concurrent findings of fact of the two

courts below that Mobils's at-large

election system is maintained and operated

for the purpose of discriminating against

black voters?

, 2. Did the district court clearly

err in finding that Mobile's at-large,

elections "operate to minimize or cancel

out the voting strength" of blacks in

violation of White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 £1973), and Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124 (1971)? :

3. Does Mobile's at-large election

system violate the Fifteenth Amendment

or section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights

Act? ;

Similarly, on page of 1 their Motion to Affirm, Plaintiffs

identified the following as issues for resolution:

l. Were the concurrent factual findings

of the courts below, that Mobile's at-large

election plan is maintained for the purpose

of discriminating against black voters,

clearly erroneous?

2. Should the decision of the Court

of Appeals be affirmed on the alternative

ground -- considered but not relied on by

a majority of the Fifth Circuit panel --

that Mobile's at-large election plan had

the effect of disenfranchising black voters

in violation of White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973)?

Finally, the Supreme Court itself, in the plurality opinion,

stated that the "question in this case is whether this at-

large system of municipal elections violates the rights of

Mobile's Negro voters in contravention of federal statutory

or constitutional law." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4437 (emphasis added) .

D. Holding of Supreme Court

The holdings of the Supreme Court can be succintly

summarized as follows. The four justice plurality first

held: (1) section 2 of the Voting Rights Act has the same

effect as the fifteenth amendment; 1/ (2) "racially discrimina-

tory motivation is a necessary ingredient of a Fifteenth Amend-

1/ 48 U.8.1.W. at 4437,

ment violation;" 2/ (3) and the Plaintiffs failed to prove

3/

such discriminatory motivation. —

Turning to the fourteenth amendment claim the plurality

held that proof of all fourteenth amendment equal protection

claims, including vote dilution claims based on at-large

4/

elections, require proof of "purposeful discrimination," =

proof of "disproportionate effects alone" 5/ not being enough.

48 U.S.L.W. at 4439. Specifically, at-large elections violate

the fourteenth amendment only if "their purpose [is] invidiously

to minimize or cancel out the voting potential of racial or

6/

ethnic minorities.” —~

To prove such a purpose it is not enough

to show that the group allegedly discrimi-

nated against has not elected representa-

tives in proportion to its numbers. A

plaintiff must prove that the disputed

plan was "conceived or operated as [a]

purposeful device[] to further racial

discrimination.

48 U.S.L.W. at 4439 (citations omitted).

The last quoted sentence shows that an electoral plan

can be challenged either because HE was originally intended

("conceived") to discriminate or because, even though originally

created without discriminatory purpose, it has come to Bs Hain-

Xx

tained ("operated") for a discriminatory purpose. In either

case, the plurality made perfectly clear that proof of dis-

criminatory motivation was essential and could not be established

by proof of discriminatory effect alone.

Next, and most significantly, the plurality opinion

after announcing the correct legal principles, held that

2/ 48 U.S.L.W. at 4438.

3/ "1Tlhe District Court and Court of Appeals were in error

in believing that [Plaintiffs proved] the appellants invaded

the protection of that Amendment in the present case." 48

v.s.L.W. at 4438-39,

4/ 48 U.S.L.W. at 4439.

5/ 48 U.S.L.W. at 4439.

6/ 48 U.S.L.W. at 4439.

it is clear that the evidence in the

present case fell far short of showing

that the appellants 'conceived or

operated [a] purposeful device[] to

further racial discrimination.’

48 U.S.L.W. at 4440 (emphasis added). In other words, having

set forth the Plaintiffs' burden of proof on the immediately

preceding page of the opinion (48 U.S.L.W. at 4439), the

plurality then proceeded to record the failure of the Plaintiffs

to meet that burden.

Finally, the plurality held that the missing proof of

purposeful discrimination could not be supplied by the so-called

Zimmer standard or the foreseeability test. 48 U.S.L.W. at

4440-41 and 4440 n.l17, respectively. Rather, a plaintiff must

show that the challenged action was "at least in part 'because

of' not merely 'in spite of,' its adverse effects . . . .

48 U.S.L.W. at 4440 n.l7.

Each of these legal principles and fact findings was

supported by at least a majority of the justices. Justice

Marshall agreed with the plurality that the standards under

§ 2 of the Voting Rights Act and under the fifteenth amendment

were the same (48 U.S.L.W. at 4449 n.2), although fe disagreed

with what that standard was. Justice Stevens, although on’

\ ~ -

somewhat different legal reasoning, 1/ agreed that Plaintiffs

had failed to prove any violations of their "constitutional

rights." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4443.

7/ Defendants suggest that there is not as much distinction

in the views of the plurality and Justice Stevens as might at

first appear. Justice Stevens states "that a proper test

should focus on the objective effects of the political deci-

sion rather than the subjective motivation of the decision

maker," (48 U.S.L.W. at 4445) and argues as an example that

a system of government having an "adverse impact on black

voters plus the absence of any legitimate justification for

the system" would be found invalid while one "supported by

valid and articulable justifications cannot be invalid simply

because some participants in the decisionmaking process were

motivated by a purpose to disadvantage a minority group."

48 U.S.L.W. at 4445-46.

Defendants suggest that the plurality would likely reach

the same conclusion in similar circumstances applying the

"subjective intent" test. In the face of proved knowledge

of significant adverse impact, the failure of a defendant

to articulate a legitimate, nondiscriminatory justification

for continued adherence to the practice would likely lead

the searcher for subjective intent to conclude that the

defendant acted "because of" and not just "in spite of" the

discriminatory consequences of the practice. Cf. 48 U.S.L.W.

[Continued on page 7]

Even one of the dissenters, Justice White, appeared

to agree that proof of discriminatory intent was required

although he believed Plaintiffs had met that burden. Justice

Blackmon, concurring, pretermitting the question of the

correct legal standard, also found the proof of purposeful

discrimination sufficient. Justices Marshall and Brennan,

dissenting, also believed that discriminatory purpose had

been shown although they argued that it was not required

under their view of the correct legal standard.

Finally, despite Plaintiffs' ungrounded assertion to

the contrary, a majority of the justices (the four man plurality

and Justice Stevens 3/7 clearly rejected Zimmer, and of the

other four justices only Justice White and Justice Brennan

concurring with him even arguably supported its approach.

Neither Justice Blackmon's concurrence nor Justice Marshall's

lengthy dissent even cited Zimmer.

[Footnote 7 continued from page 6]

at 4440. Likewise, the plurality would probably agree with

Justice Stevens that even proof of some involvement of illicit

motive in a decisionmaking process would not invalidate that

decision unless the illicit consideration rose to the level

of a "substantial" or "motivating" factor within the meaning

of Mt. Healthy County Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S.

274, 287 (1977), thus shifting to the defendant the burden of

demonstrating that the same decision would have been made even

absent consideration of the illicit consideration. This con-

clusion would certainly be consistent with the holding in

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop-

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977), where the Supreme Court in

view of the presence of legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons

for a refusal to change zoning policies found insufficient

proof of racial motivation despite clear adverse impact and

evidence of some racial motivation by some participants in the

process.

In any event it is clear, and Plaintiffs concede, that

to the extent there is a difference, the Stevens standard of

proof is more stringent for the Plaintiffs than is the standard

Of the plurality. 'Plaintiffs' Brief: to the Fifth Circuit on

Remand at 4.

8/ 48 U.S.L.W. at 4441.

9/ 48 U.8.L.W. at 4445,

8/

Therefore, based on these holdings by the Supreme Court,

there is no legitimate basis for further proceedings in this

case. The four man plurality, concluding that the correct

legal standard included the requirement of a showing of pur-

poseful discrimination, viewed Plaintiffs' evidence, and opined

that it fell "far short" of proving the requisite purposeful

discrimination. And, Justice Stevens, in a separate opinion,

announced a standard that would require a stricter standard

of proof than the plurality imposed. Having had the opportunity

to present any evidence in an unrestricted manner and having

failed to meet the plurality standard, Plaintiffs fell even

further short of meeting Justice Stevens' requirements.

Similarly, the dissenting justices offer no help to

Plaintiffs in this regard since Justices Brennan, Marshall,

and White concluded that, notwithstanding their views concern-

ing what constituted the appropriate standard, the plurality's

requisite intent had been proved; Justice Blackmon reached a

similar conclusion. In this conclusion, however, they were

simply out-voted. It is therefore clear that the United States

Supreme Court thoughtfully considered Plaintiffs' evidence,

applied the correct legal standard to such evidence, and con-

cluded that such evidence was insufficient to carry the Ei.

for Plaintiffs. In other words, Plaintiffs lost. They are

not entitled to another opportunity at this juncture.

E. The Supreme Court's Evidentiary Findings

Plaintiffs argue, based primarily on the dissenting

opinion of Justices Marshall and White, 10/ that the Supreme

Court intended that the lower courts be free on remand to hold

that Plaintiffs won after all, or should at least have a

second bite at the apple in a new trial. Either option is

manifestly inconsistent with established legal principles as

10/ Defendants find no indication in the concurrence of Justice

Blackmon that he contemplated further proceedings on remand.

well as with the majority view of the Supreme Court.

When errors of law have been made in the lower court

a two step corrective process must occur. First, the correct

legal standards must be articulated by the appellate court.

Second, the evidence in the record must be reassessed in

light of the correct legal standards and new fact findings

made. In some cases only the first step is taken by the

appellate court and the cause is remanded to a lower court

to perform the second. See Malat v. Riddell, 383 U.S. 569,

572 (1966).

Such a course, however, was not followed by a majority

of the Supreme Court in this case. To the contrary, the

majority (the four justice plurality and Justice Stevens),

after identifying the controlling legal principles, went

further, reviewed the evidence in the case, and held that

it did not prove the requisite intent. Justice Stewart for

the plurality stated unequivocally:

[I]t is clear that the evidence in the

present case fell far short of showing

that the appellants "conceived or

operated [a] purposeful device[] to

further racial discrimination.” a,

48 U.S.L.W. at 4440 (emphasis added). Similarly, Justice,

Stevens said, "I agree with Mr. Justice Stewart that no

violation of [Plaintiffs'] constitutional rights has been

demonstrated . .o.' ." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4443.

Contrary to the assertion of Plaintiffs, the finding

by the plurality was not just a holding that the lower court's

Zimmer analysis was insufficient to supply the requisite proof

of intent, although the plurality most assuredly did also

hold that. Rather, Justice Stewart's evidentiary finding for

the plurality is made before any consideration had been given

to the Zimmer analysis and unequivocally refers to "the evidence

in the present case" in its entirety. The plurality's subse-

- 10 -

quent review of the Zimmer analysis and the foreseeability

test, as well as the evidence of adverse impact and official

unresponsiveness, is not a limitation on this earlier finding,

but rather a holding that such analyses and evidence could not

supply or substitute for that missing proof of discriminatory

motive.

Thus, after declaring the correct controlling legal

principles, the majority itself took the sooond corrective

step by reviewing the evidence in the case, applying the

correct legal principles, and holding as a fact that purpose-

ful discrimination had not been proved.

It is this later holding of the Supreme Court that

Plaintiffs ask this court to ignore -- not only to ignore

but to, in effect, reverse.

F. Errors in Plaintiffs! Fifth Circuit Brief on Remand

To support this remarkable effort, Plaintiffs asserted

several arguments in their Fifth Circuit brief on remand.

They argue that the Supreme Court "insisted on" misreading

the prior panel opinion (Brief at l, 10) and was stricken ,

by an "Jlnabllity t0fsee itis] ..'.cconclusion. . . ." Brief’

at 12. They argue that the Supreme Court misunderstood the

District Court's opinion and was "unable" to understand its

reasoning. Brief at 13. They argue that the Supreme Court

misinterpreted some evidence (Brief at 12) and "ignore[d]"

other evidence (Brief at 2, 12). Obviously, these arguments

simply represent Plaintiffs' belief that the Supreme Court

erred in its decision.

These arguments are addressed to the wrong court and

come too late. They are, in fact, irrelevant. This court does

not have the power to hear such arguments or decide such

issues. This court cannot review the evidence in the record

- 11 -

and say that it proves the requisite intent when a majority

of the Supreme Court reviewed the same evidence and held that

it did not.

As stated by the Ninth Circuit in Atlas Scrapper &

Engineering Co. v. Pursch, 357 F.2@ 296 (9th Cir. 1966),

cert. genied, 385 U.S. 846:

The [lower] court is bound by the decree

of the law of the case; and must carry

it into execution, according to the mandate.

That court cannot vary it, or examine it

for any other purpose than execution; or

give any other or further relief; or review

it, even for apparent error, upon any matter

decided on appeal; or intermeddled with it . . .

Id. at 298 (emphasis added).

Or, as the court in Paull noted:

That [lower] court is without power to

do anything which is contrary to either

the letter or spirit of the mandate

construed in the light of the opinion

of this court deciding the case. If a

judgment or decree of this court which

disposes of a case upon the merits has

become final, no purpose can be served

by considering whether it is right or

wrong. A judgment which is wrong, but

unreversed, is as effective as a judg-

ment which is right.

313 F.2d at 617 (emphasis added).

Plaintiffs' additional argument that the Supreme Court

went astray by failing to consider or properly interpret

evidence outlined on pages 15-22 of their Brief, which they

say proved discriminatory intent, fares no better. All of

that evidence was in the record reviewed by the Court, a

record which was held to fall "far short" of making the neces-

sary showing. 48 U.S.L..HW. at 4440. In addition, most of their

present argument was advanced by Plaintiffs in their brief to

the Supreme Court, or at oral argument, or both. Compare

Plaintiffs' Supreme Court brief pages 18-36 with pages 14-22

of their Fifth Circuit brief, both of which, for example, contain

a quotation of the testimony of Senator Robert Eddington so

heavily relied upon by Plaintiffs. Much of this evidence was

- 12 -

expressly discussed by the plurality opinion, and implicitly

considered by Justice Stevens, and found wanting. 11/ In

light of the Supreme Court holding, this court is not free

to disagree.

- The Supreme Court, considering the evidence in support

of the maintenance of the Commission form of government in

Mobile (which requires the retention of at-large elections),

also said: "[W]lhere the character of a law is readily explain-

able on grounds apart from race, as would nearly always be true

where, as here, an entire system of local governance is brought

into question, disproportionate impact alone cannot be decisive,

and courts must look to other evidence to support a finding

of discriminatory purpose." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4440. This state-

ment is then followed in the very next paragraph by the finding

that "the evidence in the present case fell far short of [making

the necessary} showing . . . ." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4440.

It is our submission, then, that the Supreme Court

considered all of the Plaintiffs' evidence and found it

wanting absolutely. Moreover, a Plaintiff would have to

produce substantially more evidence of discriminatory intent

than was produced in this case to undo an entire form of °

government, and overcome what the Supreme Court concluded

was the facial neutrality and apparent legitimacy of the

Mobile system.

G. There Is No Basis For Further Proceedings

To summarize, a majority of the Supreme Court held both

(1) that invidious intent must be shown to prove violation

of the fourteenth amendment, fifteenth amendment, and § 2 of

11/ The fact that some of the evidence argued in Plaintiffs’

brief was not expressly discussed in the majority opinion is

irrelevant. Obviously, there is no requirement that the Supreme

Court or any other court discuss in its opinion every single

item of evidence in the record. When a court holds that the

evidence in the case fails to prove an essential requirement,

that holding covers every item in the record whether or not

expressly discussed. And if the evidence was not in the record

it is obviously improper for the Plaintiffs to argue it here.

- 13 -

the Voting Rights Act and (2) that the evidence in this case

fails to prove such intent. Given those holdings, the only

remaining question is what issues, if any, are left open to

this court on remand.

Where a plaintiff has put on his case, and where an

appellate court subsequently holds that the evidence pre-

sented fails to prove that case, the obvious next step is to

enter judgment in Defendants' favor. Plaintiffs here have

had their chance to prove their allegations, and they failed.

Defendants know of no principle of law that entitles Plaintiffs

who have failed to present sufficient evidence to support the

allegations of their complaint to thereafter be given a second

chance to prove what they failed to prove the first time.

Plaintiffs do not get new trials when the evidence they present

is held to be insufficient.

For example, the Fifth Circuit in the companion case

of Nevett v., Sides, 571 PFP.24 209 (5th Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 48 U.S.L.W. 3750 (May 20, 1980), affirmed a holding

that plaintiffs had failed to prove the required discrimina-

tory motivation. Neither the Fifth Circuit in affirming the

district court nor the Supreme Court in denying certiorari.

allowed plaintiffs in Nevett a new trial to attempt again to

prove what they failed to prove at the first trial.

The Nevett case is indistinguishable from this one, the

fact that it was the Supreme Court rather than the Fifth

Circuit which held that Plaintiffs' proof was insufficient

being legally irrelevant. iz/ If Plaintiffs are entitled to

a new trial in this case, why didn't the Supreme Court grant

a new trial to the plaintiffs in Nevett by vacating that

judgment and remanding for further proceedings in light of

Bolden v. City of Mobile? The clear message of the Supreme

12/ If anything, a district court is more constricted in

granting a new trial in a case reversed by the Supreme Court

than in one reversed by itself.

- 14 -

Court is that -- at least on the two records before it ——

at-large elections were validly adopted and validly main-

tained. The Supreme Court did not intend that the district

court in this case be affirmed (or the district court in

Nevett be reversed) on some post-hoc alternate ground.

Contrary to Plaintiffs' assertion, there was no inter-

vening change in the law involved in this case. Washington

v. Davis was decided before this case was tried. The district

court and the prior panel opinion may have misinterpreted the

law, but the majority Supreme Court opinion makes clear that

their decision is merely an application of the principles of

Washington v. Davis and Arlington Heights.

The "intervening change of law" cases relied on by

Plaintiffs in their Fifth Circuit brief are inappropriate.

For example, Williams involved a district court opinion that

addressed an alleged violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

In between the decision of the trial court and appellate

review, Washington v. Davis was decided. Accordingly, the

Fifth Circuit properly remanded the case to the trial court

for reconsideration in light of Washington v. Davis. In the

Myers case, a new Supreme Court opinion was issued subsequent .

to the district court's judgment, but before appellate review.

As in Williams, the Myers court remanded the case for reconsidera-

tion in light of the new Supreme Court decision.

Nor is this a case where the district court improperly

or unfairly limited the proof which Plaintiffs were allowed

to put on. Plaintiffs were not restricted from putting such

evidence in at trial, and Plaintiffs have argued at every

stage of this litigation that the evidence they presented

in fact proved discriminatory intent. Plaintiffs can hardly

now claim that the district court denied them an opportunity

to prove the intent which they have previously consistently

argued they did prove.

- 15 -

On page 22 of its Fifth Circuit brief Plaintiffs argued

that the district court "should be instructed on remand not

to ignore the plurality's admonition to rule on the § 2 claim."

This is a mystifying contention since the plurality held that

§ 2 was identical to Plaintiffs' fifteenth amendment claim

which failed from a lack of proof.

That the remand was "for further proceedings" is certainly

not an instruction that a new trial or equivalent proceedings

be undertaken. Entry of a judgment for the Defendants, in

conformity with the Supreme Court's decision, is a further

proceeding. See Coleman v. United States, 405 F.2d 72 (9th

Cir. 1968), cert. denied, 394 U.S. 907 (1969). The Supreme

Court knows how to leave questions open for determination on

remand if it chooses to do so. See United States v. United

Continental Tuna, 425 U.S. 164, 182 (1976).

A recent opinion rendered by the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals offers additional support for Defendants' position

regarding further proceedings. United States v. Uvalde

Consolidated Independent School District, F.2d

(Slip Opinion September 2, 1980). Although Defendants do .not

agree with all said in that opinion, it contains a detalled]

consideration of the Supreme Courk's Bolden decision, and

strongly supports the City of Mobile's position concerning

its meaning and effect with regard to what further proceedings

are appropriate in this case.

In an opinion ‘authored by Judge Rubin, the majority of

the Uvalde panel (the third member, Judge Hill, concurred in

the result) clearly reads the Bolden Supreme Court majority

as holding not only that incorrect legal principles had been

applied by the lower courts, but also that under the correct

legal principles the evidence presented by the Plaintiffs

- 16 -

failed as a matter of proof to make the necessary factual

showing. For example, Judge Rubin said:

Thus, the [Bolden] plurality's

rejection of the fifteenth amendment

and § 2 claims in Bolden may rest

entirely upon the conclusion that

no discriminatory motivation was

shown.

Slip Opinion at page 9084 (emphasis added).

In fact, the Uvalde opinion goes even further, suggesting

that the Supreme Court's ruling in Bolden is more properly

viewed as an evidentiary decision rather than as a legal one.

The Uvalde panel concluded that the Supreme Court majority

essentially agreed with the legal principles enunciated by

the Fifth Circuit in Bolden, but disagreed that plaintiffs

presented sufficient evidence to satisfy those legal standards.

Judge Rubin said:

Although only Justice White appears

to have wholly adopted this court's

reasoning in Bolden, a majority appears

to agree with the legal principles set

forth in our Bolden opinion but not

with their application to the evidence

presented.

Slip Opinion at 9085 n.8 (emphasis added). The Uvalde opinion

thereby illustrates that the Bolden majority found as a factual

“ge

matter that the evidence presented in this case did not prove

a violation of the constitutional or statutory rights iis.

the fourteenth amendment. £ifteernth amendment, or § 2 of the

Voting Rights Act) of the Plaintiffs. Plaintiffs having had

their day in court and having failed to carry their burden of

proving the essential factual elements of their claim, this

action is due to be dismissed.

Finally, contrary to Plaintiffs' assertion, footnote 21

in Justice Stewart's opinion (at 4441) is not an instruction

by the plurality to grant Plaintiffs a new trial. Rather,

it is simply an observation that although Plaintiffs in this

case failed to prove the requisite intent, some other plaintiffs

in a future case would not be precluded from making such an

- 17 -

effort. Obviously, when dealing with the issue whether a

particular election system is being maintained for a dis-

criminatory purpose, a finding of no such intent in the

past does not preclude the possibility of proving that such

an illicit intent has interceded into future legislative

actions.

Certainly, this cryptic dictum embedded in a footnote

cannot be considered the creation of a heretofore unknown

principle of law that a plaintiff failing to prove essential

elements of his claim gets a new trial when the evidence

presented is held on appeal to be insufficient.

JII. CONCLUSION

Reduced to its essence, Plaintiffs' argument is that

"we did prove intent -- the Supreme Court could not or would

not see it -- but we proved it." But that argument has been

made to and rejected by the Supreme Court. Plaintiffs have

had a full, fair chance to prove their case but according to

the Supreme Court. they have failed to do so. Therefore,

.this case is over; and the only further appropriate proceeding

is to enter judgment in favor of the Defendants. \

(A900 ted

B M ARENDALL ’ JR -/

LL leds CC ads if TT

WILLIAM C. TIDWELL, IIX

P. Os: Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

OF COUNSEL:

HAND, ARENDALL, BEDSOLE,

GREAVES & JOHNSTON

BARRY HESS

City Attorney, City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

LEGAL DEPARTMENT OF THE

CITY OF MOBILE

- 18 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have on this 10th day of October, 1980,

served a copy of the foregoing brief on counsel for all parties

to this proceeding by United States mail, properly addressed,

first class postage prepaid, to:

J. U. Blacksher, Esquire

Messrs. Blacksher, Menefee & Stein

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Edward Still, Esquire

Messrs. Reeves and Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 lst Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg, Esquire

Eric Schnapper, Esquire

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle ;

New York, New York 10019

Honorable Wade H. McCree, Jr.

Solicitor General of the

United States

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

Drews S. Days, III, Esquire

Assistant Attorney General

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

. ARENDALL, JR.

Asoc |