Motion to Intervene as Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1998

60 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Perschall v. Louisiana Hardbacks. Motion to Intervene as Appellees, 1998. 66ebb456-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/30b0a597-d7aa-4511-b68a-710c93dcbab0/motion-to-intervene-as-appellees. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

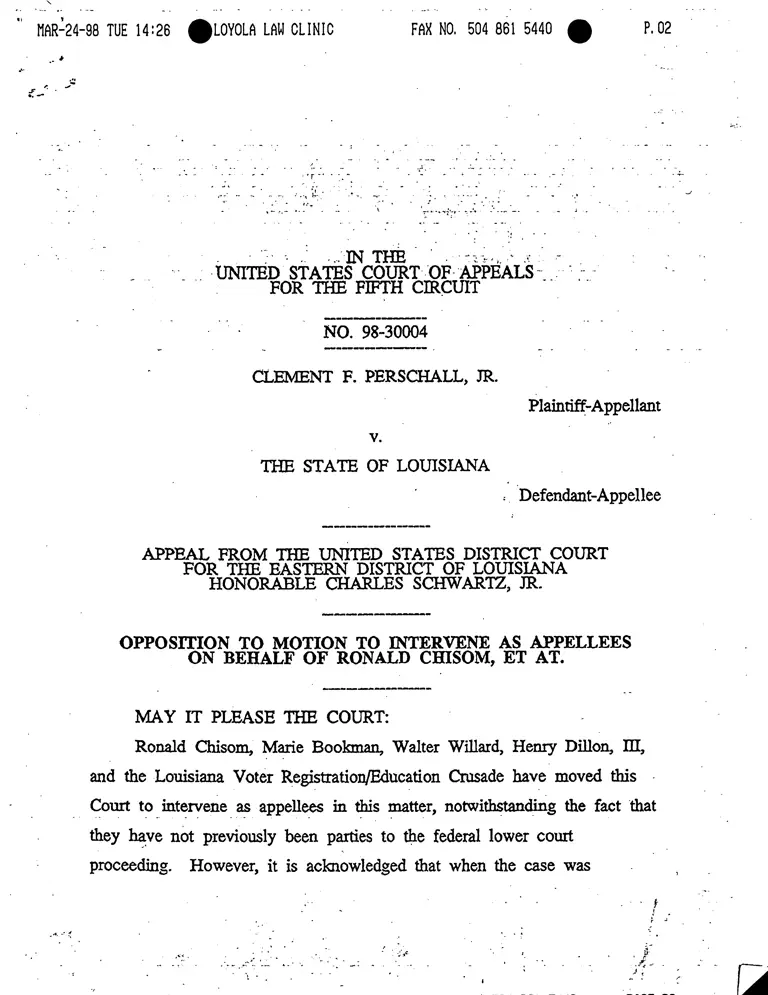

MAR-24-98 TUE 14:26 III1LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 • P. 02

:2

• • IN THE

• UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

• FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 98-30004

111••••••••=1-.M.WIM ••••••••••=1.1•1•41minirile•••••••=

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR.

Plaintiff-Appellant

V.

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

Defendant-Appellee

••••••• ••1,1=•••=11m,.1=.10•••••••••1 =1=1,•alrilmvi=

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

HONORABLE CHARLES SCHWARTZ, JR.

l•••••••••••••••• =1.11.11.11MIMMINIMMa•

OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO INTERVENE AS APPELLEES

ON BEHALF OF RONALD CHISOM, ET AT.

" dll......O.M.O.OMWIW.INMJNMJMI.OMMPAMIMWYWOMIWIMaft

MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT:

Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, Henry Dillon, III,

and the Louisiana Voter Registration/Education Crusade have moved this

Court to intervene as appellees in this matter, notwithstanding the fact that

they have not previously been parties to the federal lower court

proceeding. However, it is acknowledged that when the case was

NR-24-98 TUE 14:27 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P. 03

7

remanded to state court that under the procedural rules of the State of

Louisiana the aforesaid parties, did participate.- - But as the _record will

reflect their participation was nothing more than-- to mirror- the pleadings

filed by the State of Louisiana. Their presence in the suit added only

- --

additional bodies to reinforce the position of the - State of Louisiana

The proposed intervenors correctly note that the State of Louisiana is

presumed to provide an adequate representation on behalf of its citizenry.

Further, it is the State of Louisiana and only the State of Louisiana which

is legally bound to defend an act of the legislature.1 The attorney general

has exercised his right and obligation to defend this matter and has

retained six outside attorneys in addition to his own staff to assist in the

defense of this matter. The proceedings have been long and arduous,

attesting to the adequacy of the defense by the State of Louisiana. The

numerous motions and briefs filed on behalf of the State of Louisiana in

both the state proceedings and the federal district court attest to that fact.

The intervenors allege that because they are parties to the Chisom

Consent Decree that only they will vigorously defend this action

irrespective that the State of Louisiana is also a party to the Chisom

Consent Decree. But their zeal is not a basis for their participation.

Further, the proposed intervenors have asserted no unique interest in this

case as opposed to the State of Louisiana and the records of these

proceedings will support this conclusion. The Court need only compare

the answer filed by the intervenors to the appellant's petition for

1

La. CONST. art. 4, § 8.

MARL24-98 TUE 14:27 1111LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P. 04

^

declaratory judgment with the ans. wer _filed by the State _ of Louisiana. __

These answers are virtually idehticarto- -on-es another; including the exact _ .

wording in most of the responses. .(See the enclosed Exhibit 1.)

Not only did the proposed intervenors allege no new defenses or

raise no new issues by their answer, but - their ,brief before the -Louisiana

Supreme Court was nothing more than a reiteration - of the argument made

- _

by the State of Louisiana, ie , that the Chisom Consent Decree, _ being a,

federal court order, preempted the ability of the Louisiana courts to decide

the constitutional issue of Acts 1992, No. 512, iunder, the supremacy s clause

of the United States Constitution. Although the State of Louisiana raised

several additional issues regarding the legality of Acts 1992, No. 512, the

proposed intervenors brief was addressed solely to the effect of the

Chisom Consent Decree under the supremacy clause. Their brief was a

restatement of one issue addressed and discussed by the State of

Louisiana.

As further evidence that the proposed intervenors are merely

mirroring the State's action, one need only look to the pleadings the

intervenor attempted to file in the federal district court after the State of

Louisiana filed a motion to dismiss appellant's action on the basis of

mootness. (The dismissal order by the lower court is based upon

mootness and it is now the issue on appeal before this Court.) The

proposed intervenors, although not having been permitted to intervene, filed

"Defendant-Intervenors' Reply to the State's Motion and Incorporated

Memorandum to Dismiss." The second sentence of the memorandum

states:

- 3

M^M I A I AAle,e1 =MA MG4 =AAM

MAIRI-24-98 TUE 14:28 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FA).( NO. 504 861 5440 1110 P. 05

"The defendant - intervenors agree with the views• expressed

in the State's Motion and Incorporated Memorandum to

Dismiss."

The intervenors' memorandum makes no further assertion of law or legal

issues to support the State's motion to dismiss. One can only conclude

that the State of Louisiana has asserted the same issues which the

intervenors would have asserted had they been a party.

In these entire proceedings the proposed intervenors show no lack of

adequate representation by the State, nor do they assert any interast that

belongs uniquely to them as opposed to the State Louisiana, which would

eve to them a direct right to maintain a defense over and above that

which could be asserted by the State of Louisiana.' The intervenors in

this matter address this Court in the same fashion as the intervenors did

in the raatter of Keith v. Daley? In that particular case, the

constitutionality of an Illinois statute had been questioned and it was being

defended by the attorney general of the State of Illinois. The Illinois Pro-

Life Coalition, Inc. (IPC), sought to intervene in the action because of its

position that the Illinois act should be maintained in support of the Illinois

anti-abortion statute. The court in denying the motion to intervene, stated:

"Moreover the defendants in the instant case are duly

representing I-EB 1399. The IPC suggests that it is the

prmcipal proponent of I-EB 1399, and that the defendants, while

'honorably committed to their duty of defending duly enacted

state lec.rislation_. - cannot match the conviction and thorough

knowledge of the subject area held by the proposed intervexxors

' . . -A subjective comparison, however, of the convictions

of defendants and intervenors is not the test for determining

the adequacy of representation. Adequacy can be presumed

2 Keith v. Daley, 764 F.2d 1265 (CA 7th Cir., 1985) at p. 1268.

3 id.

4

I.1A1-24-98 TUE 14:29 OLOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P.06

_ when the pally_ on whose _behalf the applicant seeks - .

intervention is a governmental body or officer charged by law_

with representing the interest of , the proposed interveifor.

Moreover, we need not rely only on this presumption: •. The

record in this case indicates that the named defendants charged

by law with defending the laws of Illinois . . . have

adequately_ defended this suit." At p. 1270.

The. piopb-sectintei-veno-rs herein would allege that their interest

regarding the effects of Acts 1992, No. 512, are greater than that of the

State of Louisiana because this Act was the basis for the Chisoni Consent

Decree in which they were the party plaintiffs. Yet as in Keith v. Paley,

the record reflects that the issues relative to the constitutionality of Acts

1992, No. 512, as asserted by the intervenors is no different than those

asserted by the State of Louisiana. The State of Louisiana, by law, can

and is defending the case vigorously, therefore, under the factors

considered for intervention pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 24 (a)(2) and the

presumed ability of the State to represent each citizen's interest on a state

constitutional matter, this intervention should be denied.

Respectfully Submitted:

5

Clement F. Perschall, Jr.

In Proper Person

110 Veterans Boulevard

Suite 340

Metairie, LA 70005

Telephone: (504) 836-5975

• •

PAGE. 06 MAR 24 '98 14:51

MAR-24-98 TUE 14:29 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P. 07

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE -

-ertifythátI hàie served a true and ; collect èop f the -aforegozie

on all cii*m§el of record on this 23d day of March, 1998, as follows:

f • I.:

•— Peter 3. Butler, Esq.

909 Poydras Street

-:-Suite 2400

New Orleans, LA 70112

6

William P. Quigle, Esq.

Loyola University of

New 'Orleans

School of Law

7214 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70118

MAR 24 '98 14:52 '504 861 5440 PAGE.0?

1410-24-98 TUE 14:30 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 S P. 08

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA _

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR.

NTER -us _

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

* * * * *

,

* * * * * * *

ANSWER

CIVIL ACTION NO.: 95-259--

SCTION "I'3"

MAGISTRATE (1)

NOW INTO COURT, through its undersigned counsel, comes defendant the State -

of Louisiana who, in response to the Petition for Declaratory. Judgment on the

Constitutionality of Acts 1992, No. 512 filed by plaintiff in this matter (the 'Petition"),

removed to this Court on February 27, 1995, avers as follows:

FIRST SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The Petition fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

IL

SECOND SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in the Petition are barred by the doctrine of

accord and satisfaction.

THIRD SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The plaintiff is estopped from raising the issues and praying for the relief set forth

in his Petition.

Ey A .1, j- I liAsatY

' MAR:24-98 TUE 14:30 OLOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P. 09

IV.

FOURTH SPECIAL AND AffiRMATIVE DEFENSE -

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the

doctrine of laches, liberative preiciiption, and/or any and all other applicable statutes of

limitations. • • -

V..

FIFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the

doctrine of res judicata.

VI.

SIXTIi SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Plaintiff has waived the issues raised and the relief prayed for in his Petition.

VII.

SEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act No. 512 of the 1992 regular Louisiana legislative

session, codified in La. R.S. § 13:312 and referred to throughout the Petition ("Act 512"),

comports and is consistent with, and does not violate any Article or Section of the Louisiana

Constitution of 1974, including, but not limited to, Article 3, Section 12(A), Article 3, Section

13, and Article 5, Section 3 of said Louisiana Constitution of 1974.

VIII.

EIGHTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any Article or Section of the United States Constitution.

MAR-24-98 TUE 14:31 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO. 504 861 5440 P. 10

(..

- NINTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant Spe-eifically.iifers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with,and does

not violate any and all applicable laws.

X •

-

- • TENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant -specifically avers .that Act 512 comports and is consistent with,-and does

not violate any Article or Part of the Rules of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

XI.

ELEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant further avers that plaintiff lacks standing to raise the issues and relief

prayed for in his Petition.

XII.

TWELFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 is not a local or special law pursuant to the

Louisiana State Constitution of 1974, or any jurisprudence interpreting it..

AND NOW, in further response to the Petition, defendant avers as follows:

XIII.

Defendant admits the allegations set forth in Articles I, IX, XII, XIV, XV, XVI and

XVII of the Petition. XIV.

For lack of sufficient information to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations set forth in Articles II, XIII and X)UX of the Petition.

-3-

MAR-24-98 TUE 14:31 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO, 504 861 5440 P.11

In response to Articles III, IV, V and VI of the Petition; defendant specifically avers

- _

that Act 512 constitutes the best evidence of its contents and speaks for itself. moreover, the

statements set forth in said 4rticlei constitute conclusions of law to which no response is

required; however, in an abundance* of caution, defendant* denies the statements set forth

-

in said Articles.

XVL

The all in Articles XXXII, xxxvn, XLIV and XLVII require no response;

_

however, in an abundance of caution defendant deny the allegations in said Articles.

XVII.

Defendant denies the allegations set forth in Articles XXX, XXXI, XXXVI,

XLI, XLII, XLIII, XLVI and XLVIII.

XVIII.

In response to Article VII of the Petition, defendant admits that Act No. 512 was

sponsored by Senators Jones and Mona]; however, Act No. 512 was also sponsored by

Representatives Copeland, Landrieu, Murray and Singleton.

XIX.

In response to Article VIII of the Petition, defendant admits that d purpose of Senate

Bill No. 1255, as originally introduced by Senator Jones, was:

-"to amend and re-enact RS. 13:312(2)(B) and 312.1(B) relative

to the courts and the judiciary; to divide the districts of certain

courts of appeal in this state into geographical election sections

for the purpose of qualification and election of appeal court

judges; to provide for the number of judges to be elected from

the sections of such districts; to provide. relative to the _terms of

office of certain appeal court district court judges; to provide

for effective date of these provisions; and to provide for related

matters."

-4- -

MAR-24-98 TUE 14:32 •LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO, 504 861 5440 P.12

XX.

In response to Article X of the Petition, defendant admits that on June 2, 1992, the

Senate Committee on Judiciary A convened during which Senate Bill No.. 1255 of the 1992 _ _

Regular SessiOn viat di*cusied.*

In response to Article XI of the Petition, defendant admits that the Unapproved

Rough Verbatim Minutes of the Louisiana State Senate Committee on Judiciary A reflect

that Senator Marc Morial participated in a meeting of that Committee, a copy of which

Minutes attached to plaintiff's Petition as Exhibit C, constitute the best evidence of their

contents and speak for themselves.

XXII.

In response to Article XVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that Act 512 constitutes

and reflects the best evidence of its contents; accordingly, defendant denies the conclusions

set forth in said Article XVIII.

X.XIII.

In response to Article XIX of the Petition, defendant admits that Marc Morial was

an original plaintiff in that case styled Chisom, et al v. Edwin Edwards in his Capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana, et al, bearing Civil Action No. 86-4075 on the docket

of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana ("Chisom"); for lack

of sufficient information upon which to justify a belief as to the trUth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations in said Article that Marc Morial was a Senator of the State of

Louisiana at the time of the commencement of Chisom.

XXIV.

In response to Articles XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, and XL, defendant

avers that the record in Chisom represents the best evidence of its contents and the best

MO-24-98 TUE 14:33 1111 LOYOLA LAW CLINIC FAX NO, 504 861 5440 P. 13

evidence of the allegations set forth in said Articles; accordingly, defendant denies said

Articles as written.

In response to Article XXVI of the Petition, defendant denies the allegations as

written; in addition, defendant avers that references made in said Article to the consent

judgment rendered in Chisom a copy of which is attached as Exhibit G to plaintiff's Petition,

^

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVI.

In response to Article )VII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992, Senator

Morial introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session Senate Bill No. 39 which, inter die',

sought to increase the number of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices to nine; defendant avers

that Senate Bill No. 39, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to plaintiff's Petition,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

In response to Article XXVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992,

Representative Morrell introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session House Bill No. 55

which, inter alia, sought to provide for the appointment by the Governor of an eighth Justice

to the Louisiana Supreme Court; defendant avers that House Bill No. 55, a copy of which

is attached is Exhibit I to plaintiffs Petition constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVIII.

In response to Article =CM of the Petition, defendant avers that Article 5, Section

3 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974 reads as follows:

"The supreme court shall be composed of a chief justice and six

associate justices, four of whom must concur to render

judgment. The term of a Supreme Court judge shall be ten

years."

-6-

VI'30Ud 198 VOS

_

411p:PT 86. P? ekiW

XXIX.

In response to Article XXXIV of the Petition, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4 - _

_

and Act 512 constitute the best evidence of their contents. -

In response to Article XXXV of the Petition, defendant avers that Louisiana Supreme

Court Rule IV, Part II constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXXI.

In response to Article XXXVIII of the Petition, defendant adMits thestatenientS set

forth therein;- however, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4, codifying Act 512, is nal a

local or special law as such law is defined by the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

XXXII.

Defendant admits the statements set forth in Article XLV of the Petition; however,

defendant specifically denies that Act 512 is a local or special law, as such law is defined in

the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

WHEREFORE, defendant, the State of Louisiana, prays that the plaintiff's Petition

for Declaratory Judgment on the constitutionality of Act 1992 No. 512 be dismissed, with

prejudice, at plaintiff's costs, and that judgment be rendered herein in favor of the

defendant, the State of Louisiana, and against plaintiff for attorney's fees incurred by the

State of Louisiana and all other just and equitable relief to which the State of Louisiana is

entitled.

-7- .

T S 1 /11-1-" T Lett, tint1 TIT! 1 nrttrnn win tinntnn t%f%.S.T nnt fl( S..J wifl

ST'30dd T98 'OS 4110:PT 86, PE eldW

Respectfully submitted,

Peter J. Butler (Bar * 3731) - TA

Peter J. Butler, Jr. (Bar # 18522) —

Pan American Life Center-

601 Poydras Street - Suite 2400 -

New Orleans; Louisiana 70130-6036

Telephone- 504) 558-5100

BY.

. BUTLER; JR. •

Special Counsel for Defendant the State of Louisiana

. CERTIFICATE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the above and foregoing pleading has been

forwarded to Clement F. Perschall, Jr. by depositing a copy thereof, postage prepaid, in the

United States mail, addressed to him at One Galleria Boulevard, Galleria One, Suite 1107,

Metairie, Louisiana 70001, on this .J day of Marc 1995.

BY:

P TER J. BU R, JR.

-8-

e•T SI ALL^ TAM LAP, 80,t1 11111 tvrIrrni, Amin unnin, 1-d, shT rinT no 4,, mutt

91'30Ud 198 VØS 1111:PT 86, VP? NUW

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT -

FOR TEE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

'CLEMENT F. PERSHCHALL; JR.,

Ns.

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA, -

Defendant,

and

RONALD CRISOM, et aL,

Defendant-Intervenors.

CIVEL ACTION NO.: 95-1265

SECTION 'A'

MAGISTRATE: 2

ANSWER OF DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS

Defendant-intervenors Ronald Chisom, et al., by their undersigned counsel, answers the

Petition for Declaratory Judgment on the Constitutionality of Acts 1992, No. 512, filed by plaintiff

in this matter (the "Petition") removed to this Court on February 27, 1995, as follows:

I.

FIRST DEFENSE

The Petition fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

IL

SECOND DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the doctrine of

laches and/or any and all other applicable statutes of limitations.

ilL

THIRD DEFENSE

Plaintiff lacks standing to maintain this action or to receive the relief sought by it.

-

0, 2_, I, I p. p. L. p. gAt t

-f,

•

r.rtirne% rtnntn.,

ve") rX 414`410.)"

•

TAT nr, mutt

CV3Otid ee 198 V05 -

4110:VT 86, VZ 8UW

. rv.

FOURTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act No. 512 of the 1992 regular Louisiana legislative Session;

codified in La. R.S. § 13:312 and referred to throughout the Petition ("Act 512"), comports and is

consistent with, and does not violate any Article or Section of the Louisiana .Constimtion of 1974,

including, but not limited to, Article 3, Section 12(A), Article 3, Section 13, and Article 5, Section

3 of said Louisiana Constitution of 1974.

IV.

FIFTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does not violate

an Article or Section of the United States Constitution.

V.

SIXTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does not violate

any and all applicable laws, or any Article or Part of the Rules of the Louisiana Supreme Court, and

that Act 512 is not a local or special law pursuant to the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974, or any

jurisprudence interpreting it.

VI.

SEVENTH DEFENSE

Defend-ant-intervenors aver that Act 512 was passed to comply with the judgment of the

Eastern District of Louisiana, as embodied in the Consent Decree entered by that Court in the case

of Chisorn v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-4075, and therefore is legal, valid, and binding under

the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution. any law of the State of Louisiana

notwithstanding.

ANSWERING SPECIFICALLY THE ALLEGATIONS OF THE PETITION, defendant-

intervenors allege and say:

I T I

0

T Aft 1, ftr. /A1.1 /

2

nArTnn mun unnInn nnt no_h,_mutt

- -...• - • • • ̂ 1-•

81'30d 0. 198 VC'S 4111f:VE 86, 17F 6:11.1

VII.

Defendint-intervenors admit the allegations set forth in Articles I, a, xrv, a, XVI and

XVII of the Petition.

For lack of sufficient information to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant-

intervenors denies the allegations set forth in Articles II, XE, and XXIX of the Petition.

In response to Articles IV, V and VI of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Act

• 512 copstimtel the best evidence of its content and sPeaks for itself; moreover, the statement set

forth in said Articles constitution conclusions of law to which no response is required; however,

defendant-intervenors deny the statements set forth in said Articles.

IX.

The allegations in Articles XMCII, XXXVII, XLIV and XLVII require no response; however,

defendant-intervenors deny the allegations in said Articles.

X.

Defendant-intervenors deny the allegations set forth in Articles XXX, MCI, XXVI, XXXIX,

KU, XLII, XLM, XLVI and XLVIII.

XI.

In response to Article VII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that Act No. 12 was

sponsored by Senators Jones and Morial; however, Act No. 512 was also sponsored by

Representatives Copelin, Landrieu, Murray and Singleton.

XCI.

In response to Article VIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that a purpose of

Senate Bill 1255, as originally introduced by Senator Jones, was:

to amend and re-enact R.S. 13:312(2)(3) and 312.1(B) relative to the coins and the

,

3

nT.I rn Inn unn YU! ULIA mun unnmn

• ••••,

ne.hr nn?. 00_h7_11Ull

6T'30Ud otire t7es 411:PT 86, PE aJW

judiciary; to divide the districts of certain courts of appeals into geographical election

sections for the purpose of qualification and election of appeal court judges; to

provide for the number of judges to be elected from the sections of such districts; to

- provide relative to the ter ins of office of certain appeal court district court judges; to

provide for effective date of these provisions; and to provide for, related matters:

XIII.

In response to Article X of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that on June 2, 1992,

the Senate Committee on Judiciary A convened during which Senate Bill No. 1255 of the 1992

Regular Session was discussed.

7ev..

In response to Article XI of the petition, defendant-intervenors admit that the Unapproved

Rough Verbatim Minutes of the Louisiana Senate Committee on Judiciary A reflect that Senator Marc

Morial participated in a meeting in a meeting of that Committee, a copy of which Minutes attached

to plaintiffs Petition as Exhibit C, constitute the best evidence of their contents and speak for

themselves.

XV.

In response to Article XVIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512

constitutes and reflects the best evidence of its content; accordingly, defdendants deny the

conclusions set forth in said Article XVIII.

XVI.

In response to-Article XIX of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that Marc Morial was

an original plaintiff in Chisom, et al. v. Edwin Edwards. et at., E.D. La. Civil Action No. 86-4075

LCIls_omj.

In response to Articles XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, and n, defendant-intervenors

aver that the record in Chisom represents the best evidence of its contents and the best evidence of

AT.I ^2-2-^ TAM L^^ ,ptT lit I '1 Atilynn yyty-y ”nnin, rtn.uT AT (I( 1. mutt

• ....-

0?'30Ud 198 VOS 4111:ST 86, PE NUW

the allegations set forth in said Articles; accordingly, defendant-inmrvenors deny said Articles as

written.

In response to Article XXVI of the Petition, defendant-intervenors deny.the allegations as

written; in addition defendant-intervenors aver that the consent judgment rendered in Chisom, a

copy of which is attached as Exhibit G to plaintiffs' Petition and as Exhibit A to' this answer,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents. Defendant-intervenors further aver that Act 512 was

passed for the specific purpose of complying with the provisions of the Consent Decree in Chisom

and its provisions are embodied in and incorporated into the judgment of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana as a result of that Court's approval of the Consent Decree

in Chisom.

x.

In response to Article XXVII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that in 1992, Senator

Modal introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session Senate Bill No. 39 which, inter alia, sought

to increase the number of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices to nine; defendant-intervenors aver that

Sente Bill No. 39, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to plaintiff's Petition, constitutes the best

evidence of its contents.

XX.

In response to Article XXVIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that in 1992,

Representative Morrell introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session House Bill No. 55 which,

inter alia, sought to provide for the appointment by the Governor of an eighth Justice to the

Louisiana Supreme Court; defendant-intervenors aver that House Bill No. 55, a copy of whioch is

attached as Exhibit I to plaintiff's petition constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXI.

5

I

IZ*30Ud 0111098 VOS 41100 86, VZ 6dW

In response to Article XXXIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Article 5,

Section 3 - of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974 reads - as follows:

The supreme court shall be composed of a chief justice and six associate justices,

four of whom must concur to render judgment. The term of 4_Supreme Court judge

shall be ten years.

In response to Article XXXII/ of the• Petition,- defendant-intervenors aver that La. R.S.

13:312.4 and Act 512 constitute the best evidence of their contents.

XXIII.

In response to Article XXXV of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Louisiana

Supreme Court Rule IV, Part U constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXIV.

In response to Article mvra of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit the statements

set forth therein; however, defendant-intervenors aver that La. R.S. 13:312.4, codifying Act 512,

is not a local or special law as such law is defined by the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

)0CV.

Defendant-intervenors admit the statements set forth in Article XLV of the Petition; however,

defendant-intervenors deny that Act 512 is a local or special law, as such law is defined in the

Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

WHEREFORE; defendant-intervenors Ronald Chisom, et al., pray that the plaintiffs Petition

for Declaratory Judgment on the constitutionality of Act 1992, No. 512 be dismissed, with prejudice,

at plaintiffs costs, and that judgment be rendered herein in favor of the defendant-intervenors.

T., ALL-A T 1_AA lAtt 111 t I %?t?YtA U117 ”nntn, nnl nn L7 MUT!

AMR 30 1998

_

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 98-30004

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR.

Plaintiff-Appellant

V.

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

Defendant-Appellee

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

HONORABLE CHARLES SCHWARTZ, JR.

OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO INTERVENE AS APPELLEES

ON BEHALF OF RONALD CHISOM, ET AT.

MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT:

Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, Henry Dillon, III,

and the Louisiana Voter Registration/Education Crusade have moved this

Court to intervene as appellees in this matter, notwithstanding the fact that

they have not previously been parties to the federal lower court

proceeding. However, it is acknowledged that when the case was

remanded to state court that under the procedural rules of the State of

Louisiana the aforesaid parties did participate. But as the record will

reflect their participation was nothing more than to mirror the pleadings

filed by the State of Louisiana. Their presence in the suit added only

additional bodies to reinforce the position of the State of Louisiana.

The proposed intervenors correctly note that the State of Louisiana is

presumed to provide an adequate representation on behalf of its citizenry.

Further, it is the State of Louisiana and only the State of Louisiana which

is legally bound to defend an act of the legislature.1 The attorney general

has exercised his right and obligation to defend this matter and has

retained six outside attorneys in addition to his own staff to assist in the

defense of this matter. The proceedings have been long and arduous,

attesting to the adequacy of the defense by the State of Louisiana. The

numerous motions and briefs filed on behalf of the State of Louisiana in

both the state proceedings and the federal district court attest to that fact.

The intervenors allege that because they are parties to the Chisom

Consent Decree that only they will vigorously defend this action

irrespective that the State of Louisiana is also a party to the Chisom

Consent Decree. But their zeal is not a basis for their participation.

Further, the proposed intervenors have asserted no unique interest in this

case as opposed to the State of Louisiana and the records of these

proceedings will support this conclusion. The Court need only compare

the answer filed by the intervenors to the appellant's petition for

1

La. CONST. art. 4, § 8.

2

declaratory judgment with the answer filed by the State of Louisiana.

These answers are virtually identical to one another, including the exact

wording in most of the responses. (See the enclosed Exhibit 1.)

Not only did the proposed intervenors allege no new defenses or

raise no new issues by their answer, but their brief before the Louisiana

Supreme Court was nothing more than a reiteration of the argument made

by the State of Louisiana, ie., that the Chisom Consent Decree, being a

federal court order, preempted the ability of the Louisiana courts to decide

the constitutional issue of Acts 1992, No. 512, under the supremacy clause

of the United States Constitution. Although the State of Louisiana raised

several additional issues regarding the legality of Acts 1992, No. 512, the

proposed intervenors brief was addressed solely to the effect of the

Chisom Consent Decree under the supremacy clause. Their brief was a

restatement of one issue addressed and discussed by the State of

Louisiana.

As further evidence that the proposed intervenors are merely

minoring the State's action, one need only look to the pleadings the

intervenor attempted to file in the federal district court after the State of

Louisiana filed a motion to dismiss appellant's action on the basis of

mootness. (The dismissal order by the lower court is based upon

mootness and it is now the issue on appeal before this Court.) The

proposed intervenors, although not having been permitted to intervene, filed

"Defendant-Intervenors' Reply to the State's Motion and Incorporated

Memorandum to Dismiss." The second sentence of the memorandum

states:

3

"The defendant - intervenors agree with the views expressed

in the State's Motion and Incorporated Memorandum to

Dismiss."

The intervenors' memorandum makes no further assertion of law or legal

issues to support the State's motion to dismiss. One can only conclude

that the State of Louisiana has asserted the same issues which the

intervenors would have asserted had they been a party.

In these entire proceedings the proposed intervenors show no lack of

adequate representation by the State, nor do they assert any interest that

belongs uniquely to them as opposed to the State Louisiana, which would

give to them a direct right to maintain a defense over and above that

which could be asserted by the State of Louisiana.' The intervenors in

this matter address this Court in the same fashion as the intervenors did

in the matter of Keith v. Daley.3 In that particular case, the

constitutionality of an Illinois statute had been questioned and it was being

defended by the attorney general of the State of Illinois. The Illinois Pro-

Life Coalition, Inc. (IPC), sought to intervene in the action because of its

position that the Illinois act should be maintained in support of the Illinois

anti-abortion statute. The court in denying the motion to intervene, stated:

"Moreover the defendants in the instant case are duly

representing HB 1399. The IPC suggests that it is the

principal proponent of HB 1399, and that the defendants, while

'honorably committed to their duty of defending duly enacted

state legislation . . . cannot match the conviction and thorough

knowledge of the subject area held by the proposed intervenors

. . .' A subjective comparison, however, of the convictions

of defendants and intervenors is not the test for determining

the adequacy of representation. Adequacy can be presumed

2 Keith v. Daley, 764 F.2d 1265 (CA 7th Cir., 1985) at p. 1268.

3 id.

4

when the party on whose behalf the applicant seeks

intervention is a governmental body or officer charged by law

with representing the interest of the proposed intervenor. . . .

Moreover, we need not rely only on this presumption. The

record in this case indicates that the named defendants charged

by law with defending the laws of Illinois . . . have

adequately defended this suit." At p. 1270.

The proposed intervenors herein would allege that their interest

regarding the effects of Acts 1992, No. 512, are greater than that of the

State of Louisiana because this Act was the basis for the Chisom Consent

Decree in which they were the party plaintiffs. Yet as in Keith v. Daley,

the record reflects that the issues relative to the constitutionality of Acts

1992, No. 512, as asserted by the intervenors is no different than those

asserted by the State of Louisiana. The State of Louisiana, by law, can

and is defending the case vigorously, therefore, under the factors

considered for intervention pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 24 (a)(2) and the

presumed ability of the State to represent each citizen's interest on a state

constitutional matter, this intervention should be denied.

Respectfully Submitted:

Clement F. Prschall, Jr.

In Prpper Person

110 Veterans Boulevard

Suite 340

Metairie, LA 70005

Telephone: (504) 836-5975

5

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served a true and correct copy of the aforegone

on all counsel of record on this 23d day of March, 1998, as follows:

Peter J. Butler, Esq.

909 Poydras Street

Suite 2400

New Orleans, LA 70112

6

William P. Quigley, Esq.

Loyola University of

New Orleans

School of Law

7214 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70118

C. . Perschall, Jr.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR.

VERSUS

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

CIVIL ACTION NO.: 95-259

SECTION "B"

MAGISTRATE: (1)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ANSWER

NOW INTO COURT, through its undersigned counsel, comes defendant the State

of Louisiana who, in response to the Petition for Declaratory Judgment on the

Constitutionality of Acts 1992, No. 512 filed by plaintiff in this matter (the "Petition"),

removed to this Court on February 27, 1995, avers as follows:

I.

FIRST SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The Petition fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

SECOND SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in the Petition are barred by the doctrine of

accord and satisfaction.

THIRD SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The plaintiff is estopped from raising the issues and praying for the relief set forth

in his Petition.

Ey A.1.-1- j s-1-14ts Asa,

IV.

FOURTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the

doctrine of laches, liberative prescription, and/or any and all other applicable statutes of

limitations.

V.

FIFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the

doctrine of res judicata.

VI.

SIXTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Plaintiff has waived the issues raised and the relief prayed for in his Petition.

VII.

SEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act No. 512 of the 1992 regular Louisiana legislative

session, codified in La. R.S. § 13:312 and referred to throughout the Petition ("Act 512"),

comports and is consistent with, and does not violate any Article or Section of the Louisiana

Constitution of 1974, including, but not limited to, Article 3, Section 12(A), Article 3, Section

13, and Article 5, Section 3 of said Louisiana Constitution of 1974.

VIII.

EIGHTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any Article or Section of the United States Constitution.

IX.

NINTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE •

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any and all applicable laws.

X.

TENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any Article or Part of the Rules of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

XI.

ELEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant further avers that plaintiff lacks standing to raise the issues and relief

prayed for in his Petition.

XII.

TWELFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 is not a local or special law pursuant to the

Louisiana State Constitution of 1974, or any jurisprudence interpreting it..

AND NOW, in further response to the Petition, defendant avers as follows:

XIII.

Defendant admits the allegations set forth in Articles I, IX, XII, XIV, XV, XVI and

XVII of the Petition. XIV.

For lack of sufficient information to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations set forth in Articles II, XIII and XXIX of the Petition.

-3-

S

XV.

In response to Articles III, IV, V and VI of the Petition, defendant specifically avers

that Act 512 constitutes the best evidence of its contents and speaks for itself; moreover, the

statements set forth in said Articles constitute conclusions of law to which no response is

required; however, in an abundance of caution, defendant denies the statements set forth

in said Articles.

XVI.

The allegations in Articles XXXII, XXXVII, XLIV and XLVII require no response;

however, in an abundance of caution defendant deny the allegations in said Articles.

XVII.

Defendant denies the allegations set forth in Articles XXX, XXXI, XXXVI, XXXIX,

XLI, XLII, )(Lill, XLVI and XLVIII.

XVHI.

In response to Article VII of the Petition, defendant admits that Act No. 512 was

sponsored by Senators Jones and Morial; however, Act No. 512 was also sponsored by

Representatives Copeland, Landrieu, Murray and Singleton.

XIX.

In response to Article VIII of the Petition, defendant admits that a purpose of Senate

Bill No. 1255, as originally introduced by Senator Jones, was:

"to amend and re-enact R.S. 13:312(2)(B) and 312.1(B) relative

to thd courts and the judiciary; to divide the districts of certain

courts of appeal in this state into geographical election sections

for the purpose of qualification and election of appeal court

judges; to provide for the number of judges to be elected from

the sections of such districts; to provide relative to the terms of

office of certain appeal court district court judges; to provide

for effective date of these provisions; and to provide for related

matters."

-4-

XX.

In response to Article X of the Petition, defendant admits that on June 2, 1992, the

Senate Committee on Judiciary A convened during which Senate Bill No. 1255 of the 1992

Regular Session was discussed.

XXI.

In response to Article XI of the Petition, defendant admits that the Unapproved

Rough Verbatim Minutes of the Louisiana State Senate Committee on Judiciary A reflect

that Senator Marc Morial participated in a meeting of that Committee, a copy of which

Minutes attached to plaintiff's Petition as Exhibit C, constitute the best evidence of their

contents and speak for themselves.

XXII.

In response to Article XVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that Act 512 constitutes

and reflects the best evidence of its contents; accordingly, defendant denies the conclusions

set forth in said Article XVIII.

XXIII.

In response to Article XIX of the Petition, defendant admits that Marc Morial was

an original plaintiff in that case styled Chisom, et al v. Edwin Edwards in his Capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana, et al, bearing Civil Action No. 86-4075 on the docket

of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana ("Chisom"), for lack

of sufficient information upon which to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations in said Article that Marc Morial was a Senator of the State of

Louisiana at the time of the commencement of Chisom.

XXIV.

In response to Articles XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, and XL, defendant

avers that the record in Chisom represents the best evidence of its contents and the best

-5-

•

evidence of the allegations set forth in said Articles; accordingly, defendant denies said

Articles as written.

XXV.

In response to Article XXVI of the Petition, defendant denies the allegations as

written; in addition, defendant avers that references made in said Article to the consent

judgment rendered in Chisom, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit G to plaintiffs Petition,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVI.

In response to Article >OCVII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992, Senator

Morial introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session Senate Bill No. 39 which, inter alia,

sought to increase the number of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices to nine; defendant avers

that Senate Bill No. 39, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to plaintiff's Petition,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

In response to Article XXVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992,

Representative Morrell introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session House Bill No. 55

which, inter alia, sought to provide for the appointment by the Governor of an eighth Justice

to the Louisiana Supreme Court; defendant avers that House Bill No. 55, a copy of which

is attached is Exhibit I to plaintiff's Petition constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVIII.

In response to Article XXXIII of the Petition, defendant avers that Article 5, Section

3 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974 reads as follows:

"The supreme court shall be composed of a chief justice and six

associate justices, four of whom must concur to render

judgment. The term of a Supreme Court judge shall be ten

years."

-6-

XXIX.

In response to Article XXXIV of the Petition, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4

and Act 512 constitute the best evidence of their contents.

XXX.

In response to Article XXXV of the Petition, defendant avers that Louisiana Supreme

Court Rule IV, Part II constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXXI.

In response to Article )(XXVIII of the Petition, defendant admits the statements set

forth therein; however, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4, codifying Act 512, is not a

local or special law as such law is defined by the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

XXXII.

Defendant admits the statements set forth in Article XLV of the Petition; however,

defendant specifically denies that Act 512 is a local or special law, as such law is defined in

the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

WHEREFORE, defendant, the State of Louisiana, prays that the plaintiff's Petition

for Declaratory Judgment on the constitutionality of Act 1992, No. 512 be dismissed, with

prejudice, at plaintiff's costs, and that judgment be rendered herein in favor of the

defendant, the State of Louisiana, and against plaintiff for attorney's fees incurred by the

State of Louisiana and all other just and equitable relief to which the State of Louisiana is

entitled.

-7-

Respectfully submitted,

Peter J. Butler (Bar # 3731) - T.A.

Peter J. Butler, Jr. (Bar # 18522)

Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street - Suite 2400

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130-6036

Telephone.(504) 558-5100

BY:

. BUTLER, JR.

Special Counsel for Defendant the State of Louisiana

CERTIFICATE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the above and foregoing pleading has been

forwarded to Clement F. Perschall, Jr. by depositing a copy thereof, postage prepaid, in the

United States mail, addressed to him at One Galleria Boulevard, Galleria One, Suite 1107,

Metairie, Louisiana 70001, on this Q.Z day of Marc s 1995.

BY:

P TER J. BU R, JR.

-8-

•

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR nu EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

CLEMENT F. PERSHCHALL, JR.,

Plaintiff,

vs.

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA,

Defendant,

and

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

CIVIL ACTION NO.: 95-1265

SECTION "A"

MAGISTRATE: 2

ANSWER OF DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS

Defendant-intervenors Ronald Chisom, et al., by their undersigned counsel, answers the

Petition for Declaratory Judgment on the Constitutionality of Acts 1992, No. 512, filed by plaintiff

in this matter (the "Petition") removed to this Court on February 27, 1995, as follows:

I.

FIRST DEFENSE

The Petition fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

SECOND DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiff's Petition are barred by the doctrine of

laches and/or any and all other applicable statutes of limitations.

THIRD DEFENSE

Plaintiff lacks standing to maintain this action or to receive the relief sought by it.

4. ) 21.e ve.„),-1- 41414e-

.

FOURTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act No. 512 of the 1992 regular Louisiana legislative session,

codified in La. R.S. § 13:312 and referred to throughout the Petition ("Act 512"), comports and is

consistent with, and does not violate any Article or Section of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974,

including, but not limited to, Article 3, Section 12(A), Article 3, Section 13, and Article 5, Section

3 of said Louisiana Constitution of 1974.

1-1.F1H DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does not violate

an Article or Section of the United States Constitution.

• V.

SIXTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does not violate

any and all applicable laws, or any Article or Part of the Rules of the Louisiana Supreme Court, and

that Act 512 is not a local or special law pursuant to the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974, or any

jurisprudence interpreting it.

VI.

SEVENTH DEFENSE

Defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512 was passed to comply with the judgment of the

Eastern District of•Louisiana, as embodied in the Consent Decree entered by that Court in the case

of Chisom v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-4075, and therefore is legal, valid, and binding under

the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, any law of the State of Louisiana

notwithstanding.

ANSWERING SPECIFICALLY THE ALLEGATIONS OF THE PETITION, defendant-

intervenors allege and say:

2

VII.

Defendant-intervenors admit the allegations set forth in Articles I, a, xiv, a, XVI and

XVII of the Petition.

For lack of sufficient information to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant-

intervenors denies the allegations set forth in Articles II, XII, and XXIX of the Petition.

VIII.

In response to Articles III, IV, V and VI of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Act

512 constitutes the best evidence of its contents and speaks for itself; moreover, the statements set

forth in said Articles constitution conclusions of law to which no response is required; however,

defendant-intervenors deny the statements set forth in said Articles.

IX.

The allegations in Articles XXXII, =WU, XLIV and XLVII require no response; however,

defendant-intervenors deny the allegations in said Articles.

X.

Defendant-intervenors deny the allegations set forth in Articles XXX, XXI, XXVI, XXXIX,

XLI, XLII, XLffl, XLVI and XLVIII.

In response to Article VII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that Act No. 12 was

sponsored by Senators Jones and Morial; however, Act No. 512 was also sponsored by

Representatives Copelin, Landrieu, Murray and Singleton.

XII.

In response to Article VIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that a purpose of

Senate Bill 1255, as originally introduced by Senator Jones, was:

to amend and re-enact R.S. 13:312(2)(B) and 312.1(B) relative to the courts and the

3

judiciary; to divide the districts of certain courts of appeals into geographical election

sections for the purpose of qualification and election of appeal court judges; to

provide for the number of judges to be elected from the sections of such districts; to

provide relative to the terms of office of certain appeal court district court judges; to

provide for effective date of these provisions; and to provide for related matters.

XIII.

In response to Article X of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that on June 2, 1992,

the Senate Committee on Judiciary A convened during which Senate Bill No. 1255 of the 1992

Regular Session was discussed.

XIV.

In response to Article XI of the petition, defendant-intervenors admit that the Unapproved

Rough Verbatim Minutes of the Louisiana Senate Committee on Judiciary A reflect that Senator Marc

Morial participated in a meeting in a meeting of that Committee, a copy of which Minutes attached

to plaintiff's Petition as Exhibit C, constitute the best evidence of their contents and speak for

themselves.

XV.

In response to Article XVIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Act 512

constitutes and reflects the best evidence of its contents; accordingly, defdendants deny the

conclusions set forth in said Article XVIII.

XVI.

In response to-Article XIX of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit that Marc Morial was

an original plaintiff in Chisom. et al. v. Edwin Edwards, et al., E.D. La. Civil Action No. 86-4075

(Chisom).

XVII.

In response to Articles XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, and XL, defendant-intervenors

aver that the record in Chisom represents the best evidence of its contents and the best evidence of

4

•

the allegations set forth in said Articles; accordingly, defendant-intervenors deny said Articles as

written.

XVIII.

In response to Article XXVI of the Petition, defendant-intervenors deny the allegations as

written; in addition defendant-intervenors aver that the consent judgment rendered in Chisom, a

copy of which is attached as Exhibit G to plaintiffs' Petition and as Exhibit A to this answer,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents. Defendant-intervenors further aver that Act 512 was

passed for the specific purpose of complying with the provisions of the Consent Decree in Chisom

and its provisions are embodied in and incorporated into the judgment of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana as a result of that Court's approval of the Consent Decree

in Chisom.

XIX.

In response to Article XXVII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that in 1992, Senator

Morial introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session Senate Bill No. 39 which, inter alia, sought

to increase the number of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices to nine; defendant-intervenors aver that

Sente Bill No. 39, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to plaintiff's Petition, constitutes the best

evidence of its contents.

)0C.

In response to - Article XXVII/ of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that in 1992,

Representative Morrell introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session House Bill No. 55 which,

inter alia, sought to provide for the appointment by the Governor of an eighth Justice to the

Louisiana Supreme Court; defendant-intervenors aver that House Bill No. 55, a copy of whioch is

attached as Exhibit I to plaintiff's petition constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXI.

5

•

In response to Article XXXII' of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Article 5,

Section 3 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974 reads as follows:

The supreme court shall be composed of a chief justice and six associate justices,

four of whom must concur to render judgment. The term of a Supreme Court judge

shall be ten years.

In response to Article XXXIV of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that La. R.S.

13:312.4 and Act 512 constitute the best evidence of their contents.

XXIII.

In response to Article XXXV of the Petition, defendant-intervenors aver that Louisiana

Supreme Court Rule IV, Part II constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXIV.

In response to Article )(XXVIII of the Petition, defendant-intervenors admit the statements

set forth therein; however, defendant-intervenors aver that La. R.S. 13:312.4, codifying Act 512,

is not a local or special law as such law is defined by the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

XXV.

Defendant-intervenors admit the statements set forth in Article XLV of the Petition; however,

defendant-intervenors deny that Act 512 is a local or special law, as such law is defined in the

Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

WHEREFORE; defendant-intervenors Ronald Chisom, et al., pray that the plaintiffs Petition

for Declaratory Judgment on the constitutionality of Act 1992, No. 512 be dismissed, with prejudice,

at plaintiff's costs, and that judgment be rendered herein in favor of the defendant-intervenors.

6

_ •

111\14

r e

• RE4 4111R 3 0 1998

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 98-30004

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR.

V.'

THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

Plaintiff-Appellant

Defendant-Appellee

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

HONORABLE CHARLES SCHWAR17, JR.

OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO INTERVENE AS APPELLEES

ON BEHALF OF RONALD CHISOM, ET AT.

MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT:

Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, Henry Dillon, III,

and the Louisiana Voter Registration/Education Crusade have moved this

Court to intervene as appellees in this matter, notwithstanding the fact that

they have not previously been parties to the federal lower court

proceeding. However, it is acknowledged that when the case was

remanded to state court that under the procedural rules of the State of

Louisiana the aforesaid parties did participate. But as the record will

reflect their participation was nothing more than to mirror the pleadings

filed by the State of Louisiana. Their presence in the suit added only

additional bodies to reinforce the position of the State of Louisiana.

The proposed intervenors correctly note that the State of Louisiana is

presumed to provide an adequate representation on behalf of its citizenry.

Further, it is the State of Louisiana and only the State of Louisiana which

is legally bound to defend an act of the legislature.' The attorney general

has exercised his right and obligation to defend this matter and has

retained six outside attorneys in addition to his own staff to assist in the

defense of this matter. The proceedings have been long and arduous,

attesting to the adequacy of the defense by the State of Louisiana. The

numerous motions and briefs filed on behalf of the State of Louisiana in

both the state proceedings and the federal district court attest to that fact.

The intervenors allege that because they are parties to the Chisom

Consent Decree that only they will vigorously defend this action

irrespective that the State of Louisiana is also a party to the Chisom

Consent Decree. But their zeal is not a basis for their participation.

Further, the prorio-Sed intervenors have asserted no unique interest in this

case as opposed to the State of Louisiana and the records of these

proceedings will support this conclusion. The Court need only compare

the answer filed by the intervenors to the appellant's petition for

1 La. CONST. art. 4, § 8.

2

L-

declaratory judgment with the answer filed by the State of Louisiana.

These answers are virtually identical to one another, including the exact

wording in most of the responses. (See the enclosed Exhibit 1.)

Not only did the proposed intervenors allege no new defenses or

raise no new issues by their answer, but their brief before the Louisiana

Supreme Court was nothing more than a reiteration of the argument made

by the State of Louisiana, ie., that the Chisom Consent Decree, being a

federal court order, preempted the ability of the Louisiana courts to decide

the constitutional issue of Acts 1992, No. 512, under the supremacy clause

of the United States Constitution. Although the State of Louisiana raised

several additional issues regarding the legality of Acts 1992, No. 512, the

proposed intervenors brief was addressed solely to the effect of the

Chisom Consent Decree under the supremacy clause. Their brief was a

restatement of one issue addressed and discussed by the State of

Louisiana.

As further evidence that the proposed intervenors are merely

minoring the State's action, one need only look to the pleadings the

intervenor attempted to file in the federal district court after the State of

Louisiana filed a motion to dismiss appellant's action on the' basis of

mootness. (The'dismissal order by the lower court is based upon

mootness and it is now the issue on appeal before this Court.) The

proposed intervenors, although not having been permitted to intervene, filed

"Defendant-Intervenors' Reply to the State's Motion and Incorporated

Memorandum to Dismiss." The second sentence of the memorandum

states:

3

"The defendant - intervenors agree with the views expressed

in the State's Motion and Incorporated Memorandum to

Dismiss."

The intervenors' memorandum makes no further assertion of law or legal

issues to support the State's motion to dismiss. One can only conclude

that the State of Louisiana has asserted the same issues which the

intervenors would have asserted had they been a party.

In these entire proceedings the proposed intervenors show no lack of

adequate representation by the State, nor do they assert any interest that

belongs uniquely to them as opposed to the Stare Louisiana, which would

give to them a direct right to maintain a defense over and above that

which could be asserted by the State of Louisiana...2 The intervenors in

this matter address this Court in the same fashion as the intervenors did

in the matter of Keith v. Daley.' In that particular case, the

constitutionality , of an Illinois statute had been questioned and it was being

defended by the attorney general of the State of Illinois. The Illinois Pro-

Life Coalition, Inc. (IPC), sought to intervene in the action because of its

position that the Illinois act should be maintained in support of the Illinois

anti-abortion statute. The court in denying the motion to intervene, stated:

"Moreover the defendants in the instant case are duly

representing HB 1399. The 1PC suggests that it is the

pnncipal py_o_ponent of HB 1399, and that the defendants, while

'honorably committed to their duty of defending duly enacted

state legislation . . . cannot match the conviction and thorough

knowledge of the subject area held by the proposed intervenors

* , . . A subjective comparison, however, of the convictions

of defendants and intervenors is not the test for determining

the adequacy of representation. Adequacy can be presumed

2 Keith v. Daley, 764 F.2d 1265 (CA 7th Cir., 1985) at p. 1268.

3 id.

4

when the party on whose behalf the applicant seeks

intervention is a governmental body or officer charged by law

with representing the interest of the proposed intervenor. . . .

Moreover, we need not rely only on this presumption. The

record in this case indicates that the named defendants charged

by law with defending the laws of Illinois . . . have

adequately defended this suit." At p. 1270.

The proposed intervenors herein would allege that their interest

regarding the effects of Acts 1992, No. 512, are greater than that of the

State of Louisiana because this Act was the basis for the Chisom Consent

Decree in which they were the party plaintiffs. Yet as in Keith v. Daley,

the record reflects that the issues relative to the constitutionality of Acts

1992, No. 512, as asserted by the intervenors is no different than those

asserted by the State of Louisiana. The State of Louisiana, by law, can

and is defending the case vigorously, therefore, under the factors

considered for intervention pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 24 (a)(2) and the

presumed ability of the State to represent each citizen's interest on a state

constitutional matter, this intervention should be denied.

Respectfully Submitted:

Clement F. rerschall, Jr.

In Proper Person

110 Veterans Boulevard

• Suite 340 -

Metairie, LA 70005

Telephone: (504) 836-5975

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served a true and correct copy of the aforegone

on all counsel of record on this 23d day of March, 1998, as follows:

Peter J. Butler, Esq.

909 Poydras Street

Suite 2400

New Orleans, LA 70112

6

• William P. Quigley, Esq.

Loyola University of

New Orleans

School of Law

7214 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70118

••

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

CLEMENT F. PERSCHALL, JR . CIVIL ACTION NO.: 95-259

VERSUS

THE .STATE OF LOUISIANA

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ANSWER

SECTION "B"

MAGISTRATE: (1)

NOW INTO COURT, through its undersigned counsel, comes defendant the State

of Louisiana who, in response to the Petition for Declaratory Judgment on the

Constitutionality of Acts 1992, No. 512 filed by plaintiff in this matter (the "Petition"),

removed to this Court on February 27, 1995, avers as follows:

I.

FIRST SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The Petition fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

SECOND SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in the Petition are barred by the doctrine of

accord and satisfaction.

THIRD SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The plaintiff is estopped from raising the issues and praying for the relief set forth

in his Petition.

EY A.1.4- I— s-114t's Asut.,

IV.

FOURTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiffs Petition are barred by the

doctrine of laches, liberative prescription, and/or any and all other applicable statutes of

limitations.

V.

FIFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

The issues raised and relief prayed for in plaintiffs Petition are barred by the

doctrine of res judicata.

VI.

SIXTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Plaintiff has waived the issues raised and the relief prayed for in his Petition.

VII.

SEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act No. 512 of the 1992 regular Louisiana legislative

session, codified in La. R.S. § 13:312 and referred to throughout the Petition ("Act 512"),

comports and is consistent with, and does not violate any Article or Section of the Louisiana

Constitution of 1974, including, but not limited to, Article 3, Section 12(A), Article 3, Section

13, and Article 5, Section 3 of said Louisiana Constitution of 1974.

VIII.

EIGHTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any Article or Section of the United States Constitution.

IX.

NINTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any and all applicable laws.

X.

TENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 comports and is consistent with, and does

not violate any Article or Part of the Rules of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

XI.

ELEVENTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

Defendant further avers that plaintiff lacks standing to raise the issues and relief

prayed for in his Petition.

XII.

TWELFTH SPECIAL AND AFFIRMATTVE DEFENSE

Defendant specifically avers that Act 512 is not a local or special law pursuant to the

Louisiana State Constitution of 1974, or any jurisprudence interpreting it..

AND NOW, in further response to the Petition, defendant avers as follows:

XIII.

Defendant admits the allegations set forth in Articles I, IX, XII, XIV, XV, XVI and

XVII of the Petitioni— XIV.

For lack of sufficient information to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations set forth in Articles II, XIII and XXIX of the Petition.

-3-

XV.

In response to Articles III, IV, V and VI of the Petition, defendant specifically avers

that Act 512 constitutes the best evidence of its contents and speaks for itself; moreover, the

statements set forth in said Articles constitute conclusions of law to which no response is

required; however, in an abundance of caution, defendant denies the statements set forth

in said Articles.

XVI.

The allegations in Articles XXXII, XXXVII, XLIV and XLVII require no response;

however, in an abundance of caution defendant deny the allegations in said Articles.

XVII.

Defendant denies the allegations set forth in Articles XXX, XXXI, XXXVI, >00CDC,

XLI, XLII, XLIII, XLVI and XLVIII.

XVIII.

In response to Article VII of the Petition, defendant admits that Act No. 512 was

sponsored by Senators Jones and Morial; however, Act No. 512 was also sponsored by

Representatives Copeland, Landrieu, Murray and Singleton.

XIX.

In response to Article VIII of the Petition, defendant admits that a purpose of Senate

Bill No. 1255, as originally introduced by Senator Jones, was:

"to amend and re-enact R.S. 13:312(2)(B) and 312.1(B) relative

to thd courts and the judiciary; to divide the districts of certain

courts of -appeal in this state into geographical election sections

for the purpose of qualification and election of appeal court

judges; to provide for the number of judges to be elected from

the sections of such districts; to provide relative to the terms of

office of certain appeal . court district court judges; to provide

for effective date of these provisions; and to provide for related

matters."

-4-

•

XX.

In response to Article X of the Petition, defendant admits that on June 2, 1992, the

Senate Committee on Judiciary A convened during which Senate Bill No. 1255 of the 1992

Regular Session was discussed.

XXI.

In response to Article XI of the Petition, defendant admits that the Unapproved

Rough Verbatim Minutes of the Louisiana State Senate Committee on Judiciary A reflect

that Senator Marc Morial participated in a meeting of that Committee, a copy of which

Minutes attached to plaintiff's Petition as Exhibit C, constitute the best evidence of their

contents and speak for themselves.

In response to Article XVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that Act 512 constitutes

and reflects the best evidence of its contents; accordingly, defendant denies the conclusions

set forth in said Article XVIII.

XXIII.

In response to Article XIX of the Petition, defendant admits that Marc Morial was

an original plaintiff in that case styled Chisom, et al v. Edwin Edwards in his Capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana, et al, bearing Civil Action No. 86-4075 on the docket

of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana ("Chisom"); for lack

of sufficient information upon which to justify a belief as to the truth thereof, defendant

denies the allegations -in 'said Article that Marc Morial was a Senator of the State of

Louisiana at the time of the commencement of Chisom.

XXIV.

In response to Articles XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, and XL, defendant

avers that the record in Chisom represents the best evidence of its contents and the best

-5-

•

evidence of the allegations set forth in said Articles; accordingly, defendant denies said

Articles as written.

XXV.

In response to Article XXVI of the Petition, defendant denies the allegations as

written; in addition, defendant avers that references made in said Article to the consent

judgment rendered in Chisom, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit G to plaintiff's Petition,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

• XXVI.

In response to Article XXVII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992, Senator

Morial introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session Senate Bill No. 39 which, inter alia,

sought to increase the number of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices to nine; defendant avers

that Senate Bill No. 39, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to plaintiff's Petition,

constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVII.

In response to Article XXVIII of the Petition, defendant avers that in 1992,

Representative Morrell introduced to the 1992 regular legislative session House Bill No. 55

which, inter alia, sought to provide for the appointment by the Governor of an eighth Justice

to the Louisiana Supreme Court; defendant avers that House Bill No. 55, a copy of which

is attached is Exhibit I to plaintiff's Petition constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXVIII.

In response to_Article XXXIII of the Petition, defendant avers that Article 5, Section

3 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974 reads as follows:

"The supreme court shall be composed of a chief justice and six

associate justices, four of whom must concur to render

judgment. The term of a Supreme Court judge shall be ten

years."

-6-

XXIX.

In response to Article XXXIV of the Petition, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4

and Act 512 constitute the best evidence of their contents.

XXX.

In response to Article XXXV of the Petition, defendant avers that Louisiana Supreme

Court Rule IV, Part II constitutes the best evidence of its contents.

XXXI. - •

In response to Article XXXVIII of the Petition, defendant admits the statements set

forth therein; however, defendant avers that La. R.S. 13:312.4, codifying Act 512, is not a

local or special law as such law is defined by the Louisiana State Constitution of 1974.

XXXII.

Defendant admits the statements set forth in Article XLV of the Petition; however,