Briggs v. Elliot Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Reply Brief for Appellants, 1952. cca05975-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/30b0d44b-0295-420a-9873-fab674707f84/briggs-v-elliot-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

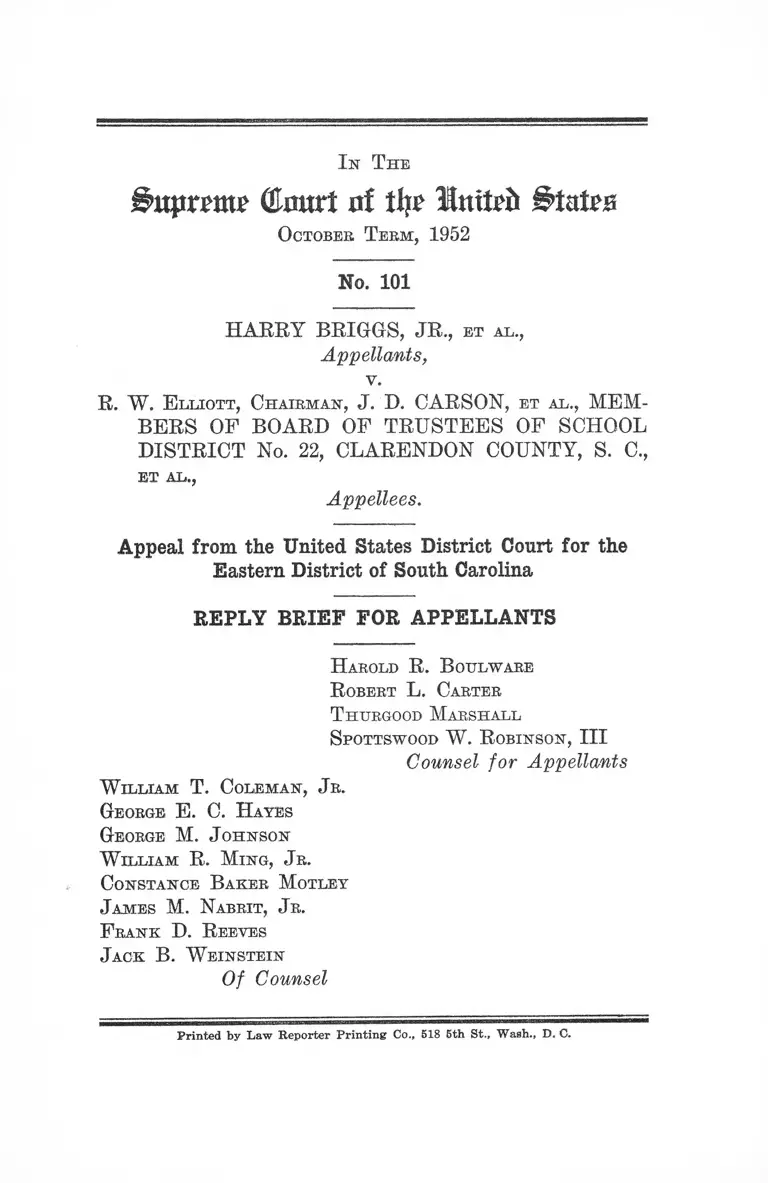

I n T he

IhtprattF (Emtrt nf Mnxtxb Btattz

O ctober T e em , 1952

No. 101

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al .,

Appellants,

v .

R. W. E lliott , Ch a ir m a n , J . I). CARSON, et al ., MEM

BERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL

DISTRICT No. 22, CLARENDON COUNTY, S. C.,

ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

H arold R . B oulware

R obert L. Carter

T hurgood M arshall

S pottswood W. R obinson , III

Counsel for Appellants

W illia m T. C olem an , J r.

George E . C. H ayes

George M . J ohnson

W illia m R. M in g , J r.

C onstance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, J r.

F rank D. R eeves

J ack B . W e in s t e in

Of Counsel

P rin ted by Law R eporte r P r in tin g Co., 518 5th S t., W ash., D. C.

Page

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. 2d 391________________________________ 4

Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (CA 5, 1951), certiorari denied

341 U. S. 942 _________________ _______ ___________________ 6

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60______________________________ 6

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. I l l , 120___________________________ 3

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.. ________________________ 2

Elkinson v. Deliesseline, 8 Fed. Cas. 493 (1823)__________________ 5

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651, 665_________________________ 3

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 363______________________ 3

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81______________________ 2

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214______________________ 2

Lester v. Garnett, 258 U. S. 130, 136-137________________________ 3

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637____________3, 4, 6

Missouri Ex Rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337________________ 3

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373_____________________________ 5

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 389____________________________ 3

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536_______________________________ 2

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387, certiorari denied, 333 U. S. 875______ 4

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1_______________________________ 6

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535___________________________ 2

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192... ________________ 2

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 307___________________ 3

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629_____ __ ___ ____________________ 3

Other Citation

57 Harvard Law Review, 328, 338-------------------------------------------- 5

TABLE OF CASES

I n T hr

Buptm? CfJmtrt uf thr Hutton States

O ctober T er m , 1952

No. 101

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

R. W. E llio tt , Ch a ir m a n , J. D. CARSON, e t al., MEM

BERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL

DISTRICT No. 22, CLARENDON COUNTY, S. C.,

ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

I .

A major part of the brief of appellees is an attempt to

sustain the amazing proposition which they state this way:

“ The District Court correctly held that the conflict

of opinion regarding the effects of segregation and its

abolition present questions of legislative policy and not

of constitutional r i g h t (Emphasis added.)

This proposition is amazing in its bald assertain that, if

a state decides that its continuing imposition of segregation

is desirable, there is no issue for the independent decision

of this Court as to whether segregation can be squared with

equal protection of the laws. We think it a sufficient answer

2

to this contention to point out that it is no more or less than

a denial that the doctrine of judicial supremacy extends to

the Constitutional characterization of state action in the or

ganization of public education. Thus, appellees’ argument

is a negation of the very postulates and whole history of

constitutional government in the United States.

Actually, this case invites such authoritative exposition

and decision as only this Court can give upon the meaning

and requirements of “ equal protection of the laws” in the

organization of public education, and the consistency or

inconsistency of the presently challenged state imposition

with those requirements.

This process is aided by the historic fact that the Four

teenth Amendment represents an effort permanently to

debar the states from imposing disadvantages upon indi

viduals because of their race or ancestry. In contemporary

recognition of this constitutional purpose opinions of this

Court have more than once indicated that our civilization

has advanced to the point where all governmentally im

posed race distinctions are so odious that a state, bound to

afford equal protection of the laws, must not impose them.

See: Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536; Edward v. California

(concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Jackson), 314 U.S. 160;

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535; cf: Hirabayashi v.

United States, 320 U.S. 81; Korematsu v. United States,

323 U.S. 214; Steele v. Louisville <& N.R. Co., 323 U.S. 192.

There is a short, hut decisive answer to appellees’ argu

ment that the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment is

fixed by the racial practices that existed in various states at

the time the Amendment was adopted. Most of the states

which required segregation in public schools at the time

of ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth

also restricted the right to vote and the right of jury serv

ice to white citizens. As to these rights this Court has con

sistently held that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments effectively struck the qualifying word “ white” from

3

these state statutes. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303, 307; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370, 389; Bush v. Ken

tucky, 107 U.S. 111, 120; Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S.

347, 363; See also: Exparte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651, 665;

Lester v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130, 136-137.

II.

In the organization of public education state imposed

racism has taken different forms and has placed the in

dividual at various disadvantages. This Court considered

fifteen years ago the situation in which a state required its

Negro citizens to go outside its borders for particular train

ing, albeit training as good or better, except for geography,

as that afforded locally to white citizens. The Court did

not find it difficult to strike down this imposition of educa

tional disadvantage on racial basis as a denial of equal pro

tection. Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337.

The same conclusion was reached when it was found dis

advantageous to Negroes training for the legal profession

to be separated in training from white persons in or pre

paring for the same public calling. Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U.S. 629. Even the circumstances of state imposed racial

separation in a single classroom have been found disadvan

tageous to the extent of denying equal protection. Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637.

So here the evidence shows the real and substantial dis

advantages which are and must continue to be suffered by

the Negro children of Clarendon County so long as the state

shall require that because of race they be trained separate

and apart from the rest of the children of the community.

On the record the proof of these disadvantages is nowhere

challenged, much less countered. While we believe this

Court has treated such demonstrable disadvtanges im

posed upon Negro students as unconstitutional in any cir

cumstances, they are made the more clearly intolerable be

cause this injury of the segregated persons serves no edu

4

cational purpose and results from distinctions which in

their nature are alien and odious to a democratic and

equalitarian society such as ours.

To offset these considerations the state urges at most

that it means well; that certain disturbances of community

tranquility are anticipated if racial segregation is not re

quired in the public schools and that prevailing sentiment

is so strongly in favor of the present arrangement that so

cially dangerous resentments would be aroused by a change.

This is said to he established on the record by the testimony

of one witness that a change in the segregated pattern would

be ‘ ‘ unwise ’ ’ at this time and, off the record, by quotations

from several speeches and newspaper articles of distin

guished persons. Accordingly, appellees ask this Court to

recognize that South Carolina is not being arbitrary in its

determination that a substantial public interest is served

by racial segregation in its public schools. They then argue

that the legislature may continue the system which it thus

regards as serving a public interest, whatever incidental

injury may be suffered by the segregated Negroes. The

only recourse left to the appellants is patience, waiting until

there shall he change of heart by the majority of the popu

lation so apparent as to convince the South Carolina Legis

lature that it should abolish the school segregation laws.1

This entire contention is tantamount to saying that the

vindication and enjoyment of constitutional rights recog

nized by this Court as present and personal can be post

poned wherever such postponement seems in the general

community interest. We need go no further than McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra, to learn that this exalta

tion of local policy over fundamental individual right is as

declared in the national Constitution not tolerable in the

United States.

1 In view of South Carolina’s disregard of right of Negroes to vote,

Rice V. Elmore, 165 P. 2d 387, cert. den. 333 TJ.S. 875 and Baskin v.

Brown, 174 F. 2d 391, even the normal political influences of opponents

of particular legislature are not here present.

5

And there are striking and persuasive analogies in other

situations where local policy has been urged to minimize

or override individual constitutional right. More than a

hundred years ago South Carolina attempted to prevent the

free movement of Negro seamen into and about its seaport

cities on the ground that domestic order and tranquility

required their exclusion. Mr. Justice Johnson,2 sitting on

Circuit in South Carolina in 1823 did not hesitate to over

rule this defense and condemn the restriction as unconstitu

tional. Elkinson v. Deliesseline, 8 Fed. Cas. 493 (C.C.S.C.

1823). The question there involved a South Carolina stat

ute requiring the imprisonment of free Negro sailors on

ships tied up in the harbor of Charleston. Much the same

argument as presented by appellees in this ease was pre

sented on behalf of the statute in the Elkinson case. Mr.

Justice Johnson disposed of this argument as follows:

“ But to all this the plea of necessity is urged; and

of the existence of that necessity we are told the state

alone is to judge. Where is this to land us ? Is it not

asserting the right in each state to throw off the federal

Constitution at its will and pleasure 1 If it can be done

as to any particular article it may be done as to all;

and, like the old confederation, the Union becomes a

mere rope of sand. . . . ” (At p. 496.)

More recently contentions that maintenance of peace and

order justified segregation of Negro interstate passengers,

did not justify what was found otherwise to be an unwar

ranted interference with commerce. Morgan v. Virginia,

328 U.S. 373. The present apprehensions of South Caro

lina have no better standing as impediments to appellants’

enjoyment of their constitutional right to be relieved of

special educational disadvantages to which the state has

subjected them because of their race.

As a matter of face, this argument by appellees is in

9 See: Mr. Justice William Johnson and the Constitution, 57 Harvard

Law Review 328, 338.

6

direct conflict with applicable decisions of this Conrt. In

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 this Court held:

“ That there exists a serious and difficult problem

arising from a feeling of race hostility which the law

is powerless to control, and to which it must give a

measure of consideration, may be freely admitted. But

its solution cannot be promoted by depriving citizens of

their constitutional rights and privileges.”

This rule has been cited with approval in later cases, Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1.

The case of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (C.A. 5,

1951), certiorari denied 341 U.S. 942, affirmed the decision

of the district court which excluded all efforts of the City

of Birmingham to justify a residential segregation ordi

nance on the ground that it was necessary to prevent

violence.

III.

The gravamen of the opinions of the District Court and

the brief for appellees is that as a matter of policy, legisla

tive or otherwise, the people of South Carolina desire that

all Negroes be excluded from the white schools and vice

versa. They also assert that the removal of racial segre

gation in public education will not be acceptable to the

people of South Carolina. The individual rights of the

appellants herein cannot be made dependent upon this rea

soning. This Court stated in the McLaurin case :

“ It may be argued that appellant will be in no better

position when these restrictions are removed, for he

may still be set apart by his fellow students. This we

think irrelevant. There is a vast difference—a Con

stitutional difference—between the restrictions im

posed by the state which prohibit the intellectual com

mingling of students, and the refusal of individuals to

commingle where the state presents no such bar.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 13, 14, 92 L. ed. 1161,

1180, 1181, 68 S.Ct. 836, 3ALR 2d 441 (1948). The

removal of the state restrictions will not necessarily

7

abate individual and group predilections, prejudices

and choices. But at the very least, the state will not

be depriving appellant of the opportunity to secure

acceptance by his fellow students on his own merits.”

It bears repeating that appellants in this case are seek

ing to remove the barrier of state imposed racial segrega

tion in the educational opportunities and benefits offered

by the state. If this barrier is removed, the state, counties

and school districts can then assign students on whatever

reasonable basis they deem advisable with the sole proviso

that race or color shall not be made the determining factor

in such assignment. By doing this, the racial groups in

South Carolina can work out their common problems with

out the individual opportunities of either group being sub

jected to the state imposed barrier of racial segregation.

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that, for the reasons stated herein

and in appellants’ initial brief, the decree of the District

Court should be reversed.

H arold R . B oulware

R obert L. Carter

T hurgood M arshall

S pottswood W . R obinson , III

Counsel for Appellants

W illia m T. C olem an , J r.

George E. C. H ayes

George M. J o h nson

W illia m R . M in g , J r .

C onstance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, J r.

F rank D. R eeves

J ack B. W e in s t e in

Of Counsel