Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Brief for Respondent Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Public Court Documents

January 26, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Brief for Respondent Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 1984. 1dfe8642-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/30e169d5-9869-4095-ae00-db1f87a14a17/cooper-v-federal-reserve-bank-of-richmond-brief-for-respondent-federal-reserve-bank-of-richmond. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

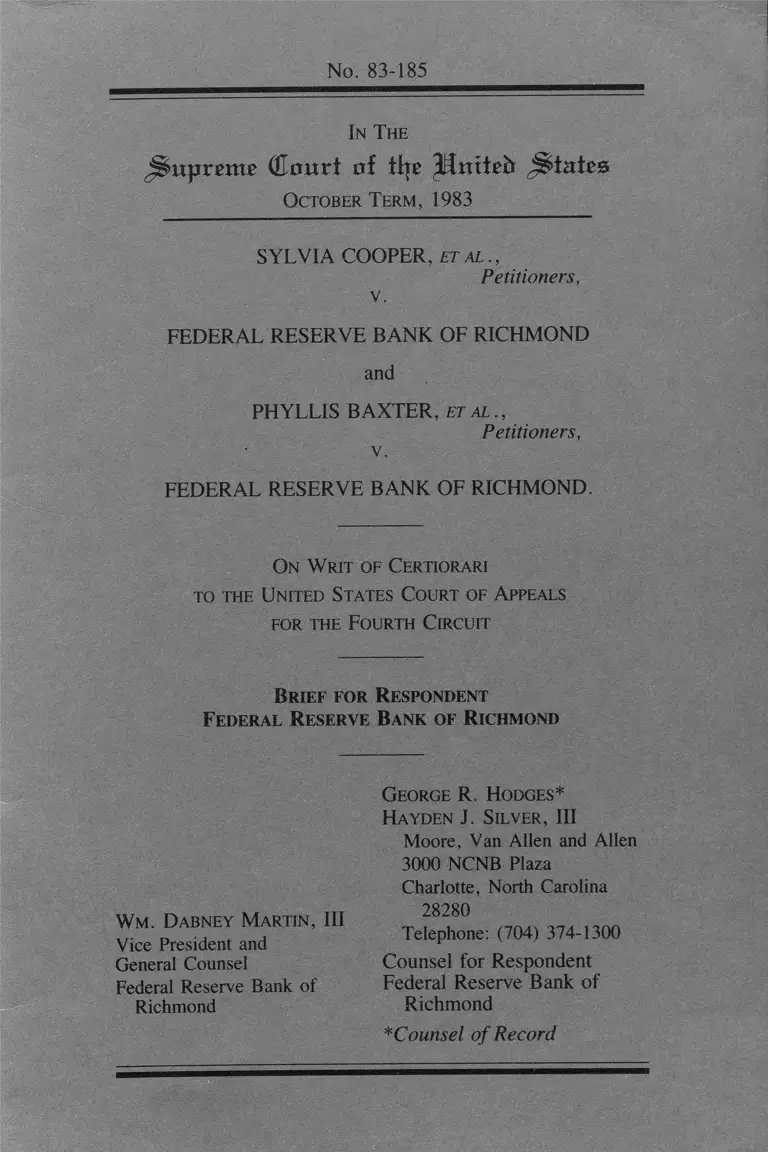

No. 83-185

In The

Supreme Court of ttje Pmtefr S tates

October Term, 1983

SYLVIA COOPER, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND

and

PHYLLIS BAXTER, et al .,

Petitioners,

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

Brief for Respondent

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Wm . Dabney Martin, III

Vice President and

General Counsel

Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond

George R. Hodges*

Hayden J. Silver, III

Moore, Van Allen and Allen

3000 NCNB Plaza

Charlotte, North Carolina

28280

Telephone: (704) 374-1300

Counsel for Respondent

Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond

*Counsel o f Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a judicial determination in a properly certified class

action will bind a class member, not opting out after notice, in

asserting thereafter an individual claim within the range of charges

determined in the class suit.1

1 The parties have stated the issue in this case in various ways. The

statement above is that of the Fourth Circuit in its decision below. [P.A.

177a],

t

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED............................................ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................ iv

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE........................................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.......... ............................. 4

ARGUMENT:

I. The Fourth Circuit Properly Ruled That

Petitioners Are Bound By The Adverse

Judgment In The Prior Class Action................. 6

1. Res Judicata................................................ 6

a. The Same Cause of Action................... 7

b. The Decision of the District Court. . . . 13

2. Rule 23 Bars Petitioners’ Claims............... 16

a. The Language and Intent of Rule 23 . . 16

b. Petitioners’ E lection............................. 18

c. The Practical Effect of

Petitioners’ E lection.............................. 21

d. Other Decisions of this Court

Involving Rule 2 3 .................................. 23

II. The Bank Did Not Acquiesce In Subsequent

Individual Actions And The District Court

Did Not Authorize Subsequent Actions.......... 24

III. The Claims of Petitioner H arrison................... 28

CONCLUSION.................................................................... 29

Page

ii

ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations are used in citation to various parts

of the Record in this action:

“J.A .” refers to the Joint Appendix filed in this Court

“P A.” refers to the Appendix to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

‘ I C.A. App.” refers to the Appendix in EEOC and Cooper in the

court of appeals

“II C.A. App.” refers to the Appendix in Baxter in the court of

appeals

“Tr.” refers to pages in the trial transcript in EEOC and Cooper

which were not made part of the Appendix in that action in the

court of appeals

“PX” refers to plaintiffs’ exhibits in the trial record of EEOC and

Cooper

“DX” refers to defendant’s exhibits in the trial record of EEOC and

Cooper

iii

Cases:

Allen v. McCurry,

448 U.S. 90 (1980).................................................. 6

American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah,

414 U.S. 538 (1974)...................................... 4, 17, 18, 21

23, 24

Balto. Steamship Co. v. Phillips,

274 U.S. 316 (1927)................................................ 7

Bogard v. Cook, 586 F.2d 399 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 444 U.S. 883 (1979)......................... 9

Coe v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc., 646

F.2d 444,449 n. 1 (10th Cir. 1981)......................... 11

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982)................. 18

Croker v. Boeing Co., 662 F.2d 975

(3d Cir. 1981)............................................................. 9

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker,

16 L. Ed. 2d 628 (1983)...................................... 17, 23, 24

Dalton v. Employment Security Comm’n,

671 F.2d 835 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 74 L. Ed. 2d 117 (1982)................... 9

Deposit Guaranty National Bank v. Roper, 445 U.S.

326 (1980).................................................................... 10, 22

Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp.,

582 F.2d 827 (3d Cir. 1978)..................................9, 24, 25

Dosier v. Miami Valley Broadcasting Corp.,

656 F.2d 1295 (9th Cir. 1981)................................ 8, 9

Eastland v. T .V .A ., 704 F.2d 613, modified in part,

714 F.2d 1066 (11th Cir. 1983)............................. 9

Edwards v. Boeing-Vertrol Co., I l l F.2d 761

(3d Cir.), petition for cert, fded, 52 U.S.L.W.

3463 (Nov. 29, 1983) (No. 83-902)....................... 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

IV

Page

Federated Department Stores v. Moitie,

452 U.S. 394 (1981)................................................. 6

Fowler v. Birmingham News Co., 608 F.2d 1055

(5th Cir. 1979)........................................................... 8, 9

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978)................................................. 18

General Telephone Co. v. EEOC,

446 U.S. 318 (1980)................................................. 24

General Telephone Co. v. Falcon,

457 U.S. 147 (1982) ......... ....................................... 17,18

Kemp v. Birmingham News Co., 608 F.2d 1049

(5th Cir. 1979)........................................................... 7, 8, 9

Marshall v. Kirkland, 602 F.2d 1282

(8th Cir. 1979)........................................................... 9

McDonnell-Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973).......................................................................... 10,11

Nevada v. United States, 11 L. Ed. 2d 509 (1983). . 6, 7

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). . . 10, 11

18, 21

Woodson v. Fulton, 614 F.2d 940 (4th Cir. 1980) . . 8, 9

Statutes and Rules:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 2 3 .....................................................4-6, 16-24

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1 -5 2 ................................................. 21

Miscellaneous:

Restatement (Second) of Judgments

§ 20(b)(1) (1982)....................................................... 26

Restatement (Second) of Judgments

§ 26(b)(1) (1982)....................................................... 27

v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action arises out of a race discrimination in employment class

action, EEOC and Sylvia Cooper, et al. v. Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond. The action was brought pursuant to Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq., and pursuant to 42

U.S.C. § 1981. The Respondent is the Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond, Charlotte (North Carolina) Branch (hereinafter “the

Bank”). At all times relevant to this action blacks represented over

30% of the Bank’s workforce — fifty percent greater than their repre

sentation in the relevant external labor market (about 20%). [P.A.

118a]. Moreover, the Bank promoted blacks at a rate greater than

their representation in its workforce and at a greater rate than whites

were promoted. [P.A. 121a]. The final judgment on the merits of the

class action was in favor of the Bank.

Petitioners in this court were the plaintiffs in Baxter, et al. v.

Federal Reserve Bank. They are all former class members in the

EEOC and Cooper class action. After an adverse ruling as to their

sub-class by the district court in the EEOC and Cooper action, they

filed individual claims in the subsequent Baxter action. The Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals held that those claims were barred by the

judgment in favor of the Bank in the class action.

The EEOC and Cooper action was initiated by the EEOC in

March 1977. The EEOC’s Complaint alleged race discrimination in

promotions in general and race and sex discrimination against

Cooper in particular. [J.A. 6a], Several months later Cooper and

three others intervened in the EEOC’s action for themselves and as

representatives of the class of all present and former employees of

the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Charlotte Branch. The

Complaint-in-Intervention alleged racial discrimination against the

four class representatives and against the class in initial job assign

ment, training, pay, discipline and promotion in all job grades. [J.A.

12a]. The Bank did not oppose this intervention.

In April 1978, the class was certified by the district court pursuant

to a Consent Order agreed upon by all the parties. [J.A. 24a]. By this

Consent Order, the class represented by the Cooper intervenors was

certified to include “all black persons who worked for the Federal

Reserve Bank of Richmond at its Charlotte Branch Office at any

1

2

time since January 3, 1974.” [J.A. 30a]. The EEOC was not certi

fied as a class representative, but agreed that the scope of the

persons for whom it sought relief for race discrimination was co

extensive with the definition of the class represented by the Cooper

intervenors. [J.A. 31a].

By the Consent Order the parties also agreed upon a Notice to be

sent to class members. [J.A. 30a-31a]. The Notice advised class

members of the class action, their membership in the class, their

right to remain class members or to opt out of the class, and the

consequences of each option. Specifically, the Notice advised class

members that:

If you decide to remain in this action, you should be

advised that: the court will include you in the class in this

action unless you request to be excluded from the class in

writing; the judgment in this case, whether favorable or

unfavorable to the plaintiff and the plaintiff-intervenors,

will include all members of the class; all class members

will be bound by judgment or other determination of this

action. . . .

That Notice was received by each of the Baxter Petitioners. [J.A.

95a]. None of these Petitioners made any attempt to opt out of the

class action.

After extensive discovery, the EEOC and Cooper class action

was tried to the district court in September 1980. The trial of the

class action was bifurcated upon consent of the parties. The major

issue at the trial was alleged discrimination in promotions. Petition

ers each testified at the trial in support of the class action about

various promotions which they allegedly had been denied. But they

never moved to intervene, even after the district court ruled that it

would hear their testimony only on the class issues.

Shortly after the trial, the district court issued a “Memorandum of

Decision.” [P.A. 91a]. The Memorandum of Decision stated the

district court’s opinion that that the Bank had discriminated against

two of the four individual claimants (Sylvia Cooper and Constance

Russell) and in promotions out of Grades 4 and 5 only, but no relief

relating to promotions out of Grades 6 and above was indicated.

3

Petitioners were employed in Grades 6 and above2 and, therefore,

were not members of the class which was awarded relief (i.e. blacks

denied promotions out of Grades 4 and 5). Four months after the

filing of the Memorandum of Decision, Petitioners sought to inter

vene in the class action. [J.A. 39a], Intervention was denied. [P.A.

286a], Petitioners then filed a separate action alleging individual

claims of discrimination. [J.A. 63a]. The Bank moved to dismiss

that action. [J.A. 71a]. The Motion was denied, but the district court

certified the question for interlocutory appeal. [J.A. 96a], The dis

trict court’s Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in EEOC and

Cooper were filed May 29, 1981. [P.A. 197a]. There the district

court defined the class as it had in the Consent Order and concluded

with respect to promotions in Grades 6 and above as follows:

The Court concludes that there was no showing that the

Bank had discriminated against black employees with

respect to promotions out of Grades 6 and above, and that

defendant did not violate Title VII or 42 U.S.C. §1981

with respect to promotions out of Grade 6 and above.

[P.A. 284a-285a],

The Bank appealed those portions of the EEOC and Cooper

judgment that were adverse to it and also appealed the district court’s

refusal to dismiss the Baxter action. Neither the EEOC nor the

plaintiff-class representatives appealed from the portions of the judg

ment adverse to them.

On appeal, the Fourth Circuit held in EEOC and Cooper that the

district court’s findings of discrimination against two of the named

individuals and in promotions out of Grades 4 and 5 were clearly

erroneous. [P.A. 2a-172a]. In Baxter, the Fourth Circuit held that

the adverse judgment in the EEOC and Cooper class action barred

the subsequent individual action. [P.A. 172-184a],

2Petitioner Ruffin was actually a Grade 5 employee [P.A. 246a-247a],

and thus at the time of the Motion to Intervene she was entitled to par

ticipate in Stage II of the class action.

4

I. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals properly ruled that Peti

tioners are bound by the adverse judgment in the prior class action.

After notice of their right to pursue their claims individually or to be

bound by the judgment in the class action, Petitioners elected to

litigate their claims through the Cooper class representatives and the

vehicle of the class action. Petitioners made no attempt to litigate

their claims individually until after they learned that the judgment in

the class action was adverse to them. Rather, they abided by their

election and pursued their claims as class members in the class action

through a decision on the merits. Consequently, they are bound by

that election and the adverse judgment in the class action.

The class action included the claims of racial discrimination in

promotions and resolved those claims against Petitioners’ class. The

fact that the class action was a “pattern and practice” action is

immaterial to res judicata principles because “pattern and practice”

is simply an alternative method of proof, not a separate and distinct

cause of action. Petitioners’ subsequent action involves the same

cause of action that was resolved in the prior class action. So, it was

properly barred by the doctrine of res judicata.

The language and intent of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 also requires that

the subsequent action be dismissed. The class action is specifically

designed for the adjudication in one action of “individual claims”

which are typical of one another and involve common questions of

law or fact. In fact, a class action is nothing but the aggregation of

the “individual claims” of class members. Here, the district court

found— upon Petitioners’ consent — that the class action was supe

rior to other available methods for fair and efficient adjudication of

the controversy. Consequently, the action was certified as a class

action pursuant to Rules 23(b) (2) and (b) (3). This Court noted in

American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538, 547-48

(1974), that Rule 23 was specifically amended in 1966 to bind class

members to the judgment in a class action and to prevent such

fence-sitting or “one-way intervention” as Petitioners attempt here.

The practical effect of the rule suggested by Petitioners would

destroy Rule 23 and the class action as a litigation vehicle. If these

Petitioners were permitted to file subsequent actions, then so could

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

5

all the 300 or so other class members. That would result in the

Bank— after prevailing on the merits in the class action — having to

defend multiple subsequent actions by former class members. Peti

tioners seek a rule that would permit them to participate in the class

action and: (i) if they prevailed, obtain a presumption in their favor;

and (ii) if they lost in the class action, nonetheless maintain a

subsequent action on their “individual claims.” Petitioners’ sub

mission is, in effect, that a class action amounts to a “no lose”

proceeding for class members and a “no win” proceeding for the

defendant. Such a result would render Rule 23 and the class action

meaningless.

Finally, there are many benefits that a class member receives by

litigating his claims in the class action — an increased chance of

success and economies of scale resulting from pooled resources.

But, those benefits are not totally one-sided. They involve a trade

off borne of judicial economy. That is, if the class action device is

to succeed in avoiding needless multiplicity of suits and to permit

adjudication of numerous claims in one suit, the judgment in the

class action must be binding on class members.

II. The district court did not expressly reserve Petitioners’ sub

sequent actions in ruling on their post-trial Motion to Intervene. At

most, the district court stated an opinion that Petitioners could file

a subsequent action — an erroneous opinion which was reversed by

the Fourth Circuit. Moreover, at the time of Petitioners’ Motion to

Intervene in EEOC and Cooper and the district court’s statements,

the court had already ruled against Petitioners’ class, so the Bank

was then entitled to a judgment against Petitioners.

III. Petitioner Harrison was actually a Grade 6 employee and not

a Grade 3 as mistakenly noted by both courts below. Consequently,

his position is no different than that of the other Petitioners.

IV. The rule that this Court should adopt is that: a properly

certified class action is made up of the “individual claims” of class

members, and those class members who, after notice, elect to liti

gate their claims in the class action are thereafter precluded from

re-litigating individual claims within the range of issues determined

in the class action. Consequently, the decision of the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit should be affirmed.

6

ARGUMENT

I. The Fourth Circuit Properly Ruled That

Petitioners Are Bound By The Adverse

Judgment In The Prior Class Action

The Bank submits that res judicata bars Petitioners’ claims in the

subsequent Baxter action. Petitioners knowingly elected to litigate

their “individual claims” of discrimination through the vehicle of the

EEOC and Cooper class action. They are therefore bound by the

judgment in that action and precluded from pursuing the claims

which they attempt to re-litigate in this subsequent action. Their

subsequent action is also barred by the language and intent of Fed.

R. Civ. P. 23. Binding Petitioners to their election is particularly

appropriate here because they are classic “fence sitters” who seek in

the Baxter action a second chance to litigate their claims. Finally,

the practical effect of Petitioners’ submission would be to render

Rule 23 and the class action meaningless.

1. Res Judicata

The doctrine of res judicata provides that a “final judgment on the

merits of an action precludes the parties or their privies from re

litigating issues that were or could have been raised in that action.”

Federated Department Stores v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394, 398 (1981);

see also Nevada v. United States, 77 L. Ed. 2d 509 (1983); Allen v.

McCurry, 448 U.S. 90 (1980). Whether Petitioners’ claims are

barred by res judicata turns on whether the cause of action asserted

in the EEOC and Cooper class action was the “same cause of action”

that Petitioners seek to assert here. Nevada v. United States, 77 L.

Ed. 2d at 525.

The test for whether a subsequent action is barred by res judicata

does not center on the evidence presented. Rather, it focuses on the

violation of a right which the evidence shows. This Court has stated

the analysis as follows:

A cause of action does not consist of facts, but of the

unlawful violation of a right which the facts show. The

number and variety of the facts alleged do not establish

more than one cause of action so long as their result,

whether they be considered severally or in combination,

7

is the violation o f but one right by a single legal wrong.

The mere multiplication of grounds of negligence alleged

as causing the same injury does not result in multiplying

the causes of action.

Balto. Steamship Co. v. Phillips, 274 U.S. 316, 321 (1927)

(Emphasis added), cited with approval, Nevada v. United States, 77

L. Ed. 2d at 525 n. 12.

In the present case, the individual claims of each Petitioner stated

in their Complaint relate solely to their failure to receive certain

promotions. [J.A. 65a-66a]. The denial of these promotions is pre

cisely what each Petitioner previously testified about in the trial of

the class action. [I C.A. App. 452-688], Similarly, the violation

of the right is the same as in the prior class action— alleged denial

of promotions because of their race. That is precisely the “right” that

was litigated in the EEOC and Cooper class action and resolved

against Petitioners. Consequently, this subsequent action is barred

by principles of res judicata and the binding effect of the class action

judgment.

Petitioners concede that a class action judgment on the merits of

an issue precludes re-litigation of that issue. But, they attempt to

escape that principle by asserting that the EEOC and Cooper class

action did not include the individual claims of Petitioners. The Bank

submits that: (a) the pattern and practice issue in the class action

encompassed Petitioners’ individual claims and, thus, their sub

sequent action involved the “same cause of action” and is barred by

res judicata; and (b) the prior class action involved the issue of

discrimination in promotions and concluded in the district court with

a determination that the Bank had not discriminated against Peti

tioners’ class in promotions.

a. The “Same Cause o f Action”

A class member’s “individual claims” are encompassed in the

class action and thus represent the “same cause of action” and may

not be re-litigated.

Several circuit court decisions have established this rule. In Kemp

v. Birmingham News Co., 608 F.2d 1049 (5th Cir. 1979), the

plaintiff sought to raise personal claims for harassment and demotion

8

in an individual action after entry of a consent decree in a class action

in which he was a non-named class member. The Fifth Circuit held

the plaintiff bound by the class action decree. There the issues in the

class action involved a “system” of “limiting the employment and

promotional opportunity” of class members. 608 F.2d at 1052. The

Fifth Circuit noted that since the plaintiff’s claims arose prior to

entry of the judgment in the class action and “were or could have

been brought” before the court in the class action, the same cause of

action was involved and the plaintiff was bound by the prior class

action decree. 608 F.2d at 1053.

A companion case, Fowler v. Birmingham News C o ., 608 F.2d

1055 (5th Cir. 1979), confirms Kemp , but also adds an additional

feature. Like Petitioners, Fowler complained that he had been

denied promotions and passed over for supervisory positions. Also

similar to this case, Fowler was not entitled by the class action

decree to all of the relief that other class members had obtained.

Nevertheless, his personal claims were barred by the prior class

action decree because they were within the scope of the general

issues resolved in the class action.

The Ninth Circuit has also followed Kemp in affirming the dis

missal of a plaintiffs claims arising from incidents that occurred

prior to settlement of a class action in which the plaintiff has been

a class member. Dosier v. Miami Valley Broadcasting C o r p 656

F.2d 1295 (9th Cir. 1981). There, the plaintiffs personal claims of

denial of promotions were barred by the decree in the prior class

action which settled the issue of classwide denial of “employment

opportunities.” But, other claims of retaliation that were not part of

the classwide allegations in the prior class action were not dis

missed. 656 F.2d at 1298-99.

The Fourth Circuit has also recognized this principle in two deci

sions preceding this case: Woodson v. Fulton, 614 F.2d 940 (4th

Cir. 1980) (class action consent decree involving issues of discrim

ination in hiring, discipline and promotion barred class member’s

subsequent individual action on issues of his personal discrimination

discipline and hindrance of advancement, but not his claim relating

9

to discharge not included in the class action); Dalton v. Employment

Security Comm’n, 671 F.2d 835 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 1A L. Ed.

2d 117 (1982), (consent decree barred subsequent individual action

on issues subject to the decree).3 4

Dicta in Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp., 582 F.2d 827

(3d Cir. 1978), states that class members in an unsuccessful class

action may re-litigate their personal claims in a subsequent individ

ual action. That decision is directly contrary to Woodson, Dalton,

Kemp, Fowler and Dosier,4 and by implication has been tacitly

rejected by those decisions which occurred subsequent to its publica

tion. Moreover, as the Fourth Circuit noted here, the dicta in Dick

erson was subsequently rejected by the Third Circuit en banc in

Croker v. Boeing C o ., 662 F.2d 975, 997 (3d Cir. 1981). There the

3 The EEOC contends that this line of decisions merely “effectuatefs] the

salutary policy against double recovery.” [EEOC Br. at 12 n.14]. In fact,

Kemp, Fowler, Dosier, Woodson and Dalton make no mention of the

prospect of “double recovery.” Rather, each decision held that the doctrine

of res judicata barred class members’ subsequent claims and that the class

action involved the same cause of action raised by a class member in a

subsequent suit. See, e.g., Woodson, 614 F.2d at 941-42; Kemp, 608F.2d

at 1052-53; Dosier, 656 F.2d at 1298-99.

4 Petitioners cite several cases as also being contrary to the cases dis

cussed above. Each case involves a defect not present here and is dis

tinguishable from the cases discussed above: In Bogard v. Cook, 586 F.2d

399, 408 (5th Cir. 1978), a subsequent individual action was permitted

because it alleged acts directed at the plaintiff after the record in the class

action had been closed and it sought damages for specific acts of physical

abuse which were not included in the prior class action and which sought

only equitable relief from general prison conditions. In Marshall v. Kirk

land, 602 F.2d 1282, 1298 (8th Cir. 1979), a subsequent action was

permitted because there had been no notice to class members regarding the

class action. Finally, in Eastland v. T.V.A., 704 F.2d 613, modified in

part, 714 F.2d 1066 (11th Cir. 1983), involved only consolidation for trial

with the class action of the individual claim of a purported class representa

tive who had been found not to be an adequate class representative.

10

court dismissed as barred by res judicata two individual claims

“because they were not named plaintiffs but rather were class-

member witnesses whose class-wide claims had been unsuccessful”

in the earlier class action (just as Petitioners here).5

The EEOC and Petitioners contend that a “pattern and practice”

claim of discrimination is a different cause of action than an individ

ual suit under Title VII or 42 U.S.C. § 1981. In fact these are no

more than two methods of proving the same fact: whether a particu

lar employment decision was racially premised. Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 335 (1977). In Teamsters this Court rejected

the assertion that a Title VII plaintiff could carry the burden of proof

only by presenting evidence according to the standards of

McDonnell-Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), and stated that

“‘[t]he facts necessarily will vary in Title VII cases, and the specifi

cations ... of the prima facie proof required from [a plaintiff] is not

necessarily applicable in every respect to differing factual situ

ations.’” Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 358, citing McDonnell-Douglas,

411 U.S. at 802 n.13. Accordingly, the bifurcated trial of “pattern

and practice” discrimination merely “illustrates another means by

which a Title VII plaintiffs initial burden of proof can be met.”

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 359 (Emphasis added). Simply because a

“pattern and practice” method of proof differs from the elements of

a McDonnell-Douglas method of proof does not create two causes

of action. The injury alleged is the same, the statutes under which

the cause of action arises are identical, and the ultimate issue adju

dicated by the court does not differ, regardless of the method of

proof.

In fact, a “pattern and practice” class action is by its nature an

aggregation of the “individual claims” of each of the class members.

Deposit Guaranty National Bank v. Roper, 445 U.S. 326, 339

(1980). In a private class action there is nothing involved but

5 In Edwards v. Boeing-VertolCo., 717 F.2d 761 (3dCir. 1983), a panel

of the Third Circuit permitted a subsequent action by an unsuccessful class

member under principles of tolling. A Petition for Certiorari is presently

pending in this Court in that case.

11

individual claims. A class action is not a separate cause of action

itself. Without the individual claims there would be nothing to

litigate in the class action. This is particularly true in a disparate

treatment action which alleges a “pattern and practice” of discrimi

nation, such as this case. Such an action attempts to show that

discrimination is “the regular rather than the unusual practice.”

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. at 336. So, the “pattern and

practice” attempted to be demonstrated consists of an aggregation of

separate, distinct promotion decisions involving numerous

individuals — not an additional substantive cause of action.

The incongruity of the Petitioners’ position is easily demon

strated. Under Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981, an individual plain

tiff can carry his burden of proof of discrimination either by demon

strating that the employer engaged in a “pattern and practice” of

discrimination or by introducing evidence in accordance with the

pattern of McDonnell-Douglas and its progeny. Teamsters, 431

U.S. at 359. A Title VII plaintiff who filed an individual action

alleging a pattern and practice of discrimination, of which he was a

victim, would surely be bound by an adverse determination in his

individual suit. He would not be able to file a second lawsuit that

alleged again that he had been discriminated against, but that this

time his evidence would be presented in accordance with the pattern

of McDonnell-Douglas. An individual possesses only one cause of

action under Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981, but he has two

different ways of proving his cause of action. Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. at 359; see also, Coe v. Yellow Freight Systems,

Inc ., 646 F.2d 444, 449 n. 1 (10th Cir. 1981). He may decide to

pursue one method of proof rather than the other, but he cannot

splinter his cause of action into different lawsuits and continue to

attempt to prove the same injury under different theories in different

lawsuits.

This conclusion does not change simply because a Title VII plain

tiff has pursued a pattern and practice claim as a class member of a

class action suit. The mere fact that he was a member of a class

action which litigated a “pattern and practice” action does not splin

ter his cause of action into two causes of action, one for a “pattern

and practice” and one for individual acts of discrimination pursuant

to the pattern of McDonnell-Douglas.

12

Thus, an individual’s cause of action for racial discrimination is

procedurally indistinguishable for res judicata purposes from a

class wide cause of action for discrimination. Both the individual and

class claims vindicate the same right and focus on the same issue:

whether the employer has discriminated against an employee on the

basis of race.6

Here, there can be little doubt that these Petitioners’ promotion

claims were encompassed within the allegations of classwide dis

crimination in promotions in the class action. Their claims stated in

their Complaint in the Baxter action [J.A. 63a] relate to the denial

of various promotions to each Petitioner. Denial of promotions was

the primary issue litigated and decided in the class action. Virtually

all of the trial in EEOC and Cooper was directed to the promotion

issue. Plaintiffs offered over fifty statistical exhibits directed to the

promotion issue. [PX 34-37, 34a-37a, 114a-114tt]. Moreover, Peti

tioners each testified at the trial in support of the class action, and

their testimony concerned the denial of the very promotions they

now allege in the Baxter Complaint.7 This class action clearly liti

gated and decided the issue of discrimination in promotions. Con

sequently, the subsequent Baxter action involves the “same cause of

action” decided in the EEOC and Cooper class action. So, re

litigation of the “individual claims” is barred by res judicata.

6 Although the issue presented here happens to arise in a discrimination

suit, it is not peculiar to that type of action. The issue here is of general

procedural applicability. It would be present in antitrust, securities, and

consumer class actions— in fact, it would be present in any class action.

7 Petitioners’ reliance on the district court’s Findings relating to their

testimony [Pet. Br. 39] is misplaced. Those “findings” were prepared by

plaintiffs’ counsel and adopted by the district court apparently without

critical review. [P.A. 13a-24a], Therefore, they suffer the same flaw as

other such Findings criticized by the Fourth Circuit and found to be clearly

erroneous. In fact, their “findings” are merely a summary of Petitioners’

assertions and they completely ignore the ample rebuttal evidence offered

by the Bank.

13

b. The Decision o f the District Court

Petitioners contend that the judgment of the district court did not

include their claims. They focus on the district court’s informal

“Memorandum of Decision,” but ignore the other parts of the

Record which define the scope of the class action — the class certi

fication Consent Order, the Notice and the Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law finally entered by the district court and incorpo

rated into the Judgment.

The Consent Order certifying the EEOC and Cooper class dem

onstrates that both classwide as well as individual issues of discrim

ination were being adjudicated. There, the district court explicitly

found that: “there are common questions of law and fact involved”;

“the claims and defenses... are typical of the claims and defenses of

the class...”; “the plaintiff-intervenors will adequately protect the

interest of the class they seek to r e p r e s e n t . a n d “questions of law

or fact common to the members of the class predominate over any

questions affecting only individual members....” [J.A. 28a-29a].

Such findings would have been unnecessary if “individual claims” of

discrimination were not in issue.

Similarly, the district court defined the class to include all black

employees employed by the Bank “who have been discriminated

against because of their race in promotions, training, wages, disci

pline and discharge.” [J.A. 53a Hi (Emphasis added)]. The Notice

mailed to class members informed Petitioners of their right “to

pursue in this action any claim of racial discrimination in employ

ment that you may have against the defendant.” [J.A. 35a-37a

(Emphasis added)]. Neither the class certification Consent Order,

the Notice to class members, nor the final definition of the class

limited the cause of action in the EEOC and Cooper action to a

“pattern and practice” claim. On the contrary, the district court

defined both the class and the class issues in broad, across-the-board

terms.

The Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law also demonstrate

that the claims of Petitioners and their class were actually decided in

the class action. Petitioners continually point out that the district

court’s “Memorandum of Decision” stated merely that the court did

14

not find a pattern of discrimination in Grades 6 and above “pervasive

enough” to order relief. [Pet. Br. 16; EEOC Br. 15]. But, Petitioners

completely ignore the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

subsequently entered by the district court which, contrary to their

counsel’s proposal, clearly decided “that defendant did not violate

Title VII or 42 U.S.C. §1981 with respect to promotions out of

Grade 6 and above.” [P.A. 285a (Emphasis added)].

The significance of that conclusion is highlighted by the fact that

Petitioners’ counsel sought a quite different conclusion. The Memo

randum of Decision directed Petitioners’ counsel to prepare pro

posed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. Petitioners’ counsel

proposed on this point that the district court decertify the class as to

employees in Grades 6 and above and proposed the following

conclusion:

27. Plaintiffs called several individual witnesses at the

trial, some within the class as originally defined and some

within the class as modified. The court expresses no

position at this stage as to the entitlement to relief of the

witnesses outside the modified class [the present Petition

ers]....8

[Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (Emphasis

added)]. Contrary to the suggestion that “no position” be expressed

as to the entitlement to relief of these very Petitioners (who were “the

witnesses outside the modified class”), the district court entered a

decision that the Bank had not discriminated against those class

8 The proposed Findings were included in the Record in the Fourth

Circuit, but not in the Joint Appendices there or in this Court. The proposal

for certification of a class that included only Grade 4 and 5 employees and

the proposed expression of no position on the claims of Petitioners appear

at pages 28 and 39 of the Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law.

15

members. The district court’s conclusion adopted in lieu of Petition

ers’ counsel’s proposal was that:

27. The Court concludes that there was no showing

that the bank had discriminated against black employees

with respect to promotions out of Grades 6 and above, and

that defendant did not violate Title VII or 42 U.S.C.

§1981 with respect to promotions out o f Grade 6 and

above.

[P.A. 285a (Emphasis added)]. This decision by the district court is

made even more important by the fact that it is the only significant

change to the proposed Findings that the district court made — all

other changes were merely grammatical.9

As Petitioners suggest, it is important to focus on the “actual

language of the judgment” [Pet. Br. 24] to ascertain the scope of the

decision. Here, the district court’s decision was not limited to

“pattern” or “class” issues. Rather, the “actual language of the

judgment” stated the affirmative conclusion that the Bank “did not

violate Title VII or 42 U.S.C. § 1981 with respect to promotions out

of Grade 6 and above.” [P.A. 285a].10 Furthermore, Petitioners did

not appeal this conclusion.

9 A “marked” copy of the Findings which shows all changes from the

proposed to the finally adopted Findings was submitted to the Fourth

Circuit following ora! argument below, and was included in the Record

there. The Court of Appeals was highly critical of the district court ’s virtual

verbatim adoption of Petitioners’ counsel’s proposed Findings. [See P.A.

13a-24a.] Petitioners sought certiorari on that issue, but it was not granted.

10 The formal “Judgment” filed contemporaneously with the Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law makes no specific mention of Grades 6 and

above (other than by implication), but the Judgment does specifically state

that it is based on those Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. The

Judgment makes no mention of the Memorandum of Decision.

16

In summary, the Consent Order certifying the class action

included Petitioners’ claims in the class action. In the Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law, the district court rejected the proposal

to “express no position” on Petitioners’ claims and instead con

cluded affirmatively that the Bank did not discriminate in pro

motions out of Petitioners’ job Grades. So, the “actual language” of

the district court expressly demonstrates an adverse decision on the

merits of Petitioners’ claims. The doctrine of res judicata now bars

Petitioners from re-litigating those claims.

2. Rule 23 Bars Petitioners’ Claims

By participating as class members in the EEOC and Cooper class

action, Petitioners elected to litigate their claims of discrimination

against the Bank through the Cooper class representatives. Rule 23

requires that Petitioners be bound by the judgment entered in that

action. Indeed, Petitioners’ attempt to file individual claims only

after the district court indicated it would rule against Petitioners in

the class suit is precisely the type of “one-way intervention” which

Rule 23 does not permit. Plus, the practical effect of Petitioners’

assertion would be to render Rule 23 and the class action meaningless.

a. The Language and Intent o f Rule 23

The very language of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 precludes subsequent

actions by class members following their participation in an unsuc

cessful class action. Rule 23 (c) (3) provides that:

The judgment in an action maintained as a class action

under subdivision (b)(1) or (b) (2), whether or not favor

able to the class, shall include and describe those whom

the court finds to be members of the class. The judgment

in an action maintained as a class action under sub

division (b) (3), whether or not favorable to the class,

shall include and specify or describe those to whom the

notice provided in subdivision (c)(2) was directed, and

who have not requested exclusion, and whom the court

finds to be members of the class.

17

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (c) (3) (Emphasis added). Thus, Rule 23 requires

that class members be bound by an adverse judgment.

Rule 23 is designed to avoid a “needless multiplicity of suits” and

to permit the adjudication of numerous claims in one proceeding.

American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538, 553

(1974); Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 76 L. Ed. 2d 628, 634

(1983). To avoid the impracticalities of joining numerous parties, a

class action is litigated through class representatives and their coun

sel. In EEOC and Cooper Petitioners elected not to pursue their

claims individually, but instead chose to rely on the class represen

tatives.11 Rule 23 is designed to adjudicate the claims of class

members in the one action. General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457

U.S. 147, 155 (1982). It does not permit class members to sit on the

fence awaiting judgment in the class action and then to pursue a

subsequent “individual” action if the result is not to their liking — as

Petitioners seek to do here.

Rule 23 was amended in 1966 to prevent the very procedure which

Petitioners seek here. Prior to 1966, Rule 23 provided no means for

establishing, prior to the entry of a final judgment, which persons

were class members and would be bound by the judgment. American

Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. at 545-46. Under the

present version of Rule 23, however, a class member may not await

the outcome of the trial in the class action, and then decide whether

to pursue the same course of action in another proceeding. In Amer

ican Pipe, 414 U.S. at 547-49, this Court noted that the 1966

amendments to Rule 23 were specifically intended to cure the former

procedures permitting class members to await developments in the

trial “or even final judgment” before deciding whether to opt out as

class members. This Court stated that, as presently written, Rule 23

requires that:

potential class members retain the option to participate in

or withdraw from the class action only until a point in the

litigation ‘as soon as practicable after the commence

ment’ of the action.... Thereafter they are either non

11 Petitioners have not asserted that their representation in the class action

was inadequate.

18

parties to the suit and ineligible to participate in a recov

ery or to be bound by the judgment, or else they are full

members who must abide by the final judgment, whether

favorable or adverse.

414 U.S. at 548-49.

After electing to litigate their claims in the class action, Petition

ers now seek to avoid the judgment in that action and gain a second

chance to re-litigate those claims. That is precisely what Rule 23 was

amended to prevent.

b. Petitioners’ Election

Petitioners correctly state several principles: The fact that an

employer’s workforce is racially balanced does not immunize an

employer from liability for specific acts of discrimination, Furnco

Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567 (1978); an employer’s

“bottom line” in promotions is not an affirmative defense to a claim

of particular acts of discrimination, Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S.

440 (1982); conversely, the existence of an individual act of discrim

ination does not require an inference that such treatment is typical of

an employer’s practices, General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457

U.S. at 157-58; and the fact that there is no showing of a “pattern

and practice” of discrimination does not require the conclusion that

there may not have been isolated or sporadic individual acts of

discrimination, Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. at 336. [Pet.

Br. 43-45 j. All of those principles are true, but they are principles

of proof, not of substantive procedure. While individual acts of

discrimination may exist even in the absence of a “pattern and

practice” of discrimination, that does not determine the vehicle for

litigating ones’ claims. Here, these Petitioners elected not to pursue

their claims individually, but to join in the class action. They were

not denied their right to pursue their claims individually. In fact the

Notice advised them of that right. But, they elected not to pursue

their claims in that manner, but to pursue them as class members in

the class action.

Petitioners accuse the Bank of “thwarting” their efforts to pursue

their individual claims. [Pet. Br. 12]. In fact, it was Petitioners

themselves who “thwarted” their right to an individual suit by elec

19

ting not to exercise that right. The class action Complaint was filed

by four intervenors in 1977. Upon Petitioners’ consent, the EEOC

and Cooper action was conditionally certified as a class action in

April 1978 pursuant to both Rule 23(b)(2) and (b)(3). [J.A. 30a],

When the district court conditionally certified the class, it required

that a Notice be sent to each class member. Each of these Petitioners

actually received the Notice. [J.A. 95a], The Notice informed Peti

tioners that they would “be bound by the determination in this

action” unless they excluded themselves from the class, and that if

they opted out of the class they would not be bound by the decision

in the class action.12 Petitioners did not opt out of the class action;

nor did they seek to intervene in it as named parties (prior to the

12 The Notice stated in pertinent part:

3. The class of persons who are entitled to participate in this action

as members of the class represented by the plaintiff-intervenors, for

whom relief may be sought in this action by the plaintiff-intervenors and

who will be bound by the determination in this action is defined to

include: all black persons who were employed by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Richmond at its Charlotte Branch Office at any time since

January 4, 1974.

4. ... if you so desire, you may exclude yourself from the class by

notifying the Clerk, United States District Court, as provided in para

graph 6 below.

5. If you decide to remain in this action, you should be advised that:

the court will include you in the class in this action unless you request

to be excluded from the class in writing; the judgment in this case,

whether favorable or unfavorable to the plaintiff and the plaintiff-

intervenors, will include all members of the class; all class members

will be bound by the judgment or other determination of this action__

6. If you desire to exclude yourself from this action, you will not be

bound by any judgment or other determination in this action and you

will not be able to depend on this action to toll any statutes of limitations

on any individual claims that you may have against the defendant ....

[J.A. 35a-37a (Emphasis added)]. Petitioners raise a question about the

adequacy of this Notice. However, the Notice tracks the language of Rule

23 itself. Moreover, Petitioners’ counsel consented to the Notice in the

Consent Order. [J.A. 24a].

20

adverse ruling as to their class). Instead, they elected to pursue their

claims as class members and actually testified in support of the class

action.

Binding Petitioners to the adverse judgment in the class action is

particularly appropriate in this case because:

— Petitioners had never filed charges of discrimination

with the EEOC:

— they were given notice of the opportunity to pursue

their claims as individuals when the class was certified

two years prior to trial;

— they never moved to intervene in the class action even

though their counsel had intervened on behalf of four

other individuals and the Bank had not opposed that

intervention;

— their counsel consented to a bifurcated trial of the class

action;

— they first “appeared” in the class action on a witness

list filed four days prior to the trial, but did not attempt

to intervene even then;

— they appeared and testified at the trial of the class

action, but made no attempt to intervene — even after

the district court stated that it would not make a deter

mination of their personal claims; and

— they made no attempt to assert their personal claims

until four months after they learned that their class had

lost the class action.

As class members in the previous class action, these Petitioners

received notice of the proceedings and were given the option of

pursuing their claims via the class action or opting out of that action

and pursuing them individually. The Notice spelled out the fact that

they would be bound by the judgment in that action “whether favor

able or unfavorable” unless they opted out of the class action. With

that knowledge, Petitioners elected to pursue their claims as class

members in the class action. The class action judgment was adverse

to their class. Accordingly, Rule 23 requires that Petitioners be

bound by their election.

21

c. The Practical Effect o f Petitioners’ Assertion

The practical effect of Petitioners’ submission would destroy the

class action as a vehicle for litigating multiple claims and would

effectively erase Rule 23 from the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Petitioners’ submission is simple: after an adverse decision in a

class action — that the Bank did not discriminate in promotions in

Grade 6 and above — Petitioners can nevertheless pursue their

“individual claims” that they had been discriminated against in pro

motions in Grade 6 and above. If these Petitioners can pursue such

an action, so can each and every one of the 300 or so other class

members.13 And, after prevailing on the merits of the class action,

the Bank may face “individual” suits by each and every class

member.

If Petitioners’ assertion is the rule, then the practical result is that

no purpose is served by Rule 23 and the class action. Although

Petitioners assert that they do not seek “one-way intervention,” that

is precisely the result of their submission. Petitioners’ rule would

permit them to participate as non-named class members in the class

action (as they did) and: (i) if they won the class action, obtain a

presumption of discrimination14 in their favor; and (b) if they lost

the class action, still maintain their “individual claims” for relief.

What Petitioners suggest is a “no lose” situation that any litigant

would envy. It makes the class action a no-risk situation for plaintiffs

l3The tolling effect of the class action, American Pipe, 414 U.S. 538

(1974), if added to the three-year limitations period for § 1981 actions,

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1-52, may render the potential claims of each class

member still vital, even though the claims are possibly 10 years old. Of

course, if, as Petitioners assert, the “individual claims” were not part of the

class action, then the class action should not toll the running of statutes of

limitations and those claims may be barred on that account.

14 In the trial of a bifurcated class action, Stage I of the trial determines

liability. If a pattern and practice of discrimination is demonstrated in Stage

I, each class member receives a rebuttable presumption that he is a victim

of that discrimination and is presumed to be entitled to relief in Stage II of

the proceeding. See Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 359-362

(1977).

22

and a no-win situation for the defendant— since even if the de

fendant prevails on the merits in the class action, the class can roll

on “individually.”

Petitioners suggest that the Fourth Circuit’s decision will force all

class members to intervene in the class action.15 Multiple inter

vention is a false fear because there are many good reasons for class

members to elect to litigate their “individual claims” as class

members— as Petitioners did. First, a class member’s chances of

winning relief are probably greater in a class action than in an

individual suit. The pattern and practice class action has proved to

be an effective and successful device for plaintiffs in employment

discrimination cases. Methods of proof— such as the “pattern and

practice” proof scheme and statistical proof— may be available in a

class action that would not be probative in an individual action. The

cumulative effect of multiple claims may have greater impact than

an individual claim. And, once successful in Stage I of the class

action, each class member receives a valuable presumption of enti

tlement to relief that may convert a losing claim into a winning one.

Second, there are real economic advantages to litigating one’s

“individual claim” as a class member. This Court has noted that “a

central concept of Rule 23” is that a class member has access to the

pooled resources of the entire class, and the costs of litigation are

shared among the entire class. Deposit Guaranty National Bank v.

Roper, 445 U.S. at 338 n.9. In this very case, for example,

Petitioners— as class members — were represented by three lawyers

and as many paralegals and had the benefit of an expert statistician

who performed analyses and testified at the trial (for $50,000.00).16

An individual employee certainly could not muster that kind of

support for his “individual claims” in an individual action. Thus,

there are real, practical benefits for class members who elect to

litigate their claims as a class member in a class action.

15 Of course, if class members are permitted to pursue “individual

claims” after an unsuccessful class action as Petitioners suggest, then it

would behoove the defendant to move the court to join all the class mem

bers as named parties in order to obtain a binding judgment against them.

16 See, Motion for Attorneys Fees and supporting Affidavits filed in the

Record of the district court in EEOC and Cooper.

23

Petitioners’ proposition is also inherently inconsistent. It would

permit each and every one of the 300 passive members of the EEOC

and Cooper class to file individual suits against the Bank despite the

district court’s conclusion that the Bank did not discriminate as to

promotions in Grade 6 and above. This is simply “massive

intervention” of a different type. Surely the prospect of 300 individ

ual suits against the Bank, filed at various times and perhaps in

various forums, is much worse than requiring that all class members’

claims be managed and adjudicated by the district court in one

proceeding.

Petitioners’ suggestion that, under their rule, a defendant would

benefit by class members not being able to assert a “pattern and

practice” of discrimination as evidence in subsequent “individual”

actions is similarly unsound. The purpose of Rule 23 and the class

action device is not to establish a rule of evidence. The Bank certain

ly cannot be expected to defend this action for over six years — at

great expense — just to eliminate one piece of evidence from multi

ple subsequent individual actions. In fact, this assertion demon

strates the illogic of Petitioners’ position. Their position— by their

own submission— would reduce a class action into nothing more

than an evidentiary ruling. Such a result is certainly not contem

plated by Rule 23 and is wholly illogical.

The purpose of Rule 23 and the class action is to avoid needless

multiplicity of suits and to adjudicate numerous claims in one suit.

If this purpose is to be effected, the judgment in the class action must

be binding on class members.

d. Other Decisions o f this Court Involving Rule 23

The decision of the Fourth Circuit barring Petitioners’ subsequent

action is consistent with other decisions of this Court involving class

actions. It fits well within the framework of this Court’s other

decisions involving Rule 23. In fact, the result here has been sug

gested in other decisions of this Court.

In American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538

(1974), the Court held that the pendency of the class action tolled the

running of statutes of limitations on class members’ right to inter

vene in the action as individuals after denial of class certification.

24

414 U.S. at 553. That principle was recently applied to class mem

bers’ rights to file separate actions. Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v.

Parker, 76 L. Ed. 2d 628 (1983). However, both of those cases

dealt only with the tolling of limitations periods pending class certi

fication . In both of those cases class certification was denied. Puta

tive class members were freed to file individual actions because

there was no judgment in the class action. In contrast, in this case

the class was certified and there was a judgment on the merits in the

class action. So, the fact that the limitations periods for individual

actions by class members may have been tolled during the pendency

of the putative class action is consistent with extinguishing the right

to an individual action by the adverse class action judgment on the

merits. In fact, American Pipe actually noted that Rule 23 had been

amended to prevent the “one-way intervention” Petitioners seek to

accomplish here. 414 U.S. at 547-49.

In General Telephone Company v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318 (1980),

this Court held that the EEOC could seek relief for a group of

aggrieved individuals without certification as a class representative

pursuant to Rule 23. The Court noted that one effect of the ruling

was that the individuals would not be bound by the relief obtained

by an EEOC judgment or settlement. 446 U.S. at 333. But, in the

course of discussing that result, the Court suggested that the result

would be different in a private class action certified pursuant to Rule

23. This Court noted that: “We are sensitive to the importance of the

res judicata aspects of Rule 23 judgments. . . ” 446 U.S. at 332.

The Fourth Circuit’s decision that Petitioners are bound by the

adverse judgment in the prior, private class action is consistent with

the language and intent of Rule 23 and with the decisions of this

Court. Further, it follows the result suggested in General

Telephone.

II. The Bank Did Not Acquiesce In Subsequent

Individual Actions And The District Court

Did Not Authorize Subsequent Actions

Petitioners’ assertion that the Bank acquiesced in or acknowl

edged Petitioners’ right to pursue individual claims in subsequent

suits is misleading. In the course of opposing intervention in the

class action after the trial, the Bank’s counsel, relying on certain

25

portions of dicta in Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp., 582

F.2d 827 (3d Cir. 1978), did state Petitioners might file a subsequent

action.17 But, the Record is clear that the Bank’s position throughout

was that Petitioners’ individual claims were barred by res judicata.

For example, at the hearing on Petitioners’ Motion to Intervene,

the Bank’s counsel stated its position in the following manner:

MR. HODGES: The problem, Your Honor, is that

these people chose to participate in this case as class

members, and in a class action the judgment of the Court

is that their part of the class should receive no relief, so

they are not entitled to proceed any further. They have a

judgment entered against them on the part of the class.

[p. 4],

^ j}c jfc

MR. HODGES: That’s right, and they could go file

charges with the EEOC, file a case under 1981, but they

could not participate any longer in this case. They are not

entitled simply to go into Stage 2 to pursue their claims.

They’ve got to do what any other Plaintiff with a com

plaint has got to do and that is to go through the proper

procedure. They are people that actually showed up in

this case about a week before trial and just happened to

come in and testify, and I don’t believe that gives them

any additional status than any of the other class members

in Grades 6 and above would have. They are bound by the

judgment against them. [p. 8].

COURT: You’re unnecessarily complicating the possi

bility of getting an ultimate decision on the merits by

skipping what would ordinarily be normal procedure.

17 Petitioners’ selective quotation of statements made at the hearing on

their Motion to Intervene appears to imply that counsel misled the district

court about the Bank’s position. Actually, if the district court was led into

an erroneous conclusion about Petitioners’ right to file a subsequent action,

it was by the statements in dicta in Dickerson and not any statements by

counsel.

26

MR, HODGES: Your Honor, that doesn’t avoid the

problem that you’ve got that they should have a judgment

entered against them as they are part of a class, [p. 10],

* * * * *

MR. HODGES: The Third Circuit decided otherwise.

They said the intervention of class members would preju

dice the Defendant severely. From the outset this lawsuit

was tried as a class action, based primarily upon the

allegations of across the board discrimination. That’s

exactly the case here. There’s no reason to give these

Plaintiffs a second bite out of the apple in this case. Stage

2 proceedings are for the successful class members, not

the unsuccessful. Otherwise why have a Stage 1 pro

ceeding. [p. 17],

* * * * *

MR. CHAMBERS: As to the class. I f the Court fo l

lows that reasoning, it would say that the individuals now

are barred by res judicata.

MR. HODGES: That’s exactly what they [sic] ought to

do. [p. 19-20],

[Citations are to the transcript of the hearing on Petitioners’ Motion

to Intervene, May 8, 1981, which has been filed in this Court with

the Joint Appendix (Emphasis added)]. The Bank clearly did not

acquiesce in or agree to Petitioners’ subsequent action. Rather, the

Bank’s position was that it was entitled to a judgment against Peti

tioners and any subsequent actions would be barred by res judicata.

Consequently, when the subsequent action was filed, the Bank

moved that it be dismissed on that basis.

Petitioners’ assertion that the district court authorized the sub

sequent action misapplies principles relating to splitting claims and

misconstrues what the district court actually did. Restatement (Sec

ond) of Judgments § 20 (l)(b), by its terms, applies only where the

plaintiff is “nonsuited” or his claims “dismissed” without prejudice.

Here, there was a judgment on the merits. Plus, all that was

“dismissed” was their Motion to Intervene — not a prior action as

27

contemplated by the Restatement. The assertion that the district

court “expressly reserved” Petitioners’ right to maintain a second

action misapplies Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 26. That

applies only where causes of action are “split” and the claims

“reserved” are omitted from the first action. It does not permit

“reservation” of claims included in the first action such as is the case

here — especially after a decision on the merits has been announced.

See Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 26 comment b. More

over, the district court here did not “expressly reserve” any rights.

In the Order denying intervention the district court merely expressed

an opinion that the Petitioners might be able to pursue a separate

action:

I see no reason why, if any of the would be intervenors

are actively interested in pursuing their claims, they can

not file a Section 1981 suit next week, nor why they could

not file a claim with EEOC next week . . . All motions for

leave to intervene are thus denied without prejudice to

any underlying rights the intervenors may have.

[P.A. 288a-289a (Emphasis added)]. The Restatement exception

applies to express reservations of rights, not to advisory comments

about possible rights as the statement above. Consequently, there

was no reservation of rights by the district court nor acquiescence by

the Bank as to Petitioners’ subsequent action.

28

II. The Claims of Petitioner Harrison

Both courts below stated Petitioner Harrison to be a Grade 3

employee. But, in fact, Harrison was at all times a Grade 6 employ

ee. The Bank has furnished counsel for Petitioners portions of Har

rison’s employment records, all of which confirm that he was a

Grade 6 employee.18 Accordingly, counsel for Petitioners has ad

vised the Bank that they have withdrawn their assertions based upon

the erroneous statements of the courts below that Harrison was a

Grade 3 employee. [Pet. Br. 53-56], Thus, the parties now agree that

Harrison’s position is the same as the other Petitioners, and the Bank

makes no substantive response to the assertions regarding Harrison.

18 Harrison’s job Grade was not a significant issue at this trial, so there

is little in the actual Record regarding his Grade. Harrison testified first that

he was a Grade 3 but when asked if he was not actually a Grade 6, he said

he did not know. [I C.A. App. 537, 540]. The Record also contains a

group of job descriptions [DX 70] which shows that Harrison’s job of

“stock clerk” (he called it “supply clerk” [I C.A. App. 537]) was a Grade

6 job. [DX 70 page 5-291].

29

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the Bank submits that the rule this

Court should adopt is that: a properly certified class action is made

up of the “individual claims” of class members, and those class

members who, after notice, elect to litigate their claims in the class

action are thereafter precluded from re-litigating individual claims

within the range of issues determined in the class action. Con

sequently, the decision of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted this 26th day of January, 1984.

George R. Hodges*

Hayden J. Silver, III

Vice President and

General Counsel

Wm . Dabney Martin, III

Moore, Van Allen and Allen

3000 NCNB Plaza

Charlotte, North Carolina 28280

Federal Reserve Bank

of Richmond

Telephone: (704) 374-1300

Counsel for Respondent

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

*Counsel o f Record

30

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that he has this day served other

parties in this action by causing three copies each of the foregoing

Brief for Respondent Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond to be

deposited in the United States Mails, postage prepaid and properly

addressed to:

J. LeVonne Chambers, Esq.

John T. Nockleby, Esq.

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas, Adkins & Fuller

Suite 730 E. Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Eric Schnapper, Esq.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Rex Lee, Solicitor General

% Harriet Shapiro, Esq.

Office of the Solicitor General

Washington, D.C. 20530

This 26th day of January, 1984.

/ s / George R, Hodges

George R. Hodges