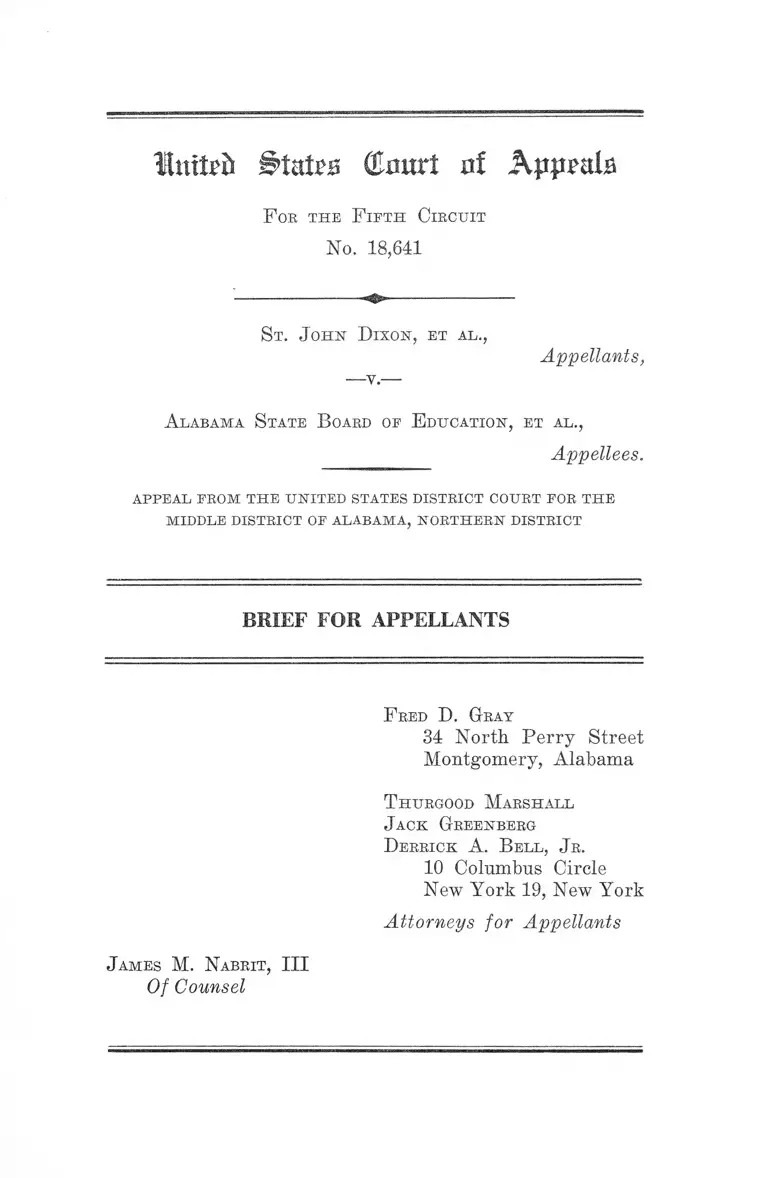

Dixon v. Alabama Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dixon v. Alabama Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1960. 4a9507f5-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3105d951-4dba-45cf-af3f-24dba6a0de6c/dixon-v-alabama-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

Butts GJmtrt nf Kppmls

F oe t h e F if t h C ie cu it

No. 18,641

S t . J o h n D ix o n , et a l .,

Appellants,

----y.----

A labam a S tate B oard of E d u catio n , et a l .,

Appellees.

appeal feom t h e u n ited states district court for th e

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DISTRICT

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

F red D . G ray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

D errick A. B ell , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

J am es M. N abrit , III

Of Counsel

Inttefc B u t t s (Esurt of K p p m l s

F oe t h e F if t h C ircu it

No. 18,641

St . J o h n D ix o n , et a l .,

Appellants,

A labam a S tate B oard of E d u catio n , et a l .,

Appellees.

appeal from th e u nited states district court for th e

M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF A L A B A M A , N O R T H E R N D ISTR IC T

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This action by six former Negro students at a state-

operated college seeks to enjoin defendant state school

officials from further enforcing an order of expulsion

against them, entered without the customary notice and

hearing, as a disciplinary measure in retaliation for their

protest against racial segregation at a lunch counter in

the Montgomery, Alabama courthouse, and for their al

leged participation in meetings where objection was voiced

against racial discrimination generally.

The action was commenced on July 13, 1960, in the

United States District Court for the Middle District of

Alabama, Northern Division. Jurisdiction was invoked

pursuant to 28 IT. S. C. §§1331, 1343 and 42 U. S. C. §§1981,

1983, alleging deprivation of rights protected by Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2

The complaint stated that plaintiffs were students in

good standing at Alabama State College, and that defen

dants, Alabama State Board of Education, its members,

Alabama State College and its President, H. Councill Tren-

holm, punished plaintiffs by expulsion without warning or

opportunity to be heard for having sought service at the

lunch counter in the Montgomery, Alabama County Court

house. The answer consisted principally of denials ad

mitting only plaintiffs’ United States citizenship, that they

had been students at Alabama State College and the official

status of defendants. The answer relied chiefly upon ap

pended affidavit of the Governor of Alabama.

Hearing on plaintiffs’ motions for preliminary and per

manent injunctions and defendants’ motions to strike and

dismiss was held August 22, 1960; both sides presented

testimony and exhibits. These salient facts emerged:

Plaintiffs were expelled for conduct prejudicial to the

college, but the Board itself possessed no standards against

which it could be determined whether conduct was preju

dicial and warranted dismissal (R. 144, 146). Nevertheless,

central to the dismissal was plaintiffs’ request for service

at the lunch counter in the Montgomery County Court

House. Only those who requested such service were dis

missed, while hundreds participated in other protests

against racial segregation (R. 148).

Immediately following plaintiffs’ request for service at

the lunch counter of the Montgomery County Court House,

the Governor, who is a defendant here, and Chairman of

the State Board of Education, ordered plaintiffs’ dismissal:

Q. . . . will you tell the Court whether or not the

same afternoon that these plaintiffs and others re

quested service at the Court House on February 25

did the Governor of this State tell you to make an

3

inquiry and to dismiss any student at the College who

were involved in the lunch room incident at the Mont

gomery County Court House on Thursday morning?

A. [By defendant Trenholm, President of the Ala

bama State College] This statement so supports that,

and I withdraw the other statement (E. 76).

See also testimony of the witness Ingram, a reporter of

the Montgomery Advertiser:

A. My recollection is that he [the Governor] issued a

statement to the press urging that the students who

had participated in the demonstration be expelled from

College.

Q. And this occurred approximately how many

hours after the demonstration or after they had gone

to the Court House, approximately! A. It was—my

recollection is that the conference was during the af

ternoon of the day of the demonstration at the Court

House (E. 92).

Moreover, the President stated that he had no choice but

to comply with this order (E. 93).

Not only was this the instantaneous reaction of the Gov

ernor, but the President was of the opinion that plaintiffs,

by demanding service at the Montgomery lunch counter

had violated the law (E. 69).

Board member Ayers also voted for their expulsion “be

cause they violated a law of Alabama.”

Q. That [law] separating of the races in public

places of that kind [i.e. the white lunch counter at the

courthouse] (E .156).

Another Board member, Mr. Benford, also voted to expel

because “ requesting service at the Montgomery County

Court House . . . was prejudicial to the School” (E. 187).

4

Board member Benford went on to testify:

A. It might be different in Boston.

Q. Any particular reason why you would make a

distinction between Boston and Montgomery? A. No,

except just look about you and you can see (R. 187).

Among the board members who did not specifically vote

for expulsion because of plaintiffs’ request for service at

the lunch counter was member W. A. Davis, who said their

action “wasn’t nice” (R. 184), and voted to expel plaintiffs

because of “what happened before that . . . ” (R. 183). But

no charges or evidence pertaining to any activities prior

to the lunch counter request appears in the record. Board

member Davis elucidated only by saying “ there is talk and

rumors of it from the pictures and everything that was

going on” (R. 184).

Board member Stewart voted for expulsion on the

ground that plaintiffs had not requested permission to go

to the lunch counter and otherwise participate in meetings,

although there was no rule requiring that such permission

be requested (R. 199).

Therefore, the majority of the Board voted for expulsion

on the grounds of the lunch counter request, or on the

basis of undefined occurrences which took place earlier,

or which clearly constituted no violation of college rules.

Of the members other than the five discussed, supra,

member Locklin testified that he would not have expelled

solely for having requested service at the counter (R. 172),

but because students had attended a trial of a fellow stu

dent at the court house (R. 169), and because a large num

ber of students had attended a meeting at the First Baptist

Church and had gone to the State Capitol {ibid.). Board

member Word based his vote on the reports of defendants

5

Governor Patterson and Dr. Trenholm (R. 176). Board

member Faulk acted because “ these students were breaking

the rules of the College” (R. 180). Board member Albritton

testified that he voted on the basis of “ those reports and

from what [he] heard discussed” at the meeting (R. 196).

The only stricture which college authorities placed upon

antisegregation protests was that these should not take

place on the campus. With this order the students com

plied, subject only to a slight misunderstanding which was

excused (R. 166). Moreover, there is no evidence that any

of the plaintiffs ever cut a class for the purpose of partici

pating in any of these meetings (R. 116). There is no

evidence that any off-campus demonstration was disorderly

or that any laws were violated. The visit to the lunch room

was orderly (R. 138). The attendance by a large number of

students at the court hearing was entirely orderly (R. 140).

Another meeting which took place at the First Baptist

Church also was orderly (R. 140). From this meeting

some students went downtown, but there is no evidence

that the plaintiffs were among them or that the Governor

was informed that they were among them (R. 140).

Indeed while some plaintiffs were said to have been at

some of the meetings in question it appears that the Board

had no information that any particular plaintiff other than

Lee was at any particular meeting other than at the lunch

counter (see R. 114,139-141,162,164,186).

Plaintiffs received neither notice, hearing, nor an oppor

tunity to explain themselves before the decision to expel

was made (R. 106) although in all other cases of expulsion

in the history of the college hearings had been given (R.

57-58,61-62,63,72).

Following the August 26 hearing the District Court

overruled defendants’ motions to dismiss and strike and

6

denied plaintiffs’ motions for a preliminary and perma

nent injunction. The court held that plaintiffs had re

quested service at the lunch counter (R. 210), that “ several

if not all of these plaintiffs” had participated in a mass

attendance at the trial of a fellow student (R. 211); that

“ several if not all of these plaintiffs” had staged “mass

demonstrations in Montgomery” (R. 211), that “several

if not all of the plaintiffs” had participated in an anti-

segregation protest at the State Capital (R. 213), and

that “ plaintiffs, or at least a majority of them” were

leaders in an anti-segregation protest at a church near

the campus (R. 215).

These activities, it was found, promoted discord and

disorder at the college. Since, the Court ruled, there is no

constitutional right to attend a college, the authorities

were empowered to dismiss so long as their action was not

arbitrary, which, the court held, under the circumstances,

it was not (R. 220).

Specification of Error

The Court below erred in denying an injunction and re

jecting plaintiffs’ claims of due process and equal protection

of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment, includ

ing the right to oppose state imposed racial discrimination

by speech and assembly under these circumstances:

Plaintiffs, seven Negro students at Alabama State Col

lege, in an orderly fashion requested service in the County

Courthouse white-only lunchroom and were refused. Im

mediately the defendant, Governor of Alabama and Chair

man of the State Board of Education, publicly urged the

College President to expel plaintiffs.

The Court found that no particular plaintiff, but “ sev

eral” of them, thereafter participated in meetings at which

7

racial segregation was protested. After the President so

requested no further meetings were held on campus.

Without any notice or hearing, which were customary at

the College, plaintiffs were expelled for alleged violation of

a rule prohibiting conduct “prejudicial to the school” or

“unbecoming” a student, a determination made without

reference to any definition of such conduct established

before expulsion.

Argument

This case involves rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, among them

the right to be free from state-imposed racial discrimina

tion and the right to freely assemble and speak against

racial discrimination. A review of the record clearly indi

cates the essential facts which appear without contradiction.

On February 26, 1960, the plaintiffs went to a publicly

owned lunch counter in the Montgomery County court

house and requested service. Their conduct was orderly

and there were no arrests. However, solely because plain

tiffs were Negroes they were refused service. This refusal,

of course, was illegal and contravened rights f irm ly estab

lished by decisions of this Court, numerous other courts,

and the Supreme Court of the United States. See Herring

ton v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956); Henry v.

Greenville Airport Commission, 279 F. 2d 751 (4th Cir.

1960), and cases collected therein at 753. This body of

“ settled law” was mentioned in the opinion of the Court

below (R. 223).

Immediately thereafter on the same day, the Governor

of Alabama, who is Chairman of the State Board of Educa

tion, and by any reckoning its dominant member, summoned

the President of Alabama State College (a state supported

8

school for Negroes) and warned him that conduct of this

sort by students would endanger state financial support

of the College, and concluded that those who participated

in the demonstration should be dismissed.

On several succeeding days some of the plaintiffs par

ticipated in various public meetings protesting racial dis

crimination. The opinion of the Court below recites facts

relating to these demonstrations (R. 211-213). In brief,

on February 26, many students attended a trial in the

county courthouse; on February 27, there was a public

meeting, and on March 1, they attended a meeting with

hymn singing and speech making on the steps of the State

Capitol. The public meetings in which the students par

ticipated were lawful and orderly; neither the plaintiffs

nor anyone else was charged with illegal conduct at any

of the meetings. The record is also clear that the College

had no rule forbidding or requiring permission for stu

dents to participate in public meetings. When the college

president did request that meetings not be held on the

campus, the students complied. It is undisputed that plain

tiffs did not cut classes nor violate any other college rule

relevant to the case.

On March 2, 1960, the State Board of Education con

vened and on the recommendation of the college president,

voted to expel 9 students including the 6 plaintiffs and

to place 20 other students on probation. The students

were notified of this action on March 4 or 5, 1960 (R. 213-

214).

While all Board members did not vote for expulsion

for the same reason, it appears that a majority of the

Board voted for expulsion on grounds which included severe

disapproval of the lunch counter incident. Indeed, the

President was of the opinion that for Negroes to request

service at this lunch counter was in violation of the law,

9

and Board member Ayers was of the same opinion. Others

believed that the request for service was prejudicial to

the school, relied on the President’s report, believed that

plaintiffs had violated some specific rule, or voted to expel

on the basis of some completely undefined occurrences

that had occurred prior to the lunch counter incident (see,

pp. 3-5, supra).

Prior to the expulsion order the plaintiffs were given

no notice of charges against them. They were afforded

no opportunity to make any explanation or presentation

of any kind by either the College authorities or the State

Board of Education. This was so despite the fact that the

College had an informal but nevertheless entrenched tradi

tional rule that hearings are granted prior to expulsion.

The President testified:

A. We normally would have conference with the

student and notify him that he was being asked to with

draw, and we would indicate why he was being asked

to withdraw. That would be applicable to academic

reasons, academic deficiency, as well as to any conduct

difficulty.

Q. And at this hearing ordinarily that you would

set, then the student would have a right to offer what

ever defense he may have to the charges that have

been brought against him? A. Yes. (R. 57-58)

It may be noted that plaintiffs did seek an opportunity to

be heard (R. 34, Exhibit B).

The Board acted on the expulsion matter on the basis

of the President’s report and recommendations as stated

in the opinion of the Court below (R. 214). However, the

Board did not even purport to have direct knowledge of

the facts, nor even knowledge as to which of the students

attended the various public meetings. It had only the

10

President’s report that certain students were “ ringleaders

of the demonstration.” The trial court found “ several, if

not all, of the plaintiffs” were at the various meetings

(E. 211-213). The Board never heard the students’ side

of the story.

The Board’s justification for expelling the plaintiffs

was that they fermented discord and dissatisfaction on

the College campus and were ringleaders of the demon

strations. Of course, the court may take judicial notice of

the fact that in February, 1960, throughout the nation

great numbers of college students began engaging in pro

test against racial discrimination. The record so indicates

also (E. 121). See Pollitt, “ Dime Store Demonstrations:

Events and Legal Problems of the First 60 Days,” 1960

Duke Law Journal 315 (1960).

But, granting the defendants the benefit of every reason

able inference from the facts in the record favorable to

their case, it is neverthelss plain that at most plaintiffs

peacefully sought an end to racial segregation at the court

house lunch counter, attended a trial in the courthouse, and

participated in a series of public meetings held to protest

racial discriminaton. The Court below purports to rely on

the fact that “ the right to attend a public college or uni

versity is not in and of itself a constitutional right” (E.

218). But neither may the state condition the granting of

a privilege upon the renunciation of constitutional rights.

In Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

992 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, denied 311 U. S. 693, Judge Parker

held that although the Negro teachers in that case had no

right to employment as teachers, as there was no teacher

tenure in Norfolk, their employment might not be condi

tioned upon acquiescence in a racially discriminatory sal

ary scale. As to public employment, see Slochower v. Board

of Education of N. Y., 350 U. S. 551, 555; Wieman v. Upde-

11

graff, 344 IT. S. 183, 191-192; United Public Workers v.

Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75,100. As to other constitutional rights,

see: Frost v. Railroad Commission, 271 IT. S. 583; Terr ail

v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529; Hanover Fire

Insurance Co. v. Carr, 272 U. S. 494; Southern Pacific v.

Denton, 146 IT. S. 202. This has been reiterated as recently

as this term in the United States Supreme Court in which

it was held that employment as a teacher in the City of

Little Rock might not be conditioned upon requiring dis

closure of associations when such disclosure would impair

the constitutional right of freedom of association, Shelton

v. Tucker,------U. S . ------- , 5 L. Ed. 2d 231 (1960).

Therefore, the defendants could not require plaintiffs

to forfeit their constitutional rights to be served at the

lunch counter in the courthouse, or to renounce their con

stitutional right to participate in orderly meetings to pro

test racial discrimination as a condition of staying enrolled

in a state college. With reference to the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s protection of the right to associate together to pro

test racial segregation, see NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S.

449 (1958); Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 ( 1 9 6 0 ) cf.

Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344, 353, note 7.

Indeed, in this ease where rights as fundamental and

precious as those of free speech and association, as well

as the right to be free from racial discrimination are con

cerned, the injury done plaintiffs is even more egregious

than that effected in many of the above-cited cases for it

occurred without a hearing. The Court below held that “ the

fact remains where there is no statute or rule that requires

formal charges and/or a hearing, as is the case in Alabama,

the prevailing law does not require the presentation of

formal charges or a hearing prior to expulsion by the school

authorities” (R. 221). While the Court below recognizes

that the statement which it advances as the law has “been

12

criticized” (R. 221), and while it cites no authority for the

proposition that a state college need not give a hearing

(and certainly cites no authority for the proposition that

a state college which customarily affords hearings may

arbitrarily expel students without a hearing in a particular

case), plaintiffs urge that the ruling below is not the law

of this Circuit and should not be adopted by this Court.

Notice and hearing are fundamental to our form of gov

ernment. As Mr. Justice Brown said in Holden v. Hardy,

169 U. S .366, 389:

This court has never attempted to define with preci

sion the words “ due process of law,” nor is it necessary

to do so in this case. It is sufficient to say that there

are certain immutable principles of justice which inhere

in the very idea of free government which no member

of the Union may disregard, as that no man shall be

condemned in his person or property without due notice

and an opportunity of being heard in his defense.

In an annotation at 58 ALE 2d 903, 920, entitled “Right of

student to hearing on charges before suspension or ex

pulsion from educational institution” , on which the Court

below relies, and which contains a comprehensive catalog

of cases involving right to a hearing before expulsion, it

appears that in fact in all cases involving expulsion from

public institutions hearings have been held. The only dis

pute in those cases has been about the adequacy of the

hearing, a matter quite different from the question of

whether any hearing at all is in order:

The cases involving suspension or expulsion of a

student from a public college or university all involve

the question whether the hearing given to the student

was adequate. In every instance the sufficiency of the

hearing was upheld. 58 ALR 2d at p. 909.

13

As noted above, the plaintiffs were not even given the

benefit of customary procedures for a hearing. The de

parture from this settled practice in a case where defen

dants are punished for requesting equal treatment under

the law and for expressing themselves on matters of public

importance, is shocking to the conscience. An administra

tive body should, at the minimum, abide by its own rules.

See United States v. Shaughnessy, 347 U. S. 260 (1954).

The rule adopted by this Circuit for a case of this sort,

appellants respectfully suggest, should be solicitous of the

fundamental constitutional freedoms which these students

have sought to advance. It should be the enlightened view

urged by Professor Seavey for all eases of academic ex

pulsion, particularly from state institutions:

At this time when many are worried about dismissal

from public service, when only because of the over

riding need to protect the public safety is the identity

of informers kept secret, when we proudly contrast the

full hearings before our courts with those in the be

nighted countries which have no due process protection,

when many of our courts are so careful in the protec

tion of those charged with crimes that they will not

permit the use of evidence illegally obtained, our sense

of justice should be outraged by denial to students of

the normal safeguards. It is shocking that the officials

of a state educational institution, which can function

properly only if our freedoms are preserved, should

not understand the elementary principles of fair play.

It is equally shocking to find that a court supports

them in denying to a student the protection given to a

pickpocket. Seavey, “Dismissal of Students: ‘Due

Process’ ” 70 Harv. L. Eev. 1956-57, pp. 1406-7.

14

If the right here can be denied for having opposed racial

discrimination then so may the right to state employment,

cf. Shelton v. Tucker, supra, and then why not the right to

attend the public schools, cf. Wittkamper v. Harvey, 188

F. Supp. 715 (M. D. Ga. 1960), or indeed, the right to do

business within the state, Terral v. Burke Constr. Co., 257

U. S. 529 (1922), all of which, in the last analysis, are within

the power of the state to withhold.

Therefore, plaintiffs respectfully urge that the dismissals

which took place because they protested racial discrimina

tion and sought nonsegregated service at the courthouse

lunch counter were invalid for having denied due process

of law and the equal protection of the laws secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Moreover, the Court’s finding that some plaintiffs took part

in some protests in addition to that at the lunch counter is

logically consistent with a conclusion that some plaintiffs

did not take part in any other demonstration, and probably

did not participate in all the meetings, raising serious ques

tions of fact in addition to the constitutional questions, on

which a hearing, customarily given to students in cases of

expulsion, was denied. Under these circumstances, the dis

missal without hearing denied fundamental constitutional

rights.

It is submitted that the Court below erred in dismissing

the cause and in denying injunctive relief.

It was recently held in Henry v. Greenville Airport Com

mission (4th Cir. unreported No. 8247, December 1, 1960),

that:

“ The District Court has no discretion to deny relief

by preliminary injunction to a person who clearly estab

lishes by undisputed evidence that he is being denied

a constitutional right. See Clemons v. Board of Edu

15

cation, 6 Cir. 228 F. 2d 853, 857; Board of Supervisors

of Louisiana State University v. Wilson, 340 U. S. 909,

affirming 92 F. Supp. 986 . . . ”

This principle should be applied in the instant case, and

the trial court should be directed to enter an injunction as

prayed.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

Court below should be reversed, and the ease remanded

with directions for the entry of the injunction prayed

for.

Respectfully submitted,

F eed D . G ray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

T httrgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

D errick A. B e ll , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

J am es M. N abrit , III

Of Counsel

3 8