Alexander v. Riga Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Public Court Documents

June 2, 1999

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Riga Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1999. 0444b179-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/310e456f-f844-42cc-a195-fe91cad0c420/alexander-v-riga-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-and-brief-amicus-curiae-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

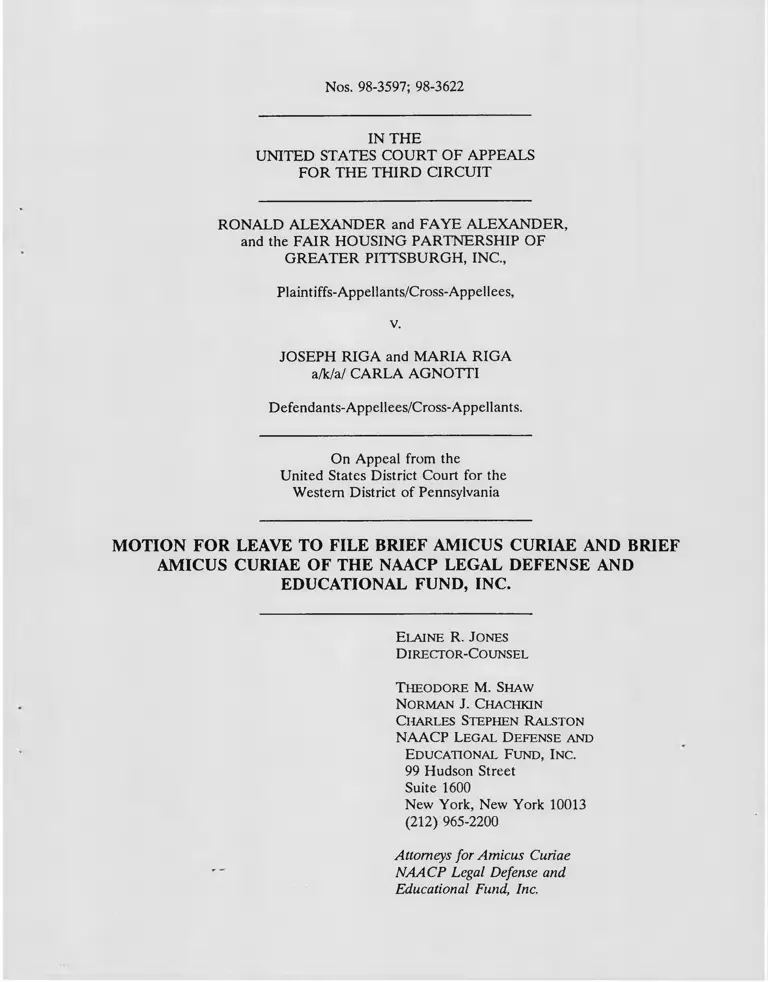

Nos. 98-3597; 98-3622

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RONALD ALEXANDER and FAYE ALEXANDER,

and the FAIR HOUSING PARTNERSHIP OF

GREATER PITTSBURGH, INC.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees,

v.

JOSEPH RIGA and MARIA RIGA

a/k/a/ CARLA AGNOTTI

Defendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the

United States District Court for the

Western District of Pennsylvania

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Elaine R. Jones

D irector-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal D efense and

Educational Fund , Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................ii

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS C U R IA E .......................... 1

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC...................................................................... 1

I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1

II. THE VIGOROUS ENFORCEMENT OF THE CIVIL

RIGHTS STATUTES BY PRIVATE PARTIES IS

ESSENTIAL TO THE CARRYING OUT OF VITALLY

IMPORTANT PUBLIC POLICY...................................................... 3

A. The Civil Rights Statutes Embody Public Policy of a

Constitutional Magnitude. ..................................................... 3

B. The Enforcement of the Civil Rights Statutes Depends

on Actions by "Private Attorneys G enera l." ........................ 6

CONCLUSION ...................................................................‘ ....................... 9

CERTIFICATE OF S E R V IC E ................................................................... 10

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)......................................8

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974).............................................5

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247 (1978)..........................................................................3

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974)....................................................................... 7

Gladstone Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91 (1979)........... 5

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987)..................................................4

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 777 F.2d 113 (3d Cir. 1985) ................................... 4

Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982)...................................... 4, 5

Jones v. Alfred E. Mayer, Inc., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)........................................... 3, 4

Kolstad v. American Dental Ass’n, S.Ct. No. 98-208 ............................................. 8

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Pub. Co., 513 U.S. 352 (1 9 9 2 )................... 5, 6, 8

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises. 390 U.S. 400 (1 9 6 8 )...................................... 6

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989).................................................. 5

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)...................................................................4

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co, 409 U.S. 205 (1972).......................... 5, 7

Walker v. Anderson Elec. Connection, 944 F.2d 841 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied 506 U.S. 1078 (1998) ..................................................................... 3

Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985)........................................................................4

ii

Pages:

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes: Pages:

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g)(2)(B)............................................................................................ 5

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ............................................................................................................. 4

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ............................................................................................................. 3

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-2(m)................................................................................................. 5

Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq........................................................1, 4, 6

Fourteenth A m endm ent............................................................................................... 3

Thirteenth Amendment ........................................................................................ 3 4

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ..................................................................... 6

iii

Nos. 98-3597; 98-3622

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RONALD ALEXANDER and FAYE ALEXANDER, and the FAIR

HOUSING PARTNERSHIP OF GREATER PITTSBURGH, INC.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees,

v.

JOSEPH RIGA and MARIA RIGA, a/k/a/ CARLA AGNOTTI

Defendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Pennsylvania

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., by its undersigned

counsel, moves, pursuant to Rule 29, F. R. App. Proc., for leave to file the

attached brief amicus curiae in the above-captioned case, in support of the

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees.* In support of this motion amicus curiae

would show the following.

‘The Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees have consented to the filing of this

brief. The Defendants-Appellees/Cross Appellants have declined to consent, thus

necessitating this motion.

1. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

corporation organized under the laws of the State of New York. It was formed

to assist African-American citizens to secure their rights under the Constitution

and laws of the United States. For many years, Legal Defense Fund attorneys

have represented parties in litigation before the Supreme Court of the United

States and other federal and state courts in cases involving a variety of

discrimination issues, including cases involving the Fair Housing Act. E.g., Curtis

v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974); Ragin v. Harry Macklowe Real Estate Co., 6 F.3d

898 (2d Cir. 1993).

2. In particular, the Legal Defense Fund has been counsel in a number of

the cases that have established the principles for awarding relief in civil rights

cases. See, e.g, Newman v. Piggie Parks Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968)

(attorneys’ fees in public accommodations cases); Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

(1978) (attorneys’ fees in § 1988 cases); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975) (back pay in Title VII cases); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) (make-whole relief in Title VII cases).

3. The central issue to be decided by this Court in this case will be

whether the district court erred in failing to grant any relief to plaintiffs who

established, by jury verdicts, that they were discriminated against by the

defendants in violation of the Fair Housing Act. Since the resolution of this

question will have broad implications for the enforcement of all federal civil

2

rights statutes, we believe that our views will be helpful to the Court.

Wherefore it is prayed that the attached brief amicus curiae be permitted

to be filed.

E l a in e R. J o nes

D ir e c t o r -C o u n s e l

T h e o d o r e M. Sh a w

N o r m a n J. Ch a c h k in

Ch a r l e s St e p h e n Ra l st o n

NAACP Le g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

3

Nos. 98-3597; 98-3622

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RONALD ALEXANDER and FAYE ALEXANDER, and the FAIR

HOUSING PARTNERSHIP OF GREATER PITTSBURGH, INC.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees,

V.

JOSEPH RIGA and MARIA RIGA, a/k/a/ CARLA AGNOTTI

Defendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Pennsylvania

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

I .

INTRODUCTION

The plaintiffs, after a lengthy trial, obtained verdicts from a jury that the

defendants had discriminated against them in violation of the Fair Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. Nevertheless, the district court declined to grant

plaintiffs any relief whatsoever, in the form of compensatory, nominal, or

punitive damages, a declaratory judgment, or equitable relief such as an

injunction, or even costs and attorneys’ fees. Thus, the net result of the plaintiffs

"victory" was that they were out-of-pocket for the expenses of the litigation. This

result, however, is completely contrary to the intent of Congress in passing the

various civil rights statutes, and is contrary to the public policy of the United

States as embodied in those statutes, that unlawful racial discrimination be

rooted out and ended.

If the decision below is allowed to stand, it can only have a chilling effect

on other victims of unlawful discrimination. There is enough of a deterrent to

the bringing of civil rights cases in the possibility that the plaintiffs will lose, and

therefore have to bear not only their own costs but, possibly, those of the

defendants. Once plaintiffs are advised that even if they "win" by establishing

that they were subject to illegal discrimination they may recover nothing, not

even the costs of vindicating their rights, they would be almost foolhardy to

continue.

Amicus has been involved in the enforcement of the civil rights statutes

since their enactment. That enforcement depends on the efforts of individual

defendants and attorneys in private practice, often single practitioners or in small

firms, to vindicate their rights. Without the willingness of private citizens and the

private bar to act as "private attorneys-general," unlawful discrimination will

continue uncorrected and endemic in our society.

2

II.

THE VIGOROUS ENFORCEM ENT OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS STATUTES

BY PRIVATE PARTIES IS ESSENTIAL TO THE CARRYING OUT OF

VITALLY IMPORTANT PUBLIC POLICY.

A. The Civil Rights Statutes Embody Public Policy of a Constitutional

Magnitude.

In its discussion denying nominal damages, the district court took the

position that the case involves "merely" a violation of "purely statutory rights,"

and that, therefore, nominal damages were not required. It followed the Eighth

Circuit in distinguishing the case from ones, such as Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247

(1978), that involved a constitutional tort. See Walker v. Anderson Elec.

Connection, 944 F.2d 841 (8th Cir.), cert, denied 506 U.S. 1078 (1998). Amicus

urges that this distinction misapprehends the nature and purpose of the civil

rights statutes.

To begin with, the various civil rights statutes were passed in order to

enforce the underlying constitutional rights embodied in the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Thus, in Jones v. Alfred E. Mayer,

Inc., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of 42

U.S.C. § 1982, which makes illegal racially discriminatory denials by private

parties of the right to buy, lease, or hold real property, by relying on the

Thirteenth Amendment. Specifically, the Court held that Congress had acted to

enforce the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition against slavery when it passed

a statute that outlawed one of the badges and incidents of slavery, he., the

3

inability to buy or lease real property. See also, Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976) (42 U.S.C. § 1981 applies to private contracts, relying on Jones v. Alfred

E. Mayer).

Thus, the Supreme Court has equated the rights guaranteed under civil

rights statutes as applied to private conduct with "constitutional torts." In

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987), the Supreme Court affirmed

this Court’s holding that the Pennsylvania two-year statute of limitations for tort

actions applied in a § 1981 action. The Supreme Court held that the statute was:

. . . part of a federal law barring racial discrimination, which, as the

Court of Appeals said, is a fundamental injury to the individual

rights of a person.

482 U.S. at 661. Therefore, the same statute of limitations applicable to actions

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (see Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985)), i.e., for

constitutional torts, governs. As this Court stated:

Present day § 1981’s predecessor was founded on the Thirteenth

Amendment that allows "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude"

to exist any longer. It is difficult to imagine a more fundamental

injury to the individual rights of the person than the evil that comes

within the scope of that amendment.

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., I l l F.2d 113, 119 (3d Cir. 1985).

These same considerations are fully applicable to actions brought under the

various civil rights statutes passed in recent years. With regard to the Fair

Housing Act itself, the Supreme Court has noted the "broad remedial intent of

Congress" embodied in it. Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363, 380

4

(1982). To effectuate this intent, the Court has consistently interpreted the

statute as giving the broadest possible standing to plaintiffs that is consistent with

the requirements of Article III. Havens', Gladstone Realtors v. Village o f

Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91 (1979); Trafftcante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co, 439 U.S.

205 (1972).

In the parallel domain of federal employment discrimination statutes the

Court has repeatedly based holdings giving those statutes the most liberal

interpretation on the principle that:

The objectives of the [employment discrimination statutes] are

furthered when even a single employee establishes that an employer

has discriminated against him or her. The disclosure through

litigation of incidents or practices that violate national policies

respecting nondiscrimination in the work force is itself important

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Pub. Co., 513 U.S. 352, 358-59 (1992) (ADEA

case). See also, Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 45 (1974) ("[T]he

private litigant [in Title VII] not only redresses his own injury but also vindicates

the important congressional policy against discriminatory employment

practices").1 Of particular importance to the enforcement scheme of the civil

rights statutes is the deterrence of future unlawful conduct, which is on at least

lSee also, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-2(m) and 2000e-5(g)(2)(B) (added by the Civil Rights Act of

1991 to overturn Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989)), which provide that

declaratory and injunctive relief, plus attorneys’ fees and costs, may be awarded where

discrimination has been found to be a factor in making the employment decision at issue, even

when the employer proves that it would have taken the same action in the absence of

discrimination.

5

equal footing with compensating individuals for injuries caused by discrimination.

McKennon, 513 U.S. at 358, and cases there cited.

Thus, the denial by the district court of any relief to the plaintiffs, in the

face of jury verdicts that they were victims of unlawful discrimination, must be

reviewed in light of the national policy against racial discrimination that the

statute violated by the defendants is intended to vindicate and enforce. The

decision below not only failed to provide any compensation for the plaintiffs, but

also would result in deterring civil rights plaintiffs from seeking redress in federal

court.

B. The Enforcement of the Civil Rights Statutes Depends on Actions

by "Private Attorneys General."

As the Supreme Court has also repeatedly noted, the civil rights statutes

depend on the initiative of individuals for their enforcement. Thus, a plaintiff

acts not just for himself alone, "but also as a ‘private attorney general’ vindicating

a policy that Congress considered of the highest priority." Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968) (attorneys’ fees to be awarded to prevailing

plaintiffs as a matter of course in actions under Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964). This principle was recognized early on with regard to the Fair Housing

Act:

. . . since the enormity of the task of assuring fair housing makes the

role of the [United States] Attorney General in the matter minimal,

the main generating force must be private suits in which . . . the

complainants act not only on their own behalf but also "as private

6

attorneys general in vindicating a policy that Congress considered to

be of the highest priority." The role of "private attorneys general"

is not uncommon in modern legislative programs. . . . It serves an

important role in this part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 . . . .

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972).

The ruling below, denying any type of relief whatsoever to private plaintiffs

who have proven they were victims of discrimination, can only undermine the

vital role of private attorneys general. Moreover, the reasons advanced by the

district court are simply insufficient to override Congress’ intent to encourage the

bringing of private actions.

The district court held that no damages, whether nominal, compensatory,

or punitive, would be awarded. We have already demonstrated above that the

basis for its decision regarding nominal damages was in error. With regard to

compensatory damages, the Supreme Court has already held that "if a plaintiff

proves unlawful discrimination and actual damages, he is entitled to judgment for

that amount." Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189, 197 (1974). With regard to

punitive damages, the district court held that they cannot be awarded unless

there is an award of compensatory damages. However, in Curtis itself, by the

time the case reached the Supreme Court, the only claim was for punitive

damages. The Court never intimated that the issue before it, whether the

defendant was entitled to a jury trial with regard to punitive damages, was moot

because the claim for actual damages had been dismissed for failure of proof.

7

415 U.S. at 190, n. I.2

With regard to declaratory and injunctive relief, the district court's reasons

for denying them are insufficient. A declaratory judgment, that the defendants

had violated plaintiffs’ rights, was clearly called for in light of the jury's verdicts.

The district court denied any injunctive relief primarily on the ground that

evidence had been presented that the defendants had rented apartments to

African Americans since the events giving rise to plaintiffs’ lawsuit. This

rationale, however, is inconsistent with the district court’s subsequent denial of

costs and attorneys’ fees to the plaintiffs. If the defendants in fact were no

longer practicing discrimination in violation of federal law, then the efforts of the

plaintiffs were wholly successful in deterring future illegal acts. As held by the

Supreme Court, such deterrence and prevention of future discrimination is one

of the two central purposes of the civil rights statutes. McKennon v. Nashville

Banner, 513 U.S. at 358; Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-

18 (1975).

Despite the plaintiffs’ success in proving discrimination and contributing

to its elimination, they received no benefits or relief. Their efforts served to

advance national policy that is of the highest priority and importance. The role

they and others perform as "private attorneys general" can only be frustrated and

2We note that the issue of the standard for awarding punitive damages, and specifically

whether it is necessary to prove more than intentional discrimination, is presently pending

decision before the Supreme Court in Kolstad v. American Dental Ass’n, S.Ct. No. 98-208.

8

destroyed if the decision of the court below is not reversed.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court below should be

reversed and the case remanded with directions to enter appropriate declaratory

and equitable relief, compensatory or nominal damages, costs, including

reasonable attorneys’ fees, and to submit the question of punitive damages to a

jury.

E l a in e R. J o n es

D ir e c t o r -C o u n s e l

T h e o d o r e M. Sh a w

N o r m a n J. Ch a c h k in

Ch a r l e s St e p h e n R a lsto n

NAACP Le g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

9

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that the undersigned is a member of the bar of this Court

and that copies of the foregoing MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., have been served by

depositing same in the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, on this

(Q yl(jo i June, 1999, addressed to the following:

Caroline Mitchell, Esq.

Attorney at Law

3700 Gulf Tower

707 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Joseph P. McHugh, Esq.

Thomas Hardiman, Esq.

Titus & McConomy

4 Gateway Center, 20th Floor

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON