Dawson v. Anderson County, TX Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2014

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dawson v. Anderson County, TX Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 2014. e4fa206b-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/312c43b2-e33c-46c3-b245-27be6fd8178d/dawson-v-anderson-county-tx-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

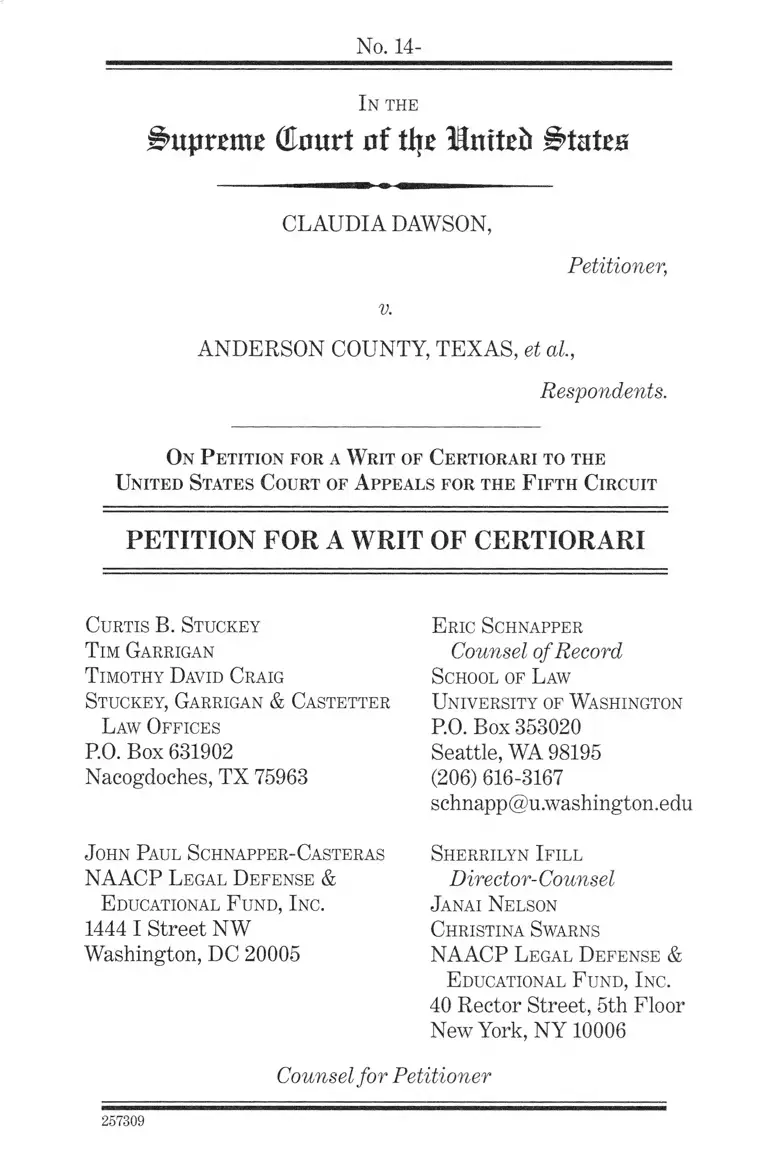

No. 14-

In THE

j^uprrmr ( ta r t at tljr lEmtrfc States

CLAU D IA DAWSON,

Petitioner,

v.

ANDERSON COUNTY, TE X A S, et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the

United States Court of A ppeals for the F ifth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Curtis B. Stuckey

T im Garrigan

T imothy David Craig

Stuckey, Garrigan & Castetter

L aw Offices

P.O. Box 631902

Nacogdoches, TX 75963

John Paul Schnapper-Casteras

NAACP L egal Defense &

E ducational F und, Inc.

1444 I Street NW

Washington, DC 20005

E ric Schnapper

Counsel of Record

School of Law

University of Washington

P.O. Box 353020

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

sehnapp@ii.washington.edu

Sherrilyn Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai Nelson

Christina Swarns

NAACP L egal Defense &

E ducational F und, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, N Y 10006

Counsel for Petitioner

257309

mailto:sehnapp@ii.washington.edu

Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989), established

the standards for determ ining whether a use o f force

violates the Fourth Amendment. Graham requires that

courts identify and w eigh the specific governm ental

interest furthered by a use of force, such as protecting

the safety of officers or the public. In this case, the Fifth

Circuit held that the Fourth Amendment permits the

use of force whenever an arrestee fails to comply with an

order, without regard to whether the order itself satisfies

the Graham standard or advances any governmental

interest. Every other circuit to address this situation

has applied the Graham standards in determining the

constitutionality of the use of force against an arrestee

who does not comply with an order.

The questions presented are:

(1) Does the Fourth Amendment permit the use of

force whenever an arrestee fails to comply with any

order?

(2) Could a reasonable officer believe that the Fourth

Amendment permits the use of force whenever an

arrestee fails to comply with any order?

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

PARTIES

The petitioner is Claudia Dawson. The respondents

are Anderson County, Texas, Greg Taylor, Karen Giles,

Cheney Farmer, Sarah Watson and Darryl Watson.

Ill

QUESTIONS P R E S E N T E D .............................................. i

P A R T IE S ................................................................................. ii

TABLE OF CON TEN TS.................................................... iii

TABLE OF A P P E N D IC E S ............................................... v

TABLE OF CITED A U T H O R IT IE S ............................. vi

OPINIONS BE LO W ...............................................................1

JU RISD ICTIO N ................................................................

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED........... 1

STATEM ENT OF TH E C A S E ......................................... 1

A. The Legal C o n te x t....................................................2

B. The Proceedings B e lo w .................................... .. • -3

REASONS FOR GRANTING TH E PETITION ..........17

I. TH ERE IS AN IM PORTANT CIRCUIT

CO N FLICT REG ARD IN G W H E T H E R

TH E GRAHAM STAN D ARD S APPLY

TO T H E USE OF FO R C E A G A IN ST

A R R E S T E E S W H O D I S O B E Y

O R D E R S ................................................................... 18

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

IV

Table o f Contents

Page

II. THE DECISION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

C O N F L IC T S W IT H T H IS C O U R T ’ S

DECISION IN GRAHAM V. CONNOR........... 25

III. T H E I M M E D I A T E L E G A L A N D

P R A C T IC A L C O N S E Q U E N C E S OF

T H E F I F T H C I R C U I T D E C IS IO N

W A R R A N T R E S O L U T IO N OF T H E

QUESTIONS PR ESE N TED W ITH OU T

FU R TH ER D E L A Y ................................................28

IV. TH IS CASE PR E SE N TS TH E ID E A L

V E H I C L E F O R R E S O L V I N G T H E

QUESTIONS P R E S E N T E D ...............................31

CONCLUSION 32

V

TABLE OF APPENDICES

Page

A P P E N D IX A — ORDER OF TH E U N ITED

S T A T E S C O U R T OF A P P E A L S F O R

T H E F I F T H C I R C U I T D E N Y I N G

R E H E A R I N G A N D R E H E A R I N G EN

BANC, DATED OCTOBER 2,2014......................... la

APPE N D IX B — OPINION OF TH E UN ITED

STATES COURT OF A P PE A LS FOR TH E

FIFTH CIRCUIT, DATED MAY 6, 2014...............11a

A P P E N D IX C — ORDER OF TH E U N ITED

ST A T E S D IS T R IC T COU RT, E A S T E R N

DISTRICT OF TE X A S, TY L E R DIVISION,

DATED OCTOBER 31,2012......................................34a

VI

CASES

TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES

Page

Abbott v. Sangamon County, Illinois,

705 F.3d 706 (7th Cir. 2013)...........................................22

Austin v. Redford Township Police Dep’t.,

690 F.3d 490 (6th Cir. 2012).................................... 21, 22

Brown v. Cwynar,

484 Fed. Appx. 676 (3d Cir. 2012)................................ 24

Buckley v. Haddock,

292 Fed. Appx. 791 (11th Cir. 2008)............................25

City of Canton, Ohio v. Harris,

489 U.S. 378(1989).......................................................... 29

Damon v. Brooks,

132 S. Ct. 2681 (2012)......................................................24

Eldridge v. City of Warren,

533 Fed. Appx. 529 (4th Cir. 2013)..............................20

Graham v. Connor,

490 U.S. 386 (1989).................................................passim

Harris v. City o f Circleville,

583 F.3d 356 (6th Cir. 2 0 0 9 ).................................. 18-19

Headwaters Forest Defense v.

County of Humboldt,

240 F.3d 1185 (9th Cir. 2001)................................ 23,24

Headwaters Forest Defense v.

County of Humboldt,

276 F.3d 1125 (9th Cir. 2 0 0 2 ) ...................................... 24

Hickey v. Reeder,

12 F.3d 754 (8th Cir. 1993).............................................30

MacLeod v. Town of Brattleboro,

548 Fed. Appx. 6 (2d Cir. 2013).................................... 24

Martinez v. New Mexico Dept, of Public Safety,

47 Fed. Appx. 513 (10th Cir. 2002)..............................24

Mattos v. Agarano,

661 F.3d 433 (9th Cir. 2011)...........................................24

Mecham v. Frazier,

500 F.3d 1200 (10th Cir. 2 0 0 7 ).................................... 24

Meirthew v. Amore,

417 Fed. Appx. 494 (6th Cir. 2011)..............................20

Norton v. Stille,

526 Fed. Appx. 509 (6th Cir. 2013)

vii

Cited Authorities

Page

19,20

Vlll

Cited Authorities

Owen v. City of Independence,

445 U.S. 622 (1980)..........................................................31

Phillips v. Community Ins. Corp.,

678 F.3d 513 (7th Cir. 2012).................................. 22,23

Plumhoff v. Rickard,

134 S. Ct. 2012(2014)............................................... 3,30

Saucier v. Katz,

533 U.S. 194(2001)............................................................ 3

Scott v. Harris,

550 U.S. 372 (2007)............................................. 3, 25, 30

Smith v. Conway County, Arkansas,

749 F.3d 853 (8th Cir. 2014)...........................................30

Stanton v. Sims,

134 S. Ct. 3 (2013)....................................................... 29

Tennessee v. Garner,

471 U.S. 1 (1985)....................................................... 3 ,27

Thomas v. Plummer,

489 Fed. Appx. 116 (6th Cir. 2012).............................. 21

Tolan v. Cotton,

134 S. Ct. 1861 (2014)

Page

18

IX

Tolan v. Cotton,

538 Fed. Appx. 374 (5th Cir. 2013)................. 13,16,18

Tolan v. Cotton,

713 F.3d 299 (5th Cir. 2013).................................... 12,18

Wells v. City o f Dearborn Heights,

538 Fed. Appx. 631 (6th Cir. 2013)........................20, 21

STATUTES AND AUTHORITIES

Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution . . . passim

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).................................................................. ..

Cited Authorities

Page

1

Petitioner Claudia Dawson respectfully prays that this

Court grant a writ of certiorari to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court o f Appeals entered

on May 6, 2014.

OPINIONS BELOW

The May 6,2014 opinion of the court o f appeals, which

is reported at 566 Fed.Appx. 369 (5th Cir. 2014), is set out

at pp. lla -33a of the Appendix. The October 2,2014, order

of the court of appeals denying rehearing and rehearing

en banc, which is reported at 769 F.3d 326 (5th Cir. 2014),

is set out at pp. la-lOa of the Appendix. The October 31,

2012 order of the district court, which is not officially

reported, is set out at pp. 34a-50a of the Appendix.

JURISDICTION

The decision of the court of appeals was entered on

May 6,2014. A timely petition for rehearing and suggestion

for rehearing en banc were denied on October 2,2014. This

Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourth Amendment provides in pertinent part,

“ The right of the people to be secure in their persons

. . . against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not

be violated . . .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989), established the

Fourth Amendment standards governing the use o f force

2

by law enforcement officials. In the instant case the Fifth

Circuit, confronted by a case which could not meet the

Graham standards, established a far-reaching exception

to Graham that would often eliminate constitutional

protection when non-lethal force is used against arrestees.

By a 10-5 vote, a sharply divided court o f appeals refused

to grant rehearing. D issenting opinions made clear

that this novel Fifth Circuit constitutional standard is

inconsistent with Graham. Because the panel decision

held that the use o f force in this case was constitutional,

the opinion has the immediate effect of according qualified

immunity throughout the Fifth Circuit for uses of force

that violate the Graham standards. The standard adopted

by the Fifth Circuit in this case conflicts with standards

in six other circuits.

A. The Legal Context

Graham v. Conner identifies three distinct elements

to be considered in determining whether a use of force by

a state violates the Fourth Amendment prohibition against

unreasonable seizures. First, “proper application [of the

Fourth Amendment reasonableness standard] requires

careful attention to the facts and circumstances o f each

particular case, including the severity o f the crime at

issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat

to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is

actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest

by flight.” 490 U.S.at 396. The particular circumstances

spelled out in this passage are widely referred to in the

lower courts as the uGraham factors.” Second, “whether

the force used . . . is ‘reasonable’ requires a careful

balancing of ‘ “ the nature and quality of the intrusion on

the individual’s Fourth Amendment interests’” against

3

the countervailing governmental interests at stake.” 490

U.S. at 396 (quoting Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1, 8

(1985)). Third, it is significant whether or not the “ police

officers [were] forced to make split-second judgments— in

circumstances that [were] tense, uncertain, and rapidly

evolving— about the amount of force that [was] necessary

in a particular situation.” 490 U.S.at 396; see Saucier v.

Katz, 533 U.S. 194,205 (2001)(applying Graham factors).

This Court’s post -Graham decisions have focused

on the risk to the public, or to law enforcement officers,

created by the individual against whom force was used.

Thus in Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372 (2007), the Court

em phasized that the plaintiff, “ racing down narrow,

two-lane roads in the dead of night at speeds that are

shockingly fast” 550 U.S. at 379, “ posed an actual and

imminent threat to the lives of any pedestrians who might

have been present, to other civilian motorists, and to the

officers involved in the chase.” Id. at 384; see Plumhoff v.

Rickard, 134 S.Ct. 2012, 2021 (2014).

B. The Proceedings Below

(1) This case concerns the use of force against a naked,

defenseless, pregnant woman.

Plaintiff Claudia Dawson is an African-Am erican

woman who, at the time o f the events giving rise to

this action, was 26 years old and in the early stages of

a pregnancy.1 In the evening of April 26, 2010, police in

Palestine, Texas stopped a vehicle in which Dawson was 1

1. Dawson Dec. If 2. The baby was born without any ill effects

later in the year.

4

a passenger. The driver got out o f the vehicle, and an

altercation with the police ensued. Dawson then exited the

vehicle, and objected to the actions of the police. The police

responded by arresting Dawson for public intoxication and

interference with public duties, both misdemeanors. App.

12a, 19a. Dawson, who insisted she had nothing at all to

drink, unsuccessfully asked to be given a breathalyzer

test.2

The Palestine police took Dawson to the Anderson

County jail to be booked on the two misdemeanor charges.

The Palestine police, for reasons that remain unclear,

asked the county jail officials to subject Dawson to a body

cavity search.3 The jail officials agreed to do so, without

making any determination of their own regarding whether

that highly intrusive search was justified.4 At the direction

of jail officials, Dawson went into a separate room used for

such searches and, in the presence of two or three female

guards— one of them armed with a pepperball gun—

removed all her clothing. Within the next few minutes a

male guard briefly entered the room, and a female guard

2. Declaration of Claudia Dawson, Doc. 23-1, par. iii (“ I

requested a breathalyzer test because I was charged with public

intoxication and I had not had anything to drink.”).

3. “Palestine Police Department. . . officers brought Dawson

to the Anderson County Sheriffs Office and requested that the

Anderson County Officers conduct a strip search. The Anderson

County officers were never informed of the basis for the PPD officers’

request for the strip search but nonetheless complied.” App. 19a.

4. Under the County Sheriffs Office Jail and Detention Policy

and Procedures, detainees, defined as individuals “held in the

facility for a short period, pending bond out or release . . . are not

normally housed with general population of inmates, and may be

held in waiting areas, holding cells, etc.” Doc. 22-10,1 (emphasis

in original).

5

shot Dawson twice with the pepperball gun. A pepperball

gun fires rounds of oleoresin capsicum powder, also known

as pepper spray. “ It is undisputed that throughout the

strip search, and while all o f the shots were fired, Dawson

was unclothed, standing within one or two feet of the wall

in the dress-out room, and was surrounded by multiple

officers, at least one of whom was armed with a pepperball

gun. It is also undisputed that Dawson never struck or

attempted to strike an officer.” App. 20a. But in other

respects what transpired during that period remains in

dispute.5

A ccord in g to Dawson, a fter she had com pletely

disrobed, the guards ordered her to squat and cough, and

she did so.6 Dawson then asked to get dressed. According

to Dawson, “ One o f the Defendant Jailers told me, ‘ I

will make you squat and cough all night until I get tired

of looking.’ I had already complied with the Defendant

Jailers’ order so I truthfully said, ‘You can’t make me

do this all night and I am not going to do it.’” Dawson

5. App. 22a (“the record evidence presents a factual dispute as

to whether Dawson wTas argumentative during the strip search or

rather whether any verbal noncompliance on her part was justified

given the officer’s alleged harassment. The Defendants testified

that Dawson was belligerent, screaming, and non-cooperative.

Comparatively Dawson testified that she did not yell at the officers

and merely said, in response to the threat that she would have to

squat and cough all night, that : ‘You can’t make me do this all

night and I am not going to do it.’”); App. 4a (“Dawson testified

that she complied with the initial command to ‘squat and cough.’

Anderson County contends she did not comply at all.”).

6. Dawson Dec., 11 v (“I squatted and coughed in compliance

with the order.”); Dawson Dep. 97 (“Q— They asked you to squat.

And you did that on your owm? A. Yes, sir. Q. And they asked you

to cough, and you did that on your own? A. Yes sir.”).

6

Dec., If vi.7 W hile Dawson and the female guards were

disagreeing about whether Dawson could be required to

squat and cough all night, “a guy stuck his head in and

told her, I tell you what to do with her shoot her with the

pepper ball gun.” Dawson Dep. 65-66. “ [He] could see me.

I was standing there in the middle stripped naked” (id. 73);

the male officer, a Sergeant, was in the room for 15 to 20

seconds. Id. 74. Dawson told the male officer he should not

be in the room. Id. 72, 73. The guard with the pepperball

gun then fired three rounds. The first round missed. The

second round hit Dawson in the abdomen. “When she shot

me in the stomach and I went down to my knees, I told

her that she could not be shooting me with no pepperball

gun because I was pregnant.” Id. 83; see id. 30 (Dawson

asked guard not to shoot her because she was pregnant),

83 (same), 81 (after jailer “ shot me in the stomach, I kind

of went in the fetal position.” ). The guard shot Dawson

again, this time hitting her on her leg. The two rounds

that struck Dawson broke the skin and caused “substantial

bleeding.” Dawson Dec., If x. During the period when the

shooting occurred, according to Dawson, the guards were

laughing. Dawson Dep., 82,83,88; see App. 15a (“Dawson[]

assert[s] that . . . the defendants laughed at her and made

abusive comments.” ).8 One guard remarked “ I wish I was

7. Dawson Dep., 65 (“They were just telling me to . . . squat,

and cough. I did that once. And one of them— I don’t know which

one of them told me that we were going to sit here and do this all

night. And when she told me that, I told her I done done it for them

once and I wasn’t going to sit there and do that all night. And I

asked her for my little clothes to dress out in.”).

8. App.l9a-20a (“Officers Sarah Wells and Cheneya Farmer

took Dawson into the ‘dress-out room’ where they instructed

Dawson to remove her clothes. One undressed, Dawson was

ordered to squat down and cough. Dawson attests that she

7

certified to shoot this bitch up with the pepper ball gun.”

Id. 66-67.

The guards give a different account of the shooting.9

They testified that although Dawson had removed all her

complied with this initial order. Once the strip search was in

progress, a third officer, Karen Giles, entered. According to

Dawson, after she had already complied with the order to squat

and cough, one of the officers then stated that she would force

Dawson to ‘squat and cough all night until [she got] tired of looking.’

Dawson asserts that in response, without yelling, she told the

officers that she could not be forced to squat and cough all night.

Promptly after this exchange, Sergeant Darryl Watson briefly

entered the dress-out room and instructed Officer Giles to shoot

Dawson with a pepperball gun. Officer Giles then fired the first

shot, which did not hit Dawson. Giles quickly fired the second shot,

which hit Dawson in the left side of her abdomen, causing her to

bend over in a ‘fetal position.’ Dawson attests that she then told

the officers that she could be pregnant and, if she was, that they

could not shoot at her. Officer Giles than fired the third shot, which

hit Dawson in her right knee. According to Dawson, the two shots

broke her skin and caused substantial bleeding. Dawson further

alleges that throughout the strip search, the officers laughed at her

expense and were verbally abusive. One female officer allegedly

stated that she *wish[ed] [she] was certified to shoot this bitch up

with the pepper ball gun.’ ”)

9. App. 36a (“In contrast, Defendants claim that Plaintiff did

not initially comply with the squat-and-cough order. Defendants

assert that Plaintiff was belligerent, used profanity, and yelled that

she was not going to squat and cough. Giles then entered the search

room and observed Plaintiff’s noncompliance. Giles also observed

that Plaintiff was moving closer to one of the jailers, arguing, and

screaming at the jailers in a threatening manner. Giles then told

Plaintiff to comply with the squat-and-cough order. When Plaintiff

still did not comply, Giles fired three shots at Plaintiff from the

pepperball gun. Plaintiff then complied with the order.”)

8

clothes as directed, she had refused to squat and cough.10 11

The guards stated that they had fired the pepperball gun

as a method of forcing Dawson to squat and cough, which

she did only after being struck by two of the pepperballs.

They claimed that Dawson had laughed after being struck

in the abdomen by the second round.11 There is no dispute,

however, that the male Sergeant wTas in the room at one

point during the body cavity search. And the Sergeant

expressly acknowledged that it was only necessary for an

arrestee to squat and cough a single time.12 “ [N ]o officer

indicated a problem with the first ‘squat and cough.” ’

App. 5a.

10. Farmer Dep. pp. 15,16, Doc. 22-5.

11. Giles Dep. 46, 51, 53.

12. Watson Dep., Doc. 23-4, p. 18:

“Q. Now, if she did squat and cough one time when she

was told to, as has been testified to by Ms. Dawson,

then that would have been in compliance, wouldn’t it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And it would be wrong to have her get down and

squat again?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Because they don’t have any business harassing

these people?

A. Right.

Q. You agree with that?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you wouldn’t put up with that?

A. No, sir.”

9

Dawson was released the next morning. She went

to a local hospital for treatment o f the wounds caused

by the pepperball rounds. Dawson testified that the two

rounds that struck her, both fired at close range, had

caused pain that lasted for several months, and had left

scars still visible several years later. Dawson Dep., 33.

The prosecuting attorney did not pursue charges against

Dawson.

Dawson commenced this action in federal district

court, naming as the defendants four guards, the County

S h eriff, and A n derson C ounty.13 A fte r a p eriod o f

discovery, the defendants moved for summary judgment.

In support of that motion, the defendants asserted that

it was “ undisputed” that Dawson had refused to comply

with the order to squat and cough.14 15 Dawson’s response

em phasized that this assertion was in fact squarely

disputed, noting that she had repeatedly insisted in her

deposition that she had complied with the first squat and

cough order, and had objected only to the order that she

resume squatting and coughing “all night.”16 Dawson

13. The complaint alleged that the use of the pepperball gun

was authorized by county policy. The official policy of the County

Sheriffs Office states that “The Anderson County Sheriffs Office

will utilize the Pepperball systems as an attempt to overcome

resistance from persons who clearly refuse to obey lawful

directions given them by officers.” Doc. 22-9, Anderson County

Sheriffs Office: Use of Force: Pepperball Deployment Systems, 1;

see id. at 4 (“the Pepperball system is a viable means of attempting

to bring suspects into compliance.”)

14. Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment, 3-4,18,19.

15. Plaintiffs Response in Opposition to Defendants’ Motion

for Summary Judgment and Brief in Support, 20.

10

argued that the order to squat and cough all night served

no legitimate government purpose at all, citing testimony

by the Sergeant involved that there was no need for her

to squat and cough more than once.16 Dawson urged the

court in determining the constitutionality o f the use of

the pepperball gun to apply the standards in Graham v.

Connor.

The d istrict court acknow ledged that there was

conflicting testimony about whether Dawson had obeyed

the first order to squat and cough. “ The Court recognizes

that there is a factual dispute about whether Plaintiff

complied with the squat-and-cough order before being shot

with the pepperball gun.” App. 42a. It reasoned, however,

that the individual defendants were entitled to summary

judgment even on Dawson’s version of the facts, because

Dawson admitted having disobeyed the order to continue

squatting and coughing indefinitely, and because it was

undisputed that, rather than merely failing to obey that

order, she had explained to the guards that she thought

she could not be required to do that. “ Plaintiff conceded

that the jailers told her to squat and cough a second time

and that she did not obey. Furthermore, it is undisputed

that Plaintiff was arguing with the jailers.” App. 42a

(footnote omitted). The court concluded that the guards

were entitled to qualified immunity, because they could

reasonably have concluded that the use of the pepperball

gun under such circum stances was constitutionally

permissible. “ [A] reasonable jailer, faced with an arguing,

non-compliant arrestee, who was moving toward another

jailer, could have believed that [the guards’] actions were

16. Id. 17.

11

lawful.” App. 43a.17 The district court did not consider

whether the use of force satisfied the specific factors

established by Graham; instead, it deemed the fact an

arrestee had failed to obey an order sufficient by itself to

justify the use of force, especially where the arrestee gave

a reason for not complying. The district court dismissed

on other grounds the claims against Anderson County

and the Sheriff. App. 48a.

On appeal18 Dawson urged that the district court had

erred in failing to apply the Graham factors, emphasizing

that she had not been charged with a dangerous offense,

that she was not attempting to flee or actively resist arrest,

and that she denied having taken any action that posed any

threat to the safety of the officers.19 Again she pointed to

undisputed testimony by the Sergeant on the scene that

squatting and coughing a single time was all that was

necessary to complete the body cavity search.20 The Fifth

Circuit acknowledged that there was a factual dispute

about whether Dawson had com plied with the initial

order to squat and cough, and thus about whether any

government purpose would have been served by forcing

17. The statement that Dawson was “moving toward” a jailer

was controverted by testimony by the defendants that Dawson

(indisputably naked and unarmed) at all times remained within

one or two feet of the wall. App. 23a. The court of appeals did not

rely on this contested factual assertion.

18. The court of appeals held that under Fifth Circuit precedent

Dawson’s claim was governed by the Fourth Amendment. App.

13a n. 3.

19. Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, 19.

20. Id., 8.

12

her to do so again (and again). “ Contrary to her jailers,

Dawson stated she initially complied with their directive

to ‘squat and cough’ during the strip search— This initial

compliance rem oved any need for the pepperball gun

. . . and, she contended, its use therefore was excessive.”

App. 13a.

The Fifth Circuit, in a 2 -to -l decision, nonetheless

concluded that the pepperball shooting was constitutional.

The panel majority held that a mere refusal by an arrestee

to obey any order— even in this case an order that she

squat and cough “all night”—justifies the use of force.21

We cannot conclude that all reasonable officers

would believe that the use o f force in this case

violated the Fourth Amendment, because it

is undisputed that Dawson did not com ply

with successive search com mands given at

her arrestee intake encounter. Even crediting

her that she obeyed at first, Dawson admitted

refusing a renewed command to “ squat and

cough.” Law enforcement officers are within

their rights to use objectively reasonable force

to obtain com pliance from prisoners............

21. The Fifth Circuit’s holding that disobedience to an order

can suffice to justify the use of force was presaged to some degree

by that Circuit’s decision in Tolan v. Cotton. “ Robbie Tolan’s

refusing to obey a direct order to remain prone violated [Texas

law] . . . . Such refusal, under the circumstances, could have

reinforced an officer’s reasonably believing Robbie Tolan to be a

non-compliant and potentially threatening suspect. Robbie Tolan

could have avoided injury by remaining prone as Officer Edwards,

with pistol drawn, had ordered him to do.” 713 F.3d 299, 308 (5th

Cir. 2013).

13

Measured force achieved compliance with the

officers’ search directives in this case, again,

crediting as we must, Dawson’s contention that

she complied at first but then refused a search

order given twice believing it to be abusive.

M easured force on an arrestee who refuses

immediately successive search orders cannot

be deemed objectively unreasonable under our

qualified immunity caselaw.

App. 13a-14a (footnote omitted). The Fifth Circuit did

not consider whether this use of force could satisfy the

Graham factors; indeed, the majority opinion never refers

to Graham at all. On its view, the disobedience of any order

by an arrestee is inherently sufficient by itself to justify

the use of force. The Court o f Appeals’ decision was not

limited to the individual defendants’ claims of qualified

immunity; it concluded that the use of the pepperball

gun was for these reasons “objectively reasonable,” i.e.

constitutional. App. 13a n. 3. It therefore dismissed the

claims against Anderson County and the Sherriff on the

ground that there had been no constitutional violation. Id.

Judge Dennis22 dissented, objecting that the panel’s

per se rule perm itting use of force against any non

complying arrestee was inconsistent with Graham. App.

lla -3 3 a . “ W ithout applying the Graham factors, the

majority summarily concludes that because Dawson was

non-compliant, the officers’ use of force was objectively

reasonable to achieve compliance and thus the Defendants

are entitled to qualified immunity.” App. 27a. Judge Dennis

22. Judge Dennis wrote the dissenting opinion in Tolan. 538

Fed. Appx. 374, 375 (5th Cir. 2013)(en banc).

14

analyzed the case under the Graham factors— as the panel

had not— and easily concluded that the use of force was

unconstitutional.23 The dissent objected that the panel’s

order-obedience doctrine permitted the use of force to

compel compliance with an order that was unlawful or

baseless, a result inconsistent with Graham; under the

Graham standard, Judge Dennis emphasized, the use of

force would be unconstitutional if, as Dawson testified,

she had already complied with the order to squat and

cough.24 The Sergeant in charge, he stressed, had agreed

23. App. 27a-28a:

First, Dawson was in custody for two misdemeanor

charges, neither of which involves accusations of

violence. Thus the first Graham factor—the severity

of the crime—militates against concluding that the

Defendants’ use of force was objectively reasonable.

̂ ̂ ^

[T]he second Graham factor—the individual’s threat

to officer safety— similarly supports a conclusion that

Defendants’ conduct was not objectively reasonable.

Viewing the evidence in the light most favorable

to Dawson, she . . . was unarmed, unclothed, stood

within one to two feet of the dress-out room’s wall,

was surrounded by multiple armed officers, and did

not attempt to strike an officer. On this record, viewing

the evidence in her favor, Dawson did not pose a threat

to the officer’s safety.

❖ ❖ ^

[T]he third Graham factor—whether the plaintiff

actively resisted the officers— also supports a

conclusion that the officer’s use of force was objectively

unreasonable.

24. “Sergeant Watson’s acknowledgement that a detainee

would be in compliance if he or she obeyed the first order to squat

15

that squatting and coughing a single time was sufficient.

App. 20a, 21a. “ Crediting all reasonable inferences in

Dawson’s favor, she presented record evidence that she

never resisted the officer’s lawful directives. Rather,

the evidence regarding her refusal to squat and cough

after she initially complied with officers’ orders may

reasonably be construed as a verbalized denial to consent

to an unlawful, abusive order and thus would not qualify

as ‘active resistance’ and would not justify the officer’s

resort to force.” App. 28a. Application o f the Graham

standard, Judge D ennis also concluded, precluded

qualified immunity. “ Under Graham, a reasonable officer

would have sufficient notice that using a pepperball gun to

repeatedly shoot a naked, possibly pregnant, compliant,

non-threatening detainee who merely stated she would

not comply with an abusive command, clearly constitutes

excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

App. 28a-29a.

Dawson petitioned for rehearing and rehearing en

banc, again arguing that her constitutional claim should

have been evaluated under Graham.25 26 A sharply divided

and cough—read in conjunction with Dawson’s testimony that

she did just that— creates a genuine issue of material fact as to

whether Dawson’s behavior was in fact non-compliant. . . . ” App.

21a-22a.

25. Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, 7-9.

In their brief opposing rehearing en banc, the defendants

embraced the panel’s reasoning, arguing that the use of force was

constitutional because “Dawson admits that she refused to comply

with at least one order to squat and cough. . . . Dawson contends

that she initially complied but then refused subsequent orders to

squat and cough.” Response to Petition for Rehearing En Banc,

16

court o f appeals denied rehearing en banc, over the

objection of five judges.* 26 In an opinion dissenting from

the denial o f rehearing en banc, Judge Haynes expressed

particular disagreement with the panel’s order-obedience

doctrine because it permitted the use o f force to compel

compliance with any order, and thus would apply to the

use of force to compel an arrestee to obey an entirely

illegitimate order. The dissent questioned whether “an

arrestee is required to follow any order from a group

o f armed jailers, regardless o f how ridiculous, or face

a pepperball to force compliance.” App. 5a. “ [IJt would

be unreasonable for a jailer to take Dawson’s refusal to

comply for the jailer ’s amusement a second time (after

already squatting and coughing), without more, as license

to begin shooting pepperballs at her.” App. 4a. “ [R]

equiring her to ‘squat and cough’ ‘all night long’ just to

humiliate her is not a legitimate basis upon which to use

force, such as a pepperball shot, to obtain compliance.”

App. 5a. “ No case law suggests [that a body cavity search]

can be conducted for any reason other than to assure

officers there is nothing hidden inside the cavity.” App. 4a.

Dawson alleged that the jailers laughed at her

and were verbally abusive throughout the strip

search . . . [T]he alleged statements inform the

3-4 and n. 4; see id. 6 (“Because Dawson admits that she refused

to comply with the order to squat and cough (at least once),. . . the

Panel did not err in concluding that Giles’ and Watson’s actions were

not objectively unreasonable under qualified immunity case law.”).

26. The judges who voted for rehearing en banc in this case

included all the judges who had voted for rehearing en banc in

Tolan. Compare App. 2a with Tolan v. Cotton, 538 Fed.Appx. 374,

375 (5th Cir. 2013)(en banc).

17

question of whether . . . the commands were

legitim ate or for harassm ent and, in turn,

whether force was justified to obtain compliance.

In examining. . . whether the commands were

consistent with a need for security or simply

done for sport, the alleged contemporaneous

comments support a conclusion that it was the

latter, not the former. . . . The facts as alleged

by Dawson . . . suggest a level of sadism and

brutality that is totally unacceptable.

App. 9a-10a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

The Fi f th Circuit in this case has adopted an

unprecedented and far-reach in g constitutional rule

that m aterially subverts a quarter century o f Fourth

Amendment jurisprudence regarding the use of force by

law enforcement officials.

The decisions in Graham v. Connor and its progeny

carefully balance the public and private interests at stake

when force is used, assuring the ability of law enforcement

officers to protect themselves and the public from harm,

while preventing the use o f unnecessary force. The

circumstances alleged in this case could not conceivably

satisfy the Graham standard; neither the defendants nor

the courts below suggested that there was any legitimate

government interest in requiring an arrestee who has

already submitted to one body cavity search to continue

squatting and coughing, naked and surrounded by guards,

until the guards grew weary of that spectacle.

18

The Fifth Circuit— in a decision with far greater

ramifications that its decision in Tolan v. Cotton, 713

F.3d 299 (5th Cir. 2013), rehearing en banc denied, 538

Fed. Appx. 374 (5th Cir. 2013)(en banc), rev’d per curiam

134 S. Ct. 1861 (2014)— created a loophole which permits

wholesale evasion o f Graham. Under the decision below,

disobedience of any order by an arrestee is sufficient to

justify the use of force to compel compliance, regardless of

whether the order itself advances a sufficient governmental

in terest to sa tisfy Graham. A s the dissents below

correctly warned, that Fifth Circuit’s order-obedience

constitutional rule sanctions the use of force to compel

obedience to an order that serves no legitimate purpose

at all, the very circumstance alleged in this case.

The court of appeals decision conflicts with decisions in

six other circuits, and has the immediate effect throughout

the F ifth Circuit o f according qualified immunity for

conduct that violates the standards in Graham.

I. THERE IS AN IMPORTANT CIRCUIT CONFLICT

REGARDING W HETHER THE GRAHAM

STANDARDS APPLY TO THE USE OF FORCE

AGAINST ARRESTEES WHO DISOBEY ORDERS

The Fifth Circuit order-obedience doctrine conflicts

with the decisions in six other circuits, which correctly

apply the Graham standards when force is used against

an arrestee who does not comply with an order.

The Sixth Circuit has in a wide variety of circumstances

utilized the Graham factors in resolving claims regarding

the use o f force against arrestees who disobey an order.

In Harris v. City of Circleville, 583 F.3d 356 (6th Cir.

19

2009), while the plaintiff was being booked, the officers

escorting him instructed him to kneel down. Harris did

not obey the order, although “other than not complying

with the command to kneel down, Harris was not doing

anything to resist.” 583 F.3d at 361. In response, officers

struck the back of his knees as a take-down maneuver.

The Sixth Circuit applied the Graham factors in holding

this use of force unconstitutional, and in rejecting qualified

immunity.27 In Norton v. Stille, 526 Fed.Appx. 509 (6th

Cir. 2013), the plaintiff while being booked defied the

directions of an escorting officer by “p icking] up a paper

towel to blow her nose as well as a bottle o f soda, stating

that she needed something to drink.” 526 Fed.Appx. at

510-11. The Deputy pinned Norton to the wall and used a

take-down technique to force her to the floor. Applying the

Graham factors28, the court of appeals held that the use

of force was unconstitutional, and that qualified immunity

was not available, even if “ Norton may have defied [the

27. 583 F.3d at 366:

We conclude that the Graham factors weigh against

the Officers. Harris was accused o f . . . not particularly

serious crimes and none of them involve violence. In

addition, Harris did not pose an immediate threat

to the Officers or anyone else at the . . . Jail..........

[UJnder Harris’s version of the facts, he did not

actively resist at any time.

28. 526 Fed.Appx. at 512-13:

All of the Graham factors . . . favor a finding of

excessive force. First, Norton’s crime was not

particularly serious.. . . Second, Norton never posed

any real threat to [the officer]___Finally, Norton was

not actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade

arrest by flight.

20

Deputy] by grabbing a tissue, paper towels, and a soda

bottle.” 526 Fed.Appx. at 513. In Meirthew v. Amove, 417

Fed.Appx. 494 (6th Cir. 2011), while the plaintiff was being

booked, an officer ordered her to spread her feet in order

to facilitate a pat down search. The plaintiff refused to

spread her feet, continually moving them together after

the officer kicked them apart; the officer used an arm-bar

take-down in an effort to obtain compliance. Applying the

Graham factors, the court o f appeals concluded that the

use of force was unconstitutional and that the officer was

not entitled to qualified immunity.29

The Sixth Circuit has also applied the Graham factors

to claims that excessive force was applied to an arrestee

who disobeyed an order while being taken into custody.

In Eldridge v. City of Warren, 533 Fed.Appx. 529 (4th

Cir. 2013), police shot a taser at an arrestee who did not

obey an order to get out of his truck. See 533 Fed.Appx.

at 532-35 (applying Graham factors). “ W hether the

officers receive qualified immunity . . . turns on whether

failing to comply with an officer’s commands, with nothing

more, constitutes active resistance------[NJoncompliance

alone does not indicate active resistance; there must be

something more.” 533 Fed.Appx. 533-34. In Wells v. City

of Dearborn Heights, 538 Fed.Appx. 631 (6 th Cir. 2013),

29. 417 Fed.Appx. at 497-98:

[A]ll the Graham . . . factors favor a finding of

excessive force. First, the underlying crimes allegedly

committed by Meirthew were not severe-----Second,

Meirthew did not pose an immediate threat at

the police station. . . . Finally, Meirthew was not

attempting to resist or evade arrest by flight..........

While Meirthew refused to spread her feet to be

searched, such resistance was minimal.

21

officers fired a taser at an arrestee who, while lying on

the ground, violated officers’ order by attempting to roll

over onto his back and see what was happening. 538 Fed.

Appx. at 637-39 (applying Graham factors). In Thomas v.

Plummer, 489 Fed.Appx. 116 (6th Cir. 2012), police shot

with a taser an arrestee who, when ordered to lie on the

ground, instead got down on her knees and put her hands

in the air. “ Thomas did not lie face-down on the ground as

[the] Officer . . . ordered.” 489 Fed.Appx. at 127; see 489

Fed.Appx. at 125-26 (applying Graham factors).

In Austin v. Redford Township Police Dep’t., 690

F.3d 490 (6th Cir. 2012), police twice fired a taser at an

arrestee, seated in a police car, who disobeyed an order to

put his feet inside the car. The Sixth Circuit rejected the

defendants’ argument that the usual Graham standards

did not apply because Austin had violated an order by

the officers:

Defendants. . . raise a . . . purely legal argument

that this C ircu it’s precedent on the use of

excessive force on subdued and unresisting

subjects is irrelevant to situations involving

noncom pliance with police orders. Instead,

they argue that [the officer’s] two discharges

of his Taser in order to gain compliance with

his order for Austin to put his legs in the police

car did not violate any clearly established

constitutional right. . . . Our “ prior opinions

clearly establish that it is unreasonable to use

significant force on a restrained subject, even if

some level of passive resistance is presented.”

Meirthew v. Amove, 417 Fed.Appx. 494, 499

(6th Cir. 2011). . . . Although Defendants cite

22

non-binding authority from other courts for

the proposition that use of a Taser to obtain

com pliance is ob jectively reasonable, each

o f those cases involved the potential escape

o f a dangerous cr iminal or the th reat o f

immediate harm, neither of which is present

h e re . . . . Defendants’ legal argument that this

C ircuit’s precedent on the use o f excessive

force on subdued and unresisting subjects is

irrelevant to situations involving noncompliance

with police orders fails.

690 F.3d at 497-99.

The Seventh Circuit applies the Graham factors to

excessive force claims by arrestees who disobey an order,

and generally bars the use o f force against arrestees

whose disobedience is limited to passive resistance. In

Abbott v. Sangamon County, Illinois, 705 F.3d 706 (7th

Cir. 2013), the court o f appeals held that police violated

clearly established Fourth Amendment rights when they

fired a taser at an arrestee who, while lying on the ground,

disobeyed an order to roll over onto her stomach. “ [N]

one of the three Graham factors provide a justification

for the . . . tasing..........[Although [the plaintiff] did not

comply with [the officer’s] order to turn over onto her

stomach . . . , she did not move and at most exhibited

passive noncompliance and not active resistance.” 705

F.3d at 730. In Phillips v. Community Ins. Corp., 678 F.

3d 513 (7th Cir. 2012), police fired a “baton launcher” at

an arrestee who did not obey an order to get out o f her

car. The Seventh Circuit concluded under Graham that

this violated clearly established Fourth Am endm ent

rights. “ Phillips was never ‘actively resisting arrest,’

23

a touchstone o f the Graham analysis. . . . The officers

argue that Phillips demonstrated continuous ‘defiance’ by

failing to follow their commands to exit the vehicle___ To

the extent that Phillips’s perceived conduct could be

considered ‘resistance’ at all, it would have been passive

noncompliance . . . 678 F.3d at 524-25. A dissenting

opinion in that case agreed that the plaintiff’s claims

were governed by Graham. 678 F. 3d at 531 (Tinder, J.,

dissenting).

The Ninth Circuit has repeatedly dealt with this issue

in the context of demonstrators who, after having been

placed under arrest, passively resist orders to cooperate

when being taken into custody. In Headwaters Forest

Defense v. County of Humboldt, 240 F.3d 1185 (9 th Cir.

2001), a group of nonviolent environmental activists staged

a sit-in in the lobby of a lumber company. They linked

hands through a device that police could remove by using

a metal grinder. Rather than do that, police ordered the

protesters to release themselves, and when they failed to

do so an officer applied pepper spray to the corners of their

closed eyes. The resulting pain caused the demonstrators

to comply with the police orders to disengage from one

another. 240 F.3d at 1193. Applying the Graham factors,

the Ninth Circuit held that the use of the pepper spray

violated the Fourth Amendment. 240 F.3d at 1199-1204.

Under the Fourth Am endm ent, using such

a “ pain compliance technique” to effect the

arrests o f nonviolent protesters can only be

deemed reasonable force if the countervailing

governm ental in terests w ere particu larly

strong. The protestors posed no safety threat to

anyone. Their crime was trespass. T h e . . . lock-

24

down device they used meant that they could not

“ evade arrest by flight.” Graham, 490 U.S. at

396___ [T]he need for the force used during the

protests falls far short of supporting a judgment

as a matter o f law in favor of the defendants.

240 F.3d at 1205. A subsequent decision held that the

constitutional violation was sufficiently obvious to preclude

qualified immunity. Headwaters Forest Defense v. County

of Humboldt, 276 F.3d 1125 (9th Cir. 2002). In Mattos

v. Agarano, 661 F.3d 433 (9th Cir. 2011)(en banc), cert,

denied sub nom. Damon v. Brooks, 132 S.Ct. 2681 (2012),

the Ninth Circuit applied Graham in concluding that the

Fourth Amendment was violated by the use of a taser

against a pregnant arrestee who refused to get out o f her

car. 661 F. 3d at 443-46.

Four other circuits have applied Graham to cases

in which police used non-lethal force on an arrestee

who failed to obey a police order. MacLeod v. Town of

Brattleboro, 548 Fed.Appx. 6 (2d Cir. 2013)(taser fired

at arrestee who disobeyed order to lie on ground; use of

force constitutional because the plaintiff was a dangerous);

Brown v. Cwynar, 484 Fed.Appx. 676 (3d Cir. 2012)(taser

fired at arrestee who refused to release his hands so he

could be handcuffed; use of force constitutional because

arrestee had struggled with police); Martinez v. New

Mexico Dept, of Public Safety, 47 Fed.Appx. 513,515 (10th

Cir. 2002)(arrestee sprayed with mace when she refused to

get into back of police car; use of force unconstitutional and

violated clearly established rights); Mecham v. Frazier,

500 F.3d 1200,1204-05 (10th Cir. 2007)(arrestee sprayed

with pepper spray when she refused to get out o f her car;

use of force constitutional because dangerous location of

25

car required prompt resolution); Buckley v. Haddock, 292

Fed.Appx. 791 (11th Cir. 2008)(arrestee shot with a taser

when he refused to obey an order to get up o ff the ground

and get into a police car; use of force constitutional because

location o f arrestee near busy highway endangered the

arrestee, police, and passing motorists).

II. THE DECISION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT’S DECISION

IN GRAHAM V. CONNOR

This case involves, not a dispute about the meaning of

Graham, but an outright refusal by the Fifth Circuit to

apply the Graham standards. As the dissenting opinions

below made clear, the Graham standards apply to all

uses of force subject to the Fourth Amendment, and are

not limited by an exception for cases in which an arrestee

has failed to comply with an order by a law enforcement

official. The effect o f the Fifth Circuit’s order-obedience

doctrine is to create a major loophole in this C ourt’s

Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, one which officials

can to some degree manipulate.

Like all decisions applying the Fourth Amendment’s

reasonableness standard, Graham d irects courts to

identify “ the countervailing governm ental interests”

that are advanced by a disputed use of force. 490 U.S. at

396. In Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372, 383-84 (2007), the

Court explained that “ in judging whether [Deputy] Scott’s

actions were reasonable, we must consider the risk of

bodily harm that Scott’s actions posed to [the plaintiff]

in light o f the threat to the public that Scott was trying

to eliminate.” 550 U.S. at 383 (emphasis added). Under

the Fifth Circuit’s order-obedience doctrine, however, a

26

court never considers whether public safety or any other

governmental interest is at stake; the mere existence o f a

disobeyed order renders that inquiry irrelevant, even in

a case in which— as here— the order, and thus the use of

force itself, may not serve any governmental interest at

all. In this case, the Sergeant on the scene acknowledged

that if— as Dawson testified— she had already obeyed

an order to squat and cough, there would have been no

need for her to do so again (and again); under Graham

that acknowledgement would have been dispositive of the

summary judgment motion.

Graham directs courts to assess the extent to which

force— rather than some other governmental measure— is

necessary to protect the governmental interest at issue.

It is for that reason that the non-exclusive list o f factors

set out in Graham are all concerned with immediate

threats to public safety, a compelling interest that often

requires the near-instantaneous solution that force alone

may provide. Graham “requires careful attention to the

facts and circumstances of each particular case, including

the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect

poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers

or others, and whether [the plaintiff] is actively resisting

arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight.” 490 U.S.

at 396 (emphasis added). But the court o f appeals—

unlike the dissenting opinion—did not consider any of

these “ require[d]” factors, and disregarded all other

“ circum stances o f [the] case,” except for the fact that

Dawson had disobeyed an order.

Graham also “requires a careful balancing of “ ‘the

nature and quality of the intrusion on the individual’s

Fourth Amendment interests’” against the countervailing

27

governmental interests at stake.” Id. (quoting Tennessee

v. Garner, 471 U.S. at 8)(emphasis added). But the court of

appeals, applying its order-obedience doctrine, engaged in

no such balancing; indeed, in the absence of any identified

purpose for an order requiring Dawson (as she alleged) to

squat and cough until the guards were bored, there would

have been no countervailing government interest to weigh

against the intrusion on Dawson’s Fourth Amendment

interests caused by the pepperball shootings.

In addition , un der Graham “ [t]he ca lcu lu s o f

reasonableness must em body allowance for the fact

that police officers are often forced to make split-second

judgments— in circumstances that are tense, uncertain,

and rapidly evolving— about the amount of force that

is necessary in a particular situation.” 490 U.S. at 396

(emphasis added). Conversely, the absence of such exigent

circumstances would under Graham also be a necessary

consideration. But in the F ifth Circuit, whenever an

arrestee disobeys an order, that aspect of Graham is also

irrelevant.

Under the Graham standards, to be sure, the refusal

of an arrestee, or anyone else, to obey an order could be

a consideration bearing on the governmental interest

at stake, and thus might properly be considered along

with all other relevant circumstances. But it is palpably

inconsistent with Graham to hold that the use of force is

permissible in response to every act of noncompliance with

any order under all circumstances. There is a difference

o f constitutional magnitude between disobeying an order

to “drop your gun,” disobeying an order to “ tell me your

name,” and disobeying an order to “wipe that smile off

your face.”

28

III. THE IMMEDIATE LEGAL AND PRACTICAL

CONSEQUENCES OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

DECISION WARRANT RESOLUTION OF THE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED WITHOUT FURTHER

DELAY

The necessarily dramatic and immediate impact the

decision below will have on qualified immunity in the Fifth

Circuit weighs heavily in favor of review by this Court.

Civil actions to redress constitutional violations

are a linchpin of the rule o f law. The possibility that

law en forcem en t o ffic ia ls m ay be held p erson a lly

accountable for violating constitutional rights provides

them with a powerful incentive to conform their conduct

to constitutional standards. At the same time, qualified

im m unity p rotects law en forcem ent o ffice rs i f the

existence o f the constitutional right in question was not

clearly established at the time of an asserted violation.

The backdrop o f judicial decisions by this Court and the

lower courts thus determines the scope of that immunity,

and shapes the conduct o f law enforcement officials and

agencies.

Prior to May 6, 2014, the date of the panel decision

in this case, no law enforcem ent official in the F ifth

Circuit, or elsewhere, could reasonably have believed

that the use of force would be constitutional whenever

an arrestee violated any order; the decisions in Graham

and its progeny were clearly to the contrary. But the

issuance of the single opinion in this case has overnight

changed that situation throughout the Fifth Circuit. In

that circuit today, any official who uses “measured force”

against a disobedient “arrestee” would be entitled to

qualified immunity, because he or she could point to the

29

panel decision in this case as holding that, regardless

of any other circumstances, such a use o f force would

be constitutional. App. 14a. “ [A]ctions that [are] lawful

according to courts in the jurisdiction where [a defendant]

acted” are the quintessential example of conduct accorded

qualified immunity. Stanton v. Sims, 134 S.Ct. 3 ,7 (2013).

Any uncertainty about when an individual becomes an

“arrestee,” or about what constitutes “ measured force,”

under the decision below, will further expand the range

of actions protected by qualified immunity.

The Fifth Circuit’s order-obedience doctrine, because

limited to arrestees, provides officials with a significant

incentive to arrest members of the public before issuing

whatever orders they may see fit, since doing so will permit

the use o f force that might otherwise be unconstitutional.

Government lawyers in the Fifth Circuit can be expected

now to advise their clients that in dealing with arrestees

they no longer have to conform to the more demanding

requirements of Graham. Under City of Canton, Ohio v.

Harris, 489 U.S. 378, 392 (1989), cities and counties face

liability for supervision or training practices which reflect

a “deliberate indifference t o . . . constitutional rights — ”

That liability, and the incentives for cities and counties

to engage in practices consistent with Graham, have

also been largely undercut by the decision below; a local

government could not be said to be deliberately indifferent

to a right that the Fifth Circuit in this case has announced

does not exist.

The particular importance o f the decision below is

not its impact on the limited number of cases that may

actually be litigated, but its consequences for everyday

law enforcement and jail practices throughout the Fifth

Circuit. The panel decision virtually invites jails to post

30

signs like that once utilized in a county jail reading:

“ Failure to immediately comply with orders of jail staff,

you will be t a s e d Smith v. Conway County, Arkansas, 749

F.3d 853,855 (8th Cir. 2014). The Eighth Circuit correctly

struck down that practice, explaining that “ ‘[t]he law does

not authorize the day-to-day policing of prisons’ . . . by

taser.” 749 F.3d at 861 (quoting Hickey v. Reeder, 12 F.3d

754,756 (8th Cir. 1993). But today in Texas, Louisiana, and

Mississippi, the day-to-day policing o f jails and booking

areas by taser, pepperball gun, pepperspray, and mace

has the approval of the United States Court of Appeals

with jurisdiction over those states. The Fifth Circuit has

also sanctioned the use outside of such facilities of those

chem ical agents and other pain-infliction techniques

whenever an arrestee disobeys an order, agents and

techniques that are forbidden in other circuits except

when their use is consistent with the Graham standards.

The delineation and enforcement o f the constitutional

line separating permissible and impermissible uses of

force are matters of great public importance; recent events

have significantly increased public concern with that

distinction. This Court granted review in Scott v. Harris

and Plumhoff v. Rickard to correct misapplications of the

Graham standards, and did so even in the absence of any

dispute in those cases about the governing constitutional

standards. The decisions in Scott and Plumhoff reiterated

the importance of according proper weight to the vital

governm ental interest in protecting the safety of the

public and law enforcement officials. This case concerns

the other side of the Graham balance: the shooting o f a

pepperball gun at a naked, defenseless, pregnant woman

cowering in a fetal position and imploring guards to hold

their fire. It is no less deserving o f review by this Court

than the petitions in Scott and Plumhoff.

31

IV. THIS CASE PRESENTS THE IDEAL VEHICLE

FORRESOLVINGTHEQUESTIONSPRESENTED

The F ifth C ir c u it ’s o rd e r -o b e d ie n ce d o c tr in e

originated in this case; it should end here as well.

The decision below rests solely on the Fifth Circuit’s

new constitutional standard. Because the court of appeals

held the use of force constitutional, it dismissed not only

the claims against the individual guards but also the

claims against Anderson County. A county may not assert

qualified immunity. Owen v. City of Independence, 445

U.S. 622 (1980). Thus if review were granted, regardless

o f whether the individual defendants might be entitled to

qualified immunity, this Court could determine whether

the claim asserted by Dawson is governed by the Graham

standard and constituted a constitutional violation.

The panel did not purport to apply to Dawson’s claim

the Graham standards that are utilized in all other

circuits in deciding the constitutionality o f a use o f force

against a non-compliant arrestee. The two dissenting

opinions correctly explain that the use of force alleged

in this case could not satisfy Graham. I f review were

granted, this Court could reach that issue, and itself apply

Graham to the circumstances of this case; the Court could

also take the more limited step o f holding that Graham

indeed establishes the controlling legal standards, and

then remand the case to the lower courts with instructions

to apply those standards.

32

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a writ o f certiorari should

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Curtis B. Stuckey

T im Garrigan

T imothy David Craig

Stuckey, Garrigan & Castetter

L aw Offices

P.O. Box 631902

Nacogdoches, TX 75963

John Paul Schnapper-Casteras

NAACP L egal D efense &

E ducational F und, Inc.

1444 I Street NW

Washington, DC 20005

E ric Schnapper

Counsel of Record

School of Law

University of Washington

P.O. Box 353020

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

schnapp@u.washington.edu

Sherrilyn Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai Nelson

Christina Swarns

NAACP L egal Defense &

E ducational F und, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, N Y 10006

Counsel for Petitioner

mailto:schnapp@u.washington.edu

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX A — ORDER OF THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT DENYING REHEARING AND

REHEARING EN BANC, DATED OCTOBER 2, 2014

IN TH E U N ITED STATES COURT OF A P PE A LS

FOR TH E FIFT H CIRCU IT

No. 12-41223

Claudia DAWSON,

Plaintiff-Appellant

v.

Anderson County, Texas; Sheriff Greg Taylor; Jailer

Karen Giles; Jailer Cheneya Farmer; Jailer Sarah

Watson; Jail Sergeant Darryl Watson,

Defendants-Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Texas

ON PETITION FOR RE H E A R IN G AN D

R E H E A R IN G EN BANC

(Opinion May 6, 2014, 556 F.Appx. 369)

[Oct. 2, 2014]

Before SM ITH , D E N N IS, and HIGGINSON, Circuit

Judges.

2a

HIGGINSON, Circuit Judge:

The Petition for Rehearing is DENIED. Judge Dennis

dissents from the denial of panel rehearing for the reasons

stated in his panel dissent of May 6, 2014, Dawson v.

Anderson County, Texas, 566 Fed. Appx. 369,371-79 (5th

Cir.2014) (Dennis, J., dissenting), and the dissent from the

court’s denial of rehearing en banc.

The court having been polled at the request o f one

o f its members, and a majority of the judges who are in

regular active service and not disqualified not having

voted in favor (Fed. R.App. P. 35 and 5th Cir. R. 35), the

Petition for Rehearing En Banc is also DENIED.

In the en banc poll, five judges voted in favor of

rehearing (Judges Jolly, Dennis, E lrod, Haynes, and

Graves) and ten judges voted against rehearing (Chief

Judge Stewart and Judges Davis, Jones, Smith, Clement,

Prado, Owen, Southwick, Higginson, and Costa).

H A Y N E S , C ircu it Judge, jo in ed by D E N N IS and

G RAVES, Circuit Judges, dissenting from Denial o f

Rehearing En Banc:1

Police officers put their lives on the line every day

to keep us safe, and I am grateful for the fact that we

have men and women willing to serve for relatively low

1. Judge Dennis joins this dissent for the reasons set forth

herein and for the reasons set forth in his dissent from the panel

opinion. Dawson v. Anderson Cnty., 566 Fed.Appx. 369, 371-79

(5th Cir.2014) (Dennis, J., dissenting).

Appendix A

3a

pay in these essential positions. The doctrine of qualified

immunity recognizes that split-second decisions made in

(literally) life and death situations should not be second-

guessed by judges or juries far removed from the scene.

However, immunity for officers is qualified, not absolute.

The fact that Section 1983 liability exists in the first place

recognizes that when a person is given a badge and a gun,

the potential for abuse o f power exists. The doctrine of

qualified immunity is not meant to protect officers who

behave abusively. Cfi Ramirez v. Martinez, 716 F.3d 369,

373, 378-79 (5th Cir.2013) (upholding denial of summary

judgment where officer tased suspect after he had been

handcuffed and subdued).

Appellant Claudia Dawson accused several jail officers

o f using excessive force by issuing unreasonable orders

for sport and shooting her with a pepperball gun when

she refused to comply. The panel majority opinion found

the jailers entitled to qualified immunity based on its

conclusion that law officers may use “measured force”

against an arrestee who refuses immediately successive

search orders. Dawson, 566 Fed.Appx. at 370-71 (majority

opinion). Because there are genuine issues o f fact as to

whether the force was objectively reasonable, I conclude

that the majority opinion erred in affirming the district

court’s opinion.

The Supreme C ourt’s recent decision in Tolan v.

Cotton reminds us that, for summary judgment motions

based on qualified immunity, the facts must be viewed in

context and in the light most favorable to the nonmovant.

----- U .S .--------- , 134 S.Ct. 1861, 1866, 188 L.Ed.2d 895

Appendix A

4a

(2014). A fter Dawson was arrested and brought to the

jail, she was asked to “squat and cough” while undressed

in the presence o f four armed jailers. The stated reason

for the “ squat and cough” was that the jailers needed to

determine whether Dawson had secreted contraband or

weapons on her person. Dawson testified that she complied

with the initial command to “ squat and cough.” Anderson

County contends she did not comply at all. The jailers

asked Dawson to “ squat and cough” again, allegedly

stating that they would make her “squat and cough” “all

night long.” Dawson refused. At some point, the jailers

responded by shooting her with a pepperball gun to force

compliance.

As we must view the facts in the light most favorable

to Dawson, we must assume she did com ply with the

initial command. Assuming Dawson complied, a jury could

infer that the jailers were not concerned about safety

at all but rather were issuing unreasonable orders for

sport. See Tolan, 134 S.Ct. at 1867-68 (vacating grant of

summary judgment where “a ju ry could reasonably infer

that [the plaintiffs] words, in context, did not amount to a

statement of intent to inflict harm” ). In that light, it would

be unreasonable for a jailer to take Dawson’s refusal to

comply for the jailer ’s amusement a second time (after

already squatting and coughing), without more, as license

to begin shooting pepperballs at her. No case law suggests

this sort of procedure can be conducted for any reason

other than to assure officers there is nothing hidden inside

the cavity. As such, summary judgment was improper.

Appendix A

5a

I recognize, however, that the fact that a case is

wrongly decided on the merits is not, by itself, a basis

for en banc rehearing. Fed. R.App. P. 35(a). This case

presents larger questions that would benefit from en banc

consideration. W here is the line between a legitimate

security protocol and governm ent oppression? W hat

standard should apply when the alleged victim of police

abuse has been arrested but is not yet processed for

pretrial detainment? Both questions are worthy of this

full court’s attention. I therefore dissent from the court’s

decision not to rehear this case en banc.

I agree that Supreme Court precedent makes a strip

search with a “squat and cough” arguably permissible for

an initial search. Florence v. Bd. of Chosen Freeholders

of Cnty. of Burlington,----- U .S .-------- , 132 S.Ct. 1510,182

L.Ed.2d 566 (2012). But does Florence mean an officer can

make a naked, defenseless arrestee “ squat and cough”

“all night long?” Once an arrestee “ squats and coughs,”

how many more times must she comply? Is an arrestee

required to follow any order from a group o f arm ed

jailers, regardless of how ridiculous, or face a pepperball

to force compliance? W here is the line? Dawson argues

that since she complied once, and no officer indicated a

problem with the first “ squat and cough,” requiring her

to “squat and cough” “ all night long” just to humiliate her

is not a legitimate basis upon which to use force, such as

a pepperball shot, to obtain compliance. I submit that we

cannot and should not tolerate unnecessary harassment

and humiliation of arrestees for the amusement of officers.

Appendix A

6a

Further, we lack clarity as to which standard should

apply to determine whether the use of force was excessive

in this case. When a plaintiff alleges that a government

official has employed “ excessive force” in violation of

the Constitution, several constitutional standards are

potentially applicable (the Fourth, Eighth, and Fourteenth

Amendments). W hether a particular standard applies

turns on the plaintiff’s status during the relevant time

period.

At one end of the timing spectrum are excessive force

claims arising during the initial arrest or apprehension

o f a free citizen, which are governed by the Fourth

Am endm ent. As explained by the Supreme C ourt in

Graham v. Connor, when an “ excessive force claim

arises in the context o f an arrest or investigatory stop

of a free citizen, it is most properly characterized as one

invoking the protections of the Fourth Amendment, which

guarantees citizens the right ‘to be secure in their persons

... against unreasonable... seizures’ o f the person.” 490 U.S.

386, 394,109 S.Ct. 1865,104 L.Ed.2d 443 (1989) (quoting

U.S. Const. Amend.. IV). Analysis of a Fourth Amendment

excessive force *329 claim involves consideration of the

need for force and the so-called Graham factors: the

“ severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses

an immediat e threat to the safety of the officers or others,

and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting

to evade arrest by flight.” Id. at 396,109 S.Ct. 1865.

At the other end of the spectrum are excessive force

claim s arising during incarceration , a fter crim inal

prosecution is complete. A convicted inmate’s excessive

Appendix A

7a

force claim is governed by the Eighth Amendment. As

explained by the Supreme Court in Hudson v. McMillian,

“whenever prison officials stand accused of using excessive

physical force in violation o f the Cruel and Unusual

Punishments Clause [of the Eighth Amendment], the core

judicial inquiry is ... whether force was applied in a good-

faith effort to maintain or restore discipline, or maliciously

and sadistically to cause harm.” 503 U.S. 1 ,6 -7 ,112 S.Ct.

995, 117 L .Ed.2d 156 (1992). Analysis o f an excessive

force claim under the E ighth Am endm ent includes

consideration of the Hudson factors: “ [1] the extent o f the

injury suffered; [2] the need for the application of force;

[3] the relationship between the need and the amount of

force used; [4] the threat reasonably perceived by the