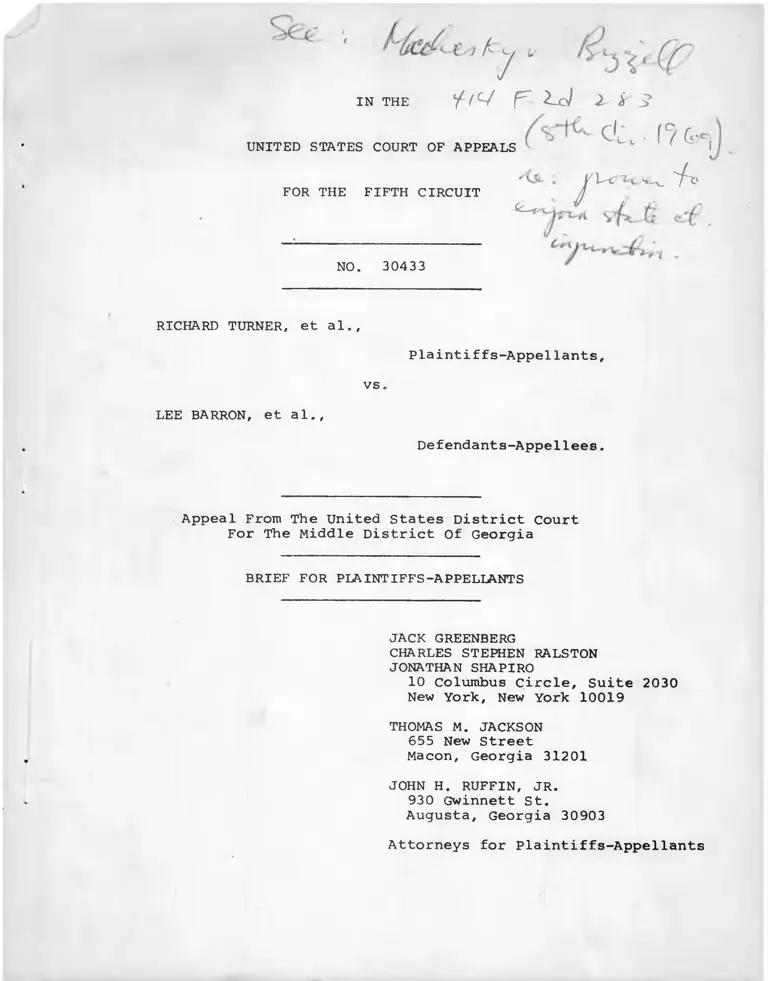

Turner v. Barron Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 19, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Turner v. Barron Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1970. 14881d0f-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3130daba-9c1e-4751-896f-5071ad2abf61/turner-v-barron-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

A7

IN THE '■>J>//<v r 2-cJ -2 i'

c t . . f? G-UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS I

f v* ^ "fx̂

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30433

^ I \ ■

RICHARD TURNER, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs,

LEE BARRON, et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

JOHN H. RUFFIN, JR.

930 Gwinnett St.

Augusta, Georgia 30903

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

I N D E X

Page

ISSUES PRESENTED ........................................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ..................................

STATEMENT OF FACTS .....................................

The Arrests of February 6, 1970 ...............

Mistreatment of Demonstrators ................ .

Intimidation of Black Citizens By Boycotters

IV

6

7

9

9

ARGUMENT

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN HOLDING THAT

IT WAS BARRED FROM ISSUING A DECLARATORY

JUDGMENT REGARDING THE CONSTITUTIONALITY

OF THE CHALLENGED ORDINANCES AND COURT

ORDER ........................................... 11

II. THE SANDERSVILLE CURFEW ORDINANCES AND

THE COURT ORDER LIMITING DEMONSTRATIONS

ARE OVERBROAD REGULATIONS OF FIRST

AMENDMENT RIGHTS .......................... .

A.

B.

The Loitering and Curfew Ordinances

in Flatly Prohibiting All Demonstra

tions Regardless of Circumstances,

Unduly Restrict the Exercise of First

Amendment Rights .........................

The Court Order Banning all Marches

In The Vicinity Of the Courthouse Is

Similarly Overbroad ....................

15

15

21

Page

III. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN NOT ENJOINING

THE USE OF VIOLENCE BY LAW OFFICERS

AGAINST ARRESTED DEMONSTRATORS ..........

IV. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN GRANTING

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AGAINST PLAINTIFFS ...

CONCLUSION ................................................

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................

Table of Cases

Abernathy v. Conroy, 429 F.2d 1170 (4th Cir. 1970)

Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968) ...........

Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F.Supp. 492

(M.D. Ala. 1966) ......................................

Cox V. New Hampshire 312 U.S. 569 (1941) ..........

Davis V. Francois, 395 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1968) ..

Guyot V. Pierce, 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967) ....

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1938) ...............

Kelly V. Page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) ......

22

24

26

28

20

13

20

17, 19

12, 18, 21

12

23

23, 25, 27

11

page

LeFlore v. Robinson ______ ^F.2d ______ (5th Cir.

NOV.12, 1970) ...........................................

Robinson v. Coopwood, 292 F.Supp. 926 (N.D. Miss.

1968) .....................................................

Shuttlesv/orth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S.

147 (1969) ..............................................

Ware v. Nichols, 266 F. Supp. 564 (N.D. Miss. 1967)

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F.Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala.

1965) .....................................................

Young v. Davis, 9 Race Rel. L. Rev. 590

(M.D. Fla. June 9, 1964) .............................

Zwickler v. Koota, 387 U.S. 241 (1967) ..............

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 2283 .........................................

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .........................................

11, 12,19

21

20

17

12

24

20

12

5, 12, 13,

14.

12

111

ISSUES PRESENTED

I. Whether the court below erred in holding that it could

not grant declaratory relief regarding the constitutionality

of city loitering and curfew ordinances and a state court

order banning demonstrations in certain public places on

the ground they violated the First Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States?

II. Whether the above mentioned ordinances and court order

are unconstitutional on their face as being overbroad

regulations of activities protected by the First Amendment?

III. Whether the court below erred in failing to make findings

of fact and failing to grant injunctive relief when pre

sented with evidence showing mistreatment by law enforce

ment officers of arrested demonstrators?

IV. Whether the court below erred in issuing an injunction

against the plaintiffs-appellants that unduly restricts

their exercise of rights protected under the First

Amendment?

IV

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30433

RICHARD TURNER, et al,,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

LEE BARRON, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District

Court For The Middle District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action commenced in the United States Court

for the Middle District of Georgia seeking to challenge the con

stitutionality on their face and as applied of the loitering

V

and curfew ordinances of Sandersville, Georgia and a court

order restricting marches and demonstrations in that city.

'̂ / The full text of the Ordinances and court orders are

as follows:

A declaratory judgment was sought that the ordinances and

court order on their face and as applied violated freedom

of speech, assembly, and the right to petition for a redress

of grievances, as guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the constitution (A. 16-18) (References are to

(Continued)

̂ Section 277 of the City Code:

"It shall be unlawful for any person or persons to

lounge and loiter after 9 o'clock p.m. on any

street, sidewalk, alley or square of said city,

provided this section shall not apply to a person

returning home from his legitimate business or

occupation or other like cases. Any person

violating this section is guilty of an offense

against the city, and upon conviction, shall be

punished as provided for in the code of said c i ty ."

Order dated February 11, 1970:

"BE IT ENACTED BY THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF

SANDERSVILLE, that a curfew is hereby established

in the City of Sandersville from the hour of

11:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. during which time it

shall be unlawful for any person or persons to

lounge, loiter, congregate, assemble, walk, march,

parade, or be present on any street, sidewalk,

alley, square, or public property in the City of

Sandersville, provided this ordinance shall not

apply to any person returning home from his

legitimate place of business, going to his legi

timate place of business, or in the transaction

of his legitimate business employment.

"This ordinance is enacted in confirmation of

verbal proclamation of the Mayor of the City of

Sandersville establishing and implementing this

curfew, and does not invalidate or in any manner

alter Section 277 of the City Code, which remains

of force.

"This ordinance and the proclamation above cited

are enacted and proclaimed due to the state of civil

unrest which the Mayor and Council of the City of

Sandersville deem to exist at the present time, which

- 2 -

Appellant's Appendix (A); page citations are to the pagination

found at the top of each page). Injunctive relief was also

requested against the arrest and prosecution of persons for

violating the ordinances and court order, and specifically

against the prosecution of persons arrested on certain speci

fied dates in the past. An injunction was also sought against

any form of harassment or intimidation of persons attempting

**/

to exercise their First Amendment rights (A. 17).

jl/ (Continued)

conditions cause the Mayor and Council to judge that

it is in the public interest and for the public safety

necessary that such curfew be enforced."

Order dated February 5, 1970, of City Court:

"Whereas, the City Court of Washington County is now

in session at the Court House on the Public Square

in Sandersville and the Traverse Jury of the City

Court are deliberating cases at said Court House.

"Therefore, it is considered, ordered, and ad

judged that no marches or demonstrations shall be

held on the Court House Square or in the streets

and subdivision surrounding the Court House Square

on this date or thereafter during the time that

said court is in session. This shall specifi

cally include that portion of North Harris Street

that forms a portion of the Court House Square.

"The Sheriff, his Deputies, and all law enforce

ment officers are directed to route all parties

that may be involved in a march or demonstration

to another part of the city in compliance with

this order."

**/ An injunction against prosecuting certain persons for tres

passing on the driveway of a bank during the course of a

demonstration at the adjoining Board of Education building

was also sought. In light of the findings of fact by the

court below, however, this issue is not raised in this

appeal.

-3-

The action was commenced on March 9, 1970, by the

plaintiffs as individuals and as representatives of the class

of black citizens who had in the past and who wished in the

future to exercise their First Amendment rights, but who had

been arrested and threatened with prosecutions pursuant to the

ordinances and order (A. 2-3). They wished to continue their

constitutionally protected activities but the pendency of pro

secutions, the threat of future arrests and prosecutions, and

the use of violenceby police officials had the effect of dis

couraging them in so doing so that the exercise of those rights

had been deterred and chilled (A. 14-15).

The defendants-appellees are officials of the city

of Sandersville and of Washington County, Georgia, including

the chief of police, the mayor, the sheriff, city and county

attorneys, members of the city council, and judge of the city

court. All of these officials are responsible for the pro

mulgation and enforcement of the challenged ordinances and

court order.

On March 11, April 7, 17, and 24, 1970, the district

court held an evidentiary hearing. During the proceedings, a

cross-complaint was filed by the defendants seeking injunctive

relief against the plaintiffs for alleged acts of violence and

intimidation (A. 53-55). Testimony was given (which is sum

marized below) concerning events in Sandersville and Washington

County in late 1969 and early 1970. Briefly, it dealt with

-4-

demonstrations held by black citizens to protest certain

policies and actions by the city and the county board of

education, a boycott of white-owned business, various inci

dents of violence in the county, arrests made during demon

strations, and acts of violence against arrested demonstrators.

On July 9, 1970, the district court handed down its

decision (A. 829-845). After reciting certain findings of

facts, the court held that it was barred from granting either

declaratory or injunctive relief. Its conclusion was based

on the applicability of 28 U.S.C. § 2283, the federal anti

injunction statute, which it said barred enjoining pending

state criminal prosecutions. As a corollary, the court held

that it could not issue declaratory relief since that would

have the effect also of interfering with pending state prosecutions.

Therefore, all of the plaintiffs' prayers for relief were denied

without the court reaching the merits of the constitutional

issues raised (A. 840-845).

The Court did not discuss the plaintiffs' request for

a declaration and injunction regarding the future enforcement

of the ordinance. Nor did it make any findings of facts con

cerning or indeed discuss, the evidence dealing with police

mistreatment of demonstrators. On the other hand, the court

did make findings regarding defendants' allegations of misconduct

on the part of the plaintiffs (A. 835-837). As a result of

those findings the court enjoined the plaintiffs from certain

-5-

conduct as they carried out their boycott (A. 847). The

court's order was entered on July 14, 1970 (A. 846-847) and

a timely notice of appeal was filed (A. 848).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The demonstrations giving rise to this case came out

of discontent among black citizens of Sandersville, Georgia,

with policies of the board of education, the local government,

and local businesses. At various times parades and marches

took place mainly at the offices of the board of education.

In addition, a boycott of local business establishments was

organized and pickets and demonstrators were sent out to attempt

to persuade other black citizens not to shop at those stores.

During the period involved, from October 1969, through

April, 1970, when the hearings below were held, marching and

picketing occurred regularly. On January 30, 1970, a series

of arrests of demonstrators was made under an ordinance pro

hibiting parades. When this resulted in mass protests, however,

the arrested demonstrators were released, the ordinance was res

cinded, and no prosecutions were held under it (A. 832).

Subsequently, a number of demonstrations were held

which b y and large resulted in no arrests. During this same

period, however, various incidents not directly connected to

specific demonstrations occurred, including fires, shooting

-6-

into houses, threatening telephone calls, etc. On December

27, 1969, the mayor issued a proclamation declaring a curfew

from 11.00 p.m. to 5.00 a.m. This action was ratified by a

meeting of public officials on December 31, 1969, and on

February 11, 1970, the curfew was formalized into an ordinance.

Before that date, however, there had been in effect

an earlier ordinance prohibiting loitering after 9.00 p.m. and

which was used to arrest a group of demonstrators in an incident

discussed in more detail below. In the meantime, the judge of

the city court issued an order generally and flatly banning all

marches and demonstrations in the vicinity of the courthouse

square (the two ordinances and the court order are set out in

full in the footnote, supra). It is against this general

background that the incidents that gave rise to this litigation

occurred.

The Arrests of February 6, 1970

In the early afternoon of February 6 about forty—three

young people began to walk to the office of the board of educa

tion in Sandersville in order to talk to the superintendent of

schools about the closing of a school (A. 109-110). The office

is located on Harris Street, which adjoins the courthouse square.

As they approached the square on Harris Street, but before they

reached it, they were stopped b y local police and the state

patrol (A.111). They were informed that they could not walk

on the street adjacent to the square because of the court order

-7-

mentioned above (A.112-113). When the marchers refused to

turn back or to go through an alley they were arrested, in

carcerated for from four to six days, and ultimately convicted

of contempt of court (A. 116; 127). The group itself made no

noise, and informed the police officers they did not intend to,

but were merely walking to the board of education (A. 126).

Later that afternoon, another group of marchers went

to the board of education and marched around the building.

The board of education building had next to it a driveway to

the parking lot of a bank. As the group circled the building

they walked on the driveway. Subsequently, the demonstrators

were arrested for trespassing on bank property, allegedly

because they had been asked by a bank official to remain off

the driveway but had refused (A. 129-131; 142-143; 152-153;

369-374).

Later that evening, a group of black citizens, includ-.

ing parents of children arrested earlier in the day, went down

to the jail in Sandersville. When it appeared that the

children were not to be released, they resolved to spend the

night outside the jail in order to reassure the children and

to protest the arrests (A. 196-199). One mother testified

that her son called out to her from his cell but was apparently

struck b y someone who appeared to be an officer. (A. 200). The

group went back to their meeting place, resolved to get blankets,

and return to the jail for their vigil (A. 203-204).

- 8-

They returned at sornetime between 10.30 p.m and

11.00 p.m. An announcement was made that the group was

violating the curfew and when the people remained they were

arrested, put into busses, and taken to jail (A. 204-205;

212—214). One woman had gone down independently of the group

because someone at the s h e r i f f s office suggested she come to

speak to the sheriff concerning the arrest of her children.

Nevertheless, she was also arrested although, according to

testimony, white persons who were standing watching were not

(A. 185-189; 226-229). She was charged with and convicted of

a violation of section 277 of the city code, the anti-loitering

after 9.00 p.m. provision (A. 188-189).

M istreatment of Demonstrators

A number of witnesses testified to mistreatment of

demonstrators both during and after the making of arrests.

Tear gas or mace was sprayed into cells (A. 76; 90-91; 149;

188; 206-207). Prisoners inside of the jail were assaulted

(A. 200; 209-210; 212-213), as were demonstrators as they were

arrested (A. 186-187; 214; 223-224). Police evidently des

troyed pictures one of the persons arrested at the bank had

taken of the demonstration and arrests (A.148).

Intimidation of Black citizens By Boycotters

In support of their cross complaint defendants—

appellees introduced considerable testimony dealing to their

allegations regarding intimidation of black citizens of

-9-

Washington County to gain adherence to the boycott of white

businesses (see, generally, A. 537-736). Plaintiffs, in turn,

offered testimony denying such acts and denying any intent to

intimidate people into co-operating with the boycott (see, e.g.

A. 96-97). Since the district court made findings of fact

regarding these matters (in contrast with its failure to do so

regarding allegations of mistreatment by police officers) we

will not describe the testimony here, but refer the Court to

the district court's opinion (A.835-837).

- 10 -

ARGUMENT

I.

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN HOLDING THAT

IT WAS BARRED FROM ISSUING A DECLARATORY

JUDGMENT REGARDING THE CONSTITUTIONALITY

OF THE CHALLENGED ORDINANCES AND COURT

ORDER

This is another in a continuing series of cases

that raises the issue of the role of the federal courts in

ensuring that the rights peacably to assemble, to petition

for a redress of grievance, and to free speech are not abridged.

Plaintiffs-Appellants urge that in a number of respects this

case is governed by the recent decision of this Court in

LeFlore v. Robinson,__________ F.2d __________(5th C i r . , Nov. 12,

1970). Specifically, that decision clarified and reiterated

the power and duty of a federal court to issue a declaratory

judgment when city ordinances are challenged as violating the

First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution because of

overbreadth, even when prosecutions under those ordinances are

pending in state courts.

Here, related loitering and curfew ordinances, used

to arrest persons engaged in peaceful demonstrations, were

challenged as being overbroad. In addition, challenge was made

to a state court issuing ex parte and pursuant to no pending

action, an order having the essential effect of an ordinance

banning all demonstrations regardless of circumstances on the

- 11 -

streets along the courthouse square.

Although the decision of the court below began with

a statement of the facts as it saw them, the actual holding

of the court did not deal with the merits of this action.

Rather, it rested on the grounds that 28 U.S.C. § 2283 barred

injunctive relief against pending state prosecutions and that

therefore declaratory relief also as to the constitutionality

of the challenged ordinances and injunctive could not be given.

For these reasons, all prayers for relief, declaratory and

injunctive, were denied.

However, in LeFlore this Court specifically rejected

such an approach. Rather, it held that regardless of the ulti

mate resolution of the question of whether 42 U.S.C. § 1983 was

an exception to the anti— injunction statute, a federal court

was still required to examine challenged ordinances for con

stitutional invalidity under the First Amendment and to issue

a declaratory judgment even when state prosecutions are pending.

LeFlore v. Robinson, slip op. pp. 11-14. This holding was

fully consistent with a long line of authority in this Circuit,

see, e.g. Davis v. Francois, 395 F.2d 730, 737, n.l3 (5th

Cir. 1958); Ware v. Nichols, 266 F. Supp. 564 (N.D. Miss. 1967);

Guyot V. pierce, 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967).

The holding of this Court in both LeFlore and Davis

V. Francois were compelled by the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in Zwickler v. Ko ot a, 389 U.S. 241 (1967) and

- 12 -

— eron v. Johnson, 390 u.S. 611 (1968). In both cases, the

Supreme Court made it clear that the question of granting a

declaratory judgment was to be considered before and wholly

independently of whether an injunction should or could be

issued. indeed, in Cam e r o n , the Court itself first decided

the declaratory judgment question and then declined to rule

on whether 28 U.S.C. § 2283 was applicable because of its

decision on the first issue. Surely if 2283 barred any deci

sion on the request for declaratory relief, as the court below

held in the present case, the Supreme Court w u l d have so ruled

and would not have decided the question of whether the statute

involved in Cameron was constitutional.

The same result should apply to the question of

declaratory judgment as to the constitutionality of the court

order banning all marches and demonstrations on the courthouse

square or surrounding streets in Sandersville. The crucial

fact IS that the order has the operative effect of a city

ordinance. it was not issued as part of a pending action,

against parties thereto, with those parties attempting to have

it overturned in federal court. it was issued not only ex p a r t e ,

ut outside of any judicial proceeding whatsoever. The sheriff

vas instructed to enforce it in the same way he would an ordin

ance, and he did so, making arrests pursuant to it.

Thus, £ ameron and LeFlore require reversal of the

decision below. m addition, however, there is an independent

-13-

reason wh y the court below erred in not reaching the merits of

the challenge to the constitutionality of the ordinances and

court order here involved. The Complaint and proof herein

clearly established a continuing controversy over their validity.

Not only had the plaintiffs and members of their class demon

strated in the past and had been arrested, but they desired to

continue their activities in the future (A. 14-15). However,

the past and threatened future enforcement of the ordinances

and court order had and would have the effect of discouraging

their activities (A. 14-15). Protection was sought

against not only the pending prosecutions, but against future

arrests for failures to comply with the challenged ordinances

and order.

Thus, the plaintiffs clearly alleged, and proved, a

continuting controversy with city officials that could only

be resolved by a decision by the federal court as to whether

the curfew ordinance and court order banning demonstrations

were constitutional and had to be complied with. The resolu

tion of this controversy would in no way involve or require

the enjoining of any pending state prosecutions and hence

28 U.S.C. § 2283 was simply inapplicable to that aspect of the

case.

-14-

II.

THE SANDERSVILLE CURFEW ORDINANCES AND

THE COURT ORDER LIMITING DEMONSTRATIONS

ARE OVERBROAD REGULATIONS OF FIRST AMENDMENT

RIGHTS

Since, under LeFlore, the court below clearly erred

in not deciding the constitutionality of the Sandersville

loitering and curfew ordinances and the court order banning

marches in the vicinity of the courthouse, this Court could

simply remand the case for an initial determination by that

court of the issues. However, plaintiffs-appellants urge that

the

it would be appropriate for this Court to decide/constitutional

issues at this time.

A. The Loitering and Curfew Ordinances, in Flatly

Prohibiting All Demonstrations Regardless Of Circum

stances, Unduly Restrict The Exercise of First Amendment

Rights

In their complaint, plaintiffs-appellants attacked laws

as overbroadly interfering with the First Amendment rights of

free assembly, free speech, and petition. Two separate ordin

ances are involved; they are set out in full supra, pp.

and will be summarized here. Section 277 of the Sandersville

City Code states that it shall be unlawful for any persons to

"lounge or loiter" after 9.00 p.m. on any street or other public

place. Specifically excepted are persons "returning home from

any legitimate business or occupation or other like cases."

-15-

A s a result of the demonstrations and other occurrences out

lined above in the statement of facts, on December 27, 1969,

the Mayor declared a curfev? from 11.00 p.m. to 5.00 a.m.

This curfew was ratified at a meeting of the Mayor and Council

and other officials on December 31.

on February 11, 1970, the curfew was formalized by

passage of a new ordinance. It provided that during the hours

of 11.00 p.m. and 5.00 a.m. it would be unlawful for any persons

to "lounge, loiter, congregate, assemble, walk, march, parade,

or be present "in any public places". Again, an exception was

made for persons returning home from work, going to work, or

transacting business. The ordinance specifically states that

it does not invalidate the existing loitering ordinance, sec

tion 277.

It was under these enactments that persons were

arrested on February 6, 1970, in the vicinity of the county

jail. A group of about 100 persons had gone there during

the evening to register their protest against arrests of two

il/

groups of demonstrators earlier that same day. They had

resolved to remain at the jail until those arrested were

released; at least one person had gone there to find out the

whereabouts of her children. Shortly after 11.00 p.m., a

state patrolman advised the group of the time and of the curfew

*/ One group was arrested for violating the court order

“ discussed infra. The second was arrested for tres

passing on the driveway of a bank during a demonstra

tion at the adjoining Board of Education building.

-16-

and told them to disperse and go home. When the group did not

do so, its members were arrested and charged with violating

section 277 of the city code, the 9.00 p.m. loitering ordinance.

Appellants urge that the loitering and curfew ordin

ances, on their face and as applied, are unconstitutionally over

broad under a consistent line of authority. Recently, the

Supreme Court of the United States reaffirmed cox v. New Hampshire

312 U.S. 569 (1941), upholding state power to specify the time,

place and manner" of a parade "in order to accommodate competing

demands for public use of the streets." Shuttlesworth y.

Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147, 155-56 (1969). The Court stated the

constitutional test in the following terms (394 U.S. at 155):

rp'j-jg inquiry in every case must be that stated b y

Chief Justice Hughes in Cox v. New Hampshire, 312

U.S. 569 — whether control of the use of the streets

f o r a parade or procession was, in fact, "exerted so

as not to deny or unwarrantedly abridge the right of

assembly and the opportunities for the communication

of thought and the discussion of public questions

immemorially associated with resort to public places.

Id. at 574

Neither of the Sandersville ordinances can be sustained as an

attempt "to accommodate competing demands for public use of the

streets" (Shuttlesworth, supra, 394 U.S. at 155-56). They

utterly fail to accommodate the pressing need for black citizens

to participate in marches in the evening as a means of accom

plishing social and economic reform, or indeed for them even to

be able to go to and from evening meetings to discuss such

issues (see A. 13). People leaving work about 5.00 p.m must

-17-

usually go home, eat supper and attend to their children,

before they can go to such meetings and participate in a

demonstration.

Section 277 clearly does not attempt to accommodate

these needs. Indeed, it does not attempt to accommodate the

need of any group to have meetings or demonstrations after

9.00 p.m. It is not based upon a finding of any peculiar

traffic hazard after that time. Instead, it is a flat pro

hibition, leaving appellants and this Court in the dark as to

its rationale.

Both Section 277 and the February 11, 1970, ordin

ance, in fact, place persons going to and from night meetings'

and taking part in night demonstrations in a kind of "second-

class citizen" status. They both recognize and allow for

people to be on the streets at all hours of the night for

certain purposes, namely, going to and from work or carrying

out business. Presumably, this could include substantial

numbers of persons, e .g ., workers leaving a factory after an

evening shift. Section 277 by its enforcement and the curfew

ordinance by its explicit language, however, single out persons

engaged in otherwise peaceful, non-violent, and legal First

Amendment activities and makes them criminals. Surely, the

preferred freedoms protected b y the Constitution can not be

relegated to such a position.

Perhaps the case in this circuit closest in point is

Davis V. Francois, 395 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1968). There, this

-18-

Court invalidated a city ordinance which limited the number of

pickets at any facility within the city. (See also, LeFlore v.

Robinson, si. op. p. 15). The city attempted to bring the

ordinance within the purview of Cox v. New Hampshire, supra,

by contending that it was a regulation of "manner" within the

meaning of C o x 's sanction of regulations as to "time, place and

manner." The Court rejected this contention, invalidating the

ordinance "because it does not aim specifically at a serious

encroachment on a state interest or evince any attempt to

balance the individual's right to effective communication and

the state's interest in peace and harmony" (395 F.2d at 735).

The Court continued (395 F.2d at 736):

We emphasize again that our holding does not mean

the city is powerless to regulate demonstrations. It

must simply identify a substantial interest worthy of

protection. Note, Regulation of Demonstrations, 80

Harv. L. Rev. 1773 (1967). The decisions indicate

that this process has been accomplished in at least

two ways. First, the state b y a narrowly drawn statute

may regulate the time, place and manner of the demon

strations. Unless the building is a sensitive facility

that may be made totally off limits to public debate,

the right to demonstrate on public property should only

be regulated b y statutes that consider all of the

nuances of the time, place and manner. Second, it is

clear that the state may enact an ordinance that carves

out of the demonstration the evil it seeks to prohibit

and thereby isolates conduct that does not have First

Amendment protection

Some district courts in this Circuit, having considered

"all of the nuances of the time, place and manner" of a

particular situation have explicitly sanctioned night

-19-

V ’HI/

marches; while one has prohibited them.

The Fourth Circuit, however, has recently upheld an

ordinance of Charleston, South Carolina banning peaceful demon

strations after 8.00 p.m. Abernathy v. Conroy, 429 F.2d 1170

(4th Cir. 1970). We urge first, that the Fourth Circuit s

holding not be followed. The better position, and one con

sistent with the approach of this Court in D a ^ ^ and LeFlo .̂ ,

is that flat prohibitions on First Amendment activities, re

gardless of the circumstances prevailing in the particular

instance are unconstitutional. Rather, legitimate interests

of the city in preserving order can be served by more narrowly

drawn regulations that address themselves to the specific pro

blem of concern. For example, the city might prohibit noisy

demonstrations in residential areas after a particular time,

but could not flatly outlaw the kind of vigil outside of a

public building that was involved here in the arrests of February 6.

Moreover, the ordinance in Abernathy dealt with parades

as such. It did not, apparently, have the effect of making

criminal the going to and from meetings held indoors. Ihis is

precisely what section 277 of the Sandersville city code does.

*/ see Young v. D a v i s , 9 Race Rel.L.Rev. 590 (M.D Fla., June

9 1964) in which the district court restrained city and

state officials from "prohibiting Andrew Young and other

Negroes or persons associated with them from

orderly demonstrations by marching in and about the City

of St. Augustine, Florida and ^^s public streets, side-

walks and parks, at any hour in the night time . ( ^ . at 597).

see also Pnbinson v. Coopwood, 292 F. Supp.9 2 6 (N.D.Miss.1968)

**/ See Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F .Supp.4 9 2 (M.D.Ala.1966).

- 20 -

however, and as long as it stands the black citizens of the

city can not help but be deterred from engaging in activities

clearly protected b y the First Amendment.

R. The Court nrder Banning All Marches in the ̂

vicinity of the Courthouse is Similarly Overbro_^

Again, Davis v. Francois and LeFlore v.— Robinson

stand squarely for the proposition that flat bans on peaceful

marches or demonstrations fall afoul of the First Amendment,

in the present case, a state court judge issued a directive

that no marches, regardless of their character or the circum

stances surrounding them, could be held on the courthouse

square "or in the streets and subdivision" surrounding it

during the time the court was in session.

The incident on February 6, resulting in arrests for

violating the order vividly demonstrates its overbreadth. The

group was small, consisting of forty-three persons. Its mem

bers were quiet; they did not sing, clap, yell, or apparently

make any noise. They were on their way to the Board of Educa

tion, the focus of their protest, by the most direct and most

public route. Nevertheless, they were halted arrested, jaxled

for up to five days, and eventually sentenced to $100.00 or

15 days.

in the language quoted above from Davis, this court

states that the right to demonstrate on public places can be

regulated only by narrowly drawn statutes that "consider all

of the nuances of the time, place and manner" (395 F.2d at 736)

- 21 -

The court there recognized that some buildings may be so sen

sitive that they may be made totally off limits to public

debate. Appellants do not question that a courthouse itself

may be so designated. Nor do they question that a narrowly

drawn regulation, whether statute, ordinance, or court order,

could prohibit unruly and noisy crowds in the near vicinity of

a courthouse while a court was in session that would make it

impossible for a court to function. The order involved here,

however, is not so narrowly drawn and does not address itself

to these legitimate state interests. Rather, its overbreadth

sweeps within its ambit orderly, peaceful, marches along

a public street whether or not they in fact could possibly inter

fere with a court. Thus, it also should be held unconstitu

tional for overbreadth.

III.

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN NOT ENJOINING THE

USE OF VIOLENCE BY LAW OFFICERS AGAINST

ARRESTED DEMONSTRATORS

In yet another respect this case is related

to LeFlore. In both, the issue of mistreatment of demon

strators after arrest and during incarceration was raised

(see LeFlore, si. op. p.41). In both, of course, the main

focus of the action was on the constitutionality, facially

and applied, or ordinances used against demonstrators.

- 22 -

Hov/Gver, violGncG by law enfojrcGiri0nt officers aft0r arr0sts,

w h 0 th0 r such arrests be constitutionally valid or not, can

have a powerful deterrent effect on the free exercise of First

Amendment rights.

In the present case, testimony, more fully described

in the statement of facts above, was given concerning various

acts of police officers that was clearly illegal. This in

cluded the spraying of Mace and tear gas into cells filled

with prisoners, the apparent destruction of pictures taken by

one of the demonstrations, and the assault of a young demon

strator. The district court, however, made no findings of

fact concerning these claims and issued no injunctive relief

against police violence.

jjo reasons were given for the court's failure to

deal with this issue, although it can be assumed that it believed

that since it could not interfere with pending criminal prose

cutions, it also should do nothing regarding these other claims.

We believe that this was plainly error. Ever since

Kelly V. page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) this Court has made

it clear that federal district courts have a responsibility to

protect persons against all forms of interference with

the exercise of First Amendment rights. This includes protection

*/ And indeed, in HaQue v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496(1938)

~ the Supreme Court also so held.

-23-

against unwarranted violence by law-enforcement officers,

see, Williams v. Wa ll ac e, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala. 1965).

Thus the order of the court below should be reversed

and remanded with instructions to make findings concerning the

alleged mistreatment of demonstrators and to issue appropriate

xnjunctive relief if necessary.

IV.

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN GRANTING

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AGAINST PLAINTIFFS.

AS noted in the statement of the case, the defendants-

appellees cross-complained against the plaintiffs and asked for

an injunction against certain alleged practices. Considerable

testimony was introduced concerning alleged threats against

black people who frequented stores against which a boycott was

urged. There was also testimony concerning alleged acts of

arson, threatening telephone calls, etc.

The district court made findings of fact concerning

these matters (A. 835-837). Although it denied any injunctive

relief on behalf of plaintiffs, the court did issue an injunc

tion against them, enjoining them from directly or indirectly

attempting to "injure, oppress, threaten, intimidate, coerce

or otherwise prevent" persons from shopping in stores and parti

cularly from taking pictures or pointing cameras at people near

or about stores.

-24-

plaintiffs-Appellants urge that granting this in

junction v/as error, particularly in the context of the court

having failed to address itself to the evidence presented b y them

concerning acts of violence and intimidation visited on them in

their exercise of First Amendment activities. Again, in this

respect, the court below failed to conform to the rule established

in Kelly v. Page, supra.

jn Kelly, this Court held that a district court, when

faced with a demonstration situation, must address itself to the

total picture. It is not enough simply to enjoin demonstrators

from committing acts that go beyond the pale of First Amendment

protections. Rather, it must deal with all aspects of the

situation and clarify for all concerned the duties, rights, and

responsibilities of police officials as well.

To do otherwise has the inevitable effect of stifling

and chilling the exercise of First Amendment rights. Here,

the plaintiffs made serious allegations and presented evidence

concerning police abuses. They also testified as to violence

and intimidation inflicted on them. They appealed to the

federal court for protection and for definition of their rights.

But, the court said nothing about their allegations and refused

to issue any guidelines to govern police conduct or to give them

protection. Instead, it made findings as to alleged wrongful

acts they had committed and issued an injunction against them

along. The message to them seems clear; the court will not

-25-

protect you against wrongful acts of the police when you are

arrested as the result of a demonstration, but if you do anything

wrong the court will add its weight to that of the police to

keep you in line. With this array of force against them, wi th

out any counterbalancing attempt to give protection or even

decide whether protection is needed, individuals can hardly

help but feel intimidated and deterred from exercising any of

their constitutional rights for fear of the consequences.

Further, in the context of a balanced order spelling

out what the police as well as the demonstrators may do, the

injunction issued might be proper. But standing alone its

language is too broad. It enjoins ^ attempts, direct or in

direct, to prevent people from shopping in any store in Washing

ton county. This could be interpreted by many as possibly in

cluding speaking with people, or picketing, in order to convince

them to join in the boycott. With the threat of being held in

contempt of court ever present, many persons could decide not

to take the risk that an attempt to persuade equalled an attempt

to prevent.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the court

below should be reversed and the case remanded with instructions

to (1) enter a declaratory judgment that the Sandersville loitering

- 26 -

and curfew ordinances and the court order prohibiting inarches

are unconstitutional; (2) make findings of fact concerning

the allegations of police misconduct; and (3) enter appropriate

injunctive relief pursuant to the standards of Kelly v. Page.

Respectfully submitted

/ '

-

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

JOHN H. RUFFIN, Jr.

930 Gwinnett St.

Augusta, Ga. 30903

Attorneys For Plaintiffs-Appellants

-27-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the

attached Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants and the Appellants'

Appendix on counsel for Appellees-Defendants by mailing the

same air-mail, postage prepaid to :

Mr. Denmark Groover, Jr,

Attorney At Law

P .O . Box 755

Macon, Ga. 31202

Mr. T.A. Hutcheson

Attorney At Law

P.O. Box 621

Sandersville, Ga. 31082

Mr. D.E. McMaster

Attorney At Law

P.O. Box 348

Sandersville, Ga. 31082

Hon. Ervin L. Evans

109 W Church Street

Sandersville, Ga. 31082

Done this day of November, 1970

/ V //

3 )

Attorney for Appellants-Plaintiffs.

-28-