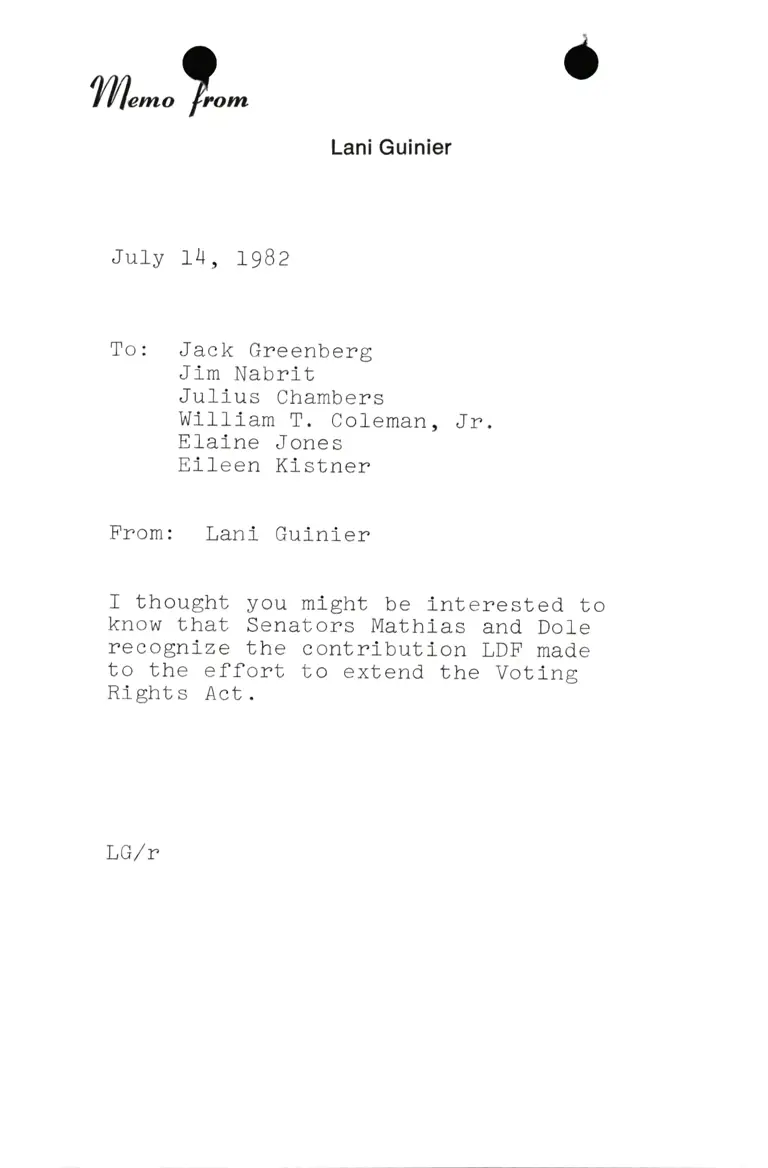

Memo from Lani Guinier to Greenberg, Nabrit, and others

Correspondence

July 14, 1982

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Memo from Lani Guinier to Greenberg, Nabrit, and others, 1982. b34e42f9-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3145fb40-808a-410c-ab37-b7904d041374/memo-from-lani-guinier-to-greenberg-nabrit-and-others. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

[iln*o?,^

Lani Guinier

July 14, tg\z

To: Jack Greenberg

Jim Nabrit

Juli-us Chambers

Wl1llam T. Coleman, Jr.

Elalne Jones

Eileen Klstner

From: Lani Guinier

I thought you might be lnterested to

know that Senators Mathias and Dol_e

recognlze the contrlbution LDF made

to the effort to extend the Voting

Rights Act.

LG/r