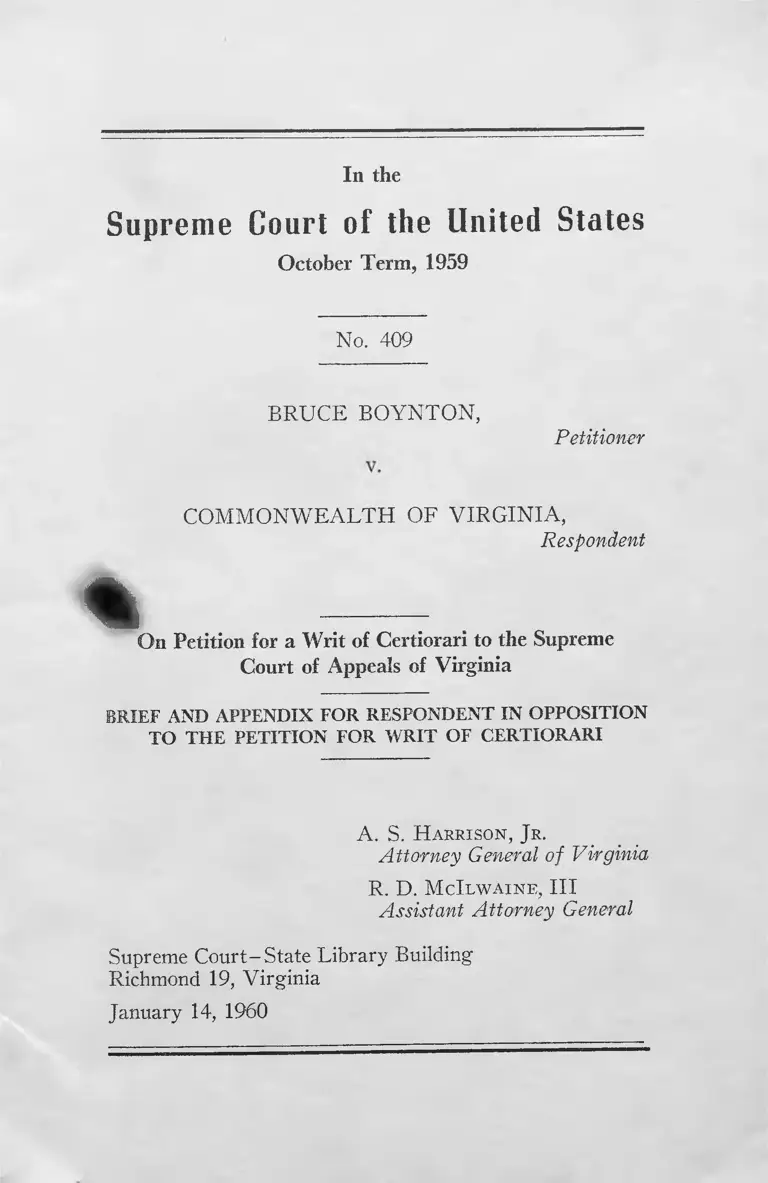

Boynton v. Virginia Brief and Appendix for Respondent in Opposition to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 14, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Virginia Brief and Appendix for Respondent in Opposition to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1960. e4529b9c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/316ce001-5af9-4c26-8a84-9ca8f5ab04d2/boynton-v-virginia-brief-and-appendix-for-respondent-in-opposition-to-the-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1959

No. 409

BRUCE BOYNTON,

Petitioner

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent

%

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

TO THE PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

A. S. H a rriso n , J r .

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , III

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

January 14, 1960

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preliminary Statement..... ......................... 1

P rior Proceedings......................................................................... 2

Statement of Facts...................... 2

T he Statute .................................................................................... 3

Questions Presented.................. 4

Argument ...................................................... 4

Intercorporate Relationship ................................ 4

T he Virginia Statute and the I nterstate Commerce Clause 5

T he V irginia Statute and the Fourteenth A mendment..... 9

Conclusion ........................................ 10

A ppen d ix

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bell v. Hagmann, 200 Va. 626, 107 S. E. (2d) 426...................... 5

Commonwealth v. Castner, 138 Va. 81, 121 S. E. 894......... ............ 5

Henderson v. United States, 336 U. S. 816..................................... 6

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 380 .................................. .......... 6

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis—San Francisco Railway Co., 297 I. C. C.

335 ............................................................................................. 6, 7

Sisk v. Town of Shenandoah, 200 Va. 277, 279, 105 S. E. (2d)

169.................................................................................................. 5

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 4 Cir., 268 F. (2d)

845 8

Other Authorities

Page

Acts of Assembly of 1934, Chapter 165............................................ 5

Code of Virginia (1950) :

Section 8-264 ..................... ........................................................... 5

Section 8-266 ......................................................... .............. ....... 5

Section 18-225 .............. ........................ ......... 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10

Constitution of the United States :

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 .......................................... ....... . 4

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C. A., Sections 1 et seq........... 6

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1959

No. 409

BRUCE BOYNTON,

v.

Petitioner

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION TO THE

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In a letter to the Attorney General of Virginia from the

Honorable James R. Browning, Clerk of the Supreme Court

of the United States, dated December 12, 1959, the Com

monwealth of Virginia was requested to respond to the peti

tion for writ of certiorari filed in the instant case and to

“deal with the intercorporate relationship between the Trail-

ways Bus Company and the Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc.,

set forth in any documents of which the Virginia courts can

take judicial notice”. Respondent was also requested to set

forth her “view of the controlling Virginia law under which,

2

it is claimed, petitioner was convicted for trespass”.* In

accordance with the request contained in the above men

tioned communication, written by the Clerk at the direction

of this Court, the within brief of the respondent in opposi

tion to the petition for writ of certiorari is filed.

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On January 6, 1959, petitioner was convicted in the Police

Court of the City of Richmond, Virginia, for violation of

Section 18-225 of the Code of Virginia (1950) as amended.

He was sentenced to pay a fine of $10.00 and costs. Upon

appeal to the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond, peti

tioner was again convicted and a similar sentence was im

posed on February 20, 1959. A petition for writ of error

to the judgment of the Hustings Court was denied by the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia on June 19, 1959,

and the cause is currently before this Court upon petition

for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia, filed in the Supreme Court of the United States

by the petitioner on September 15, 1959.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

On the night of December 20, 1958, the petitioner, a

Negro student at the Howard University School of Law,

was traveling via “Trailways” bus from Washington, D. C.,

to his home in Selma, Alabama. He boarded the bus in

Washington, D. C., at 8 :00 P. M., and arrived in Richmond,

Virginia, about 10:40 P. M. Upon being informed by the

driver of the bus that there would be a stopover of some

forty minutes in Richmond, petitioner left the bus and

entered the bus terminal building located at Ninth and Broad

Streets in the City of Richmond (R. 31-33). Although

* Post, Appendix A.

3

noticing therein a separate restaurant for colored patrons

which had seating capacity available (R. 33-S$), petitioner

entered the restaurant for white patrons, seated himself at

a counter and requested service. He was advised—first by

a waitress and then by the assistant manager of the restau

rant—that separate facilities were maintained for persons

of the Negro race and that he could be served in the restau

rant reserved for colored patrons. Petitioner stated that he

was an interstate passenger and was entitled to be served

where he was. The assistant manager requested him to leave

the premises and repair to the other restaurant. When peti

tioner refused to comply with this request, he was arrested,

upon a warrant issued at the instance of the assistant man

ager, for trespass in violation of Section 18-225 of the

Virginia Code (R. 22, 29-30, 34-36).

The bus terminal building in Richmond, Virginia, is operated

by Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc., which company leases space

therein to Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc. The

lease in question grants Bus Terminal Restaurant of Rich

mond, Inc., exclusive authority to operate restaurant facili

ties in the terminal, and separate facilities for white and

colored patrons are maintained by the lessee company (R.

21). The Record discloses that Bus Terminal Restaurant of

Richmond, Inc., is “not affiliated in any way with the bus

company”, and that the bus company has “no control over

the operation of the restaurant” (R. 21). Moreover, thefi

restaurant facilities are “not necessarily” operated for bus

passengers and have “quite a bit of business . . . from local

people” (R. 26).

THE STATUTE

Under attack in the instant case is Section 18-225 of the

Code of Virginia (1950) as amended, which statute in per

tinent part provides:

4

“If any person shall without authority of law go upon

or remain upon the lands or premises of another, after

having been forbidden to do so by the owner, lessee,

custodian or other person lawfully in charge of such

land, or after having been forbidden to do so by sign

or signs posted on the premises at a place or places

where they may be reasonably seen, he shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished by a fine of not more than one hundred

dollars or by confinement in jail not exceeding thirty

days, or by both such fine and imprisonment.”

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code, as applied

to petitioner in the case at bar, contravene Article I, Section

8, Clause 3, of the Constitution of the United States ?

2. Does Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code, as applied

to the petitioner in the case at bar, contravene the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States?

ARGUMENT

Intercorporate Relationship

In response to this Court’s request that the Common

wealth “deal with the intercorporate relationship between

the Trailways Bus Company and the Trailways Bus Termi

nal, Inc., set forth in any documents of which the Virginia

courts can take judicial notice, respondent respectfully states

that such relationship is not reflected in any documents of

which the Virginia courts can take judicial notice. So far as

respondent is aware, the only official documents, if any,

which would contain evidence of the intercorporate relation

ship of corporations would be the records of the State Cor- y

poration Commission. Upon an examination of the Virginia

law, counsel for respondent do not find that the Virginia

courts can take judicial notice of such documents.

5

Under Virginia law, appellate courts will not even take

judicial notice of the existence or contents of legislative

charters of private corporations which were not relied upon

in the court below. Section 8-264, Code of Virginia (1950) ;

Commonwealth v. Costner, 138 Va. 81, 121 S. E. 894.

Moreover, Section 8-266 of the Virginia Code establishes

the procedure by means of which the existence and contents

of records and papers in the office of the State Corporation

Commission may be proved. In pertinent part, this statute

provides:

“A copy of any record or paper * * * (2) in the

office of the State Corporation Commission, the State

Board of Education, or the board of supervisors or

other governing body of any county, attested by the

secretary or clerk of such Commission or board; * * *

may be admitted as evidence in lieu of the original. * * *

“Any such copy purporting to be sealed, or sealed

and signed, or signed alone, by any such officer, secre

tary or clerk, may be admitted as evidence, without any

proof of the seal or signature, or of the official character

of the person whose name is signed to it.”

This provision of the Virginia Code prescribing the manner

of proving certain specified documents and referring specifi

cally to records and papers in the office of the State Corpora

tion Commission negatives the authority of the Virginia

courts to take judicial notice of such documents. See, Sisk

v. Town of Shenandoah, 200 Va. 277, 279, 105 S. E. (2d)

169; Bell v. Hagmami, 200 Va. 626, 107 S. E. (2d) 426.

THE VIRGINIA STATUTE AND THE

INTERSTATE COMMERCE CLAUSE

Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code first appeared as

Chapter 165 of the Acts of the General Assembly of 1934.

6

Acts of Assembly (1934), Chapter 165, p. 248. With minor

amendments not here material, the language of the existing

statute is substantially identical to that contained in the

original enactment. As is manifest from its terms, the

statute does no more than impose criminal sanctions for

continued trespass by an individual upon the lands or prem

ises of another after proper warning and is entirely devoid

of any racial connotation whatever.

Counsel for respondent respectfully submit that invoca

tion of this statute by an agent of Bus Terminal Restaurant

of Richmond, Inc., in the case at bar, presents no substan

tial question of conflict with the Commerce Clause of the

Constitution of the United States. As pointed out by this

Court in Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 380, “the Con

stitution puts the ultimate power to regulate commerce in

Congress”, and Congress has exercised the power thus con

ferred by enactment of the Interstate Commerce Act. 49

U. S. C. A. 1 et seq. Moreover, in light of the provisions

of Sections 3(1) and 316(d) of this Act*—■ which make it

unlawful for any common carrier to make or give any undue

or unreasonable preference or advantage to any person, or to

subject any particular person to any undue or unreasonable

prejudice or disadvantage in any respect—it is manifest that

Congress has acted in the field of racial discrimination in

interstate commerce and prohibited such discrimination to

the extent deemed by it to be permissible or desirable. See,

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816.

Equally manifest is it that the maintenance of racially

separate restaurant facilities in a terminal building by a lessee

non-carrier concern is not antagonistic to the provisions of

the Interstate Commerce Act. The validity of this proposi

tion was definitively established in N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis—

*49 U. S. C. A. 3 (1 ); 49 U. S. C. A. 316(d) ; Post, Appendix B.

7

San Francisco Railway Co., 297 I. C. C. 335, in which case

the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that the main

tenance of segregated lunch rooms, located in a railroad

passenger station in Richmond, Virginia, by a lessee of the

Richmond Terminal Railway Company was not violative of

Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act. Indeed, in that

case it was established—in contrast to the want of similar

proof in the case at bar—that the defendant corporation,

Richmond Terminal Railroad Company, which operated the

terminal and leased the lunch room facilities to the Union

News Company, was jointly controlled by the Richmond,

Fredericksburg and Potomac and the Atlantic Coast Line

railroad companies and was a carrier subject to the jurisdic

tion of the Commission.

The decision of the Interstate Commerce Commission in

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis— San Francisco Railway Co.,supra,

is clearly at variance with the instant petitioner’s, contention

that theloperation of separate restaurant facilities^ by Bus

TerminaLRestanrailt of Richmond,’ Inc., constitutes a bur

den upon interstate commerce, and it is significant that peti

tioner does not here contend that Section 18-225 of the

Virginia Code as applied to the circumstances of the case

at bar violates any provision of the Interstate Commerce

Act. Counsel for respondent submit that if, as shown above,

the operation of racially separate restaurant facilities by a

lessee non-carrier concern violates none of the comprehen

sive provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act or any of the

manifold regulations of the Interstate Commerce Commis

sion implementing and applying that Act, such action is not

antagonistic to the Commerce Clause per se.

Finally, counsel for respondent submit that none of the

decisions cited by petitioner is applicable to the situation

which obtains in the instant case. These decisions were also

8

relied upon in Williams v. Howard, Johnson’s Restaurant,

4 Cir., 268 F. (2d) 845, in which case the petitioner con

tended that his exclusion from the Howard Johnson’s Res

taurant in the City of Alexandria, Virginia, on racial

grounds amounted to discrimination against a person mov

ing in interstate commerce and also interference with the

free flow of commerce in violation of the Constitution of

the United States. With respect to these decisions, the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

declared (268 F. (2d) at 848) :

“The cases upon which the plaintiff relies in each

instance disclosed discriminatory action against persons

of the colored race by carriers engaged in the trans

portation of passengers in interstate commerce. In

some instances the carrier’s action was taken in accord

ance with its own regulations, which were declared

illegal as a violation of paragraph 1, section 3 of the

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U.S.C.A. Sec. 3(1),

which forbids a carrier to subject any person to undue

or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any re

spect, as in Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80, 61

S. Ct. 873, 85 L. Ed. 1201, and Henderson v. United

States, 339 U. S. 816, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. Ed. 1302.

In other instances, the carrier’s action was taken in

accordance with a state statute or state custom requir

ing the segregation of the races by public carriers and

was declared unlawful as creating an undue burden on

interstate commerce in violation of the commerce clause

of the Constitution, as in Morgan v. Com. of Virginia,

328 U. S. 373, 66 S. Ct. 1050, 90 L. Ed. 1317; Wil

liams v. Carolina Coach Co., D. C. Va., I l l F. Supp.

329, affirmed 4 Cir., 207 F. 2d 408; Flemming v. S. C.

Elec. & Gas Gx, 4 Cir., 224 F. 2d 752; and Chance v.

Lambeth, 4 Cir., 186 F. 2d 879.

“In every instance the conduct condemned zms that

of an organisation directly engaged in interstate com-

9

merce and the line of authority would be persuasive

in the determination of the present controversy if it

could be said that the defendant restaurant zvas so en

gaged. We think, however, that the cases cited are not

applicable because we do not find that a restaurant is

engaged in interstate commerce merely because in the

course of its business of furnishing accommodations

to the general public it serves persons who are travel

ing from state to state. As an instrument of local com

merce, the restaurant is not subject to the constitutional

and statutory provisions discussed above and, thus,

is at liberty to deal with such persons as it may select.”

(Italics supplied)

THE VIRGINIA STATUTE AND THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

Petitioner has devoted less than a page of his petition

for writ of certiorari to the contention that Section 18-225

of the Virginia Code, as applied to him in the instant case,

violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, and counsel for respondent submit that

little consideration need be accorded it here. All that we

could wish to say upon this question has already been stated

by Judge Soper, speaking for the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in Williams v. Howard

Johnson's Restaurant, supra. In that case, the petitioner—

in addition to asserting that his exclusion from the Howard

Johnson’s Restaurant in question on racial grounds contra

vened the Commerce Clause—also contended that such exclu

sion constituted a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Noting that the dismissal of petitioner’s complaint by the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia “was in accord with the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States, and other Federal courts”, Judge

Soper observed (268 F. (2d) at 847-848) :

10

“ [Petitioner] points, however, to statutes of the

state which require the segregation of the races in the

facilities furnished by carriers and by persons engaged

in the operation of places of public assemblage; he

emphasizes the long established local custom of ex

cluding Negroes from public restaurants and he con

tends that the acquiescence of the state in these prac

tices amounts to discriminatory state action which falls

within the condemnation of the Constitution. The

essence of the argument is that the state licenses

restaurants to serve the public and thereby is burdened

with the positive duty to prohibit unjust discrimination

in the use and enjoyment of the facilities.

“This argument fails to observe the important dis

tinction between activities that are required by the

state and those which are carried out by voluntary

choice and without compulsion by the people of the

state in accordance with their own desires and social

practices. Unless these actions are performed in obedi

ence to some positive provision of state law they do

not furnish a basis for the pending "complaint. The

license laws of Virginia do not fill the void. Section

35-26 of the Code of Virginia, 1950, makes it unlawful

for any person to operate a restaurant in the state with

out an unrevoked permit from the Commissioner, who

is the chief executive officer of the State Board of

Health. The statute is obviously designed to protect

the health of the community but it does not authorize

state officials to control the management of the busi

ness or to dictate what persons shall be served. The

customs of the people of a state do not constitute state

action within the prohibition of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.” (Italics supplied)

CONCLUSION

In light of the foregoing, counsel for respondent respect

fully submit that Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code, as

applied to the petitioner in the case at bar, presents no serious

11

question of conflict with the Commerce Clause of the Con

stitution of the United States or the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

Respectfully submitted,

A. S. H a rriso n , J r .

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , IIT

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

January 14, 1960

12

A P P E N D I X A

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

W a s h in g t o n 25, D. C.

December 12, 1959

Honorable A. S. Harrison, Jr.

Attorney General of Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Re: Boynton v. Virginia

No. 409, October Term, 1959

Dear S ir:

On instructions from this Court, I am writing to ask if

the Commonwealth of Virginia will be good enough to

respond to the petition in the above case and, included in its

response, deal with the intercorporate relationship between

the Trailways Bus Company and the Trailways Bus Termi

nal, Inc., set forth in any documents of which the Virginia

courts can take judicial notice. Compare Henderson v.

United States, 339 U. S. 816.

It is further requested that you set forth your view of the

controlling Virginia law under which, it is claimed, petitioner

was convicted for trespass.

Very truly yours,

James R. Browning, Clerk

By (s) R. J. Blanchard

R. J. Blanchard

Deputy

RJB :vmg

13

A P P E N D I X B

49 U. S. C. A. 3(1)

It shall be unlawful for any common carrier subject to

the provisions of this chapter to make, give, or cause any

undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any par

ticular person, company, firm, corporation, association, local

ity, port, port district, gateway, transit point, region, district,

territory, or any particular description of traffic, in any

respect whatsoever; or to subject any particular person, com

pany, firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port dis

trict, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory, or

any particular description of traffic to any undue or unrea

sonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever :

Provided, however, That this paragraph shall not be con

strued to apply to discrimination, prejudice, or disadvantage

to the traffic of any other carrier of whatever description.

49 U. S. C. A. 316(d)

All charges made for any service rendered or to be ren

dered by any common carrier by motor vehicle engaged in

interstate or foreign commerce in the transportation of

passengers or property as aforesaid or in connection there

with shall be just and reasonable, and every unjust and un

reasonable charge for such service or any part thereof, is

prohibited and declared to be unlawful. It shall be unlawful

for any common carrier by motor vehicle engaged in inter

state or foreign commerce to make, give, or cause any undue

or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular

person, port, gateway, locality, region, district, territory,

or description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or to

subject any particular person, port, gateway, locality, region,

district, territory, or description of traffic to any unjust

discrimination or any undue or unreasonable prejudice or

14

disadvantage in any respect whatsoever: Provided, how

ever, That this subsection shall not be construed to apply to

discriminations, prejudice, or disadvantage to the traffic of

any other carrier of whatever description.

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N I A

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No, 7

BRUCE BOYNTON,

v.

Petitioner

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE COMMONWEALTH

OF VIRGINIA

A. S. H a rr iso n , J r .

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , I I I

Assistant Attorney General

W alter E. R ogers

Special Assistant

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Prior P roceedings............................................................................ 1

Statement of Facts....................... 2

T he Statute..................... 4

Questions Presented.............................. 5

Argument ......... 5

I. The Virginia Statute and the Interstate Commerce Clause 5

II. The Virginia Statute and the Fourteenth Amendment....... 19

Conclusion ....................................................... 31

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

A. F. L. v. American Sash & Door Co., 335 U. S. 538 ......... ......... 16

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ..................................... - ........... 30

Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U. S. 520........................... 13, 15

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 ..........................-................... 31

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ............ ......................... 19, 20, 25, 28

Hall v. Virginia, 188 Va. 72 ............................................................... 31

Huron Cement Co. v. City of Detroit,.....U. S........., 80 S. Ct. 813,

decided April 25, 1960........................ ......... -.............................. 16

Keys v. Carolina Coach Co., 64 M. C. C. 769 ................................... 6

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 .....................—-........................... 31

McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. Ry., 235 U. S. 151......................... 24

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 8 0 ...................................... ..... 24

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 .................................... 12, 13, 15

Page

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis, San Francisco Railway Co., 297 I. C. C.

335 .............................................. ............................. ................. 6, 8

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ........................................... .... 19!, 30

Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, 181 F. Supp. 124............. 23

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761 ................... 9, 13, 15

State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295 ....... ................... 20

United States v. Cruickshank, 92 U. S. 542 ......... .......................... . 19

United States v. Flarris, 106 U. S. 629 ..................................... 19, 20

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 4 Cir., 268 F. (2d)

845 .... ................ .................................................................... 16, 24

Wilmington Parking Authority v. Burton, 157 A. 2d 894 ............. 23

Other Authorities

Acts of Assembly (1934), Chapter 165, p. 248 ............................... 5

Code of Virginia (1950), Section 18-225 .................................... 4, 5

Interstate Commerce Act, Section 303(a) (19) ................... ......... . 7

49 U.S.C.A. 3(1) ................................................................ ........ . 6

49 U.S.C.A. 316(d) .......................................................................... 6

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No. 7

BRUCE BOYNTON,

v.

Petitioner

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Respondent

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE COMMONWEALTH

OF VIRGINIA

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On January 6, 1959, petitioner was convicted in the Police

Court of the City of Richmond, Virginia, for violation of

Section 18-225 of the Code of Virginia (1950) as amended,

and a fine of ten dollars and costs was imposed. Upon appeal

to the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond, petitioner

was again convicted on February 20, 1959, and the same

punishment imposed. A petition for a writ of error to the

judgment of the Hustings Court was denied by the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia on June 19, 1959, and the

cause is currently before this Court on a writ of certiorari

to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, which was

granted by this Court on February 23, 1960.

2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

On the night of December 20, 1958, the petitioner, a

Negro student at the Howard University School of Law,

was traveling via “Trailways” bus from Washington, D.

C., to his home in Selma, Alabama. He boarded the bus in

Washington, D. C., at 8:00 P. M., and arrived in Richmond,

Virginia, about 10:40 P. M. Upon being informed by the

driver of the bus that there would be a stopover of some

forty minutes in Richmond, petitioner left the bus and

entered the bus terminal building located at Ninth and

Broad Streets in the City of Richmond (R. 27-28). Al

though noticing therein a separate restaurant for colored

patrons which had seating capacity available (R. 28, 22),

petitioner entered the restaurant for white patrons, seated

himself at a counter and requested service. He was advised

—first by a waitress and then by the assistant manager of

the restaurant—that separate facilities were maintained for

persons of the Negro race and that he could be served in

the restaurant reserved for colored patrons. Petitioner

stated that he was an interstate passenger and was entitled

to be served where he was. The assistant manager requested

him to leave the premises and repair to the other restaurant.

When petitioner refused to comply with this request, he was

arrested, upon a warrant issued at the instance of the

assistant manager, for trespass in violation of Section 18-

225 of the Virginia Code (R. 20, 21, 30).

The bus terminal building in Richmond, Virginia, is

owned by Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc., which company

leases space therein to Bus Terminal Restaurant of Rich

mond, Inc. The lease in question grants Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., exclusive authority to operate

restaurant facilities in the terminal (R. 9-18), and separate

facilities for white and colored patrons are maintained by

3

the lessee company (R. 20). The Record discloses that Bus

Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., is “not affiliated

in any way with the bus company”, and that the bus com

pany has “no control over the operation of the restaurant”

(R. 20). Moreover, the restaurant facilities are “not nec

essarily” operated for bus passengers and have “quite a bit

of business . . . from local people” (R. 23).

Counsel for the Commonwealth find it necessary to com

ment upon the statement contained in the petitioner’s brief

and that contained in the brief amicus curiae filed by the

Solicitor General on behalf of the United States. In the

former, it is stated that petitioner first looked into a small

restaurant and noticed “that it was crowded” (Brief, p. 3).

In the brief of the Solicitor General, it is stated that the

restaurant reserved for colored people “appeared to be

crowded” (Brief, p. 2). While the petitioner testified that

the restaurant reserved for colored patrons “appeared to be

crowded” and that he informed the witness that it was “a

bit” crowded, the witness Rush, assistant manager of the

restaurant, testified that the facility in question was not

crowded (R. 22). Neither the petitioner’s brief nor that of

the Solicitor General contains any reference to this positive

testimony which, in the present posture of this litigation,

must be accepted as establishing the fact of the case.

If the condition—whether crowded or uncrowded—of the

restaurant reserved for colored people is immaterial, ref

erence to such condition is unnecessary. If material, this

Court should not be given the impression that the facts were

favorable to the petitioner’s view of the case in an attempt

to show an alleged inconvenience to an interstate traveler

which did not exist. On the contrary, an examination of his

evidence establishes that the petitioner’s complaint is not

that he was denied an opportunity to secure food or was

4

inconvenienced in so doing, but that he was denied the

opportunity to eat in a racially non-segregated facility in

violation of his alleged constitutional right as an interstate

traveler.

Moreover, while counsel for the petitioner and the Solici

tor General have gone to great lengths to present to this

Court evidence concerning the inter-corporate relationship

between certain operating bus companies and Trailways Bus

Terminal, Inc.-—evidence which was not presented to nor

considered by any judicial tribunal of the Commonwealth

of Virginia—both have failed to mention, either in their

factual statement or elsewhere in their briefs, evidence

which is properly in the record (1) that there was no affili

ation in any way between the bus company and the restau

rant company here involved and (2) that the bus company

had no control over the operation of the restaurant, which

is maintained for local clientele as well as persons who may

be passengers on buses using the terminal in which the

restaurant facilities are located.

THE STATUTE

Under attack in the instant case is Section 18-225 of the

Code of Virginia (1950) as amended, which in pertinent

part provides:

“If any person shall without authority of law go

upon or remain upon the lands or premises of another,

after having been forbidden to do so by the owner,

lessee, custodian or other person lawfully in charge of

such land, or after having been forbidden to do so by

sign or signs posted on the premises at a place or places

where they may be reasonably seen, he shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished by a fine of not more than one hun

dred dollars or by confinement in jail not exceeding

thirty days, or by both such fine and imprisonment.”

5

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code, as applied

to petitioner in the case at bar, contravene Article I, Section

8, Clause 3, of the Constitution of the United States?

2. Does Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code, as applied

to the petitioner in the case at bar, contravene the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States ?

ARGUMENT

I.

The Virginia Statute and the Interstate Commerce Clause

Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code first appeared as

Chapter 165 of the Acts of the General Assembly of 1934.

Acts of Assembly (1934), Chapter 165, p. 248. With minor

amendments not here material, the language of the existing

statute is substantially identical to that contained in the

original enactment. As is manifest from its terms, the stat

ute does no more than impose criminal sanctions for con

tinued trespass by an individual upon the lands or premises

of another after proper warning and is entirely devoid of

any racial connotation whatever. The statute does not pur

port to be, and is not, a racial segregation law.* It forbids

trespass by anyone—whether he be a member of a racial

minority or not—in going upon or remaining upon the pri

vate property of another when he is not welcome. Such con-

* Indeed, those familiar with the legislative history of the statute

are aware that the provision concerning signs was inserted to combat

the problems presented by unauthorized use of unattended, private

parking lots. In this connection, petitioner’s discussion of the early

statutes and common law of Virginia relating to trespass upon private

property, and his compilation of the statutes of other States, England,

the Commonwealth countries and South Africa (to show where the

petitioner would and would not have been convicted of an offense under

the circumstances of this case) are of no assistance in resolving the

issues presented in the instant litigation.

6

duct in violation of individual property rights is a proper

subject of State legislation.

Counsel for the Commonwealth respectfully submit that

invocation of this statute by an agent of Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., in the case at bar, entails no

conflict with the Interstate Commerce Act or the Commerce

Clause of the United States Constitution. With respect to

the Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C. A. 1 et seq., the

provisions of Sections 3(1) and 316(d) thereof make it

unlawful for any common carrier by railroad or motor

vehicle to make or give any undue or unreasonable prefer

ence or advantage to any person, or to subject any particular

person to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvan

tage in any respect.* However, the maintenance of racially

separate restaurant facilities in a terminal building by a

lessee non-carrier concern is not antagonistic to these pro

visions of the Interstate Commerce Act. The validity of this

proposition was definitely established in N.A.A.C.P. v. St.

Louis— San Francisco Railway Co., 297 I. C. C. 335, in

which case the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that

the maintenance of segregated lunch rooms located in a rail

road passenger station in Richmond, Virginia, by a lessee

of the Richmond Terminal Railway Company was not vio

lative of Section 3(1) of the Act. Subsequently, in Keys v.

Carolina Coach Co., 64 M. C. C. 769, the Commission ruled

that Section 316(d) of the Interstate Commerce Act im

posed upon common carriers by motor vehicle restrictions

similar to those imposed by Section 3(1) upon railroad

carriers.

The decision of the Interstate Commerce Commission in

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis— San Francisco Railway Company,

*49 U.S.C.A. 3(1) ; 49 U.S.C.A. 316(d) ; post, Appendix A.

7

supra, is utterly at variance with the contention of the peti

tioner in the case at bar that the operation of racially sepa

rate restaurant facilities by Bus Terminal Restaurant of

Richmond, Inc., is repugnant to the Interstate Commerce

Act. Indeed, in that case it was established—in contrast to

the want of similar proof in the case at bar—that the de

fendant corporation, Richmond Terminal Railway Com

pany, which operated the terminal and leased the lunch room

facilities to the Union News Company, was jointly controlled

by the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac and the

Atlantic Coast Line railroad companies and was a carrier

subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission.

In an effort to avoid the conclusive effect of that decision,

counsel for the petitioner and the Solicitor General seek to

introduce new evidence in the instant case, at the ultimate

level of judicial review, to establish that Trailways Bus Ter

minal, Inc.—the company which owned the terminal build

ing in question and leased space therein to Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc.—is jointly owned by two

operating bus companies, Carolina Coach Company and

Virginia Stage Lines, whose names do not even appear in

the record. In this manner they seek to invoke the provisions

of Section 303(a) (19) of the Interstate Commerce Act,

which prescribes:

“The ‘services’ and ‘transportation’ to which this

chapter applies include all vehicles operated by, for, or

in the interest of any motor carrier irrespective of own

ership or of contract, express or implied, together with

all facilities and property operated or controlled by any

such carrier or carriers, and used in the transportation

of passengers or property in interstate or foreign com

merce or in the performance of any service in connec

tion therewith.”

8

The evidence offered by counsel for the petitioner is set

forth in documents of which the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia may not take judicial notice. The evidence of

the Solicitor General is offered to this Court, for the first

time in this case, by one who is not even a party to the

litigation. Counsel for the Commonwealth insist that such

evidence is not properly before this Court and may not prop

erly be considered by this Court.

Even if it were appropriate for this Court to consider it>

the challenged evidence would not establish that the restau

rant facilities under consideration in this case were “oper

ated or controlled” by a motor vehicle carrier. At most,

such evidence would only establish that the terminal itself

was so operated or controlled, and the record discloses that

there was no enforced racial segregation—by law or other

wise—in any of the facilities of the terminal, as distin

guished from the restaurant located in the same building.

The space utilized for the restaurant facilities was leased

to an independent corporation which was in no way under

the control of, or affiliated with, the bus company. The writ

ten lease between Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc. and Bus

Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc. is a part of the rec

ord in this case and, as was said of a comparable document

in N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis— San Francisco Railway Co.,

supra at 343:

“The lease is silent as to racial segregation. The

Terminal has certain powers of supervision for a pur

pose which may be described as policing. The lessee is

obligated to ‘comply with the requirements of the De

partment of Public Health, City of Richmond, and

with all other lawful governmental rules and regula

tions.’ The context, however, indicates that this re

quirement is for the purpose of keeping the premises

in a neat, clean, and orderly condition, and does not

9

render the lessee liable for violations of the Interstate

Commerce Act.”

Significantly, counsel for the petitioner did not assert—

either in their petition for writ of certiorari or in their brief

—that the validity of the Virginia statute under the Inter

state Commerce Act was one of the questions presented by

this appeal, and they concede that Congress has expressed

no specific intent concerning an arrest and conviction like

that of the petitioner in the case at bar (Brief, p. 19). More

over, counsel for the petitioner have devoted less than two

pages to this point in their argument on brief. In so doing,

it would appear that they have accorded this contention a

consideration proportioned to its merit.

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761, provides

an appropriate point of departure for consideration of peti

tioner’s principal contention, i.e., that invocation of the

Virginia statute under the circumstances of the case at bar

is repugnant to the Commerce Clause of the United States

Constitution. The dominant question presented in that case

was whether or not the Arizona Train Limit Law, which

limited the length of railroad trains operating in Arizona

to fourteen passenger and seventy freight cars, contravened

the Commerce Clause. With respect to the principles gov

erning the resolution of that question and the proper appli

cation of those principles to the case before it, this Court

observed (325 U. S. at 766-771):

“Although the commerce clause conferred on the

national government power to regulate commerce, its

possession of the power does not exclude all state power

of regulation. Ever since Wilson v. Black Bird Creek

Marsh Co. 2 Pet (US) 245, 7 L ed 412, and Cooley v.

Port Wardens, 12 How (US) 299, 13 L ed 996, it has

been recognized that, in the absence of conflicting legis-

10

lation by Congress, there is a residuum of power in the

state to make laws governing matters of local concern

which nevertheless in some measure affect interestate

commerce or even, to some extent, regulate it.

5fc ijc

“But ever since Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. (US) 1,

6 L ed 23, the states have not been deemed to have au

thority to impede substantially the free flow of com

merce from state to state, or to regulate those phases

of the national commerce which, because of the need of

national uniformity, demand that their regulation, if

any, be prescribed by a single authority.

* * *

“In the application of these principles some enact

ments may be found to be plainly within and others

plainly without state power. But between these ex

tremes lies the infinite variety of cases, in which regu

lation of local matters may also operate as a regulation

of commerce, in which reconciliation of the conflicting

claims of state and national power is to be attained only

by some appraisal and accommodation of the competing

demands of the state and national interests involved.

* * *

“Congress has undoubted power to redefine the dis

tribution of power over interstate commerce. It may

either permit the states to regulate the commerce in a

matter which would otherwise not be permissible . . .

or exclude state regulation even of matters of peculiarly

local concern which nevertheless affect interstate com

merce. * *

“But in general Congress has left it to the courts to

formulate the rules thus interpreting the commerce

clause in its application, doubtless because it has . . .

been aware that in their application state laws will not

be invalidated without the support of relevant factual

material which will ‘afford a sure basis’ for an informed

11

judgment. Terminal R. Asso. v. Brotherhood of R.

Trainmen, supra (318 US 8, 87 L ed 578, 63 S Ct 420);

Southern R. Co. v. King, 217 US 524. 54 L ed 868,

30 S Ct 594. Meanwhile, Congress has accomodated its

legislation as have the states, to these rules as an

established feature of our constitutional system. There

has thus been left to the states wide scope for the regu

lation of matters of local state concern, even though it

in some measure affects the commerce, provided it does

not materially restrict the free flow of commerce across

state lines, or intefere with it in matters with respect to

which uniformity of regulation is of predominant na

tional concern.

“Hence the matters for ultimate determination here

are the nature and extent of the burden which the state

regulation of interstate trains, adopted as a safety

measure, imposes on interstate commerce, and whether

the relative weights of the state and national interests

involved are such as to make inapplicable the rule,

generally observed, such as to make inapplicable the

rule generally observed, that the free flow of interstate

commerce and its freedom from local restraints in mat

ters requiring uniformity of regulation are interests

safeguarded by the commerce clause from state inter

ference.” (Italics supplied)

Consistent with the principles thus enunciated, this Court

proceeded to consider and evaluate the “relevant factual

material” which afforded “a sure basis” for its “informed

judgment” that the Arizona statute in fact imposed an

undue burden upon interstate commerce. This material con

sumed some 3000 pages of the printed record before the

Court in that case, and in its opinion, this Court repeatedly

referred to the “evidence”, the “statistics introduced into the

record” and the “detailed findings” which the record amply

supported. Id. at 775-778. Only after a full analysis of the

12

record evidence did this Court conclude that the statute under

consideration infringed the Commerce Clause.

In Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, the question pre

sented was whether or not a statute of Virginia requiring

racial separation of passengers on buses operated by intra

state and interstate motor vehicle carriers was antagonistic

to the Commerce Clause. Invalidating the statute there un

der consideration, this Court stated (328 U. S. at 377-381) :

“There is a recognized abstract principle, however,

that may be taken as a postulate for testing whether

particular state legislation in the absence of action by

Congress is beyond state power. This is that the

state legislation is invalid if it unduly burdens that

commerce in matters where uniformity is necessary—

necessary in the constitutional sense of useful in accom

plishing a permitted purpose. Where uniformity is

essential for the functioning of commerce, a state may

not interpose its local regulation. Too true it is that

the principle lacks in precision. Although the quality

of such a principle is abstract, its application to the

facts of a situation created by the attempted enforce

ment of a statute brings about a specific determination,

as to whether or not the statute in question is a burden

on commerce. Within the broad limits of the principle,

the cases turn on their own facts.

^

“On appellant’s journey, this statute required that

she sit in designated seats in Virginia. Changes in seat

designation might be made ‘at any time’ during the

journey when ‘necessary or proper for the comfort

and convenience of passengers.’ This occurred in this

instance. Upon such change of designation, the statute

authorizes the operator of the vehicle to require, as he

did here, ‘any passenger to change his or her seat as it

may be necessary or proper.’ An interstate passenger

must if necessary repeatedly shift seats while moving

13

in Virginia to meet the seating requirements of the

changing passenger group. On arrival at the District

of Columbia line, the appellant would have had freedom

to occupy any available seat and so to the end of her

journey.

“Interstate passengers traveling via motors between

the north and south or the east and west may pass

through Virginia on through lines in the day or in the

night. The large buses approach the comfort of pull-

mans and have seats covenient for rest. On such inter

state journeys the enforcement of the requirements for

reseating would be disturbing.

* *

“As our previous discussion demonstrates, the trans

portation difficulties arising from a statute that requires

commingling of the races, as in the De Cuir Case, are

increased by one that requires separation, as here.”

(Italics supplied)

The doctrine enunciated in these cases is not ancient

history, nor are the decisions themselves judicial relics of

some lost civilization. The opinion of this Court in Bibb v.

Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U. S. 520, decided May 25-

1959, convincingly demonstrates that the principles under

consideration have not been enervated by the passage of

time and that they apply with undiminished vitality to pre

sent day litigation. Indeed, counsel for the petitioner con

cede that “the vigor of the Morgan and Southern Pacific

cases was reaffirmed” by this Court’s decision in the Bibb

case.

Under consideration in that case was the question of

whether or not an Illinois statute requiring a certain type

of rear fender mudguard on trucks and trailers operating

on the highways of that State conflicted with the Com

merce Clause. Sustaining the decision of a specially con-

14

stituted three-judge District Court declaring the Illinois

statute violative o£ the Commerce Clause, this Court de

clared (359 U. S. at 524) :

“Unless we can conclude on the whole record that ‘the

total effect of the law as a safety measure in reducing

accidents and casualties is so slight or problematical

as not to outweigh the national interest in keeping inter

state commerce free from interferences which seriously

impede it’ (Southern P Co. v. Arizona, supra (325 US

pp 775, 776)) we must uphold the statute.” (Italics

supplied )

The Court then proceeded to a consideration of the exhaus

tive findings of the trial court relating to the cost, safety,

time loss and interference with the “interline” operations

of motor carriers occasioned by an interstate carrier’s com

pliance with the challenged statute. At the conclusion of its

review, the Court pointed out (359 U. S. at 528) :

“This in summary is the rather massive showing of

burden on interstate commerce which appellees made at

the hearing.” (Italics supplied)

Mr. Justice Harlan, with whom Mr. Justice Stewart joined,

authored a separate concurring opinion which is sufficiently

brief and sufficiently significant to merit full reproduction

in the body of this brief (359 U. S. at 530).

“The opinion of the Court clearly demonstrates the

heavy burden, in terms of cost and interference with

‘interlining,’ which the Illinois statute here involved

imposes on interstate commerce. In viezv of the find

ings of the District Court, summarised on page 5 of

the Court’s opinion and fully justified by the record,

to the effect that the contour mudflap ‘possesses no ad

vantages’ in terms of safety over the conventional flap

IS

permitted in all other States, and indeed creates certain

safety hazards, this heavy burden cannot be justified

on the theory that the Illinois statute is a necessary,

appropriate, or helpful local safety measure. Accord

ingly, I concure in the judgment of the Court.” (Italics

supplied)

The opinions of this Court in the Southern Pacific,

Morgan and Bibb cases bring into bold relief the patent

inadequacy of the instant record to present to this Court

any substantial question of conflict between the Virginia

statute and the Commerce Clause. The entire appellate

record in the case at bar is less than thirty-five pages in

length, and the transcribed evidence relates exclusively to

the circumstances under which the petitioner was charged

with violating the Virginia statute forbidding trespass to

private property. Not a single item of evidence has been

presented by the petitioner which even purports to estab

lish that the regulation of the lessee non-carrier restaurant

company and the Virginia statute under consideration in the

instant case “materially restrict the free flow of commerce”

across state lines; nor has any evidence been presented which

even remotely tends to demonstrate “the nature and extent

of the burden”, if any, which the regulation and statute

impose on interstate commerce. Southern Pacific Co. v.

Arizona, supra at 770. In light of the decisions discussed

above, it is manifest that a claim of repugnance to the Com

merce Clause of the United States Constitution cannot be

supported by mere speculation and conjecture and that the

regulation of the restaurant company and the State statute

challenged here cannot be held invalid in the absence of

a clear showing that they constitute an interference with

interstate commerce. In this situation, it is essential that

there be record evidence upon which this Court may ground

16

a conclusion that the regulation and statute unduly burden

interstate commerce. Since the record in this case is devoid

of any evidence tending to establish this proposition, the

critical issue in this case is highlighted by an eventuary

vacuum, and an appropriate case for judicial intervention

has not been made out.

It is obvious that this Court cannot “find” or “conclude”

or “demonstrate” on the basis of the record in the instant

case that the statute and regulation here under attack have

even the remotest peripheral effect upon interstate commerce,

much less that they impermissibly burden such commerce.

Moreover, it is no part of the judicial function for courts

to be ingenious in searching out grounds upon which state

or federal legislation may be invalidated. On the contrary,

as this Court recently iterated in a similar context, to indulge

such a view “would be to ignore the teaching of this Court’s

decisions which enjoin seeking out conflicts between state

and federal regulation where none clearly exists.” Huron

Cement Co. v. City of Detroit,----U. S........ , 80 S. Ct. 813,

decided April 25, 1960.

Invalidation of the legislation under attack in the instant

case upon the ground that, in its operation, it unduly burdens

interstate commerce, would manifestly subvert the judicial

principles enunciated by Mr. Justice Frankfurter in his

concurring opinion in American Fed. of Labor v. American

Sash & Door Co., 335 U. S. 538, 555-557:

“In the day-to-day working of our democracy it is

vital that the power of the non-democratic organ of our

Government be exercised with rigorous self-restraint.

Because the powers exercised by this Court are inher

ently oligarchic, Jefferson all of his life thought of the

Court as ‘an irresponsible body’ and ‘independent of

the nation itself’. The Court is not saved from being

oligarchic because it professes to act in the service of

17

humane ends. As history amply proves, the judiciary

is prone to misconceive the public good by confounding

private notions with constitutional requirements, and

such misconceptions are not subject to legitimate dis

placement by the will of the people except at too slow a

pace. * * *

“Our right to pass on the validity of legislation is

now too much a part of our constitutional system to be

brought into question. But the implications of that

right and the conditions for its exercise must constant

ly be kept in mind and vigorously observed. Because

the Court is without power to shape measures for deal

ing with the problems of society but has merely the

power of negation over measures shaped by others, the

indispensable judicial requisite is intellectual humility,

and such humility presupposes complete disinterested

ness. And so, in the end, it is right that the Court,

should be indifferent to public temper and popular

wishes. * * * A court which yields to the popular will

thereby licenses itself to practice despotism, for there

can be no assurance that it will not on another occasion

indulge its own will. Courts can fulfill their responsi

bility in a democratic society only to the extent that they

succeed in shaping their judgments by rational stand

ards, and rational standards are both impersonal and

communicable. Matters of policy, however, are by defi

nition matters which demand the resolution of conflicts

of value, and the elements of conflicting values are

largely imponderable. Assessment of their competing

worth involves differences of feeling; it is also an exer

cise in prophecy. Obviously the proper forum for

mediating a clash of feelings and rendering a prophetic

judgment is the body chosen for those purposes by the

people. Its functions can be assumed by this Court only

in disregard of the historic limits of the Constitution.”

Finally, counsel for respondent submit that none of the

decisions cited by petitioner is applicable to the situation

which obtains in the instant case. These decisions were also

relied upon in Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant,

18

4 Cir., 268 F. 2d 845, in which case the petitioner con

tended that his exclusion from the Howard Johnson’s Res

taurant in the City of Alexandria, Virginia, on racial

grounds amounted to discrimination against a person mov

ing in interstate commerce and also interference with the

free flow of commerce in violation of the Constitution of

the United States. With respect to these decisions, the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

declared (268 F. 2d at 848) :

“The cases upon which the plaintiff relies in each

instance disclosed discriminatory action against persons

of the colored race by carriers engaged in the trans

portation of passengers in interstate commerce. In

some instances the carrier’s action was taken in accord

ance with its own regulations, which were declared il

legal as a violation of paragraph 1, section 3 of the

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U.S.C.A. Sec. 3(1),

which forbids a carrier to subject any person to undue

or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any re

spect, as in Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80, 61

S. Ct. 873, 85 L. Ed. 1201, and Henderson v. United

States, 339 U. S. 816, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. Ed. 1302.

In other instances, the carrier’s action was taken in

accordance with a state statute or state custom requir

ing the segregation of the races by public carriers and

was declared unlawful as creating an undue burden on

interstate commerce in violation of the commerce clause

of the Constitution, as in Morgan v. Com. of V irginia,

328 U. S. 373, 66 S. Ct. 1050, 90 L. Ed. 1317; Williams

v. Carolina Coach Co., D. C. Va., I l l F. Supp. 329,

affirmed 4 Cir., 207 F. 2d 408; Flemming v. S. C.

Elec. & Gas Co., 4 Cir., 224 F. 2d 752; and Chance v.

Lambeth, 4 Cir., 186 F. 2d 879.

“In every instance the conduct condemned was that

of an organisation directly engaged in interstate com

merce and the line of authority would be persuasive in

19

the determination of the present controversy if it could

be said that the defendant restaurant zms so engaged.

We think, however, that the cases cited are not appli

cable because we do not find that a restaurant is en

gaged in interstate commerce merely because in the

course of its business of furnishing accommodations to

the general public it serves persons who are traveling

from state to state. As an instrument of local com

merce, the restaurant is not subject to the constitutional

and statutory provisions discussed above and, thus, is

at liberty to deal with such persons as it may select.”

(Italics supplied)

II.

The Virginia Statute and the Fourteenth Amendment

The petitioner’s contention that his arrest and conviction

for trespass violates Fourteenth Amendment rights is

worthy of little consideration.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, expressly held that the

Fourteenth Amendment erects no shield against merely pri

vate conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful. The

Court pointed out that since the decision of this Court in the

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, the principle has become

firmly imbedded in our constitutional law that the action

inhibited by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment

is only such action as may be fairly said to be that of the

States.

In United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629, this Court,

quoting from United States v. Cruickshank, 92 U. S. 542,

said:

“ 'The fourteenth amendment prohibits a state from

depriving any person of life, liberty or property with

out due process of law, or from denying to any person

the equal protection of the laws; but this provision does

not add anything to the rights of one citizen as against

20

another. It simply furnishes an additional guaranty

against any encroachment by the states upon the funda

mental rights which belong to every citizen as a mem

ber of society. The duty of protecting all its citizens in

the enjoyment of an equality of rights was originally

assumed by the states, and it remains there. The only

obligation resting upon the United States is to see that

the states do not deny the right. This the amendment

guarantees, and no more. The power of the national

government is limited to this guaranty.’ ”

If the restaurant involved in this case is not subject to

regulation by Congress under its power to regulate inter

state commerce, the company operating it is free to select

its patrons upon any basis it sees fit, and, in the case at bar,

was within its rights in directing the petitioner to leave the

section of the restaurant reserved for white patrons.

In the last two years, five decisions—one by the Supreme

Court of North Carolina, one by the Supreme Court of

Delaware, one by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth circuit, one by the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Maryland, and the other, this

case, from the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, have

all sustained the right of the operator of a private restaurant

to discriminate on the basis of race as against the conten

tion that such action was proscribed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. There has been no decision to the contrary,

State or Federal, so far as we are aware, and none has been

cited here.

In State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295,

decided in 1958, a trespass conviction similar to that in

volved in this case, was upheld. The Court, after citing and

quoting from the Civil Rights Cases, supra, and U. S. v.

Harris, supra, said:

21

"More than half a century after these cases were

decided the Supreme Court of the United States said

in Shelley v. Krunner. 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 842,

92 L. Ed. 1161, 3 A.L.R. 2d 441: ‘Since the decision

of this Court in the Civil Rights Cases, 1883, 109 U. S.

3, 3 S. Ct. 18, 27 L. Ed. 835, the principle has become

firmly embedded in our constitutional law that the

action inhibited by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment is only such action as may fairly be said

to be that of the States. That Amendment erects no

shield against merely private conduct, however discrim

inatory or wrongful.’ This interpretation has not been

modified: Collins v. Hardyman, 341 U. S. 651, 71 S.

Ct. 937, 95 L. Ed. 1253; District of Columbia v.

Thompson Co., 346 U. S. 100, 73 S. Ct. 1007, 97 L. Ed.

1480; Williams v. Yellow Cab Co., 3 Cir., 200 F. 2d

302, certiorari denied Dargan v. Yellow Cab Co., 346

U. S. 840, 74 S. Ct. 52, 98 L. Ed. 361.

“Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Tozvn Corp., 299 N. Y. 512,

87 N. E. 2d 541, 14 A.L.R. 2d 133, presented the right

of a corporation, organized under the New York law

to provide low cost housing, to select its tenants, with

the right to reject on account of race, color, or religion.

The New York Court of Appeals affirmed the right of

the corporation to select its tenants. The Supreme

Court of the United States denied certiorari, 339 U. S.

981, 70 S. Ct. 1019, 94 L. Ed. 1385.

“The right of an operator of a private enterprise to

select the clientele he will serve and to make such selec

tion based on color, if he so desires, has been repeatedly

recognized by the appellate courts of this nation [ Citing

cases]. The owner-operator’s refusal to serve defend

ants, except in the portion of the building designated

by him, impaired no rights of defendants.” 101 S. E.

2d 295, 299.

In Williams v. Howard Johnson's Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845, decided in 1959, Judge Soper, in speaking for the

22

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, held that a restaurant, as

an instrument of local commerce is not subject to the provi

sions of the Fourteenth Amendment, notwithstanding the

substantial inconvenience and embarrassment to which per

sons of the Negro race may be subject in the denial to them

of the right to be served in public restaurants. Judge Soper

observed in his opinion:

“The plaintiff concedes that no statute of Virginia

requires the exclusion of Negroes from public restau

rants and hence it would seem that he does not rely upon

the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment which

prohibit the States from making or enforcing any lazv

abridging the privileges and immunities of citizens of

the United States or denying to any person the equal

protection of the law. He points, however, to statutes

of the State which require the segregation of the races

in the facilities furnished by carriers and by persons

engaged in the operation of places of public assemblage;

he emphasises the long established local custom of ex

cluding Negroes from public restaurants and he con

tends that the acquiescence of the State in these prac

tices amounts to discriminatory State action which falls

within the condemnation of the Constitution. The es

sence of the argument is that the State licenses restau

rants to serve the public and thereby is burdened with

the positive duty to prohibit unjust discrimination in

the use and enjoyment of the facilities.

“This argument fails to observe the important dis

tinction between activities that are required by the

State and those which are carried out by voluntary

choice and without compulsion by the people of the

State in accordance with their own desires and social

practices. Unlike these actions are performed in obedi

ence to some positive provision of State lazv they

do not furnish a basis for the pending complaint.

The license laws of Virginia do not fill the void

Section 35-26 of the Code of Virginia, 1950, makes it

23

unlawful for any person to operate a restaurant in the

State without an unrevoked permit from the Commis

sioner, who is the chief executive officer of the State

Board of Health. The statute is obviously designed to

protect the health of the community but it does not

authorize State officials to control the management of

the business or to dictate what persons shall be served.

The customs of the people of a State do not constitute

State action within the prohibition of the Fourteenth

Amendment. As stated by the Supreme Court of the

United States in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; 68 S.

Ct. 836, 842:

‘Since the decision of this Court in the Civil

Rights Cases, 1883, 109 U. S. 3, * * * the prin

ciple has become firmly embedded in our constitu

tional law that the action inhibited by the first sec

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment is only such

action as may fairly be said to be that of the States.

That Amendment erects no shield against merely

private conduct, however discriminatory or wrong

ful.’ ” (Italics supplied)

See, also, Wilmington Parking Authority v. Burton, 157

A. 2d 894, decided in January, I960, and Slack v. Atlantic

White Tower System, 181 F. Supp. 124, decided in Feb

ruary, 1960.

Counsel for the petitioner nowhere asserts that there exists

any independent “right” to equal treatment in the use of a

privately owned place of public accommodation which can

not be denied by the owner on the ground of race or color.

The Solicitor General in several instances uses passages in

his brief referring to such a “right,” though in most in

stances he is careful to add qualifying phrases, such as, “as

in this case, interstate transportation facilities.”

We have shown above that the restaurant here involved

24

is not such a facility that has been subject to regulation by

Congress under the commerce clause.

In the absence of a state law forbidding discrimination,

such as has been enacted in a number of states, whence

comes such “right” to equal treatment in the use of places

of public accommodation? If it be a “right,” it is some

thing that the petitioner could assert against any who would

deny it to him. If it is not something that he can assert

against anyone, or any entity—public or private—then it is

not a “right” ; that is to say, it is not something to which

he is entitled.

While it may be that the state itself could not deny to the

petitioner the equal opportunity to use a place of public

accommodation, or deny him equal protection in the exer

cise of such an opportunity if it be afforded to him by the

private owner, we have yet to be informed from whence

the petitioner has secured any “right” to use such accommo

dation as against the wishes of the owner of the establish

ment.

The cases cited by the petitioner, and Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80 and McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F.

Ry., 235 U. S. 151, cited by the Solicitor General, were, as

Judge Soper said of the cases cited by the plaintiff in Wil

liams v. Howard Johnsons Restaurant, all cases dealing

with facilities of carriers actually engaged in interstate com

merce.

The Solicitor General has, in the brief amicus curiae, so

intertwined cases dealing with interstate commerce, cases

dealing with state-owned or operated facilities, and cases

dealing with state statutes which in themselves impose dis

criminations, and by quotations out of context has so dis

torted former decisions of this Court, that we think a few

comments concerning that brief are necessary.

25

First, after accurately paraphrasing with partial quota

tions two statements which this Court did make in the Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U. S, 3, which statements were not essen

tial to the Court’s decision, the Solicitor General then im

properly and incorrectly paraphrases a third statement made

by this Court in those cases.

While the Court did say that “positive rights and privi

leges” are secured by the Fourteenth Amendment, and that

that provision does nullify State action of every kind which

impairs the “privileges and immunities” of citizens of the

United States (but without defining such rights, privileges

or immunities), it nowhere stated that, “Racially discrimi

natory acts of individuals, moreover, are insulated from the

proscription of the Fourteenth Amendment only insofar as

they are ‘unsupported by State authority in the shape of

laws, customs, or judicial or executive proceedings,’ or are

‘not sanctioned in some way by the State.’ ” Brief amicus