Maxwell v. Bishop Brief Amici Curiae Urging Reversal

Public Court Documents

October 24, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Bishop Brief Amici Curiae Urging Reversal, 1969. b1dcfc5c-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/31a6aa2f-4355-4030-8a32-739eeb25e328/maxwell-v-bishop-brief-amici-curiae-urging-reversal. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

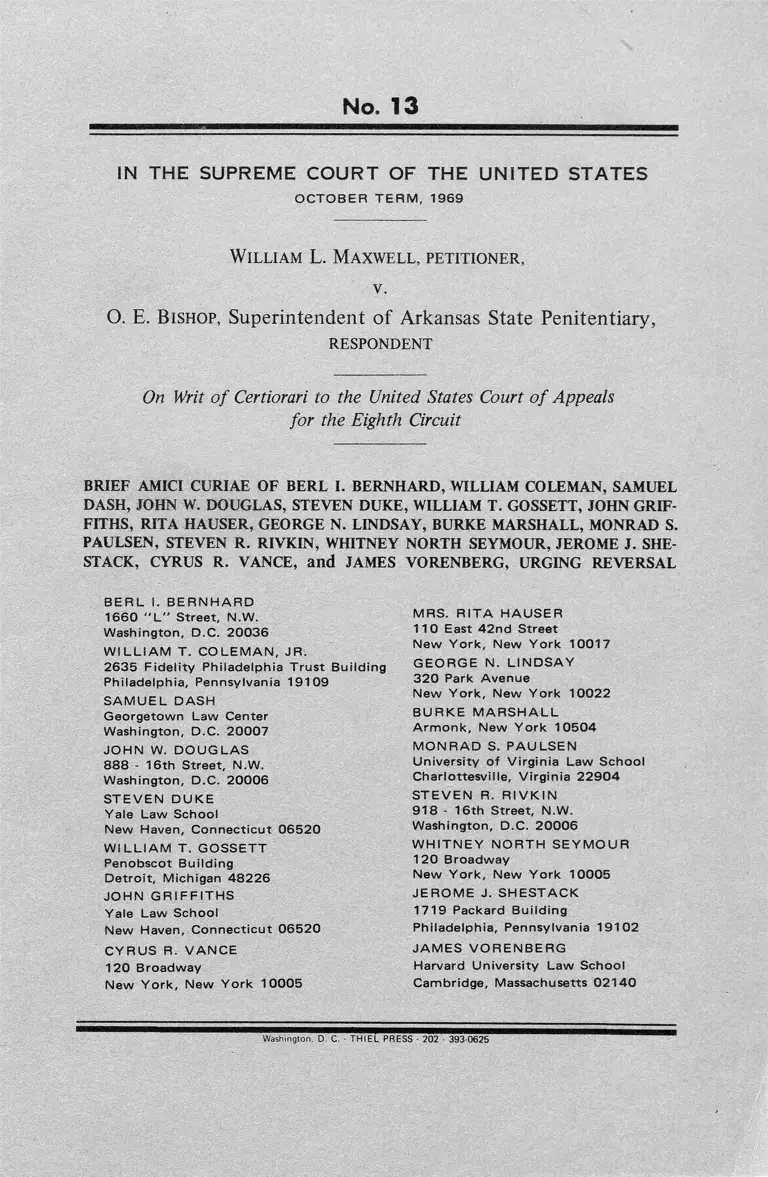

No. 13

IN THE SUPREME CO URT OF TH E U N ITED S TA TES

O C TO BER TERM , 1969

William L. Maxwell, petitioner,

v.

O. E. Bishop, Superintendent of Arkansas State Penitentiary,

RESPONDENT

On Writ o f Certiorari to the United States Court o f Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF BERL 1. BERNHARD, WILLIAM COLEMAN, SAMUEL

DASH, JOHN W. DOUGLAS, STEVEN DUKE, WILLIAM T. GOSSETT, JOHN GRIF

FITHS, RITA HAUSER, GEORGE N. LINDSAY, BURKE MARSHALL, MONRAD S.

PAULSEN, STEVEN R. RIVKIN, WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, JEROME J. SHE-

STACK, CYRUS R. VANCE, and JAMES VORENBERG, URGING REVERSAL

BERL I. BERNHARD

1660 " L ” Street, N,W,

Washington, D.C. 20036

W ILLIAM T . COLEM AN, JR.

2635 Fidelity Philadelphia Trust Building

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19109

S A M U E L DASH

Georgetown Law Center

Washington, D.C, 20007

JOHN W. DO UG LA S

888 - 16th Street, N.W,

Washington, D.C. 20006

S TEV EN DUKE

Yale Law School

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

W ILLIAM T . GOSSETT

Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

JOHN G R IF F ITH S

Yale Law School

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

CYRUS R. VANCE

120 Broadway

New York, New York 10005

MRS. R ITA HAUSER

110 East 42nd Street

New York, New York 10017

GEO RG E N. LINDSAY

320 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10022

BURKE M A R S H ALL

Armonk, New York 10504

M ONRAD S. PAULSEN

University of Virginia Law School

Charlottesville, Virginia 22904

S TEV EN R. RIVKIN

918 - 16th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

W H ITN E Y N O R TH S EYM O UR

120 Broadway

New York, New York 10005

JEROM E J. SH ESTACK

1719 Packard Building

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102

JAMES VOR EN BERG

Harvard University Law School

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140

D. C. ■Washington, T H IE L PRESS - 202 - 393-0625

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

C ita tion s.............................................................................................. (i)

Interest of Amici Curiae........................................................ 1

Argument .................................................. 3

I. Without appropriate standards, the Arkansas single

verdict procedure is susceptible to racially motivated

decisions on the imposition of the death penalty, in

violation of the constitution’s due process and equal

protection guarantees............................................................. 3

II. The single-verdict procedure compounds the vices of

standardless sentencing and imposes needless and im

permissible burdens on the right to a fair trial on the

issue of guilt or in n o cen ce .................................................. 14

Conclusion............................................................................................ 18

CITATIONS

Cases:

Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532 (1965) .......................................... 10

Giacco v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966) .........................4, 13

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1 9 6 5 )____ 7, 12, 15, 17, 18

Higgins v. Peters, U.S. District Court, No. LR-68-e-176,

E.D. Ark. (September 25, 1 9 6 8 ) ............................................. 7

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1 9 6 4 ) ......................... 6, 15, 18

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1957) ...................... .. ............. 7

Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 U.S. 596 (1 9 4 4 ) .................................. 6

In Re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133 (1955) .................................... 10

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711

(1 9 6 9 ) .................................................................. 9 , 1 2 , 1 5 , 1 7 , 1 8

Offutt v. United States, 348 U.S. 11 ( 1 9 5 4 ) ......................... .. 10

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 ( 1 9 6 1 ) ............................... 6

Searber v. State, 226 Ark. 503, 291 S.W. 2d 241 (1956). . . 14

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1 9 6 6 ) ................. .. . 10

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1 9 6 7 ).................................... 11, 12

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1 9 2 7 ).......................................... 10

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 ( 1 9 6 8 ) ...................... 14

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 4 ) ................. 16

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1 9 6 8 ).............................. 8

Worcester v. Commissioner, 370 F.2d 713 (First Cir.

1 9 6 6 ) ........................................................................................... 16

Statutes:

Model Penal Code, American Law Institute, Section

210.6 ............................................................................................... 13

Other Authorities:

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Admini

stration of Justice, Report “The Challenge of Crime in

a Free Society” (1967) ....................................................... .. . 9

Wright, Federal Practice and Procedure (Criminal) Sections

485, 487 (1 9 6 7 ) ................................................................................ 6

(ii)

IN TH E SUPREME C O U R T OF TH E U N IT E D S T A T E S

O C T O B E R T E R M , 1969

No. 13

WILLIAM L. MAXWELL,

Petitioner,

v.

0 . E. BISHOP,

Superintendent of Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

On Writ o f Certiorari to the United States Court o f Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF BERL I. BERNHARD, WILLIAM COLEMAN,

SAMUEL DASH, JOHN W. DOUGLAS, STEVEN DUKE, WILLIAM T. GOS

SETT, JOHN GRIFFITHS, RITA HAUSER, GEORGE N. LINDSAY, BURKE

MARSHALL, MONRAD S. PAULSEN, STEVEN R. RIVKIN, WHITNEY

NORTH SEYMOUR, JEROME J. SHESTACK, CYRUS R. VANCE, an d JAMES

VORENBERG, URGING REVERSAL.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

The amici curiae join to tender Argument to the Court

on an aspect of this case which reflects the most funda-

1 Pursuant to Rule 42, paragraph 2, there have been lodged with

the Clerk the written consents of the parties to the filing of this

Brief Amici Curiae.

2

mental dimensions of their individual professional respon

sibilities as members of the Bar.

The first motivation prompting this brief is a profes

sional concern to preserve and develop the standards of

fairness in the administration of justice standing at the

heart of our constitutional structure. Each of the signers

of this brief is familiar with the problems of criminal law

enforcement and with the practical requirement that the

American system of criminal justice function with sub

stantial fairness to all accused of crime.

In addition, each of the signers of this brief has pledged

his professional skills to the fulfillment for all Americans

of civil rights under law. Since the context in which this

case rises to Constitutional proportions is shaped by the

factor of race, the signers consider Argument with respect

to the bearing of this factor essential to the full and

proper development of the questions fairly comprised in

this case.

Because considerations of procedural fairness and racial

justice come together in the constitutional issues here on

review, the undersigned hereby respectfully tender this

brief amici curiae.

3

ARGUMENT

I.

WITHOUT APPROPRIATE STANDARDS, THE ARKANSAS

SINGLE-VERDICT PROCEDURE IS SUSCEPTIBLE TO

RACIALLY MOTIVATED DECISIONS ON THE IMPOSI

TION OF THE DEATH PENALTY, IN VIOLATION OF THE

CONSTITUTION’S DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PRO

TECTION GUARANTEES.

Standards to guide juries in selecting convicted persons

for capital punishment are essential to comply with the

Due Process requirement that discretion be limited and

that the criminal process include structural guarantees

against decisions based on passion and prejudice, as well

as the Equal Protection requirement that the State not

invite racially motivated decisions. Appropriate stand

ards can be devised by any State which wishes to delegate

to juries the power to impose the death sentence.

A.

The death penalty for a “capital” offense has become

the exception, rather than the rule, and this accentuates

the need for standards to determine the occasions on

which it is to be inflicted if administration of the death

penalty is to meet Due Process requirements. The

current rarity of the death penalty also destroys the

support of tradition for the Arkansas practice.

Only a small fraction of persons convicted of offenses

for which death is a possible penalty actually receive the

death sentence, in Arkansas or anywhere else (see Peti

tioner’s Appendix B, at 24a-34a). It is now unthinkable

that any significant proportion of “capital” offenders

could be put to death. Thus the definitions of so-called

4

“capital offenses” no longer reveal anything about the

criteria by which the death sentence may be imposed.

In capital cases, the absence of any relationship between

the elements of the offense and the punishment imposed

makes compelling the need for explicit standards to

guide the jury. The sentencing jury in a capital case is

empowered to select for a special and awesome penalty

a very few victims from among the total pool of con

victed persons. It should hardly require argument that

the power to make such a selection cannot be delegated

without any standards at all-in a constitutional system

which will not allow delegation of the power to impose

court costs on an acquitted defendant as on a mere find

ing that he was guilty of “some misconduct” which “has

given rise to the prosecution.” Giacco v. Pennsylvania,

382 U.S. 399 (1966). Due process of law is denied in

the most fundamental way when a decision to forfeit

life is made on the basis of no legal rule at all.

Earlier in our history, when the death sentence was a

normal adjunct to a conviction, the definition of a

capital crime generally provided some guidance for the

occasions on which capital punishment would be

inflicted, and made plausible the proposition that a jury

might lawfully be left with unguided discretion to dis

pense mercy. There is unquestionably a great difference

between discretion to reprieve and discretion to take a

life. Ultimately, whether a situation involves the one or

the other is a question of fact. The fact is that capital

sentencing in 1969 consists of the selection of victims,

not the selection of persons to be spared.

When a death sentence is no longer a serious possibility

for the vast majority who commit the proscribed

5

offense, it becomes a fiction to pretend that the commis

sion of the offense itself is the cause of the sentence.

The offense has become an excuse to execute a man for

other unrelated or virtually unrelated reasons. Perhaps

such a system is permissible—but only i f these collateral

reasons are clearly prescribed. Arkansas’ juror, delegated

the power to make society’s most awesome choice, is

given no criteria upon which to make it. He is left to his

prejudices and his subconscious for the keys to decision.

Often, as Petitioner’s statistics at least strongly suggest,

the juror is moved by his fear of difference and decides

to impose the death penalty upon the defendant because

of his race.

The disappearance of the death penalty as a normal

consequence of conviction for even the most heinous

offenses has not only enlarged the operational content

of jury “discretion”, and created the necessity for

standards, it has eliminated tradition as a ground for

perpetuating the Arkansas practice. The issue now

before the Court is vastly different from what it might

have been even a few decades ago, though it remains

clothed in the same conceptual garments.

B.

The Arkansas procedure is tantamount to an instruc

tion that race may be taken into account and is thus a

deprivation of Equal Protection of the Laws.

If an Arkansas court, or any other court, were to

charge a sentencing jury that it could consider race in

deciding defendant’s fate, a sentence imposed by such a

jury would be void with no proof whatever that the jury

6

had actually been racially motivated in fixing the sen

tence (see Petition for Certiorari, pp. 45-47). The same

Constitutional rule is a fortiori where the sentence is

death. Our system of jury trials rests on the assumption

that juries are guided and influenced by what they are

and are not told by the presiding judge. Countless con

victions are reversed every year in every jurisdiction for

error in the charge. It is not uncommon for a conviction

to be overturned for the sole reason that an instruction,

though not erroneous, was unclear or confusing. See

Wright, Federal Practice and Procedure (Criminal) Sec

tions 485, 487 (1969). Numerous convictions have been

upset for no other reason than the failure of the court to

instruct fully on some basic point—e.g., reasonable

doubt, the presumption of innocence, or the elements of

the offense, Wright supra at Sections 487, 500. In such

cases, it is no answer that the jury probably understood

anyway, that the omissions were supplied in summation,

that guilt was clear, or that the point was not really in

issue. The possibility of misunderstanding is enough to

vitiate the proceedings. This Court has applied the same

rule when the error in the instructions is of constitutional

dimension. Compare, Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S.

5341, 546 (n. 4) (1961) with Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322

U.S. 596, 600-601 (1944); and see Jackson v. Denno,

378 U.S. 368, 368-387 (1964).

A brief examination of the context in which peti

tioner’s jury was charged compels the conclusion that

some, if not all, of his jurors probably understood the

charge as authorizing them to take race into account in

deciding his fate. At the time of petitioner’s 1962 trial,

Arkansas law required the selection of jurors from

electors, defined as those who had paid their county

7

poll tax, and the names of such persons were required to

be kept in a poll tax book where they were designated

by race. The jury list itself indicated race (Petition for

Certiorari, p. 75). As recently as 1968, the Arkansas

miscegenation statute was being enforced, although

declared unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S.

1 (1967). See ILiggins v. Peters, U.S. District Court No.

LR-68-e-176, E.D. Ark., September 25, 1968 (declaring

the Arkansas statute invalid at the behest of a Negro man

and a white woman who were denied a marriage license).

During the thirty-two years immediately preceding peti

tioner’s trial, Arkansas executed only 1 white man for

rape while executing 17 Negroes (Petition for Certiorari,

p. 37, n. 21). Surely, no more extensive reconstruction

of the Arkansas social fabric of 1962 is needed to show

that the milieu from which petitioner’s jury was selected,

and in which it decided that he should die, was, at the

very least, tolerant of the view that rape by a Negro was

a more heinous offense than the same crime by a white

or that the life of a Negro defendant is less precious than

that of a white. Not having been told otherwise by the

court, it is altogether likely that the jury interpreted the

submission of the death penalty issue, without express

instruction, as authorization to take race into account.

This likelihood is certainly at least as great as the possi

bility of jury misunderstanding underlying the decisions

cited above, or the assumption that a jury which hears a

prosecutor’s comment on the defendant’s failure to take

the stand will feel authorized to take it into account.

Cf Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965). Indeed,

if, as we contend, an Arkansas jury would infer that race

is a permissible consideration in assessing penalty from

the submission as given, its understanding would have

8

been correct, for, in placing the issue of life or death in

the unrestricted discretion of the jury, the State of

Arkansas does authorize the jury to consider race, or any

other irrelevant or impermissible factor.

Since, as we have pointed out, possible misunder

standings of basic issues, attributable either to what the

jury was told or to what it was not told, suffice to

vitiate a garden variety of conviction, how can a wholly

different standard be applied when a life is to be taken?

The only conceivable distinction was rejected by this

Court when it noted that while deciding between life or

death is

“different in kind from a finding that the defendant

committed a specified offense . . . this does not

mean that basic requirements of procedural fairness

can be ignored simply because the determination

involved in this case differs in some respects from

the traditional assessment of whether the defendant

engaged in the proscribed conduct.” Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 521, n. 20 (1968).

In simply submitting the issue of life or death, without

comment, the trial court, in the context and under the

circumstances, conveyed a gross misconception which

deprived petitioner of Equal Protection of the laws and

necessarily voided his death sentence.

C.

Even if it be assumed, against all the evidence, that the

death penalty was not discriminatorily inflicted upon

petitioner, Due Process compels the introduction of

protections against the apparent risk of such dis

crimination.

9

Petitioner abundantly proved in the District Court

that “Negro defendants who rape white victims have

been disporportionately sentenced to death by reason of

race, during the years 1945-1965 in the State of

Arkansas,” (Petitioner’s Brief, p. 19), and the Court of

Appeals seemed to agree. The statistics for the nation at

large strongly imply that what is true in Arkansas is true

in the entire South (Id. at 13-14). Accumulated experi

ence and professional opinion is virtually unanimous,

moreover, that throughout the nation, “the death sen

tence is disproportionately imposed and carried out on

the poor, the Negro, and the members of unpopular

groups.” President’s Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Report (The Challenge of

Crime in a Free Society) (1967) 143.

The Court of Appeals was wrong in holding that peti

tioner was obliged to prove that his particular jury was

racially motivated, and that he failed to do so. Moreover,

no such impossible burden need be met to establish, at

the very least, that there was a substantial risk that a

totally uninstructed jury would give vent to imper

missible passions and prejudices in imposing the death

penalty. It would be rank hypocrisy to deny that such a

risk existed and was substantial. Nothing more is needed

to make it incumbent upon a court to take measures to

counteract the risk. Compare North Carolina v. Pearce,

395 U.S. 711 (1969), where this Court recently held

that explicit findings are essential to protect a defendant

against the apparent risk that his sentence might be

based upon an impermissible consideration (there,

penalty for a prior appeal).

At the heart of our concepts of Due Process and fair

trial is the notion that the process must be so structured

10

as to minimize passion, prejudice or corrupt motives as

ingredients of decision. Trials must not only be fair in

fact, they must appear fair as well. “Justice must satisfy

the appearance of justice.” Offutt v. United States, 348

U.S. 11, 14 (1954); In re Murchison, 349 U.S, 133, 136

(1955). See also, Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532, 542

(1965). There are myriad cases in which this Court has

refused to inquire behind the apparent unfairness of a

practice to see whether in the particular case actual

prejudice was effected. See, e.g., Turney v. Ohio, 273

U.S. 510 (1927) where the judge’s financial interest (to

the tune of $12) in the outcome of a case was enough to

invalidate his judgment. “Every procedure which would

offer a possible temptation to the average man. . . not to

hold the balance nice, clear and true between the State

and the accused, denies the latter due process of law.”

(273 U.S. at 532). A fine of $100 was involved. A

fortiori, the substance and appearance of fairness are

required where life is at stake, not merely in the deter

mination of guilt and innocence, but in the sentencing

procedure as well. Indeed, because there is so little con

nection between conviction and the death penalty, it is

the sentencing process which particularly demands

adherence to fair procedures.

There are many cases in which this Court has held that

specific steps must be taken to ensure the fairness-and

protect the appearance of fairness—of criminal trials.

The idea that Due Process involves affirmative protective

measures is nothing new. See, e.g., Sheppard v. Maxwell,

384 U.S. 333, (1966), where the Court stated that Due

Process requires trial judges to “take strong measures to

ensure that the balance is never weighed against the

accused”—there, by possibly prejudicial publicity; here,

we would argue, by the risk of race prejudice. Cf. also

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967) (instructions that

prior crimes, introduced pursuant to a recidivist statute,

could not be taken into account as to guilt).

A system which authorizes predominantly white,

middle class juries to mete out a death sentence to any

one they convict of a so-called “capital” offense, for any

reason or for no reason, and which promises those juries

that they will never be compelled to reveal or to articu

late their reasons or lack of reasons, and which results in

the disproportionate infliction of the death penalty on

Negroes, plainly fails in its duty both to be and to appear

fair. Due Process in its most elemental sense is glaringly

denied.

Although about as likely as the moon’s being a mirage,

it is nonetheless possible that no jury ever voted to kill a

defendant because of the color of his skin, his social

status, or his economic condition. Though every known

attempt of social scientists to determine the nexus

between the death penalty and race in the American

South has failed to exclude the link, though every known

statistical study shows a connection, though virtually all

students of the subject believe that there is a causal rela

tionship, everybody may be wrong. Everyone may also

be wrong that prejudicial publicity, as in Sheppard, supra,

wreaks prejudice. The point is that so long as the data is

such as to persuade virtually everyone who examines it

that juries are executing people because they are Negro,

Due Process demands that the sentencing process include

measures to counteract the apparent risk of unconstitu

tional discrimination. Surely, the likelihood of sen

tencing based upon an impermissible consideration has

12

been far more clearly demonstrated in this case than it

was in Pearce, supra, where this Court relied mainly

upon the State’s failure affirmatively to demonstrate a

proper basis. The Due Process need for prophylactic

rules— requiring specific findings, as in Pearce, or at least

instructions to the jury on permissible and impermissible

consideration—follows a fortiori in this case. The awe

some factor of death adds immeasurably to the need.

The State of California contends that “If Arkansas

jurors are . . . bent on racial discrimination, there is no

reason whatever to believe that they will be deterred in

carrying out such discrimination by any instruction or

combination of instructions which a judge may read to

them.” (Brief of California Amicus Curiae, in Support of

Respondent, p. 26). Yet at the very center of our jury

system is the assumption that instructions are followed.

Cf. Spencer v. Texas, supra, at 565 (1967). If that

assumption were abandoned, the entire system of jury

trials and appellate review would lie without foundation.

Furthermore, even if the Court, laying aside that basic

assumption underlying our jury system, were to assume

that instructions to juries regarding the death penalty

would be ignored, Due Process would nonetheless com

pel the State of Arkansas to remove its imprimatur from

the lawless acts of its juries. Compare, Griffin v. Cali

fornia, 380 U.S. 609, 614 (1965). If Arkansas jurors

were told by the court, either expressly or by fair

implication from its submission of criteria, that they

could not kill on account of race, the State would at

least have obtained, at virtually no cost, some distance

from the suspicion of discrimination. When it fails to do

so, it seems to many fair minded observers to condone

racially motivated executions.

33

The Arkansas procedure thus feeds the most corrosive

suspicions one can entertain about a legal system, surely

outranking, in its capacity to produce distrust and disre

spect for law, the use of forced confessions or illegal

searches to obtain convictions, and other practices which

this Court has condemned and for which it has fashioned

prophylatic rules to protect constitutional rights.

D.

The standards for imposition of the death penalty

which Due Process and Equal Protection require are

readily available.

We have shown three ways in which the Arkansas

delegation, without standards, of the power to select a

few persons for capital punishment violates fundamental

constitutional norms. The basic ingredient of standards

which is absent from the California procedure could

easily be supplied. The Model Penal Code, for example,

which establishes prerequisite findings and enumerates

aggravating and mitigating circumstances (American Law

Institute, Model Penal Code, Section 210.6, pp. 128-

132), gives definite standards and informs the jury, by

clear implication, that it may not impose the death

penalty for any other reasons—not because of skin color,

nor of social standing, nor of economic condition. But

as in Giacco, this Court is not called upon to determine

what the particular criteria must be—only that there

must be some definite criteria set by every State which

chooses to authorize its juries to select those upon „

whom capital punishment is to be imposed.

14

II

THE SINGLE-VERDICT PROCEDURE COMPOUNDS THE

VICES OF STANDARDLESS SENTENCING AND IMPOSES

NEEDLESS AND IMPERMISSIBLE BURDENS ON THE RIGHT

TO A FAIR TRIAL ON THE ISSUE OF GUILT OR INNO

CENCE.

As petitioner has amply shown (Petitioner’s Brief, at

pp. 66-78), a defendant in a capital case in Arkansas is

faced with a grisly choice. He is permitted to adduce

mitigating evidence on the penalty question only at the

price of surrendering his right to a full and fair trial on

the issue of guilt and his right not to incriminate himself.

This is enough to invalidate the procedure. Yet the

choices are even grislier than petitioner suggests. If an

Arkansas rape defendant really fears that his life will be

forfeit and is bent on saving it, he may be well advised not

merely to surrender his right not to testify, and to forego

the defense of consent and other trial rights, but also to

yield his very right to be tried. Only by pleading guilty

can he maximize his chances of saving his life.

Even leaving out of account (which the Court should

by no means do) the widespread practice of guilty plea

bargaining, the Arkansas defendant who pleads guilty,

although not thereby absolutely immunizing himself (in

absence of a plea bargain to that effect) from the death

sentence, as in United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570

(1968), will nonetheless have purchased a sentencing jury

which is entirely uncontaminated by the trial of guilt2 —

2 If an Arkansas defendant pleads guilty to rape, empanelment

of a jury to fix the sentence is mandatory. Searber v. State, 226

Ark. 503, 291 S.W. 2d 241 (1956).

15

one which hopefully will hear and sift his mitigating evi

dence with a relatively sympathetic ear. The defendant

who pleads guilty will not, after all, have “compounded

his offence” by denying it. His one and only appearance

before the jury will be in the role of a repentent sinner.

The evidence and arguments he adduces will not be con

tradicted, watered down, confused, or compromised by

the trial of guilt. His chances of living may be enhanced

manyfold. The choices open, and the pressures at work,

are not, therefore, different in kind from those in Jackson.

Here, as in Jackson, the procedure for assessing the death

penalty needlessly burden the exercise, not only a Fifth

Amendment rights, but also of the Sixth Amendment

right to a trial on the question of guilt.3

The Court’s recent decision in North Carolina v. Pearce,

supra, re-emphasized the importance of insulating the ex

ercise of constitutional rights against pressures to forego

them. In Pearce, the Court held that the danger to the

free exercise of both constitutional and non-constitutional

rights—the constitutional right to seek a fair trial and

3It is of no consequence that the petitioner resisted the pres

sures to yield his right to a trial which are inherent in the Arkansas

system. The petitioner in Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609

(1965), also resisted the temptation to surrender his right not to

testify, which was produced by the threat of comment thereon, yet

his conviction and sentence were reversed; and the defendants,

Pearce and Rice, in North Carolina v. Pearce, supra, also withstood

the pressures against taking an appeal, which was produced by the

risk of an increased sentence at a second trial, yet their sentences

were reversed. Petitioner Maxwell, like Griffin, Pearce and Rice,

paid the price of resistance. In Griffin, the price was adverse com

ment and its potential effect on conviction; in Pearce, the price was

the increased sentence. In Maxwell’s case, the price was a sentenc

ing jury which was potentially contaminated, inflamed, and prej

udiced by the trial o f guilt.

16

the non-constitutional right to appeal or collateral attack

-inherent in the possibility of a heavier sentence upon re

trial must be minimized by judicial articulation of a basis

for any such heavier sentence which excludes impermis

sible penalization. Explicit findings were held necessary

to assure prospective appellants or petitioners that they

run no risk of being penalized for the exercise of their

rights.

The Arkansas capital defendant who resists the pres

sures to plead guilty faces a trial on the issues of guilt,

and, if found guilty, punishment, at which he is guaran

teed both constitutional and non-constitutional rights.

But given the unlimited capital sentencing discretion con

ferred by Arkansas law, he exercises these rights at his

grave peril. He may be sentenced to death for any reason

the jury chooses (or for different reasons the individual

jurors choose); and the reasons for his enhanced sentence

remain silent, unconfrontable and unreviewable. He may

be sentenced to death because he did not take the wit

ness stand or because he did take the stand (and claimed

the prosecutrix in a rape case consented), or because he

raised the defense of insanity or because he failed to raise

it. Indeed, every trial decision whether to exercise his

substantial rights, requires a “guess and a gamble,” Whitus

v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964), in which the

stakes are his life, for the jury may choose to kill him for

pursuing his rights.

True, every trial on the issue of guilt entails risks in the

choice of trial tactics, but the defendant is not placed “in

the dilemma of making an unfree choice,” North Caro

lina v. Pearce, supra, 395 U.S., at 724 (quoting from Wor

cester v. Commissioner, 370 F.2d 713, 718), for with re

17

spect to guilt the defendant knows that the jury would

be instructed what to consider and often what not to

consider. See Griffin v. California, supra. But the Ar

kansas single-verdict standardless capital sentencing pro

ceeding intertwines and confuses the issues of guilt and

penalty while allowing the jury free reign to condemn the

defendant for any reason at all. So that not only is the

capital defendant placed in a position where trial on the

issue of guilt conflicts with trial on the issue of penalty,

but also in deciding on how to proceed in trying these

issues he is confronted with choices which entail the ex

ercise or relinquishment of guaranteed rights while fore

warned that the jury is free to make death the price.

Mr. Justice Black stated the pertinent principles in

North Carolina v. Pearce.

[A] State cannot permit appeals in criminal cases

and at the same time make it a crime for a con

victed defendant to take or win an appeal. That

would plainly deny due process of law . . . . [T]he

very enactment of two statutes side by side, one

encouraging and granting appeals and another mak

ing it a crime to win an appeal, would be contrary

to the very idea of government by law. It would

create doubt, ambiguity, and uncertainty, making

it impossible for citizens to know which one of the

two conflicting laws to follow, and would thus vio

late one of the first principles of due process.” 395

U.S. at 724-725 (Black, J., concurring and dissent

ing)

The State of Arkansas has afforded the capital defend

ant numerous rights in his defense, many guaranteed by

the federal constitution, but the “State . . . has made it a

crime,” Ibid, punishable by death at the discretion of the

jury to exercise those rights. And, as Mr. Justice Black

18

has pointed out, for the State to confront a defendant

with such a dilemma is “contrary to the very idea of

government by law. It . . . create[s] doubt, ambiguity,

and uncertainty, making it impossible to know which one

of the two conflicting laws to follow” . Ibid. And what

Mr. Justice Black concluded in the context of a State’s

permitting appeals while at the same time taxing the exer

cise of the right to appeal is applicable here as well: It

“violatefs] one of the first principles of due process.”

Ibid.

The similarity of this case to Jackson, Griffin, and

Pearce makes clear that petitioner, in asking the Court to

invalidate the standardless unitary trial as it exists in

Arkansas, asserts no novel principles. He seeks only

plainly warranted relief from a procedure which is

destructive of a constellation of well established and

most fundamental constitutional rights.

The decision of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit should be reversed.

CONCLUSION

Berl I. Bernhard

William T. Coleman, Jr.

Samuel Dash

John W. Douglas

Steven Duke

William T. Gossett

John Griffiths

Mrs. Rita Hauser

George N. Lindsay

Burke Marshall

Monrad S. Paulsen

Steven R. Rivkin

Whitney North Seymour

Jerome J. Shestack

Cyrus R. Vance

James Vorenberg

Amici Curiae

19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Brief for

the Amici Curiae have been served by mail, postage pre

paid, this 24th day of October, 1969, upon counsel for

the respondent, Joe Purcell, Attorney General of Arkan

sas, Department of Justice, Little Rock, Arkansas, 72201,

and on counsel for the petitioner, Michael Meltsner, 10

Columbus Circle, New York, New York, 10019.

fieri I. Bernhard