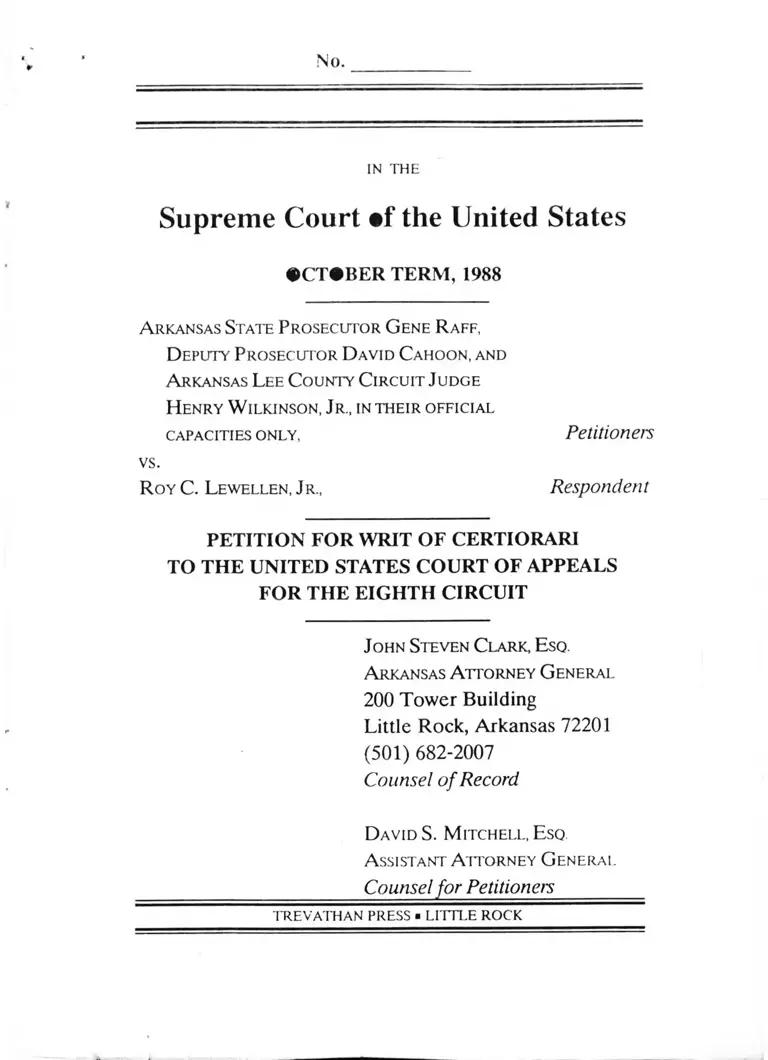

Raff v. Lewellen Jr. Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Raff v. Lewellen Jr. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1988. 81fde2bd-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/31a72e04-d8b4-46c4-9c99-c536a40f8385/raff-v-lewellen-jr-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court »f the United States

•CT#BER TERM, 1988

A rkansas State P rosecutor G ene R aff,

D eputy Prosecutor D avid C ahoon, and

A rkansas L ee C ounty C ircuit Judge

H enry W ilkinson, Jr., in their official

capacities only, Petitioners

vs.

R oy C. Lewellen, Jr., Respondent

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

John Steven C lark, E sq.

A rkansas A ttorney G eneral

200 Tower Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 682-2007

Counsel of Record

D a v idS. M itchell, Esq

A ssistant A ttorney G eneral

Counsel for Petitioners_____

TREVATHAN PRESS • LITTLE ROCK

I

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

WHETHER A FEDERAL COURT MAY ENJOIN A

PENDING STATE COURT CRIMINAL PROS

ECUTION BASED UPON THE “BAD FAITH”

EXCEPTION TO THE YOUNGER ABSTENTION

DOCTRINE WITHOUT CONSIDERING THE

STRENGTH OF THE STATE’S EVIDENCE OR THE

SERIOUSNESS OF THE CHARGES.

II.

WHETHER THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ERRED IN

HOLDING THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDINGS

SUFFICIENT TO ENJOIN A PENDING STATE

FELONY PROSECUTION.

II

PARTIES BELOW

Petitioners Prosecutor Gene Raff, Deputy Prosecutor

David Cahoon, Arkansas Lee County Circuit Judge

Henry Wilkinson, Jr., in their individual and official

capacities; Lafayette Patterson; Jeanne Kennedy;

Arkansas State Trooper Doug Williams; Lee County,

Arkansas; Arkansas Lee County Sheriff Robert May, Jr.;

Robert Banks; Margie Banks; Reverend Almore Banks;

and Respondent Roy C. Lewellen, Jr.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

PARTIES B E L O W .................................... . . i

TABLE OF CONTENTS............................. ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES....................................

OPINIONS B E L O W ...................................

JU RISD ICTIO N .....................................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................... !

REASON FOR GRANTING THE W RIT.................. -

This Court should grant certiorari and reverse

the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals because its

interpretation of the “bad faith” exception to

the Younger abstention doctrine conflicts with

every other Circuit Court decision to address

the same issue as well as the decisions of the

United States Supreme Court. Furthermore the

issue to be addressed is of great constitutional

magnitude and extreme public importance.

CONCLUSION .

APPENDIX

Eighth Circuit Order

April 4, 1988

............... 26

A 1 - A 38

IV

U.S. District Court Order

December 8, 1986 ........................ A 39 - A 51

Eighth Circuit Order on Petition for Rehearing

Ju‘y 14> 1988 ...............................A 52 - A 62

Eighth Circuit Order on Petition for Rehearing

and on Petition for Rehearing En Banc

September 28, 1988 ..............................A 63

Order of United States Supreme Court

Extending Time to File Petition

for Certiorari, October 12, 1988 . . . . A 64

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Allee v. Medrano, 416 U.S. 802, (1974).............8

Bonner v. City of St. Louis, Mo.,

526 F.2d 1331 (8th Cir. 1 9 7 5 )............... 17

Boyle v. Landry, 422 F.2d 631

(7th Cir. 1970)................................................9

Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968) . . . . 8

Central Avenue News, Inc. v. City of Minot,

651 F.2d 565 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 1 ).................... 8

Dataphase Systems, Inc. v. C. L. Systems, Inc.

640 F.2d 109 (8th Cir. 1981)................... 9

Deakins v. Monaghan, 108 S.Ct. 523 (1988) . . . . 20

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965).......... 8

Peas ter v. Miksch, 846 F.2d 21 (6th Cir. 1988) . . . 20

Fitzgerald v. Peek 636 F.2d 943 (5th Cir.)

cert, denied, 452 U.S. 916 (1981)................8

Heimbach v. Village of Lyons, 597 F.2d 344

(2d. Cir. 1979)................................................. ....

Honey v. Goodman, 432 F.2d 333

(6th Cir. 1970) .............................................. ....

Kugler v. Helfant, 421 U.S. 117 (1974) . . . . 8

Ledesma v. Perez, 401 U.S. 82 (1971)................. 8

Lewelien v. Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229

(E.D. Ark. 1986).................................................

VI

Lewellen v. Raff, 843 F.2d 1103 (8th Cir. 1988) . . . 2

Lewellen v. Raff 851 F.2d 1108 (8th Cir. 1988) . . . 2

Munson v. Janklow, 563 F.2d 933

(8th Cir. 1 9 7 7 )...............................................8

Ohio Civil Rights Commission v. Dayton Christian

Schools, 477 U.S. 619, 347 S.Ct. 2718,

(1 9 8 6 ) ............................................................ 17

Samuels v. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66 (1971) . . . 20

Smith v. Hightower, 693 F.2d 359

(5th Cir. 1 9 8 2 ) ................................................. 7

Timmerman v. Brown, 528 F.2d 811

(4th Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) .................................................8

University Club v. City of New York,

842 F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1 9 8 8 ) ..................... 17

Wichert v. Walter, 606 F. Supp. 1516

(D.N.J. 1 9 8 5 )................................................ 10

Williams v. Red Bank Board of Education,

662 F.2d 1008 (3d Cir. 1981) . . . 8

Wilson v. Thompson, 593 F.2d 1375

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 9 ).................................................9

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 . . . . 8

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).................................................2

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ......................................................4

42 U.S.C. § § 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, 1988 ................. 4

Ark. Code Ann. § 5-53-108 (1987).......................4

IN THE

Supreme Court Of The United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1988

A rkansas State Prosecutor G ene R aff,

D eputy P rosecutor D avid Cahoon, and

A rkansas Lee C ounty C ircuit Judge

H enry W ilkinson, Jr., in their official

capacities only Petitioners

vs.

R oy C. L ewellen, J r . Respondent

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Prosecutor Gene Raff, Deputy Prosecutor David

Cahoon, and Arkansas State Circuit Judge Henry

Wilkinson, Jr., petition for a Writ of Certiorari to review

the Judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit.

OPINIONS BELOW

On December 8, 1986, the U.S. District Court for

Eastern District of Arkansas, George Howard, Jr., 649 F.

Supp. 1229, (Appendix pp. A 39-A 51) enjoined

Respondent Lewellen’s state criminal prosecution. On

appeal, a panel of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

affirmed Lewellen v. Raff, 843 F.2d 1103 (8th Cir. 1988)

(Appendix pp. A 1-A 38). The Eighth Circuit Court of

Appeals denied the Petition for Rehearing on July 14,

1988, Lewellen v. Raff, 851 F.2d 1108 (8th Cir. 1988)

(Appendix p. A 63) On September 28, 1988, Petition for

Rehearing was denied as well as Petition for rehearing

rehearing en banc. (Appendix p. A 64) These orders are

reprinted in the Appendix to this Petition.

JURISDICTION

On April 4, 1988, the Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit confirmed the District Court’s preliminary

injunction granted December 8, 1986. The Court of

Appeals denied a petition for rehearing on July 14, 1988,

and on September 28, 1988, it denied a petition for

rehearing and for rehearing en banc. On October 12,

1988, Justice Blackmun granted an extension of time

until November 11, 1988, for petitioners to file petition

for a writ of certiorari. This Court has discretionary

jurisdiction to review this case under 28 U.S.C. § 1254

(!)•

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On September 3, 1985, the rape trial against Rev.

Almore Banks commenced with jury selection. Banks, a

black man, represented by respondent, Roy C. Lewellen,

a black attorney, was charged with raping the eleven year

old daughter of Mrs. Lafayette Patterson, a black

woman. Respondent Lewellen has admitted that two

days following commencement of the Banks trial, he

attempted to negotiate a secret agreement between the

Banks family and Mrs. Patterson whereby Mrs. Patterson

would be paid $500 in exchange for her promise to “drop

the charges.” (T. 557, 558, 559, 563, 843 F.2d 1107 n.4,

1108). Mrs. Patterson had previously been identified as a

state’s witness against Banks. When Mrs. Patterson later

announced it was not up to her to “drop the charges,”

Lewellen told her:

See, it’s up to you in the sense that if you and

your child don’t come up here, then they’re

going to drop it. They can’t make you come to

no courtroom and testify to nothing. I don’t give

a shit if they subpoena you. You don’t have

to —you can go up there and say, “I ain’t got

nothing to say.” You understand? Huh?

843 F.2d at 1108. Unbeknownst to Lewellen, the

conversations were recorded by State Trooper Doug

Williams.

On September 27, 1985, the petitioning

prosecutors, having received the state police

investigative report, including the tapes and Mrs.

Patterson’s statement, charged Lewellen and Rev. Banks

with witness bribery and conspiracy to commit witness

bribery. On that date Municipal Judge Dan Felton, III,

not a party to this case, reviewed the information and

found probable cause existed to support these felony

charges. Most of the facts leading up to the prosecutors’

decision to initiate Lewellen’s prosecution are set out in

the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals’ April 4, 1988,

order, Lewellen v. Raff, 843 F.2d at 1105-08, (Appendix

pp. A 1-A 38). The Arkansas witness bribery statute, to

which Lewellen makes no constitutional challenge, is

reproduced at 843 F.2d 1107 n.5 (Appendix p. A 12).

On April 28, 1986, on the eve of Lewellen’s state

criminal trial, Lewellen brought suit in Federal Court

against these state government officials pursuant to 42

U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, and 1988 claiming they

had conspired to prosecute him due to his race and in

retaliation of his exercise of federally protected

constitutional rights. Jurisdiction in the Federal District

Court was invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1343.

Following extensive discovery, on November 14,

1986, the district court temporarily restrained Lewellen’s

state criminal trial. On November 24, 1986, the district

court began conducting a lengthy hearing on Lewellen’s

4

motion for a preliminary injunction, as well as on the

defendant’s numerous motions for summary judgment.

On December 8, 1986, after hearing six and one-half

days of testimony and other evidence over a 12-day

period the district court entered a preliminary injunction

to the state criminal prosecution. Lewellen v. Raff, 649 F.

Supp. 1229 (E.D. Ark. 1986). The trial court found that

the prosecution was initiated in retaliation for Lewellen’s

vigorous defense of his client, Rev. Banks. Lewellen v.

Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229, 1232 (E.D. Ark. 1986); Lewellen

v- Raff, 843 F. 2d 1103, 1110 (8th Cir. 1988); (Appendix

at pp. A 1-A 38). The District Court never mentioned

Lewellen’s admitted incriminating statements which,

along with the testimony of Mrs. Patterson, served as the

basis for the charges against him. On appeal the Eighth

Circuit affirmed the preliminary injunction, holding:

we find that the district court’s finding of a

retaliatory prosecution is not clearly erroneous,

we therefore need not and do not address the

issue of whether the prosecutors entertained a

reasonable expectation of obtaining a con

viction of Lewellen.

843 F. 2d at 1112. Later, in denying the petition for

rehearing on July 14, 1988, the Eighth Circuit again held

the strength of the evidence against Lewellen was

irrelevant, stating:

to obtain a preliminary injunction in this

context the plaintiff need only show the

prosecution was motivated in part by a purpose

to retaliate against constitutionally protected

conduct.

851 F.2d at 1110 (emphasis added), (Appendix, p. A 60).

6

ARGUMENT

WHETHER A FEDERAL COURT M AY ENJOIN A

PENDING STATE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

BASED UPON THE “BAD FAITH” EXCEPTION TO

THE YOUNGER ABSTENTION DOCTRINE WITH

OUT CONSIDERING THE STRENGTH OF THE

STATE’S EVIDENCE OR THE SERIOUSNESS OF

THE CHARGES.

The pivotal issue in this case turns on the nature

and quantum of proof necessary to enable a federal

court to override Younger and enjoin an ongoing state

felony prosecution. Under the newly crafted Eighth

Circuit rule, a state criminal defendant may circumvent

Younger by merely establishing that his prosecution was

motivated “in part” by an allegedly improper retaliatory

purpose. 851 F. 2d at 1110. That is all that the Eighth

Circuit requires. Contrary to the positions taken by other

circuits, the Eighth Circuit does not require proof that

the alleged improper purpose was a “substantial” factor,

much less a “major motivating factor.” Cf Smith v.

Hightower, 693 F. 2d at 367 (retaliation must be a “major

motivating factor” and play “a prominent role in the

decision to prosecute”). Nor does the strength of the

State’s case against the criminal defendant have any role

in the Eighth Circuit’s analysis. Instead, under the new

Eighth Circuit test, a state prosecution motivated “in

part” by an improper purpose may be enjoined pendente

lite no matter whether the evidence of the criminal

defendant’s guilt is overwhelming. Because the Eighth

Circuit’s test so drastically strays from the principles

announced in Younger, review should be granted by this

Court.

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT’S LEGAL STANDARD

FAILS TO INCLUDE CONSIDERATION OF THE

STRENGTH OF THE STATE’S EVIDENCE OR

SERIOUSNESS OF THE CHARGES.

By authorizing the entry of a federal preliminary

injunction to a pending state court criminal prosecution

without determining whether there is a reasonable

expectation of obtaining a valid conviction or

considering the strength of the state’s evidence, the

Eighth Circuit’s recent decisions conflict with decisions

of the United States Supreme Court and all other

circuits that have addressed the issue. Younger v. Harris,

401 U.S. 37, 48 (1971); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S.

479 (1965); Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611, 621

(1968); Kugler v. Helfant, 421 U.S. 117, 126 n.6 (1975);

Ledesma v. Perez, 401 U.S. 82, 85 (1971); Allee v.

Medrano, 416 U.S. 802, 819, (1974); Munson v. Janklow,

563 F.2d 933, 935 (8th Cir. 1977; Central Avenue News,

Inc. v. City of Minot, 651 F.2d 565, 570 (8th Cir. 1981);

Heimbach v. Village of Lyons, 597 F.2d 344, 347 (2d Cir.

1979); Williams v. Red Bank Board of Education, 662 F.2d

1008, 1022 n.14 (3d Cir. 1981); Timmerman v. Brown, 528

F.2d 811, 815 (4th Cir. 1975); Fitzgerald v. Peek, 636 F.2d

8

943, 945 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 916 (1981);

Smith v. Hightower, 693 F.2d 359, 370 (5th Cir. 1982);

Wilson v. Thompson, 593 F.2d 1375, 1387 n.22 (5th Cir.

1979); Honey v. Goodman, 432 F.2d 333, 344 (6th Cir.

1970); Boyle v. Landry, 422 F.2d 631, 633 (7th Cir. 1970).

In essence, the Eighth Circuit has ignored the prose

cutor’s contentions that Lewellen’s incriminating tape-

recorded statements and the testimony of his primary

accuser, Mrs. Lafayetta Patterson, provide a reasonable

basis for the prosecutors to expect that Lewellen could

be convicted. Indeed, the Eighth Circuit’s new standard

renders such proof wholly irrelevant for purposes of

determining whether a preliminary injunction should

issue.

The Eighth Circuit attempts to legitimize its refusal

to address the State’s more than ample evidence against

Lewellen by creating a tenuous and unprecedented

standard of proof to enjoin preliminarily, as opposed to

permanently, a pending state prosecution. The holding

constitutes a radical departure from the precedents

above.

Petitioners submit that the Eighth Circuit erred in

failing to employ Younger abstention as a threshold

jurisdictional issue to be addressed in addition to

employment of the general preliminary injunction

standard. See Dataphase Systems, Inc. v. C.L. Systems,

Inc., 640 F.2d 109, 114 (8th Cir. 1981). Oddly enough, in

9

its first opinion, see 843 F.2d at 112 n.10, the Eighth

Circuit invoked Judge Sarokin’s decision in Wichert v.

Walter, 606 F. Supp. 1516 (D.N.J. 1985) to sustain the

injunction issued below. Yet Judge Sarokin held

Younger's jurisdictional hurdle applicable, even at the

preliminary injunction stage, stating at 606 F. Supp.

1519:

Where the preliminary relief requested is an

injunction against state disciplinary pro

ceedings, the litigant must also demonstrate [in

addition to the general preliminary injunction

standard] that the threatened harm to him is

egregious enough to surmount the jurisdictional

hurdle of Younger v. Harris (citations omitted)

and its progeny.

Judge Sarokin further noted that Younger’s jurisdictional

hurdle includes a showing the prosecutions were “not

made with any expectation of securing valid convictions.”

Id. at 1520 (quoting Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 48

(1971) (quoting Dombrowski, 380 U.S. 479, 482 (1965)).

The Eighth Circuit’s distinction between a

preliminary and a permanent injunction, never

recognized by this Court, allows the “bad faith”

exception to the Younger doctrine to swallow the rule.

This Court has repeatedly and consistently imposed a

heavy burden upon a federal court plaintiff seeking to

interfere with pending state court proceedings without

10

regard as to whether it he by preliminary or permanent

injunction. Dombrowski, 380 U.S. 479 (1965); Cameron,

390 U.S. 611; Younger, 401 U.S. 37, 48 (1971); Kugler,

421 U.S. 117, 126 n.6 (1975). The practical effect of a

Younger “bad faith” preliminary injunction is the same as

that of a permanent injunction—to forever bar the state

criminal prosecution.

Other decisions do not recognize the Eighth

Circuit’s distinction. See Boyle v. Landry, 422 F.2d 631

(7th Cir. 1970) (applying same standards without regard

to whether by preliminary or permanent injunction);

Honey v. Goodman, 432 F.2d 333 (6th Cir. 1970)

(injunction relief available only where the state instituted

proceedings in bad faith with no real hope of ultimate

success). See also Central Avenue News, Inc. v. City of

Minot, 651 F.2d 565, 570 (8th Cir. 1981) (federal

interference with pending state criminal proceedings

justified only where shown the lack of a reasonable

expectation that valid convictions will result); Munson v.

Janklow, 563 F.2d 933 (8th Cir. 1977) (dismissal of

injunction relief claim upheld where plaintiff failed to

allege prosecution brought without a reasonable expec

tation of obtaining a valid conviction).

IMPORTANCE

The Eighth Circuit’s standard ignores the deeply

entrenched constitutional principles of comity and

Federalism. Should the Eighth Circuit’s standard be

11

allowed to stand, virtually no state prosecution will be

free from the threat of federal court interference. The

present case, where the federal court has already

enjoined Lewellen’s prosecution for almost two years,

classically underscores why Younger's “bad faith”

exception should be parsimoniously applied even at the

preliminary injunction stage. Moreover, where, as here,

the preliminary injunction hearing involved six and one-

half days of testimony following more than six months of

extensive discovery, the Federal Court must not hold

plaintiff to such lenient standard of proof to demonstrate

the impermissible motivation behind the prosecution

while simultaneously ignoring the most salient and

relevant evidence in the record, the state’s evidence

supporting the decision to prosecute.

By lowering the quantum of proof necessary to

establish “bad faith” and simultaneously disregarding the

state’s proof against the accused, the Eighth Circuit test

ignores the severe impact that even a preliminary

injunction can have on a state criminal prosecution.

After years of delay, witnesses’ memories fade, evidence

grows stale, complaining parties’ fervor subsides, and

witnesses may move away, die, or otherwise become

unavailable. Political pressure placed upon a state

prosecutor as a result of a federal court preliminarily

enjoining him from prosecuting due to his alleged “bad

faith” virtually assures that the prosecution will be

permanently abandoned. Even if the district court

ultimately denied a permanent injunction in the case at

12

bar, the state’s ability to prosecute Lewellen has already

been crippled.

The rule fashioned by the Eighth Circuit carries

other equally unpalatable consequences. For example,

under the guise of carrying out discovery in the federal

proceeding, Lewellen, over petitioners’ objections, has

been afforded the opportunity to rigorously interrogate

the state’s witnesses against him, which would otherwise

be prohibited under Rule 17 of Arkansas Rules of

Criminal Procedure. Lewellen’s primary accuser,

Lafayetta Patterson, and the investigating officers have

been subjected to hours of examination in depositions

and in federal court. Few complaining witnesses in state

criminal prosecutions could have withstood the intense

pressure placed upon Mrs. Patterson, after being sued in

this case for damages, particularly after the federal court

has refused to abstain from exercising jurisdiction. In

short, the ill effects of an injunction that Younger foresaw

have already been visited upon the State even though the

injunction entered was technically pendente lite.

Should the preliminary injunction not be reversed,

Lewellen will be afforded still another hearing for a

permanent injunction where he may further interrogate

the state’s witnesses against him. Even if a permanent

injunction is ultimately denied and the prosecution

found to have been brought in good faith, the state will

have to await, in essence, a third trial before having the

opportunity to present in state court the strong evidence

13

of Lewellen’s criminal violation.

Twenty years ago, this Court observed, “the issue

of guilt or innocence is for the state court at the criminal

trial; the State [is] not required to prove appellants guilty

in the federal proceeding to escape the finding that the

State had no expectation of securing valid convictions.”

Cameron, 390 U.S. at 621, 88 S.Ct. at 1341.

Notwithstanding this admonition, the Eighth Circuit has

virtually decided Lewellen’s innocence even though

there was no finding his prosecution was brought with

“no expectation of conviction[s] but only to discourage

the exercise of protected rights.” Cameron, 390 U.S. at

621 (emphasis added); Boyle, 422 F.2d 631, 633 (7th Cir.

1970).

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT TEST IS ERRONEOUSLY

APPLIED

Relying on a trilogy of Fifth Circuit cases, Wilson v.

Thompson, 593 F.2d 375 (5th Cir. 1979); Fitzgerald v.

Peek, 636 F.2d 943 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 916

(1981); Smith v. Hightower, 693 F.2d 359 (5th Cir. 1982),

the Eighth Circuit’s second Order held:

[T]o obtain a preliminary injunction in this

context the plaintiff need only show that the

prosecution was motivated ‘in part’ by a

purpose to retaliate against constitutionally

protected conduct.

14

851 F.2 at 1110 (emphasis added). The dangerous aspect

of this rule is that every criminal defendant who has any

ties to local politics or who is otherwise outspoken on

political issues can derail his state prosecution by

claiming that a witness, investigator, prosecutor, or judge

is aligned with a political opponent.

Thus, despite its reference to the Fifth Circuit

decisions, the Eighth Circuit has created a truncated

version of the Fifth Circuit test that omits reference to

critical components employed in the very cases upon

which the Eighth Circuit relies. Contrary to the Eighth

Circuit’s interpretation, the Fifth Circuit’s approach

requires consideration of evidence of a criminal viola

tion in granting a preliminary injunction, Hightower, 693

F.2d at 370 n.27. Moreover, the Fifth Circuit recognized

in Hightower that a plaintiff must show more than that

his prosecution was motivated in part by retaliation,

instead, he must prove that retaliation is a major

motivating factor:

We conclude the Wilson court did not mean

that any showing of retaliation was sufficient

evidence to meet the plaintiffs burden, because

this would conflict with the holding of Younger

that injunctions of state court proceedings are

to be granted only in narrow circumstances. In

stating that the plaintiff must prove retaliation

exists before a preliminary injunction will be

granted, the Wilson court contemplated that the

15

plaintiff must prove retaliation was a major

motivating factor and played a prominent role

in the decision to prosecute.

693 F.2d at 367 (emphasis added). The second Eighth

Circuit opinion reasons that, at the preliminary

injunction stage, only the first two prongs of the three-

part Fifth Circuit test are applicable. However,

Hightower makes clear that the “strength of the evidence

and the seriousness of the charges” may even prevent

plaintiff from carrying his heavy burden on the second

(retaliation) prong. Id. at 370 n.27.

Contrary to the suggestion in the second Eighth

Circuit opinion, 851 F.2d at 1109 (Appendix A 61) the

state does not contend that Fitzgerald has been overruled

by Hightower. Rather, Fitzgerald, Wilson and Hightower

all require the federal court to consider the strength of

the evidence and seriousness of the charges to determine

whether plaintiff has carried his heavy burden on the

retaliation prong (second prong) as well as the third

prong:

Strong evidence of criminal activity weakens the

finding of retaliation and may prevent the

plaintiff from carrying his heavy burden on the

retaliation prong. If the plaintiff establishes his

case for retaliation, the strength and the

seriousness of the charges remains relevant in

determining if the prosecution would have been

16

brought anyway under the third prong of

Wilson.

Hightower, 693 F.2d at 370 n.27.

According to the Eighth Circuit, Fitzgerald's

conclusion that a showing of bad faith “will justify an

injunction regardless of whether a valid conviction

conceivably could be obtained,” 636 F.2d at 945

(emphasis added), means that a criminal defendant may

circumvent Younger without proving that there is

reasonable expectation of his conviction. However, the

language in Fitzgerald is not inconsistent with requiring

plaintiff to show there is no reasonable expectation of

conviction. Requiring a showing a conviction is

inconceivable is a much more onerous burden than

merely requiring a showing it cannot be reasonably

expected. Contrary to the Eighth Circuit’s holding, the

state has a legitimate interest in pursuing a criminal

prosecution like Lewellen’s, brought with full probable

cause, regardless of whether it is proven to be motivated

“in part” by some impermissible purpose.

LEWELLEN HAS AN ADEQUATE REMEDY IN

STATE COURT

The Eighth Circuit has not required Lewellen to

carry his heavy burden of showing Arkansas law fails to

provide an adequate legal remedy of which he may avail

himself. See Ohio Civil Rights Commission v. Dayton

Christian Schools, A ll U.S. 619, 106 S.Ct. 2718, 2723-24

17

(1986); University Club v. City of New York, 842 F.2d 37,

40-42 (2d Cir. 1988); Bonner v. City of St. Louis, Mo., 526

F.2d 1331, 1335 (8th Cir. 1975). A federal court cannot

indulge in the assumption that the state trial and

appellate courts are incapable of fairly adjudicating

plaintiff’s claim that the state court systematically

conspires to harass, intimidate, coerce, discriminate, and

deny equal protection to black citizens. Id. at 1337. In

Bonner, the Eighth Circuit held such allegation,

analogous to those made by Lewellen, insufficient to

state a claim with the narrow exception to Younger.

The only claim the Eighth Circuit has questioned

whether Lewellen can adequately raise in state court in

defense of the witness bribery charge is his First

Amendment claim regarding the scheduling of his

criminal trial. 843 F.2d at 1112 n.9. However, this finding

is irrelevant to the issue of whether to enjoin his

prosecution since: (1) Lewellen’s claim here is not based

on why his prosecution was brought, but rather, why his

trial was scheduled when it was; and (2) the fact that

Lewellen was scheduled to be tried after his election

goes against a finding it was calculated to impede his

First Amendment rights.

18

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ERRED IN HOLDING THE

DISTRICT COURT’S FINDING OF A RETALIA

TORY OR “BAD FAITH” PROSECUTION NOT

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS.

Even applying the less stringent Fifth Circuit

standard, the findings of the District Court cannot

support the entry of a preliminary injunction. In both

opinions, the Eighth Circuit has refrained from

addressing the strength of the evidence or the

seriousness of the charges against Lewellen.

The first Eighth Circuit opinion described the

District Court’s opinion as “somewhat cryptic as to the

precise basis for the District Court’s findings [that

prosecution brought in bad faith for the purpose of

retaliation]”. 843 F.2d at 1110 (Appendix A 19). There

the Eighth Circuit went on to state: “Moreover it is of no

significance that the district court’s findings concerning

the impermissible purposes behind the prosecution are

irrelevant to the issue of whether the prosecutors had a

reasonable expectation of obtaining a conviction.” 843

F.2d at 1112 (Appendix A 25). In contrast, the Eighth

Circuit’s second opinion, 851 F.2d at 1110, states the

district court “fully satisfied” Hightower's requirement

that “ ‘the strength of the evidence and the seriousness

of the charges should be considered in determining if

retaliation or bad faith exists,’ 693 F.2d at 369.” The two

findings are irreconcilable.

19

The second Eighth Circuit opinion, after holding it

need not consider the state’s evidence, inconsistently

stated the district court “ reviewed the evidence of

Lewellen’s allegedly criminal activities at length” in

concluding there is no expectation of conviction, 851

F.2d at 1110. However, the district court failed to even

mention Lewellen’s admitted and incriminating

statements (see 843 F.2d 1107 n.4, 1108) or Arkansas’

bribery statute (843 F.2d at 1107 n.5), which serve as the

principal bases for his being charged. In this regard, the

district court found a substantial likelihood that

Lewellen will establish there is no reasonable

expectation of his conviction solely based (1) on the poor

quality and alleged gaps in certain tape-recorded

statements and (2) on its finding that Lewellen would

likely demonstrate that lawyers commonly act as

intermediaries to have criminal charges dropped. 649 F.

Supp. at 1233. The district court’s findings here are

clearly erroneous and fail to satisfy the district court’s

responsibility to scrupulously consider the strength of the

evidence and the seriousness of the charges against

Lewellen.

First, the district court, to support its conclusion,

apparently reasoned that the alleged gaps in Tapes E-2

and E-4 would render them inadmissible in state court by

finding their prejudicial effects . . . outweigh any

probative value.” Id. at 1233. As an initial matter, it is

within the exclusive authority of the state trial court, not

the federal court, to determine the admissibility of

20

evidence in Lewellen’s criminal trial. Samuels v. Mackell,

401 U.S. 66, 72-73 (1971). Thus, the federal district court

improperly reached issues that will determine the

outcome of pending state criminal proceedings. Id.;

Feaster v. Miksch, 846 F.2d 21, 24 (6th Cir. 1988). See also

Deakins v. Monaghan, 108 S.Ct. 523, 533 (1988) (White,

J. concurring) (Younger and Samuels counsel against

federal court’s disposition of Fourth, Fifth and Sixth

Amendment issues due to potential res judicata effect on

state criminal proceeding.) More importantly, however,

Lewellen admitted in federal court that he made all the

incriminating statements upon Tapes E-2 and E-4 and in

fact stipulated that these tapes and the transcript

prepared from them are the best evidence of what

occurred during these conversations (T. 565).

Second, the district court’s finding that Lewellen

could likely demonstrate that lawyers commonly serve as

“intermediaries” to have charges dropped is also

irrelevant and clearly erroneous. Lewellen admitted he

negotiated a secret agreement whereby Mrs. Patterson

would be paid $500.00 in exchange for her agreement to

“drop the charges.” (T. 557, 558, 559, 563; see also Tape

E-2 at 843 F.2d 1107 f.4, and Tape E-4, at 843 F.2d

1108). Lewellen has further admitted that prior to these

conversations he was aware that the prosecutors had

listed Mrs. Patterson and her daughter as witnesses for

the State. (T. 599, 600). The glaring distinction between

Lewellen’s admitted conduct and that of an attorney

serving as an intermediary to have the charges dropped

21

is underscored by his adamant directive to the Banks

family and Ms. Patterson to keep the agreement secret,

especially from the prosecutors and the court:

What we talk about here will never go any

further. That is a solemn word on everybody’s

part, okay?

843 F.2d at 1107, n.4.

If Lewellen was acting as an intermediary, it was

clearly not in cooperation with the prosecutor or the

court to have the charges dropped, but rather to have

Mrs. Patterson bribed. The next day Lewellen made

crystal clear that he was attempting to induce Mrs.

Patterson to refuse to testify, stating to her:

See, it’s up to you in the sense that if you and

your child don’t come up here, then they’re

going to drop it. They can’t make you come to

no courtroom and testify to nothing. I don’t give

a shit if they subpoena you. You don’t have

to -you can go up there and say, “I ain’t got

nothing to say.” You understand? Huh?

843 F.2d at 1108.

THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDINGS WERE

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

The trial court s finding that Lewellen sufficiently

proved his prosecution was retaliatory is clearly

22

erroneous. Lewellen’s three convoluted theories are

supported by nothing more than tenuous chain of

inferences as follows:

A. Evidence The Prosecution Motivated By Lewellen’s

Race

The sole evidence relied upon by the Eighth Circuit

and the District Court to support this allegation is the

testimony of Neal, a black attorney who initiated the

investigation leading to the charges against Lewellen.

Neal, who had never tried a case against either Raff or

Cahoon before a jury, merely testified in his opinion

black attorneys were subjected to disparate treatment by

Raff and Cahoon. There is simply no evidence linking

the motivation behind Lewellen’s prosecution to his

race. Moreover, the district court made no such finding.

B. Evidence Lewellen’s Prosecution Motivated By His

Vigorous Defense of Banks

Where, as here, the prosecutors were presented

with more than ample evidence that Lewellen’s vigorous

defense of Banks included his bribing of the state’s key

witness, they were duty bound to pursue Lewellen’s

prosecution.

The sole evidence to support Lewellen’s theory

here is the disputed testimony of Lewellen and Blount

regarding their conversations with Sheriff May, who had

23

no part in the decision to prosecute. They testified May

suggested Lewellen should apologize for his

unprofessional conduct in the September 9, 1985,

“special proceeding” (T. 278-283, see also 1071). It is

undisputed both Blount and Lewellen considered May a

friend and confidant and sought his advice. At most,

their testimony merely establishes that May advised

Lewellen to apologize and “insinuated” that to do so

might help persuade the prosecutors not to prosecute (T.

277). Most importantly these conversations occurred

after all of Lewellen’s incriminating statements had been

made.

C. Evidence Lewellen’s Prosecution Motivated

By His Political Campaign

There is no evidence that the prosecutors or the

circuit judge even knew of Lewellen’s plans for political

office at the time the charges were brought, or for that

matter if they even cared. To the contrary, Lewellen was

charged in September of 1985, a time when Lewellen

was not even a candidate. (T. 482). Furthermore there is

no evidence that Lewellen’s political opponent was

supported by any defendant in this case. (T. 1061).

The Eighth Circuit’s reliance on the resetting of

Lewellen s trial to November 17, 1986, as evidence that

his prosecution in 1985 was politically motivated is

misplaced. Lewellen had previously secured numerous

continuances of trial dates scheduled before the election.

24

The November, 1986, date was after the election.

Moreover, Lewellen’s trial date was reset over a year

after he was charged with full probable cause and over-

six months after he sought federal court injunctive relief.

Thus, its relevance to whether the charges were brought

in bad faith is highly tenuous.

Lewellen’s purported proof of a retaliatory

prosecution “ is nothing more than a tenuous chain of

inferences unsupported by evidence or reason.” Smith,

693 F.2d at 373. Furthermore, neither the district court

nor either panel opinion mentions or addresses the

seriousness of the bribery charge, a class C felony

punishable by 3 to 10 years imprisonment, as the second

prong in Hightower requires. 693 F.2d 370 n.27. In this

regard the official commentary to Arkansas’s Witness

Bribery Statute, Ark. Code Ann. §5-53-108 (1987),

removes any doubt about the seriousness of the acts

attributed to Lewellen:

To the extent the section reaches a mere offer,

it establishes an inchoate offense. This reflects

the commission’s view that the conduct

described is so deleterious to the administration

of justice that attempts are justifiably graded

with the same severity as the consummated

offense.

25

CONCLUSION

This case classically exemplifies why the

constitutional principles of comity and federalism are so

important in the Younger abstention context even at

preliminary injunction stage. Lewellen has attempted to

manipulate the state criminal justice system by allegedly

bribing the state’s key witness in his client’s rape trial.

Lewellen has successfully manipulated the federal

judicial system to unreasonably delay and possibly bar

his state criminal prosecution. Lewellen’s admitted

statements to Mrs. Patterson, never mentioned by the

district court, are more than ample to support his

conviction for bribeiy. The strong evidence of Lewellen’s

criminal violation supports the inference that in bringing

the charges, the prosecutors were motivated by nothing

more than fulfilling their sworn duty. Hightower, 693 F.2d

at 371. By contrast, the evidence Lewellen presented to

support his allegation that his prosecution was

retaliatory “is nothing more than a tenuous chain of

inferences unsupported by the evidence or reason.” Id at

The state criminal justice system will be severely

handicapped if, as here, federal trial courts allow

criminal defendants to thwart their state court

prosecution based upon such a scant showing the

prosecution is motivated “ in part” by some

impermissible purpose while ignoring the most relevant

26

evidence, the state s evidence of a criminal violation.

The federal court must scrupulously review the strength

of the state’s evidence and the seriousness of the charges

in granting a preliminary injunction to a pending state

criminal prosecution. Id. at 370 n.27. Since the Eighth

Circuit stands alone in refusing to impose this

requirement, certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

John Steven Clark, E sq.

A rkansas A ttorney G eneral

200 Tower Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 682-2007

Counsel of Record

By D avid S. M itchell, E sq.

A ssistant A ttorney G eneral

Counsel for Petitioners

27

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-1069

Roy C. Lewellen, Jr.,

Appellee,

v.

Gene Raff, individually and in

his official capacity as

Prosecuting Attorney for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas; David Cahoon,

individually and in his

official capacity as Deputy

Prosecuting Attorney for Lee

County, Arkansas; Henry

Wilkinson, individually and in

his official capacity as

Circuit Court Judge for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas,

Appellants.

Lafayette Patterson; Jeanne

Kennedy; Doug Williams; Lee

County, Arkansas; Robert May,

Jr., individually and in his

official capacity as Sheriff

of Lee County.

Lafayette Patterson

v.

Robert Banks; Margie Banks;

Reverend Almore Banks.

No. 87-1100

Roy C. Lewellen, Jr.,

Appellee,

v.

Gene Raff, individually and in

his official capacity as

Prosecuting Attorney for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas; David Cahoon,

individually and in his

official capacity as Deputy

Prosecuting Attorney for

Lee County, Arkansas;

A 2

Lafayette Patterson; Jeanne

Kennedy;

Doug Williams,

Appellant.

Lee County, Arkansas;

Robert May, Jr., individually

and in his official capacity

as Sheriff of Lee County;

Henry Wilkinson, individually

and in his official capacity

as Circuit Court Judge for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas.

Lafayette Patterson

v.

Robert Banks; Margie Banks;

Reverend Almore Banks.

No. 87-1101

Roy C. Lewellen, Jr.,

Appellee,

v.

A 3

Gene Raff, individually and

in his official capacity as

Prosecuting Attorney for the

Eastern Judicial District of

Arkansas; David Cahoon,

individually and in his

official capacity as Deputy

Prosecuting Attorney for

Lee County, Arkansas;

Lafayette Patterson; Jeanne

Kennedy; Doug Williams;

Lee County, Arkansas;

Robert May, Jr., individually

and in his official capacity

as Sheriff of Lee County,

Appellant.

Henry Wilkinson, individually

and in his official capacity

as Circuit Judge for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas.

Lafayette Patterson

Robert Banks; Margie Banks;

Reverend Almore Banks.

No. 87-1103

Roy C. Lewellen, Jr.,

Appellant,

v.

Gene Raff, individually and

in his official capacity as

Prosecuting Attorney for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas; David Cahoon,

individually and in his

capacity as Deputy

Prosecuting Attorney for

Lee County, Arkansas,

Appellees.

Lafayette Patterson; Jeanne

Kennedy; Doug Williams; Lee

County, Arkansas; Robert

May, Jr., individually and

in his official capacity as

Sheriff of Lee County;

Henry Wilkinson, individually

and in his official capacity

as Circuit Court Judge for the

First Judicial District of

Arkansas.

Lafayette Patterson

v .

Robert Banks; Margie Banks;

Reverend Almore Banks.

Appeals from the United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Arkansas.

Submitted: October 14, 1987

Filed: April 4, 1988

Before LAY, Chief Judge, ARNOLD and BOWMAN,

Circuit Judges.

LAY, Chief Judge.

At issue is the serious question whether the federal

district court1 erred in not exercising Younger1 2 abstention

by enjoining a criminal prosecution brought by the State

1 The Honorable George Howard, Jr., United States District Judge for the Eastern

District of Arkansas.

" Youn2er v. Harris. 401 U.S. 37 (1971).

of Arkansas against a black attorney in Lee County,

Arkansas. We affirm the grant of the temporary

injunction. We reverse in part the district court’s rulings

on the section 1983 damages claims.

I. Background

On June 7, 1984, Reverend Almore Banks, a black

minister, was charged-with rape in the Circuit Court of

Lee County, Arkansas. The alleged victim was Latonia

Wilbun, the eleven-year-old daughter of Mrs. Lafayetta

Patterson.3 Mrs. Patterson’s husband, Joe Lewis

Patterson, is the brother of Rev. Banks’s wife, Margie

Banks. The Pattersons are also black.

Rev. Banks engaged Roy Lewellen, a black

attorney, to represent him. Mrs. Patterson employed

Oily Neal, also a black attorney, to represent her interest

and the interest of her daughter in the criminal

prosecution. Lee County Prosecutor Gene Raff and

Deputy Prosecutor David Cahoon, both white,

represented the state in the proceeding.

Jury selection in Banks’s trial began Tuesday,

September 3, 1985, with Judge Harvey Yates presiding.

On Thursday, September 5, Neal contacted Deputy

Prosecutor Cahoon to inform him that Mrs. Patterson

was being pressured to “drop the charges” against Banks.

Mrs. Patterson claimed that the pressure was coming

Mrs. Patterson is referred to both as Lafayette and Lafayetta in the record and in

the parties’ submissions.

rom her husband, from Rev. and Margie Banks, and

from Rev. Banks’s brother, Robert.

Mrs. Patterson and others testified about the events

that took place that Wednesday that prompted Neal to

contact the prosecutor. Robert Banks came to the

Patterson house on Wednesday morning and discussed

the pending charges against Rev. Banks with the

Pattersons. The three of them reached an apparent

agreement that if Mrs. Patterson would drop the charges,

Rev. Banks would leave town. Mrs. Patterson, however,

claims that she did not then or ever actually intend to

drop the charges.

Mr. and Mrs. Patterson and Robert Banks then

proceeded to Neal’s office, apparently to have him

prepare a paper documenting their agreement. Margie

Banks somehow was informed of or arranged the

meeting at Neal’s office. She called Lewellen and

informed him that he too should go to Neal’s office,

because Mrs. Patterson was going to drop the charges

against Lewell'en’s client.

When they arrived at Neal’s office, Mrs. Patterson

met privately with Neal. She told him that she in fact had

no intention of dropping the charges. Neal relayed this

information to those assembled in his office. Mr.

Patterson became angry, feeling that his wife had been

steadily lying to him about dropping the charges.

Lewellen left Neal’s office immediately, saying only,

AS

according to Mrs. Patterson, that he thought the family

was going to solve it.

Later that day, after returning home, Mr. Patterson

phoned Margie Banks and told her that Mrs. Patterson

was indeed going to drop the charges. Mrs. Patterson

claims she led her husband to believe this because she

was afraid of him and wanted everyone to leave her

alone. After a series of phone calls, it was arranged that

Lewellen would bring Rev. and Margie Banks to the

Patterson home. Robert Banks was also present at this

meeting. Lewellen did not stay at the meeting.

The parties again reached an apparent agreement

that Mrs. Patterson would drop the charges, Rev. Banks

would leave town, and Mrs. Patterson would be

reimbursed by the Bankses for $500 attorney’s fee she

had incurred by retaining Neal to represent her interests.

Lewellen later returned to pick up his client. He did not

wish to hear what happened at the meeting, stating

something to the effect of, “ look here, if you all are

going to settle this, settle it with your family. I don’t want

to have anything to do with it. I don’t want to know

what’s going on.”

These were the events that, when relayed to Neal,

prompted him to call Deputy Prosecutor Cahoon.

Cahoon then told Prosecutor Raff and Lee County

Sheriff Robert May that he had received information

suggesting that bribes were being offered to Mrs.

Patterson by Rev. Banks to induce her to drop the

charges. At the direction of the prosecutors, May

requested investigatory assistance from the Arkansas

state police. May informed the state pofice that

electronic surveillance equipment might be needed to

conduct the investigation.

Later that day, Sgt. Douglas Williams of the state

police arrived in town to begin assisting in the

investigation, bringing with him his electronic

surveillance equipment. Williams, May, and Cahoon met

with Mrs. Patterson and Neal at the Marianna jail to

discuss Mrs. Patterson’s complaint. Jeanne Kennedy, a

victim s advocate and child abuse and rape counselor,

was also present. Mrs. Patterson was equipped with a

hidden body microphone and directed to engage in

conversation with Mr. Patterson and others to

corroborate her allegations. Although Rev. Banks was an

investigatory target at this point, Lewellen was not.

Mrs. Patterson left the jail, found her husband at

the local ball field, and told him that she would agree to

drop the charges if Rev. Banks left town and the parties

adhered to their agreement of the day before. She also

told him that she wanted a lawyer to draft a document

setting forth Rev. Banks’s agreement to leave town. Mrs. |

Patterson then made a series of phone calls. The

Pattersons’ part of these conversations was recorded by

Sgt. Williams, who operated a receiving and recording

device in a car parked near the Patterson home. The

A 10

tape, referrcil to as “E-l,” contains at least two and

allegedly more gaps in transmission.

That night the Pattersons and the three Bankses

met with Lewcllen at Lewellen’s office. Mrs. Patterson

was still equipped with a body microphone, and the

conversation was recorded.4 Later that night, the tape

The relevant portion of that tape, identified as “ E-2,” contains the following

conversation:

BL [Lewellen]: ♦ * * Reverend, it is the understanding that you and your

wife are going to go somewhere. Is that ya’ll’s understanding?

AB [Rev. Banks]: I’m sticking to my commitment.

BL: The commitment is, and what I have heard her say that what she

wants from you, and that thing being gone. I don’t want you moving

tomorrow. That’s what I’m saying, and because that is going to bring up

some bunch of suspicion, okay? We don’t want that. We need time.

AB: We need time to relocate.

BL: You see, what I am saying and the word and wait, and it is this. What

we talk about here will never go any further. That is a solemn word on

everybody’s part, okay? And I said that because it is not going to do any

one person any good to try to embarrass the other, and it is just going to

raise something else up again, and then we are all in this mess over

again, so if ya’Il are sincere in what your agreement and you are making,

that is fine with me.

MB [Margie Banks]: That’s right. It ain’t nobody’s business.

BL: There was also some understanding that she feels that there is some

reimbursement necessary for attorney fees. That’s what your brother

advises on the telephone. I think you agree to that; is that right?

AB: That’s correct.

BL: Okay, and that is $500.00 and she has both of ya’Il word.

MB: Uh huh. (yes).

BL: That is all to be done, is that right? Is that right, Reverend.

AB: That’s right.

A 11

f 1 *ti |; ijW

was played for Prosecutor Raff at Sheriff May’s home

and transcribed at the office of a private law firm with

which Cahoon was associated. The prosecutors

suggested the need, under the Arkansas witness bribery

statute,5 for further investigation to clarify what

Patterson was being induced to do.

The next day, Sgt. Williams took a statement from

Mrs. Patterson. Because of Raff’s suggestion the night * 1

BL: * * * Like I say, ya’ll know what your agreement are; ya’ll don’t need me,

and that is why I’m telling you that if you are going to work it out, work it

amongst your family so that is what it will be. The least that I have

involvement in it the better because I swear to God, I don’t put nothing past

tolks, and if they ever felt that I was intimidating anybody or trying to

persuade a witness out or something or to do some stuff like that, Gene

Raff and I am going to be honest with you — that white man and me have

mixed up some bad blood these last three days. It has almost gotten down to

some plain out cussing. I mean it has been bad, so anything that he could

right now at this point to use against me or hurt me, he would do it. It has

gotten past a job to him and gotten personal; him and David — it has got past

that, and anything they could do They would send somebody wired up with

tape recorders on them. I ’m serious. I’m telling you, you have to watch it. If

you don t believe it, just ask Jimmie Wilson, cause I ’d always believe they

done put folks on him. I don’t want them with me standing in front of a grand

jury saying I been over there siminating (?) somebody and all that kind of

stuff. That’s what they would do.

The Arkansas witness bribery statute, Ark. Stat. Ann. §5-53-108 (1987) provides

in pertinent part:

(a) A person commits witness bribery if:

(1) He offers, confers, or agrees to confer any benefit upon a witness or

a person he believes may be called as a witness with the purpose of:

(A) Influencing the testimony of that person; or

(B) Inducing that person to avoid legal process, summoning him to

testify; or

(C) Inducing that person to absent himself from an official pro

ceeding to which he has been legally summoned * * *.

A 12

*

before, Mrs. Patterson attempted to reach Lewellen by

telephone. When they eventually spoke, their phone

conversation was recorded. This tape recording,

identified as “E-4,” contained the following statement by

Lewellen:

See, it’s up you in the sense that if you and your

child don’t come up there, then they’re going to

drop it. They can’t make you come to no

courtroom and testify to nothing. I don’t give a

shit if they subpoena you. You don’t have

to —You can go up there and say, “I ain’t got

nothing to say.” You understand? Huh?

Rev. Banks’s rape trial resumed on Monday,

September 9. Before any jurors were called, prosecutors

Raff and Cahoon informed Judge Yates that there was a

matter that they were required to bring to his attention.

They proceeded to place on the record, in closed

proceedings, their outline of the witness bribery

investigation. Mrs. Patterson and Sgt. Williams testified

about the alleged bribery and the investigation. Lewellen

was not allowed to cross-examine these witnesses, nor

did Judge Yates allow Lewellen to present witnesses in

his own or Rev. Banks’s behalf. Lewellen was permitted

only to make a statement addressing the effect of what

had transpired on Rev. Banks’s rape trial.

After a brief recess, Judge Yates sua sponte

declared a mistrial. He also stated that he intended to

A 13

send a transcript of that day’s proceedings to the

Arkansas Supreme Court Committee on Professional

Conduct.

On September 27, Sheriff May executed an

affidavit in support of an information charging Lewellen

and Rev. Banks with witness bribery and conspiracy to

commit witness bribery. That same day, the prosecutors

presented the information to Municipal Judge Dan

Felton, III. Lewellen’s case was placed on the Lee

County Circuit Court criminal docket and set for trial for

February 7, 1986. Upon Lewellen’s motion, his trial was

continued to May 19, 1986.

On April 28, 1986, Lewellen brought suit in federal

court against Prosecutors Raff and Cahoon, Sheriff May,

Sgt. Williams, Lee County, Lafayetta Patterson, and

Jeanne Kennedy. Lewellen later added as a defendant

Judge Henry Wilkinson, who was due to preside over

Lewellen’s criminal trial in Lee County Circuit Court.

Lewellen sought damages and injunctive and declaratory

relief6 under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, and

1988 for alleged violations of his rights under the first,

fourth, fifth, thirteenth, and fourteenth amendments. He

also asserted pendent state law claims. The gist of

Lewellen’s complaint was that the defendants conspired

to and did investigate and prosecute him because of his

race and to retaliate against him for exercising his

constitutional rights.

Lewellen sought only declaratory and injunctive relief against Judge Wilkinson.

After a number of continuances, Lcwellen’s state

criminal trial was finally scheduled for November 17,

1986. On October 27, 1986, Lewellen moved the federal

court for a temporary restraining order to enjoin the

prosecutors and Judge Wilkinson from going forward

with the state criminal trial. The district court granted

this motion on November 14 and set a hearing on

Lewellen’s motion for a preliminary injunction.

Following a six-and-one-half-day hearing, the

district court issued a preliminary injunction barring the

state officials from proceeding with Lewellen’s criminal

trial pending adjudication of Lewellen’s federal court

action on the merits. Lewellen v. Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229

(E.D. Ark. 1986). One week later, on December 15,

1986, the district court ruled on a number of other

motions; these orders, from which various parties

appeal, are discussed in succeeding sections.

II. Discussion

A. Preliminary Injunctive Relief

Prosecutors Raff and Cahoon and Judge Wilkinson

appeal from the district court’s entry of a preliminary

injunction barring them from proceeding with the state

criminal case against Lewellen. For reversal, they argue

that the district court should have abstained from

exercising jurisdiction, pursuant to the principles of

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971). They also argue

A 15

that the district court applied an erroneous legal

standard to determine whether the preliminary

injunction should issue. We turn first to the question of

Younger abstention.

In Younger, the Supreme Court held that federal

courts as a rule abstain from exercising jurisdiction when

asked to enjoin pending state criminal proceedings. Id. at

56.7 The Younger abstention doctrine is a reflection of

the public policy that disfavors federal court interference

with state judicial proceedings. The doctrine is based on

comity and federalism. See Ronwin v. Dunham, 818 F.2d

675, 677 (8th Cir. 1987) (citing Younger, 401 U.S. at 44).

Despite the concerns underlying the Younger

abstention principle, however, in certain cases the duty

of the federal courts to vindicate and protect federal

rights must prevail over the policy against federal court

interference with state criminal proceedings. The federal

courts have consistently and repeatedly affirmed that

their abhorrence of enjoining a pending state pros

ecution must yield when the state prosecution threatens

a party with “great and immediate irreparable injury.”

See, e.g., Younger, 401 U.S. at 56; Dombrowski v. Pfister,

380 U.S. 479, 485-87 (1965); Collins v. County of Kendall,

807 F.2d 95, 98 (7th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct.

In § 1983 cases such as this one, the doctrine is not grounded in the Anti-

Injunction Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2283 (1982), which prohibits federal injunctions

against state court proceedings, because actions brought under § 1983 arc within

the "expressly authorized” exception to the ban on federal injunctions See

Mnchum v. Foster. 407 U.S. 225, 243 (1972). ----

A 16

3228 (1987); Rowe v. Griffin, 676 F.2d 524, 525 (11th Cir.

1982); Fitzgerald v. Peek, 636 F.2d 943, 944 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 452 U.S. 916 (1981); Munson v. Janklow, 563

F.2d 933, 935 (8th Cir. 1977); Timmerman v. Drown, 528

F.2d811, 815 (4th Cir. 1975).

The requisite threatened injury must be more than

simply “the cost, anxiety, and inconvenience of having to

defend against a single criminal prosecution * * *. ”

Younger, 401 U.S. at 46. The injury threatened is both

great and immediate, however, when “defense of the

State’s criminal prosecution will not assure adequate

vindication of constitutional rights,” Dombrowski, 380

U.S. at 485, or when the prosecution is initiated in bad

faith or to harass the defendant. See, e.g., Cameron v.

Johnson, 390 U.S. 611, 617-18 (1968); Central Ave. News,

Inc. v. City o f Minot, 390 U.S.F.2d 565, 568-70 (8th Cir.

1981). In the context, bad faith “generally means that a

prosecution has been brought without a reasonable

expectation of obtaining a valid conviction.” Kugler v.

Helfant, 421 U.S. 117, 126 n.6 (1975); see also Central

Ave. News, 651 F.2d at 570. Bad faith and harassing pros

ecution also encompass those prosecutions that are

initiated to retaliate for or discourage the exercise of

constitutional rights. See, e.g., Younger, 401 U.S. at 48

(Dombrowski defendants were threatened with great and

immediate irreparable injury because prosecutions were

initiated “to discourage them and their supporters from

asserting and attempting to vindicate the constitutional

rights of Negro citizens of Louisiana.”) (quoting

A 17

Dombrowski, 380 U.S. at 482); Heimbach v. Village of

Lyons, 597 F.2d 344, 347 (2d Cir. 1979) (per curiam)

(allegation that state criminal prosecution was initiated

to chill first amendment rights sufficient to remove

Younger bar against federal court interference).

A showing that a prosecution was brought in

retaliation for or to discourage the exercise of

constitutional rights “will justify an injunction regardless

of whether valid convictions conceivably could be

maintained.” Fitzgerald v. Peek, 636 F.2d 943, 945 (5th

Cir. 1981) (emphasis added). The state does not have

any legitimate interest in pursuing such a prosecution;

“[pjerhaps the most important comity rationale of

Younger deference-that of respect for the State’s

legitimate pursuit of its substantive interests —is

therefore inapplicable.” Wilson v. Thompson, 593 F.2d

1375, 1383 (5th Cir. 1979) (citations omitted).

We turn to our review of the district court’s

decision with these principles in mind. We can disturb

the district court s decision only if its factual findings are

clearly erroneous or if it committed an error of law. See

CentralAve., 651 F.2d at 569.

After hearing testimony and receiving documentary

evidence over a six-day period, the district court made

two critical factual findings that persuaded it to issue the

preliminary injunction:

A 18

Lewellen has demonstrated that the criminal

prosecution initiated by Raff and Cahoon

against Lewellen was brought in bad faith for

the purpose of retaliating for the exercise of his

constitutionally protected rights. This Court is

of the opinion that the criminal charges

instituted against Lewellen would not have been

filed absent the desire to retaliate against

Lewellen for exercising his federally protected

rights.

Lewellen v. Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229, 1232 (E.D. Ark.

1986). Although the district court’s opinion is somewhat

cryptic as to the precise bases for these findings, based

on our review of the record, we cannot say that they are

clearly erroneous.

The allegations in Lewellen’s complaint painted a

picture of pervasive racism and discriminatory treatment

of blacks in the Lee County court system. Lewellen

alleged that he, as a black attorney, had received

disparate treatment from that accorded white attorneys

by both the prosecutors and the closely-aligned circuit

court judges. He claimed that the prosecutors initiated

charges against him: (1) because of his race; (2) because

he had vigorously attempted to defend his client, Rev.

Banks, against the rape charge; and (3) because they

wished to thwart Lewellen’s campaign for state office

against a political ally of Sheriff May.

A 19

In support of these allegations, Lewellen presented

the testimony of eight witnesses at the preliminary

injunction hearing. The district court credited the

testimony of Lewellen and Sam Blount, a local

businessman, as supporting the allegation that the

prosecution was initiated because of the prosecutors’

desire to retaliate against Lewellen for his vigorous

defense of Banks. The district court relied on the

following evidence:

Lewellen testified that during the juiy selection

in the rape case he was defending, he objected

to the procedure being employed by the trial

judge and received a strong admonishment

from the trial judge in open court; that later, he

saw the trial judge and Raff eating lunch

together in the Lee County jail and advised the

trial judge that he, Lewellen, wanted to renew

his objections to the jury selection procedure

when the trial resumed. Again the trial judge

harshly rebuked Lewellen for questioning the

judge’s integrity. Lewellen states that this is the

conduct that displeased Raff and the judge.

* * *

Lewellen also testified that Sheriff May advised

him that he needed to take steps to apologize to

the trial judge and Raff if he wanted, in effect,

to get back in their good graces and minimize

A 20

the consequences that could flow from

Lewcllen’s criminal case.

* * *

Lewellen testified that Sheriff May advised him

that he, Lewellen, should go to Raff and

apologize and that he could avoid some of the

difficulties confronting him. Lewellen further

testified that Sheriff May said that in 1972,

when May was under investigation by a Lee

County Grand Jury, May went to Raff and

apologized to Raff and “Gene fixed the Grand

Jury.”

Lewellen, 649 F. Supp. at 1232 and n.4, 1234.

The testimony of Sam Blount also supports the

district court’s finding of retaliatory prosecution. Blount

testified that Sheriff May said, in effect, that criminal

charges might be brought against Lewellen because the

prosecutors were displeased by Lewellen’s conduct of the

defense of Banks in the state rape trial.8

The questioning of Sam Blount was as follows:

O. [By Mr. Hairston, attorney for Lewellen] Okay Now, vou had a

discussion about sonic potential charges, then, with Sheriff May?

A. That’s correct.

A 21

As evidence that Lewellen’s prosecution was

initiated at least in part because Lewellen is black,

Q. Did Sheriff May indicate to you why such charges might be brought

against plaintiff Lewellyn [sic]?

A. Yes, he did.

Q. And what did he say?

A. The sheriff explained when 1 was in his office that attorney Lewellyn

[sic] had a manner the day before or a couple of days before during a

court session that was very much unprofessional and unruly for a court

or for a court officer.

Q. Now, did you execute an affidavit in this matter?

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Q. Do you recall what you put in that affidavit?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What was that, sir?

A. That the sheriff emphasized, his emphasis were that he was very, very

disappointed and that he thought that Bill had done some things that

would cause the prosecutor of our county, as well as the judge, to not

cooperate with him during the court session. I understand that they were

overruling all of attorney Lewellyn’s [sic] objections, and that was

basically how I received, from my intelligence, that was the payback

situation.

Q. Did he indicate to you that the conduct of Mr. Lewellyn [sic] during

that court session you referred to towards defendant Raff and Cahoon

might cause some problems for Mr. Lewellyn [sic], some legal problems

for Mr. Lewellyn [sic]?

A. Yes, sir, that he very well may be charged.

O- Okay. Do you remember any specific language that Sheriff May used

in terms to indicate the nature of the conduct?

A. Yes, sir, 1 think he said he had shown his butt in the courtroom, how

he had acted and that he had pissed everybody off. And I think that

"everybody” was to include the officers of the court, the prosecutor,

deputy prosecutor and the judge.

A 22

the district court referred to the testimony of Neal,

an attorney who had practiced law in Lee County for

approximately seven years. Lewellen, 649 F. Supp. at

1233 n.8. Neal testified about the disparate treatment

black attorneys were subjected to by Raff and

Cahoon. The district court also stated that “the

evidence describefs] an environment in which

Lewellen will not be assured adequate vindication of

due process and equal protection in the Lee County

Circuit Court * * Id. at 1233.

Finally, as evidence that Lewellen’s prosecution

was motivated by the prosecutors’ desire to retaliate

for and discourage Lewellen’s exercise of his first

amendment rights, the district court found that:

The scheduling of Lewellen’s criminal case for

trial on October 10, 1986, for November 17,

Q. What was the payback situation, sir?

A. That was the lack of cooperation by anybody that day because of how

attorney Lewellyn [sic] had acted.

Q. Would you repeat that?

A. The statement was made that all of his objections were overruled. I’m

not an attorney so I’m just trying to relate it how I recollect it. That all

of his objections were overruled and that he was not able to get

anything across during the court session because of how he had act,

and that was kind of the payback to the point that the court was not

listening to anything attorney Lewellyn [sic] was saying.

Q. Was there any discussion concerning any possible criminal charges

that might be brought against Mr. Lewellyn [sic]1

A 23

1986, took place twenty-four (24) days prior to

the General Election conducted on November

4, 1986, in which Lewellen was running as an

Independent against a Democratic incumbent,

when Lewellen was defeated. This Court is of

the opinion that there is a strong likelihood that

Lewellen can establish that his opponent in the

senatorial race made reference to this

scheduling during the campaign, and that the

scheduling was calculated to impede and impair

his First Amendment rights.

Id. at 1232 n.5.9

The state officials argue that all of these findings

are clearly erroneous, or, even if not erroneous,

irrelevant, because “[t]he sole issue before this Court is

whether the prosecutors had a reasonable expectation of

obtaining a valid conviction of Lewellen.” We disagree

with both assertions.

A. I think it was— I think the statement was insinuated by the sheriff that

there were possibly some charges that may be brought against attorney

Lewellyn [sic] unless he rectified the situation by going back and making an

apology is what I think that the intentions were. "

Transcript at 275-77.

The district court did not specifically refer to this testimony in its opinion;

nevertheless, it is our duty to examine the entire record to determine if the district

court’s findings of retaliatory prosecution is clearly erroneous. See. e.e.. Anderson

v. City' of Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 564. 574-75 nQSSl

We note that it is not clear that Lewellen would be able to raise these issues as

defenses to a witness bribery charge. Cf. Kavlor v. Fields. 661 F.2d 1177 1182 (8th

Cir. 1981).

First, the district court’s findings arc not irrelevant.

The “bad faith and harassment” exception to the

Younger abstention doctrine is applicable when criminal

prosecutions are instituted for impermissible purposes.10

All of the district court’s findings are directed toward

that ultimate issue.

Moreover, it is of no significance that the district

court’s findings concerning the impermissible purposes

In a thorough and thoughtful opinion, H. Lee Sarokin, a distinguished federal

district judge, recently surveyed the types of impermissibly-motivated state

prosecutions that have been held enjoinable under the bad faith exception to the

Younger doctrine:

courts have found bad faith where prosecutors have instituted charges

in violation of a prior immunity agreement, Rowe v. Griffin. 676 F.2d 524

(11th Cir. 1982); where a prosecutor has pursued highly questionable

charges against the plaintiff apparently for the sole purpose of gaining

publicity for himself, Shaw v. Garrison. 467 F.2d 113 (5th Cir.), cert

denied, 409 U.S. 1024, 93 S. Ct. 467, 34 L.Ed.2d 317 (1972); where a

prosecution is motivated by a purpose to retaliate for or to deter the

filing of a civil suit against state officers, Wilson v. Thompson. 593 F.2d

1375 (5th Cir. 1979); and, specifically, where a prosecution has been