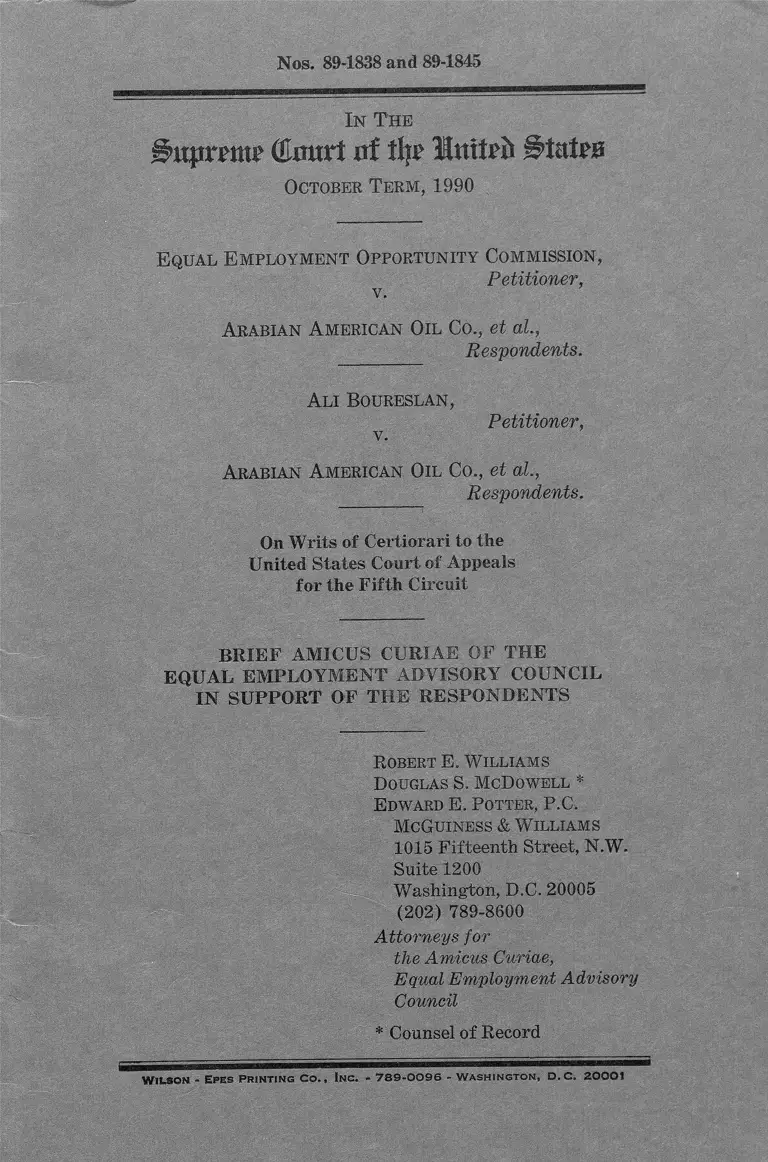

Equal Opportunity Commission v. Arabian American Oil Company Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Respondents

Public Court Documents

December 17, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Equal Opportunity Commission v. Arabian American Oil Company Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Respondents, 1990. 2d1632ab-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3219735b-45dd-41bf-899d-54e3c24672a7/equal-opportunity-commission-v-arabian-american-oil-company-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-the-respondents. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 89-1838 and 89-1845

In T he

Bnpnmv (Emtrt of tty? United #tatw

October T e r m , 1990

E q u a l E m p l o y m e n t Oppo r tu n it y Co m m is s io n ,

Petitioner,v.

A r a b ia n A m erican O il Co., et at.,

Respondents.

A li B o u reslan ,

Petitioner,v.

A ra b ia n A m erican O il Co ., et ah,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT ADVISORY COUNCIL

IN SUPPORT OF THE RESPONDENTS

Robert E. W illiams

Douglas S. McDowell *

Edward E. Potter, P.C.

McGuiness & W illiams

1015 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 1200

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 789-8600

Attorneys for

the Amicus Curiae,

Equal Employment Advisory

Council

* Counsel of Record

W il s o n - Epes Pr in tin g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............ ........... .................. iii

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE_____ __ _ 1

ISSUE PRESENTED________ _____ _____ ______ ____ 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE______________ __ ____ 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .... ........ .... ..................... 5

ARGUMENT .......... .............................. ............. ........... . 9

I. TITLE YII CANNOT PROPERLY BE INTER

PRETED TO COVER EMPLOYERS OF

AMERICAN CITIZENS WORKING OUTSIDE

THE UNITED STATES, BECAUSE THE

LANGUAGE OF TITLE VII AND ITS LEGIS

LATIVE HISTORY EVIDENCE NO AFFIRM

ATIVE CONGRESSIONAL INTENT TO AP

PLY TITLE VII EXTRATERRITORIALLY. .. 9

A. Employment Statutes Are Presumed To Ap

ply Within the Boundaries of the United

States Unless Congress Clearly Expresses

Its Intent That Such a Statute Is To Have

Extraterritorial Application ____ ______ ____ 9

B. When Congress Has Intended That an Em

ployment Statute Should Apply Outside the

United States, It Has Shown That Intent

Clearly and Unambiguously_______________ 12

II. EXTRATERRITORIAL APPLICATION OF

TITLE VII WTOULD CONFLICT WITH

PROPER CONSTRUCTION OF INTERNA

TIONAL LAW PRINCIPLES.................. ....... 14

A. The Dissent and the Amici Incorrectly Rely

On Restatement (Third) Section 403 With

out First Having Established a Basis of

Jurisdiction Under Restatement (Third)

Section 402 .......... ....... ...... ............. ...... ....... . 14

B. Extraterritorial Application of Title VII

Would Be Impractical and Unreasonable....... 18

11

III. CONGRESS’ FAILURE TO ESTABLISH

OVERSEAS PROCEDURES FOR ENFORCE

MENT, DEFERRAL OF CASES, INDIVID

UAL RELIEF AND CONFLICTS OF LAWS

IS FURTHER COMPELLING EVIDENCE

THAT IT DID NOT ENVISION EXTRATER

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

RITORIAL APPLICATION OF TITLE VII..... 20

A. Overseas Application of Title VII’s Remedial

Provisions Would Impact Directly on the

Nationals of the Host Country „...... ......... -.... 20

B. Overseas Application of Title VII’s Proce

dural Mechanism Would Be Impractical and

Should Not Be Imposed in Other Countries

Given the Lack of a Congressional Mandate

To Do So................................ - .......... - ..... -.... 22

IV. AMICI NAACP, LEGAL DEFENSE FUND,

ET AL., MISCONSTRUE CONGRESSIONAL

INTENT AND IMPROPERLY URGE THIS

COURT TO MAKE FOREIGN POLICY DECI

SIONS CONCERNING EMPLOYMENT PRAC

TICES OVERSEAS_________ ___ ______ _____ 25

CONCLUSION............................ ......... -.............. -----...... 29

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Abrams v. Baylor College of Medicine, 805 F.2d

528 (5th Cir. 1986) .......... ................- ......- - - - - - 28

Air Line Dispatchers Ass’n v. National Mediation

Board, 189 F.2d 685 (D.C. Cir. 1951), cert, de

nied, 342 U.S. 849 (1951)....... - . . . . --------- ---- ----- 10

Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping

Corp., 109 S.Ct. 683 (1989)------------5,9,10,11,14,23

Benz v. Compania Naviera Hidalgo, S.A., 353 U.S.

138 (1957) _______________ ------- --------------------- 9> 10

Bryant v. International School Servs., Inc., 502

F. Supp. 472 (D.N.J. 1980), rev’d on other

grounds, 675 F.2d 562 (2d Cir. 1982) ............... . 14

Cleary v. United States Lines, Inc., 728 F.2d 607

(3d Cir. 1984) ............ -............ ........ - .......-..... -3,12, 23

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) — 2

EEOC Dec. No. 77-1, Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH)

"|T 6557 (October 31, 1976) .......... - .............. ........ 29

EEOC Dec. No. 84-2, Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH)

6840 (December 2, 1983) ---------------— 29

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) .... ........ .................. -....... -............... - 21

Foley Bros., Inc. v. Filardo, 336 U.S. 281 (1949) ..5, 9,10,

14, 19, 22

Hodgson v. Union de Permisionarios Circulo Rojo,

331 F. Supp. 1119 (S.D. Tex. 1971)............ -..... - 8

Int’l Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324 (1977) _______________ __________________ 2

Kern v. Dynalectron Corp., 577 F. Supp. 1196

(N.D. Tex. 1983), aff’d, 746 F.2d 810 (5th Cir.

1984)___ _____ ___ -......... -----............. - .............. - 28

Laker Airways v. Sabena, Belgian World Airlines,

731 F.2d 909 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ........... -...... ......... 16

Love v. Pullman Co., 13 Fair Emp. Prac. Cases

(SNA) 424 (D. Colo. 1976), aff’d, 569 F.2d

1074 (10th Cir. 1978)------------------------------- -..... 14

Martin v. Wilks, 109 S.Ct. 2180 (1989) — ............ 8, 21

McCulloch v. Sociedad Nacional de Marineros de

Honduras, 372 U.S. 10 (1963)..—...... - - —- 9

Pfeiffer v. Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., 755 F .2d 554 (7th

Cir. 1985) ..... -___________ __ -............. - .....3, 12,16, 28

IV

Ralis v. RFE/RL, Inc., 770 F.2d 1121 (D.C. Cir.

1985).... ........ ...... .............................. ..................... 12

S.F. DeYoreo v. Bell Helicopter Textron, Inc., 785

F.2d 1282 (5th Cir. 1986) ____________________ 12, 13

Steele v. Bulova Watch Co., 344 U.S. 280 (1952).... 22

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981) ..................................................... 2

Thomas v. Brown and Root, Inc., 745 F.2d 279

(4th Cir. 1984) ................................. .................... 12

United States v. Davis, 767 F.2d 1025 (2d Cir.

1985)__________________ 16

United States v. Mitchell, 553 F.2d 996 (5th Cir.

1977)........... 9

United States v. Wright-Barker, 784 F.2d 161 (3d

Cir. 1986)__________ _____ ___________ ________ 16

Wards Cove Packing, Inc. v. Atonio, 109 S.Ct. 2115

(1989)............. 2

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Co., 108

S.Ct. 2777 (1988) ............................. ......... „ ........ 2

Zahourek v. Arthur Young & Co., 750 F.2d 827

(10th Cir. 1985)............ ...... .... ......... ................. 8,12

Statutes:

Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967,

as amended, 29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq........... ........ 2

Section 4 (f) (1), 29 U.S.C. § 623 (f) (1 )______ 8,25

Section 4 (g) (1), 29 U.S.C. § 623 (g) (1) ........ 13

Section 11(f), 29 U.S.C. § 630 (f)____________ 12

Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C.

§ 1330 et seq......................... ............ ............... ..... 10, 23

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq............... ..... 2

Section 702, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l...... .......... ....... 6,11

Section 706, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ( c ) ........ 24

Section 706, 42 U.S.C. § 200Qe-5 (d) .................. 24

Section 706, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (e ).............. 24

Section 706, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ( f ) ( 3 )___ 23

Section 708, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-7...... 24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

V

Section 710, 42 U.S.C. § 200Qe-9.......... ......... . 23

Section 1104, 42 U.S.C. § 2Q00h-4--------- --------- 24

14 U.S.C. §89 (a) ...................... - ..... ......... -...... -...... 11

18 U.S.C. § 1........... ........... ..... -----...... - .......... -...... - 11

19 U.S.C. § 1701........... - - - ..... - - .... -----...... - .... - - 11

28 U.S.C. § 1404 - . - ......... ...................------------------- 7,23

Legislative History:

S. Rep. No. 98-467, 98th Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1984).. 13

S. Res. 323, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. (1956), quoted in

102 Cong. Rec. 14330 (July 25, 1956)..... ....... . 25, 26

129 Cong. Rec. 34,499 (1983)----------------- ---------- 13

Miscellaneous:

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for

1989, Report by the U.S. Department of State

to the House Comm, on Foreign Affairs and the

Senate Comm, on Foreign Relations, 101st Cong.,

2nd Sess. at 1557-60 (February, 1990) ...-.....~~ 25

Equality in Employment and Occupation, General

Survey by the Committee of Experts on the

Application of Conventions and Recommenda

tions, International Labor Organization (1988).. 18

EEOC Policy Statement on Remedies and Relief

for Individual Victims of Discrimination, 8 Fair

Emp. Prac. Man. (BNA) at 405:3001............... 20,21

International Labor Convention No. I l l , Concern

ing Discrimination in Respect of Employment

and Occupation .......... -------------------- -.... —-------- 24

Kirschner, The Extraterritorial Application of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, 34 Lab. Law

J. 394 (July 1983)----------------------------------------- 12

Labor and Workmen Law ..... ................ —- 1®

Articles 48-50 (Employment of Foreigners).... 19

Article 80 (Labor Contract)................... -.......... 19

Article 91 (Obligations of Employer)......... . 19

Articles 160-62, 164-70 (Employment of

Women).......... ..—..... ...... .......................... — 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES'— Continued

Page

VI

Page

Note, Yankees Out of North America: Foreign

Employer Job Discrimination Against American

Citizens, 83 Mich. L. Rev. 237 (1984) ................ . 28

Restatement (Third) Foreign Relations Law

of the United States (1987) ............. ................... 5, 6

Section 401........................................................ 6, 16

Section 402 ............ ....... ..... ......... ..... ........ 6, 15, 16, 17

Section 403............... ........ ........ ............. 5, 6, 15, 16, 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

In T he

Suprem? Gkwrt ni tiff Mnxttb Slate

October Term, 1990

No. 89-1838

Equal E mployment Opportunity Commission,

Petitioner, v. ’

A rabian A merican Oil Co., et al.,

Respondents.

No. 89-1845

A li Boureslan,

Petitioner,v.

A rabian A merican Oil Co., et al,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CIJRIAE OF THE.

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT ADVISORY COUNCIL

IN SUPPORT OF THE RESPONDENTS

The Equal Employment Advisory Council (EEAC) re

spectfully submits this brief amicus curiae which sup

ports the respondents’ position and seeks the affirmance

of the en banc majority opinion of the court below.

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

EEAC is a nationwide association of employers or

ganized in 1976 to promote sound approaches to the elim

ination of employment discrimination. Its membership

comprises a broad segment of the employer community

2

in the United States, including over 220 major corpora

tions and several trade associations which themselves

have hundreds of corporate members. Its Board of Di

rectors is composed of experts in labor and equal employ

ment opportunity. Their combined experience gives

EEAC a unique depth of understanding of the practical,

as well as legal aspects of EEO policies and require

ments.

As employers, EEAC’s members are subject to the pro

visions of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 20G0e et seq., and the other various

federal orders and regulations pertaining to nondiscrim-

inatory employment practices. Also, many of EEAC’s

members are multinational corporations with overseas

facilities employing both United States citizens and na

tionals of other countries. As such, EEAC members have

a direct interest in the Issue presented for the Court’s

consideration in this case; that is, whether the provisions

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 apply to

American citizens working overseas for American com

panies. Indeed, EEAC filed briefs amicus curiae before

the initial court of appeals panel and the en banc court

in the instant case on the precise issue now before this

Court.

As a significant part of its activities, EEAC has par

ticipated as amicus curiae in a number of cases involving

the interpretation and enforcement of Title VII.1 In ad

dition, EEAC has filed several amicus curiae briefs in

cases involving the extraterritorial application of the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), 29 U.S.C.

§ 621 et seq. These briefs were filed before Congress

amended the ADEA in 1984 to extend its coverage ex

1 E.g., Wards Cove Packing, Inc. V. Atonio, 109 S.Ct. 2115 (1989) ;

Watson v. Forth Worth Bank and Trust Co., 108 S.Ct. 2777 (1988) ;

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) ; Texas Dept, of Com

munity Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981) ; Int’l Bhd. of Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977).

3

pressly to United States citizens abroad.2 Accordingly,

because of the potentially enormous impact upon the em

ployment practices and policies of corporations who em

ploy individuals abroad and must comply with the con

flicting laws of their host countries, this brief is sub

mitted on behalf of EEAC’s nationwide constituency.

ISSUE PRESENTED

Did Congress intend in 1964 to extend the employment

discrimination provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

overseas to regulate the practices of U.S. employers of

U.S. citizens in workplaces outside the United States?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The facts are fully set forth in the Respondents’ brief

and adopted by reference herein. The facts most perti

nent to EEAC’s brief are set forth below.

The plaintiff, a Moslem United States citizen, was

born in Lebanon and worked for the ARAMCO Service

Company (ASC) in Texas until 1980, when he requested

a transfer to Saudi Arabia to work for the Arabian

American Oil Company (ARAMCO). The plaintiff sub

sequently instituted this action alleging that his British

supervisor in Saudi Arabia began harassing him about

his national origin, race and religion in September 1982.

He subsequently was laid off in June 1984, and initiated

these proceedings.

The district court granted ARAMCO’s motion to dis

miss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, and held that

Title VII could not be applied extraterritorially. Boures-

lan v. ARAMCO, Pet. App. 77a-82a.3 Specifically, the

2 See Pfeiffer v. Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., 755 F.2d 554 (7th Cir.

1985) ; Zahourek v. Arthur Young & Co., 750 F.2d 827 (10th Cir.

1985) ; and Cleary v. United States Lines, Inc., 728 F.2d 607 (3d

Cir. 1984).

3 Pet. App. references are to the appendix to the United States’

petition for a writ of certiorari.

4

court found that “ Congress enacted Title VII to remedy

domestic discrimination” and “ [tjhere is no indication

that Congress was concerned about discrimination

abroad.” Id. at 79a. The court concluded that the im

position of Title VII abroad would invade the sovereignty

of other nations, noting in this case that Saudi Arabian

employment law conflicted with Title VII.

A Fifth Circuit panel affirmed the district court’s de

cision by a 2-1 vote, and the full court later reaffirmed

that decision. The court noted in its en banc decision

that it could find no indication in the law or in Title

VII’s legislative history that Congress intended to extend

civil rights protection to American citizens employed

abroad. The court rejected Boureslan’s and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) argu

ments that Title VII’s protections should be extended to

Americans working abroad. Instead, the Fifth Circuit

found strong countervailing policy arguments against the

extraterritorial application of Title VII. The court below

further noted that religious and social customs practiced

in many countries are at odds with those of this country.

Yet Title VII says nothing about potential conflicts with

foreign discrimination laws. Indeed, the panel majority

noted that “ [r] equiring American employers to comply

with Title VII in such a country could well leave Amer

ican corporations the difficult choice of either refusing to

employ United States citizens in the country or discon

tinuing business.” Pet. App. at 41a.

The en banc decision further pointed out that Title VII

is silent in a number of areas where Congress ordi

narily provides guidance if it wishes to apply a statute

extraterritorially. For example, the Act has no provi

sions for venue problems that arise with foreign viola

tions. Also, the statute seems to limit EEOC’s investiga

tory powers to the United States and its territories. Pet.

App. at 5a.

5

In lengthy dissents, Judge King argued that Congress

intended that Title VII apply to the overseas operations

of American corporations. The dissent reasoned that the

Act’s exemption for aliens employed outside the United

States implies that United States citizens working out

side the United States are covered by Title VII. In addi

tion, Judge King argued that Title VII could be enforced

with existing venue, investigatory and other provisions.

Judge King’s panel dissent, which was adopted in the en

banc dissent (Pet. App. at 8a n. 1), set forth additional

reasons for applying Title VII overseas. This analysis

rested in large part upon Section 403, Restatement

(Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United

States, which Judge King interpreted to mean that “ a

statute will not be applied extraterritorially where it

would be unreasonable to do so, unless Congress has af

firmatively required that it be so applied.” Pet. App. at

51a. In Judge King’s view, extraterritorial application

of Title VII would not be unreasonable, and therefore the

statute should be applied abroad without any “ affirma

tive” statement of congressional intent. Pet. App. at 74a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

When Congress enacts an employment statute, the

courts presume that Congress is concerned with domestic

employment conditions and not those outside the United

States. Foley Bros., Inc. v. Filardo, 336 U.S. 281, 285

(1949). Accordingly, the courts have adopted a canon of

construction that a statute enacted by Congress is pre

sumed to apply within the territorial United States. Id.;

Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp., 109

S.Ct. 683 (1989). This presumption can be overcome

only by a clear expression by Congress that it intends

that the statute be applied extraterritorially. Foley

Bros., 336 U.S. at 286.

Neither the Supreme Court nor any federal appeals

court has ever applied an employment statute extraterri

6

torially unless Congress has affirmatively expressed its

intent by statutory language stating that the statute is

applicable “ outside the continental United States,” “ in a

foreign country” or by equivalent language. Here, there

is no direct statutory language or legislative history

clearly expressing that Title VII applies overseas.

The presumption against extraterritoriality cannot be

overcome by reliance upon Section 403 of Restatement

(Third), Foreign Relations Law of the United States

( “ Restatement” ). Indeed, the Restatement reinforces,

rather than rebuts, the presumption. Section 401 estab

lishes the principle that a state has a legitimate right to

exercise its jurisdiction in certain ways, but may not reg

ulate individuals or conduct overseas without limitation.

Section 402, in turn, provides the foundation for an af

firmative exercise of such jurisdiction by the state, and

provides in pertinent part that: “ [s]ubject to § 403, a

state has jurisdiction to prescribe with respect to . . .

(2) the activities, interests, status, or relations of its

nationals outside as well as within its territory . . . .”

Section 403 then follows and provides the limitations on

states’ jurisdiction to prescribe laws and sets forth the

“ reasonableness” limitation of international law when a

state affirmatively attempts to apply a domestic law out

side its own territory.

To the extent the dissent’s and the EEOC’s analyses

focus on the principles set forth in Section 403 (1), they

bypass the initial inquiry set forth in Section 402— that

is, whether Congress did, in fact, prescribe in Title VII

to regulate the activities or conduct of individuals out

side of its territory. For if there is no such law, logic

ally, there can be no such determination of its reasonable

ness. In this ease, Congress has never Indicated that

Title VII would apply to United States citizens working

abroad. Moreover, Section 702 of Title VII cannot be

used to draw the negative inference that Title VII must

cover United States citizens extraterritorially because it

exempts only “ aliens outside any state.”

7

Amici NAACP, Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., et al. offer policy arguments based on an unsup

ported assumption that American employers affirmatively

will engage in discrimination abroad. From, a practical

standpoint, however, employers often must specially train

workers for overseas assignments and provide them with

special compensation, terms and other conditions of em

ployment. The costs of such efforts are higher than those

associated with domestic employment. Thus, the economic

costs of discrimination abroad are prohibitive, and serve

as effective deterrents to discourage rather than encour

age employers to engage in such practices. Nor is extra

territorial application of Title VII necessary to prevent

domestic corporations from making decisions to exclude

minorities, women and other protected individuals from

overseas assignments. In such cases, there generally will

be sufficient nexus to the United States to allow the as

sertion of Title VII jurisdiction, thus allowing an exam

ination. of whether the practice violates the Title VII

rights of U.S. citizens.

Other arguments of the petitioners and their support

ing amici are fraught with pitfalls. As a practical mat

ter, a comprehensive employment discrimination law such

as Title VII cannot be applied overseas without any ap

propriate procedural mechanisms. Yet, when Congress

enacted Title VII in 1964, it limited venue and the

EEOC’s investigatory powers to testimony or evidence

obtained within the states of the United States. When

it amended the law in 1972, it failed to broaden these

powers to matters overseas. And although venue might

be possible where a corporation has its U.S. headquarters,

documents and witnesses may be thousands of miles away

with no possibility of a change of venue for the conveni

ence of the parties or in the interests of justice. 28

U.S.C. § 1404. In addition, Title VII makes no provision

for exempting coverage where it would conflict with the

laws of another sovereign power.

8

In addition, when an American employer’s overseas

work force has citizens of various countries, application

of standard Title VII remedies could directly harm non-

Americans. For example, the EEOC’s remedial guide

lines call for reinstatement, “bumping” of incumbents,

discipline or discharge of offending supervisors, and pref

erential treatment remedies for identified victims of dis

crimination. Employers could protect against attacks

upon case settlements by joining non-U.S. citizens to a

suit in federal court in order to protect their interests.

See Martin v. Wilks, 109 S.Ct. 2180 (1989). But this

not only would draw noncitizens directly into the Amer

ican legal system; it would require them to travel to the

United States in order to protect their job status. If

Congress intended such a result, it hardly comes clear

from a reading of Title VII.

In contrast to Title VII’s silence, when Congress

amended the ADEA in 1984 to extend jurisdiction of its

provisions extraterritorially, it expressly exempted em

ployer practices involving U.S. citizens that would cause

the company to violate the laws of the host country. 29

U.S.C. § 623 (f) (1). Thus, when Congress has intended

that a United States employment statute be applied to

American companies overseas, it has exercised great care

to ensure that such application will not conflict with

foreign statutes,

Were this Court to accept the economic and interna

tional policy arguments set forth by the petitioners and

their amici, it effectively would be making foreign policy

and legislative decisions in a matter where Congress has

chosen not to act. “ It is [outside] the province of this

Court to delve into matters international on such a ten

uous basis.” Hodgson v. Union de Permisionarios Circulo

Rojo, 331 F. Supp. 1119, 1122 (S.D. Tex. 1971).

9

ARGUMENT

I. TITLE' YII CANNOT PROPERLY BE INTER

PRETED TO COYER EMPLOYERS OE AMERICAN

CITIZENS WORKING OUTSIDE THE UNITED

STATES, BECAUSE, THE LANGUAGE OF TITLE

VII AND ITS LEGISLATIVE HISTORY EVIDENCE

NO AFFIRMATIVE CONGRESSIONAL INTENT1 TO

APPLY TITLE YII EXTRATERRITORIALLY.

A. Employment Statutes Are Presumed To Apply

Within the Boundaries of the United States Unless

Congress Clearly Expresses Its Intent That Such

a Statute Is To Have Extraterritorial Application.

The question before the Court is whether Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which generally prohibits

employment discrimination on the basis of race, color,

religion, sex or national origin, covers United States

citizens employed by U.S. companies in foreign coun

tries. It is a well-established canon of construction that

a statute enacted by Congress is presumed to apply only

within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States

unless a contrary intent is expressed. Argentine Repub

lic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp., 109 S.Ct. 683 (1989) ;

Foley Bros., Inc. v. Filar do, 336 U.S. 281, 285 (1949) ;

United States v. Mitchell, 553 F.2d 996, 1002 (5th Cir.

1977). In the “ delicate field of international relations

there must be present the affirmative intention of the

Congress clearly expressed. It alone has the facilities

necessary to make fairly such an important policy deci

sion. . . Benz v. Compania Naviera Hidalgo, S.A., 353

U.S. 138,147 (1957) (emphasis added).

The courts, including the appellate and district courts

below, have uniformly construed United States employ

ment laws as being limited to the territorial boundaries

of the United States absent an affirmative expression of

congressional intent that the statute have an extraterri

torial effect. See, e.g., McCulloch v. Sociedad Nacional de

10

Marineros de Honduras, 372 U.S. 10, 19 (1963) (Na

tional Labor Relations Act held not to apply to maritime

operations of foreign flagships absent “ specific language

in the act itself or in its extensive legislative history

that reflects such a congressional intent” )-4 In sum,

absent a clear expression of congressional intent to apply

an employment statute outside the United States, the

courts assume “ that Congress is primarily concerned

with domestic conditions.” Foley, 336 U.S. at 285.

This Court in Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess

Shipping Corp., 109 S.Ct. 683 (1989), recently applied

these principles and restated the necessity of affirmative

congressional intent to extend a statute extraterritorially.

Argentine Republic involved the issue of whether the fed

eral courts have jurisdiction over noncommercial tort

claims against a foreign country under the Foreign

Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) 28 U.S.C. § 1330

et seq. Specifically, the Court focused on whether the

FSIA conferred jurisdiction over tortious acts committed

on the high seas outside of United States territorial

waters.5 The Court observed that “when it desires to do

4 See also, Benz, 353 U.S. at 142 (Labor Management Relations

Act of 1947 held not to extend to disputes resulting from picketing

of foreign ships in United States ports because parties could “point

to nothing in the Act itself or its legislative history” indicating con

gressional intent to cover such disputes, as “ there must be present

the affirmative intention of Congress clearly expressed.” Id. at 147) ;

Foley Bros., 336 U.S. at 286 (Eight Hour Law held not to apply to

contracts between the United States and private contractors for

construction work in a foreign country “ in the absence of a clearly

expressed purpose” by Congress) ; Air Line Dispatchers Ass’n. v.

National Mediation Board, 189 F.2d 685 (D.C. Cir. 1951), cert,

denied, 342 U.S. 849 (1951) (amendment to Railway Labor Act

which extended coverage to air carriers “engaged in interstate or

foreign commerce” held not to apply outside the United States in

the absence of explicitly congressional intent).

5 Respondents brought these claims against the Argentine govern

ment for damages its ship sustained when it was attacked in inter

national waters by Argentine military aircraft during the Falkland

Islands war. 109 S.Ct. at 686-87.

11

so, Congress knows how to place the high seas within the

jurisdictional reach of a statute.” 109 S.Ct. 691.6 Since

Congress made no affirmative statements to apply the

FSIA extraterritorially, the Court applied Foley and

held that the FSIA does not extend to tortious conduct

outside the United States territorial waters. Id.

The Argentine Republic principles are no less applicable

in this case. In enacting Title VII, Congress was con

cerned solely with the domestic aspects of employment

discrimination. Indeed, after examining the statutory

language and legislative history of Title VII, the court

below correctly concluded that, “ [the] references to Title

VII’s legislative history fall far short of the clear expres

sion of congressional intent required to overcome the pre

sumption against extraterritorial application.” (Pet. App.

at 38a) ; and see (Pet. App. at 81a) C“ [i]t is much more

likely that Congress never considered the issue.” ). And

as the majority below observed:

The statements, carefully taken from a voluminous

legislative history, are no more specific than the stat

utory language itself. To rely on such general policy

statements would effectively adopt a presumption in

favor of extraterritorial application. This is par

ticularly true when the legislative history contains

numerous statements that arguably favor geographic

limits for Title VII.

Pet. App. at 38a. And see Pet. App. at 81a. (“ It is

doubtful that Congress reserved the question of Title

VII’s application for the courts to decide.” ) .7

6 The Court cited three statutes as examples where Congress spe

cifically referred to the high seas in order to extend extraterritorial

jurisdiction. See, e.g., 14 U.S.C. § 89(a) (Coast Guard searches and

seizures upon the high seas) ; 18 U.S.C. § 7 (Criminal code extends

to high seas) ; 19 U.S.C. § 1701 (Customs enforcement on the high

seas). 109 S.Ct. at 691 n.7.

7 Amicus EEAC further urges the Court to adopt the panel hold

ing that the alien exemption found in Section 702 of Title VII does

not imply that U.S. citizens working overseas are covered by Title

VII. This issue has been fully briefed in the respondents’ briefs to

12

B. When Congress Has Intended That an Employment

Statute Should Apply Outside the United States,

It Has Shown That Intent Clearly and Unambig

uously.

Congress has demonstrated on many occasions that it is

well aware that it must specifically and directly provide

for the extraterritorial application of an employment

statute when it intends the statute have such effect. For

example, several courts had ruled that the Age Discrimi

nation in Employment Act (ADEA) did not apply ex-

traterritorially.8 In response, Congress in 1984 amended

Section 11(f) of the ADEA by adding a new sentence to

the definition of “ employee” to provide that: “ The term

‘employee’ includes any individual who is a citizen of the

United States employed by an employer in a workplace

in a foreign c o u n t r y 29 U.S.C. § 630(f) (emphasis

this Court. EEAC agrees with those arguments. As further brief

ing would be repetitious, we adopt those arguments by reference.

We point out, however, that one commentator on the exemption

provision, noting the absence of legislative history regarding its

purpose, has stated that “ the exemption language . . . was simply

adopted from early civil rights legislation that was introduced at a

time [1949] when aliens were excluded from certain domestic pro

tective labor legislation and restricted in their employment oppor

tunities within the United States. . . . ,[A]t the time, the original

drafters did not want to call attention to the fact that such legisla

tion would apply to citizens as well as aliens in the United States.”

Kirschner, 34 Lab. Law J. at 399-400 (July 1983) (footnote omit

ted) . Under these circumstances, the alien exemption provision

alone, which does not directly address the application of Title VII

to U.S. citizens, can hardly be said to be a clear expression of con

gressional intent to apply Title VII to U.S. citizens extraterritorially.

8 Six circuits held that the ADEA prior to 1984 did not cover

American citizens employed in foreign countries. E.g., S.F. DeYoreo

v. Bell Helicopter Textron, Inc., 785 F.2d 1282 (5th Cir. 1986) ;

Ralis v. RFE/RL, Inc., 770 F.2d 1121 (D.C. Cir. 1985) ; Pfeiffer v.

Wm. Wrigley, Jr. Co., 755 F.2d 554 (7th Cir. 1985); Zahourek v.

Arthur Young and Co., 750 F.2d 827 (10th Cir. 1984) ; Thomas v.

Brown and Root, Inc., 745 F.2d 279 (4th Cir. 1984) ; and Cleary

v. United States Lines, Inc., 728 F.2d 607 (3d Cir. 1984).

13

added). Furthermore, it added a new Section 4 (g )(1 )

that states: “ If an employer controls a corporation whose

place of incorporation is in a foreign country, any prac

tice by such, corporation prohibited under this section

shall be presumed to be such practice by such employer.”

29 U.S.C. § 623(g)(1 ) (1984) (emphasis added). These

statutory provisions are also supported by unequivocal

legislative history that these amendments “make[] provi

sions of the Act apply to citizens of the United States

employed in foreign countries by United States corpora

tions or their subsidiaries.” S. Rep. No. 98-467, 98th

Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1984). In contrast, neither Title VII

nor its legislative history contains any such direct expres

sion that it applies extraterritorially.

Congress obviously considered the 1984 amendment

to the ADEA necessary to provide an affirmative expres

sion of its intent. In S.F. DeYoreco v. Bell Helicopter

Textron, Inc., 785 F.2d 1282 (5th Cir. 1986), the Court

concluded that the amendment must have added some

thing that was not already there. “ If Congress found it

necessary to extend the coverage of the ADEA to foreign-

employed United States citizens, the statute’s, reach must

not originally have gone that far.” Id. at 1283. Thus.,

the 1984 amendment effectively changed the law rather

than just clarified it.9

® Senator Grassley’s statement when introducing the ADEA

amendment in 1983 does not establish that Congress intended to

make Title VII applicable overseas. See 129 Cong. Eec. 34,499

(1983). The Senator stated that the substantive provisions of the

ADEA and Title VII are “worded nearly exactly” the same and

that “at least two district courts have held [that Title VII] does

apply abroad. Thus, the legislation I am introducing today clears

up an anomaly I believe Congress never Intended.” Id.

The real anomaly, however, is that, having made this statement,

Senator Grassley proceeded to not use Title VIFs language on em

ployee coverage to amend the ADEA. Instead, he used more specific

language to make sure that the ADEA would apply outside the

United States. Indeed, since he felt Title VII and the ADEA’s

substantive language were nearly identical, the fact that he used

14

Accordingly, when Title VII is compared with employ

ment and other statutes in which Congress has directly

and unambiguously made clear its intention that the

statute have extraterritorial effect, it is evident that In

enacting Title VII, Congress manifested no such intent.

II. EXTRATERRITORIAL APPLICATION OF TITLE

VII WOULD CONFLICT WITH PROPER CON

STRUCTION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW PRINCI

PLES,

A. The Dissent and the Amici Incorrectly Rely On

Restatement (Third) Section 403 Without First Hav

ing Established a Basis of Jurisdiction Under Re

statement (Third) Section 402.

As shown, the well-established principles found in

Foley, Argentine Republic and other decisions create the

presumption against extraterritorial application of a fed

eral statute. Indeed, as Judge King’s initial dissent in

this case recognized, ordinarily there is “ a presumption

that Congress intends legislation to apply only within the

territorial jurisdiction of the United States, unless & con

trary intent appears.” Pet, App. 43a-44a.

The dissent (Pet. App. 50a-60a), and amici curiae Law

yers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and Inter

national Human Rights Law Group argue, however, that

because, in their view, it would be “ reasonable” under

principles of international law to apply Title VII outside

different jurisdictional language would indicate he felt he had to go

beyond Title VII to assure overseas coverage of the ADEA. More

over, the two district court cases hardly are persuasive as to Title

VII’s coverage. One merely addresses the issue in dicta (Love v.

Pullman Co., 13 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases (BNA) 423 (D. Colo.

1876), aff’d, 569 F.2d 1074 (10th Cir. 1978)), and the other was

reversed on appeal. See Bryant v. International Schools Servs., Inc.,

502 F. Supp. 472 (D.N.J. 1980), rev’d on other grounds, 675 F.2d

562 (3d Cir. 1984). Thus, the meager legal weight of these authori

ties is hardly sufficient to overcome the presumption against statu

tory extraterritory.

15

the United States, the presumption is thereby overcome.

Their primary authority is Section 403 of Restatement

(Third), Foreign Relations Law of the United States

(“ Restatement” ). As discussed below, however, the Re

statement reinforces, rather than rebuts, the presumption

against extraterritoriality.

Under international law, a state- may not regulate in

dividuals or conduct overseas without limitation. Section

401 of the Restatement provides in part:

Under international law, a state is subject to lim

itations o n [:]

(a) jurisdiction to prescribe, i.e., to make its law

applicable to the activities, relations, or status of per

sons, or the interests of person in things, whether by

legislation, by executive act or order, by administra

tive rule or regulation, or by determination of a

court; . . . .

Section 402, in turn, provides the foundation for an

affirmative exercise of such jurisdiction by the state-. It

is clear from the Introductory Note to Section 402, how

ever, that the jurisdictional chapter of the Restatement

was intended to provide limitations on the overseas exer

cise of the state’s, authority. Thus-:

Attempts by some states—notably the United States

— to apply their law on the basis of very broad con

ceptions of territoriality or nationality bred resent

ment and brought forth conflicting assertions of the

rules of international law.

Restatement at 236. When the United States attempted

to exercise its authority overseas in a whole range of

areas (e.g., economic sanctions, maritime., aeronautics,

antitrust, securities), it generated resentment, blocking

legislation, and conflicting assertions of jurisdiction. Id.

at 236.

Accordingly, the United States courts, and courts in

other countries, have interpreted the “known or presumed

16

intent of Congress, in light of changing understandings.”

Id. at 236-37. Because of these concerns about overly

aggressive application of United States laws in foreign

lands, the Restatement indeed may erect a stronger pre

sumption against extraterritoriality than the presump

tion made by our federal courts. In no way can the Re

statement be interpreted to provide affirmative support

for application of Title VII overseas even without an

“ affirmative statement of congressional intent,” as ar

gued in Judge King’s dissent (Pet. App. at 75a, empha

sis in the original).

Furthermore, while Section 401 of the Restatement

establishes the principle that a state has a legitimate right

to exercise its jurisdiction in certain ways, Section 402

provides that the requisite foundation for the exercise of

such authority must be found. Section 402 states in

pertinent part, “ [sjubject to § 403, a state has jurisdic

tion to prescribe with respect to . . . (2) the activities!,

interests, status, or relations of its nationals outside as

well as within its territory. . . .” Section 403 then fol

lows and provides the limitations on a state’s jurisdiction

to prescribe laws. Specifically, Section 403 (1) sets forth

the “ reasonableness” limitation of international la w :10

Even when one of the bases for jurisdiction under

§ h02 is present, a state may not exercise jurisdic

tion to prescribe law with respect to a person or ac

tivity having connections with another state when

10 Many courts have applied and interpreted the “ reasonableness”

test. See, e.g., Laker Airways v. Sabena, Belgian World Airlines,

731 F.2d 909, 923 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (Eelying on Section 403(1), the

court concluded that jurisdiction may not “exceed the bounds of

reasonableness imposed by international law.” ) ; United States v.

Wright-Barker, 784 F.2d 161, 168 (3d Cir. 1986) ; United States

v. Davis, 767 F.2d 1025 (2d Cir. 1985). Indeed, the 1987-88 pocket

part to the Eestatement at 157 cites Pfeiffer v. Wm. Wrigley, Jr.

Co., 755 F.2d 554 (7th Cir. 1985) (ADEA does not apply overseas),

as a case where assertion of jurisdiction apparently would not be

reasonable under Section 403.

17

the exercise of such jurisdiction is unreasonable.

(Emphasis added).

The accompanying comment states that:

The principle that an exercise of jurisdiction on one

of the bases indicated in § 402 is nonetheless un

lawful if it is unreasonable is established in United

States law, and has emerged as a principle of inter

national law as well. There is wide international

consensus that the links of territoriality or nation

ality, § 402, while generally necessary, are not in all

instances sufficient conditions for the exercise of such

jurisdiction.

To the extent various briefs focus on the principles set

forth in Section 403(1), they fail to address the initial

issue posed in Section 402: whether Congress has in fact

prescribed a law to regulate the activities or conduct of

individuals outside of its territory under Title VII. For

if there is no such law and Congress did not apply a

law outside the United States, then Section 403 would

not come into play, regardless of whether overseas ap

plication of the law wTould be reasonable.

Thus, the requirement of “ reasonableness” in Restate

ment Section 403 (1) is an additional limitation a statute

must overcome in order to have extraterritorial effect, but

only where Congress clearly intended that the law have

such an effect. Section 403 is not an independent test for

determining whether Congress, in fact, had such intent.

In the instant case, Congress has not seen fit to extend

its jurisdiction to “prescribe law with respect to . . .

[employment discrimination] . . . the activities, interests,

status, or relations of its nationals outside as well as

within its territory . . . .” Restatement Section 402. Be

cause Congress has never expressed intent to do so, this

Court is without authority to construct such intent judi

cially in order to satisfy policy considerations.

18

B. Extraterritorial Application of Title VII Would Be

Impractical and Unreasonable.

The unreasonableness of applying Title VII overseas

provides an additional reason why the courts should re

frain from doing so absent a clearer expression of Con

gressional intent than presently can be found in. Title

VII. Thus, even if arguendo, the requisite expression of

clear congressional intent to apply Title VII extraterri

torial ly could be claimed to have been made in this case,

so as to make the “ reasonableness” of such jurisdiction

a relevant inquiry, this factor ultimately would not avail

the appellants and their amici, because the extraterri

torial application of Title VII would be unreasonable

from a practical standpoint.

Congress and the courts have been justifiably reluctant

to extend the scope of employment statutes involving the

personnel policies and practices of multinational com

panies outside the United States for two primary reasons.

First, extraterritorial application of United States em

ployment laws would invade the sovereignty of the host

country to establish employment standards for workers

within its territories and its own citizens. Second, it

would subject companies attempting to comply with

United States laws to potentially conflicting standards.

These policy considerations further support the conclu

sion that Title VII should not be applied outside the terri

torial boundaries of the United States.

According to the International Labor Organization, a

specialized agency of the United Nations, nearly 140

countries have enacted some form of employment dis

crimination statute covering both citizens and aliens,11

These laws are not uniform and provide a wide variety

11 International Labor Organization, Equality in Employment and

Occupation, General Survey by the Committee of Experts on the

Application of Conventions and Recommendations (1988).

19

of legal requirements.12 In the instant case, Saudi

Arabian law applies to religious preferences, favoritism

towards nationals and protection of women, and its sub

stantive and procedural provisions differ from those of

Title VII.13 14

Enforcement of Title VII in Saudi Arabia based on

the appellant’s allegations of racial, national origin and

religious discrimination would clearly invade the sover

eignty of Saudi Arabia, whose own discrimination stat

ute applies to employees of foreign corporations operating

within its borders. Id. This conflict is particularly sig

nificant here because, although ARAMCO is incorporated

in the United States, its assets are owned by the Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia and are almost totally located there, the

great majority of its employees are nationals of Saudi

Arabia or other non-United States countries, and its prod

ucts are almost exclusively sold only in Saudi Arabia.

The employment conditions sought to be regulated by

Title VII, therefore, are the “primary concern of a for

eign country.” Foley, 336 U.S. at 286V

12 Id.

13 See, e.g., Labor and Workmen Law, Articles 48-50 (Employ

ment of Foreigners), Article 80 (Labor Contract), Article 91 (Obli

gations of Employer), Articles 160-62, 164-70 (Employment of

Women).

14 The dissent below inadvertently provides an additional argu

ment against applying Title VII overseas. The dissent argues that

“ [w]e do not know, for example, to what extent a foreign state

would enforce its own laws to regulate the employment relationship

between a U.S. corporation and employees who are U.S. citizens, or

whether it would make its administrative and judicial procedures

available to a United States employee seeking to bring a grievance

against a U.S. employer.” Pet. App. at 61a. See also the amicus

brief of the International Human Rights Law Group at 56. Thus,

clearly, the dissent would apply Title VII in foreign nations when

it had no idea of the potential conflict it would create between Title

VII and the law of other host countries.

20

III. CONGRESS’ FAILURE TO ESTABLISH OVERSEAS

PROCEDURES FOR ENFORCEMENT, DEFERRAL

OF CASES, INDIVIDUAL RELIEF AND CON

FLICTS OF LAWS IS FURTHER COMPELLING

EVIDENCE THAT IT DID NOT ENVISION EXTRA

TERRITORIAL APPLICATION OF TITLE: VII.

The arguments that Title VII should be applied over

seas are being made in a legal vacuum, for they appear

to contemplate situations where a federal law may be ap

plied without any appropriate procedural or remedial

mechanisms. Realistically, it is difficult to conclude that

Congress intended that a federal law have extraterritorial

application when it did not concurrently provide any ap

propriate substantive and procedural mechanisms for

such unique applications. Yet in enacting Title VII, Con

gress failed to provide any mechanisms for overseas en

forcement. The legislature’s failure to make any provi

sion dealing with the practical consequences of extending

Title VII overseas is a further compelling reason the

Courts should refrain from applying Title VII overseas

without a clearer mandate from Congress.

A. Overseas Application of Title VII’s Remedial Pro

visions Would Impact Directly on the Nationals of

the Host Country.

Neither the EEOC nor any of its supporting amici

recognize the impact that overseas enforcement of Title

VII would have on the non-U.S. citizens working side-

by-side with American citizens, as occurs to a large de

gree in Arameo’s workforce. For example1, in 1985, EEOC

adopted a policy that “full relief” should be sought in

each case that the EEOC’s District Director concludes has

merit. See EEOC Policy Statement on Remedies and

Relief for Individual Victims of Discrimination, 8 Fair

Empl. Prac. Man. (BNA) at 405:3001.

Such relief could include immediate and unconditional

reinstatement to the position the individual would have

21

occupied absent discrimination. The discriminatee must

be offered some job in the employer’s operation for which

he or she is qualified. Non-U.S. citizens could lose jobs as

a result.

The EEOC’s policy also states that “ [i]n certain cir

cumstances., the Nondiscriminatory Placement of a victim

of discrimination may require the job displacement of

another of the respondent’s employees”— a potentially di

rect impact on individuals who are not U.S. citizens. Id.

at 405:3003. The individual discriminatee also may be

given retroactive seniority, thus affecting the relative

seniority rights of non-American employees. See Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Go., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

Further, should an employer wish to settle a Title VII

case and protect a settlement or consent decree from later

collateral attack by non-Americans, it would have to! join

those non-Americans as parties to the lawsuit so that the

non-Americans could protect their individual rights from

encroachment by a Title VII remedy benefiting others.

See, Martin v. Wilks, 109 S.Ct. 2130 (1989). This proce

dure would be incredibly clumsy, particularly in light of

the government’s argument that these cases should be

tried in the United States in jurisdictions where employ

ers have their principal places of business.

The employer also may be required to educate a non-

U.S. citizen supervisor in how to comply with Title VII.

The employer also may be required by the EEOC “to dis

cipline or remove the offending individual from personnel

authority.” To afford U.S. citizens greater protections

than other employees could have a serious adverse effect

on the morale of foreign nationals in the plant workforce.

Thus, as a practical matter, extraterritorial application

of Title VII would put U.S. companies under strong pres

sure to treat all employees as though they were covered

by Title VII, even if, as in the case of Saudi Arabia, that

might mean violating the laws or religious, practices of

the host country.

22

Thus, like the Court’s refusal to apply the U.S. Eight

Hour Law to Iran and Iraq in Foley Bros. v. Filardo, “ it

would be anomalous . . . for an act of Congress to regu

late” the relative work status of both U.S. and non-U.S.

citizens working for a U.S. employer overseas. 336 U.S.

at 289.15 As in Foley, the federal statute in question here

should not be applied outside U.S. territory.

B. Overseas Application of Title VIPs Procedural

Mechanism Would Be Impractical and Should Not

Be Imposed in Other Countries Given the Lack of a

Congressional Mandate To Do So.

The overseas application of Title VII procedural mech

anisms would cause severe practical problems. Without a

clearer indication that Congress intended that these prob

lems be tolerated, Title VII should be applied only in the

territory of the United States. Several examples are

illustrative. For one, Title VII’s provisions relating to

the EEOC’s investigatory powers and venue demonstrate

that Congress never intended Title VII to apply overseas.

15 The petitioners and their various supporting amici make too

much of the extraterritorial application of the Lanham Act per

mitted by Steele v. Bulova Watch Co., 344 U.S. 280 (1952). There1,

a U.S. citizen committed a trademark infringement in violation of

federal law. Bulova Watch Company, the offended company, was a

U.S. citizen, and there was no concern expressed in that case that

application of the Lanham Act would improperly infringe on any

foreign laws that dealt with trademark infringements. Neither

were the legitimate rights of non-U.S. citizens affected by applica

tion of U.S. law overseas.

Instead, the Court stressed the nexus between the foreign acts

and the U.S. market for Bulova’s watches and concluded that:

[Steele’s] operations and their effects were not confined within

the territorial limits of a foreign nation. He brought com

ponent parts of his wares in the United States, and spurious

“Bulovas” filtered through the Mexican border into this coun

try; his competing goods could well reflect adversely on Bulova

Watch Company’s trade reputation in markets cultivated by

advertising here as well as abroad.

344 U.S. at 286.

23

As enacted in 1964, the EEOC’s investigatory powers

were limited to testimony or evidence obtained within

the states of the United States, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-9. The

amendment of this investigatory authority in 1972 did

not broaden these powers to matters overseas. Thus, “ [ i]f

plaintiff were correct in arguing that [the statute] ap

plies extra,territorially, it would be anomalous for Con

gress not to have authorized power of investigation that

were co-extensive with the reach of the Act.” Cleary v.

United States Lines, Inc., 555 F. Supp. 1251, 1260

(D.N.J. 1983), aff’d, 728 F.2d 607 (2d Cir. 1984).16

Again, when Congress intends a statute to have effect

overseas', it knows how to provide appropriate enforce

ment mechanisms. For example, in Argentine Republic

v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp., 109 S.Ct. 683 (1989),

the Supreme Court analyzed the legislative history of the

Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), and con

cluded that “ Congress’ intention to enact a comprehensive

statutory scheme is also supported by the inclusion in the

FSIA of provisions for venue-. . . removal . . . and attach

ment and execution. . . .” Id. at 688 n.3.

In contrast, in enacting Title VII, Congress was

greatly concerned that it not unduly interfere with the

sovereignty or override the laws of even the various states

of the United States, Sections 708 and 1104, 42 U.S.C.

18 Had Congress intended that Title VII was to have an extrater

ritorial reach, it would have provided for venue over the operations

of American companies employing United States citizens overseas,

instead of limiting venue to the employment decisions of companies

within the United States. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) (3). Further, even

if “principal office” venue might be a technical possibility, there

would be no chance for the parties to move for a change of venue

“ [f]or the convenience of the parties and witnesses, [or] in the

interest of justice.” 28 U.S.C. § 1404. Thus, Title VII cases would

have to be tried in courts which, if a more favorable U.S. forum

were available, would not hear such cases in most instances because

the documents, witnesses and place of violation were thousands of

miles away.

24

§ § 2000e-7, 2000h-4. Accordingly, Congress made specific

provision in Section 706 of Title VII for deferral to state

employment discrimination proceedings, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d-5(c), (d), and (e). Invasion of another coun

try’s sovereignty with respect to that nation’s own dis

crimination laws- would clearly be- a matter of great in

ternational significance. Yet Title VII does not contain

any similar provisions for deferral to the laws of another

country. If would be wholly anomalous to conclude that

Title VII recognizes and respects the laws of the various

American states, but ignores and overrides the laws of

foreign nations.

The amicus International Human Rights Law Group

argues that the likelihood of conflict with Saudi Arabian

policies would be minimal because Saudi Arabia has rati

fied International Labor Organization Convention (No.

I l l ) Concerning Discrimination in Respect of Employ

ment and Occupation. (Br. 57-60) This argument ignores

the fact- that the United States Senate has not ratified

this convention, thus making implausible the conclusion

that there is no potential for conflict. Further, Conven

tion 111 is not self-enforcing. Article 2 of the Convention

allows each individual ratifying country to “ undertake to

declare and pursue a national policy designed to promote

by methods appropriate to national conditions and prac

tice,” the elimination of discrimination. (Emphasis

added).

Even in the United States-, the EEOC will not defer a

charge to a state or locality unless EEOC determines that

the other agency has a nondiscrimination law comparable

to Title VII. See Section 706(c) of Title VII (42 U.S.C.

Sec. 2Q00e-5(c)). EEOC does not suggest to- this- Court

any method by which EEOC or the courts could determine

whether any particular application of Title VII would

conflict with the law of another country. It is ludicrous,

however, to suggest that application of Title VII in Saudi

Arabia wo-uld not conflict with Saudi Arabian practices,

25

See Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1989,

Report by the U.S. Department of State to the Committee

on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives:, and the

Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, February

1990, at 1557-60.

Further, the ADEA again provides another contrast

with Title VII. For, unlike the ADEA, which was specifi

cally expressed to apply abroad, Title VII makes no provi

sion for exempting coverage where it would conflict with

the laws of another sovereign power. In the amendment to

the ADEA, Congress was particularly concerned that the

overseas application of that employment law not conflict

with the existing laws of other countries. Thus, unlike

Title VII, when Congress clearly extended jurisdiction

of the ADEA’s provisions extraterritorially, it expressly

provided in Section 4(f ) (1), 29 U.S.C. § 623(f) (1), that

it is not unlawful for an employer to take any action

prohibited by the ADEA “where such practices involve

[a United States citizen] in a foreign country, and com

pliance . . . would cause such employer . . . to violate the

laws of the country in which such workplace is located.”

Thus, when Congress has intended that a United States

employment statute should be applied to American com

panies and citizens overseas, it has exercised great care

to ensure that such application would not conflict with

foreign statutes.

IV. AMICI NAACP, LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, ET AL„

MISCONSTRUE CONGRESSIONAL INTENT AND

IMPROPERLY URGE THIS COURT TO MAKE

FOREIGN POLICY DECISIONS CONCERNING EM

PLOYMENT PRACTICES OVERSEAS.

The arguments made by amici NAACP Legal Defense

and Education Fund, et al., offer no further support for

the petitioners. Indeed, those arguments highlight the

weakness of Petitioner’s reliance on Title VII’s own his

tory. The Amici are forced to juxtapose the adoption of

Senate Resolution 323, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. in 1956, with

26

the enactment of Title VII in 1964.1T Amici NAACP

Legal Defense Fund et al., draw the inference that since

Congress adopted the resolution in 1956, it also intended

in 1964 to extend Title VII’s coverage abroad. They

claim this resolution “ further illustrates Congress’ desire

to assure that American citizens abroad enjoy to the

maximum extent possible, the same employment oppor

tunity they enjoyed within the United States.” Brief of

Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense Fund, et al. at 15.

But in so doing, amici proverbially “put the cart before

the horse.”

First, Senate; Resolution 323 simply is not relevant to

Title VII. The resolution has no force or effect of law,

since it was a resolution, rather than a bill, and it was

not passed by both Houses. Second, the resolution was

passed nearly ten years before the passage of Title VII.

Third, it has little, if anything, to do with employment

discrimination and deals only with religious affiliation.

Finally, nowhere in the legislative history of Title VII 17

17 Senate Resolution 323 states:

Whereas the protection of the integrity of United States

citizenship and of the proper rights of United States citizens

in their pursuit of lawful trade, travel, and other activities

abroad is a principle of United States sovereignty; and

Whereas it is a primary principle of our Nation that there

shall be no distinction among United States citizens based on

their individual religious affiliations and since any attempt by

foreign nations to create such distinctions among our citizens

in the granting of personal or commercial access or other rights

otherwise available to the United States citizens generally is

inconsistent with our principles; Now therefore, be it

Resolved, That it is the sense of the Senate that it regards

any such distinctions directed against the United States citizens

as incompatible with the relations that should exist among

friendly nations, and that in all negotiations between the United

States and any foreign state every reasonable effort should be

made to maintain this principle.

S. Res. 323, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. (1956) (quoted in 102 Cong. Rec.

14330 (July 25, 1956)).

27

or in the congressional debates is there any reference to

this resolution.

In essence, the NAACP, et al., characterize !S. Res.

323 as a comprehensive piece of legislation which pro

hibited. employment discrimination. But if the resolu

tion was Intended to have that effect, Congress would

have had no need to enact Title VII. It is therefore

illogical to assume that Congress in 1956, a priori, in

tended to apply Title VII extraterritorially in 1964, or

vice versa, particularly where Congress adopted no such

specific language in Title VII. If anything, the absence

of any discussion concerning the resolution in the 1964

debates and legislative history of Title VII affirms, rather

than negates, the view that Congress did not intend Title

VII to be extraterritorially applied.

The other policy arguments of petitioner Boureslan

and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, et al., center

around the notion that it is necessary to press for non

discrimination abroad in order to assure nondiscrimina

tion at home. Br. at 16-24. In their view, the majority

opinion below allows employers to transfer their domestic

employees overseas so they can “ launder” their discrim

ination. NAACP Brief at 21. In support of this idea,

amici specifically discuss testimony presented in support

of the public accommodations laws in 1963, and generally

allude to the United States’ foreign policy concerns in

international markets. See NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Brief at 18-22, 25-30.

Their inference is flawed for several reasons. First,

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund et al., assume that Am

erican employers affirmatively will engage in discrimina

tion abroad, yet cite no support for this broad assertion.

From a practical standpoint, it is very costly to send

workers overseas and then pay for their return.' Also,

employers often must specially train workers for over

seas assignments and provide them with special language

training, compensation, terms and other conditions of

28

employment. See generally Note, Yankees Out of North

America: Foreign Employer Job Discrimination Against

American Citizens, 83 Mich. L. Rev. 237 (1984) (dis

cussing whether business and cultural familiarity require

ments may be necessary to insure that managers can

successfully integrate the Japanese management style

with American practices). The costs of such efforts are

higher than those associated with domestic employment.

At a minimum, the economic costs of discrimination

abroad are prohibitive, and serve as effective deterrents

to discourage rather than encourage employers to engage

in such practices. Thus, it would make little sense for

an employer to send a person of a certain race, sex, or

religion overseas just to be able to discriminate once

the person was outside U.S. territory.18

The more plausible scenario posed by petitioner Boures-

lan and various amici involves the United States employer

who makes the decision to deny overseas opportunities to

U.S. workers. Indeed, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s

brief acknowledges that “many decisions regarding posi

tions abroad are in fact made in the United States.” Br.

at 18. In that situation, however, the individual’s relevant

work station would be this country, thus making the em

ployer subject to Title VII. Cf., Pfeiffer v. Wm. Wrigley

Jr. Co., 755 F.2d at 559 (Judge Posner) ,19

1* The amici NAACP L.D.F., et al, argue that protected individ

uals who' know they will be discriminated against overseas will

refuse such assignments, thus employers would have “to pay a

premium to induce potential employees to work abroad. Br. at 20.

We know of no situation where that has occurred, nor do any of

the amici cite to any employer that has been willing to tolerate such

costs. No employer, moreover, is likely to escape Title YII if it

pursues such a policy, for, as shown below, discrimination occurring

within the U.S. will be covered by Title VII.

i® See also, Abrams v. Baylor College of Medicine, 805 F.2d 528

(5th Cir. 1986) (Title VII violated by exclusion of Jewish doctors

from rotations to Saudi Arabia) ; Kern v. Dynalectron Corp., 577

F. Supp. 1196 (N.D. Tex. 1983), aff’d, 746 F.2d 810 (5th Cir.

1984) (employer did not violate Title VII by requiring membership

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, EEAC respectfully urges the

Court to affirm the decision of the en banc court below.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert E. W illiams

D ouglas S. McD owell *

E dward E. Potter, P.C.

McGuiness & W illiams

1015 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 1200

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 789-8600

Attorneys for

the Amicus Curiae,

Equal Employment Advisory

Council

December 17,1990 * Counsel of Record

in Islamic faith for pilots flying into Mecca) ; EEOC Decision

No. 84-2, Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) ([ 6840 (December 2, 1983) (For

eign company that recruits in the U.S. for employment outside the

country is covered by Title VII) : EEOC Decision No. 77-1, Empl.

Prac. Dec. (CCH) jf 6557 (October 13, 1976) (Title VII applies to

religious discrimination against a Canadian employee of the Cana

dian operations of a U.S. employer where the employee makes round

trips between the U.S. and Canada).