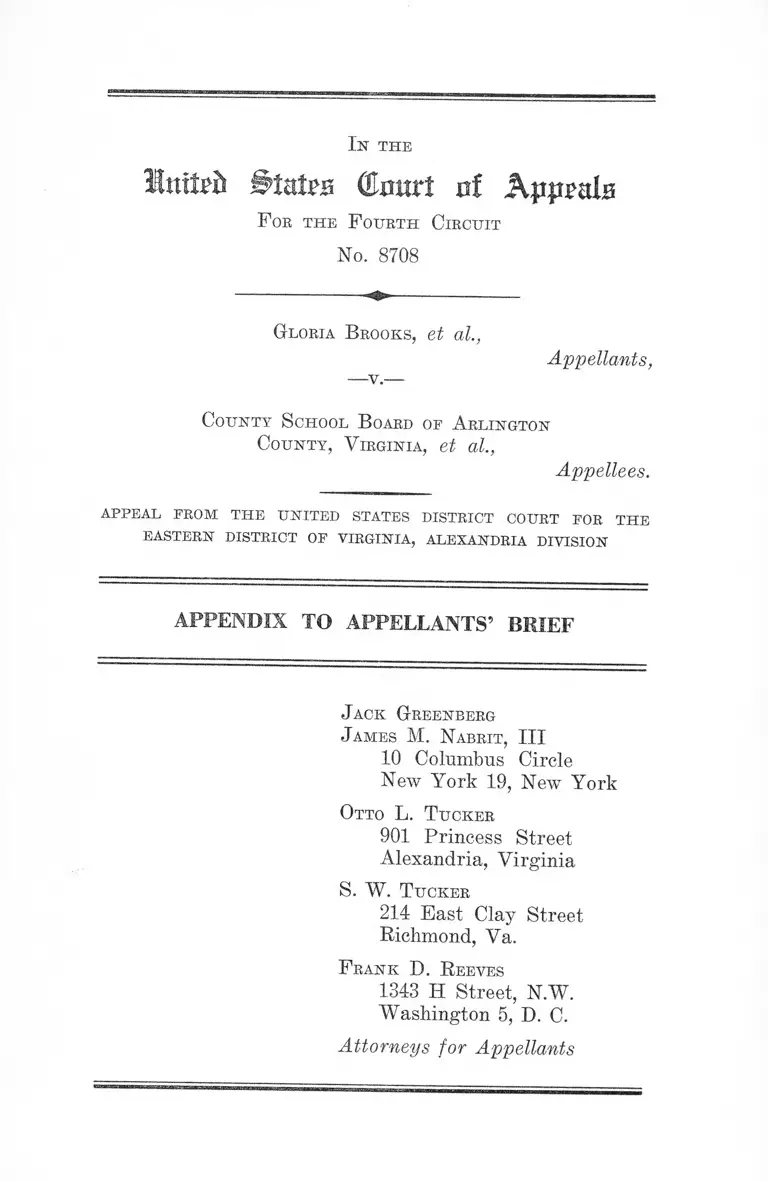

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1956 - May 2, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1956. 94807599-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/321d143c-c5de-4c73-8ee5-5d3d9685e4a4/brooks-v-county-school-board-of-arlington-county-virginia-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

States (Emtrt of Kppmls

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 8708

Gloria Brooks, et al.,

— v.—

Appellants,

County School B oard of A rlington

County, V irginia, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, ALEXANDRIA DIVISION

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

S. W. T ucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Va.

F rank D. R eeves

1343 H Street, N.W.

Washington 5, D. C.

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Memorandum by the Court, July 31, 1956 ................ 10a

Order Granting Injunction, July 31, 1956 ................ 11a

Memorandum on Motion to Amend Decree, July 27,

1956 .................. ..................... -................................... 15a

Excerpts from Transcript of Testimony—Septem

ber 11, 1957 ....... 17a

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—

Direct ..................................... 17a

Cross ....................................... 31a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Septem

ber 14, 1957 ............................................................... 35a

Supplemental Decree of Injunction, September 14,

1957 ............................................................................ 43a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Septem

ber 17, 1958 ............................................................... 45a

Supplementary Order of Injunction, September 22,

1958 ............................................................................ 60a

Memorandum on Formulation of Decree on Man

date, June 3, 1959 .......................... -........................ 61a

Decree on Mandate, June 5, 1959 ............................... 65a

Relevant Docket Entries ............................................ la

11

PAGE

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, July 25,

1959.............................................................................. 68a

Order, September 10, 1959 .................................... 73a

Order on Motion for Further Relief, September 15,

1959 ............................................................................ 75a

Order on Report Filed September 8, 1959 .............. . 77a

Order on Unopposed Admission of Two Pupils,

September 7, 1960 .................................................... 79a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Septem

ber 16, 1960 ............................................................... 80a

Motion to Dissolve Injunction ................................... 85a

Report of the County School Board of Arlington

County Dated November 9, 1961 ........................... 87a

Motion for Further R elie f.......................................... 101a

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings—Febru

ary 8, 1962 ................................................................. 109a

Testimony of Elizabeth B. Campbell—

Direct ..................................... 138a

Cross ...................................... 142a

Redirect ................................. 148a

Memorandum Opinion, March 1, 1962 ........................ 154a

Order, March 1, 1962 ......................................... 168a

Notice of Appeal ...... 169a

Relevant Docket Entries

5- 17-56

6- 22-56

7- 30-56

7-31-56

7- 31-56

8- 24-56

Date

3-29-57

3-29-57

7-18-57

7-27-57

7-27-57

7-29-57

9- 9-57

9-11-57

Filings—P roce edings

Complaint filed.

Motion to Dismiss filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: * * *

Memorandum by the Court filed.

ORDER granting injunction entered and filed.

Notice of Appeal, together with Appeal Bond in

the amount of $250.00 filed.

Mandate of the Circuit Court of Appeals filed.

Opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals filed.

Motion to Modify Injunction Decree, Points and

Authorities in Support of Motion, and Notice of

Motion filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on Motion to Modify In

junction Decree of July, 1956. Motion of Defen

dant to stay the effective date of the Injunction

Decree of this court. * * #

Memorandum on Motion to Amend Decree.

ORDER on Motion to Amend Original Injunction

Decree, entered and filed.

ORDER for Hearing on Motion for Further

Relief—entered and filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on Order for Hearing on

Motion for further relief and Order on Motion

to Intervene. Motions presented by Mr. Sim-

monds as follows: Motion to continue hearing on

plaintiffs’ motion for further relief; Motion to

dismiss the motion for further relief; Motion to

dissolve Injunction; and Motion to vacate order

2a

Date

9-12-57

9-14-57

9-14-57

9-16-57

9-17-57

9-18-57

Relevant Docket Entries

Filings—Proceedings

on motion to intervene. Said motions filed in

open court. Arguments heard. Motion to vacate

order of intervention denied. Motion to continue

hearing denied. Motion to dissolve injunction

denied. Court deferred ruling on Motion to Dis

miss Motion for Further Relief. Opening state

ment of Edwin Brown heard. Evidence of plain

tiff fully heard. Defendant offers no evidence.

Court continued case until tomorrow morning

for arguments.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day as continued from September 11, 1957

for final argument. Arguments of counsel heard.

Court takes this matter under consideration.

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law entered

and filed.

Supplemental Decree of Injunction entered and

filed.

Notice of Appeal filed. Copies mailed to Edwin

C. Brown, Spottswood W. Robinson, III, and

Oliver W. Hill.

Motion for Suspending Injunction Pending Ap

peal filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on motion for a stay of

Injunction pending appeal. Arguments of coun

sel fully heard. Court suspends the execution of

the order of injunction heretofore entered pend

ing the appeal. Order to be presented. Order

entered and filed in open court.

3a

8-26-58

8-26-58

8- 26-58

9- 2-58

Date

10- 2-57

9- 3-58

9- 4-58

Filings—Proceedings

ORDER (Robert A. Eldridge, III) entered and

filed.

Motion for Further Relief filed by plaintiffs.

Notice of Hearing on Report and Request for

Guidance filed.

Report and Request for Guidance filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on (1) Motion to substitute

Ray E. Reid as party defendant. Motion granted.

(2) Motion to intervene as party plaintiffs. Mo

tion granted. (3) Motion on Report and Request

for Guidance by the Arlington County School

Board. * * * Evidence partially heard. Court

adjourned until tomorrow morning.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day for further hearing as continued from

September 2, 1958. Parties appeared as hereto

fore. Evidence heard. Case continued to tomor

row morning.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day for further hearing as continued from

Sept. 3, 1958. Parties appeared as heretofore.

Counsel stipulated as to remaining evidence. By

Mr. Scott: Motion made at start of these pro

ceedings by the Arlington School Board renewed,

accepted and taken under consideration by the

Court. By Mr. Tucker: Motion to strike evidence

set forth in summary reports and substitute

therefor Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 10—Opinion of

Dr. Mill. Court will reserve ruling on this mo

tion. Pinal arguments heard. * * *

Relevant Dochet Entries

4a

9-22-58

10-16-58

10-21-58

1-26-59

1-28-59

Date

9-17-58

2- 2-59

2- 2-59

2- 2-59

4-21-59

6- 5-59

Filings—Proceedings

Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law en

tered and filed.

ORDER: Supplementary Order of Injunc

tion * * *

Notice of Appeal filed by plaintiff (Appeal Bond

filed.)

Notice of Cross-Appeal filed by School Board

(Appeal Bond filed).

Mandate and Opinion of the Fourth Circuit Court

of Appeals filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

to be heard on a motion to stay or modify injunc

tion granted in this cause on Sept. 22, 1958. No

tice of motion, motion for modification of injunc

tion, together with affidavit of Ray E. Reid filed

in open court. Preliminary arguments heard.

Testimony heard. Final arguments heard. Mo

tion denied. Statement by the Court heard.

Motion for Recall and Stay of Mandate filed in

Fourth Circuit January 30, 1959—received.

Memorandum from Fourth Circuit Court of Ap

peals filed January 30, 1959—received.

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law en

tered and filed.

Mandate and copy of the Opinion of the Fourth

Circuit—filed.

Memorandum on Formulation of Decree on Man

date-filed.

Relevant Docket Entries

5a

Date

6- 5-59

6-22-59

6- 29-59

7- 7-59

7- 3-59

7-25-59

7- 8-59

9- 8-59

9-10-59

9-11-59

9-11-59

9-14-59

Filings—Proceedings

Decree on Mandate entered and filed.

Report to Court filed.

Motion for Further Relief filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on Motion of plaintiff for

further relief. Plaintiff’s evidence heard. Defen

dant rested without presenting evidence. Court

adjourned until tomorrow morning.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day as continued from July 7th, 1959. De

fendant presented evidence as to certain docu

ments. Arguments of counsel heard. Court takes

this matter under consideration.

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law—en

tered and filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on Motion to Intervene and

request for temporary relief. Statement of coun

sel to the court. Order to be presented directing

the School Board to file a report.

Motion for Further Relief—filed by plaintiffs.

ORDER for Settlement of Decree—filed.

Report to the Court received and filed.

ORDER allowing intervention of Alice A. Brown,

et al—entered & filed 9-10-59.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on the settlement of Decree

Relevant Docket Entries

6a

9-15-59

9-16-59

7- 5-60

7- 8-60

7-19-60

7-19-60

7-21-60

Date Filings—Proceedings

Answer to Complaint in Intervention filed on or

about September 2, 1959, FILED in open court.

Response to Motion for further relief filed on or

about September 7, 1959, filed in open court.

Arguments of counsel heard. Court takes this

matter under consideration.

Order on Motion for Further Relief entered and

filed.

ORDER on Report entered and filed 9-8-59.

PRE-TRIAL ORDER: IT IS FURTHER OR

DERED that this cause be and it hereby is set

down for further hearing at 10:00 A.M. on July

21, 1960, upon plaintiffs’ objections, if any, to the

report to be filed by defendants as hereinabove

ordered-—entered and filed.

Report to Court dated July 8, 1960—filed.

(County School Board of Arlington County)

Objections to Defendants’ Report and Related

Action not Reported—filed.

Motion to Intervene filed.

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on further application for

admissions to schools. Answer to Complaint in

Intervention of Janice Blaunt, et al filed in open

court. Evidence fully heard. Motion to Inter

vene 3 additional plaintiffs. Motion granted.

Clerk to send notice to Counsel. Hearing on argu

ment set for September 6, 1960.

Relevant Docket Entries

7a

9-16-60

9-23-60

Date

9- 7-60

3-10-61

11-13-61

11- 13-61

12- 28-61

2- 8-62

Filings—Proceedings

ORDER On Unopposed Admission of Two Pupils

—entered and filed.

FINDINS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF

LAW entered and filed.

ORDER entered directing admission of Janice

Blount, Wade Bowles, Jr., Samuel Curtis Gra

ham, Doloris Wright, Carolyn Jones, Claude

June, David Ruffner, Vivian P. Ruffner, Lillian

Thompson and Diane Spriggs to Stratford Junior

High School, and Henry Coleman in the Thomas

Jefferson Junior High School; and further OR

DERING that further relief be denied Gloria

Brooks, Marcia Brown, Alice Brown, Elliott A.

Brown, Mabra Brown, Deidra Hallion, George

Moore, Gloria Rowe, and Thomas J. Spriggs;

and ORDERING that the Court retain jurisdic

tion of this cause.

Motion for Further Interlocutory and Permanent

Injunctive Relief received and filed.

Report of the County School Board of Arlington

County, dated November 9, 1961, with exhibits

attached thereto—filed.

Motion to Dissolve Injunction, together with

Points and Authorities—filed.

Motion for further relief filed.

COURT PROCEEDINGS: This cause came on

this day to be heard on motion for intervention.

Motion by plaintiff to withdraw motion to inter

vene. Motion granted. This cause came on fur-

Relevant Docket Entries

8a

Date Filings—Proceedings

ther to be heard on motion for further relief.

Motion by the plaintiff to withdraw motion for

further relief and to treat the motion as affirma

tive answer to the defendant’s motion to dissolve

the injunction. Motion granted. And it came on

to be heard on motion to dissolve the injunction.

Exhibits A, B and C attached to defendant’s mo

tion to dissolve the injunction admitted as evi

dence in support of this motion. Exhibits Nos.

1, 2, 3 and 4 offered by the plaintiff. Defendant

had no objection. School District Maps, 1. Ele

mentary, 2. Kindergarden, 3. Senior High, 4.

Junior High. Arguments fully heard as to the

motion to dissolve the injunction. Motion of

plaintiff to amend this action by using Para

graphs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, with

the exception of last two lines—including 13 and

eliminating paragraph 14, and to use certain parts

Strike

only; include (15, 16, 17, IS, 19) 20 and 21. Alter

certain portions of the prayer for relief. Prayer

A eliminated; Prayer B altered; Prayer C al

tered, include D and E and F. Strike paragraph

G and leave paragraph H. Exhibit A (Member

ship by Grades, 1961) made a part of the record

and to be considered as evidence. Defendant di

rected by the Court to submit report of the capac

ity of the schools and the attendance in accord

ance with the last survey. Motion to amend by

the aforesaid is hereby granted at the Bar. The

Court will take new amendments under advise

ment and notify decision as soon as possible.

Relevant Docket Entries

9a

Date

3- 1-62

3- 1-62

3-30-62

5- 4-62

Relevant Docket Entries

Filings—Proceedings

Memorandum opinion filed.

ORDER dismissing and striking case from cur

rent docket entered and filed.

Notice of Appeal received and filed. (Appeal

Bond filed—See Appeal Bond File).

ORDER Enlarging Time for Docketing Appeal

entered and filed. (Notice sent to counsel.)

10a

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict of V irginia

At Alexandria

Civil 1341

Clarissa S. T hompson et al.,

County School B oard of A rlington County et al.

Memorandum by the Court

It must be remembered that the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States in Brown v. Board of Education,

1954 and 1955, 347 U.S. 483 and 349 U.S. 294, do not compel

the mixing of the different races in the public schools. No

general reshuffling of the pupils in any school system has

been commanded. The order of that Court is simply that

no child shall be denied admission to a school on the basis

of race or color. Indeed, just so a child is not through any

form of compulsion or pressure required to stay in a cer

tain school, or denied transfer to another school, because

of his race or color, the school heads may allow the pupil,

whether white or Negro, to go to the same school as he

would have attended in the absence of the ruling of the

Supreme Court. Consequently, compliance with that ruling

may well not necessitate such extensive changes in the

school system as some anticipate.

July 31, 1956.

A lbert V. Bryan

United States District Judge

11a

In the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict of V irginia

At Alexandria

Order Granting Injunction

[ same title]

This cause came on to be heard on the 30th day of July,

1956 upon the complaint, upon the motion of the defen

dants to dismiss the complaint and the affidavits in support

thereof, upon the motions of the plaintiffs to drop certain

persons and others as parties plaintiff, upon the stipula

tion of the parties that the action not be heard before July

23, 1956, and upon the documents offered in evidence at

said hearing by agreement, and was argued by counsel.

Upon consideration whereof, after granting the said mo

tions for the dropping and adding of parties, the court

finds, concludes, and orders as follows:

1. The court treats said motion to dismiss as a motion

for summary judgment and is of the opinion thereon as

follows:

(a) That the defendant, County School Board of Arling

ton County, is suable in this court, because if acting as

charged in the complaint, it is not acting as an agency of

the State of Virginia ;

(b) That the defendant, T. Edward Rutter, Division

Superintendent of Schools of the County of Arlington, is

12a

suable in this action for the same reason as the said board

is suable;

(c) That the complaint states a claim against each of

said defendants upon which, if proved, relief can be

granted;

(d) That, as appears from the said documentary evi

dence, the plaintiffs before instituting this suit had ex

hausted all administrative remedies then and now available

to them, including the administrative steps set forth in

section 26-57 Code of Virginia 1950, in that, they have since

July 28, 1955, in effect maintained a continuing request

upon the defendants, the County School Board and the Divi

sion Superintendent of Schools, for admission of Negro

children to the public schools of Arlington County on a

non-racial basis, and said request has been denied, or no

action taken thereon, the equivalent of a denial thereof;

(e) That this suit is not otherwise premature; and

(f) That the granting of the relief prayed in the com

plaint would not constitute the regulation and supervision

by this court of the public schools of Arlington County:

Therefore, it is A djudged, ordered, and decreed that said

motion to dismiss the complaint, including summary judg

ment for the defendants, be, and it is hereby, denied.

2. The court proceeding to inquire if final judgment

may now be entered in the action, it appears to the court

from an examination of the pleadings, the said affidavits,

and the said documentary evidence, as well as from the

interrogation of counsel, that there is no genuine issue as

to any material fact in this case, and that on the admissions

Order Granting Injunction

13a

of record and the uncontrovertible allegations of the com

plaint, summary judgment should be granted the plaintiffs;

Therefore, it is further A djudged, ordered, and decreed

that effective at the times and subject to the conditions

hereinafter stated, the defendants, their successors in office,

agents, representatives, servants, and employees be, and

each of them is hereby, restrained and enjoined from re

fusing on account of race or color to admit to, or enroll or

educate in, any school under their operation, control, direc

tion, or supervision any child otherwise qualified for ad

mission to, and enrollment and education in, such school.

3. Considering the total number of children attending

the public schools of Arlington County, Virginia, and the

number of whites and Negroes, respectively, in the elemen

tary schools, junior high schools, and senior high schools,

the relatively small territorial size of the County, its com

pactness and urban character, and the requisite notice to

the school officials, as well as the period most convenient

to the children and school officials, of and for making the

transition from a racial to a non-racial school basis, and

weighing the public considerations, including the time

needed by the defendants to conform to any procedure for

such transition as may be prescribed by the General As

sembly of Virginia at its extra session called by the Gov

ernor for August 27, 1956, and weighing also the personal

interests of the plaintiffs, the court is of the opinion that

the said injunction hereinbefore granted should be, and it

is hereby made, effective in respect to elementary schools

at the beginning of the second semester of the 1956-1957

session, to-wit, January 31, 1957, and in respect to junior

and senior high schools at the commencement of the regu

lar session for 1957-58 in September 1957.

Order Granting Injunction

14a

4. The foregoing injunction shall not be construed as

nullifying any State or local rules, now in force or hereafter

promulgated, for the assignment of children to classes,

courses or study, or schools, so long as such rules or assign

ments are not based upon race or color,* nor, in the event

of a complaint hereafter made by a child as to any such

rule or assignment, shall said injunction be construed as

relieving such child of the duty of first fully pursuing any

administrative remedy now or hereafter provided by the

defendants or by the Commonwealth of Virginia for the

hearing and decision of such complaint, before ajjplying

to this court for a decision on whether any such rule or

assignment violates said injunction.

And jurisdiction of this cause is retained with the power

to enlarge, reduce, or otherwise modify the provisions of

said injunction or of this decree, and this cause is con

tinued generally.

A lbert V. Bryan

United States District Judge

Order Granting Injunction

July the 31st, 1956.

15a

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict oe V irginia

At Alexandria

Memorandum on Motion to Amend Decree

[ same title]

I. To render it current, the decree of July 31, 1956 will

be amended so that its injunction will become effective in

respect to elementary schools at the commencement of the

1957-1958 session in September, 1957. This date has here

tofore been fixed, and should stand, for the inception of

the injunction in regard to secondary schools. Deferment

of its effectuation, asked by the defendants, is not war

ranted in the circumstances of this case.

Specifically, the defendants request suspension of the in

junction while review is sought in the Supreme Court of

the recent adverse judgment, in other litigation, of the

Court of Appeals for this circuit upon the Pupil Placement

Act of Virginia. Declaring that the Act does not provide

an adequate administrative remedy, the judgment there

dispenses with compliance with the Act as a prerequisite

to application to the court for an injunction against the

maintenance of segregation. But here the right to an in

junction has already been established. Consideration of

administrative remedies will not again be reached unless

and until petition is made to enforce the injunction. Plainly,

therefore, commencement of the restraint laid in the decree

should not be postponed to a determination of the validity

of an administrative remedy.

If and when there are complaints of violations of the de

cree, the court will then inquire if the complaint has first

16a

submitted, or has adequate means of submitting, his

grievance for correction administratively. At that time it

will weigh the complaint and any administrative action

taken thereon, to ascertain whether the decree has or has

not been followed, and if not, the reason for the failure.

Thereupon it will make such further order as is appropri

ate. In this way specificity and precision will be given to

each complaint, it will be individualized, and it will be

appraised in its own peculiar environment, of course in

the light, too, of the regulations and precedents then at

hand.

II. The court must deny the plaintiffs’ request that the

decree be enlarged to include a declaration paralleling the

ruling of the Court of Appeals, in effect allowing students

to bypass the Pupil Placement Act. The sufficiency of the

Act has not been previously an issue in this suit and is

now advanced prematurely. Also, a ruling on it now would

be unwise, because for neither party is it in an appealable

posture. Finally, the holding of the Court of Appeals is

in abeyance pro tempore.

With propriety, however, we can observe that quite ob

viously the July 31, 1956 decree recognizes only an ade

quate administrative remedy—one that is efficacious and

expeditious, even apart from any question of its constitu

tionality. Pursuit of an unreasonable or unavailing form

of redress is not exacted by the decree.

III. Statutory costs will be awarded in accordance with

the motion.

Memorandum on Motion to Amend Decree

July 27, 1957.

A lbert Y. Bey an

United States District Judge

17a

Excerpts From Transcript of Testimony—

September 11, 1957

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter

* # * * *

—I ll—

# * * * *

Q. Your present occupation? A. Division Superinten

dent of Schools, Arlington County, Virginia.

Q. How long have you occupied that? A. 1952 to 1957.

Q. Continuous? A. Correct.

Q. Mr. Rutter, you are one of the defendants in the case

that is now before the Court, am I correct in that regard?

A. That is correct.

Q. How many schools are there, Mr. Rutter, in the Pub

lic School System of Arlington County? A. Approximately

forty separate buildings.

Q. Would you name, would you first tell me the number

of schools that are attended entirely by Negro students?

A. The number?

—112—

Q. The number? A. Of schools?

Q. The number of schools now attended entirely by

Negro students? A. Four.

Q. All right. How many of these four schools are high

schools? A. One.

Q. What is the name of that school? A. Hoffman-Boston

Junior-Senior High School.

Q. Now you say it is a junior-senior high school. What

grades does that school have? A. Sixth through twelve.

Q. And which of those grades are junior high school

grades and which are senior high school grades? A. Six

through nine are junior high school, and tenth through

twelve are senior high school.

18a

Q. Now let me clear this up. Under your Arlington

School System the first six grades are elementary school

grades. Am I correct in that regard? A. That’s correct.

Q. And grades seven through nine are the junior high

school grades? A. That’s correct.

Q. And nine through twelve are the senior high school

— 113-

grades ? A. Right.

Q. That is true in both Negro and white schools?

The Court: Ten through twelve, is it not?

The Witness: Ten through twelve.

Mr. Robinson: I ’m sorry.

By Mr. Robinson:

Q. Is there any other Negro senior high school facility

in Arlington County other than a part of the Hoffman-

Boston facility? A. No.

Q. Is there any other Negro junior high school facility

in Arlington County other than a part of the Hoffman-

Boston facility? A. No.

Q. Is Hoffman-Boston more than a single school plant

or is it within itself a single educational unit and in a

sense that it is a single building? A. It is a single co

ordinated educational unit.

Q. How many buildings? A. Well, there is really one

building, although we have a temporary structure situated

within about twenty feet of the building so there actually

are two buildings on the site.

Q. And what is this temporary structure being used for?

A. Well, it has been used from time to time for various

— 114-

purposes. I believe most recently for art and music.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter•—Direct

19a

Q. How temporary is this structure? By that I mean

how long has it been used for these various purposes? A.

I don’t know the number of years but I can say it has been

used for this purpose since I have known the school in 1950.

Q. Since 1950? A. Yes.

Q. At least for the period of the last six or seven years ?

A. Yes.

Q. All right, Now what are the names of the three re

maining Negro schools in Arlington County, all of which are

elementary schools? A. The first is Hoffman-Boston Ele

mentary School, located very close to the Hoffman-Boston

Junior-Senior High School. The other is the Drew Kemper

School, composed of two school buildings but is admin

istered as one elementary school, and the last is the Lang

ston Elementary School.

Q. All right, sir. Now without undertaking to name them,

how many high school facilities do you have in Arlington

County attended exclusively at the present time by white

students? A. Two.

Q. What are the names of those two schools? A. Wash

ington-Lee High School and Wakefield High School.

—115—

Q. And how many presently all-white junior high school

facilities in the county? A. May I name them one at a

time because I ’m not sure that I can give you the exact

number ?

Q. Surely. A. In the northern part of the county we

have Williamsburg, Stratford, Swanson; in the central part

of the county we would have Thomas Jefferson and in the

southern part of the county Kenmore, and a new junior

high school presently organized this year which will be

known as the Gunston Junior High School.

Q. How many? A. I believe that was seven, was it not?

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Direct

20a

Q. Seven. Do you recall the exact number—

The Court: Let us see. I have six, Williamsburg,

Stratford, Swanson, Jefferson, Kenmore, and Gfun-

ston.

The Witness: I ’m sorry. That is right.

The Court: Six'?

The Witness: I believe that is correct.

By Mr. Robinson:

Q. How many all-white elementary schools do you have?

A. I do not know the precise number, sir, but it would be

approximately thirty-seven or thirty-eight.

— 116—

Q. All right, sir. Now, Mr. Rutter, are you familiar with

that map that is posted on the board over there? A. Very

familiar.

Q. Have you had an occasion to examine that map to be

in a position to tell me whether or not it is accurate in so

far as the location of your schools are concerned and the

boundaries, of the present boundaries of your school dis

tricts? A. I believe that it is, sir.

Q. Would you walk over to the map and examine it and

state to me positively, if you can, whether or not it does

accurately disclose the location of schools and school

boundaries? A. Yes, I believe that it does.

Q. How many school districts do you have as shown on

that map, Mr. Rutter? A. This map is an attempt to

demonstrate and show the number of secondary school dis

tricts. We have a similar map showing the elementary

districts.

Q. Might I ask you this. When you say secondary, do

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter■—Direct

21a

you include only the senior high schools or do you include

the junior high schools as well? A. That’s right.

Q. Junior high school, junior and senior? A. That’s

right.

Q. All right. Now how would, how many senior high

— 117-

school districts do you have? A. Three.

Q. Would you name them, please? A. Hoffman-Boston,

Washington-Lee and Wakefield.

Q. Are these school districts in each instance all located

in a geographically contiguous fashion or do you have any

instance of a school district being divided into two or more

parts and the parts not being geographically contiguous?

A. We have one like the last you have just described.

Q. All right, and which one is that? A. Hoffman-Boston.

Q. All right. What is the difference, if any, between the

school districts so far as the racial classification of the

student residing in those districts may be concerned? A.

The Hoffman-Boston District is designated as a district

for our colored boys and girls on the high school level.

Q. And for that purpose only, am I correct? A. That

is correct.

Q. In assuming.

And that district I understand you to say has two parts ?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Would you show me those two parts? A. (Pointed.)

— 118—

The Court: Would you refer to, for the purposes

of the record—call one of them north?

The Witness: For the purpose of the record the

northern section is just south of Lee Highway, the

southern section is that portion of land surrounding

the Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School.

Testimony of T. Edward Butter—Direct

22a

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-—Direct

By Mr. Robinson :

Q. Now the Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School

is physically located within the southern of the two

Hoffman-Boston School Districts! A. That’s right.

Q. There is no Negro junior or senior high school facility

geographically situated within the boundaries of the north

ern Hoffman-Boston School District! A. That’s correct.

Q. How much distance would you say there is approxi

mately between the northern and the southern, say, esti

mating as best you can, from, say, the geographical centers

of those districts, how much distance would you say that

there is approximately between the northern and the south

ern sections of the Hoffman-Boston School District! A.

Well, I would judge it to be approximately five miles. I

believe the total distance from the northern part of the

— 119-

county to the southern is seven and it would appear to

me would be about five, five and a half or six miles.

Q. Is there any other district in Arlington County at

the secondary level embracing Negro students other than

the Hoffman-Boston School District! A. No.

Q. Now, and that is true with reference to the junior

high schools as well as the senior high schools! A. That

is correct.

Q. Come back up here.

Now as I understand you, Mr. Rutter, the Hoffman-

Boston School District with its two parts for secondary

students is based entirely upon the race of the student

residing for school administrative purposes within those

districts; am I correct in that! A. I believe that is cor

rect.

Q. All right. Now how do you figure out school districts

for white students at Arlington County! A. It is done

23a

in terms of the capacity of buildings to house a given num

ber of children.

Q. And by that you—well, suppose you explain just a

little more fully, if you will, just how you go about work

ing out the lines, the boundary lines of a school district for

the purposes of determining the schools to be attended by

—1 2 0 -

white students f A. I think a good illustration to use would

be the construction of the Williamsburg Junior High

School. As that area of the community grew and it became

evidence that additional space was required for boys and

girls of junior high school age, plans were developed and

eventually a school building was constructed in that section

of the community. A very careful study was then made

of the surrounding junior high school areas, specifically

Swanson and also Stratford. We then attempted to esti

mate the future growth of the area to which I have earlier

referred and then determine what the boundary lines of

the new junior high school would be.

Q. Am I correct in concluding from what you have said,

Mr. Eutter, that the objective in formulating boundaries

of white high school and junior high school districts is to

the extent that the capacity of the school geographically

located in that district can accommodate students is to get

each white child to the school that is closest to the place of

his residence? A. Not necessarily closest to his residence,

because there are a number of instances throughout the

community when that is not the case. In other words, it

has been necessary in a number of instances I believe, in

the past, of course, to schedule boys and girls to schools

that are not necessarily the closest to their place of resi

dence.

Q. But the reason for doing that is that the school that

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Direct

24a

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter■—Direct

— 121—

is geographically located in that district doesn’t have suf

ficient capacity to take care of all the students in that dis

trict; isn’t that the reason! A. That would he right.

Q. So that the extent to which a school facility for white

students can accommodate the children in that district, the

object in fixing these boundaries is to arrange it so that

the white student can go to the school that is the nearest

to the place of their residence? A. I believe that is cor

rect.

Q. All right. Now, Mr. Rutter, do you happen to have

with you a map showing the elementary school districts of

Arlington County? A. Yes, I do.

Q. Do you have one that we might— A. Yes.

Q. Borrow from you for purposes of putting in the rec

ord in this case with the understanding that you might not

be able to get it back? A. Very good.

Q. All right, sir.

Anybody want to see this ?

Mr. Rutter, I hand you this document and I ask you to

examine it and state, if you will, what it represents? A.

This is a map of Arlington County on which has been

—122—

superimposed boundary lines indicating the various ele

mentary school districts.

Mr. Robinson: If Your Honor please, I would like

to introduce this into evidence. Could we get it placed

on the board ?

The Court: Before you do that, I think it would

be well to mark it with an appropriate exhibit num

ber, the map that is now on there, and let it appear

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-— Direct

that it is in evidence. I take it there is no objection

to it.

Mr. Eobinson: If Your Honor please, I just under

stand that the one that is on the board has never

been introduced in evidence.

The Court: I say it will have to be admitted now.

Mr. Eobinson: Oh, I see.

The Clerk: Plaintiff’s No. 8.

The Court: Plaintiff’s No. 8.

The Clerk: You wish to mark this as plaintiff’s

No. 9?

The Court: Let the second map be plaintiff’s No. 9.

—123—

(The maps were so marked by the Clerk as

plaintiff’s Exhibits No. 8 and No. 9, respec

tively, in evidence.)

By Mr. Robinson:

Q. Now, Mr. Eutter, I say, ask you this, how many

elementary schools do you have? A. As many as we have

school buildings against approximately four.

Q. That means that you would have four Negro— A.

That’s right.

Q. Elementary. No, would it be three? A. Hoffman-

Boston, Drew Kemper and Langston; three.

Q. In other words, you have a Hoffman-Boston Sec

ondary School District and a Hoffman-Boston Elementary

School District. You determine in each instance the bound

ary lines for elementary school districts like you determine

the boundary lines for secondary school districts; am I cor

rect in that? A. That’s right, fundamentally the same.

Q. In other words, the Negro school districts are deter

mined, the boundaries are determined entirely by reason of

26a

the fact that the Negro student resides in the areas that are

surrounded by those boundaries? A. That is correct.

Q. You determine your white school boundaries in about

the same way, or precisely the same way for elementary

schools that you do for white secondary schools? A. True.

—124—

Q. Mr. Rutter, there has been considerable testimony

and some amount of correspondence introduced in evidence

coming from you indicative of a practice or policy on the

part of the school authorities in Arlington County to de

cline to admit any child to a school who has not made ap

plication for assignment to the Pupil Placement Board in

any instance where the Pupil Placement Act would require

that application to be made. Is that as a matter of fact the

policy and practice that was in effect on the opening date

of schools for the 1957-58 school session? A. Yes.

Q. In writing the letters that you did, you were simply

observing this policy, were you? A. That is correct.

Q. And it was a policy established by the School Board

or Arlington County? A. No. I was attempting to follow

to the letter of the law the laws of the Commonwealth of

Virginia.

Q. Who formulated this policy, you or the School Board?

A. Now I believe, sir, that we should distinguish between

policy and what the statutes of Virginia happen to be at the

present time. So that it’s always been our policy to observe

the law and I don’t, I would not take the position that the

Board of Education would have to formalize a policy to do

—125—

so. Therefore, what we have done this year is what we

have done in the past, obviously to observe the law.

Q. Observe the law. I see. Now were instructions issued

to the Principals of the various schools in the Public School

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-—Direct

27a

System not to admit students to school who had not applied

for assignment by the Pupil Placement Board in instances

where the Pupil Placement Act would require an applica

tion for assignment? A. That I believe is essentially cor

rect. The memoranda that went from my office to the

Principals always were designed to implement the statutes

of the State of Virginia.

Q. And at the risk of being a small amount of repeti

tion, Mr. Rutter, I just want to make certain that the record

is clear on this. In other words, the practice in Arlington

County at the commencement of the current school session

pursuant to orders and directives emanating from your of

fice, this situation, in other words, the policy and practice

were, one, that any assignment of a new student or a gradu

ating student or a transferring student would have to be

made by the Pupil Placement Board and would not be made

by the school authorities of Arlington County. Am I cor

rect to this extent? A. Placement would not be made by

the school authorities of Arlington County but they would

be made by the Pupil Placement Board. That’s right.

Q. All right. Secondly, no child would be admitted to

—126—

the Public Schools of Arlington County who for, for whom

an application was required for assignment to be made to

the Pupil Placement Board by the Act. In other words,

in those instances where the Act undertook to require that

the Pupil Placement Board make the assignment, you

would not admit a child to school unless he applied to the

Pupil Placement Board for the assignment and was as

signed to a particular school by the Board? A. That’s

correct.

Q. All right, sir.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-—Direct

28a

How many school children do yon have in the Public

School System of Arlington County! By that, Mr. Rutter,

I would like to know the total number white and Negro com

bined, elementary and secondary combined? A. I am

sorry, sir, but I cannot give you the precise figures for

this school year.

Q. Approximately? A. Because these changes are being

made every day. We have approximately 23,000. We an

ticipate 23,000 this academic year, and our experience in the

past has been that approximately five percent of that num

ber, of the total number of registered would be children of

the Negro race.

The Court: Now that is of all the schools, is it,

Mr. Rutter?

The Witness: Yes, that is all the schools.

—127—

The Court: Elementary as well as secondary?

The Witness: That is right.

Mr. Robinson: In other words, you would have ap

proximately 1,500 Negro students and you would

have approximately 21,500 white students?

The Witness: Yes.

By Mr. Robinson'.

Q. Would you be able to give us any reasonably accurate

estimate of the number of children that you would have,

white and Negro, in the elementary schools, junior high

schools, and senior high schools; would you be able to do

that? A. To give you the approximate enrollment?

Q. Yes. A. I can’t do it on the stand at this moment,

but I can secure it, the information.

Q. All right, sir. A. I can’t do that too accurately and

I would hesitate to do so.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter■—Direct

29a

Q. You would be able to supply us with that information

before leaving today? A. Yes.

Q. I would like for you to do so.

—128—

The Court: Do you have it at the desk?

The Witness: 1 am sure that there are members of

my staff here who can supply me with the informa

tion.

The Court: I wonder if you can get it now readily

and would save you from coming back to the stand.

The Witness: Would you repeat the precise—

Mr. Robinson: I would like to know, one, the num

ber of Negro elementary students, junior high school

students, senior high school students; number of

white elementary, junior high, and senior high.

The Witness: Well, we’ll be able to get the in

formation in just a few moments.

Mr. Robinson: Well, while we are waiting, let me

ask you a couple of other questions, Mr. Rutter.

By Mr. Robinson:

Q. Do you have any idea, or do you have any reasonably

accurate estimate of the number of students, the approxi

mate number of students assigned to the Public Schools of

Arlington County by the Pupil Placement Board for the

^ .12 9 -

current session? A. There are more than 2,000. I am sure

of that.

Q. More than 2,000. A. Yes.

Q. Do you have any information that would be reasonably

accurate as to approximately how many of these 2,000 would

be Negroes and how many of the 2,000 would be whites?

A. No, I do not.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-—Direct

30a

Q. I understand that so far as you know all of the schools

in Arlington County are being attended by the members of

one race only, by that I mean that there is no single in

stance of any school in the entire School System attended

by a Negro and a white child. They are all either actually

attended by all-white students or all-Negro students. Am

I correct in that conclusion? A. That’s right.

Q. And this notwithstanding the fact that 2,000 assign

ments approximately have been made by the Pupil Place

ment Board? I mean that has not been affected by reason

of the assignment? A. Presumably not.

Q. Would I be correct in my conclusion from that, Mr.

Butter, that out of 2,000 assignments made by the Pupil

Placement Board, all 2,000 of those students, if they happen

to the extent to which they are white were assigned to white

schools and all within that 2,000 figure who happen to be

- 1 3 0 -

Negroes were assigned to Negro schools without exception

so far as you know? A. So far as I know.

* % # # #

Q. Mr. Butter, were you able to get the information I

inquired about before the last recess? A. Tes. I have

these data that are as current as yesterday afternoon,

September the 10th.

Negro elementary enrollment, 946. Negro junior high

school enrollment, 311. Negro senior high school enroll

ment, 175. Total, 1,432.

White elementary enrollment, 11,421. White junior high

school enrollment, 5,697.

The Court: Start again.

The Witness: Yes, sir. I am sorry, sir.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter-—Direct

—131—

31a

White elementary enrollment, 11,421. Junior high

white enrollment, 5,697. Senior high school white

enrollment, 4,127. Total white enrollment, 21,245.

By Mr. Robinson:

Q. Mr. Eutter, you gave some testimony before the last

recess as to how you would formulate for white and Negro

students respectively just to districts. Now the processes

that have been employed for formulating school districts

for both elementary and secondary students, for both whites

and Negroes, of the present processes that you have used,

have been used for the—isn’t something brand new—they

have been used for some period of time, have they! A.

That’s correct.

Q. Say during the entire term of office that you have

occupied the office! A. I think it antedates that.

Q. Beg pardon! A. It goes beyond that.

Q. Goes back beyond that. Thank you very much. That

is all.

—132—

Cross Examination by Mr. Ball:

Q. Mr. Rutter, the Wakefield School has been men

tioned. Is that a combination junior and senior high school!

A. Yes, it is, Mr. Ball.

Q. With regard to these maps, as I understand, they are

last year’s map! A. Yes, that is correct.

Q. Local Board anything to do with making up this

year’s maps! A. We have not made any map this year,

sir, inasmuch as we no longer, of course, have any juris

diction in the placement of children in the schools so we

have not made the maps this year.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Cross

32a

The Court: You mean by that there are for this

session no district, school districts in Arlington

County?

The Witness: The districts are, sir, those that are

shown on the map, but the map is last year’s map

and we have made no changes in the map this year.

The Court: Well, do you still observe these dis

trict lines for any purpose whatsoever?

The Witness: Well, presumably they are observed

—133—

by the Pupil Placement Board, sir.

Mr. Robinson: Mr. Rutter, by that do you mean

that the Pupil Placement Act had the effect when it

went into operation, had the effect of freezing all

students, white and Negro, in the schools that they

were attending on the effective date of the Act, is

that what you have reference to in your last an

swer to the Court’s question?

The Witness: That the description that you have

just given seems to me to he quite similar to a clause

or a sentence or two, a paragraph in the law itself.

Mr. Robinson: By that I mean and I am trying to

find out now what the actual operation of this thing

has been in Arlington County when the law went

into effect, it had the effect in your interpretation

of it, it had the effect of keeping all students in the,

who were in school, in the schools that they attended

when the law went into effect, of keeping them there

unless the Pupil Placement Board transferred them

to some other school?

The Witness: That is my understanding.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Cross

33a

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Cross

—134—

Mr. Robinson: Are you familiar with the action

able results of assignments of Arlington school chil

dren made by the Pupil Placement Board? I mean

do you know in a general sort of way whether or

not so far as the students are concerned the Pupil

Placement Board has generally observed the old

1956-57 school district lines in making its own as

signments in those instances where it has made

assignments ?

The Witness: That would be my general observa

tion. Of course, I couldn’t be familiar with all the

forms and it is perfectly possible that some children

who may have attended a given school last year were

not assigned to the same school this year.

Mr. Robinson: But so far as you know, the state

ment that I just made is correct?

The Witness: I believe that is correct.

Mr. Robinson: Do the school authorities or the

Principals or any other agents, employee or repre

sentative of the School Board, or Division Superin

tendent of Arlington County make any recommenda

tions to the Pupil Placement Board as to the school

—135—

that a child should be assigned to?

The Witness: Absolutely not.

Mr. Robinson: That is all.

Mr. Hill: Let me see the plaintiff’s Exhibit 5, I

think it is.

Mr. Robinson: Mr. Rutter, of course, you are

familiar with this form, are you not?

The Witness: Indeed I am, sir.

34a

Mr. Robinson: I am calling your attention to a

section of the form that reads as follows: Informa

tion and recommendations from local school board,

if child is entering school for the first time is date

of child—wait a minute. No. I beg your pardon.

Right under that, big bold faced heading that I have

just read to you, the third printed line down, recom

mend to school to which pupil should be assigned.

Am I correct in understanding from what you have

just said that your employees in Arlington County

do not make a recommendation to the Pupil Place

ment Board as to the school to which a particular

student should be assigned as is requested by that

form?

—136—

The Witness: That is correct. We do not, and

we did not on that form.

Mr. Robinson: That is all. Thank you, Mr. Rutter.

# # # # #

The Court: Let me ask Dr. Rutter one question.

Doctor, will you stand right up where you are?

Are you familiar with these seven instances that

—1 3 7 -

students’ applications, that we are considering today?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: To your knowledge was any one of

them disqualified by reason of his scholastic records

to enter the school to which he applied?

The Witness: I would have no way of knowing

that, Your Honor. In other words, I didn’t attempt

to secure that information.

The Court: You cannot answer that?

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: All right.

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter—Cross

35a

Filed: September 14, 1957

Findings of Fact and Conclusions o f Law

Seven Negro children of school age were refused admis

sion as pupils in the public schools of Arlington County,

Va., on the opening day of the current session. The ground

of the refusal was that the applicants had not complied

with, or obeyed, the provisions of the Pupil Placement Act

of Virginia, 1956 Acts, Extra Session, c. 70. That statute

requires every child before entering a public school for

the first time, or on graduation from one school to another,

to apply to the Pupil Placement Board for enrollment. In

refusing the admission, the school principals were follow

ing the directions of the defendant County School Board

and Superintendent who, in turn, were following the Act.

These children, now called the plaintiffs, assert that the

refusal violates the injunction previously entered by this

court restraining the defendants from denying enrollment

in any public school of the county, on account of race or

color, to any otherwise qualified child. The plaintiffs move

for a supplemental decree directing the admission of these

children to the schools. The court will grant the motion.

I. In its injunctive decree the court took notice of exist

ing and future State and local rules and administrative

remedies for the assignment of children to public schools.

It directed conformance with them before the complainant

should turn to the court. Of course, the decree only contem

plated reasonable regulations and remedies. Defendants’

position that the Pupil Placement Act is such a regulation

or remedy is untenable. The procedure there prescribed is

too sluggish and prolix to constitute a reasonable remedial

process. On this point we also rely upon the reasoning of

36a

the Court of Appeals for this Circuit in School Board of

the City of Newport News et al. v. Adkins et al., July

13, 1957.

It must be remembered that we are viewing the Act in

a different frame from the setting in which it was tested

by the Court of Appeals. The Act was then appraised as

an administrative remedy which had to be observed before

the persons aggrieved could seek a decree of judicial relief.

Now the Act is measured against the enforcement of a

decree already granted. It is, too, a decree which was passed

before the adoption of the Placement Act and bears the

approval of the final courts of appeal. For these reasons

decision here need not await the outcome of the pending

effort to obtain a review of the Court of Appeals’ judgment.

This court had hoped that the initial step provided in

the Placement Act might be isolated and utilized as a fair

and practicable administrative remedy. It thought that a

requirement that a pupil first entering a school, or transfer

ring from one school to another, should seek placement

from some official or board, would not only be a reasonable,

but a necessary regulation as well, in the administration

of the school. This agency, it seemed, might validly be a

State agency exclusively—such as the Placement Board.

However, the court finds that it cannot fairly require the

plaintiffs even to submit their applications to the Board for

school assignment. The reason is that the form prescribed

therefor commits the applicant to accept a school “which

the Board deems most appropriate in accordance with the

provisions” of the Pupil Placement Act. Submission to that

Act amounts almost to assent to a racially segregated

school. But even if the form be signed “under protest,”

the petitioner would not have an unfettered and free tri

bunal to act on his request. The board still deliberates, on

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

37a

a racial question, under threat of loss of State money to the

applicant’s school if children of different races are taught

there.

II. The court must overrule the claim of the County

School Board and Superintendent that they should not be

held to answer for the denial of admittance to the plain

tiffs. In this they urge that the Placement Board had sole

control of admissions—that the School Board and Superin

tendent had been divested by the Act of every power in this

respect. As just explained, the Placement Act and the

assignment of powers of the Placement Board are not ac

ceptable as regulations or remedies suspending direct obedi

ence of the injunction. In law the defendants are charged

with notice of these infirmities in the Board’s authority.

Actually the plaintiffs were denied admission by the defen

dants’ agents—the school principals—while the defendants

had the custody and administration of the schools in ques

tion.

Hence, the refusal by the defendants, immediately or

through their agents, to admit the applicants cannot here

be justified by reliance upon the Placement Board. The

defendants were imputable, also, with knowledge that the

injunction was binding on the Placement Board. The latter

was the successor to a part of the School Board’s prior

duties; as a successor in office to the School Board, the

Placement Board is one of those specifically restrained by

the injunction.

III. We look, then, to see if race or color was the basis

for the denial by the defendants and their agents of ad

mission of the applicants to the named schools. It is im

material that the defendants may not have intended to deny

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

38a

admission on account of race or color. The inquiry is purely

objective. The result, not the intendment, of their acts is

determinative.

In this inquiry we have no administrative decision with

which to commence, save in one instance. Consequently, the

court must examine the evidence in regard to each applicant

and ascertain whether it indicates that the denial of ad

mittance was there due solely to race or color. The court

is not undertaking the task of assigning pupils to the

schools. That is the function of the school authorities and

the court has no inclination to assume that responsibility.

Carson v. Warlick, 1956, 4 cir., 238 F. 2d 724, 728. But

it is the obligation of the court to determine whether the

rejection of any of the plaintiffs was solely for his race or

color. In this light only does the court now review the

evidence.

IV . Arlington is a small county in size, but thickly popu

lated and having the appearance of a city. It has 22,677

(about) pupils in its public schools. Of these 1432 are

Negroes—946 in the elementary schools, 311 in the junior

high school (7th, 8th and 9th grades) and 175 in the senior

high school (10th, 11th and 12th grades).

All together there are 40 school buildings in the County.

These include 4 schools for Negroes—one high school, Hoff-

man-Boston (combining junior and senior) located in the

extreme southern end of the County and embracing an

elementary school with it; and 2 other elementary schools,

Drew-Kemper near the Hoffman-Boston, and Langston in

the district to be mentioned in a moment as the northern

Hoffman-Boston.

There are 2 high schools for the white children, 'Wash

ington and Lee in and to serve the northern half, and Wake

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

39a

field in and for the south half, of Arlington; there are

6 junior high schools, Stratford and Swanson among them,

scattered throughout the County for the white children; and

there are 28 elementary “white” schools, including Fillmore

and Patrick Henry.

Each school and its contiguous territory form a school

district. The boundaries of a district are drawn to include

the school population in the vicinity of the school as far

as the facilities of the school will allow. Before the creation

of the Placement Board the pupils assignable to each school

were, if otherwise eligible, limited to those who resided in

the school district. These lines have never been altered by

the School Board, but the defendants point out that the

Placement Board may or may not follow these bounds.

Apparently it has done so.

Nothing in the evidence indicates that any of the plain

tiffs is not qualified in his studies to enter the school

which he sought to enter. Each applicant applied to a

“white” school, but each lives in the district of that school

or of another nearby “white” school. Nor did the evidence

reveal a lack of space for him, or that the school did not

afford the courses suited to the applicant. Counsel for the

defendants explained that they did not adduce evidence as

to the eligibility of the applicants for their respective

schools because this was a matter within the purview of

the Placement Board. Anyway, no intimation of disquali

fication appeared as to any applicant.

A review of the evidence is convincing that the only

ground, aside from the provisions of the Placement Act,

for the rejection of the plaintiffs was that they were of the

Negro race. The rejection was simply the adherence to the

prior practice of segregation. No other hypothesis can be

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

40a

sustained in any of the seven instances. The evidence as to

the plaintiffs shows as follows:

(1) Rita and Harolyn Johnson, 15 and 16 years old, per

sonally presented themselves for admission to the Wash

ington and Lee High School on the opening day, Sept. 5,

1957. They desired to enter the 10th and 12th grades, re

spectively, and carried with them documentary evidence of

their academic proficiency, having attended schools in the

District of Columbia during the last school session. Their

residence is 2901 North Lexington Street, in the northern

extremity of the County. It was within the Washington

and Lee School District and a distance of approximately

2 miles (air line) from the school. The two other senior

County high schools were twice that distance from the

Johnsons.

They were refused admission because they had not exe

cuted the board’s placement forms. Their father declining

to allow them to complete the forms, they are now attend

ing school in the District of Columbia.

(2) Robert A. Eldridge, aged 9, wished to enter the 4th

grade. As a new arrival in the county, his father had made

application on August 15, 1957, for the enrollment of Rob

ert in Fillmore, an elementary school. He procured a place

ment form but did not file it. On the opening of school

Robert was refused admission into Fillmore for lack of the

form.

This boy lives at First and Fillmore Street, a distance

of slightly more than one city block from the Fillmore

School, but is within the School District of Patrick Henry,

an elementary school six city blocks away. A white child

living there would normally enter either Patrick Henry or

Fillmore. The nearest school used by colored children was

1.25 miles away.

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

41a

(3) Leslie Haxnm had completed the elementary courses

at the County’s Langston School and wanted to enter Strat

ford Junior High School. He was refused admission on

the opening day of school at Stratford because he had not

been assigned by the Placement Board, never having made

application.

He resides at 1900 N. Cameron Street. This address is

within what we describe as the northern Hoffman-Boston

District. This district, however, is 3.5 miles from the

Hoffman-Boston School and from the area around that

school also designated as a Hoffman-Boston District. The

northern Hoffman-Boston District is set apart apparently

because the area is occupied predominantly by negroes.

However, a white child living in the northern District would

be eligible to attend either the Swanson or Stratford Junior

High School. Swanson is something more than a mile from

the Hamm residence, Stratford slightly less than a mile.

(4) Louis George Turner and Melvin H. Turner, having

respectively finished the seventh and eighth grades in one

of the colored schools in the County, sought admission to

the Swanson Junior High school on Aug. 22, as well as

on the opening day. Not having filled out the placement

form, they were both refused admission. They live at the

intersection of 22d Street, North, and George Mason Drive.

This is within the northern District of Hoffman-Boston.

A white child in this section would ordinarily go either to

Swanson or Williamsburg Junior High School. Swanson

is less than a mile distant, while Williamsburg is about

1.25 miles away.

(5) George T. Nelson filled out a placement form and

filed it on August 19 or 26 with the principal of Stratford

Junior High School. On this application, the Pupil Place

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

42a

ment Board assigned him to Hoffman-Boston School. On

the opening day of school he was refused admission at

Stratford.

Nelson lives at 2005 North Cameron Street. This is

within the northern Hoffman-Boston District. Hoffman-

Boston School is 6 miles from his home, while Stratford

is % mile away. Swanson Junior High School is a little

further away. The basis for the Board’s placement is not

given; no reason is evident for ignoring Stratford or Swan

son. It cannot be accepted, for it is utterly without evidence

to support it.

V. The defendants and their agents, in barring the ad

mission of the complainants, did not intend any defiance

of the injunction. The bona tides of their assurance to the

court—that they believed they should not admit, the appli

cants without an assignment by the Placement Board—

cannot be doubted. However, the defendants and their

agents must now understand that the injunction is para

mount in the present circumstances and that they can no

longer refuse admittance to the plaintiffs.

The injunction will affect the school attendance very

slightly. Into a white school population of 21,245, only

seven Negro children will enter; one Negro will be with

11,421 white children in the elementary grades; and no

more than 6 Negroes among the 9,824 white high school

students. Of 36 previously “ all-white” schools in the

County, 4 will be affected by the decree, and then not to a

greater extent than 2 Negroes in any one of the 4 schools.

The supplemental decree will be effective at the opening

of the schools Monday morning, September 23, 1957.

A lbert V. Bryan

United States District Judge

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

43a

Supplemental Decree of Injunction

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict of V irginia

At Alexandria

[ same title]

Upon consideration of the motion by and on behalf of

Harolyn Johnson, Rita Johnson, Robert A. Eldridge III,

George Tyrone Nelson, E. Leslie Hamm, jr., Louis George

Turner and Melvin M. Turner that the court enter a further

decree specifically directing the defendants to admit them

to the schools to which they have applied for admission

for the session of 1957-58, and upon consideration of the

evidence and arguments of counsel for all the parties on

said motion, the court is of the opinion, on the findings of

fact and conclusions of law this day filed, that said motion

should be granted, and, therefore, it is

Ordered that the defendants, their successors in office,

agents, representatives, servants, and employees be, and

each of them is hereby, restrained and enjoined from re

fusing to admit the said movants to, or enroll and educate

them in, the said schools to which they have made applica

tion for admission, that i s :

1. Harolyn Johnson in the Washington and Lee High

School;

44a

Supplemental Decree of Injunction

2. Eita Jolinson in the Washington and Lee High School;

3. Robert A. Eldridge III in the Fillmore School or the

Patrick Henry School;

4. George Tyrone Nelson in the Stratford Junior High

School or the Swanson Junior High School;

5. E. Leslie Hamm, jr. in the Stratford Junior High

School or the Swanson Junior High School;

6. Louis George Turner in the Swanson Junior High

School; and

7. Melvin H. Turner in the Swanson Junior High

School; upon the presentation by the said movants of

themselves for admission, enrollment and education in the

said schools commencing at the opening of said schools on

the morning of September 23, 1957.

Let copies of this order be forthwith sent to counsel

in this cause.

A lbert V. B ryan

United States District Judge

September 14, 1957.

45a

Filed: September 17, 1958

Findings o f Fact and Conclusions o f Law

In the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the E astern D istrict oe V irginia

At Alexandria

[ same title]

Now, for the first time, this case comes before the court

upon an assignment of pupils made by State and local

authorities and founded on local conditions. Decision is

reduced to an administrative review. The case signally

demonstrates the soundness and workability of these propo

sitions: (1) that the Federal requirement of avoiding

racial exclusiveness in the public schools—loosely termed

the requirement of integration—can be fulfilled reasonably

and with justice if the guide adopted is the circumstances

of each child, individually and relatively; (2) that it may

be achieved through the pursuit of any method wherein

the regulatory body can, and does, act after a fair hearing

and upon evidence; and (3) that when a conclusion is so

reached in good faith, without influence of race, though

it be erroneous, the assignment is no longer a concern of

the United States courts.

In this court’s 1956 opinion, referring to the right of the

pupils to seek enforcement of the injunction, these same

propositions were suggested. But in 1957 no ground what

soever was tendered for such considerations. The opinion

then commented, “ * * * we have no administrative deci

46a

sion with which to commence, save in one instance”. Now

the premises are offered.

Weighing these, the court cannot say that as to twenty-

six of the thirty pupil-plaintiffs their applications for

transfer to “white” schools were refused without substan

tial supporting evidence. As to the remaining four, re

fusal of their applications for transfer is not justified in

the evidence. They are Ronald Deskins, Michael Gerard

Jones, Lance Dwight Newman and Gloria Delores Thomp

son.

These four are all applicants for Stratford Junior High

School; they have asked to enter the seventh grade, the

first year of junior high. Before this decision can be

effectuated by a final decree, ten days or more would

routinely elapse, carrying the effective date into October.

In the judgment of the court it would be unwise to make

the transfers as late as that in the term. The decree, there

fore, will be made effective at the commencement of the

next semester, January, 1959. This short deferment will

not be hurtful. Indeed, if the basic problem can be solved

by time, the price is not too dear.

I. The evidence upon which the assignments were made