Rice v Elmore Brief Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1947

38 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rice v Elmore Brief Appellee, 1947. cea67125-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/32843cdf-d644-41c1-aff0-1568a60014d4/rice-v-elmore-brief-appellee. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

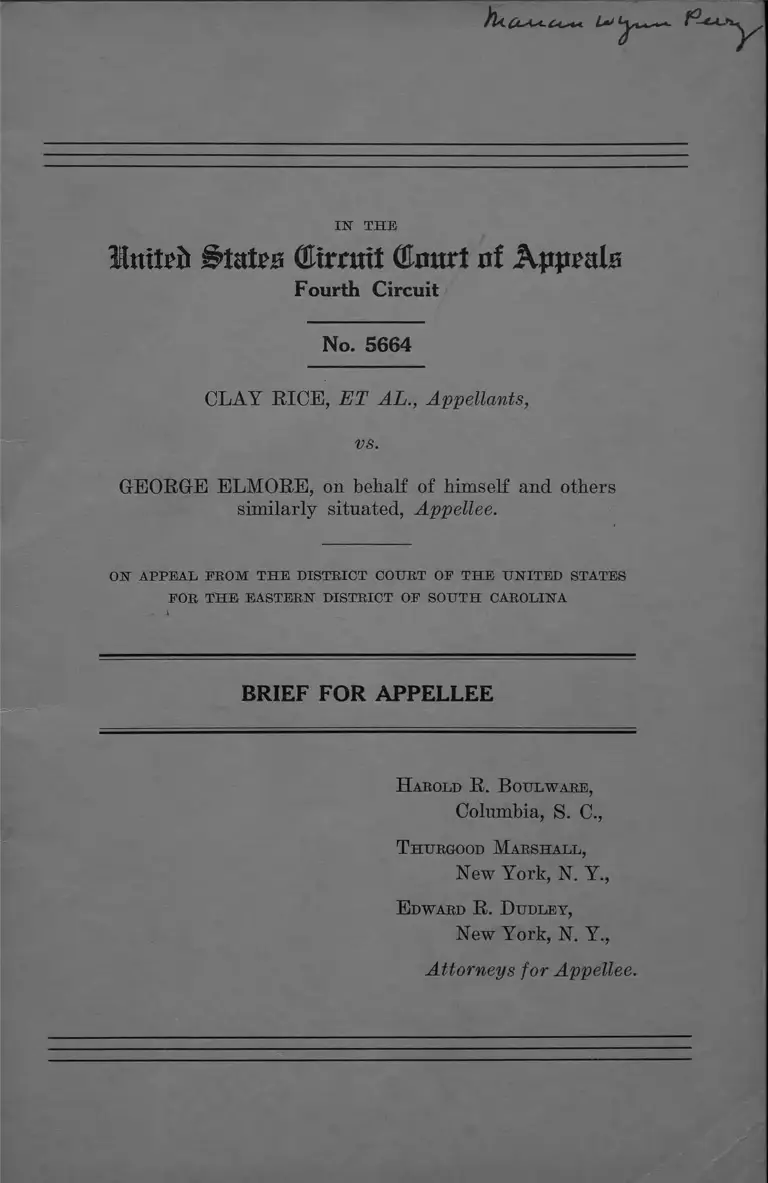

1ST THE

Ilnitzh States (fltrnttt dmtrt o! Appeals

Fourth Circuit

No. 5664

CLAY RICE, ET AL., Appellants,

vs.

GEORGE ELMORE, on behalf of himself and others

similarly situated, Appellee.

OU APPEAL EEOM THE DISTRICT COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OP SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

H arold R. B oulwaee,

Columbia, S. C.,

T hurgood M arshall,

New York, N. Y.,

E dward R. D udley,

New York, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellee.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Case__________________________________ 1

Statement of Facts_________________________________ 2

A r g u m e n t :

Preliminary Statement _____________________________ 9

I. Prior to the repeal of the primary election statutes

the Democratic Primary of South Carolina was

subject to federal control_________________________ 13

A. The right of appellee and other qualified elec

tors to vote for elected officials is a right secured

and protected by the Federal Constitution_____ 13

B. Federal Courts have jurisdiction of this case__ 20

II. Eepeal of primary statutes did not change the

status of the Democratic Primary of South Caro

lina ------------------------------------------------------------------ 25

Conclusion ________________________________________ 33

Table of Cases.

Blakeney v. California Shipbuilding Co., 16 Lab. Bel.

Bep. 571 _______________________________________ 11

Chapman v. King, 154 F. (2d) 460 (C. C. A. 5th, 1946),

cert, denied, 66 Sup. Ct. 905 (1946)_______________ 23

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 (1883)________________ 23

Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651 (1884)___________ 13

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1914)_________ 9

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935)_____________ 10

James v. Marinship Corp., 25 Cal. (2d) 721, 155 P.

(2d) 329 (1944)_________________________________ 11

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. (2d) 212

(C. C. A. 4th, 1945)______________________________ 11

11

PAGE

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1938)_________________ 9

Marsh, v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946)_____________ 11

Myers v. Anderson, 238 IT. S. 368 (1914)_____________ 9

Newberry v. United States, 256 U. S. 232 (1921)______ 14

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932)________________ 10

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927)______________ 10

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932)______________ 24

Raymond v. Chicago Union Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20

(1907) __________________________________________ 24

Robinson v. Holman, 181 Ark. 428, 26 S. W. (2d) 66

(1930) Cert, denied, 282 U. S. 804________________ 23

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 (1945)__________ 24

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944)—____________ 10

Smith v. Blackwell, 115 P. (2d) 186 (C. C. A. 4th, 1940) 23

State v. Meharg, 287 W. 670 (1926)________ _________ 26

Sterling v. Constantine, 287 U. S. 378 (1932)_________ 23

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville RR., 323 U. S. 192

(1944) ______________________________________ :___ 11

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487 (1902)_________ 13

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323

U. S. 210 (1944)_________________________________ 11

Thompson v. Moore Drydock Co., 27 Cal. (2d) 595,

165 P. (2d) 901 (1946)___________________________ 11

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1941)_________ 10

United States v. G-radwell, 243 U. S. 476 (1917)_______ 23

United States v. Mosely, 238 U. S. 383 (1915)________ 13

Williams v. International Bro., 27 Cal. (2d) 586, 165

P. (2d) 903 (1946)___________________ :___________ 11

Wallace Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 323 U. S. 248 (1944)____ 11

Other Authorities Cited.

Negro Disenfranchisement—A Challenge to the Consti

tution, 47 Col. Law Rev. 76 (1947)_______________ 22

Imtt'ft Elates dtrottt ©our! at Appeals

Fourth Circuit

Clay R ice, et al .,

Appellants,

vs.

G e o r g e E lmore, on behalf o f h im self and

others sim ilarly situated,

Appellee.

No. 5664

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statement of Case

On July 12, 1947, the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of South Carolina, entered an order

herein declaring that the denial by defendants-appellants,

of the right of plaintiff-appellee to vote in the primary

election conducted by the Democratic party of the State of

South Carolina on account of their race or color was un

constitutional as a violation of Article I, Sections 2 and 4

of the Constitution of the United States and of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments thereof. Defendants-

appellants were enjoined from denying plaintiff and other

qualified Negro electors the right to vote in Democratic

Primary elections in South Carolina solely on account of

their race or color.

The case was heard in oral argument before the Court

on the basis of stipulations of fact filed by the parties and

the testimony of one witness. Upon the hearing of the

2

case it was decided that the Court would first pass upon

the question of a declaratory judgment and injunction, and

that the prayer for money damages, alleged in the com

plaint to be Five Thousand Dollars ($5000), would be de

ferred for future submission to a jury in case it was de

termined that the plaintiff had stated and shown a cause

of action. The points raised by appellants on this appeal

have been adjudicated by the lower Court and are set out

as principal questions in appellants ’ brief. Appellees ’ reply

to these questions is contained in the Argument in this

brief.

Statement of Facts

All parties to this action, both appellee and appellants

are citizens of the United States and of the State of South

Carolina and are resident and domiciled in said State (A-

100) .

The appellee at all times material to this action was

and is a duly and legally qualified elector under the Consti

tution and laws of the State of South Carolina, and sub

ject to none of the disqualifications provided for voting

under the Constitution and Laws of the State of South

Carolina (A-101).

The Richland County Democratic Executive Committee

represents the local county unit of the Democratic party of

South Carolina (A-101).

Since 1900 every Governor, Member of the General As

sembly, United States Representative and United States

Senator of the State of South Carolina elected by the peo

ple of South Carolina in the general elections was a nominee

of the then existing Democratic party of South Carolina

(A-103).

3

During the past twenty-five years the Democratic party

of South Carolina has been the only political party in South

Carolina which has held state-wide primaries for nomina

tion of candidates for federal and state offices (A-103).

Although the officers of the Democratic party of South

Carolina vary from year to year, the membership remains

essentially the same (A-103).

The Democratic party of South Carolina has always re

stricted its membership and eligibility to vote in primaries

to white persons (A-103).

In each general election year, the Democratic party of

South Carolina repeals all existing rules and adopts new

rules for the conduct of the party and primaries for the en

suing years (A-103).

All primaries in South Carolina prior to and subse

quent to April, 1944 have been conducted in conformity to

the rules promulgated by the Democratic party of South

Carolina in each successive general election year (A-103).

All persons conducting the Democratic Primary elec

tions in South Carolina prior to and subsequent to April,

1944 conducted these primaries in strict conformity to the

printed rules of the Democratic party as amended from

general election year to general election year. (Copies of

the 1942, ’44 and ’46 rules appear in the evidence in this

case.) (A-103.)

There is no general election ballot in South Carolina.

The only printed ballots available in general elections in

South Carolina are ballots prepared by the political parties

giving only the names of their respective candidates

(A-103).

In General Election years, during the past twenty (20)

years and up to and including 1946, the then existing Demo

4

cratic party of South Carolina prepared ballots giving only

the names of its nominees for use in general elections by

any elector who might choose to use same. These ballots

were distributed by the then existing Democratic party of

South Carolina to all of the polling places throughout the

State of South Carolina in the subsequent general elections

(A-38).

A number of the Statewide Statutes formerly regulating

the primaries of all political parties in South Carolina were

repealed at the 1943 Session of the General Assembly of

South Carolina effective June 1, 1944, and on April 20,1944,

the General Assembly of South Carolina, after a session of

less than a week, passed one hundred and fifty acts repeal

ing all existing statutes which contained any reference di

rectly or indirectly to primary elections within the state,

including an act calling for the repeal of Section 10 of

Article II of the Constitution of South Carolina 1895, the

only Constitutional provision mentioning primary elections,

and set in motion the machinery to repeal that provision.

Subsequently, and on February 14, 1945, the Constitution of

South Carolina was so amended by Ratification by the Gen

eral Assembly of South Carolina of said Constitutional

Amendment (A-103).

The 1944 Special Session of the General Assembly of

South Carolina was called by the Governor ‘ ‘ for the specific

purpose of safeguarding our elections, the repealing of all

laws on the Statute books pertaining to Democratic

Primary Elections, and to further legislation allowing the

soldier to vote in the coming elections, ’ ’ and in his address

to the Joint Assembly stated: “ In my inaugural address

of January, 1943, I recommended at that time that we re

peal from our statutes, laws pertaining to primary elections.

Following up my recommendation, you erased from the

5

statute books many of our laws pertaining to primaries.

At least as many as you thought necessary at that time to

protect us under the then-existing ruling of the Supreme

Court of the United States. Since that time, in fact within

the last few days, the United States Supreme Court, in a

Texas decision, has reversed its former ruling, so that it

now becomes absolutely necessary that we repeal all laws

pertaining to primaries in order to maintain white suprem

acy in our Democratic Primaries in South Carolina,” and

also “ After these statutes are repealed, in my opinion,

we will have done everything within our power to guarantee

white supremacy in our primaries of our State insofar as

legislation is concerned. Should this prove inadequate, we

South Carolinians will use the necessary methods to re

tain white supremacy in our primaries and to safeguard the

homes and happiness of our people. White supremacy will

be maintained in our primaries. Let the chips fall where

they may!” (A-83).

The 1944 convention of the Democratic party of South

Carolina following the same procedure as in past general

election years on May 17, 1944 repealed the old rules and

adopted new rules governing the party (A-102).

The 1944 rules made no change as to the rule for mem

bership in the party and voting in the primary which

limited membership and voting in primary as in the 1942

rule to persons more than 21 years of age who were white

Democrats (A-102).

The 1946 rules extended the age limit to all white Demo

crats over 18 years of age, and added the requirement to be

able to read or write and interpret the Constitution (A-102).

The 1944 rules removed the word “ election” in most

places where it formerly appeared in the 1942 rules; re

moved all reference to statutes; changed the oath required

6

of candidates for United States Senator and House of

Representatives by adding additional pledge to support the

political principles and policies of the Democratic party of

South Carolina; permitted club secretaries to enroll per

sons in the armed forces; changed the place of filing of rolls

of party members from the Clerk of Court to the County

Chairman; provided that the pledge of candidates be filed

with the secretary of the party rather than the clerk of the

Court; provided for an application to the county chairman

rather than to a judge of competent jurisdiction to any per

son who was refused enrollment; changed the oath of voters

from requiring them to support the nominees of the party,

state and national, to duty to support the nominees of the

primary; changed the hours of opening and closing of polls

in certain cities; added to the provision for the amendment

of rules a provision that notice to amend be given the state

chairman at least five days before the convention; and

simplified rules for absentee voting in order to accommo

date servicemen. Provision for voting machines was set

up in the 1946 rules (A-51-76).

The 1944 and 1946 rules of the Democratic party of

South Carolina continued to include the word “ election” in

rules 25, 27, 32 and 48 (A-55).

In the 1942, 1944 and 1946 rules of the Democratic party

of South Carolina the actual conduct of the primary is

governed by rules 28 and 29; Rule 28 was changed in 1944

by changing time for run-off elections and removing of the

words “ or by statute” . Rule 29 remained unchanged (A-

74-75).

The general method of operating the Democratic party

of South Carolina such as election of delegates to state

conventions, election of officers, executive committeemen

and holding of county and state conventions has been in

7

the same general manner since April, 1944 as before that

time (A-103).

There has been no material change since April 1944 in

the manner in which primary elections have been conducted

in South Carolina from the manner in which they were

conducted prior to April 1944 (A-103).

There has been no material change since April 1944 in

the manner in which the Democratic party of South Caro

lina has prepared its ballots and distributed them to the

polls for use in general elections from the manner in which

this was done prior to April 1944 (A-95).

In 1936, 295,470 votes were cast in the Democratic Pri

mary for Senator and 53,770 votes for Congressman from

the Second District. 114,398 votes were cast for Senator

and 21,780 votes for Congressman in the Second District in

the ensuing general election. (Appendices filed with ap

pellee’s complaint.)

In 1938 in the first Democratic Primary for Governor

336,087 votes were cast and in the second primary 313,315

votes were cast. In the primary for nomination of Senator

336,956 votes were cast while 45,859 votes Avere cast for that

office in the general election. 58,929 votes were cast in the

primary for nomination of congressmen from the Second

District while 7,296 votes were cast for that office in the

general election. (Appendices filed with appellee’s com

plaint.)

In the 1940 Democratic Primary for Congressman for

the Second District 52,023 votes were cast while 15,126

votes were cast in the general election. (Appendices filed

with appellee’s complaint.)

In 1942 in the Democratic Primary for Senator 234,972

votes were cast and in the general election for Senator

8

22,556 votes were cast. For Congressman from the Second

District 40,965 votes were cast and 4,448 votes were cast in

the general election. (Appendices filed with appellee’s com

plaint.)

In 1944, 250,776 votes were cast for Senator in the

Democratic Primary and 97,770 votes were cast in the gen

eral election. (Appendices filed with appellee’s complaint.)

In 1946 for the office of Governor 290,223 votes were

cast in the first Democratic Primary held in August;

253,589 votes were cast in the second primary held on Sep

tember 3, 1946; and only 26,326 votes were cast in the gen

eral election for the office of Governor (A-104).

On AugTist 13, 1946, there was held by the Democratic

party of South Carolina in the State of South Carolina

and in Richland County a primary election for the choice

of Democratic nominees for the House of Representatives

of the United States, for the Governor of South Carolina,

and various other State and County offices, and on that

day the plaintiff and a number of other Negroes, all quali

fied electors under the Constitution of the State of South

Carolina, presented themselves at the regular polling place

of Ward 9 Precinct of Richland County, South Carolina,

during the regular hours that the polling place was open

and requested ballots and permission to vote in the said

primary, but the managers refused to permit them to vote

because they were not white Democrats and were not duly

enrolled, and in this refusal the managers were acting pur

suant to the rules and regulations of the Democratic party

of South Carolina and the instructions of the Chairman

and members of the Richland County Democratic Executive

Committee (A-101).

9

A R G U M E N T

Preliminary Statement

This case cannot be considered as an isolated case. It

is another step in the long struggle to receive recognition

of the right of Negro citizens to participate in the choice

of elected officials. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments were enacted for the purpose of re

moving all discrimination against Negroes and to protect

all of their rights from discrimination because of race.

However, this has not yet been accomplished. In many

states varying types of schemes were started to prevent

Negroes from voting. In the latter part of the last century

and the early part of this century two schemes for effectively

disfranchising Negroes began. These two methods were

discriminatory registration statutes (Grand-father clause)

and white primaries in the dominant part of the South,

the Democratic party.

The Grand-father clauses, even though they made no

mention of Negroes by name were declared unconstitutional

by the Supreme Court.1 After these decisions the State

of Oklahoma enacted another registration statute which

removed the Grand-father clause but discriminated against

Negroes without mentioning them by name. This statute

eventually reached the Supreme Court and was declared

unconstitutional as being in violation of the Fifteenth

Amendment.2

1 Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1914) ; Guinn v. United States,

238 U. S. 347 (1914).

2 Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1938).

10

The record as to the white primary of the Democratic

party is closely similar to that of the discriminatory regis

tration statutes. The Texas cases 8 demonstrate that after

each decision of the Supreme Court there was an effort to

circumvent the decision. After Smith v. Allwright3 4 no

further effort was made in Texas. However, South Caro

lina repealed all of its primary statutes in a deliberate

effort to circumvent this decision and to continue to prevent

Negroes from exercising their choice of candidates in the

only meaningful election in South Carolina, viz., the Demo

cratic Primary.

The fallacy of the argument of the appellants is their

reliance upon cases and theories of law outmoded since the

decision of the United States Supreme Court in United

States v. Classic,5 and Smith v. Allwright, supra. In con

sidering the rights of qualified electors to vote in primary

elections, the courts prior to the Classic case always based

their decisions on the question as to whether or not the

party conducting the primary was an agency of the state.

%

Beginning with the Classic case, the principle has been

clearly established that the proper approach to this prob

lem is first to consider the true relationship of the primary

to the electoral process rather than to consider whether or

not the party was a private or state party, or whether the

3 Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935) ; Nixon v. Condon, 286

U. S. 73 (1932) ; Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 540 (1927)

4 321 U. S. 649 (1943).

5 313 U. S. 299 (1941).

11

officials conducting the primary were private persons or

state officers.8

Appellants throughout their brief continue to confuse

the right to membership in a political party with the right

to vote in primary elections which determine who shall ulti

mately represent the people in governmental affairs, for

example, appellants in their conclusion take the position

that: “ Plaintiff has no more right to vote in the Democratic

Primary in the State of South Carolina than to vote in the

election of officers of the Forest Lake Country Club or for

the officers of the Colonial Dames of America, which prin

ciple is precisely the same” (Brief for Appellants, p. 45,

italics ours). Appellants’ entire case is based upon this

absurd position.

8 Even ̂assuming for the purpose of argument that the Democratic

party js in South Carolina a private voluntary association its action

still violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments if in fact a

state agency relationship exists. In Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501

(1946), the Supreme Court held that the due process clause of the

Federal Constitution was a limitation on the actions of a purely private

corporation since the corporation occupied a peculiar position within

the economic and political system. In Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free

Library, 149 F. (2d) 212 (C. C. A. 4th, 1945) this Court held that

smce the corporation had_ invoked the power of the state for its

creation and relied upon city funds for its existence it was in fact a

state function. Recent decisions have indicated that labor unions,

although private voluntary associations, are subject to the limitations

of the due process clause of the federal Constitution. Steele v. Louis

ville & Nashville Railroad, 323 U. S. 192 (1944); Tunstall v. Brother

hood of Locomotive Firemen, 323 U. S. 210 (1944).

Labor unions have also been prevented from infringing such rights

as the worker’s right to retain his job in a closed shop even though

the union was a private voluntary association and could not be com

pelled to accept such worker into membership. James v. Marinship

Carp., 25 Cal. (2d) 721, 155 P. (2d) 329 (1944) ; Williams v. Inter

national Brotherhood, 27 Cal. (2d) 586, 165 P. (2d) 903 (1946);

Thompson v. Moore Drydock Co., 27 Cal. (2d) 595, 165 P. (2d)

901 (1946) ; Blakeney v. California Shipbuilding Co., 16 Lab. Rel.

Rep. 571; Wallace Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 323 U. S. 248 (1944).

12

This position of the appellants, representing the last

dying gasp of the “ white primary” in this country, is in

direct opposition to the principles of our Constitution as

recognized so recently by the United States Supreme Court:

“ The United States is a constitutional democracy.

Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to par

ticipate in the choice of elected officials without re

striction by any state because of race. This grant

to the people of the opportunity for choice is not to

be nullified by a state through casting its electoral

process in a form which permits a private organiza

tion to practice racial discrimination in the election.

Constitutional rights would be of little value if they

could be thus indirectly denied. . . . ” 7

In South Carolina the Democratic party and the elected

officials of the state are synonymous. In this case we have

glaring examples of the arrogance and lack of respect for

our Constitution and governmental authority by the elected

officials of the State and the legal representatives of the

Democratic party of South Carolina. The complete dis

regard by elected officials of South Carolina for our Con

stitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court is exemplified

by the statement by the Governor of South Carolina (now

U. S. Senator) in his message to the legislature:

“ After these statutes are repealed, in my opinion,

we will have done everything within our power to

guaranty white supremacy in our primaries of our

State insofar as legislation is concerned. Should this

prove inadequate, we South Carolinians will use the

necessary methods to retain white supremacy in our

primaries and to safeguard the homes and happiness

of our people.

‘ ‘ White supremacy will be maintained in our pri

maries. Let the chips fall where they may!”

7 Smith v. Allwright, supra, at page 664.

13

The complete disregard by the legal representatives of

the Democratic party of South Carolina of governmental

authority is exemplified by their comment upon Judge

W aking ’s careful analysis of their defense as against the

decisions of the Supreme Court, that:

“ We are reminded of the story told by Boswell

in his famous ‘Life of Dr. Samuel Johnson’ to the

effect that when Dr. Johnson found it difficult or im

possible to answer the arguments of his opponent,

he would try to close the argument by saying: ‘ Sir,

you are a fool’ ” (Brief for Appellants, p. 24).

I

Prior to the repeal of the primary election statutes

the Democratic Primary of South Carolina was subject

to federal control.

A . The right of appellee and other qualified electors to

vote for elected officials is a right secured and pro

tected by the Federal Constitution.

It is too well established for argument that the right of

a qualified elector to vote for members of the House of

Bepresentatives and of the Senate is a right secured and

protected by Article I, Sections 2 and 4, and the Seventeenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.8 It is likewise

clear that the Democratic Primary in South Carolina was

subject to federal control. There can be no question that

this was the reason for the special session to repeal the

primary statutes. “ And since the constitutional command

is without restriction or limitation, the right, unlike those

8 U. S. v. Classic, supra; E x Parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651

(1884); Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487 (1902); United States

v. Mosely, 238 U. S. 383 (1915).

14

guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments,

is secured against the action of individuals as well as of

states.” United States v. Classic, supra, at page 315. This

constitutional protection extends not only to the right to

vote in the general elections, but to every primary election

where the state law has made the primary an integral part

of the procedure of choice, or where in fact the primary

effectively controls the choice. “ Unless the constitutional

protection of the integrity of ‘ elections ’ extends to primary

elections, Congress is left powerless to effect the constitu

tional purpose, and the popular choice of representatives is

stripped of its constitutional protection save only as Con

gress, by taking over the control of state elections, may ex

clude from them the influence of the state primaries. ’ ’ 9

There has never been any question that the Constitu

tion recognized the right of the federal government to con

trol general elections. For years there was doubt as to

whether Article One and the Seventeenth Amendment ap

plied to primary elections. As a matter of fact, the United

States Supreme Court on several occasions expressly re

served the question. However, in 1921 in the case of New

berry v. United States, 256 U. S. 232, the Court was faced

with a determination of the constitutionality of federal

legislation purporting to regulate primaries as well as gen

eral elections. (Federal Corrupt Practices Act, 36 Stat.

822-824 (1910).)

In deciding the Newberry case the Court divided four to

four, a ninth justice reserving his opinion on the question

of the power of Congress to control primaries under the

Seventeenth Amendment but declaring the Act unconstitu

tional in that it was passed before the Amendment was rati

fied. The Court was evenly divided on the question as to

9 U. S. v. Classic, supra, at page 319 (1941).

15

whether or not Article One applied to primary elections.

The prevailing opinion written by Mr. Justice M cK eynolds

took the position that Article One, 8. 4 related only to the

manner of holding general elections and was not a grant

of authority to the federal government to control the con

duct of party primaries or conventions. The dissenting

justices took the position that Article One, Section 4 gave

to Congress the right to regulate the primary as well as

the general election. Mr. Justice P itney in one of the dis

senting opinions went to the very core of the relationship

between the primary election, the general election and the

right of a qualified elector to vote. It was there said:

“ But why should the primary election (or nomi

nating convention) and the final election be treated

as things so separate and apart as not to he both in

cluded in S. 4 of article 1? The former has no rea

son for existence, no function to perform, except as

a preparation for the latter; and the latter has been

found by experience in many states impossible of

orderly and successful accomplishment without the

former” (at pp. 281-282).

* # * # # #

“ —nevertheless it seems to me too clear for discus

sion that primary elections and nominating conven

tions are so closely related to the final election, and

their proper regulation so essential to effective regu

lation of the latter, so vital to representative govern

ment, that power to regulate them is within the gen

eral authority of Congress. It is a matter of com

mon knowledge that the great mass of the American

electorate is grouped into political parties, to one or

the other of which voters adhere with tenacity, due

to their divergent views on questions of public policy,

their interest, their environment, and various other

influences, sentimental and historical. So strong

with the great majority of voters are party associa

tions, so potent the party slogan, so effective the

16

party organization, that the likelihood of a candidate

succeeding in an election without a party nomina-

ion is practically negligible. As a result, every voter

comes to the polls on the day of the general election

confined in his choice to those few candidates who

have received party nominations, and constrained to

consider their eligibility, in point of personal fitness,

as affected by their party associations and their ob

ligation to pursue more or less definite lines of policy,

with which the voter may or may not agree. As a

practical matter, the ultimate choice of the mass of

voters is predetermined when the nominations have

been made” (at pp. 285-286).

This view has now been adopted by the Court as the proper

interpretation of Article 1, Section 4 and of the 17th

Amendment.10

In 1927 the United States Supreme Court was again

called upon to determine the relationship of the federal

government to primary elections. Nixon v. Herndon,

supra, declared unconstitutional a statute of Texas which

prohibited Negroes from voting in primary elections of the

Democratic party. The plaintiff-in-error (plaintiff below)

maintained that the action of the legislature in prohibiting

Negroes from voting in primaries was in violation of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The defendants-

in-error contended: (1) that the act in question dealt only

with voting within a designated political party, which was

but the instrumentality of a group of individuals for the

furtherance of their own political ideas; (2) that nomina

tion is distinct from an election; (3) that the question of

parties and their regulation is political and not legal; and

(4) that the right of a citizen to vote in a primary is not

within the protection of the above-mentioned amendments.

10 United States v. Classic, supra; Smith v. Allmright, supra; Chap

man v. King, infra.

17

The Supreme Court decided that “ the objection that the

subject matter of the suit is political is little more than a

play upon words. Of course, the petition concerns political

action, but it alleges and seeks to recover for private dam

age. That private damage may be caused by such political

action, and may be recovered for in a suit at law, hardly

has been doubted for over two hundred years. . . . ” The

opinion also pointed out that: “ If defendant’s . conduct was

a wrong to plaintiff the same reasons that allow a recovery

for denying plaintiff a vote at a final election allow it for

denying a vote at the primary election that may determine

the final result.” The Court found it unnecessary to con

sider the Fifteenth Amendment because it is “ hard to

imagine a more direct and obvious infringement of the

Fourteenth Amendment. ’ ’

The next primary case, also from Texas, was Nixon v.

Condon, supra. In that case Nixon was again denied the

right to vote in the Democratic Primary and brought his

action under the Fourteenth Amendment. He had been

denied the right to vote in the primary pursuant to a reso

lution of the State Executive Committee of the Democratic

party passed pursuant to a statute authorizing state exec

utive committees of political parties to prescribe qualifi

cations of its own members and to thereby determine who

shall be qualified to vote in primaries. The Supreme Court

held that the refusal to permit the plaintiff to vote was in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment but at the same

time pointed out that: “ Whether a political party in Texas

has inherent power today without restraint by any law to

determine its own membership, we are not required at this

time to affirm or deny.”

In the Texas cases the Supreme Court approached the

problem of the primary elections by considering the rela

tionship of the political party to the state rather than

18

by considering the relationship of the enterprise, i. e., the

primary election, to the state and federal government. The

inevitable result of this line of reasoning is apparent in

the next Texas primary case.

In Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935) the Negro

elector was denied the right to vote in the Democratic Pri

mary pursuant to a resolution of the State Democratic

Convention. In the opinion of the Court denying relief to

the petitioner it was pointed out: “ Petitioner insists that

for various reasons the resolution of the state convention

limiting membership in the Democratic party in Texas to

white voters does not relieve the exclusion of Negroes from

participation in Democratic Primary elections of its true

nature as the act of the state.” The Supreme Court fol

lowing its approach in the other Texas cases of consider

ing the relationship of the party to the state rather than

the primary to the state, concluded: “ In the light of prin

ciples announced by the highest court of Texas, relative to

the rights and privileges of political parties under the laws

of that state, the denial of a ballot to a Negro for voting in

a primary election, pursuant to a resolution adopted by

the state convention restricting membership in a party to

white persons, cannot be deemed state action inhibited by

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments,” and also:

“ That in Texas nomination by the Democratic party is

equivalent to election, and exclusion from the primary

virtually disfranchises the voter, does not, without more,

make out a forbidden discrimination in this case.” The

Court also pointed out:

“ The argument is that as a Negro may not be denied

a ballot at a general election on account of his race

or color, if exclusion from the primary renders his

vote at the general election insignificant and useless,

the result is to deny him the suffrage altogether.

19

So to say is to confuse the privilege of membership

in a party with the right to vote for one who is to

hold a public office. With the former the state need

have no concern, with the latter it is bound to con

cern itself, for the general election is a function of

the state government and discrimination by the state

as respects participation by Negroes on account of

their race or color is prohibited by the federal consti

tution. ’ ’

The nest primary case to reach the Supreme Court was

United States v. Classic, supra, involving the refusal to

count the ballot of a voter in the Democratic Primary of

Louisiana. The action involved a criminal prosecution

under Sections 19 and 20 of the Criminal Code in that the

acts of the defendants violated Article One of the Consti

tution. In the Classic case the Supreme Court approached

the problem by considering the relationship of the primary

to government and concluded that the primary in Louisiana

was within the provisions of Article One of the United

States Constitution. The Court concluded that the act of

refusing to count the vote of an elector in a primary was

an interference with a right “ secured by the Constitution”

saying:

“ Where the state law has made the primary an in

tegral part of the procedure of choice, or where in

fact the primary effectively controls the choice, the

right of the elector to have his ballot counted in the

primary, is likewise included in the right protected

by Article I, Section 2. And this right of partici

pation is protected just as is the right to vote at

the election, where the primary is by law made an

integral part of the election machinery, whether the

voter exercises his right at a party primary which

invariably, sometimes or never determines the ulti

mate choice of the representative.” (313 U. S. 299,

318.) (Italics ours.)

20

It should be noted that the two tests set forth so clearly

in the Classic case are in the alternative. So that, under

the Classic case, the plaintiff in this case is entitled to re

cover where either “ the state law has made the primary

an integral part of the procedure of choice, or where in

fact the primary effectively controls the choice.”

The last primary case to be decided by the Supreme

Court was Smith v. Allwright, supra, from Texas. The

facts in the Smith case were essentially the same as in

Grovey v. Townsend and there were no changes in the rele

vant statutes of Texas. Following the reasoning in the

Classic case in approaching the problem by considering the

relationship of the primary to government rather than

whether or not the Democratic party was a private volun

tary organization, the Supreme Court not only held that

the refusal to permit Negroes to vote in Democratic Pri

maries of Texas was in violation of the United States Con

stitution but also expressly overruled Grovey v. Townsend.

With the decision of Grovey v. Townsend expressly

overruled there is now no decision of the Supreme Court

of the United States that ever raises a question as to the

full meaning of the alternative tests set forth in the Classic

case.

B. Federal Courts have jurisdiction of this case.

Appellants in their brief contend that federal courts

are without jurisdiction of this cause because no state action

is involved and there is no action on part of appellants

pursuant to state statute.

This contention is grounded in an erroneous conception

of how the courts in the light of U. S. v. Classic, supra, now

approach the problem raised by this suit. The question

which this suit raises is : What is the fundamental nature

21

of the primary here in question in which appellee seek

participation! If it is in fact the election, because in the

circumstances of the case it effectively controls the choice

in the general election, or because by state law it is made

an integral part of the procedure of choice, then it is an

election within the meaning of Article I, Sections 2 and 4, of

the federal constitution. Once it is determined that it is an

election within the meaning of these sections because of

either of these circumstances, then the right of the people

to participate in* such an election becomes a right secured

by the federal constitution, Article I, Sections 2 and 4, and

the Seventeenth Amendment.

This right is secured against the actions of individuals

as well as states. U. S. v. Classic, supra.

The jurisdiction of federal courts may, therefore, be

invoked under subdivision 1 of Section 41 of Title 28 of

the United States Code, this being an action at law aris

ing under the Constitution and laws of the United States,

viz., Sections 2 and 4 of Article I and the Seventeenth

Amendment of said Constitution, and the laws of the United

States, viz., Title 8, Sections 31 and 43 of the United States

Code.

The jurisdiction of federal courts is also invoked under

subdivision 11 of Section 41 of Title 28 of the U. S. Code,

this being an action to enforce the right of a citizen of the

United States to vote in the State of South Carolina.

This is also an action at law which arises under the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Federal Con

stitution as authorized by Title 28, Section 41, subdivision 1.

A cause of action arises here because of state action con

trary to these provisions of the Federal Constitution since,

despite the fact that all laws, including a constitutional

provision, regulating primaries in South Carolina have

22

been repealed, the Democratic party in conducting the pri

mary in 1946 was performing the same state function which

it performed prior to the repeal of all these laws in 1944.

It carries on and performs the function of choosing federal,

state and other officers, and is the only place where the

determination of selection of elected officers can be had.

It is the only place where a citizen can exercise his right

of suffh age where it will have any effect. The primary as

conducted by appellants being a state function is therefore

subject to the prohibitions of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.

The affirmative action of South Carolina in repealing

all state statutes regulating primary elections in order to

permit the Democratic party to continue discriminating

against qualified Negro electors solely on account of their

race and color is clearly state action prohibited by the Fif

teenth Amendment. The inaction on the part of the State

of South Carolina in failing to protect Negro electors from

the discrimination practised against them by the Demo

cratic party in its primaries is also such state action as is

condemned by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

to the Federal Constitution.11

The jurisdiction of federal courts is further invoked

under subdivision 14 of Section 41 of Title 28 of the United

States Code, this being an action at law authorized by law

to be brought to redress the deprivation under color of

law, statute, regulation, custom and usage of a state of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States, viz., Section 31 and 43

of Title 8 of the United States Code, wherein the matter

in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interests and costs, the

11 Negro Disenfranchisement—A Challenge To the Constitution, 47

Col. Law Review, 76, 87 (1947).

23

sum of Three Thousand Dollars ($3,000). “ Custom, or

usage, of any State” referred to in subdivision 14 of Section

41 of Title 28 was found by the Court below to be the con

ducting of the primary by the Democratic party in the

same manner and to the same end after 1944 as before.

The cases cited by appellants as controlling on the ques

tion of jurisdiction fail in every instance to defeat the

jurisdiction of the federal court in this case. On the con

trary, they may be divided into two groups:

1. Those eases decided prior to the Classic and

Allwright eases;12

2. Those cases recognizing that state action in

cludes action of a character other than legislative

enactments.13

It is not the contention of appellee that jurisdiction in

this case must rest upon some positive statutory enactment

by the State of South Carolina nor did the lower Court so

find. It is, however, a foregone conclusion beyond the

rebuttable stage in American jurisprudence that innumer

able types of action by a state, other than legislative action

may validly constitute state action within the meaning of

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution.

Executive Action may be State Action. Sterling v. Con-

stantine,14

12 U. S. v. Gradwell, 243 U. S. 476, 61 L. ed. 857 (1917) ; New

berry v. U. S 256 U. S. 232, 65 L. ed. 913 (1921); Smith v. Black-

well (C. C. A. 4th), 115 Fed. (2d) 186 (1940) ; Civil Rights Cases,

109 U. S. 3, 27 L. ed. 835 (1883) ; Robinson v. Holman, 181 Ark. 428,

26 S. W. (2d) 66 (1930) (cert, denied 282 U. S. 804, 75 L. ed. 722).

13 U. S. v. Classic, supra; Smith v. Allwright, supra; Chapman v.

King, 154 Fed. (2d) 460 (cert, denied 60 Sup. Ct. 905, 90 L. ed.

1025) (1946).

14 287 U. S. 378 (1932).

24

Administrative Action may be State Action. Raymond

v. Chicago Union Traction Co.ls

Judicial Action may be State Action. Powell v. Ala

bama.15 16 17

Any state officer acting under color of state law although

committing an act outside the scope of duty. Screws v.

U. S .17 and Nixon v. Herndon, supra.

Jurisdiction is conferred where the state law has made

the primary an integral part of the procedure of choice,

or, where in fact the primary effectively controls the choice,

as here, U. S. v. Classic, supra.

The question of jurisdiction in this type of case is clear

from the opinion in Smith v. Allwright, supra, by Justice

R eed, who states:

“ We are thus brought to an examination of the

qualifications for Democratic primary electors in

Texas to determine whether state action or private

action has excluded Negroes from participation.

Despite Texas’ decision that exclusion is produced by

private or party action, Bell v. Hill, supra, federal

courts must for themselves appraise the facts leading

to that conclusion. It is only by the performance of

this obligation that a final and uniform interpreta

tion can be given to the Constitution, ‘ the Supreme

Law of the Land’ ” (at p. 662).

While the Texas statutes were present in the Smith case,

the Court certainly did not close the jurisdictional door on

a situation where, “ This grant to the people of the oppor

tunity for choice is not to be nullified by a state through

15 207 U. S. 20 (1907).

16 287 U. S. 45 (1932).

17 325 U. S. 91 (1945).

25

casting its electoral "process in a form which permits a

private organization to practice racial discrimination in

the election. Constitutional rights would be of little value

if they could be thus indirectly denied.” (Italics ours),

Smith v. Allwright, supra.

From this argument, only one conclusion can be deduced

—the State of South Carolina cannot deliberately cast its

electoral process in a form permitting an alleged private

organization to perform an essential governmental func

tion and at the same time to practice racial discrimination

in the election that consistently determines who shall rep

resent the State of South Carolina in the United States

Government.

II

Repeal of primary statutes did not change the

status of the Democratic Primary of South Carolina.

The electoral procedure in South Carolina is divided

into three main steps: registration, primary and general

election. The first and third of these steps are still cov

ered by state law. (See: Art. II, Constitution of South

Carolina.) The second step, the primary election, is pres

ently free of statutory regulation. However, the Democratic

Primary is still unquestionably an integral part of the pro

cedure of choice and participation therein must be kept free

of restrictions based on race or color if the right to vote as

secured by the Constitution, is to be or have any real mean

ing. The Democratic party has operated as a monopoly in

South Carolina and in the past forty-seven or more years

its candidates have won every election for governor, repre

sentatives and senator.18

18 See Stipulations; see also Hesseltine, “ The South in American

History” , at pages 537, 573-81, 599, 616. Also see Note, “ Negro

Disenfranchisement— A Challenge to the Constitution,” 47 Col. L.

Rev. 76 (1947).

26

The importance of the primary has long been recognized,

and many states including South Carolina in view of this

have subjected these primaries to varying degrees of state

control.19

From 1888 to 1915, the State of South Carolina main

tained varying degrees of statutory control over primary

elections. In 1915 the General Assembly of South Carolina

enacted comprehensive election laws providing for full stat

utory control of primary as well as general and special elec

tions. Piior to April, 1944, statutes of South Carolina

regulated the primary as an integral part of the procedure

of choice of senators and representatives within the mean

ing of Article I, section 2, of the United States Constitution

and the Seventeenth Amendment thereto.

In 1941 the United States Supreme Court decided

United States v. Classic (supra). Athough this case did not

expressly overrule Grovey v. Townsend (supra) it was ob

vious that the two decisions were in conflict and that the

Classic case being the later decision would be controlling.

On April 3, 1944, the Supreme Court of the United States

in the case of Smith v. Adlwright (supra) removed any

doubt as to the applicability of the decision in the Classic

State v. Meharg, 287 S. W . 670, 672 (1926). One of the major

reasons for the development of the primary election was that in “ the

South, where nomination by the dominant party meant election, it was

obvious that the will of the electorate would not be expressed at all

unless it was expressed at the primary” . Charles Evans Hughes,

o lo ,| Fatc ° f the Dlrect Primary,” 10 National Municipal Review,

21, 24. See also: Hasbrouck, “ Party Government in the House of

Representatives” (1927), 172, 176, 177: Merriam and Overacker,

Primary Elections” (1928), 267-269.

On the great decrease in the vote cast in the general election from

that cast at the primary in the “ one-party” areas of the country, see

164 rf 1940 Ŝt0ne^’ “ Suffrage in the South,” 29 Survey Graphic 163,

20 See: Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1942.

27

case to cases where Negroes are denied the right to vote in

a Democratic Primary which is an integral part of the elec

tion machinery of a state. It was held that the right to

participate in a primary could not be nullified by a state

through casting its electoral process in a form which per

mits a private organization to practice racial discrimination

in the election.

Eecognizing the applicability of such a decision to South

Carolina, the Governor of that State, a member of the

Democratic party of South Carolina, immediately called a

special session of the General Assembly of that state to

meet on April 14, 1944. The sole purpose of such special

session was to take legislative steps intended to evade and

circumvent the decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States in the case of Smith v. Allwright, supra.

In his message to the General Assembly of South Caro

lina called in special session, the Governor of South Caro

lina stated: “ I regret that this ruling by the United States

Supreme Court has forced this issue upon us but we must

meet it like men” ; and: “ History has taught us that we

must keep our white Democratic Primaries pure and un

adulterated so that we might protect the welfare and honor

of all the people of our state.” The Governor called for

the repeal of all statutes mentioning primary elections and

in conclusion stated: “ If these statutes are repealed, in my

opinion, we will have done everything within our power to

guarantee white supremacy in our primaries of our state

insofar as legislation is concerned. Should this prove in

adequate, we South Carolinians will use the necessary meth

ods to retain white supremacy in our primaries and to safe

guard the homes and happiness of our people. White su

premacy will be maintained in our primaries. Let the chips

fall where they may! ’ ’

28

After a session of less than a week the General As

sembly of South Carolina, composed solely of members of

the Democratic party of South Carolina, on April 20, 1944,

passed one hundred and fifty (150) acts repealing all exist

ing laws which contained any reference, directly or indi

rectly, to primary elections within the state, including an

act calling for the repeal of the only constitutional provi

sion mentioning primary elections and set in motion the

machinery to repeal that provision. Subsequently the Con

stitution was so amended.

In 1943 the General Assembly of South Carolina re

pealed several of the statutes relating to the conduct of

primary elections to become effective June 1, 1944. (Acts

of 1943, No. 63, p. 85.) The General Assembly of 1944 at

the Special Session repealed all of the laws relating to the

conduct of primary elections including those mentioned

above to become effective upon approval of the Governor.

These bills were approved on April 20, 1944.

There can be no doubt of the intention of the Governor

and General Assembly of South Carolina. When the 1943

General Assembly repealed certain of the primary statutes

the case of Smith v. Allwfight was pending. Assuming that

the case would be decided during the October, 1943 term

of the Supreme Court the effective date of the statute was

moved up to July 1, 1944. So that, when the case was de

cided in April 3, 1944 in such manner as to be a precedent

applicable to South Carolina, all of the primary laws in

cluding those in the 1943 Act were repealed to take effect

immediately upon approval by the Governor. It is stipu

lated and agreed that all of the members of the General As

sembly and Governor were Democrats. All possible doubt

of the intention of the Governor and General Assembly is

removed upon reading the Governor’s Call of the Special

Session and his message to the General Assembly.

There has been no material change in the Democratic

party or the Democratic Primary of South Carolina since

the repeal of the statutes. This is clear from the Stipula

tions (A-33-39) and the testimony of Senator Baskin (A-

51-77).

The party operated under rules prior to 1944 which were

changed every two years and now operates under rules

adopted in the same manner. After the 1944 repeal of

the statutes the rules were changed to remove all reference

to statutes and to change the words “ primary election” to

“ primary” and “ nominating primary” .

However there has been no fundamental change in the

method by which the Democratic Primaries have been con

ducted in South Carolina. Judge W aring in his opinion

stated:

“ From the stipulations and the oral testimony

and from examination of the repealed statutes and

of the rales of the State Democratic Party which

were put in evidence, we may briefly summarize the

organization and methods of the Democratic Party

in this State, both before and after 1944. Prior to

1944, as shown by the statutes set forth in the Code

of South Carolina and from an examination of the

rules of the party published in 1942, the general

setup, organization and procedure of the Party may

be generally stated as follows: In the year 1942 (a

year wherein certain primaries and general elections

were to be held) organizations known as clubs in

various wards (in cities), voting precincts, or other

subdivisions, met at a time and places designated by

the State organization. The members of these clubs

were the persons who had enrolled to vote in the

primary held two years before and whose names

were on the books of the clubs, which were the voting

lists used at such preceding primary. At these club

meetings, officers were elected, including a County

30

Executive Committeeman from each club and also

delegates to a County Convention. Shortly there

after a County Convention was held in each County

in the State, where the delegates elected its Con

vention officers, including a member of the State

Executive Committee and delegates to the State Con

vention. And shortly thereafter a State Convention

was held, at which these delegates from the County

organizations assembled, elected their presiding offi

cers and a Chairman of the State Executive Com

mittee (composed of one committeeman from each

County), and made rules and regulations for the

conduct of the Party and of primaries. These rules

and regulations were in conformity with the statute

law of the State. The State Executive Committee

was the governing body and the Chairman its chief

official. The Convention repealed all previous rules

and regulations and adopted a new set, these being

however substantially the same as before with some

slight amendments and changes, and of course new

provisions for dates of primaries and other details.

In 1944 substantially the same process was gone

through, although at that time and before the State

Convention assembled, the statutes had been repealed

by action of the General Assembly, heretofore set

out. The State Convention that year adopted a com

plete new set of rules and regulations, these however

embodying practically all of the provisions of the

repealed statutes. Some minor changes were made

but these amounted to very little more than the usual

change of procedure in detail from year to year. The

parties to this cause have filed schedules setting forth

the detailed changes, the one side attempting to show

that the changes were of form and not of matter,

and the other attempting to point out material

changes. One of the main items of change was to

strike out the word ‘ election’ throughout the rules.

It was undoubtedly the intention of the parties in

charge of revamping the Democratic Party to elimi

nate the word ‘ election’ wherever it occurred in the

31

rules, substituting instead the word ‘ primary’ or

‘ nominating primary.’ In 1944 the State Convention

also elected delegates to the National Democratic-

Convention as it had always done in years of Presi

dential Elections.

In 1946 substantially the same procedure was used

in the organization of the Democratic party and an

other set of rules adopted which were substantially

the same as the 1944 rules, excepting that the voting

age was lowered to 18 and party officials were allowed

the option of using voting machines, and the rules

relative to absentee voting were simplified (absentee

voting had heretofore been controlled by certain

statutes repealed in 1944. (See Code of S outh

Carolina, S ections 2406-2416.) It is pointed out

that the word ‘ election’, although claimed to have

been entirely eliminated, was still used in Buies 25,

27, 32 and 48” (A-93-95).

Appellants certainly will not deny that it is the function

of the state to conduct elections for state and federal officers.

The Democratic party is in reality carrying on this function

for the state. This fact receives its emphasis from the

revelation that the general election in South Carolina has

become a mere formality as the following excerpt from the

Stipulation in this cause indicates:

‘ ‘ In the Democratic Primary of August, 1946,

290,223 votes were cast for the office of Governor.

In the Democratic Primary held on September 3,

1946, 253,589 votes were cast for same office. In the

general election of November 12, 1946, there were

26,326 votes cast for the office of Governor.”

Prior to 1944, the actual machinery of the Democratic

Primaries in South Carolina was controlled by rules promul

gated by the Democratic party. Since 1944, primary elec

tions in South Carolina have been conducted pursuant to

32

rules of the Democratic party (A-75). The actual conduct

of the primary election has not changed. Voters in the

primary elections are required to take oaths almost identical

with the oath prior to 1944. The testimony of Senator

Baskin reveals that with the exception of the repealed

statutes, the Democratic Primary is operating in essen

tially the same manner as before except that voting age

was lowered to eighteen; voting machines were established;

and results of the primaries are given to party officials

rather than county officers. The question of whether ex

penses for primaries are paid by state or party is immate

rial since the decision in Smith v. Allwright, supra.

The true position of the primary in the “ procedure of

choice” of federal and state officers in South Carolina is

made even clearer by a consideration of the method of

holding general elections. In this case we are considering

the right of the plaintiff and other Negro electors to exer

cise a meaningful choice of elected officials. They can now

vote only in the general election. There are no general bal

lots. They must either use the ballots printed by one of the

parties or write out their own. With this procedure it is

even more difficult to exercise a meaningful choice than in

either Louisiana or Texas. The Court can most certainly

take judicial notice of the general futility of write-in cam

paigns on a state-wide basis. Political parties, party control

of its voters, and the cost of political campaigns are reali

ties which cannot be ignored.

We, therefore, submit that the Democratic Primary in

South Carolina meets both of the alternative tests recog

nized in the Classic case. The Chapman case, relied on by

defendants, does not limit in any way the decision in the

Classic case. In the first place it is impossible to reconcile

some of the language in the opinion with the actual deci

33

sion. In addition the Chapman ease was based on Sections

31 and 43 of Title 8 and the Fifteenth Amendment and did

not embrace Article One of the United States Constitution

as in the Classic case.

Conclusion

Onr Constitution is a living instrument. The rights

protected have never been fully enumerated. Basic civil

rights grounded in the Constitution cannot he revoked by

technicalities. In South Carolina the Democratic party has

for years controlled the voters, the legislature, the State,

and its elected representatives in Congress. It is impos

sible to discern the line between the Democratic party and

the State of South Carolina. The repeal of the primary

statutes was a deliberate attempt to evade the decision of

the United States Supreme; Court and we respectfully

submit that it is the duty of this Court to give our Con

stitution the meaning recognized by that Court. Negroes

of the South have been denied the right to vote by one

subterfuge after another. Discriminatory registration stat

utes were changed and changed and there was law suit

after law suit until the United States Supreme Court in Lane

v. Wilson, supra, held that the Fifteenth Amendment “ nulli

fies sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of dis

crimination.” The discriminatory primary statutes were

changed and changed and there was law suit after law suit

until the Classic case and then Smith v. Allwright. After

these decisions it seemed that the right of qualified electors

to choose their representatives was finally settled. How

ever, South Carolina seeks to continue its discrimination

against Negro voters by repealing the statutes and continu

ing to operate in the same manner as before. This delib

erate effort to circumvent the decisions of the United States

34

Supreme Court is another challenge to our ability as a

nation to protect the rights of all of our citizens in practice

rather than in theory.

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the United States District Court should be affirmed.

H arold E . B oulware,

1109^ Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

E dward E . D udley,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

T hurgood M arshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Attorneys for Appellee.