Petitioners' Response to Respondents' Motion for Relief from Judgment

Public Court Documents

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Petitioners' Response to Respondents' Motion for Relief from Judgment, 101db7f5-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/328711e0-251a-46ed-bdbd-d981f39fc071/petitioners-response-to-respondents-motion-for-relief-from-judgment. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

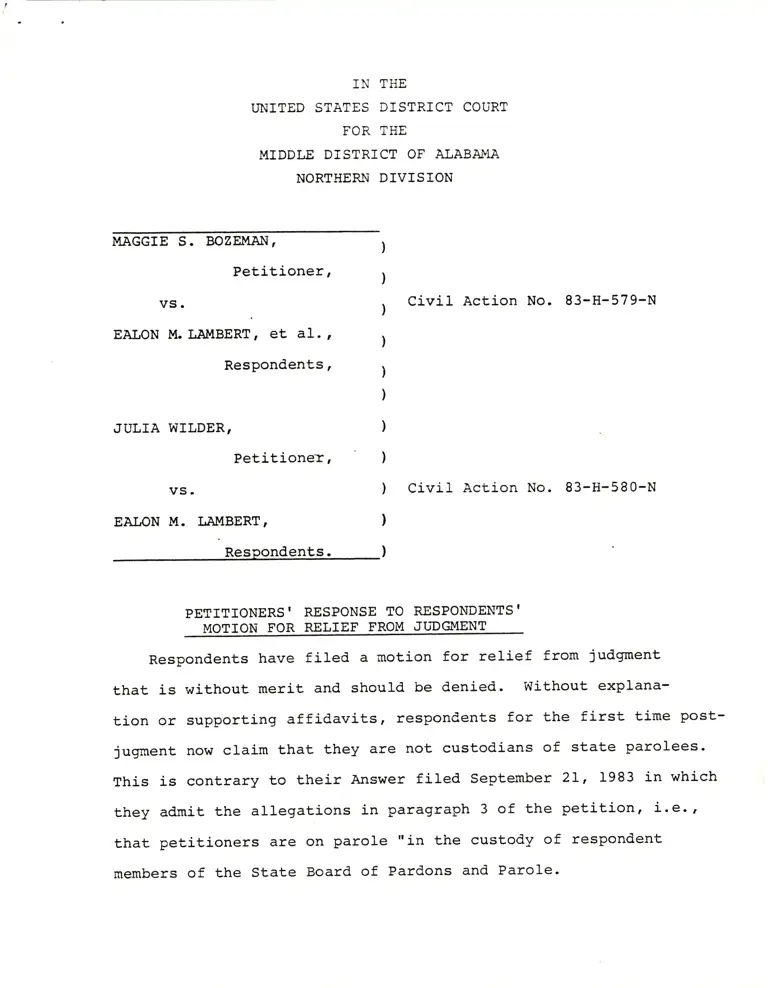

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTR]CT COURT

FOR THE

I'IIDDLE DISTRICT OF ATABAI"1A

NORTHERN DIVISION

I4AGGIE S. BOZEMAN,

)

Petitioner,

)

, civil Action No. 83-H-579-Nvs.

EAI,ON }T. I,AIIIBERT , Ct tsl. ,

}

ResPondents,

)

)

JULIA WILDER, )

Petitione:, )

vs. ) Civif Action No. 83-H-580-N

EALON l'1. LAMBERT , I

Respondents. )

PETITIONERSI RESPONSE TO RESPONDENTSI

MOTION FOR RELIEF FROM JUDGMENT

Respondents have filed a motion for relief from judgment

that is without merit and should be denied- Without explana-

tion or supporting affidavits, respondents for the first time Post-

jugrment now claim that they are not custodians of state parolees.

This is contrary to their Answer filed September 21, 1983 in which

they admit the allegations in paragraph 3 of the petition, i.e.,

that petitioners are on parole "in the custody of respondent

members of the state Board of Pardons and Parole.

As parolees, petitioners properly named as respondents

the members of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Parole and

their parole officer. The Advisory Committee Notes to Rule 2,

28 fol. 52254 suggest that where the applicant is on parole,

the named respondents shall be "the particular probation or

parole officer responsible for supervising the applicant, and

the official in charge of the parole or probation agencyr ot

the state correctional agencyr ds appropriate. " The Advisory

Committee Notes also state that where there is some ambiguity

about the proper respondent the state attorney general is in

the best position to inform the court. The Alabama Attorney

General did just that by filing an answer conceding the named

respondentsr custodial relationship. This is consistent with

Alabarna law. See, e.g., Pinkerton v. state, 29 A1a. App.

472, 198 So.I57 (194.0) (che board of pard.ons and parolees

has like and'complete jurisdiction and authority over all

parolees).

Respondents' motion simply misconceives the meaning of the

statutory phrase "person who has custody over Ithe petitioner] "

in 28 U.S.C. 52242 by ignoring the reason why such a Person

must be named as the respondent in a habeas corPus proceeding.

The reason is to assure that if the writ is issued, it will be

served upon a person who has the power to produce the body of

the petj.tioner in courtr so that the court may then order what-

ever disposition of the petitioner's body "Iaw and justice

require" (28 U. S. C. 52243) . See Atrrens v. C1ark, 335 U. S. 188,

190 (1948) (" [a] Ithough the writ is directed to the person in

-2-

r^rhose custody the party is detained, . the statutory scheme

contemplates a procedure which may bring the prisoner before

the court'r). See, a}so, 3 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES 129-131

(5th €d., Dublin L7751.

There is no doubt here that the Board of Pardons and

Paroles had the power to cause the petitioners to be retaken

into physical confinement. See Ala. Code L975, 515-22-31. It

is the Alabama agency having power to transfer prisoners into

the hands of federal or oirt-of-state authorities (see A1a- Code

L975, S15-22-24llll, and could obviously produce the petitioners

in federal court pursuant to a writ. It also has the power

to relieve the petitioners of all consequences of their challenged

convictions, by pardoning them. See Ala. Code L975, 515-22-45 (a).

Orders issued to the Board, can fuI1y effectuate every aspect of

the federal habeas corpus jurisdiction, and the members of the

Board are therefore the appropriate respondents in this case.

The belated contention that they are not is a disingenuous qibble-

" [W] e have consistently rejected interpretations of the habeas

corpus statute that would suffocate the.writ in stifling formal-

isms or hobble its effectiveness with the manacles of arcane

and scholastic procedural requirements." Henslev v. l'tunicipal

Court, 411 U.S. 345, 350 (1973).

Even if petitioners should have also named the warden of

the prison in which petitioners spent less than two weeks before

their ten month work release and ultimately thej-r parole, such

a defect is a mistake of form on1y. It is not jurisdictional.

West v. Louisiana, 478 f'.2d 1026, L029-31 (5th Cir. 1973), adhered

to on this point by court en banc, 510 F.2d 363 (1975); 17 Wright

and Mi1ler, Federal Practice and Procedure: Jurisdiction 54268

-3-

at 696 (1978). See also Copeland v. Mississippi ' 4L5 F' Supp'

l27l(N.D.Miss.1976l.InHumphreyv'Cadv'405U'S'504'506

n.2(LgTzl,theSupremeCourtnotedthatwhereapetitionerwas

released on parole to the secretary of state Department of

Health and social services after filing a cert petition' the

appropriate procedure was simply to substitute the secretary for

the prison warden aS respondent. Accord, DeSousa v. Abrams, 467

F. Supp. 51I (D.C. N.Y. LgTg) (defect can be cured by amending the

petition but, in any event, the Attorney General was in a position

to respond to the petition even though warden not named)'

Respondents cite dicta from other cases to suggest erroneously

that naming the wrong respondent is a jurisdictional defect' Accord-

ingtowrightandMiller,supra,thisismerelydictawhich

,,ordinarily aPPears as part of a decision in which the court also

rejects the -petition on the merits. " Moreover, the cases cited by

respondents can be distinguished easily because first' not a single

case involves a petitioner who was on parole at the time of filing

the petition. For example, the petitioner in Billiteri v' united

States Board of Parole , 54L F.2d 938 (2d Cir ' L9761 was a prisoner

who was physically incarcerated in the federal penitentiary under

the control of the warden throughout the district court litigation'

olson v. Californis Adult Authoritv, 423 F.zd L326 (9trr Cir' L97 )

involved the complaint of a state prj-soner that he had not been

released on parole. Similarly, the petitioners in Bohm v' Alaska'

320 E.2d 851 (9th Cir. 1963), Mo1es v' Oklahoma' 384 F' Supp'

-4-

1148 (W. D. Okla. L974) and Osborn v. Commonwealth, 27'7

F. Supp. 756 (W. D. Pa. L976) were all confined in state or

federal correctional institutions at the time they filed

their habeas corpus petitions.

Second, the cases cited by Respondents do not hold that

it is improper for a parolee to name the parole board as cus-

todian. They expressly acknowledge the contrary. For example,

in Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U.S. 236 (1963), the Supreme Court

reversed the lower courtts decision not to allow members of

the state board of parole to be added as respondents, stating

at 243 "petitioner's parole status places him in the custody

of members of the parole board and if he can prove his allega-

tions, this custody is in violation of the Constitution. " Indeed,

since the petitioner was released on parole, the case was,

however, rendered moot as to the superintendent of the state

penitentiary. The Billiteri court also acknowledged that after

a prisoner has been released on parole, the parole board may

properly be considered a custodian for habeas corpus purPoses,

541 F.2d at 948. Accord, Hensley v. Municipal Court, 411 U.S.

34s (1e73).

The purposes of the federal statutory requirement that the

respondent named in the petition be the immediate custodian

were thus served in the instant case when petitioners named the mem-

bers of the parole board. At most, one could argue that petitioners

were equally in the constructive custody of the named respondents and the

Iegal custody of the warden. This d.oes not support the cIaim,

-5-

however, that the warden should be substltuted for the named

respondents or that the named respondents should be relieved

from the Court's judgrnent. Since the members of the parole

board are able to comply in aIl respects with the Judgrnent

of this Court, they are ProPerly named as respondents. There

is no point, therefore, in requiring petitioners to amend their

petitions nunc pro tunc to name petitioners' former warden as

an additional respondent. Indeed, to do so would undermine

the very nature of the writ of habeas corPus. As the Supreme

Court has he1d, "The very nature of the writ demands that it

be administered with the initiative and flexibility essential

to insure that miscarriages of justice within its reach are

surfaced and corrected." Harris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 286, 29L

(1e6e).

For these reasons the motion for relief from judgment should

be denied. If the Court does not intend to deny the Motion

on the basis of the briefs, petitioners request that the motion

be set for oral argument.

Respectfully submitted,

Vanzetta Penn Durant

639 Martha Street

Montgom€Ty, Alabama 36194

Jack Greenberg

Lani Guinier

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N. Y. 10013

By:

-6-

Attorney for Petitioners