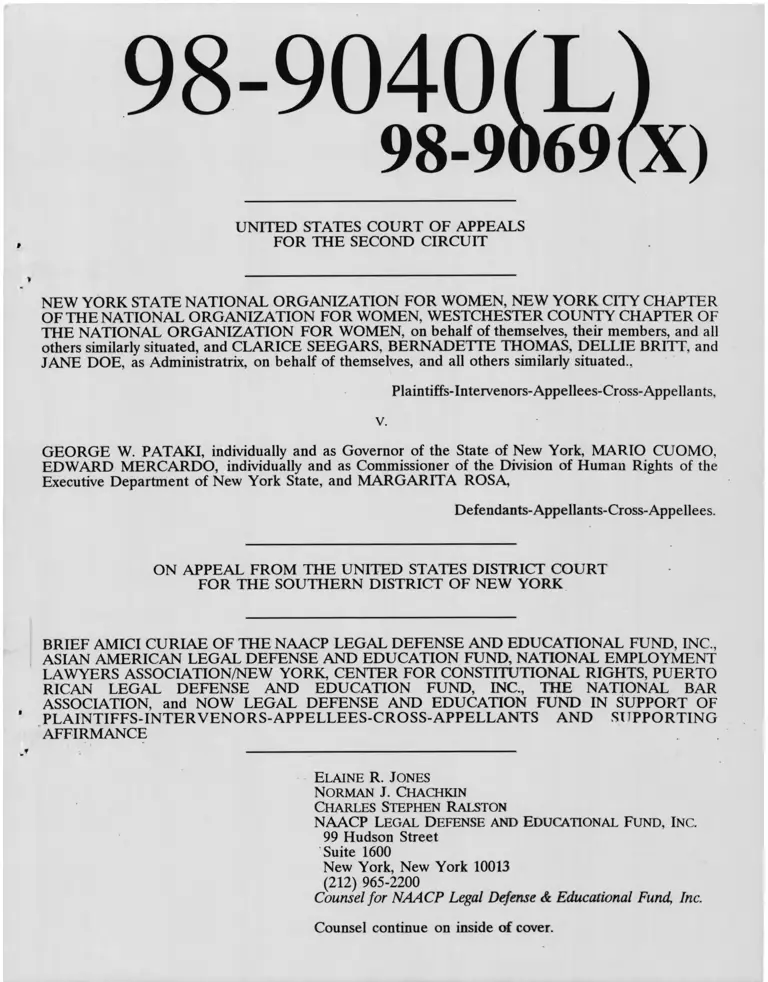

New York State National Organization for Women v. Pataki Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 30, 1999

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. New York State National Organization for Women v. Pataki Brief Amici Curiae, 1999. 7bacd176-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3298bbaf-be66-4907-a174-bed868f6800f/new-york-state-national-organization-for-women-v-pataki-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

X)

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

NEW YORK STATE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, NEW YORK CITY CHAPTER

OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, WESTCHESTER COUNTY CHAPTER OF

THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, on behalf of themselves, their members, and all

others similarly situated, and CLARICE SEEGARS, BERNADETTE THOMAS, DELLIE BRITT, and

JANE DOE, as Administratrix, on behalf of themselves, and all others similarly situated.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees-Cross-Appellants,

v.

GEORGE W. PATAKI, individually and as Governor of the State of New York, MARIO CUOMO,

EDWARD MERCARDO, individually and as Commissioner of the Division of Human Rights of the

Executive Department of New York State, and MARGARITA ROSA

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT

LAWYERS ASSOCIATION/NEW YORK, CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS, PUERTO

RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., THE NATIONAL BAR

ASSOCIATION, and NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND IN SUPPORT OF

PLAINTIFFS-INTER VENORS-APPELLEES-CROSS-APPELLANTS AND SI IPPORTING

AFFIRMANCE

Elaine R. Jones

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

Counsel continue on inside of cover.

Margaret Fung

Kenneth Kimerling

Asian American Legal Defense & Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Counsel for Asian American Legal Defense and Education

Fund

Nancy Chang

Center for Constitutional Rights

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, NY 10012

(212) 614-6420

Counsel for Center for Constitional Rights

Herbert Eisenberg

Davis & Eisenberg

377 Broadway, 9th Floor

New York, NY 10013

Counsel for National Employment Lawyers As sedation/New

York

Yolanda Wu

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund

395 Hudson Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10014

(212) 925-6635

Counsel for N O W Legal Defense and Education Fund

Juan Figueroa

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Counsel for Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

98-9040 (L); 98-9069 (X)

NEW YORK STATE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, NEW YORK

CITY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN,

WESTCHESTER COUNTY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR

WOMEN, on behalf of themselves, their members, and all others similarly situated, and

CLARICE SEEGARS, BERNADETTE THOMAS, DELLIE BRITT, and JANE DOE,

as Administratrix, on behalf of themselves, and all others similarly situated,

GEORGE W. PATAKI, individually and as Governor of the State of New York, MARIO

CUOMO, EDWARD MERCARDO, individually and as Commissioner of the Division of

Human Rights of the Executive Department of New York State, and MARGARITA

ROSA,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT PURSUANT TO 26.1 FRAP

All of the Amici are not-for-profit organizations. The corporate not-for-

profit amici have no parent corporations, stock, or stock holders.

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees-Cross-Appellants,

-against-

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees.

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

Counsel for Amici Curiae

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

98-9040 (L); 98-9069 (X)

NEW YORK STATE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, NEW YORK

CITY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN,

WESTCHESTER COUNTY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR

WOMEN, on behalf of themselves, their members, and all others similarly situated and

CLARICE SEEGARS, BERNADETTE THOMAS, DELLIE BRITT, and JANE DOE,

as Administratrix, on behalf of themselves, and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees-Cross-Appellants,

-against-

GEORGE W. PATAKI, individually and as Governor of the State of New York, MARIO

CUOMO, EDWARD MERCARDO, individually and as Commissioner of the Division of

Human Rights of the Executive Department of New York State, and MARGARITA

ROSA,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE PURSUANT TO FRAP 32(a)(7)

I submit this certificate pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate

Procedure 32(a)(7). The accompanying brief has been prepared using 14 pt.

Dutch Roman typeface. Relying on the word count of the word processing

system used to prepare the accompanying brief, I hereby represent that Amici

Curiae's brief contains 3,914 words, and is therefore within the 7,000-word

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT PURSUANT TO 26.1 FRAP

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE PURSUANT TO FRAP

32(a)(7)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................................................ ii

INTEREST OF THE AMICI C U R IA E ..................................................... 2

I. IN TRO D U CTIO N ................................................................................ 7

II. CONGRESS’S PURPOSE IN REQUIRING THE

EXHAUSTION OF STATE R E M E D IE S ....................................... 7

CONCLUSION .............................................................................................. 16

CERTIFICATE OF S E R V IC E .................................................................... 18

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Carey v. New York Gaslight Club, Inc., 598 F.2d 1253

(2nd Cir. 1979) ....................................................................................... 14

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980 )...................... 14

Reichman v. Bonsignore, Brignati & Mazzotta P.C., 818 F.2d 278

(2nd Cir. 1987) ....................................................................................... 14

Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85 (1 9 8 3 )........................ .............. 15

Statutes and Rules: Pages:

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ..............................................................................................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-8(b) .......................................................................................10

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-9 .............................................................. 8

Rule 29(a), Fed. R. App. Proc.......................................................................... 2

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .................................... 7-10, 12-15

Other Authorities: Pages:

110 Cong . Rec . 1635, 1636 (1964) ............................................................... 10

110 Cong . Rec. 2566 (1964 )........................................................................... 13

110 Cong . Rec. 7214 (1964 )........................................................................... 8

110 Cong. Rec. 7216 (1964 )........................................................................... 9

ii

Pages:

110 Cong. Rec. 10520 (1 9 6 4 )........................................................................ 12

110 Cong. Rec. 12595 (1964) ........................................................................ 11

110 Cong. Rec. 12724-25 (1964).......................... ......................................... 8

H. Rep. No. 1370, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. 1962 ......................................... 9. 13

H. Rep. 92-238, 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. (1971)................................................ 13

in

98-9040 (L); 98-9069 (X)

U N ITED STATES CO U RT OF APPEALS

FO R TH E SECOND CIRCU IT

NEW YORK STATE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, NEW

YORK CITY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR

WOMEN, WESTCHESTER COUNTY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL

ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, on behalf of themselves, their members,

and all others similarly situated, and CLARICE SEEGARS, BERNADETTE

THOMAS, DELLIE BRITT, and JANE DOE, as Administratrix, on behalf

of themselves, and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees-Cross-Appellants,

-against-

GEORGE W. PATAKI, individually and as Governor of the State of New

York, MARIO CUOMO, EDWARD MERCARDO, individually and as

Commissioner of the Division of Human Rights of the Executive Department

of New York State, and MARGARITA ROSA,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATION FUND. NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS

ASSOCIATION/NEW YORK, CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL

RIGHTS, PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION

FUND, INC., THE NATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION and NOW LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-

INTERVENORS-APPELLEES-CROSS-APPELLANTS AND SUPPORTING

AFFIRMANCE

IN TEREST OF TH E AM ICI CU RIA E

All parties have consented to the filing of this brief pursuant to Rule

29(a), Fed. R. App. Proc. The Amici Curiae are organizations involved in the

enforcement of civil rights in general and in the laws against employment

discrimination in particular. As such, they are concerned that persons

claiming unlawful discrimination have available to them the widest possible

range of remedies, including effective and meaningful administrative remedies

by state agencies such as the New York State Division on Human Rights.

1. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Inc.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

corporation organized under the laws of the State of New York. It was

formed to assist African-American citizens to secure their rights under the

Constitution and laws of the United States. For many years, Legal Defense

Fund attorneys have represented parties in litigation before the Supreme

Court of the United States and other federal courts in cases involving a variety

of race discrimination issues, including many cases involving Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. E.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976); Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

2

(986).

2. The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund.

The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund ("AALDEF"),

founded in 1974, is a nonprofit organization that protects the legal rights of

Asian Americans. AAEDEF has represented the Asian American community

in numerous cases and administrative proceedings including claims under the

New York State Human Rights Law. For many Asian Americans who are

discriminated against and unable to afford counsel, the filing of administrative

charges is their only means to remedy that discrimination. The delay in

processing and resolving complaints by the New York State Division of

Human Rights is a constant and continuing problem. For many Asian

Americans, these delays effectively deny them any relief for their claims of

discrimination.

3, The National Employment Lawyers Association

National Employment Lawyers Association/New York ("NELA/NY") is

the New York Chapter of the National Employment Lawyers Association

(NELA), a national bar association dedicated to the vindication of individual

employees’ basic rights in employment-related disputes. NELA is the nation’s

only professional organization comprised exclusively of lawyers who represent

3

individual employees, and its more than 3,500 member attorneys (in 49 state

chapters) are expert in issues of employment discrimination, employee

benefits, the rights of union members to fair representation, and other issues

arising from the employment relationship. NELA/NY has filed briefs in this

Court and the New York State Court of appeals in cases presenting important

questions of antidiscrimination law. The aim of this participation has been to

cast light not only on the subtleties of the legal issues presented but also on

the practical effects on the lives of working people that such legal rules

produce.

4. The Center for Constitutional Rights.

The Center for Constitutional Rights is a progressive law, education and

advocacy organization that is dedicated to the advancement of the rights

guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights. The Center, which grew out of the civil rights movement

in the Deep South in the 1960’s, has long been in the forefront of racial,

social, and economic justice litigation. The New York State Division of

Human Rights’ egregious delays in the processing and resolution of its

pending claims is a matter of tremendous concern to the Center because these

delays have prevented countless claimants from successfully prosecuting

4

m eritorious claims o f unlawful discrimination.

5. The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund. Inc.

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc..

("PRLDEF") is a national civil rights litigation organization founded in 1972.

Its mission is to further and protect the civil rights of Puerto Ricans and other

Latinos. PRLDEF has initiated hundreds of cases to combat discrimination

in significant areas such as education, housing, employment, voting and

language rights. Many of these cases were brought under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 as well as the New York State Human Rights Law.

It is of critical importance to PRLDEF that its constituency have the

opportunity to assert their discrimination claims and to be afforded a proper

and timely remedy.

6. NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund.

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund ("NOW LDEF") is a leading

national non-profit civil rights organization that performs a broad range of

legal and educational services in support of women’s efforts to eliminate sex-

based discrimination and secure equal rights. NOW LDEF was founded in

1970 by leaders of the National Organization for Women as a separate

organization. A major goal of NOW LDEF is the elimination of barriers that

5

deny women economic opportunities, such as employment discrimination. In

furtherance of that goal, NOW LDEF litigates cases to secure full

enforcement of laws such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

including Faragher v. City o f Boca Raton, 118 S. Ct. 2275 (1998); Bowman v.

Heller, 420 Mass. 517 (Ma. 1995), cert, denied, 516 U.S. 1032 (1995); and

Robinson v. Jacksonville Shipyards, Inc., 760 F. Supp. 1486 (M.D. Fla. 1991).

NOW LDEF filed amicus briefs in Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 118 S.

Ct. 2257 (1998); Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, 118 S. Ct. 998 (1998);

Harris v. Forklift Sys., Inc., 510 U.S. 17 (1993); and Landsgraf v. USI Film

Prods., 511 U.S. 244 (1944).

6

INTRODUCTION

The specific issue before the Court on the cross-appeals — whether the

district court erred in its rulings on qualified immunity for the defendant

public officials — will be discussed in detail by the parties, and amici will not

duplicate that discussion here. Rather, we wish to show that the right to state

administrative enforcement of an individual’s claim of employment

discrimination is indeed essential in light of the Congressional purpose in

requiring that claims under Title VII be first submitted to state agencies

before they may be pursued before the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission or filed in federal court. The considerations that led Congress

to enact this requirement lead to the conclusion that the systematic failure of

a state agency to provide meaningful remedies can and should be addressed

by the federal courts.

II.

CONGRESS’S PURPOSE IN REQUIRING THE

EXHAUSTION OF STATE REMEDIES

Congress had a number of concerns when it enacted Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 that led it to require that available state

administrative remedies be pursued before federal remedies could be resorted

to. First, questions of federalism led to the conclusion that existing state anti-

I.

7

discrimination laws and remedies should not be overridden.1 Thus, it was

made explicit that Title VII did not pre-empt existing state laws that were not

inconsistent with it,2 and that state administrative remedies could be resorted

to if a complainant so chose. Second, there was great concern that the new

EEOC would quickly be swamped with complaints and. given its national

scope, would not be able to handle all of the potential cases. Requiring initial

resort to existing state fair employment practices commissions could

significantly reduce the EEOC’s potential caseload.3 Third, it was hoped that

Senator Humphrey explained:

First, we were concerned that States and localities be afforded

every opportunity to resolve these difficult problems of racial

justice by means of their own agencies and instrumentalities. In

this respect it is perfectly proper to describe the substitute

package as a "States rights bill," and. I may say, a "States

responsibilities bill."

110 Cong. Rec. 12724-25 (1964).

242 U.S.C. § 2000e-9.

3The Clark-Case memorandum, submitted by the Senate managers of Title

VII, stated:

In point of fact, the task we are assigning to the Commission is so

immense, there can be little doubt that the Commission will from

sheer necessity avail itself to the fullest of the provisions of section

708(b) [provision in the original bill for deferral to effective state

agencies].

110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964).

8

states or localities without EEO laws would be encouraged to enact their own,

thus maximizing the remedies available to victims of discrimination.4

Of central concern was that, however Title VII was structured and

whatever the relationship between federal and state EEO laws, victims of

discrimination have in fact speedy and effective remedies against what was

rightly perceived to be a national problem of the utmost importance. Thus,

a central issue was whether the EEOC should have cease and desist powers

similar to those of the National Labor Relations Board and most state FEPCs,

and or whether the emphasis should be on conciliation and prompt resolution

by agreement, followed, if necessary, by litigation in federal court.5 The latter

position prevailed, with its proponents pointing to the experience of state

agencies of resolving most complaints through conciliation.6

4Deferral to effective state agencies "will induce the States to enact good

laws and enforce them . . . ." 110 Cong. Rec. 7216 (1964).

5See, H. Rep. 1370, pp 6-7 (1962) (Report of the House Committee on

Education and Labor on a predecessor bill, the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1962).

6It is ironic that Congressman Reid of New York, formerly the chair of the

New York State Commission for Civil Rights, cited that Commission’s record

from 1945 to 1963 as an model for the expeditious and effective resolution of

complaints. As of December 31, 1963, only 414 of the 8,373 EEO complaints

filed during that period remained open. Of those closed, 3,218 had resulted

in the adjustment of discriminatory practices or policies, mostly through

conciliation. It was through the effective enforcement of the law that would

9

The specific requirement that available state remedies be exhausted first

was introduced in the Senate as part of the Dirksen substitute to the House

bill. The House version of Title VII had provided that when the EEOC

determined that a particular state agency both had "effective power to

eliminate and prohibit discrimination" and was "effectively exercising such

power," then it would defer to such an agency as long as it both had and

effectively exercised that power.7 The Dirksen substitute added what is now

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) and (c), requiring that wherever a state or local FEPC

existed, recourse must be had to it for at least 60 days before the EEOC could

entertain a complaint under Title VII.

Although the Dirksen substitute was accepted by the Senate managers

of Title VII, grave concern was expressed over its possible deleterious impact

on the effective enforcement of the Act. Particularly striking with regard to

the issue in the present case were the comments of Senator Clark of

Pennsylvania, one of the floor managers:

After a good deal of careful thought, I have concluded that

the weakening changes [in the Dirksen substitute] are not so great

make "equality of opportunity and equal protection of the laws a present

reality—not keep it a pious principle; nor a future hope." 110 CONG. Rec

1635, 1636 (1964).

7This provision is now found in 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-10(b).

10

The changes I most deplore are, first, the subordination of

Federal power to the localities and the States in connection with

the enforcement of equal job opportunity . . . .

It is true that eventually, after he has applied for relief

under the State law or local ordinance, he can then turn to

proceedings before the Federal [EEOC]. But this might take a

considerable period of time, if local proceedings are strung out as

they could be by an unsympathetic administration. In many a case

I fear that the end result will be that justice delayed is justice

denied, and the unfortunate individual would never get the job to

which he was entitled because the employment situation could

well have changed in the meantime.

110 Cong. Rec. 12595 (1964).

Throughout the congressional debates concerns were expressed over the

efficacy and speed of the various administrative processes that were being

considered. Thus, Senator Dirksen, in explaining the substitute he was to

introduce, discussed the balance he hoped to achieve between the interest of

the states in enforcing their own EEO laws and the interest of individual

complainants:

. . . they all seek a workable and equitable civil rights bill but they

are mindful of the steady and deeper intrusion of the Federal

power in fields where the problem is essentially State and local in

character. . . . Surely we can develop language which will assure

the States on this point, assure individual complainants that they

will have fair and expeditious consideration of their grievances and

still retain sufficient authority in the Federal Commission to carry

as to make it im possible to achieve the objectives o f the title,

although they certainly make it more difficult.

11

110 Cong. Rec. 8193 (1964); emphasis added. Indeed, it was even

contemplated that in states that had FEPCs, the enforcement of the anti-

discrimination laws would be done primarily by the state agency, and that "title

VII will have but little effect" in those states.8

In sum, the speedy and effective enforcement of existing employment

discrimination laws by state agencies was uniformly seen as crucial to the

enforcement of Title VII. It was the clear intent of Congress that the ability

of complainants to have meaningful resolutions of complaints was to be both

independent of their right to bring an action under Title VII, and integral to

the attack on employment discrimination.

Through this coordinated administrative enforcement scheme, Congress

clearly hoped to avoid the inundation of the federal courts with EEO cases.

The House report on the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1962

Memorandum by Senator Carlson (D., Kan.), 110 Cong . Rec. 10520

(1964):

. . . Since Kansas already has a fair employment law barring

discrimination on account of race, color, religion, national origin

or ancestry, title VII would have little impact in the state. . . .

Thus, it is to be expected that discrimination in employment

would be handled by State officials under the State law and that

title VII will have but little effect within Kansas.

forward the purposes and objectives o f this title o f the bill.

12

emphasized the importance of the conciliation of complaints, pointing to the

record of state FEPCs. Thus, even though the 1962 Act would not give the

EEOC cease and desist powers, but would require an action in federal court,

the report assured that. "The committee does not feel that the procedure of

this -section will unduly burden the Federal courts," because the administrative

process would resolve most complaints. H. Rep. No. 1370, 87th Cong., 2d

Sess. 1962, pp. 6-7. Similarly, the 1964 Act was amended in the House to

make it certain that the Commission could not file an action in court without

first attempting to conciliate administratively. 110 CONG. Rec. 2566 (1964).

See id., (statement of,Rep. Roosevelt, in discussion of the right of the

complainant to bring an action, "We do not wish to flood the courts.").9

The argument advanced by the defendants here, that there has been no

deprivation because, ultimately, a victim of discrimination can file in federal

court even if the Division utterly fails to process her complaint, would subvert

Congress's intent to minimize the burden on the courts. As the Supreme

9Concern with overburdening the federal courts was one of the main

reasons that the House proposed to amend Title VII in 1972 to give the

EEOC cease-and-desist power. The proposal was ultimately rejected, but it

was hoped that giving the EEOC itself authority to bring lawsuits if

conciliation failed would result in more complaints being settled

administratively and few coming to the courts. H. Rep. 92-238, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess. pp. 8-11 (1971).

13

Court noted in New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 66, n.6

(1980) in holding that attorneys’ fees were awardable for work done in state

administrative proceedings that were a prerequisite to a Title VII action:

The existence of an incentive to get into federal court, such as the

availability of a fee award, would ensure that almost all Title VII

complainants would abandon state proceedings as soon as

possible. This, however, would undermine Congress’ intent to

encourage full use of state remedies.

See also, Carey v. New York Gaslight Club, Inc., 598 F.2d 1253, 1257 (2nd Cir.

1979) ("Thus, state human rights agencies play an important role in the

enforcement process of Title VII, since they afford a chance to resolve a

discrimination complaint in accordance with federal policy before such a

complaint reaches the federal courts"); Reichman v. Bonsignore, Brignati &

Mazzotta P.C., 818 F.2d 278, 283 (2nd Cir. 1987) (following Carey in an ADEA

case since Congress intended that plaintiffs utilize state administrative

proceedings "before commencing an action in federal court").

Not only would the position of the defendants — which boils down to

nothing less than "it doesn’t matter that New York’s system is worthless, you

can always go to the EEOC" — cast an undue burden on the federal courts,

it would undermine the enforcement scheme as a whole. Thus, the Supreme

Court rejected arguments that the federal Employee Retirement Income

14

Security Act of 1974 pre-empted the New York Human Rights Law because

such a result would "impair Title VII to the extent that the Human rights law

provides a means of enforcing of Title VII’s commands." Shaw v. Delta Air

Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85, 102 (1983). Since the EEOC would not be able to

refer a claim that a benefit plan was discriminatory to the State Division:

. . . those claims that would have been settled at the state level

would require the EEOC’s attention. . . . The EEOC’s options

for coping with this added burden, barring discoveries of reserves

in the agency budget, would be to devote less time to each

individual case or to accept longer delays in handling cases. The

inevitable result of complete pre-emption, in short, would be less

effective enforcement of Title VII.

463 U.S. at 102, n. 23.

Most important, as has been shown to be the case here, without the

effective administrative process that Congress intended, many victims of

discrimination would be left without any practical remedy whatsoever because

they lack the resources to bring an action in federal court. Amici can attest

to their experiences in counselling many individuals with potentially valid EEO

complaints who have been unable to obtain any consideration of their claims,

let alone one that is "fair and expeditious," because of the failure of

administrative agencies, including the New York Division on Human Rights,

to provide any meaningful remedy and because of the prohibitive cost of

15

bringing and maintaining a court action.10 The present case presents the

possibility for correcting the nonfeasance of the Division, and thereby, in the

words of Rep. Ogden Reid, making "equality of opportunity and equal

protection of the laws a present reality" rather than "a pious principle; [or] a

future hope."11

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the district court on the issue

of the importance of the right to a speedy and effective state remedy was

correct, and should not be overruled.

1()The number of requests for assistance received by amici far exceeds their

resources available to take on cases. A number of amici, in fact, are able to

provide representation only in class actions, and handle few if any individual

EEO cases at the trial court level.

11 See n. 6, supra.

16

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc.

Nancy Chang

Center for Constitutional

Rights

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, NY 10012

(212) 614-6420

Counsel for Center for

Constitutional Rights

Yolanda Wu

NOW Legal Defense and

Education Fund

395 Hudson Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10014

(212) 925-6635

Counsel for NOW Legal Defense

and Education Fund

Margaret Fung

Kenneth Kimerling

Asian American Legal

Defense & Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Counsel for Asian American Legal

Defense and Education Fund

Herbert Eisenberg

Davis & Eisenberg

377 Broadway, 9th Floor

New York, NY 10013

Counsel for National Employment

Lawyers Association/New York

Juan Figueroa

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Counsel for Puerto Rican Legal

Defense and Education Fund

17

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing BRIEF AMICI CURIAE,

have been served by depositing same in the United States mail, first class

postage prepaid, on this 30th of July, 1999, addressed to the following:

Eliot Spitzer

Attorney General

Adam L. Aronson

Assistant Attorney General

Robert A. Forte

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney

General of the State of New

York

120 Broadway

New York, NY 10271

David Raff, Esq.

Robert L. Becker, Esq.

Raff & Becker, LLP

59 John Street, 6th Floor

New York, NY 10038

18