Docutel/Olivetti Corporation v. Finkel Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Docutel/Olivetti Corporation v. Finkel Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1987. e60b07fb-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/32ed22be-bf63-4349-a6b5-724b4ea024d9/docutelolivetti-corporation-v-finkel-respondents-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

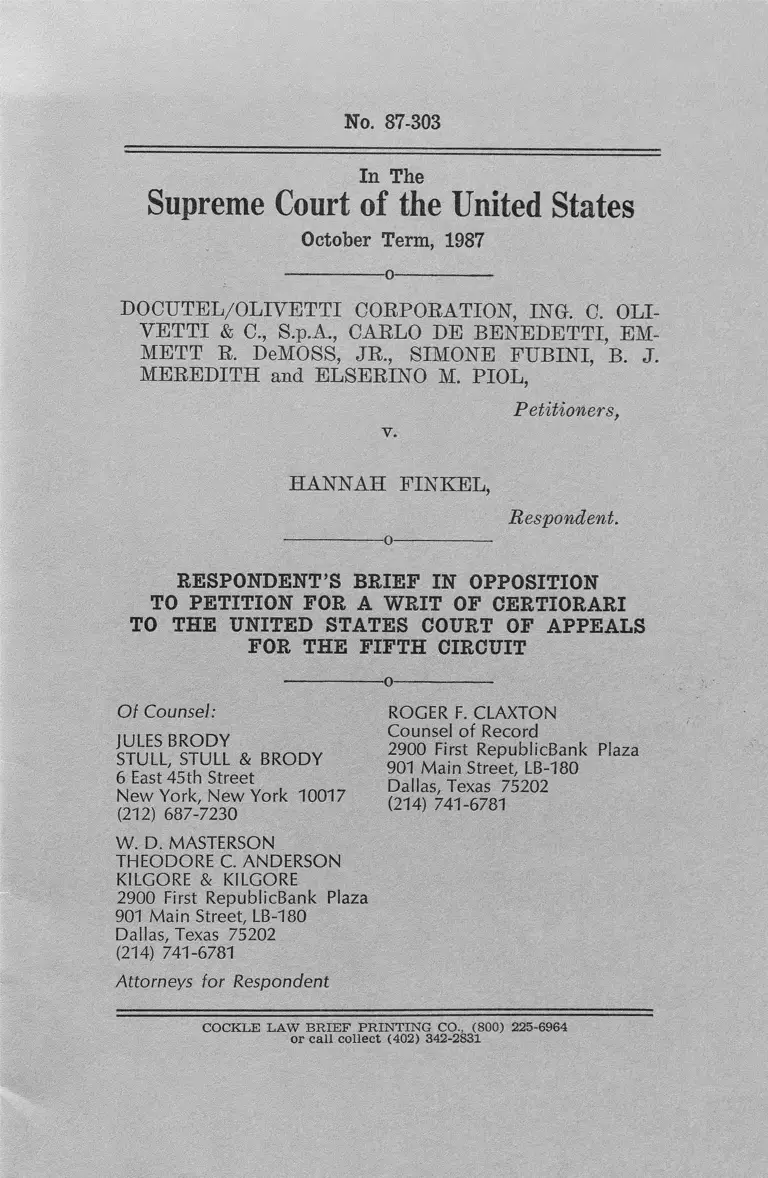

No. 87-303

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1987

----------------o---------------

DOCUTEL/OLIVETTI CORPORATION, ING. C. OLI

VETTI & C., S.p.A., CARLO DE BENEDETTI, EM

METT R. DeMOSS, JR., SIMONE FUBINI, B. J.

MEREDITH and ELSERINO M. PIOL,

Petitioners,

v.

HANNAH FINKEL,

Respondent.

----- — -— o------ ------ -—■

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

TO PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

----------------o----------------

O f Counsel:

JULES BRODY

STULL, STULL & BRODY

6 East 45th Street

New York, New York 10017

(212) 687-7230

W . D. MASTERSON

THEODORE C. ANDERSON

KILGORE & KILGORE

2900 First RepublicBank Plaza

901 Main Street, LB-180

Dallas, Texas 75202

(214) 741-6781

Attorneys fo r Respondent

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

or call collect (402) 342-2831

ROGER F. CLAXTON

Counsel of Record

2900 First RepublicBank Plaza

901 Main Street, LB-180

Dallas, Texas 75202

(214) 741-6781

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is a plaintiff class of investors which purchases se

curities in an established market at a price artificially

inflated by a scheme to defraud or course of business that

operates as a fraud on investors, entitled to a presump

tion of reliance in order to recover for securities fraud

under Section 10(b) of the 1934 Act and Rule 10b-5(l)

and (3) thereunder?

11

QUESTION PRESENTED ........................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................... ill

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ..................................... 2

STATEMENT OF F A C T S............................................. 3

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION ........... 5

T. RESPONDENTS WERE ENTITLED TO A

REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION OF RE

LIANCE UNDER THE FRAUD ON THE

MARKET DOCTRINE ................................... 5

II. THE FRAUD ON THE MARKET DOC

TRINE FURTHERS THE CLEAR IN

TENT OF CONGRESS................................... 8

III. THIS COURT HAS PREVIOUSLY CON

SIDERED THE INDIVIDUAL RELIANCE

ISSUE IN THE SECURITIES FRAUD

CONTEXT ........................................................ 16

IV. PETITIONERS DO NOT HAVE STAND

ING TO ASSERT THE CONFLICT WITH

IN THE CIRCUITS AS A REASON FOR

THIS COURT TO GRANT CERTIORARI... 18

V. THIS CASE DIFFERS FROM BASIC VS.

LEVINSON WHICH IS CURRENTLY BE

FORE THIS COURT ...... 20

CONCLUSION ................................................................. 22

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I l l

Cases

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Affiliated Ute Citizens v. United States,

406 U.S. 128 (1972) ....................................... 16,17,18

Bateman. Eichler, Hill Richards, Inc. v.

Berner, 472 U.S. 299 (1985) ............................... 12

Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891 (9th Cir.

1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 816 (1976) ...6,10,11,19

Blue Chip Stamps v. Manor Drug Stores,

421 U.S. 723 (1975) ............................................... 10

Chemetron Corp. v. Business Funds. Inc.,

718 F.2d 725 (5th Cir. 1983) ........ ....................... 16

Dorfman v. First Boston Corp., 62 F.R.D.

466 (E.D.Pa. 1974) ............. ................................. 18

Dupuy v. Dupmj, 551 F.2d 1005 (5th Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 911 (1977) ............... 6

Finkel v. Do cut el/ Olivetti, 817 F.2d 356 (5th

Cir. 1987) ............................................................ 6,7,8

Green v. Occidental, 541 F.2d 1335 (9th Cir. 1976) 15

Harris v. Union Electric Co., 787 F.2d 355 (8th

Cir. 1986), cert, denied, No. 85-2036 (Oct.

6, 1986) ................................................................... 6

Herman do MacLean v. Huddleston, 459 U.S.

375 (1983) .............................................................. 15

In re LTV Securities Liliaation, 88 F.R.D. 134

(N.D. Texas 1980) .... 1.....................................7,13,15

Kardon v. National Gypsum, 69 F.Supp. 512

(E.D.Penn. 1946) .................................................. 9

Levinson v. Basic, 786 F.2d 741 (6th Cir. 1986),

cert, granted, 107 S. Ct. 1284 (Feb. 23, 1987)

(No. 86-279) ...............................................6,12,20,21

IV

Lipton v. Documation, Inc., 734 F.2d 740 (11th

Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1132 (1985) 6,10,19

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375

(1970) .............................................. ......................16,17

Pansirer v. Wolf, 663 F.2d 365 (2d Cir. 1981),

vacated as moot after cert, granted, 459

U.S. 1027 (1982) .................................................. 6

Peil v. Speiser, 806 F.2d 1154 (3d Cir. 1986) .......6,19

T.J. Raney d Sons, Inc. v. Fort Cobb, Okla

homa Irrigation Fuel Authority, 717 F.2d

1330 (10th Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 465 U.S.

1026 (1984) ............................................................ 6

Rifhin v. Crow, 574 F.2d 256 (5th Cir. 1978) ....... 18

Ross v. A.H. Robins Co., 607 F.2d 545 (2d Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 946 (1980) ...........6,16

Schlanger v. Four-Phase Systems, Inc., 555

F.Supp. 535 (S.D.N.Y. 1982) .............................. 11

SEC v. Texas Gulf Sulphur Co., 401 F.2d 833

(2d Cir. 1968) (en banc), cert, denied, 394

U.S. 976 (1969) .................................................... 10

Shores v. Sklar, 647 F.2d 462 (5th Cir. 1981)

(en banc), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1102 (1983) ...2,3,6

Valley Forge College v. Americans United,

454 U.S. 464 (1982) ............................................. 19

Vervaecke v. Chiles, Heider & Co., 578 F.2d

713 (8th Cir. 1978) ............................................... 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

S tatutes and R ules

Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 7Sj(b) ...2, 8, 9,10,15,16,17

Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78 (n) (1976) ................. 17

Section 18(a) of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78(r) ............ ............. 15, 16

Section 20 of the Securities Exchange Act of

1934, 15 U.S.C. §78 (t) ......................................... 2

Securities and Exchange Commission Rule

10b-5, 17 C.F.R. § 240.1013-5 ..................... ....passim

Rule 12(b)(6) Fed. F. Civ. P. ................................ 20

Rule 23(a) and (b) (3) Fed. R. Civ. P . .............2,12, 20

A rticles

Black, Fraud on the Market: A Criticism of

Dispensing with Reliance Requirements in

Certain Open Market Transactions, 62

X.C.L. Rev. 435 (1984) ............................................ 9

A. Bromberg & L. Lowenfels, 1 Securities

Fraud and Commodities Fraud, 2.2(110) at

2:13 (1986) ....................................................... 10

Easterbrook and Fischel, Mandatory Disclos

ure and the Protection of Investors, 70 Ya.

L.Rev. 669 (1984) .................................................. 12

Note, The Efficient Capital Market Hypoth

esis, Economic Theory and the Regulation

of the Securities Industry, 29 Stan. L. Rev.

1031 (1977) ...................................... 7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

VI

Fama, Efficient Capital Markets: A Review

of Theory and Empirical Work, 25 J.Fin.

383 (1970) .............................................................. 7

Fiscliel, TJse of Modern Finance Theory in Se

curities Fraud Cases Involving Actively

Traded Securities, 38 Bus.L. 1 (1982) ...............7,14

Note, Fraud on the Market: An Emerging

Theory of Recovery Under SEC Rule 10b-5,

50 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 627 (1982) ...................... 9

Note, Fraud-on-the-Market Theory, 95 Harv.

L.Rev. 1143 (1982) .............................................7, 9,13

H. Kripke, The SEC and Corporate Disclos

ure at 14 (1979) .................................................. 7

Rapp, Rule 10b-5 and “ Fraud-on-the-Market”

—Heavy Seas Meet Tranquil Shores, 39

Wash. & Lee L.Rev. 861 (1982) .......................... 9

M iscellaneous

Testimony of Thomas G. Corcoran, Hearing

on HR 7852 and HR 8720 before the House

Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com

merce, 73d Congress, 2d Sess., 115 (1934) ....... 10

Wall Street Journal, April 2, 1984 ........................5,15

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

No. 87-303

---------------- o— _— .—----

In The

Supreme Court ©f the United States

October Term, 1987

—------------ o----------------

DOCUTEL/OLIVETTI CORPORATION, ING. C. OLI

VETTI & C., S.p.A., CARLO DE BENEDETTI, EM

METT R. DeMOSS, JR., SIMONE FUBINI, B. J.

MEREDITH and ELSERINQ M. PIOL,

v.

Petitioners,

HANNAH FINKEL,

Respondent.

■o-------------

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

TO PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

------------— o---------------

Respondent Hannah Finkel respectfully requests that

the Court deny the Petition for Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (“ Petition” )

submitted by Docutel/Olivetti Corporation (“ Docutel” )

and several individuals (collectively the “ Defendants” ) to

review a final judgment of the United States Court of

1

2

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The judgment appealed

from (i) reversed the District Court’s Order granting

Defendants/Petitioners’ Motion to Dismiss dismissing

Plaintiff’s claims under 10b-5(l) and (3) of the Securities

and Exchange Commission, and (ii) affirmed the District

Court’s Order granting Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

Plaintiff’s claims under Rule 10b-5(2) of the Securities

and Exchange Commission.

--------------------o— -—■— -—-— ••

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Course of Proceedings and Disposition Below

Plaintiff’s complaint arises under Sections 10(b) and

20 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C.

§ 78(a), et seq. (the “ Exchange Act” ) and Securities and

Exchange Rule 10b-5 promulgated thereunder. Plaintiff

brought this action as a class action pursuant to Rules 23

(a) and (b)(3) F.R.C.P.

Defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss. The Motion to

Dismiss alleged that the Complaint is fatally defective for

failure to allege individual reliance upon misrepresenta

tions of Defendants.

Discovery and class certification were deferred pur

suant to agreed orders pending a ruling by the District

Court on Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss.

On August 20, 1986, the District Court dismissed the

Plaintiff’s Complaint without prejudice based upon an in

terpretation of Shores vs. Sklar, 647 F.2d 462 (5th Cir.

1981) (en banc), cert, denied, 459 TT.S. 1102 (1983), to the

3

effect that a plaintiff in the Fifth Circuit who purchases

securities in an established market cannot rely upon the

integrity of the market pursuant to the fraud on the market

doctrine, but must plead and prove individual reliance upon

specific misrepresentations.

On May 27, 1986, the Fifth Circuit reversed and re

manded, holding that to the extent that Plaintiff’s Com

plaint alleged a scheme to defraud or course of business

operating as a fraud, Plaintiff had properly pled causes

of action under 10b-5(l) and (3). Plaintiff did not have

to plead specific reliance upon alleged misrepresentations.

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the District Court’s dismissal

of Plaintiff’s Complaint with respect to claims under 10b-

5(2), holding that under Shores, any fraud on the market

claim under section (2) is barred by Plaintiff’s failure to

allege that she read and relied on any of the documents

now claimed to have misrepresented the financial condi

tion of Docutel.

On August 29, 1987, the District Court stayed this

action pending this Court’s ruling on Petitioner’s petition

for a writ of certiorari.

--------------- o--------------- .

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Defendant Docutel/Olivetti Corporation (“ Docutel” )

is a Delaware corporation with executive offices in Irving,

Texas. On October 1, 1983, Docutel had issued and out

standing 6,800,000 shares of common stock owned by more

than 3,200 shareholders. Docutel’s shares were traded in

4

the over-the-counter market. Defendant Ing. C. Olivetti

and C., S.p.A. (“ Olivetti” ) is an Italian corporation with

its executive offices located in Italy. Olivetti acquired

practical control of Docutel by means of a merger between

a subsidiary of Olivetti and Docutel, and the issuance of

a warrant by Docutel to the Olivetti subsidiary. Defen

dants B. J. Meredith and Emmett R. DeMoss were, re

spectively, the chief executive officer and executive vice

president and chief financial officer of Docutel.

Defendants Carlo DeBenedetti and Simone Fubini

were respectively the chief executive officer and chief

operating officer of Olivetti. Defendant Elserino M. Piol

was a representative of Olivetti who acted as a director

of Docutel.

On December 5, 1983, Plaintiff purchased 300 shares

of Docutel on the public market at $14-5/8 per share, for

a total price of $4,474.75.

Plaintiff alleged that the quarterly earnings of Docutel

reported through 1983 were substantially overstated, and

losses were understated, by reason of the failure of Docu

tel, and Olivetti as its controlling shareholder, and the re

spective officers, to charge off worthless inventories ac

quired from Olivetti and its subsidiary. Docutel was made

to buy inventory from Olivetti which was unsalable, giving-

rise to the write-downs complained of by Plaintiff in this

action.

Plaintiff relied upon the integrity of the public market

for Docutel shares in making her purchases and thereby

incurred losses by paying the artificially inflated public

market prices resulting from the fraudulently overstated

earnings.

5

Oil February 16, 1984, Docutel announced a projected

net loss for tbe year ended December 31, 1983, in the

amount of $14,000,000. On April 2, 1984, the Wall Street

Journal reported that Docutel said its previously projected

net loss for 1983 of $14,000,000 would be significantly

wider. In its 10-K for 1983 Docutel reported an after tax

loss of $18,263,000 for 1983. The loss included $10,900,000

of inventory write-downs, approximately $10,100,000 of

which was recorded in the fourth quarter. Significantly,

Docutel made the following admission in its 1983 Form

10-K:

In 1983, the Company’s record keeping procedures and

accounting staff were strained due to the significant

growth in transaction volume resulting from the

merger with Olivetti Corporation, attrition of per

sonnel, and the transfer in the second half of 1983

of OPD accounting function from Tarrytown, New

York, to the Company’s headquarters in Irving, Texas.

Docutel’s stock plummeted from a high of $38-7/8 in

1983 to a closing bid price on April 6, 1984 of $7-1/4, caus

ing public investors to take large losses.

--------------- o----------------

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION

I. RESPONDENTS WERE ENTITLED TO A REBUT

TABLE PRESUMPTION OF RELIANCE UNDER

THE FRAUD ON THE MARKET THEORY

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in this case cor

rectly held that since Respondent had alleged a scheme to

defraud or course of business operating as a fraud in viola

6

tion of Rule 10b-5(l) and (3), Respondent was entitled to a

rebuttable presumption of reliance upon proof of material

ity of the alleged conduct.

Reliance is generally a requirement to a claim stated

under Rule 10b-5. Proof of reliance establishes that the

damaged party was induced to act by the defendant’s con

duct ; it defines the causal link between defendant’s miscon

duct and the plaintiff’s decision to buy or sell securities.

Dupuy v. Dupuy, 551 F.2d 1005, at 1016 (5th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 911 (1977); FinJcel v. Docutel/Oli-

vetti, 817 F.2d 356 at 359 (5th Cir. 1987). The fraud on

the market doctrine, adopted by every Circuit Court of

Appeals to consider it1 permits a plaintiff to rely upon

the integrity of an established market to set a price

untainted by fraud, without pleading individual reli

ance upon specific misrepresentations. Most courts have

held that a plaintiff is entitled only to a presumption of re

liance, which may be rebutted by defendants. In this case,

the Court of Appeals held that Defendants may rebut the

presumption of reliance in two ways: 1) by showing that

the nondisclosures did not affect the market price for the

^ e e Pei I v. Speiser, 806 F.2d 1154 (3d Cir. 1986); Levinson

v. Basic, 786 F.2d 741 (6th Cir. 1986), cert, granted, 107 S. Ct.

1284 (Feb. 23, 1987); Harris v. Union Electric Co., 787 F.2d 355

(8th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, No. 85-2036 (Oct. 6, 1986); Upton

v. Documentation, Inc., 734 F.2d 740 (11th Cir. 1984), cert, de

nied, 469 U.S. 1132 (1985); T.J. Raney & Sons, Inc. v. Fort Cobb,

Oklahoma Irrigation Fuel Authority, 717 F.2d 1330 (10th Cir.

1983), cert, denied, 465 U.S. 1026 (1984); Shores v. Sklar, 647

F,2d 462 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1102 (1983);

Panzirer v. W o lf, 663 F.2d 365 (2d Cir. 1981), vacated as moot

after cert, granted, 459 U.S. 1027 (1982); Ross v. A.H. Robins

Co., 607 F.2d 545, 553 (2d Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 946

(1980); Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891 (9th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 429 U.S. 816 (1976).

security; or 2) that plaintiff would have purchased the

stock at the same price even if she had known the informa

tion that was not disclosed. Docutel, 817 F.2d at 364-365.

The fraud on the market doctrine is premised upon the

theory that the market price for a security, in an open and

developed market, accurately reflects the value of that se

curity if all relevant information has been disclosed in the

marketplace.2 When one fails to disclose or misrepresents

material information about a security, the market’s effic

ient pricing mechanism is skewed and the price of the secur

ity is distorted. Docutel, 817 F.2d at 360. The fraud on the

market doctrine recognizes the fact that most investors do

not carefully examine all available information about a

security because there is too much, and much of it is too

technical.3 Instead the typical investor relies upon the in-

7-

2This is a conclusion of the efficient market theory. The

theory states that the market price reflects all representations

concerning the stock. The market price of securities is a func

tion of the information the market possesses, both positive and

negative, assuming all information is disclosed. In re LTV Se

curities Litigation, 88 F.R.D. 134, 144 (N.D.Texas 1980). See LTV

for citations to the economic theories and leading works which

support the doctrine. See also, Fischel, Use of Modern Finance

Theory in Securities Fraud Cases Involving Actively Traded Se

curities, 38 Bus.L 1 (1982); Fama, Efficient Capital Markets: A

Review of Theory and Empirical W ork, 25 j.Fin. 383 (1970);

Note, Fraud-on-the-Market Theory, 95 Harv.L.Rev. 1143 (1982);

Note, The Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis, Economic Theory

and the Regulation of the Securities Industry, 29 Stan. L. Rev.

1031 (1977).

35ee, Fischel, 38 Bus. Law, 1, 2 -5 ; Docutel, 817 F.2d at 360

n. 9 ("[R jecent scholarship suggests that the dissenters' vision of

individual investors reading and relying upon information re

quired to be disclosed in registration statements and the like is

suspect. Most SEC disclosure documents not only go unread by

their intended recipients but in fact 'can only be used effectively

by market professionals.'") (quoting Note, The Fraud-on-the-

Market Theory, 95 Harv.L.Rev. 1143, 1159 (1982) and H. Kripke,

The SEC and Corporate Disclosure at 14 (1979)).

8

tegrity of the market to be free from deception and to value

accurately a security in light of all the material information

about the security. The market becomes the theoretical

agent of the investor. Consequently, a purchaser or seller

who relies on the market to value the security accurately

suffers damages if the market does not have all the infor

mation or if some of the information is false.

The ability of an investor to rely upon the market price

for securities as reflecting an individual issuer’s prospects

is critical to liquidity in the nation’s capital markets. Most

investors rely upon the integrity of the public market when

they invest. The typical investor has insufficient time to

review all of the data available with respect to individual

securities considered for purchase. Thus, there are im

portant economic bases, as well as legal bases, for the fraud

on the market doctrine. It is for these reasons that the

fraud on the market doctrine has been adopted in every cir

cuit to consider it. See note 1 above.

II. THE FRAUD ON THE MARKET DOCTRINE FUR

THERS THE CLEAR INTENT OF CONGRESS.

Petitioners wrongly contend that in adopting Section

10(b) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C.

§78j(b), Congress intended to incorporate the basic ele

ments of common law fraud. Petitioners mischaracterize

Congress’ intent in an attempt to overturn the fraud on the

market doctrine against the great weight of judicial, scho

lastic and administrative authority that supports it.4 The

4See supra note 1 and accompanying text; Docutel, 817 F.2d

at 361 (“ The Securities and Exchange Commission accepts the

efficient market hypothesis, which underlies the fraud on the

(Continued on next page)

9

creation of the many new rules contained in the ’33 and ’34

Acts constitutes Congressional recognition of the inability

of state common law principles to deal with securities

fraud. Nowhere in the text of Section 10(b), or Rule 10b-5

promulgated thereunder, are the alleged elements of com

mon law fraud required.5 Section 10(b) was deliberately

couched in broad terms and intended to be a catch-all to

prevent manipulative devices that theretofore ran ram

pant.6

(Continued from previous page)

market theory.") (footnote omitted); see also Black, Fraud on

the Market: A Criticism of Dispensing w ith Reliance Require

ments in Certain Open Market Transactions, 62 N.C.L.Rev. 435

(1984); Rapp, Rule 10b-5 and "Fraud-on-the-Market"— Heavy

Seas Meet Tranquil Shores, 39 Wash.& Lee L.Rev. 861 (1982);

Note, Fraud on the Market: An Emerging Theory of Recovery

Under SEC Rule 10b-5, 50 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 627 (1982); Note,

Fraud-on-the-Market Theory, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 1143 (1982).

5At the outset, Petitioners cite Kardon v. National Gypsum,

69 F.Supp. 512 (E.D.Penn. 1946) for the proposition that the

cause of action under Rule 10b-5 has always incorporated the

basic elements of the common law deceit action. This is simply

not correct. In National Gypsum the plaintiffs made claims

based upon both common law fraud and Rule 10b-5. The court

held that plaintiff's allegations sustained both claims. Nowhere

did the court require the allegations of a common law fraud

claim as a prerequisite to a claim under Rule 10b~5. The court

simply held that the allegations as they were made sufficed to

uphold claims under both 10b-5 and common law fraud.

6ln summing up Section 9(c) before the House Committee,

which without significant alteration became Section 10(b) of

the Act, one of the principal drafters said the following:

"Subsection (c) says, 'Thou shalt not devise any other cun

ning devices.' . . . O f course subsection . . . (c) is a catch

all clause to prevent manipulative devices!.] I do not

think there is any objection to that kind of a clause. The

Commission should have authority to deal with new manip

ulative devices."

(Continued on next page)

10

The fraud on the market theory actually embraces

Congress’ intent. The fraud on the market theory adheres

to legislative intent by fostering public confidence in the

markets, by deterring fraud and by promoting judical ef

ficiency through the class action vehicle.

Restoring investor confidence in the securities mar

kets was a primary reason for adopting the federal securi

ties laws. See 1 A. Bromberg & L. Lowenfels, Securities

Fraud and Commodities Fraud, Section 2.2(110) at 2:13

(1986) (“ [Statutory antifraud provisions] were part of the

initial New Deal response to the financial debacle of the

1920’s, investigations of which revealed widespread fraud,

manipulation and victimization of public investors by con

cealment of relevant information” ). With respect to Sec

tion 10 and Rule 10b-5, courts have held that “ [t]he

statute and rule are designed to foster an expectation that

securities markets are free from fraud—an expectation on

which purchasers should be able to rely.” Blackie v. Bar

rack, 524 F.2d at 907; see also, Lipton v. Documation,

734 F.2d at 748. The ability of an investor to rely upon

the honesty and integrity of the market is critical to liquidi

ty in the nation’s capital markets. As one court has noted,

“ it is hard to imagine that there ever is a buyer or seller

who does not rely on market integrity. Who would know

continued from previous page)

Testimony of Thomas G. Corcoran, Hearing on HR 7852 and

HR 8720 before the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign

Commerce, 73d Congress, 2d Sess., 115 (1934). The courts have

quoted this comment in giving broad interpretation to Section

10(b). See, e.g., Blue Chip Stamps v. Manor Drug Stores, 421

U.S. 723, 766 (1975) (dissent of Blackmun J.); SEC v. Texas Gulf

Sulphur Co., 401 F.2d 833, 859 (2d Cir. 1968) (en banc), cert,

denied, 394 U.S. 976 (1969).

11

ingly roll the dice in a crooked crap game?” Schlanger

v. Four-Phase Systems, Inc., 555 F.Supp. 535, 538 (S.D.

N.Y. 1982).

The fraud on the market doctrine recognizes the fact

that the legislative policy designed to foster investor ex

pectations of honesty in the securities markets has become

reality. Investors rely upon the integrity of the market

when they invest. They purchase upon the assumption that

the market price is free from any unsuspected manipula

tion that could inflate the market price. The fraud on the

market doctrine simply furthers the goals of the securities

laws by protecting those that rely on the integrity of the

market when they invest. Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d at

907. Such investors may recover from corporate wrong

doers without proving individual reliance on specific mis

representations, but by showing that they relied upon the

integrity of the market when they purchased the security

—an expectation on which purchasers should be able to

rely. Requiring direct proof from each purchaser that he

relied on a particular representation when purchasing

would defeat recovery by those whose reliance was indirect

or on the integrity of the public market place. The securi

ties laws would operate to protect only those investors

with enough time and sophistication to digest all informa

tion disseminated into the public market, despite the fact

that all investors who rely on the honesty of the market

suffer the damage of purchasing a security at a price in

flated by material misrepresentations. To leave such open

market purchasers unprotected is not consistent with the

policies under the federal securities laws. Investors should

and do rely upon the integrity of the public market when

they invest.

12

To the extent that private securities fraud actions may

be prosecuted more efficiently by adoption of the fraud

on the market theory, the enforcement of the securities

laws, and the underlying goal of honest markets, are fur

thered. Brief for the Securities and Exchange Commission

as Amicus Curiae at 26, Basic v. Levinson, No. 86-279

(U.S. filed April 1987). There is no doubt that implied pri

vate actions under 10b-5 effectively enforce the securities

laws. Id. (The Securities and Exchange Commission noted

that the Supreme Court has “ repeatedly . . . emphasized

. . . that implied private actions [under Rule 10b-5] pro

vide ‘ a most effective weapon in the enforcement’ of the

securities laws and are ‘ a necessary supplement to Com

mission action.’ ” (quoting Bateman Eichler, Rill Rich

ards, Inc. v. Berner, 472 U.S. 299, 310 (1985)).

Federal securities laws were also adopted for the pur

pose of efficiency in enforcing in one case all claims that

arise out of a single transaction. As commentators have

written,

The securities laws create nationwide service of pro

cess and have a liberal venue rule that permits litiga

tion to consolidate all defendants and all claims in a

single forum. The class action device created by Rule

23 of the Rules of Civil Procedure makes it easy to

bring all plaintiffs together.

Easterbrook and Fisehel, Mandatory Disclosure and the

Protection of Investors, 70 Ya.L.Rev. 669, at 680 (1984).

The fraud on the market doctrine has special and obvious

appeal in class actions because the need to prove a per

sonalized reliance by each class member is avoided. The

question of reliance usually arises in the context of whether

13

or not to certify a class.7 If a plaintiff in a securities

fraud action must plead and prove individual reliance, then

class certification is probably improper, because issues of

individual reliance will predominate. If the class action

procedural device can no longer be used to handle major

securities cases, then defendants will gain some measure

of relief because not all defrauded investors will sue. As

one commentator pointed out:

The only person whose behavior is likely to be changed

are would-be defrauders, because the fraud-on-the-

market theory, by eliminating issues of individual re

liance, facilitates class action recovery of claims that

would otherwise be too small to be litigated individual

ly. And here, possibly, lies an unstated rationale for

the fraud-on-the-market decisions, almost all of which

involved class actions: only if courts allow class ac

tions to proceed will under-inclusive recoveries and

hence a failure to deter fraud at its inception be

avoided.

(footnote omitted) Note, Fraud-on-the-Market Theory, 95

Harv.L.Rev. 1143, at 1159 (1982). Moreover, there will no

doubt be many separate suits filed by investors who are

in a position to plead and prove individual reliance. The

cost to the judicial system in litigating each of such suits

separately will likely be unacceptable.

Petitioners argue that the fraud on the market doctrine

is inconsistent with the full disclosure policy of the se

7For example, in In re LTV Securities Litigation, 88 F.R.D.

134 (N.D.Tex. 1980), the question of whether to apply the fraud

on the market doctrine arose in the context of a motion to cer

tify a class of more than 100,000 members who traded nine (9)

different types of securities over a period of three and a half

years. Id. at 140.

14

curities laws. Such is not correct. In fact, it is obvious

that the fraud on the market doctrine could not exist with

out the full disclosure contemplated by the securities laws.

The doctrine assumes that the markets have assimilated

all available information. However, liquidity in the mar

kets requires that investors who have not had an opportuni

ty to read every disclosure made by a company, or who

may not be sophisticated enough to understand all the dis

closures, may nevertheless invest at the market price upon

the assumption that such price represents the consensus

price established by interested and informed investors.

“ Various market professionals still have an incentive to

secure information until a marginal dollar invested in pro

cessing information equals the profits to be made from

trading on superior forecasting.” 8

Petitioners’ argument that the fraud, on the market

doctrine establishes a policy of “ investor’s insurance” im

plies that each investor can collect his full damages in the

event he loses money as a result of securities fraud. This

contention is totally unfounded. Even if individual re

liance is presumed until defendants have an opportunity

to rebut the presumption, it remains necessary for de

frauded investors to prove fraud. What Petitioners seek

8Fischel, Use of Modern Finance Theory in Securities Fraud

Cases Involving Actively Traded Securities, 38 Bus.L. 1, at 4

(1982). Professor Fischel explains it, "Markets may be analyzed

as having two classes of participants. One class will have a

comparative advantage, actors in this class have an incentive

to invest in gathering and analyzing information and to take

actions to affect the market. The other class, however, lacking

a comparative advantage, has no incentive to invest in process

ing information because it cannot profit thereby. The first group

will earn a superior return commensurate with their greater in

vestment skill." Id.

15

is practical immunity from prosecution for corporate

wrongdoers. Even if a defrauded investor can prove lia

bility, the plaintiff still recovers only his out-of-pocket dam

ages. The out-of-pocket damage rule established in Green

v. Occidental, 541 F.2d 1335, 1341 (9th Cir. 1976) (Sneed,

J., concurring); see, e.g., In re LT V Securities Litigation,

88 F.RJD. 134 (NJD.Tex. 1980), permits an investor to re

cover only that portion of his total loss which is due to

defendants’ fraud. While most class actions are indeed

settled, the settlements frequently result in a recovery of

only pennies on the dollar to defrauded investors. This

is scarcely a plan for “ investor insurance,” but is an ef

fective plan for keeping corporate management as honest

as possible.

Petitioners’ argument that upholding fraud on the

market claims under Rule 10b-5 constitutes the effective

repeal of Section 18(a) is similarly unfounded. Petition

ers ignore the fact that in this case Plaintiff alleges a

scheme to defraud the market by disseminating fraudulent

information not only in the SEC filings, but also in pub

licly disseminated reports appearing in The Wall Street

Journal. Section 18(a) limits its remedy to fraudulent

SEC filings. Furthermore, this Court has already re

jected an interpretation of the securities laws that dis

places an action under Section 10(b) merely because of

the availability of express remedies under other sections.

In Herman d MacLean v. Huddleston, 459 U.S. 375, 384-

387 (1983) this court said, “ In savings clauses included

in the 1933 and 1934 Acts, Congress rejected the notion

that the express remedies of the securities laws would

preempt all other rights of action . . . We therefore reject

an interpretation of the securities laws that displaces an

16

action under Section 10(b).” (footnotes omitted). A cu

mulative construction of the securities laws furthers the

broad remedial purposes of the securities laws and fur

thers Congress’ intent in enacting the 1934 Act, “ to im

pose requirements necessary to make [securities] regula

tion and control reasonably complete and effective.” Id.

(quoting 15 USC Section 78b [15 USCS Section 78b]).

Courts have similarly rejected the notion that there

must be additional and differing elements contained in a

Section 10(b) claim to justify a civil remedy under 10(b)

when other remedies were available under other sections

of the Securities Acts. See, e.g., Chemetron Corp. v. Bus

iness Funds, Inc., 718 F.2d 725 (5th Cir. 1983). None

theless, plaintiffs face a more difficult task in stating a

claim under section 10(b) where plaintiff must allege

scienter, as opposed to stating a claim under Section 18

where an allegation of scienter is not a requirement. Ross

v. A.II.Robins Co., 607 F.2d 545, 556 (2d Cir. 1979), cert,

denied, 446 U.S. 949 (1980).

III. THIS COURT HAS PREVIOUSLY CONSIDERED

THE INDIVIDUAL RELIANCE ISSUE IN THE

SECURITIES FRAUD CONTEXT

Two decisions by this Court, Mills v. Electric Auto-

Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970) and Affiliated TJte Citizens

v. United Slates, 406 U.S. 128 (1972), demonstrate this

Court’s recognition that under certain circumstances,

causation in a securities fraud suit is adequately estab

lished by proof of materiality, without direct proof of in

dividual reliance.

In Mills this court expressly noted the judicial utility

in substituting materiality for direct proof of reliance in

17

large securities fraud cases. In Mills, minority share

holders alleged, under Section 14(a) of the Exchange Act,

15 U.S.C. Section 78n(a) (1976), that shareholder approval

of a merger had been obtained via a misleading proxy

statement. This Court acknowledged that “ reliance by

thousands of individuals . . . can scarcely be inquired

into.'’ Id. at 380 (citation omitted). As an alternative,

this Court stated,

There is no need to supplement this [materiality] re

quirement . . . with a requirement of proof of wheth

er the defect actually had a decisive effect on the vot

ing. Where there has been a finding of materiality,

a shareholder has made a sufficient showing of causal

relationship between the violation and the injury . . .

Id. at 384-85. The Mills case is also informative because

this Court found liability without proof of individual re

liance, even though Mills involved an implied remedy un

der Section 14(a). Like Section 10(b) of the Exchange

Act, the remedy under Section 14(a) is a judicially implied

remedy.

In Affiliated Ute, a Rule lQb-5 case, this Court dis

pensed with the need of plaintiffs to establish reliance in

nondisclosure cases involving open market transactions.

Like the Court of Appeals in this case, this Court noted

the distinction between paragraph (2) of rule 10b-5 and

paragraphs (1) and (3), saying that the former is re

stricted to “ the making of an untrue statement of a ma

terial fact and the omission to state a material fact.” Id.

at 152-153. Nevertheless, this Court continued, the first

and third paragraphs are not so restricted, they deal with

a course of business or a device, scheme, or artifice that

operated as a fraud. Id. Thus, this Court held,

1 8

Under the . circumstances of this case, involving pri

marily a failure to disclose, positive proof of reliance

is not a prerequisite to recovery. All that is necessary

is that the facts withheld he material in the sense that

a reasonable investor might have considered them im

portant in the making of this decision . . . . This ob

ligation to disclose and this withholding of a material

fact establish the requisite element of causation in

fact.

Id. 153-154. Affiliated Ute has been widely interpreted as

eliminating plaintiff’s need to establish reliance in non

disclosure cases involving open market transactions. E.g.,

Vervaecke v. Chiles, Heider & Co., 578 F.2d 713, 717 (8th

Cir. 1978); Rifkin v. Crow, 574 F.2d 262-63; Dorfman v.

First Boston Corp., 62 F.R.D. 466, 471 (E.D.Pa. 1974).

The decision by the Court of Appeals below hardly

conflicts with decisions by this Court. To the contrary,

the decision below embraces policies long recognized by

this Court that in certain securities fraud suits, material

ity oftentimes sufficiently establishes causation in fact.

Where through a scheme to defraud or course of business

a defendant disseminates misrepresentations that artifici

ally inflate the market price for a security, plaintiffs

should be entitled to a presumption of reliance upon prov

ing materiality.

IV. PETITIONERS DO NOT HAVE STANDING TO

ASSERT THE CONFLICT WITHIN THE CIR

CUITS AS A REASON FOR THIS COURT TO

GRANT CERTIORARI.

Article III of the constitution limits the judicial power

of the United States to resolution Of “ cases” and “ contro

versies.” As an incident to this requirement, this Court

19

has always required that a litigant have “ standing.” To

have “ standing” a litigant must show that he personally

has some actual or threatened injury. Valley Forge Col

lege v. Americans United, 454 U.S. 464, 471-473, 70 L.Ed.

2d 700, 102 S.Ct. 752 (1982).

On page fifteen of their brief, Petitioners urge this

Court to grant certiorari because of an alleged conflict

within the Circuits. Petitioners contend that the Fifth

Circuit’s decision in this case is in conflict with decisions

in other Circuits. In this case the Fifth Circuit held that

a plaintiff is permitted to assert a fraud on the market

theory under 10b-5(l) and (3), but not under 10b-5(2).

In 10b-5(2) cases, plaintiffs must still prove individual

reliance upon specific misrepresentations. In their opin

ion, the Fifth Circuit recognized that other Circuits permit

the fraud on the market theory under 10b-5(2).9 Never

theless, the Court declined to so hold and for this reason

upheld the District Court’s dismissal of Respondent’s

claim stated under 10b-5(2). The Fifth Circuit’s decision

thus favored Petitioners. Due to the conflict, Petitioners

need only defend themselves against claims stated under

10b-5(l) and (3). Consequently, Petitioners cannot urge

the conflict among Circuits as a basis for this Court to

grant certiorari. Petitioners have suffered no injury.

They have actually benefited from the conflict among Cir

cuits.

It is Respondent who has suffered injury by virtue of

the conflict among Circuit Courts. If Respondent could

9See, e.g., Peil v. Speiser, 806 F.2d 1162-63; Upton v. Docu-

mation, 734 F.2d 740; Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891.

20

have brought this action in the Third or Eleventh Circuits,

her claim under 10b-5(2) would not have been dismissed.

Such is not the case, however, and Respondent has suf

fered an injury in the dismissal of part of her case. Not

withstanding the conflict among Circuit Courts, the injury

is peculiar to Respondent, and Respondent alone may urge

the conflict among the Circuits.

V. THIS CASE DIFFERS FROM BASIC V. LEVIN

SON WHICH IS CURRENTLY BEFORE THIS

COURT.

On page 19 of their brief Petitioners argue that this

Court should consider this case as a companion to Levin

son v. Basic, 786 F.2d 741 (6th Cir. 1986), cert, granted,

107 S.Ct. 1284 (Feb. 23, 1987) (No. 86-279). These cases

differ, however, and should not be considered as com

panion cases. First, as admitted by Petitioners, Basic,

Inc. raises the issue in the context of class certification

under Fed.R.Civ.P. 23(b)(3). The standard of review is

abuse of discretion. In this case, the issues arise under

a Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, presenting a

pure question of law. Thus, these cases are to be re

viewed under differing standards.

Second, Basic, Inc. does not distinguish between causes

of action stated under 10b-5(l) and (3), and causes of

action stated under 10b-5(2). Basic, Inc. considers ma

terial misrepresentations in public statements relating to

the existence of merger negotiations. There is no issue as

to a scheme to defraud or course of business that operated

as a fraud. Basic, Inc. is primarily a 10b-5(2) case. This

case on the other hand hinges on a scheme to defraud or

21

course of business to defraud in violation of Rule 10b-5(l)

and (3).

Further, Basic, Inc. presents questions of whether

sellers may utilize the fraud on the market doctrine as

well as purchasers. This issue is not presented on this

appeal.

--------------- o------------— —

22

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Petition For A Writ

Of Certiorari to review the decision of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit should he denied.

Respectfully submitted,

R oger F. Claxton

Bar Card No. 04329000

2900 First RepublicBank Plaza

901 Main Street, LB-180

Dallas, Texas 75202

(214) 741-6781

Attorney for Respondent

W. D. M asterson

T heodore C. A nderson

K ilgore & K ilgore

2900 First RepublicBank Plaza

901 Main Street, LB-180

Dallas, Texas 75202

(214) 741-6781

J ules B rody

S t u l l , S tu ll & B rody

6 East 45th Street

New York, New York 10017

(212) 687-7230

OF COUNSEL

September 1987.