Sassower v Field Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

August 13, 1992

29 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sassower v Field Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc, 1992. b45b739e-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/33c7f131-51b9-4564-83c6-c5d23a31ff2c/sassower-v-field-petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-of-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

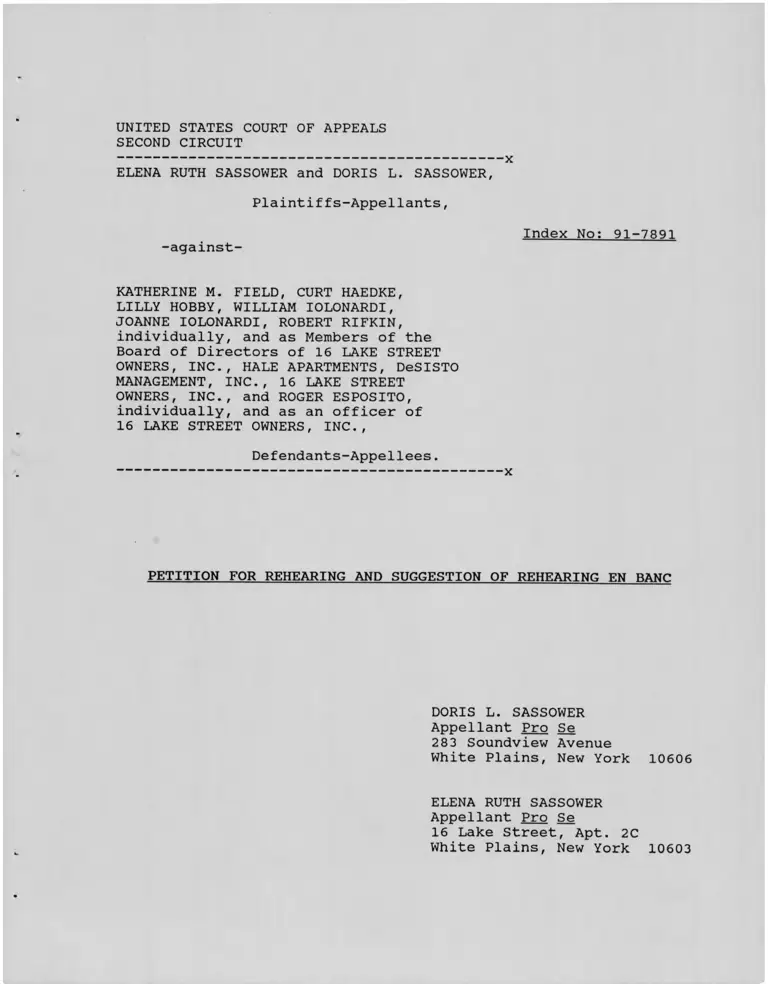

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

SECOND CIRCUIT

--------------------------------------------------- x

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER and DORIS L. SASSOWER,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-against- Index No: 91-7891

KATHERINE M. FIELD, CURT HAEDKE,

LILLY HOBBY, WILLIAM IOLONARDI,

JOANNE IOLONARDI, ROBERT RIFKIN,

individually, and as Members of the

Board of Directors of 16 LAKE STREET

OWNERS, INC., HALE APARTMENTS, DeSISTO

MANAGEMENT, INC., 16 LAKE STREET OWNERS, INC., and ROGER ESPOSITO,

individually, and as an officer of

16 LAKE STREET OWNERS, INC.,

Defendants-Appellees.------------------------------------------ x

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

DORIS L. SASSOWER

Appellant Pro Se

283 Soundview Avenue

White Plains, New York 10606

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER

Appellant Pro Se

16 Lake Street, Apt. 2C

White Plains, New York 10603

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................................... i

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES....................................... 1

ESSENTIAL FACTS FOR PURPOSES OF THIS REHEARING PETITION

What The District Judge Did............................... 4

What The Three Judge Panel Did............................ 5

POINT I:

The Panel Misapprehended That The District Judge "ExplicitlyRelied" On Inherent Authority And Overlooked The Fact

That Even Had He Done So, His Opinion Did Not Make

Prereguisite Findings Required by Oliveri v. Thompson

For Fee-Shifting, And The Record Would Support No SuchFindings....................................................... .

POINT II:

The Decision Is Internally Inconsistent And Conflicts

With Christianburq Garment Co. v. EEOC........................ 11

POINT III:

The Decision Conflicts With Chambers v. Nasco In InvokingInherent Authority Without Prerequisite Findings AndWithout Due Process........................................... .

POINT IV:

The Decision Conflicts With Hall v. Cole And

Decisions Of This Circuit In That It Failed To Fix

Liability In Accordance With Personal Culpability............. 13

POINT V;

The Decision Conflicts With Chambers v. Nasco And

Hazel-Atlas v. Hartford In That The Panel Failed To

Invoke Its Inherent Authority To Adjudicate The Merits

Of Appellants' Rule 60(b)(3) Seeking To Vacate Defendants' Fraudulently Procured Judgment...........................

POINT VI:

The Decision Conflicts With Brocklebv Transport v.

Eastern States Escort And United States v. Aetna In That

Defendants Are Not The Real Parties In Interest Since

The Insured Defendants Were Compensated By The Insurer For The Entire Cost Of Their Legal Defense.............

POINT VII:

The Decision Conflicts With New York Retarded Children

Y_!_Carey In That No Contemporaneous Timesheets Were

Submitted By Defense Counsel And The Award Lacked The

Specificity Required By Decisions Of This Circuit And Of the Supreme Court.............................

CONCLUSION..............................................

EXHIBIT "A": Order of this Court dated December 4, 1991.

EXHIBIT "B": Decision of the Panel dated August 13, 1992

Abbreviation Guide:

Br................

Reply

A-

AA-

Appellants' Brief

Appellants' Reply Brief

Appellants' Appendix

Defendants' Appendix

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Brocklesbv Transport v. Eastern States Escort, 904 F.2d 131 (2nd

Cir. 1990)

Browning Debenture Holders' Committee v. Dasa Corp.. 560 F.2d

1078 (2nd Cir. 1977)

Business Guides v. Chromatic Coirnn. . 498 U.S. ____, 112 L.Ed. 2d

1140, 111 S.Ct ____ (1991))

Calloway v. Marvel Entertainment Group. 854 F.2d 1452 (2nd Cir.

1988)

Chambers v. Nasco, Inc.. Ill S.Ct. 2123 (1991)

Christianburq Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412 (1978)

Dow Chemical Pacific Ltd, v. Rascator Maritime S.A., 782 F.2d 329 (2nd Cir. 1986)

I. Meyer Pincus & Assoc, v. Qppenheimer & Co.. 936 F.2d 759 (2nd Cir. 1991)

Faraci v. Hickev-Freeman Co.. 607 F.2d 1025 (2nd Cir. 1979)

Greenberg v. Hilton International Co.. 870 F.2d 926 (2nd Cir. 1989)

Hall v. Cole. 412 U.S. 1, 93 S.Ct. 1943, 36 L.Ed.2d 702 (1973)

Hazel-Altas Glass Co. v. Hartford-Empire Co. . 322 U.S. 238, 64S.Ct. 997, 88 L.Ed. 1250 (1944)

Hensley v. Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424, 103 S.Ct. 1933, 76 L.Ed.2d 40 (1983)

Leber-Krebs, Inc, v. Capitol Records. 779 F.2d 895 (2nd Cir. 1985)

-i-

McMahon v. Shearson/American Express, Inc.. 896 F.2d 17 (2nd Cir.

— York— Ass'n. for Retarded Children v. Carev. 711 F.2d 1136 (2nd Cir. 1983)

Oliveri v. Thompson. 803 F.2d 1265 (2nd Cir. 1986)

Roadway Express Inc, v. Piper. 447 U.S. 752, 100 S.Ct. 2455, 65L. Ed.2d 488 (1980)

Sanko S.S. Co.. Ltd, v. Galin. 835 F.2d 51 (2nd Cir. 1987)

United States v._Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. . 338 U.S. 366 70S.Ct. 207, 94 L.Ed. 171 (1949)

United—States—v_._International Brotherhood of Teamsters. 948 F 2d1338 (2nd Cir. 1991)

Civ.R. 11; 60(b)(3)

28 U.S.C. § 1927

This Petition seeks rehearing of the August 13, 1992

Decision [hereafter "the Decision"] by a three-judge panel of

this Court ["the Panel"], sustaining a counsel fee/sanctions

award of nearly $100,000 against two civil rights plaintiffs.

The issues involved are of transcending national

importance not only to civil rights litigants, but to all

litigants, since the Panel relies on inherent power to sustain an

"extraordinary" fee award (at 6389) against Appellants where

standards of other sanctioning provisions were not met— yet

simultaneously fails to invoke inherent power to prevent fraud on

the Court where the standards of Rule 60(b)(3) were met by

Appellants in their uncontroverted formal motion to vacate

Defendants' fraudulently procured judgment. Such discriminatory

use of inherent power disregards due process, equal protection,

and bedrock law of the Supreme Court and this Circuit.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the Decision conflicts with I. Meyer

Pincus & Assoc, v. Oppenheimer & Co. . 936 F.2d 759 (2nd Cir.

1991), in affirming the award on grounds other than those relied

on by the District Judge, without support in the record. [Pt. I]

2. Whether the Decision conflicts with Hazel-Atlas

Glass Co. v. Hartford-Emoire Co.. 322 U.S. 238 (1944), reaffirmed

in Chambers v. Nasco. Ill S.Ct. 2123 (1991), as well as Leber-

Krebs, Inc, v. Capitol Records. 779 F.2d 895 (2nd Cir. 1985), in

that, apart from Appellants' Rule 60(b)(3) motion, courts have

inherent authority to vacate judgments obtained by fraud. [Pt. V]

3. Whether the Decision conflicts with established

-1-

equitable principles and equal protection rights in that it

failed to rule on Appellants' objection that the District Judge

did not adjudicate their "unclean hands defense", detailed and

documented in their Rule 60(b)(3) motion.

4. Whether the Decision misapplies Chambers v.

Nasco. by expanding inherent authority to sustain sanctions in a

case where, unlike Chambers; (a) Appellants were denied a

hearing as to liability for sanctions and the amount thereof;

(b) No detailed findings were made by the District Judge; (c) the

District Judge relied on other sanction rules— not his inherent

authority; (d) the Panel made no findings that the sanction rules

relied on by the District Judge were inadequate; and (e) the

Panel cited no record references to support invoking the inherent

authority of the District Judge and itself made no findings based

on independent review of the record. [Pt. Ill]

5. Whether the Panel's interpretation of Chambers v.

Nasco is in conflict with Oliveri v. Thompson. 803 F.2d 1265

(1986) and Christianburo Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412

(1978), and represents a sub silentio repudiation of the

"American Rule" against fee-shifting, as well as of the express

limitations of 28 U.S.C. §1927. [Pts I, II]

6. Whether the Decision's expansion of Chambers v.

Nasco. supra, invidiously discriminates against Appellants by

imposing liability against them for litigation conduct of their

attorneys— for which their attorneys were not assessed. [Pt. IV]

7. Whether the Decision conflicts with this Circuit's

decisions in Browning Debenture Holders' Committee v. Dasa Coro..

-2-

560 F.2d 1078 (1977), and Dow Chemical Pacific Ltd, v. Rascator

Maritime S.A., 782 F.2d 329 (1986), in sustaining the imposition

of joint liability upon both Appellants for the full amount of

the sanctions awarded, without differentiation of the separate

liability of each and with no apportionment based on respective

individual culpability. [Pt. IV]

8. Whether the Decision conflicts with this Circuit's

decision in Faraci v. Hickev-Freeman Co.. 607 F.2d 1025 (1979)

and invidiously discriminated against Appellant Doris Sassower

in denying her the opportunity to make a showing as to her

ability to pay the potential full liability for the nearly

$100,000 sanctions imposed.

9. Whether the Decision conflicts with the specific

language of 28 U.S.C §1927, as well as the standards of Oliveri,

supra, and invidiously discriminates against lawyer-Plaintiff

Doris Sassower by imposing liability upon her for litigation

conduct when she was represented by counsel, and with no

correlation of the award to any alleged bad-faith conduct either

when she was unrepresented or when she was acting pro se. [Pts.

I, IV]

10. Whether the Decision conflicts with United States

v. Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. . 338 U.S. 366 (1949) and this

Circuit's decision in Brocklesbv Transport v. Eastern States

Escort, 904 F.2d 131 (1990), in that the Panel failed to rule on

Appellants' Motion to Dismiss and threshold jurisdictional

objection that the fully-insured Defendants are not "parties in

interest" and that any fee award constitutes a "windfall" since

-3-

no defense costs were incurred by them. [Pt. VI]

11. Whether the Decision conflicts with this Circuit's

decision in New York Ass'n. for Retarded Children v. Carey. 711

F.2d 1136 (1983), citing Hensley v. Eckerhart, 103 S.Ct. 1933,

1943 (1983), in that no contemporaneous time records were

submitted by defense counsel and the District Judge failed to

make specific findings identifying how he computed the amounts

awarded, the particular services being compensated, the

reasonableness and necessity thereof, the number of hours and

rates being allowed, and that said rates accorded with prevailing

market rates in the community. [Pt. VII]

ESSENTIAL FACTS FOR PURPOSES OF THIS REHEARING PETITION

What the District Judge Did:

1. The District Judge summarily denied Plaintiffs'

Rule 60(b)(3) motion, mischaracterizing it as "reargument".

Although the motion was also explicitly entitled "Factual

Rebuttal", and submitted in opposition, to Defendants' counsel

fee/sanctions applications— with a fully documented paragraph-by

paragraph refutation thereof— the District Judge treated such

rebuttal as non-existent.

2. The District Judge assessed Plaintiffs $92,000 as

counsel fee/sanctions under the Fair Housing Act, as amended

after commencement of this action, purportedly to reimburse the

"prevailing" fully-insured Defendants, who had not paid a dime

out of pocket for defense of the action.

3. An alternative award was also made by the District

Judge in an identical aggregate amount under Rule 11 ($50,000)

-4-

and 28 U.S.C. 1927 ($42,000) which would come into play solely

against Plaintiffs— not their counsel or their former co-

Plaintiff— in the event his award under the Fair Housing Act was

not upheld. The District Judge did not explain the basis of

these two allocations. As to his Rule 11 award, he stated:

"These sanctions are not directly connected with the

fees expended by the defense attorneys, nor can they be

prorated in that fashion. We find that the appropriate

sanction against the Plaintiffs for commencing and

prosecuting this meritless litigation to be in the sum

of $50,000." (A-37-8)

Likewise, the District Judge did not correlate the $42,000 award

under §1927 to any "costs, expenses, attorneys' fees reasonably

incurred" as a result of any specific conduct by either Plaintiff

(A—37). Additionally, the Rule 11 or the 28 U.S.C. §1927 awards

made no distinction between the two Plaintiffs as to their

separate liabilities.

4. In passing, the District Judge indicated that he

had inherent authority under Chambers v. Nasco. supra (A-17; A-

24). He did not state, however, that he was then exercising such

inherent authority or the amount that would be encompassed

thereunder were he to do so. Nor did the District Judge specify

any conduct by either Plaintiff outside Rule 11 and §1927 which

would require his inherent authority to address.

5. Expressly rejected by the District Judge were

Plaintiffs' due process objections based on their asserted right

to an evidentiary hearing before determination of liability for

sanctions and the amount of the award (A-ll).

What the Three-Judge Panel Did:

1. The Panel affirmed the District Judge's denial of

-5-

Appellants' Rule 60(b)(3) motion by adopting virtually verbatim

his characterization of the motion as one for "reargument" (at

6399)--although such mischaracterization was exposed as

fallacious in Appellants' Brief (Br. 27-33). The Panel did not

address Appellants' "unclean hands" defense, which that motion

documented. Nor did the Panel rule on the significance of the

information and documents crucial to Appellants' discrimination

case, which the District Judge had allowed Defendants to withhold

without sanction, including: (a) statistical data as to the

number of Board-approved purchasers who were Jews and/or

unmarried women; (b) completed purchase applications of all

purchasers, with supporting processing information; and (c)

information concerning the adoption and distribution of the Co-

Op's "Guidelines for Admission"— explicitly applicable to

purchases by "minorities or single women" (See Br. 16-7, 52-3;

Reply 21-2, 26).

2. The Panel vacated the District Judge's award

under the Fair Housing Act, stating:

"...the plaintiffs' suit adequately alleged the

elements of a prima facie case of discrimination and

presented a factual dispute for the jury as to whether

the plaintiffs had proven that the defendants'

articulation of non-discriminatory reasons were

pretextual...There is no finding that the plaintiffs

did not believe that they had been the victims of

discrimination. Moreover,...there is no finding that

the plaintiffs' had given a false account of the basic

facts alleged to support an inference of discriminatory

motive. Nor is this a case where the trial judge

expressed the view that no reasonable jury could have

found in plaintiff's favor but reserved ruling on a

motion for a directed verdict and submitted the case to

the jury simply to have a verdict in the event that a

court of appeals might have disagreed with his

subsequent ruling to set aside a plaintiffs' verdict,

had one been returned..." (at 6394)

-6-

3. Having concluded that Plaintiffs' case was not

"meritless" or brought in bad faith, the Panel then ruled on the

District Judge's fail-back sanction alternatives:

(a) It vacated the proposed alternative Rule 11

award because the District Judge failed to meet the basic

requirement for its invocation: i.e. , he did not identify any

specific offending document (at 6395). However, the Panel did

not remand1, saying:

"Since...the $50,000 portion of the award grounded on

Rule 11 is equally supportable by the exercise of the

District Court's inherent authority, we need not return

the matter to Judge Goettel for a precise

identification of which documents warranted Rule 11

sanctions." (at 6395)

The Panel thus maintained intact the uncorrelated Rule 11 award,

which the District Judge expressly predicated on his view that

the litigation was "meritless" (A-38)— a view rejected by the

Panel when it disallowed counsel fees under the District Judge's

original basis, the Fair Housing Act (at 6394).

(b) Observing that §1927 was "designed to curb abusive

tactics by lawyers", the Panel also rejected out of hand the

District Judge's attempt to impose such sanctions against Elena

Sassower, a non-lawyer (at 6397). Nonetheless, applying §1927 to

plaintiff Doris Sassower because she happened to be a lawyer, it

sustained an undefined portion of the undifferentiated $42,000

1 Cf. U.S.A. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters,

where this Court remanded after vacating a Rule 11 award,

stating: "An adjustment to one of the sanctions awards... would

probably affect the underpinnings of the other, and might lead

the district court, in the exercise of its discretion to reduce

or adjust the other award." at 1347. See. also, Sanko, and

Business Guides.

-7-

sanction against her. This disregarded the following facts: (i)

Doris Sassower had been represented by counsel for approximately

half the period of the litigation2; (ii) The District Judge had

never correlated any of the monetary sanction under §1927 to

specific conduct by Doris Sassower (A-37) at any time; (iii) The

only three instances cited by the District Judge to support his

"finding" of bad faith by Plaintiffs sanctionable under §1927 (A-

20-4) were unsubstantiated by the record— a fact fully detailed

in Appellants' Brief (Br. 25-6; 33-39; 39-40). [see discussion at

pp. 14-15 herein]

4. The Panel then sustained the balance of the

$92,000 counsel fee/sanctions award, stating:

"Judge Goettel explicitly relied, alternatively, on his

inherent authority in the portion of his Opinion

awarding Rule 11 sanctions, see Opinion at 11, and in

the portion awarding section 1927 sanctions, Opinion at

18. We may reasonably infer that he intended to base

the $50,000 portion of the award, alternatively, on his

inherent authority, to whatever extent it was not

supportable by Rule 11, and to base the $42,000 portion

of the award, alternatively on his inherent authority,

in the event section 1927 was deemed inapplicable to

Elena Sassower." (at 6397-8) (emphasis added)

5. No findings were made by the Panel as to what was

being sanctioned under the $50,000 figure, the former Rule 11

sanction award (at 6395-8) . Nor did the Panel cite any, instance

of conduct by Elena Sassower entitling an undefined portion of

the $42,000 sanctions under §1927 to be applied against her via

the District Court's inherent power (at 6397-8).

2 The Panel's statement that Appellants "filed their suit

pro se in 1988" (at 6389) is one of numerous serious factual errors. Both Appellants were then represented by counsel— as

they were for substantial periods thereafter.

-8-

6. The Panel did not address Appellants' due process

objections based on their asserted right to an evidentiary

hearing as to liability for sanctions and the amount thereof, as

well as to an impartial judge.

7. The Panel failed to rule on Appellants' November

29, 1991 Motion to Dismiss, which was "referred to the panel that

will hear the appeal" (Order dated December 4, 1991, Ex. "A").

POINT 1: The District Judge did not invoke his

inherent authority to fee—shift litigation costs which he was in

a position to do, had he deemed it appropriate. That the

District Judge deemed it inappropriate can be inferred from the

fact that although he was uncertain that his fee-shifting award

under the Fair Housing Act would be upheld, he nonetheless

explicitly relied on that Act— not his inherent authority to

shift litigation costs (A-34-7).

Even in devising a fail-back to the Fair Housing Act,

the District Judge did not reach out to his inherent authority to

shift fees under the "bad faith exception to the American Rule".

Rather, he proceeded under a combination of Rule 11 and §1927 (A-

37-8), neither of which are fee-shifting provisions.

These two distinct decisions by the District Judge: (1)

to use the Fair Housing Act, and (2) to devise a Rule 11/§1927

alternative must be seen as an informed assessment by him that

the record would not permit him to meet the stringent standards

for fee-shifting via his inherent authority, notwithstanding the

recent Supreme Court decision in Chambers, which he cited.

The District Judge cited Oliveri v. Thompson for the

-9-

proposition that bad-faith is a prerequisite to §1927 sanctions

(A-20) and had before him the standard for fee-shifting

enunciated therein:

"To ensure... that fear of an award of attorneys' fees

against them will not deter persons with colorable

claims from pursuing those claims, we have declined to

uphold awards under the bad-faith exception absent

both 1'clear evidence' that the challenged actions 'are

entirely without color and [are taken] for reasons of

harassment or delay or for other improper purposes,''

and 'a high degree of specificity in the factual

findings of rthe] lower courts.'" Oliveri. at 1272 (citing 2nd Circuit cases) (emphasis added)

See also McMahon v. Shearson/American Express, at 23-4. The

extent to which the District Judge did not meet the standards

required for an award under inherent authority is highlighted by

the only instances in his Opinion as showing Plaintiffs' alleged

bad-faith, cited in the context of §1927 sanctions (at A-14-7).

Because the Decision repeats these instances (at 6391-

2) to support fee-shifting for the totality of the litigation,

rather than specific conduct to be sanctioned under §1927, they

are herein set forth to demonstrate their inaptness for

sanctions under any theory:

(a) "plaintiffs 'attempted to communicate directly with the

defendants'" (at 6391): The record shows (AA-47) that the

letter to Defendants was not sent by either Elena Sassower or Doris Sassower, but by John McFadden, the former co-Plaintiff and

seller of the subject apartment3 for the stated purpose of effectuating a settlement.

(b) "the Magistrate... had recommended dismissal of thecomplaint because of Doris Sassower..." (at 6391-2): The record

shows (see discussion and record references cited in Br. 33-39)

that the Magistrate's recommendation and the District Judge's

Opinion based thereon were factually unjustified, rendered

3 In fact, the District Judge's Opinion acknowledges Mr.

McFadden's authorship of the letter to Defendants— the

"impropriety" of which it acknowledged "can be overlooked" (A-32).

-10-

without due process, and even without a formal motion for Rule 37

sanctions ever made by defense counsel. The lack of due process

precludes its use as a basis for a "bad faith" finding against

her, a fact recognized by Chambers v. Nasco:

"A court must... comply with the mandates of due

process...in determining that the reguisite bad faith

exists..., see Roadway Express, supra. at 767, 100

S.Ct. at 2464." Chambers at 2136

(c) Doris Sassower's "role in assisting another attorney " 'in conducting incredibly harassing depositions *", and "'particularly

shocking and abusive Questioning1" (at 6392): Examination of

the transcript shows this statement to be factually false (Br.

39-40), the guestions were not improper, and Doris Sassower's

entire participation consisted of two wholly innocuous one-line comments: (1) "She doesn't know when she was born." (AA-48); and

(2) "Are you serious?" (AA-59).

As a matter of law, the foregoing three instances do

not show bad faith to constitute a basis for §1927 sanctions,

which is the context in which they were cited by the District

Judge, nor do they constitute a basis upon which the Panel could

activate the District Judge's inherent power against either

Plaintiff, Roadway Express. Inc., at 2465. Indeed, as this Court

recognized in Dow Chemical Pacific. at 345, such isolated

instances, even were they legitimate, are too inconsequential to

sustain an award representing the totality of three year's

litigation costs.

Since the District Judge cited no other specific

instances of alleged "bad faith", the exception to the "American

Rule" cannot be sustained on the basis of his Opinion— and the

Panel cited no basis in the record. Indeed, the Decision does

not cite the record once.

POINT II: An award to Defendants under the Housing

Act involves a lesser standard than under inherent power, as

Christianburg itself makes clear. Christianburg requires only

that an action be "meritless" or without foundation. It does not

require a showing that the action was brought in bad faith, which

awards under a court's inherent power require:

[I]n enacting [the fees provision] Congress did not

intend to permit the award of attorney's fees to a

prevailing defendant only...where the plaintiff was

motivated by bad faith...[I]f that had been the

intent...no statutory provision would have been

necessary, for it has long been established that even

under the American common-law rule attorney's fees may

be awarded against a party who has proceeded in bad faith." 434 U.S. at 419.

Here, the Panel held that there was no basis to find

that the action was meritless or that the Plaintiffs "did not

believe that they had been the victims of discrimination", i.e.

that they had brought the action in bad faith. Thus, it was

inconsistent with Christianburg and Chambers. as well as Oliveri

and other precedents of this Court, to uphold fee-shifting based

on inherent power that must rest on a bad-faith finding.

POINT III: The Panel turned to inherent authority as

an alternative sanctioning source, with no finding that the

sanctioning rules were inadequate. As the five—four majority in

Chambers stated:

"...when there is bad-faith conduct in the course of

litigation that could be adequately sanctioned under the rules, the court ordinarily should rely on the

rules rather than the inherent power." at 2136.

This view was expressed even more strongly by three of the four

dissenting justices (including the Chief Justice):

"Inherent powers are the exception, not the rule, and

their assertion requires special justification in each

case...Inherent powers can be exercised only when necessary, and there is no necessity if a rule or

statute provides a basis for sanctions. It follows

that a district court should rely on text-based

authority derived from Congress rather than inherent

-12-

power in every case where the text-based authority

applies." at 2143.

The fact that the Panel did not find that the

sanctioning rules were not "up to the task" Chambers. 2126, 2136.

is further reflected by its express statement in not remanding

the $50,000 Rule 11 sanction award to the District Judge so that

he might specify what "offending documents" he had in mind4 (at

6395).

Moreover, the Panel's ruling that §1927 could not be

used against Elena Sassower was irrelevant for purposes of

invoking inherent authority--since no sanctionable conduct by her

was cited by either the District Court or the Panel. Under such

circumstance, Elena Sassower's non-lawyer status was irrelevant,

there being nothing to sanction in any case.

Additionally, unlike Chambers, Appellants were denied

their right to a hearing before sanctions liability and the

$92,000 sum were awarded. Thus absent was the most fundamental

prereguisite for invocation of inherent authority, reiterated by

Chambers, 2135, in no uncertain terms: "due process".

Also distinguishable from Chambers, the District Judge

did not invoke his recognized inherent authority, but chose

instead to proceed under non-fee-shifting sanctioning provisions

and further, unlike Chambers, made no detailed findings to fee-

shift a totality of litigation costs.

POINT IV: In approving fee-shifting under inherent

4 The Panel's speculation that the District Judge "probably

had in mind principally the complaint" (at 6395) is erroneous

since the complaint was signed by neither Plaintiff.

-13-

power, the Decision conflicts with Hall v. Cole. cited by

Browning. at 1089, for the proposition that "bad faith is

personal". The failure to differentiate the respective

liabilities of the Appellants and to hold them liable for

conduct of lawyers who were representing them conflicts also with

Greenberg v, Hilton, at 939, and Calloway v. Marvel, at 1474.

Moreover, Browning specifically held that:

"in an action not itself brought in bad faith, an award

of attorneys' fees should be limited to those expenses

reasonably incurred to meet the other party's

groundless, bad faith procedural moves.", at 1089.

POINT_V: As Chambers points out, at 2132— citing

Hazel-At las--"fraudulently begotten judgments" are such a

defilement of the judicial process that a court can vacate it sua

sponte. and can even "conduct an independent investigation in

order to determine whether it has been the victim of fraud".

These powers exist apart from its duty to adjudicate motions

properly before it under Rule 60(b)(3).

Neither the Panel nor the District Judge dealt with the

fraud issues of Appellants' 60(b)(3) motion because they

erroneously viewed the motion as "reargument"^. Such view—

totally unsupported by the record (Br. 27-33)— would not relieve

either tribunal from its duty to independently ascertain the

validity of the fraud allegations, documented by Appellants'

5 This Court considered "the opportunity to litigate" the

issue of fraud and misrepresentation to be critical and in Leber-

Krebs. supra. reversed Judge Goettel for summarily denying such

opportunity. Judge Goettel— the District Judge herein— similarly

denied Appellants their right to an adjudication of Defendants'

fraudulent conduct— a fact detailed and documented in the opening

pages of their Rule 60(b)(3) motion (Aff. A: Pt 2: pp. 7-11).

-14-

uncontroverted motion. Indeed, such invocation of inherent power

was mandated because the parties Appellants charged with fraud

were seeking to profit from it by a fee award.

POINT VI: The Panel's failure to decide the threshold

jurisdictional question raised in Appellants' separate Motion to

Dismiss, as well as in their Reply Brief (pp. 2-8), conflicts

with Brocklesbv Transport, citing United States v.— Aetna:

"...Under federal law, if an insurer has compensated an

insured for an entire loss, the insurer is the only

party— in—interest, and must sue in its own name. . ."

Brocklesbv. at 133 (emphasis added).

POINT VII: The Decision conflicts with New York

Ass'n. for Retarded Children v. Carey, at 1147:

"...contemporaneous time records are a prerequisite

for attorney's fees in this Circuit. See Hensley v.

Eckerhard. . . .we. . .convert our previously expressed preference for contemporaneous time records...into a

mandatory requirement, as other Circuits have done..."

There were no contemporaneous time records submitted by

defense counsel (Br. at 43)— as further conceded by their

evasiveness and silence at oral argument when the question was

specifically asked by Judge Newman, the author of Carey.

Moreover, the $92,000 award confirmed by the Panel was devoid of

all specificity— failing even to set forth the number of hours

compensated and the rates allowed (A-34-8; Br. 43-5, 48).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, it is respectfully prayed

that a rehearing, en banc. be granted so that the Decision may be

corrected to conform with the factual record and controlling law.

Respectfully submitted,

DORIS L. SASSOItfER, Pro Se ELENA RUTH SASSOWER, Pro Se

4/90 United States Court ol A p p e a ls

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT'X

SASSOWER,

Appella

-v-

FI ELD,

l/x r ih o r l title

M OTION BY: (Name, address and tel. no. of law firm and o f

attorney in charge o f case)

Elena Ruth Sassower, Pro Se

16 Lake St., Apt. 2C White Plains

Doris L. Sassower, Pro Se

283 Soundview Avenue, White Plains

Each motion must be

acocrpanied by a support

affidavit.

91-7891

O r t , i n fNyresh+r

NOTICE OF MOTION

state type o f m otion

1060-3

Has consent of opposing counsel:

A been sought?

B been obtained?

Has service been effected?

Is oral argument desired1

(Substantive motions only)

Requested return date: December

(See Second Circuit Rule 27(b))

Has argument date of appeal been set:

A by scheduling order?

B by firm date of argument notice?

C. I f Yes, enter date:_________________

10606

£e4«r--a-L—and- substantive -

TJ^>1: l G f^am c, address and tel no of law

firm and o f attorney in charge o f case)

Lawrence Glynn, Esq. 914-761-040'

Marshall, Conway & Wright

212-619-4444

Dennis Bernstein, Esq.

914-779-9099

□ Yes

□ Yes

rsr'Ves

LJ No

R 'N o

□ No

t l No

□ Yes □ No

5, 1991

□ Yes

□ Yes

□ No

□ No

EMERGENCY MOTIONS, MOTIONS FOR STAYS It

INJUNCTIONS PENDING APPEAL

Has request for relief been made below1

(See F R A P Rule A)

Would expedited appeal eliminate need

for this motion?

If No, explain why not:

jurisdiction is a threshold question

which must be determined prior to

W ill the parties agree to m alM M rftO C t ion of appeal

status quo until tfie motion is heard? □ Yes □ No

□ Yes R^No

Judge or agency whose order is being appealed:

Judge Gerard L. Goettel

Brief statement of the relief requested:

New Scheduling Order

Vacate Judgment for counse

Complete Page 2 of This Form subject

1 fees/sanctions for

matter jurisdiction

lack of

By: (Signature o f attorney) Appearing for: (Name o f party)

Signed name must be printed beneath J f , ------- Date

( i f U e h t

---- _--------------------------------------------------------------- ORDER -----------

Kindly leave this space blank

AnpCltant or Petitioner:

fa P la in t if f □ Defendant

Appellee or Respondent:

□ P la in tiff □ Defendant

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the motion be and it hereby is

M o-b on an a d d i t i o n a l 6("bfne

Y b o i i o n f d v a c a t e o{ f c e s

\\ea< dW apv^l

\S deDied and

l-i ( r i f e , iedT u - t t ix . 1 ^ i l l

cSk "S9 "

DEC 0 4 1991 -------------------------------

Date f’.WruH Jn4fe

" 0 ' \ ^ 6/V- &fvirr " C ■' "if afvoii tehstfit

03

*

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 954— August Term 1991

Argued: February 28, 1992 Decided: August 13, 1992

Docket No. 91-7891

----- *

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER, DORIS L. SASSOWER,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

KATHERINE M. FIELD, CURT HAEDKE, LILLY HOBBY,

WILLIAM IOLONARDI, JOANNE IOLONARDI, ROBERT

RIFKIN, individually, and as M em bers o f the Board o f

D irectors o f 16 Lake Street O w ners, In c ., HALE

APARTMENTS, D e SISTO MANAGEMENT INC., 16

LAKE STREET OWNERS, INC., ROGER ESPOSITO, ind i

v idually , and as an o fficer o f 16 L ake Street O w ners,

*nc'’ Defendants-Appellees.

Before:

*

LUMBARD, NEWMAN and WINTER,

Circuit Judges.

♦ —

Appeal from a supplemental judgment of the District

Court for the Southern District of New York (Gerard L.

6387

Goettel, Judge) requiring pro se plaintiffs to pay defen

dants’ attorney’s fees and expenses of $93,350 as a sanc

tion for the vexatious conduct of unsuccessful litigation

claiming housing discrimination.

Affirmed as to liability, affirmed as to amount with

respect to Doris Sassower, and vacated and remanded as

to amount with respect to Elena Sassower.

♦

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER, plaintiff-appellant

pro se , White Plains, N.Y.

DORIS L. SASSOWER, p la in tiff-appellan t pro

se, W hite P lains, N.Y.

DENNIS T. BERNSTEIN, Tuckahow, N.Y., for

defendant-appellee Hale Apartments.

LAWRENCE J. GLYNN, White Plains, N.Y ., for

defendants-appellees Field, Haedke,

Hobby, William Iolonardi, Joanne

Iolonardi, Rifkin, & 16 Lake St. Owners,

Inc.

STEVEN L. SONKIN, New York, N.Y. (Mar

shall, Conway & Wright, New York,

N.Y., on the brief), for defendants-

appellees DeSisto Management, Inc. &

Esposito.

(Julius L. Chambers & Charles Stephen Ral

ston, New York, N.Y., submitted an ami

cus curiae brief for NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.)

♦

6388

JON O. N e w m a n , Circuit Judge:

This appeal from a supplemental judgment imposing

sanctions upon two unsuccessful plaintiffs for the vexa

tious conduct of litigation involves the extraordinary rem

edy of an award of nearly $100,000 assessed against pro

se litigants, occasioned by extraordinary conduct. The

judgment was entered by the District Court for the South

ern District of New York (Gerard L. Goettel, Judge),

requiring Doris L. Sassower and her daughter, Elena Ruth

Sassower, to pay defendants’ attorney’s fees and expenses

of $93,350 at the conclusion of their unsuccessful suit

claiming housing discrimination. We conclude that Judge

Goettel was abundantly justified in imposing sanctions

against both plaintiffs and that the amount imposed upon

Doris Sassower was fairly determined, but that the

amount of the sanction imposed on Elena Sassower must

be reconsidered in light of her limited financial resources.

Facts

Doris and Elena Sassower filed their suit pro se in

1988, alleging violation of the Federal Fair Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601-3631 (1988), and other federal and

state law claims. At various stages of the litigation, they

were represented by counsel. Doris Sassower was then a

member of the bar, although her current status is in some

doubt. See Attorney Sanctioned by Court of Appeals,

N.Y.L.J. (Sept. 11, 1991). Defendants include the corpo

rate owner of a cooperative apartment building in White

Plains, New York, and directors and an officer of the cor

porate owner. The plaintiffs alleged that the defendants

had discriminated against them by rejecting their appli

cation to acquire an apartment in the building through

purchase of coop stock shares and assignment of a pro-

6389

prietary lease from a former occupant. Plaintiffs alleged

discrimination on account of their status as single, Jewish

women. Defendants contended that the rejection had noth

ing to do with the status of the plaintiffs, but was based

primarily on the owner’s disapproval of the use to be

made of the apartment. While approval was being sought,

the apartment was occupied by George Sassower, the for

mer husband of Doris and the father of Elena.1 Evidence

at trial indicated that he was arrested at the apartment for

what the District Court understood was the illegal practice

of law. Evidence also indicated that the occupants of the

apartment building included Jews and single women, a

circumstance tending to refute plaintiffs’ claim concern

ing the basis for their rejection.

After some of the defendants were dismissed on motion

for summary judgment, see Sassower v. Field, 752 F.

Supp. 1182 (S.D.N.Y. 1990); Sassower v. Field, 752 F.

Supp. 1190 (S.D.N.Y. 1990), the case was tried before a

jury for seven days. The jury answered specific inter

rogatories, rejecting all of plaintiffs’ claims, including the

claim that the religion, gender, or marital status of the

plaintiffs was a reason for the rejection of their applica

tion to purchase the apartment.

After entry of judgment for the defendants, the District

Court granted the defendants’ request for counsel fees and

costs as prevailing parties pursuant to the Fair Housing

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(2) (1988). In the alternative the

Court imposed sanctions against the plaintiffs pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 11, 28 U.S.C. § 1927 (1988), and the

Court’s inherent power “because of their tactics of delay,

oppression and harassment.” District Court opinion of

August 12, 1991 (hereafter “Opinion”), at 18. Judge Goet-

1 George Sassower is a disbarred attorney whose proclivity for

frivolous and vexatious litigation has repeatedly resulted in sanctions.

6390

tel carefully reviewed the extraordinary pattern of vexa

tious litigating tactics engaged in by the plaintiffs during

the pendency of the litigation and concluded that they had

acted “in bad faith, vexatiously and unreasonably.” Id. at

14 (footnotes omitted). As he stated, “The Sassowers pur

sued this litigation as if it was a holy war and not a court

proceeding, managing these proceedings in a fashion that

vexatiously, wantonly and for oppressive reasons

increased the legal fees enormously.” Id. at 13.

As summarized by the District Court, the plaintiffs

conduct included the following:

They made several unsupported bias recusal motions

based upon this court’s unwilling involvement in

some of the earlier proceedings initiated by George

Sassower. . . . There were continual personal

attacks on the opposing parties and counsel. . . . In

virtually every instance where a court ruling was not

satisfactory to them, plaintiffs routinely made a

motion to reargue. In addition, plaintiffs filed two

improper interlocutory appeals which were subse

quently withdrawn. . . . Finally, they have now filed

a mammoth motion for a new trial and sanctions

against opposing counsel which seeks to reargue vir

tually every aspect of the litigation for the third time.

Opinion at 13-14 (citations and footnotes omitted). The

District Judge also noted that the plaintiffs “attempted to

communicate directly with the defendants rather than

through counsel in order to force through their settlement

demands.” Id. at 14 n.10. Previously the Magistrate Judge

supervising discovery had recommended dismissal of the

complaint because of Doris Sassower’s egregious failure

to make discovery as directed by the Court. The District

Judge, though noting misbehavior warranting sanctions,

6391

declined to dismiss because the complaint would still be

pursued by Elena. He nonetheless observed:

It is patently clear that Doris L. Sassower has been

guilty of attempting to manipulate the court by

appearing as attorney on those matters which could

assist her case while refusing to be deposed herself,

claiming health problems. We were compelled at an

earlier time to allow [her] to appear pro se and to

relieve her attorney because of the law of this Cir

cuit, even though we could foresee the type of

manipulation that has frequently occurred.

Id. at 16. The Court also noted her recalcitrance at her

own deposition and her role assisting another attorney “in

conducting incredibly harassing depositions of certain of

the defendants.” Id. at 17. Some of that questioning

included what the Court termed “particularly shocking

and abusive” questioning of a Black member of the coop’s

board of directors, questioning laced with racial innuendo.

Id. at 22.2 Repeatedly throughout the litigation, the Dis

trict Judge cautioned the plaintiffs that their vexatious and

harassing conduct, if continued, was likely to incur mon

etary sanctions at the conclusion of the case.

2 Judge Goettel noted that Doris Sassower’s vexatious tactics had been

observed by other courts. He quoted the following comments of Justice

Samuel G. Fredman of the New York Supreme Court, County of West

chester:

From the relatively simple molehill of potential issues which

could possibly arise from such conduct, Sassower has created a

mountain of legal, factual and even political abracadabra. Her

actions have taken an inordinate amount of this Court's time and

tested its patience beyond the wildest imagination. . . . [M]onths

of actual court time [were] spent in permitting Sassower to pre

serve her rights by trick and chacanery beyond the concept of most

any lawyer who practices in our courts. She is indeed sui generis

in her actions . . . .

Id. at 14-15 n .l l (quoting Breslaw v. Breslaw, Slip Op., Index No.

22587/86 at 2, 12 (June 24, 1991)).

6392

The District Judge awarded to the defendants a total of

$92,000 in fees and $1,350 in expenses, and imposed lia

bility for these amounts jointly upon Doris and Elena Sas

sower. Plaintiffs appeal from the award of attorney’s fees

and from the denial of their motion for a new trial and

their request to have sanctions imposed on the defendants.

Discussion

I. Attorney’s Fees

A. Fair Housing Act. At the time the complaint in this

case was filed, the Fair Housing Act authorized an award

of attorney’s fees only to a prevailing plaintiff. 42 U.S.C.

§ 3612(c) (1982). The current version, enacted in 1988,

Pub. L. No. 100-430, § 8(2), 102 Stat. 1633 (1988),

authorizes fees for a prevailing party. 42 U.S.C.

§ 3613(c)(2) (1988). The District Court, noting that the

plaintiffs had amended their complaint twice after the

effective date of the new fee-shifting provision, awarded

fees incurred by the defendants after the effective date.

Judge Goettel determined these fees to total $92,000, plus

$1,350 of expenses. The rationale for awarding defen

dants their attorney’s fees to this extent was not simply

that the defendants were “prevailing part[ies]” but that the

lawsuit was “totally meritless.” Opinion at 7.

Even if we assume for the argument that the amended

fee-shifting provision could be applied to a lawsuit filed

before its effective date, to the extent of shifting fees

incurred after its effective date, we cannot agree that fees

could be awarded under the Fair Housing Act. That

statute, like other civil rights fee provisions, permits an

award of fees to prevailing defendants only upon a show

ing that the suit is “frivolous, unreasonable, or without

6393

foundation.” See Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412, 421 (1978). As the District Judge recog

nized, the plaintiffs’ suit adequately alleged the elements

of a prima facie case of discrimination and presented a

factual dispute for the jury as to whether the plaintiffs had

proven that the defendants’ articulation of non-discrimi-

natory reasons for their actions was pretextual. See Sas-

sower v. Field, 752 F. at 1189-90.

It is arguable that even a civil rights plaintiff must bear

the risk of an award of defendant’s attorney’s fees when

a jury resolves factual disputes in favor of a defendant

and a judge concludes that the claim, though requiring

jury consideration, was entirely insubstantial. We have

upheld fee-shifting after a civil rights bench trial where

the plaintiff’s testimony was found to have been “an

unmitigated tissue of lies.” See Carrion v. Yeshiva Uni

versity, 535 F.2d 722, 728 (2d Cir. 1976). In the pending

case, however, the essential issue was not whether the

plaintiffs were credible in their account of the factual cir

cumstances; it was whether the defendants’ explanations

for their actions were legitimate or pretextual. There is no

finding that the plaintiffs did not believe that they had

been the victims of discrimination. Moreover, though

there were various disputes as to some details of the deal

ings between the plaintiffs and the defendants, there was

no finding that the plaintiffs’ had given a false account of

the basic facts alleged to support an inference of dis

criminatory motive. Nor is this a case where the trial

judge expressed the view that no reasonable jury could

have found in plaintiff’s favor but reserved ruling on a

motion for a directed verdict and submitted the case to the

jury simply to have a verdict in the event that a court of

appeals might have disagreed with his subsequent ruling

to set aside a plaintiffs’ verdict, had one been returned. In

6394

these circumstances, to award defendants their attorney’s

fees simply because the jury found in their favor and the

trial judge found the verdict overwhelmingly supportable

risks imposing too great a chilling effect upon the pros

ecution of legitimate civil rights lawsuits. We cannot sus

tain the fee award under the Fair Housing Act.

Though the outcome of the lawsuit adverse to the plain

tiffs is an insufficient basis to require them to pay defen

dants’ attorney’s fees under the Fair Housing Act,

substantial issues remain as to whether the plaintiffs are

liable for such fees for the manner in which they con

ducted the litigation.

B. Rule 11. Recognizing the possibility that the fee

award might not be sustainable under the Fair Housing

Act, Judge Goettel grounded portions of the award alter

natively upon Fed. R. Civ. P. 11, the Court’s inherent

authority, and 28 U.S.C. § 1927. Rule 11 applies, as the

District Court recognized, to those who sign a “pleading,

motion, and other paper” without making “reasonable

inquiry [that] it is well grounded in fact.” Fed. R. Civ. P.

11. Judge Goettel assessed $50,000 as a Rule 11 sanction.

However, he did not specify the documents the signing of

which violated the Rule. He probably had in mind prin

cipally the complaint, though he also noted that “[djuring

the course of this lengthy proceeding, both of [the plain

tiffs] signed numerous documents.” Opinion at 11. Since

we conclude below that the $50,000 portion of the award

grounded on Rule 11 is equally supportable by the exer

cise of the District Court’s inherent authority, we need not

return the matter to Judge Goettel for a precise identifi

cation of which documents warranted Rule 11 sanctions.

C. 28 U.S.C. § 1927. As a further alternative to a fee

award under the Fair Housing Act, Judge Goettel

6395

grounded a portion of the fee award, $42,000, on 28

U.S.C. § 1927, which permits imposition of fees upon

“[a]ny attorney or other person admitted to conduct cases

in any court of the United States” who “multiplies the

proceedings in any case unreasonably and vexatiously.”

28 U.S.C. § 1927 (1988). This $42,000 is in addition to

the $50,000 awarded under Rule 11. Unquestionably, the

conduct of the plaintiffs warranted an award under section

1927. The issue posed by this portion of the award is

whether section 1927 sanctions may be imposed on pro se

litigants, or at least on a pro se litigant who was a lawyer

at the time of the litigation.

Judge Goettel ruled that section 1927 may be applied to

pro se litigants, including non-lawyers. The Ninth Circuit

has adopted this position. See Wages v. I.R.S., 915 F.2d

1230, 1235-36 (9th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct.

986 (1991). We disagree. Section 1927 applies to any

“attorney or other person admitted to conduct cases” in a

federal court. Judge Goettel considered the pro se plain

tiffs to be “person[s] admitted to conduct cases” because

they had been granted permission to proceed pro se. Opin

ion at 17. But the word “admitted” in this context sug

gests application to those who, like attorneys, gain

approval to appear in a lawyerlike capacity. Moreover,

parties generally have a right to appear pro se. See 28

U.S.C. § 1654 (1988); O’Reilly v. New York Times Co.,

692 F.2d 863, 867 (2d Cir. 1982). Though the Sassowers’

former attorney needed and obtained permission to be

relieved, the granting of his motion left the plaintiffs free

to proceed pro se, without further order of the Court.

Moreover, it is unlikely that Congress intended the

phrase “other person” to include a person lacking lawyer-

like credentials. The prior version of the statute read “any

attorney, proctor, or other person admitted.” See Motion

6396

Picture Patents Co. v. Steiner, 201 F. 63, 64 (2d Cir.

1912). This phrasing also suggests that “other person”

covers those admitted to act in a lawyerlike capacity. We

also note that the Supreme Court recently recounted, with

out disagreement, a District Court’s assertion that section

1927 “applies only to attorneys.” See Chambers v.

NASCO, Inc., I l l S. Ct. 2123, 2131 (1991). This refer

ence implies approval of the District Court’s view, since

there would have been no need for the Supreme Court to

consider the larger question of the trial judge’s inherent

authority to sanction if section 1927 had applied to the

non-lawyer.

Though section 1927 will not support sanctions against

Elena Sassower, it is available for use against Doris Sas-

sower, who, though acting pro se, was a lawyer, at least at

the time of this litigation. Since section 1927 is designed

to curb abusive tactics by lawyers, it should apply to Atty.

Sassower notwithstanding the fact that her only client in

this matter was herself.

As an alternative to reliance on section 1927, Judge

Goettel grounded the $42,000 portion of the sanctions on

the Court’s inherent authority, as he had done, alterna

tively, with the $50,000 portion based on Rule 11. We turn

then to that basis of authority.

D. Inherent Authority. Judge Goettel explicitly relied,

alternatively, on his inherent authority in the portion of

his Opinion awarding Rule 11 sanctions, see Opinion at

11, and in the portion awarding section 1927 sanctions,

Opinion at 18. We may reasonably infer that he intended

to base the $50,000 portion of the award, alternatively, on

his inherent authority, to whatever extent it was not sup

portable by Rule 11, and to base the $42,000 portion of

the award, alternatively on his inherent authority, in the

6397

event section 1927 was deemed inapplicable to Elena

Sassower.

The Supreme Court has made clear that a district court

has inherent authority to sanction parties appearing before

it for acting in bad faith, vexatiously, wantonly, or for

oppressive reasons. See Chambers v. NASCO, Inc., I l l S.

Ct. at 2133. Having reviewed the course of the litigation

and the numerous instances of entirely vexatious and

oppressive tactics engaged in by the plaintiffs, we agree

with Judge Goettel that his inherent authority was prop

erly used to sustain these portions of the award.

E. Amount of Sanctions. We have ruled that when a

court awards defendant’s attorney’s fees, it must take into

account the financial circumstances of the plaintiff. See

Farad v. Hickey-Freeman Co., 607 F.2d 1025, 1029 (2d

Cir. 1979). No concern need be raised with respect to

Doris Sassower. Judge Goettel explicitly relied on trial

testimony that revealed that she was living in “a two mil

lion dollar mansion.” Opinion at 10 n.6. Though the value

of an expensive home does not necessarily demonstrate

ability to pay $93,350 in sanctions, Doris Sassower has

made no claim on appeal that the sanction is beyond her

means. With respect to Elena Sassower, however, Judge

Goettel explicitly stated that he did “not believe that she

is financially able to respond in the payment of attorneys’

fees and sanctions.” Opinion at 19 (footnote omitted). He

noted that she had claimed during the trial to be indigent.

Nevertheless he imposed liability for the fees jointly upon

Elena and her mother, though expressing his expectation

that “these costs will probably have to be borne solely by”

the mother. Opinion at 19.

Though we conclude that the Judge was entitled to find

both mother and daughter liable for sanctions, we must

6398

vacate the imposition of joint liability for the full amount

upon Elena, in the absence of evidence that her financial

resources permit an award of that size. Upon remand, the

District Court may assess against her such portion of the

award as is appropriate in light of her resources.

Though the amount of the sanction that we fully uphold

with respect to Doris Sassower is large, it is in fact only

a portion of the fees expended by defendants that could

have been assessed in view of the plaintiffs’ conduct.

Judge Goettel chose to award only those fees incurred

after the effective date of the amended fee provision of

the Fair Housing Act. Since the fee award is being sus

tained on the basis of authority other than the Act, the

selection of this date as a starting point for fees operates

as a fortuitous benefit for the plaintiffs.

II. New Trial

Continuing their vexatious and harassing tactics, the

plaintiffs submitted to Judge Goettel, several months after

the trial, a motion for a new trial under Rule 60(b)(3). The

motion was accompanied by several hundred pages of

supporting papers and a thousand pages of exhibits. In the

main, the motion is nothing more than a reargument of

numerous claims made prior to and during the trial,

including factual issues resolved against the plaintiffs by

the jury. Judge Goettel acted well within his discretion in

denying the motion.

We have considered all of the other issues raised by

appellants and find them totally lacking in merit.

6399

Conclusion

The denial of plaintiffs’ motion for new trial and for

sanctions against the defendants is affirmed; the supple

ment judgment awarding sanctions against the plaintiffs

is affirmed as to liability, affirmed as to amount with

respect to Doris Sassower and vacated and remanded as to

amount with respect to Elena Sassower.

6400