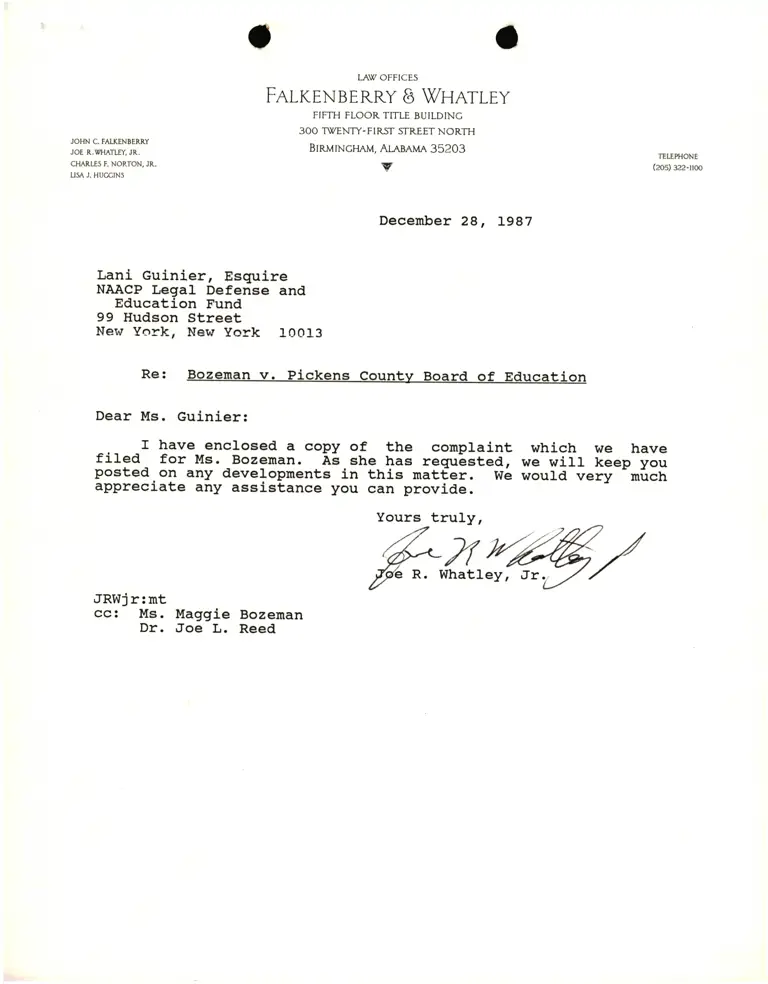

Correspondence from Joe Whatley to Lani Guinier Re Bozeman v. Pickens County Bd. of Elections

Correspondence

December 28, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Joe Whatley to Lani Guinier Re Bozeman v. Pickens County Bd. of Elections, 1987. df6a7137-ea92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/33cddc94-8a00-453c-a6ba-a2d789235402/correspondence-from-joe-whatley-to-lani-guinier-re-bozeman-v-pickens-county-bd-of-elections. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

JOHN C. FALKENBERRY

JOE R.VHATLEY, JR.

CMRLES F. NORTON, JR.

USA J. HUCTINS

IA1OT OFFICES

FalicexBERRY I WuarlEy

FTFTH FLOOR TITLE BUILDING

3OO T!7ENTY-FIRsT STREET NORTH

BIRU INcHau, ALABAMA 35203

v TELEPHONE

(2os) 322-rm

December 28, 1987

Lani Guinier, Esguire

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York I0OI3

Re: Bozeman v. pickene County Board of Education

Dear Ms. Guinier:

r have encrosed a copy of the conpraint which we havefiled for Ms. Bozeman. As.she has regulsted, we witt xeep-youposted.on any developments in this mat€er. Wir would very -mirch

appreciate any assistance you can provide.

Yours tru1y,

&-X

i/e a. whatl €Y,

JRWjr:mt

cc: Ms. Maggie Bozernan

Dr. Joe L. Reed