Mississippi State Chapter Operation Push v. Mabus Brief for the Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 19, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mississippi State Chapter Operation Push v. Mabus Brief for the Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1990. e345f0e1-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3401ce1d-c684-403d-89a5-a0bb9f50590f/mississippi-state-chapter-operation-push-v-mabus-brief-for-the-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

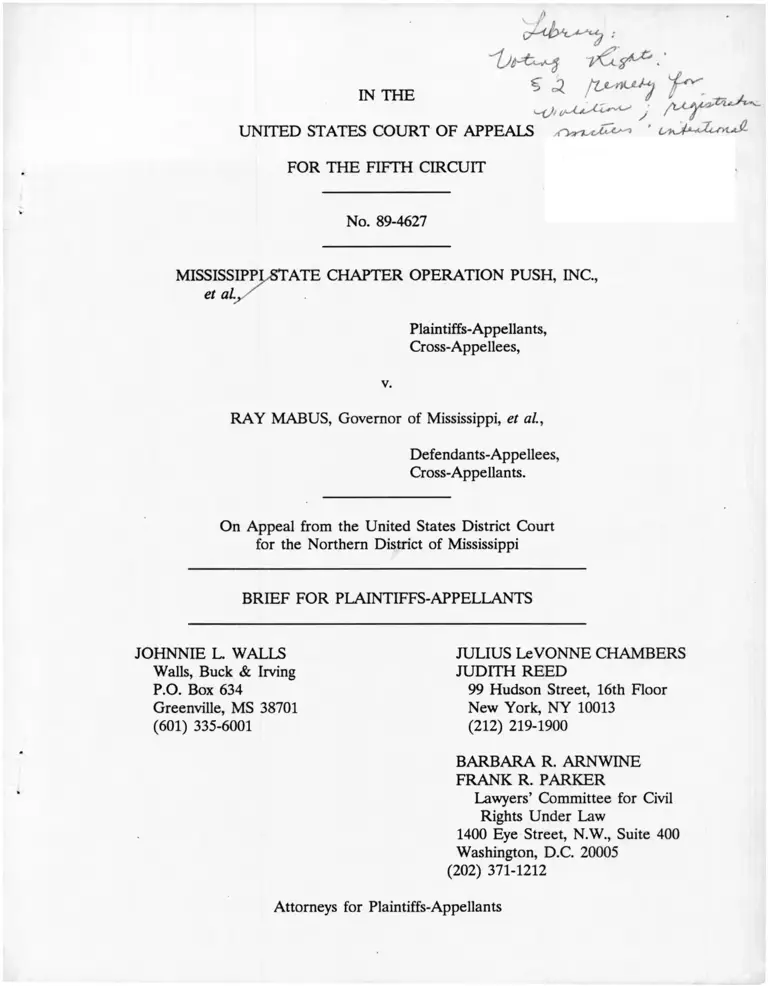

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

s^r

No. 89-4627

MISSISSIPPINSTATE CHAPTER OPERATION PUSH, INC.,

et a l,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Cross-Appellees,

v.

RAY MABUS, Governor of Mississippi, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JOHNNIE L. WALLS

Walls, Buck & Irving

P.O. Box 634

Greenville, MS 38701

(601) 335-6001

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

JUDITH REED

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

FRANK R. PARKER

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W., Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The under signed counsel certifies that the following listed persons have an interest

in the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the Judges of

this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

1. The plaintiffs in this action: Charles Green, Eugene Pressley, L.C. Felix,

Bessie Tucker, Lawrence Diggs, Randy Curtis, Sam McCray, Robert Jackson,

Leslie McLemore, Quitman County Voters League, Mississippi State Chapter

Operation PUSH, Inc.

2. The attorneys who represented the plaintiffs: Julius L. Chambers and Judith

Reed, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.; Barbara Arnwine

and Frank R. Parker, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law;

Johnnie Walls, Walls, Buck & Irving, Ltd.

3. The defendants in this action: Ray Mabus, Governor of the State of

Mississippi; Dick Molpus, Mississippi Secretary of State; Edwin Lloyd

Pittman, Attorney General, State of Mississippi.

Lillie B. Jones, Circuit Clerk, Quitman County; Robert L. Carter, Circuit

Clerk, Panola County; Martha Sellers, City Clerk, Crenshaw, MS; Billie

Jones, City Clerk, Sledge, MS; Evelyn Elliott, City Clerk, Crowder, MS.

4. The attorneys who represented the defendants: T. Hunt Cole, Special

Assistant Attorney General, Jackson, MS; Hubbard T. Saunders, IV,

Crosthwait, Terney & Noble, Jackson, MS; W.O. Luckett, Jr., Michael T.

Lewis, Luckett Law Firm, Clarksdale, MS.

Attorney/5f ijecord for plaintiffs-appeHants

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-appellants hereby request that this case be set for oral argument. This

case presents important questions regarding the application of the remedial principles of

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act where the district court has found racial discrimination

in voter registration practices.

11

Certificate of Interested P erso n s........................................................................................... i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument ................................................................................. ii

Statement of Jurisdiction...................................................................................................... 1

Statement of the Issues Presented .................................................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ......................................................................................................... 1

Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1

I. Procedural H isto ry ......................................................................................... 2

II. Statement of the F a c ts ................................................................................. 7

A. The District Court’s 1987 Findings of Discrimination................. 7

B. The Remedy Testimony: the 1987 T r ia l ........................................ 10

C. The Inadequacies of Senate Bill 2610 as a Remedy ................. 12

D. Racial Purpose in the Rejection of House Bill 734 17

E. The District Court’s Decision Rejecting Further Relief ........... 19

Summary of Argument ........................................................................................................... 20

A rg u m e n t.......................................................................................... 22

I. The District Court Erred in Refusing to Order an Effective Remedy

for a Proven Violation.................................................................................... 22

A. The Applicable Remedial S tandard ................................................ 23

B. The scope of the v io lation ................................................................ 25

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

i n

Page

C. The District Court Supposition that Voter Apathy Relieves a

State of its Remedial Burden Reflects Significant Legal

Error ................................................................................................... 26

D. Senate Bill 2610 is not Coextensive with the Scope

of the Violation Because it Would Perpetuate the Violation . . 28

II. The District Court Erred in Approving Senate Bill 2610 as a Remedy

Because That Statute Was Enacted, and More Effective Relief

Defeated, for the Racially Discriminatory Purpose and Effect of

Minimizing Black Registration....................................................................... 32

A. The District Court Erred in Deferring to the Legislative

Judgment Because that Judgment was Tainted with

Discrimination....................................................................................... 32

B. Senate Bill 2610 Should Have Been Rejected by the District

Court as a Remedy Because It Was Enacted, and More

Effective Remedies Rejected, for a Racially Discriminatory

Purpose and Effect.............................................................................. 34

III. The District Court Erred in Refusing to Order into Effect A Proposed

Remedy which Provides a Complete Remedy for the Violation in This

Case.................................................................................................................... 40

CONCLUSION ...................................................................................................................... 42

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Page

Brooks v. Winter, 461 U.S. 921 (1983) ......................................................... 41

Buchanan v. City of Jackson,

683 F. Supp. 1537 (W.D. Tenn. 1 9 8 8 ) ....................................................... 33

Buchanan v. City of Jackson, Tennessee,

683 F. Supp. 1547 (W.D. Tenn. 1988),....................................................... 28

City of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 (1980) ......................................................................................... 34

City of Pleasant Grove v. United States,

479 U.S. 462 (1987) ...................................................................................... 36

Connor v. Finch,

431 U.S. at 425 .............................................................................................. 33, 35

Connor v. Finch,

434 U.S. 407 (1977) ...................................................................................... 33

Dillard v. Crenshaw County,

831 F.2d 146 (11th Cir. 1987)...................................................................... 33

Dillard v. Crenshaw County,

831 F.2d 246 (11th Cir. 1987)....................................................................... 24, 29, 35

Edge v. Sumter County,

775 F.2d 1509 (11th Cir. 1 985 ).................................................................... 25, 39

Gomez v. City of Watsonville,

863 F.2d 1407 (9th Cir. 1988), cert, denied. 103 L. Ed.

2d 839 (Mar. 20, 1989) ................................................................................. 26

Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ...................................................................................... 29, 31

v

Page

Jordan v. Winter,

541 F. Supp. 1135 (N.D. Miss. 1982), vacated and

remanded, sub nom.. Brooks v. Winter. 461 U.S. 921

(1983)................................................................................................................ 41

Jordan v. Winter,

604 F. Supp. 807 (N.D. Miss. 1984), affd sub nom..

Mississippi Republican Executive Committee v. Brooks.

469 U.S. 1002 (1984) .................................................................................... 36

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors,

554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.), cert, denied.

434 U.S. 968 (1977) ..................................................................................... 26,28,31,33

LULAC v. Midland Independent School District,

648 F. Supp. 596 (W.D. Tex. 1986), affd . 812 F.2d 1494

(5th Cir. 1987), vac’d and affd on other grounds.

829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987)...................................................................... 33

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1 9 3 9 )............................................................... 29

Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965) ................................ 20,24,29,41

Major v. Treen,

574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1 9 8 3 )............................................................... 35

Martin v. Allain,

658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987) ......................................................... 37

McMillan v. Escambia County,

748 F.2d 1037 (5th Cir. 1984)...................................................................... 27

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 (1974) ..................................................................................... 24

Mississippi Republican Executive Committee v. Brooks,

469 U.S. 1002 (1984) 36

Page

Mississippi State Chapter Operation PUSH, et al. v. Allain,

et al., 674 F. Supp. 1245 (N.D. Miss. 1987) ............................................ Passim

Mississippi State Chapter PUSH, et al. v. Mabus, et al.,

717 F. Supp. 1189 (N.D. Miss. 1989)......................................................... Passim

Monroe v. City of Woodville, Mississippi,

819 F.2d 507 (5th Cir. 1987), cert, denied. 484 U.S.

1042 (1 9 8 8 ) ...................................................................................................... 28

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979) ........................................................................... 35

Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964) ........................................................................... 33

Rogers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613 (1982) ....................................................................................... 34

Roman v. Sincock,

377 U.S. 695 (1964) ...................................................................................... 21, 33

Seastrunk v.Burns, 772 F.2d 193 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) .......................................... 32

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ).......................................................................................... 29

Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1 9 8 6 ) ............. .......................................................................... 24, 34

United States v. Duke,

332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964) ...................................................................... 33

United States v. Marengo County Comm’n,

731 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 469 U.S.

976 (1 9 8 4 )........................................................................................................ 26, 28

United States v. Ramsey,

353 F.2d 650 (5th Cir. 1965) ...................................................................... 20,30,31,33

vii

Page

Upham v. Seamon,

456 U.S. 37 (1982) ........................................................................................ 33

Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1984)...................................................................... 36

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1977) ...................................................................................... 35

Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. Westwego,

872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989)...................................................................... 27

Wise v. Lipscomb,

437 U.S. 535 (1978) ...................................................................................... 23

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972) ...................................................................................... 29

Wright v. City of Houston,

806 F.2d 634 (5th Cir. 1986) ...................................................................... 32

STATUTES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ................................................................................................ 1

Miss. Code Ann. § 21-11-1 (1972).................................................................... 3

Miss. Code Ann. § 21-11-3 (1972).................................................................... 3

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-5-25 (1972).................................................................... 3

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-5-29 (1972).................................................................... 3

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-5-29 (1972).................................................................... 3

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-15-37 (1986 Sp. Pamph.) ............................................ 10

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-15-39 (1986 Sp. Pamph.) ............................................ 3

viii

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-15-223 (1986 Sp. Pam ph.).......................................... 3

S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1982),

reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 1 7 7 .................................. Passim

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1971 and 1983 ................................................................................................ 3

Clarion-Ledger, Sun. March 4, 1990, p. 3H .................................................. 31

Page

IX

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The district court entered final judgment dismissing this action on July 20, 1989.

Plaintiffs-appellants filed a notice of appeal of that portion of the district court’s judgment

adopting the remedy proposed by defendants on August 15, 1989. Defendants filed a

cross-appeal on the issue of liability on August 29, 1989. This court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Did the district court err in approving a proposed remedy that fails to

eliminate all the effects of the violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

2. Did the district court err in approving a proposed remedy that is tainted with

discriminatory purpose and effect in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and section

2 of the Voting Rights Act?

3. Did the district court err in failing to order additional remedial measures that

were necessary to fully cure the violation?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Introduction

For more than 80 years prior to 1965, the State of Mississippi unlawfully denied

black citizens the right to vote through the literacy test, the poll tax, the white primary,

good moral character requirements, vote fraud and intimidation, and restrictive voter

registration procedures. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 struck down the poll tax and the

discriminatory voter registration tests that had denied Mississippi black people the ballot,

including the literacy test.

But the Act did not of its own force suspend restrictive voter registration

procedures that had been adopted for an equally racially discriminatory purpose and had

a racially discriminatory effect. These included (a) Mississippi’s "dual registration"

requirement that voters who live in municipalities must register twice--first with the circuit

clerk (county registrar) to vote in federal, state, and county elections, and again with the

municipal clerk to vote in municipal elections, and (b) the prohibition on satellite

registration^ that generally required all voters to travel to the circuit clerk’s office in the

county courthouse to register.

This lawsuit is a challenge to these continued restrictions on equal access to the

voter registration process. The district court ruled that both were racially discriminatory

obstacles to voter registration that violated section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. This

appeal involves the issue of whether the relief approved by the district court is adequate

2to remedy all the effects of these discriminatory restrictions on access to voter registration.

I. Procedural History

Plaintiffs, who are five eligible but unregistered black voters, three black registered

voters, and two organizations engaged in voter registration drives, filed this lawsuit in

March, 1984. Their complaint challenged Mississippi’s dual registration requirement (Miss.

Code Ann. §§ 21-11-1, 21-11-3, 23-5-25, 23-5-29 (1972)) and statutory prohibition against

* Throughout this brief the prohibition on satellite registration refers to the state

statute prohibiting circuit clerks from removing the voter registration books from their

offices to register voters outside their offices.

2

Defendants’ cross-appeal contests the district court’s ruling on the merits of

plaintiffs’ challenge to these restrictions.

2

'J

registration outside the circuit clerk’s offices (Miss. Code Ann. § 23-5-29 (1972)) as

violative of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, 42 U.S.C. §§

1971 and 1983, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. R. 1.^

Defendants are the members of the State Board of Election Commissioners

(composed of the Governor, the Secretary of State, and the Attorney General), the circuit

clerks of two counties, and the city clerks of three municipalities. The district court

certified two plaintiff classes of (1) all eligible but unregistered black citizens of Mississippi,

and (2) all black registered voters of Mississippi, and two defendant classes consisting of

(1) all Mississippi circuit clerks, and (2) all Mississippi municipal clerks (R. 247, 263).

After the complaint was filed, the Mississippi Legislature modified, but did not

eliminate, the dual registration requirement and retained the prohibition on satellite

registration. Miss. Code Ann. §§ 23-15-39, 23-15-223 (1986 Sp. Pamph.). The 1984

legislation allowed voters for the first time to register with the circuit clerks for state,

county and municipal elections and required the State Board of Election Commissioners

This statute, as adopted in 1955, provided that "the registration books shall not be

removed from the office of the county registrar [circuit clerk]" without permission of the

county board of supervisors. Once every four years in a statewide election year or if a

reregistration was ordered, the county board of supervisors could enter an order requiring

the circuit clerk to spend one day of registration at precinct polling places. See 674 F.

Supp. at 1251.

^ Throughout this brief, "R." refers to pages of the pleadings record, "RE" refers to

pages of the Record Excerpts, "Tr." and "Ex." refer to pages of the trial transcript and

exhibits introduced in evidence at the July, 1987 trial, and "Rem. Tr." and "Rem. Ex." refer

to pages of the transcript and exhibits introduced in evidence at the June 1, 1989, remedy

hearing.

3

to appoint some municipal clerks as deputy registrars.^ The 1984 legislation retained the

prohibition on removing the registration books without a written order from the county

board of supervisors, and, if an order was entered, limited circuit clerks to registering

voters at polling places (except when the polling place was not available). Miss. Code

Ann. § 23-15-37 (1986 Sp. Pamph.).

After these 1984 amendments were enacted, defendants moved to dismiss this case

as moot. But the district court denied the motion and, referring to the dual registration

requirement, quoted Mark Twain that "[t]he reports of [its] death are greatly exaggerated."

R. 247, p. 6. Plaintiffs filed a supplemental complaint stating their objections to the new

legislation and alleging that the remaining features of the dual registration requirement and

the continued statutory restriction on satellite registration in the 1984 legislation violated

plaintiffs’ constitutional and statutory rights. R. 265. They alleged that retaining the dual

registration requirement for municipalities where the municipal clerk was not appointed

a deputy registrar, not making the 1984 amendments to the dual registration requirement

retroactive, and continuing the restriction on satellite registration perpetuated the effects

of past discrimination and denied black citizens equal access to the voter registration

process.

̂ However, the mandatory deputization of municipal clerks was limited only to those

in municipalities over 500 in population who are employed on a full-time basis and keep

regular office hours each day. Further, the legislation allowing voters to register with the

county circuit clerks for municipal elections was prospective only. This meant that anyone

who had registered with the circuit clerk prior to the 1984 amendments becoming law was

still required to register again with his municipal clerk for municipal elections.

4

After a six-day trial in July, 1987, the district court found that the dual registration

requirement and the prohibition on satellite registration had been adopted for a

discriminatory purpose and that the continued limitations on voter registration had a

racially discriminatory result that violated section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Mississippi

State Chapter Operation PUSH, et al. v. Allain. et al.. 674 F. Supp. 1245 (N.D. Miss.

1987) (RE 25-51). The district court denied injunctive relief, but set forth "minimum

requirements" for the state legislature to adopt that the court thought would bring the

state’s election laws into compliance with the Voting Rights Act. 674 F. Supp. at 1269.

The court suggested that the 1984 amendments be made retroactive by requiring that the

names of municipal residents already registered with the county circuit clerks be

transferred to the municipal poll books, that all municipal clerks be appointed deputy

county registrars, that circuit clerks be required to conduct at least one day of satellite

registration at three polling places in each county supervisors’ district in each state election

year, and that a procedure be established for registering disabled citizens in their homes.^

Id- at 1269-70.

The Mississippi Legislature adopted Senate Bill 2610 (Miss. Laws, 1988, ch. 350)

that amended Mississippi’s voter registration laws to meet these minimum requirements.

In 1988, when the legislature adopted Senate Bill 2610, it considered but refused to pass

legislation that would have permitted voter registration at all public libraries, offices of

^Testimony at trial showed that the prohibition on voter registration outside registrars’

offices meant that disabled persons confined to their homes could not register, although

if previously registered they could vote by absentee ballot.

5

state and county agencies serving members of the public, and high schools and colleges.

House Bill 838, 1988 Reg. Sess., Rem. Ex. P-5. Plaintiffs filed objections to Senate Bill

2610 and contended that this relief was not sufficient to remedy the racially discriminatory

effects of Mississippi’s past restrictions on voter registration. RE 52. For relief, plaintiffs

requested the court to order mail-in voter registration, voter registration in state and local

agencies serving members of the public, and election day registration, and asked the court

to permit door-to-door registration by deputy registrars. The Mississippi Legislature in its

1989 session considered, but refused to pass a statute permitting both mail-in voter

registration and voter registration at libraries, schools, and government agency offices

("agency-based" voter registration). House Bill 734, 1989 Reg. Sess., Rem. Ex. P-1.

The district court in June, 1989, held an evidentiary hearing on plaintiffs’ objections

to the relief provided by the Mississippi Legislature in Senate Bill 2610, but denied any

further relief. Mississippi State Chapter PUSH, et al. v. Mabus. et al., 717 F. Supp. 1189

(N.D. Miss. 1989) (RE 20-24). The district court entered judgment dismissing the action

on July 20, 1989, RE 16, and plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal on August 15, 1989.

R. 2376. Defendants also have cross-appealed, contesting the district court’s holding of

a section 2 violation. R. 2378.

6

II. Statement of the Facts

A. The District Court’s 1987 Findings of Discrimination

The district court in its 1987 decision held that the vestiges of the dual registration

requirement contained in the 1984 legislation and the statutory prohibition on satellite

registration had a discriminatory impact on black voter registration and violated plaintiffs’

rights under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. 674 F. Supp. 1245, 1261-68.

The district court noted Mississippi’s long history of racial discrimination in voter

registration that included the use of such discriminatory devices as poll taxes, literacy tests,

residency requirements, white primaries, and the use of violence to intimidate black people

from registering to vote. 674 F. Supp. at 1250. The effects of this historical official dis

crimination continue to impede black voter registration and turnout. Black voter

registration in the Delta area, which contains the state’s largest black concentration, is still

disproportionately lower than white registration, and black elected officials hold less than

10 percent of all elective offices despite the fact that Mississippi is 35 percent black. Id.

at 1250, 1265.

The district court found that both the dual registration requirement and the

prohibition on satellite registration were adopted for a racially discriminatory purpose. Id-

at 1251-52. The dual registration requirement was adopted contemporaneously with the

"Mississippi plan" of 1890, which included the poll tax, the literacy test, and other

disfranchising devices. Id. at 1251. Similarly, the prohibition on satellite registration was

adopted in 1955, along with a series of state segregation statutes, to restrict black registra

tion. Before 1955, county registrars were required to spend one day at each polling place

7

in the county in each state election year to register voters; after 1955, county registrars

were prohibited from registering voters at polling places except by order of the county

board of supervisors. Id. at 1251-52. Mississippi is apparently the only state in the nation

to adopt a statewide statutory dual registration requirement and a statutory prohibition on

removing the registration books from the registrars’ offices. Id. at 1252.

The district court also found that these restrictions had a present discriminatory

impact on black voter registration rates. Id. at 1252-55. The district court found, based

on a survey of returned jury summonses, that only 54 percent of voting age black people

in Mississippi were registered to vote, as compared with 79 percent of the white voting age

population. Id. at 1253. The discriminatory impact of the dual registration requirement

even after 1984 is shown by the fact that municipal election tallies, taken from federal

observers’ reports, show that more black citizens than white citizens have been denied the

right to vote in municipal elections because their names could not be found on the

municipal voter registration rolls. Id. at 1255. Since black candidates have lost by margins

substantially less than the number of black voters who were denied the right to vote, the

district court concluded that the dual registration requirement has probably resulted in the

defeat of black candidates for office. Id.

The district court further found that the prohibition on satellite registration had a

racially discriminatory impact because disproportionately fewer eligible black citizens are

able to take off from work or to travel to the county courthouse or city hall during

business hours to register to vote. First, the district court found that proportionately more

black workers than white are employed in blue-collar and service worker positions in which

8

they work for an hourly wage. As a consequence, they are less able to take off from work

to register to vote during the regular office hours during the week when most registrars’

office are open. Id. at 1256. Second, the district court found, based on U.S. Census

statistics, that, in Mississippi, black people are more likely than white people to lack

available transportation to travel to the county courthouse or city hall to register. Id.

According to these census data, 27.8 percent of all black-occupied households have no

motor vehicle available, as compared to only 6.76 percent of all white-occupied households.

The district court found that this disparity is particularly severe in the heavily black Delta

area, where black households are more than four times as likely to lack available

transportation than white households. Id. These statistics were corroborated by voter

registration workers who testified that their voter registration drives were dependent upon

providing transportation to prospective registrants. Id.

The district court also found that these limitations contained in the challenged

statutes severely restricted access to the voter registration process. The statute deputizing

only municipal clerks in cities over 500 with regular office hours meant that residents of

heavily black Delta counties had to travel substantial distances to find a county registrar

or municipal clerk qualified to register them to vote in all elections. Id. at 1256-57.

Surveys of the registration practices of the circuit clerks after the 1984 legislation was

passed showed that few of them conducted satellite registration, held evening or Saturday

registration, or appointed deputy registrars other than those regularly employed in their

offices. Id. at 1257-59. Numerous requests made by black voter registration workers for

satellite registration, evening and weekend registration, and the appointment of deputy

9

registrars were denied. Id. Further, statistics on the race of persons employed as deputy

registrars showed a prima facie case of racial discrimination in the appointment process;

very few of those appointed as deputy registrars have been black. Id. at 1259. After

examining the reasons presented by defendants for these restrictions on registration

contained in the 1984 legislation, the district court concluded that these restrictions did not

advance any substantial or legitimate governmental interests and were not rationally related

to any substantial governmental interest. Id. at 1261, 1266-67.

B. The Remedy Testimony: the 1987 Trial

There was considerable testimony given at the 1987 trial, from both lay and expert

witnesses, regarding ways to increase voter registration for both black and white citizens.

The thrust of the testimony was clear: the elimination of the requirement that registration

take place only at centralized locations, during daytime hours was essential to increase

black voter registration. Sherrod Brown, Ohio Secretary of State and former state

legislator, testified that the most effective ways to increase registration include mail-in

registration, agency-based registration, and liberal deputization of volunteers, so that

registration may take place at any location where interested persons are found. The State

of Ohio has used such methods for several years, with considerable success in increasing

registration. Secretary Brown, Tr. 576-84, 590.

Mississippi voter registration workers, based on years of experience in conducting

registration drives in Mississippi and meeting with black unregistered voters, testified that,

as the district court recognized, the time and place restrictions on voter registration make

voter registration inaccessible to persons without transportation and those who worked in

10

factories, on plantations, or at other hourly jobs. See, e.g., Jordan, Tr. 415-17; Sanders,

Tr. 387. See also, circuit clerk Dunn, Tr. 843-44.

Making voter registration accessible to such persons requires, at minimum, that

regular and frequent evening and weekend registration be conducted. Gardner, R., Tr.

616-17; Jordan, Tr. 417-18. Intermittent satellite registration at the polling places,

conducted at the discretion of the registrars, was not effective in registering significant

numbers of voters. Ex. P-72; Dunn, Tr. 860-61; circuit clerk Martin, Tr. 976. Moreover,

for satellite registration to be effective, it needs to be conducted at regular and frequent

7

intervals, at locations in or near the black community, and involve black deputy registrars.

Gardner W., Tr. 241; Jordan, Tr. 435; Boyd, Tr. 534-35; Gardner, R., Tr. 614; 674 F.

Supp. at 1258. David Jordan, a black teacher, city councilman and activist, summarized

what is needed:

[M]ake voter registration easy by putting it in the churches, in the schools,

in the Headstart centers, and at the grocery stores, . . . and deputize people

to register people in the shopping centers, or do it by cards. There are

many ways it can be done.

Tr. 435-36. A National Committeeman for the Democratic Party and Hinds County

Supervisor testified that door-to-door registration would "greatly enhance the registration

7

Unrebutted testimony indicates that many blacks in Mississippi felt intimidated by

becoming involved with white registrars or entering the courthouse, and they would be

more likely to register at satellite sites located in the black community. See, e.g., Gardner,

R., Tr. 615; Sanders, Tr. 382; Gardner, W., Tr. 241; Foster Tr. 471; Gardner, W., Tr. 245;

Thompson, Tr. 343; Foster, Tr. 475; Griggins, Tr. 655-56; McCray, Tr. 674; Jordan Tr. 435.

The appointment of black deputy registrars is also likely to have a salutary effect.

Gardner, R., Tr. 614; Foster, Tr. 475; Gardner, W., Tr. 261.

11

of black voters." Thompson, Tr. 344-45. See also, Kirksey, Tr. 362; Griggins, Tr. 655-

56.

The effectiveness of weekend satellite registration in a good location was

underscored by the testimony of one of the defendants in this case. The Hinds County

registrar, Barbara Dunn, testified that, in response to a request, she conducted satellite

registration at a shopping center, the Jackson Mall, located in a predominantly black area.

She considered it a good location, and noted that "people are very comfortable in coming

to the mall to shop, so why not be able to register to vote[.]" Moreover, while precinct

polling place registration is generally low, Ms. Dunn testified that the Jackson Mall site

resulted in a registration rate that exceeded the number registered at any other satellite

locations. Tr. 845-46.

Nonetheless, despite this testimony, the district court concluded that the violation

found in this case could be remedied by simply modifying existing voter registration

procedures, rather than providing a more complete remedy. 674 F. Supp. at 1269-70;

supra, p. 5. The district court recognized that implementing a completely fair registration

system might well have to involve broader relief, such as authorizing voter registration at

any public place, registration at bureau of motor vehicle offices ("motor voter") and other

county offices, and high school registration. However, the trial court was "of the opinion

that to mandate these in the manner plaintiffs suggest would be an inappropriate if not

impermissible exercise of this court’s jurisdiction." 674 F. Supp. at 1268 n. 16.

12

c . The Inadequacies of Senate Bill 2610 as a Remedy

Senate Bill 2610 was enacted simply to satisfy the "minimum requirements" set forth

by the district court in its opinion. The statute established a procedure for transferring

the names of persons eligible to vote in municipal elections from the county voter

registration rolls to the municipal voter registration rolls (the statute also provided for

automatic municipal registration of persons residing areas annexed by municipalities);

mandated deputization of all municipal clerks as deputy registrars; repealed the

requirement that the registration books may not be removed from the county registrars’

offices without approval of the county boards of supervisors; and required circuit clerks

to register voters in at least three precinct polling places in every supervisors’ district once

every four years in every statewide election year. Rem. Ex. D-l.

Plaintiffs, in their objections to this legislation as a remedy, contended that these

measures were inadequate to remedy the massive disparity in white and black voter

registration rates and left intact the time and place restrictions on registration that the

district court previously found were barriers to black registration. RE 52. First, they

contended that there was no evidence that these measures would eliminate the 25

percentage point voter registration disparity between white and black registration that the

district court found in its opinion. Second, they contended that these measures

perpetuated the central discriminatory limitation of the prior procedures by

O

° The statute also provided for expanded voter registration hours and half-day

Saturday registration at the circuit clerks’ offices for five days prior to voter registration

deadlines for primary and general elections and provided for in-home registration of

disabled persons.

13

generally restricting the time and place of registration to a central location, either the

county courthouse or city hall, during regular business hours. They contended that simply

allowing one-day precinct polling place registration at only three precincts per supervisors’

district only once every four years and providing expanded registration hours for only five

days before registration deadlines would not be sufficient to remedy the violation. The

statute did not even require that the expanded voter registration hours at circuit clerks’

offices be publicized. More importantly, the new statute continued to prohibit door-to-

door registration and voter registration at shopping malls, stores, high schools, churches,

and welfare and unemployment offices where large numbers of unregistered persons are

likely to be found. RE 55.

At plaintiffs’ request, the district court conducted an evidentiary hearing on June

1, 1989 on plaintiffs’ objections to Senate Bill 2610 as a remedy. The unrebutted, credible

testimony and other evidence produced at this hearing showed that Senate Bill 2610 is not

likely to have any significant impact on the disparity between white and black registration

rates caused by the section 2 violations and that the legislation fails to remove, or even

significantly ameliorate, the administrative barriers to voter registration that the district

court found were difficult for black people in Mississippi to overcome. Further, the

uncontradicted evidence also showed that the Mississippi Legislature enacted these

minimal changes and rejected more effective remedial relief for the discriminatory purpose

and effect of minimizing voter registration opportunities for black citizens.

14

The defendants presented no evidence that under Senate Bill 2610 the extreme

disparity in registration rates would be narrowed, let alone eliminated.^ Conversely,

plaintiffs presented significant credible and uncontroverted evidence through expert and

lay testimony that the racially disparate effects of Mississippi’s voter registration

procedures would continue.

Plaintiffs’ witnesses included a leading authority on American electoral systems, the

Vice Chair of the House Committee on Apportionment and Elections, a former state

senator and community activist, and a Quitman County voter registration activist. All were

unanimous in their conclusion that Senate Bill 2610 will not significantly increase black

voter registration or do anything to eliminate the disparity. The reason for this is simple -

- Senate Bill 2610 maintains the time and place restrictions found to have a greater impact

on black registration than white registration opportunities. Voter registration in Mississippi

still is limited to county courthouses, city halls, and polling places. Extensive travel is still

required. Indeed, Dr. Richard Cloward, a leading expert on American electoral systems

and co-author of Why Americans Don’t Vote, a leading treatise on voter registration

barriers, testified that, according to his research, which was unquestioned, even after the

1989 legislation Mississippi remains the most restrictive state in the union with regard to

voter registration. States where registration is limited to the clerks’ offices have the lowest

registration rates. Cloward, Rem. Tr. 58.

^ The record is also devoid of any evidence that legislature consulted any black

community leaders or black voter registration leaders to determine whether Senate Bill

2610 was adequate as a remedy.

15

Dr. Cloward testified that because these restrictions are still in place, he would be

"astonished" if Senate Bill 2610 increased the voter registration rates by even one or two

percentage points. Rem. Tr. 69. Representative John Grisham Jr., a white state legislator

and vice-chair of the House Committee on Apportionment and Elections, who studied

voter registration procedures in Mississippi and other states extensively and who was a key

figure in the legislative debate on the legislation, agreed. Representative Grisham testified

that "[i]n my opinion, 2610 will not significantly increase voter registration for blacks or

for whites, and I don’t think you can find any circuit clerk or very few circuit clerks or

very few legislators who believe it will." Deposition of Rep. John Grisham, Jr., p. 29;

Kirksey, Rem. Tr. 83. The increase in the number of municipal clerks appointed deputy

registrars does not remove the travel and time restrictions and, therefore, would have, at

best, only a "marginal" effect on registration rates. Cloward, Rem. Tr. 71; Jamieson, Rem.

Tr. 38; Kirksey, Rem. Tr. 84. For the same reason, mandatory satellite' registration only

once every four years would have no effect. Jamieson, Rem. Tr. 45; Kirksey, Rem. Tr.

85.

In addition to making clear that Senate Bill 2610 would not eliminate or ameliorate

the disparity in registration rates, the testimony illustrated the several effective ways to

reach the unregistered population. The single most effective way to swiftly increase

registration is to register persons on election day. Cloward, Rem. Tr. 27. The second

most effective way to increase the level of voter registration is a combination of

registration by mail and through state or federal agencies, such as the procedures set forth

in House Bill 734 and House Bill 838. Id- at 58. Finally, the third most effective way is

16

to use mail-in registration along. Id- In the absence of mail-in registration, liberal

deputization is also effective. Id. at 59. Under the circumstances of this case, the most

effective way to eliminate the disparity in registration rates is to have the government

conduct door-to-door registration. Id- at 67.

D. Racial Purpose in the Rejection of House Bill 734

The evidence is uncontradicted that Senate Bill 2610 was passed and the other

proposed voter registration legislation (House Bill 734 in 1989 and House Bill 838 in 1988)

was rejected for the racial reason that legislators and circuit clerks were afraid that making

registration more accessible would significantly increase black registration. Representative

John Grisham, who was a co-sponsor of House Bill 734 and actively participated in the

legislative consideration of both bills, testified that racial discrimination -- fear of increased

black registration -- was a significant factor in the House rejection of House Bill 734.

Representative Grisham testified that "[tjhere was a lot of fear . . . among the clerks . .

. and a significant minority of House members that mail-in registration will, in fact,

increase black voter registration. . . . There [was] a lot of fear . . . of [that] . . . on the

House floor; not so much a fear of fraud, but a fear of actually getting some of these

folks registered, black Mississippians." Grisham dep., pp. 42-43, also, Id. pp. 43-46. The

circuit clerks lobbied intensively against real voter registration reform, and there was

extraordinary manipulation by legislators to defeat the legislation. Representative

Grisham’s testimony that racial discrimination was a significant factor in the defeat of

House Bill 734 is supported by the testimony of Henry Kirksey, a former state legislator.

Based on his analysis of the circumstances of the bill’s defeat, Kirksey concluded that "the

17

posture of the Legislature on race hasn’t changed a great deal . . . . That posture is that

the lower the black voter registration, the better." Rem. Tr. 90.

The discriminatory intent of Senate Bill 2610 was further evidenced by the voting

patterns on the alternative legislation. Every member of the House Black Caucus voted

for the legislation, Grisham dep., p. 44, and a high percentage of the white House

members who voted against the bill came from urban areas and other areas of the state

with high black population concentrations/^ Rem. Tr. 89.

There was other evidence of discriminatory intent. House Bill 734 was initially

adopted by the House in 1989 by a vote of 67 to 53. Rem. Ex. P-2. Prior to the 1989

legislative session, the Mississippi Circuit Clerks Association officially "decided to take no

position as an association on mail-in registration." Rem. Ex. P-15, Exhibit 14; Grisham

dep., p. 23. However, immediately after House Bill 734 was passed and held over on a

motion to reconsider, the circuit clerks began flooding the House members with hundreds

of telephone calls expressing outrage and objections to the mail-in registration bill.

Grisham dep., pp. 3-24. According to Rep. Grisham, "the circuit clerks killed the bill . .

. there is no doubt in anyone’s mind or anybody on the floor that the circuit clerks killed

the bill." Id. pp. 25-26.

The next day, January 26, House Bill 734 was defeated even though a majority of

the House voted for it, because an amendment to the bill converted the mail-in voter

10 During the floor debate, an opponent of the bill, Rep. Tommy Horne of Meridian

stated: "I don’t care anything about helping anybody too lazy to go register to vote."

Grisham dep., pp. 32-33. Rep. Curt Hebert of Pascagoula, another opponent, stated: "I

think it’s a radical move from what we’re used to seeing in Mississippi." Id., p. 33.

18

registration bill into a revenue bill which required a three-fifths vote — 71 votes — for

passage. After the amendment was adopted, although the vote was 62 to 57 in favor of

the bill, it was defeated because it lacked the nine votes needed to pass it as a revenue

bill. Rem. Ex. P-2; Grisham dep. pp. 24-26.

E. The District Court’s Decision Rejecting Further Relief

Despite this evidence, which was uncontradicted in this record, the district court

approved Senate Bill 2610 (referred to as Chapter 350 in its opinion) as a complete

remedy in this case and rejected plaintiffs’ requests for additional relief. 717 F. Supp.

1189 (N.D. Miss. 1989). The district court upheld this legislation as a remedy without

making any finding that the statute would substantially increase the black voter registration

rate or eliminate the 25 percentage point gap in black-white registration rates in the state.

Indeed, the district court disregarded the extensive uncontradicted testimony that (1) the

legislation would not remedy the effects of past restrictions on voter registration, but

would in fact perpetuate the discriminatory impact of those restrictions; and (2)

discriminatory intent was a significant factor in the passage of this legislation and the

rejection of other remedies that would provide greater voter registration access.

Instead, the district court’s decision denying further relief was based its view that

it was obliged to defer to the legislative judgment, 717 F. Supp. at 1190-91, that it was not

required to adopt a remedy that significantly increased black registration rates because

those low rates may be the result of "factors such as voter apathy," id. at 1191, that the

procedures of the 1988 legislation were better than those they replaced, id. at 1192-93, and

that ordering further relief would "entangle [the court] in the essentially political process

19

of determining the appropriate voter registration procedures for the State of Mississippi,'

id. at 1192.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court approved Senate Bill 2610 as a remedy and failed to order more

extensive relief because it erroneously believed that ordering additional relief was beyond

the court’s jurisdiction. 674 F. Supp. at 1268 n. 16; 717 F. Supp. at 1192. To the

contrary, familiar remedial principles as well as the legislative history of Section 2 provide

that a district court has not only the power but also the duty to grant affirmative remedial

relief that will eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future. Louisiana v. United States. 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965); S. Rep.

No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 31 (1982), reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.

News 177, 208.

Having found that Mississippi’s procedural restrictions on voter registration

discriminated against black citizens and resulted in a 25-percentage-point disparity between

white and black registration rates, the district court failed to order any effective relief that

would significantly increase black voter registration or alleviate this disparity. This Court’s

decisions in voter registration cases of the 1960’s clearly establish that the effects of prior

racial discrimination in registration cannot be eradicated merely by imposing uniform

requirements on blacks and whites alike if those requirements perpetuate existing

registration disparities. United States v. Ramsey. 353 F.2d 650 (5th Cir. 1965).

Senate Bill 2610 retains the central features of the prior restrictions on satellite

registration which the district court found to violate Section 2. The new state statute

20

continues to restrict time and place of registration. It still requires citizens to travel to a

central location (the county courthouse or city hall) generally during regular business hours

to register to vote, restrictions which the district court previously found have a disparate

impact on the opportunities of black citizens to register. The proof presented shows that

Senate Bill 2610 would do little to eliminate the effects of the past discrimination, and

defendants failed to rebut that evidence. No evidence was presented that simply

requiring precinct polling place registration for one day every four years and expanded

hours and Saturday registration five days before registration deadlines would have any

significant impact upon black registration rates.

Further, the district court erred in deferring to the legislative remedy because it was

tainted with discrimination. Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. 695, 710 (1964). The

uncontradicted proof shows that Senate Bill 2610 was adopted, and statutes providing

more extensive relief were rejected by the legislature, for the purpose and effect of

minimizing black voter registration opportunities. The leader of the legislative effort to

pass additional legislation and a former state legislator testified without contradiction that

alternative remedies were rejected for a discriminatory purpose, and the district court was

not free to ignore their testimony.

Other evidence supports their conclusions. The evidence shows that Senate Bill

2610 would have a discriminatory impact and was enacted in context of an extensive past

history of official racial discrimination affecting black political participation in Mississippi.

A discriminatory purpose also is shown by evidence that more extensive relief was

recommended by the House Interim Study Committee and the defendant Secretary of

21

State, that procedural irregularities played a role, and that there was no good nonracial

reason for not passing more extensive relief. This evidence, which the district court

disregarded, demonstrates that the legislative remedy is tainted with both a discriminatory

purpose and a discriminatory effect that violate the Fourteenth Amendment and section

2 of the Voting Rights Act.

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Erred in Refusing to Order an Effective Remedy for a

Proven Violation.

The district court’s decision upholding Senate Bill 2610 as a remedy for the

violation is against the weight of the evidence presented at both the 1987 trial and the

1989 remedy hearing and contrary to the applicable law. Indeed, the court’s holding is

totally at odds with its own findings on the liability issue. The district court’s refusal to

order a sufficient remedy conflicts with the remedial standards of the Voting Rights Act.

The district court in this case adopted a theory of deference to a legislatively

proposed remedy that threatens to effectively gut section 2. In direct contrast to

Congress’ specific directions on the issues, the district court failed to measure the

legislation against the proper standard — whether the remedy would completely eliminate

the violation -- and improperly allocated the heavy burden of proof Congress sought to

impose on proven violators. Essentially, the district court’s failure in this case reflects two

critical legal errors. First, the district court misperceived the scope of the violation in this

case and therefore did not ask the correct questions. Second, the district court approved

a remedy which itself violated section 2 and failed to meet the State’s remedial obligations.

22

These errors permeate the district court’s opinion and taint its finding that the

legislation cures the section 2 violation. Given defendants’ failure to demonstrate that

Senate Bill 2610 will cure the violation and, alternatively, based on plaintiffs’ extensive and

unrebutted evidence that intentional discrimination entered into to the passage of Senate

Bill 2610, this Court should remand this matter to the district court with directions to

enter an order that provides for an effective remedy.

A. The Applicable Remedial Standard

The district court began its analysis by holding that it would follow the standards

of deference applicable to the review of challenged reapportionment plans. 717 F. Supp.

at 1190-91. The district court recognized it must determine whether the 1988 legislation

remedied the violation, but it held that it was "unwilling" to rule that Senate Bill 2610

would not be effective in eliminating the disparity in registration rates, in the absence of

"preponderating" and "objective" proof that the procedure would have "no effect on the

disparity." 717 F. Supp. at 1192. Finally, the trial court felt compelled to approve the

legislation and thought it was without power to order an effective remedy, because it

"discern[edj . . . no constitutional or statutory flaws" in the legislation. Id.

The district court noted it was "reluctant to entangle itself in the essentially political

process of determining the appropriate voter registration procedures for the State of

Mississippi." 717 F. Supp. at 1192. But section 2’s remedial principles require a district

court to do just that, once there has been a finding of a violation. The district court

provided defendants with a reasonable opportunity to propose their own remedy, as

required by Wise v. Lipscomb. 437 U.S. 535 (1978), and its progeny. When defendants

23

failed to show their remedy would not remedy the violation, the district court was then

required to implement procedures that provided a remedy for the existing violations of

section 2.

The core principle of section 2 is that a court faced with a violation of that section

must "exercise its traditional equitable powers to fashion the relief so that it completely

remedies the prior dilution of minority voting strength and fully provides equal opportunity

for minority citizens to participate and to elect candidates of their choice." S. Rep. No.

97-417, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 31 (1982), reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

117, 208 ["Senate Report"]. A "court has not merely the power but the duty to render

a decree which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as

well as bar like discrimination in the future." Louisiana v. United States. 380 U.S. 145,

154 (1965). It "cannot authorize [a plan] . . . that will not with certitude completely

remedy the Section 2 violation." Dillard v. Crenshaw County. 831 F.2d 246, 252 (11th Cir.

1987) (emphasis in original). The scope of a complete remedy, and thus of the court’s

remedial power, is determined by the nature and extent of defendants’ violations. Cf.

Milliken v. Bradley. 418 U.S. 717, 744 (1974). In a variety of antidiscrimination contexts,

cited with approval in the legislative history of section 2, the Supreme Court has

recognized that a court’s remedial powers must extend beyond simply eliminating the

^ The Supreme Court has termed the Senate Report an "authoritative source"

regarding Congress’ purpose in enacting the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act.

Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 43 n.7, (1986).

24

actual mechanism of discrimination when a broader remedy is necessary to remedy the

72"condition" that offends principles of racial justice.

Finally, a proposed remedy cannot itself constitute a violation of section 2. See

Edge v. Sumter County. 775 F.2d 1509, 1510 (11th Cir. 1985).

The district court did not correctly apply these principles and erred in approving

the legislation as a complete remedy in this case.

B. The scope of the violation

The question whether a plan provides a complete remedy necessarily requires

consideration of the nature and scope of the violation found. In this case, the

discriminatory impact of the violations extend beyond the retention of dual registration,

the limitations on satellite registration, and the failure to deputize all municipal clerks.

Put simply, the violation consists of the State’s use of a panoply of registration practices

and procedures that resulted in the registration of far fewer blacks than whites and

operated to deny black citizens an effective voice in the political process. The extent of

the State’s section 2 violation is graphically demonstrated by the stark disparity between

black and white registration rates:

[Bjlack citizens of Mississippi are more likely than not

registered at a rate of approximately 54 percent of the black

VAP, while whites are more likely than not registered at a rate

of approximately 79 percent of the white VAP. Thus, the

1Z See. Senate Report at 31 n. 121. In the Report, Congress reaffirms its

commitment to dealing with discriminatory practices, including registration barriers,

"comprehensively and finally." Senate Report at 5, 53. In the section 5 context, a covered

jurisdiction as an obligation "to eliminate the continued effects" and to counter the

perpetuation of years of pervasive voting discrimination.

25

black registration rate is approximately 25 percentage points

below the white registration rate.

674 F. Supp. at 1255. The specific violation in this case, then, is the 25 percent gap in

black-white registration rates that resulted from the State’s voter registration practices.

C. The District Court Supposition that Voter Apathy Relieves a

State of its Remedial Burden Reflects Significant Legal Error.

The district court’s failure to order an affirmative remedy in this case stemmed in

large part from its belief that the State was not obliged to make any real effort to register

blacks because the depressed registration rate might be, in part, a product of apathy. 717

F. Supp at 1191. The district court’s supposition is wrong as a matter of law and logic.

It has long been the law in this Circuit that voter apathy "is not a matter for judicial

notice." Kirksev v. Board of Supervisors. 554 F.2d 139, 145 (5th Cir.), cert, denied. 434

U.S. 968 (1977). See also, United States v. Marengo County Comm’n. 731 F.2d 1546,

1568-68 (11th Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 469 U.S. 976 (1984) (rejecting trial court’s

"speculation" that apathy is the cause of lowered black political participation); Gomez v.

City of Watsonville. 863 F.2d 1407, 1416 (9th Cir. 1988), cert, denied. 103 L.Ed.2d 839

(Mar. 20, 1989) (court erred in focusing on apathy instead of more relevant evidence).

Moreover, in light of the actual facts found at the liability phase, it is patently clear that

the failure of blacks to participate more fully in the political process is a result of

pervasive racial discrimination.

In this case, the district court found, inter alia, that Mississippi had a history of

discrimination touching on the right to vote. The court also found that black citizens lag

behind whites in terms of every socioeconomic indicator that might affect their political

26

participation and access to the registration process. The trial court also found that the

statutes and the manner in which predominantly white registration officials exercised their

discretion erected barriers to registration that were more difficult for blacks to overcome

than whites. Congress recognized that when there is a combination of low socioeconomic

status and low voter turnout, a court can take judicial notice of the fact that the low

socioeconomic status itself is a direct result of the state’s own discrimination in terms of

employment provisions of municipal services, and other areas. Senate Report at 29. See

also, McMillan v. Escambia County. 748 F.2d 1037, 1044 (5th Cir. 1984) (reduced political

participation presumed to be the result of discrimination). In the face of such findings,

the question of voter apathy is simply irrelevant as a matter of law, and therefore it can

have no effect on the appropriate remedy. Cf. Westwego Citizens for Better Government

v. Westwego. 872 F.2d 1201, 1208 n.9 (5th Cir. 1989) (rejecting use of the lack of black

candidates to defeat a voting rights claim, where that very lack is traceable to the

discriminatory system).

Even if this factor were relevant, there is absolutely no evidence in the record that

so-called voter apathy played a role in creating the depressed black registration rate. The

State made no attempt to prove the existence of apathy or that it was a factor in the

depressed registration rate. Nor did the State argue that the sufficiency of its remedial

legislation was affected in any way by this issue. Under the circumstances of this case, the

district court was precluded from taking apathy into account in its decision.

27

D. Senate Bill 2610 is not Coextensive with the Scope of the

Violation Because it Would Perpetuate the Violation.

The remedy approved by the district court retains many of the features of the

former statutory scheme, while eliminating only certain discrete features. Thus, for

example, while dual registration is no longer required and satellite registration must be

conducted at least once every four years, persons who want to register to vote are still

required to confront virtually the same administrative barriers that led to the disparity.

Given the scope of the violation in this case, the district court was obliged to

implement a remedy that would equalize the registration rates for white and black

citizens. Monroe v. City of Woodville. Mississippi. 819 F.2d 507, 511 n. 2 (5th Cir.

1987) (per curiam), cert, denied. 484 U.S. 1042 (1988) ("where a violation of the Act is

established, courts should make an affirmative effort to fashion an appropriate remedy for

that violation"); United States v. Marengo County Comm’n. 731 F.2d at 1570 ("If blacks

are to take their rightful place as equal participants in the political process, affirmative

efforts are . . . necessary to register blacks").

The district court erred in "approving] a plan which tend[s] to carry forward into

the future the long-lived denial of black access to the political process". See. Kirksey, 554

F.2d at 152. See also, Buchanan v. City of Jackson. Tennessee, 683 F. Supp. 1547, 1545

(W.D. Tenn. 1988), (rejecting remedy proposal that retaining some at-large seats since

"the potential would remain for the election of an administration that is unresponsive to

the needs of the black community" and "black citizens would continue to have less

28

opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process

. . . .").

The record in this case makes clear that Senate Bill 2610 would simply freeze the

present registration disparity and would "fail to counteract the continuing effects of past

[discrimination]", Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 23

(1971). Entry of a decree that provides for merely a cessation of some of the

discriminatory conduct is not sufficient. Louisiana v. United States, supra; Lane v.

Wilson. 307 U.S. 268, 276 (1939) (rejecting legislation that "partakes too much of the

infirmity" of prior illegal statutes). Moreover, a proposed remedy that retains virtually all

the elements of a statutory scheme found to violate section 2 itself violates section 2 when

it merely perpetuates the existing disparity in black voter participation. Dillard v.

Crenshaw, supra. 831 F.2d at 252 (where many of the chilling elements were present in

the state’s remedial plan, that plan itself violated section 2).

Plaintiffs are entitled to a system that "promises realistically to work, and promises

realistically to work now." Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430, 439

(1968); see Senate Report at 31, n. 121 (relying on Green’s remedial formulation to

illustrate scope of courts’ powers in section 2 cases). A district court must make certain

that a remedial plan "providefs] meaningful assurance of prompt and effective" elimination

of past discrimination. Id. at 438. See also, Wright v. Council of City of Emporia. 407

U.S. 451, 460 (1972) (rejecting "free transfer" plan in absence of showing that plan would

"further rather than delay" desegregation). Only a remedy that realistically promises to

29

equalize registration rates in the black and white communities, can remove the taint that

infects the voter registration schemes invalidated in this case.

Not only was the district court’s refusal to order an effective remedy contrary to

the law, it was inconsistent with its liability findings. The district court concluded that the

state’s failure to remove "administrative barriers to voter registration has ‘resulted in the

disenfranchisement of a substantial number of black citizens who are unable, because of

disproportionate lack of transportation, disproportionate inability to register during

working hours, or other reasons, to travel to the office of the county registrar to register

to vote.’" 674 F.Supp. at 1264. Senate Bill 2610 retains the central features of the prior

restrictions on satellite registration which the district court found to violate section 2. The

new state statute continues to restrict time and place of registration. It still requires

citizens to travel to a central location (the county courthouse or city hall) generally during

regular business hours to register to vote, restrictions which the district court previously

found have a disparate impact on the opportunities of black citizens to register. The

proof presented shows that Senate Bill 2610 would do little to eliminate the effects of the

past discrimination, and defendants failed to rebut that evidence. No evidence was

presented that simply requiring precinct polling place registration for one day every four

years and expanded hours and Saturday registration five days before registration deadlines

would have any significant impact upon black registration rates.

The district court, in essence, has done what this Court long ago condemned in

United States v. Ramsey. 353 F.2d 650, 655 (5th Cir. 1965). In Ramsey, this Court held

that the racially discriminatory "effect of [inequitably applied registration procedures]

30

cannot be eradicated merely by correcting the future through uniform nondiscriminatory

tests applied to Negro and white alike." In this case, the district court has permitted a

statute shown to have had a discriminatory effect to continue in effect. The district court

was content to adopt a wait and see posture: "the mail-in registration sought by plaintiffs

may well be implemented in the State of Mississippi in the near future without need of

a court directive." 717 F. Supp. at 1192-93 n. 2. The district court was obliged to do

more than simply hope that defendants would cease discrimination sometime in the

future."^ When the violation represents a systemic denial of black citizens’ full political

rights, the court must ensure that the remedy eliminates the discriminatory character of

the offensive electoral schemes "root and branch." Green v. School Board of New Kent

County. 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968). The relief approved in this case permits the "rights

of [black] voters, so long postponed" to be further postponed and "rest" on the

"unpredictable" discretion of the circuit clerks, already shown to have been unresponsive

to the needs of black citizens. Ramsey, 353 F.2d at 657. As this Court noted in Kirksey,

"[t]he responsibility of the defendants to permit minority votes a proper role in democratic

political life must be discharged by stronger stuff than gossamer possibilities of all

variables falling into place and leaning in the same direction." 554 F.2d at 150.

Senate Bill 2610 is part and parcel of a system that was enacted and maintained

with the intention and effect of diluting black voting strength. Because Senate Bill 2610

^ T h is hope is evidently in vain: a mail-in voter registration bill was passed by the

Mississippi Senate, but it was defeated by the House in February of this year. Clarion-

Ledger, Sun. March 4, 1990, p. 3H.

31

perpetuates the racially disparate registration rates, it does not remedy the violation.

Instead, it will do precisely what several courts have held to be illegal and what Congress

condemned over 25 years ago: it will ensure that black Mississippians will continue to be

deprived of an opportunity to register, to vote and to participate in the electoral process,

in violation of section 2.

II. The District Court Erred in Approving Senate Bill 2610 as a Remedy

Because That Statute Was Enacted, and More Effective R elief Defeated, for

the Racially Discriminatory Purpose and Effect o f Minimizing Black

Registration.

A. The District Court Erred in Deferring to the Legislative

Judgment Because that Judgment was Tainted with

Discrimination.

The district court ruled that it was precluded as a matter of law from ordering

further relief by decisions of this Court requiring deference to the legislative judgment.

The district court considered that these decisions precluded it from adopting "an

objectively superior plan" if "an otherwise constitutionally and legally valid plan" has been

adopted by the state. 717 F. Supp. at 1191 (citing Seastrunk v. Burns, 772 F.2d 143, 151

(5th Cir. 1985); Wright v. City of Houston. 806 F.2d 634, 635 (5th Cir. 1986)).

The district court fundamentally misconstrued this legal standard (1) by failing

specifically to hold that deference to the legislative judgment is not required when that

judgment is tainted with racial discrimination; and (2) by failing fully to consider the

extensive evidence-uncontradicted in this record-that the Mississippi Legislature failed to

enact more extensive relief for the racially discriminatory reason that it would increase

black registration more than Senate Bill 2610.

32

The requirement that the state legislature must first be given an opportunity to

enact a remedy derives from the Supreme Court’s 1964 reapportionment decisions,

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 586 (1964). Since this is not a redistricting case, the

district court was not strictly required to follow that rule here and clearly had the

authority to order injunctive relief. United States v. Ramsey. 353 F.2d 650 (5th Cir.

1965); United States v. Duke. 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964). However, having chosen that

course, the district court was required also to observe the limitations on the rule of

legislative deference.

A principal limitation -- first articulated in the 1964 decisions — is that the

legislative remedy must be "free from any taint of arbitrariness or discrimination," Roman

v. Sincock. 377 U.S. 695, 710 (1964), and deference is not required to any legislative plan

that is tainted with discrimination. See Connor v. Finch. 434 U.S. 407, 415 (1977); Upham

v. Seamon. 456 U.S. 37, 43 (1982). Accordingly, in the redistricting cases, courts have

rejected remedial plans which themselves had a racially discriminatory purpose or effect

or which perpetuated the effects of the prior unlawful discrimination. Dillard v. Crenshaw

County. 831 F.2d 146 (11th Cir. 1987) (rejecting 5-1 plan as remedy for all at-large

elections); LULAC v. Midland Independent School District. 648 F. Supp. 596 (W.D. Tex.

1986), affd , 812 F.2d 1494 (5th Cir. 1987), vac’d and affd on other grounds. 829 F.2d 546

(5th Cir. 1987) fen band (rejecting proposed 5-2 plan as remedy for all at-large

elections); Kirksev v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County. 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.) fen

band , cert, denied. 434 U.S. 968 (1977) (rejecting gerrymandered county redistricting plan

33

for perpetuating prior discrimination); Buchanan v. City of Jackson, 683 F. Supp. 1537